Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

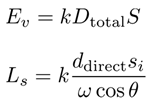

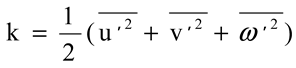

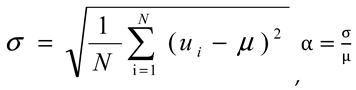

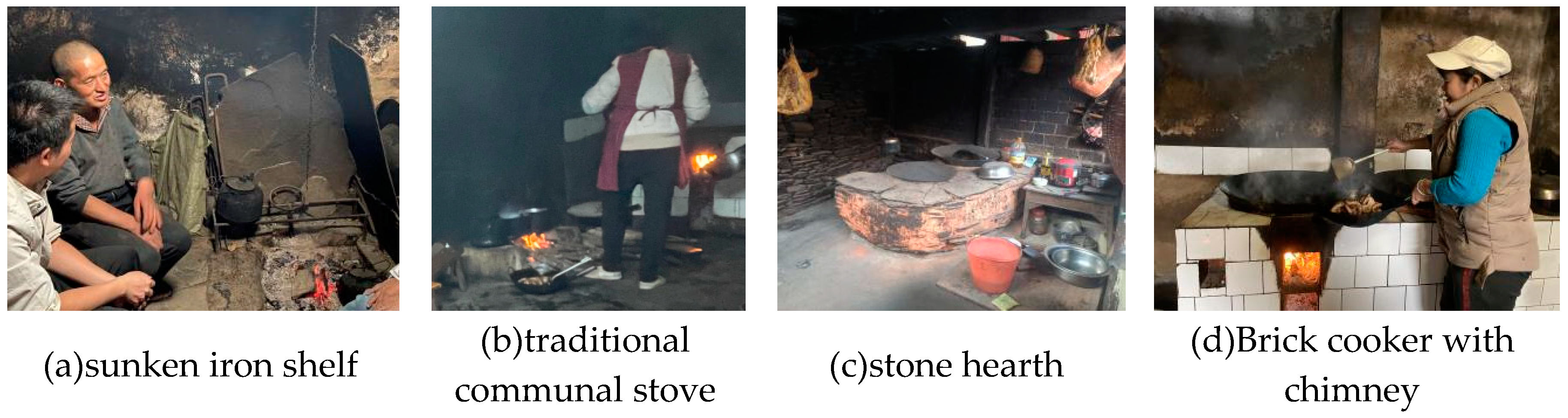

1.1. Rural Kitchen Characteristics

| Renovation Case | Renovation method | Transformation results and experience |

|---|---|---|

| Huayao kitchen in a rural house in Chongmutang Village, Hunan Province 1 |

|

|

| Elderly-friendly kitchen in Shanting Town, Fujian |

|

|

| Cleaning kitchen in Lijiahe Village, Linxia Prefecture, Gansu |

|

|

| Kitchen reform in rural areas of southern Anhui 2 |

|

|

1.2. Tangfang Village Kitchen Evolution

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics Basic Strategies for Kitchen Renovation

2.2. Low-Tech Transformation Strategy

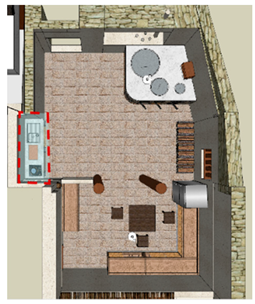

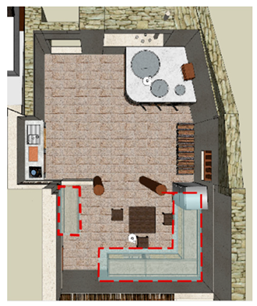

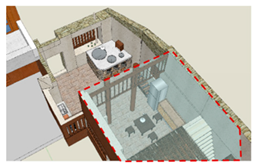

2.3. Renovation Plan:

2.3.1. Existing Problems

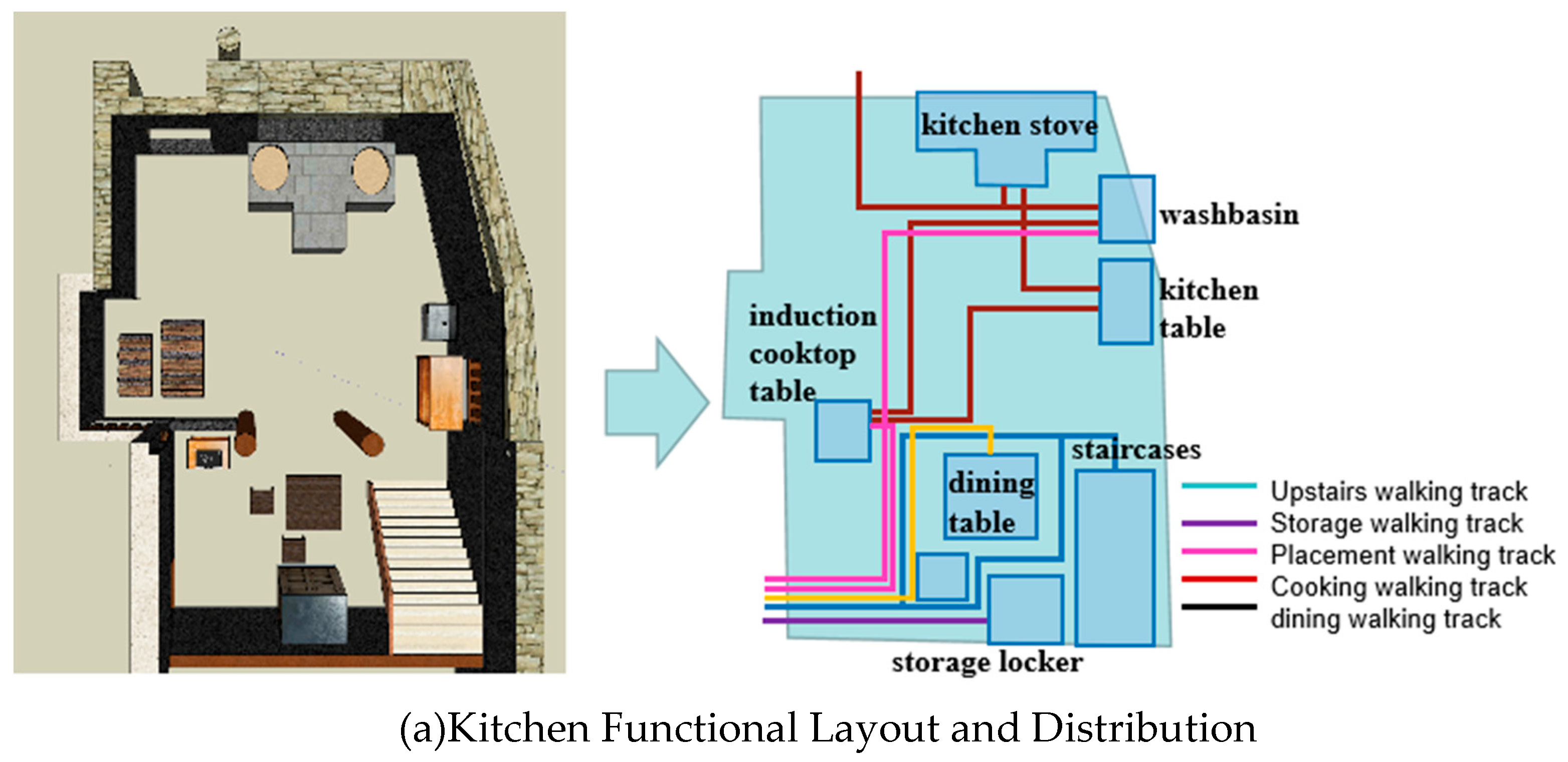

- Functional flow problem:

- 2.

