Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

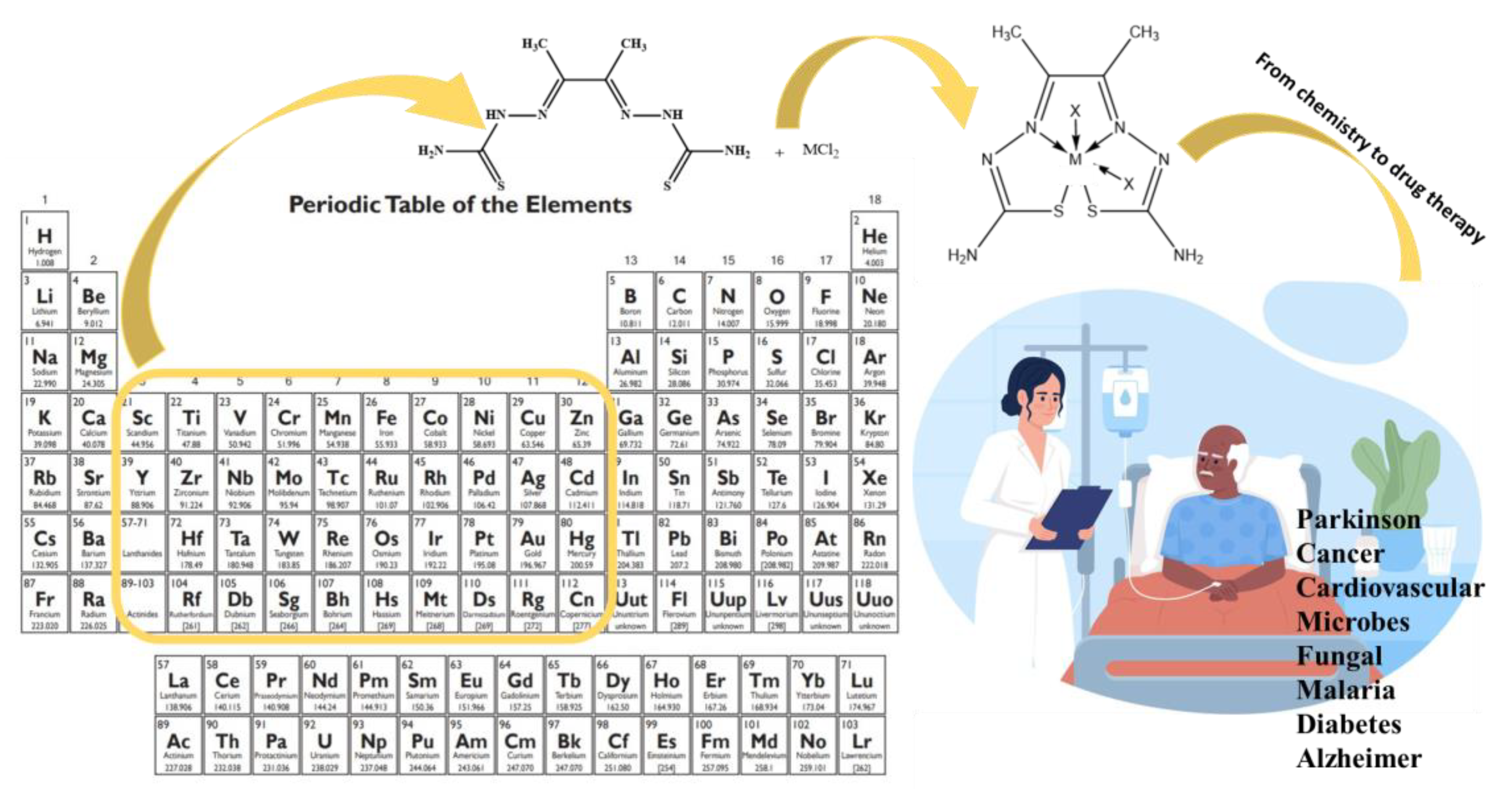

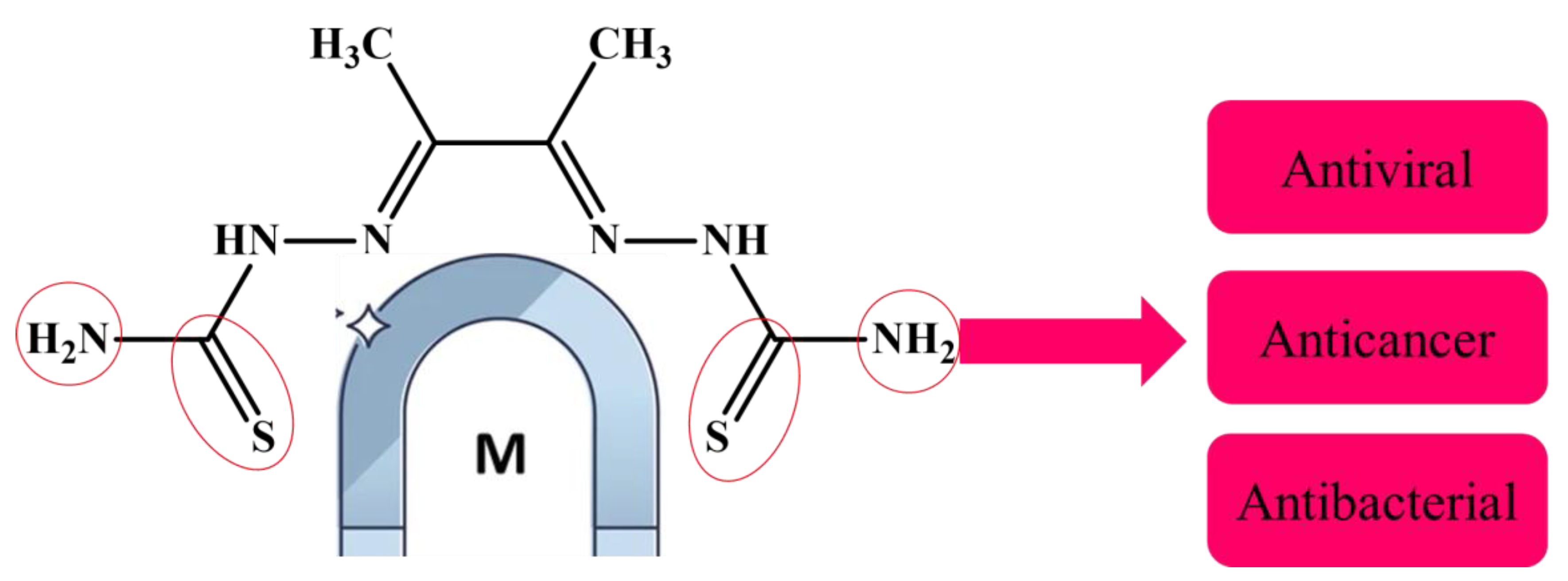

1. Introduction

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Instruments Used

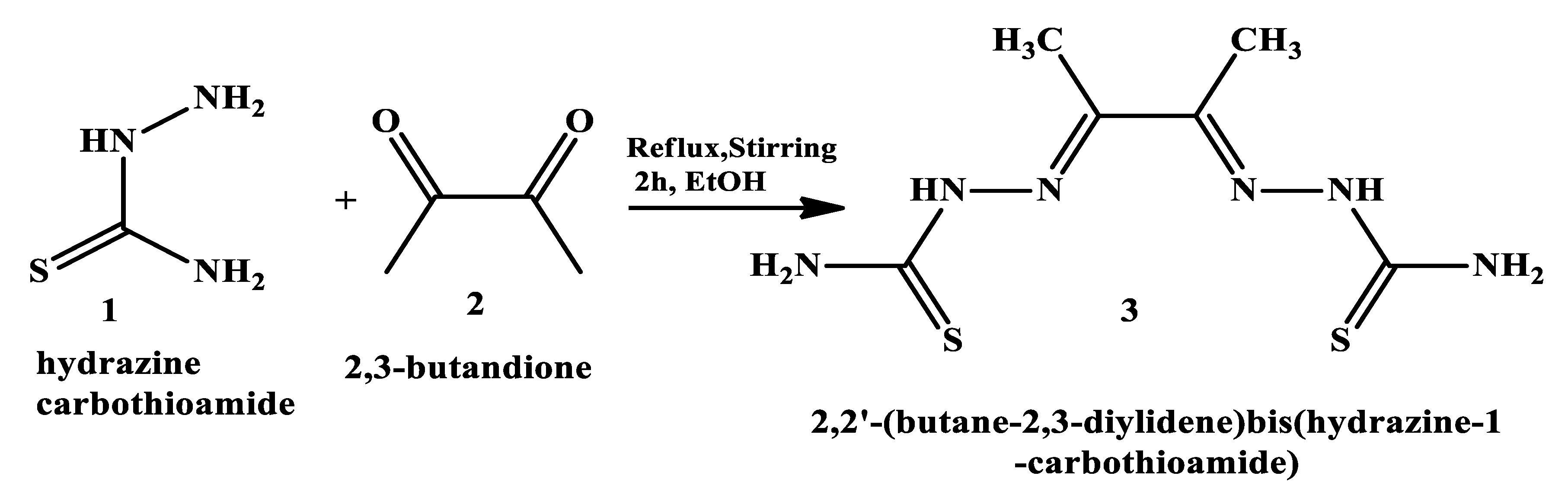

2.3. Synthesis

2.3.1. General synthesis of the ligand: 2,2’-(butane-2,3-diylidene) bis(hydrazine-1-carbothioamide)

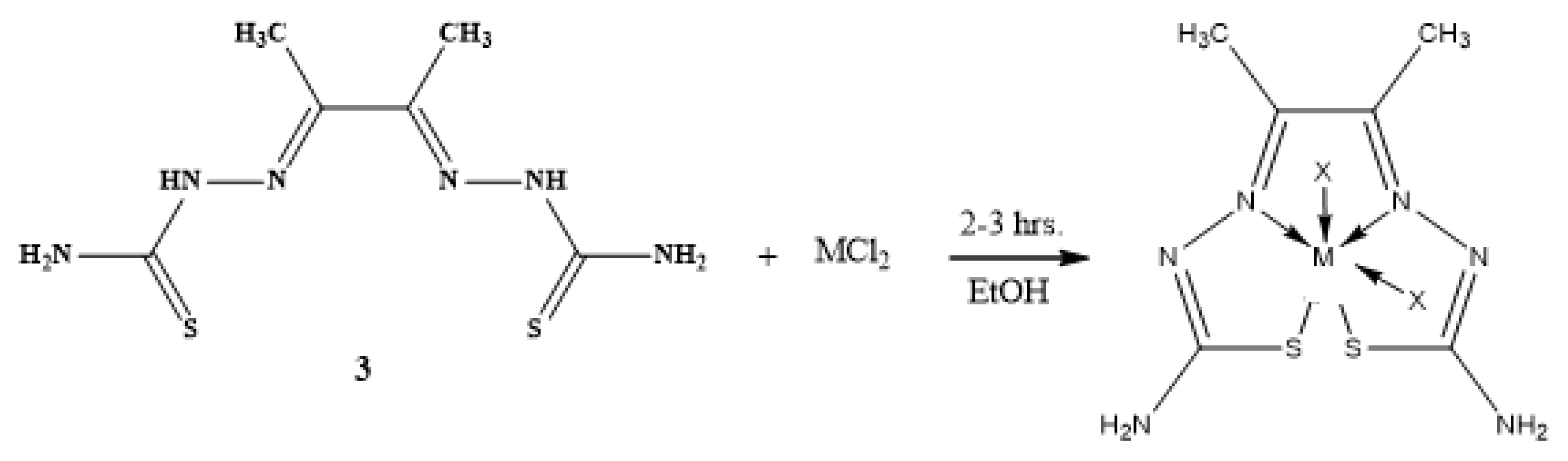

2.3.2. General Synthesis of the Metal-Ligand Complex

2.4. Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry Technique (DSC)

