1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal health in companion animals, particularly dogs, remains a critical concern for veterinarians and pet owners worldwide.

Salmonella spp. and

Escherichia coli (E. coli) are among the most significant bacterial pathogens affecting canine gut health, often causing severe gastroenteritis and systemic infections, posing risks of zoonotic transmission [

1]. Conventionally, these infections have been managed with antibiotics, but the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance has necessitated alternative therapeutic approaches. In response, the World Health Organization has advocated for restricted antibiotic use since 1997, recommending administration only in cases of definitive bacterial infections. Excessive antibiotic use not only eradicates pathogens but also disrupts beneficial gut microbiota, leading to dysbiosis and secondary health complications [

2]. Furthermore, the emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing

E. coli in dogs and cats highlights the urgent need for alternative infection management approaches that minimise antibiotic resistance risks [

3,

4].

Among these alternatives, probiotics have emerged as a promising strategy for maintaining gut health and preventing infections in dogs.

Lactobacillus species, in particular, enhance gut microbiota composition, support immune function, and inhibit pathogenic bacterial growth [

5]. A study shows that probiotic supplementation improves microbial diversity, increases beneficial bacteria, and suppresses pathogenic pathways, particularly in dogs with gastrointestinal disturbances such as diarrhoea [

6]. Additionally, probiotics mitigate antibiotic-induced dysbiosis, thereby preserving gut microbial homeostasis [

7]. Therefore, maintaining the gut microbiome using probiotics could provide significant benefits in managing gastrointestinal diseases and promoting overall canine health.

Beyond gastrointestinal health, probiotics offer potential benefits in systemic health conditions, such as chronic kidney disease, where they help maintain nutritional status and improve renal function parameters [

8]. The synergistic effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and antioxidants have been explored as therapeutic interventions for chronic diseases in dogs, further underscoring the broad applications of probiotics in veterinary medicine. The rising demand for effective, targeted probiotic formulations highlights the need for continued research into their specific mechanisms and benefits [

6]. However, conventional antibiotic therapy remains limited, and the growing demand for alternative treatments highlights the need for targeted probiotics, representing a critical advancement in veterinary medicine. The ability of

Lactobacillus strains to inhibit the growth of

Salmonella and

E. coli highlights their potential as effective probiotics for canine gastrointestinal health. Therefore, this study aims to identify and characterise

Lactobacillus strains with antimicrobial activity against key canine pathogens. A two-step screening process was employed: microbiome analysis in healthy puppies and adult dogs was conducted to isolate primary

Lactobacillus candidate strains; second, these strains were evaluated for their probiotic potential, focusing on their antimicrobial activity against

Salmonella and

E. coli.

Limosilactobacillus reuteri JJ37 and JJ69 were identified as the final probiotic candidate. These strains exhibited strong antibacterial activity against major pathogenic bacteria affecting dogs, positioning them as a promising candidate for probiotic development to enhance canine gut health and prevent gastrointestinal infections.

3. Results

3.1. DNA Quality and Purity Assessment of Gut Microbiota for Metagenomic Analysis

The quality of DNA was verified through spectrophotometry, gel electrophoresis, and PCR amplification. Quality control parameters, including sample concentrations, volumes, and DNA purity, were assessed based on the following criteria: a minimum concentration of 15 ng/μL, volume of at least 20 μL, and DNA purity ratio (A260/280) within the range of 1.8

–2.1. DNA purity was determined by calculating the absorbance ratio at 260 nm (indicative of DNA) to 280 nm (indicative of proteins). All samples (A2, A4, A10, B3, B5, and B7) met the quality control criteria and they were confirmed via PCR analysis (

Supplementary Table S2). The successful amplification of the target DNA in each sample was validated by observing the presence of distinct bands on the gel (

Supplementary Figure S1).

