Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Product Description

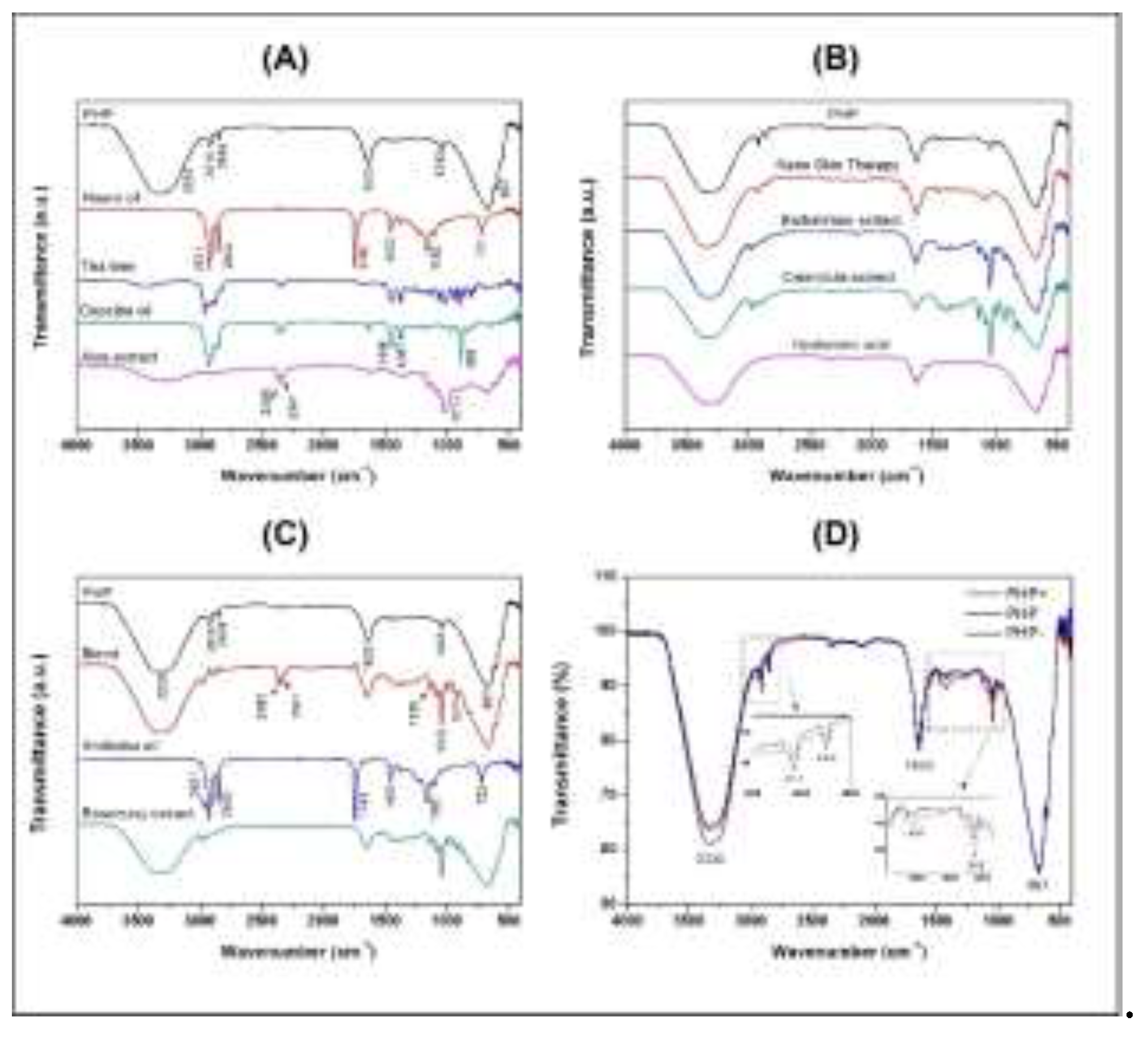

2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy Analysis of the Chemical Bonds

