Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Modeling

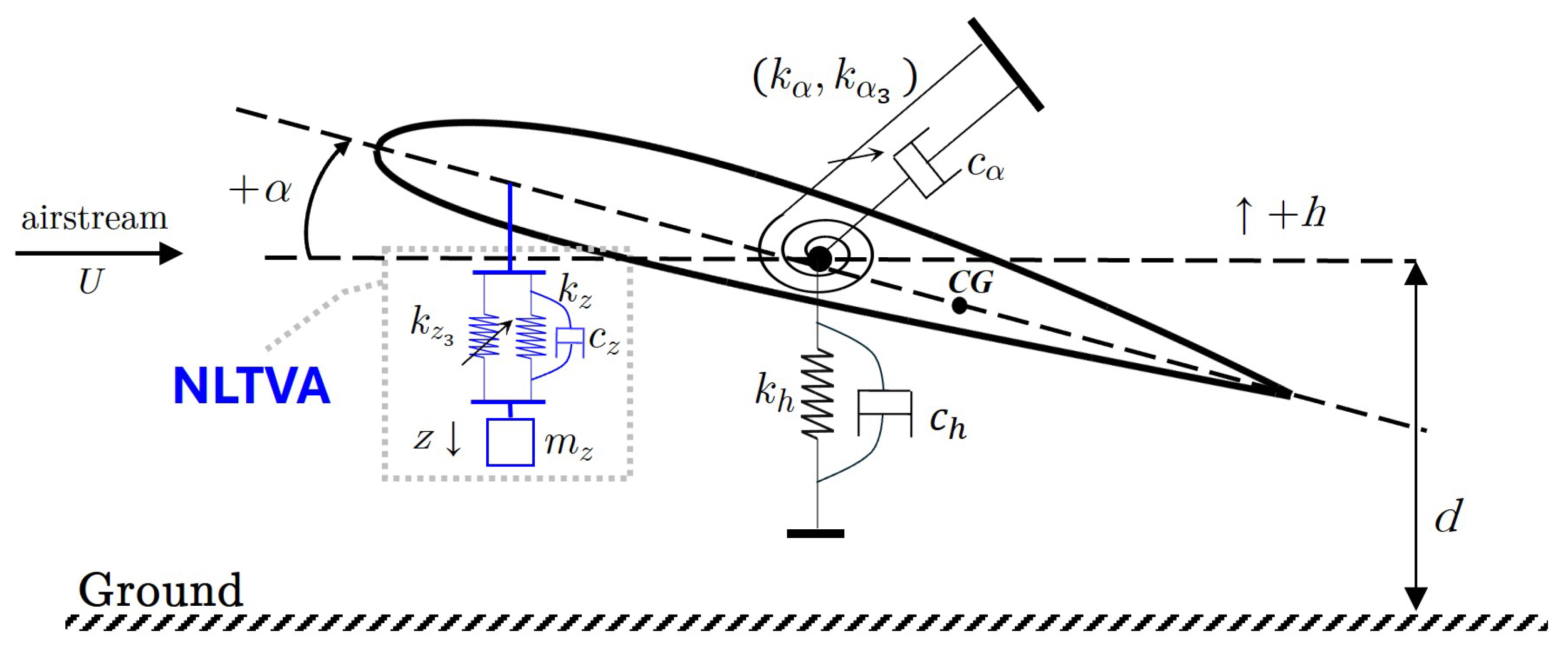

2.1. Typical Airfoil Section with Nonlinear Absorber

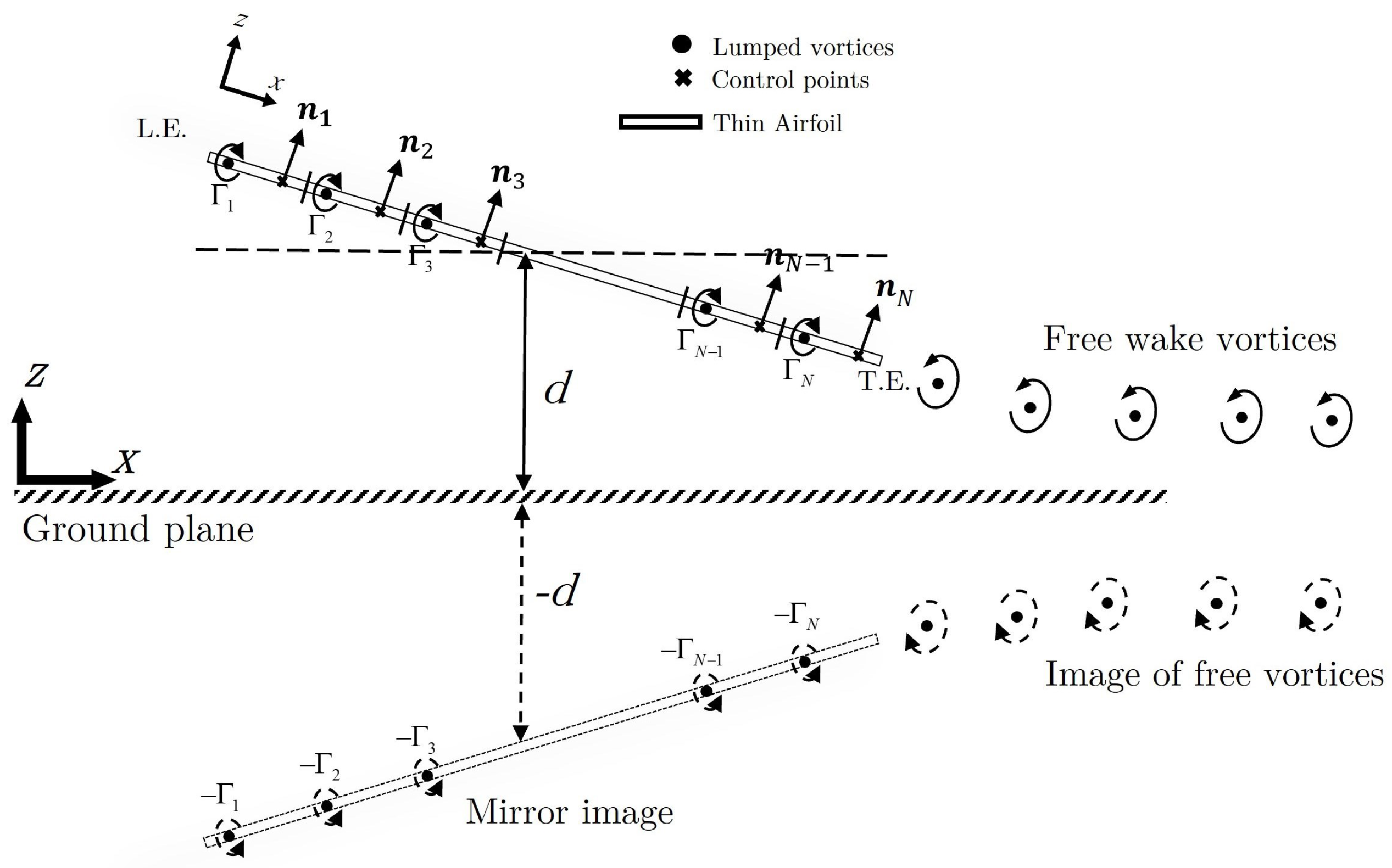

2.2. Ground Effect Aerodynamics

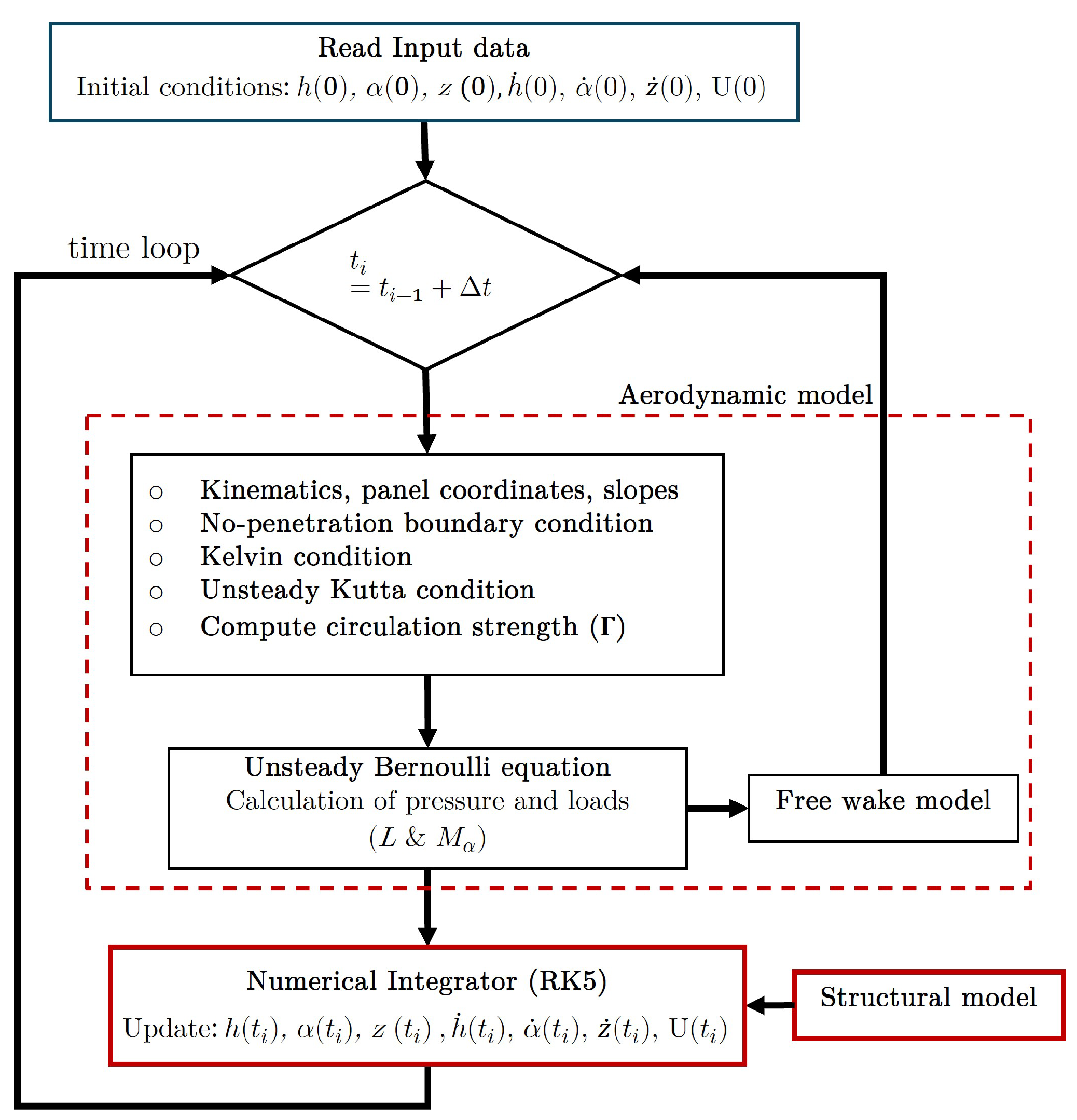

2.3. Aeroelastic Solution

3. Results and Discussion

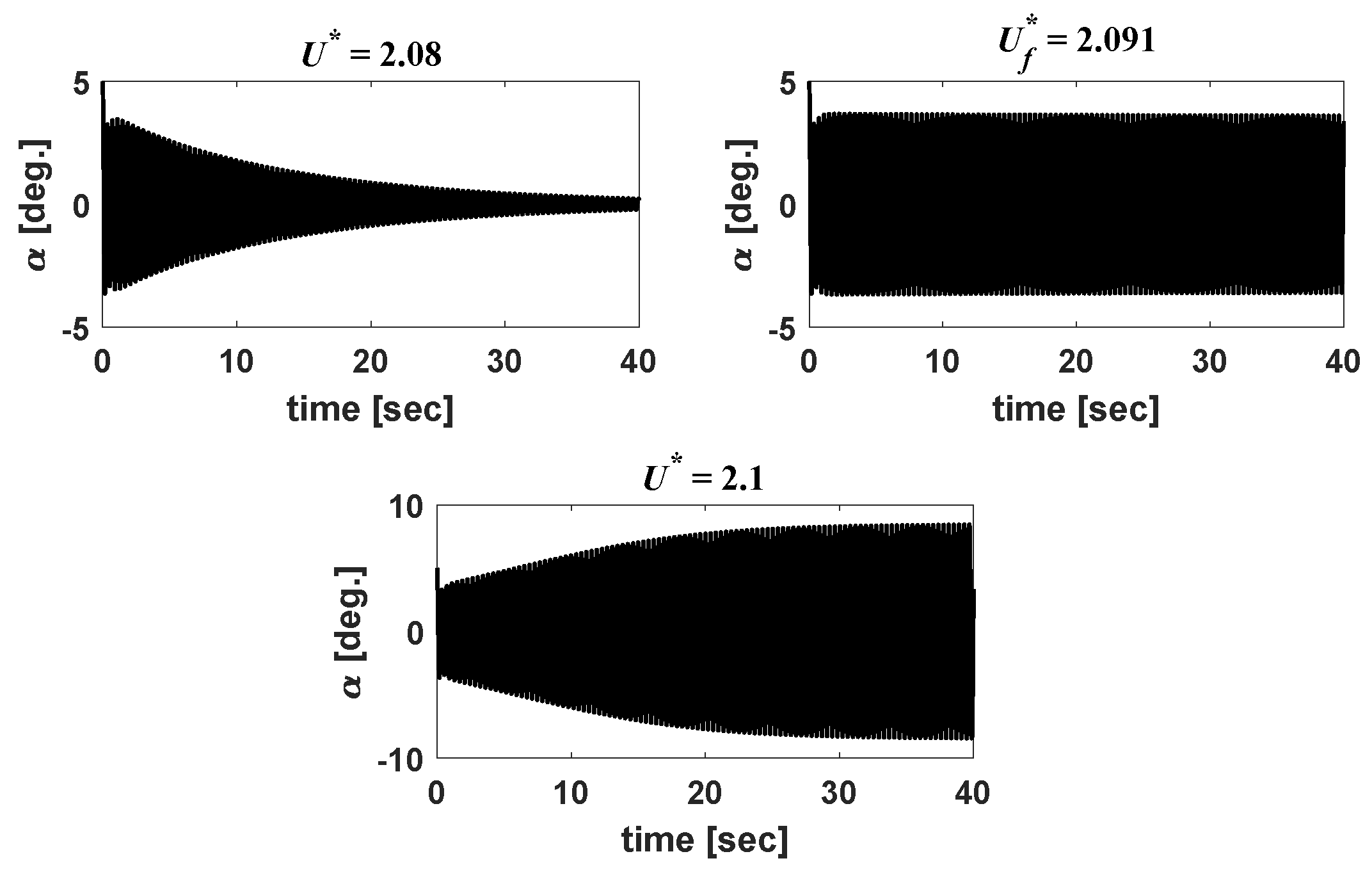

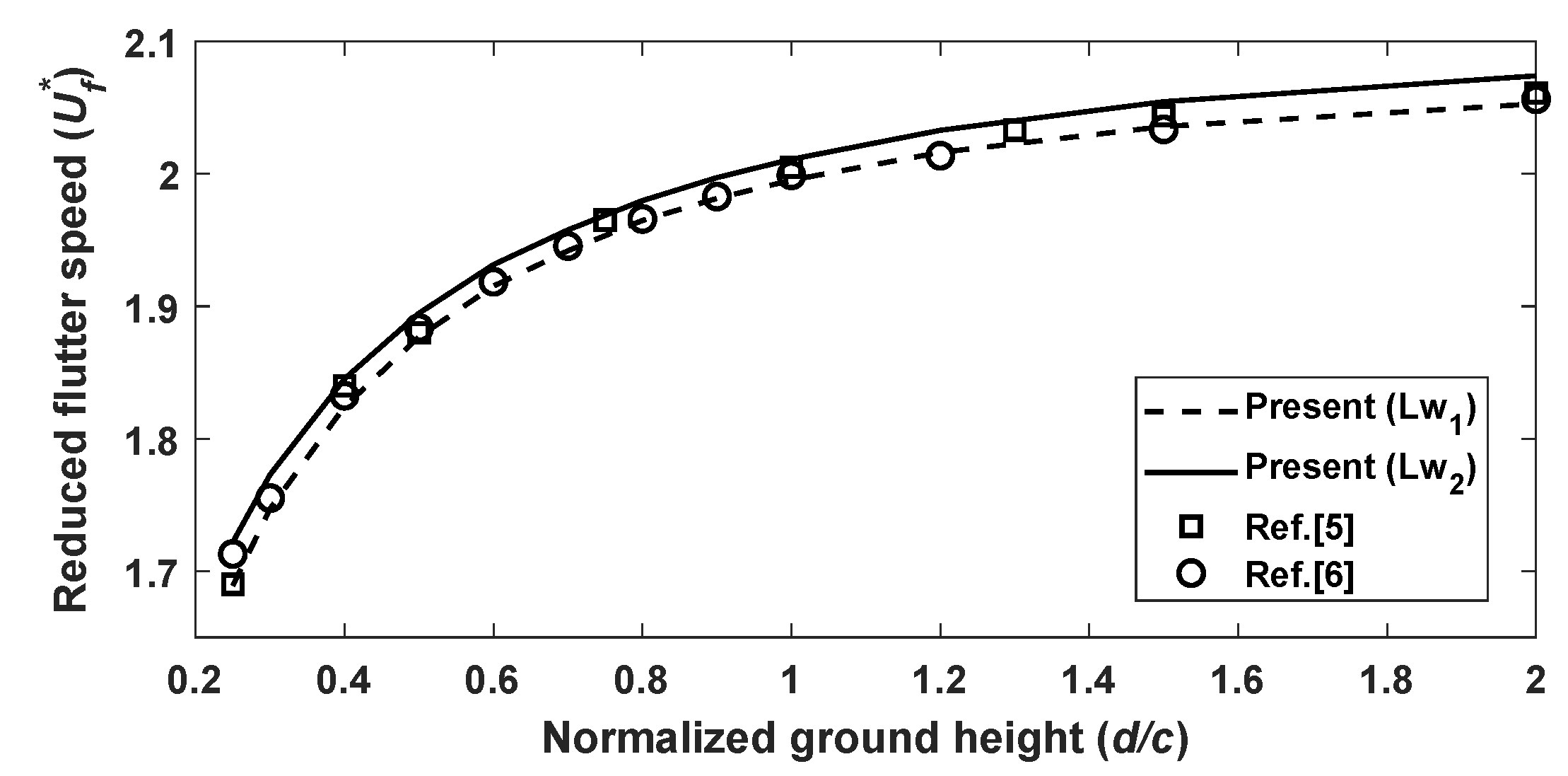

3.1. Model Validation

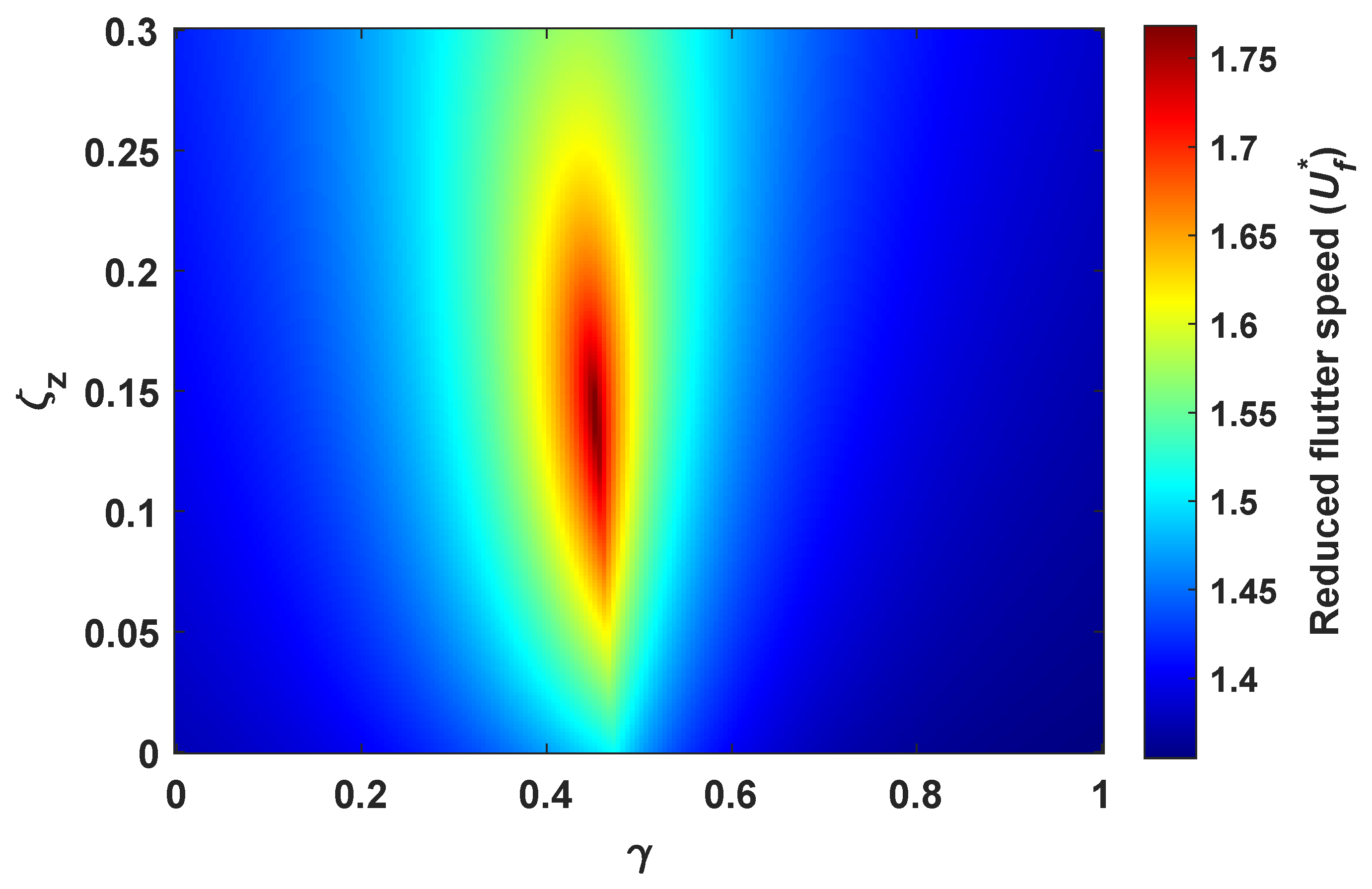

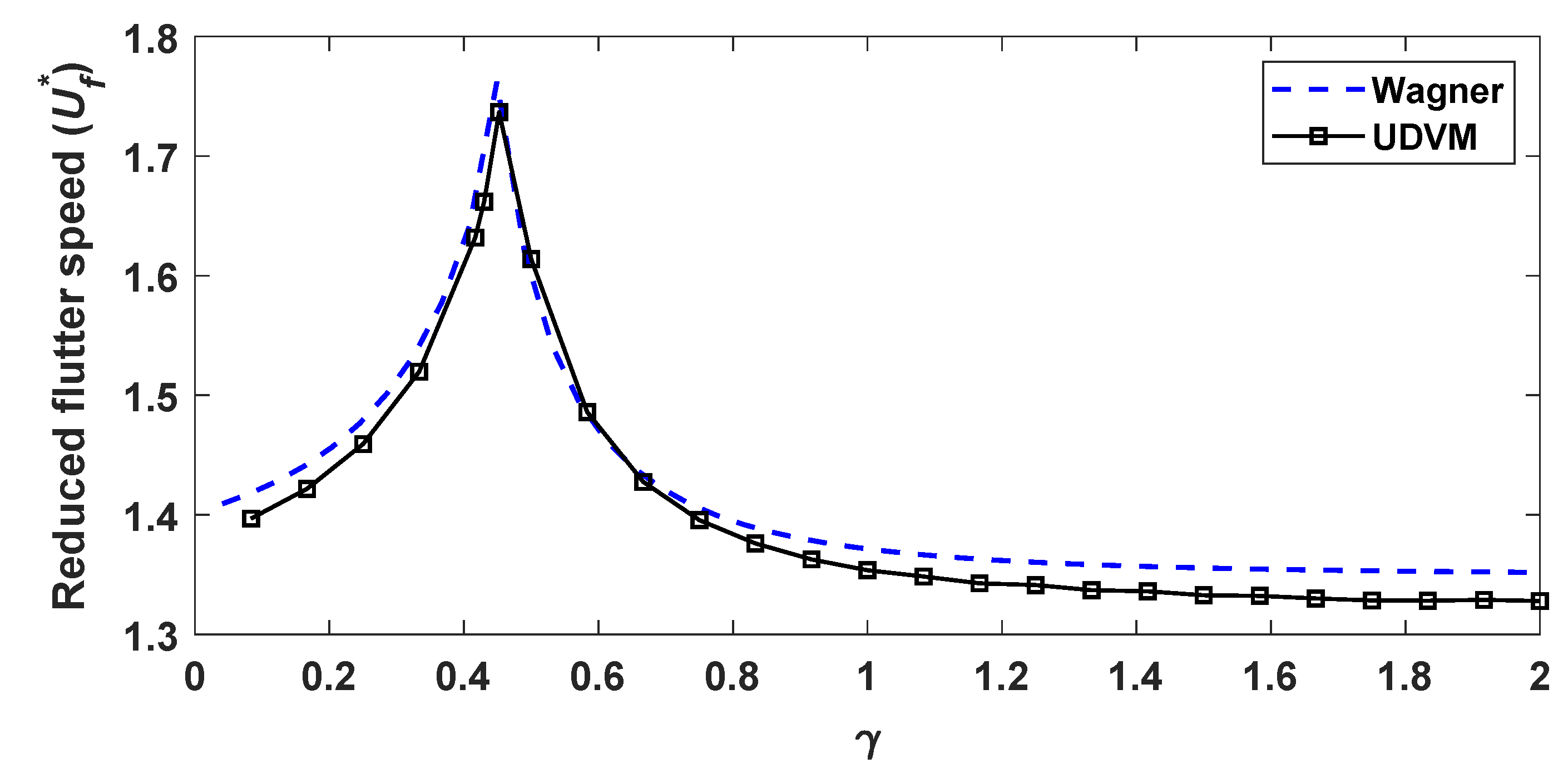

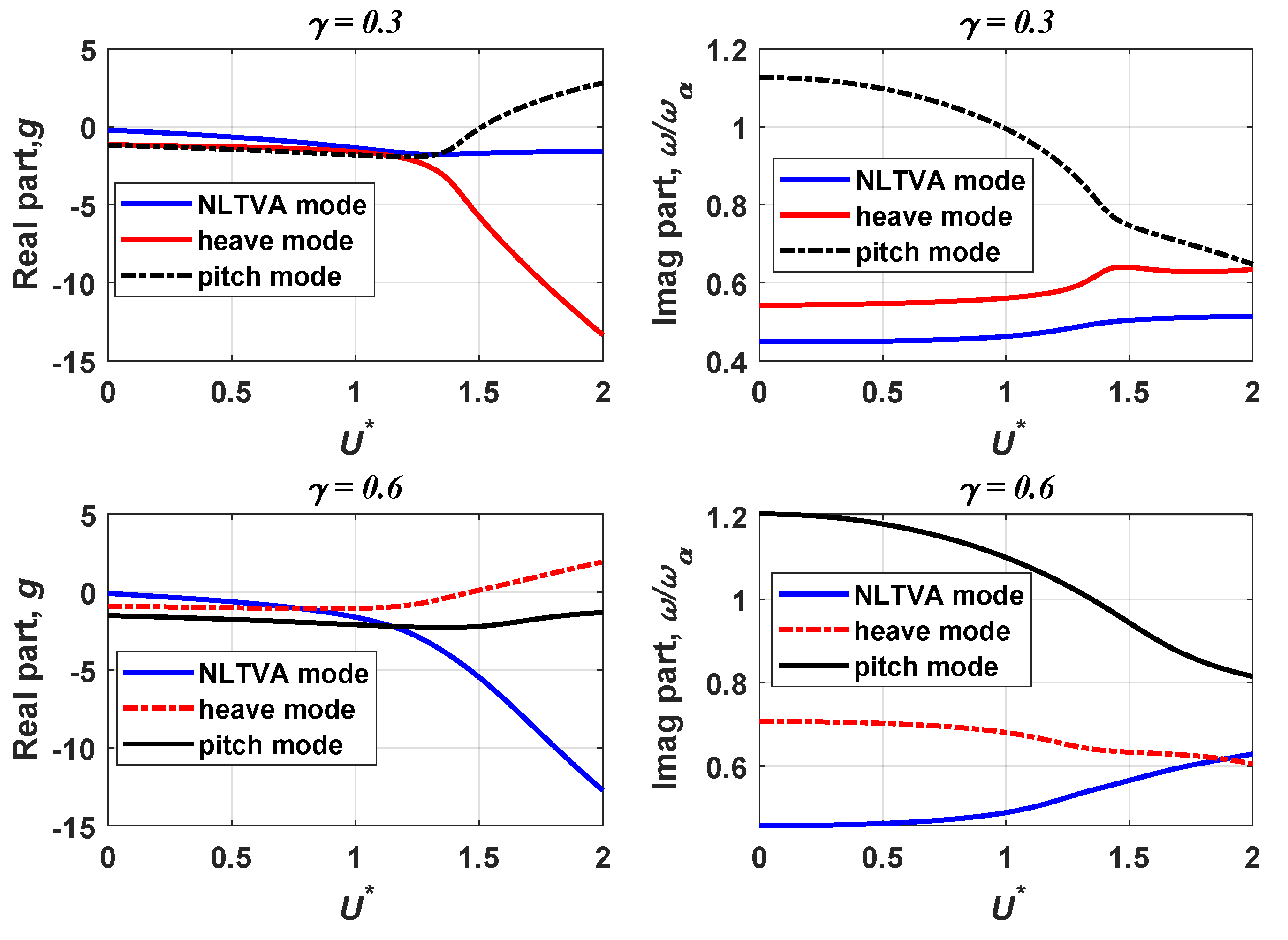

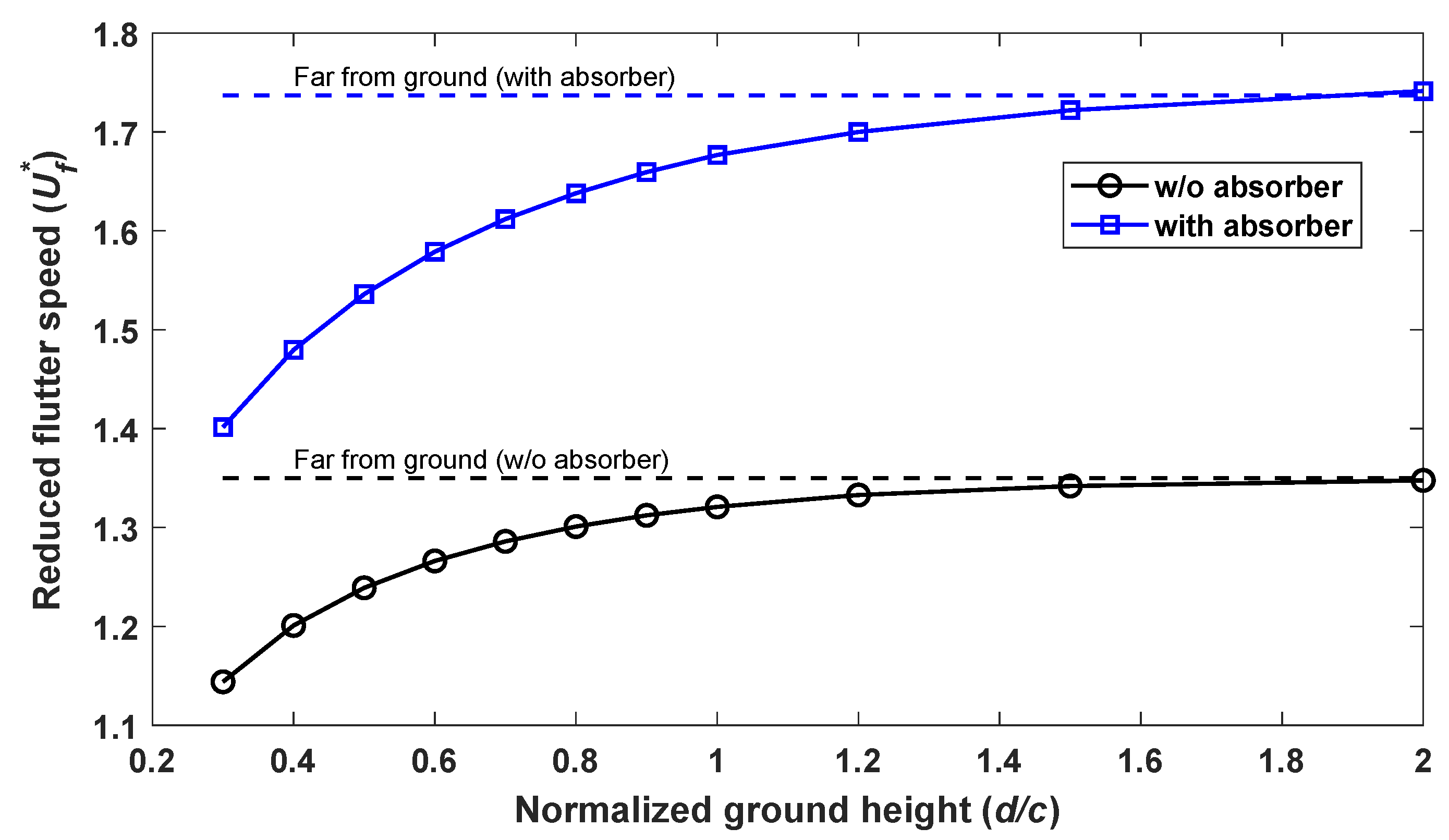

3.2. Linear Flutter Analysis

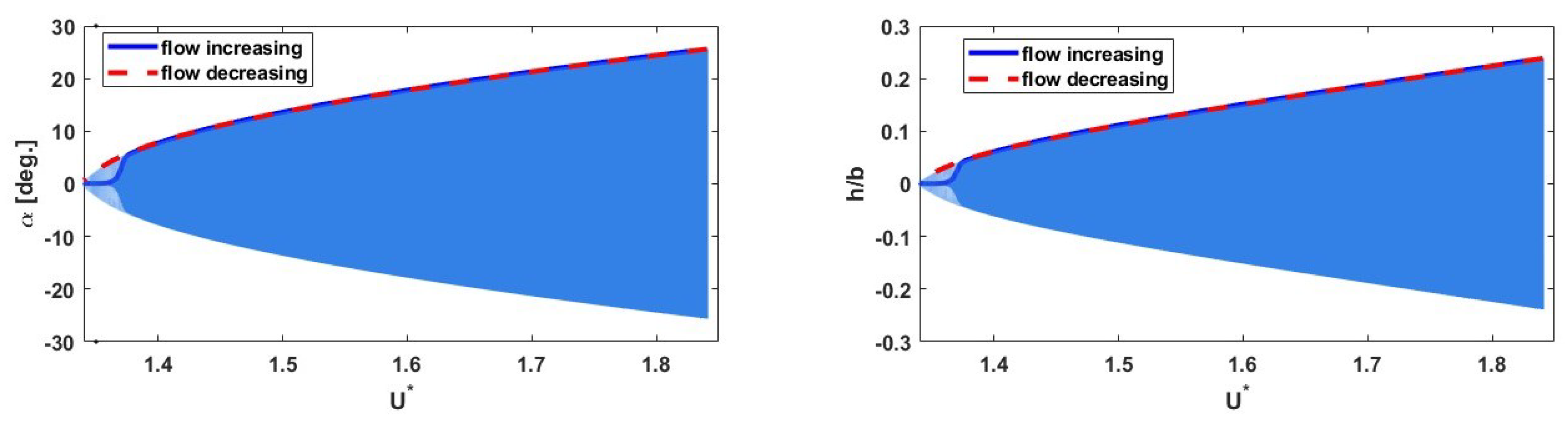

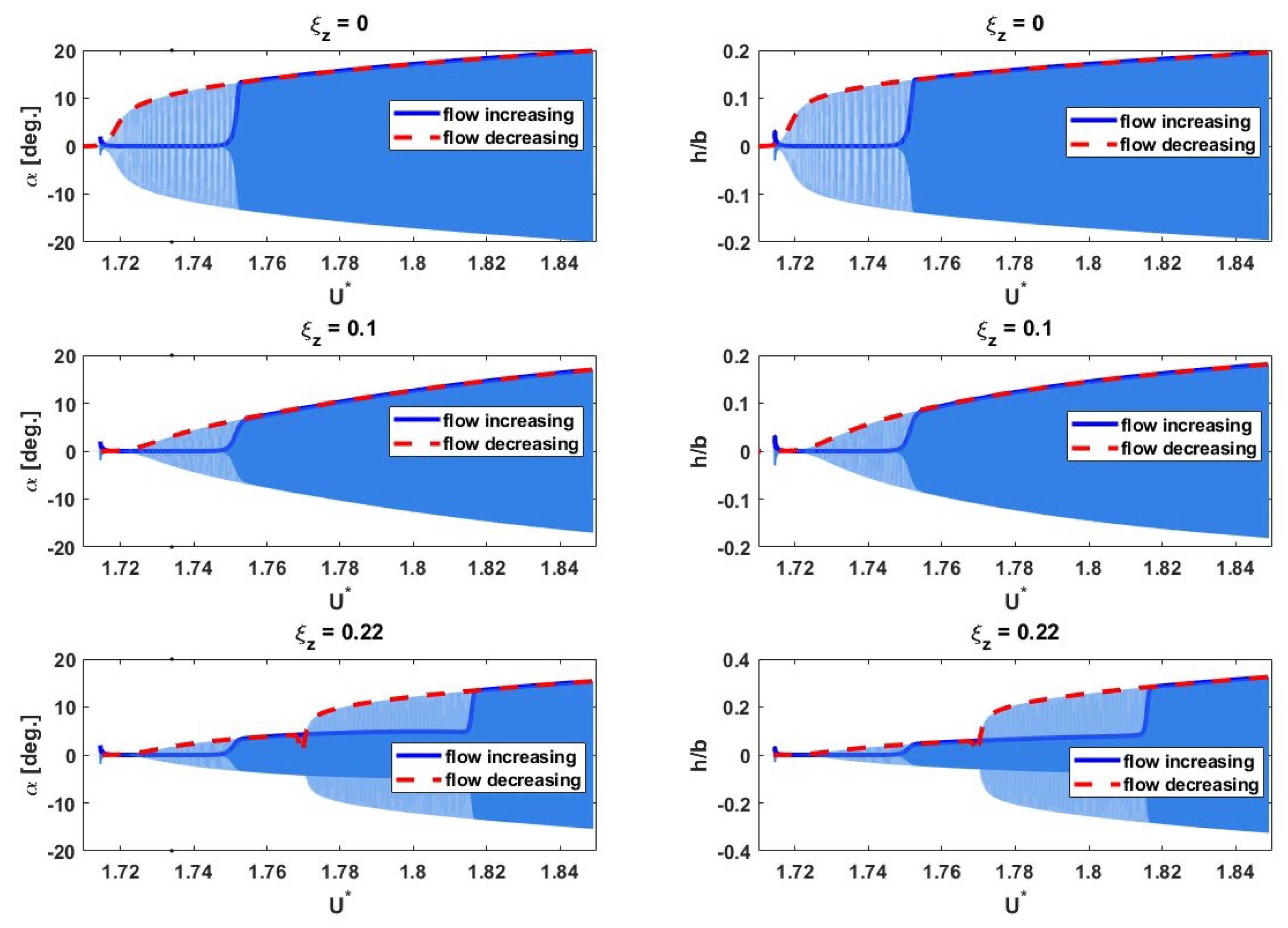

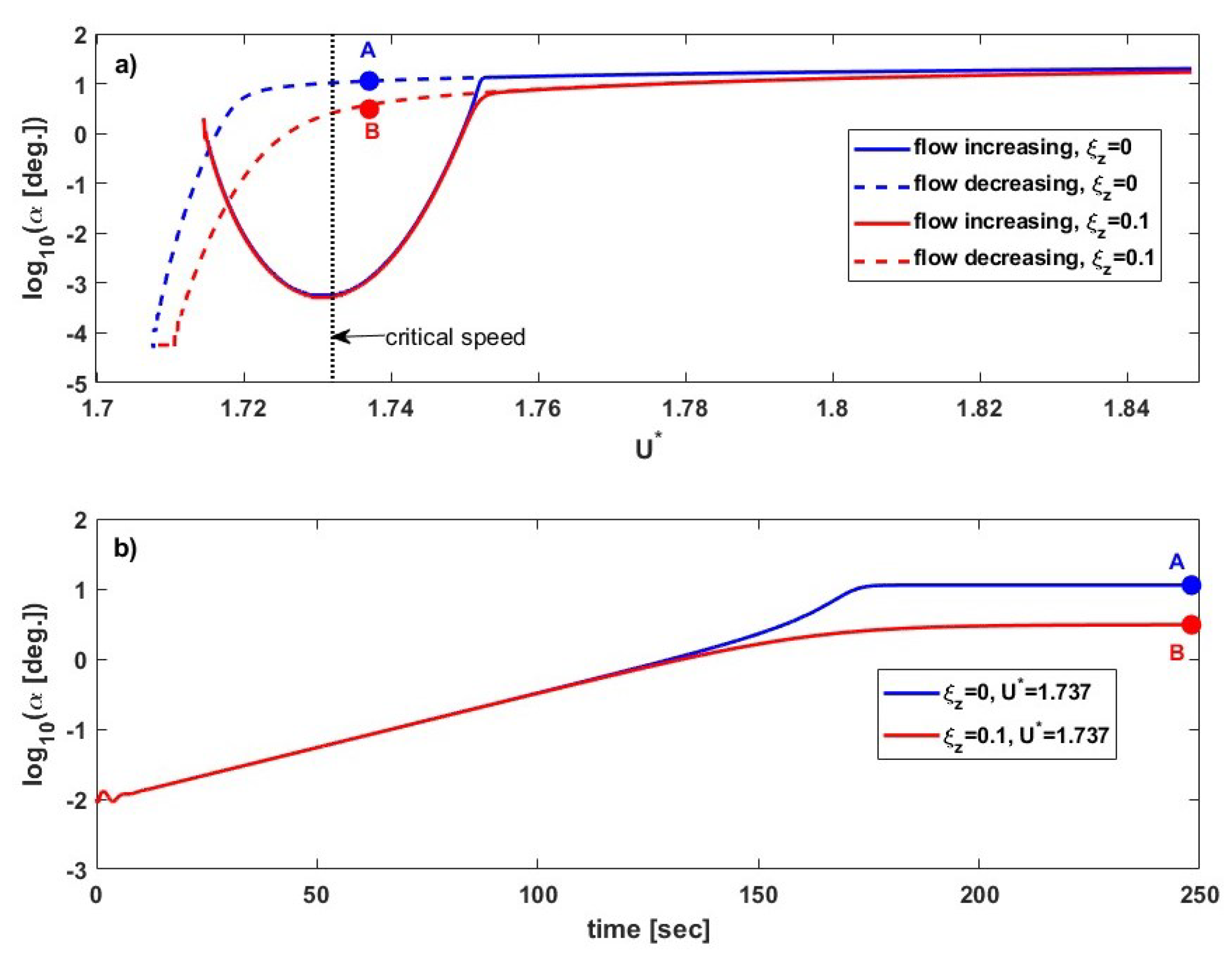

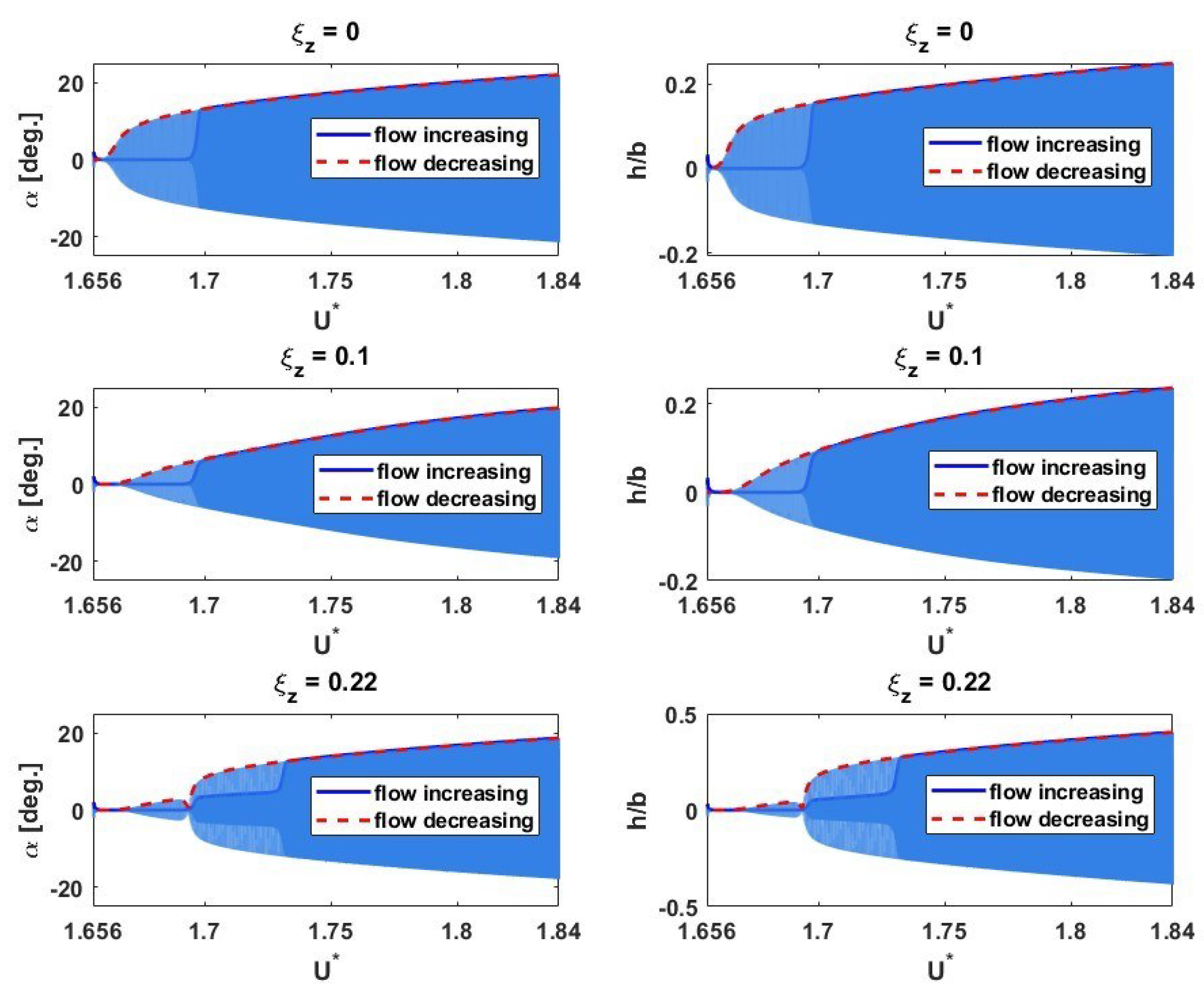

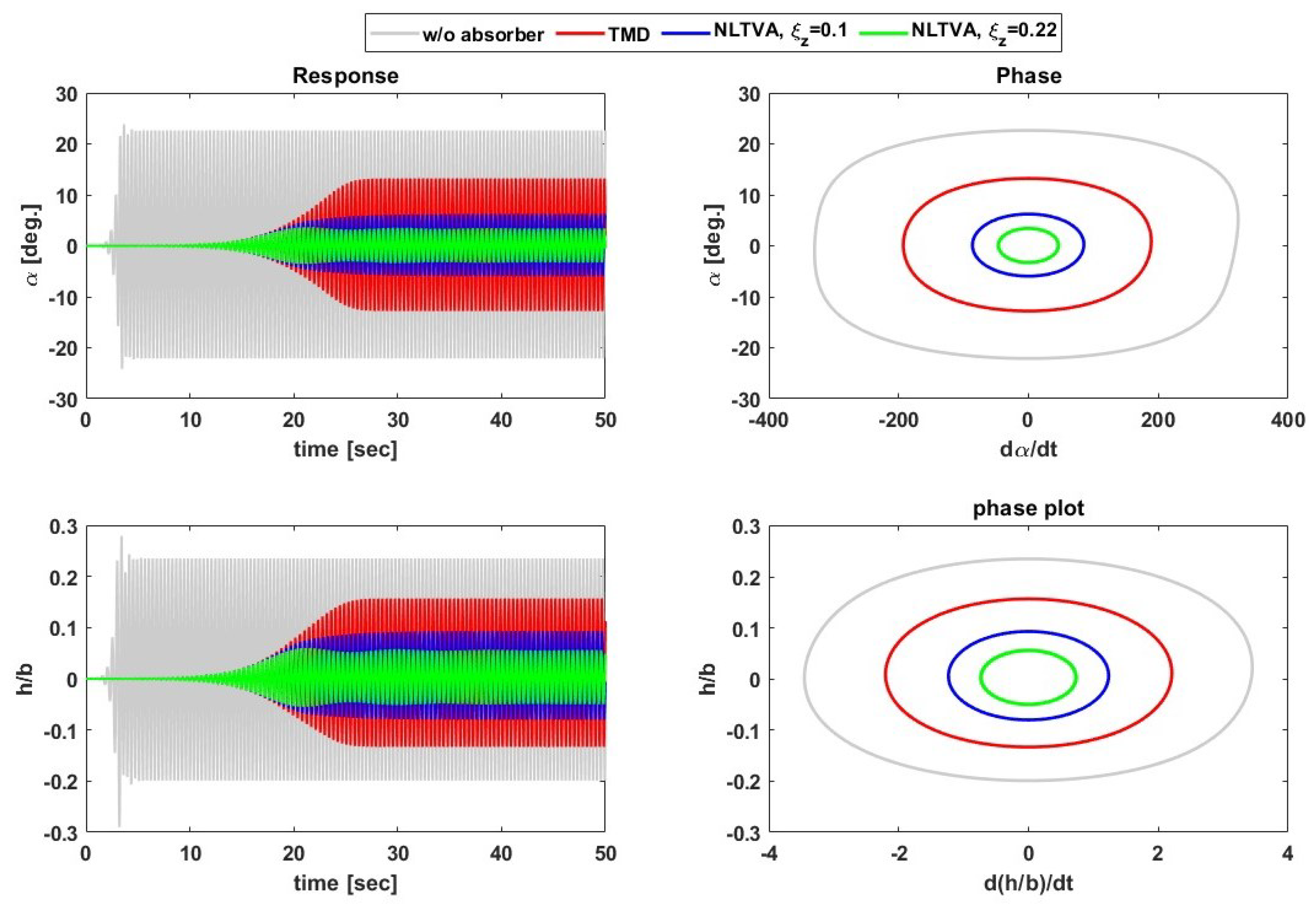

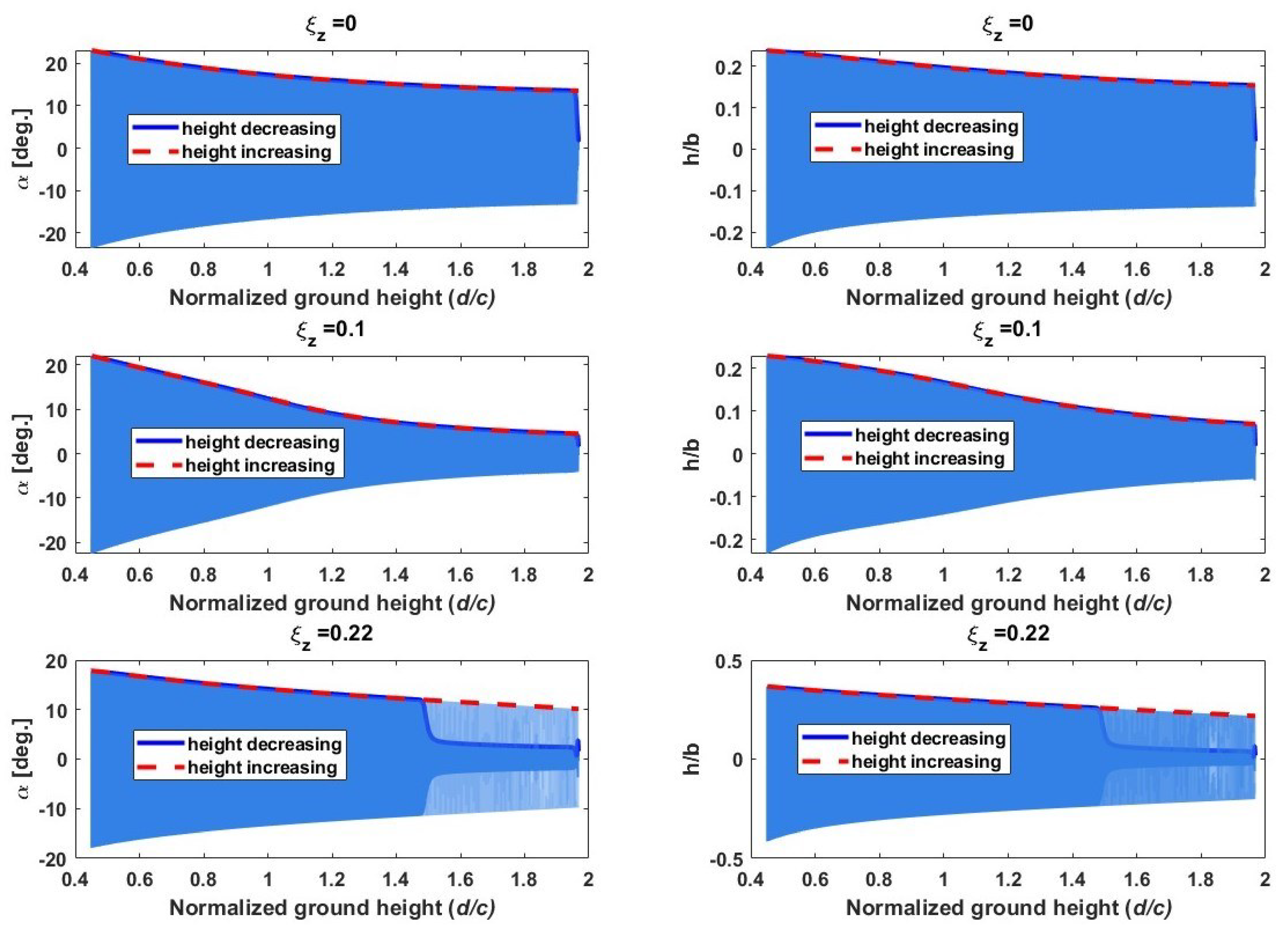

3.3. Post-Flutter Analysis with a Nonlinear Structural Model

