1. Introduction

The skin, as the body's largest organ, plays a crucial role in protecting against environmental stressors, regulating temperature, and preventing water loss [

1]. The skin barrier is composed of lipids and proteins that make up the stratum corneum, which functions to maintain skin hydration and protect against external stimuli [

2]. Maintaining a healthy skin barrier is essential for overall skin health and function [

3]. Facial flushing, characterized by sudden reddening of the face, neck, and upper chest, is a common dermatological phenomenon caused by increased blood flow to the skin's surface [

4]. This condition can be triggered by various factors, including emotional stress, hormonal changes, alcohol consumption, spicy foods, certain medications, and genetic factors [

5,

6,

7,

8]. While often benign, facial flushing can also be a symptom of underlying medical conditions such as rosacea, carcinoid syndrome, or thyroid disorders [

9]. Diagnosis typically involves a thorough medical history, physical examination, and consideration of associated symptoms, with additional tests performed if necessary [

10,

11]. Management strategies vary depending on the cause, ranging from simple lifestyle modifications and topical treatments to medications addressing specific underlying conditions [

12]. Although usually harmless, persistent or severe flushing should be evaluated by a healthcare professional to rule out more serious issues. Understanding the diverse causes and appropriate management of facial flushing is crucial for both patients and healthcare providers in addressing this common yet potentially distressing condition [

13].

Herbal medicine encompasses the use of plant-based remedies for disease prevention and treatment, spanning from traditional practices in various cultures to modern, standardized herbal extracts [

14]. Herbal medicines are often region-specific, as they rely on plants native to or commonly grown in particular geographical areas. While India and China are widely recognized as the two main powerhouses of traditional herbal medicine, with their well-established systems of Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine respectively, many countries around the world have developed their own unique traditional medicinal practices based on local flora [

15].

Traditional Korean herbal medicine, known as Hanbang in Korean, has been an integral part of Korean culture for centuries, utilizing herbs to treat various ailments and promote overall health both domestically and internationally [

16]. In recent years, there has been growing interest in exploring the potential of these traditional remedies for modern applications, particularly in the field of dermatology [

17]. Research on Korean cosmeceuticals emphasizes the innovative use of natural ingredients with antiaging, antitumor, and antimelanogenic effects, while also analyzing the composition and metal content of Korean herbs and herbal products to ensure their safety and efficacy in modern dermatological applications [

18,

19]. Moreover, instead of using a single extract, a mixture of Korean herbal extracts could be effectively applied for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases [

20].

The skin health of individuals experiencing hormonal changes has become a significant concern in recent years, with issues such as facial flushing and skin barrier damage leading to both physical and psychological distress [

21]. Despite the growing need, there has been a lack of comprehensive research addressing these specific skin problems in this demographic. Concurrently, consumer demand for natural ingredient-based cosmetics has surged, driven by the expanding clean beauty and vegan beauty trends.

As a result, it is important to develop and evaluate the efficacy of a natural-derived cosmetic product specifically designed for skin issues related to facial flushing and skin barrier damage. For that, we developed herbal medicine composite 5 (HRMC5), a complex extract comprising five traditional Korean herbal extracts. These extracts include

Cimicifuga racemosa root extract,

Paeonia lactiflora root extract,

Phellodendron amurense root extract,

Rheum rhaponticum root extract, and

Scutellaria baicalensis bark extract. These ingredients were selected based on their specific properties that contribute to skin health as follows.

Cimicifuga racemosa offers anti-inflammatory and vasoconstriction effects, potentially alleviating skin redness [

22].

Paeonia lactiflora provides vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory actions [

23].

Phellodendron amurense offers anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects, potentially helping to calm the skin and reduce irritation [

24].

Rheum rhaponticum is known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [

25].

Scutellaria baicalensis possesses strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, which may help calm the skin and reduce sensitivity [

26].

We employed a range of analytical and experimental methods to evaluate the efficacy of HRMC5. These methods include high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), cell viability assays, ultraviolet (UV) protection evaluations, wound healing assays, and gene expression analyses. Collectively, our findings demonstrate the effectiveness of HRMC5 in improving skin redness and strengthening the skin barrier in individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Five Herbal Plant Extracts

Five herbal materials were used: Cimicifuga racemosa root extract, Paeonia lactiflora root extract, Phellodendron amurense root extract, Rheum rhaponticum root extract, and Scutellaria baicalensis bark extract. Each of the five plant materials was mixed in equal proportions, and 50 grams of this mixture was extracted with 1 liter of 70% ethanol at 60°C for 24 hours. The extracted solution was filtered, concentrated using a rotary vacuum evaporator, and finally freeze-dried into a powder form. This composite sample was prepared to represent the combined effects of all five extracts. To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the extracts, the solution was diluted to various concentrations. The initial concentration of 5 grams per liter was deemed high and potentially toxic, so it was diluted to 2.5 grams per liter, 1.25 grams per liter, 0.625 grams per liter, 0.313 grams per liter, 0.156 grams per liter, and 0.078 grams per liter. For cell culture experiments, the extracts were further diluted to ensure that the ethanol concentration did not exceed 1%, to avoid potential toxicity to the cells.