2.3. Cell Culture

2.4. Subculture and Standardization

2.5. Specimen Preparation

2.6. Cell Viability Assay

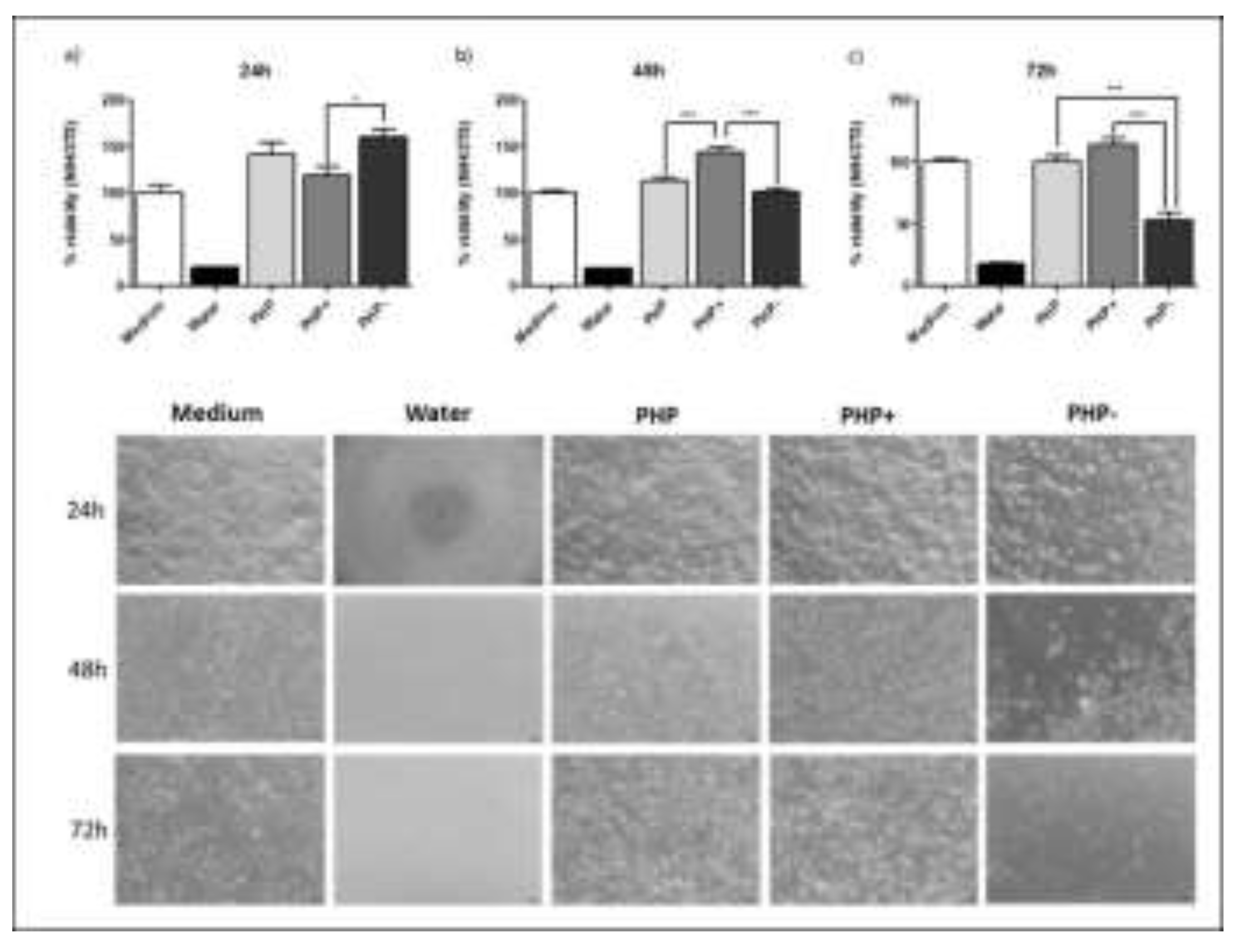

2.7. Evaluation of % Cell Viability in Cultures Exposed to Wound Healing Ointment (XTT Analysis)

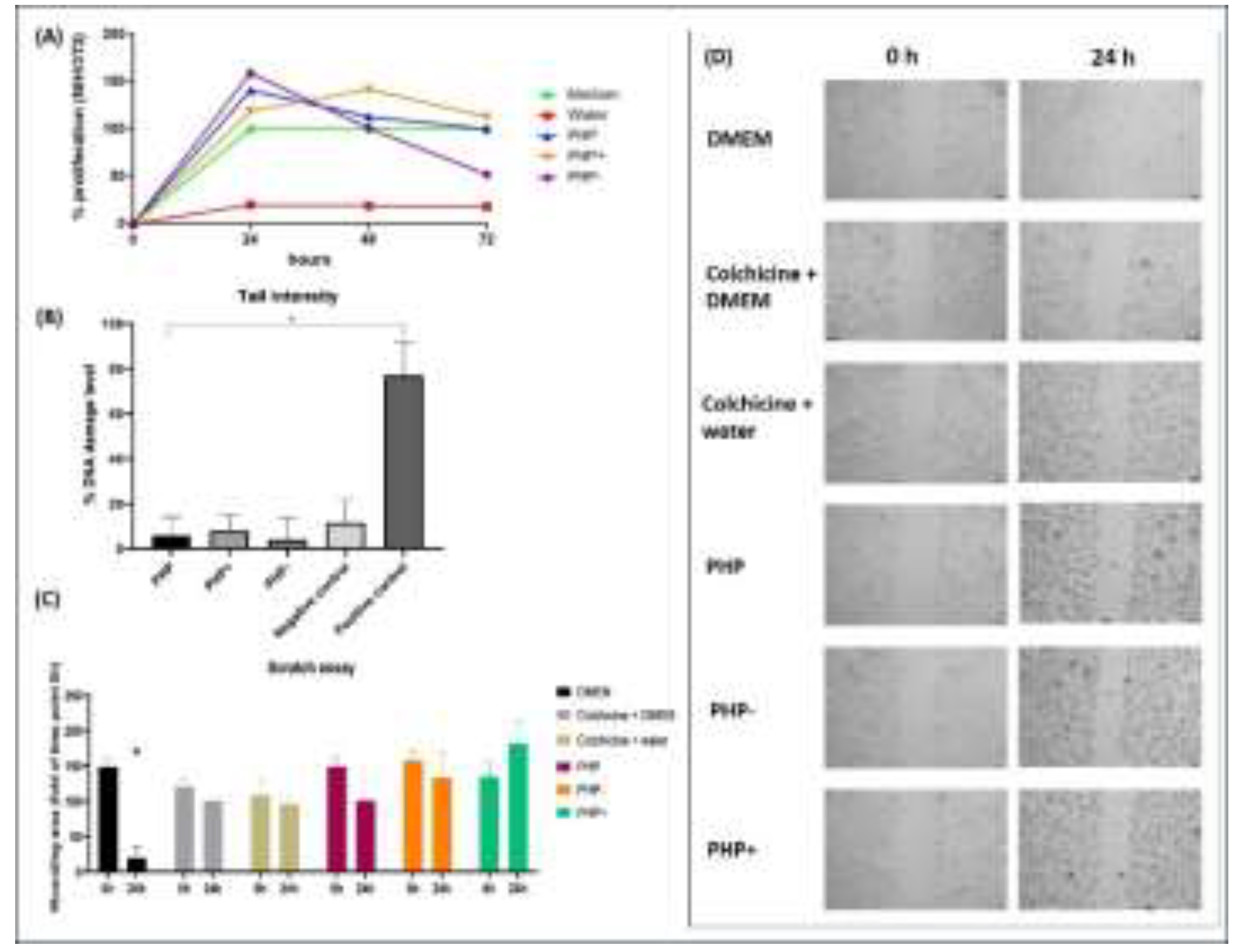

2.8. Genotoxicity Assay—Comet Assay

2.9. In Vitro Cell Migration/Proliferation Assay

2.10. In Vitro Acute Toxicity Test—Up and Down

2.11. Wound Healing Evaluation in Rat Model of Skin Wound

2.12. Histological Evaluation

2.13. Collagen Content Assessment

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy Analysis of the Chemical Bonds

