Submitted:

08 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Model

- WRT = 1:

(BARE_SOIL*-0,027)-(MIN_MONTH_TEMP*-0,067).

- WRT = 2:

(BARE_SOIL*-0,027)-(MIN_MONTH_TEMP*-0,067).

- WRT = 3:

(BARE_SOIL*-0,027)-(MIN_MONTH_TEMP*-0,067).

3. Discussion

3.1. Importance of Predictive Richness Models

3.2. Ecological Aspects

4. Materials and Methods

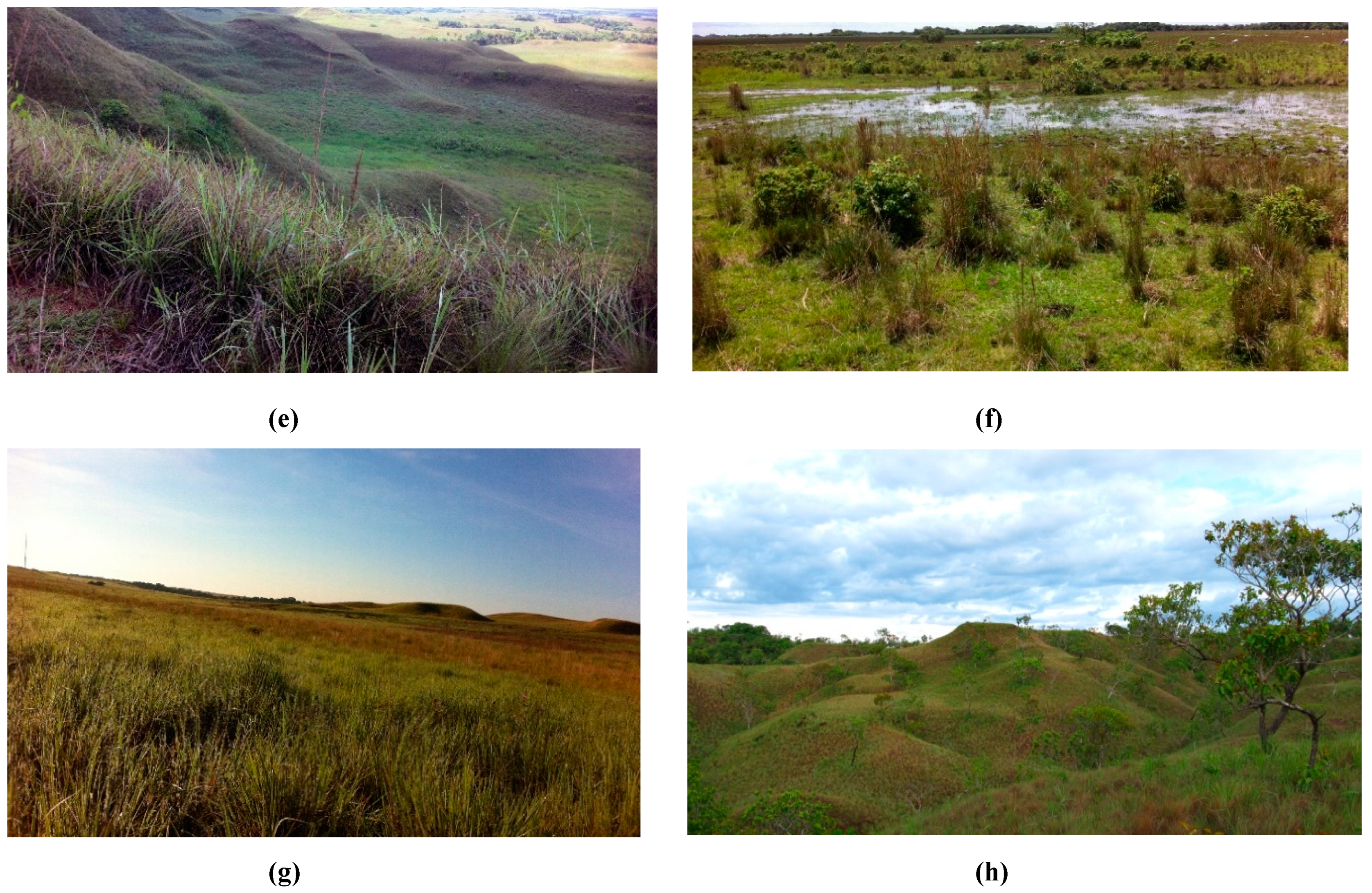

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Data Set

4.3. Statistical Framework

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Geographic Location of Grassland Plots. Area 10*10m

| Id_Plot | Plot | Physiography | Location | Spp. No. | pH | Parent material | Precipitation mm | Slope | Vegetation Cover (%) | Bare Soil (%) | Longitude | Latitude | Altitude |

| 1 | S.11 | High plain | Manacacías | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°27´16.95" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 2 | S.13 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°27´16.97" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 3 | S.15 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°27´16.99" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 4 | S.17 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 94 | 6 | 72°27´16.1" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 5 | S.18 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°27´16.1" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 6 | S.14 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°27´16.98" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 7 | S.12 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°27´16.96" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 8 | S.39 | High plain | Manacacías | 5 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 169 |

| 9 | S.21 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°24´16.11" | 3°26´46.32" | 166 |

| 10 | S.22 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°24´16.11" | 3°26´46.32" | 166 |

| 11 | S.23 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°24´16.11" | 3°26´46.32" | 166 |

| 12 | S.24 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°24´16.11" | 3°26´46.32" | 166 |

| 13 | S.25 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°24´16.11" | 3°26´46.32" | 166 |

| 14 | S.26 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°24´16.11" | 3°26´46.32" | 162 |

| 15 | S.1 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°27´16.85" | 3°29´50.53" | 169 |

| 16 | S.2 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°27´16.86" | 3°29´50.53" | 169 |

| 17 | S.10 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°27´16.94" | 3°29´50.53" | 170 |

| 18 | S.5 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°27´16.89" | 3°29´50.53" | 169 |

| 19 | S.6 | High plain | Manacacías | 4 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°27´16.9" | 3°29´50.53" | 170 |

| 20 | S.7 | High plain | Manacacías | 5 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°27´16.91" | 3°29´50.53" | 170 |

| 21 | S.9 | High plain | Manacacías | 5 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°27´16.93" | 3°29´50.53" | 170 |

| 22 | S.19 | High plain | Manacacías | 4 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 28 | 72 | 72°27´16.1" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 23 | S.27 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°24´16.11" | 3°26´46.32" | 162 |

| 24 | S.30 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°24´16.11" | 3°26´46.32" | 162 |

| 25 | S.3 | High plain | Manacacías | 6 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°27´16.87" | 3°29´50.53" | 169 |

| 26 | S.8 | High plain | Manacacías | 4 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°27´16.92" | 3°29´50.53" | 170 |

| 27 | S.61 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 183 |

| 28 | S.64 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 183 |

| 29 | S.65 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 183 |

| 30 | S.66 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 180 |

| 31 | S.67 | High plain | Manacacías | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 88 | 12 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 180 |

| 32 | S.71 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 200 |

| 33 | S.73 | High plain | Manacacías | 19 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 200 |

| 34 | S.75 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 200 |

| 35 | S.101 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°26´16.19" | 3°30´29.27" | 186 |

| 36 | S.102 | High plain | Manacacías | 21 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°26´16.19" | 3°30´29.27" | 186 |

| 37 | S.103 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°26´16.19" | 3°30´29.27" | 186 |

| 38 | S.104 | High plain | Manacacías | 20 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°26´16.19" | 3°30´29.27" | 186 |

| 39 | S.105 | High plain | Manacacías | 21 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°26´16.19" | 3°30´29.27" | 186 |

| 40 | S.107 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°26´16.19" | 3°30´29.27" | 186 |

| 41 | S.161 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 73°2´16.25" | 3°52´50.1" | 180 |

| 42 | S.162 | High plain | Manacacías | 21 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 73°3´16.25" | 2°27´10.54" | 180 |