2.2. Sample Preperation for HPLC

The mixed herbal plant extract was re-dissolved in 70% ethanol at a concentration of 5 g/L. This concentration was necessary to adjust the optimal detection range for HPLC analysis. The re-dissolved sample was filtered through a 0.45 μm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) syringe filter to eliminate any remaining particulates that might interfere with the HPLC analysis.

2.3. HPLC Analysis

The HPLC analysis was performed using an Arc HPLC system, which was equipped with a 2998 Photodiode Array (PDA) detector from Waters, U.S.A. Separation of the components was achieved with a Shim-Pack GIS C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, Shimadzu, Japan). The mobile phases used were: Mobile Phase A, which consisted of water containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and Mobile Phase B, which consisted of acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA.

For the operational parameters, a 20 μL volume of each prepared sample was injected. The column was maintained at a temperature of 30°C. The detector settings were configured to scan from 200 to 800 nm.

The gradient program was as follows: at 0 minutes, the mobile phase composition was 90% A and 10% B. Until 20 minutes, this composition was maintained at 90% A and 10% B. By 40 minutes, the composition changed to 80% A and 20% B. By 60 minutes, it shifted to 60% A and 40% B. By 80 minutes, the composition shifted to 30% A and 70% B. By 82 minutes, the composition changed to 10% A and 90% B, which was maintained until 95 minutes. From 95 to 97 minutes, the composition returned to 90% A and 10% B. Finally, until 110 minutes, the composition remained at 90% A and 10% B.

2.4. Data Acquisition and Analysis

Peak identification was performed by comparing chromatographic peak retention times and spectral data with those of individual plant extracts. Each peak was then identified and confirmed using BIO-FD&C Co., Ltd's proprietary natural product database.

2.5. Assessment of Cellular Viability

The impact of herbal extracts on cell proliferation and survival was evaluated using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. Human keratinocytes (HaCaT) were plated in 96-well formats at 5 x 104 cells per well and cultured for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to varying concentrations of herbal extracts (5 grams per liter, 2.5 grams per liter, 1.25 grams per liter, 0.625 grams per liter, 0.313 grams per liter, 0.156 grams per liter, and 0.078 grams per liter) for an additional 24 hours, with sterile water serving as a control. Following treatment, 1X CCK-8 solution (Catalog Number CCK-3000, Donginbio, Seoul, Korea) was introduced to each well, and the cells were incubated for 3 more hours. Absorbance readings at 450 nm were obtained using a Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO Microplate Spectrophotometer (Fisher Scientific Ltd., Vantaa, Finland). Cell viability was quantified as a percentage, calculated by dividing the absorbance of treated cells by that of control cells and multiplying by 100.

2.6. Evaluation of Ultraviolet Protection

Human adult keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5 x 104 cells per well and grown for 24 hours. The culture medium was then replaced with serum-free medium for 4 hours. Cells were subjected to UVB radiation (5-15 mJ/cm2) using a UVP CL-1000 Ultraviolet Crosslinker. Post-irradiation, cells were treated with herbal extracts and incubated for 24 hours. A CCK-8 assay was subsequently performed to assess alterations in cell viability.

2.7. Analysis of Wound Healing Capacity

The wound healing process was evaluated using specialized culture inserts placed in 24-well plates. HaCaT cells were introduced into the inserts at a density of 3 x 105 cells per well and cultured until they reached approximately 90% confluence, which took 24 hours. Once the inserts were removed, the initial cell arrangement was photographed to establish a baseline. The cells were subsequently exposed to 100 ng/mL of epidermal growth factor (EGF), applied to both the experimental samples and positive control groups. After an 18-hour incubation period, the cells underwent fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. They were then rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before being imaged a second time. The progression of wound healing was quantified by measuring cell migration between the initial (0-hour) and final (18-hour) images using ImageJ software.

2.8. Transcriptional Analysis via Quantitative RT-PCR

Cells exposed to herbal extracts were harvested using trypsin, rinsed with PBS, and cryopreserved at -80°C pending RNA isolation. A minimum of 1 x 106 cells per experimental group underwent RNA extraction using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). mRNA concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. cDNA synthesis was performed using RT Master Mix 10 (Qiagen). Quantitative PCR was executed using THUNDERBIRD Next SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), specific primers, and the synthesized cDNA. The thermal cycling protocol consisted of 40 cycles: denaturation (95°C, 15 seconds), annealing (62°C, 60 seconds), and extension (72°C, 60 seconds). Gene expression was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and relative expression levels were computed using R = 2-[ΔΔCt] method.