3.2. Evaluation of % Cell Viability in Cultures Exposed to the Regenerative Ointment (XTT Analysis)

3.3. Genotoxicity Assay—Comet Test

3.4. Cell Migration Assay

3.5. In Vitro Acute Toxicity Test—Up and Down

3.6. Wound Healing Evaluation in Rat Model of Skin Wound

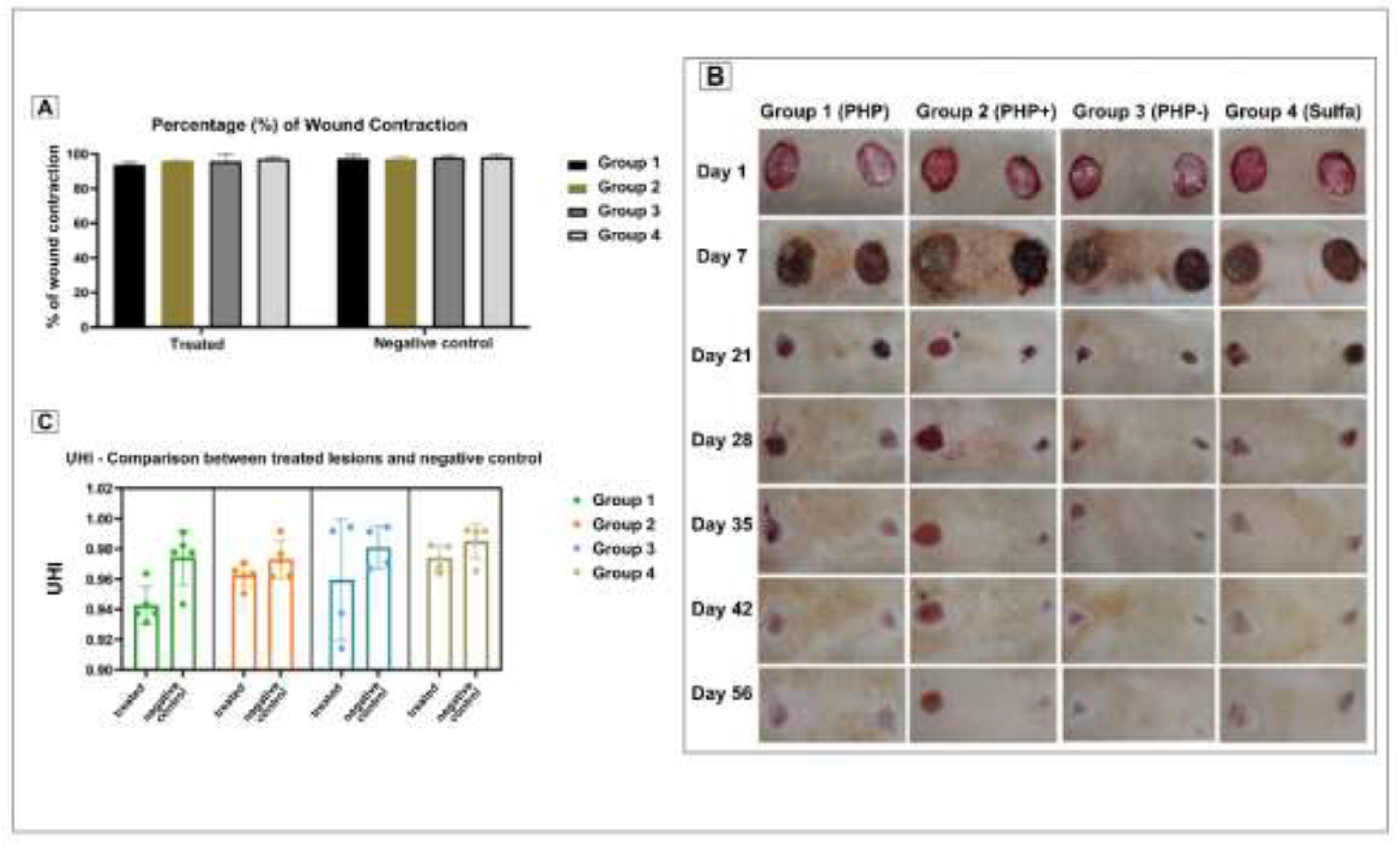

3.7. Wound Contraction and Percentage of Contraction

3.8. Ulcer Healing Index (UHI)

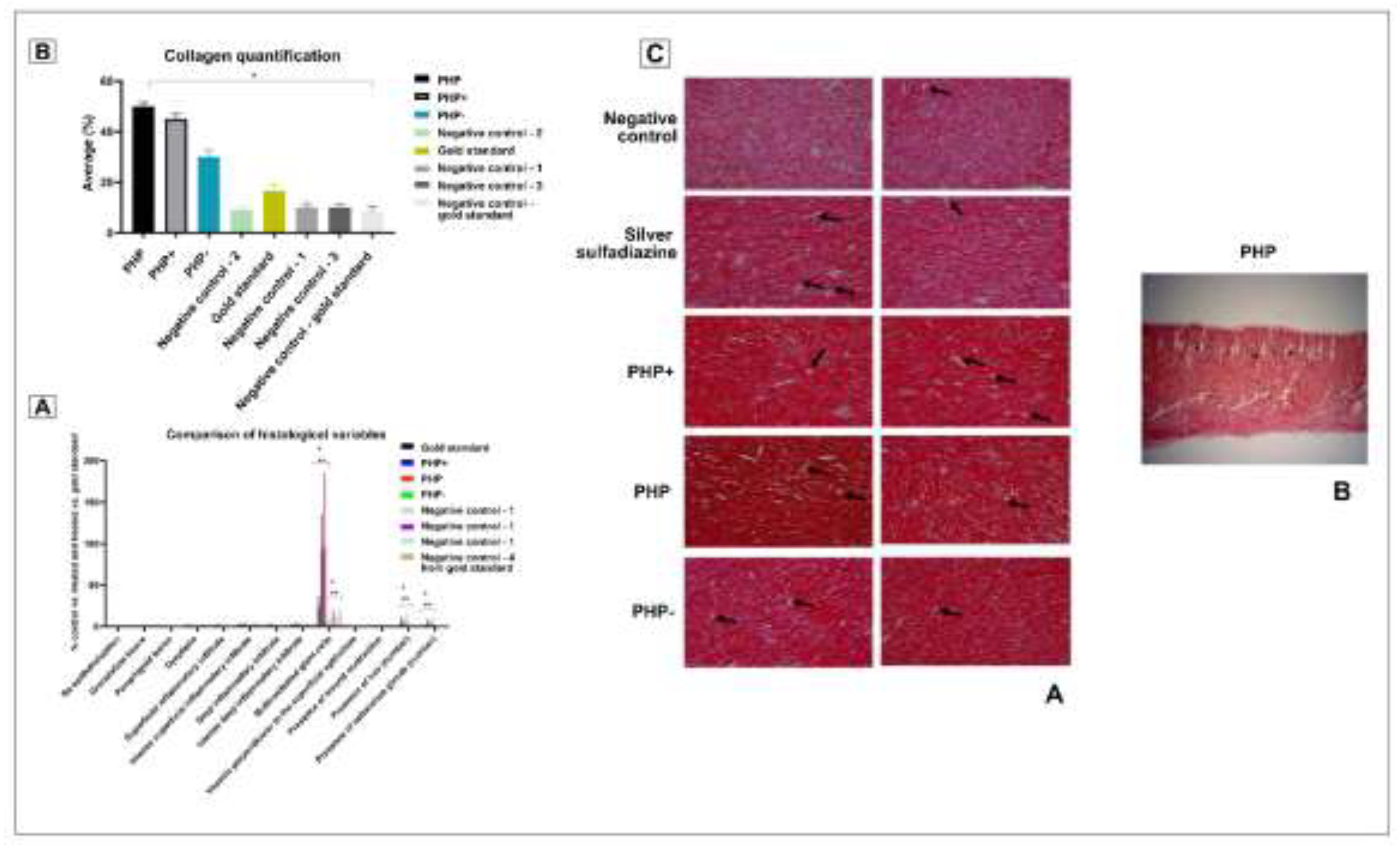

3.9. Histological Evaluation

3.10. Collagen Content Assessment

4. Conclusions

Data availability

Acknowledgments

References

- Alves, A.Q., da Silva, V.A.J., Góes, A.J.S., Silva, M.S., de Oliveira, G.G., Bastos, I.V.G.A., de Castro Neto, A.G., Alves, A.J., 2019. The fatty acid composition of vegetable oils and their potential use in wound care. Adv Skin Wound Care 32(8), 1-8.

- Andrade, J.M., Faustino, C., Garcia, C., Ladeiras, D., Reis, C.P., Rijo, P., 2018. Rosmarinus officinalis L.: an update review of its phytochemistry and biological activity. Future Sci OA 4(4), FSO283. [CrossRef]

- Anuar, N.S., Zahari, S.S., Taib, I.A., Rahman, M.T., 2008. Effect of green and ripe Carica papaya epicarp extracts on wound healing and during pregnancy. Food Chem Toxicol 46(7), 2384-2389. [CrossRef]

- Benito-Martínez, S., Pérez-Köhler, B., Rodríguez, M., Izco, J.M., Recalde, J.I., Pascual, G., 2022. Wound Healing Modulation through the Local Application of Powder Collagen-Derived Treatments in an Excisional Cutaneous Murine Model. Biomedicines 10(5), 960. [CrossRef]

- Berlanga-Acosta, J., Gavilondo-Cowley, J., López-Saura, P., González-López, T., Castro-Santana, M.D., López-Mola, E., Guillén-Nieto, G., Herrera-Martinez, L., 2009. Epidermal growth factor in clinical practice – a review of its biological actions, clinical indications and safety implications. Int Wound J 6(5), 331-346.

- Bianchi, S., Bernardi, S., Simeone, D., Torge, D., Macchiarelli, G., Marchetti, E., 2022. Proliferation and morphological assessment of human periodontal ligament fibroblast towards bovine pericardium membranes: an in vitro study. Materials 15(23), 8284. [CrossRef]

- Biglari, S., Le, T.Y.L., Tan, R.P., Wise, S.G., Zambon, A., Codolo, G., De Bernard, M., Warkiani, M., Schindeler, A., Naficy, S., Valtchev, P., Khademhosseini, A., Dehghani, F., 2019. Simulating inflammation in a wound microenvironment using a dermal wound-on-a-chip model. Advanced Healthcare Materials 8(1), 1801307.

