Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

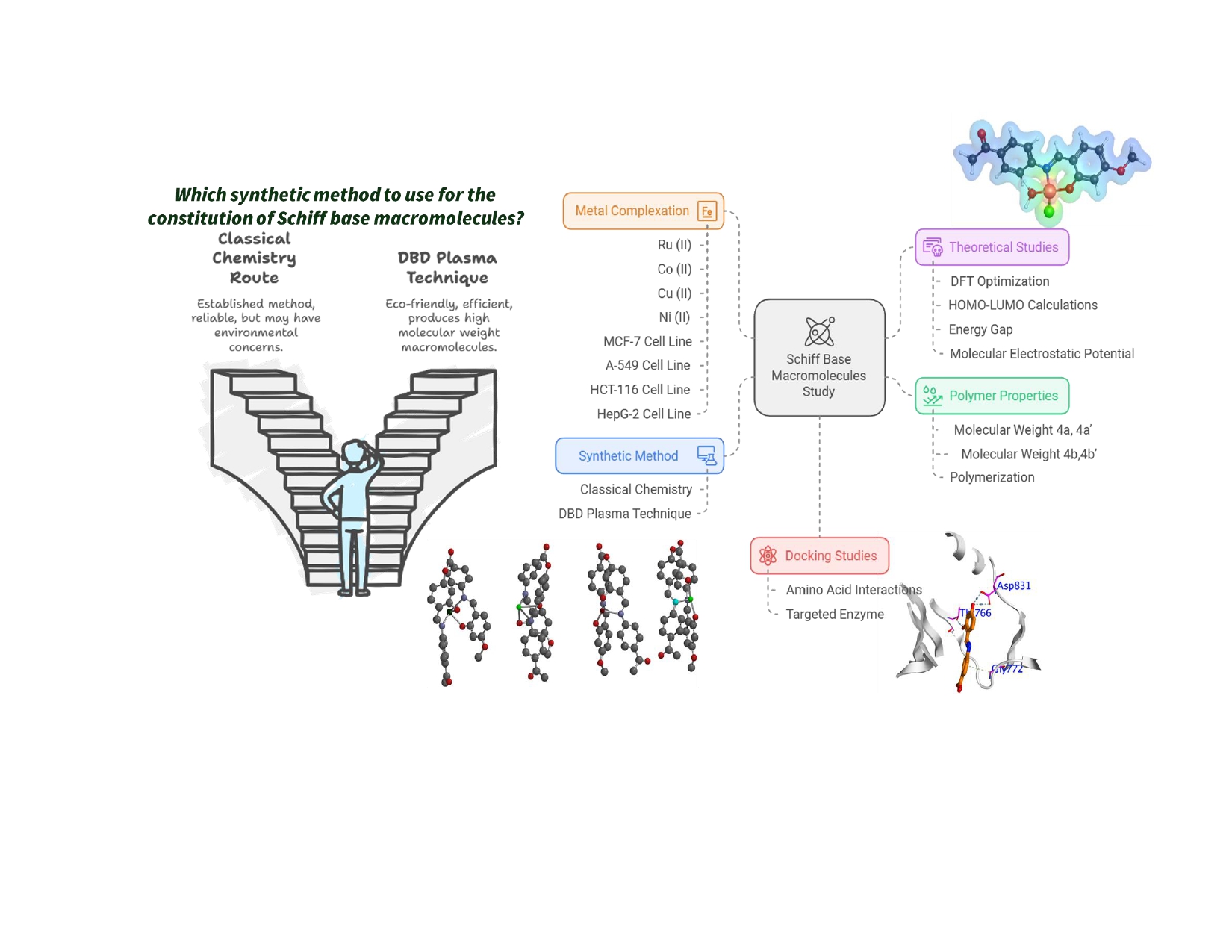

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Characterization

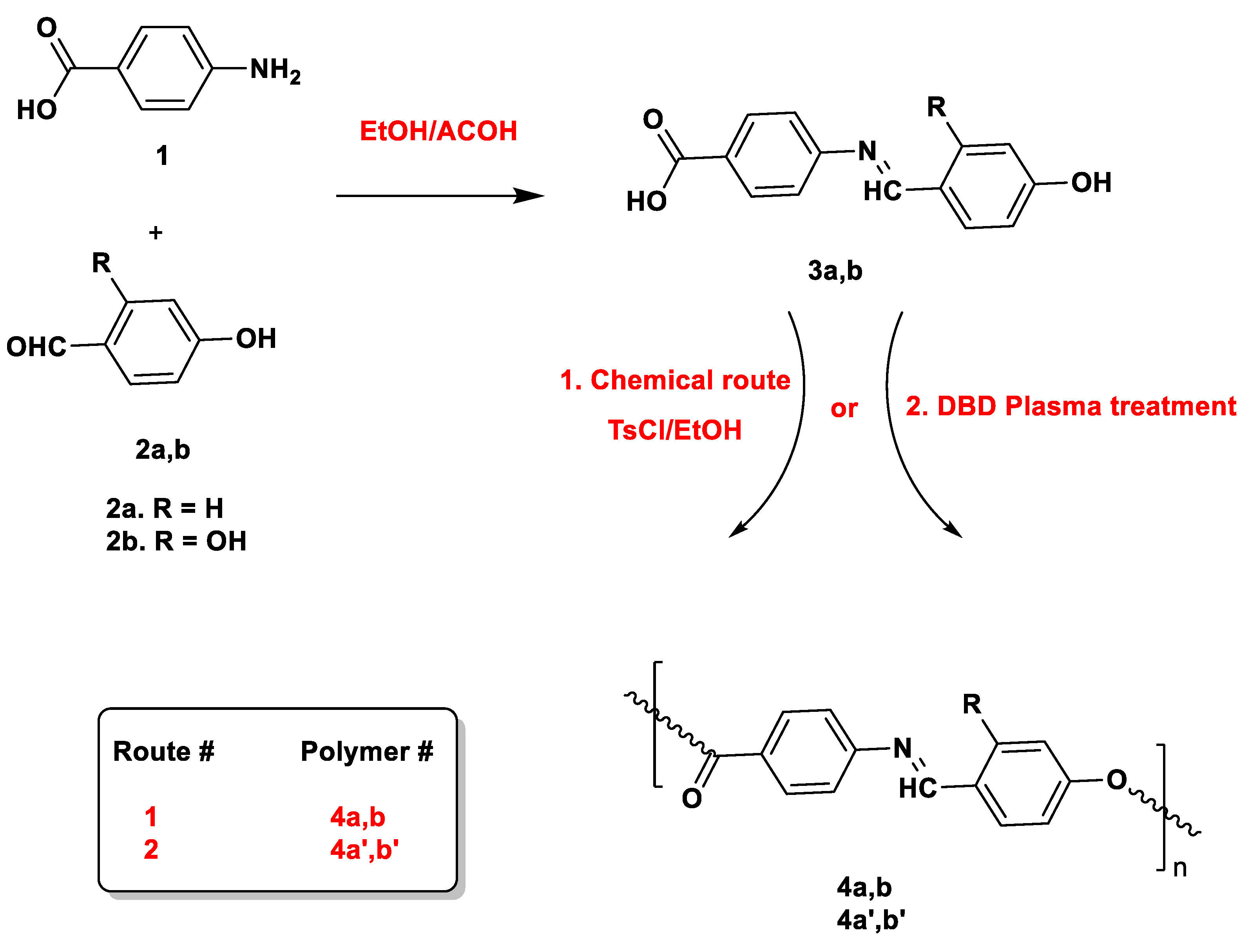

2.2. Synthesis of Schiff Base Monomers 3a,b

2.3. Condensation Polymerization of Schiff Base Monomers

2.4. Complexation of Polymer 4b

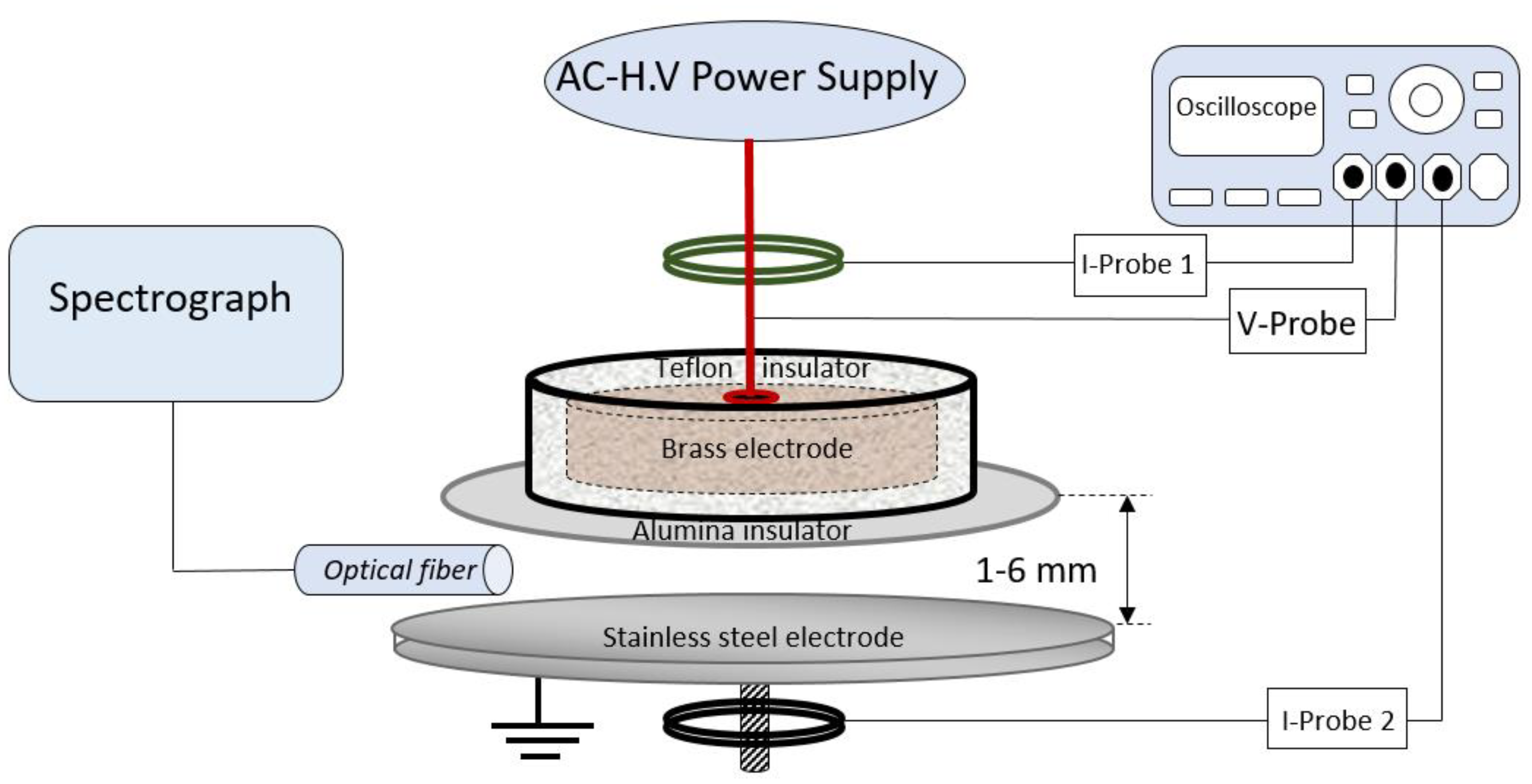

