1. Introduction

Technological and regulatory changes in maritime transport have been impressive since the millennium; so has the number and variety of shocks leading to severe disruption in the normal operations of shipping. An array of surprising and disastrous events have combined with less exceptional ones without their frequency, extent, and combination being fully reflected in any changes in the way risk is perceived - and hence managed - for recovery purposes following a major disruptive event.

The omnipresence of uncertainty is a standard characteristic of shipping, with its sources ranging from the physical and the financial environment the industry operates in to the overall state of the world economy; increasing resilience is considered the main antidote.Even outside the strict field of shipping risk management, maritime accidents have for a long time been the object of extensive analyses and have even served as examples - as was the case of the maritime tragedy of the passenger ferry

Herald of Free Enterprise - in the process of developing generic frameworks such as the Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) by [

1]. Shipping risk approaches remain, however, largely skewed towards addressing root causes on the basis of known hazards and probability-based scenarios. Having such a vantage point becomes of critical importance in a world of increasing complexity as an all-encompassing perspective allows one to create a general framework reconciling the need to ideally address all uncertainty [

2].

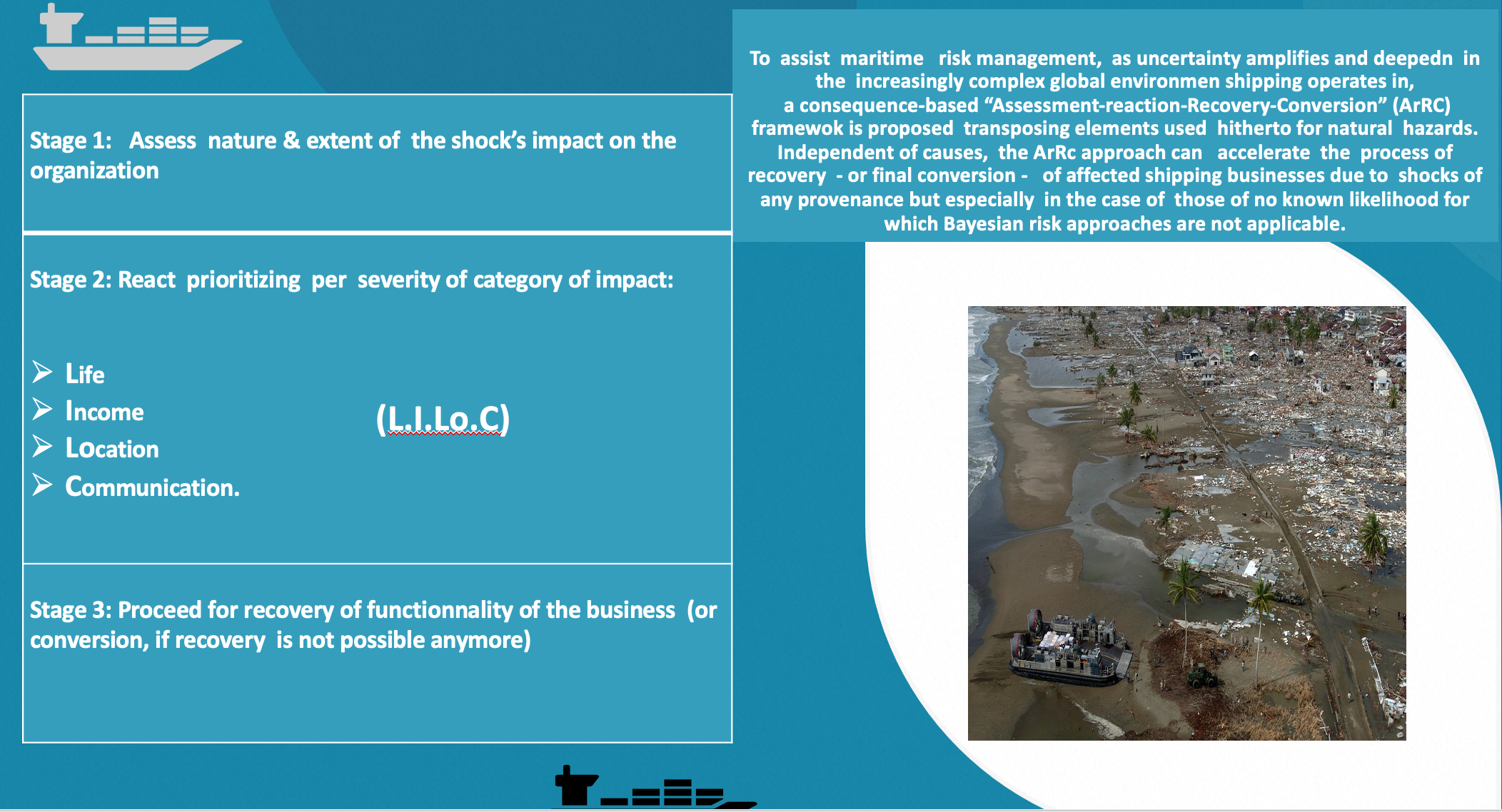

In this context, and on an expanded basis from [

3], the authors propose an Assessment-reaction-Recovery-Conversion (ArRC) framework for preparing shipping businesses for handling shocks, especially those of the “unknown-unknown” type. The aim of ArRC is to assist in managing the widest range of possible key impact, in increasing resilience and speed to the final recovery or, alternatively to a conversion position whenever the “Build Back Better” action principle [

4] is not a realistic prospect as bouncing back fully is not feasible.

The paper is structured in five sections. Following this introduction,

Section 2 proceeds to a classification of main theoretical approaches to risk across industries and activities.

Section 3 focuses on shipping-specific risk management approaches and on related existing risk management tools such as Decision Support Systems (DSS).

Section 4 advances the suggested ArRC approach emphasising that root-cause independent and consequence-based business preparedness can eventually contribute to bouncing-back faster and easier from negative effects across more types of exogenous shocks both at the level of the shipping industry as a whole and of individual companies. The concluding section highlights the usefulness as well as the limits of such a generic approach in an environment whose outreach and complexity facilitate shock transmission from risk factors in the unknown-unknown category.