- Bowers, S., Franco, E., 2020. Chronic wounds: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician 101(3), 159-166.

- Broughton, G.I., Janis, J.E., Attinger, C.E., 2006. The basic science of wound healing. Plast Reconst Surg 117(7S), 12S-34S. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Cheng, Y., Tian, J., Yang, P., Zhang, X., Chen, Y., Hu, Y., Wu, J., 2020. Dissolved oxygen from microalgae-gel patch promotes chronic wound healing in diabetes. Sci Adv 6(20), eaba4311.

- Childs, D.R., Murthy, A.S., 2017. Overview of wound healing and management. Surg Clin North Am 97(1), 189-207.

- Criollo-Mendoza, M.S., Contreras-Angulo, L.A., Leyva-López, N., Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P., Jiménez-Ortega, L.A., Heredia, J.B., 2023. Wound healing properties of natural products: mechanisms of action. Molecules 28(2), 598. [CrossRef]

- Dosoky, N.S., Setzer, W.N., 2018. Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oils of Curcuma species. Nutrients 10(9), 1196. [CrossRef]

- Du, P., Chen, X., Chen, Y., Li, J., Lu, Y., Li, X., Hu, K., Chen, J., Lv, G., 2023. In vivo and in vitro studies of a propolis-enriched silk fibroin-gelatin composite nanofiber wound dressing. Heliyon 9(3), e13506. [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, M., Newall, N., Carville, K., Smith, J., Riley, T.V., Carson, C.F., 2011. Uncontrolled, open-label, pilot study of tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil solution in the decolonisation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus positive wounds and its influence on wound healing. Int Wound J 8(4), 375-384. [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A., Martin, P., Tomic-Canic, M., 2014. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med 6(265), 265sr266-265sr266. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E., Liu, P.Y., Schultz, G.S., Martins-Green, M.M., Tanaka, R., Weir, D., Gould, L.J., Armstrong, D.G., Gibbons, G.W., Wolcott, R., Olutoye, O.O., Kirsner, R.S., Gurtner, G.C., 2022. Chronic wounds: treatment consensus. Wound Repair Regen 30(2), 156-171. [CrossRef]