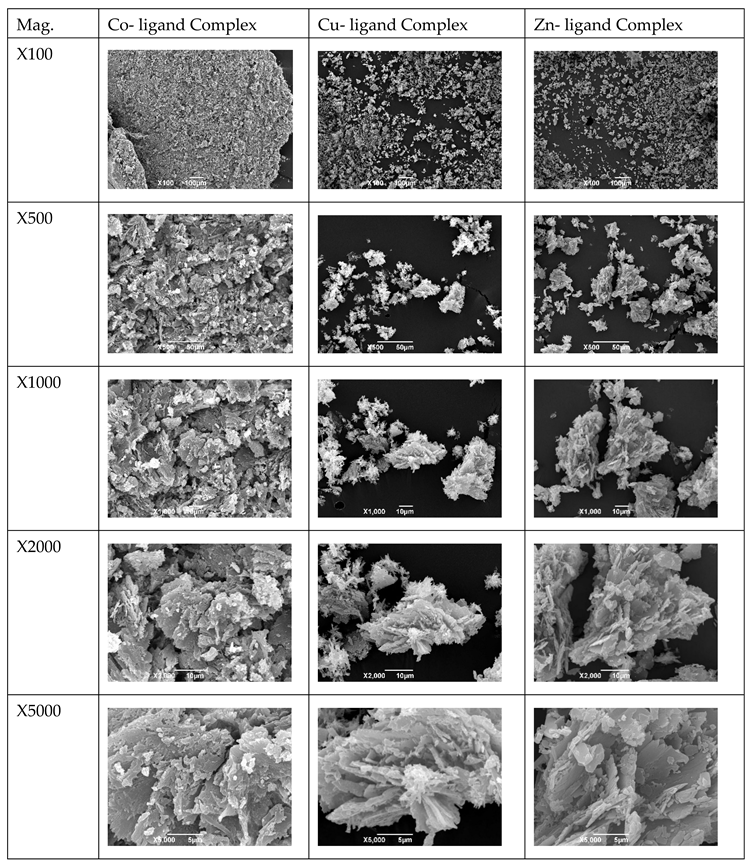

2.6. The Triazole Agents’ Morphology Investigation by SEM

2.7. Particles Size Measurements by DLS

2.8. Cytotoxicity Assessment & Statistical Analysis

2.9. Molecular Geometry and Computational Methodology

2.10. In-Vitro Antibacterial Activity

3. Results and Discussion

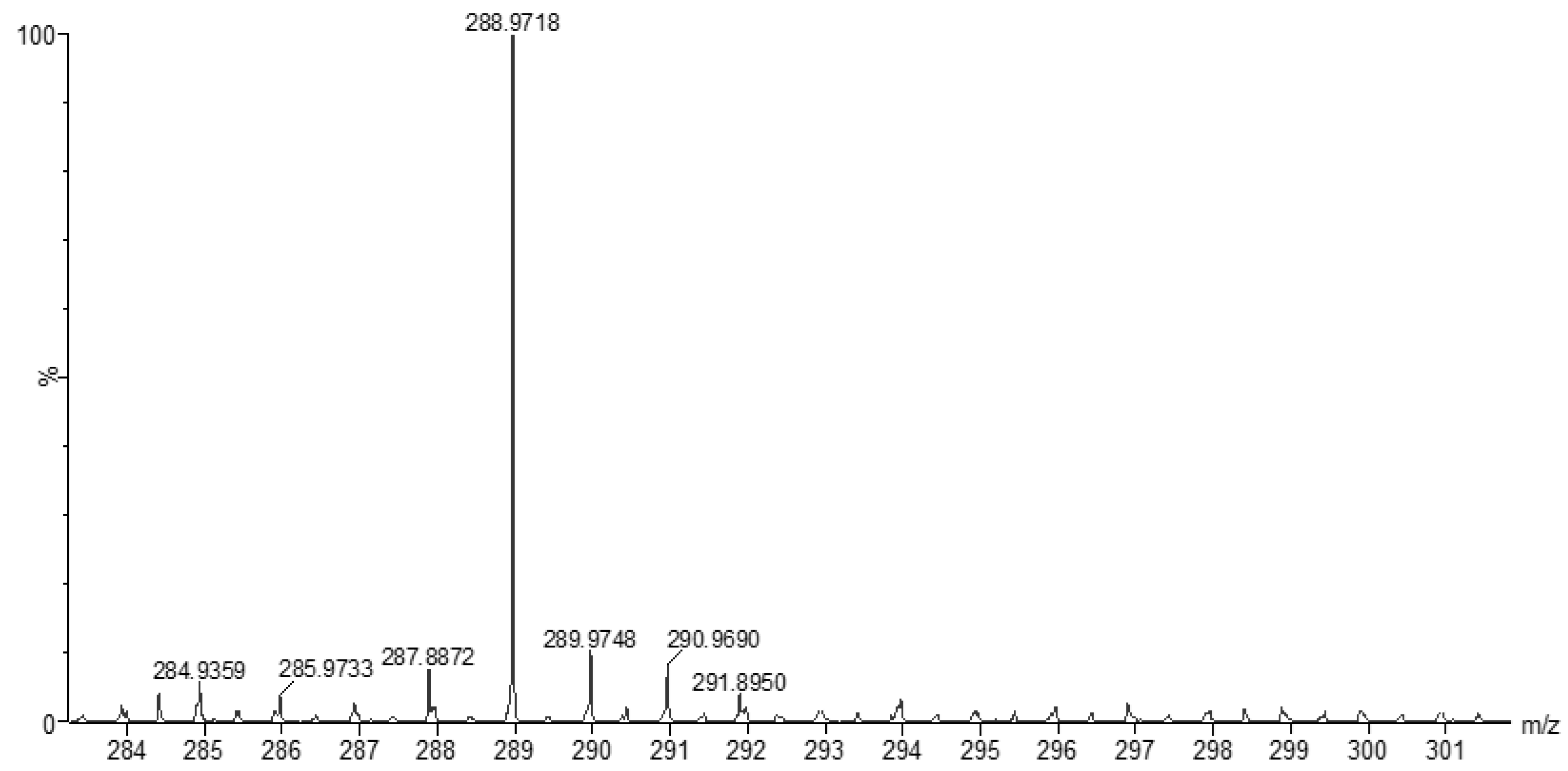

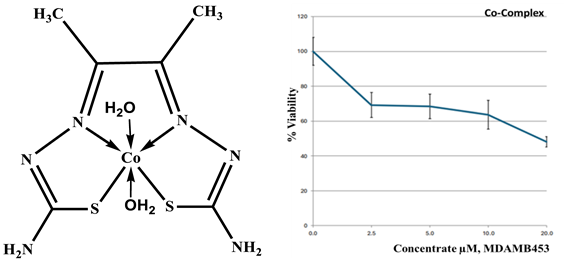

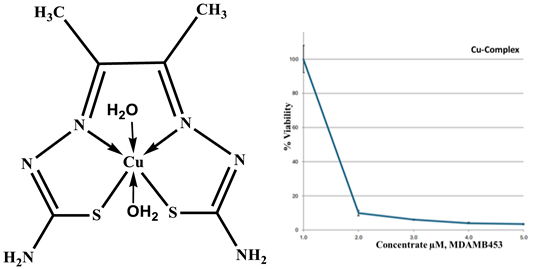