| 43 | S.163 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 53 | 47 | 73°3´16.25" | 2°27´10.54" | 180 |

| 44 | S.164 | High plain | Manacacías | 20 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 73°2´16.25" | 3°52´50.1" | 180 |

| 45 | S.165 | High plain | Manacacías | 21 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 73°46´16.25" | 2°4´9.7" | 180 |

| 46 | S.167 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 73°46´16.25" | 2°4´9.7" | 180 |

| 47 | S.108 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°26´16.19" | 3°30´29.27" | 186 |

| 48 | S.109 | High plain | Manacacías | 23 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°26´16.19" | 3°30´29.27" | 186 |

| 49 | S.110 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°33´16.19" | 3°32´19.4" | 186 |

| 50 | S.168 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 73°46´16.25" | 2°4´9.7" | 180 |

| 51 | S.169 | High plain | Manacacías | 23 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 73°46´16.25" | 2°4´9.7" | 180 |

| 52 | S.170 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 73°12´16.25" | 2°28´6.28" | 180 |

| 53 | S.160 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 73°2´16.24" | 3°52´50.1" | 216 |

| 54 | S.122 | High plain | Manacacías | 20 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´20.47" | 169 |

| 55 | S.124 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´20.47" | 169 |

| 56 | S.121 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´20.47" | 169 |

| 57 | S.126 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´20.47" | 169 |

| 58 | S.128 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´20.47" | 169 |

| 59 | S.129 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´17.2" | 169 |

| 60 | S.123 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´20.47" | 169 |

| 61 | S.152 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°28´16.24" | 3°35´24.4" | 216 |

| 62 | S.154 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°21´16.24" | 2°38´31.37" | 216 |

| 63 | S.157 | High plain | Manacacías | 6 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°21´16.24" | 2°38´31.37" | 216 |

| 64 | S.158 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°25´16.24" | 2°30´55.39" | 216 |

| 65 | S.153 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°21´16.24" | 2°38´31.37" | 216 |

| 66 | S.151 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°28´16.24" | 3°35´23.7" | 216 |

| 67 | S.155 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°21´16.24" | 2°38´31.37" | 216 |

| 68 | S.156 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°21´16.24" | 2°38´31.37" | 216 |

| 69 | S.125 | High plain | Manacacías | 21 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´20.47" | 169 |

| 70 | S.127 | High plain | Manacacías | 19 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´20.47" | 169 |

| 71 | S.159 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 100 | 0 | 72°25´16.24" | 2°30´55.39" | 216 |

| 72 | S.41 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 90 | 10 | 72°23´16.13" | 3°27´19.08" | 164 |

| 73 | S.42 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 94 | 6 | 72°23´16.13" | 3°27´19.08" | 164 |

| 74 | S.43 | High plain | Manacacías | 18 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 91 | 9 | 72°23´16.13" | 3°27´19.08" | 164 |

| 75 | S.44 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°23´16.13" | 3°27´19.08" | 164 |

| 76 | S.45 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°23´16.13" | 3°27´19.08" | 164 |

| 77 | S.46 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 86 | 14 | 72°23´16.13" | 3°27´19.08" | 169 |

| 78 | S.49 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 89 | 11 | 72°23´16.13" | 3°27´19.08" | 169 |

| 79 | S.51 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 67 | 33 | 72°23´16.14" | 3°27´18.14" | 180 |

| 80 | S.52 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 72 | 28 | 72°23´16.14" | 3°27´18.14" | 180 |

| 81 | S.54 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 87 | 13 | 72°23´16.14" | 3°27´18.14" | 180 |

| 82 | S.55 | High plain | Manacacías | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 85 | 15 | 72°23´16.14" | 3°27´18.14" | 180 |

| 83 | S.58 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 90 | 10 | 72°23´16.14" | 3°27´18.14" | 183 |

| 84 | S.59 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 91 | 9 | 72°23´16.14" | 3°27´18.14" | 183 |

| 85 | S.31 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 62 | 38 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 164 |

| 86 | S.36 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 81 | 19 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 169 |

| 87 | S.38 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 169 |

| 88 | S.40 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 91 | 9 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 169 |

| 89 | S.86 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 173 |

| 90 | S.111 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°36´16.2" | 3°32´18.7" | 186 |

| 91 | S.113 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°36´16.2" | 3°34´28.93" | 186 |

| 92 | S.116 | High plain | Manacacías | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°28´16.2" | 3°37´34.8" | 186 |

| 93 | S.117 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 85 | 15 | 72°28´16.2" | 3°38´13.3" | 186 |

| 94 | S.143 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°28´16.23" | 3°35´40.6" | 197 |

| 95 | S.118 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 94 | 6 | 72°29´16.2" | 3°38´24.5" | 186 |

| 96 | S.119 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°23´16.2" | 3°29´20.47" | 186 |

| 97 | S.120 | High plain | Manacacías | 25 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 81 | 19 | 72°23´16.2" | 3°29´20.47" | 186 |

| 98 | S.149 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 88 | 12 | 72°35´16.23" | 3°35´45.6" | 197 |

| 99 | S.130 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 72°23´16.21" | 3°29´17.2" | 169 |

| 100 | S.50 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°23´16.13" | 3°27´19.08" | 169 |

| 101 | S.57 | High plain | Manacacías | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°23´16.14" | 3°27´18.14" | 183 |

| 102 | S.79 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 84 | 16 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 199 |

| 103 | S.70 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 88 | 12 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 200 |

| 104 | S.72 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 200 |

| 105 | S.74 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 94 | 6 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 200 |

| 106 | S.76 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 199 |

| 107 | S.80 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 90 | 10 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 167 |

| 108 | S.138 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°23´16.22" | 3°29´17.2" | 177 |

| 109 | S.139 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 80 | 20 | 72°36´16.22" | 3°34´18.4" | 177 |

| 110 | S.136 | High plain | Manacacías | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°23´16.22" | 3°29´17.2" | 177 |

| 111 | S.132 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 93 | 7 | 72°23´16.22" | 3°29´17.2" | 177 |

| 112 | S.133 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°23´16.22" | 3°29´17.2" | 177 |

| 113 | S.134 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 80 | 20 | 72°23´16.22" | 3°29´17.2" | 177 |

| 114 | S.135 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°23´16.22" | 3°29´17.2" | 177 |

| 115 | S.137 | High plain | Manacacías | 17 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 94 | 6 | 72°23´16.22" | 3°29´17.2" | 177 |

| 116 | S.77 | High plain | Manacacías | 12 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°26´16.16" | 3°30´29.27" | 199 |

| 117 | S.141 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°36´16.23" | 3°34´20.7" | 197 |

| 118 | S.142 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°28´16.23" | 3°33´42.5" | 197 |

| 119 | S.144 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°28´16.23" | 3°35´38.9" | 197 |

| 120 | S.20 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°27´16.1" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 121 | S.85 | High plain | Manacacías | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 90 | 10 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 173 |

| 122 | S.82 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 94 | 6 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 167 |

| 123 | S.87 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 173 |

| 124 | S.89 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 91 | 9 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 173 |

| 125 | S.98 | High plain | Manacacías | 6 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 87 | 13 | 72°23´16.18" | 3°29´17.2" | 170 |

| 126 | S.16 | High plain | Manacacías | 6 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 80 | 20 | 72°27´16.1" | 3°29´52.3" | 172 |

| 127 | S.32 | High plain | Manacacías | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 164 |

| 128 | S.35 | High plain | Manacacías | 5 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 164 |

| 129 | S.37 | High plain | Manacacías | 5 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 169 |

| 130 | S.81 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 87 | 13 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 167 |

| 131 | S.90 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 95 | 5 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 174 |

| 132 | S.145 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 93 | 7 | 72°28´16.23" | 3°35´34.6" | 197 |

| 133 | S.146 | High plain | Manacacías | 13 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°28´16.23" | 3°35´37" | 197 |

