1. Introduction

Cellulose displays a diverse array of material properties in nature, including texture, mechanical response, and transport of water and other small molecules [

1,

2,

3]. These unique attributes are driven by its hierarchical self-assembly, where individual cellulose chains interact and assemble across length-scales to form fibers, bundles, and macroscopic materials [

4,

5]. Inspired by properties observed in nature, researchers have used cellulose to design and fabricate gels and composites for many applications that span fields of polymer science, engineering, and even sensor technology [

4,

6,

7]. Cellulose is also biocompatible, biodegradable, bio-absorptive, and has low toxicity [

8]. Therefore, cellulose and its derivatives have become critical matrix materials for biomedical applications such as drug delivery [

8]. Specifically, oral delivery is a key area of interest because the human body does not readily digest cellulose, creating an opportunity to design drug delivery platforms that will remain stable and provide sustained drug release in the gastrointestinal tract [

9].

Cellulose microgels are typically formed using the dropping technique, where a cellulose solution is extruded dropwise from a syringe to a coagulation bath that causes cellulose to self-assemble and form porous spheres called microgels or beads [

10]. Cellulose with concentrations up to 2 wt% can be fully dissolved in 8 wt% NaOH/urea solutions at low temperatures (-10

[

11,

12]. Even at 2 wt%, cellulose chains assemble into rod-like fibrillar structures in solution [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In the dropping technique, the solution of cellulose, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and urea is dropped into a beaker containing hydrochloric acid (HCl) [

10,

18,

19]. The neutralization of NaOH decreases the solubility of the cellulose, leading to coagulation and microgel bead formation. As the cellulose concentration increases, the aggregate size increases along with the rate of coagulation. After coagulation, the beads are washed, neutralized and either freeze-dried or stored in water. While the methodology is straightforward, the resultant material properties are complex. Numerous experimental factors can negatively impact the properties of the microgels, including dropping height, needle gauge size, the composition and temperature of the coagulation bath, and the concentration and temperature of the cellulose solution [

10,

20,

21]. Even after optimizing these factors, cellulose microgels exhibit high variability in mechanical properties and do not survive

in vitro digestion processes [

22,

23,

24].

One way to fabricate cellulose beads with a homogenous structure, higher network density, and improved mechanical properties using the dropping technique is thermal gelation [

10,

25]. If the temperature is gradually increased, the cellulose solubility decreases, leading to gel formation. When used in conjunction with the dropping technique, thermal gelation stabilizes the cellulose beads due to increased solution viscosity and helps maximize the rate of coagulation [

26]. The physical crosslinking helps limit the movement of polymer chains in the solution as the droplet is introduced to the coagulation bath [

25,

27]. Thermal gelation times are also dependent on the cellulose concentration, where higher concentration decreases the gelation time [

10]. While thermal gelation improves geometric features like circularity, the variability of the pore structure and material properties persists. Thus, more than gel pre-assembly is needed to overcome these material design challenges.

The driving force behind the formation of cellulose beads via the dropping technique is the neutralization of the base solvent (NaOH) with an acidic bath (HCl) [

19]. This neutralization causes the cellulose in the droplet to aggregate and self-assemble, leading to spherical microgels. An overlooked feature of this process is the production of salt, specifically sodium chloride (NaCl), from the neutralization reaction:

NaCl and other ionic salts are known to influence the hydration and assembly of cellulose, where an increase in salt concentration causes the cellulose to form a gel even in NaOH solutions [

28,

29]. This phenomenon is known as the "salting out” effect and is demonstrated by cellulose nanofibers (CNF), cellulose nanocrystals (CNC), and other biopolymers like proteins [

28,

29]. Recently, Arola et al. used experimental and computational techniques to reveal that ionic salts create bridges between cellulose nanofibers, allowing for stronger, more ordered contacts to form between fibrils [

30]. In their study, small deformation oscillatory rheology revealed that CNF suspensions with low NaCl concentrations (0.25-1mM) take longer to recover from stress, while cellulose suspensions with higher NaCl concentrations (above 2 mM) form highly elastic networks that quickly recover from stress [

