Introduction

Fall Armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda, is a lepidopteran pest that attacks more than 350 plant species in vast numbers, causing significant yield losses if left uncontrolled on cotton, other vegetable crops, and maize, as well as economically substantial farmed grasses including sorghum, rice, sugarcane, and wheat (Nwanze et al., 2021). FAW is an invasive pest that originates in America and has spread in Africa in 2018, India (2018-2019) and eventually expanded to Asia-Pacific countries including China, Korea, Japan, Australia, and Southeast Asian countries (Navasero, et al., 2020; Yang, et al., 2021a; Kumar, et al., 2022). This agricultural pest is highly polyphagous and mostly feeds on foliage consuming the leaf tissue from one side and leaving the opposite epidermal layer intact (Capinera, 2020).

Significant corn yield losses were reported in different countries that were affected by FAW (Omwoyo, et al., 2022; Kumar, et al., 2022). In Africa, it has the potential to cause corn losses from 8.3 to 20.6 million tons each year if left uncontrolled (Day, et al., 2017). Generally, to control FAW, farmers are using resistant cultivars, insecticides, cultural practices, and integrated pest management approaches (Matova, et al., 2020). However, there are limitations to the success of any of these strategies in providing efficient control in large-scale fields due to high pest pressure (Li, Wang, & Romeis, 2021). Currently, using synthetic insecticides remains to be the primary control of this agricultural pest. Commonly, emamectin benzoate, Bacillus thuringiensis, lambda cyhalothrin, indoxacarb, chlorpyrifos and chlorantraniliprole are used to control FAW (USAid, 2018; Phambala, et al., 2020; Hasnain, et al., 2023). In consequence, the long-term use of these synthetic insecticides could lead to resistant strains (Hafeez, et al., 2022).

Sustainable pest management is continually challenged with insect resistance to synthetic insecticides (Hafeez, et al., 2022). Developing pesticide resistance management techniques requires a thorough understanding of the mechanisms through which insects acquire resistance to insecticides. Mechanisms of insecticide resistance include behavioral, biological, penetration, target-site alteration, metabolic, and resistance-inducing operational factors (Siddiqui et al., 2023). The most common type of insecticide metabolic resistance is monooxygenase-mediated resistance (Scott, 1999). Particularly, Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP450) are implicated in the metabolism of a broad spectrum of insecticides, facilitating their breakdown or modification into less toxic forms (Ye et al., 2022) through a catalytic cycle involving substrate binding, electron transfer, oxygen activation, oxidation reactions, and product release (Guengerich, 2018). This results in reduced susceptibility of pests to insecticides, necessitating the development of alternative strategies for effective pest control (Siddiqui et al., 2023).

Several studies show that CYP450 genes are highly involved in resistance developments in FAW to various insecticides (Berge et al., 1998). Hafeez et al., (2019) revealed that CY3217A7 and CYP6AE43 were significantly higher mRNA transcript levels in the midgut of FAW population exposed to indoxacarb compared to the unexposed population. Bai-Zhong et al. (2020) also discussed that CYP321A8, CYP321A9, and CYP321B1 were overexpressed in the midgut of second instar FAW larvae after being exposed to chlorantraniliprole. Actin was also observed to have stable expression after being exposed to an insecticide, emamectin benzoate (Zhou et al., 2021).

Repeated use of chemicals would increase the risk of insect resistance to chemicals. Thus, the demand for innovative approaches in controlling pests is highly encouraged. Using RNA interference (RNAi) would open new avenues for FAW management. Double-stranded RNAi is used to silence gene expression of an organism triggered by a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) at a cellular level (Agrawal, et al., 2003; Hafeez, et al., 2022). It is a conserved regulatory method known that is used to modulate gene expression in a controlled manner while inducing sequence-specific gene silence (Yao, et al., 2022). One remarkable aspect of RNAi is that the dsRNA can spread to different body parts in addition to penetrating the gut cells, leading to systemic RNAi in these highly susceptible insects. (Joga, et al., 2016). With this, scientists have used this technology to reduce the insect’s susceptibility to insecticides by targeting the CYP450 genes. Laboratory studies have shown successful silencing of target CYP450 genes to increase the insect’s susceptibility to various insecticides (Hafeez et al., 2022; Nitnavare et al., 2021; Saberi et al., 2024; Y. Zhang et al., 2019). In fact, the first sprayable biopesticide product based on dsRNA which is GreenLight’s Calantha with an active ingredient of Ledprona was developed to combat the Colorado Potato Beetle (Rodrigues et al., 2021) and had already been granted a registration from the US EPA (ID: EPA-HQ-OPP-2021-0271-0194).

This study’s main objective is to develop and evaluate the efficacy of dsRNA for RNA interference (RNAi) to knockdown cytochrome P450 expression in Fall Armyworm, with the aim of contributing a sustainable solution for pest management. Specifically, analyze the mortality and phenotypic effects of knockdown of essential genes of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8.

Materials and Methods

Insect Collection and Rearing

S. frugiperda larvae were collected from Isabela, Philippines through the Institute of Plant Breeding, UPLB. The collected insect samples were reared in the laboratory at room temperature conditions with a photoperiod of 12 hours of light and dark photoperiod at 25oC room temperature. First-generation FAW was used in the experiments. Following a 24-hour feeding period with insecticide-treated leaf discs, FAW larvae were subjected to total RNA extraction for expression analysis and gDNA extraction for amplification of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8. Four treatments were laid out for expression analysis, T1: those unexposed to insecticide treatment denoted as Control, T2: those exposed to Chlorantraniliprole denoted as CTPR, T3: those exposed to Thiamethoxam denoted as THMX, and T4: those exposed to an insecticide with dual active ingredients of Chlorantraniliprole and Thiamethoxam denoted as CTPR + THMX.