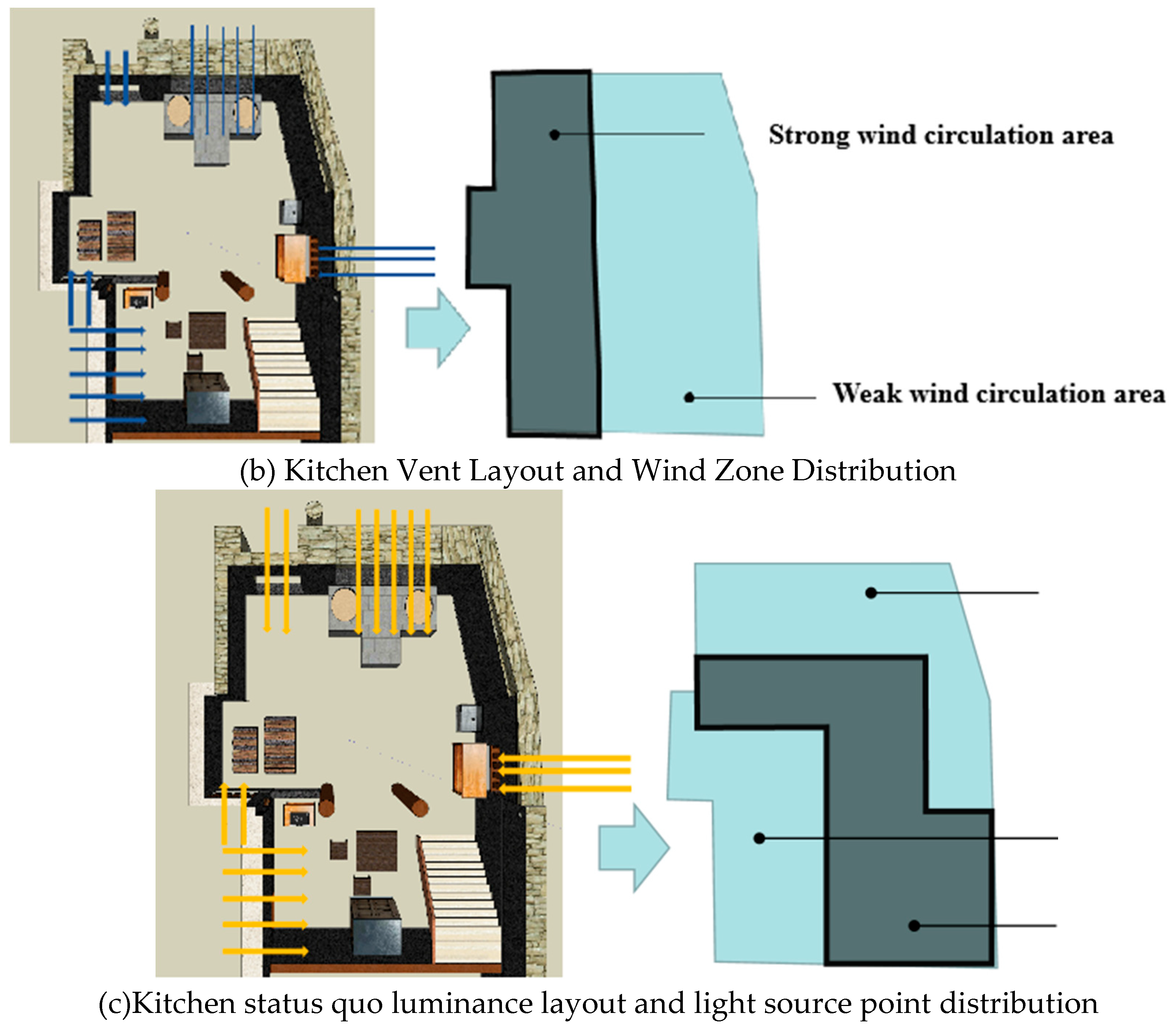

- Ventilation issues:

- 3.

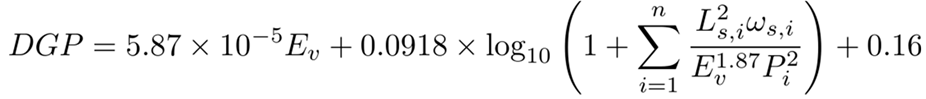

- Lighting issues:

- 4.

- Water supply and drainage issues:

- 5.

- Housing structure problems:

2.3.2. Low-Tech Transformation Measures

- 1.

- Functional Flow

- 2.

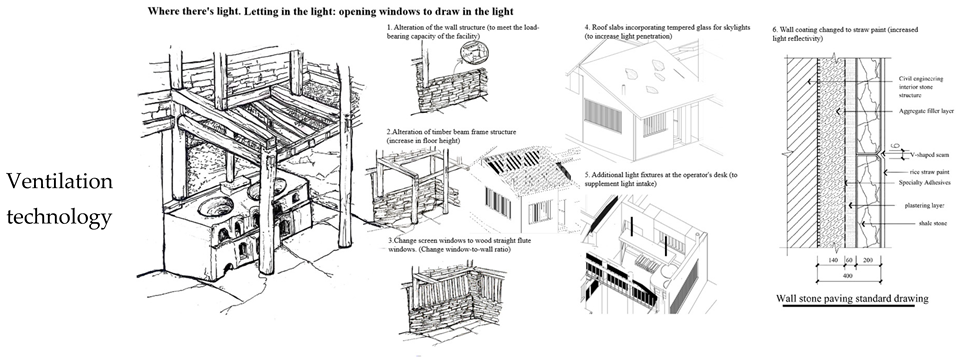

- Ventilation technology

- 3.

