Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

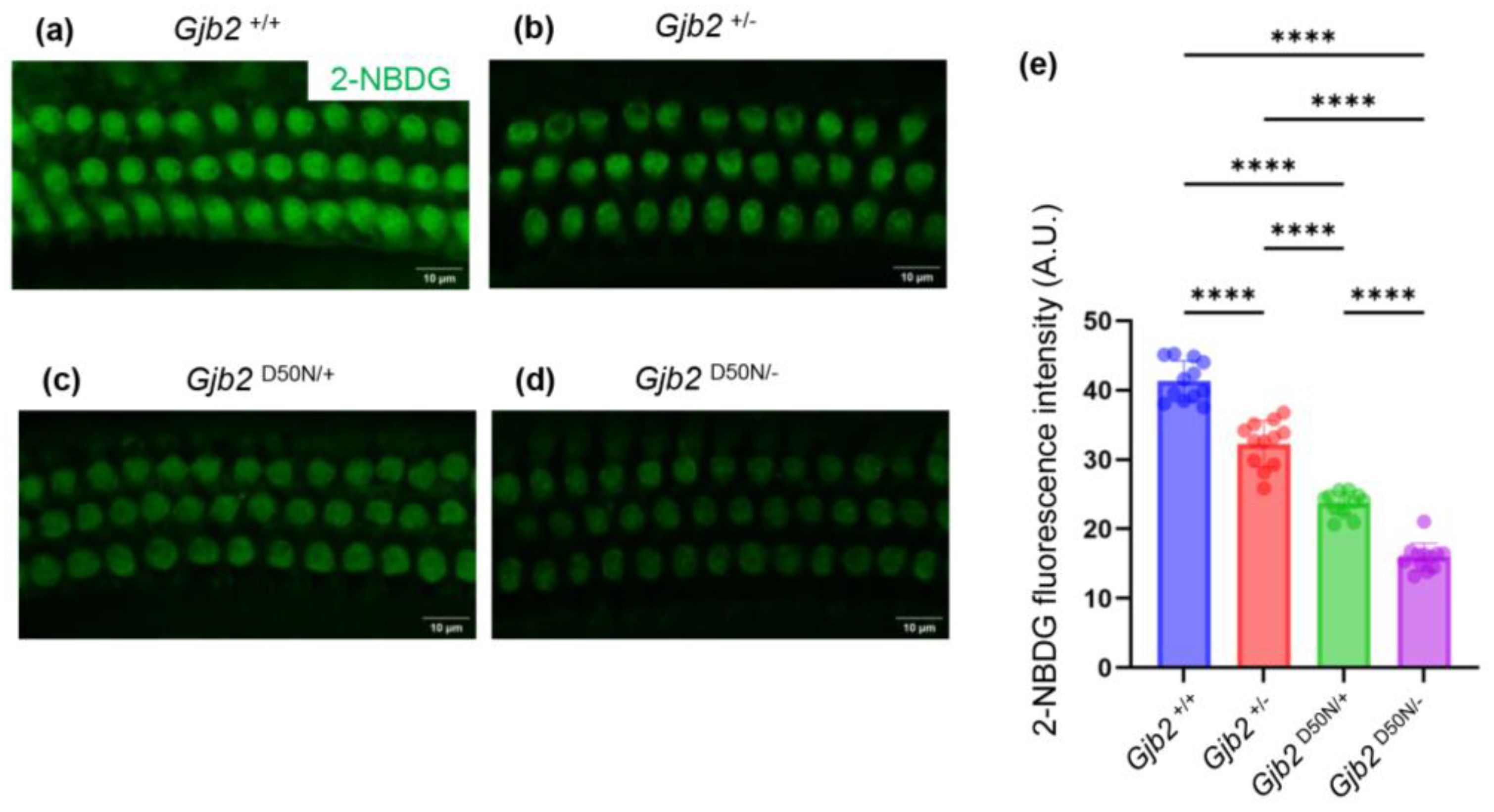

The GJB2 gene, which encodes the Connexin26 (Cx26), is the gene most frequently linked to hearing loss. Individuals carrying variants in the GJB2 gene may experience either congenital hearing loss or last-onset progressive hearing loss. The underlying reasons for the variability in hearing remain poorly understood. Current research primarily focuses on conditional knockout mouse models, which generally exhibit moderate to severe hearing loss. To elucidate the mechanisms by which Cx26 variants contribute to mild to moderate hearing loss, this study established a mouse model, the Gjb2D50N/- mice. Auditory brainstem response (ABR) indicated that the Gjb2D50N/- mice led to a mild to moderate increase in hearing thresholds. Further investigations demonstrated that in the Gjb2D50N/- mice, the gap junction plaques (GJPs) between supporting cells were fragmented, and the capacity of outer hair cells (OHCs) to uptake 2-NBDG (a glucose analog) was reduced. In conclusion, we hypothesize that the mild to moderate hearing loss associated with Cx26 variants may not be attributable to structural abnormalities within the cochlea, but rather to dysfunction of GJPs, which compromises the energy supply to OHCs. In this study, we first established a Gjb2 compound heterozygous mouse model that causes mild to moderate hearing loss, for subsequent intervention and treatment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Models

2.2. Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR)

2.3. Cochlear Tissue Preparation and Immunofluorescent Labeling

2.4. Assessment of In Vivo 2-NBDG Uptake in the HCs

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Gjb2D50N/- Mice Showed Mile to Moderate Hearing Loss

3.2. The Gjb2D50N/- Mice Showed no Significant HCs and SGNs Loss

3.3. CD45+Cells in the Organ of Corti in the Gjb2D50N/- Mice Underwent Morphological Changes

3.4. The Gjb2D50N/- Mice Show Shortened GJPs

3.5. The Gjb2D50N/- Mice Decreased Intake of 2-NBDG

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Butcher, E.; Dezateux, C.; Cortina-Borja, M.; Knowles, R.L. Prevalence of permanent childhood hearing loss detected at the universal newborn hearing screen: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0219600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koffler, T.; Ushakov, K.; Avraham, K.B. Genetics of Hearing Loss: Syndromic. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2015, 48, 1041–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, A.E.; Hildebrand, M.S.; Schaefer, A.M.; Smith, R.J.H. Genetic Hearing Loss Overview. In GeneReviews(®); Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Gripp, K.W., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA.

- Copyright © 1993-2024, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.: Seattle (WA), 1993.

