Submitted:

07 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

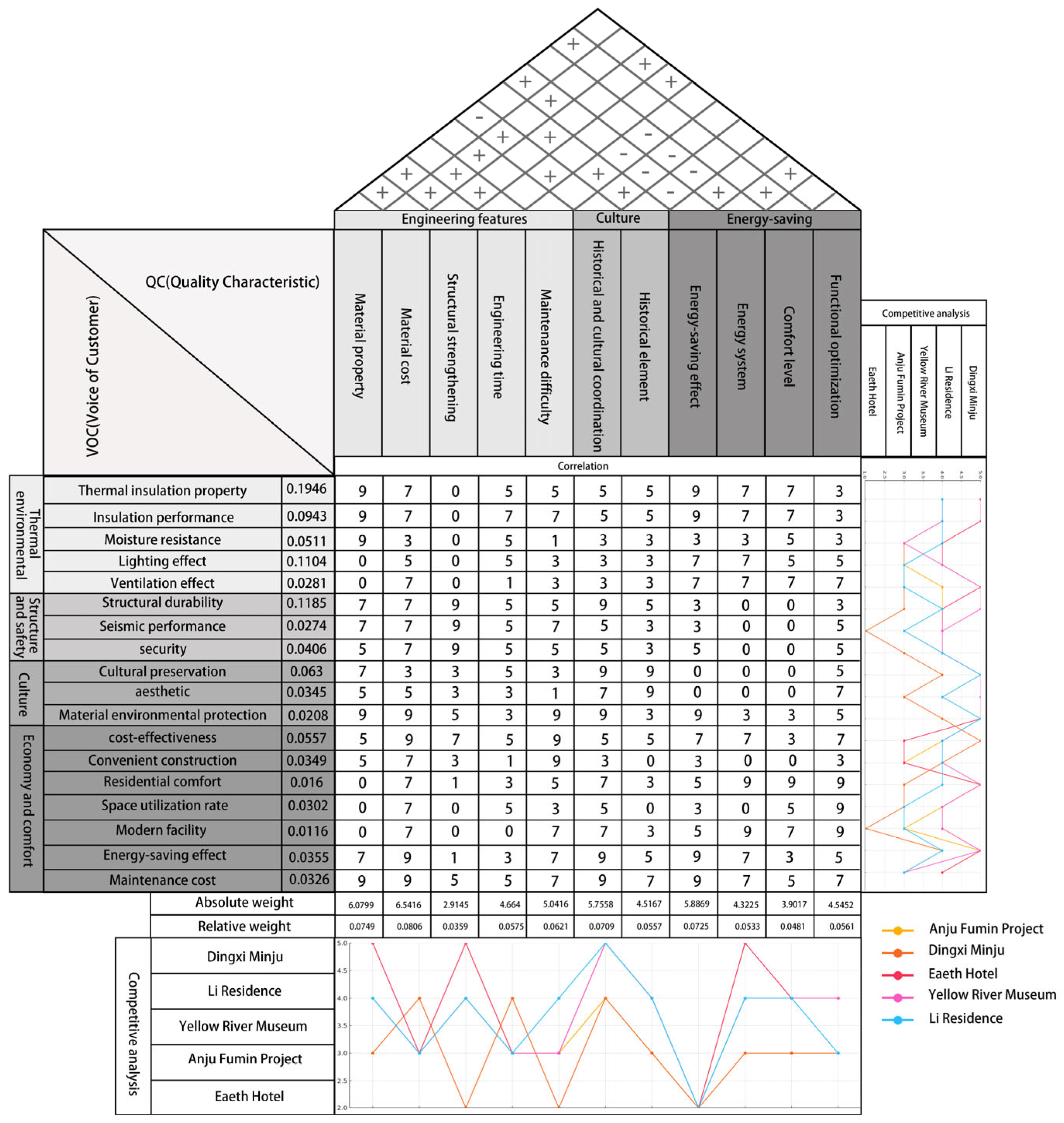

2.2. Quality Function Deployment (QFD)

2.3. Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II)