2. Approaching Risk: Theoretical Vantage Points

Although omnipresent since the origins of shipping, commercial and operational risks faced by businesses in this industry remain a subject open to update and exploration as the number of related exogenous factors potentially involved has kept on increasing. In recent years, the need for an all-enveloping risk response framework has become even more apparent as the increased uncertainty and volatility of the world economy and of the shipping markets was followed by successive major geopolitical crises such as open wars in Ukraine and the Middle East and by new external threats to ships such as through the Red Sea attacks by armed groups.

Earlier research has focused on financial aspects of risk [

5], a focus which has been well explored in the specific shipping setting [

6,

7,

8] along with other shipping market risks.

As noted by [

9] based on [

10], risk identification techniques, risk assessment and risk reduction methods cover the risk management cycle phases. These stages which encompass risk identification, assessment and mitigation are essential for a safe technical, operational, and financial management alike. They are also pertinent tools to secure business continuity through proactive risk avoidance and suitable preparedness for mitigation (cf.

Figure 1).

The emphasis on a more generic approach, proposed here, taking a consequence vantage point and evolving from the middle stage of the risk management cycle in

Figure 1, does not contradict nor intends to substitute classical risk management approaches. Underlying many of the natural disaster mitigation plans and the related research a consequence-based approach satisfies both the classic Bayesian risk view and the concepts of unanticipated and unimaginable risks along the Rumsfeld and Taleb categorisations [

11,

12] i.e., risks which cannot be conceived beforehand.

The more classical risk approach was enriched by the introduction of the concept of “triplets of risk” by the seminal analysis in [

13], placing emphasis on the third critical risk aspect beyond probability and impact i.e., the risk setting/event itself. Addressing these risks, which is the final core stage of risk management frameworks, requires as a first step their identification in a maritime setting following the traditional risk management process [

14,

15].

Figure 1.

Risk management cycle stages

. Source: Based on [

9,

10,

14,

15].

Figure 1.

Risk management cycle stages

. Source: Based on [

9,

10,

14,

15].

In a shipping context, an attempt for a more consequence-based approach can be found in the scenario analysis of the impact of common hazards for cruise ships [

16]; yet, this analysis remains well within the remit of a Bayesian approach. However, the unpredictable nature of phenomena such as the ones qualified as “unknowns-unknowns” [

11], alternatively termed “Black Swan events” in [

12], does not allow for estimates of risk using probability and potential impact: When the foundational “what can happen” of the seminal approach of risk in [

13] is missing, then none of its constituent elements can be simulated or calculated.

In such cases, turning towards consequences - along the lines of a framework that has been used largely for the assessment and recovery from earthquake disasters permeating the actions of several related international initiatives [

17] - can increase resilience through accommodating genuinely unpredictable events in a generic risk management plan. In an industry fraught with a large variety of disruptive events - ranging from periodic and expected incidents to entirely irregular, and occasionally totally unimaginable shocks - a focus on consequences can complement more root oriented risk management approaches.

3. The Many Facets of Shipping Risks in an Era of Increased Uncertainty

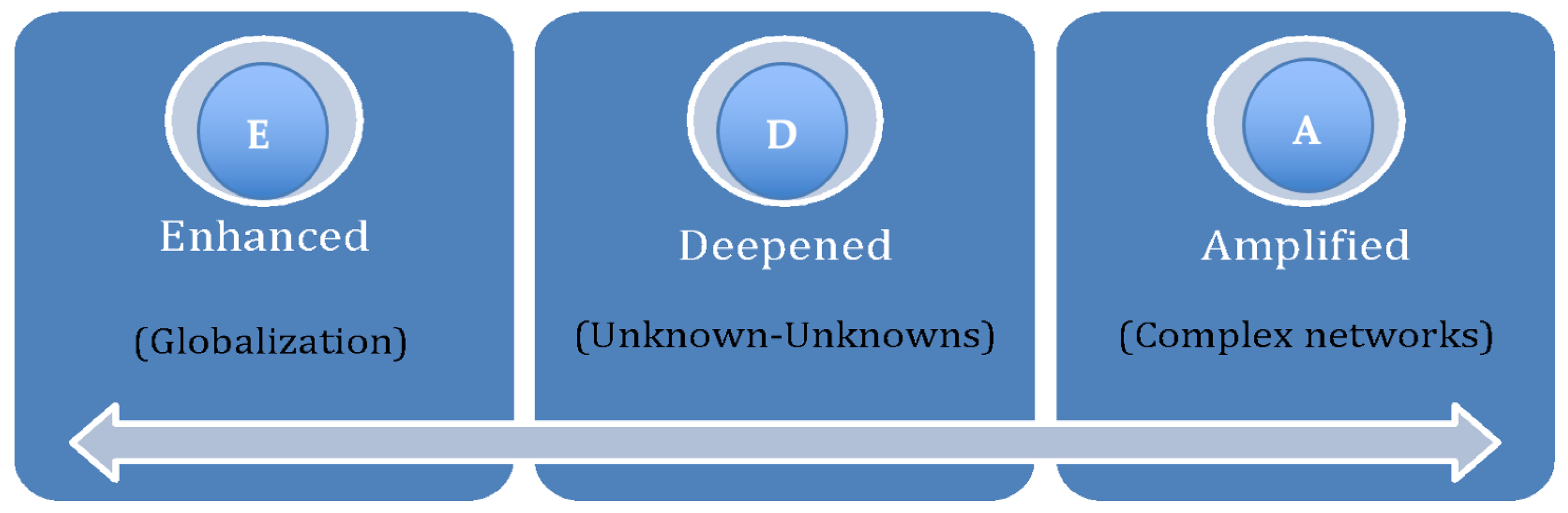

The nature and combinations of main risk factors that shipping businesses face - either on an individual or on an industry basis - keep on becoming more numerous and complex. The rise of average cargo and vessel sizes has boosted risk levels in terms of impact and related values. The resulting increase in total risk can be inferred almost directly from the doubling of world tonnage in about fifteen years [

18] and from the increasing complexity induced by globalisation plus by regional tensions.