- Chan, D.K.; Chang, K.W. GJB2-associated hearing loss: systematic review of worldwide prevalence, genotype, and auditory phenotype. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, E34–E53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, T.; Kimura, R.S.; Paul, D.L.; Takasaka, T.; Adams, J.C. Gap junction systems in the mammalian cochlea. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2000, 32, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, K.; Yum, S.W.; Kurebayashi, N.; Muraki, M.; Ogawa, K.; Karasawa, K.; Miwa, A.; Guo, X.; Gotoh, S.; Sugitani, Y.; et al. Assembly of the cochlear gap junction macromolecular complex requires connexin 26. J Clin Invest 2014, 124, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, D.J.; Forge, A. Connexins and gap junctions in the inner ear--it's not just about K⁺ recycling. Cell Tissue Res 2015, 360, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramello, M.; Piazza, V.; Bukauskas, F.F.; Pozzan, T.; Mammano, F. Impaired permeability to Ins(1,4,5)P3 in a mutant connexin underlies recessive hereditary deafness. Nat Cell Biol 2005, 7, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korver, A.M.H.; Smith, R.J.H.; Van Camp, G.; Schleiss, M.R.; Bitner-Glindzicz, M.A.K.; Lustig, L.R.; Usami, S.-I.; Boudewyns, A.N. Congenital hearing loss. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 16094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Z.; Xia, X.J.; Ke, X.M.; Ouyang, X.M.; Du, L.L.; Liu, Y.H.; Angeli, S.; Telischi, F.F.; Nance, W.E.; Balkany, T.; et al. The prevalence of connexin 26 ( GJB2) mutations in the Chinese population. Hum Genet 2002, 111, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdieh, N.; Rabbani, B. Statistical study of 35delG mutation of GJB2 gene: a meta-analysis of carrier frequency. Int J Audiol 2009, 48, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, A.; Lu, Y. Association between the p.V37I variant of GJB2 and hearing loss: a pedigree and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 46681–46690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, T.G.; Brazhkina, N.B.; Bliznech, E.A.; Bakhshinyan, V.V.; Polyakov, A.V.; Tavartkiladze, G.A. Phenotype in a patient with p.D50N mutation in GJB2 gene resemble both KID and Clouston syndromes. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 2016, 81, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janecke, A.R.; Hennies, H.C.; Günther, B.; Gansl, G.; Smolle, J.; Messmer, E.M.; Utermann, G.; Rittinger, O. GJB2 mutations in keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome including its fatal form. Am J Med Genet A 2005, 133a, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Barak, E.; Mwassi, B.; Zagairy, F.; Danial-Farran, N.; Khayat, M.; Tatour, Y.; Ziv, M. Parental mosaic cutaneous-gonadal GJB2 mutation: From epidermal nevus to inherited ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. The Journal of dermatology 2022, 49, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Sun, Y.; Lin, X.; Kong, W. Down regulated connexin26 at different postnatal stage displayed different types of cellular degeneration and formation of organ of Corti. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 445, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Xie, L.; Xu, K.; Cao, H.Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, X.X.; Sun, Y.; Kong, W.J. Developmental abnormalities in supporting cell phalangeal processes and cytoskeleton in the Gjb2 knockdown mouse model. Disease models & mechanisms 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Xu, K.; Xie, L.; Chen, S.; Sun, Y. The Reduction in Microtubule Arrays Caused by the Dysplasia of the Non-Centrosomal Microtubule-Organizing Center Leads to a Malformed Organ of Corti in the Cx26-Null Mouse. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Z.; Jin, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, K.; Xie, L.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, X.H.; Sun, Y.; Kong, W.J. F-Actin Dysplasia Involved in Organ of Corti Deformity in Gjb2 Knockdown Mouse Model. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2021, 14, 808553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, H.D.; Jung, D.; Bützler, C.; Temme, A.; Traub, O.; Winterhager, E.; Willecke, K. Transplacental uptake of glucose is decreased in embryonic lethal connexin26-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 1998, 140, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Lu, J.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, G.-L.; Yang, T.; Song, L.; et al. Hearing consequences in Gjb2 knock-in mice: implications for human p.V37I mutation. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 7416–7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Lu, Y.-C.; Chan, Y.-H.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Lin, S.-W.; Liu, T.-C.; Hsu, C.-J.; Chen, P.-L.; Yang, L.-W.; et al. Simulation-predicted and -explained inheritance model of pathogenicity confirmed by transgenic mice models. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2023, 21, 5698–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Cui, C.; Liao, R.; Yin, X.; Wang, D.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, L.; Yan, M.; Zhou, J.; et al. The pathogenesis of common Gjb2 mutations associated with human hereditary deafness in mice. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 2023, 80, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoshita, A.; Iizuka, T.; Okamura, H.O.; Minekawa, A.; Kojima, K.; Furukawa, M.; Kusunoki, T.; Ikeda, K. Postnatal development of the organ of Corti in dominant-negative Gjb2 transgenic mice. Neuroscience 2008, 156, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Chen, S.; Xie, L.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, X.Z.; Bai, X.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X.H.; Sun, Y. The protective effects of systemic dexamethasone on sensory epithelial damage and hearing loss in targeted Cx26-null mice. Cell death & disease 2022, 13, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, W.-L.; Gu, Y.; Common, J.E.A.; Aasen, T.; O'Toole, E.A.; Kelsell, D.P.; Zicha, D. Connexin interaction patterns in keratinocytes revealed morphologically and by FRET analysis. J Cell Sci 2005, 118, 1505–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurman, D.L.; Glazewski, L.; Gumpert, A.; Zieske, J.D.; Richard, G. In vivo and in vitro expression of connexins in the human corneal epithelium. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2005, 46, 1957–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, W.; Gonzalez, J.; Liu, Y.; Harris, A.L.; Contreras, J.E. Insights on the mechanisms of Ca(2+) regulation of connexin26 hemichannels revealed by human pathogenic mutations (D50N/Y). The Journal of general physiology 2013, 142, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, H.A.; Kraujaliene, L.; Verselis, V.K. A pore locus in the E1 domain differentially regulates Cx26 and Cx30 hemichannel function. The Journal of general physiology 2024, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taki, T.; Takeichi, T.; Sugiura, K.; Akiyama, M. Roles of aberrant hemichannel activities due to mutant connexin26 in the pathogenesis of KID syndrome. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 12824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Tang, W.; Ahmad, S.; Zhou, B.; Lin, X. Gap junction mediated intercellular metabolite transfer in the cochlea is compromised in connexin30 null mice. PLoS One 2008, 3, e4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeckx, R.L.; Huygen, P.L.M.; Feldmann, D.; Marlin, S.; Denoyelle, F.; Waligora, J.; Mueller-Malesinska, M.; Pollak, A.; Ploski, R.; Murgia, A.; et al. GJB2 mutations and degree of hearing loss: a multicenter study. Am J Hum Genet 2005, 77, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-M.; Ko, H.-C.; Tsou, Y.-T.; Lin, Y.-H.; Lin, J.-L.; Chen, C.-K.; Chen, P.-L.; Wu, C.-C. Long-Term Cochlear Implant Outcomes in Children with GJB2 and SLC26A4 Mutations. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0138575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Q.; Tang, W.; Kim, Y.; Lin, X. Timed conditional null of connexin26 in mice reveals temporary requirements of connexin26 in key cochlear developmental events before the onset of hearing. Neurobiol Dis 2015, 73, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Wu, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, L.; Hou, S.; Yang, J. Pathological mechanisms of connexin26-related hearing loss: Potassium recycling, ATP-calcium signaling, or energy supply? Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2022, 15, 976388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posukh, O.L.; Maslova, E.A.; Danilchenko, V.Y.; Zytsar, M.V.; Orishchenko, K.E. Functional Consequences of Pathogenic Variants of the GJB2 Gene (Cx26) Localized in Different Cx26 Domains. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liang, C.; Chen, J.; Zong, L.; Chen, G.-D.; Zhao, H.-B. Active cochlear amplification is dependent on supporting cell gap junctions. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, H.-B. Progressive age-dependence and frequency difference in the effect of gap junctions on active cochlear amplification and hearing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 489, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallos, P.; Wu, X.; Cheatham, M.A.; Gao, J.; Zheng, J.; Anderson, C.T.; Jia, S.; Wang, X.; Cheng, W.H.Y.; Sengupta, S.; et al. Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron 2008, 58, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Chen, S.; Xu, K.; Cao, H.Y.; Du, A.N.; Bai, X.; Sun, Y.; Kong, W.J. Reduced postnatal expression of cochlear Connexin26 induces hearing loss and affects the developmental status of pillar cells in a dose-dependent manner. Neurochemistry international 2019, 128, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xu, K.; Xie, L.; Cao, H.Y.; Wu, X.; Du, A.N.; He, Z.H.; Lin, X.; Sun, Y.; Kong, W.J. The spatial distribution pattern of Connexin26 expression in supporting cells and its role in outer hair cell survival. Cell death & disease 2018, 9, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Xie, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, K.; Bai, X.; Chen, S.; Sun, Y. Abnormal Innervation, Demyelination, and Degeneration of Spiral Ganglion Neurons as Well as Disruption of Heminodes are Involved in the Onset of Deafness in Cx26 Null Mice. Neuroscience bulletin 2024. [CrossRef]