- Frykberg, R.G., Banks, J., 2015. Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care 4(9), 560-582. [CrossRef]

- German, M.J., Hammiche, A., Ragavan, N., Tobin, M.J., Cooper, L.J., Matanhelia, S.S., Hindley, A.C., Nicholson, C.M., Fullwood, N.J., Pollock, H.M., Martin, F.L., 2006. Infrared spectroscopy with multivariate analysis potentially facilitates the segregation of different types of prostate cell. Biophys J 90(10), 3783-3795. [CrossRef]

- Gushiken, L.F.S., Hussni, C.A., Bastos, J.K., Rozza, A.L., Beserra, F.P., Vieira, A.J., Padovani, C.R., Lemos, M., Polizello Junior, M., Silva, J.J.M.d., Nóbrega, R.H., Martinez, E.R.M., Pellizzon, C.H., 2017. Skin wound healing potential and mechanisms of the hydroalcoholic extract of leaves and oleoresin of Copaifera langsdorffii Desf. Kuntze in rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2017, 6589270. [CrossRef]

- Hakim, R.F., Fakhrurrazi, Dinni, 2019. Effect of Carica papaya extract toward incised wound healing process in mice musculus clinically and histologically. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2019, 8306519. [CrossRef]

- Harsha, L., Brundha, M.P., 2020. Role of collagen in wound healing. Drug Invention Today 13(1), 55-57.

- Holman, H.-Y.N., Martin, M.C., Blakely, E.A., Bjornstad, K., Mckinney, W.R., 2000. IR spectroscopic characteristics of cell cycle and cell death probed by synchrotron radiation based Fourier transform IR spectromicroscopy. Biopolymers 57(6), 329-335.

- Ibrahim, N.I., Wong, S.K., Mohamed, I.N., Mohamed, N., Chin, K.-Y., Ima-Nirwana, S., Shuid, A.N., 2018. Wound healing properties of selected natural products. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(11), 2360. [CrossRef]

- ISO10993-3, 2014. Biological evaluation ofmedical devices, Part 3: Tests for genotoxicity, carcinogenicityand reproductive toxicity. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- ISO10993-5, 2009. Biological evaluation of medical devices, Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland, p. 34.

- Jeon, J.G., Rosalen, P.L., Falsetta, M.L., Koo, H., 2011. Natural products in caries research: current (limited) knowledge, challenges and future perspective. Caries Res 45(3), 243-263. [CrossRef]

- Junker, J.P.E., Caterson, E.J., Eriksson, E., 2013. The microenvironment of wound healing. Arch Craniofac Surg 24(1), 12-16. [CrossRef]

- Koczoń, P., Hołaj-Krzak, J.T., Palani, B.K., Bolewski, T., Dąbrowski, J., Bartyzel, B.J., Gruczyńska-Sękowska, E., 2023. The analytical possibilities of FT-IR spectroscopy powered by vibrating molecules. Int J Mol Sci 24(2), 1013. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, H., Nakada, T., Yagami, A., Todo, H., Nishimura, J., Yagi, M., Yamamoto, K., Sugiyama, M., Ikarashi, Y., Sakaguchi, H., Yamaguchi, M., Hirota, M., Aizawa, S., Nakagawa, S., Hagino, S., Hatao, M., 2023. A step-by-step approach for assessing acute oral toxicity without animal testing for additives of quasi-drugs and cosmetic ingredients. Curr Res Toxicol 4, 100100. [CrossRef]

- Las Heras, K., Igartua, M., Santos-Vizcaino, E., Hernandez, R.M., 2020. Chronic wounds: current status, available strategies and emerging therapeutic solutions. J Control Release 328, 532-550. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J., Chung, J., Na, H.-S., Park, E.-J., Jeon, H.-J., Kim, H.-C., 2013. Characteristics of novel root-end filling material using epoxy resin and Portland cement. Clin Oral Investig 17(3), 1009-1015. [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.N., Leite, S.N., Caetano, G.F., Andrade, T.A.M., Fronza, M., Frade, M.A.C., 2020. Healing effects of natural latex serum 1% from Hevea brasiliensis in an experimental skin abrasion wound model. An Bras Dermatol 95(4), 418-427. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.-C., Park, A.Y., Guan, J.-L., 2007. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc 2(2), 329-333. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J., Cui, L., Li, J., Guan, S., Zhang, K., Li, J., 2021. Aloe vera: a medicinal plant used in skin wound healing. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 27(5), 455-474. [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.C.S., Martins, D.T.O., de Souza Jr., P.T., 1998. Experimental evaluation of stem bark of Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) Coville for antiinflammatory activity. Phytotherapy Research 12(3), 218-220.