All the aforementioned developments - along with network complexity as operational alliances took over liner shipping - enhanced, deepened and simultaneously amplified uncertainty (cf.

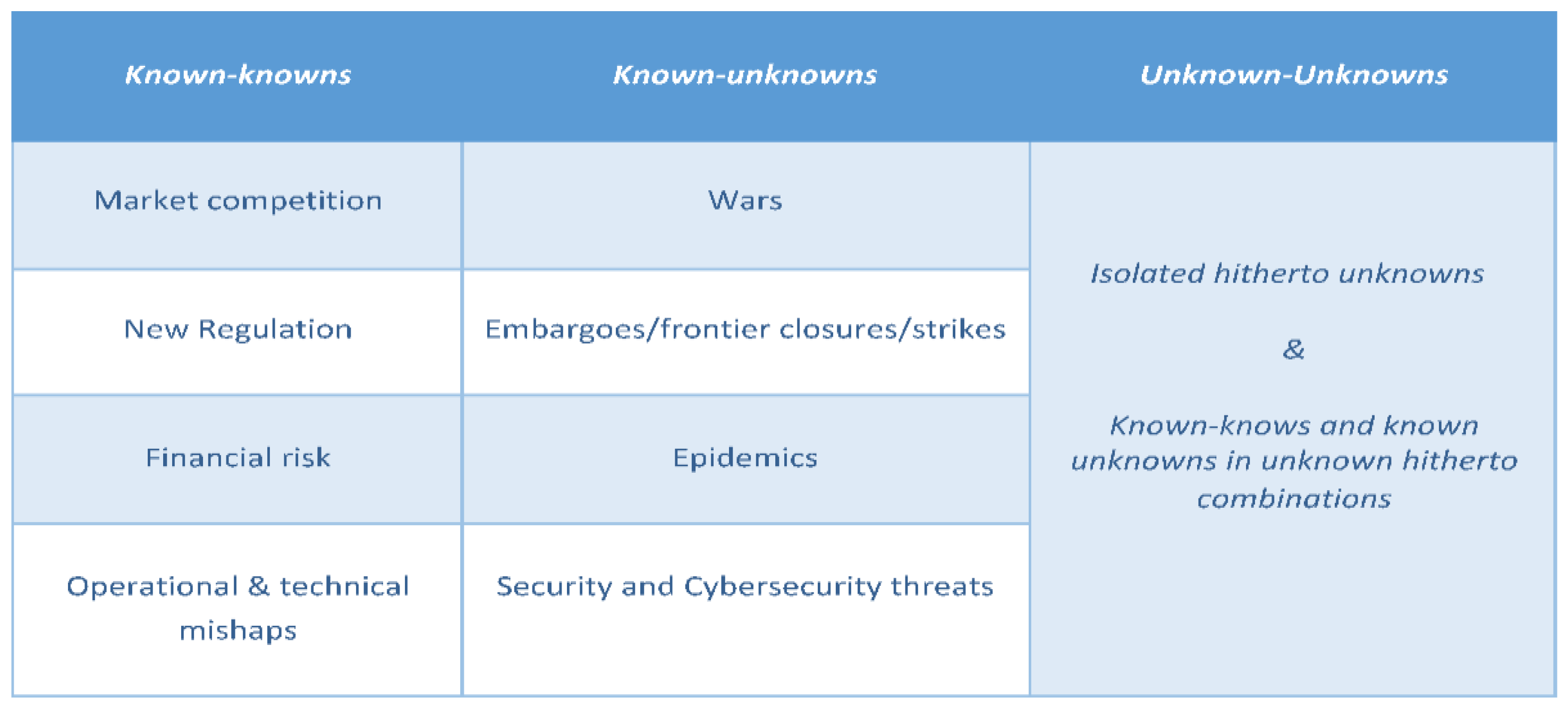

Figure 2), which increased overall through the combined effects of globalisation, proliferation of unknown-unknowns and increased global complexity.

3.1. Risks and the Idiosyncratic Nature of Shipping

Shipping firms may choose their risk exposure or level by choosing what trades to engage in, their financial gearing, and whether to trade in spot markets or on longer term contracts. However, such choices do not influence the wider or less known risks faced by shipping businesses, a broader categorization of which is presented in

Table 1 next.

In the recent turbulent decades following the Lehman Bros collapse in 2008, the vulnerability of shipping businesses increased further. This is especially so since a wider range of exogenous factors is now threatening larger vessels and cargo parcels with unknown-unknown factors. Such factors potentially combine to form new types of complex risk and impacts that are difficult to accommodate in a Bayesian logic with the limitations already underlined in [

13].