3. Case Study

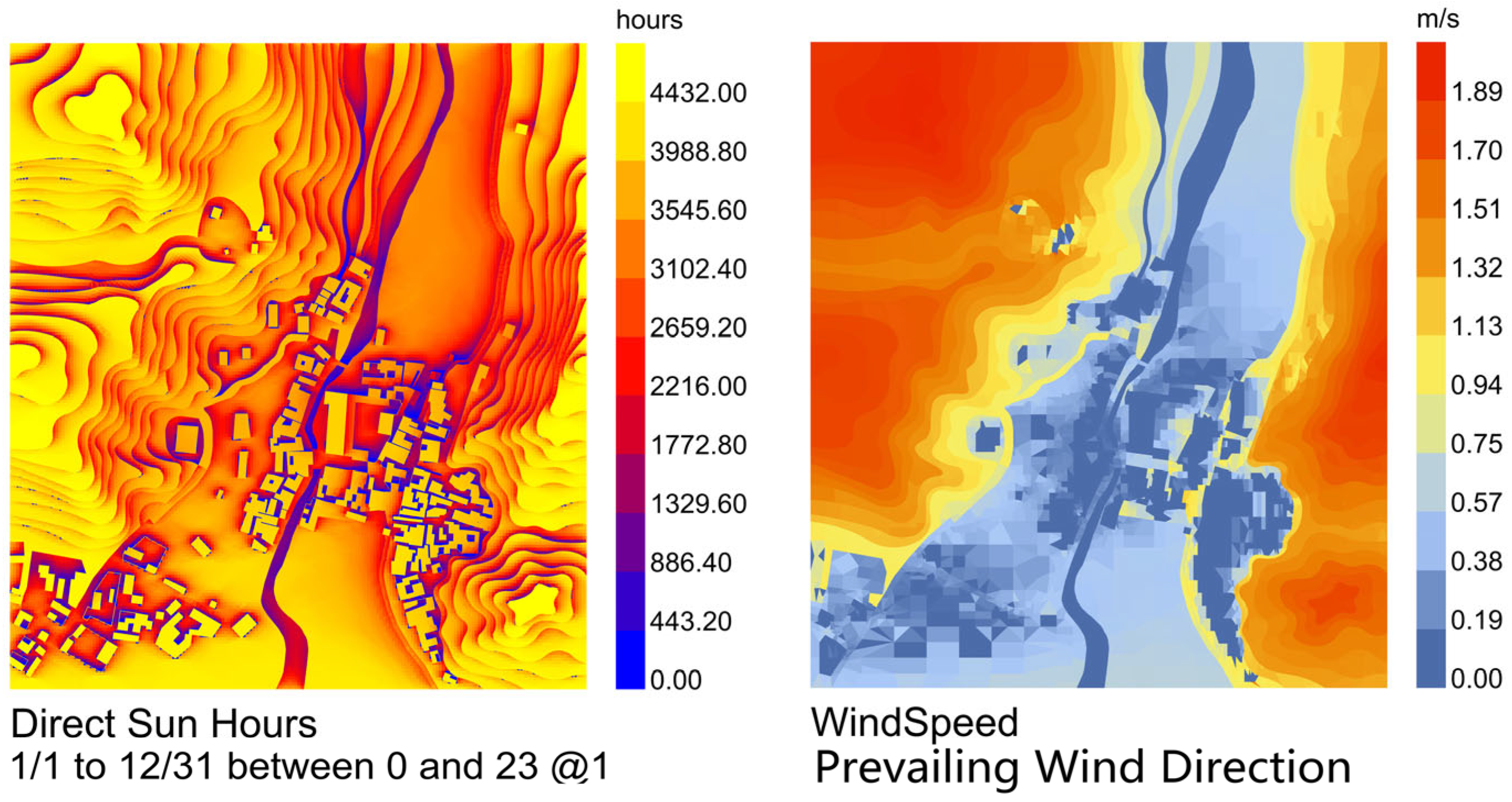

3.1. Overview of Tuyugou Village

3.2. Ecological and Cultural Aspects of Tuyugou Village

4. Research Design

4.2. Priority Ranking Using the AHP Method

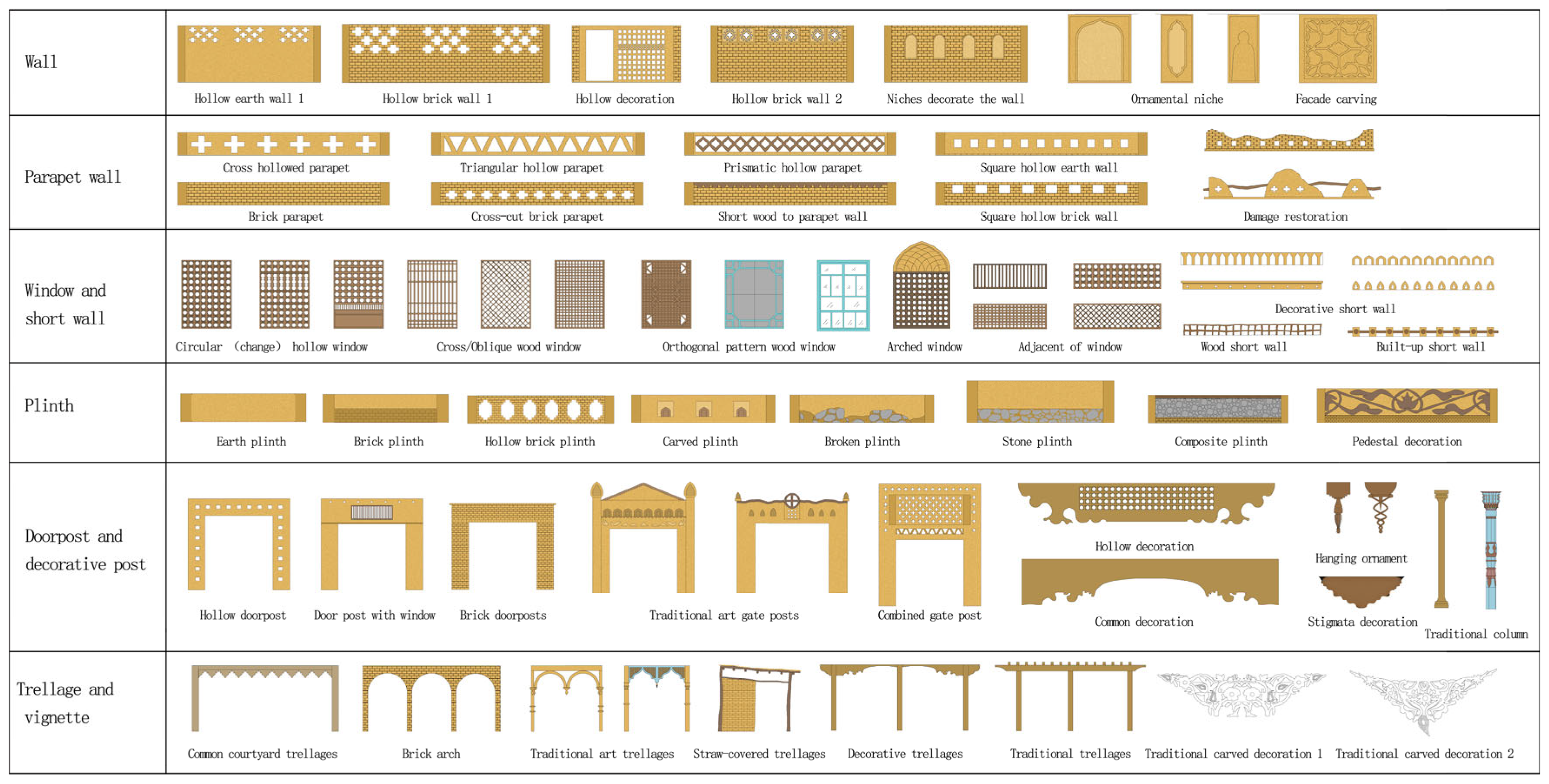

4.3. Determination of Quality Characteristics

4.4. Constructing the Relationship Matrix

4.5. Determining the Priority of Quality Characteristics

4.7. Competitive Analysis:

4.8. Converting Quality Characteristics into Optimization Objective Functions

4.8.1. Developing the Optimization Objective Model for Engineering Characteristics

4.8.2. Stablishing the Cultural Optimization Objective Model:

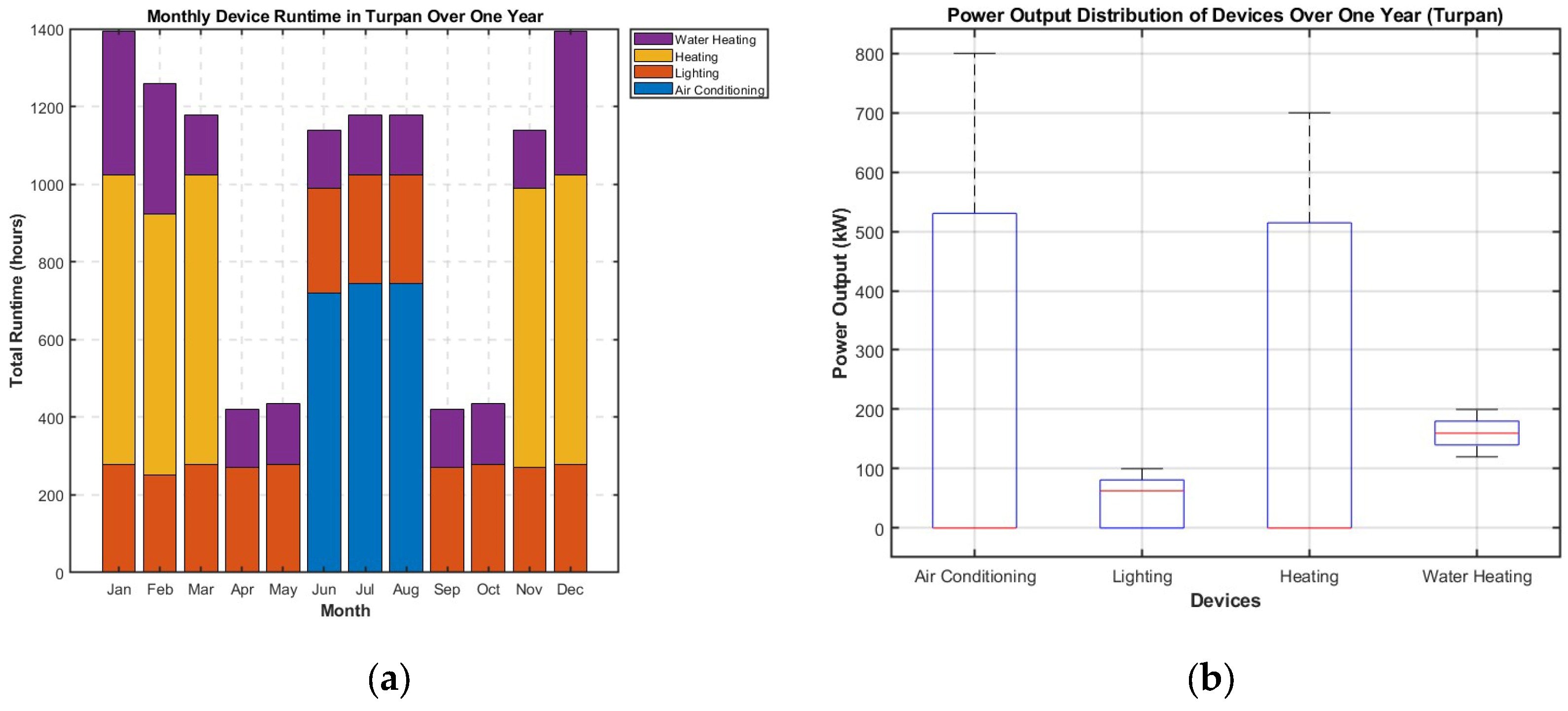

4.8.3. Establishing the Energy-Saving Optimization Objective Model

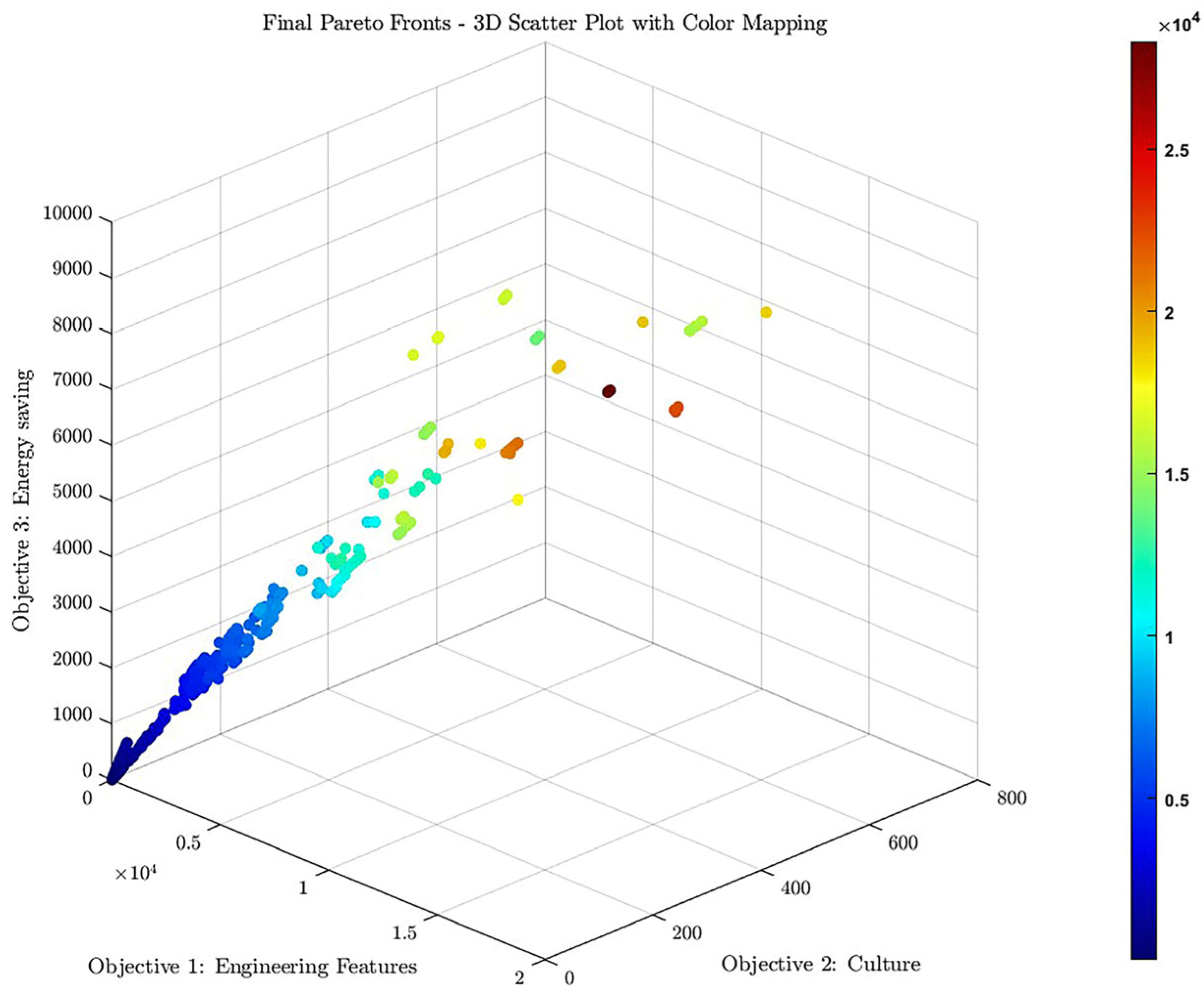

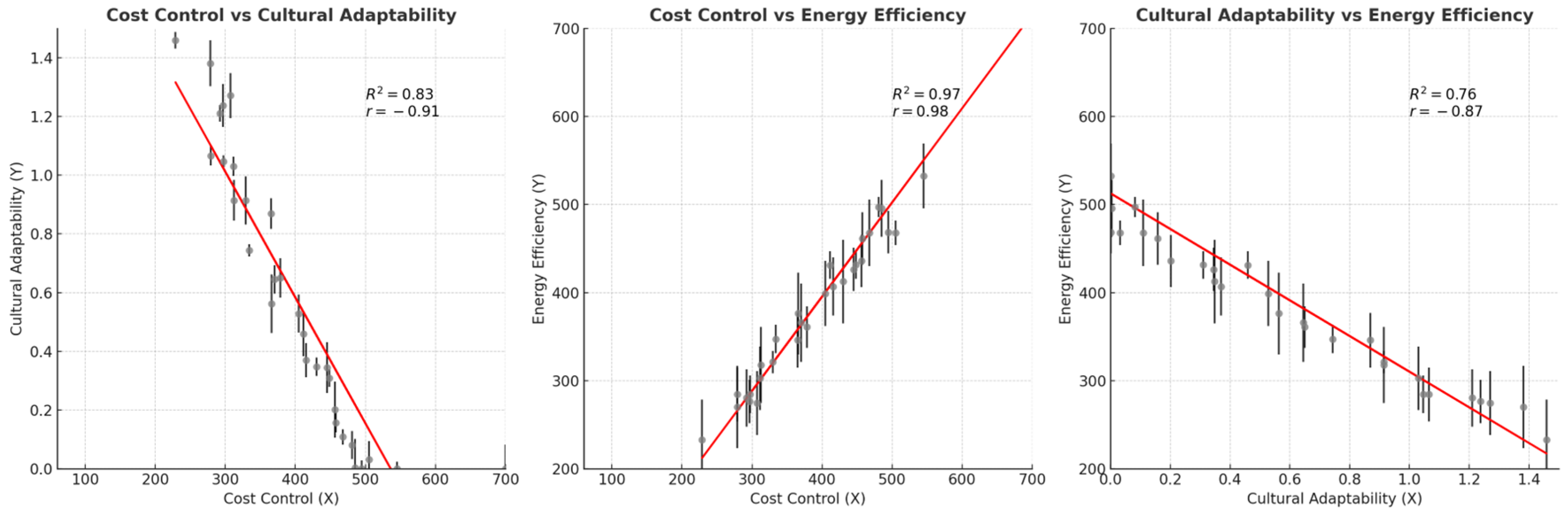

5. Design Results

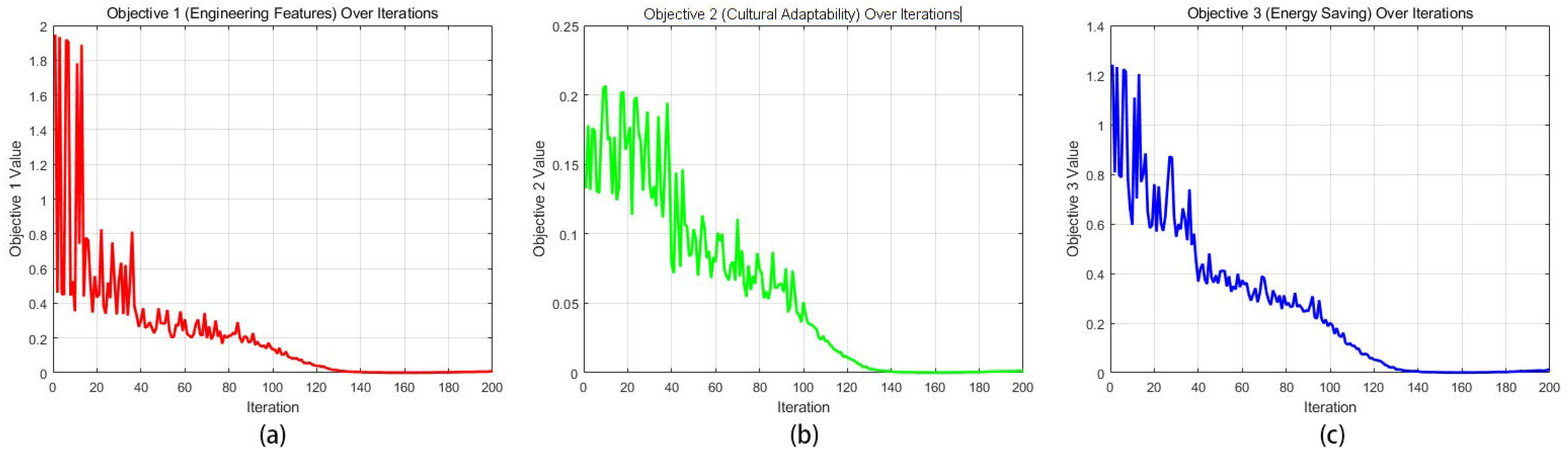

5.1. Parameter Settings

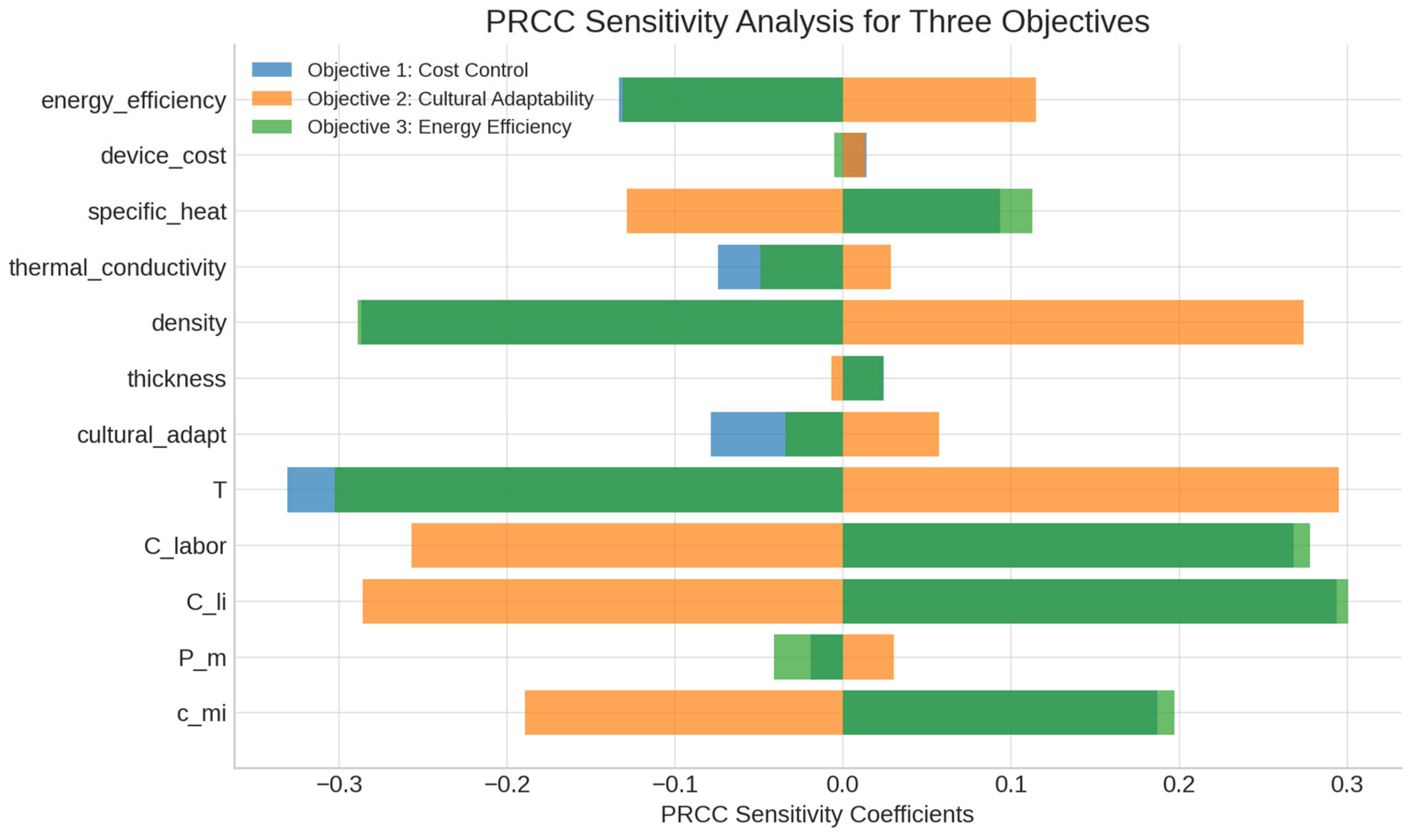

5.2. PRCC Sensitivity Analysis

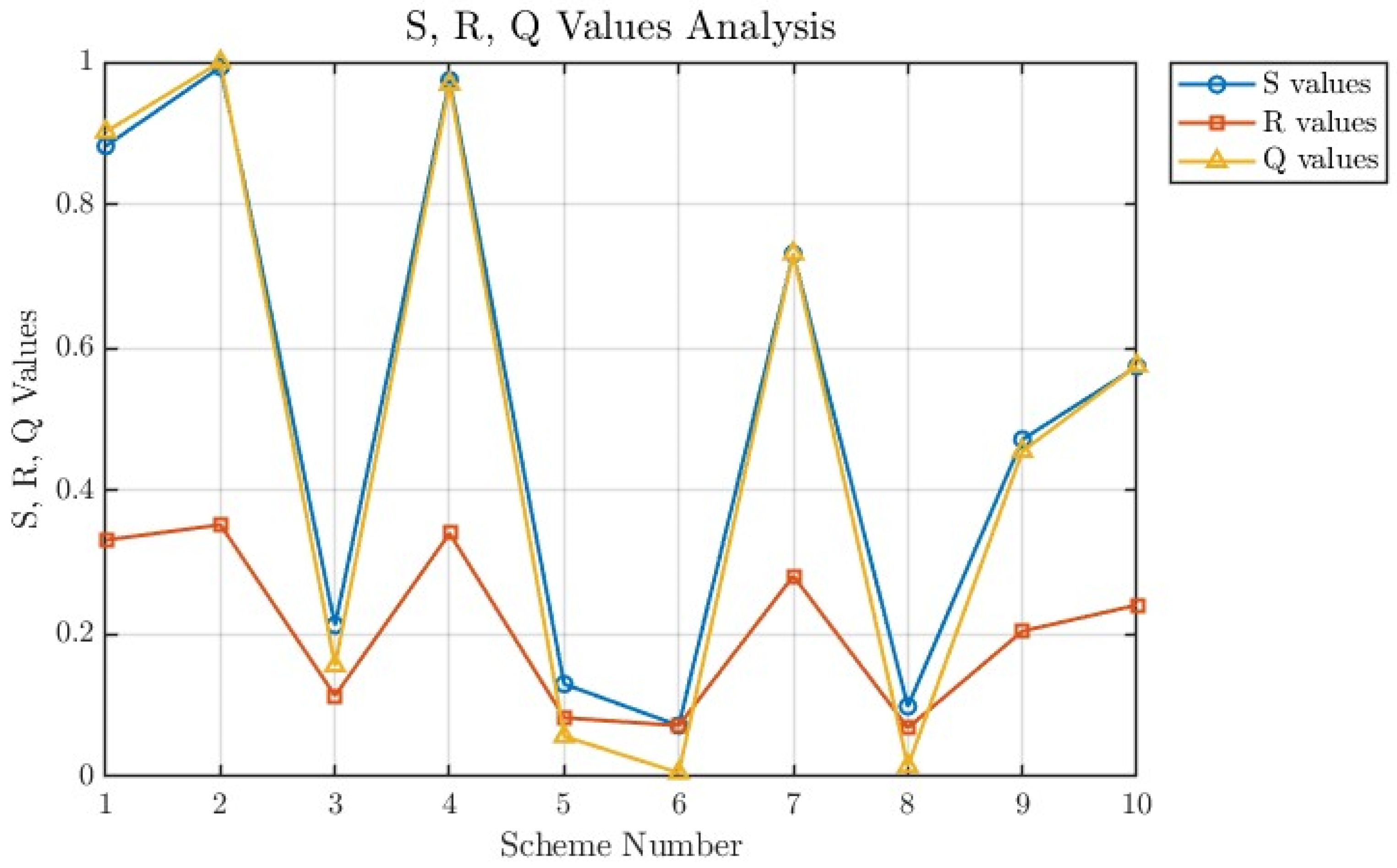

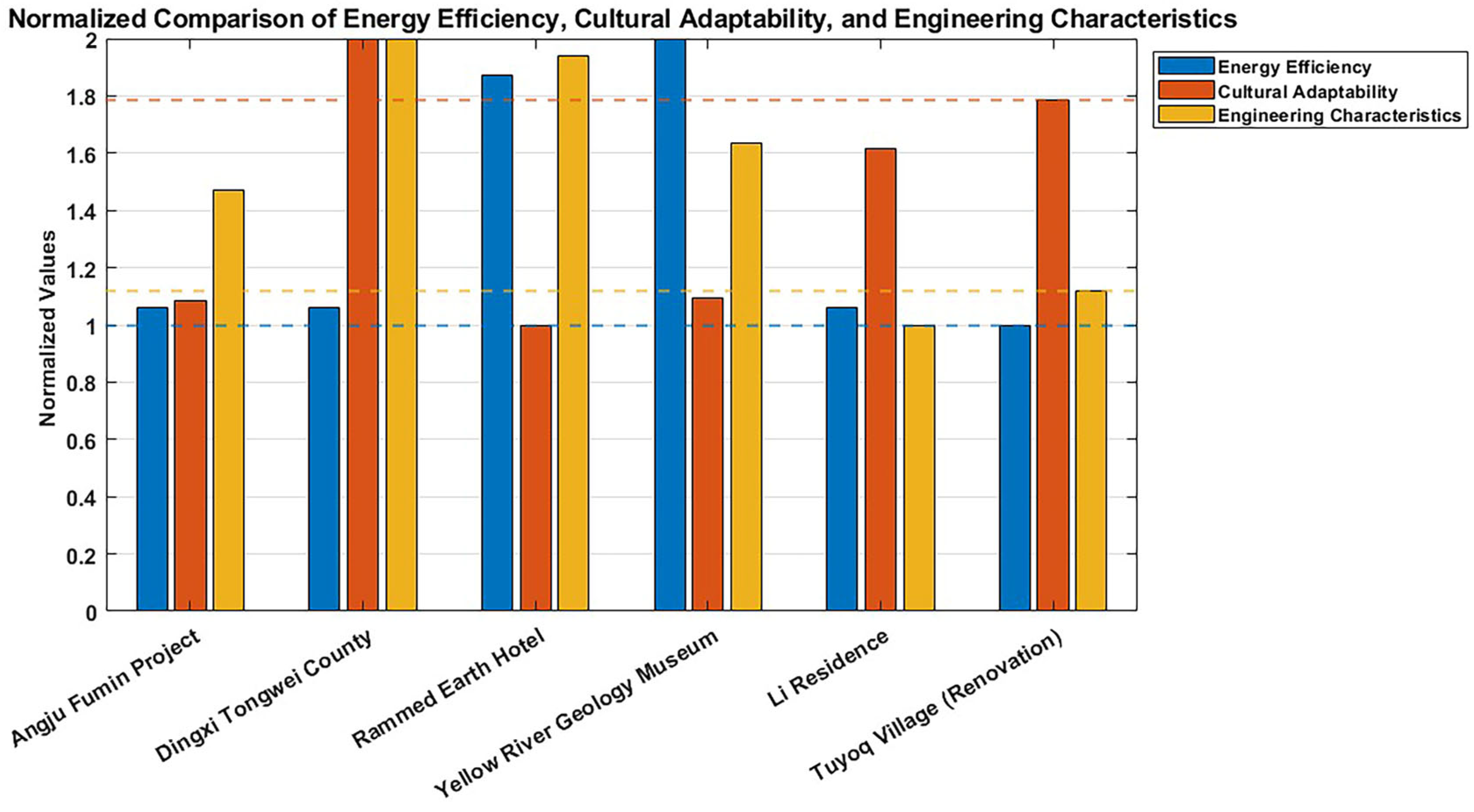

5.3. Entropy Weight -VIKOR Method

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| needs | Weight score | needs | ||||||||||||||||

| Importance ranking | Equally Important |

Importance ranking | ||||||||||||||||

| 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Thermal environmental Performance |

Structure and safety | |||||||||||||||||

| Thermal environmental Performance |

Culture and aesthetics | |||||||||||||||||

| Thermal environmental Performance |

Economy and comfort | |||||||||||||||||