30]. Overall, Arola et al. concluded that even trace amounts of NaCl significantly influence the self-assembly of CNF and the stress response of the resultant material and plays a critical role in the mechanical variability observed frequently in the literature [

30]. CNCs suspended in solution form a heterogenous mixture where they retain their macroscopic structure and can form larger clusters due to interparticle attractions and hydrogen bonding between the charged groups on the surface of the CNC and water [

31]. CNCs display higher surface area, modulus, and negative surface charge, and a rod-like crystalline structure compared to CNFs [

32]. Cao et al. investigated the aggregation kinetics for CNC suspensions containing monovalent, divalent, and trivalent salts [

33]. At NaCl concentrations above 153 mM, rapid assembly occurs and causes instability in the colloidal suspensions of CNCs [

33].

The prior literature focuses only on CNF and CNC suspensions, but the dropping technique involves a cellulose solution, where cellulose molecules are dissolved in aqueous solutions of NaOH and urea. With the addition of salt, the viscosity of the CNC suspension increases drastically due to an increase in aggregation, leading to a significant decrease in the zeta potential [

34]. In contrast, when CNF are fully dissolved in NaOH/urea solutions, the cellulose chains are freed from the fibrillar structure through the breakage of hydrogen bonds in the crystalline regions, resulting in a homogenous mixture of the smaller cellulose clusters distributed throughout the NaOH solution [

35,

36]. Increasing the salt concentration can then cause the dissolved cellulose to forms larger aggregates and form gel networks [

28,

29,

37,

38]. During the dropping technique, the salt concentration varies rapidly as the neutralization reaction proceeds. Thus, we hypothesize that the salt fluctuations are causing significant changes in aggregation behavior and kinetics, leading to non-uniform internal bead structures and gel networks.

In this work, we explored the addition of salt to cellulose solutions prior to dropping as a tool to tune the micro and macro structure of cellulose microgels. Our goal was to achieve structural uniformity and reduce variability in mechanical properties for microgels fabricated using the dropping technique. To address the instability caused by the salt produced during coagulation in an HCl bath, we added salt to the cellulose solutions to overcome the rapid aggregation that leads to colloidal instability in cellulose solutions. We also compared salt addition to physical methods of aggregation (thermo-gel) to decouple cellulose aggregation caused by the increase in temperature of the coagulation bath from the aggregation caused by ionic salt formation. We show that thermal gelation is not sufficient to overcome the structural irregularities caused by salt formation and that balancing solution viscosity with the addition of salt is highly effective at achieving structural uniformity and reproducible mechanical properties. Additionally, we provide a critical 3-dimensional viewpoint of the effects of salt on the internal structure of cellulose microgel beads.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Fibrous cotton linter pulp cellulose, hydrochloric acid (ACS reagent, 37%), urea, sodium chloride, sodium hydroxide (ACS reagent, > 97%) pellets, pepsin, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, and trypsin were purchased from Millipore Sigma.

2.2. Fabrication of Neat (Control) Cellulose Solutions

Cotton linter pulp was dissolved in a solution of 7 wt% NaOH, 12 wt% urea, and 81 wt% water to obtain an overall solution of 5 wt% cellulose. The solution was transferred to a jacketed beaker connected to a chiller at -10C and allowed to stir until a transparent solution was observed. The solutions were degassed by centrifugation at -10C and 8000 rpm.

2.3. Fabrication of Salt-gel Solutions

Salt pre-gelled (salt-gel) solutions were formed following the same procedure as the neat cellulose solutions with the following modification: NaCl (0.5 wt% (111 mM), 1 wt% (225 mM), 2 wt% (449 mM), and 3 wt% (673 mM)) was added to the solution and stirred until fully dissolved before adding cellulose. The solution was transferred to a jacketed beaker connected to a chiller at -10C and allowed to stir until a transparent solution was observed. The solutions were degassed by centrifugation at -10C and 8000 rpm.