- Haack, B.; Schmalisch, K.; Palmada, M.; Böhmer, C.; Kohlschmidt, N.; Keilmann, A.; Zechner, U.; Limberger, A.; Beckert, S.; Zenner, H.P.; et al. Deficient membrane integration of the novel p.N14D-GJB2 mutant associated with non-syndromic hearing impairment. Hum Mutat 2006, 27, 1158–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuloushi, A.; Lovgren, M.L.; Steel, A.; Yeoh, Y.; Waters, A.; Zamiri, M.; Martin, P.E. A heterozygous mutation in GJB2 (Cx26F142L) associated with deafness and recurrent skin rashes results in connexin assembly deficiencies. Experimental dermatology 2020, 29, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thönnissen, E.; Rabionet, R.; Arbonès, M.L.; Estivill, X.; Willecke, K.; Ott, T. Human connexin26 (GJB2) deafness mutations affect the function of gap junction channels at different levels of protein expression. Hum Genet 2002, 111, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, M.; Auth, T.; Gehrt, A.; Bosen, F.; Körber, I.; Strenzke, N.; Moser, T.; Willecke, K. The connexin26 S17F mouse mutant represents a model for the human hereditary keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. Human molecular genetics 2011, 20, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.J.; Liu, X.Z.; Tu, L.; Sun, Y. Cytomembrane Trafficking Pathways of Connexin 26, 30, and 43. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Salmon, M.; Ott, T.; Michel, V.; Hardelin, J.P.; Perfettini, I.; Eybalin, M.; Wu, T.; Marcus, D.C.; Wangemann, P.; Willecke, K.; et al. Targeted ablation of connexin26 in the inner ear epithelial gap junction network causes hearing impairment and cell death. Curr Biol 2002, 12, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangemann, P. K+ cycling and the endocochlear potential. Hear Res 2002, 165, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, T.; Kure, S.; Ikeda, K.; Xia, A.-P.; Katori, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Kojima, K.; Ichinohe, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Aoki, Y.; et al. Transgenic expression of a dominant-negative connexin26 causes degeneration of the organ of Corti and non-syndromic deafness. Human molecular genetics 2003, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moley, K.H.; Mueckler, M.M. Glucose transport and apoptosis. Apoptosis 2000, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fetoni, A.R.; Zorzi, V.; Paciello, F.; Ziraldo, G.; Peres, C.; Raspa, M.; Scavizzi, F.; Salvatore, A.M.; Crispino, G.; Tognola, G.; et al. Cx26 partial loss causes accelerated presbycusis by redox imbalance and dysregulation of Nfr2 pathway. Redox biology 2018, 19, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carette, D.; Gilleron, J.; Denizot, J.-P.; Grant, K.; Pointis, G.; Segretain, D. New cellular mechanisms of gap junction degradation and recycling. Biol Cell 2015, 107, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, G.; Zheng, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhang, W.; Ren, J.; Ma, S.; Sun, S.; He, X.; Wang, Q.; Ji, Z.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic atlas of mouse cochlear aging. Protein Cell 2023, 14, 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Chen, S.; Bai, X.; Xie, L.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, X.Z.; Wang, X.H.; Kong, W.J.; Sun, Y. Degradation of cochlear Connexin26 accelerate the development of age-related hearing loss. Aging cell 2023, 22, e13973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Shen, L.; Huang, X.; Lin, X.; Kong, W. Reduced expression of Connexin26 and its DNA promoter hypermethylation in the inner ear of mimetic aging rats induced by d-galactose. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 452, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-M.; Liang, C.; Chen, J.; Fang, S.; Zhao, H.-B. Cx26 heterozygous mutations cause hyperacusis-like hearing oversensitivity and increase susceptibility to noise. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadf4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Q.; Tang, H.; Hu, S.; Gao, K.; et al. AAV1-hOTOF gene therapy for autosomal recessive deafness 9: a single-arm trial. Lancet 2024, 403, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Tan, F.; Zhang, L.; Lu, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhai, Y.; Lu, Y.; Qian, X.; Dong, W.; Zhou, Y.; et al. AAV-Mediated Gene Therapy Restores Hearing in Patients with DFNB9 Deafness. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2306788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Chu, C.; Qi, J.; Li, W.; You, D.; Li, K.; Chen, X.; Zhao, W.; Cheng, C.; Liu, X.; et al. AAV-ie enables safe and efficient gene transfer to inner ear cells. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Chu, C.; Tan, F.; Yu, Z.; Ke, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, X.; et al. AAV-ie-K558R mediated cochlear gene therapy and hair cell regeneration. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, Y.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Li, N.; Xu, L.; et al. AAV-mediated Gene Cocktails Enhance Supporting Cell Reprogramming and Hair Cell Regeneration. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2304551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Hu, Y.; Du, H.; Han, S.; Ren, L.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; Zheng, S.; Cui, Q.; et al. Tissue engineering strategies for spiral ganglion neuron protection and regeneration. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chang, Q.; Wang, J.; Gong, S.; Li, H.; Lin, X. Virally expressed connexin26 restores gap junction function in the cochlea of conditional Gjb2 knockout mice. Gene Ther 2014, 21, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Ma, X.; Skidmore, J.M.; Cimerman, J.; Prieskorn, D.M.; Beyer, L.A.; Swiderski, D.L.; Dolan, D.F.; Martin, D.M.; Raphael, Y. GJB2 gene therapy and conditional deletion reveal developmental stage-dependent effects on inner ear structure and function. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2021, 23, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, K.; Bai, X.; Xie, L.; Kong, W.; Sun, Y. PARP inhibitor rescues hearing and hair cell impairment in Cx26-null mice. View 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Q.; Wang, H.; Qi, J.; Sun, S.; Liao, M.; Wu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Cheng, C.; et al. Increased mitophagy protects cochlear hair cells from aminoglycoside-induced damage. Autophagy 2023, 19, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Sun, G.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Han, Y.; Chai, R.; Wang, H. PRDX1 activates autophagy via the PTEN-AKT signaling pathway to protect against cisplatin-induced spiral ganglion neuron damage. Autophagy 2021, 17, 4159–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).