| 134 | S.147 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 99 | 1 | 72°33´16.23" | 3°31´44" | 197 |

| 135 | S.148 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°35´16.23" | 3°35´46.3" | 197 |

| 136 | S.150 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 85 | 15 | 72°35´16.23" | 3°35´46.3" | 197 |

| 137 | S.178 | High plain | Manacacías | 5 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°33´16.26" | 3°32´19.4" | 234 |

| 138 | S.183 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 82 | 18 | 72°36´16.27" | 3°32´18.7" | 230 |

| 139 | S.184 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 92 | 8 | 72°28´16.27" | 3°37´34.8" | 201 |

| 140 | S.185 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 88 | 12 | 72°28´16.27" | 3°38´13.3" | 208 |

| 141 | S.188 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 85 | 15 | 72°36´16.27" | 3°32´18.6" | 222 |

| 142 | S.33 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 96 | 4 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 164 |

| 143 | S.93 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 85 | 15 | 72°23´16.18" | 3°29´17.2" | 174 |

| 144 | S.114 | High plain | Manacacías | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 91 | 9 | 72°36´16.2" | 3°34´30.47" | 186 |

| 145 | S.63 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 183 |

| 146 | S.68 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 84 | 16 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 180 |

| 147 | S.69 | High plain | Manacacías | 6 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 85 | 15 | 72°26´16.15" | 3°30´35.75" | 180 |

| 148 | S.181 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 89 | 11 | 72°36´16.27" | 3°34´16.1" | 225 |

| 149 | S.191 | High plain | Manacacías | 3 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 82 | 18 | 72°32´16.28" | 3°41´11.4" | 200 |

| 150 | S.83 | High plain | Manacacías | 6 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 87 | 13 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 167 |

| 151 | S.84 | High plain | Manacacías | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 93 | 7 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 167 |

| 152 | S.34 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 74 | 26 | 72°24´16.12" | 3°26´45.02" | 164 |

| 153 | S.88 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 90 | 10 | 72°23´16.17" | 3°29´20.47" | 173 |

| 154 | S.131 | High plain | Manacacías | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 86 | 14 | 72°23´16.22" | 3°29´17.2" | 177 |

| 155 | S.171 | High plain | Manacacías | 5 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 72°35´16.26" | 3°35´48.88" | 177 |

| 156 | S.189 | High plain | Manacacías | 6 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 71 | 29 | 72°34´16.27" | 3°41´59.3" | 230 |

| 157 | S.175 | High plain | Manacacías | 3 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 80 | 20 | 72°36´16.26" | 3°34´30.47" | 177 |

| 158 | S.182 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 88 | 12 | 72°36´16.27" | 3°34´20.7" | 235 |

| 159 | S.172 | High plain | Manacacías | 7 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 73 | 27 | 72°35´16.26" | 3°50´51.4" | 176 |

| 160 | S.179 | High plain | Manacacías | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 89 | 11 | 72°36´16.26" | 3°34´17.5" | 225 |

| 161 | S.177 | High plain | Manacacías | 15 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 70 | 30 | 72°36´16.26" | 3°34´18.4" | 233 |

| 162 | S.180 | High plain | Manacacías | 6 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 69 | 31 | 72°36´16.26" | 3°34´16.8" | 224 |

| 163 | S.140 | High plain | Manacacías | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 87 | 13 | 72°36´16.22" | 3°34´16.1" | 177 |

| 164 | S.Ar.21 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 69° 54' 28.8'' | 6° 12' 40.03'' | 107 |

| 165 | S.Ar.22 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 16 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 82 | 18 | 69° 54' 28.47'' | 6° 12' 39.99'' | 109 |

| 166 | S.Ar.27 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 12 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 75 | 25 | 69° 54' 27.28'' | 6° 12' 37.47'' | 114 |

| 167 | S.Ar.28 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 15 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 73 | 27 | 69° 54' 28.07'' | 6° 12' 36.97'' | 116 |

| 168 | S.Ar.31 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 83 | 17 | 69° 53' 21.87'' | 6° 13' 3.28'' | 107 |

| 169 | S.Ar.24 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 18 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 90 | 10 | 69° 54' 29.08'' | 6° 12' 39.16'' | 113 |

| 170 | S.Ar.70 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 16 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 98 | 2 | 70° 25' 38.17'' | 6° 23' 37.93'' | 106 |

| 171 | S.Ar.29 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 12 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 76 | 24 | 69° 54' 27.57'' | 6° 12' 36.79'' | 117 |

| 172 | S.Ar.23 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 21 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 98 | 2 | 69° 54' 28.18'' | 6° 12' 39.6'' | 111 |

| 173 | S.Ar.25 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 75 | 25 | 69° 54' 28.58'' | 6° 12' 38.7'' | 110 |

| 174 | S.Ar.32 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 18 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 69° 53' 21.19'' | 6° 13' 3.79'' | 107 |

| 175 | S.Ar.33 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 10 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 71 | 29 | 69° 53' 20.97'' | 6° 13' 4.08'' | 107 |

| 176 | S.Ar.34 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 86 | 14 | 69° 53' 20.86'' | 6° 13' 4.69'' | 107 |

| 177 | S.Ar.36 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 12 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 94 | 6 | 69° 53' 21.3'' | 6° 13' 5.7'' | 108 |

| 178 | S.Ar.38 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 12 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 87 | 13 | 69° 53' 20.79'' | 6° 13' 5.98'' | 108 |

| 179 | S.Ar.39 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 13 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 94 | 6 | 69° 53' 20.18'' | 6° 13' 6.27'' | 108 |

| 180 | S.Ar.4 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 52 | 48 | 69° 54' 56.7'' | 6° 11' 39.69'' | 103 |

| 181 | S.Ar.40 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 16 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 93 | 7 | 69° 53' 20.39'' | 6° 13' 6.59'' | 108 |

| 182 | S.Ar.35 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 10 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 77 | 23 | 69° 53' 20.68'' | 6° 13' 5.19'' | 107 |

| 183 | S.Ar.37 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 81 | 19 | 69° 53' 21.48'' | 6° 13' 5.88'' | 108 |

| 184 | S.Ar.51 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 6 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 49 | 51 | 69° 52' 35.18'' | 6° 13' 21.46'' | 100 |

| 185 | S.Ar.83 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 94 | 6 | 70° 51' 20.01'' | 6° 23' 5.31'' | 126 |

| 186 | S.Ar.54 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 69 | 31 | 69° 52' 25.89'' | 6° 13' 22.79'' | 100 |

| 187 | S.Ar.55 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 12 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 67 | 33 | 69° 52' 23.19'' | 6° 13' 21.97'' | 98 |

| 188 | S.Ar.56 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 58 | 42 | 69° 52' 21.97'' | 6° 13' 23.48'' | 98 |

| 189 | S.Ar.57 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 59 | 41 | 69° 52' 20.38'' | 6° 13' 23.7'' | 98 |

| 190 | S.Ar.59 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 85 | 15 | 69° 51' 58.49'' | 6° 13' 23.88'' | 99 |

| 191 | S.Ar.6 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 7 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 23 | 77 | 69° 54' 55.97'' | 6° 11' 40.27'' | 104 |

| 192 | S.Ar.10 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 57 | 43 | 69° 54' 54.39'' | 6° 11' 41.67'' | 106 |

| 193 | S.Ar.18 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 8 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 69° 53' 15.28'' | 6° 12' 15.76'' | 108 |

| 194 | S.Ar.3 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 35 | 65 | 69° 54' 56.98'' | 6° 11' 39.3'' | 103 |

| 195 | S.Ar.71 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 28 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 94 | 6 | 70° 45' 7.01'' | 6° 24' 20.33'' | 155 |

| 196 | S.Ar.72 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 33 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 97 | 3 | 70° 45' 7.92'' | 6° 24' 20.44'' | 115 |

| 197 | S.Ar.8 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 51 | 49 | 69° 54' 55.29'' | 6° 11' 40.99'' | 105 |