- Liu, E., Gao, H., Zhao, Y., Pang, Y., Yao, Y., Yang, Z., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Yang, S., Ma, X., Zeng, J., Guo, J., 2022. The potential application of natural products in cutaneous wound healing: A review of preclinical evidence. Front Pharmacol 13. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, H.P., Longaker, M.T., 2003. Wounds: Biology, Pathology, and Management, in: Li, M., Norton, J.A., Bollinger, R.R., Chang, A.E., Lowry, S.F., Mulvihill, S.J., Pass, H.I., Thompson, R.W. (Eds.), Essential Practice of Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. Springer New York, New York, NY, pp. 77-88.

- Masson-Meyers, D.S., Andrade, T.A.M., Caetano, G.F., Guimaraes, F.R., Leite, M.N., Leite, S.N., Frade, M.A.C., 2020. Experimental models and methods for cutaneous wound healing assessment. International Journal of Experimental Pathology 101(1-2), 21-37. [CrossRef]

- Mathew-Steiner, S.S., Roy, S., Sen, C.K., 2021. Collagen in wound healing. Bioengineering 8(5), 63.

- Netto, A.O., Gelati, R.B., Serrano, R.G., Volpato, G.T., Vieira, M., Rudge, C., Damasceno, C., 2017. Approaches of whole blood thawing for genotoxicity analysis in rats. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol 1(007).

- Olive, P.L., Banáth, J.P., Durand, R.E., 1990. Heterogeneity in radiation-induced DNA damage and repair in tumor and normal cells measured using the „comet” assay. Radiat Res 122(1), 86-94. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.A.d., Matos, A.A., Matsuda, S.S., Buzalaf, M.A.R., Bagnato, V.S., Machado, M.A.d.A.M., Damante, C.A., Oliveira, R.C.d., Peres-Buzalaf, C., 2017. Low level laser therapy modulates viability, alkaline phosphatase and matrix metalloproteinase-2 activities of osteoblasts. J Photochem Photobiol B, Biol 169, 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Padmawar, A.R., Bhadoriya, U., 2018. Glycol and glycerin: pivotal role in herbal industry as solvent/co-solvent. World J Pharm Res 4(5), 153-155.

- Pazyar, N., Yaghoobi, R., Rafiee, E., Mehrabian, A., Feily, A., 2014. Skin Wound Healing and Phytomedicine: A Review. Skin Pharmacol 27(6), 303-310. [CrossRef]

- Piacenti-Silva, M., Matos, A.A., Paulin, J.V., Alavarce, R.A.d.S., de Oliveira, R.C., Graeff, C.F., 2016. Biocompatibility investigations of synthetic melanin and melanin analogue for application in bioelectronics. Polym Int 65(11), 1347-1354. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E.P., Menezes, R.P., de S. Tavares, W., Ferreira, A.M., Sousa, F.F.O.d., Araújo da Silva, G., Zamora, R.R.M., Araújo, R.S., de Souza, T.M., 2023. Copaiba essential oil loaded-nanocapsules film as a potential candidate for treating skin disorders: preparation, characterization, and antibacterial properties. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 633, 122608.

- Santos, J.T., Marcucci, M.C., Santos, M.L.d., D’Alpino, P.H.P., 2023. Exploratory cross-sectional study of the use of a green propolis-based ointment in the treatment of skin tears in elderly hospitalized patients. Res, Soc Dev 12(4), e12412441061.

- Sen, C.K., 2021. Human wound and its burden: updated 2020 compendium of estimates. Adv Wound Care 10(5), 281-292.

- Song, Y.H., Zhu, Y.T., Ding, J., Zhou, F.Y., Xue, J.X., Jung, J.H., Li, Z.J., Gao, W.Y., 2016. Distribution of fibroblast growth factors and their roles in skin fibroblast cell migration. Mol Med Rep 14(4), 3336-3342. [CrossRef]

- Strecker-McGraw, M.K., Jones, T.R., Baer, D.G., 2007. Soft Tissue Wounds and Principles of Healing. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 25(1), 1-22.

- Thomas, D.C., Tsu, C.L., Nain, R.A., Arsat, N., Fun, S.S., Sahid Nik Lah, N.A., 2021. The role of debridement in wound bed preparation in chronic wound: A narrative review. Ann Med Surg 71, 102876.

- Tice, R.R., Agurell, E., Anderson, D., Burlinson, B., Hartmann, A., Kobayashi, H., Miyamae, Y., Rojas, E., Ryu, J.-C., Sasaki, Y.F., 2000. Single cell gel/comet assay: Guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing. Environ Mol Mutagen 35(3), 206-221.

- Volkov, V.A., Voronkov, M.V., Misin, V.M., Fedorova, E.S., Rodin, I.A., Stavrianidi, A.N., 2021. Aqueous propylene glycol extracts from medicinal plants: chemical composition, antioxidant activity, standardization, and extraction kinetics. Inorg Mater 57(14), 1404-1412. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.H., Huang, B.S., Horng, H.C., Yeh, C.C., Chen, Y.J., 2018. Wound healing. J Chin Med Assoc 81(2), 94-101.