2.4. Fabrication of Thermo-gel Solutions

Thermally pre-gelled (thermo-gel) solutions were formed following the same procedure as the neat cellulose solutions. After degassing, the centrifuge tube is removed and placed in a water bath with the liquid level in the centrifuge tube completely submerged under the water level of the water bath. The bath temperature was set to 25°C, 45°C, or 65°C. Each trial was conducted in triplicate.

2.5. Heat Transfer Modeling for Thermo-gel Solutions

To minimize structural variability caused by heat transfer, Python was used to predict the temperature profile within the centrifuge tube as a function of bath temperature. These computational results were used to determine the water bath temperatures used to fabricate thermo-gels and were validated experimentally. For this model, the initial temperature of the cellulose solution is set to -10C, and heat transfer was modelled as a function of the temperature of the water medium.

To solve the heat equation in cylindrical coordinates, the heat transfer was considered only in the radial (r) direction [

39].

The initial condition is that the temperature of the cellulose solution is -10

C. The first boundary condition is for the outer surface of the centrifuge tube, which is in contact with the water medium, and the conductive heat flux is equal to that of water. The second boundary condition is that, at the center of the tube (

), the temperature gradient over time is finite.

The mathematical method used to solve the heat equation was separation of variables, and the Newton-Raphson method was implemented to find the eigenvalues used to determine the temperature distribution as a function of distance from the center of the centrifuge tube (

and time [

40,

41].

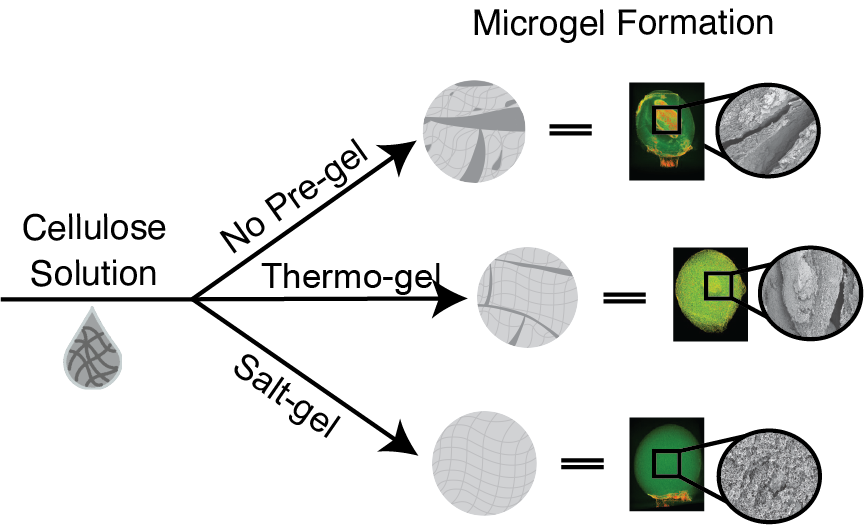

2.6. Microgel Formation via the Dropping Technique

5 mL of cellulose solution (neat, salt-gel, or thermo-gel) was loaded into a syringe and dropped at a flowrate of 0.2 mL/min from a horizontally-oriented 30-gauge needle at a dropping height of 1 cm from a 2 M HCl coagulation bath (

Figure 1). The 2 M HCl coagulation bath was held at

with constant stirring of 100 rpm to prevent the beads from settling at the bottom of the beaker and to ensure uniform concentration throughout the coagulation bath. Once all of the cellulose solution was added to the bath, the cellulose beads were continuously stirred at 100 rpm for 2 hours. The beads were washed with a total of 600 mL of deionized water (200 mL, 3x). After the last wash, a 0.1 M NaOH solution was added dropwise to the DI water bath containing the rinsed beads until a neutral pH was obtained. The beads were removed from the bath and placed in a centrifuge tube with fresh DI water. The centrifuge tube was placed in an incubated shaker at 25

C and an agitation rate of 100 rpm for 24 hours to allow the microgels to equilibrate. Finally, the beads were flash frozen with liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried using a LabConco FreeZone Freeze-Dryer.