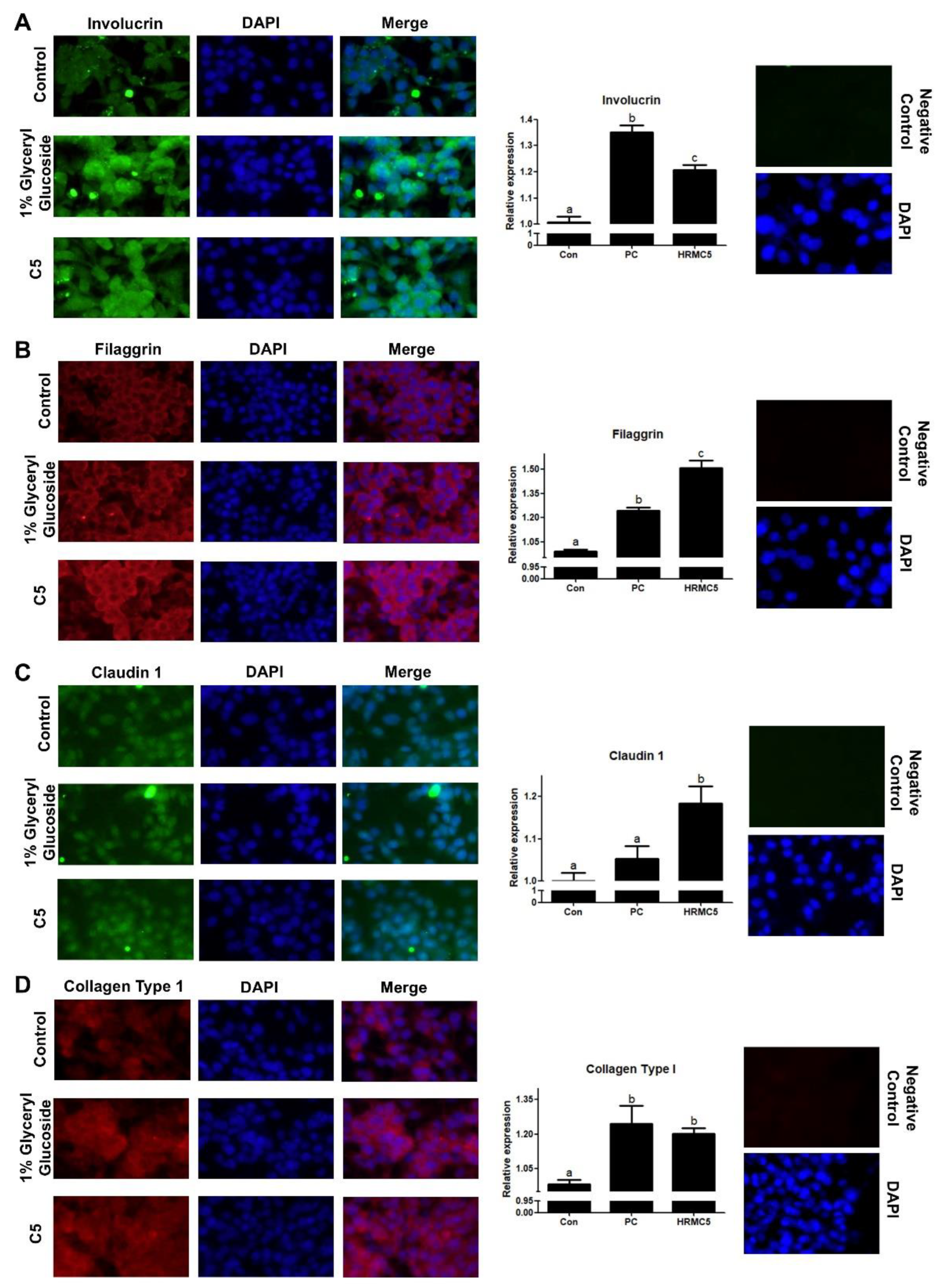

2.9. Protein Localization Analysis

Following herbal extract treatment, cells underwent PBS washing and fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 60 minutes. Subsequently, cells were permeabilized using 1% Triton X-100 and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin to prevent non-specific antibody binding. Primary antibodies targeting Involucrin (1:200), Claudin1 (1:200), Filaggrin (1:100), and Collagen Type I (1:200) were applied and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing, cells were treated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary antibody and counterstained with Hoechst-33342. Fluorescence imaging was performed using a fluorescence microscope, and the resulting images were analyzed using ImageJ software.

2.10. Data Analysis and Interpretation

The statistical evaluation of the data was performed using SigmaStat software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Each experiment was replicated a minimum of three times, incorporating both biological and technical replicates to ensure robustness. The results are presented as means accompanied by their standard errors. Prior to analysis, the data sets were examined for normality and homogeneity of variance. For comparisons involving three or more experimental groups, two different approaches were employed based on the data distribution: the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to non-parametric data, while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for parametric data. Following these tests, post hoc analyses were conducted using either Duncan's multiple range test or Dunnett's T3 test, as appropriate. In cases where only two groups were being compared, either the Mann-Whitney U test (for non-parametric data) or Student's t-test (for parametric data) was utilized. Throughout the analysis, a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To visually represent the findings, GraphPad PRISM 5.01 software was employed to generate clear and informative graphs and charts.

