1. Introduction

Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus of the type CC398, also called livestock-associated MRSA, LA-MRSA, appeared in France and the Netherlands around 2004 [

1] and has since spread to most countries in Europe and beyond [

2,

3]. LA-MRSA is particularly associated with pigs but has also been found in a long list of other animal species, such as poultry, mink, horses, dogs and cats [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In most cases, the animals are healthy carriers of LA-MRSA CC398, but it may also cause infections, such as skin, urinary tract, wound and joint infections in pigs, abscesses in mink, mastitis in dairy cattle, or skin-, ear-, wound- or urinary tract infections in dogs [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

LA-MRSA is now widespread in most of the Danish pig herds [

18,

19], which is a dramatic development since the first survey in 2008 [

3].

LA-MRSA is mainly transmitted to humans through direct and indirect contact with infected animals, whereas food is not considered to be a significant source [

20,

21].

People who work in pig herds will invariably be exposed on a daily basis and frequently carry LA-MRSA in their nose, transiently or permanently [

22,

23,

24]. A German study [

25] showed that people who shared a household with employees on pig and poultry herds had an increased risk of also being positive for LA-MRSA, but that people who regularly visited herds, e.g., to buy eggs, actually also had increased risk. Very high carrier rates among farmers, livestock veterinarians and slaughterhouse personnel [

26] have been confirmed and described in more detail by Goerge et al. [

27].

Likewise, Cuni et al. [

23] showed that a very large proportion of people in contact with livestock were infected, while 4 – 5% of their household members were. Infection beyond these groups of people is seen less frequently. Nevertheless, a part of the infections with MRSA in humans is seen to be caused by LA-MRSA, especially in areas with high livestock density [

23], and this number of infections has also been increasing in Denmark but has now reached a plateau [

18,

28] likely because the number of infected pig herds is no longer increasing. Although only few people die as a result of infections with LA-MRSA, this bacterium generally causes the same types of infections as other MRSA lineages [

23].

Recent studies have shown that people who stay only for a short time in an infected herd quickly get rid of the bacteria again, typically within hours or up to a few days, and there was a quantitative relationship between LA-MRSA in air samples from the barn and the numbers of LA-MRSA in nasal swab samples of healthy volunteers [

29]. Bos et al. [

30] found that both duration of exposure and levels of LA-MRSA in air had impact on nasal carriage among farm workers.

This and other observations therefore suggest that there is some degree of dose-response relationship between exposure and level of human contamination. Colonized persons have a higher risk of developing an infection [

27] and therefore, by reducing the amounts of LA-MRSA bacteria in the stable air, it may be possible to reduce the exposure and amounts of LA-MRSA bacteria that the workers in the stables bring out and/or the period during which the employees are positive for LA-MRSA after they have left the barn. Finally, a reduction in the number of LA-MRSA in the barn air will mean that fewer LA-MRSA are discharged into the environment via the ventilation system. It has been shown that LA-MRSA can be detected in both air samples and soil surfaces at a certain distance from infected pig herds [

12,

31]. It was also recently demonstrated that LA-MRSA can be found in pig manure and in soil samples from fields where pig manure has been spread [

32]. It is not yet known whether and to what extent this discharge contributes to the spread of livestock MRSA to humans in the local community but although the risk is considered to be low, there is evidence that it may play a certain role [

33]. It is currently unknown how low the LA-MRSA level must be before they no longer pose any risk for employees and guests carrying the infection with them out of the stables.

Thus, it is relevant to know what the levels of LA-MRSA are in pig herds and in different age groups and sections of the herds. However, only few studies have so far been carried out where LA-MRSA have been quantified, most studies have merely examined samples as positive or negative for LA-MRSA [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Previous investigations have suggested that the highest numbers of LA-MRSA are present in the weaning sections, and the lowest numbers in the gestation sections [

15], and there are reports that show that the proportion of positive samples decreases from the beginning to the end of the fattening period [

34,

35,

36]. The proportion of positive samples has been shown to depend on many other factors, not associated with the pigs, e.g., bedding, cleaning and disinfection routines, general hygiene, and there can be considerable herd-to-herd differences [

34,

35,

36,

38,

39].

The aim of the present investigation was to quantify LA-MRSA levels in a herd of slaughter pigs and track any changes over time. We monitored LA-MRSA levels in pigs from 30 kg until slaughter by analyzing nasal swabs at three time points: upon arrival from the weaning section, midway through the rearing period, and just before slaughter. Additionally, we measured LA-MRSA levels in air and dust samples within the herd.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Herd