| Structure and safety | Thermal environmental Performance |

|||||||||||||||||

| Structure and safety | Culture and aesthetics | |||||||||||||||||

| Structure and safety | Economy and comfort | |||||||||||||||||

| Culture and aesthetics | Thermal environmental Performance |

|||||||||||||||||

| Culture and aesthetics | Structure and safety | |||||||||||||||||

| Culture and aesthetics | Economy and comfort | |||||||||||||||||

| Economy and comfort | Thermal environmental Performance |

|||||||||||||||||

| Economy and comfort | Structure and safety | |||||||||||||||||

| Economy and comfort | Culture and aesthetics | |||||||||||||||||

| Primary Objective | Quality Characteristic | Detailed Description |

| Engineering Features | Material Property | The characteristics of the material used, including strength, durability, environmental impact, and material sustainability. Examples include concrete, steel, earthen materials, or wood. |

| Material Cost | The cost associated with the acquisition, transportation, and usage of materials such as concrete, steel, wood, or insulation materials. | |

| Structural Strengthening | Techniques and materials used for reinforcing structural stability, such as steel reinforcements, load-bearing walls, and advanced composites. | |

| Engineering Time | The total time required for construction, influenced by material availability, construction techniques, and complexity of design. | |

| Maintenance Difficulty | The level of difficulty and the materials required for maintaining the building over its lifecycle, including wood treatments or repairs to concrete or earthen structures. | |