2.5. Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma System

2.6. Antitumor Assay

2.7. Molecular Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of Schiff Base Monomers

3.2. Synthesis of Schiff Base Polymers

3.2.1. Classical Methodology

3.2.1. DBD Plasma Methodology

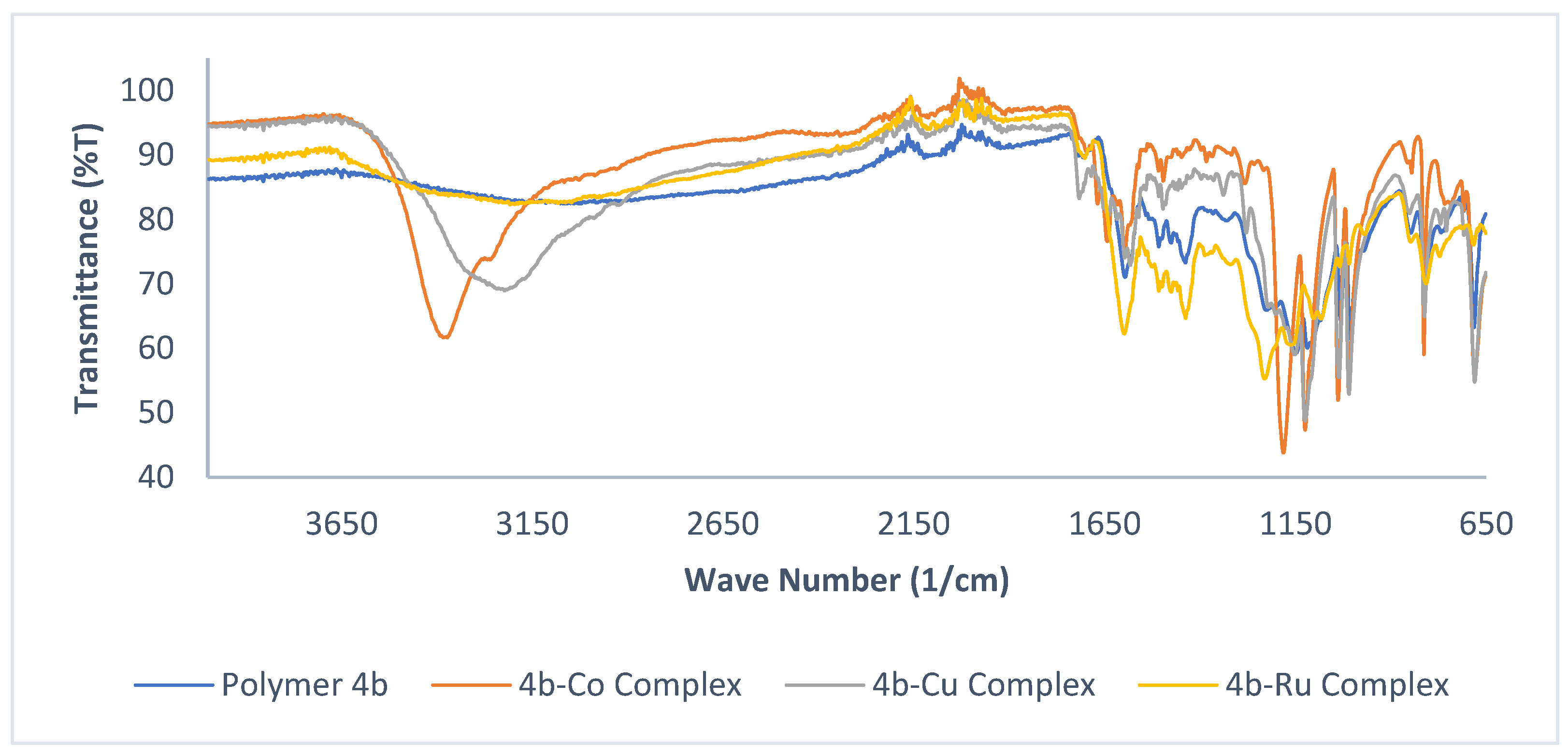

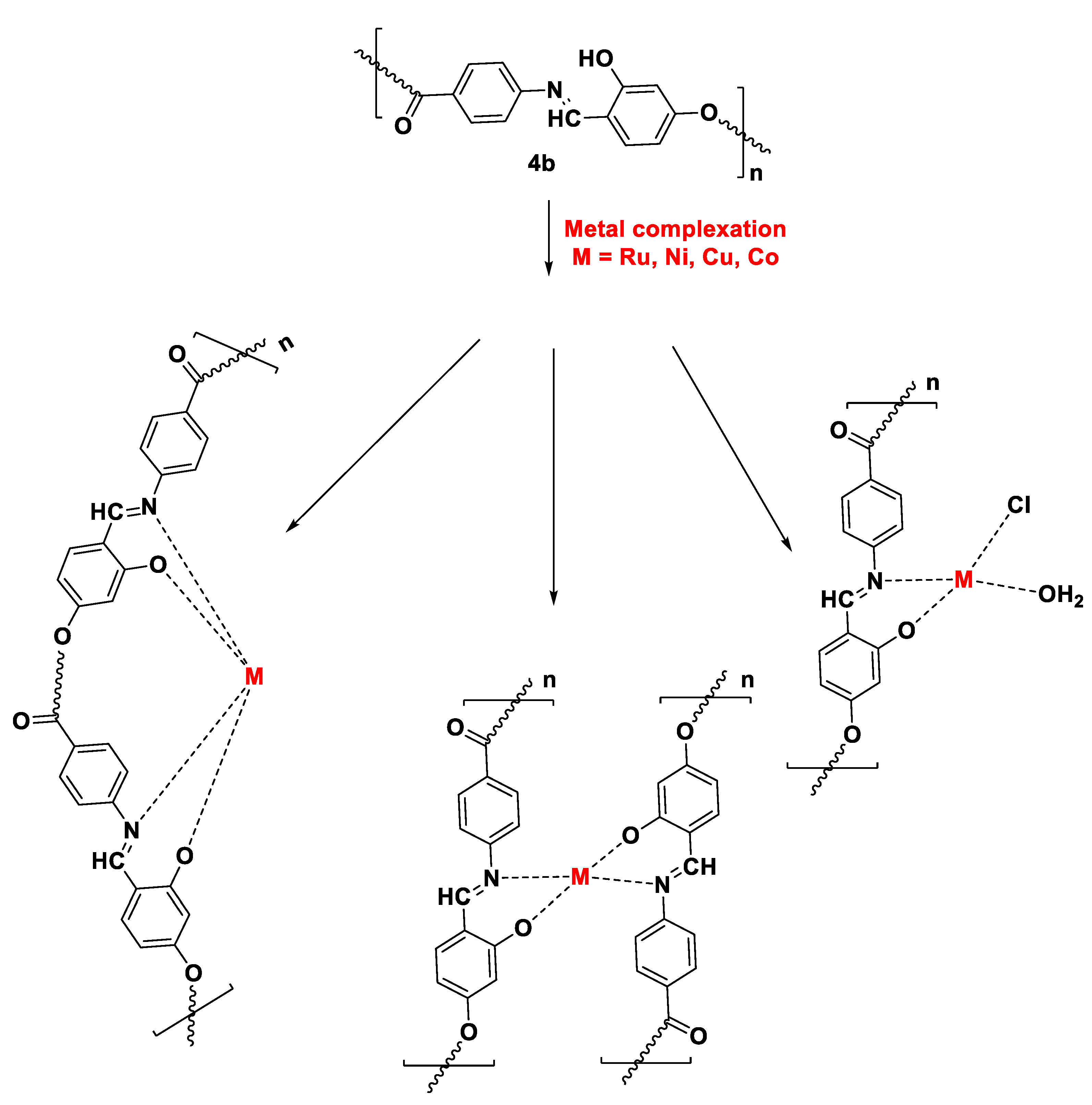

3.3. Complexation of Polymer 4b with Metal Moieties