2.7. Determination of Viscosity

Approximately 10 mL of cellulose/NaOH/urea solution was placed in a Ubbelohde viscometer, and the time was recorded for the solution to move from one specified point to the another. The viscosity can be calculated using Equation 4

where

is the viscosity of the solution in cP,

is the Ubbelohde viscometer specific constant,

is density in g/cm3, and

is time in seconds [

42].

2.8. Determination of Particle Size, Electrophoretic Mobility (EPM), and Zeta Potential

Particle size and electrophoretic mobility were measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS) via a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS. Zeta potential was then calculated using the Smoluchowski model shown in Equation 5

where

is the viscosity of the solution in cP,

is the electrophoretic mobility in

mcm/Vs,

is the dielectric constant for a cellulose/sodium hydroxide/urea/water mixture (68.03),

is the permittivity of free space (8.85 x 10-12 C2/Jm) [

33,

43,

44].

2.9. Microgel Size and Shape Characterization

Image J was used to measure the diameter of the selected cellulose beads and calculate the volume, area, and perimeter [

45]. The circularity of the beads was quantified using Equation 6,

where

is the circularity,

is the area, and

is the perimeter [

46]. The resulting size and circularity distributions were fitted to a normal distribution and statistical analysis was used to determine statistical significance.

2.10. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The microstructure of neat cellulose, salt-gel, and thermo-gel beads were analysed using a ThermoFisher Scientific Phenom ProX Desktop Electron Microscope with a voltage of 5 kV and a magnification of 2000X or 15000X. Both surface and cross-sectional images were taken. The beads were sputter coated with gold using a Q150T ES Plus Electron Microscopy Sciences Sputter Coater prior to analysis.

2.11. Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) analysis was performed on neat cellulose and salt-gel beads using an INCA X-Stream 2 Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer in combination with a ZEISS EVO50 Scanning Electron Microscope with a voltage of 5 kV. Neat cellulose and salt-gel beads were examined both prior to and after washing to determine the elemental make-up in each sample. Analysis was performed on both the surface and cross-section of the beads to determine if salt was present after fabrication and neutralization (

Table S3).

2.123. D X-ray Computer Tomography (Nano-CT)

Mounted cellulose beads were mounted on toothpicks and scanned with an air filter in a ZEISS Xradia Versa 3D X-ray Computed Tomography (CT) Scanner with a 4X objective. 801 projections were taken as the sample rotated 360 degrees. To increase imagine quality, the binning was set to 8 and the exposure time was set to 0.5 s. A voltage of 50 kV and power of 2 W was used throughout the duration of scanning. At the conclusion of scanning, the 2D projected images were transferred to the ZEISS Scout and Scan Control System software for reconstruction. 360-degree rotations of the 3-D reconstructions were created using FIJI [

47].

2.13. Determination of Droplet Volume

The volume extruded from a syringe and dropped into the HCl coagulation bath was determined by dropping 5 mL of cellulose solution into a 10 mL graduated cylinder. During dropping, the total number of droplets was recorded. Therefore, to determine the volume of a droplet, the overall volume collected in the graduated cylinder was divided by the total number of droplets.

2.14. Simulated Gastrointestinal Tract Environment for Cellulose Beads

Cellulose beads were tested in a simulated gastrointestinal tract environment to understand the swelling and mechanical properties of the beads. Simulated gastric fluid (SGF) was prepared by dissolving 4.5 g of sodium chloride and 1.6 g of pepsin in 500 mL of water [

24]. Simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) was prepared by dissolving 3.4 g of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and 5 g of trypsin in 500 mL of water [

24]. Cellulose beads were first placed in SGF incubated at 37ºC for 2 hours with an 80-rpm agitation. At the conclusion of the two hours, the beads were removed from the SGF and then placed in SIF for 6 hours at 37ºC with an 80-rpm agitation [

37,

38].