| 198 | S.Ar.14 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 8 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 49 | 51 | 69° 53' 13.99'' | 6° 12' 15.47'' | 106 |

| 199 | S.Ar.17 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 10 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 63 | 37 | 69° 53' 15'' | 6° 12' 15.87'' | 106 |

| 200 | S.Ar.2 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 10 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 71 | 29 | 69° 54' 57.27'' | 6° 11' 38.97'' | 102 |

| 201 | S.Ar.5 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 75 | 25 | 69° 54' 56.26'' | 6° 11' 39.98'' | 104 |

| 202 | S.Ar.13 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 49 | 51 | 69° 53' 13.48'' | 6° 12' 15.58'' | 108 |

| 203 | S.Ar.7 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 10 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 52 | 48 | 69° 54' 55.69'' | 6° 11' 40.66'' | 105 |

| 204 | S.Ar.9 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 95 | 5 | 69° 54' 54.97'' | 6° 11' 41.27'' | 106 |

| 205 | S.Ar.47 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 89 | 11 | 69° 53' 4.09'' | 6° 13' 17.18'' | 102 |

| 206 | S.Ar.73 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 16 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 90 | 10 | 70° 48' 39.24'' | 6° 23' 49.7'' | 119 |

| 207 | S.Ar.80 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 18 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 91 | 9 | 70° 49' 57.57'' | 6° 21' 43.16'' | 126 |

| 208 | S.Ar.84 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 16 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 89 | 11 | 70° 42' 46.51'' | 6° 25' 48.54'' | 119 |

| 209 | S.Ar.87 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 19 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 71 | 29 | 70° 43' 1.52'' | 6° 26' 18.09'' | 115 |

| 210 | S.Ar.89 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 93 | 7 | 70° 43' 11.42'' | 6° 26' 11.07'' | 118 |

| 211 | S.Ar.90 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 19 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 79 | 21 | 70° 50' 37.93'' | 6° 22' 59.7'' | 123 |

| 212 | S.Ar.92 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 15 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 79 | 21 | 70° 49' 29.92'' | 6° 23' 0.13'' | 125 |

| 213 | S.Ar.94 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 6 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 75 | 25 | 70° 49' 15.34'' | 6° 23' 3.91'' | 127 |

| 214 | S.Ar.95 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 19 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 69 | 31 | 70° 49' 2.85'' | 6° 23' 4.81'' | 124 |

| 215 | S.Ar.96 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 69 | 31 | 70° 49' 35.14'' | 6° 22' 59.41'' | 121 |

| 216 | S.Ar. 49 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 16 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 97 | 3 | 69° 53' 0.67'' | 6° 13' 19.66'' | 101 |

| 217 | S.Ar. 50 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 75 | 25 | 69° 52' 59.7'' | 6° 13' 20.27'' | 101 |

| 218 | S.Ar. 16 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 8 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 64 | 36 | 69° 53' 14.67'' | 6° 12' 15.47'' | 106 |

| 219 | S.Ar. 11 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 67 | 33 | 69° 53' 12.19'' | 6° 12' 15.76'' | 109 |

| 220 | S.Ar. 1 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 10 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 92 | 8 | 69° 54' 57.49'' | 6° 11' 38.79'' | 102 |

| 221 | S.Ar. 12 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 86 | 14 | 69° 53' 12.98'' | 6° 12' 15.87'' | 109 |

| 222 | S.Ar. 15 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 50 | 50 | 69° 53' 14.49'' | 6° 12' 15.37'' | 108 |

| 223 | S.Ar. 19 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 7 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 48 | 52 | 69° 53' 15.89'' | 6° 12' 15.58'' | 105 |

| 224 | S.Ar. 20 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 15 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 61 | 39 | 69° 53' 16.36'' | 6° 12' 15.69'' | 107 |

| 225 | S.Ar. 42 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 7 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 45 | 55 | 69° 53' 9.09'' | 6° 13' 12.17'' | 107 |

| 226 | S.Ar. 41 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 12 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 90 | 10 | 69° 53' 10.06'' | 6° 13' 9.19'' | 107 |

| 227 | S.Ar. 43 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 95 | 5 | 69° 53' 7.29'' | 6° 13' 15.67'' | 106 |

| 228 | S.Ar. 44 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 13 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 69° 53' 6.89'' | 6° 13' 15.38'' | 106 |

| 229 | S.Ar. 45 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 15 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 69° 53' 5.67'' | 6° 13' 17.86'' | 102 |

| 230 | S.Ar. 48 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 17 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 69° 53' 1.89'' | 6° 13' 19.09'' | 101 |

| 231 | S.Ar. 68 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 38 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 70° 36' 44.1'' | 6° 59' 3.69'' | 107 |

| 232 | S.Ar. 85 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 17 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 90 | 10 | 70° 42' 44.82'' | 6° 25' 58.83'' | 118 |

| 233 | S.Ar. 46 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 13 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 72 | 28 | 69° 53' 4.38'' | 6° 13' 18.58'' | 102 |

| 234 | S.Ar. 52 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 10 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 62 | 38 | 69° 52' 27.37'' | 6° 13' 22.08'' | 100 |

| 235 | S.Ar. 53 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 12 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 73 | 27 | 69° 52' 26.29'' | 6° 13' 21.89'' | 100 |

| 236 | S.Ar. 58 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 12 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 84 | 16 | 69° 52' 19.99'' | 6° 13' 23.98'' | 98 |

| 237 | S.Ar. 60 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 57 | 43 | 69° 51' 56.19'' | 6° 13' 24.27'' | 97 |

| 238 | S.Ar. 77 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 98 | 2 | 70° 49' 15.99'' | 6° 20' 7.29'' | 127 |

| 239 | S.Ar. 79 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 13 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 70° 50' 32.06'' | 6° 23' 3.33'' | 124 |

| 240 | S.Ar. 78 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 16 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 96 | 4 | 70° 50' 30.98'' | 6° 23' 0.92'' | 124 |

| 241 | S.Ar. 69 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 9 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 82 | 18 | 70° 25' 16.42'' | 6° 23' 49.95'' | 106 |

| 242 | S.Ar. 76 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 10 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 97 | 3 | 70° 50' 22.77'' | 6° 22' 31.65'' | 132 |

| 243 | S.Ar. 81 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 18 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 70° 50' 30.91'' | 6° 22' 3.57'' | 123 |

| 244 | S.Ar. 88 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 13 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 70° 43' 6.24'' | 6° 26' 20.43'' | 115 |

| 245 | S.Ar. 93 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 98 | 2 | 70° 49' 23.91'' | 6° 23' 0.92'' | 124 |

| 246 | S.Ar. 62 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 17 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 94 | 6 | 70° 41' 37.78'' | 7° 3' 34.59'' | 126 |

| 247 | S.Ar. 66 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 7 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 96 | 4 | 70° 43' 5.91'' | 7° 1' 31'' | 101 |

| 248 | S.Ar. 65 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 6 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 99 | 1 | 70° 41' 49.77'' | 7° 3' 42.08'' | 102 |

| 249 | S.Ar. 74 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 19 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 63 | 37 | 70° 49' 39.39'' | 6° 23' 32.2'' | 116 |

| 250 | S.Ar. 61 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 17 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 70 | 30 | 70° 38' 46.89'' | 7° 3' 57.67'' | 123 |

| 251 | S.Ar. 64 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 18 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 70° 34' 56.06'' | 7° 4' 26.18'' | 103 |

| 252 | S.Ar. 63 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 98 | 2 | 70° 25' 37.66'' | 6° 21' 32.18'' | 100 |

| 253 | S.Ar. 82 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 14 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 99 | 1 | 70° 50' 6.07'' | 6° 22' 23.73'' | 122 |

| 254 | S.Ar. 86 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 11 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 29 | 71 | 70° 42' 40.89'' | 6° 25' 22.4'' | 118 |

| 255 | S.Ar. 91 | Alluvial plain | Arauca | 13 | 3,6-5,5 | Clay alluvium | <2000 | <2 | 99 | 1 | 70° 50' 36.67'' | 6° 21' 43.73'' | 124 |