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Palacios, R.; Cesnik, C. Dynamics of Flexible Aircraft: Coupled Flight Mechanics, Aeroelasticity, and Control; Cambridge Aerospace Series, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

- Amato, E.M.; Polsinelli, C.; Cestino, E.; Frulla, G.; Joseph, N.; Carrese, R.; Marzocca, P. HALE wing experiments and computational models to predict nonlinear flutter and dynamic response. The Aeronautical Journal 2019, 123, 912–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, K.; Nguyen, A.T.; Han, J.H. Aeroelastic modeling and analysis of wings in proximity. Aerospace Science and Technology 2022, 130, 107955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.F.; Hunsaker, D.F. Lifting-Line Predictions for Induced Drag and Lift in Ground Effect. Journal of Aircraft 2013, 50, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, K.; Han, J.H. Ground Effect on Flutter and Limit Cycle Oscillation of Airfoil with Flap. Journal of Aircraft 2021, 58, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhait, A.O.; Mook, D.T. Aeroelastic Behavior of Flat Plates Moving Near the Ground. Journal of Aircraft 2010, 47, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librescu, L.; Marzocca, P. Advances in the linear/nonlinear control of aeroelastic structural systems. Acta Mechanica 2005, 178, 147–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livne, E. Aircraft Active Flutter Suppression: State of the Art and Technology Maturation Needs. Journal of Aircraft 2018, 55, 410–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhou, L. Semi-active flutter control of a high-aspect-ratio wing using multiple MR dampers. Sensors and Smart Structures Technologies for Civil, Mechanical, and Aerospace Systems 2007; Tomizuka, M.; Yun, C.B.; Giurgiutiu, V., Eds. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, 2007, Vol. 6529, p. 65291C. [CrossRef]