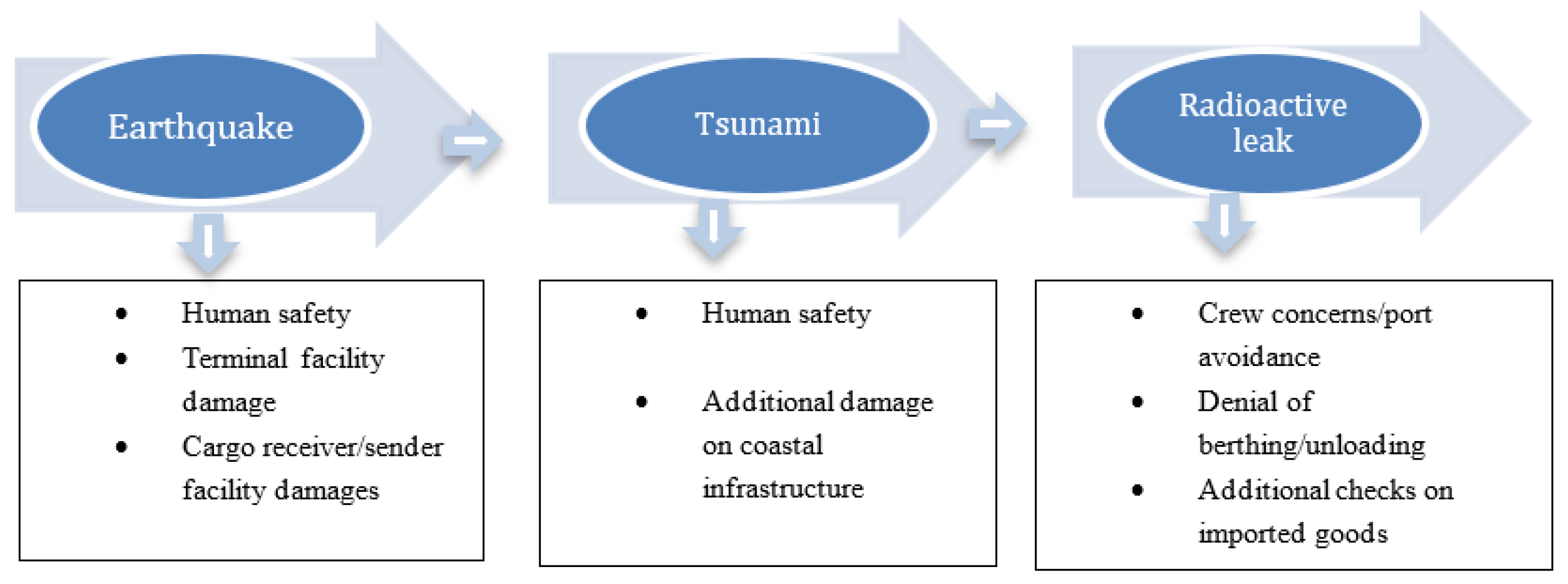

Several outcomes can originate from one initial event affecting just one single element of the system. However, the varying repercussions on any of the parties involved may originate from different causes containing various known exogenous or endogenous factors of any probability resulting in near infinite scenarios. The Fukushima disaster of 2011, which was the combination of three well known hazards regularly considered by risk management plans, namely an

earthquake, a

tsunami, and

radioactive leaks into the environment, constitutes a showcase of the potency of related permutations. Although none of the involved phenomena could be classified in the unknown-unknown category, as events unfolded it became clear that the specific risk chain had never been anticipated. Even if the duration of the industry’s bewilderment was measured more in hours than days [

20] the combined effect of three already well-known risks presented a clear example of a scenario of dire consequences that had not been even considered hitherto [

21,

22,

23].

While none of the Fukushima sequential factors (cf.

Figure 3) in this complex disaster could be classified on its own as a Black Swan or an “unknown-unknown” in the Rumsfeld typology, their combination definitely was one. For a short period, world shipping stakeholders found themselves in a totally uncharted territory. With maritime infrastructure in the area damaged and communication channels down, there was scant immediate information on potential radiation effects on crews, cargoes, ships and other maritime outfits at sea or ashore [

20].