3.2. Molecular Weight Determination

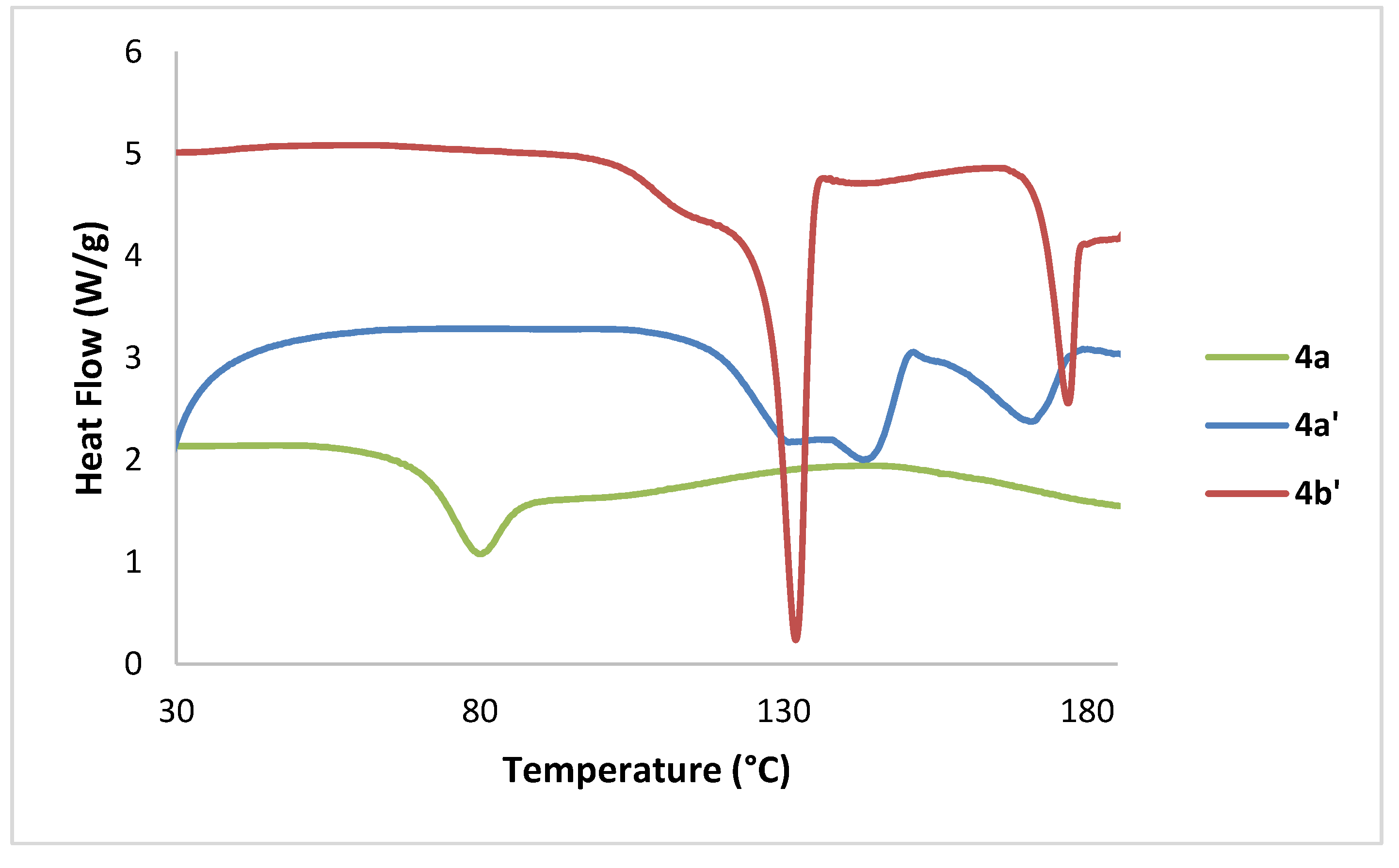

3.3. Thermal Analysis

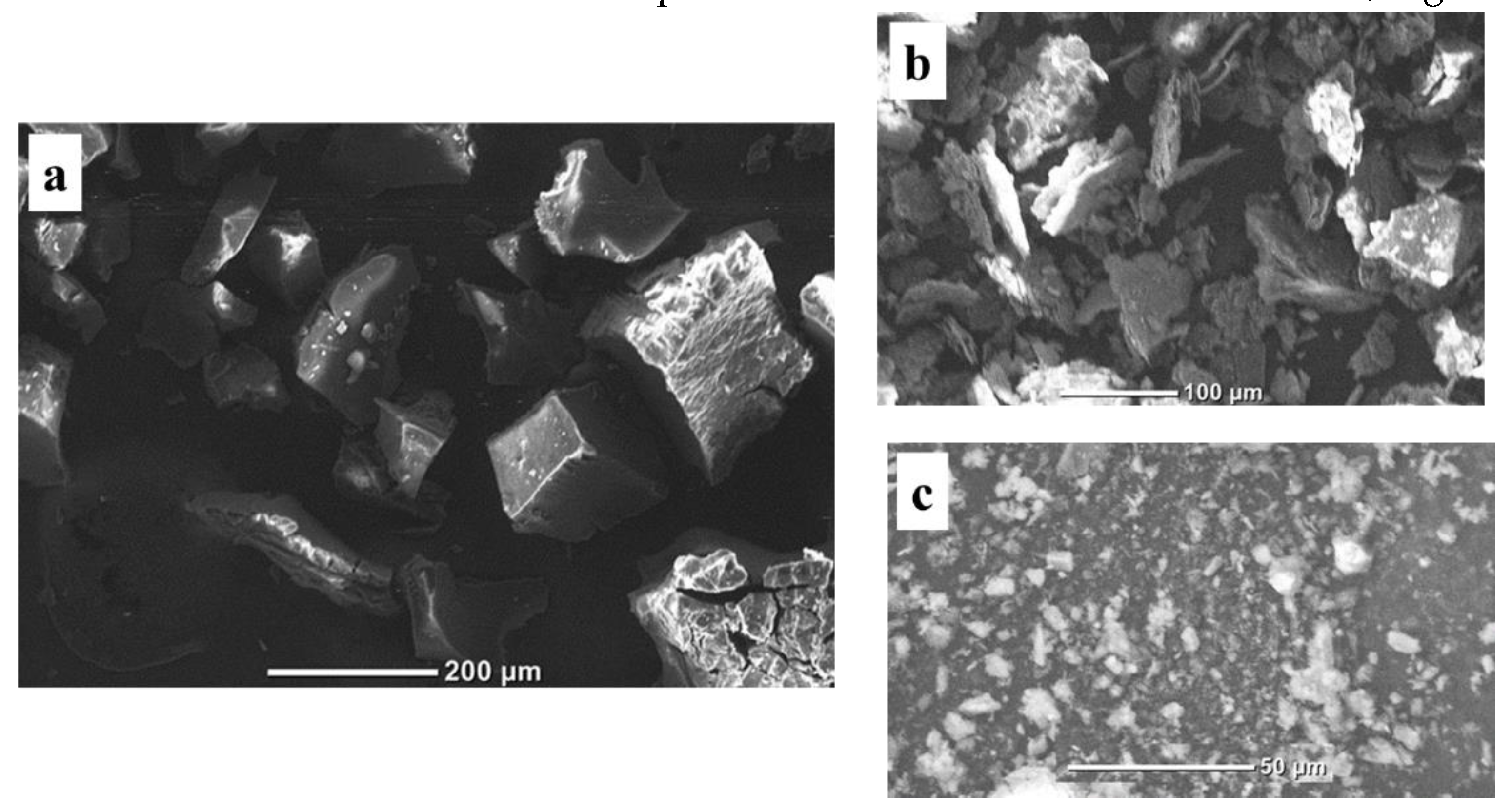

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscope

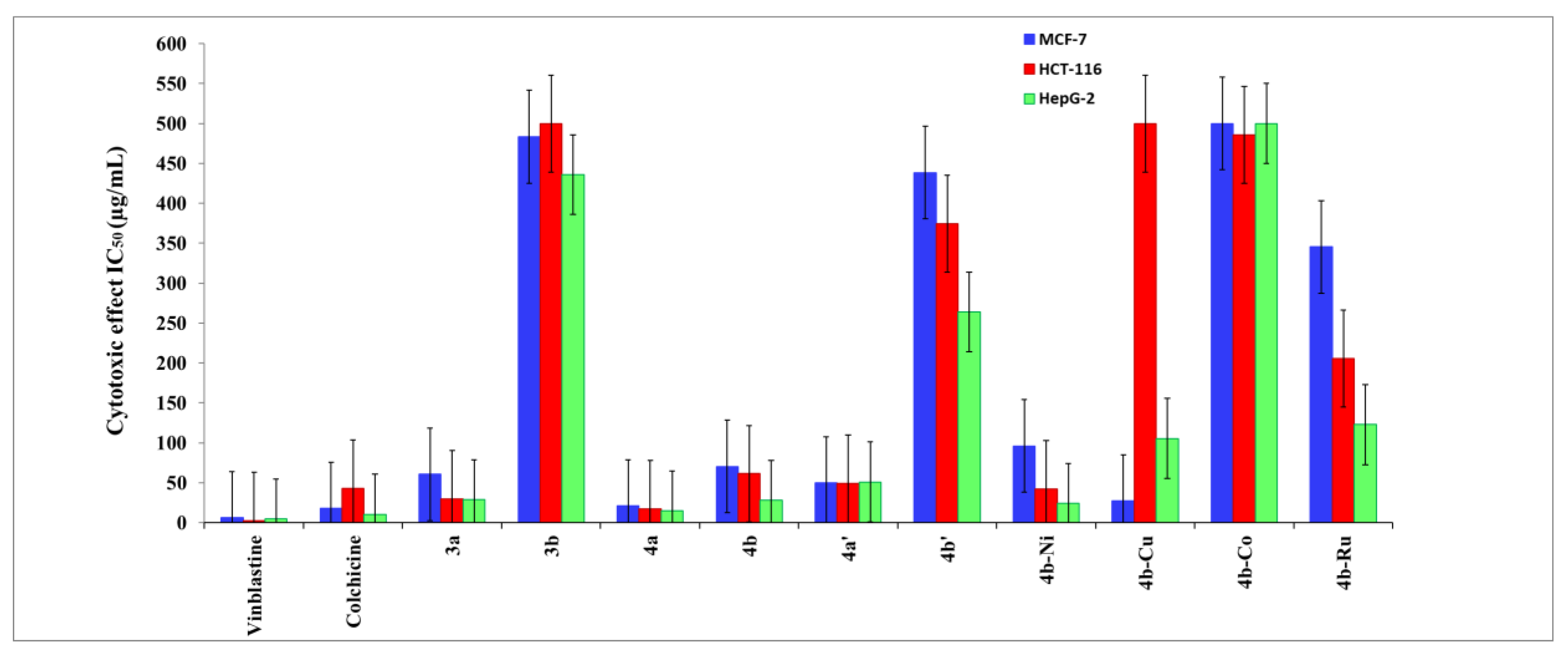

3.5. Antitumor Assay

3.6. Molecular Modeling Studies

3.6.1. Molecular Geometry

3.6.2. Stability Inter- and Intra-molecular Interaction Profile