Chemicals

The insecticides used have an active ingredient of Chlorantraniliprole 5% SC, Thiamethoxam 25% WG, and a dual active ingredient of Chlorantraniliprole 20% and Thiamethoxam 20% WG. Corn plants were sprayed with CTPR, THMX, and CTPR + THMX at 30 mL/16 L water, 4 g/16 L water, and 15 g/ 16 L water, respectively.

Primer Design

The selected

Actin,

CYP321A7 and

CYP321A8 of

Spodoptera frugiperda, as shown in

Table 1, were obtained online from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The primer sequences were designed using primer-blast from NCBI and dsRNA primers from SnapDragon (

https://www.flyrnai.org/snapdragon) to obtain the forward and reverse sequences at 5’-3’. RNAi can be hindered by off-target effects, where the dsRNA molecule interacts with unintended genes with sequence similarity to the target. To mitigate this issue, platforms like SnapDragon implement a stringent base-pair identity threshold for the amplified region, minimizing the potential for off-target interactions (Kulkarni et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2006). The mGFP sequence was obtained from pCAMBIA 1302 plasmid vector. The PCR product and primers were from Dr. Karen B. Alviar.

Relative Expression Analysis of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 in Spodoptera frugiperda

Extraction of RNA and Preparation of cDNA

Total RNA was extracted from 3rd instar FAW larva exposed to CTPR, THMX and CTPR + THMX insecticides. FAW larvae which were unexposed to insecticides were also isolated to act as control. The extraction was done using the GF-1 Total RNA Extraction Kit (Vivantis, Shah Alam, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA was extracted individually from ten insects per insecticide treatment and five insects for negative control. cDNA was subsequently synthesized from these RNA samples for the expression of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 through sqRT-PCR using a thermal cycler (SimpliAmp, Applied Biosystem, Waltham, MA USA). Following the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) protocol, the first-strand cDNA synthesis was prepared from 1 μg of total RNA. All synthesized cDNAs were stored at -20oC until use.

Expression of CYP321A7 & CYP321A8 Genes in CTPR, THMX and CTPR+THMX exposed larvae

The synthesized cDNAs were used as templates for two-step semi-quantitative RT-PCR with specific primers specific for

CYP321A7 and

CYP321A8 to determine their relative expression compared to

Actin. The PCR mixture was prepared by putting either

CYP321A7 or

CYP321A8 forward and reverse primers, GoTaq G2 (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) colorless master mix. The cDNA template of 3 µL [150 ng] was used for the expression of

CYP321A7,

CYP321A8, and

Actin. Actin was used as a reference gene for this study as this gene was proven to show significant stability expression in FAW after insecticide treatment (Zhou et al., 2021). The PCR mixture, with a total of 10 µL volume, was run on a thermal cycler following the synthesized primers’ protocol. The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis at 50 V for 45 minutes, operating on an agarose gel with a concentration of 1.5%. The gels were stained with GelRed in 1X TAE buffer for 20 minutes and were destained for 10 minutes, followed by the digital capturing process through the BioBase gel documentation system (BIOBASE, Shandong, China). The Gel Pro Analyzer was utilized to conduct the quantitative analysis, while the band intensity was measured in relative absorbance units. The evaluation of the expression of

CYP450 in FAW was compared to the evaluation of the expression of Actin in the same insect sample. Mathematically speaking:

This correction was done to normalize the possible variation in the sample concentration, as well as a control for reaction efficiency. It is important to note that some readings of Actin from the gel documentation system returned a value of 0, thereby resulting in errors. To rectify this situation, the reference formula from the literature cited was modified into Equation 1, such that the reference gene in the denominator was subtracted to 1. The corrected expression of Actin was also modified to be expressed in terms of percentage for easier interpretation and visualization of values.

Amplification and Sequence Alignment Analysis of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 in Spodoptera frugiperda

Amplification of CYP321A7 and CYP3218

The eluted gDNAs were used to amplify CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 using a two-step semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The PCR mixture was prepared by putting up either CYP321A7 or CYP321A8 forward and reverse primers, GoTaq G2 (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) colorless master mix. The resulting mix was combined with 3 µL of eluted gDNA. The PCR mixture was amplified using a thermal cycler following the synthesized primers’ protocol. The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis at 50 V for 45 minutes, operating on an agarose gel with a concentration of 1.5%. The gels were stained with 1X GelRed (Biotium, CA, USA) in distilled water for 30 minutes and were destained for 10 minutes, followed by the digital capturing process through the BioBase gel documentation system (BIOBASE, Shandong, China).

Sequencing of the Purified PCR Products

The purified PCR products of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 from gDNA of extracted FAW-CTPR exposed were upscaled to a final volume of 100 µL for sequencing analysis. The PCR mixture was prepared by putting up either CYP321A7 or CYP321A8 nuclease free-waster, forward and reverse primers, and GoTaq G2 colorless master mix. The resulting mix was combined with 3 µL gDNA template. The 3 µL of PCR products were checked on gel electrophoresis at 50 V for 45 minutes, operating on an agarose gel with a concentration of 1.5%. The same process was done for staining, destaining and image capturing of the gel as mentioned previously.

The remaining PCR products were run on gel electrophoresis following the same procedures as mentioned previously. The gel with amplicons has undergone purification using a Gel and PCR Clean-up System Kit (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA). For elution, 50 µL of nuclease-free water was used. The purified PCR products were stored at -20oC until use.