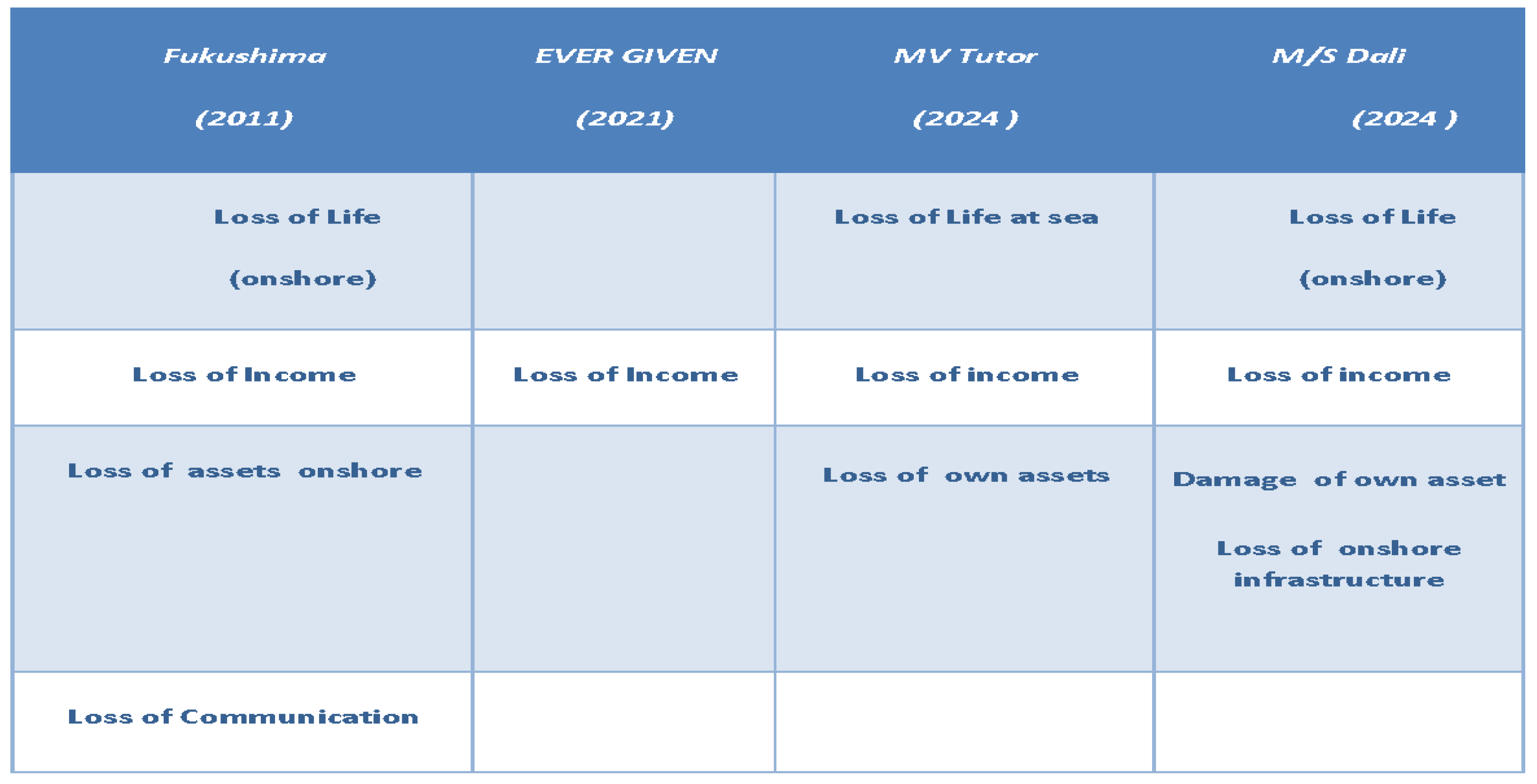

Together with the Fukushima disaster,

Table 2, lists shipping events that are very different in the kind of risks involved, in the degree of their predictability and the scale of their impact. They exemplify the sheer variety of root and secondary risk causes of these incidents including the various role vessels themselves had in generating the main impacts.

Table 2 thus shows events ranging from the Fukushima disaster, which falls in the unknown-unknowns category of

Table 1, to incidents due to shipping hazards where both a Bayesian approach and risk management frameworks are evidently applicable. The grounding of the container vessel EVER GIVEN in March 2021, was a very reduced form of the previous Canal closures during 1956-7 and from 1967 to 1975 of very brief duration, without fatalities or critical damage to the vessel or the infrastructure. However, international media frenzy regarding the potential impact of the incident on shipping, world trade, and port businesses including outcomes for the Suez Canal authority itself, underlined that at least some of the dimensions of uncertainty as presented in

Figure 2 had become evident beyond experts and the industry. It also illustrated the global dimension of shipping risk today and the increased dependence on world trade flow regularity. This strong dependence follows from the geographical fragmentation of industrial production stages and the new international division of labour between older and declining industrial poles and the emerging and already emerged ones in Asia.

The EVER GIVEN grounding should be classified in the first column of “known-knowns” of

Table 1, although the root causes of the previous closures mentioned above related to hostilities in the region which would put those events in the “Known-unknowns” category. Similarly, the extension of recent hostilities in the Middle East to armed attacks by Houthis on non-military vessels in the Red Sea were the root cause of the MV Tutor sinking with severe consequences such as loss of life.

While the root causes of the shocks in the first three columns of

Table 2 underline the role of exogenous factors i.e., factors with no links to the workings of the economy according to the 1942 Zuellig definition, included in [

24], the case of the fourth incident is different. The collision of the M/S Dali in March 2024 onto the Francis Scott Key Bridge in the Baltimore area, which had grievous repercussions due to the loss of life following the collapse of the bridge - an accident which received extensive media coverage - falls in the “known-knowns” operational hazards of shipping operations and may happen despite the efforts to eliminate them.

The range of these selected incidents which became well-known beyond the maritime scene, share common consequences with very different root causes and chains of events. It is from such consequences that shipping businesses need to recover every time. With“unknown-unknowns” shocks, affected parties are put to additional tests, however, by the chaotic circumstances involving these rare disastrous events, where root causes or fault trees may not even be possible to distinguish or formulate respectively. In such settings the degree of embedded resilience becomes the critical element defining their ability to recover.

3.2. Business Resilience in an Industry Environment Exposed to Global Risk

There are many aspects on which the definition of resilience in the context of shipping can be based. One such definition focuses on the key constituent elements of resilience i.e., strength, and flexibility [

19]. On the one hand, strength is essential for the ability to substitute or draw on new resources to maintain or restore business continuity. On the other hand, when conversion is the inevitable outcome, flexibility is the key feature that an organisation must exhibit.

Other recent analyses [

25] , refer to business continuity as the alternative expression to denote organisational resilience. Such a reference to alternate descriptions of resilience allows them to comment - based on remarks about port resilience in [

26] – that, in the case of ports, resilience needs to have a broader perspective that includes unanticipated types of threats. Ports have increasingly resorted to Decision Support Systems (DSS) in the form of digital twins or through simpler systems in order to follow the best path of decision and action possible, especially in view of their vulnerability to the vagaries of climate change [

27]. Ports may be just a nodal interface between ships and cargoes, but a critical one as well, as any disruption affecting reflects across parts or all of the maritime supply chain. The management of port vulnerabilities is compounded by the vast range of combinations of risk factors which may affect either - or both - cargoes and vessels visiting or transiting terminals.

While the nature and number of risk sources, whether compounded or not, are difficult to contain across either the wider maritime supply chain or just shipping, critical factors for business continuity are commonly much more limited. Such factors involve mainly essential resources and processes for the production of maritime services. Classifying them by type and ranking them in order of importance allows one, even in the absence of formal DSS and in the presence of “unknown-unknown” type risks, to increase preparedness independently of the root cause. Thus one may proceed faster to identifying the nature and level of impact induced as well as the recovery or conversion options still available, if any.

