1. Introduction

This paper examines how Digital Twin (DT) technology can enhance multi-hazard risk assessments by integrating it with Building Information Modelling (BIM), Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and the Internet of Things (IoT). The study presents the TErritorial RIsk Management & Analysis Across Scale (TERIMAAS) framework, using a flood risk case study to illustrate the practical application of these integrated technologies.

1.1. Background and Motivation

In the modern era, the DT [

1,

2] paradigm has disrupted the idea of representing the world through simplified models that describe its behaviour. A DT is a real-time digital replica of a physical entity. The fundamental part can be mirrored in a virtual environment and continuously updated from multiple sources for various purposes [

3]. Rapid advances in telecommunications and information technology in recent years have led humans to want to achieve more accurate and detailed descriptions of the built environment. The goal is to reach the twin copy of the system - a building, a city or a territory in the field of investigation - and interrogate it concerning its real-time state. The most cutting-edge enabling technologies, including Big Data, cloud computing, the IoT, and Artificial Intelligence (AI), now make it possible to collect, store, and handle an ever-increasing amount of data by facilitating cross-domain access. Data has become so relevant in the information society that it is seemingly the only thing that matters. The creation, distribution, use, dispersal, integration, and management of information have become the most significant cultural, economic, and political tasks to achieve competitive advantages [

4]. In line with this understanding, the Dutch architect Maas provocatively published a book at the end of the last century that reflected on the futuristic “Datatown”, a city-based exclusively upon data, a city to be described only by the flow of information [

5]. Data appears to be the most reliable tool for providing an accurate view of social interactions from our daily activities and the environment that staged those interactions [

6]. Now up to fourteen [

7], the characteristics of Big Data were initially defined according to the 3Vs model, Volume, Variety, Velocity, by analyst Doug Laney, based on a 2001 study [

8]. Volume concerns the amount of data collected and stored. Data creation follows an exponential process. According to the global data and business intelligence platform “Statista”, about 328.77 million terabytes, or 0.33 zettabytes, of data are created daily [

9]. Moreover, 90 per cent of the world’s data has been created in the past two years alone [

10]. Variety concerns the diversity of formats, sources, and structures. Velocity allows it to be readily available for real-time management and use.

Within this framework, using interoperable platforms is crucial to converting data into usable information to ensure fruitful collaboration among stakeholders and make sense of data through their interpretation. A system aimed at a data-driven approach in the built environment, in a transition process such as the current one, must be able to develop an ecosystem of services [

11] by responding to queries related to the synchronic state of affairs of diachronic scenarios [

12]. This approach is particularly crucial when examining resilience in the age of climate change, as numerous dimensions need careful monitoring. Improving the understanding of disaster risk and strengthening disaster risk governance, as suggested by the Sendai Framework of 2015 [

13], represents another goal to be achieved. According to the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), disasters are indeed reversing global development at unprecedented rates; therefore, urgent actions are needed to build resilience to withstand and respond to shock in every decision we make. With current climate projections, the world could face 560 yearly disasters by 2030 [

14].

As tools nowadays enable a more performant multidisciplinary knowledge of the built heritage, pragmatic experimentation to guide the handling of complexity is essential in structuring and graphical and visual representation of the data. The perspective lies in experimenting with ways to relate heterogeneous, static and dynamic data to each other, interrogate them concerning specific objectives and visualise them through intuitive presentation modes.

One of the most relevant aspects of a multi-hazard assessment is considering the continuous transition in scale, from the general to the particular and vice versa. Data have become increasingly accurate over time, assuming greater complexity and resolution; however, they consider specific areas of investigation.

To predict the impacts of the environment on individual works, as well as the effect of individuals concerning the surroundings, the availability of large-scale spatial and temporal data must cross that of high-resolution detail. The perspective of making effective decision support systems [

15] to predict pre- and post-extreme event impacts requires the interpretation of data derived from spatial knowledge of buildings, territory, and hazards.

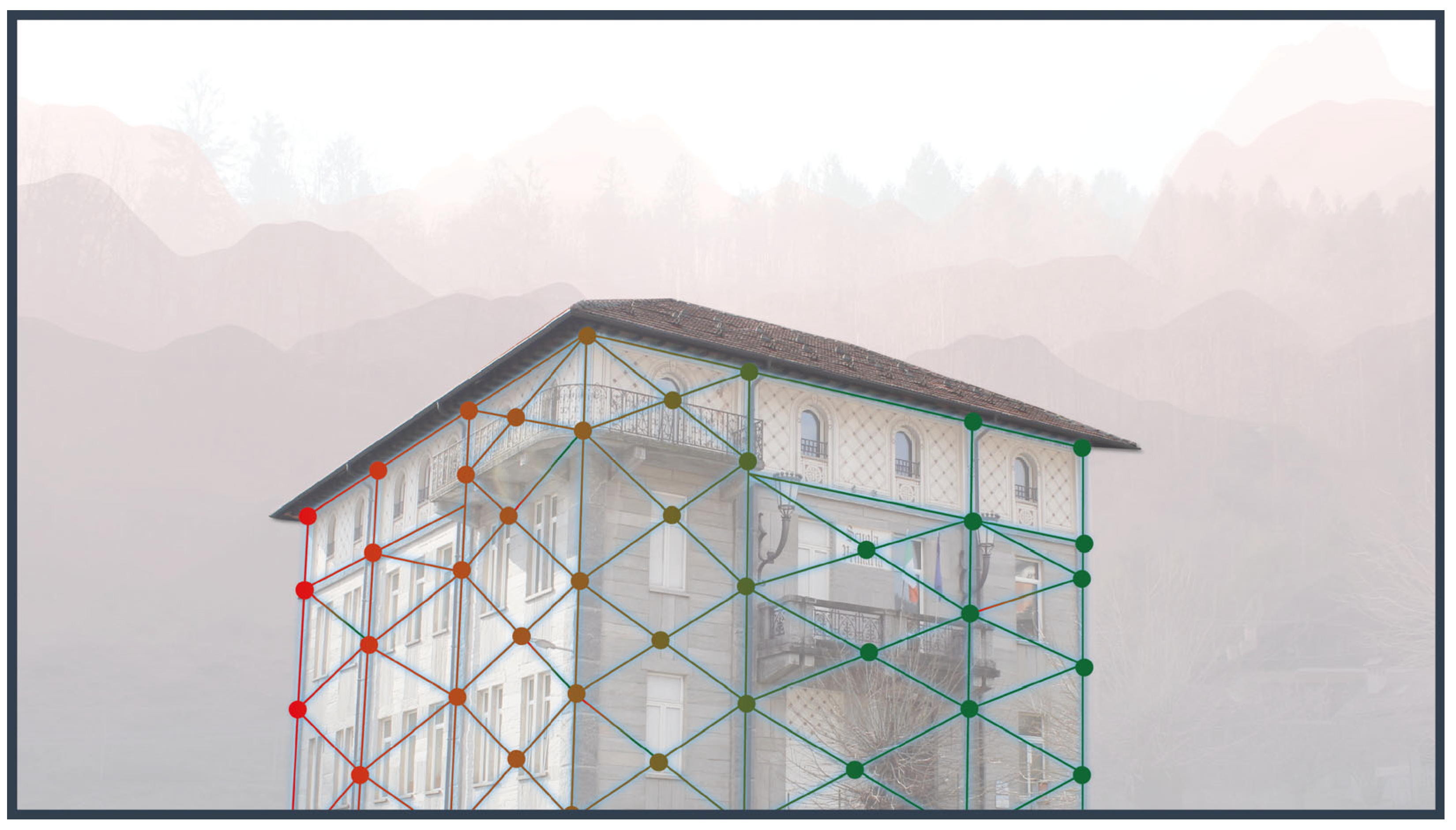

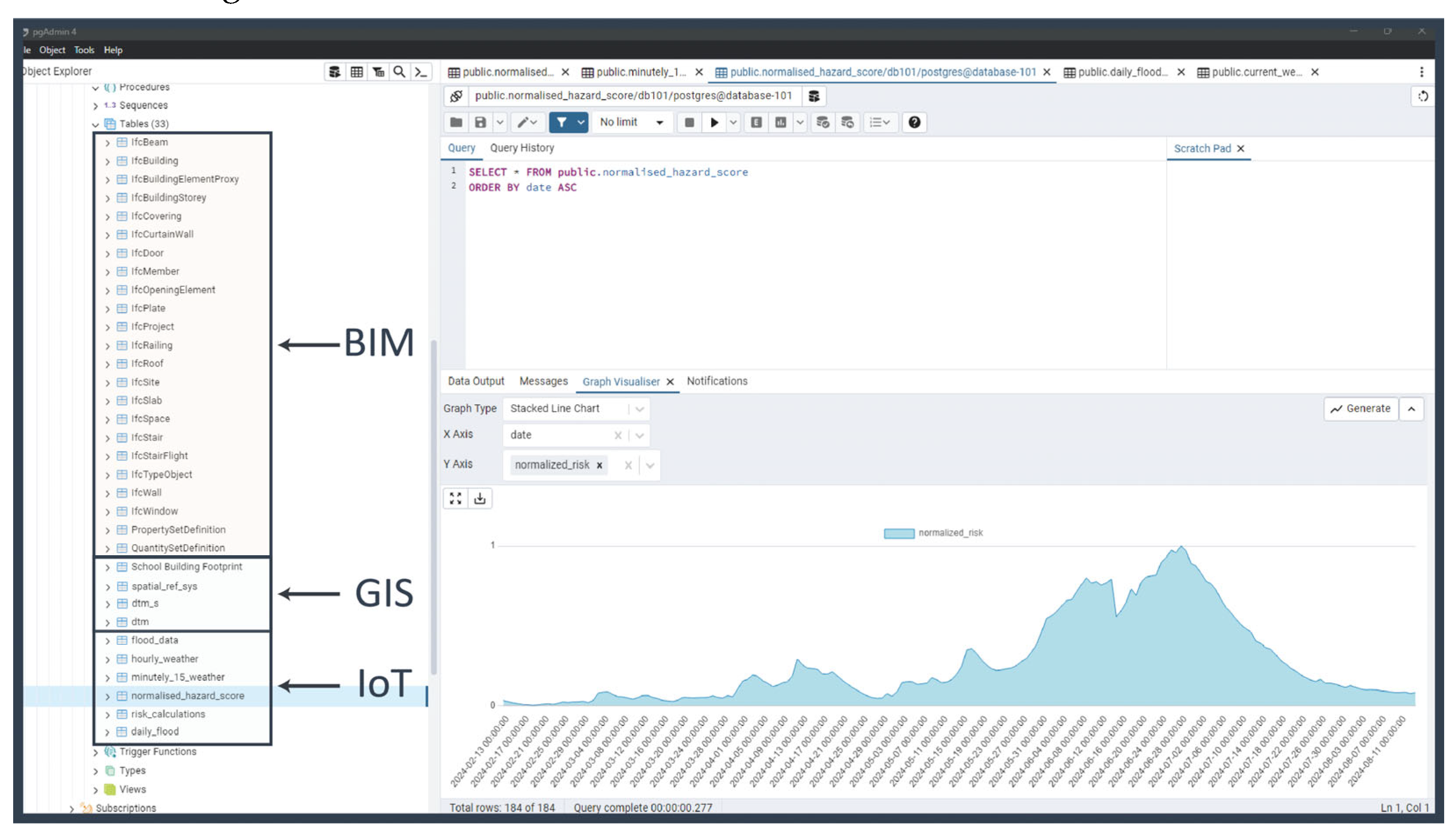

Specifically, BIM is a methodology consisting of a digital representation of a building, focused not only on its graphical 2D and 3D features but, most importantly, the quantitative and qualitative information related to any of its constituent elements. Therefore, it serves as a common source of information about a facility, allowing users to have a reliable basis for decision-making. When integrated into DTs, BIM provides an accurate geometric and semantic model of a built asset. This allows for a more granular analysis of potential impacts and vulnerabilities, enabling a potential element-by-element type of assessment. Furthermore, BIM facilitates the simulation of scenarios and mitigation strategies, while IoT-driven environmental data integration, as depicted in

Figure 1, plays a crucial role in enhancing building resilience.