| 256 | CAS.33 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 4 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 80 | 20 | 71º25’38,9’’ | 5º32’29,3’’ | 149 |

| 257 | CAS.58 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 8 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 90 | 10 | 71º25’35,6’’ | 5º32’30,1’’ | 148 |

| 258 | CAS.35 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 4 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 75 | 25 | 71º26’24,7’’ | 5º31’46,0’’ | 157 |

| 259 | CAS.36 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 4 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 75 | 25 | 71º26’23,6’’ | 5º31’49,4’’ | 154 |

| 260 | CAS.34 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 4 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 75 | 25 | 71º26’26,4’’ | 5º31’44,9’’ | 153 |

| 261 | CAS.45 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 16 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 97 | 3 | 71º26’03,2’’ | 5º31’34,2’’ | 149 |

| 262 | CAS.59 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 16 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71º25’36,8’’ | 5º32’29,9’’ | 151 |

| 263 | CAS.38 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 6 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 70 | 30 | 71º42’10,1’’ | 5º25’51,9’’ | 165 |

| 264 | CAS.46 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 6 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71º42’05,1’’ | 5º25’49,8’’ | 164 |

| 265 | CAS.55 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 12 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71° 3' 48,521" | 5° 21' 34,307" | 138 |

| 266 | CAS.57 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 8 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 95 | 5 | 71° 3' 44,396" | 5° 21' 33,200" | 134 |

| 267 | CAS.54 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 9 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71° 1' 45,745" | 5° 21' 42,960" | 118 |

| 268 | CAS.48 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 26 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 99 | 1 | 71º42’15,8’’ | 5º26’51,2’’ | 174 |

| 269 | CAS.49 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 15 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71º42’17,1’’ | 5º26’52,6’’ | 172 |

| 270 | CAS.39 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 15 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 95 | 5 | 71º42’06,4’’ | 5º25’47,7’’ | 165 |

| 271 | CAS.50 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 13 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71º42’27,3’’ | 5º26’45,4’’ | 171 |

| 272 | CAS.42 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 5 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 95 | 5 | 71º25’54,8’’ | 5º31’32,3’’ | 155 |

| 273 | CAS.41 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 15 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71º26’14,9’’ | 5º31’34,5 | 154 |

| 274 | CAS.44 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 6 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 85 | 15 | 71º26’01,9’’ | 5º31’33,3’’ | 146 |

| 275 | CAS.40 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 7 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 72º05’25,4’’ | 5º50’34,5’’ | 495 |

| 276 | CAS.47 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 6 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 95 | 5 | 70º05’25,1’’ | 5º50’33,2’’ | 500 |

| 277 | CAS.52 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 16 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71º37’49,9’’ | 5º23’45,2’’ | 165 |

| 278 | CAS.51 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 8 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71º37’52,2’’ | 5º23’44,7’’ | 168 |

| 279 | CAS.37 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 4 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 60 | 40 | 71º42’03,6’’ | 5º25’50,8’’ | 165 |

| 280 | CAS.32 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 9 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71° 24' 34,837" | 5° 27' 2,614" | 145 |

| 281 | CAS.53 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 13 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71° 24' 35,030" | 5° 26' 59,294" | 177 |

| 282 | CAS.43 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 14 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 100 | 0 | 71° 3' 14,061" | 5° 20' 58,366" | 121 |

| 283 | CAS.56 | Alluvial plain | Casanare | 5 | 4,3-6,5 | Sandy alluvium | 2000-2100 | <2 | 95 | 5 | 71° 3' 46,735" | 5° 21' 33,396" | 132 |

| 284 | Met_ 10 | High plain | río Meta | 9 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 67° 30' 18,89'' | 06° 13' 01.01'' | 82 |

| 285 | Met_ 6 | High plain | río Meta | 16 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 69° 50' 26.6'' | 06° 00' 26.2'' | 95 |

| 286 | Met_ 9 | High plain | río Meta | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 85 | 15 | 71° 19' 32.7'' | 04° 47' 53.7'' | 140 |

| 287 | Met_ 14 | High plain | río Meta | 8 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 93 | 7 | 67° 30' 18,25'' | 06° 13' 02.10'' | 80 |

| 288 | Met_ 1 | High plain | río Meta | 11 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 68° 06' 33.3'' | 06° 13' 07.1'' | 65 |

| 289 | Met_ 29 | High plain | río Meta | 5 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 97 | 3 | 68° 06' 32.9'' | 06° 13' 07.7'' | 65 |

| 290 | Met_ 5 | High plain | río Meta | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 68° 06' 31.2'' | 06° 13' 06.7'' | 70 |

| 291 | Met_ 3 | High plain | río Meta | 14 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 98 | 2 | 68° 32' 14.9'' | 06° 08' 27.2'' | 102 |

| 292 | Met_ 4 | High plain | río Meta | 10 | 4,0-5,5 | Clay alluvium | >2300 | >2 | 93 | 7 | 68° 49' 40.6'' | 06° 09' 51.8'' | 74 |

References

- FAO. Reconocimiento edafológico de los Llanos Orientales, Colombia: La vegetación natural y la ganadería, Sección Primera, Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación FAO: Roma, Italia, 1965; Volume 3, 156.

- Van Donselaar, J. An ecological and phytogeographic study of northern Surinam savannas. Wentia 1965, 14, 1–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susach, F. Caracterización y clasificación fitosociológica de la vegetación de sabanas del sector oriental de los Llanos Centrales Bajos Venezolanos. Acta Biol. Venez. 1989, 12, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Galán de Mera, A. Vegetación de las sabanas de los llanos de Venezuela. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica: La región de la Orinoquia de Colombia; Rangel-Ch., J.O., Ed.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 447–482. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Ch., J.O.; Minorta-Cely, V. Los tipos de vegetación de la Orinoquia colombiana. In: Colombia Diversidad Biótica: La región de la Orinoquia de Colombia; Rangel-Ch., J.O., Ed. Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 533–612.

- San José, J.J.; Montes, R.; Mazorra, M. The nature of savanna heterogeneity in the Orinoco Basin. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 1998, 7, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Beradi, A. World Savannas: Ecology and Human Use; Routledge: London, United Kingdom, 2000; p. 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behling, H.; Hooghiemstra, H. Chapter 18, Neotropical savanna environments in space and time: Late Quaternary interhemispheric comparisons; Interhemispheric Climate Linkages: 2001; pp. 307–323. [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Z. Vegetation–environment relationships and classification of the seasonal savannas in Venezuela. Flora 2005, 200(1), 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerling, D.J.; Osborne, C.P. The origin of the savanna biome. Global Change Biology 2006, 12, 2023–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, O.; de Stefano, R.D.; Aymard, G.; Riina, R. Flora and vegetation of the venezuelan Llanos: a review. In Neotropical Savannas and Seasonally Dry Forests: Plant Diversity, Biogeography, and Conservation; Pennington, R.T., Ratter, J.A., Lewins, G.P., Eds.; Bosa Roca: USA, 2006; pp. 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rull, V.; Vegas-Villarúbia, T.; Montoya, E. The Neotropical Gran Sabana region: palaeoecology and conservation. The Holocene 2016, 26, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Françoso, R.D.; Haidar, R.F.; Machado, R.B. Tree species of South America central savanna: endemism, marginal areas and the relationship with other biomes. Acta Botanica Brasilica 2016, 30, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghetti, F.; Barbosa, E.; Ribeiro, L.; Ribeiro, J.; Maciel, E.; Walter, B. Fitogeografia das savanas sul-americanas. Heringeriana 2023, 17, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlière, F. M. Hadley. Present‐day savannas: an overview. In Tropical Savannas; Bourlière, F., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1983; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, G. 1983. The savannas of tropical America. In Tropical Savannas; Bourlière, F., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1983; pp. 245–288. [Google Scholar]