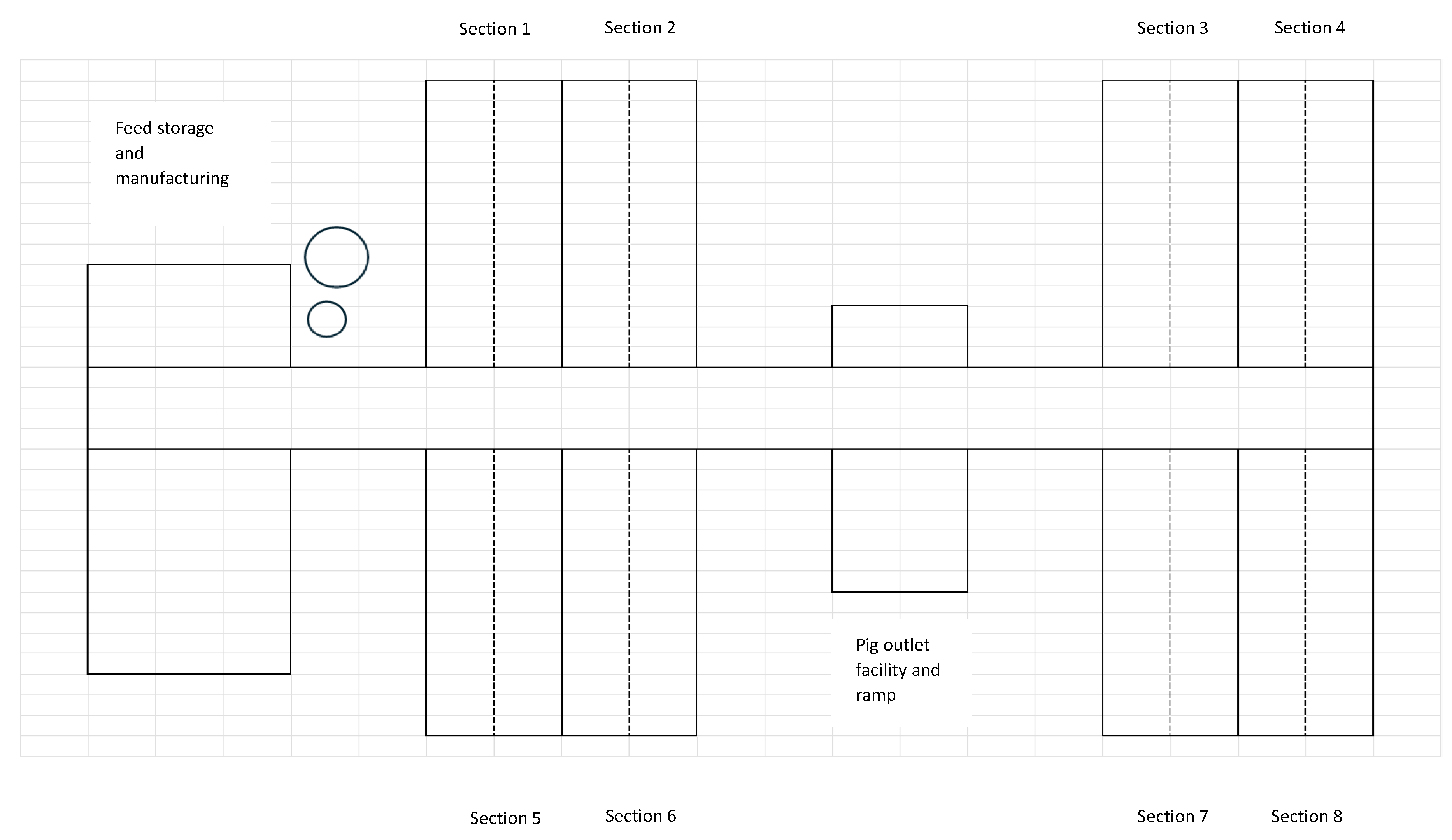

The investigations were carried out in a conventional full-scale production herd with a capacity of 4,000 slaughter pigs. The herd received 11-week-old pigs of approximately 30 kg from a nursery herd located at another site owned by the same producer. Pigs were L × Y × D (Landrace × Yorkshire × Duroc) crossbreed. The herd was an SPF (specific pathogen free) herd but reinfected with

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 6 and 12. It consisted of eight identical sections located as four coherent buildings, two on each side of a central aisle, with each building holding two identical sections (

Figure 1). Each section was 493 m

2 and 1,380 m

3 and designed to house 500 slaughter pigs distributed in 28 pens, each 2.4 m x 6.3 m. The 28 pens were arranged in two rows of 14 pens separated by a central aisle. The ventilation was a common diffuse ventilation system, and the pigs were fed a standard wet feed. All 500 pigs in a section shared the same airspace, which was separated from the airspace of the other sections. The eight sections were stocked with pigs over a 4 - 5 weeks period, with two sections being filled at a time. For each section, a strict all in-all out policy was applied. The pigs stayed in the herd for appr. 11 weeks, with the first pigs from a section being sent to slaughter after appr. nine weeks. Thereafter, the whole section was cleaned and washed with a high-pressure cleaner, but no detergent or disinfectant was used. After washing, the house was dried at 30

oC for two days using a heat canon. The time cycle of a section was thereby 13 weeks, after which a new batch of pigs was introduced.

The herd was used in a big trial where the potential effect of four different intervention strategies against LA-MRSA were tested under full-scale production conditions. The interventions were: (1) recirculation of air through a device that washed away dust particles and treated the air with ozone and UV light, (2) daily spraying of the premises and animals with electrolyzed water, along with incorporating it in the feed, (3) spraying the premises and the pigs with a dust-precipitating chemical twice a day, and (4) application of a commercial disinfectant powder product, developed for use in herds. None of the technologies had an effect on LA-MRSA levels compared to control groups, nor did they impact feed conversion ratios, daily weight gain, or the prevalence of common pig pathogens such as enterotoxigenic

Escherichia coli,

Brachyspira pilosicoli, and

Lawsonia intracellularis. For detailed descriptions of the experiments and results, see Bækbo et al. [

40]. In the present investigation, we analyzed data from all control groups in those experiments, which included a total of seven batches of pigs, representing 3,500 animals.

2.2. Sampling

Samples were collected from seven batches of 500 pigs as described below.

2.2.1. Nasal Swab Samples from Pigs

Nasal swab samples were collected using flocked swabs (ESwab, Copan Diagnostics Inc., Murrieta, CA, USA). Samples were taken by swabbing with a rotating movement appr. 1 cm inside each nostril with a dry swab. Each swab was rotated three times in both the left and right nostrils, then placed in its corresponding tube containing 1 ml saline [

17]. A total of 24 randomly selected pigs were sampled from each batch at each sampling. Each section was sampled at three time points: i) the first week after arriving at the section, ii) during the fourth week, and iii) during week 8, shortly before the first pigs from the section were sent for slaughter.

2.2.2. Dust Samples

Dust samples were collected by brushing dust from the surfaces of equipment into a sterile plastic container with a sterile gloved hand. Two dust samples were taken at each sampling, representing different areas of the section. Dust samples were collected at the same time as the nasal swab samples. In most cases, it was not possible to sample dust at the first sampling in week 1, as no dust had yet settled on surfaces.

2.2.3. Air Samples

Air samples were collected using a Sartorius Airport MD8 sampling device (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany). Two samples were taken on each sampling occasion, resulting in a total of 42 air samples. Samples were collected 1.5 meters above the floor, to simulate the typical height at which farm workers are exposed to airborne substances. Samples were collected over a 5-minute period as the person walked slowly down the aisle to ensure a representative sample from the entire section. Air was filtered through a gelatin filter, capturing all bacteria. The Sartorius machine was decontaminated with ethanol before each sampling, and the filter was handled with sterile tweezers. Air samples were collected at the same time as the nasal swab samples.

2.2.4. Transport from Herd to Laboratory

Samples were placed in an insulated box with cooling elements immediately after collection. The box was sent the same afternoon to the laboratory by courier transport and was received the following morning at the laboratory. Analyses began immediately upon receipt.

2.3. Culture and Identification

2.3.1. Nasal Swab Samples

MRSA in swabs was quantified by directly inoculating 100 µl of the transport medium, along with a 10-1 dilution in phosphate-buffered saline onto selective Brilliance MRSA2 agar plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 18 – 24 hours. Colonies were counted and expressed as colony forming units (cfu)/swab. In case of overgrowth of MRSA colonies, an additional 10-fold dilution was prepared and plated.

Samples that tested negative by direct inoculation were further examined for qualitative detection of MRSA by enriching the remaining transport medium in Mueller-Hinton Broth with 6.5% NaCl, followed by incubation at 37°C for 18-24 hours. Subsequently, 10 μl of the enriched broth was streaked onto Brilliance MRSA2 agar and read after incubation at 37°C for 18-24 hours.