1.2. Literature Review

BIM and GIS are critical technologies in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry, each providing unique capabilities for spatial data analysis and infrastructure management. BIM offers highly detailed, three-dimensional representations of buildings, integrating comprehensive datasets on architectural, structural, and mechanical systems [

16,

17]. Conversely, GIS excels in spatial data analysis and visualisation, offering a broader macro-level view of natural and built environments [

18].

Integrating BIM and GIS leverages the micro-level detail of BIM with the macro-level spatial analysis capabilities of GIS, significantly enhancing decision-making processes in urban planning, infrastructure management, and disaster risk management [

19,

20]. This fusion enables a holistic risk assessment and mitigation approach, particularly in managing natural hazards and disasters at different levels [

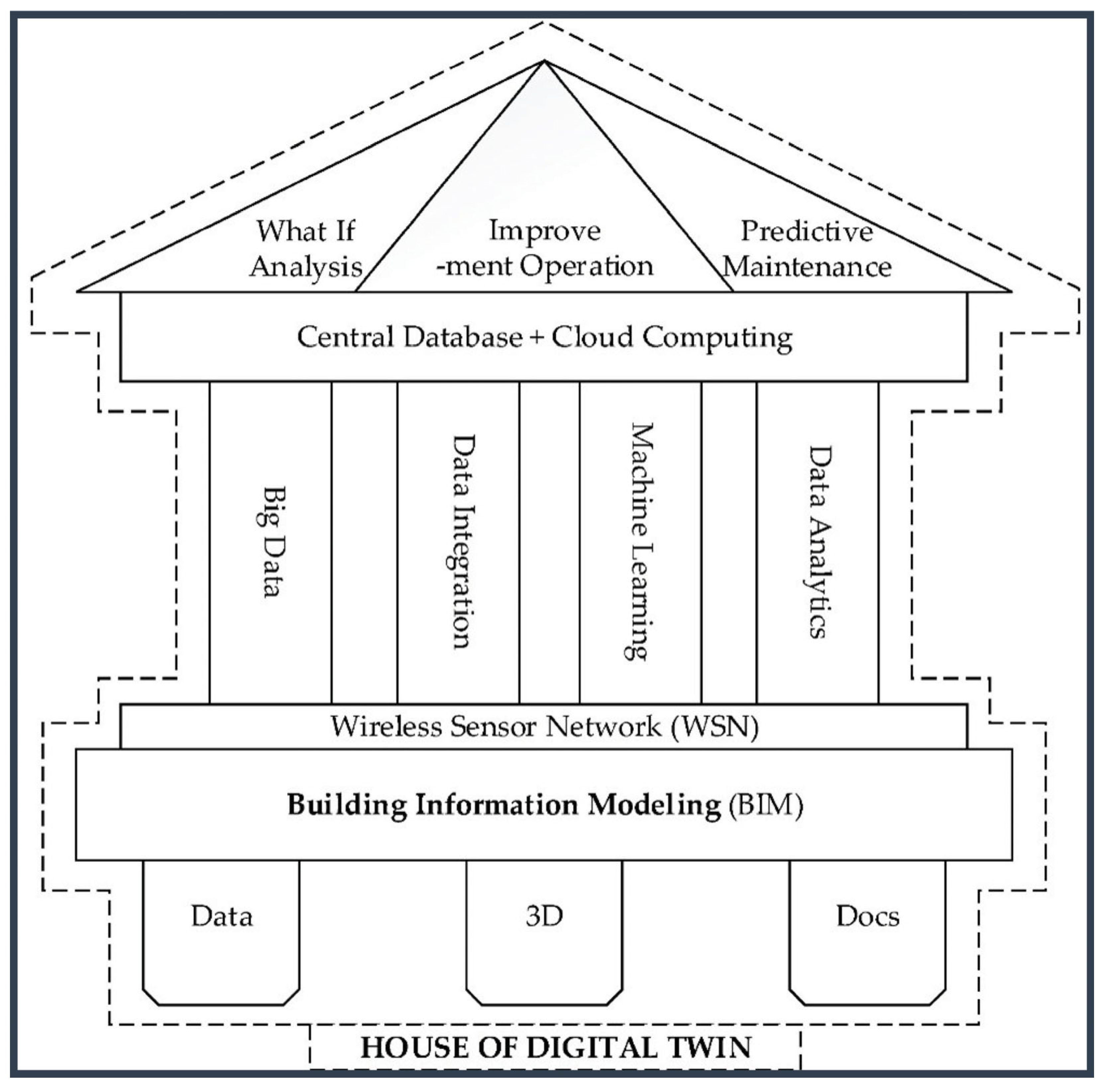

18]. The foundational elements constituting a DT [

21], crucial for this comprehensive integration, can be seen as structured in the 'House of Digital Twin' framework as illustrated in

Figure 2.

GIS is particularly adept at hazard risk assessment and management, including floods, due to its robust spatial data analysis capabilities, which include terrain modelling, hydrological analysis, and infrastructure visualisation [

15,

22]. BIM complements this by providing detailed data on building structures and systems, allowing for precise evaluation of vulnerabilities and the development of targeted mitigation strategies [

23]. When integrated, BIM’s granular building information and GIS’s broad spatial context enhance emergency response efforts, improve situational awareness, and support more informed decision-making [

24]. This integrated approach is crucial for effective disaster management, where timely and accurate data are imperative [

25]. The STORM project exemplifies such integration by offering a comprehensive multi-hazard risk assessment and management tool tailored for cultural heritage sites, addressing both natural hazards and climate change impacts [

25]. Similarly, a recent systematic review highlights that centralised databases and integrated webgis platforms significantly contribute to informed decision-making in disaster risk management by enhancing capabilities in risk data collection, processing, and dissemination of natural disasters [

26].

Despite the advantages of integrating BIM and GIS, traditional systems often rely on static data, posing significant limitations for real-time hazard assessment and responsive disaster management. The IoT addresses this limitation by enabling continuous, real-time data collection and transmission, which provides up-to-date information on environmental conditions and structural integrity [

27]. Integrating IoT with BIM and GIS facilitates dynamic model updates and enhances hazard assessment and response capabilities [

28]. The InSPiRE project demonstrates the efficacy of combining IoT with BIM for predictive maintenance, improving lifecycle management through real-time data acquisition and analysis [

29].

However, integrating BIM, GIS, and IoT is fraught with challenges primarily related to data interoperability, standardisation, and processing techniques. These systems often operate in isolation, leading to significant interoperability issues [

30]. A robust integration framework is required to manage and automate the processing of extensive datasets generated by these systems. Reviews of risk web platforms highlight the necessity for standardised data protocols and interoperable systems to enhance the accessibility and usability of risk information [

31].

Data incompatibility is a significant challenge in BIM-GIS integration. BIM typically utilises local coordinate systems for detailed design, whereas GIS employs global coordinate systems for spatial analysis. This discrepancy necessitates complex data transformation processes, which can lead to data loss and reduced accuracy [

32]. Furthermore, the lack of standardised data formats complicates integration. BIM and GIS use different standards and formats; for example, BIM often employs Industry Foundation Classes (IFC), while GIS uses formats such as shapefiles or GeoJSON. Data conversion between these formats can be resource-intensive and prone to errors [

33].

Effective interoperability remains a significant barrier due to the fragmented nature of software platforms and tools in these domains. Many systems do not communicate seamlessly, leading to isolated data silos and impaired comprehensive analysis [

23].

To address these issues, a centralised framework is essential. This framework should support data interoperability, standardisation, and real-time data integration, incorporating automated data transformation, validation, and updating processes. It should also provide a centralised data repository to streamline data management and improve stakeholder accessibility [

34,

35].

A well-designed, interoperable framework will enhance data sharing, improve decision-making processes, and optimise resource management in disaster risk management. It will also facilitate the development of innovative, resilient cities capable of effectively withstanding and recovering from natural hazards and disasters [

36,

37,

38,

39].