- Goodland, R.J. South American savannas: comparative studies Llanos & Guyana; McGill University Savanna Research Project Series 5: Montreal, Canada, 1966; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Goodland, R.; Pollard, R. The Brazilian Cerrado vegetation: a fertility gradient. J. Ecol. 1973, 61, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.S.; Cox, F.R. Cerrado vegetation in Brazil: an edaphic gradient. Agron. J. 1977, 69, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.M.; Reys, P.; Selgado P., D.; Leônidas de Sá, J.; Oliveira da Silva, P.; Moraes Santos, T.; Guimarães Silva, F. Relationship between Edaphic Factors and Vegetation in Savannas of the Brazilian Midwest Region. R. Bras. Ci. Solo 2015, 39, 821–829. [Google Scholar]

- Menegat, H.; Silvério, D.V.; Mews, H.A.; Colli, G.R.; Abadia, A.C.; Maracahipes-Santos, L.; Gonçalves, L.A.; Martins, J.; Lenza, E. Effects of environmental conditions and space on species turnover for three plant functional groups in Brazilian savannas. J. Plant Ecol. 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, R. Plant communities of a savanna in northern Bolivia: I. Seasonally flooded grassland and gallery forest. Phytocoenologia 1989, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, R. Plant communities of a savanna in northern Bolivia: II. Palm swamps, dry grassland, and shrubland. Phytocoenologia 1990, 18, 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, E.; Motta, N. Metabolism and distribution of grasses in tropical flooded savannas in Venezuela. J. Tropical Ecology 1990, 6, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, G.; Monasterio, M. Studies on the savanna vegetation of the Venezuelan Llanos. I. The use of association analysis. J. Ecol. 1969, 57, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, P.; Medina, E.; Menaut, J.C.; Solbrig, O.T.; Swift, M.; Walker, B. Responses of savannas to stress and disturbance. Biol. Int. 1986, (Special Issue 10. International Union of Biological Sciences, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, G.; Pinillos, M. Patterns and processes in a seasonally flooded tropical plain: the Apure Llanos, Venezuela. Journal of Biogeography 2001, 28, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, G.; Pinillos, M.; Pereira da Silva, M.; Acevedo, D. Effects of soil water regime and grazing on vegetation diversity and production in a hyperseasonal savanna in the Apure Llanos, Venezuela. J. Tropical Ecology 2004, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Moreno, E.; Naranjo, M.E.; Acevedo, D. Direct and indirect vegetation environment relationship in the flooded savanna, Venezuela. Ecotropicos 2004, 17, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Minorta-Cely, V. ; Rangel-CH., J.O.; Castro-L., F.; Aymard, G. La Vegetación de La Serranía de Manacacías (Meta) Orinoquia colombiana. In: Colombia Diversidad Biótica. La región de la Serranía de Manacacías (Meta) Orinoquia colombiana; Rangel-Ch., J.O., Andrade-C., G., Jarro-F., C., Santos-C. G., Eds.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Parques Nacionales Naturales: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2019a; Volume 17, pp. 155-234.

- Minorta-Cely, V. ; Rangel-CH., J.O.; Castro-L., F.; Mijares, F. La Vegetación del territorio, sabanas y Humedales de Arauca, Colombia. In: Colombia Diversidad Biótica. Territorio sabanas y humedales de Arauca (Colombia); Rangel-Ch. J.O., Andrade-C. G., Jarro-F. C., Santos-C. G., Eds.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2019b; Volume 20, pp. 279-358.

- Minorta-Cely, V. La vegetación de la Orinoquia colombiana: riqueza, diversidad y conservación. PhD Thesis, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales-Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, J.S. The savanna vegetation of Northern South America. Ecol. Monogr. 1953, 23, 149–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosen, D. División fisiográfica de los Llanos Orientales. Rev. Nac. Agric. 1963, 55, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goosen, D. Geomorfología de los Llanos Orientales. Rev. Acad. Col. Ci. Ex. Fís. Nat. 1964, 12, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Goosen, D. Physiography And Soils of the Llanos Orientäles, Colombia, Publicaties van het Fysisch-Geografisch en Bodemkundig Laboratorium van de Universiteit van Amsterdam: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1971; Volume 20, pp. 186-198.

- Blydenstein, J. La sabana de Trachypogon del alto llano. Bol. Soc. Venez. Ci. Nat. 1962, 102, 139–206. [Google Scholar]

- Blydenstein, J. Tropical savanna vegetation of the llanos of Colombia. Ecology 1967, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincelli, P.C. Estudio de la vegetación del Territorio Faunístico “El Tuparro”. Cespedesia 1981, 10, 7–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, L.A. Las tierras de la Orinoquia, capacidad de uso actual y futuro. Fundación Universidad de Bogotá “Jorge Tadeo Lozano”. Escuela de postgrado: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 1985; 97 pp.

- Rangel-CH., J.O.; Sánchez-C., H.; Lowy-C., P.; Aguilar-P., M.; Castillo, A. Región de la Orinoquia. In: Colombia Diversidad Biótica; Rangel-Ch., J.O., Ed.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 1995; Volume 1, pp. 239–254.

- Rangel-CH. , J.O. Flora Orinoquense. In Colombia Orinoco; Domínguez, C., Ed.; FEN-Colombia: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 1998; pp. 104–130. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC). Paisajes fisiográficos de Orinoquia-Amazonia (ORAM) Colombia. IGAC: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 1999; 373 pp.

- Rippstein, G. , E., Escobar, G., & Grollier, C. Condiciones naturales de la sabana. In Agroecología y diversidad de las sabanas en los Llanos Orientales de Colombia; Rippstein, G., Escobar, G., Motta, F., Eds.; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical CIAT: Colombia, 2001; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, H. Capítulo 3, Vegetación. In Caracterización biológica del Parque Nacional Natural El Tuparro (Sector Noreste), Vichada, Colombia; Villarreal, H., Maldonado, J., Eds.; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander Von Humboldt: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Fernandez, C.; Peñuela-Recio, L.F. Castro-Lima. Estado del conocimiento de los ecosistemas de las sabanas inundables en la Orinoquia Colombiana. Orinoquia 2015, 19, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasnó, D.A. Diversidad y riqueza de graminoides (Poaceae y Cyperaceae) en bancos, bajos y esteros de sabanas de Arauca (Orinoquia colombiana). Undergraduate thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2017.

- Vera, A. Flora y vegetación acuática en áreas de la Orinoquia colombiana. Master thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2017.