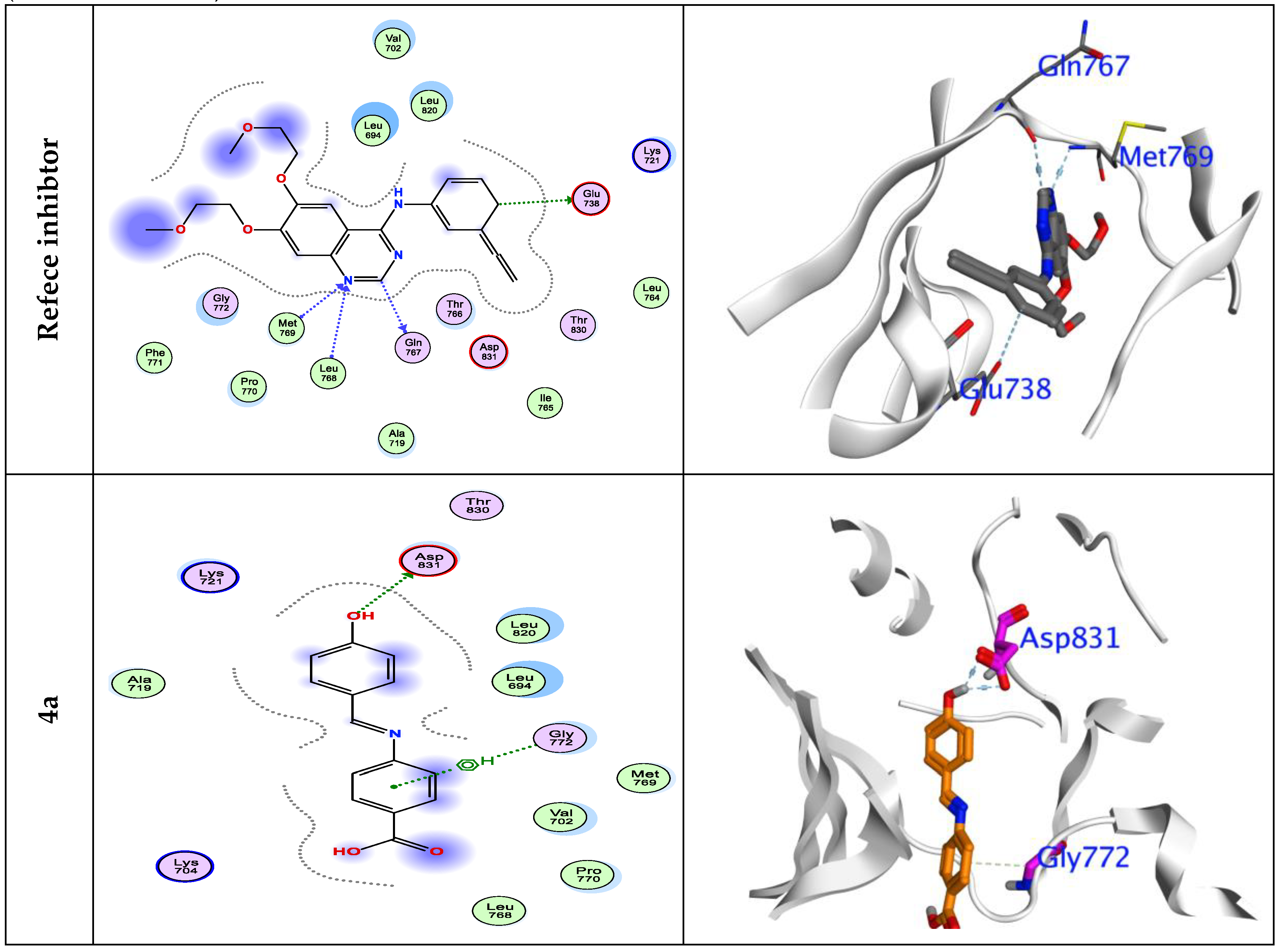

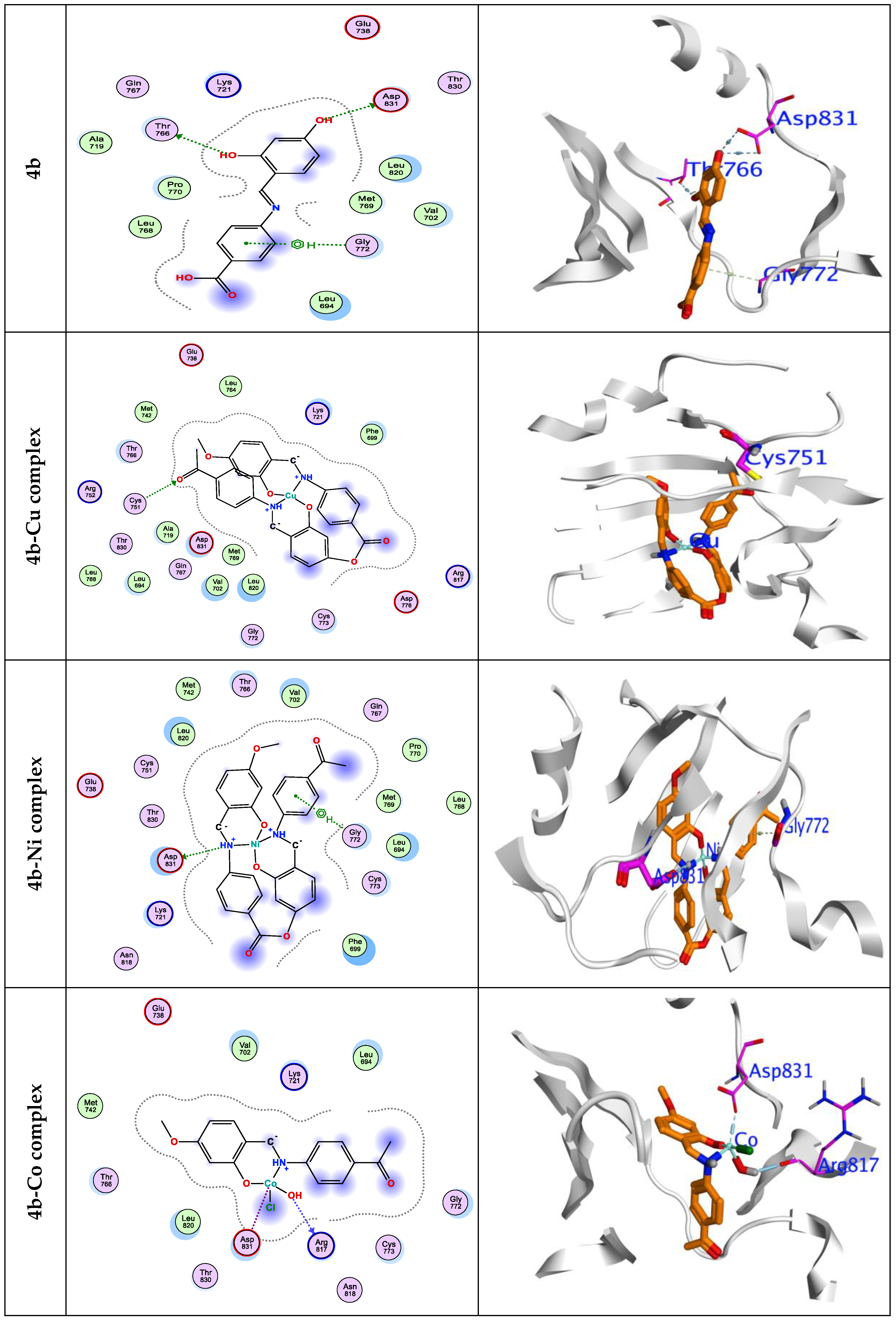

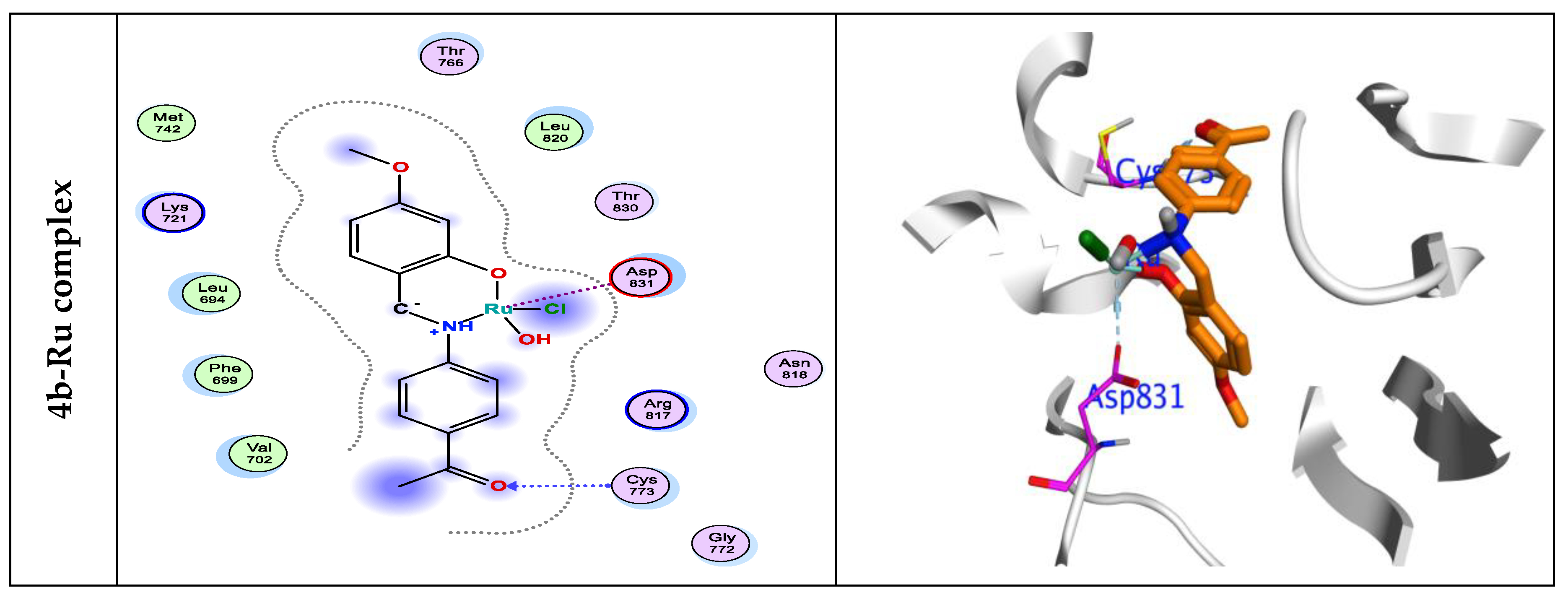

3.7. Molecular Docking Simulations

3.8. In-silico Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu1, C.; Zhu, C.; Synatschke, C.V.; Zhang, X. Editorial: Design, Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Functional Polymers. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 681189. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Okasha, R.M.; Khairou, K.S.; Afifi, T.H.; Mohamed, A.-A. H.; Abd-El-Aziz, A.S. Design of Thermochromic Polynorbornene Bearing Spiropyran Chromophore Moieties: Synthesis, Thermal Behavior and Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma Treatment. Polymers 2017, 9, 630-645. [CrossRef]