3.1. Elemental Analysis, Electronic Spectra, Magnetic and Physical Measurements

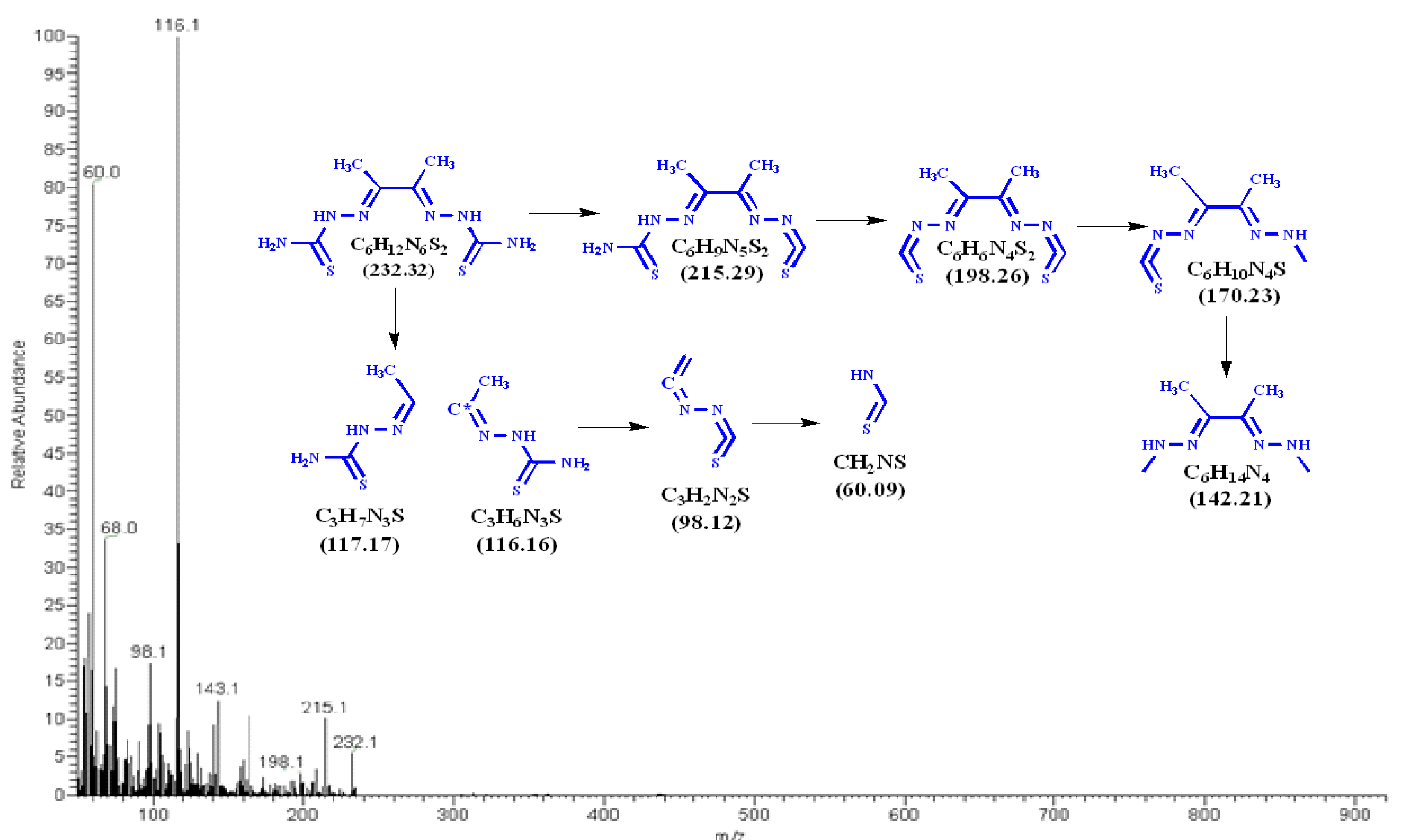

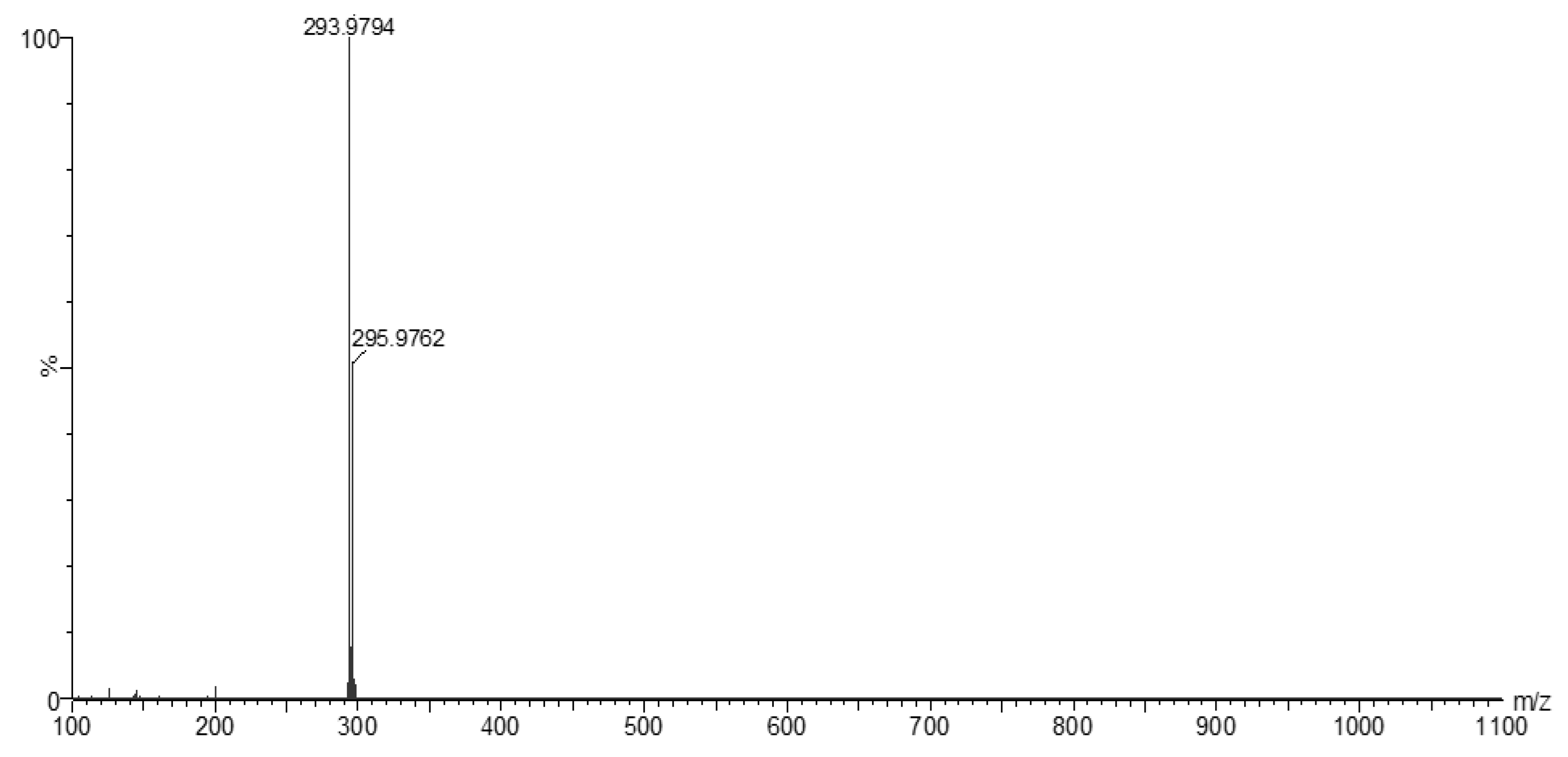

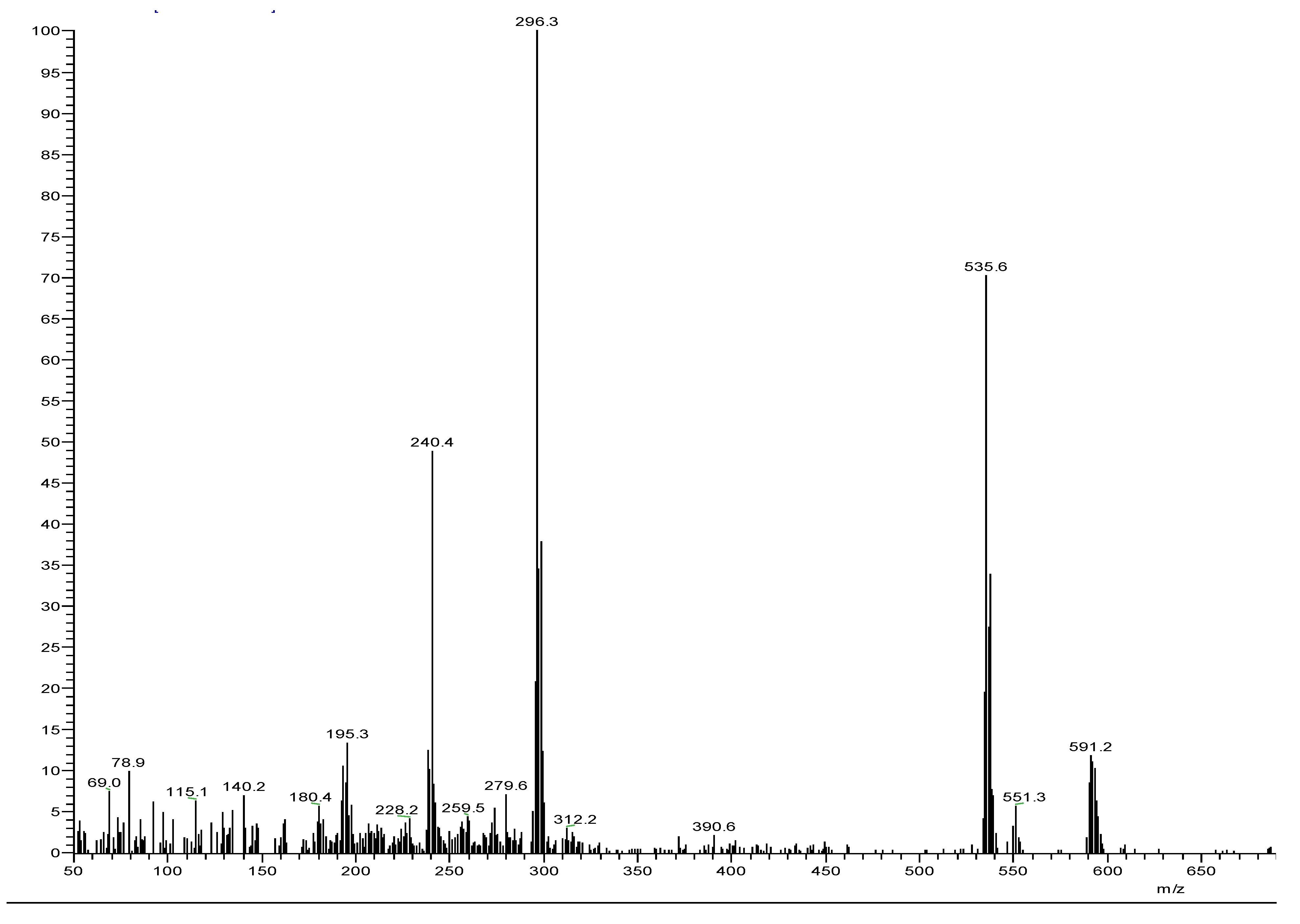

3.2. Mass Spectra of Metal Ligand Complexes (MS).

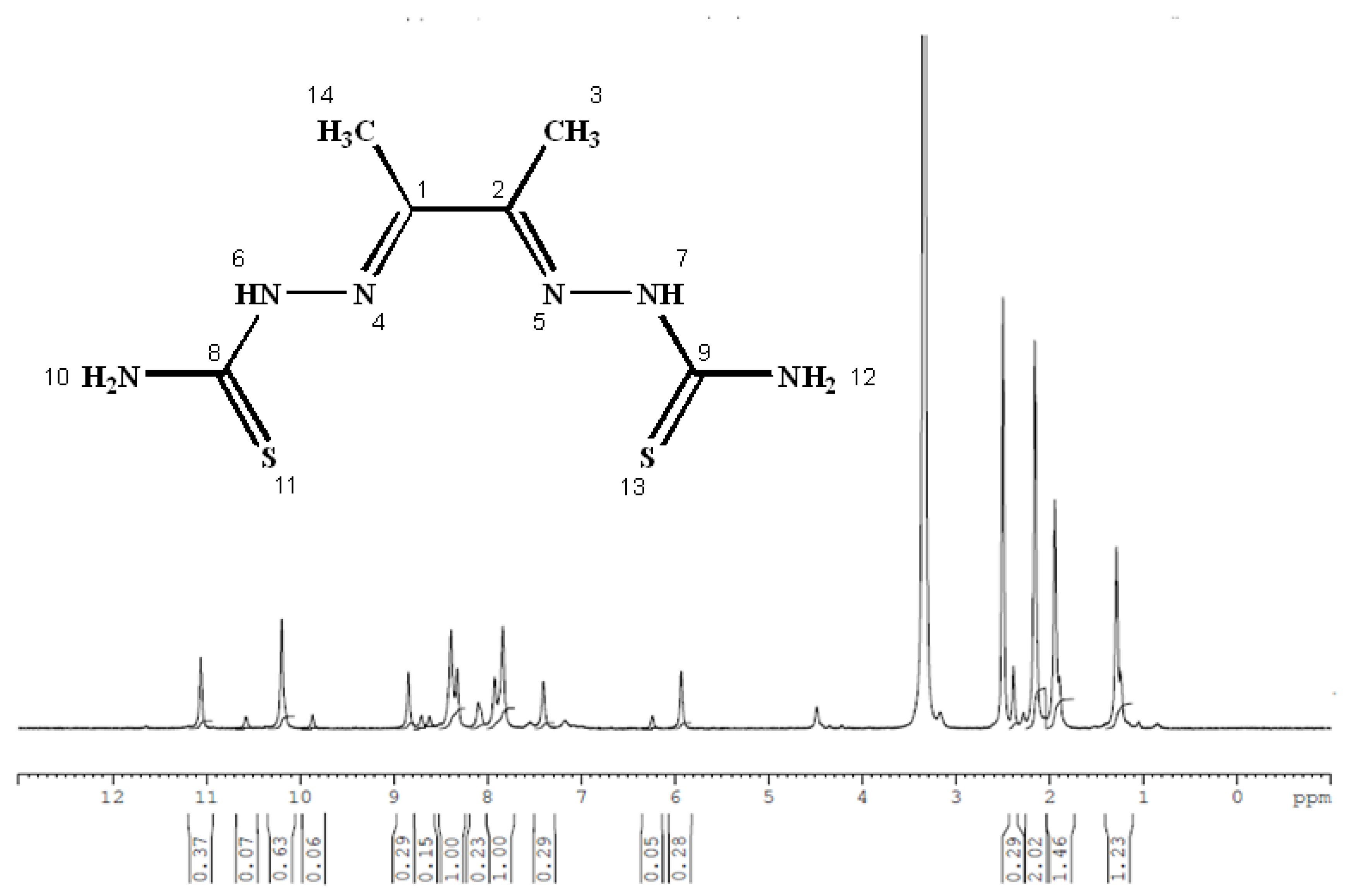

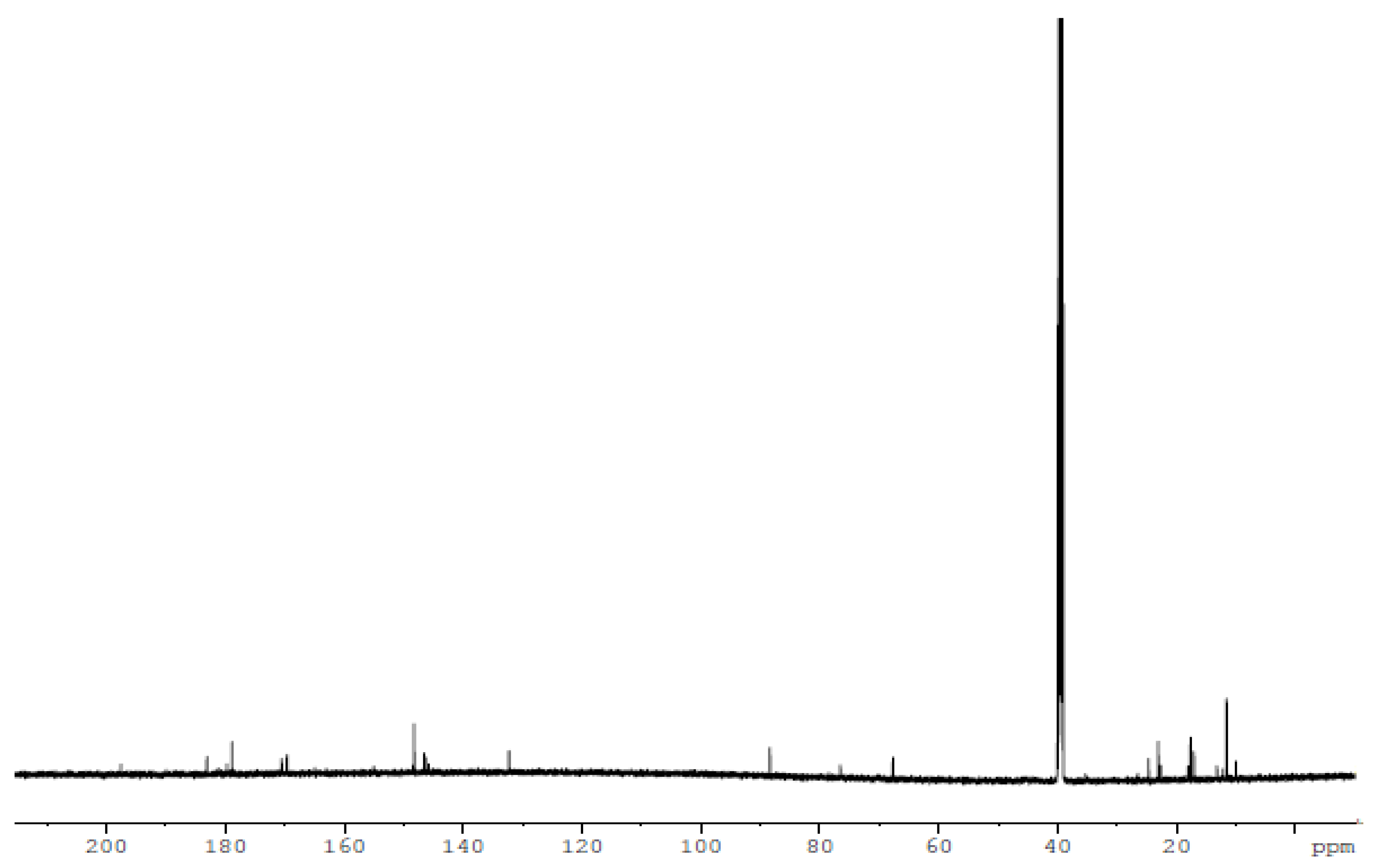

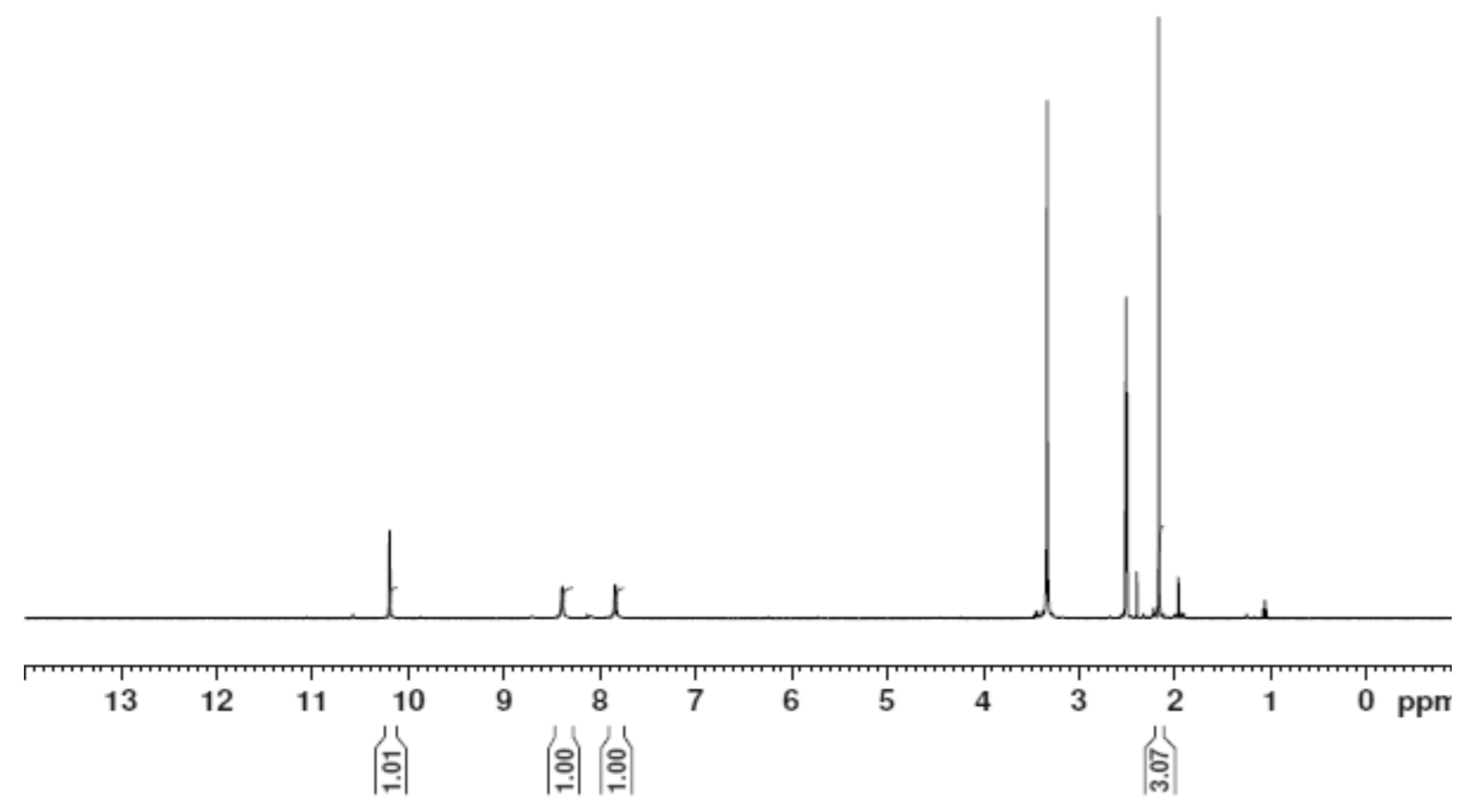

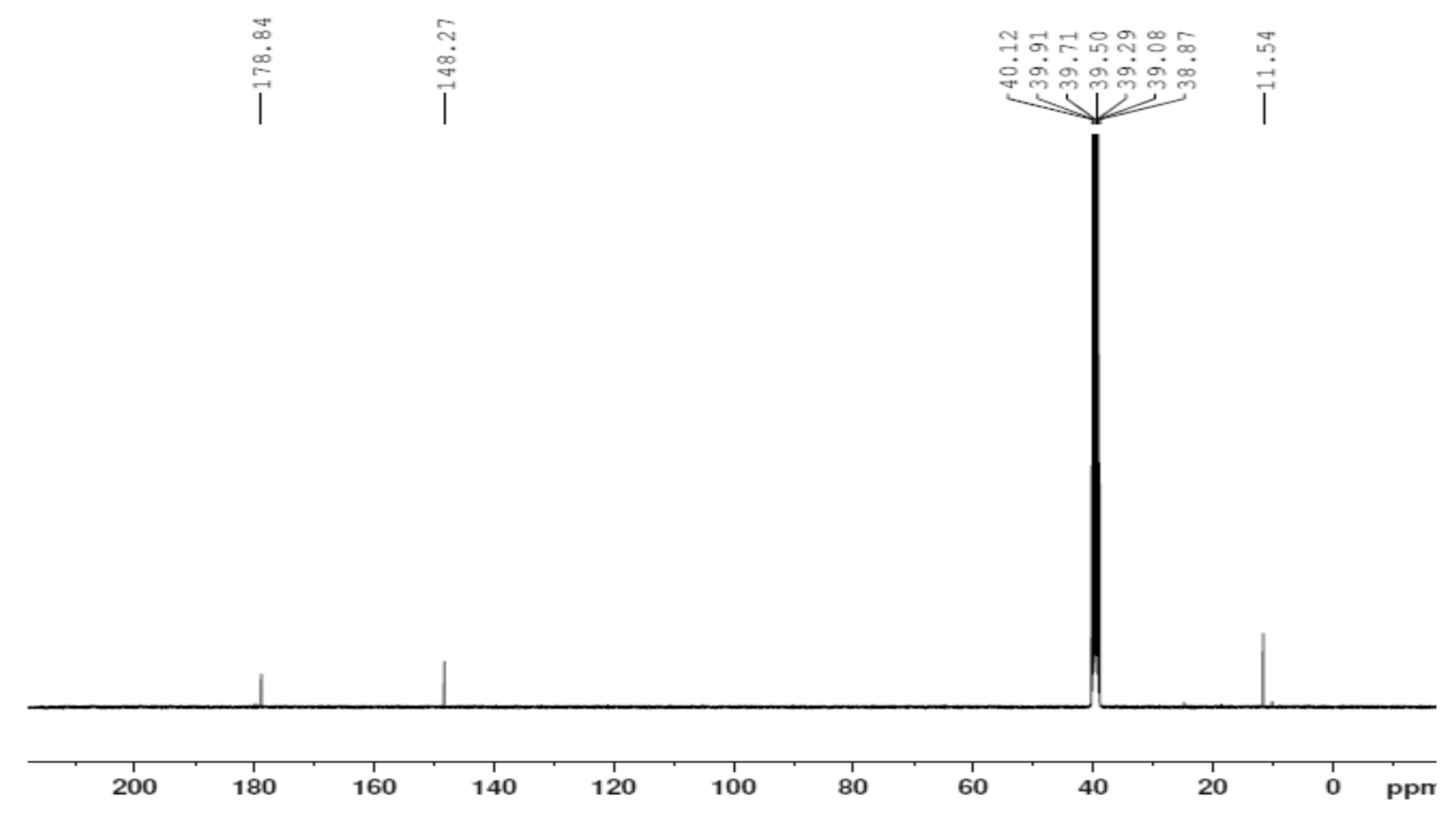

3.3. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H and 13C)