Representative MRSA suspect colonies were subcultured on blood agar plates and verified as

Staphylococcus aureus by MALDI-TOF as previously described [

46,

47]. Verification of MRSA by PCR detection of the

mecA gene was performed on individual colonies as described by Hansen et al. [

4]

2.3.2. Dust Samples

Dust samples were examined by suspending 0.5 g of dust in 4.5 ml sterile saline. Serial 10-fold dilutions (10-1, 10-2, and 10-3), were then made in sterile saline. For each dilution, 100 µl was plated onto Brilliance MRSA2 agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 18 – 24 hours. Colonies were counted and calculated as cfu/g of dust. Representative colonies were tested to confirm MRSA as described above.

2.3.3. Air Samples

Immediately after sampling at the farm, gelatin filters were transferred from the Sartorius air sampler to MRSA2 agar plates. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 hours. After incubation, colonies were counted and verified as described above. Counts were calculated and expressed as cfu/m3 air.

2.4. Statistics

Colony-forming units were log-transformed and tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way ANOVA was used to compare counts from the first, second and third sampling times, followed by pairwise comparisons conducted using t-test. If the data were not normally distributed according to the Shapiro-Wilk test, a Mann Whitney U test was used instead. Similar comparisons were made between the seven groups at each sampling time. Calculations and visualizations were done using Statistics Kingdom on-line calculators (

www.statskingdom.com). For nasal swab samples where LA-MRSA was not detected by direct inoculation but was subsequently detected after enrichment, the cfu count was assigned as half the detection limit (5 cfu). For negative samples, the counts were set to 1 cfu, which becomes 0 after log-transformation.

3. Results

3.1. Nasal Swab Samples

From each of seven batches of 500 pigs, 24 nasal swab samples were collected at three time points during the rearing period, i.e., 168 samples per batch, and 504 samples in total. All nasal swab samples were found positive for LA-MRSA, 494 of them by direct plating, 10 only after enrichment. The highest number of LA-MRSA in a sample was 353,000 cfu, whereas the 10 samples that were positive only after enrichment presumably had 1 – 10 cfu. Two samples had more than 100,000 cfu while 22 had between 10,000 and 100,000, all of them at the first or second sampling.

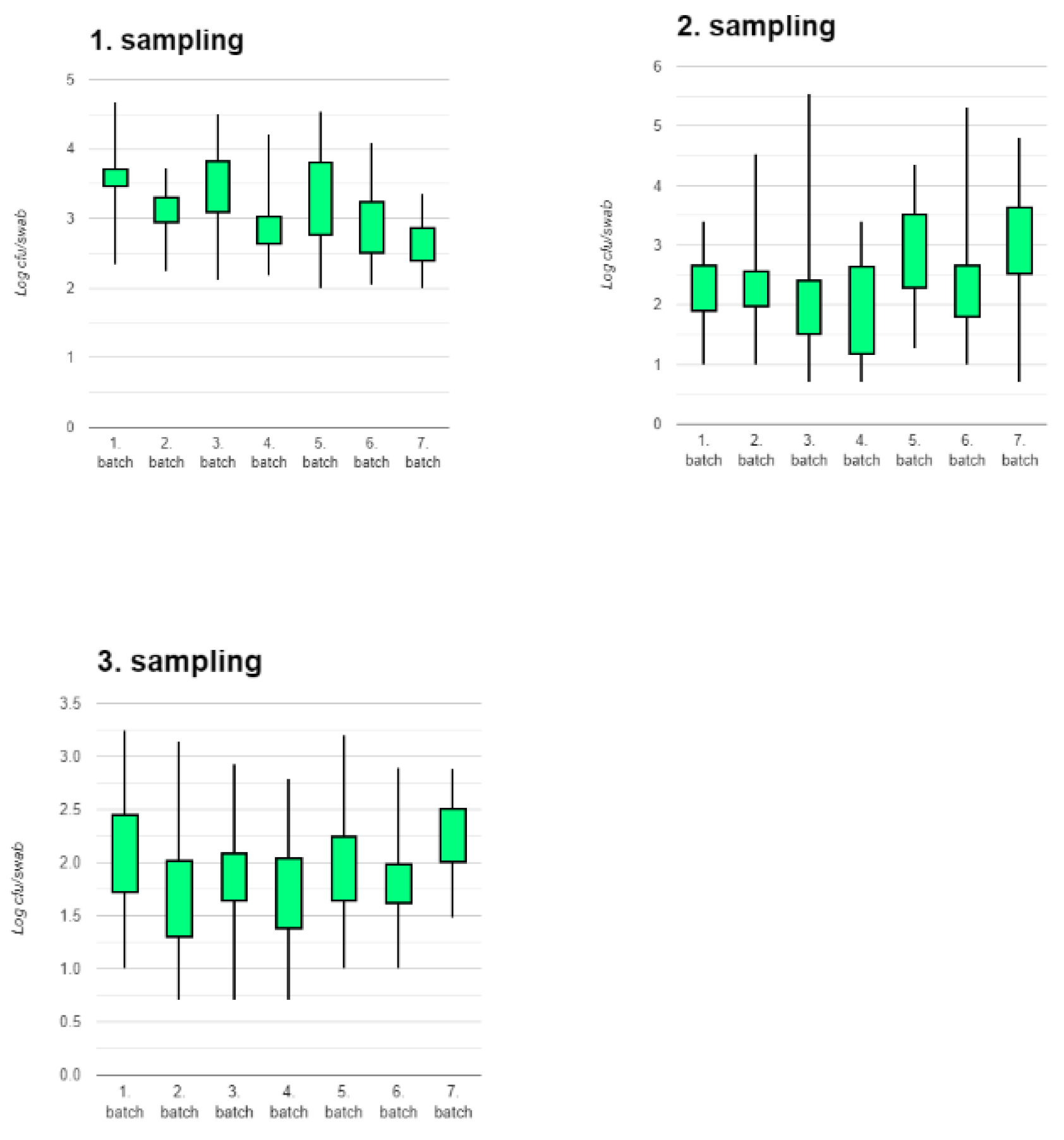

There were statistically significant differences both between batches of pigs at the same sampling time and between sampling times.

Figure 2 shows the counts for each batch at the three sampling times. It is evident that even though the pigs were treated identically from birth to slaughter, there was significant batch – to – batch variation (1. sampling: p=2.471 × 10

-10, 2. sampling: p=1.334 × 10

-5, 3. sampling: p= 6.443 × 10

-4).