2.15. Mechanical Testing

The mechanical properties of neat cellulose, salt-gel, and thermo-gel beads were measured using the FEMTO Tools® Micromechanical Testing and Assembly System after undergoing the simulated gastrointestinal tract. To mechanically test the beads in the simulated gastrointestinal tract, 15 cellulose beads were first placed in SGF incubated at 37ºC for 2 hours with an 80-rpm agitation. At the conclusion of the two hours, the beads were tested via nanoindentation. Then, the beads were incubated in SIF for 6 hours at 37ºC with an 80-rpm agitation prior to undergoing nanoindentation. The Young’s modulus was determined using nanoindentation with a spherical ruby tip probe. Force versus displacement curves were fit to the Oliver-Pharr model to determine the Young’s modulus [

48]. First, the data was fit to a power law expression (Equation 7) using linear regression to determine the fitting parameters,

where

is the force,

is the displacement,

and

are fitting parameters, and

is the final unloading displacement. Next, the derivative of Equation 7 was taken to determine the stiffness of the unloading curve (Equation 8),

where

is the stiffness,

is the maximum displacement, and

and

are fitting parameters. The calculated stiffness from Equation 8 is then used to determine the contact depth (Equation 9),

where

is the contact depth,

is the punch geometry fitting parameter based on the probe, and

is the maximum load. Since a spherical ruby tip probe is used, the punch geometry fitting parameter is 0.75. The contact area for a spherical probe is calculated using Equation 10,

where

is the contact area and

is the radius of the tip of the probe. The radius of the spherical tip ruby probe used was 125 µm. Next, the reduced elastic modulus is calculated using Equation 11,

where

is the reduced elastic modulus and

is a fitting parameter based on geometry equal to 1 for spherical tips. Finally, the reduced elastic modulus is used to calculate the Young’s modulus (Equation 12),

where

is the Young’s modulus and

is the Poisson’s ratio for cellulose [

48].

2.16. Swelling Experiments for Cellulose Beads in a Simulated Gastrointestinal Tract Environment

Prior to incubating beads in SGF and SIF, images of fifteen neat cellulose, thermo-gel, and salt-gel beads were taken and analysed using ImageJ to determine the volume. The beads were then incubated in SGF at 37ºC for two hours with an 80-rpm agitation. At the completion of two hours, the beads were removed, and images were taken to determine the volume of the beads using ImageJ. After imaging, the beads were placed in SIF and incubated for six hours at 37ºC with an 80-rpm agitation. At the conclusion of six hours, the beads were removed, and images were taken to determine the volume. Using the initial and final volumes of the beads measured using Image J, the volume-swelling ratio was determined using Equation 13

where

is the volume-swelling ratio,

is the initial volume before subjecting the beads to the simulated gastrointestinal tract, and

is the final volume after incubation [

49,

50].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.M.A.; Methodology, M.T.G., S.A.S.E., A.P.Y., and S.L.M.A.; Software, M.T.G., S.A.S.E., and L.T.M.; Validation, M.T.G., S.A.S.E., A.P.Y., L.T.M., and S.L.M.A.; Formal Analysis, M.T.G. and S.A.S.E.; Investigation, M.T.G., S.A.S.E., and S.L.M.A.; Writing – Original Draft, M.T.G., S.A.S.E., A.P.Y., and S.L.M.A.; Writing – Review and Editing, M.T.G. and S.L.M.A.; Supervision, S.L.M.A.; Funding Acquisition, S.L.M.A.