- Almajhali, K.Y.M. Review on passive energy dissipation devices and techniques of installation for high rise building structures. Structures 2023, 51, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattulli, V.; Luongo, A.; others. Nonlinear tuned mass damper for self-excited oscillations. Wind and Structures 2004, 7, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcorta, R.; Chouvion, B.; Michon, G.; Montagnier, O. On the use of frictional dampers for flutter mitigation of a highly flexible wing. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 2023, 156, 104515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Griffin, J.H. Friction damping of flutter in gas turbine engine airfoils. Journal of Aircraft 1983, 20, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Vakakis, A.F.; Bergman, L.A.; McFarland, D.M.; Kerschen, G. Suppression Aeroelastic Instability Using Broadband Passive Targeted Energy Transfers, Part 1: Theory. AIAA Journal 2007, 45, 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kerschen, G.; McFarland, D.M.; Hill, W.J.; Nichkawde, C.; Strganac, T.W.; Bergman, L.A.; Vakakis, A.F. Suppressing Aeroelastic Instability Using Broadband Passive Targeted Energy Transfers, Part 2: Experiments. AIAA Journal 2007, 45, 2391–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, T. Passive control of nonlinear aeroelasticity in hypersonic 3-D wing with a nonlinear energy sink. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2019, 462, 114942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Escudero, C.; Prothin, S.; Laurendeau, E.; Ross, A.; Michon, G. Nonlinear flap for passive flutter control of bidimensional wing. Journal of Vibration and Control 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Pérez, J.; Ghadami, A.; Sanches, L.; Michon, G.; Epureanu, B.I. Data-driven optimization for flutter suppression by using an aeroelastic nonlinear energy sink. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2022, 114, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malher, A.; Touzé, C.; Doaré, O.; Habib, G.; Kerschen, G. Passive control of airfoil flutter using a nonlinear tuned vibration absorber. 11th International Conference on Flow-induced vibrations, FIV2016, 2016.