The 25 µL purified PCR products were submitted to Macrogen (Seoul, Republic of Korea) and were analyzed for bi-directional sequencing using Capillary Electrophoresis (Sanger) Sequencing to verify the integrity of the sequence. The result sequences were then analyzed in BioEdit (version 7.7.1, Tom Hall) software to perform multiple sequence alignments and generate consensus sequences. The contigs were analyzed by BLAST in NCBI to determine the query coverage, E-value, and percent identification. The contigs were submitted to NCBI through their submission portal (

https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

dsRNA Preparation

Synthesizing dsRNA

The primers for the target sequences, CYP321A7, CYP321A8, and GFP, were designed using an extended T7 polymerase promoter sequence at the 5’ ends of each strand. To amplify the target genes with extended T7 promoters, PCR mix was prepared by putting together the forward and reverse primers, nuclease-free water, and G2 GoTaq Colorless master mix to a final volume of 10 µL. The resulting mix was combined with 3 µL of purified PCR products of the amplified primers as a template. The PCR mixture was amplified using a thermal cycler following the synthesized primers’ protocol. The PCR product of CYP321A7 was diluted at 10x in nuclease-free water while CYP321A8 was used as is.

The primers with an extended T7 promoter sequence were subjected to an initial 5 cycles at an annealing temperature 5°C higher than the melting temperature of the gene-specific sequences. This was followed by 30 cycles of annealing at 5°C higher than the melting temperature of the entire primer, including the extended T7 promoter. The T7 PCR product templates were stored at -20°C until use. The T7 PCR product templates had also undergone sequencing analysis following the same procedures as mentioned previously.

For dsRNA preparation, the purified PCR-generated templates from T7_CYP321A7, T7_CYP321A8, and T7_GFP were used DNA templates using T7 RiboMAX™ Express RNAi System Kit (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA). The RiboMAX Express T7 2x Buffer, DNA template, Enzyme Mix, and T7 Express were mixed to obtain a final volume of 20 µL. The manufacturer’s protocol was then followed.

The concentration of the T7 PCR product template and dsRNA samples were determined using UV spectrophotometry using BioDrop 125 cuvette (0.125mm pathlength) (Harvard Bioscience, Holliston, MA, USA) at 260/280 nm ratio absorbance. For dsRNA, it was diluted at 1:100 and was calculated using A260 absorbance to determine its concentration. The A

260 value was divided by the pathlength used for the UV microvolume spectrophotometry then, multiplied with 1 unit of A260 nm multiplied to the dilution factor following multiplication to the total reaction after in vitro RNA transcription. Mathematically speaking;

Equation (2). Calculation of dsRNA concentration using A260 nm absorbance.

The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis at 100 V for 25 minutes, operating on an agarose gel with a concentration of 1.5%. The gels were stained with 1X GelRed (Biotium, CA, USA) in distilled water for 30 minutes and were destained for 10 minutes, followed by the digital capturing process through the BioBase gel documentation system (BIOBASE, Shandong, China).

Feeding Bioassay

Artificial Diet

The artificial diet solid mixture formulated was obtained at the Institute of Plant Breeding, UPLB. The components of the solid mixture diet were ground corn, ground soybean, brewer’s yeast, wheat germ, ascorbic acid, vitamin E, multivitamins, methylparaben, casein, choline chloride, sorbic acid and agar-agar.

The solid mixture was added to 350 mL of boiling distilled water and cooked for 10 minutes. While agar-agar was dissolved separately in 350 mL of boiling distilled water. Afterward, it was mixed in a blender (Osterizer 4172, Oster, Philippines) to homogenize and grind further the solid components to bring a smooth texture of the diet.

LC50 of the Insecticide with Dual Active Ingredients of Chlorantraniliprole and Thiamethoxam

The lethal concentration of the selected insecticide was conducted before dsRNA feeding experiment to determine the concentration of the insecticide at 50% mortality. The insecticide used for this experiment was determined from the highest relative expression levels result. The 2nd instar FAW larvae (n=20) were exposed to the insecticide with concentrations of 36, 12, 4, 1.333, 0.444, 0.148, and 0.0493 ppm. The ppm was calculated using a serial dilution sheet, a software developed by a private agrochemical company. The feeding bioassay experiment was done in a 25oC room at 12-hour light and dark photoperiod.

dsRNA Feeding

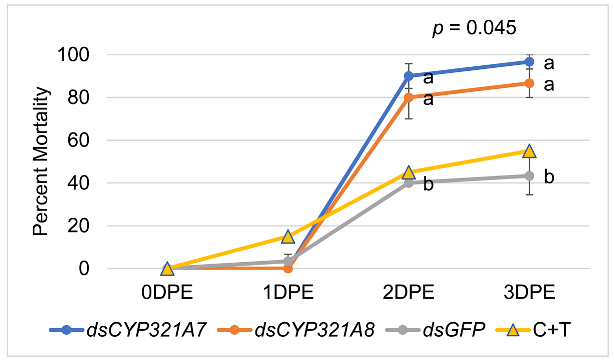

The larvae were given 1 µL [14 µg] of dsRNA solution. The artificial diet (0.7cm x 0.7cm x 0.7cm) was placed inside the hinged cups (23cm in height and 35cm in diameter) with holes in the cap. A moist tissue paper was also placed to keep the humidity inside the cup not so dry. A single drop of dsRNA solution of 1 µL was placed in the diet using a 2 µL pipette (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 24 hours followed by exposure to an artificial diet supplemented with LC50 of CTPR + THMX insecticide after 48 hours. The artificial diet without insecticide was also used as a control. Each treatment consisted of a total of 45 24-hr starved larvae, 3 replicates of 15 larvae each. The dsRNA-fed larvae mortality data were recorded at 24, 48, and 72 hours. The moribund status of larvae was used to assess the mortality rate. To evaluate the efficacy of RNAi-mediated knockdown of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8, 3 larvae from each triplicate per treatment were collected at 24 hours post-exposure to insecticides.