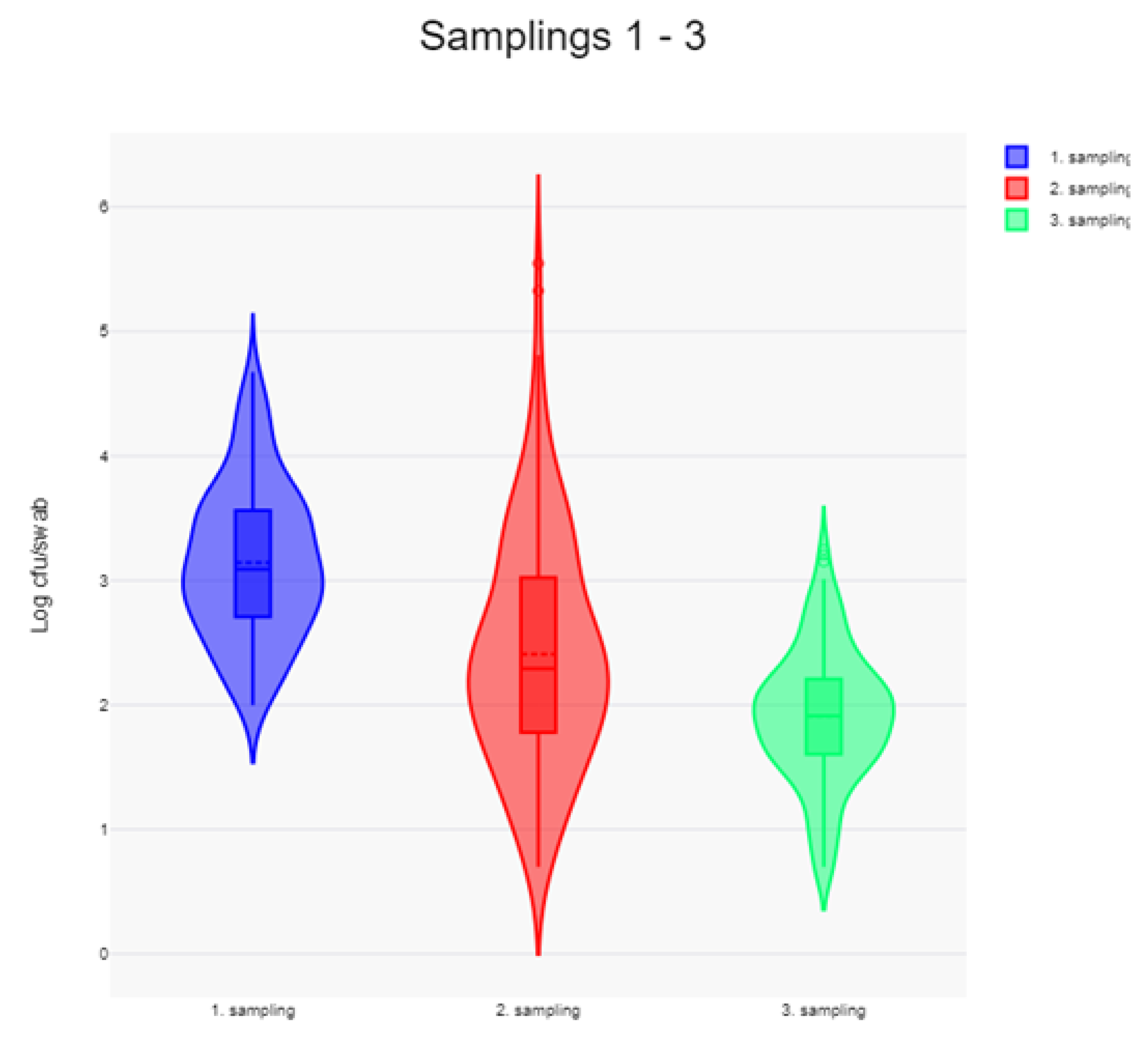

When comparing LA-MRSA levels in all samples at each sampling time (

Figure 3), there was a significant reduction in counts from first to second sampling (p=6.66 × 10

-16) and again from second to third sampling (p=3.668 × 10

-9). The mean count at first sampling was 1,387 cfu/swab (log

10 cfu = 3.142) and this was reduced by 81.5% at second sampling and by 94.1% at third sampling.

The figures for each batch of pigs are shown in Supplementary

Figure 1. For all batches except for batch 7, there was a decrease in counts from first to second sampling and for all batches again from second to third sampling. In general, the largest reduction in counts occurred between the first and second sampling.