- Wilgus, T.A., 2008. Immune cells in the healing skin wound: Influential players at each stage of repair. Pharmacol Res 58(2), 112-116.

- Yang, H., Song, L., Zou, Y., Sun, D., Wang, L., Yu, Z., Guo, J., 2021. Role of hyaluronic acids and potential as regenerative biomaterials in wound healing. ACS Appl Bio Mater 4(1), 311-324. [CrossRef]

- Yogiraj, V., Goyal, P., Chauhan, C.S., Goyal, A., Vyas, B., 2014. Carica papaya Linn: an overview. Int J Herb Med 2, 1-8.

- Yuan, H., Ma, Q., Ye, L., Piao, G., 2016. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules 21(5), 559. [CrossRef]

| VEGETABLE OILS |

|---|

| ANDIROBA OIL (CARAPA GUIANENSIS) |

| NEEM OIL (AZADIRACHTA INDICA) |

| COPAIBA OIL (COPAIFERA LANGSDORFFII) |

| PLANT EXTRACTS |

| ALOE DRIED EXTRACT (ALOE VERA) |

| ROSEMARY GLYCOLIC EXTRACT (ROSMARINUS OFFICINALIS) |

| CALENDULA GLYCOLIC EXTRACT (CALENDULA OFFICINALIS) |

| BARBATIMAO GLYCOLIC EXTRACT (STRYPHNODENDRON SP.) |

| BLEND (GLYCOLIC EXTRACTS OF CARICA PAPAYA AND ALOE VERA)** |

| ESSENTIAL OIL |

| TEA TREE (MELALEUCA ALTERNIFOLIA) |

| OTHER BIOACTIVES |

| NANO SKIN THERAPY*** |

| HYALURONIC ACID |

| BLEND (GLYCOLIC EXTRACTS OF CARICA PAPAYA AND ALOE VERA)*** |

| Wavenumber (cm–1) | Band assignment |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioactive compounds | PHP compositions | |||||||||||||

| Neem oil | Tea tree | Copaiba oil | Aloe extract | Nano Skin Therapy |

Barbatimaoextract | Calendulaextract | Hyaluronic acid | Blend | Andiroba oil |

Rosemary extract | PHP- | PHP | PHP+ | |

| - | 3435 | - | 3280 | 3350 | 3324 | 3324 | 3324 | 3312 | - | 3324 | 3335 | 3335 | 3335 | ν(O-H) |

| - | 2960 | - | - | - | 2978 | 2974 | - | 2979 | - | 2979 | - | - | - | ν(C-H) |

| 2921 | 2914 | 2924 | 2916 | 2924 | - | 2934 | - | - | 2921 | - | 2916 | 2916 | 2914 | νasy(CH2) ν(CH3) |

| 2852 | 2875 | 2856 | - | 2853 | - | 2880 | - | 2882 | 2852 | - | 2850 | 2850 | 2848 | νsym(CH2) ν(CH3) |

| - | 2360 | 2359 | 2359 | - | - | - | 2359 | 2360 | - | 2362 | - | - | - | ν(O=C=O) |

| - | 2341 | 2341 | 2341 | - | - | - | - | 2341 | - | - | - | - | - | ν(O=C=O) |

| 1743 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1743 | - | - | - | - | ν(C=O) |

| - | - | 1633 | 1633 | 1643 | 1644 | 1647 | 1633 | 1642 | - | 1644 | 1633 | 1640 | 1640 | ν(C=C) |

| 1463 | 1446 | 1446 | - | 1462 | - | - | - | - | 1463 | - | - | - | 1414 | δ(C-H) |

| 1377 | 1377 | 1367 | 1338 | - | - | - | - | - | 1377 | - | - | - | - | δ(C-H) |

| 1160 | - | 1181 | 1148 | - | - | - | - | - | 1160 | - | - | - | - | ν(C-O) |

| - | - | - | - | - | 1136 | 1136 | - | 1135 | 1116 | 1136 | - | - | - | ν(C-O) |

| - | - | - | - | 1085 | 1081 | 1079 | - | 1079 | - | 1080 | - | - | - | ν(C-O) |

| - | 1026 | - | 1015 | - | 1042 | 1040 | - | 1042 | - | 1041 | 1043 | 1043 | 1043 | ν(C-O) |

| - | - | 967 | - | - | 990 | 990 | - | 990 | - | - | - | - | - | δ(C=C) |

| - | - | - | - | - | 921 | 921 | - | 922 | - | 921 | - | - | - | δ(C=C) |

| - | 887 | 885 | 895 | - | - | 837 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | δ(C=C) |

| 721 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 722 | - | - | - | - | δ(C=C) |

| - | - | - | 667 | 667 | 669 | 667 | 667 | 667 | - | 669 | 667 | 666 | 667 | δ(C=C) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).