4. Discussion

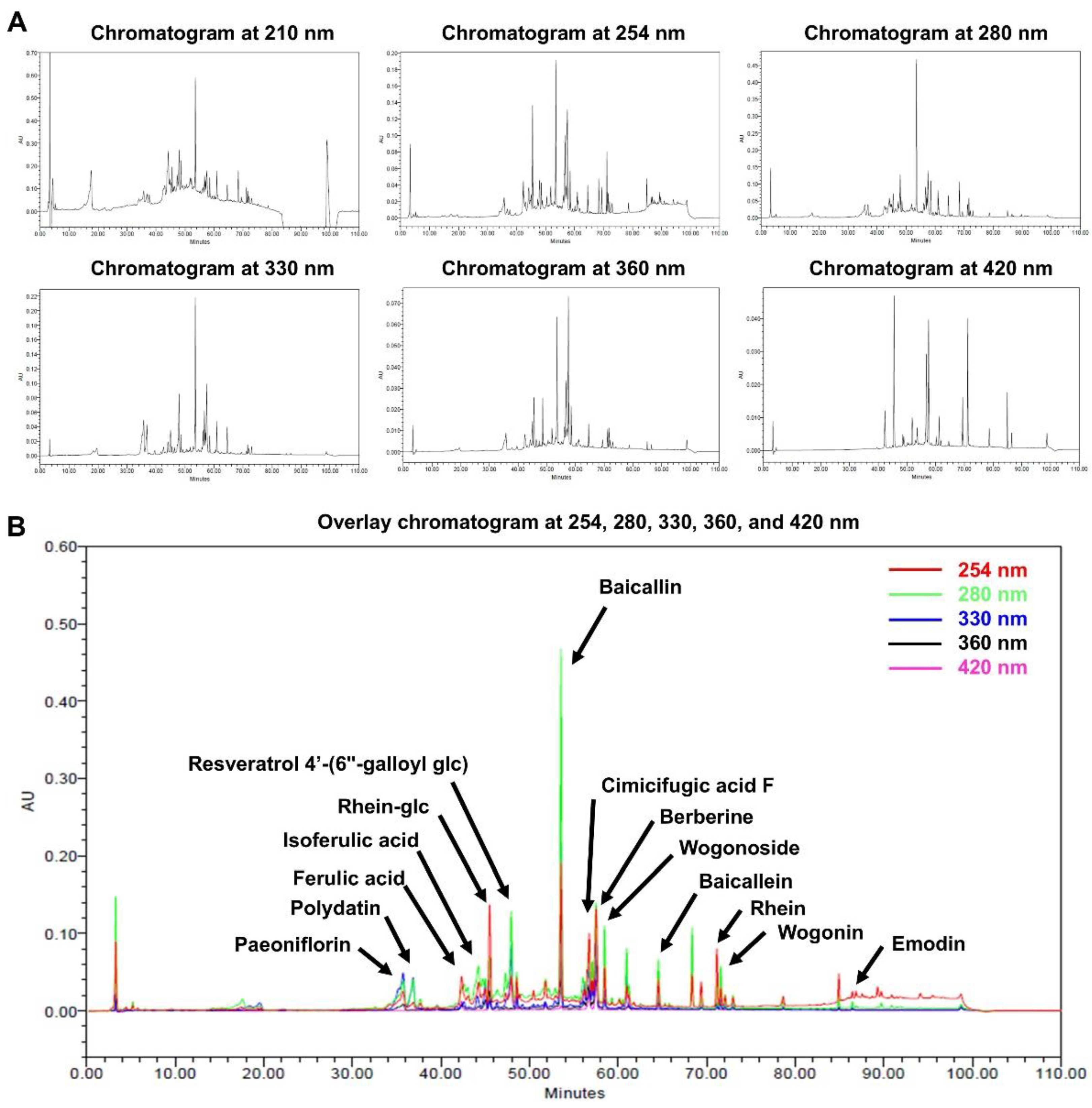

The HPLC analysis successfully identified 14 bioactive compounds in HRMC5. These compounds, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, anthraquinones, and alkaloids, each contribute to the therapeutic potential of the mixture. Flavonoids such as baicalin, baicalein, and wogonoside from

Scutellaria baicalensis are known for their strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [

27]. Phenolic acids like ferulic and isoferulic acid further enhance the antioxidant capacity of the mixture [

28]. The presence of anthraquinones such as rhein and emodin from

Rheum officinale contributes antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects [

29], while berberine from

Phellodendron amurense offers antibacterial benefits [

30,

31]. The study emphasizes the potential synergistic effects of these bioactive compounds, suggesting enhanced therapeutic efficacy when used in combination.

The HPLC analysis was conducted at multiple wavelengths, with 254 nm identified as the most suitable for comprehensive detection of phytochemicals. Our study highlights the potential synergistic effects of the identified compounds, suggesting enhanced therapeutic efficacy when combined. The findings align with previous research on individual herbs, reinforcing the bioactive profiles of these traditional remedies [

32,

33]. Future studies employing advanced analytical techniques could further elucidate the full phytochemical profile and pharmacological activities of this herbal mixture [

34].