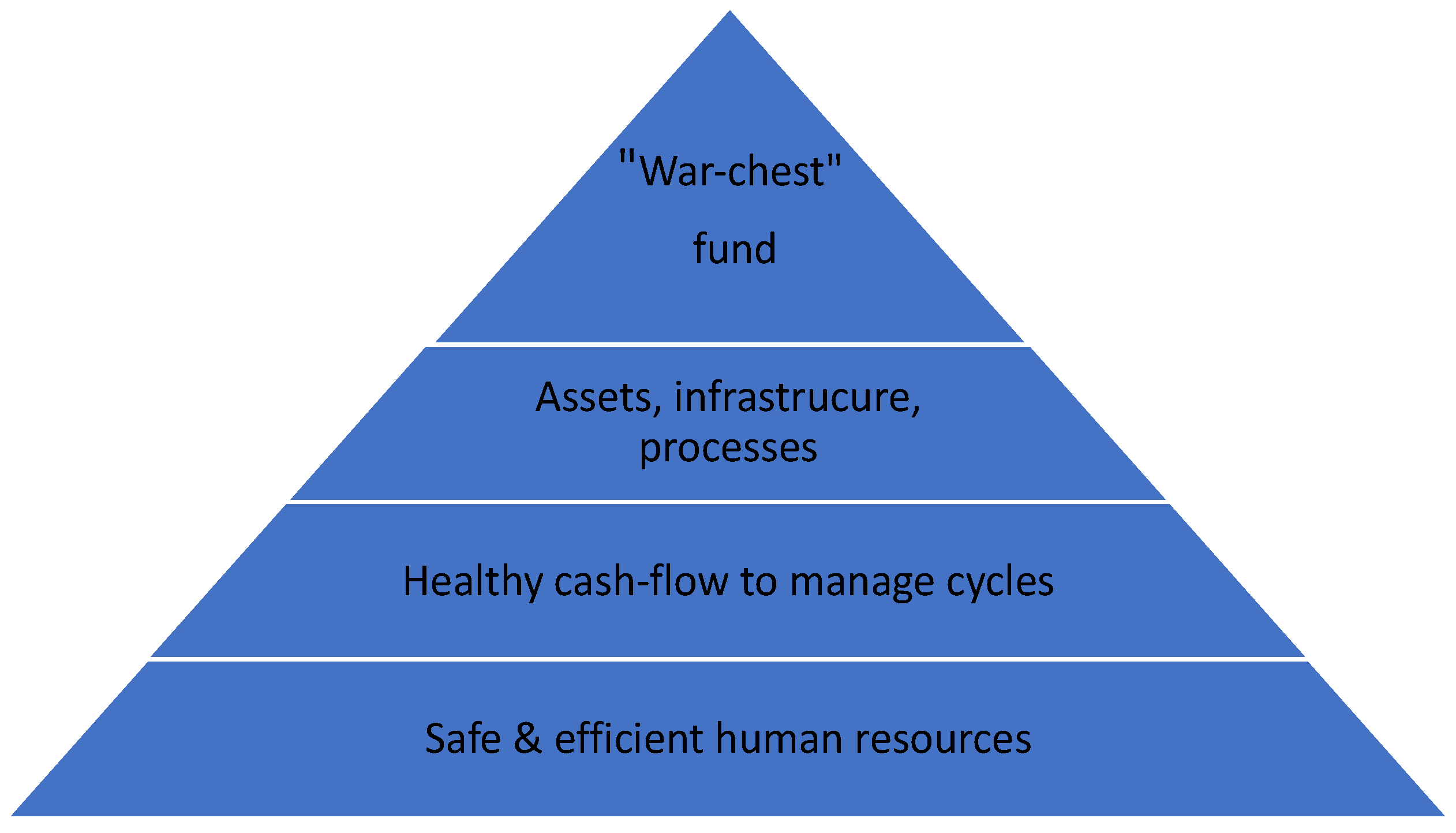

4. A Consequence-Based Generic Approach in an “All-Inclusive” Risk Perspective

Whether originating from low-probability sudden causes or from high-probability cyclical ones, critical consequences for business continuity are well-delimited and common across industries with the outcome depending on how resilient the specific economic unit affected is at the time when it is impacted by the shock.

Resilience in cyclical uncertain environments such as the one of shipping - can be further broken down to several essential components as included in

Figure 4. In terms of strength, resilience essentially refers to the elements which build it:

a. Managing cash-flow appropriately through the cycles within which shipping historically operates

b. Creating a liquidity “war-chest” as cash reserves not only allow shipping companies to circumnavigate the most severe crises, but also to proceed to asset-play moves on ships with lower leverage, a critical element for remaining strong in volatile markets.

However, in building the resilience pyramid of

Figure 4, the base is human resources which are the

conditio sine qua non for business continuity ; these resources incorporate entrepreneurial, managing and production skills and embody the ability to develop, adjust, restore, or convert the business in the presence of both business challenges and opportunities.

In a nutshell, the state of its human resources defines the degree of flexibility of the business in the way to recover, convert or, if the assessment of critical consequences so suggests, even exit completely from the market following a significant shock.