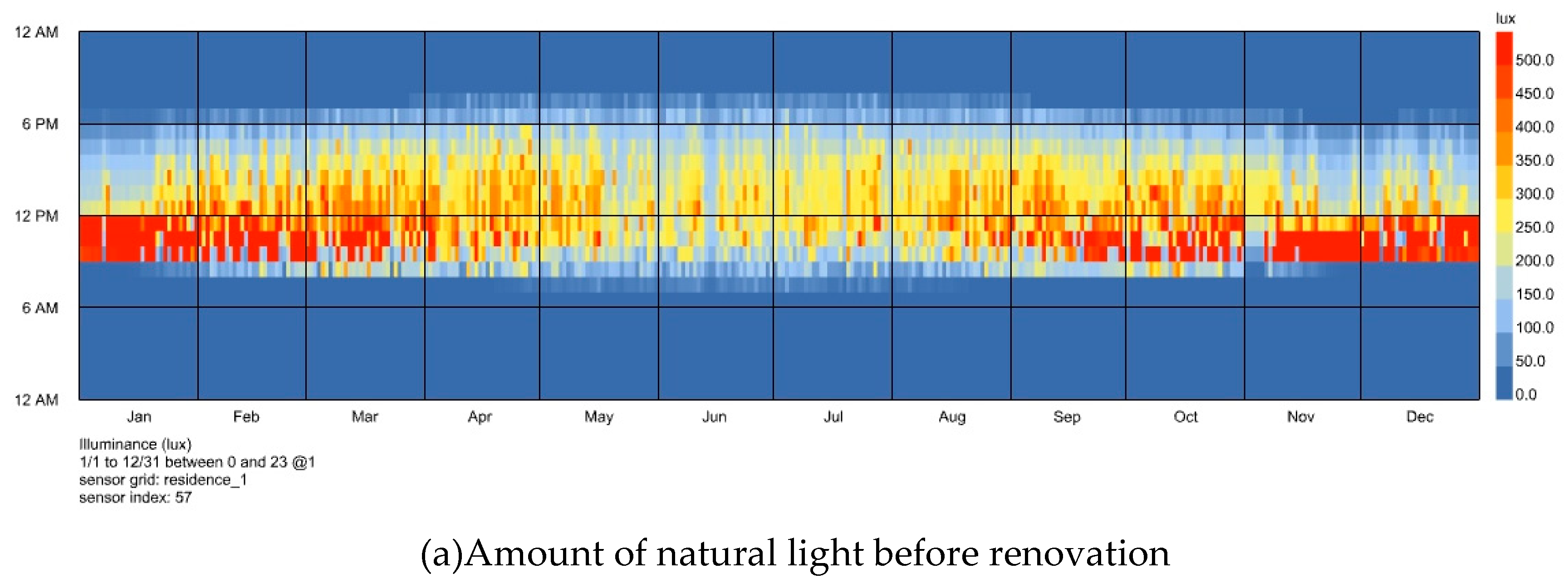

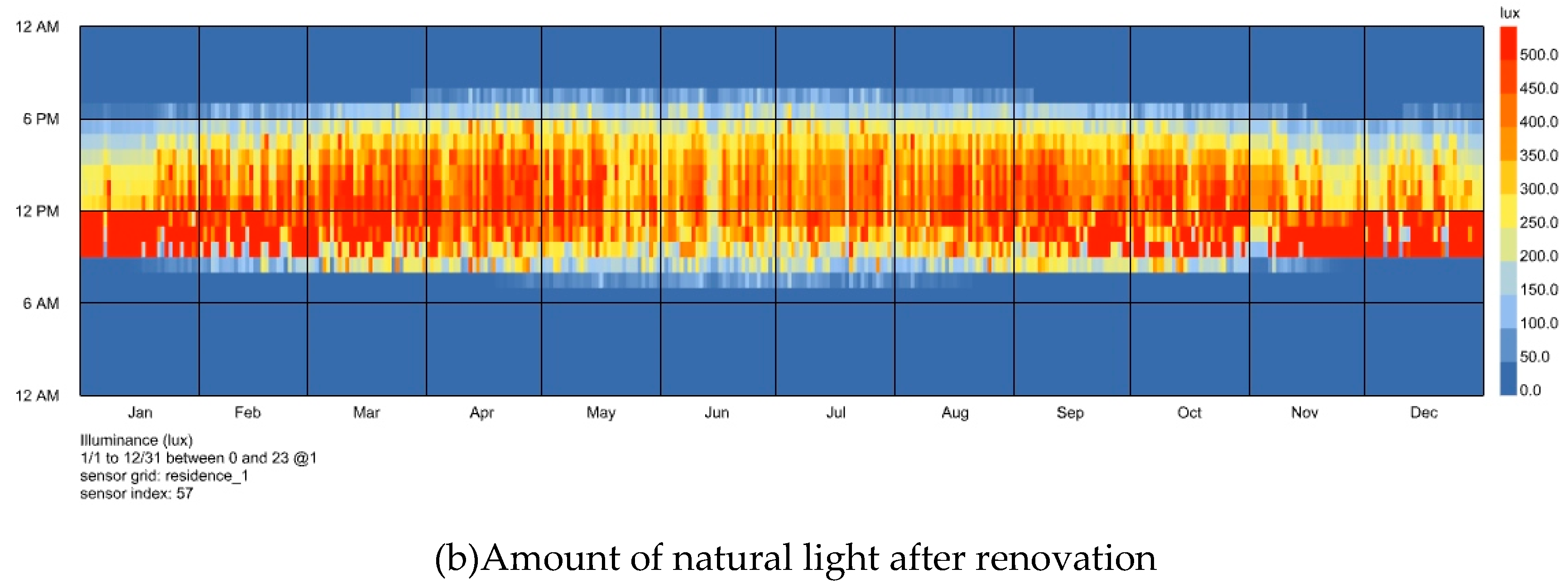

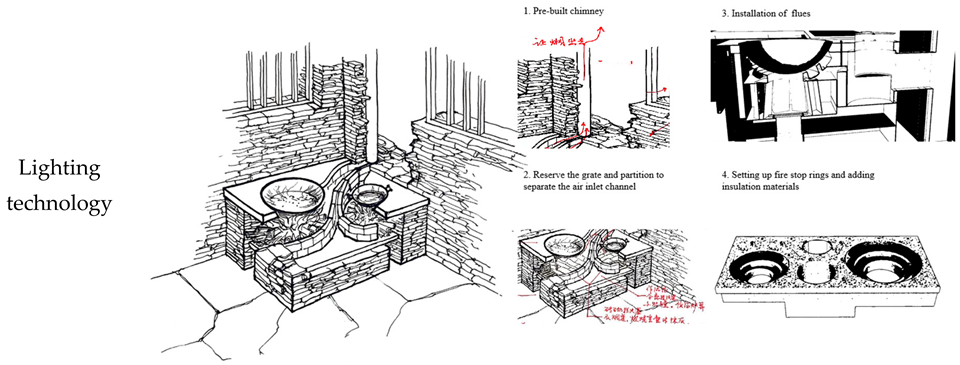

- Lighting technology:

- 4.

- Water supply and drainage technology:

- 5.

- Functional facilities:

3. Results

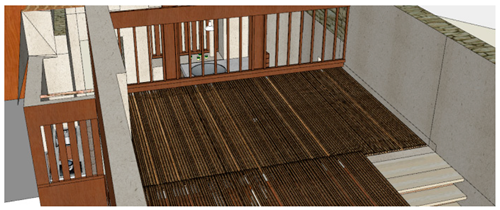

3.1. Spatial Environment Results – Improved Aesthetics

3.2. Physical Environment Results - Improved Comfort

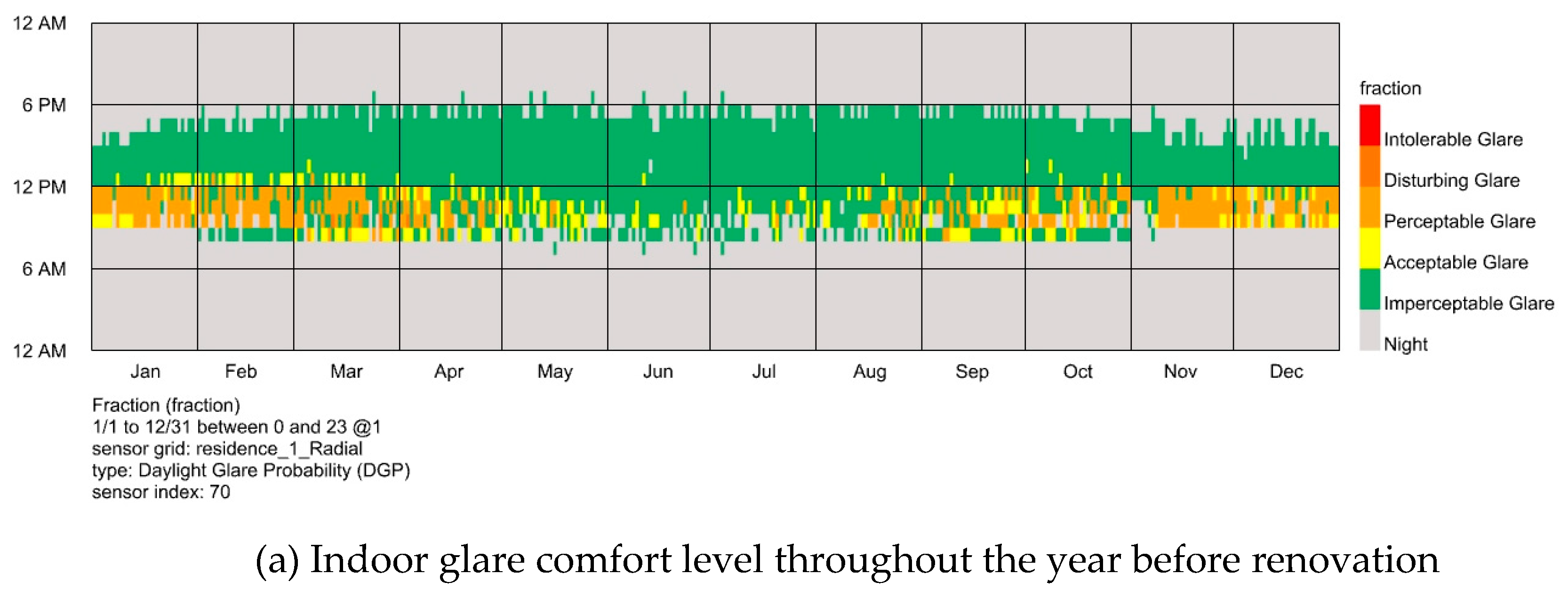

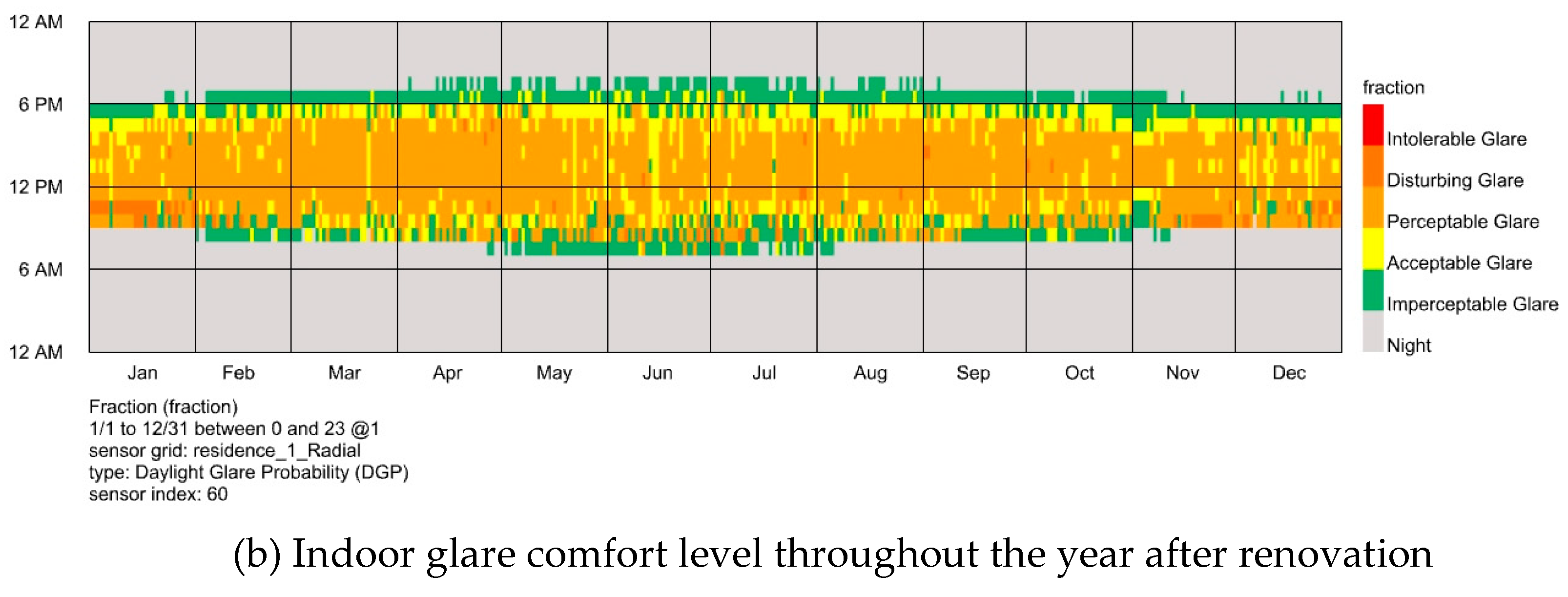

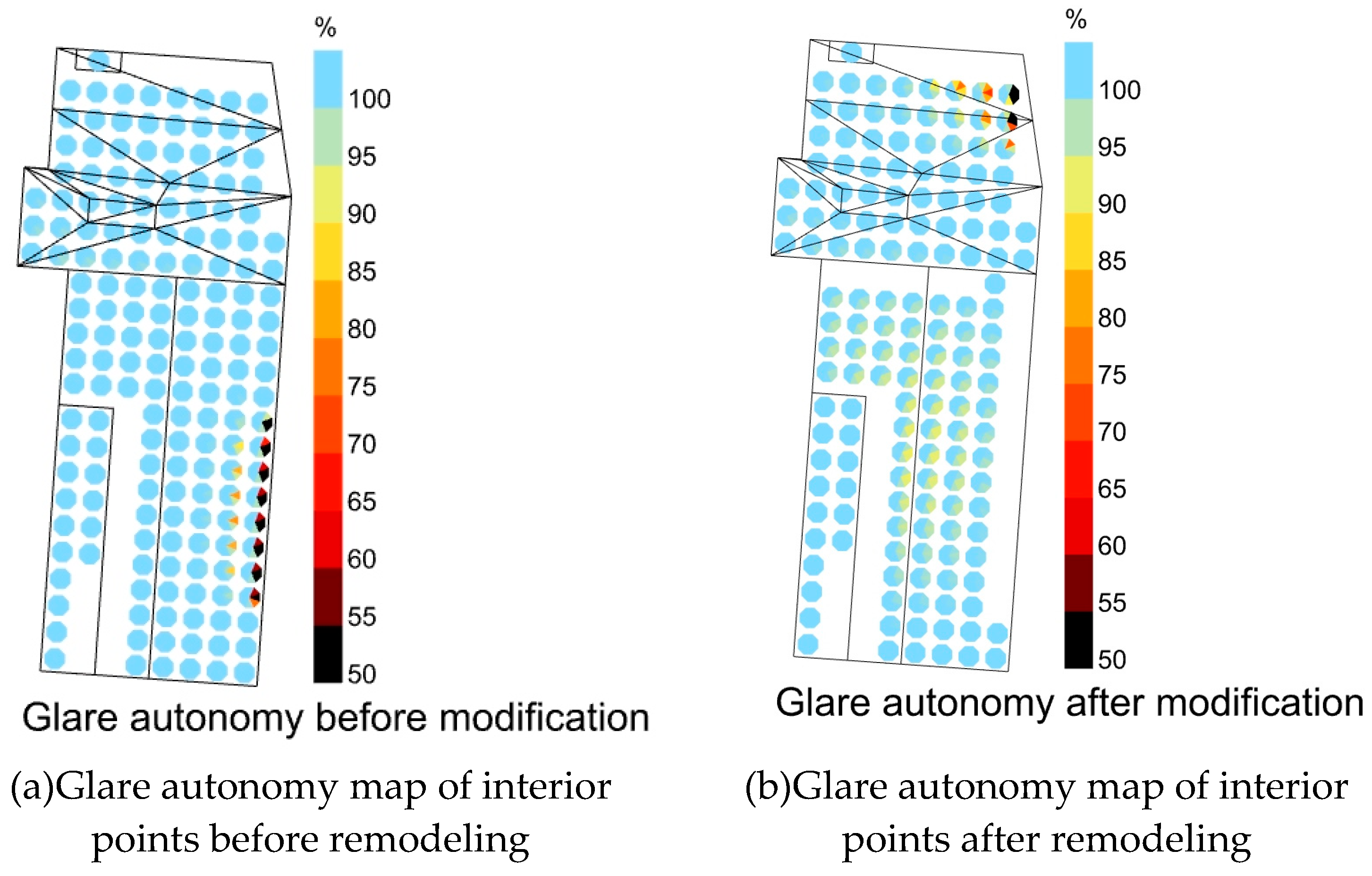

3.2.1. Light Environment Analysis:

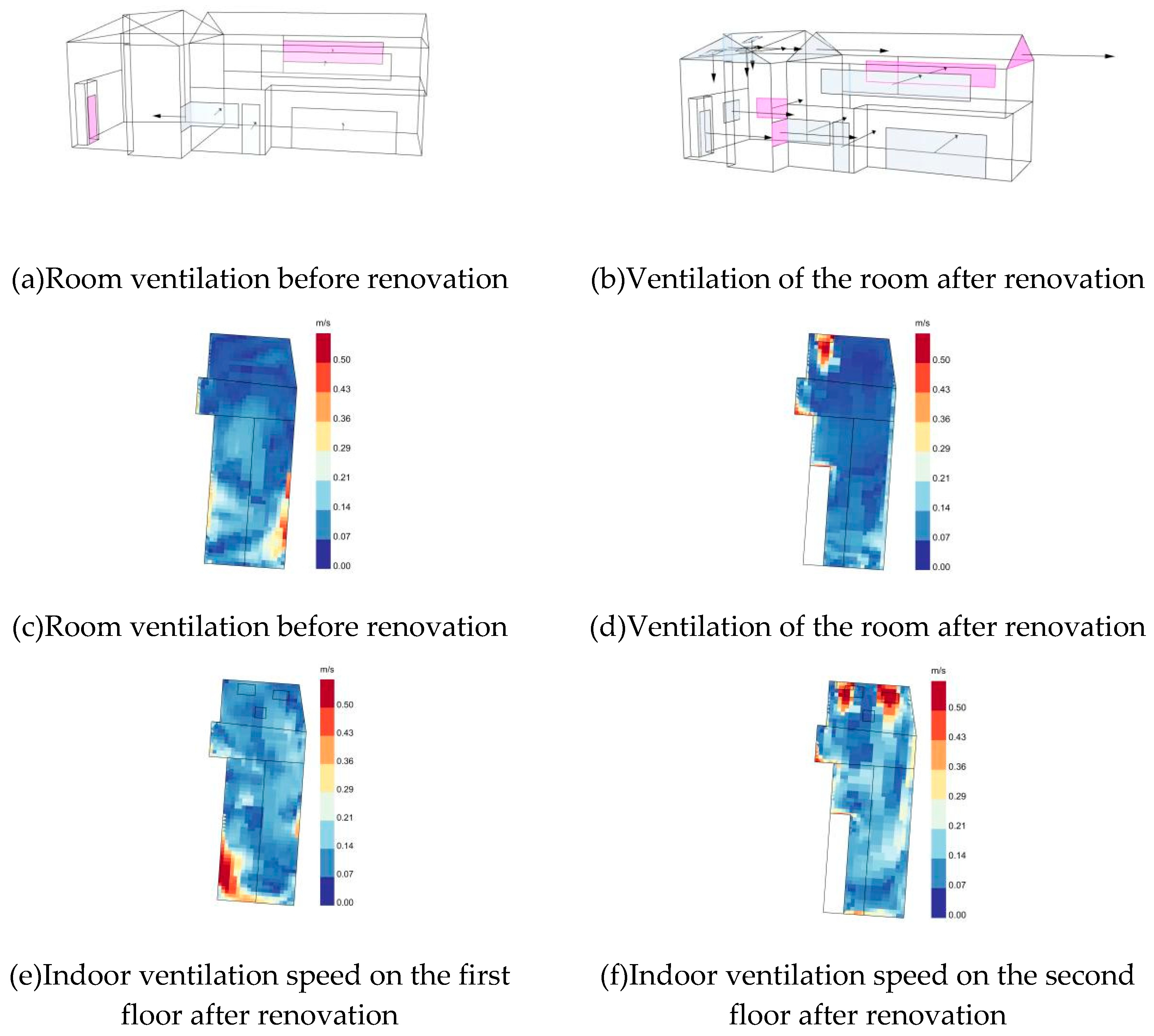

3.2.2. Wind Environment Analysis

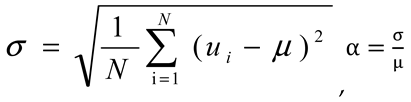

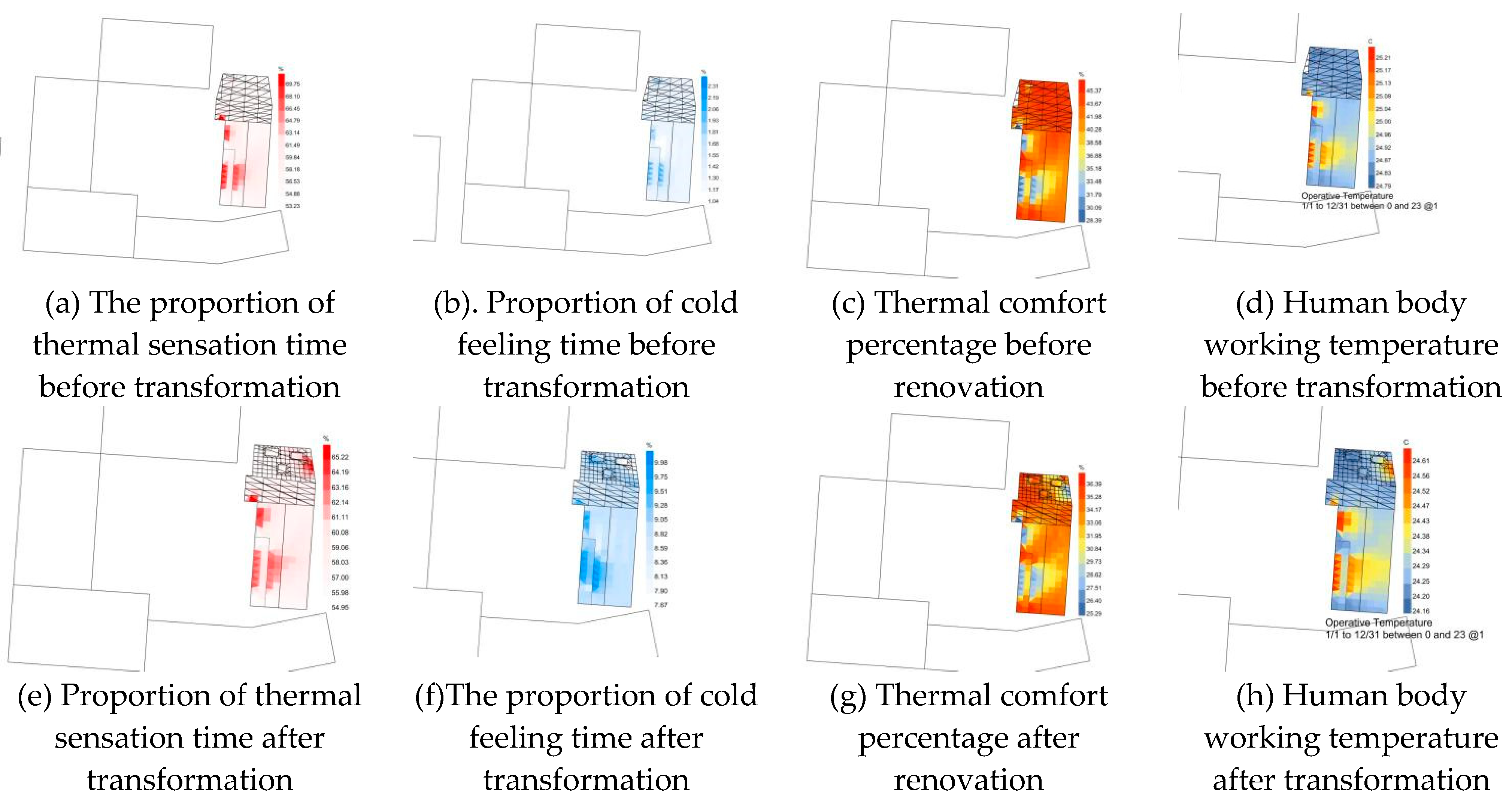

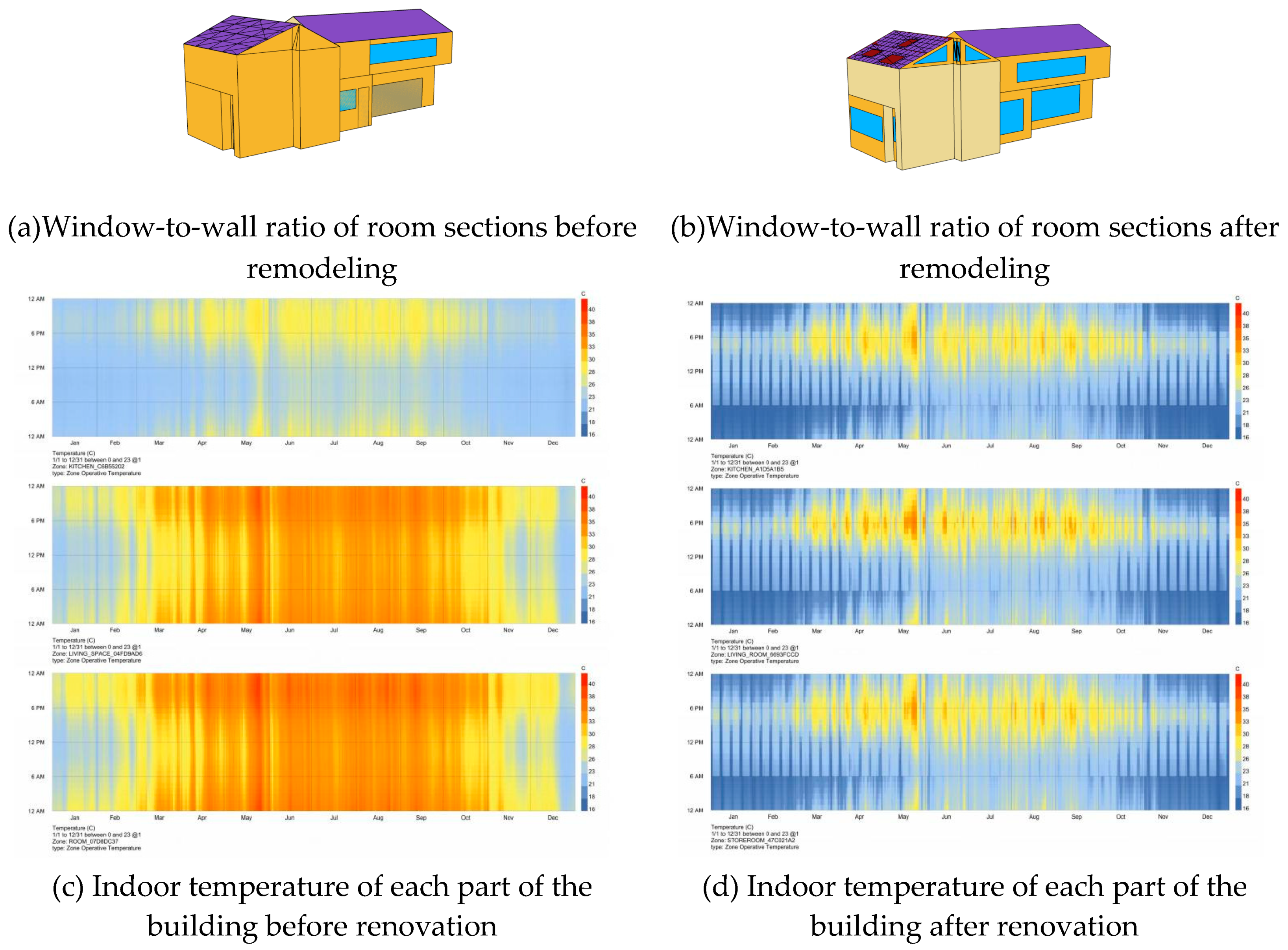

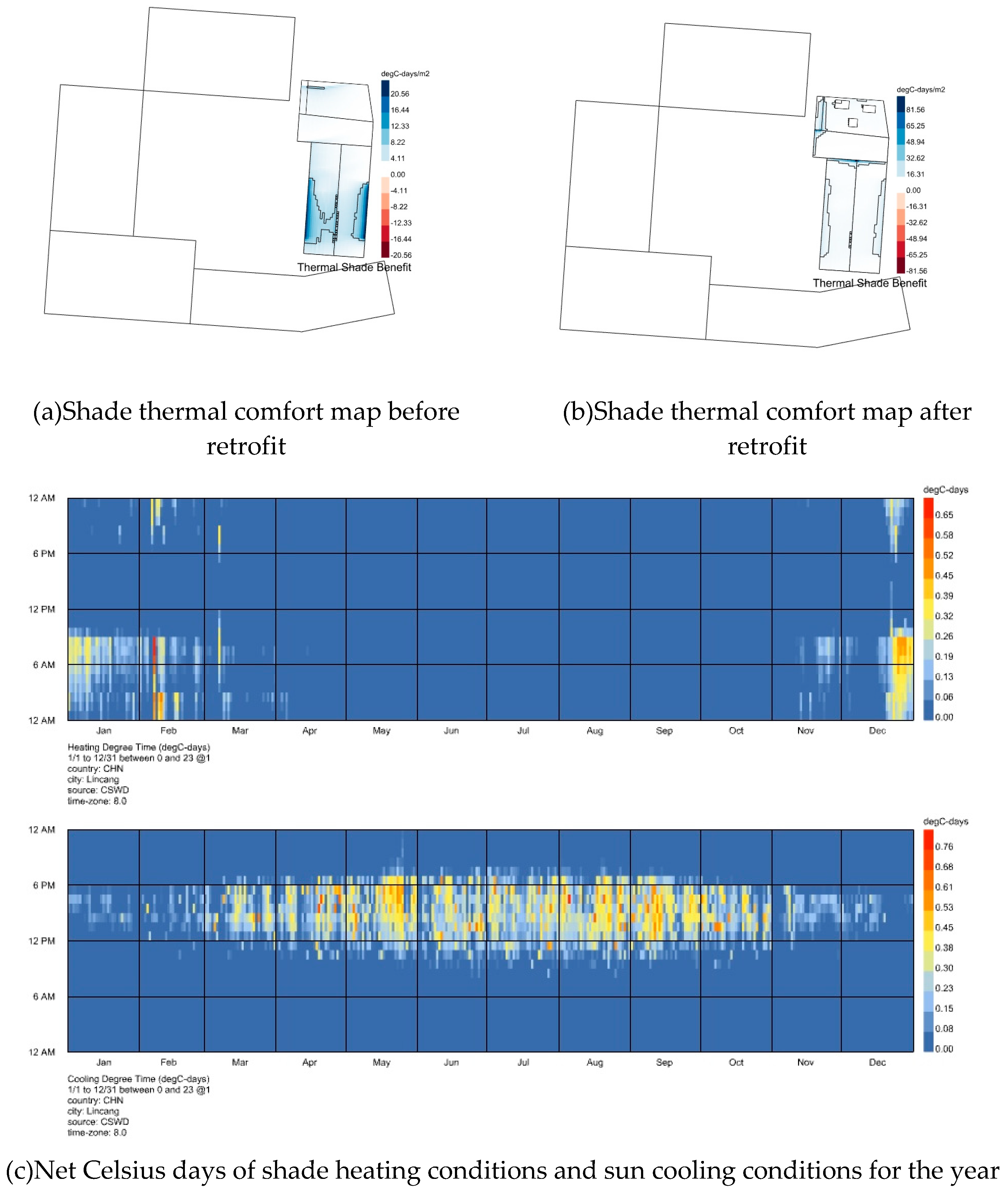

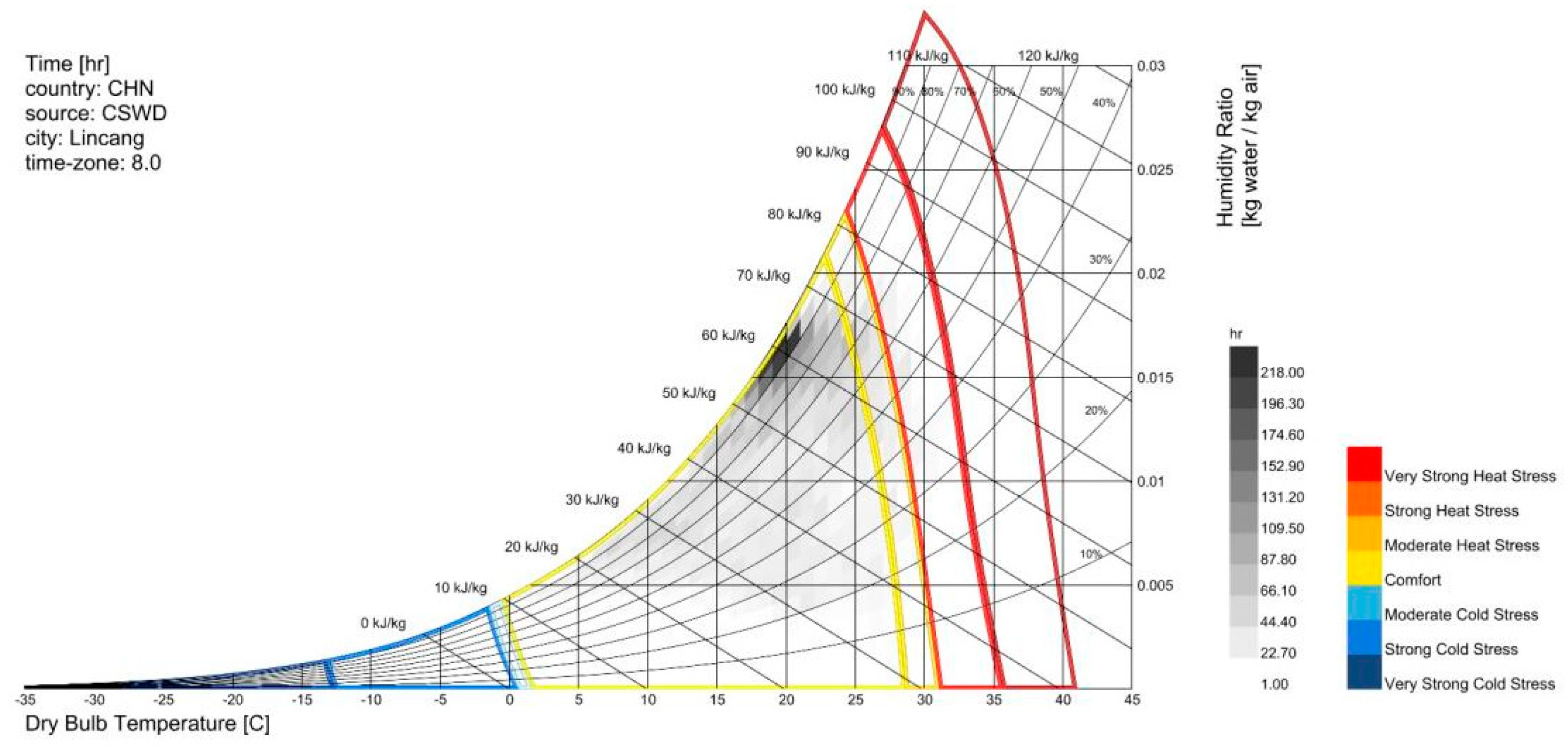

3.2.3. Thermal Environment Analysis

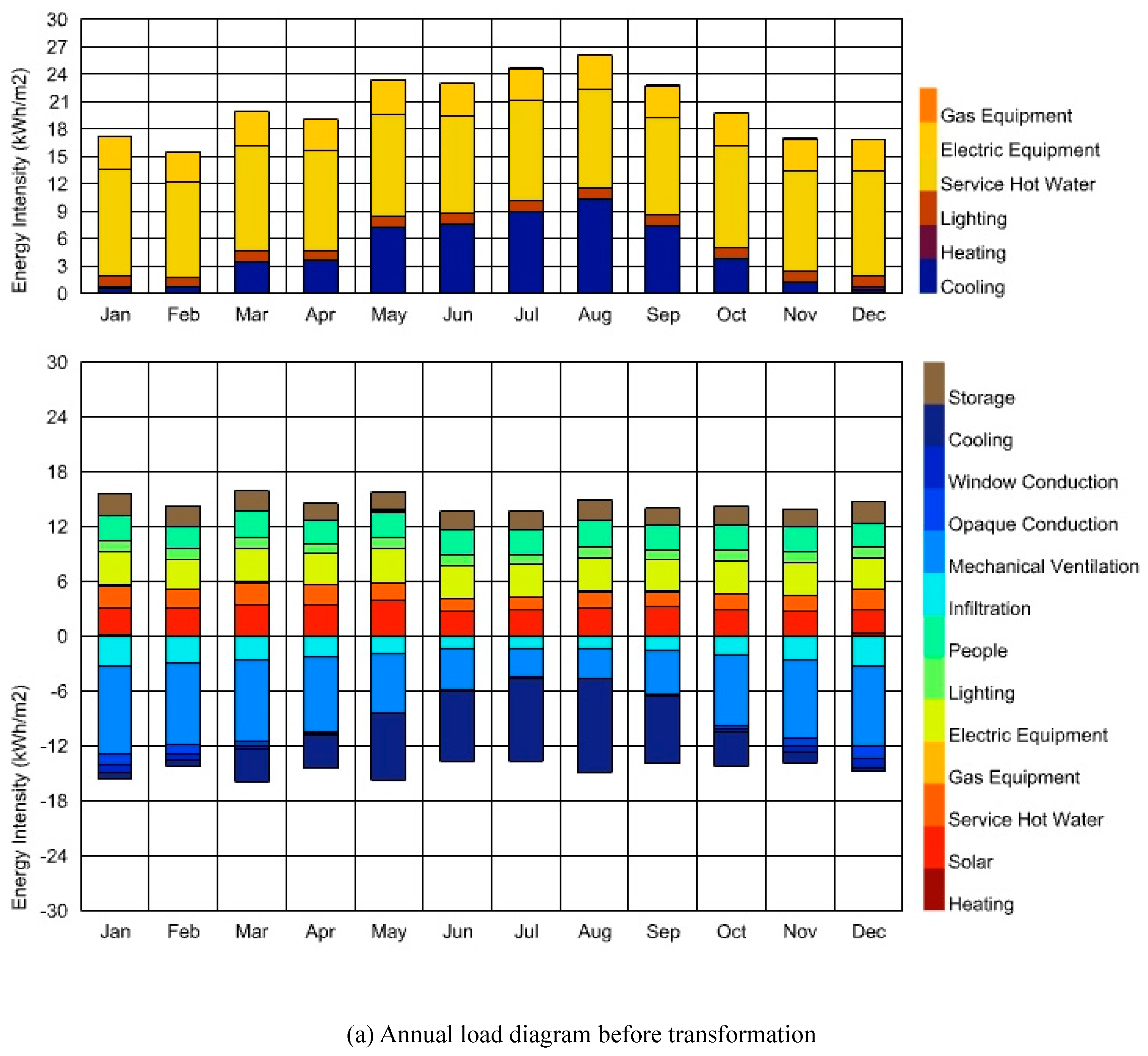

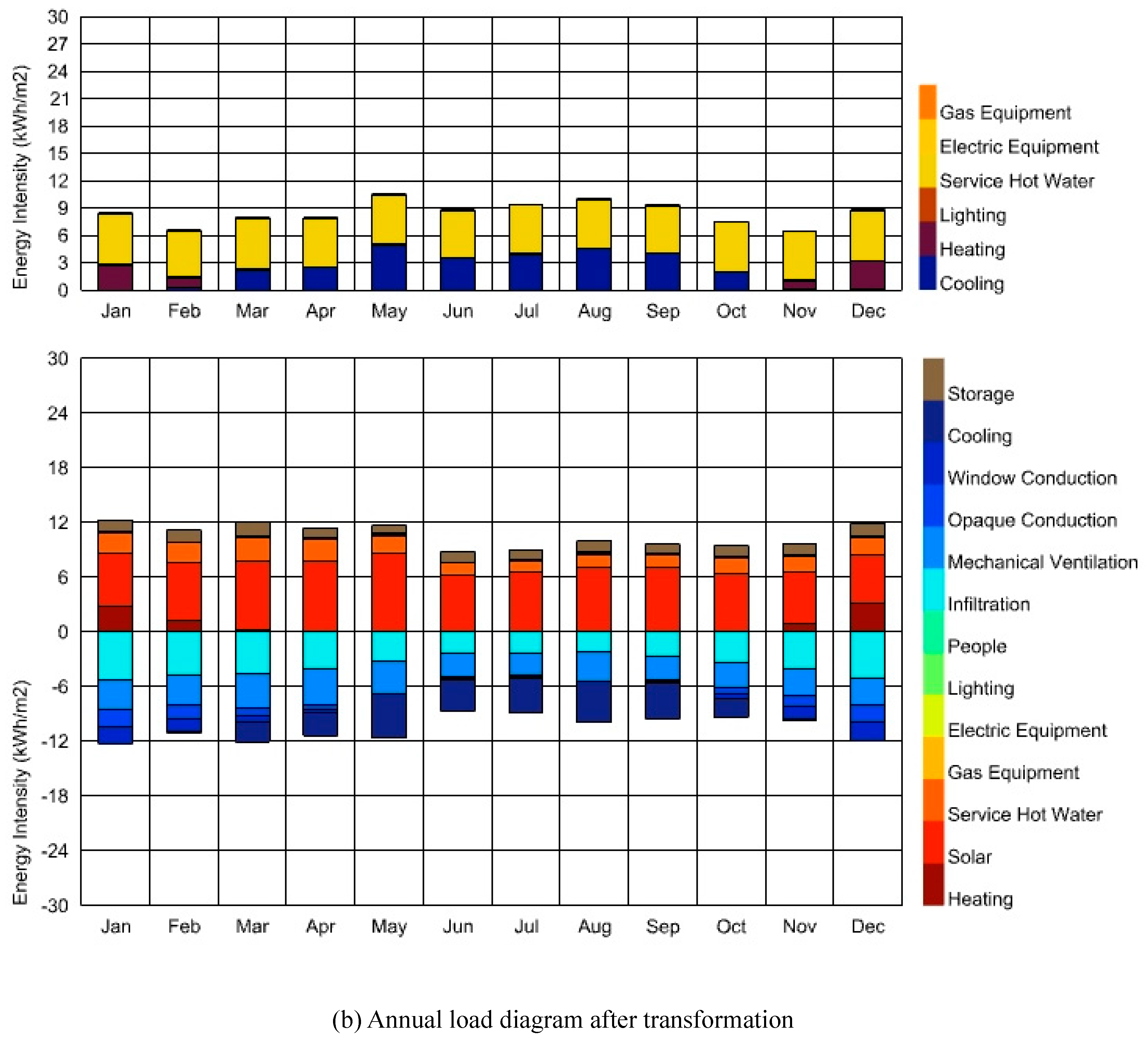

3.2.4. Building Performance Analysis:

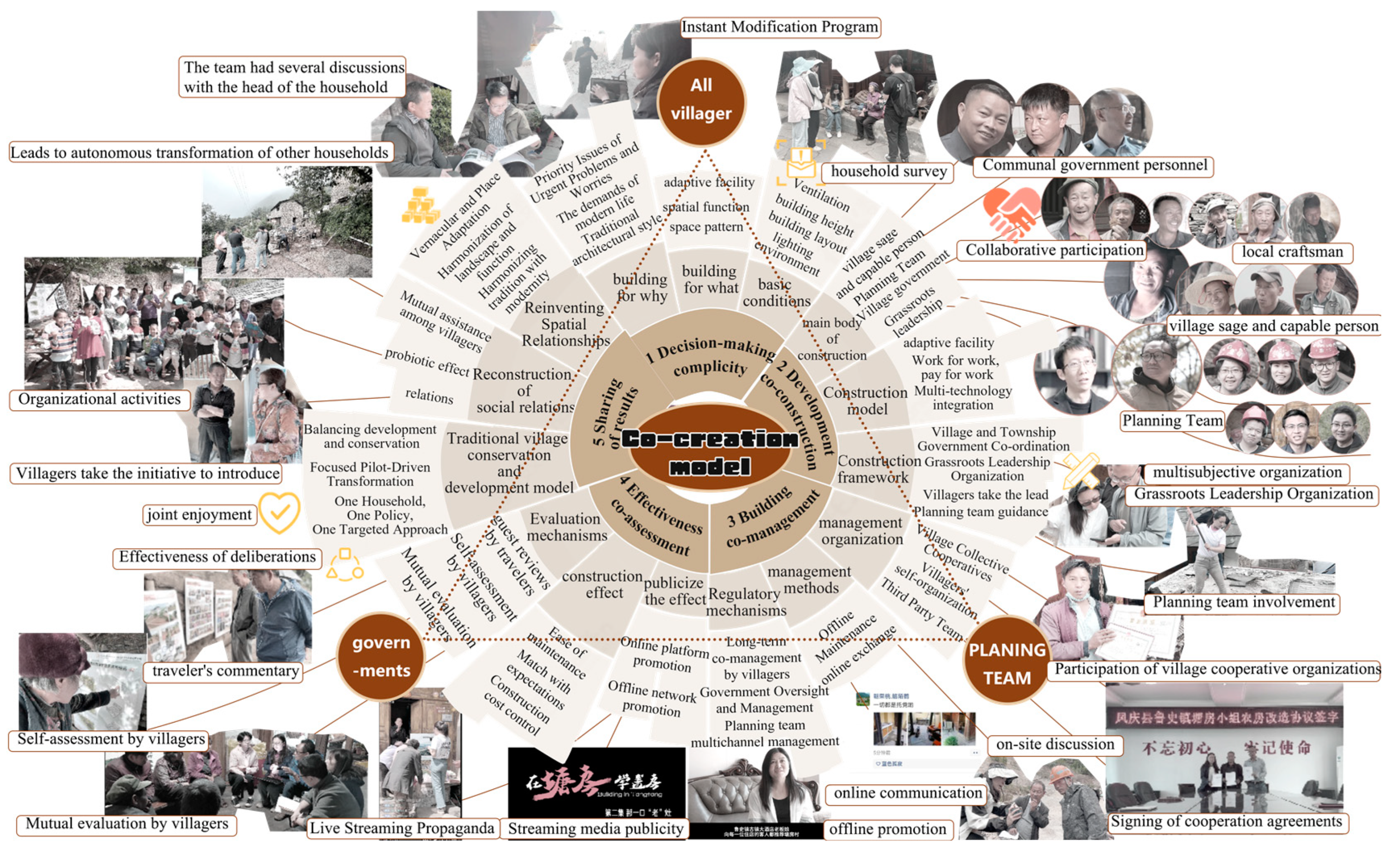

3.3. Spatial Governance Results: Increased Participation

3.3.1. Before Renovation

3.3.2. Under Renovation

3.3.3. After Transformation