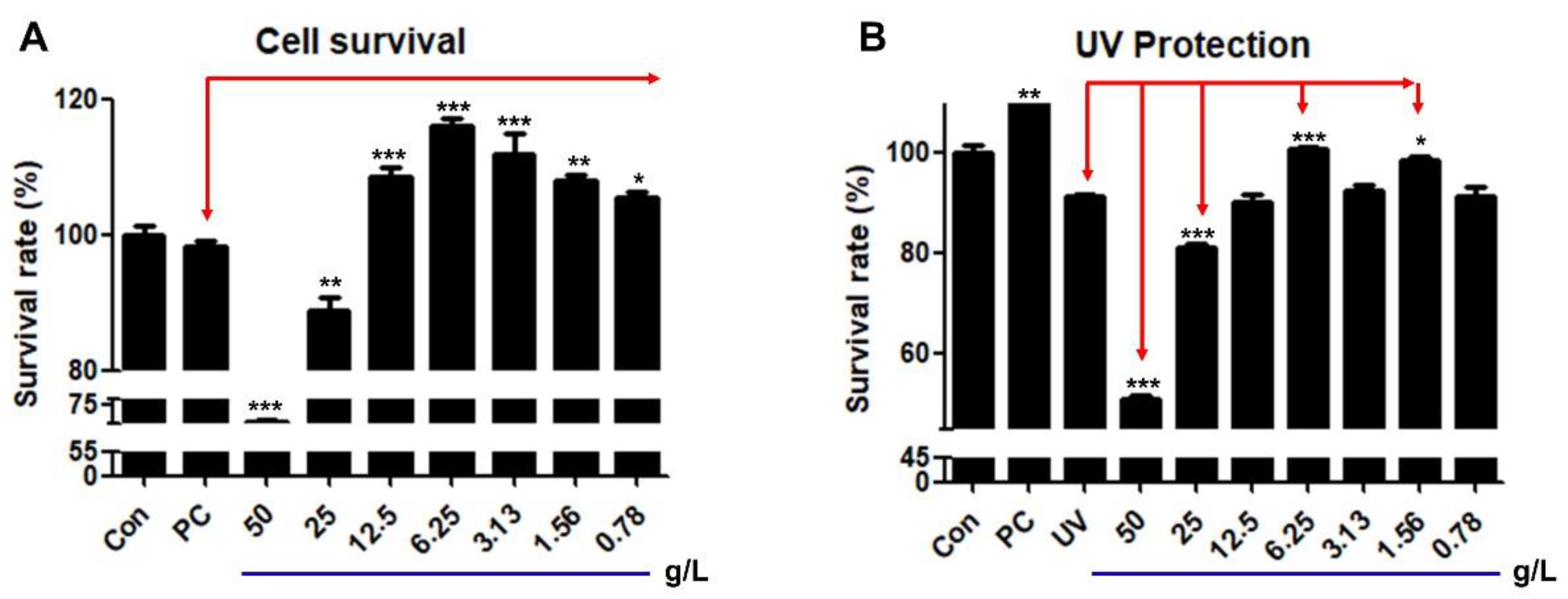

The mixture demonstrated concentration-dependent effects on cell viability and UV protection, with a biphasic response observed. Lower concentrations (0.078-1.25 g/L) improved cell survival, while higher concentrations (2.5-5 g/L) exhibited cytotoxic effects. Such biphasic effects of plant extracts have been demonstrated in other previous studies [

35,

36]. The optimal concentration for both cell survival and UV protection was found to be 0.625 g/L. This finding highlights the mixture’s narrow therapeutic window, where beneficial effects are only observed at specific concentrations as shown previously [

37]. The extract's ability to protect cells from UV-induced damage further indicates its potential as a cytoprotective agent, particularly at the optimal concentration.