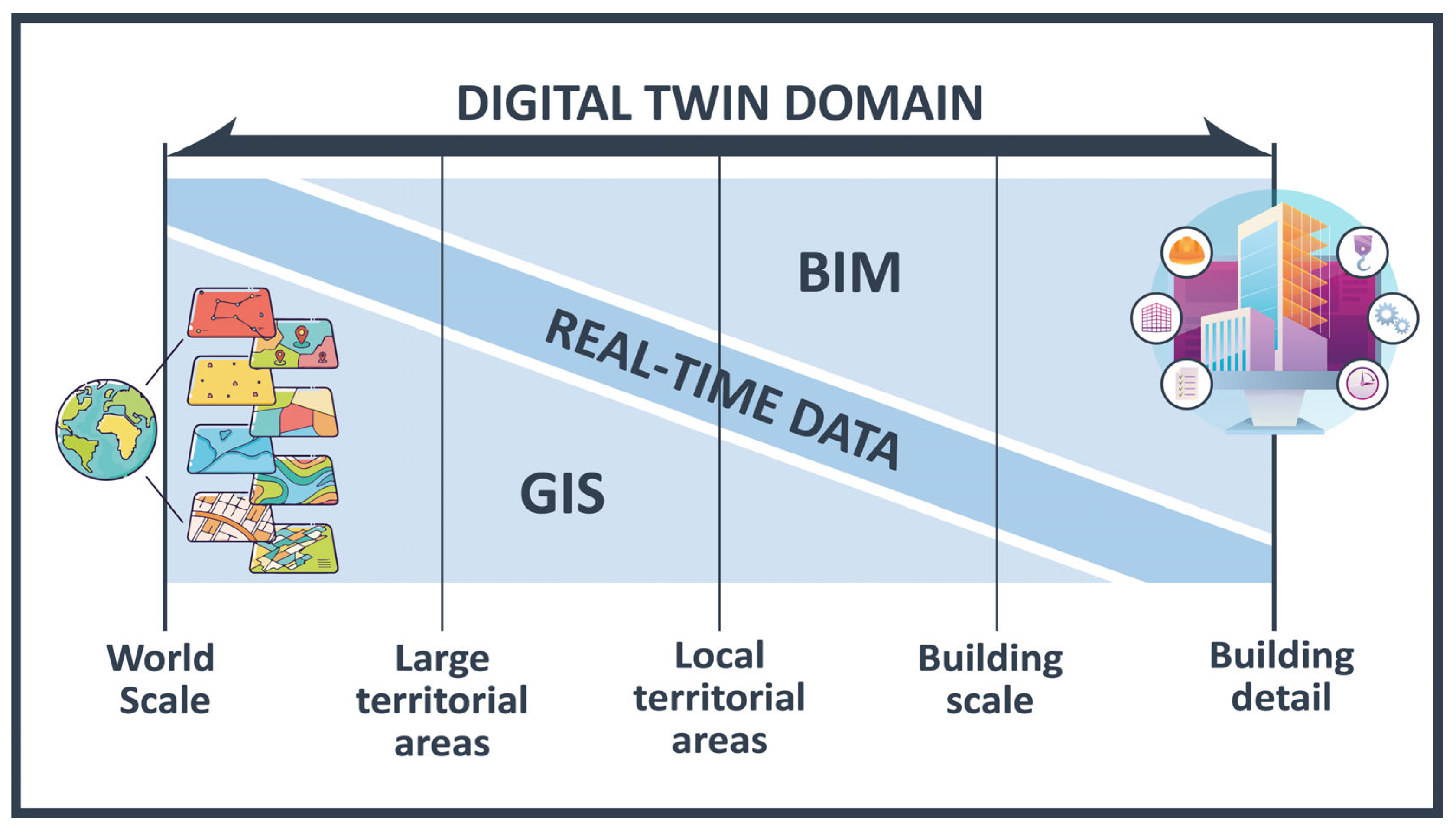

Through the literature analysis, it is clear that this research addresses a critical knowledge gap by adopting a multi-hazard approach that provides a more realistic and comprehensive understanding of socio-economic impacts. The methodology developed in this study is scalable and adaptable to various study areas, thereby enhancing the generalizability and practical application of the findings. This approach is visually represented in the framework shown in

Figure 3, which links building-scale resilience with territorial-scale hazards.

1.3. Significance of the study

This study contributes to the existing literature on bridging a gap between GIS and BIM [

15] for resilience and disaster risk management by providing a novel approach to assess the effects of shock and pressure using a scalable framework. The general objectives are as follows:

to create a PostgreSQL [

40] database integrating disparate data formats;

to define and operationalise risk analysis indicators;

to visualise the results of cross-sectional data queries graphically;

to propose a scalable methodology that can integrate multiple data sources and types for multi-hazard analysis.

Within this scope, the most relevant novelty lies in integrating BIM data within a Postgres database and, consequently, their use to increase the level of detail of the analyses, which can thus move from a spatial to a more local scale.

The integrated approach, rigorously validated through a real-world case study, considering the flood impact assessment on a public building in a critical area of the Piedmont Region in Italy, is a testament to its reliability and effectiveness. This example provides only a cue related to possible queries of the centralised database in multi-risk management, where the different types of risk can be understood as system modules, further reinforcing the robustness of the proposed framework.

The research is organised as follows:

Section 2 describes the methodology and technical framework of TERIMAAS, highlighting software and data management processes;

Section 3 presents the method's application in a case study, focusing on a specific use case;

Section 4 includes the study's results and discussion; and

Section 5 traces the line for future works.

2. Methodology

The volume and variety of information to be achieved and managed in the perspective of obtaining a representative twin model of the territory configure data collection and visualisation activities in a crucial, unprecedented way. The outlined complexity must recognise the need to intelligently converge highly heterogeneous data sources such as type, format, discipline, and granularity. Accessing a comprehensive centralised database is essential for correlating multidisciplinary and cross-scale data and paves the way for new testing and approaches.