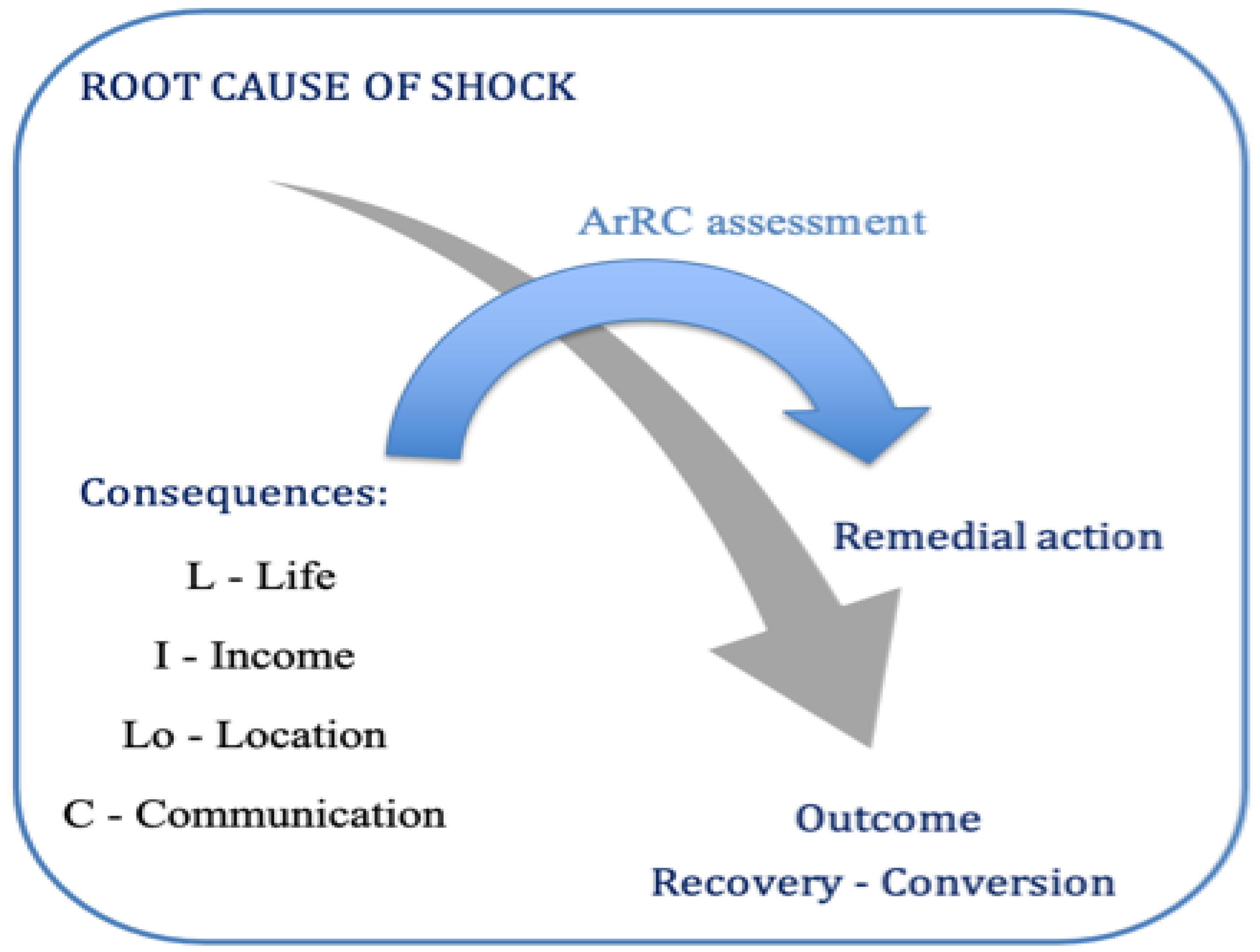

4.1. Known Consequences of Unknown Causes: Reversing the Perspective

Following the structure of the pyramid in

Figure 4 in illustrating the components of resilience a short list of critical consequences emerges directly readily codified as Life, Income, Location, Communication (L.I.Lo.C/LILoc):

Life

The first and foremost critical consequence is related to the impact on the health and safety of the human resource. This prioritisation may be construed as being founded on ethical grounds; yet the life loss, health effects or other types of incapacitation of members of the human resource through piracy, hostage taking etc. not only put human lives at risk but have a tremendous impact on business continuity which is in general largely affected by safety and security factors [

28].

Income

The cessation or drastic and sudden reduction in revenue streams is the second most critical consequence as business continuity will depend on the balance between the extent of this reduction, its duration and on eventual company reserves and assets easily transformable to funds that will secure business continuity.

Location

The integrity of assets and infrastructures at impacted locations and processes come third since outsourcing possibilities, which are more easily available on a global basis exist for all types of production activities, along with insurance, may allow business continuity or provide funds for recovery. The level of production network integrity, including processes and their infrastructure, is critical for assessing recovery or conversion as the way ahead.

Communication

In the context of global shipping supply chains and of increasingly data-based shipping management systems, IT/communication breakdown emerges as fourth in severity for business continuity. While channels of communication have proliferated severe disruption due to natural phenomena, they may affect survivability of critical business resources including above all the safety of human resources.

4.2. An Assessment-Reaction-Recovery-Conversion (ArRC) Framework for Business Shipping Risk

An ArRC framework focuses on characteristics important for resilience whatever the cause of the negative consequences. An appropriate level of redundancy in the system, alternate locations for transfer of operations, flexibility in the organisation and operation and the building of financial risk management reserves are examples corresponding to the four LILoC areas of critical consequences above.

Figure 5, below, highlights visually the independence of the overarching ArRC approach from the root cause of shocks experienced as it turns the focus of the initial reaction to identifying the number, nature, and magnitude of critical consequences previously mapped.

This allows a speedier immediate first-response remedial reaction focusing the attention on the most critical among the consequences, allowing in parallel to gauge the odds of recovery versus conversion or exit at the end of the ArRC process as the potentially prevailing outcome.

The ArRC approach can incorporate methodological tools - such as Key Indicators or other suitable methods for immediate estimates/measurements of the magnitude of each critical consequence - and is compatible with all available risk management approaches including any functional Decision Support Systems and adapt toolkits such as the Risk Based Planning Approach that have been devised for natural hazards [

29].

5. Conclusions

As the major threats in terms of impact on an organisation can be identified more easily than combinations and permutations of factors that may shape risk, this generic approach can assist in focusing more on major negative consequences as well as in the preparatory drawing of alternative plans to contain such consequences. Adopting such an approach may assist in addressing a wider range of risks and in increasing resilience along with reducing the time to reach the final recovery position.

A generic consequence-based approach of risk in the form of the easy to communicate and understand ArRC presented in the previous section is suggested as the best starting point to establish a business culture with increased preparedness for and understanding of the vulnerabilities of each entity concerned. The ArRC approach being geared towards shock consequences instead of root causes and event trees - which may not be possible to anticipate beforehand due to the potentially “unknown-unknown” root causes – allows for building a risk management culture of consequence prioritisation and first-response reaction plans.

Shipping is a complex international industry with constant interaction with the vagaries of both the natural and the human-made world. As uncertainty has increased to a new level in the context of a globalised growing world network, preparedness can be maximised and time to recovery minimised, if risks of the genuinely unknown-unknown type are considered through the consequence angle prompting to build sufficient redundancy in the system to allow for either recovery or for facilitating conversion. Further research can elucidate the degree to which consequence-based risk management is incorporated in contingency plans of shipping businesses and explore whether an open-risk and consequence specific general framework such as the proposed ArRC may result in more efficient, quick, and robust response to sudden shocks with critical consequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T. and Si.S.; methodology, H.T and Si.S.; formal analysis, H.T.; investigation, H.T.; resources, H.T. and Si.S; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.; writing—review and editing, Si.S.; visualization, H.T. and Si.S. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. .