4. Discussion

4.1. Low-Cost Control

| Update measures | Renovation Materials | Renovation time limit (days) | Economic cost (yuan) | Cost Structure |

| Wall structure | Straw paint, waterproof coating, cement mortar, linen stone | 2 | 3000 | |

| Smoke exhaust ventilation | Traditional stove: grate, partition, bricks, linen stone | 3 | 3870 | |

| Kitchen flue: hood, brick | 1 | 2000 | ||

| Modern stove: waterproof varnish, bamboo curtain, bricks, tiles, sand and gravel | 3 | 1400 | ||

| Lighting measures | Roof structure: tempered glass, shale slabs, | 1 | 3000 | |

| Wooden structure repair: local Yunnan pine | 1 | 1000 | Replacement of rotten beams, rafters | |

| Water supply and drainage measures | Ground reconstruction: fine stone concrete, mixed mud, putty | 2 | 550 | |

| Material and soil transportation/construction equipment use | —— | 2 | 550 | |

| Labor | —— | 15 | 24640 | Senior worker (a total of 84 people) 21,000 yuan, laborer (a total of 20 people) 2,800 yuan, including craftsman insurance of 840 yuan |

| total | 15 | 40010 |

4.2. Low Investment Mode

4.3. Low-Cost Control

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DA | Daylight autonomy |

| DF | Daylight factor |

| sDA | Spatial daylight autonomy |

| DGP | Daylight Glare Probability |

| UGR | Unified Glare Rating |

| HSP | Lists of values between 0 and 100 for the Heat Sensation Percent(Percentage of occupancy time when thermal conditions are above acceptable/comfortable temperatures.) |

| CSP | Lists of values between 0 and 100 for the Cold Sensation Percent(Percentage of occupancy time when thermal conditions are below acceptable/comfortable temperatures.) |

| TCP | Lists of values between 0 and 100 for the Thermal Comfort Percent.(Percentage of occupancy time where thermal conditions are acceptable/comfortable.) |

| Working temperature value | Operative temperature is defined as a uniform temperature of an imaginary black enclosure in which an occupant would exchange the same amount of heat by radiation plus convection as in the actual nonuniform environment |

| PMV | Predicted Mean Vote(The Predictive Mean Valuation (PMV) index is a comprehensive evaluation index that takes the basic equations of human heat balance and the psycho physiological rating of subjective thermal sensations as a starting point, and takes into account a number of factors related to the human body's sense of thermal comfort.The PMV index shows the average index of the group's vote for seven levels of thermal sensation, ranging from (+3 to -3). |

| ACH | Air changes per hour(Air changes per hour is simply the amount of times all of the air in a room is replaced with completely new air) |

| ASHRAE | The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Quantitative method |