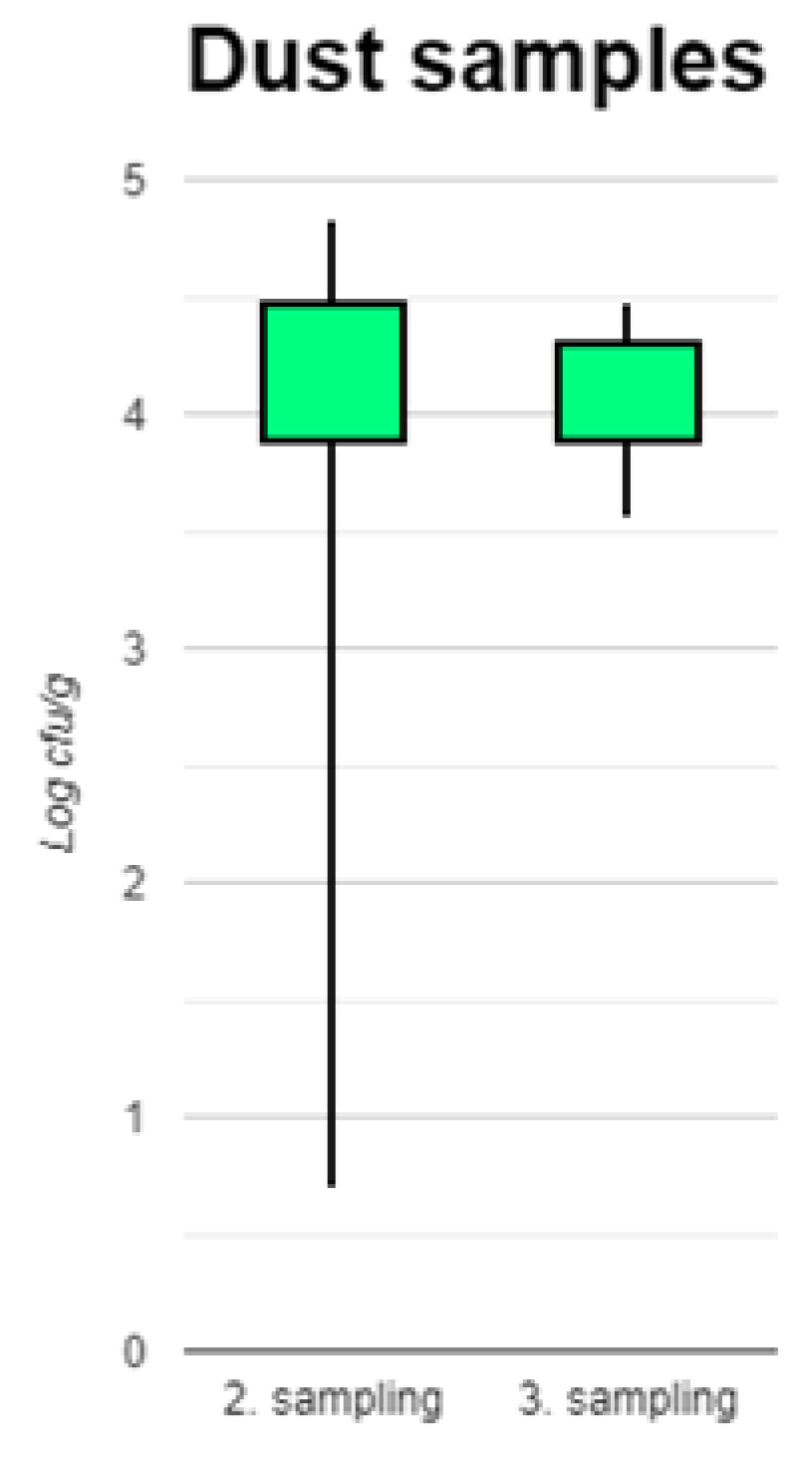

3.2. Dust Samples

At the first sampling time, the section had recently been cleaned, resulting in little or no dust available to collect in most cases. Therefore, only counts from the 28 samples collected during the second and third sampling are shown (

Figure 4). There was no significant difference in log

10 cfu/g between the two time points (p=0.8541). The highest count in a sample was 37,272 cfu/g and the overall mean was 17,185 cfu/g. A single sample was positive only after enrichment, i.e., with 1-10 cfu/g. However, the second sample taken at the same time from that batch had 5,454 cfu/g. All other samples had >1,000 cfu/g.

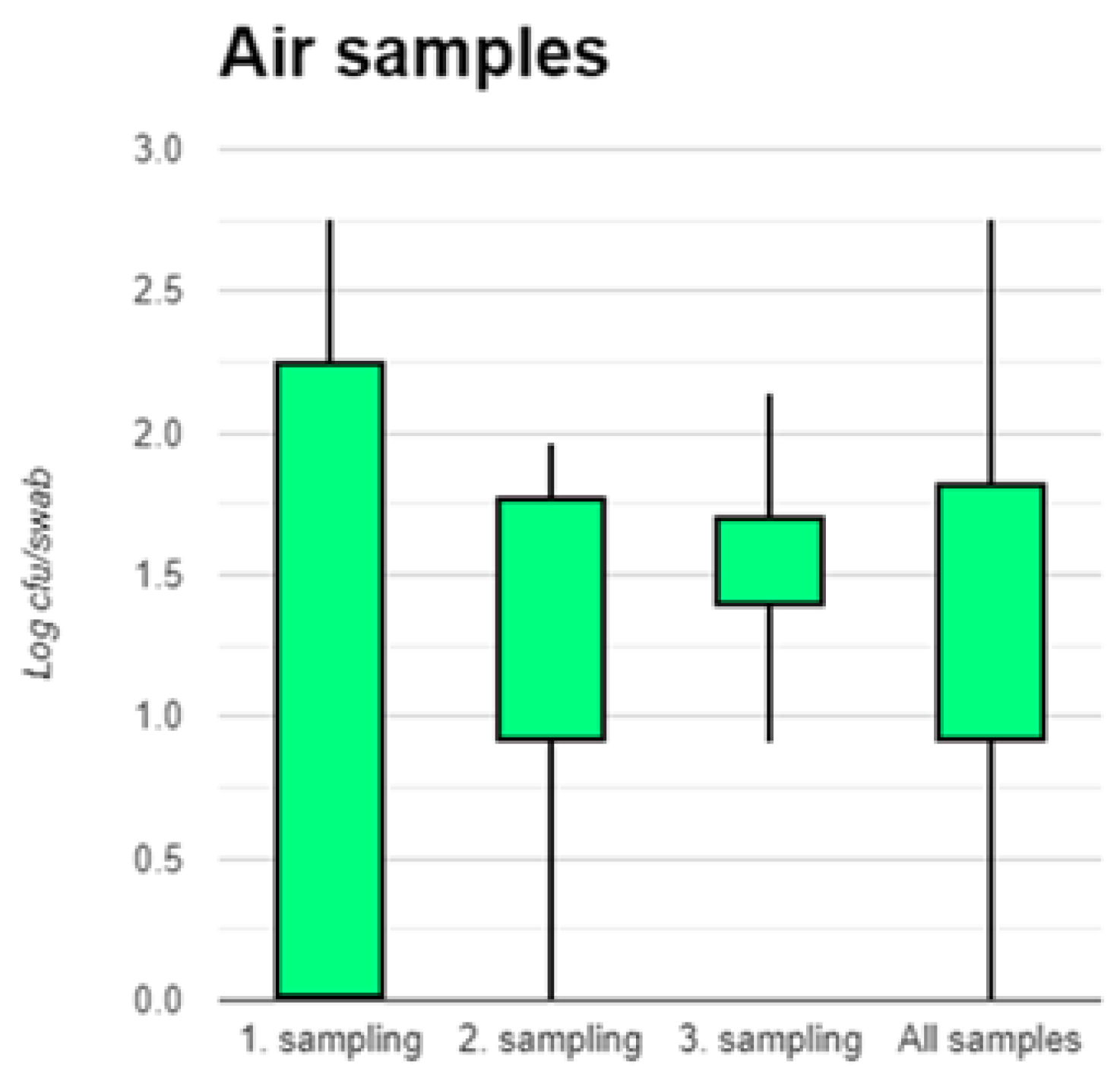

3.3. Air Samples

Counts of LA-MRSA in the 42 air samples were low, mean 63 cfu/m

3, median 28 cfu/m

3, and range 0 – 568 cfu/m

3. Since there was no statistical difference between counts at the three sampling points, all counts are shown together in

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

4.1. LA-MRSA Quantification

Most reports on levels of LA-MRSA in pig herds have not quantified numbers of the bacterium in each sample, but rather counted the number of samples with presence/absence of LA-MRSA. In this study, our quantitative approach revealed a 94% reduction in average LA-MRSA counts in nasal swabs from 30 kg pigs until slaughter, a finding that would not have been identified using a qualitative approach. Quantitative data are therefore essential for identifying high-exposure times and locations, as well as for discussing potential intervention points. This approach also broadens the possibilities for evaluating intervention effectiveness and designing future studies to reduce LA-MRSA exposure for farmers, making them more accurate by quantifying LA-MRSA loads. Additionally, our investigation shows that consistent LA-MRSA levels across batches cannot necessarily be expected, even when pigs originate from the same breeding farm and are raised under similar conditions, such as those present at this farm. The observed variation suggests the presence of other factors that significantly influence LA-MRSA levels, highlighting the importance of optimizing the amount of quantitative data to manage LA-MRSA exposure and understand its dynamics within farms.