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

This article is a revised, updated and expanded version of a paper entitled Consequence-based risk management in shipping: a proposed ArRC approach which was presented at the IAME 2021 Conference, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 25-27 November 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hollnagel, E. FRAM, the functional resonance analysis method: modelling complex socio-technical systems; Ashgate Publishing Ltd: Aldershot, Hampshire, UK, 2012.

- Berner, C.; Flage, R. Strengthening quantitative risk assessments by systematic treatment of uncertain assumptions. Reliab Eng Syst Safe 2016, 151, 46-59. [CrossRef]

- Thanopoulou, H.; Strandenes, S.P. Consequence-based risk management in shipping: a proposed ArRC approach. Paper presented at the IAME 2021, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. 25-27 November 2021. Available online https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356646154_Consequence-based_risk_management_in_shipping_a_proposed_ArRC_approach, (accessed 9 November 2024).

- UNDRR, United Nations, Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. 2015. Available online from https://www.undrr.org/media/16176/download?startDownload=20240708. (Last accessed 8 November 8, 2024).

- Froot, K. A.; Scharfstein D. ; and Stein J. C. A framework for risk management. J. Appl. Corp. Finance 1994, 7(3), 22-33.

- Kavussanos, M.G., Business Risk Measurement and Management in the Cargo Carrying Sector of the Shipping Industry – An Update. In: Handbook of Maritime Economics and Business; Editor Grammenos C.T.; Lloyds List: London, UK, 2010, 709-743.

- Kavussanos, M.G.; Visvikis, I..D. Derivatives and Risk Management in Shipping; Witherbys Publishing, London, UK, 2006.

- Alizadeh, A.; Nomikos, N., Shipping derivatives and risk management; Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2009.

- Mokhtari, K..; Ren, J.; Roberts, C.; Wang, J. Decision support framework for risk management on seaports and terminals using fuzzy set theory and evidential reasoning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39(5), 5087-5103.

- Butterworth, M.; Reddaway, R; Benson, T. Corporate governance–a guide for insurance and risk managers; Association of Insurance and Risk Management: London, UK, 1996.

- Rumsfeld, D.; News Briefing –Secretary Rumsfeld and Gen. Myers, United States Department of Defense. 2002. (accessed on 14 May 2021) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REWeBzGuzCc.

- Taleb, N.N. The Black Swan. The impact of the highly improbable; Penguin books: London, .2007.

- Kaplan, S.; Garrick, B.J. On the quantitative definition of risk. Risk Anal. 1981, 1(1), 11–27. [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, S.N.; Venkataraman, R. Strategic risk Management in Ports. In: Risk management in port operations, logistics and supply chain security; Bichou, K.; Bell, M.; Evans, A.; Informa Law from Routledge Press, Oxon, UK, 2013, 335-345.

- IDB (Inter-American Development Bank) Risk management for cargo and passengers. Technical Notes IDB-TN-294. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Risk-Management-for-Cargo-and-Passengers-A-Knowledge-and-Capacity-Product.pdf (Accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Vairo, T.; Quagliati, M.; Del Giudice, T.; Barbucci, A.; Fabiano, B.. From land-to water-use-planning: A consequence based case-study related to cruise ship risk. Saf. Sci. 2017, 97, 120-133. [CrossRef]

- Giovinazzi, S.; Wenzel, H.; Powell, D.; Lee, J.S. Consequence-based decision making tools to support natural hazard risk mitigation and management: evidence of needs following the Canterbury (NZ) Earthquake sequence 2010-2011, and initial activities of an open source software development Consortium. Paper presented at the 2013 NZSEE Conference, New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering’s 2013 Technical Conference and AGM, Wellington, New Zealand, 26-28 April 2013.

- UNCTAD. 2024. Review of Maritime Transport, UNCTAD, Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Thanopoulou, H.; Strandenes, S.P. A theoretical framework for analysing long-term uncertainty in shipping. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2017, 5(2), 325-331. [CrossRef]

- Georgoulis, G.; Thanopoulou, H.,; Vanelslander, T., Routing and Port choices in an uncertain environment. Proceedings of ECONSHIP, Chios Island, Greece, 22-24 June 2011.

- BBC Fukushima disaster. What happened at the nuclear plant. Available on line: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-56252695 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Okyar, H.B. International survey of government decisions and recommendations following Fukushima. NEA News 2011, 29(2), 21-22.

- Wang, X.; Kato, H.; Shibasaki, R.. Risk perception and communication in international maritime shipping in Japan after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant disaster. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2330(1), 87-94. [CrossRef]

- Faust, P., The Impact of Exogenous Factors; Institute of Shipping Economics: Bremen, Germany, 1976.

- Vanlaer, N.; Albers, S.; Guiette, A.; Maryissen, S. An organizational resilience perspective on ports as critical infrastructures. In Proceedings of The Port and Maritime Sector: Key Developments and Challenges Conference, SIG2- World Conference on Transport Research Society, Antwerp, the Netherlands, 2-4 May 2021.

- Notteboom, T.; Haralambides, H.E. Port management & governance in a post- COVID-19 era: quo vadis? Marit Econ Logist. 2020, 22, 329-352.

- Polydoropoulou, A.; Bouhouras, E..; Karakikes, I.; Papaioannou, G. July. Enhancing Climate Resilience in Maritime Ports: A Decision Support System Approach. In Computational Science and Its Applications - ICCSA 2024 workshops, Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications workshops, Hanoi, Vietnam, 1-4 July; Gervasi,O.;Murgante, B.; Garau, C.; Taniar, D.; Rocha, A.M.A.; Faginas Lago, M.N.; Cham: Springer Nature, Switzerland. 2024, 241-252.

- Gibb, F.; and Buchanan, S. A framework for business continuity management. Int. J. Inf. Manage 2006, 26(2), 128-141. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, W.SA.; Kilvington, M. Innovative land use planning for natural hazard risk reduction: A consequence-driven approach from New Zealand. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2010, 18, 244-255. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).