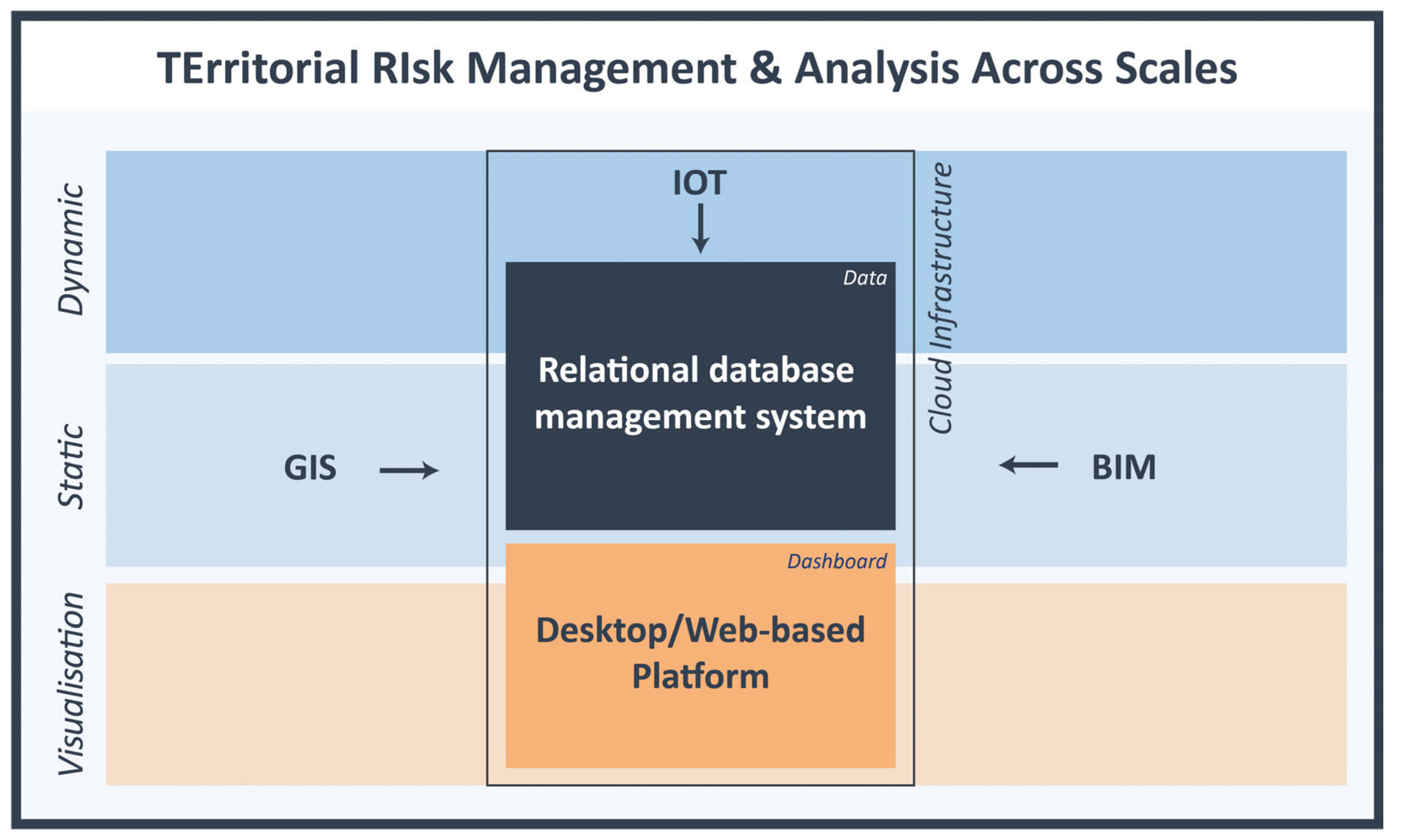

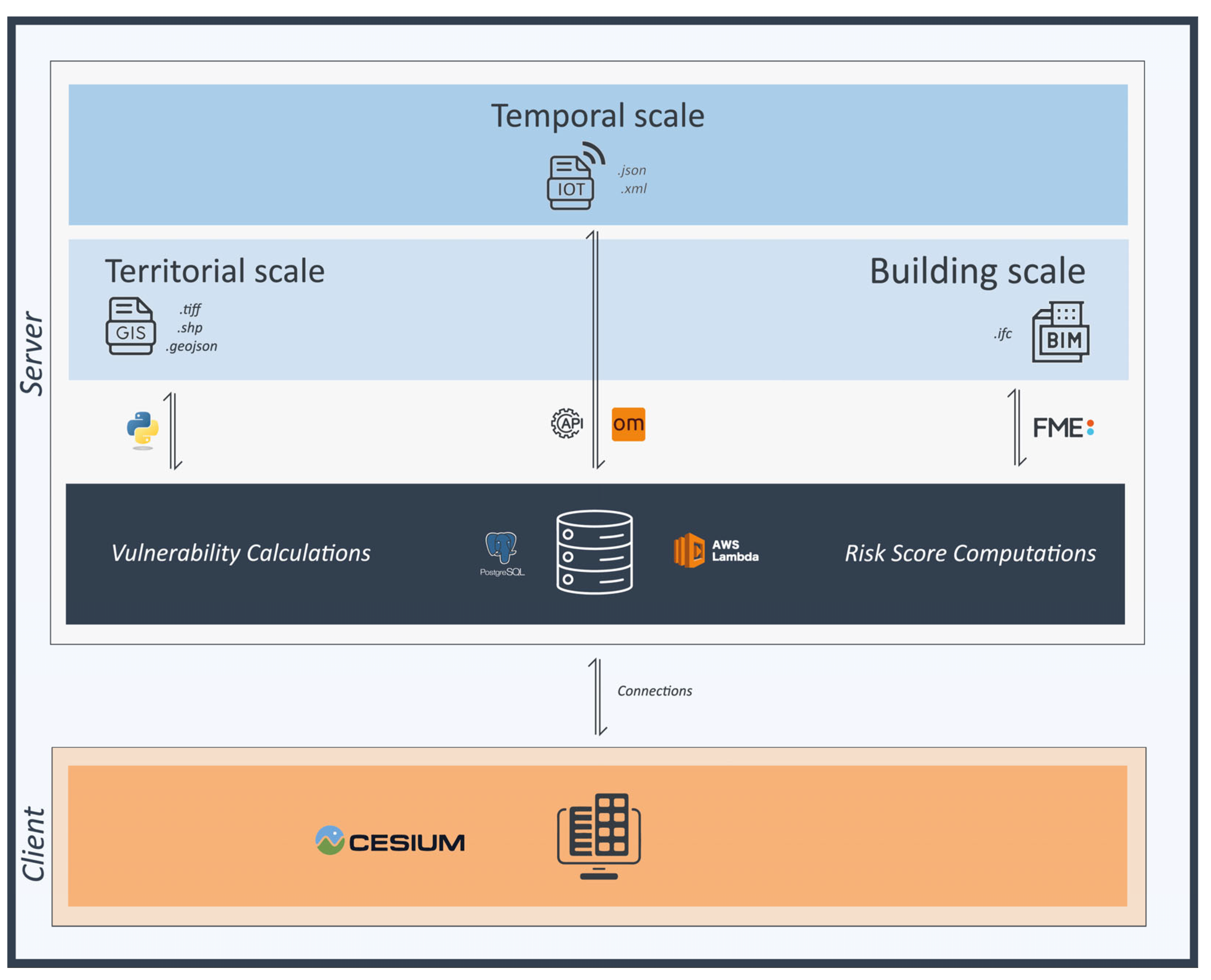

The architecture of TERIMAAS is presented in

Figure 4. The core of the proposed solution is an Infrastructure-as-a-Service, consisting of a collection of virtualised resources for storage, processing and visualisation purposes. The idea is to combine static and dynamic data of interest through a relational database management system (RDBMS). In this way, it is possible to make information datasets generally managed with dedicated environments interact with each other. Specifically, monitoring and analysing territorial resilience requires (i) time-scale information referring to environmental parameters, (ii) geographic spatial knowledge, and (iii) specific information relating to point artefacts and distributed infrastructure. IoT, GIS, and BIM systems constitute the primary databases that implement the central storage unit. Dynamic data updates the database by enabling scenario processing by calculating indicators. Trigger functions automatically convert the received data into information, making it readily available for further analysis. Once the data is processed, it can be exposed through dashboards and specific visualisation platforms.

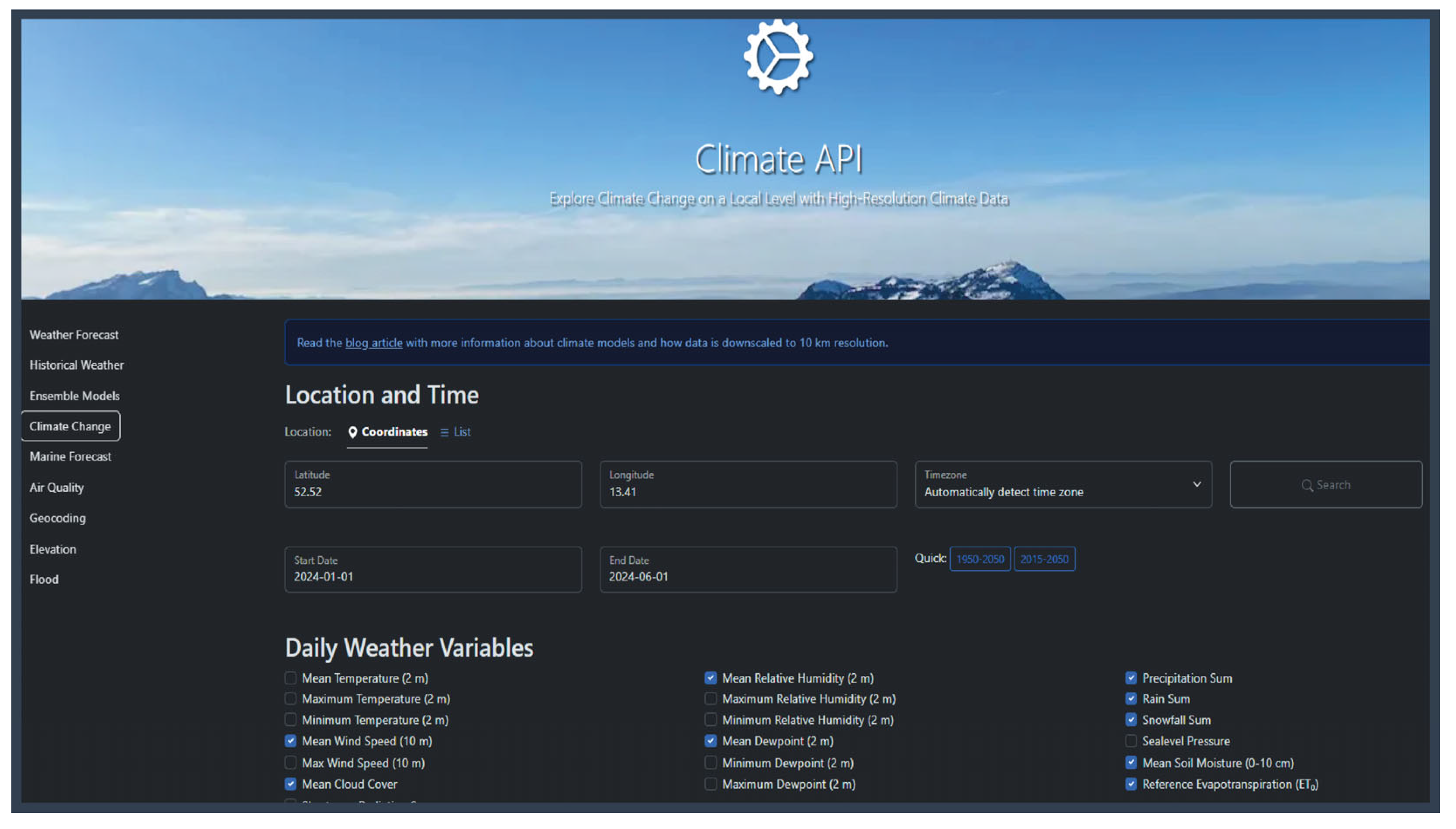

2.1. Dynamic Data Management at the Temporal Scale

Natural hazards, such as earthquakes, floods, or wildfires, necessitate real-time assessment, a capability often limited by the static nature of traditional GIS and BIM datasets collected post-event [

41]. TERIMAAS addresses these challenges in hazard scenarios through a robust and continuous data ingestion pipeline. Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and webhooks serve as gateways, facilitating the constant influx of high-frequency, geotagged data streams from IoT sensors. These sensors provide real-time data, which can originate from diverse sources such as national meteorological agencies, regional hazard monitoring networks, or open-source weather data providers.

The raw data undergoes a multi-stage validation process, which includes outlier detection, spatial interpolation, and plausibility checks against historical data and real-time observations. Subsequently, validated data is integrated into a spatially enabled PostgreSQL/PostGIS geodatabase.

The ingestion of fresh data triggers a cascade of automated processes using the Trigger functions tailored to the specific hazard. Real-time sensor data is spatially interpolated and integrated with external data sources to generate high-resolution hazard maps for hazard events. These estimates are fed into distributed physical models running on scalable cloud infrastructure to simulate the hazard's evolution dynamically. These models incorporate factors relevant to the specific hazard, such as terrain, weather patterns, and infrastructure vulnerability. The resulting hazard maps are then used to assess risk at various scales, from individual buildings to entire regions. A rule-based alert system can disseminate targeted warnings to relevant stakeholders through multiple channels, enabling timely evacuations or other mitigation actions if pre-defined risk thresholds are exceeded. This IoT-driven methodology empowers TERIMAAS to furnish a continuously updated and multi-layered view of the unfolding hazard situation, which is vital for making informed decisions at various spatial scales, from individual properties to the entire territorial landscape.

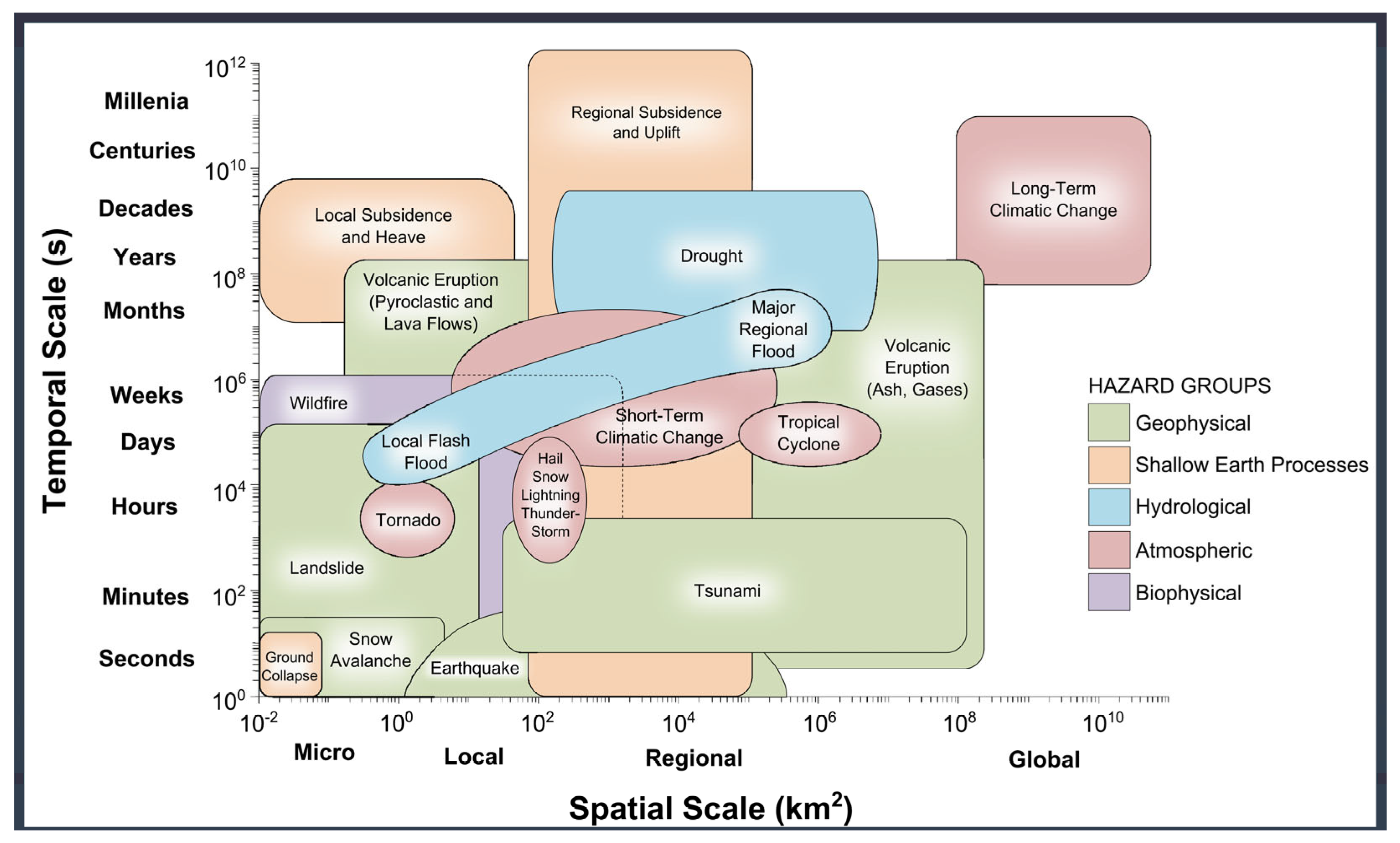

It is essential to observe that when moving from single-hazard to multi-hazard analysis, the temporal and spatial scale of the risk may drastically change.