Hansen [

15] found the highest LA-MRSA levels in nasal swabs from weaning sections, followed by farrowing sections, with the lowest levels found in gestation sections (no slaughter pigs were included in that study). Our study observed higher LA-MRSA nasal counts than Hansen’s findings but lower levels in air samples [

15]. Both studies found a correlation between air and nasal swab LA-MRSA counts. Verkola et al. [

43] reported even lower LA-MRSA levels in nasal swabs, indicating farm-specific dynamics likely influenced by multiple factors. The marked differences in LA-MRSA levels between individual pigs raise the possibility of some individual pigs acting as super-shedders of LA-MRSA, as previously suggested (persistently colonized pigs carrying high LA-MRSA levels) [

44]. However, because we did not collect samples from the exact same animals on the three sampling occasions, we cannot confirm the presence of pigs with these characteristics. Altogether, the observed variations highlight the need for farm-specific reference LA-MRSA counts when designing effective control measures and studies focused on reducing LA-MRSA exposure.

Despite the reduction of LA-MRSA levels in pigs towards the end of the production cycle, we found high LA-MRSA levels in dust samples during the second and third sampling, supporting the idea that LA-MRSA is able to survive in dust for extended periods. The survival of LA-MRSA on surfaces over time is well documented, including on polypropylene (half-life 11-16 days) and stainless steel (half-life 2–8 days), while survival was limited on other surfaces such as concrete [

45]. These findings emphasize the importance of cleaning and disinfection, as well as considering the materials present in the stables when attempting a reduction of LA-MRSA. Surface materials, bedding, and cleaning and disinfection procedures all play significant roles in the persistence of LA-MRSA throughout the production cycle. For example, pigs on straw bedding have been shown to be more often negative for LA-MRSA than those on other types of flooring, perhaps due to competitive mechanisms between LA-MRSA and microorganisms from the straw [

35]. Competitive associations between LA-MRSA and other bacteria colonizing the nose and skin of pigs have also been reported [

46]. Similar to bedding, cleaning without disinfection was associated with more LA-MRSA-free animals at the end of the rearing period compared to cleaning combined with disinfection [

35]. This may seem contradictory; however, some have suggested that the use of quaternary ammonium-based disinfectants may be counterproductive due to the possible presence of genes conferring resistance to these compounds [

47].

LA-MRSA air loads not only affect indoor environments but also impact areas outside farm stables. The large volume of air exhausted from pig farms - several thousand m

3 per hour, especially during warm periods - spreads LA-MRSA widely with the wind. Schultz et al. [

31] demonstrated this by detecting LA-MRSA in soil samples collected in the vicinity of pig farms, particularly downwind. In addition, LA-MRSA has been found in pig manure, where it may survive for extended periods and be spread on agricultural fields when the manure is used as fertilizer [

32]. Consequently, LA-MRSA presents a significant one-health risk, involving pigs, farm workers, the community, and the environment.

Our study provides abundant data produced with selected methods for sample collection and laboratory analysis, which were piloted prior to the large intervention trials mentioned above. These methods were easy to implement on farms, allowed for the collection of a large number of samples in a single sampling campaign, and were straightforward to continue with subsequent laboratory analyses. It is slightly more laborious to make ten-fold dilutions and count colonies than to just register growth/no growth, but the results are considerably more informative.

4.2. Reducing LA-MRSA Levels and Exposure

The factors influencing the success or failure of interventions aimed at reducing LA-MRSA in pig farms are marginally understood. While commonly used disinfectants have shown efficacy against MRSA

in vitro, their effectiveness in real-life conditions at production farms remains uncertain. Several studies indicate that cleaning and disinfection between batches can effectively reduce LA-MRSA levels in the subsequent batch [

34,

35,

36,

39]. However, a Danish trial found that disinfectants applied on pigs, equipment, and bedding did not significantly impact on LA-MRSA levels or production parameters [

48]. Washing and disinfecting the skin of sows before and after farrowing, temporarily reduced LA-MRSA levels [

38]. Other tested interventions such as the use of biocides, ozone, UV light, and dust reduction, have also shown no significant effect compared to control groups [

40].

Experience suggests that once LA-MRSA is introduced into a pig farm, it will remain positive. This is reflected in the lack of reports describing spontaneous eradication of LA-MRSA in pig farms and is supported by simulation studies suggesting that reducing MRSA levels is challenging [

49,

50]. It remains unclear whether the reservoir within the farm is primarily the environment or the animals. Some studies suggest the presence of persistently colonized pigs [

44], while others note that pigs in organic outdoor production systems may remain LA-MRSA-free [

34].

The only successful intervention to date is Norway's zero-tolerance strategy, where LA-MRSA-infected herds are immediately culled, cleaned, and disinfected, with contact herds also being tested and culled if found positive [

20,

51]. This strategy is costly and likely sustainable only in countries with low LA-MRSA prevalence, such as Norway. In countries with high density of pig farms and frequent pig transport, such as Germany, Denmark, or Belgium, this approach may be impractical due to the lack of economic incentives and the non-food-borne nature of LA-MRSA.

Efforts to reduce antibiotic use have shown mixed results in LA-MRSA prevalence. Dutch studies indicated that reducing antibiotic use correlated with lower MRSA prevalence in pigs and cattle [

52,

53]. However, other studies found no such correlation [

54]. A Danish study showed that reducing zinc and tetracycline reduced LA-MRSA in pigs, but this was under experimental conditions and not in production settings [

55].