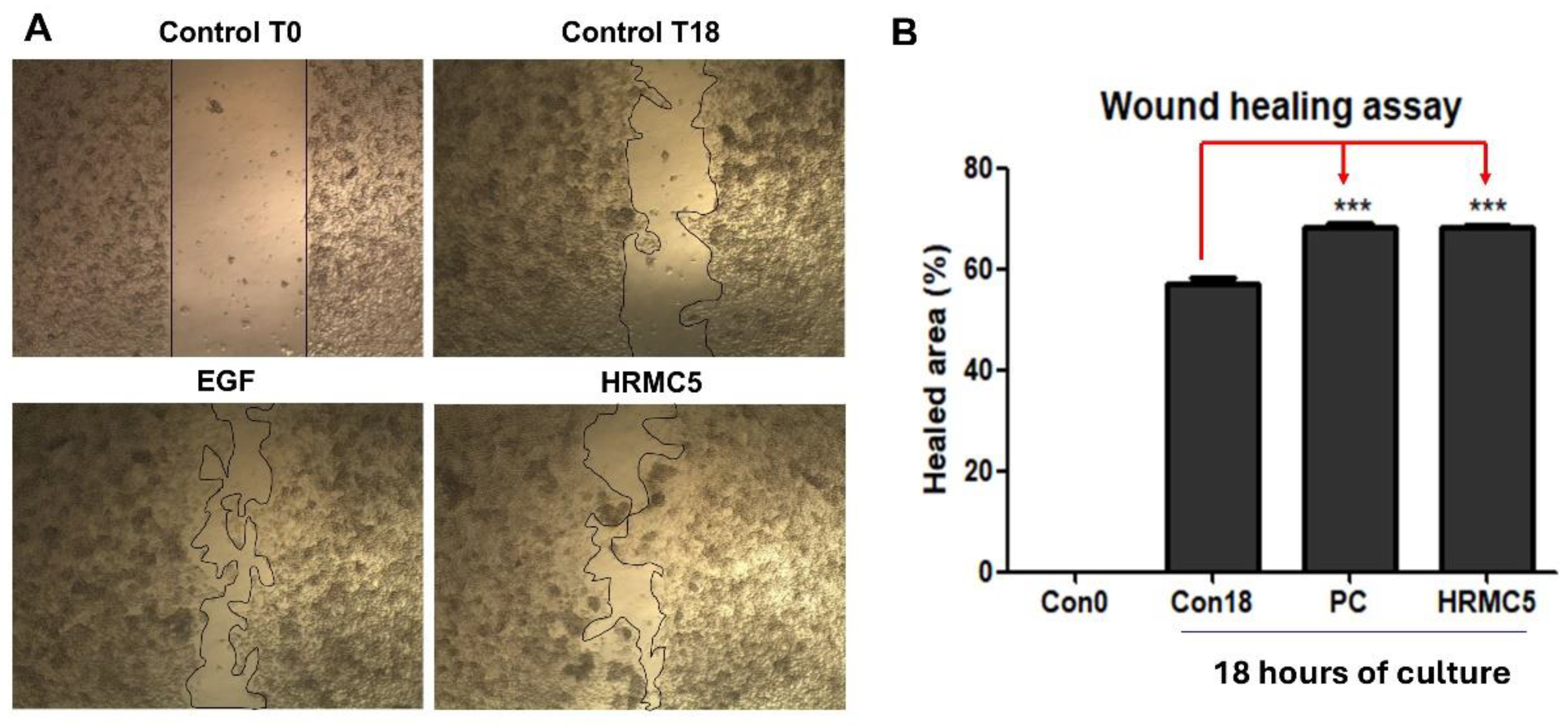

The microscopic images clearly demonstrated that the mixture significantly enhanced the wound healing process compared to the untreated control groups [

38]. Notably, the wound-healing properties of the herbal mixture were significant, as evidenced by enhanced wound closure comparable to the effects of EGF [

39]. Quantitative analysis of the healed area after 18 hours of culture further confirmed these observations, with the mixture showing a statistically significant improvement in wound closure compared to the untreated controls. This result supports the potential of the mixture as a natural alternative or complementary treatment for promoting wound healing. The observed wound-healing efficacy suggests that the herbal extract could offer a safe and effective approach for skin regeneration and tissue repair.

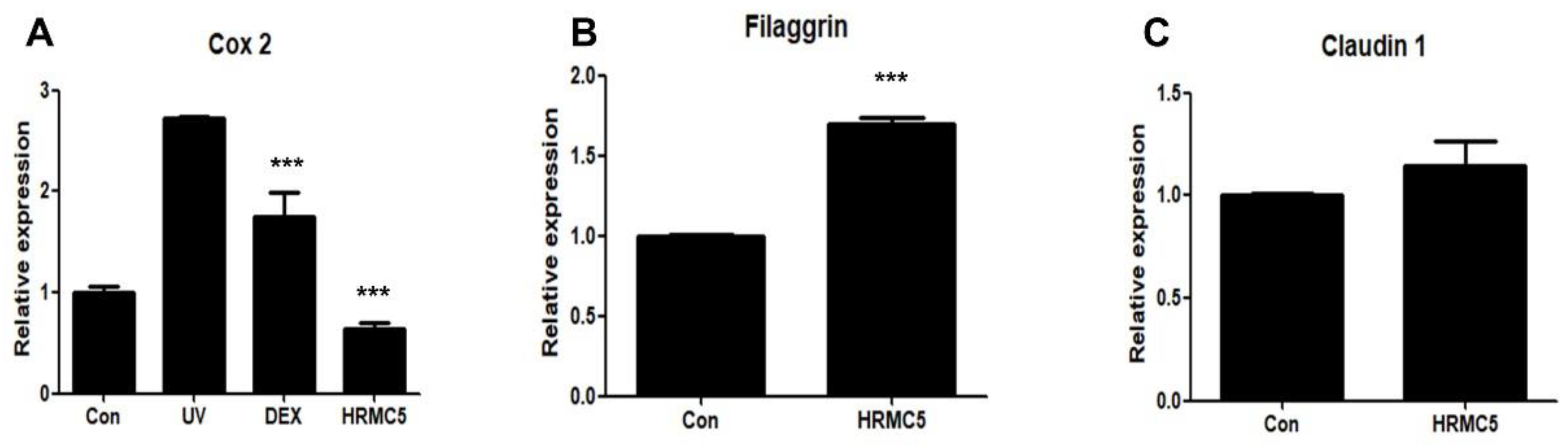

The mixture exhibited anti-inflammatory effects, as evidenced by the reduction in