| Culture | Historical and Cultural Coordination | The use of traditional materials such as adobe, local stone, or wood that align with the historical and cultural heritage of the region. |

| Historical Element | Specific architectural materials like wooden beams, mudbrick walls, or traditional earthen plaster that preserve historical significance. | |

| Energy-Saving | Energy-Saving Effect | The efficiency with which materials (e.g., insulation, energy-efficient windows, solar panels) and design contribute to energy conservation. |

| Energy System | The integration of operational equipment such as HVAC systems, solar power generation, and smart energy meters to optimize energy use. | |

| Comfort Level | The materials used for insulation (e.g., rock wool, Low-E glass) and climate control systems (e.g., air conditioning units, natural ventilation) that provide indoor comfort. | |

| Functional Optimization | Materials and operational systems designed to maximize energy efficiency, such as passive design strategies, adaptive insulation, and energy-efficient appliances. |

References

- He Quan, He Wenfang, Yang Liu, et al. Exploration of new earth-based rural dwelling construction under extreme climate conditions. Journal of Architecture, 9: (11). [CrossRef]

- Zhou Tiegang, Duan Wenqiang, Mu Jun, et al. National survey of earth-based rural houses and statistical analysis of seismic performance. Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture and Technology (Natural Science Edition, 4: 45 (04). [CrossRef]