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we were able to demonstrate a significant decrease of appr. 95% of the numbers of LA-MRSA in nasal swab samples in pig from weaning until slaughter. All nasal swab samples were positive for LA-MRSA, which highlights the importance of quantification of the bacterium for making estimations of changes in carriage. We also found significant batch-to-batch differences in nasal carriage of LA-MRSA, which demonstrates that although all pigs originated from the same herd and were raised under identical conditions, there are factors that influence on the carriage of LA-MRSA. Levels of LA-MRSA in air samples were in general low mean counts 63 cfu/m3 (range 0 – 568), but high in dust samples, mean 17,186 cfu/g. Dust may therefore be a significant source of exposure for herd workers. More research is needed in quantification of LA-MRSA in pig farms across farm size, animal age groups, management and breeding procedures. This will enable the design of intervention strategies and validation of their effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KP; methodology, KP, CEG, PB; software, MWN, CEG; formal analysis, MWN, MEF, CEG; resources, KP, PB; data curation, MWN, MEF, CEG; writing—original draft preparation, KP; writing—review and editing, KP, MVN, MEF, CEG, PB; supervision, KP, CEG, PB; project administration, KP; funding acquisition, KP, PB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark through The Danish Agrifish Agency to the OHLAM project, grant no. 33010-NIFA-14-612, and a grant from the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. Collecting nasal swab samples from pigs and sampling of air and dust on farms in Denmark does not require an ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. A written agreement with the farmer was made.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Technical staff at SEGES Innovation P/S is gratefully acknowledged for collecting all the samples. The technical assistance of Ms. Margrethe Carlsen in doing the laboratory work is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Voss, A.; Loeffen, F.; Bakker, J.; Klaassen, C.; Wulf, M. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pig farming. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1965–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekkerkerk, W. S. N.; van de Sande-Bruinsma, N.; van der Sande, M. A. B.; Tjon-A-Tsien, A.; Groenheide, A.; Haenen, A.; Timen, A.; van den Broek, P.J.; van Wamel, W.J.B.; de Neeling, A.J.; Richardus, J.H.; Verbrugh, H.A.; Vos, M.C. Emergence of MRSA of unknown origin in the Netherlands. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 656–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Analysis of the baseline survey on the prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in holdings with breeding pigs, in the EU, 2008 - Part A: MRSA prevalence estimates. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E.; Larsen, A.R.; Skov, R.L.; Chriél, M.; Larsen, G.; Angen, Ø.; Larsen, J.; Lassen, D.C.K.; Pedersen, K. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is widespread in farmed mink (Neovison vison). Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 207, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fertner, M.; Pedersen, K.; Chriél, M. Experimental exposure of farmed mink (Neovison vison) to livestockassociated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus contaminated feed. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 231, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duijkeren, E.; Moleman, M.; Sloet van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan, M. M.; Multem, J.; Troelstra, A.; Fluit, A. C.; van Wamel, W.J.B.; Houwers, D.J.; de Neeling, A.J.; Wagenaar, A.J. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in horses and horse personnel: An investigation of several outbreaks. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 141, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, D.; Blanco, J.; Tormo-Más, M.Á.; Selva, L.; Guinane, C.M.; Baselga, R.; Corpa, J.M.; Lasa, Í.; Novick, R.P.; Fitzgerald, J.R.; Penadés, J.R. Adaptation of Staphylococcus aureus to ruminant and equine hosts involves SaPI-carried variants of von Willebrand factor-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 77, 1583–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, K. Prevention and control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in equine hospitals in Sweden. PhD thesis, Swedish University of Agriculture, Uppsala, Sweden, 2013.

- Graveland, H.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Heesterbeek, H.; Mevius, D.; van Duijkeren, E.; Heederik, D. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in veal calf farming: human MRSA carriage related with animal antimicrobial usage and farm hygiene. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graveland, H.; Duim, B.; van Duijkeren, E.; Heederik, D.; Wagenaar, J. A. Livestock associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in animals and humans. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 301, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuny, C.; Friedrich, A.; Kozytska, S.; Layer, F.; Nübel, U.; Ohlsen, K.; Strommenger, B.; Walther, B.; Wieler, L.; Witte, W. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in different animal species. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 300, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, A.; Schulz, J.; Hoehle, L.; Fetsch, A.; Tenhagen, B.A.; Hartung, J.; Roesler, U. Occurrence of MRSA in air and housing environment of pig barns. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 158, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, S.; Kadlec, K.; Strommenger, B. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius detected in the BfT-GermVet monitoring programme 2004 – 2006 in Germany. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fessler, A.; Scott, C.; Kadlec, K.; Ehricht, R.; Monecke, S.; Schwarz, S. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 from cases of bovine mastitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Danish production animals. PhD Thesis, . Danish Technical University, National Veterinary Institute, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ronco, T.; Stegger, M.; Pedersen, K. Draft genome sequence of a sequence type 398 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate from a Danish dairy cow with mastitis. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00492–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E., T.; Ronco, M. Stegger, R.N. Sieber, M.E. Fertner, H.L. Martin, M. Farre, N. Toft, A.R. Larsen, K. Pedersen. MRSA CC398 in dairy cattle and veal calf farms indicates spillover from pig production. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2733. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DANMAP 2016. Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark. Technical University of Denmark and Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark, ISSN 1600-2032, www.DANMAP.org, 2017.

- Agersø, Y.; Hasman, H.; Cavaco, L.M.; Pedersen, K.; Aarestrup, F.M. Study of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Danish pigs at slaughter and in imported retail meat reveals a novel MRSA type in slaughter pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 157, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish Veterinary and Food Administration. MRSA Risiko og håndtering. Rapport ved MRSA-ekspertgruppen. 2017. https://www.foedevarestyrelsen.dk/SiteCollectionDocuments/Dyresundhed/Dyresygdomme/15082017%20MRSA%20rapport.pdf.

- Kluytmans, J. A. J. W. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in food products: cause for concern or case for complacency? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 11–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuny, C.; Nathaus, R.; Layer, F.; Strommenger, B.; Altmann, D.; Witte, W. Nasal colonization of humans with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) CC398 with and without exposure to pigs. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuny, C.; Wieler, L.; Witte, W. Livestock-associated MRSA: The impact on humans. Antibiotics 2015, 4, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahms, C.; Hübner, N.-O.; Cuny, C.; Kramer, A. Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in farm workers and the livestock environment in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany. Acta Vet. Scand. 2014, 56, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisdorff, B.; Scholhölter, J.L.; Claussen, K.; Pulz, M.; Novak, D.; Radon, K. MRSA-ST398 in livestock farmers and neighbouring residents in a rural area in Germany. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 1800–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.J.; Bos, M.E.H.; Duim, B.; Urlings, B.A.P.; Heres, L.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Heederik, D.J.J. Livestock-associated MRSA ST398 carriage in pig slaughterhouse workers related to quantitative environmental exposure. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerge, T.; Lorenz, M.B.; van Alen, S.; Hübner, N.-O.; Becker, K.; Köck, R. MRSA colonization and infection among persons with occupational livestock exposure in Europe: Prevalence, preventive options and evidence. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 200, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DANMAP 2022. Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark. Technical University of Denmark and Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark, ISSN 1600-2032, www.DANMAP.org, 2023.