- Caló, E.; Khutoryanskiy, V. V. Biomedical applications of hydrogels: A review of patents and commercial products. European Polymer Journal 2015, 65, 252– 267. [CrossRef]

- Love, B. Polymeric Biomaterials. In B. Love (Ed.), Biomaterials: A Systems Approach to Engineering Concepts. 2017, 205– 238, Michigan: Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Aziz, A.S.; El-Ghezlani, E.G.; Elaasser, M.M.; Afifi, T.H.; Okasha, R.M. First Example of Cationic Cyclopentadienyliron Based Chromene Complexes and Polymers: Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Application. J. Inorg. Organomet. Poly. Mater. 2020, 30, 131. [CrossRef]

- Maitz, M. F. (2015). Applications of synthetic polymers in clinical medicine. Biosurface and Biotribology 2015, 1(3), 161– 176. [CrossRef]

- Joraid, A.A.; Okasha, R.M.; Al-Maghrabi, M.A.; Afifi, T.H.; Agatemor, C.; Abd-El-Aziz, A.S. Thermodynamic Parameters of Non-isothermal Degradation of a New Family of Organometallic Dendrimer with Isoconversional Methods. J. Inorg. Organomet. Poly. Mater. 2022, 32, 2653–2663. [CrossRef]

- Teo, A. J. T.; Mishra, A.; Park, I.; Kim, Y. J.; Park, W. T.; Yoon, Y. J. Polymeric Biomaterials for Medical Implants and Devices. ACS Biomaterials Science and Engineering 2016, 2(4), 454– 472. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Vermani, K.; Garg, S. Hydrogels: From controlled release to pH-responsive drug delivery. Drugs Discovery Today 2002, 7(10), 569– 579. [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, J.; Seo, H.; Sim, G.; Avila, R.; Nair, M.; Kim, B.; Choi, Y. Bioresorbable polymers for electronic medicine. Cell Reports Physical Science 2024, 5(8), 102099. [CrossRef]

- Yılmazoğlu, E.; Karakuş, S. Synthesis and specific biomedical applications of polymer brushes. App. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2023, 18, 100544. [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Babar Shahzad, M.; Li, M.; Wang, G.; Xu, D. Antimicrobial materials with medical applications. Materials Technology 2015, 30(B2), B90– B95. [CrossRef]

- Sall, C.; Ayé, M.; Bottzeck, O.; Praud, A.; Blache, Y. Towards smart biocide-free anti-biofilm strategies: Click-based synthesis of cinnamide analogues as anti-biofilm compounds against marine bacteria. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2018, 28(2), 155– 159. [CrossRef]

- Schönemann, E.; Koc, J.; Aldred, N.; Clare, A.S.; Laschewsky, A.; Rosenhahn, A.; Wischerhoff, E. Synthesis of novel sulfobetaine polymers with differing dipole orientations in their side chains, and their effects on the antifouling properties. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 2019, 41, 1900447. [CrossRef]

- Utrata-Wesoek, A. Antifouling surfaces in medical application. Polimery/Polymers, 2013, 58(9), 685– 695. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Liu, X.; Molino, P. J.; Wallace, G. G. (2011). Bio-functionalisation of polydimethylsiloxane with hyaluronic acid and hyaluronic acid – Collagen conjugate for neural interfacing. Biomaterials 2011, 32(21), 4714– 4724. [CrossRef]

- Althakfi, S.H.; Suhail, M.; Locatelli, M.; Hsieh, M.-F.; Alsehli, M.; Hameed, A.M. Advances in Polymeric Colloids for Cancer Treatment. Polymers 2022, 14, 5445. [CrossRef]

- Rabha, B.; Bharadwaj, K.K.; Pati, S.; Choudhury, B.K.; Sarkar, T.; Kari, Z.A.; Edinur, H.T.; Baishya, D.; Atanase, L.I. Development of polymer-based nanoformulations for glioblastoma brain cancer therapy and diagnosis: An update. Polymers 2021, 13, 4114. [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, T.; Alotaibi, H.F.; Prokopovich, P. Polymer colloids as drug delivery systems for the treatment of arthritis. Adv. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2020, 285, 102273. [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Lu, X.; Cao, J.; Wu, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhou, X.; Ding, D. Fluorinated Organic Polymers for Cancer Drug Delivery. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36(30), 2404645. [CrossRef]

- Misiak, P.; Markiewicz, K.H.; Szymczuk, D.; Wilczewska, A.Z. Polymeric Drug Delivery Systems Bearing Cholesterol Moieties: A Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 2620. [CrossRef]

- Jelonek, K.; Kasperczyk, J. Polyesters and polyester carbonates for controlled drug delivery. Part II. Implantable systems. Polimery 2013, 58, 858–863. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. Pharmaceutical Applications of Polymers for Drug Delivery; Rapra Review Reports; Rapra Technology: Shrewsbury, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1-85957-479-9.

- Cheng, L.-C.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, L.-L.; Yang, Q.; Lu, H.-Y. Novel amphiphilic folic acid-cholesterol-chitosan micelles for paclitaxel delivery. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 3315–3326. [CrossRef]

- Borandeh, S.; Bochove, B.V.; Teotia, A.; Seppälä, J. Polymeric drug delivery systems by additive manufacturing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 137, 349-373. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Hsu, SH. Hydrogels Based on Schiff Base Linkages for Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2019, 24(16), 3005. [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.-R.; El-Khalafy, S.H.; Abosharaf, H.A.; El-nshar, E.M.; Ghazy, A.R.; Azaam, M.M. Synthesis, Characterization, and Anticancer Potency of Branched Poly (p-Hydroxy Styrene) Schiff-Bases. Macromol. Biosci. 2023, 23, 2300090. [CrossRef]

- Mighani, H. Schiff Base polymers: synthesis and characterization. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 168. [CrossRef]

- Demirbağ, B.; Büyükafşar, K.; Kaya, H.; Yıldırım, M.; Bucak, Ö.; Ünver, H.; Erdoğan, S. Investigation of the anticancer effect of newly synthesized palladium conjugate Schiff base metal complexes on non-small cell lung cancer cell line and mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2024, 735, 150658. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Deng, Y.; Ren, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, G.; Wang, F.; Wu, X. Novel in situ forming hydrogel based on xanthan and chitosan re-gelifying in liquids for local drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 186, 54–63. https://doi.10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.025.