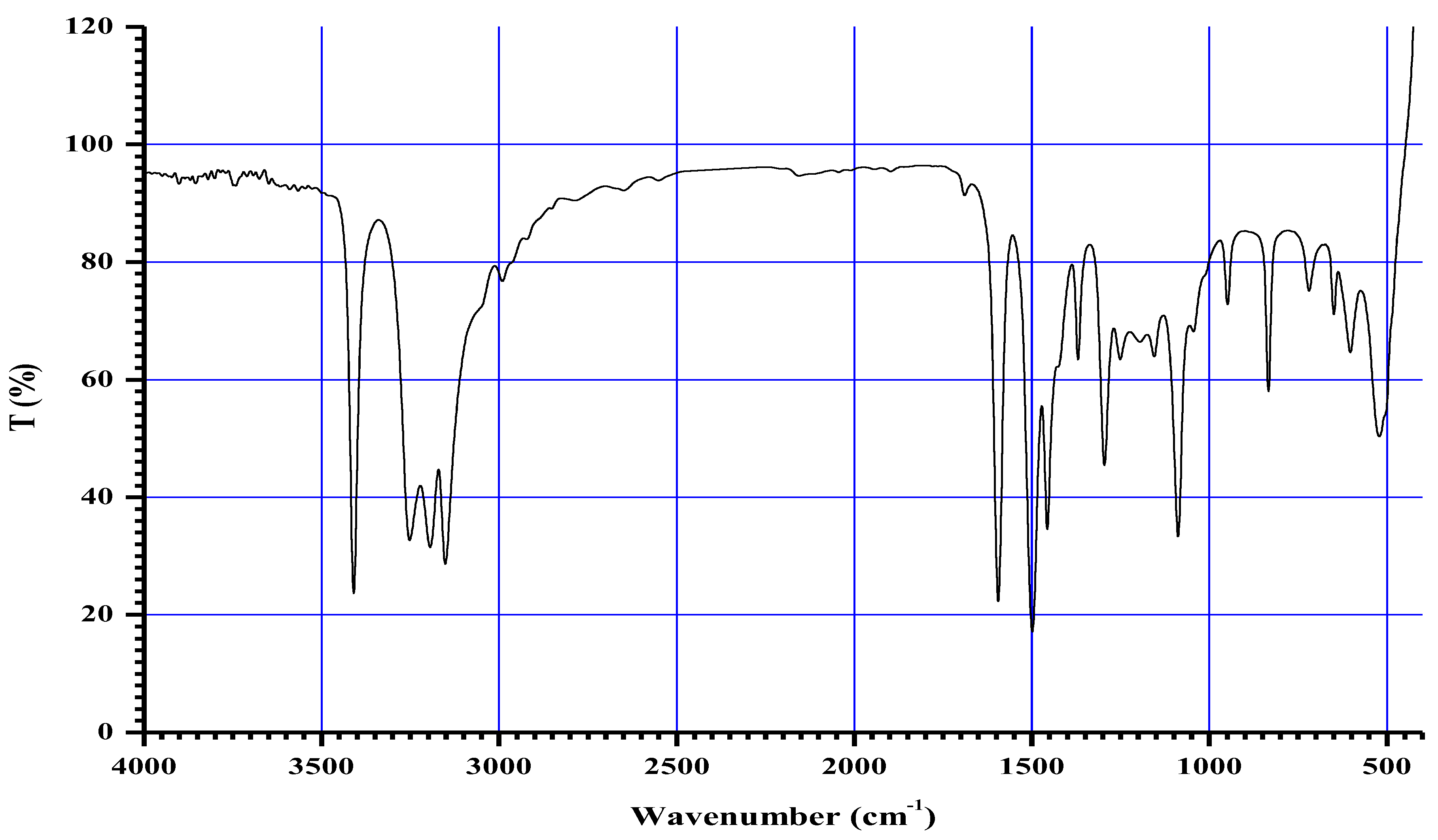

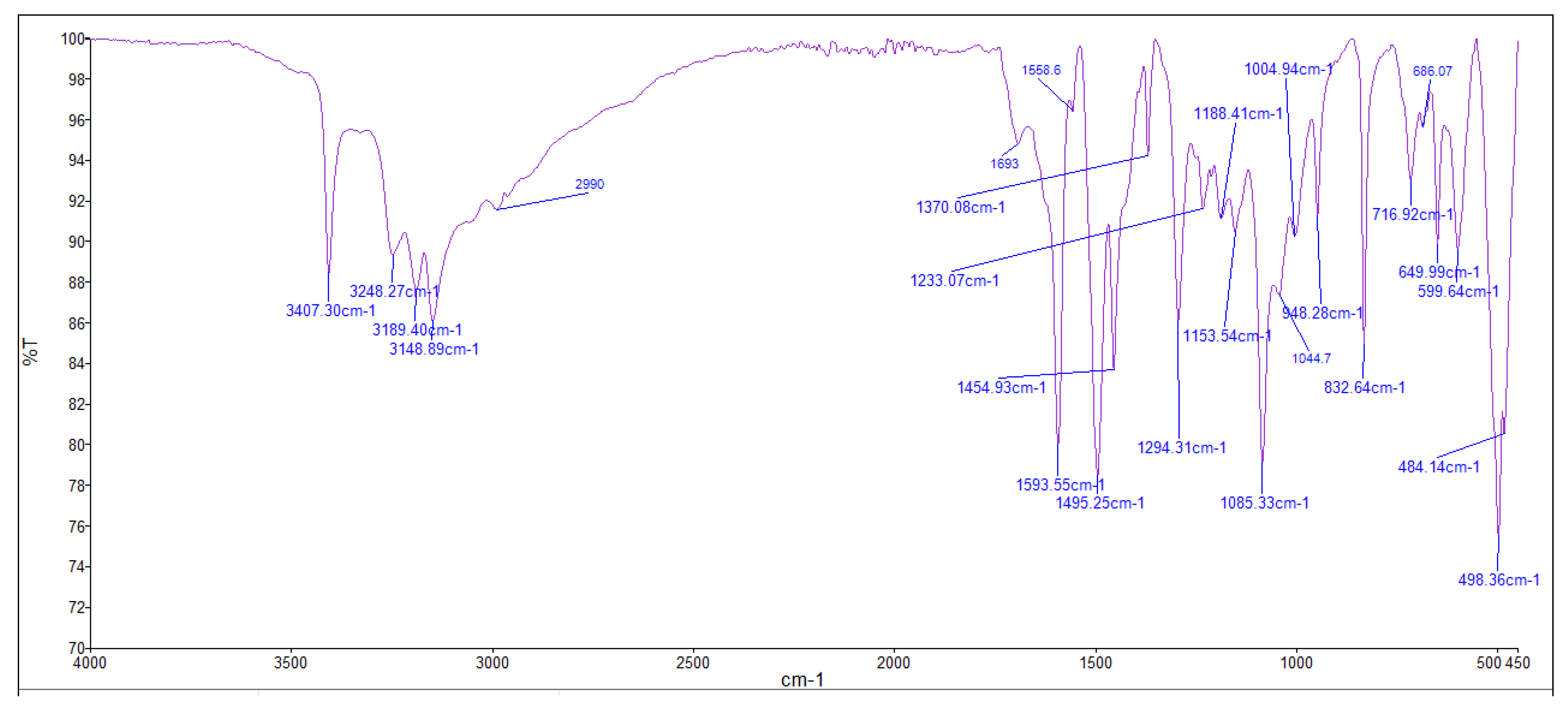

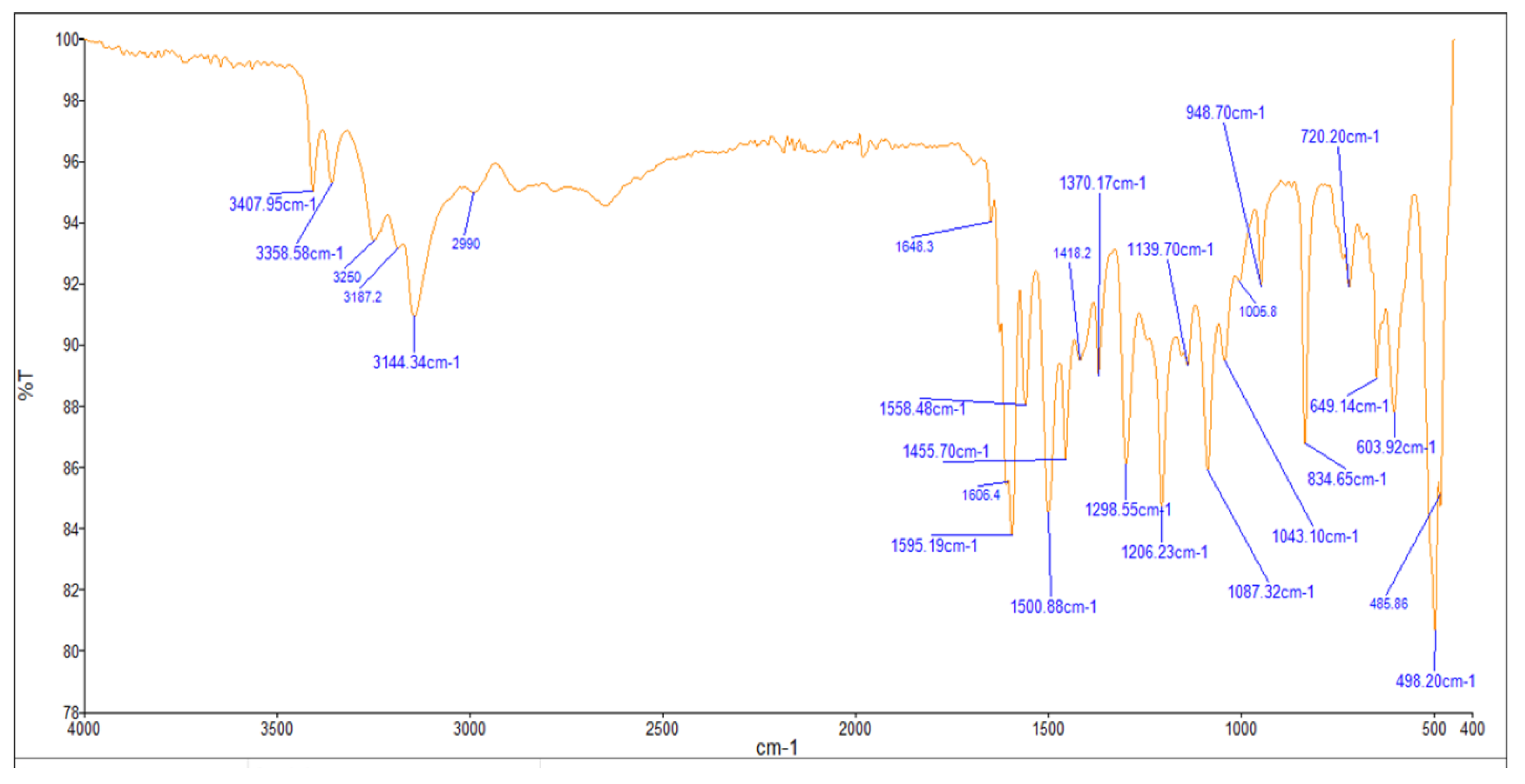

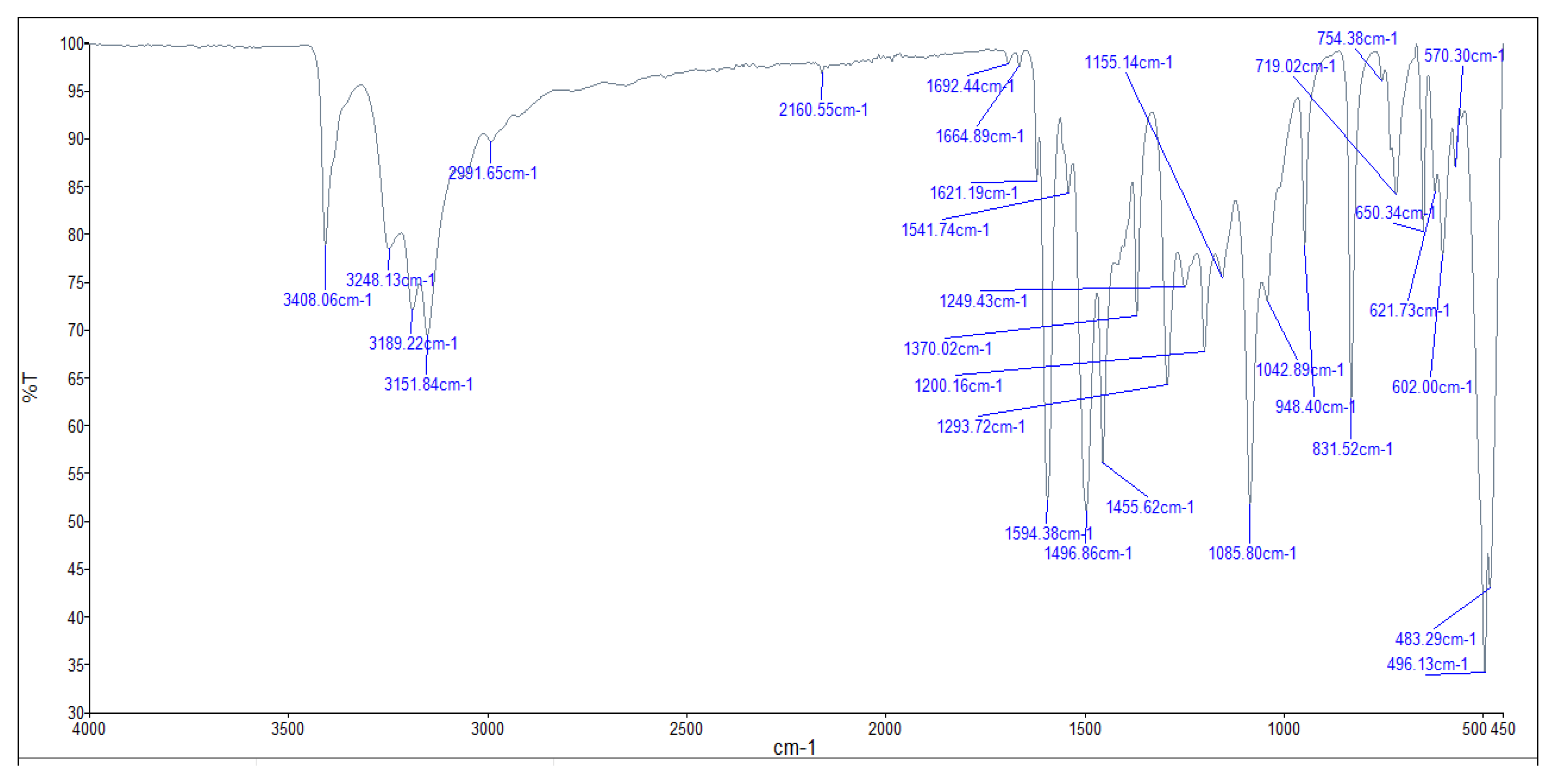

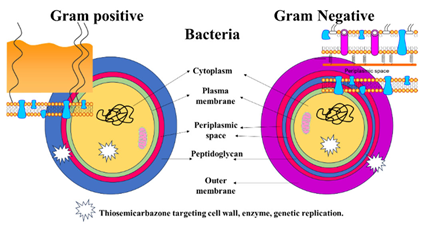

3.4. Infrared (FTIR) Spectra of Co, Cu, Zn Complexes

- i.

- The negative shift in position (4-30 cm-1) and intensity of the band of imine group C=N).[64]

- ii.

- The misplaced of the imine group ν(N-H6,7) band upon chelation, signifying that the thiosemicarbazone in these complexes interacted in the thio-enol form, that was endorsed by the appearing of new band in the region 1640-1690 cm-1, assignable to ν(C=N-N=C(.[64]

- iii.

- iv.

- The being of new bands at 451-476 and 497-519 cm-1 could be attributed to the ν(M-S) and ν(M←N) consecutively [66].