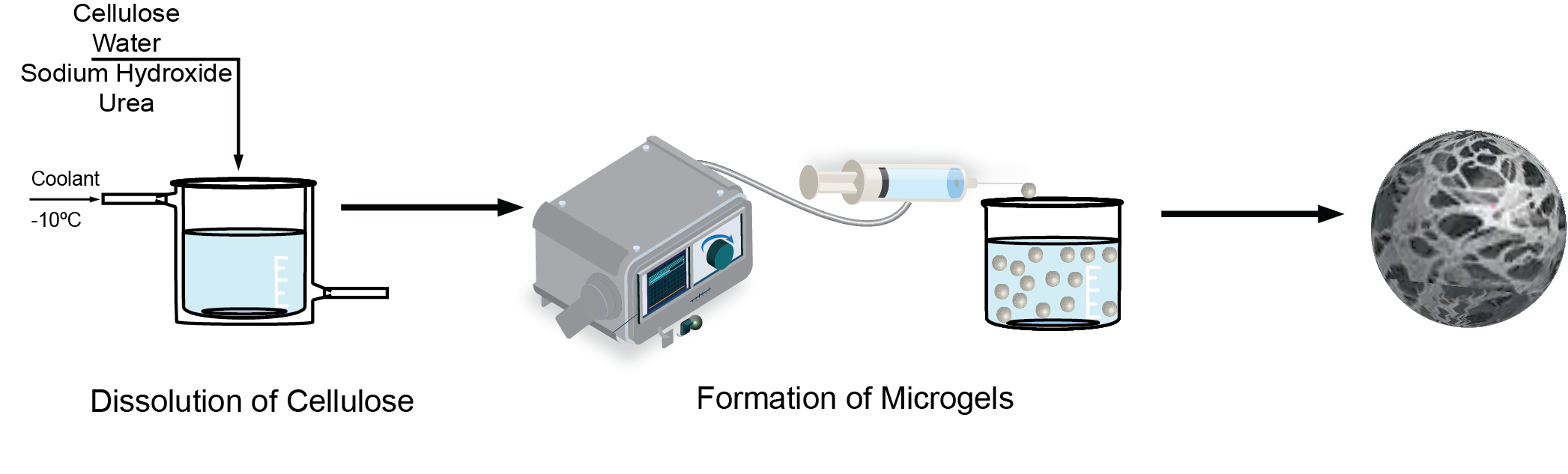

Figure 2.

a) Computational heat maps were used to predict thermal gradients present in cellulose solutions over time as a function of bath temperature. A 25ºC water bath resulted in the lowest thermal gradient as a function of radial distance and time, indicating the least amount of thermal stress. b) Experimental temperature vs. time data was used to validate the model (r = 0.00 m) and determine the time to reach thermal equilibrium for water bath temperatures of 25, 45, and 65ºC. (c-e) Solutions were visually examined for signs of thermal stress (transition from colorless to yellow) and precipitation (transition from transparent to opaque). Signs of thermal stress increased as a function of bath temperature, with the 25ºC water bath (c)) showing the least signs of thermal stress after 30 minutes compared to the 45ºC (d)) and 65ºC (e)) water baths.

Figure 2.

a) Computational heat maps were used to predict thermal gradients present in cellulose solutions over time as a function of bath temperature. A 25ºC water bath resulted in the lowest thermal gradient as a function of radial distance and time, indicating the least amount of thermal stress. b) Experimental temperature vs. time data was used to validate the model (r = 0.00 m) and determine the time to reach thermal equilibrium for water bath temperatures of 25, 45, and 65ºC. (c-e) Solutions were visually examined for signs of thermal stress (transition from colorless to yellow) and precipitation (transition from transparent to opaque). Signs of thermal stress increased as a function of bath temperature, with the 25ºC water bath (c)) showing the least signs of thermal stress after 30 minutes compared to the 45ºC (d)) and 65ºC (e)) water baths.