- Malher, A.; Touzé, C.; Doaré, O.; Habib, G.; Kerschen, G. Flutter Control of a Two-Degrees-of-Freedom Airfoil Using a Nonlinear Tuned Vibration Absorber. Journal of Computational and Nonlinear Dynamics 2017, 12, 051016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacarbonara, W.; Cetraro, M. Flutter Control of a Lifting Surface via Visco-Hysteretic Vibration Absorbers. International Journal of Aeronautical and Space Sciences 2011, 12, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraelen, E.; Habib, G.; Kerschen, G.; Dimitriadis, G. Experimental Passive Flutter Suppression Using a Linear Tuned Vibration Absorber. AIAA Journal 2017, 55, 1707–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Escudero, C.; Prothin, S.; Laurendeau, E.; Ross, A.; Michon, G. Nonlinear flap for passive flutter control of bidimensional wing. Journal of Vibration and Control 2023, 0, 10775463231223778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorsen, T. General Theory of Aerodynamic Instability and the Mechanism of Flutter. 1934.

- Moryossef, Y.; Levy, Y. Effect of Oscillations on Airfoils in Close Proximity to the Ground. AIAA Journal 2004, 42, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.; Zhang, X. Aerodynamics of a Heaving Airfoil in Ground Effect. AIAA Journal 2011, 49, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhait, A.O.; Zedan, M.F. Numerical simulation of unsteady flow induced by a flat plate movingnear ground. Journal of Aircraft 1993, 30, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Yoon, Y.; Cho, J. Unsteady Aerodynamic Analysis of Tandem Flat Plates in Ground Effect. Journal of Aircraft 2002, 39, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.; Alighanbari, H.; Lee, B. The Aeroelastic Response of a Two-Dimensional Airfoil with Bilinear and Cubic Structural Nonlinearities. Journal of Fluids and Structures 1995, 9, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Price, S.; Wong, Y. Nonlinear aeroelastic analysis of airfoils: bifurcation and chaos. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 1999, 35, 205–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Plotkin, A. , Frontmatter. In Low-Speed Aerodynamics; Cambridge Aerospace Series, Cambridge University Press, 2001; p. i–vi.

- Ramasamy, M.; Leishman, J.G. A Reynolds Number-Based Blade Tip Vortex Model. Journal of The American Helicopter Society 2007, 52, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, K.; Han, J.H. Aeroelastic Behavior of Two Airfoils in Proximity. AIAA Journal 2022, 60, 2522–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alighanbari, H.; Price, S.J. The post-Hopf-bifurcation response of an airfoil in incompressible two-dimensional flow. Nonlinear Dynamics 1996, 10, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| a | -0.1 |

| 0.2 | |

| 0.5 | |

| 0.5 | |

| 0.1 | |

| 0.01 | |

| 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).