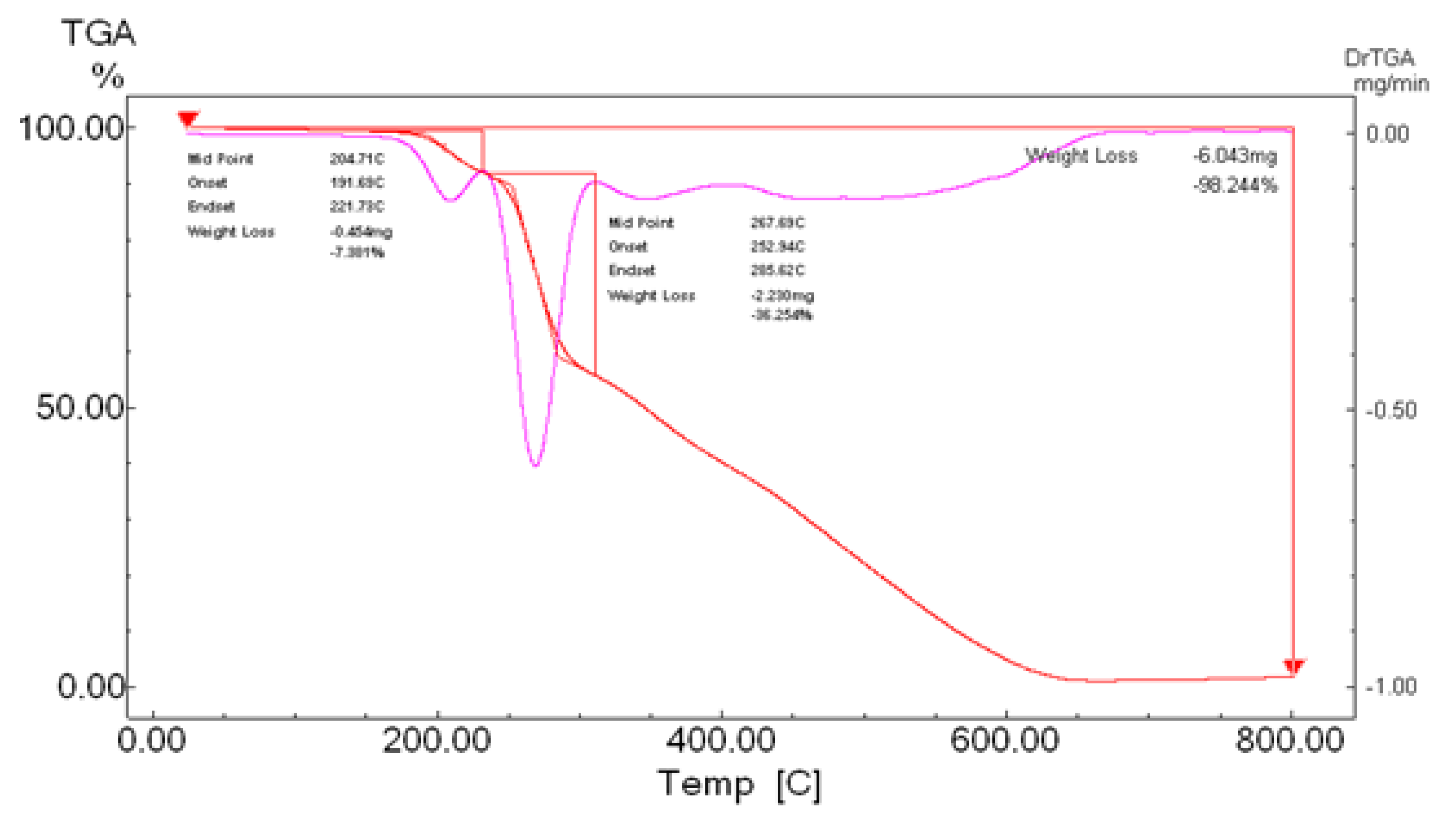

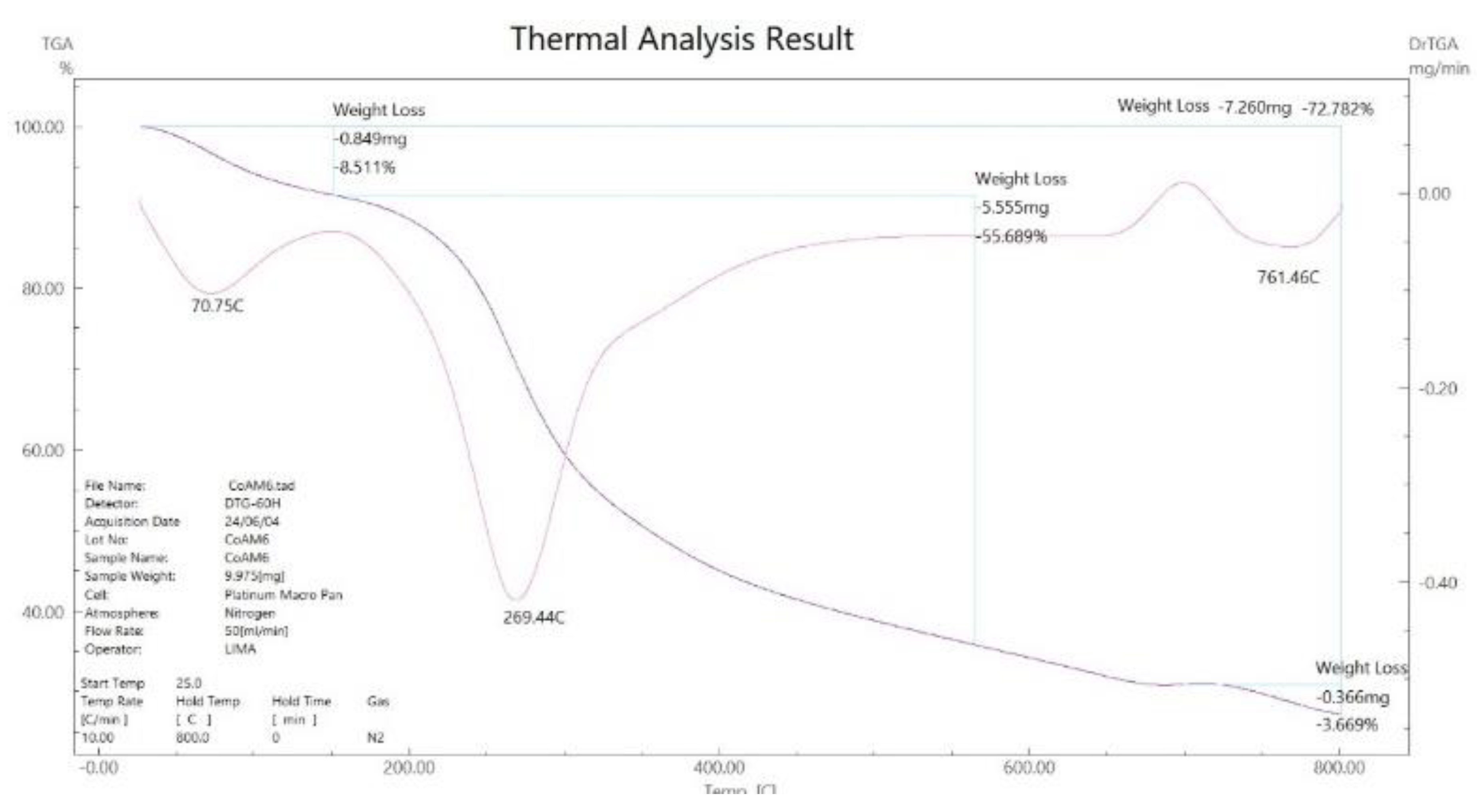

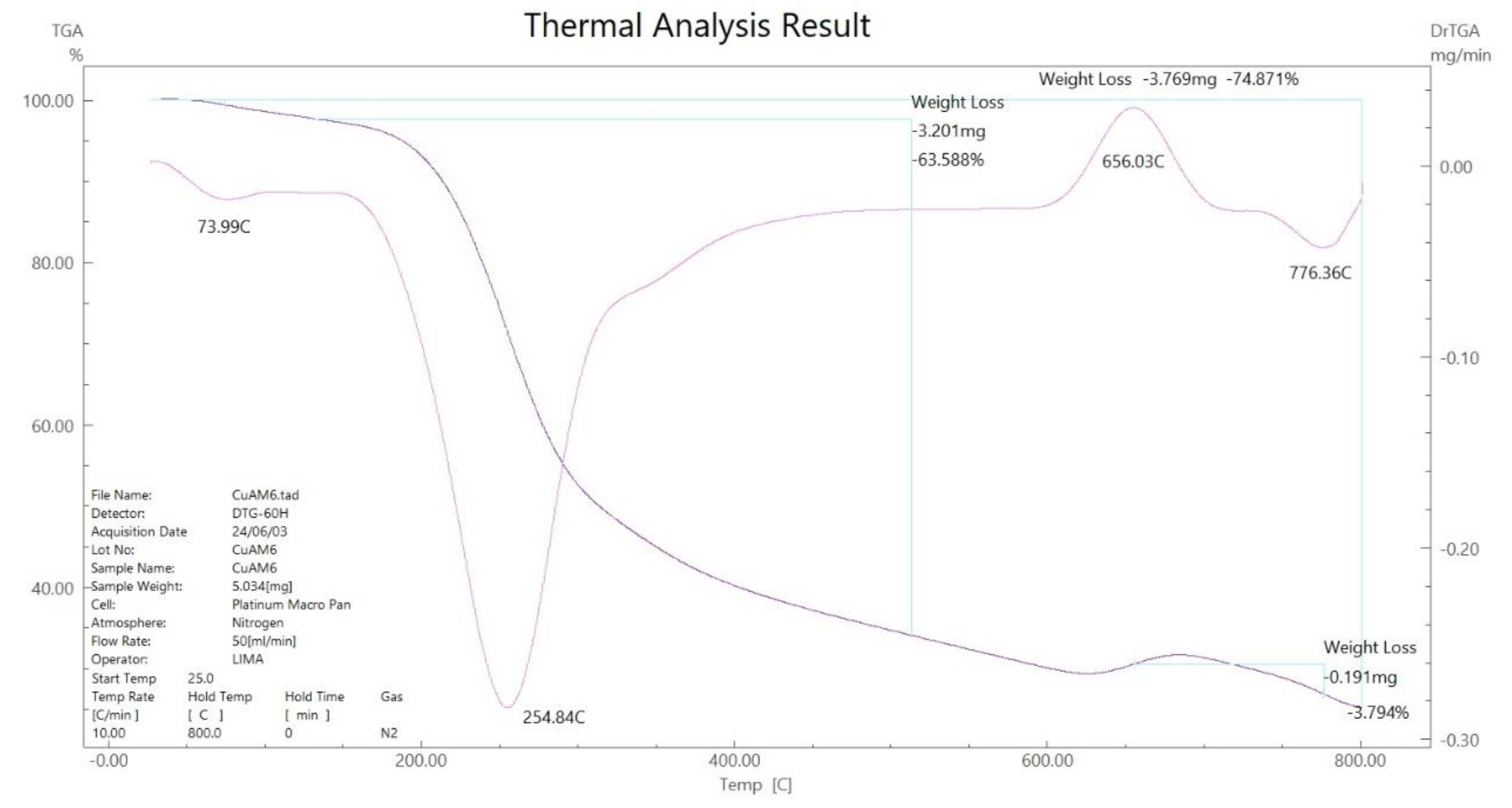

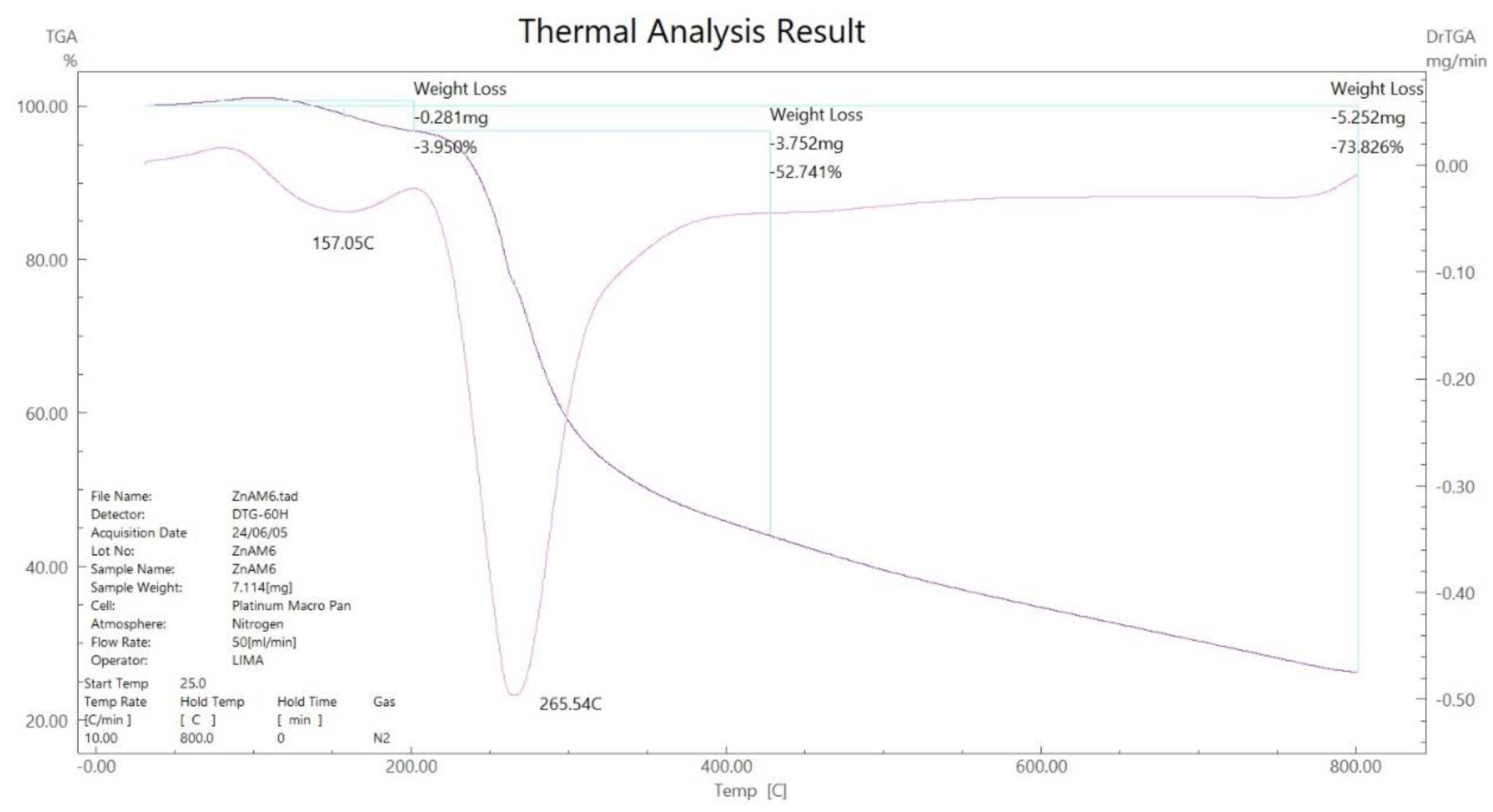

3.5. Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

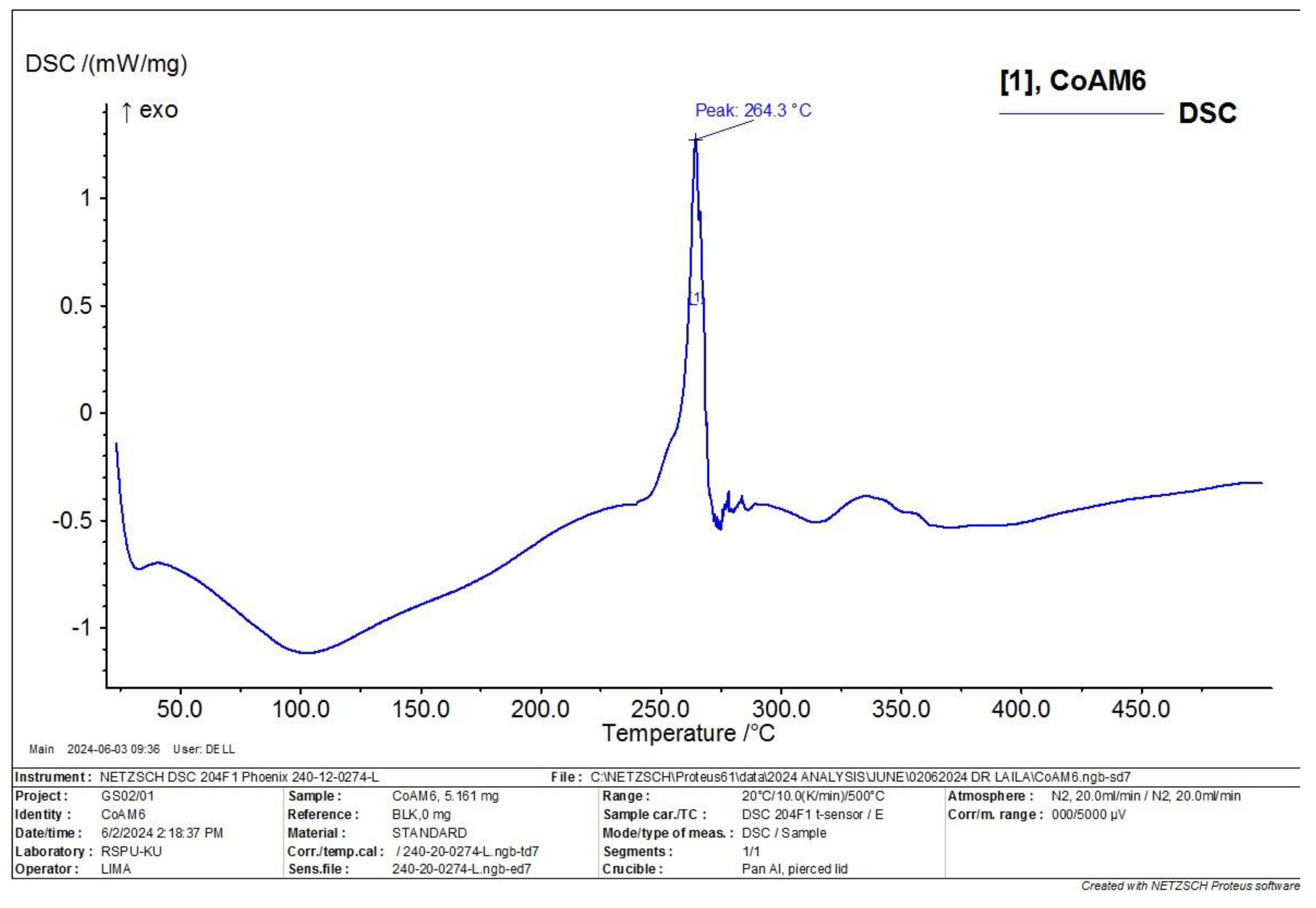

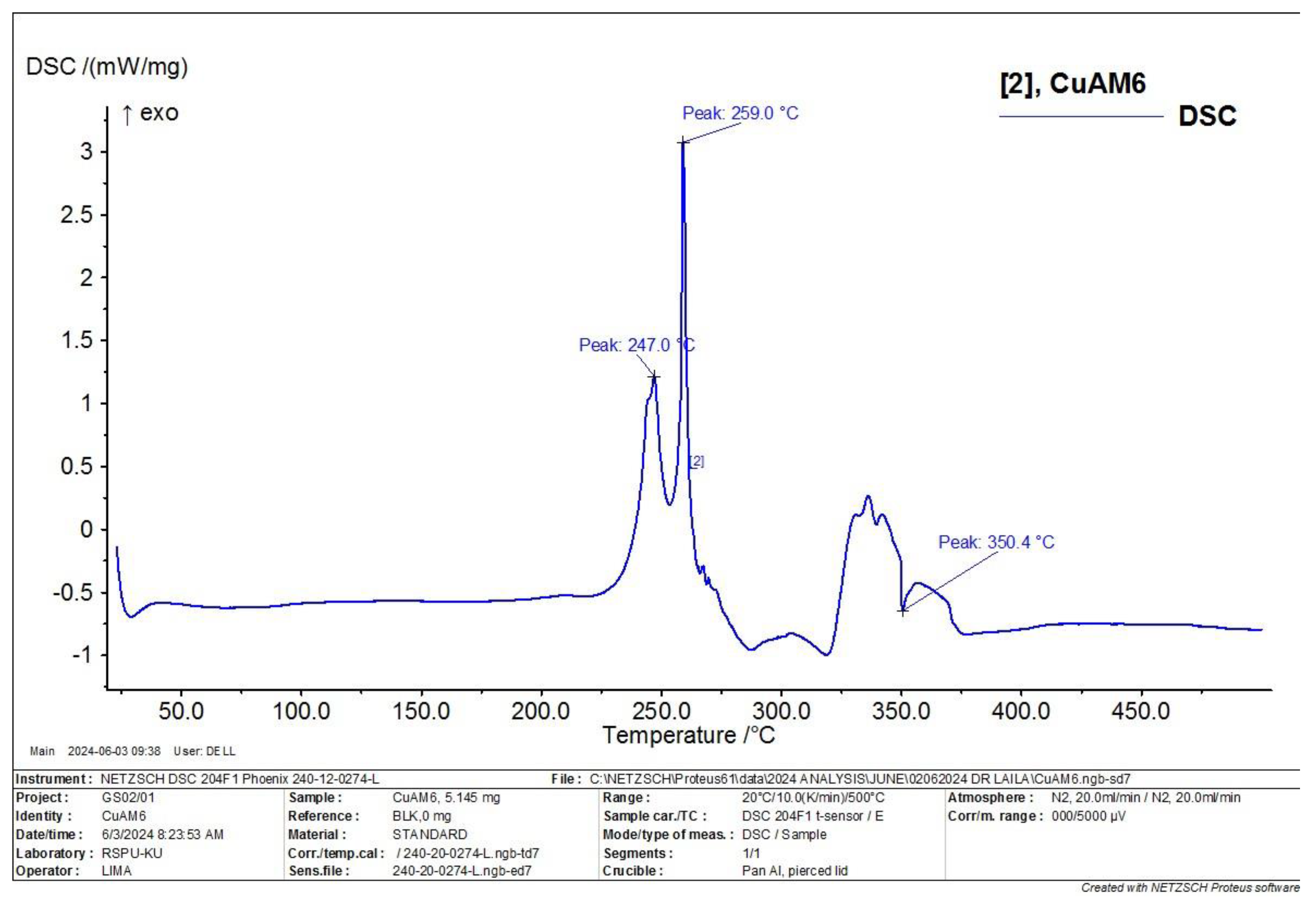

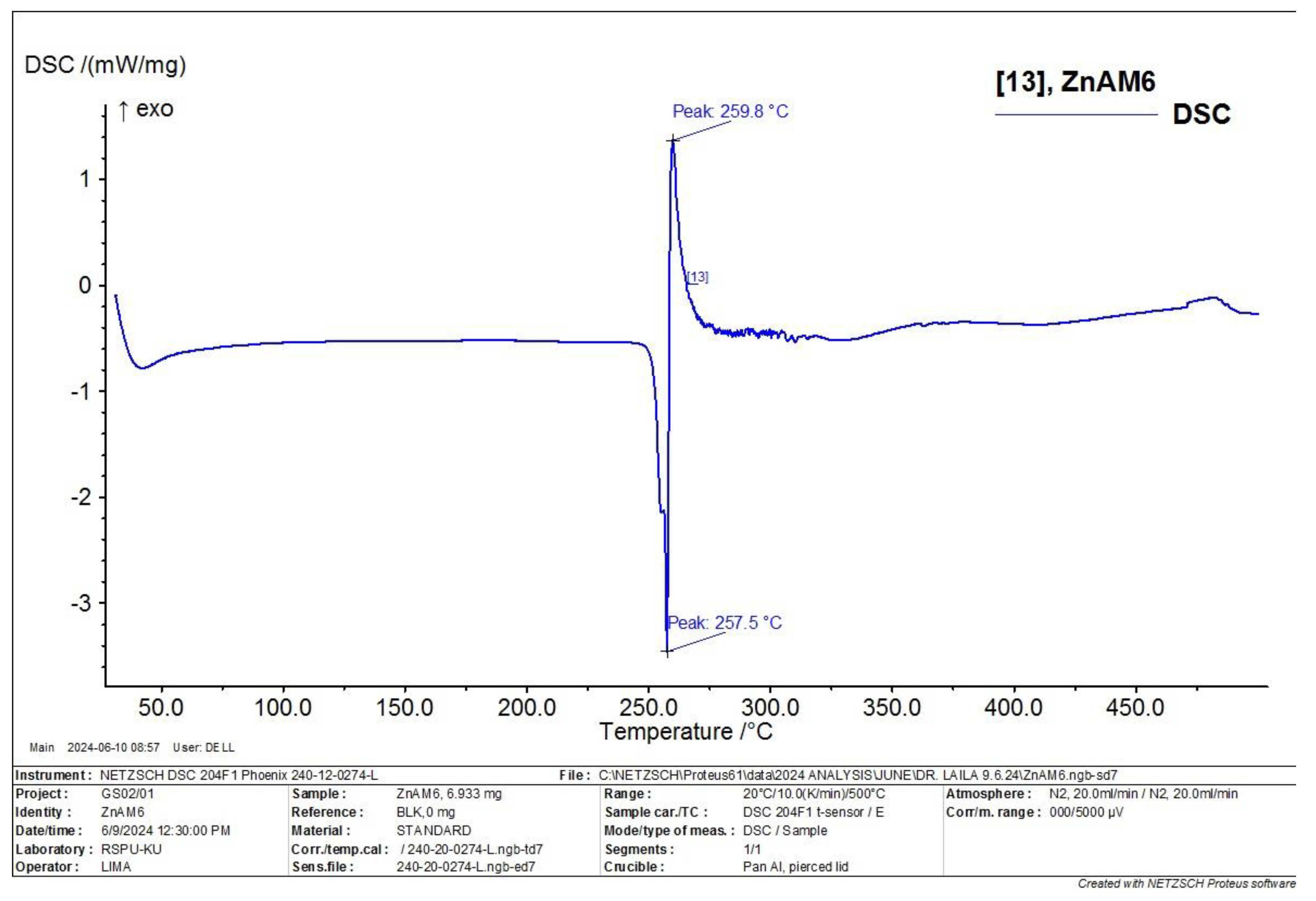

3.6. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Characterization

3.7. The Complexes’ Morphology Investigation by SEM

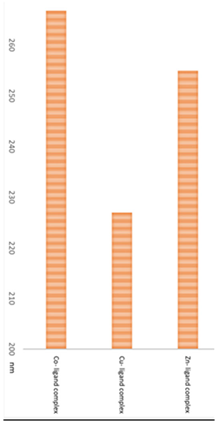

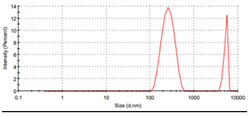

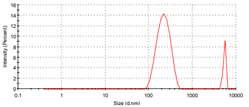

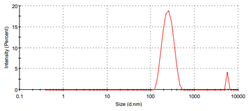