Figure 5 from Gill et al. 2014 shows the spatial and temporal scales over the 16 natural hazards on logarithmic axes. Here, the spatial scale refers to the area the hazard impacts, and the temporal scale refers to the timescale on which the single hazard acts upon the natural environment [

42].

2.2. Geospatial Data Management at the Territorial Scale

GIS are integral to the TERIMAAS framework, providing the tools necessary for comprehensive multi-hazard risk assessments. As GIS data advances in resolution and density, the capability to capture and analyse spatial information has significantly improved. This enhanced data quality allows for more precise and detailed evaluations of natural hazards and their impacts on natural and built environments.

The TERIMAAS framework leverages vector and raster data to conduct thorough hazard analyses. Vector data, which includes discrete features such as roads, buildings, and land parcels, complements raster data that represents continuous variables like elevation and temperature. These datasets' high-resolution and high-density nature supports detailed local-scale analyses, which are crucial for understanding vulnerabilities at the level of individual structures and natural features. For instance, flood risk assessments may utilise detailed hydrological models and terrain attributes derived from raster data. At the same time, earthquake studies might focus on vector-based seismic fault lines and building inventories. Integrating these diverse datasets—high-resolution Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), land use and land cover classifications, infrastructure networks, and historical hazard footprints—ensures a comprehensive approach to risk assessment. The combination of proprietary and open-source data sources, including satellite imagery, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), and handheld devices, further enhances the richness and applicability of the geospatial data.

The TERIMAAS framework employs cloud-based GIS solutions from Amazon Web Services (AWS) to manage substantial volumes of high-resolution data. AWS provides scalable infrastructure for handling extensive datasets and facilitating advanced web visualisation for hazard management. Essential services include Amazon S3 (Simple Storage Service) for scalable object storage, and Cloud Optimized GeoTIFFs (COGs) for efficient data access and processing. AWS EC2 (Elastic Compute Cloud) offers the computational power required for complex spatial analyses, while AWS Lambda enables serverless computing to automate and streamline data processing workflows. These cloud-based solutions address the challenges associated with large, high-resolution datasets, improving data management efficiency and real-time visualisation capabilities.

In addition to cloud infrastructure, GeoPython libraries [

43] are pivotal to the analytical processes within TERIMAAS. Libraries such as GeoPandas, Rasterio, GDAL (Geospatial Data Abstraction Library), and Shapely are utilised for various tasks. GeoPandas supports high-performance manipulation of geospatial data frames, Rasterio specialises in raster data operations, GDAL facilitates format conversion, and Shapely enables advanced geometric operations and spatial queries. Pyproj aids in coordinate transformations, and Fiona manages spatial data files. Tools like HydroSHEDS and HEC-RAS are integrated for hydrological and flood analysis to model and analyse water flow and floodplain dynamics. The automation of these processes is achieved through AWS Lambda, which ensures accurate and timely geospatial analyses by executing Python scripts and workflows with minimal manual intervention.

Central to the data management within the TERIMAAS framework is PostgreSQL, an open-source relational database system enhanced with the PostGIS extension. PostgreSQL is recognised for its robustness, reliability, and extensibility, which makes it suitable for managing complex geospatial data. When paired with PostGIS, PostgreSQL gains advanced spatial data handling capabilities, including storing, querying, and manipulating geospatial information.

PostGIS adds support for spatial data types such as geometry and geography, allowing precise representation of spatial features like points, lines, and polygons. It also introduces sophisticated indexing methods, such as Generalized Search Tree (GiST) and R-tree, which enhance the performance of spatial queries and manage large, complex datasets efficiently.

Data quality and consistency within TERIMAAS are maintained through standardisation and normalisation. Standardisation ensures uniform data formats, coordinate systems, and measurement units, facilitating the integration of diverse data sources and accurate analysis. Normalisation adjusts data to a standard scale or range, addressing discrepancies and ensuring consistency across datasets.

2.3. Data Management at the Building Scale

Regarding the domain relating to BIM [

44], the methodological framework illustrated here uses three-dimensional digital models in which each modelled building component corresponds to a series of parameters and information associated with it and is usable for specific processing. Specifically, to encourage interoperability between the various systems used, it was decided to use the Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) format, an open exchange format through which both the data and the geometries of a model can also be read outside of any BIM authoring software, almost all proprietary, used to create the model itself [

45].

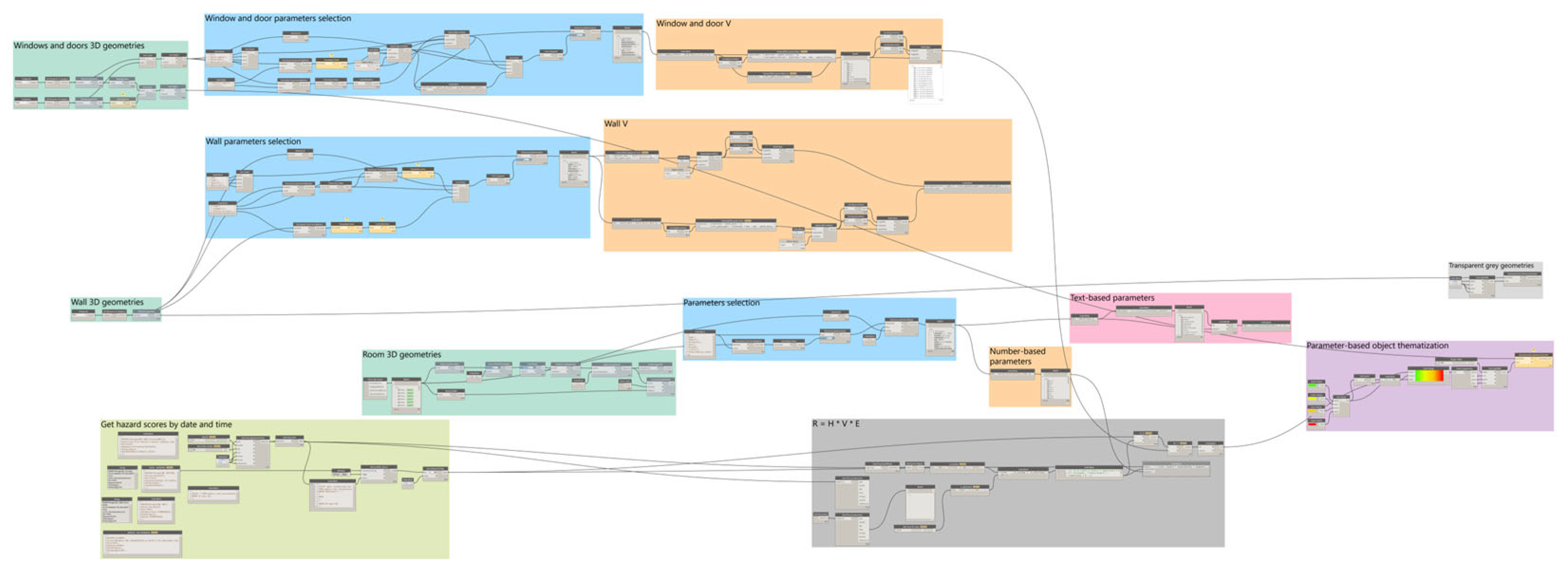

The methodological approach proposed within the TERIMAAS system uses a series of connections, some made in real-time by the tools and software capable of managing the BIM methodology available on the market. Among these, an essential component of an integrated system such as the one proposed is undoubtedly made possible by tools based on Visual Programming Language (VPL) [

46], i.e. systems thanks to which a user, even if not an expert in any specific programming languages, can prototype any functionality from scratch, not already present among the basic ones of the software used, and completely customised based on the needs of the project or application to be created. Furthermore, since these are tools that, in most cases, are integrated, in the form of plugins, within the software used in the AEC industry, the interoperability of data relating to these domains is already optimal. In the case of the system proposed here, there were two tools based on VPL that it was suggested to integrate within the developed methodology, both currently part of proprietary software (while maintaining the aim of also exploring further similar solutions coming from the ecosystem of open-source tools): Feature Manipulation Engine (FME) and Dynamo (the latter an integral part of the Autodesk Revit software). There are many similarities in the use of the two tools for integration with the proposed methodology, certainly including the numerous possibilities for exchanging data, both incoming and outgoing, between the model and the database, as well as between these and any module of additional calculation that is intended to be part of the system’s structure.

Specifically, the Dynamo plugin [

47] has been tested and prepared for bidirectional data exchange with the database: in the model-to-database direction, all data and alphanumeric parameters relating to each component of the model can be transferred within the database, in dedicated tables, with writing and/or updating operations, thanks to the fact that among the functions available in the plugin above there are some specific ones for making connections to databases and sending any command to them, effectively allowing the execution of any CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operation. Furthermore, again using certain features made available by Dynamo, it is also possible to make web connections, for example, to external servers using specific HTTP endpoints, to send data relating to the model to said servers, or receive from them, for example, real-time information from sensors placed on site. Both mentioned functions have been successfully used and tested within the TERIMAAS system methodology. In addition, in the database-to-model direction, the connections made possible by Dynamo have also allowed us to experiment with the reception of updated data coming from the PostgreSQL database, following processes triggered by lambda functions every time the database itself receives updated data from IoT sources. The result and related visualisation are shown in the following sections. Ultimately, once again, taking advantage of the functionality made available by Dynamo to execute SQL (Structured Query Language) commands against relational databases, it is possible to obtain updated data processed by the server and receive them directly within the Dynamo script. Similarly, if necessary, it is also possible to directly execute web requests to external services and obtain input data from sensors or public databases. Once the data, as mentioned earlier, have been received within the VPL script, it is possible to process it further, for example, as was done in the use case presented later, by compiling (or updating) appropriate parameters associated with the spaces of a building, as well as each component of the BIM model created.

Similarly, to Dynamo, the FME tool [

48] was also tested for the purpose of integration into the proposed methodology. In this case, the specific objective was integrating the alphanumeric data and geometric information within the database. This approach was motivated by the fact that FME provides the possibility of exporting a BIM model (in this case, in IFC format) into numerous other spatial formats and environments thanks to its multiple available converters. Currently, the results of this process are still very experimental, and further tests are being carried out due to some emerging critical issues relating to the compatibility of the geometric encoding adopted by the BIM model, the one allowed within the PostgreSQL database, and the necessary further conversions needed in case of geometry export from the database toward other 3D viewers. However, other intermediate solutions, which can potentially be integrated into the methodology, are currently being tested [

49].