- Xinhua, L. , Zhaoping, Y., & Xu-ling, L. (2006). Ancient village tourism in Xinjiang - a case study on Tuyuk village in Turpan. Arid Land Geography.

- Yue Bangrui, Li Yuehong, Wang Jun. Study on the morphological characteristics of oasis rural settlements under water resource constraints—Taking Mazha Village in Turpan as an example. Arid Land Resources and Environment, 8: 25(10). [CrossRef]

- Sun Yingkui, Sairjiang Halik. Analysis of protection and renovation strategies for traditional rural dwellings in Turpan region—Taking Mazha Village in Tuyu Gou Township as an example. Journal of Shenyang Jianzhu University (Social Science Edition), 3: 19 (04).

- Luo, Y. & Wu, L. (2020). Protection Status and Development Strategies of Traditional Villages in Northwestern Jiangxi Province. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 780. [CrossRef]

- Yujie Jiang,Ni Li.Ziyue Wang.(2023) Parametric Reconstruction of Traditional Village Morphology Based on the Space Gene Perspective—The Case Study of Xiaoxi Village in Western Hunan, China. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Jing Fu, Jialu Zhou, Yunyuan Deng.(2021) Heritage values of ancient vernacular residences in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China: Spatial patterns and influencing factors. Building and Environment. [CrossRef]

- Layla Iskandar, Ezgi Bay-Sahin, Antonio Martinez-Molina, Saadet Toker Beeson.(2024) Evaluation of passive cooling through natural ventilation strategies in historic residential buildings using CFD simulations. Energy & Buildings. [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, B.A. Coelho, Hugo Entradas Silva, Fernando M.A. Henriques.