3.8. Particles Size Measurements of Metal Ligand Complexes

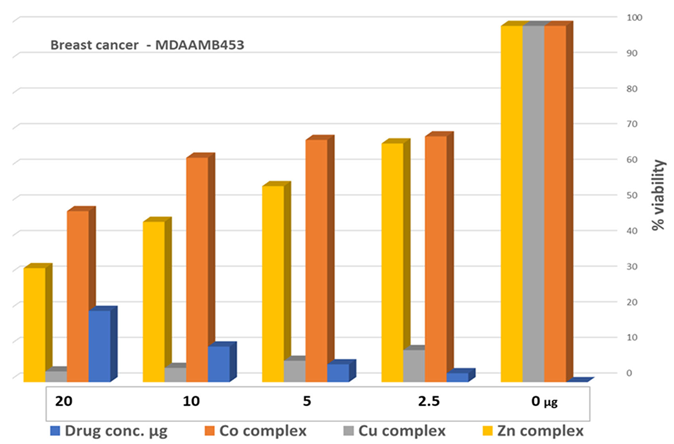

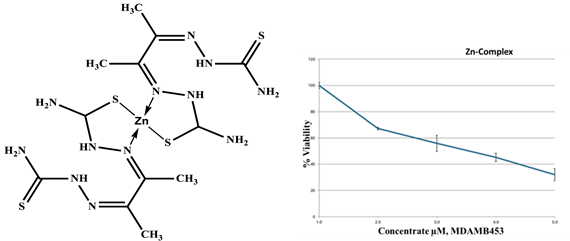

3.9. Cell Proliferation Assessments

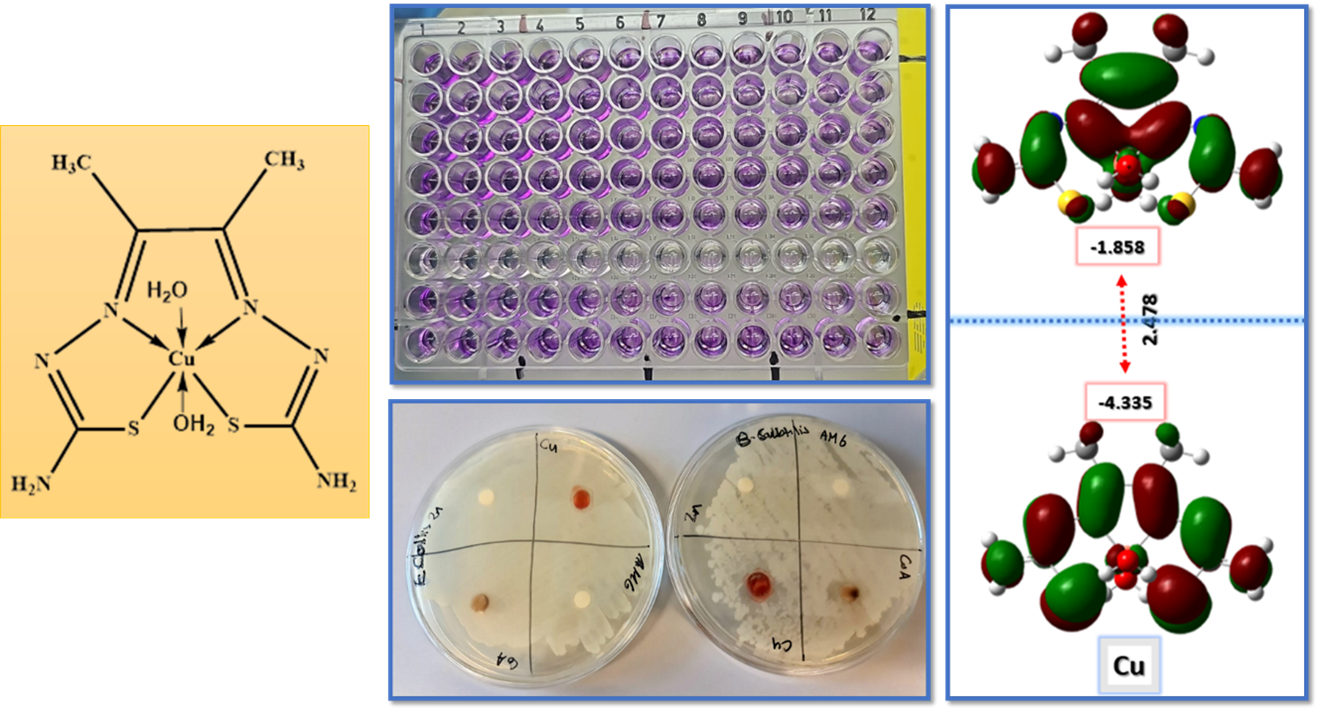

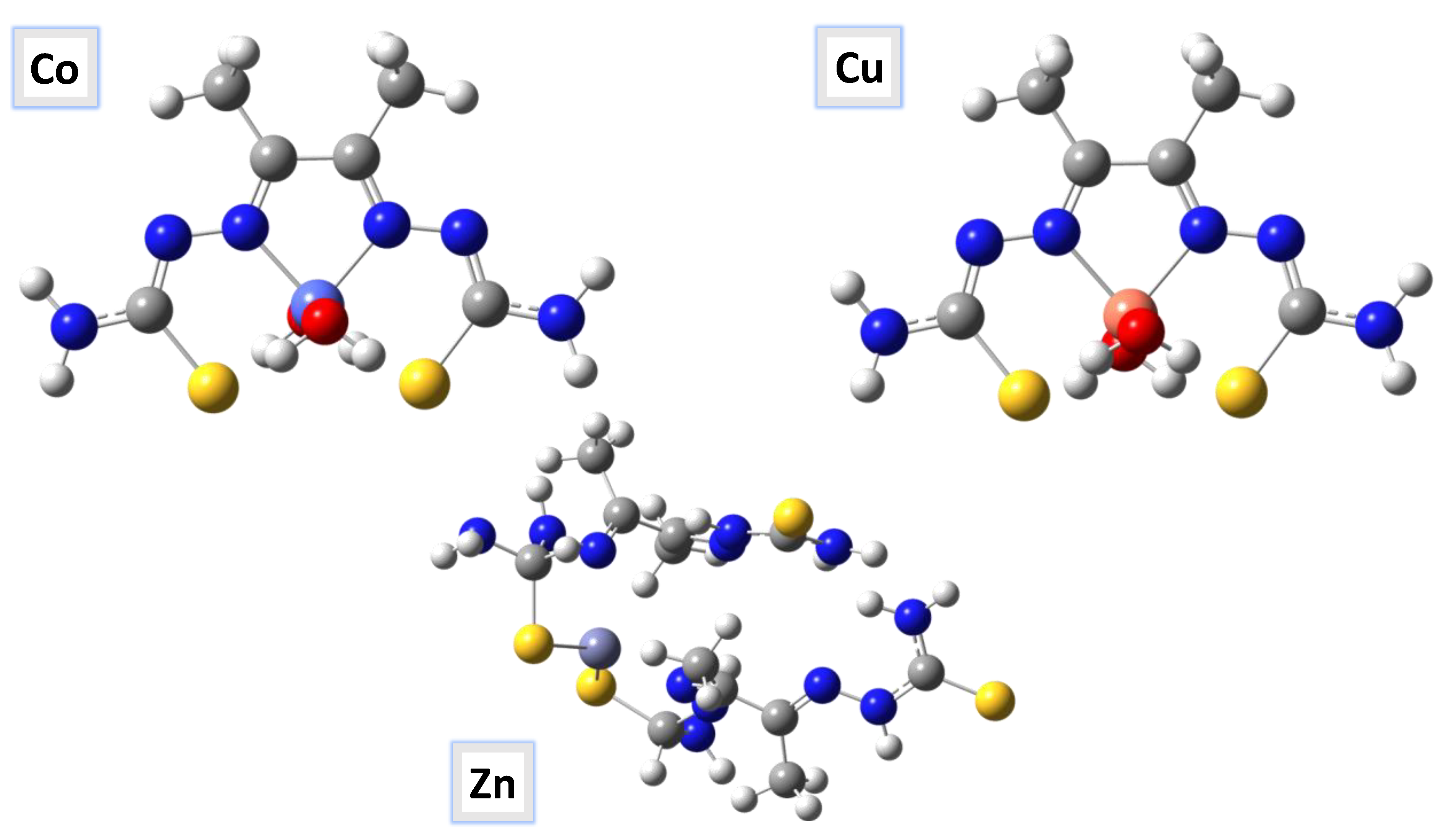

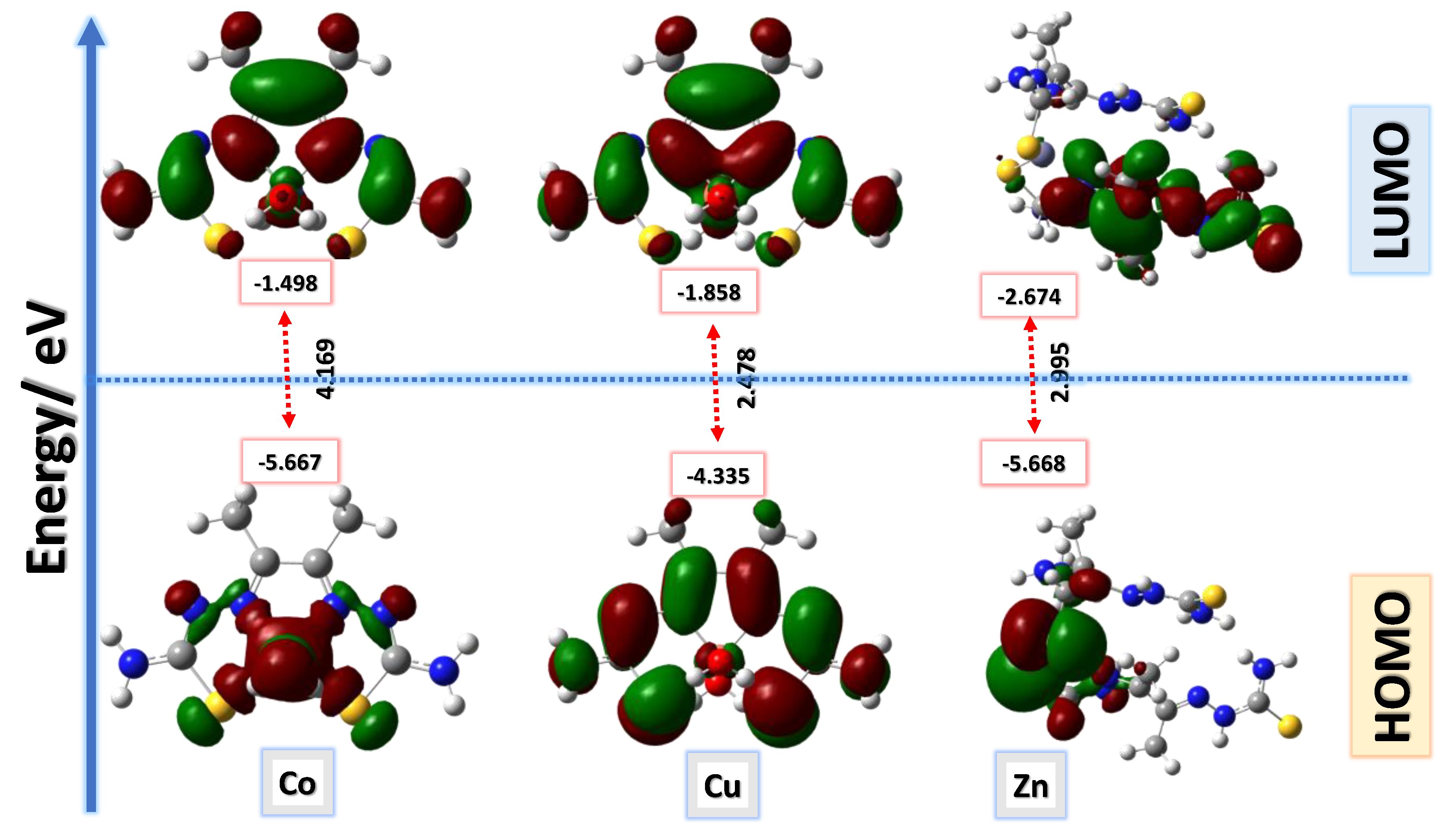

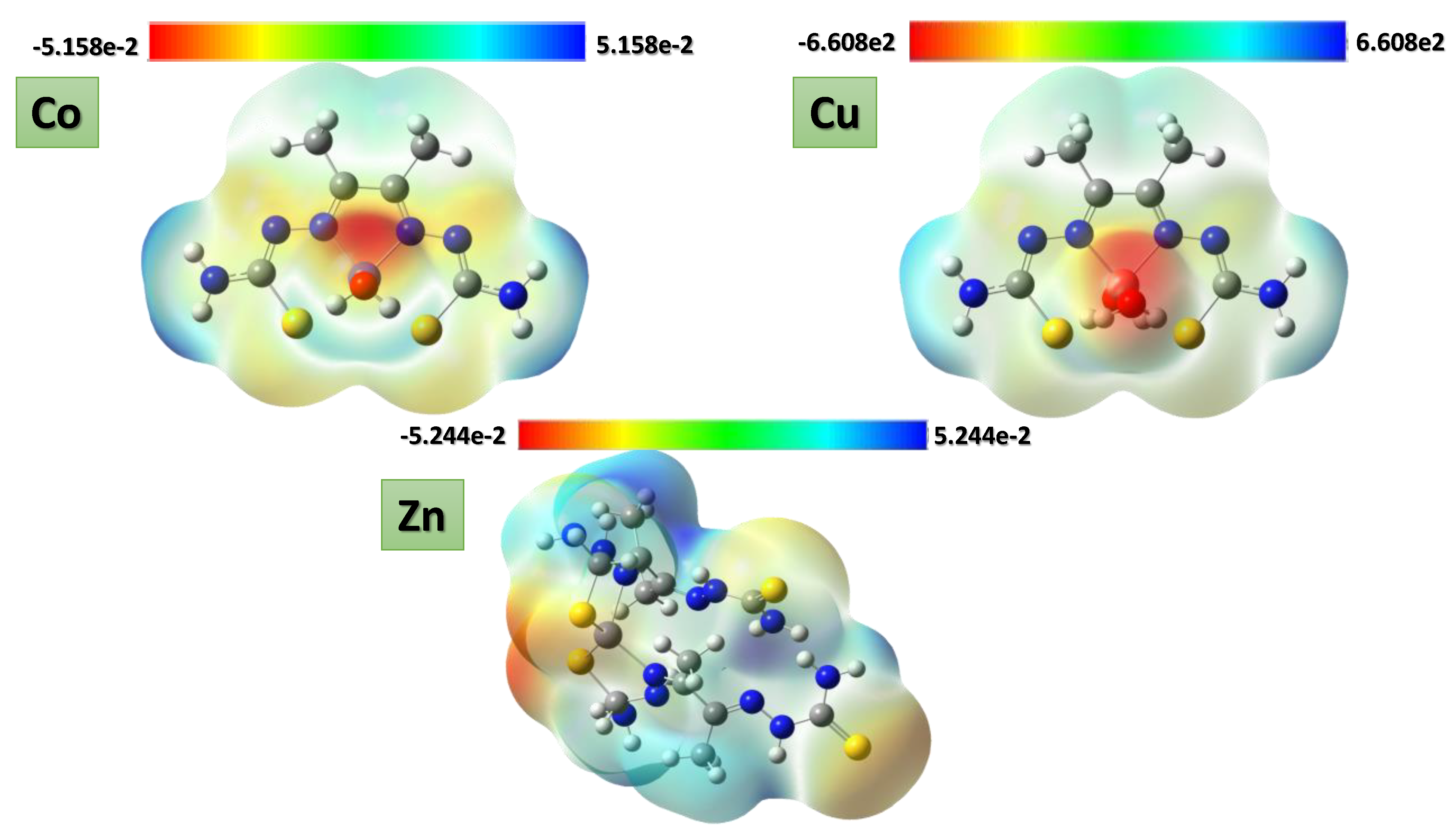

3.10. Computational Analysis of Optimized Geometry and Energy Gap

| ID | Etotal (Hartree) |

E* HOMO |

ELUMO | ΔE | I=-E HOMO | A=-E LUMO | η=(EHOMO-ELUMO)\2 |

S= 1\η |

µ=-(1+A)\2 |

X= (I+A)/2 |

|

Co-L complex |

-1175.560 | -5.667 | -1.498 | 4.169 | 5.667 | 1.498 | -2.084 | -0.480 | -1.249 | 3.582 |