Formula | Letter meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Calculating the Unified Glare Rating measures an individual's comfort level with lighting indoors through the Unified Glare Index. | Lb - background luminance (cd/m2); La - luminance of each luminaire in the direction of the observer (cd/m2); ω - the stereo angle (sr) formed by the luminous part of each luminaire to the observer's eye; p - position index of each individual luminaire. |

|

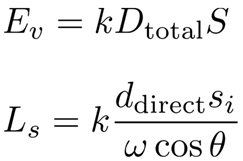

| Calculating hourly Daylight Glare Probability (DGP) for each sensor in a model's sensor grids. Glare Autonomy (GA) results in percent. GA is the percentage of occupied hours that each view is free of glare (with a DGP below the glare threshold). |

|

Ev= Vertical eye illuminance Ls= glare luminance Ws= solid angle of the glare source P = Gus position index n = number of glare sources |

| CalculatingLs: glare luminance and Ev:Vertical eye illuminance |

|

Dtotal= Vector of daylight coefficients for all sky patches S = vector of point-in-time sky luminance for all sky patches ddirect= daylight coefficients for the direct component of sky patch i only Si= point-in-time sky brightness value for sky patch i k = luminous efficiency of 179Ln/W white light |

| k Turbulent kinetic energy: characterises the kinetic energy carried per unit mass of fluid due to turbulent pulsations. Larger values indicate more violent velocity fluctuations in the flow field (e.g., separating flows, vortices, etc.); smaller values indicate that the flow tends to be more laminar (uniform velocity distribution) |  |

u′, v′, ω′: velocity pulsation component of the fluid in the ,y,z direction (deviation of the instantaneous velocity from the mean velocity) (: time averaging operator;. :Energy normalisation factor per unit mass of fluid. |

| σ means the standard deviation of the velocity field. Reflects the degree of deviation of the velocity value of each position from the average velocity; the larger σ is, the more uneven the velocity distribution (such as local high-speed or low-speed areas); the smaller σ is, the more uniform the velocity distribution. α means Uneven velocity coefficient. Usually defined as the ratio of the standard deviation of the velocity to the mean velocity, it is used to quantify the degree of dispersion of the wind velocity distribution in space. The lower the coefficient, the more uniform the airflow distribution. |

|

: The instantaneous velocity of the ith measurement point in space; : the average velocity of all measurement points in space N: total number of measurement points |

References

- Lu, J.; Su, Y.; Xu, F.; et al. Huayao kitchen:Renewal of rural residential kitchen in Chongmutai village. J. Archit. 2019, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Chen, D. Concept analysis and exploration of ideas for the cluster model of traditional rural settlement protection and development in the new era. Urban Development Research 2022, 29, 16–21+39. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Fang, X. Thinking about the auxiliary approach of landscape characteristic assessment to rural planning in the Pearl River Delta. Small Town Construction 2021, 39, 35–44+76. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, M. Protection and development of traditional villages in Tongren City under the background of rural revitalization strategy. Rural Economy and Science and Technology 2025, 36, 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; et al. Research on the construction of local human settlement environment based on cultural gene genealogy: A case study of Shaxi Ancient Town in Dali. Art and Design (Theory) 2024, 2, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Urban-rural integration and rural revitalization in the new era of China. Acta Geographica Sinica 2018, 73, 637–650. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. New rural elites and rural charity: resource integration, project docking and incentive mechanism innovation. Journal of Yunnan Nationalities University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 2020, 37, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Tong, S. Application of “Low-tech” in the Intervention of Traditional Style Buildings: A Case Study of House No. 009 in Pingshan Village, Shangyu District, Shaoxing. Urban Architecture 2024, 21, 18–23+33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, F. More than just building rural areas: the content and principles of contemporary rural construction. China Book Review 2014, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.; Huang, J.; Wang, D.; et al. Study on spatial characteristics of functional modules of rural kitchens in Hefei. Furniture and Interior Decoration 2024, 31, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; et al. Study on the actual characteristics and renewal strategies of kitchen space in rural houses: A case study of southern Anhui. Central China Architecture 2022, 40, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. Study on the architectural genealogy of wooden tile houses in northwest Yunnan based on the investigation of construction techniques. Master degree, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S. The Basic Form and Characteristics of Folk Beliefs of the Yi Ethnic Group in Southern Yunnan and Their Impact. Journal of Xichang College (Social Science Edition) 2024, 36, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, Z. Design of village and town residential space based on settlement fractal isomorphism research: A case study of Yi traditional settlements in Chuxiong area. Southern Architecture 2021, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mostaedi, A. Low-tech housing strategies, Han, L., Translator; Beijing, China, 2005; 6–7.

- Tudoran, O.A.; C Dumitrescu, C.G. Tendencies in ecological architecture. Reducing energy consumption during the projection phase. Low-tech type of ecology. Journal of environmental protection and ecology 2013, 14, 744–752. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Gong, Y. Research on the design of kitchen island for the elderly. Industrial Design 2023, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Men, Y.; Jiang, K.; Yao, j.; et al. Mitigating household air pollution exposure through kitchen renovation. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2025, 23, 100–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Ma, H. Numerical simulation of the impact of different air intake modes on the diffusion of double pollution from cooking in residential kitchens. Journal of Safety and Environment 2023, 23, 2514–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunnan Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. Civil Building Energy-saving Design Standard. Available online: https://zfcxjst.yn.gov.cn/submodule/Editor/uploadfile/20200120110553549.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Li, J. Research on facade shading system of cultural and sports buildings based on indoor natural lighting quality: Taking the Shangcun Cultural and Sports Center project as an example. Architecture and Culture 2024, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day - lighting Simulations with Radiance Using Matrix-based Methods (2019-03-09). Available online: https://www.radiance-online.org/learning/tutorials/matrix-based-methods.8 (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China"Green Building Evaluation Standard" (GB/T50378-2019). Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zc/wjk/art/2024/art_17339_779172.html (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Dang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wang, X.; et al. Exploration of new rural low-carbon building model based on prototype theory. New Architecture 2024, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. Promoting "good governance" through "participation" - Research on the impact of participatory rural planning from the perspective of governance. Urban Planning 2018, 42, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, Y. Rough regions: Regional differentiation of new brutalism and its contemporary value. Journal of Western Human Settlements 2025, 40, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Li, Y.; Dong, Yu.; et al. Exploration of progressive construction planning model for rural communities. Planner 2019, 35, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Lang, W.; Chen, T.; et al. Co-creation workshop: a new model of participatory community planning. Planner 2015, 31, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, S. Research on the governance mechanism and construction effect of rural construction: A comparison of four rural construction cases in Fenghua, Zhejiang Province. Journal of Urban Planning 2021, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. Exploration of the path of rural construction based on the linkage of “village regulations, village construction and village management”: A case study of the rural co-creation experiment in Yucun, Zhejiang Province. Urban Planning 2024, 48, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Government Website Guidelines for Farmers’ Participation in Rural Construction (Trial). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-01/17/content_5737525.htm (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- China Rural Research Network. Farmers’ Participation in Village-level Governance: On the Realization of Rural Social Governance Community. Available online: https://ccrs.ccnu.edu.cn/List/H5Details.aspx?tid=20186 (accessed on 3 December 2023).

| question | Self-transformation solution | Application Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| Functional flow problem | Extra storage is placed on the second floor, a new storage room, and on the balcony |  |

| Ventilation Problems | Use mud or plaster to seal the stove to prevent smoke leakage |  |

| Water supply and drainage issues | Use water tank to store water and connect external water pipe to drain water |  |

| Lighting issues | Replace roof or mezzanine slate with bright tiles |  |

| Technical measures | Specific approach | |

|---|---|---|

| Functional facilities |  |

|

| (a) Cabinets and shelves | ||

|

|

|

| (b) Cabinets, step cabinets | ||

|

|

|

| (c) Woven wooden frame + rattan ceiling | ||

| Ventilation technology |  |

|

| (e)Stove exhaust, modify window-to-wall ratio | ||

| Lighting technology |  |

|

| (f)Open windows to let in light, change the wall | ||

| Unified Glare Ratio (UGR) | Subjective feeling |

|---|---|

| UGR<9 | Feels black ( hard to detect glare) |

| 9≤UGR<10 | Feel more comfortable (glare is acceptable) |

| 10≤UGR<16 | Feeling acceptable and comfortable ( glare can be perceived) |

| 16≤UGR<22 | Feeling of discomfort (distracting glare) |

| 22≤UGR<28 | Feeling very uncomfortable (can't stand the glare) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).