(2020) Impact of climate change in cultural heritage: from energy consumption to artefacts’ conservation and building rehabilitation. Energy & Buildings. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y. , Zhai, H., Teoh, B., Tiong, R., Huang, S., Cen, D., & Cui, C. (2023). A Data-Driven Method for Constructing the Spatial Database of Traditional Villages—A Case Study of Courtyard Residential Typologies in Yunnan, China. Buildings. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. , Qiu, L., & Fu, X. (2021). Toward Cultural Heritage Sustainability through Participatory Planning Based on Investigation of the Value Perceptions and Preservation Attitudes: Qing Mu Chuan, China. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Coyle, G. (2004). Analytic Hierarchy Process ( AHP ). [CrossRef]

- Carnevalli, J.A. and Miguel, P.C., 2008. Review, analysis and classification of the literature on QFD—Types of research, difficulties and benefits. International Journal of Production Economics, 114, pp.737-754. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, E. , Silva, M., Antunes, C.H. and Dias, L., 2012. Multi-objective optimization for building retrofit strategies: A model and an application. Energy and Buildings, 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Kamaruzzaman, S. , Lou, E., Wong, P. F., Wood, R. and Che-Ani, A., 2018. Developing weighting system for refurbishment building assessment scheme in Malaysia through analytic hierarchy process (AHP) approach. Energy Policy, 280–290. [CrossRef]