With all this considered, as shown in

Figure 6, the TERIMAAS framework comprises a series of domain-specific functionalities that make it possible to have GIS (territorial scale), BIM (building scale) and IoT (dynamic) data converged into a single environment. This allows the system to perform specific risk calculations that consider data coming from these different domains and store the raw data and the processed results in a shared integrated database. Finally, this can be visualised through dedicated viewers, potentially using locally installed software and browser-based web viewers.

3. Use Case Implementation

The methodology presented above is tested through an illustrative use case to clarify the practical application considering a specific environmental risk. This approach can also reflect the modular nature of the TERIMAAS system, outlining its potential in multi-hazard management.

The prototype phase of our study focuses on flood risk by assessing the vulnerability of an actual public building. By cross-referencing the data merged in the centralised Postgres database prototype, the characteristics of the hazard can be related to the area and, specifically, to the characteristics of the building and its activities. Integration is aimed at correlating a relevant precipitation event's effect on the built environment.

From the dynamic rainfall dataset, the precipitation height has been derived and related to the construction BIM data, allowing the identification of all model elements affected by the phenomenon to assess potential damage. The focus is not only on the envelope and structural building components but also on the interior environments. About potential flooding, it will, therefore, be possible to identify in detail the functions and assets affected, for example, sensitive rooms such as archives and libraries or IT equipment such as servers often located in basements.

3.1. Case Study

Among the many possible areas of interest for this kind of analysis, the Val d’Ossola territory, in the northwest of Italy, was chosen for its susceptibility to different types of natural hazards. In fact, this area, including within the administrative territory of the Piemonte Region, is among the ones characterised by relatively high seismic activity, at least compared to the rest of the Region [

50,

51]. Moreover, in this area, surrounded by many mountains and rivers, the probability of flood events is also exceptionally high [

52,

53]. Finally, another important criterion for choosing the case study area was the relative proximity to the authors, which could have allowed the possibility of performing visits and surveys at any needed time.

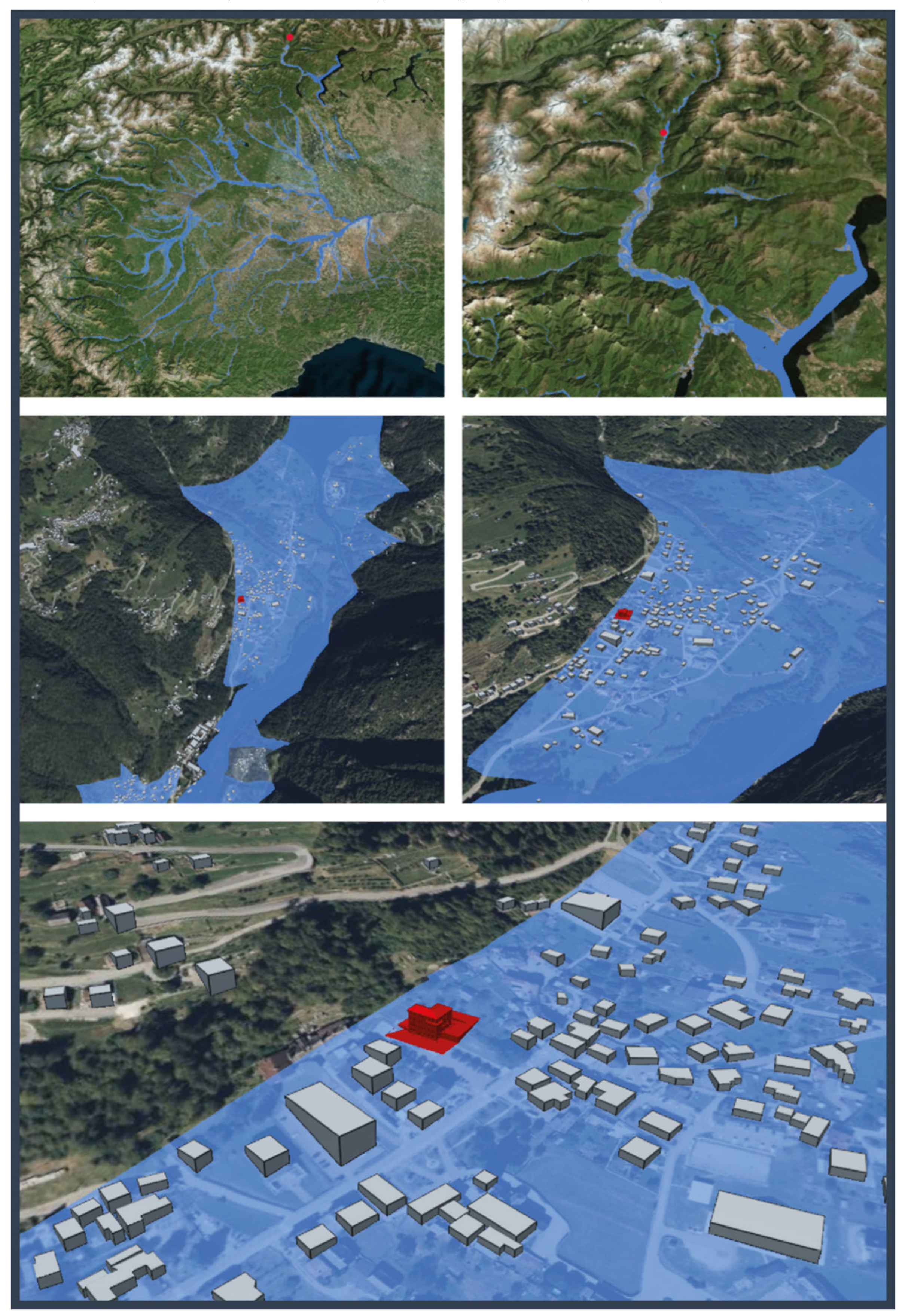

Based on the aforementioned reasons, a school building located in Val d’Ossola was selected as a typological case study due to its sensitivity and strategic importance in flood-prone areas (

Figure 7). School buildings are a considerably sensitive type of asset, given that, from the perspective of safeguarding human lives, users are primarily children, and therefore, the impact of a disaster event is likely to be very high. Moreover, significant public buildings like schools, hospitals, sports halls, and police stations are usually considered “strategic” buildings, meaning that these are types of structures that need to remain operational even in case of disaster events because they might be used, among other things, to host injured and displaced people temporarily.

Specifically, the chosen building was the Primary School of Crodo (VB), one of the schools located in its municipality. This building, dating back to the first decades of the 20th century, comprises four levels, the lowest of which hosts a post office, a public music room, and a series of unused empty spaces in the back. The remaining floors above host all the main spaces of the school, such as classrooms, labs, offices, and restrooms. In particular, the school spaces include five classrooms, two laboratories, an office, and a storage space and restrooms for each floor. There is also a minor construction on the side of the building, hosting the central heating unit and a small terrace at the back of the last floor.

3.2. Data Collection

A research activity was carried out once the case study building was chosen. This activity consisted of documental research in a series of historical and municipal archives on the territory to try to retrieve any historical document that could help in understanding the construction phases of said building. Moreover, an on-site visit was conducted to understand the school's current state and surroundings and perform any needed measurements.

Extensive GIS and IoT data were integrated to enhance the flood risk assessment. The GIS data includes DEMs, Vegetation Soil Curve Number Raster, Land Use/Land Cover classifications, Infrastructure Networks, Historical Flood Footprints, and Flood Maps. These datasets are primarily sourced from national and regional government agencies and are updated regularly to ensure accuracy and relevance.

The IoT data from the OpenMeteo API includes real-time precipitation and meteorological data (temperature, humidity, wind). This real-time data is crucial for predicting and monitoring flood events. By integrating these datasets, a comprehensive and dynamic flood risk assessment can be achieved, providing detailed insights into both the environmental and structural vulnerabilities of the case study building, as shown in

Figure 8.

After completing these activities, it was possible to create a BIM model of the school building to carry out the first data exchange experiments with the proposed system. Given the scarcity and poorness of the retrieved information about the structural and material aspects of the current building, the BIM model consists of a relatively high Level of Development (LOD) [

54] for the architectural discipline. In contrast, the structural and systems disciplines have a lower LOD because of the lack of data.

Table 1 below outlines the various datasets used, their purposes, formats, sources, frequency of updates, and accessibility, offering a comprehensive view of the data integration necessary for this flood analysis. This GIS and IoT data integration ensures a robust flood risk assessment and management framework, facilitating effective decision-making and planning.

3.3. Data Processing

For a flood event, real-time sensor data is spatially interpolated and integrated with external global open-source data sources [

62]. This data includes historical and future predictions of hourly precipitation, rain, soil moisture, humidity, and weather prediction models. The historical data provides a baseline for analysis, while the future predictions help anticipate flood conditions. This integration generates high-resolution rainfall and runoff estimates. These estimates are then input into distributed hydrologic models, such as HEC-HMS, which operate on a scalable cloud infrastructure like AWS Lambda. These models simulate the evolving catchment response. Subsequently, the hydrologic output is used as input for fully 2D hydrodynamic models that dynamically simulate the propagation of floodwaters across the terrain, incorporating factors like infiltration, surface roughness, and channel conveyance.

On the other hand, GIS data, including terrain elevation, land use, watershed basin delineation, and Soil Conservation Service (SCS) curve number (SN) values, is also integrated for comprehensive flood analysis. This data helps refine the flood risk assessment, considering local characteristics such as soil type and land use patterns. The hazard risk score is normalised based on the results of the analysis. Consequently, building-level flood risk is then recalculated based on the updated flood maps, considering not only inundation depth but also flow velocity and other hazard metrics. The results of the flood analysis, including updated flood maps and metrics, are stored in a PostgreSQL database, as shown in

Figure 9.