Statistical Analysis

The lethal concentration from the mortality of bioassay data were estimated using Finney’s probit analysis spreadsheet calculator (Version 2021). The data for mortality was analyzed using IBM SPSS version 26. A test of significant difference was performed to compare the percent mortality rate of larvae treated with different insecticides. To identify the most appropriate statistical tests, assumptions such as normality and variance homogeneity were assessed. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to check the normality of the data, while Levene’s test was used to determine variance homogeneity. Since the data does not satisfy these assumptions, Kruskal-Wallis H-test and Dunn’s Test (post-hoc) were performed. Statistical tests were performed at a 5% level of significance.

Results

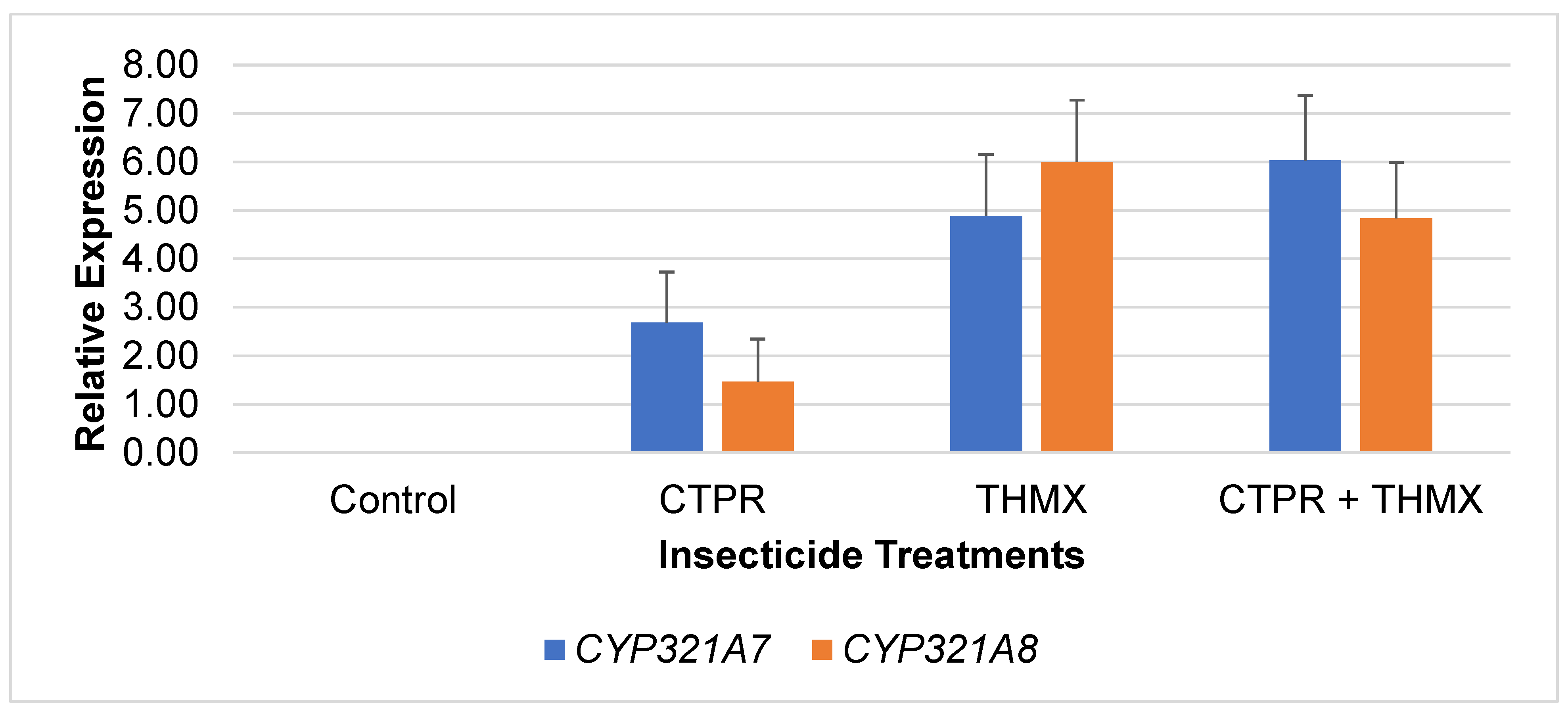

Relative Expression of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 of FAW after Exposure to Insecticides

Expression patterns of

CYP321A7 and

CYP321A8 from FAW larvae exposed to CTPR, THMX and CTPR + THMX were analyzed by sqrRT-PCR.

Figure 1 shows the relative expression levels of

CYP321A7 and

CYP321A8 in response to different insecticide treatments. In CTPR-exposed larvae,

CYP321A7 shows a relatively high expression level of 2.69 compared to

CYP321A8 at 1.46. However, both

CYP450s had relatively low expression levels compared to other THMX and CTPR+THMX. For larvae after exposure to THMX,

CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 show an increase in expression as compared to CTPR –

CYP321A7 had 4.90 while

CYP321A8 had 6.03 expression levels. The CTPR+THMX insecticide treatments lead to the highest expression of both genes with 6.90 and 6.02, respectively. Furthermore, it revealed that

CYP321A7 and

CYP321A8 can only be overexpressed when induced with insecticides. In contrast to the relatively low expression of both CYP genes observed following CTPR exposure, the combined treatment of CTPR + THMX resulted in increased expression levels.