- Desai, S.B.; Desai, P.B.; Desai, K.R. Synthesis of some Schiff bases, thiazolidones, and azetidinones derived from 2,6-diaminobenzo [1,2-d:4,5-d′]bisthiazole and their anticancer activities. Heterocycl Commun. 2001, 7(1), 83–90. [CrossRef]

- Thakor, P.M.; Patel, J.D.; Patel, R.J.; Chaki, S.H.; Khimani, A.J.; Vaidya, Y.H.; Chauhan, A.P.; Dholakia, A.B.; Patel, V.C.; Patel, A.-K.J.; Bhavsar, N.H.; Patel, H.V. Exploring New Schiff Bases: Synthesis, Characterization, and Multifaceted Analysis for Biomedical Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9 (33), 35431-35448. [CrossRef]

- Azam, F.; Singh, S.; Khokhra, S.L.; Prakash, O. Synthesis of Schiff bases of naphtha [1,2-d]thiazol-2-amine and metal complexes of 2-(2’-hydroxy)benzylideneaminonaphthothiazole as potential antimicrobial agents. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2007, 8(6), 446-52. [CrossRef]

- Trávníček, Z.; Maloň, M.; Šindelář, Z.; Doležal, K.; Rolčik, J.; Kryštof, V.; Strnad, M.; Marek, J. Preparation, physicochemical properties and biological activity of copper(II) complexes with 6-(2-chlorobenzylamino) purine (HL) or 6-(3-chlorobenzylamino)purine (HL). The single-crystal X-ray structure of [Cu(H+L2)2Cl3]Cl·2H2O. J Inorg Biochem. 2001, 84(1-2), 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Tadele, K.T.; Tsega, T.W. Schiff Bases and their Metal Complexes as Potential Anticancer Candidates: A Review of Recent Works. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2019, 19(15), 1786-1795. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Rana, M.; Sultana, R.; Mehandi, R.; Rahisuddin. Schiff Base Metal Complexes as Antimicrobial and Anticancer Agents. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 2022, 43(7), 6351–6406. [CrossRef]

- Levchenko, I.; Xu, S.; Baranov, O.; Bazaka, O.; Ivanova, E.P.; Bazaka, K. Plasma and Polymers: Recent Progress and Trends. Molecules 2021, 26(13), 4091. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Jung, E.Y.; Parsons, T.; Tae, H.S.; Park, C.S. A Review of Plasma Synthesis Methods for Polymer Films and Nanoparticles under Atmospheric Pressure Conditions. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13(14), 2267. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, G.; Ghobeira, R.; Morent, R.; Geyter, N.D. Plasma Polymerization for Tissue Engineering Purposes. Recent Research in Polymerization. In Tech 2018, ISBN: 978-953-51-3747-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.72293.

- Krtouš, Z.; Hanyková, L.; Krakovský, I.; Nikitin, D.; Pleskunov, P.; Kylián, O.; Sedlaříková, J.; Kousal, J. Structure of Plasma (re)Polymerized Polylactic Acid Films Fabricated by Plasma-Assisted Vapour Thermal Deposition. Materials 2021, 14, 459. [CrossRef]

- Kima, J.Y.; Leea, Y.; Limb, D.Y. Plasma-modified polyethylene membrane as a separator for lithium-ion polymer battery. Electrochimica. Acta 2009, 54, 3714–3719. 10.1016/j.electacta.2009.01.055.

- Sabetzadeh, N.; Falanaka, C.; Riahifar, R.; Yaghmaee, M.S.; Raissi, B. Plasma treatment of polypropylene membranes coated with zeolite/organic binder layers: Assessment of separator performance in lithium-ion batteries. Solid State Ion. 2021, 363, 115589. [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63.

- Gangadevi, V.; Muthumary, J. Preliminary studies on cytotoxic effect of fungal taxol on cancer cell lines. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 1382–1386. [CrossRef]

- Bensaber, S.M.; Allafe, H.A.; Ermeli, N.B.; Mohamed, S.B.; Zetrini, A.A.; Alsabri, S.G.; Erhuma, M.; Hermann, A.; Jaeda, M.I.; Gbaj, A.M. Chemical synthesis, molecular modelling, and evaluation of anticancer activity of some pyrazol-3-one Schiff base derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2014, 23, 5120–5134.

- Eltayeb, N.E.; Lasri, J.; Soliman, S.M.; Mavromatis, C.; Hajjar, D.; Elsilk, S.E.; Babgi, B.A.; Hussien, M.A. Crystal structure, DFT, antimicrobial, anticancer and molecular docking of (4E)-4-((aryl)methyleneamino)-1,2-dihydro-2,3-dimethyl-1-phenylpyrazol-5-one. J Mol Struct 2020, 1213, 128185.

- Fayed, E.A.; Eldin, R.R.E.; Mehany, A.; Bayoumi, A.H.; Ammar, Y.A. Isatin-Schiff’s base and chalcone hybrids as chemically apoptotic inducers and EGFR inhibitors; design, synthesis, anti-proliferative activities and in silico evaluation. J Mol Struct 2021, 1234, 130159.

- Ghasemi, M.; Liang, S.; Luu, Q. M.; Kempson, I. The MTT Assay: A Method for Error Minimization and Interpretation in Measuring Cytotoxicity and Estimating Cell Viability. Springer Protocols, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Assays to Assess the Proliferative Behavior of Cancer Cells. ScienceDirect Topics, 2023. (Sigma Aldrich). [CrossRef]

- MTT Assay Protocol for Cell Viability and Proliferation. Sigma-Aldrich, 2023. https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/US/en/technical-documents/protocol/cell-culture-and-cell-culture-analysis/cell-based-assays/mtt-assay-for-cell-viability-and-proliferation (Sigma Aldrich).

- Vistica, V. T.; Skehan, P.; Scudiero, D.; Monks, A.; Pittman, A.; Boyd, M. R. Tetrazolium-based Assays for Cellular Viability: A Critical Examination of Selected Parameters Affecting Formazan Production. Cancer Res. 1991, 51 (10), 2515-2520.

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65 (1-2), 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Hehre WJ, Huang WW. Chemistry with computation: an introduction to SPARTAN. Wavefunction, Incorporated; 1995.

- Alam, W., Khan, H., Jan, M.S., W. Darwish, H., Daglia, M. and A. Elhenawy, A., 2024. In vitro 5-LOX inhibitory and antioxidant potential of isoxazole derivatives. PloS one, 19(10), p.e0297398. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J. Mechanisms of Plasma Polymerization –Reviewed from a Chemical Point of View. Plasma Process. Polym. 2011, 8, 783–802. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Ku¨hn, G.; Mix, R.; Retzko, I.; Gerstung, V.; Weidner, S.T.; Schulze, R.-D.; Unger, W. in: Polyimides and other High Temperature Polymers: Synthesis, Characterization and Applications, K. L. Mittal, Ed., VSP, Utrecht, 2003, 359– 388.

- Khan, F., Alam, A., Rehman, N.U., Ullah, S., Elhenawy, A.A., Ali, M., Islam, W.U., Khan, A., Al-Harrasi, A., Ahmad, M. and Haitao, Y., 2025. Synthesis, anticancer, α-glucosidase inhibition, molecular docking and dynamics studies of hydrazone-Schiff bases bearing polyhydroquinoline scaffold: In vitro and in silico approaches. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1321, p.139699. [CrossRef]

- Rafik, A., Tüzün, B., Zouihri, H., Poustforoosh, A., Hsissou, R., Elhenawy, A. and Guedira, T., 2024. Morphology Studies, Optic Proprieties, Hirschfeld Electrostatic Potential Mapping, Docking Molecular Anti-Inflammatory, and Dynamic Molecular Approaches of Hybrid Phosphate. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society, p.101419. [CrossRef]

- Asad, M., Arshad, M.N., Azum, N., Alzahrani, K.A., Marwani, H.M., Elhenawy, A.A., Alam, M.M., Nazreen, S., Snigdha, K. and TN, M.M., 2024. Chitosan/La catalyzed synthesis of novel ferrocenated spiropyrrolizidines: Green synthesis, crystallographic, DFT and Hirshfeld surface studies. Journal of Molecular Structure, p.140240. [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, M.J., Magwaza, N.M., More, G.K. and Elhenawy, A.A., 2024. Synthesis, structure of the N-(Alkyl/Arylsulfonyl) substituted 5-(Bromo/Iodo)-3-methylindazoles and bioactivity screening against some of the biochemical targets linked to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1312, p.138636. [CrossRef]

- Gul, S., Elhenawy, A.A., Ali, Q., Rehman, M.U., Alam, A., Khan, M., AlAsmari, A.F. and Alasmari, F., 2024. Discovering the anti-diabetic potential of thiosemicarbazone derivatives: In vitro α-glucosidase, α-amylase inhibitory activities with molecular docking and DFT investigations. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1312, p.138671. [CrossRef]