- Aminbakhsh, S. , Gunduz, M. and Sonmez, R., 2013. Safety risk assessment using analytic hierarchy process (AHP) during planning and budgeting of construction projects. Journal of Safety Research, 99–105. [CrossRef]

- Adinyira, E. , Kwofie, T., & Quarcoo, F. (2018). Stakeholder requirements for building energy efficiency in mass housing delivery: the House of Quality approach. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhaputtangkul, N. , Low, S., Teo, A. & Hwang, B., 2013. Knowledge-based Decision Support System Quality Function Deployment (KBDSS-QFD) tool for assessment of building envelopes. Automation in Construction. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S. , Pant, M., & Snás̃el, V., 2021. A Comprehensive Review on NSGA-II for Multi-Objective Combinatorial Optimization Problems. IEEE Access, 5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G. , Li, R., & Yang, Y., 2023. An Improved Multi-Objective Optimization and Decision-Making Method on Construction Sites Layout of Prefabricated Buildings. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. & Song, B., 2010. Multiple project scheduling based on an improved hybrid genetic algorithm. The 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering, pp. 351-354. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W. , Li, B., Jia, H., Zhang, M., & Wang, D. (2015). Application of multi-objective genetic algorithm to optimize energy efficiency and thermal comfort in building design. Energy and Buildings. [CrossRef]

- Yang Xiaofeng, Zhou Ruoqi. Traditional rural dwellings and village environment in Tuyu Gou Mazha Village, Turpan. Journal of Architecture, 3: (04).

- Ye Jianming, Ma Ling, Liu Binyi, et al. Ecological adaptability analysis of Mazha Village in Turpan. Small Town Construction, 1: 41(11).

- Li Cheng. Research on climate suitability and renewal of earth-based rural dwellings in Turpan area [D]. Xi'an University of Architecture and Technology, 2015.

- Li, J. , Peng, X., Li, C., Luo, Q., Peng, S., Tang, H., & Tang, R., 2023. Renovation of Traditional Residential Buildings in Lijiang Based on AHP-QFD Methodology: A Case Study of the Wenzhi Village. Buildings. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. (2000). On consistency of the weighted geometric mean complex judgement matrix in AHP. Eur. J. Oper. Res. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L. , Santos, H., Almeida, M., & Costa, J. (2020). Quality Function Deployment and Analytic Hierarchy Process: A literature review of their joint application. Concurrent Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Min Rui, Sun Tongyu. Conservation and renewal strategies of native soil buildings in Longzhong Area in the context of rural revitalization: A case study of Tongwei County, Dingxi City, Gansu Province. Western living environment journal, 6: 35 (01).

- Deng Bowei. Research on Suitable Structure Design of modern rammed earth Hotel in Northern Xinjiang [D]. Xi 'an University of Architecture and Technology, China, 2018.

- Wang Fang, Wang Li. Application of Green Ecological Strategy in the Reconstruction of traditional soil buildings: A case study of the architectural design of the Yellow River and Loess Geological Museum in Mangshan, Zhengzhou. Journal of Building Science, 2: 30 (02). [CrossRef]

- Zhao Mingqiao, Wei Zhe, Xie Min, et al. Research on the renewal of traditional soil architecture in Hunan Province. Chinese and Foreign Architecture, 1: (01). [CrossRef]

- Guo, H. , & Lu, W. (2022). Measuring competitiveness with data-driven principal component analysis: a case study of Chinese international construction companies. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. [CrossRef]

- Chen Zhendong. Xinjiang Residential Dwellings [M], 2009.

- Xie, L. , Wang, D., Zhao, H., Gao, J., & Gallo, T. (2021). Architectural energetics for rammed-earth compaction in the context of Neolithic to early Bronze Age urban sites in Middle Yellow River Valley, China. Journal of Archaeological Science. [CrossRef]

- Ferroukhi, M. , Belarbi, R., Limam, K., Larbi, A., & Nouviaire, A. (2018). Assessment of the effects of temperature and moisture content on the hygrothermal transport and storage properties of porous building materials. Heat and Mass Transfer, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojih, J. , Onyekpe, U., Rodriguez, A., Hu, J., Peng, C., & Hu, M. (2022). Machine Learning Accelerated Discovery of Promising Thermal Energy Storage Materials with High Heat Capacity. ACS applied materials & interfaces. [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F. , Bianco, N., Mauro, G. M., & Napolitano, D. (2019). Retrofit of villas on Mediterranean coastlines: Pareto optimization with a view to energy-efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Applied Energy. [CrossRef]

- Mavrotas, G. , & Diakoulaki, D. (2005). Multi-criteria decision analysis with the combination of multi-objective mathematical programming and hierarchical trade-off weighting: An application to energy planning. European Journal of Operational Research, 165(2), pp.459-468. [CrossRef]

- Merabet, G. , Essaaidi, M., Haddou, M., Qolomany, B., Qadir, J., Anan, M., Al-Fuqaha, A., Abid, M., & Benhaddou, D. (2021). Intelligent Building Control Systems for Thermal Comfort and Energy-Efficiency: A Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Techniques. ArXiv, 0221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemshadi, A. , Shirazi, H. ( 38, 12160–12167. [CrossRef]

- Arya, V. , & Kumar, S., 2020. A new picture fuzzy information measure based on Shannon entropy with applications in opinion polls using extended VIKOR–TODIM approach. Computational and Applied Mathematics. [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y. , & Wang, A. (2013). Extension of VIKOR method for multi-criteria group decision making problem with linguistic information. Applied Mathematical Modelling, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Main Needs | Key Concerns | Group Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Residents | Living comfort, energy efficiency, maintenance costs, cultural heritage preservation | mproving quality of life, balancing cultural heritage with modern living needs | Sensitive to comfort and living costs, highly value cultural and emotional attachment |

| Tourists | Cultural experience, comfort, safety, aesthetic experience | Preserving cultural atmosphere, ensuring comfort in the living experience | Short-term visitors, focused on appearance and cultural features |

| Professionals in the Construction Industry | Innovative design, technical feasibility, cost control | Combining innovation with tradition, improving functionality and durability | Focus on innovation and technical feasibility, concerned with balancing cost and quality |

| Relevant Government Departments | Policy implementation, economic and cultural benefits, cultural preservation | Guiding renovation direction, balancing cultural preservation with economic development | Balancing local development with cultural preservation, focused on the long-term benefits of the project |

| Level 1 Indicator | Level 2 Indicator | Same Level Weight | Comprehensive Weight | Ranking | Consistency Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal environmental performance | thermal insulation | 0.4067 | 0.1946 | 3 | 0.02335 |

| heat preservation | 0.1971 | 0.0943 | 5 | ||

| dampproof | 0.1069 | 0.0511 | 13 | ||

| lighting | 0.2307 | 0.1104 | 14 | ||

| ventilation | 0.0586 | 0.0281 | 17 | ||

| Structure and safety | durability | 0.6352 | 0.1185 | 1 | 0.0121 |

| earthquake resistance | 0.1469 | 0.0274 | 10 | ||

| safety | 0.2179 | 0.0406 | 15 | ||

| Culture and aesthetics | cultural preservation | 0.5328 | 0.0630 | 2 | 0.0362 |