3.4. Findings

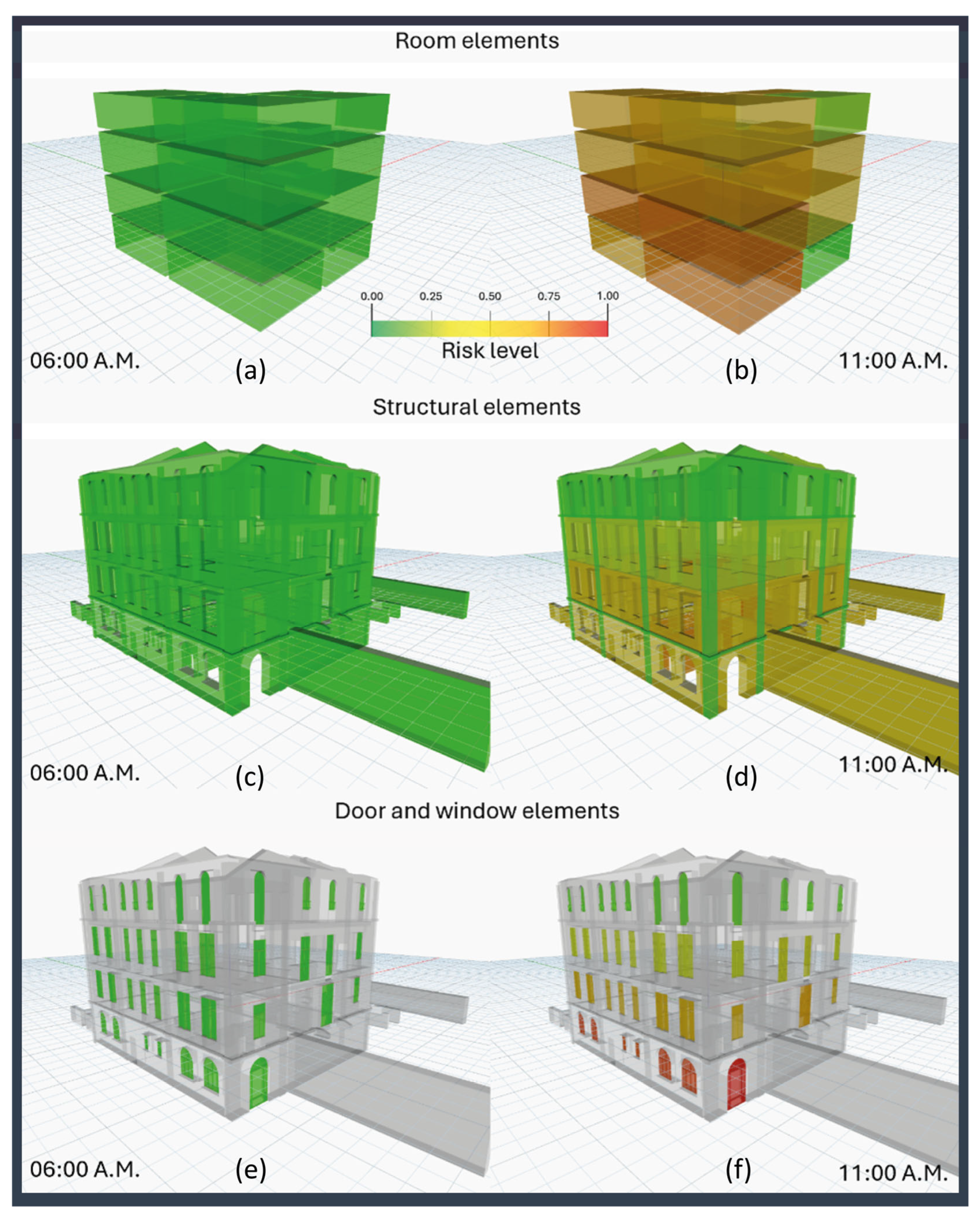

The database mentioned above is a central repository accessible to the BIM system, enabling dynamic flood risk recalculations and accurate hazard mapping for emergency planning and disaster response. After obtaining the results of the calculations, there was the need to represent them graphically so that any potential stakeholder could easily and immediately understand. As a first test of representation of the calculation results carried out, the Autodesk Revit software was tested as a viewer (the same one also used for the modelling of the school), as seen in

Figure 10, thanks to the communication possibilities of the Dynamo plugin, already illustrated previously, with the system server set up.

A series of example tests were carried out on the BIM model with Dynamo (

Figure 11) to simulate the data update after a request to the database to retrieve hazard calculation results on the area. These included a risk assessment of the building’s functional spaces and a few building component categories (namely walls, windows and doors), of which their respective vulnerability and exposure factors were computed. Through a proper functional categorisation of spaces and a view filter applied to the visualisation of building components within the 3D view of Dynamo itself, it was possible to represent a selection of flood risk scenarios which, based on the intended use of each space and the type and height of the related components of the envelope, the model is themed to immediately and directly show the risk to which the various parts of the building are subject.

The example tests considered the three simple standard parameters related to the most common and consolidated risk assessment practices. The risk is, therefore, split into hazard, vulnerability, and exposure. The hazard factor comes from the calculations performed at the territorial scale, which are directly saved into the database and retrieved by Dynamo through a dedicated call. The vulnerability factor is a parameter associated with each building element and space; therefore, dedicated calculation criteria were set up based on the category of each building component to assess this parameter. For the sake of structuring examples to test the data exchanges, simple assessment expressions were set up. For building spaces, the vulnerability index was considered to be a value directly dependent on the function of each space: i.e.; classrooms have a very high vulnerability while unused or storage spaces have the lowest. On the other hand, the vulnerability of wall elements was based on a calculation set up to compute their thickness and the elevation of their base. Moreover, a combination of sill height and elevation over the ground was used, considering openings like walls and doors. The result of each component’s assessment is then automatically compiled back into the model on a dedicated “vulnerability index” parameter assigned to each element instance. Lastly, the exposure factor is a parameter based on the time and date, meaning that it is considered lower when the spaces of the building are not used, as opposed to when it is crowded with people. These three parameters are collected and computed together in the final script. The results are shown graphically by colouring the desired building elements according to a predefined gradient, as shown in

Figure 12.

4. Conclusion and Discussion

The TERIMAAS framework presented in this study offers a comprehensive approach to bridge the gap between environmental GIS and building-centric BIM scales, thereby enhancing natural hazard assessment and resilience planning. In the context of the built environment, combining data alone with a spatial representation is essential to achieve a practical understanding and definition of events. By establishing a centralised database and integrating disparate formats, including BIM, GIS, and IoT-derived historical and real-time data, TERIMAAS facilitates dynamic risk assessment tailored to evolving environmental conditions across scales.

Specifically, four potential users have been identified that may benefit from this kind of platform, both for management and training/education purposes:

Scientific community. This research provides a potential mechanism for those within the scientific community researching any particular single hazard to contextualise their research within the context of other natural hazards [

42]. The framework will help foster improved communication between hazard and critical infrastructure specialists and encourage a more interdisciplinary approach.

Critical Infrastructure players. Overcoming spatial and temporal scales empowers operators with a much deeper knowledge of the works. In fact, from the perspective of DTs, a punctual understanding of the works in terms of technical data, maintenance procedures, and safety protocols must be supplemented with information that returns their operation in real-time and cast about the characteristics and conditions of the territory in which they are located.

Emergency management and disaster risk reduction practitioners and policymakers. This study simplifies a large amount of complex information to facilitate practical analysis. The developed visualisation schemes can empower stakeholders in these sectors to comprehend and anticipate the impact of hazards at various levels. Specifically, it provides valuable insights for detailed building-specific information, enhancing preparedness and response strategies.

Government and spatial planner. As vulnerability dynamics are likely to change between each component of a hazard cascade scenario, it is essential to understand the potential implications of such scenarios on housing or infrastructure developments [

42].

By continuously refining the TERIMAAS framework, it is possible to equip communities and decision-makers better to anticipate, mitigate, and respond to the growing challenges posed by natural hazards and environmental risks.

5. Future Works

Future research and development should focus on several technical advancements to enhance the TERIMAAS framework. A critical area of exploration is comparing centralised and decentralised databases for managing sensitive data. Centralised databases, currently in use, offer unified data management and streamlined access but pose risks related to data security and single points of failure. Future work should investigate implementing advanced security measures and redundancy protocols to mitigate these risks. Additionally, exploring decentralised databases, such as blockchain or distributed ledger technologies, can enhance data security and resilience, ensuring data integrity and availability even in localised failure scenarios.

Expanding the framework to incorporate multi-hazard assessment capabilities is essential. The system's design is scalable and modular, enabling new risk assessment modules to be added without disrupting existing functionality. Future research should develop algorithms and models capable of dynamically assessing and prioritising risks from various natural hazards, including earthquakes, wildfires, and landslides, alongside floods. This integrated approach will facilitate a transition from single to multi-hazard analysis, providing a more comprehensive risk assessment and enabling more effective mitigation strategies and optimised resource allocation.

Integrating open-source BIM tools into the TERIMAAS framework is another crucial area of future work. While proprietary tools provide extensive out-of-the-box functionalities, they can be restrictive due to cost and limited flexibility. Open-source BIM solutions offer significant customisation options and allow developers to manage their projects better and adapt them over time. Evaluating the performance and interoperability of various open-source BIM tools within the existing framework will be vital for broad adoption and flexibility.

Incorporating AI techniques, such as machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), can significantly enhance the analytical capabilities of the TERIMAAS framework. Using ML algorithms on datasets will enable more accurate forecasting of extreme events, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of their environmental, economic, and social impacts. For instance, it will be possible to evaluate necessary actions based on the specific characteristics of building occupants and equipment concerning flooding events. This approach recognises that an event's impact is determined by the extremeness of a climate or weather variable and by people's exposure and vulnerability. Future research should focus on developing and integrating these AI techniques to enhance predictive analytics and decision support systems, thereby improving the efficiency and effectiveness of resilience planning and disaster management.

By addressing these areas, future research can build on the foundations laid by this study, driving forward the capabilities and impact of integrated risk management systems.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.U. and M.D.; methodology, F.M.U., M.D., and E.I.; software, M.D. and E.I.; validation, F.M.U., M.D., and E.I.; formal analysis, M.D. and E.I.; investigation, F.M.U., M.D., and E.I.; resources, F.M.U., M.D., and E.I.; data curation, M.D. and E.I.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.U., M.D., and E.I.; writing—review and editing, F.M.U., M.D., and E.I.; visualization, M.D. and E.I.; supervision, F.M.U.; project administration, F.M.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access to the data is subject to compliance with ethical and legal restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out within the RETURN Extended Partnership and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (National Recovery and Resilience Plan – NRRP, Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3 – D.D. 1243 2/8/2022, PE0000005) CUP E13C22001860001

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Khallaf, R. , Khallaf L., Anumba C.J., Madubuike O.C. (2022) Review of Digital Twins for Constructed Facilities. Buildings (12): 2029. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. , Zhang T., Deng X., Liu Z.,Tan J. (2021) Digital twin: a state-of-the-art review of its enabling technologies, applications and challenges. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing and Special Equipment, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A. , Fan Z., Day C. and Barlow C. (2019), DT: enabling technology, challenges and open research, IEEE Access, Vol. 8, pp. 108952-108971.

- Khademizadeh, S. , Veisi, A., Zadeh, M. (2013). Do we live an information society? Does it matter?. International Journal of Advanced Research (2013), Volume 1, Issue 3, 362-366.

- Maas, W. (1999). Metacity / Datatown. Uitgeverij 010, Rotterdam.

- Pisano, C. , Lucchesi, F. (2020). City of Data. Contesti. Città, Territori, Progetti, (1), 4–11. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, B. (2017). Access methods for Big Data: current status and future directions. ICST Transactions on Scalable Information Systems. 4. 153520. [CrossRef]

- Laney, D. (2001). 3D Data management: controlling data volume, velocity, and variety. Meta Group Research Note, 6.

- Statista (2024). Volume of data/information created, captured, copied, and consumed worldwide from 2010 to 2020, with forecasts from 2021 to 2025. https://www.statista.com/statistics/871513/worldwide-data-created/.