|

Cu-L complex |

-1918.132 | -4.335 | -1.858 | 2.478 | 4.335 | 1.858 | -1.239 | -0.807 | -1.429 | 3.097 |

|

Zn-L complex |

-1762.038 | -5.668 | -2.674 | 2.995 | 5.668 | 2.674 | -1.497 | -0.668 | -1.837 | 4.171 |

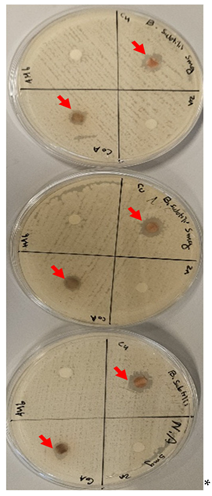

3.11. Antibacterial Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- .

- Karges J, Stokes RW, Cohen SM. (2021). Metal Complexes for Therapeutic Applications. Trends Chem. 3(7):523-534. [CrossRef]

- Klaudia Jomova, Marianna Makova, Suliman Y. Alomar, Saleh H. Alwasel, Eugenie Nepovimova, Kamil Kuca, Christopher J. Rhodes, Marian Valko. (2022). Essential metals in health and disease. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 367,110173. [CrossRef]

- Church DL. (2004). Major factors affecting the emergence and re-emergence of infectious diseases. Clin Lab Med. 24(3):559-86. [CrossRef]

- Van Crevel R, van de Vijver S, Moore DAJ. (2017). The global diabetes epidemic: what does it mean for infectious diseases in tropical countries? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 5(6):457-468.

- Ellis, T., Eze, E. & Raimi-Abraham, B.T. (2021). Malaria and Cancer: a critical review on the established associations and new perspectives. Infect Agents Cancer. 16,33. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Jing W, Kang L, Liu J, Liu M. (2021). Trends of the global, regional and national incidence of malaria in 204 countries from 1990 to 2019 and implications for malaria prevention. J Travel Med. 7,28(5). [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C., Divekar, S.D., Storchan, G.B. et al. (2013). Metals and Breast Cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 18,63–73. [CrossRef]

- Maret W. (2016). The Metals in the Biological Periodic System of the Elements: Concepts and Conjectures. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Jan 5,17(1):66. [CrossRef]

- Maria Antonietta Zoroddu, Jan Aaseth, Guido Crisponi, Serenella Medici, Massimiliano Peana, Valeria Marina Nurchi. (2019). The essential metals for humans: a brief overview, Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 195,120-129.

- Ejaz HW, Wang W, Lang M. (2020). Copper Toxicity Links to Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Therapeutics Approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 16,21(20):7660. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan SH, Liu JY, Sayes CM. (2023). Evaluating Manganese, Zinc, and Copper Metal Toxicity on SH-SY5Y Cells in Establishing an Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease Model. Int J Mol Sci. 24(22):16129. [CrossRef]

- Houtman JP. (1996). Trace elements and cardiovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Risk. 3(1):18-25.

- Górska A, Markiewicz-Gospodarek A, Trubalski M, Żerebiec M, Poleszak J, Markiewicz R. (2024). Assessment of the Impact of Trace Essential Metals on Cancer Development. Int J Mol Sci. 25(13):6842. [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund G, Dadar M, Pivina L, Doşa MD, Semenova Y, Aaseth J. (2020). The Role of Zinc and Copper in Insulin Resistance and Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Med Chem. 27(39):6643-6657. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; Freire, C.; De Castro, B. (2003). Synthesis and Characterization of Benzo-15-Crown-5 Ethers with Appended N2O Schiff Bases. Molecules. 8,894-900. [CrossRef]

- L.T. Yildirm, O. Atakol. Cryst. Res. Technol. (2002). Crystal structure analysis of Bis{(N,N′-dimethylformamide)-[μ-bis-N,N′-(2-oxybenzyl)-1,3-propanediaminato](μ- asetato) nickel(II)}nickel(II). Crystal Research and Technology 37(12):1352-1359.

- Tesauro D. (2022). Metal Complexes in Diagnosis and Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 23(8):4377.

- M. Hapke, G. Hilt. (2020). Introduction to cobalt chemistry and catalysis. Cobalt Catalysis in Organic Synthesis: Methods and Reactions. Wiley. 1-23.

- M. Valko, R. Klement, P. Pelikan, R. Boca, L. Dlhan, A. Bottcher, H. Elias, L. Muller. (1995). Copper (II) and Cobalt (II) complexes with derivatives of Salen and Tetrahydrosalen: an electron spin resonance, magnetic susceptibility, and quantum chemical study. J. Phys. Chem. 99,137-143. [CrossRef]

- Chang EL, Simmers C, Knight DA. (2010). Cobalt Complexes as Antiviral and Antibacterial Agents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 3(6):1711-1728. [CrossRef]

- Sopbué Fondjo, E., Songmi Feuze, S., Tamokou, JdD. et al. (2024). Synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial activity studies of two Co(II) complexes with 2-[(E)-(3-acetyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)diazenyl]-4-(2-hydroxyphenyl)thiophene-3-carboxylic acid as a ligand. BMC Chemistry. 18,75. [CrossRef]

- P. Kamalakannan, D. Venkappayya. (2002). Synthesis and characterization of cobalt and nickel chelates of 5-dimethylaminomethyl-2-thiouracil and their evaluation as antimicrobial and anticancer agents. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 90, (1-2):22-37. [CrossRef]

- W. Kaim, B. Schwederski. (1994). Bioinorganic Chemistry: Inorganic. lements in the Chemistry of Life. Wiley. 1-432.

- S.J. Lippard, J.M. Berg. (1994). Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry. University Science Books. Mill Valley. CA. 1-411.

- L. Virag, F. Erdodi, P. Gergely. (2016). Bioinorganic Chemistry for Medical Students. Scriptum. University of Debrecen. Hungary. 1-104.

- Simunkova M, Lauro P, Jomova K, Hudecova L, Danko M, Alwasel S, Alhazza IM, Rajcaniova S, Kozovska Z, Kucerova L, Moncol J, Svorc L, Valko M. (2019). Redox-cycling and intercalating properties of novel mixed copper (II) complexes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs tolfenamic, mefenamic and flufenamic acids and phenanthroline functionality: Structure, SOD-mimetic activity, interaction with albumin, DNA damage study and anticancer activity. J Inorg Biochem. 194:97-113. [CrossRef]

- Olar, R., Badea, M., Bacalum, M. et al. (2021). Antiproliferative and antibacterial properties of biocompatible copper (II) complexes bearing chelating N,N-heterocycle ligands and potential mechanisms of action. Biometals. 34,1155-1172. [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, W.; Castro, W.; González, S.; Madamet, M.; Amalvict, R.; Pradines, B.; Navarro, M. (2022). Copper (I)-Chloroquine Complexes: Interactions with DNA and Ferriprotoporphyrin, Inhibition of β-Hematin Formation and Relation to Antimalarial Activity. Pharmaceuticals. 15, 921. [CrossRef]

- J. Benters, U. Flogel, T. Schafer, D. Leibfritz, S. Hechtenberg, D. Beyersmann. (1997). Study of the interactions of cadmium and zinc ions with cellular alcium homoeostasis using 19F-NMR spectroscopy. Biochem. J. 322:793-799. [CrossRef]

- R. Ye, C. Tan, B. Chen, R. Li, Z. Mao. (2020). Zinc-containing metalloenzymes: inhibition by metal-based anticancer agents. Front. Chem. 8:402. [CrossRef]

- A.Klug, D. Rhodes. (1987). Zinc fingers: a novel protein fold for nucleic acid recognition. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 52:473-482. [CrossRef]

- Mousa, A.B., Moawad, R., Abdallah, Y. et al. (2023). Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Promise Anticancer and Antibacterial Activity in Ovarian Cancer. Pharm Res 40, 2281-2290. [CrossRef]

- Khashan, K.S., Sulaiman, G.M., Hussain, S.A. et al. (2020). Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation of Anti-bacterial, Anti-parasitic and Anti-cancer Activities of Aluminum-Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. J Inorg Organomet Polym.30, 3677-3693. [CrossRef]

- Bai XG, Zheng Y, Qi J. (2022). Advances in thiosemicarbazone metal complexes as anti-lung cancer agents. Front Pharmacol. 13:1018951. [CrossRef]

- Serda M, Kalinowski DS, Rasko N, Potůčková E, Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz A, Musiol R, Małecki JG, Sajewicz M, Ratuszna A, Muchowicz A, Gołąb J, Simůnek T, Richardson DR, Polanski J. (2014). Exploring the anti-cancer activity of novel thiosemicarbazones generated through the combination of retro-fragments: dissection of critical structure-activity relationships. PLoS One. 9(10):e110291. [CrossRef]

- Jaragh-Alhadad LA, Ali MS. (2022). Methoxybenzamide derivative of nimesulide from anti-fever to anti-cancer: Chemical characterization and cytotoxicity. Saudi Pharm J. 30(5):485-493. [CrossRef]

- Laila A. Jaragh-Alhadad, Gamaleldin I. Harisa, Fars K. Alanazi, (2022). Development of nimesulide analogs as a dual inhibitor targeting tubulin and HSP27 for treatment of female cancers. Journal of Molecular Structure. 1248:131479.

- Laila A. Jaragh-Alhadad and Mayada S. Ali. (2022). Nimesulide derivatives reduced cell proliferation against breast and ovarian cancer: synthesis, characterization, biological assessment, and crystal structure. Kuwait J.Sci. 49(3):1-17.

- Laila Jaragh-Alhadada,b, Haider Behbehania and Sadashiva Karnik, (2022). Cancer targeted drug delivery using active low-density lipoprotein nanoparticles encapsulated pyrimidines heterocyclic anticancer agents as microtubule inhibitors. Drug Delivery. 29:1, 2759-2772. [CrossRef]

- Laila A. Jaragh-Alhadad, Mayada S. Ali, Moustafa S. Moustafa, Gamaleldin I. Harisa, Fars K. Alanazi, Sadashiva Karnik. (2022). Sulfonamide derivatives mediate breast and lung cancer cell line killing through tubulin inhibition. Journal of Molecular Structure. 1268:133699.

- Jaragh-Alhadad L, Samir M, Harford TJ, Karnik S. (2022). Low-density lipoprotein encapsulated thiosemicarbazone metal complexes is active targeting vehicle for breast, lung, and prostate cancers. Drug Delivery. 29(1):2206-2216. [CrossRef]

- Mayada S. Ali, Fathy A. El-Saied, Mohamad ME. Shakdofa, Sadashiva Karnik, Laila A. Jaragh-Alhadad. (2023). Synthesis and characterization of thiosemicarbazone metal complexes: Crystal structure, and antiproliferation activity against breast (MCF7) and lung (A549) cancers. Journal of Molecular Structure. 1274(1):13448.

- Vázquez-Valadez Víctor Hugo, Hernández-S. Manuel Alejandro, Velázquez-S. Ana María, Rosales-H. María, Leyva-R. Marco Antonio, Prado-O. María Guadalupe, Muñoz-G. Marco Antonio, Alba-H. Fernando, Abrego Víctor, Cruz-A. Diego, Ángeles Enrique (2018). Molecular Modeling and Synthesis of Ethyl Benzyl Carbamates as Possible Ixodicide Activity. Computational Chemistry. 7(1).

- Andersson, M. P.; Uvdal, P., (2005). New Scale Factors for Harmonic Vibrational Frequencies Using the B3LYP Density Functional Method with the Triple-ζ Basis Set 6-311+G(d,p). The Journal of Physical Chemistry A . 109(12):2937-2941. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A. R.; Dongre, R. S.; Almalki, F. A.; Berredjem, M.; Aissaoui, M.; Touzani, R.; Hadda, T. B.; Akhter, M. S., (2021). Synthesis, biological activity and POM/DFT/docking analyses of annulated pyrano [2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives: Identification of antibacterial and antitumor pharmacophore sites. Bioorganic Chemistry. 106,104480. [CrossRef]

- Guerfi, M.; Berredjem, M.; Bahadi, R.; Djouad, S.-E.; Bouzina, A.; Aissaoui, M., (2021). An efficient synthesis, characterization, DFT study and molecular docking of novel sulfonylcycloureas. Journal of Molecular Structure. 1236,130327.

- Mounyr, B.; Moulay, S.; saad, K.I. (2015). Methods for invitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J Pharm Anal. 6(2):71-79.

- Mayada S. Ali, Dhanachandra Kuraijam, Sadashiva Karnik, Laila A. Jaragh-Alhadad. (2023). Hydrazone bimetallic complex: synthesis, characterization, in silico and biological evaluation targeting breast and lung cancer cells’ G-quadruplex DNA. Kuwait J.Sci.. 50,(3):1-17.

- M. M. E. Shakdofa, H. A. Mousa, A. M. A. Elseidy, A. A. Labib, M. M. Ali, A. S. Abd-El-All, Appl. (2018). Synthesis, characterization, and density functional theory studies of hydrazone–oxime ligand derived from 2,4,6-trichlorophenyl hydrazine and its metal complexes searching for new antimicrobial drugs. Organomet. Chem. 32,e3936.

- A.Sethukumar, C. U. Kumar, R. Agilandeshwari, B. A. Prakasam, J. Mol. Struct. (2013). Synthesis, stereochemical, structural and biological studies of some 2, 6-diarylpiperidin-4-one N (4′)-cyclohexyl thiosemicarbazones. 1047,237. [CrossRef]

- F. P. Andrew, P. A. Ajibade, (2018). Synthesis, characterization and anticancer studies of bis(1-phenylpiperazine dithiocarbamato) Cu(II), Zn(II) and Pt(II) complexes: Crystal structures of 1-phenylpiperazine dithiocarbamato-S,S′ zinc(II) and Pt(II). J. Mol. Struct. 1170,24.

- S. M. Emam, I. E. T. El Sayed, M. I. Ayad, H. M. R. Hathout. (2017). Synthesis, characterization and anticancer activity of new Schiff bases bearing neocryptolepine. J. Mol. Struct. 1146,600.

- S. Chandra, S. Bargujar, R. Nirwal, N. Yadav, Spectrochim. (2013). Synthesis, spectral characterization and biological evaluation of copper(II) and nickel(II) complexes with thiosemicarbazones derived from a bidentate Schiff base. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 106,91. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Saghatforoush, S. Hosseinpour, M. W. Bezpalko, W. S. Kassel. (2019). Synthesis, spectroscopic studies and X-ray structure determination of two mononuclear copper complexes derived from the Schiff base ligand N,N-dimethyl-N’-((5-methyl-1H-imidazol-4-yl)methylene)ethane-1,2-diamine. Inorg. Chim. Act. 484,527.