| aesthetic | 0.2913 | 0.0345 | 4 | ||

| environmental protection material | 0.2913 | 0.0208 | 6 | ||

| Economy and comfort | cost effectiveness | 0.2574 | 0.0557 | 12 | 0.013 |

| construction convenience | 0.1612 | 0.0349 | 8 | ||

| residential comfort | 0.0739 | 0.0160 | 16 | ||

| space utilization | 0.1393 | 0.0302 | 11 | ||

| modern facilities | 0.1393 | 0.0116 | 18 | ||

| energy saving | 0.1393 | 0.0355 | 7 | ||

| maintenance costs | 0.1505 | 0.0326 | 9 |

| Category | Material | Unit Price (RMB) | Maintenance Cost (RMB/year) | Maintenance Period | Durability (Years) | Cultural Adaptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Enclosure Material | Raw Earth | 25/m³ | 25 (RMB/year/m³) | 5-10 years | 35 | 0.9 |

| Modified Raw Earth | 75/m³ | 18 (RMB/year/m³) | 10-20 years | 50 | 0.85 | |

| Brick | 238/m³ | 5-15 (RMB/year/m³) | 20-30 years | 70 | 0.6 | |

| Local Wood | 1120/m³ | 50-100 (RMB/year/m³) | 5-15 years | 50 | 0.85 | |

| Modern Enclosure Material | Concrete | 455/m³ | 20-50 (RMB/year/m³) | 30-50 years | 100 | 0.3 |

| Steel | 27082.5/m³ | 100-200 (RMB/year/m³) | 20-40 years | 100 | 0.2 | |

| Glass Material | Ordinary Glass | 65/㎡ | 10-30 (RMB/year/㎡) | 10-20 years | 50 | 0.65 |

| Low-E Insulated Glass | 360/㎡ | 20-50 (RMB/year/㎡) | 20-30 years | 40 | 0.2 | |

| Insulation Material | 50mm Rock Wool Insulation Board | 65/㎡ | 11 (RMB/year/㎡) | 15-25 years | 35 | 0.25 |

| 50mm Glass Wool Insulation Material | 25/㎡ | 9 (RMB/year/㎡) | 15-25 years | 40 | 0.15 | |

| 20mm Polyurethane (PU) | 128/㎡ | 13 (RMB/year/㎡) | 10-20 years | 30 | 0.1 | |

| 20mm EPS Exterior Wall Insulation Board | 95/㎡ | 7 (RMB/year/㎡) | 15-25 years | 35 | 0.2 |

| Job Type | Labor Cost (RMB/day) | Duration (Days) |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation Construction Worker | 210 | 20 |

| Raw Earth Construction Worker | 220 | 18 |

| Modified Raw Earth Construction Worker | 230 | 22 |

| Brick Construction Worker | 250 | 25 |

| Concrete Construction Worker (Long) | 260 | 30 |

| Concrete Construction Worker (Short) | 240 | 20 |

| Glass Installation Worker | 250 | 15 |

| Insulation Material Construction Worker | 230 | 15 |

| Electrical Installation Worker | 270 | 10 |

| Traditional Decorative Arts Worker | 300 | 5-30 |

| Equipment | Category | Energy Efficiency Level | Cost (RMB) | Energy Utilization | Energy Consumption (kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air conditioning equipment | Wall-mounted air conditioning | I, II, III | 2000 - 5000 | I: Energy efficiency ≥ 4.5 (SEER standard) Ⅱ: Energy efficiency 3.9-4.5 Ⅲ: Energy efficiency 3.5-3.9 |

I: 0.33 |

| Mobile air conditioning | I, II, III | 1000 - 3000 | I: 0.29 | ||

| lighting equipment | LED Lamp | I | 200 | I: ≥ 210 lm/w (LED) I: ≥ 90 lm/w |

I: 0.01 |

| Energy-saving Lamp | I, II, III | 10 - 50 | I: 0.015 | ||

| Heating equipment | Wall-hanging stove | I, II, III | 300 - 2000 | I: Heat efficiency ≥ 98% | I: 0.01 |

| Electric radiator | None | 300-2000 | None | 1.96 | |

| Underfloor heating | None | 2000 - 5000 | None | 5 | |

| Hot water facilities | Electric water heater | I, II, III | 1000-5000 | Ⅰ: Energy efficiency ratio ≥ 0.9 Ⅱ: Energy efficiency ratio between 0.8-0.9 Ⅲ: Energy efficiency ratio between 0.7-0.8 |

Ⅰ级: 2.22 Ⅱ级: 2.35 Ⅲ级: 2.67 |

| Gas water heater | I, II, III | 1000 - 15000 | I: 2.2 | ||

| Solar water heater | None | 3000 - 15000 | None |

| Material Type | Thickness (mm) | Density (kg/m³) | Thermal Conductivity [W/(m·K)] | Thermal Storage Coefficient S [W/(m²·K)] | Specific Heat C [kJ/(kg·K)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Earth | 500 | 1800 | 0.93 | 11.03 | 1.01 |

| Modified Raw Earth | 500 | 1700 | 0.58 | 7.69 | 1.01 |

| Brick | 500 | 1800 | 0.81 | 9.96 | 1.05 |

| Local Wood | 50 | 500 | 0.14 | 3.85 | 2.51 |

| Concrete | 400 | 2500 | 1.74 | 17.2 | 0.92 |

| Steel | 20 | 7850 | 58.2 | 126 | 0.48 |

| Glass | 5 | 2500 | 0.76 | 10.69 | 0.84 |

| Rock Wool Insulation Board | 20 | 120 | 0.041 | 0.45 | 1.22 |

| Glass Wool Insulation Material | 20 | 40 | 0.035 | 0.35 | 1.22 |

| Polyurethane (PU) | 20 | 35 | 0.024 | 0.29 | 1.38 |

| EPS Exterior Wall Insulation Board | 20 | 20 | 0.047 | 0.7 | 1.38 |

| Number of schemes | Objective 1 | Objective 2 | Objective 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 463.256 | 0.2206 | 510.68 |

| 2 | 487.645 | 0.0053 | 517.559 |

| 3 | 389.281 | 1.0441 | 309.324 |

| 4 | 491.14 | 0.0569 | 509.351 |

| 5 | 342.984 | 1.3529 | 359.501 |

| 6 | 340.566 | 1.5364 | 352.793 |

| 7 | 444.202 | 0.3164 | 455.745 |

| 8 | 341.584 | 1.4151 | 350.897 |

| 9 | 396.549 | 0.6516 | 403.486 |

| 10 | 415.835 | 0.4931 | 419.515 |

| Evaluation Criteria | Engineering features | Culture | Energy-saving |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy Values | 0.8628 | 0.8414 | 0.8459 |

| Weights | 0.3050 | 0.3525 | 0.3425 |

| Ranking | 6 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scores | 0.0319 | 0.0391 | 0.0716 | 0.1484 | 0.3816 | 0.4744 | 0.5968 | 0.7292 | 0.7812 | 0.8050 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).