This observation indicates a potential synergistic effect of the two insecticides in the detoxification mechanism of the CYP450 genes. This might suggest that the combination of these chemicals triggers a stronger response in FAW possibly as a mechanism to cope with increased toxicity. However, importantly, upregulation of CYP450 cannot be the sole reference to confer that the insect has gained resistance to a particular insecticide. The upregulation of CYP450s only indicates the insect’s enhanced metabolic potential to detoxify the insecticide (Yang et al., 2021).

Sequence Alignment Analysis of CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 in S. frugiperda

Following successful PCR amplification of

CYP321A7 and

CYP321A8, the PCR products were purified and were subjected to Sanger sequencing for subsequent sequence analysis. As shown in

Table 2, the analysis revealed 100% query coverage, an E-value of 0, and 100% identity between the FAW

CYP321A7 gene (PP693211.1) and the reference sequence (MZ945565.1) from Chen et al. (2022). Homologous genes from

S. litura (MF802804.1; Wang et al., 2017),

S. littoralis (LR82540.2; King, 2020), and

S. exigua (KX443442.1; Hu et al., 2019) showed progressively lower percent identities (87.88%, 86.37%, 83.49%, respectively) compared to

S. frugiperda, indicating increasing evolutionary divergence. The

Agrochola lychnidis (OY798656.1; WSTLP, 2023) exhibited the lowest similarity (query cover 89% and identity 77.69%).

On the other hand,

Table 3 shows the comparison of the

CYP321A8 gene from

Spodoptera frugiperda (accession number PP693211.1) with its homologs identified in other organisms. The

S. frugiperda (accession number MZ945600.1; Chen et al., 2022) serves as the reference exhibited a complete query cover, E-value of 0, and 100% identity. Homologous genes from

S. littoralis (LR82540.2; King, 2020),

S. litura (XM_022969704.1; Anonymous), and

S. exigua (LR824610.2; King, 2020) showed progressively lower percent identities (90.60%, 89.66%, 86.98%, respectively) compared to

S. frugiperda, indicating increasing evolutionary divergence. The

Agrochola lychnidis (OY798656.1; WSTLP, 2023) exhibited the lowest similarity (query cover 95% and identity 77.79%).

Overall, sequence analysis revealed 100% identity between the obtained CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 sequences and their corresponding reference sequences deposited in NCBI with accession numbers MZ945565.1 and MZ945600.1, respectively. This suggests that the target CYP450s recovered from gDNA of S. frugiperda collected from the Philippines used in this study were 100% identical or similar to the reference sequence published in the GenBank database.

The Integrity of Resulting dsRNAs

The integrity of dsCYP321A7, dsCYP321A8 and dsGFP were analyzed in 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis run at 100 V for 25 mins which showed the expected size bands of 268, 274, and 352 bp, respectively.