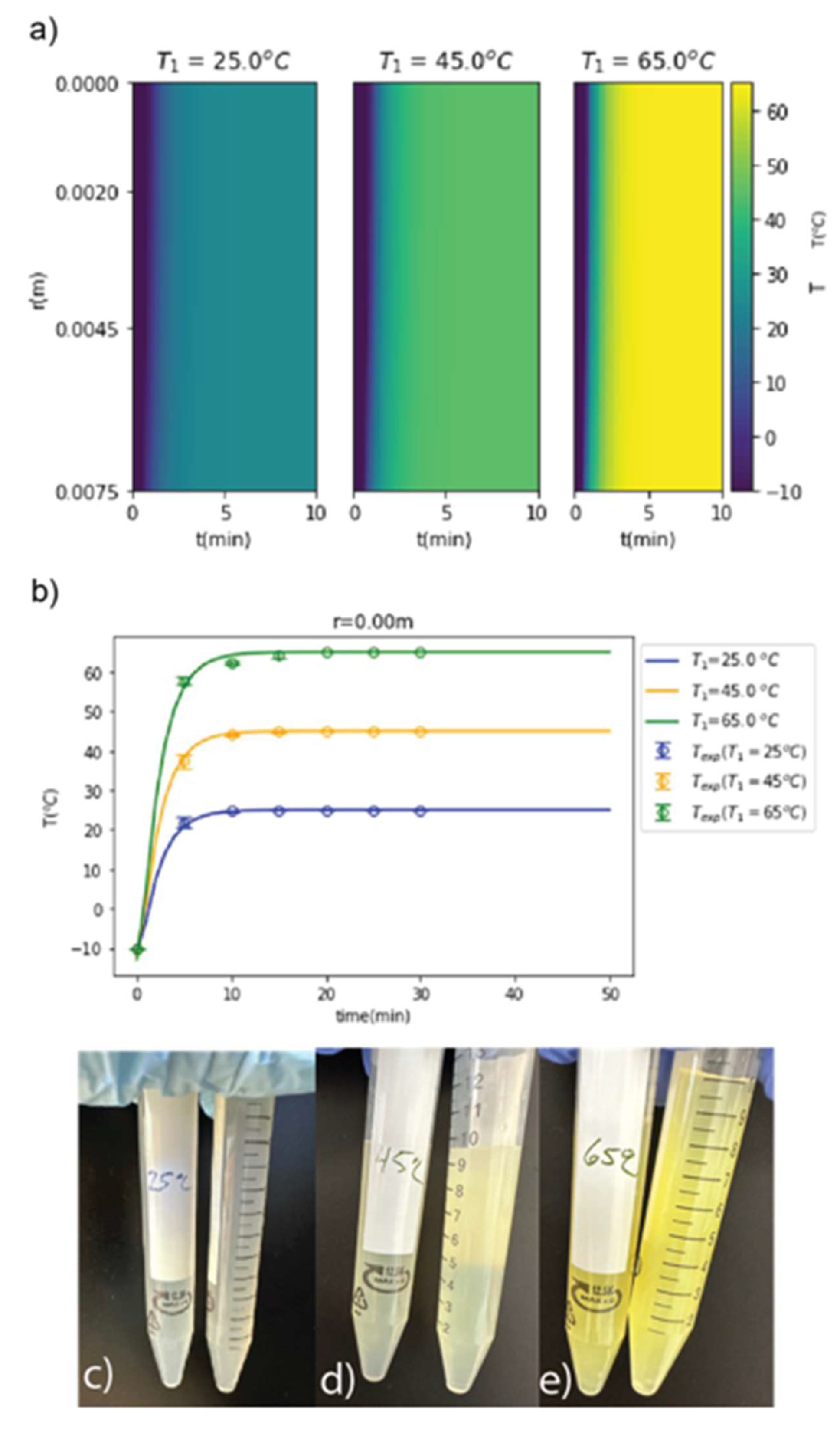

Figure 3.

As the salt concentration was increased for the CNF solution, the zeta potential decreased while the viscosity increased. In contrast, the NaOH/Urea solution and the CNF suspension in DI Water displayed negligible changes in zeta potential and viscosity as salt concentration was increased. The CNF suspension in NaOH/Urea solution showed slight decreases in zeta potential – indicating that the driving force for coagulation is related to the interactions between the CNF and the NaOH/Urea solution.

Figure 3.

As the salt concentration was increased for the CNF solution, the zeta potential decreased while the viscosity increased. In contrast, the NaOH/Urea solution and the CNF suspension in DI Water displayed negligible changes in zeta potential and viscosity as salt concentration was increased. The CNF suspension in NaOH/Urea solution showed slight decreases in zeta potential – indicating that the driving force for coagulation is related to the interactions between the CNF and the NaOH/Urea solution.

Figure 4.