- Innowise (2024). Big data trends 2024: Navigating the future of data technology. https://innowise.com/blog/big-data-trends-2024/.

- Lazarova-Molnar, S. , Mohamed N. (2020). Collaborative data analytics for smart buildings: opportunities and models. Cluster Comput, No. 22, pp. 1065-1077.

- Planu, F. , Fredduzzi G. (2023). Integrated Digital Platforms for the Management of the Existing Built Heritage: the InSPiRE Project. In Cannella M., Garozzo A., Morena S. (Eds.). Transitions. Proceedings of the 44th International Conference of Representation Disciplines Teachers.; Milano: FrancoAngeli, pp. 3007-3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030, last accessed 2024/05/07.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. https://www.undrr.org/gar/gar2023-special-report, last accessed 2024/05/07.

- Ugliotti, F.M. , Osello A., Daud M., Yilmaz O.O. (2023). Enhancing Risk Analysis toward a Landscape Digital Twin Frawemework: A Multi-Hazard Approach in the Context of a Socio-Economic Perspective. Sustainability (15):12429. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. , Xiangyu W., Wright, G., Cheng, J. C. P., Li, X., Liu, R. (2017). A State-of-the-Art Review on the Integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Geographic Information System (GIS). ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 6, no. 2: 53. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D. , Adhikari S. (2023) The Role of BIM in Integrating Digital Twin in Building Construction: A Literature Review. Sustainability, 15, 10462. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Pan, Y., Luo, X. (2019). Integration of BIM and GIS in sustainable built environment: A review and bibliometric analysis. Automation in Construction, vol. 103, pp. 41-52. ISSN 0926-5805. [CrossRef]

- Shkundalov, D. , Vilutienė, T. (2021). Bibliometric analysis of Building Information Modeling, Geographic Information Systems and Web environment integration. Automation in Construction, vol. 128: 103757. ISSN 0926-5805. [CrossRef]

- Iacono, E. , Ugliotti, F.M., Osello, A. (2023) BIM-GIS Integration for Risk Assessment of Built Heritage: Testing Recent Developments on Italian Public Buildings. DN. BIM-GIS Integration for Risk Assessment of Built Heritage: Testing Recent Developments on Italian Public Buildings, 13, pp. 72-81.

- Khajavi, S.H.; Motlagh, N.H.; Jaribion, A.; Werner, L.C.; Holmström, J. (2019). Digital Twin: Vision, Benefits, Boundaries, and Creation for Buildings. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 147406–147419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. , Wright, G., Wang, J., Wang, X. (2018). A Critical Review of the Integration of Geographic Information System and Building Information Modelling at the Data Level. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 7, no. 2: 66. [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.W. , Hong, C.H. (2015). A study on software architecture for effective BIM/GIS-based facility management data integration. Automation in Construction, vol. 54, pp. 25-38. ISSN 0926-5805. [CrossRef]

- Boguslawski, P. , Mahdjoubi, L., Zverovich, V., Fadli, F., Barki, H. (2015). BIM-GIS modelling in support of emergency response applications. WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, vol. 149, pp. 381-391, WIT Press. [CrossRef]

- Ravankhah, M. , Chliaoutakis, A., Revez, M.J., de Wit, R., Argyriou, A.V., Anwar, A., Heeley, J., Birkmann, J., Sarris, A., Žuvela-Aloise, M. (2020). A Multi-Hazard Platform for Cultural Heritage at Risk: The STORM Risk Assessment and Management Tool. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 949, n. 1, 012111, IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Daud, M. , Ugliotti F.M., Osello A. (2024) Comprehensive Analysis of the Use of Web-Geographic Information System for Natural Hazard Management: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024 (16): 4238. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. , Zhao, J., Wang, J., Su, D., Zhang, H., Guo, M., Guo, M, Li, Z. (2019). OutDet: an algorithm for extracting the outer surfaces of building information models for integration with geographic information systems. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 33(7), 1444–1470. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. , Wang, J., Wang, X., Tan, Y. (2019). An Economical Approach to Geo-Referencing 3D Model for Integration of BIM and GIS. Innovative Production and Construction, 19, pp. 321-334. [CrossRef]

- Planu F., Rizzi D., Fredduzzi G. (2023). Piattaforme digitali integrate per la gestione del patrimonio costruito esistente: il progetto InSPiRE/Integrated Digital Platforms for the Management of the Existing Built Heritage: the InSPiRE Project. In Cannella M., Garozzo A., Morena S. (Eds.). Transizioni. Atti del 44° Convegno Internazionale dei Docenti delle Discipline della Rappresentazione/Transitions. Proceedings of the 44th International Conference of Representation Disciplines Teachers. Milano: FrancoAngeli, pp. 3007-3022. [CrossRef]

- Basir, W. N. F. W. A., Ujang, U., Majid, Z. (2021). Building Information Modeling (BIM) And Geographic Information System (GIS) Data Compatibility For Construction Project. Journal of Information System and Technology Management, 6 (24), 278-289. [CrossRef]

- Antofie, T. , Doherty, B. Marin Ferrer, M. (2018). Mapping of risk web-platforms and risk data: collection of good practices, EUR 29086 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2018, ISBN 978-92-79-80171-6, JRC109146. [CrossRef]

- Sani, M.J. , Abdul Rahman, A. (2018). GIS and BIM Integration at Data Level: a Review. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLII-4/W9, pp. 299-306. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. , Wang, X., Wang, P., Wu, Z., Kim, M.J. (2019). Integration of BIM and GIS: Geometry from IFC to shapefile using open-source technology. Automation in Construction, vol. 102, pp. 105-119. ISSN 0926-5805. [CrossRef]

- Narindri, B.P.K. , Nugroho, A.S.B., Aminullah, A. (2022). Developing Building Management System Framework using Web-based-GIS and BIM Integration. Civil Engineering Dimension, 24(2), 71-84. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. , Shelden, D.R., Eastman, C.M., Pishdad-Bozorgi, P., Gao, X. (2019). A review of building information modeling (BIM) and the internet of things (IoT) devices integration: Present status and future trends. Automation in Construction, vol. 101, pp. 127-139. ISSN 0926-5805. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. , Zhang, L. (2021). A BIM-data mining integrated digital twin framework for advanced project management. Automation in Construction, vol. 124, 103564. ISSN 0926-5805. [CrossRef]

- Shahinmoghadam, M. , Motamedi, A. (2021). An Ontology-Based Mediation Framework for Integrating Federated Sources of BIM and IoT Data. Toledo Santos, E., Scheer, S. (eds) Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Computing in Civil and Building Engineering. ICCCBE 2020. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol 98. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.P. , Deng, Y. (2015). An Integrated BIM-GIS Framework for Utility Information Management and Analyses. Computing in Civil Engineering, pp. 667-674. [CrossRef]

- Abdalwhab, A.A.B. , Haron, N.A., Ales, A.H., and Teik Hua Law. 2021. Investigating Approaches of Integrating BIM, IoT, and Facility Management for Renovating Existing Buildings: A Review. Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3930. [CrossRef]

- PostgreSQL: The World's Most Advanced Open Source Relational Database. https://www.postgresql.org/, last accessed 2024/05/14.

- Kirschbaum, D. , Stanley T. (2018) Satellite-Based Assessment of Rainfall-Triggered Landslide Hazard for Situational Awareness. Earth’s Future (6): 505-523. [CrossRef]

- Gill, J. C., B. D. Malamud (2014). Reviewing and visualizing the interactions of natural hazards, Rev. Geophys., 52, 680–722. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013RG000445. [CrossRef]

- GitHub - opengeos/python-geospatial: A collection of Python packages for geospatial analysis with binder-ready notebook examples. https://github.com/opengeos/python-geospatial, last accessed 2024/05/15.

- Osello, A. , Fonsati A, Rapetti N., Semeraro F. (eds.) (2019) InfraBIM. Il BIM per le infrastrutture. Gangemi Editore, Roma.

- Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) – buildingSMART Italia. https://www.buildingsmartitalia.org/standard/standard-bs/industry-foundation-classes-ifc/, last accessed 2024/05/12.

- Introduction to Visual Programming in Architecture. https://www.novatr.com/blog/visual-programming-in-architecture, last accessed 2024/05/13.

- The Dynamo Primer. https://primer.dynamobim.org/, last accessed 2024/05/15.

- FME by Safe Software. https://fme.safe.com/, last accessed 2024/05/15.

- Geodan/pg2b3dm: Tool for creating 3D Tiles from PostGIS geometries. https://github.com/Geodan/pg2b3dm, last accessed 2024/05/13.

- Regione Piemonte, Classificazione sismica. https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/temi/protezione-civile-difesa-suolo-opere-pubbliche/prevenzione-rischio-sismico/classificazione-sismica, last accessed 2024/07/31.

- GeoStru. Geoapp. Mappa di zonazione sismica Regione Piemonte 2020. https://geoapp.geostru.eu/app/classificazione-sismica-regione-piemonte-2020/, last accessed 2024/07/31.

- ISPRA - Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale. Rapporto sulle condizioni di pericolosità da alluvione in Italia e indicatori di rischio associati, 353/2021. https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/pubblicazioni/rapporti/rapporto-sulle-condizioni-di-pericolosita-da-alluvione-in-italia-e-indicatori-di-rischio-associati, last accessed 2024/07/15.

- Geoportale Arpa Piemonte. Conoidi alluvionali in Piemonte. https://geoportale.arpa.piemonte.it/app/public/?pg=mappa&ids=5554d33c511140e0acc77ff46fcac86c, last accessed 2024/07/15.

- Autodesk. Level of Development (LOD) in BIM. https://www.autodesk.com/solutions/bim-levels-of-development, last accessed 2024/08/01.

- European Union. TINITALY, a digital elevation model of Italy with a 10 meters cell size (Version 1.1). https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/ingv-https-data-ingv-it-metadata-iso19115-807-xml?locale=en, last accessed 2024/08/05.

- USGS. EarthExplorer. https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/, last accessed 2024/08/05.

- Open-Meteo. Weather Forecast API. https://open-meteo.com/en/docs, last accessed 2024/05/02.

- Open-Meteo. Climate API. https://open-meteo.com/en/docs/climate-api, last accessed 2024/05/02.

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. https://land.copernicus.eu/en/map-viewer?product=130299ac96e54c30a12edd575eff80f7, last accessed 2024/08/05.

- ISPRA. IdroGEO - Open Data. https://idrogeo.isprambiente.it/app/page/open-data, last accessed 2024/08/05.

- US Army Corps of Engineers, Hidrologic Engineering Center. HEC-HMS (Hidrologic Modeling System). https://www.hec.usace.army.mil/software/hec-hms/, last accessed 2024/08/06.

- Open-Meteo. Free Open-Source Weather API. https://open-meteo.com/, last accessed 2024/05/02.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).