Cox2 expression, indicating its potential for mitigating UV-induced skin inflammation. This effect may be comparable to dexamethasone, a known anti-inflammatory agent [

40]. Regarding skin barrier function, the mixture showed a tendency to increase Filaggrin expression, a key protein in maintaining skin barrier integrity, though this was not statistically significant. Interestingly, Claudin 1 expression, another important barrier protein, remained unchanged. These results suggest that the herbal extract mixture may have strong anti-inflammatory properties, with limited but promising effects on skin barrier function.

Immunofluorescence staining and analysis showed that the mixture significantly upregulated four key skin barrier proteins: Involucrin, Filaggrin, Claudin 1, and Collagen Type 1. The effects were comparable to or exceeded those of the positive control (1% Glyceryl glucoside), a known enhancer of skin barrier function [

41]. Involucrin and Filaggrin are essential for skin hydration and preventing water loss [

42], while Claudin 1 regulates barrier integrity and permeability [

43]. Collagen Type 1 provides structural support and skin elasticity [

44]. These findings suggest that the mixture strengthens the skin barrier, improves hydration, and may contribute to enhanced skin elasticity and anti-aging effects, highlighting its potential in treating skin barrier dysfunction.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential of a traditional Korean herbal extract mixture for improving skin health. The mixture shows promise in promoting wound healing, reducing inflammation, enhancing skin barrier function, and offering UV protection. These findings lay the groundwork for developing innovative natural remedies for skincare, particularly in products targeting skin barrier dysfunction, inflammation, and facial redness. Further studies should explore the mechanisms underlying these effects and evaluate the clinical applications of this traditional herbal formulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sang Hyun Moh; Data curation, Won Kyong Cho and Euihyun Kim; Formal analysis, Rira Ha, Euihyun Kim and Sung Joo Jang; Investigation, Euihyun Kim, Sung Joo Jang and Ju-Duck Kim; Methodology, Rira Ha, Euihyun Kim and Sung Joo Jang; Project administration, Chang-Geun Yi and Sang Hyun Moh; Supervision, Ju-Duck Kim, Chang-Geun Yi and Sang Hyun Moh; Validation, Rira Ha; Writing – original draft, Rira Ha, Won Kyong Cho and Euihyun Kim; Writing – review & editing, Won Kyong Cho, Chang-Geun Yi and Sang Hyun Moh. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

HPLC analysis of a mixture of five traditional Korean herbal medicine extracts, collectively referred to as HRMC5. (A) Chromatograms of the extract at different wavelengths (210, 254, 280, 330, 360, and 420 nm). (B) Overlay chromatogram of the extract, showing peaks corresponding to 14 identified compounds.

Figure 1.

HPLC analysis of a mixture of five traditional Korean herbal medicine extracts, collectively referred to as HRMC5. (A) Chromatograms of the extract at different wavelengths (210, 254, 280, 330, 360, and 420 nm). (B) Overlay chromatogram of the extract, showing peaks corresponding to 14 identified compounds.

Figure 2.

Effects of HRMC5 on cell survival and UV protection. (A) Survival rate of cells treated with different concentrations of herbal medicine extract. (B) Survival rate of cells treated with herbal medicine extract after UV exposure. Sterile water was utilized as the control while absolute ethanol 1% was used as the positive control (PC). The statistical significance indicators (*, **, and ***) based on the specified levels (0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively).

Figure 2.

Effects of HRMC5 on cell survival and UV protection. (A) Survival rate of cells treated with different concentrations of herbal medicine extract. (B) Survival rate of cells treated with herbal medicine extract after UV exposure. Sterile water was utilized as the control while absolute ethanol 1% was used as the positive control (PC). The statistical significance indicators (*, **, and ***) based on the specified levels (0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively).

Figure 3.

Effect of HRMC5 on wound healing. (A) Microscopic images showing the wound healing process at different time points and treatment conditions. Control T0: untreated control at 0 hours after scratch. Control T18: untreated control at 18 hours after scratch. EGF: positive control treated with epidermal growth factor (100 ng/ml). HRMC5: experimental group treated with a mixture of five herbal medicine extract compounds (0.625 g/L). (B) The percentage of healed area after 18 hours of culture for different treatment groups. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

Figure 3.

Effect of HRMC5 on wound healing. (A) Microscopic images showing the wound healing process at different time points and treatment conditions. Control T0: untreated control at 0 hours after scratch. Control T18: untreated control at 18 hours after scratch. EGF: positive control treated with epidermal growth factor (100 ng/ml). HRMC5: experimental group treated with a mixture of five herbal medicine extract compounds (0.625 g/L). (B) The percentage of healed area after 18 hours of culture for different treatment groups. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

Figure 4.