Discussion

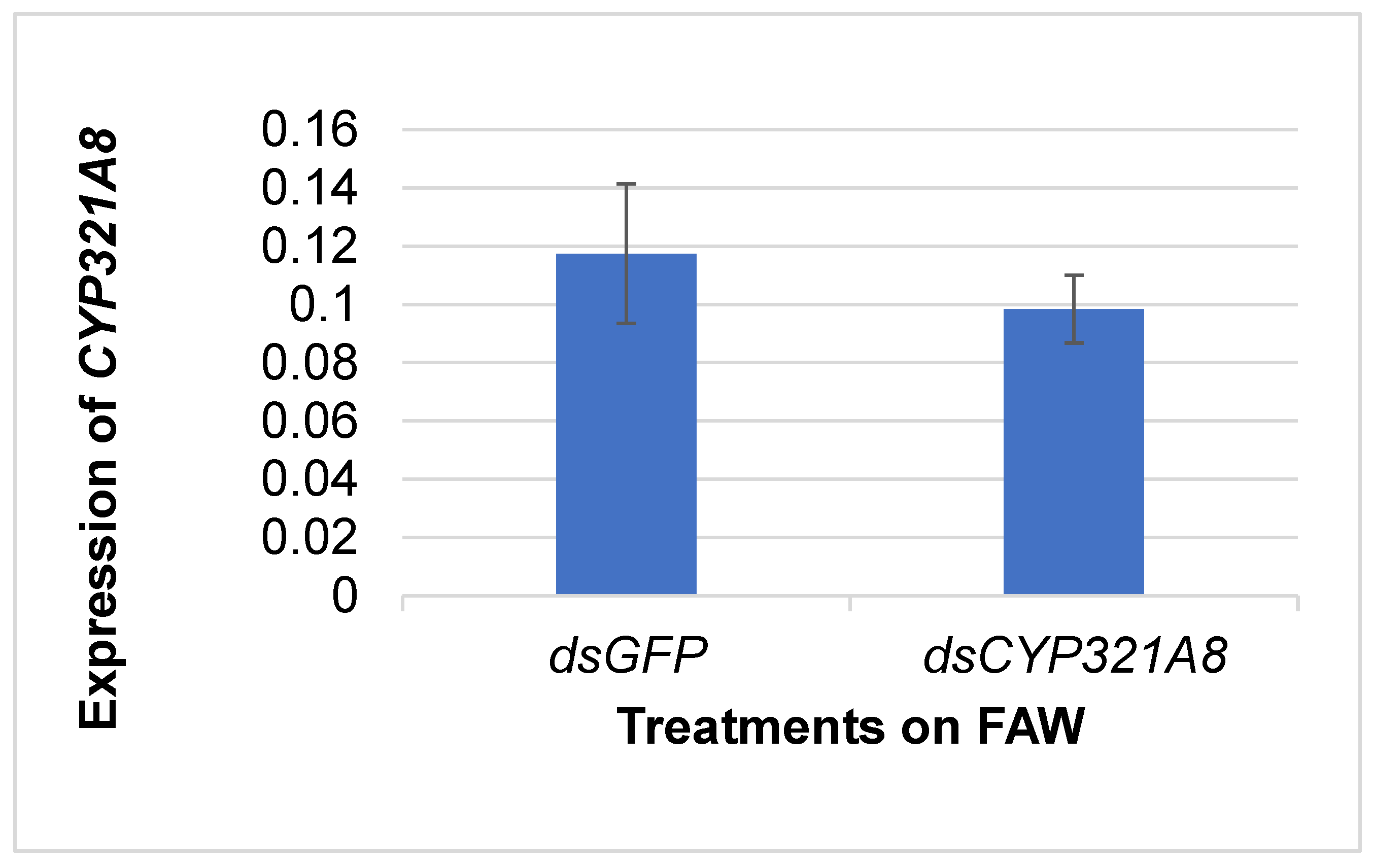

Fall armyworm (FAW) is a destructive pest that has rapidly spread since its first invasion in 2016. While various control methods exist, farmers often rely on insecticides, leading to concerns about resistance. RNA interference (RNAi) offers a promising alternative. This technique effectively regulates gene expression and has shown potential in pest control, making it a valuable tool for developing new FAW management strategies. In this study, we found that the CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 of Philippine FAW population exhibited elevated production following exposure to an insecticide containing both Chlorantraniliprole and Thiamethoxam as dual active ingredients. The efficiency of RNAi was then evaluated and it was observed that CYP450 genes were knocked down.

CYP450 genes can be found in nearly all living things, including bacteria, protists, plants, fungi, and animals (Feyereisen, 2012). One of the molecular changes typically linked with resistant insect populations is the increased production of metabolic enzymes that detoxify or sequester pesticides before they reach the target site (Feyereisen, 2012; Yang, et al., 2020). Enhanced metabolic detoxification of xenobiotics in insects correlates closely with the upregulation of CYP450 protein production and enzymatic activities. Both the induction and constitutive overexpression of insect CYP450s play key roles in detoxifying xenobiotics and facilitating adaptation to fluctuating environments (Lu et al., 2021). In Lepidoptera, several important genes linked to different insecticide resistance mechanisms have been identified. These include CYP321A7 and CYP321A8 in Spodoptera frugiperda after being exposed to indoxacarb and chlorantraniliprole, respectively (Bai-Zhong, et al., 2020; Hafeez, et al., 2022).

FAW populations can resist insecticides through several mechanisms. One of them is rapid detoxification by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP450s) (Lu et al., 2021). Overexpression of some of these CYP450s by the insect leads to an accelerated rate of metabolism, which results in inactivation and, hence, a reduction in the efficacy of the insecticides (Hafeez et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2021). Additionally, insecticide use can create a potent selective pressure, driving the evolution of resistance in fall armyworm populations. This resistance can arise through various mechanisms at the genetic and protein level. At a genetic level, new genes may evolve, or mutations can occur in the promoter regions of existing genes. These promoter mutations can alter gene expression, potentially leading to higher expression levels of enzymes that detoxify insecticides. Alternatively, mutations within protein-coding regions can alter the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein. These changes in protein structure can directly impact the ability of the protein to bind insecticides or perform its normal function, rendering the insecticide ineffective. Finally, even without changes in the protein sequence, modifications like phosphorylation can influence enzyme activity, further contributing to resistance development (Ye et al., 2022).

Sustainable pest management is continually challenged with insect resistance to synthetic insecticides (Hafeez, et al., 2022). Developing pesticide resistance management techniques requires a thorough understanding of the mechanisms through which insects acquire resistance to insecticides (Siddiqui et al., 2023). Repeated use of chemicals would increase the risk of insect resistance to chemicals. Thus, the demand for innovative approaches to controlling pests is highly encouraged. Using RNAi would open new opportunities for FAW management. The concept of RNAi gained prominence after Fire and colleagues’ seminal discovery, which definitively elucidated the biochemical mechanism of gene silencing by introducing purified double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) directly into Caenorhabditis elegans (Fire et al., 1998). RNAi uses dsRNA molecules as triggers to direct the homology-dependent, post-transcriptional mechanism of gene silencing. The primary mechanism utilized for the study and management of insects is the short interfering RNA (siRNA) pathway, whose biological function is to resist exogenous dsRNA (Niebres & Alviar, 2023).

Plants can receive exogenous dsRNAs, siRNAs, and hpRNAs for targeted gene silencing through methods such as spraying, infiltration, injection, spreading, mechanical inoculation, and soaking of roots or seeds. These techniques are broadly utilized to deliver RNA molecules to plants effectively (Das & Sherif, 2020). GreenLight Biosciences’ Calantha (Ledprona) is the first sprayable biopesticide product based on double-stranded RNA that targets the Proteasome Subunit Beta Type-5 in the Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata). It works by “silencing” a crucial gene necessary for the beetle’s survival, effectively controlling this pest without producing a genetically modified organism (Rodrigues et al., 2021). As of December 2023, the biopesticide has been granted registration under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act of USA (ID: EPA-HQ-OPP-2021-0271-0194). Ledprona can now also be retrieved in the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee with group no. of 35, grouped as protein suppressor with mode of action of microbial disruptors of insect midgut membrane (IRAC, 2024). The Bayer “SmartStax Pro” maize (Mon87411), a plant-incorporated protectant, integrates the expression of the Bt Cry3Bt1 toxin, glyphosate resistance, and a dsRNA targeting the Snf7 gene of the western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera). By using RNA interference to silence the gene responsible for transporting transmembrane proteins, mortality of D. v. virgifera is induced, resulting in reduced root damage in corn. Silencing of this gene through RNA interference disrupts the transport of transmembrane proteins, resulting in the mortality of D. v. virgifera, ultimately leading to a decrease in root damage in corn. (De Schutter, et al., 2022).