- Abdalrazaq, E.A., Abu-Yamin, A.A., Taher, D., Hassan, A.E. and Elhenawy, A.A., 2024. Zn (II) and Cd (II) complexes of dithiocarbamate ligands: synthesis, characterization, anticancer, and theoretical studies. Journal of Sulfur Chemistry, 45(5), pp.714-739. [CrossRef]

- Stamos, J., Sliwkowski, M.X. and Eigenbrot, C., 2002. Structure of the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase domain alone and in complex with a 4-anilinoquinazoline inhibitor. Journal of biological chemistry, 277(48), pp.46265-46272. [CrossRef]

| No. | Compounds | υ(OH) | υ(C=O) | υ(CH=N) | υ(C-O) | M-O | M-N |

| 1 | 3a | 3396 | 1664 | 1630 | 1259 | - | - |

| 2 | 3b | 3405 | 1672 | 1656 | 1218 | - | - |

| 3 | 4a | 2402 | 1712 | 1576 | 1148 | - | - |

| 4 | 4b | 3268 | 1722 | 1576 | 1155 1155 |

- | - |

| 5 | 4b-Co complex | 3367 | 1656 | 1593 | 1187 | 701 | 601 |

| 6 | 4b-Cu complex | 3468 | 1643 | 1584 | 1120 | 704 | 611 |

| 7 | 4b-Ru complex | 3352 | 1721 | 1608 | 1224 | 814 | 734 |

| 8 | 4b-Ni complex | 3332 | 1723 | 1617 | 1205 | 814 | 751 |

| Polymer | Mw | Mn | PDI |

| 4a | 524,664 | 303,388 | 1.042 |

| 4b | 1,503,228 | 1,500,349 | 1.002 |

| 4a’ | 162949 | 161039 | 1.012 |

| 4b’ | 874877 | 560517 | 1.561 |

| Polymer | Weight loss (%) | Tonset (°C) | Tendset (°C) |

| 4a | 22 | 238 | 375 |

| 43 | 378 | 511 | |

| 29 | 763 | 841 | |

| 4b | 20 | 243 | 355 |

| 45 | 398 | 541 | |

| 26 | 784 | 863 | |

| 4a’ | 17 | 209 | 359 |

| 14 | 460 | 563 | |

| 35 | 638 | 716 | |

| 4b’ | 17 | 225 | 286 |

| 32 | 316 | 400 | |

| 29 | 775 | 800 |

| No. | Compounds | IC50 | ||

| HepG-2 | HCT-116 | MCF-7 | ||

| 1 | 3a | 28.72 | 29.82 | 60.77 |

| 2 | 3b | 435.84 | > 500 | 483.40 |

| 3 | 4a | 14.93 | 17.03 | 21.16 |

| 4 | 4b | 28.16 | 61.26 | 70.47 |

| 5 | 4a‘ | 51 | 49.02 | 49.61 |

| 6 | 4b‘ | 264.03 | 374.31 | 438.39 |

| 7 | 4b-Ni complex | 24.43 | 42.28 | 95.99 |

| 8 | 4b-Cu complex | 105.41 | >500 | 27.25 |

| 9 | 4b-Co complex | >500 | 485.89 | >500 |

| 10 | 4b-Ru complex | 122.82 | 205.65 | 345.37 |

| 11 | Colchicine | 10.6 | 42.8 | 17.7 |

| 12 | vinblastin | 4.6 | 2.6 | 6.1 |

| Side by side | Parallel | With H2O | |

| 4b-Cu | -1184.46 | -539.89 | -280.04 |

| 4b-Ni | -1175.59 | -734.14 | -445.95 |

| 4b-Co | -586.46 | -127.65 | -833.71 |

| 4b-Ru | 1085.81 | -128.88 | -445.98 |

| Cpd. | 4a | 4b | 4b-Cu | 4b-Ni | 4b-Co | 4b-Ru |

| HOMO | -7.02 | -7.653 | -12.11 | -10.23 | -10.13 | -8.73 |

| LUMO | -1.11 | -2.953 | -7.02 | -8.05 | -7.57 | -1.68 |

| ΔG | 5.91 | 4.7 | 5.09 | 2.18 | 2.56 | 7.05 |

| I | 7.02 | 7.653 | 12.11 | 10.23 | 10.13 | 8.73 |

| A | 1.11 | 2.953 | 7.02 | 8.05 | 7.57 | 1.68 |

| η | 2.96 | 2.35 | 2.55 | 1.09 | 1.28 | 3.53 |

| S | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.28 |

| χ | -4.07 | -5.3 | -9.57 | -9.14 | -8.85 | -5.21 |

| ωi | 4.07 | 5.2 | 9.57 | 9.14 | 8.85 | 5.31 |

| ω± | 7.62 | 10.62 | 40.73 | 81.21 | 65.61 | 14.29 |

| ΔΝμαξ | -0.69 | -1.13 | -1.88 | -4.19 | -3.46 | -0.74 |

| ΔρKNU | 1.38 | 2.26 | 3.76 | 8.39 | 6.91 | 1.48 |

| ΔρKEle | 2.75 | 4.51 | 7.52 | 16.77 | 13.83 | 2.95 |

| ΔG | RMSD | EInt. | Eele | H. B | LE | Ki | BindingSite | distance | Interactionenergy | |

| 4a | -5.69 | 1.67 | -21.28 | -15.85 | -11.51 | -7.24 | 1.98 | ASP831 | 2.09 | -0.9 |

| ASP831 | 2.08 | -1.2 | ||||||||

| GLY772 | 2.81 | -0.5 | ||||||||

| 4b | -5.77 | 0.83 | -21.17 | -19.45 | -11.04 | -4.67 | 1.54 | ASP831 | 2.18 | -0.6 |

| ASP831 | 2.08 | -0.6 | ||||||||

| THR 766 | 2.21 | -0.6 | ||||||||

| GLY772 | 2.92 | -0.6 | ||||||||

| 4b-Cu | -6.60 | 1.48 | -46.31 | -20.21 | -8.82 | -8.65 | 2.16 | GLY772 | 3.49 | -0.6 |

| 4b-Ni | -7.88 | 1.65 | -48.58 | -25.25 | -9.34 | -5.66 | 1.73 | ASP831 | 2.90 | -3.7 |

| GLY772 | 2.99 | -0.6 | ||||||||

| 4b-Co | -6.52 | 1.99 | -33.39 | -14.34 | -9.41 | -6.93 | 1.94 | ASP831 | 2.12 | -2.6 |

| GLY772 | 2.88 | -0.5 | ||||||||

| 4b-Ru | -6.83 | 1.15 | -23.16 | -17.01 | -9.44 | -4.77 | 1.56 | CYS773 | 2.28 | -1.3 |

| ASP831 | 2.61 | -1.0 |

| Compd.No. | Lipinski parameters | nROTBe | TPSAf | BSg | BBBh | GI ABSi | ||||

| MWa | HBAb | HBDc | LogPo/w | Violations | ||||||

| 4a | 558.15 | 5 | 3 | 1.58 | 0 | 3 | 90.12 | 97.0 | No | High |

| 4b | 553.15 | 4 | 2 | 2.14 | 0 | 3 | 69.89 | 95.2 | No | High |

| 4b-Cu | 408.8 | 7 | 2 | 2.45 | 1 | 2 | 127.01 | 94.5 | No | Low |

| 4b-Ni | 366.66 | 7 | 2 | 1.91 | 1 | 2 | 127.01 | 96.6 | No | Low |

| 4b-Co | 257.24 | 4 | 2 | 0.61 | 0 | 2 | 68.12 | 100 | No | High |

| 4b-Ru | 241.24 | 4 | 2 | 0.61 | 0 | 2 | 68.12 | 94.5 | No | High |

| Compds | AMES toxicity |

LD50 (mole/kg) | Oral rat chronic toxicity (logmg/kgb.w/day) |

Hepato toxicity |

Skin sensitization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | No | 2.292 | 0.530 | No | No |

| 4b | No | 2.094 | 0.602 | No | No |

| 4b-Cu | No | 2.539 | 0.691 | No | No |

| 4b-Ni | No | 2.539 | 0.691 | No | No |

| 4b-Co | No | 2.572 | 1.007 | No | No |

| 4b-Ru | No | 2.572 | 1.002 | No | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).