- Angen, Ø.; Feld, L.; Larsen, J.; Rostgaard, K.; Skov, R. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to human volunteers visiting a swine farm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, M.E.H.; Verstappen, K.M.; van Cleef, B.A.G.L.; Dohmen, W.; Dorado-García, A.; Graveland, H.; Duim, B.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Kluytmans, J.A.J.W.; Heederik, D.J.J. Transmission through air as a possible route of exposure for MRSA. J. Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiol. 2016, 26, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.; Friese, A.; Klees, S.; Tenhagen, B. A.; Fetsch, A.; Rösler, U.; Hartung, J. Longitudinal study of the contamination of air and of soil surfaces in the vicinity of pig barns by livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5666–5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astrup, L.B.; Hansen, J.E.; Pedersen, K. Occurrence and survival of livestock-associated MRSA in pig manure and on agriculture fields. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.A.; Curriero, F.C.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Nachman, K.E.; Schwartz, B.S. High-density livestock operations, crop field application of manure, and risk of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in Pennsylvania. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1980–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobusch, I.; Schröter, I.; Linnemann, S.; Schollenbruch, H.; Hofmann, F.; Boelhauve, M. Prevalence of LA-MRSA in pigsties: analysis of factors influencing the (de)colonization process. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollenbruch, H.; Kobusch, I.; Schröter, I.; Mellmann, A.; Köck, R.; Boelhauve, M. Pilot Study on Alteration of LA-MRSA Status of Pigs during Fattening Period on Straw Bedding by Two Types of Cleaning. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merialdi, G.; Galletti, E.; Guazzetti, S.; Rosignoli, C.; Alborali, G.; Battisti, A.; Franco, A.; Bonilauri, P.; Rugna, G.; Martelli, P. Environmental methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus contamination in pig herds in relation to the productive phase and application of cleaning and disinfection. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 94, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangerter, P.D.; Sidler, X.; Perreten, V.; Overesch, G. Longitudinal study on the colonisation and transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pig farms. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 183, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pletinckx, L.J.; Dewulf, J.; De Bleecker, Y.; Rasschaert, G.; Goddeeris, B.M.; De Man, I. Effect of a disinfection strategy on the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC398 prevalence of sows, their piglets and the barn environment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobusch, I.; Mellmann, A.; Köck, R.; Boelhauve, M. Single blinded study on the feasibility of decontaminating LA-MRSA in pig compartments under routine conditions. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bӕkbo, P.; Sommer, H.M.; Pedersen, K.; Nielsen, M.W.; Fertner, M.E.; Espinosa-Gongora, C. Forsøg med nedsӕttelse af forekomsten af MRSA i grise og i staldmiljø. SEGES Meddelelse nr. 1185, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmmod, Y.; Nonnemann, B.; Svennesen, L.; Pedersen, K.; Klaas, I. Typeability of MALDI-TOF assay for identification of non-aureus staphylococci associated with bovine intramammary infections and teat apex colonization. J Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 9430–9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnemann, B.; Svennesen, L.; Lyhs, U.; Kristensen, K.A.; Klaas, I.C.; Pedersen, K. Bovine mastitis bacteria resolved by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry. J Dairy Sci 2019, 102, 2515–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkola, M.; Takala, M.; Nykäsenoja, S.; Olkkola, S.; Kurittu, P.; Kiljunen, S.; Tuomala, H.; Järvinen, A.; Keikinheimo, A. Low-level colonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pigs is maintained by slowly evolving, closely related strains in Finnish pig farms. Acta Vet. Scand. 2022, 64, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Gongora, C.; Dahl, J.; Elvstrøm, A.; van Wamel, W.J.; Guardabassi, L. Individual predisposition to Staphylococcus aureus colonization in pigs on the basis of quantification, carriage dynamics, and serological profiles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, K.; Frosth, S.; Pedersen, K.; Rosendal, T.; Sternberg Lewerin, S. Survival of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC398 on different surface materials. Acta Vet. Scand. 2023, 65, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strube, M.L.; Hansen, J.E.; Rasmussen, S.; Pedersen, K. A detailed investigation of the porcine skin and nose microbiome using universal and Staphylococcus specific primers. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slifierz, M.J.; Friendship, R.M.; Weese, J.S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in commercial swine herds is associated with disinfectant and zinc usage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 2690–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bækbo, P.; Mølgaard Sommer, H.; Espinosa-Gongora, C.; Pedersen, K.; Toft, N. Ingen effekt af biocidet Biovir på forekomsten af MRSA i stalden. SEGES Svineproduktion, Den Rullende Afprøvning. Meddelelse Nr. 1144, 2018.

- Schultz, J.; Boklund, A.; Toft, N.; Halasa, T. Effects of control measures on the spread of LA-MRSA among Danish pig herds between 2006 and 2015 – A simulation study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, A.I.V.; Rosendal, T.; Widgren, S.; Halasa, T. Mechanistic modelling of interventions against livestock associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus within a Danish farrow-to-finish pig herd. Plos One 2018, 13, e0200563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstrøm, P.; Grøntvedt, C.A.; Gabrielsen, C.; Stegger, M.; Angen, Ø.; Åmdal, S.; Enger, H.; Urdahl, A.M.; Jore, S.; Steinbakk, M.; Sunde, M. Livestock-associated MRSA CC1 in Norway; introduction to pig farms, zoonotic transmission, and eradication. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grøntvedt, C.A.; Elstrøm, P.; Stegger, M.; Skov, R.L.; Andersen, P.S.; Larssen, K.W.; Urdahl, A.M.; Angen, Ø.; Larsen, J.; Åmdal, S.; Løtvedt, S.M.; Sunde, M.; Bjørnholt, J.V. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC398 in humans and pigs in Norway: A “one health” perspective on introduction and transmission. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorado-García, A.; Graveland, H.; Bos, M.E.H.; Verstappen, K.M.; Van Cleef, B.A.G.L.; Kluytmans, J.A.J.W.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Heederik, D.J.J. (2015a). Effects of reducing antimicrobial use and applying a cleaning and disinfection program in veal calf farming: Experiences from an intervention study to control livestock-associated MRSA. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado-García, A.; Dohmen, W.; Bos, M.E.H.; Verstappen, K.M.; Houben, M.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Heederik, D.J.J. Dose-response relationship between antimicrobial drugs and livestock-associated MRSA in pig farming. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierikx, C.M.; Hengeveld, P.D.; Veldman, K.T.; de Haan, A.; van der Voorde, S.; Dop, P.Y.; Bosch, T.; van Duijkeren, E. Ten years later: still a high prevalence of MRSA in slaughter pigs despite a significant reduction in antimicrobial usage in pigs the Netherlands. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 2414–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, A.; Nielsen, S. S.; Guardabassi, L. Effects of tetracycline and zinc on selection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) sequence type 398 in pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 152, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).