Numerous studies have already shown the efficacy of RNAi technology in controlling insect pests as well as diseases in laboratory set-ups. To list, the research conducted by Hafeez et al. (2022) demonstrated that administering dsRNAs (CYP321A7 and CYP6AE43) through droplet feeding on artificial diet led to a significant increase in mortality rates among indoxacarb-resistant FAW larvae. Also, Bai-Zhong, et al. (2020) successfully demonstrated RNAi by feeding dsRNA (CYP321A8, CYP321B1, and CYP321A9) and results showed that the second-instar larvae became more sensitive to chlorantraniliprole. Zhang, et al. (2010) proved that chitosan/double-stranded RNA nanoparticles might, therefore, be an effective mediator in RNA interference (RNAi) in mosquito larvae to the chitin synthase genes (AgCHS1 and AgCHS2) by feeding the larvae with these nanoparticles resulted in downregulated transcript abundance by significant folds of AgCHS1.

Successful applications of RNAi to silence genes critical for pest survival and reproduction, such as those involved in growth, development, and fecundity have been studied. The results are promising for the development of RNAi as a tool for pest control, with various delivery methods such as microinjection, oral ingestion, and transgenic plants being tested. Systemic RNAi, where the effect of RNAi spreads throughout the organism, is effective in coleopteran species, although it varies among other insect groups. Challenges in applying RNAi technology, including variable RNAi efficiency across different insect species, the concern that insects may evolve resistance to dsRNA-based products, and the need for efficient delivery systems that protect dsRNA from degradation. Overall, the findings suggest that while RNAi holds significant potential for targeted pest management and gene functional analysis, several technological and biological hurdles need to be addressed to enhance its efficacy and application scope (Zhu & Palli, 2020).

Conclusions

The sensitivity of S. frugiperda to the insecticide with the dual active ingredient of Chlorantraniliprole and Thiamethoxam was increased after the introduction of dsCYP321A7 [14.72 µg/µL] and dsCYP321A8 [14.08 µg/µL] to the 2nd instar FAW larva by feeding with artificial diet.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Department of Science and Technology - Accelerated Science and Technology Human Resource Development Program – Student Research Support Fund. We acknowledge the members of the D110 Insect Vector-Pathogen-Plant Interaction Laboratory cohort 2023-2024, at the University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB) for the unwavering support which has been instrumental in this experiment.

References

- [USAID] United States Agency for International Development. 2018. Feed the Future. Retrieved from Fall armyworm (FAW) management report: evaluating least toxic and cost-effective approaches to FAW management: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00WF1P.

- [IRAC] Insecticide Resistance Action Committee. 2024. Mode of action classification scheme. Retrieved on April 24, 2024, from https://irac-online.org/documents/moa-classification/.

- Agrawal, N.; Dasaradhi, P.V.N.; Mohmmed, A.; Malhotra, P.; Bhatnagar, R.K.; Mukherjee, S.K. RNA Interference: Biology, Mechanism, and Applications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 657–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai-Zhong, Z.; Xu, S.; Cong-Ai, Z.; Liu-Yang, L.; Ya-She, L.; Xing, G.; Dong-Mei, C.; Zhang, P.; Ming-Wang, S.; Xi-Ling, C. Silencing of Cytochrome P450 in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) by RNA Interference Enhances Susceptibility to Chlorantraniliprole. J. Insect Sci. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergé, J.; Feyereisen, R.; Amichot, M. Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and insecticide resistance in insects. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 1998, 353, 1701–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CAPINERA J. 2020. Fall armyworm. Retrieved from Featured Creatures on April 20, 2024, at https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/field/fall_armyworm.htm.