- E. Shahsavani, A. D. Khalaji, N. Feizi, M. Kučeráková, M. Dušek. (2015). Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure and antibacterial activity of new sulfur-bridged dinuclear silver(I) thiosemicarbazone complex [Ag2(PPh3)2(μ-S-Brcatsc)2(η1-S-Brcatsc)2](NO3)2. Inorg. Chim. Act. 429,61.

- N. M. Rageh, A. M. A. Mawgoud, H. M. Mostafa. (1999). Transition Metal Complexes Derived From 2-hydroxy-4-(p-tolyldiazenyl)benzylidene)-2-(p-tolylamino)acetohydrazide Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Biological Activities. Chem. Pap. 53,107.

- A.B. P. Lever. (1969). ’Inorganic electronic spectroscopy’. Elsevier science. 46(9).

- Sethukumar, C. Udhaya Kumar, R. Agilandeshwari, B. Arul Prakasam. (2013). Synthesis, stereochemical, structural and biological studies of some 2,6-diarylpiperidin-4-one N(4′)-cyclohexyl thiosemicarbazones. J. Mol. Struct. 1047, 37.

- Şen, B. (2021). 2-Acetyl-5-chloro-thiophene thiosemicarbazone and its nickel(II) and zinc(II) complexes: Hirshfeld surface analysis and Density Functional Theory calculations for molecular geometry, vibrational spectra and HOMO-LUMO studies. Turkish Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 5(1):27-38.

- Gaber, M., El-Ghamry, H.A and Mansour, M.A. (2018). Pd (II) and Pt (II) chalcone complexes. Synthesis, spectral characterization, molecular modeling, biomolecular docking, antimicrobial and antitumor activities. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry. 354, pp. 163-174. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Ilies, E. Pahontu, S. Shova, R. Georgescu, N. Stanica, R. Olar, A. Gulea, T. Rosu. (2014). Synthesis, structure and biological properties of a series of dicopper(bis-thiosemicarbazone) complexes. Polyhedron. 81,123.

- Vijayan, P., Vijayapritha, S., Ruba, C. et al. (2019). Ruthenium(II) carbonyl complexes containing thiourea ligand: Enhancing the biological assets through biomolecules interaction and enzyme mimetic activities. Monatsh Chem 150, 1059–1071.

- Şen, H. K. Kalhan, V. Demir, E. E. Güler, H. A. Kayalı, E. Subaşı, Mater. (2019). Crystal structures, spectroscopic properties of new cobalt(II), nickel(II), zinc(II) and palladium(II) complexes derived from 2-acetyl-5-chloro thiophene thiosemicarbazone: Anticancer evaluation. Sci. Eng. C. 98,550. [CrossRef]

- Z. Piri, Z. Moradi–Shoeili, A. Assoud. (2019). Ultrasonic assisted synthesis, crystallographic, spectroscopic studies and biological activity of three new Zn(II), Co(II) and Ni(II) thiosemicarbazone complexes as precursors for nano-metal oxides. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 484,338. [CrossRef]

- A.Akbari, H. Ghateazadeh, R. Takjoo, B. Sadeghi-Nejad, M. Mehrvar, J. T. Mague. (2019). Synthesis & crystal structures of four new biochemical active Ni(II) complexes of thiosemicarbazone and isothiosemicarbazone-based ligands: In vitro antimicrobial study. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1181, 287. [CrossRef]

- Chehelgerdi M, Chehelgerdi M, Allela OQB, Pecho RDC, Jayasankar N, Rao DP, Thamaraikani T, Vasanthan M, Viktor P, Lakshmaiya N, Saadh MJ, Amajd A, Abo-Zaid MA, Castillo-Acobo RY, Ismail AH, Amin AH, Akhavan-Sigari R. (2023). Progressing nanotechnology to improve targeted cancer treatment: overcoming hurdles in its clinical implementation. Mol Cancer. 22(1):169.

- Hembram KC, Kumar R, Kandha L, Parhi PK, Kundu CN, Bindhani BK. Therapeutic prospective of plant-induced silver nanoparticles: application as antimicrobial and anticancer agent. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46(sup3):S38-S51. [CrossRef]

- Bisht G, Rayamajhi S. (2016). ZnO Nanoparticles: A Promising Anticancer Agent. Nanobiomedicine (Rij). 1;3:9.

- Arshad F, Naikoo GA, Hassan IU, Chava SR, El-Tanani M, Aljabali AA, Tambuwala MM. (2024). Bioinspired and Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles for Medical Applications: A Green Perspective. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 196(6):3636-3669.

- Jaragh-Alhadad LA, Falahati M. (2022). Tin oxide nanoparticles trigger the formation of amyloid β oligomers/protofibrils and underlying neurotoxicity as a marker of Alzheimer’s diseases. Int J Biol Macromol. 204:154-160.

- Jaragh-Alhadad LA, Falahati M. (2022). Copper oxide nanoparticles promote amyloid-β-triggered neurotoxicity through formation of oligomeric species as a prelude to Alzheimer’s diseases. Int J Biol Macromol. 207:121-129.

- Zheng Nie, Yasaman Vahdani, William C. Cho, Samir Haj Bloukh, Zehra Edis, Setareh Haghighat, Mojtaba Falahati, Rasoul Kheradmandi, Laila Abdulmohsen Jaragh-Alhadad, Majid Sharifi. (2022). 5-Fluorouracil-containing inorganic iron oxide/platinum nanozymes with dual drug delivery and enzyme-like activity for the treatment of breast cancer. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 15(8):103966.

- Rümenapp, C., Gleich, B. & Haase, A. (2012). Magnetic Nanoparticles in Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Diagnostics. Pharm Res. 29,1165–1179.

- Hoda F. El-Shafiy, M. Saif, Mahmoud M. Mashaly, Shimaa Abdel Halim, Mohamed F. Eid, A.I. Nabeel, R. Fouad. (2017). New nano-complexes of Zn(II), Cu(II), Ni(II) and Co(II) ions; spectroscopy, thermal, structural analysis, DFT calculations and antimicrobial activity application. Journal of Molecular Structure. 1147, 452-461. [CrossRef]

- M. Imran, L. Mitu, S. Latif, Z. Mahmood, I. Naimat, S.S. Zaman, S. Fatima. (2010). antibacterial Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes with biacetyl-derived Schiff bases. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 75:1075-1084.

- Jain, S., Rana, M., Sultana, R., Mehandi, R., & Rahisuddin. (2022). Schiff Base Metal Complexes as Antimicrobial and Anticancer Agents. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 43(7), 6351–6406. [CrossRef]

- Gai S, He L, He M, Zhong X, Jiang C, Qin Y, Jiang M. (2023). Anticancer Activity and Mode of Action of Cu(II), Zn(II), and Mn(II) Complexes with 5-Chloro-2-N-(2-quinolylmethylene)aminophenol. Molecules. 28(12):4876.

- S. Rafique, M. Idrees, A. Nasim, H. Akbar, A. Athar. (2010). Transition metal complexes as potential therapeutic agents. Biotech. Mol. Biol. Rev. 5:38-45.

- Agnieszka Dziewulska-Kułaczkowska, Liliana Mazur (2011). Structural studies and characterization of 3-formylchromone and products of its reactions with chosen primary aromatic amines. J. Mol. Struct. 985:233-242.

- M. Saif, Hoda F. El-Shafiy, Mahmoud M. Mashaly, Mohamed F. Eid, A.I. Nabeel, R. Fouad. (2016). Synthesis, characterization, and antioxidant/cytotoxic activity of new chromone Schiff base nano-complexes of Zn(II), Cu(II), Ni(II) and Co(II). Journal of Molecular Structure. 1118:75-82. [CrossRef]

- Kotova, K. Lyssenko, A. Rogachev, S. Eliseeva, I. Fedyanin, L. Lepnev, L. Pandey, A. Burlov, A. Garnovskii, A. Vitukhnovsky, M.V.D. Auweraer, N. Kuzmin, Photochem. Photobiol. (2011). Low temperature X-ray diffraction analysis, electronic density distribution and photophysical properties of bidentate N,O-donor salicylaldehyde Schiff bases and zinc complexes in solid state. A Chem. 218:117-129. [CrossRef]

- V. Chiş, S. Filip, V. Miclăuş, A. Pîrnău, C. Tănăşelia, V. Almas, M. Vasilescu. (2005). Vibrational spectroscopy and theoretical studies on 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine J. Mol. Struct. 744:363. [CrossRef]

- Howsaui, H.B.; Sharfalddin, A.A.; Abdellattif, M.H.; Basaleh, A.S.; Hussien, M.A. (2021). Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization and Biological Studies of Mn(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), Co(II) and Zn(II) Complexes with New Schiff Base of 2-((Pyrazine-2-ylimino)methyl)phenol. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 906.

- M. Karabacak, E. Kose, A. Atac. (2012). Molecular structure (monomeric and dimeric structure) and HOMO–LUMO analysis of 2-aminonicotinic acid: a comparison of calculated spectroscopic properties with FT-IR and UV–Vis. Spectrochim. Acta A. 91:83. [CrossRef]

- M. Karabacak, E. Kose, A. Atac. (2012). Molecular structure (monomeric and dimeric structure) and HOMO–LUMO analysis of 2-aminonicotinic acid: a comparison of calculated spectroscopic properties with FT-IR and UV–Vis. Spectrochim. Acta A, 91:83.

- E. Porchelvi, S. Muthu Spectrochim. Acta A. (2015). Vibrational spectra, molecular structure, natural bond orbital, first order hyperpolarizability, thermodynamic analysis and normal coordinate analysis of Salicylaldehyde p-methylphenylthiosemicarbazone by density functional method. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 134:453-464.

- Mayada S. Ali, Mohamad Hasan. (2021). Chelating activity of (2E,2′E)-2,2′-(pyridine-2,6-diylbis(ethan-1-yl-1-ylidene)bis(N-ethylhydrazinecarbothioamide). Journal of Molecular Structure. 1238:130436.

- Damena T.; Zeleke D.; Desalegn T.; B Demissie T.; Eswaramoorthy R. (2022). Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Activities of Novel Vanadium(IV) and Cobalt(II) Complexes. ACS Omega. 7:4389-4404.

- Hasan M. M.; Ahsan H. M.; Saha P.; Naime J.; Kumar Das A.; Asraf M. A.; Nazmul Islam A. B. M.(2021). Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Electrochemical Activity of (E)-N-(4 (Dimethylamino) Benzylidene)-4H-1,2,4-Triazol-4-Amine Ligand and Its Transition Metal Complexes. Results Chem. 3:00115.

- Chebout O.; Trifa C.; Bouacida S.; Boudraa M.; Imane H.; Merzougui M.; Mazouz W.; Ouari K.; Boudaren C.; Merazig H. (2022). Two New Copper (II) Complexes with Sulfanilamide as Ligand: Synthesis, Structural, Thermal Analysis, Electrochemical Studies and Antibacterial Activity. J. Mol. Struct. 1248:131446. [CrossRef]

- Hoda F. El-Shafiy, M. Saif, Mahmoud M. Mashaly, Shimaa Abdel Halim, Mohamed F. Eid, A.I. Nabeel, R. Fouad. (2017). New; spectroscopy, thermal, structural analysis, DFT calculations and antimicrobial activity application. Journal of Molecular Structure. 1147:452-461.

- Mandewale M. C.; Kokate S.; Thorat B.; Sawant S.; Yamgar R. (2022). Zinc Complexes of Hydrazone Derivatives Bearing 3,4-Dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-One Nucleus as New Anti-Tubercular Agents. Arab. J. Chem. 12,4479–4489.

- Damena T, Alem MB, Zeleke D, Desalegn T, Eswaramoorthy R, Demissie TB. Novel Zinc(II) and Copper(II) Complexes of 2-((2-Hydroxyethyl)amino)quinoline-3-carbaldehyde for Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities: A Combined Experimental, DFT, and Docking Studies. ACS Omega. 7(30):26336-26352.

| Compounds | Color | M.Wt. | M.P. (oC) |

Λa | Calcd. (Found) (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | S | M | |||||

|

H2L (C6H12N6S2) |

Pale yellow | 232.32 | 225 | -- | 31.02 (31.04) |

5.21 (5.16) |

36.17 (35.07) |

27.60 (27.83) |

-- |

|

[Cu(L)].2H2O (C6H14CuN6O2S2) |

Dark brown | 329.89 (293.97)* |

263-270 | 4.34 | 21.84 (21.98) | 4.28 (3.80) | 25.48 (24.33) | 19.44 (18.95) | 20.31 (19.89) |

|

[Co(L)].2H2O (C6H14CoN6O2S2) |

Brown | 325.28 (288.97)* |

245-248 | 5.83 | 22.15 (22.22) | 4.34 (4.65) | 25.84 (24.70) | 19.72 (19.68) | 31.60 (31.28) |

| [Zn(H2L)2] (C12H26N12S4Zn) | Beige | 532.06 (481.28) |

268-272 | 21.52 | 27.09 (27.83) | 4.93 (4.95) | 31.59 (31.77) | 24.11 (25.38) | 19.26 (18.95) |

| Position | H2L | [Zn(H2L)2] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H (ppm) | 13C (ppm) | 1H (ppm) | 13C (ppm) | |

| 1 | -- | 148.37 | -- | 148.27 |

| 2 | -- | -- | ||

| 3 | 1.947 | 13.81 | 2.168 | 11.54 |

| 4 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 5 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 6 | 10.197,11.061 | -- | 10.208 | -- |

| 7 | -- | -- | ||

| 8 | -- | 183.12 | -- | 178.84 |

| 9 | -- | -- | ||

| 10 | 8.390,8.101 | -- | 7.850, 8.404 | -- |

| 12 | -- | -- | ||

| 13 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 14 | 1.947 | 11.55 | 2.508 | 11.54 |

| Compounds | ν(H2O) ν(NH/NH2) |

ν(C=N) ν(C=N)* |

ν(C=S) ν(C-S) |

ν(N-N) | ν(M-N) | ν(M-S) |

| H2L (C6H12N6S2) |

3408,3248, 3194, 3149 |

1594 -- |

833 -- |

948 | -- | -- |

| [Cu(L)].2H2O (C6H14CuN6O2S2) |

3407, 3250, 3187, 3144 |

1595, 1648 |

-- 649 |

1005 | 603 | 485 |

| [Co(L)].2H2O (C6H14CoN6O2S2) |

3401, 3289 3142 |

1564, 1693 |

-- 949 |

1004 | 599 | 484 |

| [Zn(H2L)2] (C12H26N12S4Zn) |

3408, 3248, 3189, 3151 |

1594 -- |

831 -- |

948 | 602 | 483 |

|

Compounds |

Temp. (°C) | Weight loss (%) Found (calcd.) |

assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

H2L (C6H12N6S2) |

30-191 191-221 230-650 |

-- 7.38(6.90) 91.67 (93.10) |

Stable Elimination of NH2 Complete decomposition of the ligand |

|

[Cu(L)].2H2O (C6H14CuN6O2S2) |

73.99 254-776 800 |

11.28 (10.91) 63.58 (62.53) 25.13 (26.54) |

- 2H2O - C4H10N6S2 Cu + 2C (Residue) |

|

[Co(L)].2H2O (C6H14CoN6O2S2) |

70 269-761 800 |

08.51 (11.07) 64.19 (63.41) 27.22 (25.50) |

- 2H2O - C4H10N6S2 Co + 2C (Residue) |

| [Zn(H2L)2] (C12H26N12S4Zn) | 30-157 265-750 800 |

-- 73.83 (75.56) 26.17 (24.34) |

Stable - C12H26N12S2 Zn +2S (Residue) |

|

| Metal complex |

Particle size ± standard deviation nm |

Graph |

|

|

Co- ligand complex |

266.7±83.31 |

|

|

|

Cu- ligand complex |

226.9±75.18 |

|

|

|

Zn- ligand complex |

254.9±68.87 |

|

| Parameter | Dilution used to treat the cells with the metal complexes/ µg | ||||

| |||||

|

Co- ligand complex 1:1 |

|

||||

| Drug conc µg | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 10 | 20 |

| mean - blank | 100 | 69.2 | 68.4 | 63.6 | 48.1 |

| Standard deviation | 8.00 | 7.15 | 7.08 | 8.29 | 3.07 |

|

Cu-ligand complex 1:1 |

|

||||

| Drug conc µg | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 10 | 20 |

| mean - blank | 100 | 9.80 | 6.06 | 3.91 | 3.31 |

| Standard deviation | 7.97 | 1.58 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.34 |

|

Zn-ligand complex 2:1 |

|

||||

| Drug conc µg | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 10 | 20 |

| mean - blank | 100 | 67.1 | 55.7 | 45.2 | 32.1 |

| Standard deviation | 2.45 | 0.92 | 6.14 | 3.17 | 4.80 |

| Strain/concentration | 5mg* | 10mg |

* * |

|

Bacillus subtills (gram-positive) |

Inhibition zone mm |

||

| Co-L complex | 9 | 9.3 | |

| Cu-L complex | 12.3 | 14 | |

| Zn-L Complex | Nill | Nill | |

| Free ligand | Nill | Nill | |

| Strain/concentration | 5mg | 10mg | |

|

E. coli (gram-negative) |

inhibition zone mm |

||

| Co-L complex | Nill | Nill | |

| Cu-L complex | 5.6 | 6 | |

| Zn-L Complex | Nill | Nill | |

| Free ligand | Nill | Nill | |

| |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).