- Hubbell, S.P. Neutral theory in community ecology and the hypothesis of functional equivalence. Funct. Ecol. 2005, 19, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wen, Z. Periodical Progress in Ecophysiology and Ecology of Grassland. Plants 2023, 12, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ye, M.; Li, Y.; Zeng, G.; Chen, W.; Pan, X.; He, Q.; Zhang, X. An Investigation of the Magnitude of the Role of Different Plant Species in Grassland Communities on Species Diversity, China. Plants 2024, 13, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Liu, D.; Mo, S.; Li, Q.; Meng, J.; Huang, Q. Assessment of Phenological Dynamics of Different Vegetation Types and Their Environmental Drivers with Near-Surface Remote Sensing: A Case Study on the Loess Plateau of China. Plants 2024, 13, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Arroyo, G.E.; Canché-Solís, R.E.; Morón-Ríos, A.; González-Espinosa, M.; Méndez-Toribio, M. Unraveling the Relative Contributions of Deterministic and Stochastic Processes in Shaping Species Community Assembly in a Floodplain and Shallow Hillslope System. Forests 2024, 15, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Yu, M.; Chen, X.; Zhu, C.; Shang, J.; Gao, J. Climate Factors Influence Above- and Belowground Biomass Allocations in Alpine Meadows and Desert Steppes through Alterations in Soil Nutrient Availability. Plants 2024, 13, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholizadeh, H.; Gamon, J.A.; Zygielbaum, A.I.; Wang, R.; Schweiger, A.K.; Cavender-Bares, J. Remote sensing of biodiversity: Soil correction and data dimension reduction methods improve assessment of α-diversity (species richness) in prairie ecosystems. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2018, 206, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Fan, M.; Bai, L.; Sang, W.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Z.; Tao, Z. Identification of the best hyperspectral indices in estimating plant species richness in sandy grasslands. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csontos, P.; Tamás, J.; Kovács, Z.; Schellenberger, J.; Penksza, K.; Szili-Kovács, T.; Kalapos, T. Vegetation Dynamics in a Loess Grassland: Plant Traits Indicate Stability Based on Species Presence, but Directional Change When Cover Is Considered. Plants 2022, 11, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jia, H.; Pen, M.; Liu, N.; Wei, J.; Zhou, B. Ecological Niche and Interspecific Association of Plant Communities in Alpine Desertification Grasslands: A Case Study of Qinghai Lake Basin. Plants 2022, 11, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.; Ickowicz, A.; Cesaro, J.-D.; Salgado, P.; Rayot, V.; Koldasbekova, S.; Taugourdeau, S. Improving Biodiversity Offset Schemes through the Identification of Ecosystem Services at a Landscape Level. Land 2023, 12, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdavoudi, H.; Ghorbanian, D.; Zarekia, S.; Soleiman, J.M.; Ghonchepur, M.; Sweeney, E.M.; Mastinu, A. Ecological Niche Modelling and Potential Distribution of Artemisia sieberi in the Iranian Steppe Vegetation. Land 2022, 11, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornley, R.H.; Gerard, F.F.; White, K.; Verhoef, A. Prediction of Grassland Biodiversity Using Measures of Spectral Variance: A Meta-Analytical Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, H.A.; Gianelle, D.; Scotton, M.; Rocchini, D.; Dalponte, M.; Macolino, S.; Sakowska, K.; Pornaro, C.; Vescovo, L. Potential and Limitations of Grasslands α-Diversity Prediction Using Fine-Scale Hyperspectral Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, L. La fisiografía, los suelos, la vegetación y su relación con el sistema de agricultura migratoria, en el sector norte de la Reserva Forestal Sipapo, Estado Amazonas, Venezuela. PhD thesis, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, España, 2006.

- Schargel, R.; Marvaez, P. Suelos - Estudio de los suelos y la vegetación (estructura, composición florística y diversidad) en bosques macrotérmicos no-inundables, Estado Amazonas, Venezuela. Biollania 2009, 9, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Schimper, A. F. W. Plant Geography upon a Physiological Basis, translated by Fisher, W. R.; Fischer, G. Jena 1903.

- Nix, H. A. Climate of tropical savannas. In Ecosystems of the World, Tropical Savannas; Bouliere, F., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, U.S.A, 1983; Volume 13, pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, M.D.; Nobre, C.A. A new climate-vegetation equilibrium state for tropical South America. Geophysical Research Letters 2003, 30, 21–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutyra, L.; Munger, J.; Nobre, C.; Saleska, S.; Vieira, S.U.; Wofsy, S. Climatic variability and vegetation vulnerability in Amazonia. Geophysical Research Letters 2005, 32, 24–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.M.; Que, T.; Hu, X. Analysis of the relationship between plant diversity and soil nutrients on roadside slopes in karst areas. Tianjin Agric. For. Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Ye, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Chen, W.; Zeng, G.; Che, J.; Lv, Y. Characteristics of Grassland Species Diversity and Soil Physicochemical Properties with Elevation Gradient in Burzin Forest Area. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, M.; Peña-Claros, M.; Bongers, F.; Alarcon, A.; Balcazar, J.; Chuviña, J.; Leaño, C.; Licona, J.C.; Poorter, L. Distribution patterns of tropical woody species in response to climatic and edaphic gradients. Journal of Ecology 2012, 100, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, G. The Neotropical Savannas. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1984.

- Sarmiento, G. 1996. Biodiversity and water relations in Tropical Savannas. In: Biodiversity and Savanna Ecosystem Processes. A Global Perspective. Ecological Studies; Solbrig, O.T., Medina, E., Silva, J.F., Eds.; Springer; Volume 121.

- Solbrig, O.T.; Medina, E.; Silva, J.F. Determinants of Tropical Savannas. In: Biodiversity and Savanna Ecosystem Processes. A Global Perspective, Ecological Studies; Solbrig, O.T., Medina, E., Silva, J.F., Eds.; Springer: 1996; Volume 121.

- Anadón, J.D.; Sala, O.E; Maestre, F.T. Climate change will increase savannas at the expense of forests and treeless vegetation in tropical and subtropical Americas. Journal of Ecology 2014, 102, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Guo, Y.; Luo, T.; Zhang, L. Stochastic Processes Drive Plant Community Assembly in Alpine Grassland during the Restoration Period. Diversity 2022, 14, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnai, M.; Trindade, D.P.; Thierry, M.; Kaushik, K.; Hrček, J.; Götzenberger, L. Environment and space drive the community assembly of Atlantic European grasslands: Insights from multiple facets. Journal of Biogeography 2022, 49, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G.; Davidson, A.; List, R.; Pacheco, J.; Manzano-Fischer, P.; et al. Rapid Decline of a Grassland System and Its Ecological and Conservation Implications. Plos One 2010, 5, e8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, K.; Csízi, I.; Halász, A.; Mezőszentgyörgyi, D.; Nagy, D. Monitoring the Degradation of Semi-Natural Grassland Associations under Different Land-Use Patterns. Agronomy 2024, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Quinto Canas, R.; Pinar Fuentes, J.C.; Del Rio, S.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Cano, E. Endemic Hemicryptophyte Grasslands of the High Mountains of the Caribbean. Research Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 2022, 2, 1–20. https://www.scipublications.com/journal/index.php/rjees/article/view/184.

- Liu, K.; Shao, X. Grassland Ecological Management and Utilization for Sustainability. Agronomy 2024, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Spampinato, G. Diversity and Ecological Assessment of Grasslands Habitat Types: A Case Study in the Calabria Region (Southern Italy). Land 2024, 13, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schargel, R. Aspectos Físico-Naturales. In Flora vascular de los Llanos de Venezuela, Duno de Stefano, R.; Aymard, G., Huber, O. Eds, Eds.; FUDENA-Fundación Empresas Polar- FIBV: Caracas, Venezuela, 2007; 738 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Niño, L.; Jaramillo, A.; Villamizar, V.; Rangel, O. Geomorphology, Land-Use, and Hemeroby of Foothills in Colombian Orinoquia: Classification and Correlation at a Regional Scale. Papers in Applied Geography 2023, 9, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEAM. Sistemas morfogénicos del territorio Colombiano. Flórez, A. Ed.; Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales, IDEAM: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, V. Rasgos geológicos de los Llanos de Colombia Oriental. Instituto Del Museo de La Universidad Nacional de La Plata 1942, 21, 229–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hubach, E. Significado geológico de la Llanura Oriental de Colombia. Instituto Geológico Nacional: 1954; No. 1004.

- Jaramillo, A. ; Rangel-CH., J.O. Las unidades del paisaje y los bloques del territorio en la Orinoquia. In: Colombia Diversidad Biótica: La región de la Orinoquia de Colombia; Rangel-Ch., J.O. Ed.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2014a; Volumen 14, pp. 101–152.

- Jaramillo, A. , & Rangel-CH, J. O. Los sistemas fluviales de la Orinoquia colombiana. In: Colombia Diversidad Biótica: La región de la Orinoquia de Colombia; Rangel-Ch., J.O. Ed.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2014b; Volumen 14, pp. 71–99.

- Schargel, R. Geomorfología y suelos de los Llanos venezolanos. In: Tierras Llaneras de Venezuela; Hétier, J., López-Falcón, R., Eds.; Centro Interamericano de Desarrollo e Investigación Ambiental y Territorial CIDIAT: 2015; pp. 63–125.

- Molano, J. Biogeografía de la Orinoquia colombiana. In: Colombia Orinoco; Fondo FEN, 1998; pp. 69–101.