(a) Neat cellulose, thermo-gel, and salt-gel beads were examined for tail formation using ImageJ. Salt-gel beads had the lowest degree of tail formation compared to neat cellulose and thermo-gel beads. (b-c) The circularity of the thermo-gel beads slightly increased compared to the neat cellulose beads and had lower variability. The diameter of the thermo-gel beads was lower than the neat cellulose beads. (d-e) Salt-gel beads with a salt concentration of 0.5 wt% did not improve bead geometry, while 1 and 2 wt% salt increased circularity and decreased variability compared to both neat cellulose and thermo-gel beads. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, and no * = not significant.

Figure 4.

(a) Neat cellulose, thermo-gel, and salt-gel beads were examined for tail formation using ImageJ. Salt-gel beads had the lowest degree of tail formation compared to neat cellulose and thermo-gel beads. (b-c) The circularity of the thermo-gel beads slightly increased compared to the neat cellulose beads and had lower variability. The diameter of the thermo-gel beads was lower than the neat cellulose beads. (d-e) Salt-gel beads with a salt concentration of 0.5 wt% did not improve bead geometry, while 1 and 2 wt% salt increased circularity and decreased variability compared to both neat cellulose and thermo-gel beads. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, and no * = not significant.

Figure 5.

(a-c) Cross-sectional SEM images were taken of (a) neat (no pre-gel), (b) thermo-gel, and (c) salt-gel beads. SEM revealed that neat and thermo-gel beads had a tighter cellulose network that limited the diffusion of salt, while salt-gel beads had a larger network that allowed salt to diffuse and improve uniformity throughout the network. All scale bars = 80 µm corresponding to 2000X magnification. (d-f) 3-D nano-CT scans were taken of (d) neat (no pre-gel) cellulose, (e) thermo-gel, and (f) salt-gel beads fabricated in a 2M HCl coagulation bath. Nano-CT revealed that adding salt into the solution generated a uniform network structure throughout the bead. Access to 360 rotations for each bead are available in the supplementary information.

Figure 5.

(a-c) Cross-sectional SEM images were taken of (a) neat (no pre-gel), (b) thermo-gel, and (c) salt-gel beads. SEM revealed that neat and thermo-gel beads had a tighter cellulose network that limited the diffusion of salt, while salt-gel beads had a larger network that allowed salt to diffuse and improve uniformity throughout the network. All scale bars = 80 µm corresponding to 2000X magnification. (d-f) 3-D nano-CT scans were taken of (d) neat (no pre-gel) cellulose, (e) thermo-gel, and (f) salt-gel beads fabricated in a 2M HCl coagulation bath. Nano-CT revealed that adding salt into the solution generated a uniform network structure throughout the bead. Access to 360 rotations for each bead are available in the supplementary information.

Figure 6.

Increasing the concentration of salt into solution prior to coagulation effectively screens the salt produced from the neutralization reaction and provides elasticity to the cellulose network. Neat and thermo-gel solutions have salt concentrations that causes competition between cellulose chains during aggregation due to no salt screening effects. In contrast, introducing salt into solution helps avoid this problem and leads to more uniform beads with less structural variability.

Figure 6.

Increasing the concentration of salt into solution prior to coagulation effectively screens the salt produced from the neutralization reaction and provides elasticity to the cellulose network. Neat and thermo-gel solutions have salt concentrations that causes competition between cellulose chains during aggregation due to no salt screening effects. In contrast, introducing salt into solution helps avoid this problem and leads to more uniform beads with less structural variability.

Figure 7.

Nanoindentation was performed on neat cellulose, thermo-gel, and salt-gel beads in a (a) control (water), (b) simulated gastric fluid (SGF), and (c) simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) environment. Overall, salt-gel beads displayed lowest variability and lowest Young’s modulus compared to both thermo-gel and neat cellulose beads. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, and no * = not significant.

Figure 7.

Nanoindentation was performed on neat cellulose, thermo-gel, and salt-gel beads in a (a) control (water), (b) simulated gastric fluid (SGF), and (c) simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) environment. Overall, salt-gel beads displayed lowest variability and lowest Young’s modulus compared to both thermo-gel and neat cellulose beads. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, and no * = not significant.