- Chen, H.; Xie, M.; Lin, L.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, F.; Su, W. Transcriptome Analysis of Detoxification-Related Genes in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Insect Sci. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.R.; Sherif, S.M. Application of Exogenous dsRNAs-induced RNAi in Agriculture: Challenges and Triumphs. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, R.; Abrahams, P.; Bateman, M.; Beale, T.; Clottey, V.; Cock, M.; Colmenarez, Y.; Corniani, N.; Early, R.; Godwin, J.; et al. Fall Armyworm: Impacts and Implications for Africa. Outlooks Pest Manag. 2017, 28, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, K.; Taning, C.N.T.; Van Daele, L.; Van Damme, E.J.M.; Dubruel, P.; Smagghe, G. RNAi-Based Biocontrol Products: Market Status, Regulatory Aspects, and Risk Assessment. Front. Insect Sci. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FEYEREISEN R. 2012. Insect CYP genes and P450 enzymes. In Insect Molecular Biology and Biochemistry (pp. 236-316). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guengerich, F.P. Mechanisms of Cytochrome P450-Catalyzed Oxidations. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 10964–10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, M.; Li, X.; Ullah, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Fernández-Grandon, G.M.; Khan, M.M.; Siddiqui, J.A.; Chen, L.; et al. Down-Regulation of P450 Genes Enhances Susceptibility to Indoxacarb and Alters Physiology and Development of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugipreda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 884447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, A.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Q.; Xia, L.; Wu, Y.; Gong, C.; Liu, X.; Jian, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Effects of chlorantraniliprole on the life history traits of fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1155455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, S.; Ren, M.; Tian, X.; Wei, Q.; Mburu, D.K.; Su, J.-Y. The expression of Spodoptera exigua P450 and UGT genes: tissue specificity and response to insecticides. Insect Sci. 2019, 26, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joga, M.R.; Zotti, M.J.; Smagghe, G.; Christiaens, O. RNAi Efficiency, Systemic Properties, and Novel Delivery Methods for Pest Insect Control: What We Know So Far. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.M.; Gadratagi, B.-G.; Paramesh, V.; Kumar, P.; Madivalar, Y.; Narayanappa, N.; Ullah, F. Sustainable Management of Invasive Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Romeis, J. Managing the Invasive Fall Armyworm through Biotech Crops: A Chinese Perspective. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 39, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, K.; Song, Y.; Zeng, R. The role of cytochrome P450-mediated detoxification in insect adaptation to xenobiotics. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2020, 43, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matova, P.M.; Kamutando, C.N.; Magorokosho, C.; Kutywayo, D.; Gutsa, F.; Labuschagne, M. Fall armyworm invasion, control practices, and resistance breeding in Sub-Saharan Africa. Crop Sci. 2020, 60, 2951–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navasero, M.V.; Navasero, M.M.; Burgonio, G.A.; Ardez, K.P.; Ebuenga, M.D.; Beltran, M.J.; Bato, M.B.; Gonzales, P.G.; Magsino, G.L.; Caoili, B.L.; et al. Detection of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) using larval morphological characters, and observations on its current local distribution in the Philippines. Philipp. Entomol. 2019, 33, 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Niebres, C.; Alviar, K.B. Disruption of transmission of plant pathogens in the insect order Hemiptera using recent advances in RNA interference biotechnology. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 113, e22023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitnavare, R.B.; Bhattacharya, J.; Singh, S.; Kour, A.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Arora, N. Next Generation dsRNA-Based Insect Control: Success So Far and Challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanze, J.A.C.; Bob-Manuel, R.B.; Zakka, U.; Kingsley-Umana, E.B. Population dynamics of Fall Army Worm [(Spodoptera frugiperda) J.E. Smith] (Lepidoptera: Nuctuidae) in maize-cassava intercrop using pheromone traps in Niger Delta Region. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omwoyo, C.O.; Mburu, J.; Nzuve, F.; Nderitu, J.H. Assessment of maize yield losses due to the effect of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) infestation: the case of Trans-Nzoia County, Kenya. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phambala, K.; Tembo, Y.; Kasambala, T.; Kabambe, V.H.; Stevenson, P.C.; Belmain, S.R. Bioactivity of Common Pesticidal Plants on Fall Armyworm Larvae (Spodoptera frugiperda). Plants 2020, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, T.B.; Mishra, S.K.; Sridharan, K.; Barnes, E.R.; Alyokhin, A.; Tuttle, R.; Kokulapalan, W.; Garby, D.; Skizim, N.J.; Tang, Y.-W.; et al. First Sprayable Double-Stranded RNA-Based Biopesticide Product Targets Proteasome Subunit Beta Type-5 in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberi, E.; Mondal, M.; Paredes-Montero, J.R.; Nawaz, K.; Brown, J.K.; Qureshi, J.A. Optimal dsRNA Concentration for RNA Interference in Asian Citrus Psyllid. Insects 2024, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCOTT JG. 1999. Cytochromes P450 and insecticide resistance. In Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (Vol. 29). https://www.elsevier.com/locate/ibmb.

- Siddiqui, J.A.; Fan, R.; Naz, H.; Bamisile, B.S.; Hafeez, M.; Ghani, M.I.; Wei, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. Insights into insecticide-resistance mechanisms in invasive species: Challenges and control strategies. Front. Physiol. 2023, 13, 1112278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-L.; He, Y.-N.; Staehelin, C.; Liu, S.-W.; Su, Y.-J.; Zhang, J.-E. Identification of Two Cytochrome Monooxygenase P450 Genes, CYP321A7 and CYP321A9, from the Tobacco Cutworm Moth (Spodoptera Litura) and Their Expression in Response to Plant Allelochemicals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Deng, S.; Wei, X.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Yin, C.; Du, T.; Guo, Z.; Xia, J.; Yang, Z.; et al. MAPK-directed activation of the whitefly transcription factor CREB leads to P450-mediated imidacloprid resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 10246–10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.M.; Song, Y.F.; Sun, X.X.; Shen, X.J.; Wu, Q.L.; Zhang, H.W.; Zhang, D.D.; Zhao, S.Y.; Liang, G.M.; Wu, K.M. Population occurrence of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in the winter season of China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Lin, D.-J.; Cai, X.-Y.; Wang, R.; Hou, Y.-M.; Hu, C.-H.; Gao, S.-J.; Wang, J.-D. Multiple dsRNases Involved in Exogenous dsRNA Degradation of Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 850022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Nayak, B.; Xiong, L.; Xie, C.; Dong, Y.; You, M.; Yuchi, Z.; You, S. The Role of Insect Cytochrome P450s in Mediating Insecticide Resistance. Agriculture 2022, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, K.Y. Chitosan/double-stranded RNA nanoparticle-mediated RNA interference to silence chitin synthase genes through larval feeding in the African malaria mosquito (Anopheles gambiae). Insect Mol. Biol. 2010, 19, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, J. Bacteria-Mediated RNA Interference for Management of Plagiodera versicolora (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Insects 2019, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Meng, J.; Ruan, H.; Yang, C.; Zhang, C. Expression stability of candidate RT-qPCR housekeeping genes in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 108, e21831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.Y.; Palli, S.R. Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges of Insect RNA Interference. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2020, 65, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).