- Botero, P. Proyecto Orinoquia-Amazonia colombiana (Informe final). Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, IGAC: 1990.

- Minorta-Cely, V.; Rangel-CH., J.O. El clima de la Orinoquia colombiana. In: Colombia Diversidad Biótica: La región de la Orinoquia de Colombia; Rangel-Ch., J.O. Ed. Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 153–206.

- Eslava, J. Climatología y diversidad climática de Colombia. Revista de La Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 1993, 18, 507–538. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, N.; Garduño, R. Algunas consideraciones acerca de los sistemas de clasificación climática. ContactoS 2008, 68, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-CH., J.O.; Rivera-Díaz, O. Diversidad y riqueza de espermatofitos en el Chocó Biogeográfico. In: Colombia Diversidad Biótica: El Chocó Biogeográfico/ Costa Pacífica; Rangel-Ch., J.O. Ed. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales - Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 83–104.

- Niño, L.; Morales, J.A.; Castro-Salas, M.; Alcalá, L. Análisis espacial de un índice pupal de Aedes aegypti: una configuración del riesgo de transmisión de arbovirosis. Investigaciones Geográficas 2020, 74, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.; Hijmans, R. Worldclim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, IGAC. Mapa de geopedología del territorio colombiano (Escala 1:100.000), Instituto, B: Geográfico Agustín Codazzi: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2014.

- Ananth, C.; Kleinbaum, D. Regression Models for Ordinal Responses: A Review of Methods and Applications. International Journal of Epidemiology 1997, 26, 1323–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño, L. Caracterización de la lactancia materna y factores asociados en Puerto Carreño, Colombia. Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Facultad de Medicina - Instituto de Salud Pública: Bogotá.D.C., Colombia, 2014.

- Lozada, J.R.; Soriano, P.; Costa, M. Relaciones suelo-vegetación en una toposecuencia del Escudo Guayanés, Venezuela. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2014, 62, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories (Ordinal Reclassification) |

Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Diversity Category (Richnees: dependent variable) |

Paucispecific, 0-9 species (1) | 104 | 37,0 |

| Oligospecific, 10-14 species (2) | 103 | 36,7 | |

| Mesospecific, 15-21 species (3) | 68 | 24,2 | |

| Polyspecific, 22-38 species (4) | 6 | 2,1 | |

| Soil Depth (covariate) |

Shallow (1) | 55 | 19,6 |

| Shallow to Moderatly Depth (2) | 22 | 7,8 | |

| Moderatly Depth to Shallow (3) | 109 | 38,8 | |

| Moderatly Deep (4) | 62 | 22,1 | |

| Moderatly Depth to Deepth (5) | 1 | 0,4 | |

| Deepth(6) | 32 | 11,4 | |

| Soil Texture (covariate) |

Fine (1) | 161 | 57,3 |

| Fine to Medium (2) | 4 | 1,4 | |

| Fine to Coarse (3) | 17 | 6 | |

| Medium to Fine (4) | 43 | 15,3 | |

| Medium (5) | 1 | 0,4 | |

| Coarse to Fine (6) | 18 | 6,4 | |

| Coarse to Medium (7) | 5 | 1,8 | |

| Coarse (8) | 32 | 11,4 | |

| Soil Moisture Regime (covariate) |

Ustic (1) | 6 | 2,1 |

| Ustic to Udic (2) | 2 | 0,7 | |

| Udic to Ustic (3) | 30 | 10,7 | |

| Udic (4) | 61 | 21,7 | |

| Udic to Aquic (5) | 111 | 39,5 | |

| Aquic to Udic (6) | 22 | 7,8 | |

| Aquic (7) | 49 | 17,4 | |

| Aluminiun Level (covariate) |

High (1) | 213 | 75,8 |

| Medium (2) | 17 | 6 | |

| Low (3) | 51 | 18,1 |

| Scalar Covariate | Range | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Error | Standar Deviation | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Bare Soil | 77 | 0 | 77 | 12,04 | 0,881 | 14,766 | 218,049 |

| Mean Annual Temperature (°C) | 3,6 | 24,7 | 28,3 | 27,106 | 0,0177 | 0,2966 | 0,088 |

| Maximum Monthly Temperature (°C) | 4,6 | 31,7 | 36,3 | 34,582 | 0,029 | 0,4861 | 0,236 |

| Minimum Monthly Temperature (°C) | 3,7 | 19,1 | 22,8 | 21,727 | 0,0198 | 0,3315 | 0,11 |

| Mean Annual Precipitation (mm) | 1453 | 1605 | 3058 | 2253,19 | 11,545 | 193,529 | 37453,289 |

| Maximum Monthly Precipitation (mm) | 180 | 258 | 438 | 337,5 | 1,284 | 21,516 | 462,958 |

| Minimum Monthly Precipitation (mm) | 25 | 6 | 31 | 15,66 | 0,357 | 5,984 | 35,811 |

| Percentage of Terrain Slope | 17,4 | 0 | 17,4 | 1,974 | 0,1554 | 2,6046 | 6,784 |

| Covariate | Tau-b | Rho | Sig. (bilateral) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Depth | 0,140 | 0,006* | |

| Soil Texture | 0,027 | 0,609 | |

| Soil Moisture Regime | -0,107 | 0,035* | |

| Aluminum Level | 0,071 | 0,198 | |

| Percentage of Bare Soil | -0,247 | 0,000* | |

| Mean Annual Temperature | -0,077 | 0,201 | |

| Maximum Monthly Temperature | -0,129 | 0,031* | |

| Minimum Monthly Temperature | -0,159 | 0,008* | |

| Mean Annual Precipitation | -0,127 | 0,034* | |

| Maximum Monthly Precipitation | 0,024 | 0,686 | |

| Minimum Monthly Precipitation | -0,159 | 0,008* | |

| Percentage of Terrain Slope | -0,055 | 0,362 |

| Ordinal Regression Statistics (Bivariate / Multivariate) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Coefficient | Error | Wald |

| Soil Depth | 0,149 / 0,303 | 0,052 / 0,082 | 9,345 / 13,536 |

| Soil Moisture Regime | -0,105 / 0,156 | 0,056 / 0,091 | 3,444 / 2,955 |

| Percentage of Bare Soil | -0,017 / -0,028 | 0,006 / 0,007 | 7,743 / 17,180 |

| Maximum Monthly Temperature | -0,239 / -0,359 | 0,154 / 0,342 | 2,407 / 1,101 |

| Minimum Monthly Temperature | -0,309 /0,431 | 0,224 / 0,542 | 1,902 / 0,633 |

| Mean Annual Precipitation | -0,001 / 0,001 | 0,000 / 0,001 | 2,770 / 1,453 |

| Minimum Monthly Precipitation | -0,031 / -0,100 | 0,013 / 0,033 | 5,776 / 9,135 |

| Coefficient | Error | Wald | gl | Sig. | Confidence Interval 95% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Weighted Richness Thresholds (WRT) | WRT = 1 | 0,333 | 0,645 | 0,267 | 1 | 0,605 | -0,931 | 1,597 |

| WRT = 2 | 1,599 | 0,654 | 5,986 | 1 | 0,014 | 0,318 | 2,881 | |

| WRT = 3 | 4,297 | 0,763 | 31,723 | 1 | 0,000 | 2,802 | 5,793 | |

| Covariates | Soil Depth (SOIL_DEPTH) | 0,311 | 0,081 | 14,807 | 1 | 0,000 | 0,152 | 0,469 |

| Soil Moisture Regime (SOIL_MOIST) | 0,154 | 0,089 | 3,007 | 1 | 0,083 | -0,02 | 0,329 | |

| Percentage of Bare Soil (BARE_SOIL) | -0,027 | 0,006 | 17,871 | 1 | 0,000 | -0,04 | -0,015 | |

| Minimum Monthly Temperature (MIN_MONTH_TEMP) | -0,067 | 0,015 | 21,257 | 1 | 0,000 | -0,095 | -0,039 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).