Effect of HRMC5 on Cox2, Filaggrin, and Claudin 1 gene expression. (A) The relative expression of Cox2, an inflammatory marker, in various treatment groups. The control group received no treatment, while the UV group was exposed to ultraviolet radiation only. The positive control group was treated with dexamethasone (DEX), a known anti-inflammatory agent. The experimental group was treated with HRMC5. (B) The relative expression of Filaggrin encoding a skin barrier protein, in different treatment groups. The control group received no treatment, while the experimental group was treated with HRMC5. (C) The relative expression of Claudin 1 encoding another skin barrier protein, in various treatment groups. The control group received no treatment, while the experimental group was treated with HRMC5. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

Figure 4.

Effect of HRMC5 on Cox2, Filaggrin, and Claudin 1 gene expression. (A) The relative expression of Cox2, an inflammatory marker, in various treatment groups. The control group received no treatment, while the UV group was exposed to ultraviolet radiation only. The positive control group was treated with dexamethasone (DEX), a known anti-inflammatory agent. The experimental group was treated with HRMC5. (B) The relative expression of Filaggrin encoding a skin barrier protein, in different treatment groups. The control group received no treatment, while the experimental group was treated with HRMC5. (C) The relative expression of Claudin 1 encoding another skin barrier protein, in various treatment groups. The control group received no treatment, while the experimental group was treated with HRMC5. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

Figure 5.

Effect of HRMC5 on skin barrier proteins. (A-D) Left panels: Representative immunofluorescence staining images of (A) Involucrin, (B) Filaggrin, (C) Claudin 1 (all green), and (D) Collagen Type 1 (red) in keratinocytes treated with different concentrations of C5 or positive control (1% Glyceryl glucoside). DAPI (blue) stains cell nuclei. Right panels: Quantification of protein expression relative to the control group for (A) Involucrin, (B) Filaggrin, (C) Claudin 1, and (D) Collagen Type 1. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

Figure 5.

Effect of HRMC5 on skin barrier proteins. (A-D) Left panels: Representative immunofluorescence staining images of (A) Involucrin, (B) Filaggrin, (C) Claudin 1 (all green), and (D) Collagen Type 1 (red) in keratinocytes treated with different concentrations of C5 or positive control (1% Glyceryl glucoside). DAPI (blue) stains cell nuclei. Right panels: Quantification of protein expression relative to the control group for (A) Involucrin, (B) Filaggrin, (C) Claudin 1, and (D) Collagen Type 1. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

Table 1.

Major compounds identified by HPLC analysis in HRMC5. The identified peaks and corresponding compounds from the HPLC analysis of HRMC5 were summarized. HRMC5 contains equal proportions of Cimicifuga racemosa, Paeonia lactiflora, Phellodendron amurense, Rheum rhaponticum, and Scutellaria baicalensis each individually extracted with 70% ethanol.

Table 1.

Major compounds identified by HPLC analysis in HRMC5. The identified peaks and corresponding compounds from the HPLC analysis of HRMC5 were summarized. HRMC5 contains equal proportions of Cimicifuga racemosa, Paeonia lactiflora, Phellodendron amurense, Rheum rhaponticum, and Scutellaria baicalensis each individually extracted with 70% ethanol.

| Peak number |

Retention Time (min) |

Compound |

Herb source |

Notable properties |

| 1 |

34.2 |

Paeoniflorin |

Paeonia lactiflora |

Anti-inflammatory |

| 2 |

36.8 |

Polydatin |

Rheum officinale |

Antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory |

| 3 |

42.3 |

Ferulic acid |

Cimicifuga racemosa |

Antioxidant, anti-aging |

| 4 |

44.2 |

Isoferulic acid |

Cimicifuga racemosa |

Antioxidant |

| 5 |

45.5 |

Rhein-glc |

Rheum officinale |

Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial |

| 6 |

47.9 |

Resveratrol-4'-(6"-galloyl glc) |

Rheum officinale |

Antioxidant,

skin-protecting |

| 7 |

53.5 |

Baicalin |

Scutellaria baicalensis |

Antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory |

| 8 |

56.7 |

Cimicifugic acid F |

Cimicifuga racemosa |

Anti-inflammatory |

| 9 |

57.5 |

Berberine |

Phellodendron amurense |

Antibacterial,

anti-inflammatory |

| 10 |

58.5 |

Wogonoside |

Scutellaria baicalensis |

Antioxidant,

skin-soothing |

| 11 |

64.5 |

Baicalein |

Scutellaria baicalensis |

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant |

| 12 |

71.2 |

Rhein |

Rheum officinale |

Antimicrobial,

anti-inflammatory |

| 13 |

73.0 |

Wogonin |

Scutellaria baicalensis |

Anti-inflammatory, calming |

| 14 |

86.4 |

Emodin |

Rheum officinale |

Antibacterial,

anti-inflammatory |