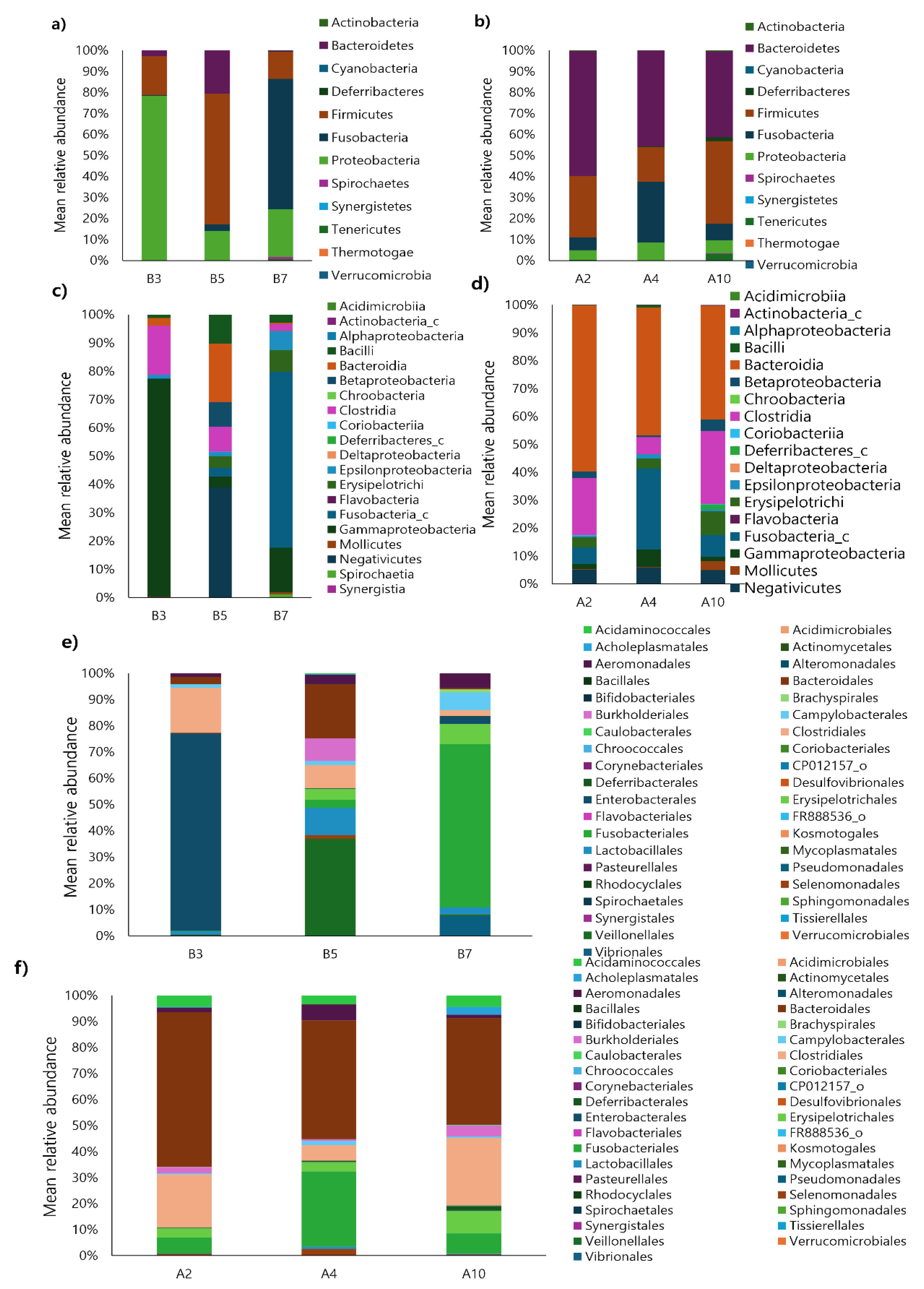

3.2. Metagenomic Analysis of the Gut Microbiota in Puppies and Adult Dogs

Figure 2 illustrates the comparison of the gut microbiota composition between healthy puppies and adult dogs. At the phylum level, puppy B3 showed the highest proportion of

Proteobacteria (78.18%), while puppy B5 was dominated by

Firmicutes (62.03%) and puppy B7 by

Fusobacteria (62.08%). No single dominant phylum was shared among the puppies. In contrast, adult dogs A2, A4, and A10 showed a consistent prevalence of

Bacteroidetes (> 40%) across all samples. Overall,

Proteobacteria,

Firmicutes,

Fusobacteria, and

Bacteriodetes were the dominant phyla (> 5%) in both puppies and adult dogs. However, no commonly dominant phylum was observed between the two groups.

At the class level, puppy B3 was dominated by Gammaproteobacteria (76.91%), followed by Clostridia (17.22%). Puppy B5 showed the highest proportion of Negativicutes (38.77%) and Bacteroidia (20.62%), while puppy B7 was primarily composed of Fusobacteria (62.09%), followed by Gammaproteobacteria (15.81%). The predominant classes (> 30%) in each puppy were Gammaproteobacteria, Negativicutes, and Fusobacteria, respectively, while no shared dominant class among the puppies. In adult dogs, A2 was the dominant class identified among the puppies. Moreover, A2 was dominated by Bacterodia (59.48%) and Clostridia (20.34%), A4 by Bacteroidia (45.61%) and Fusobacteria (28.88%), and A10 by Bacteroidia (40.9%) and Clostridia (25.97%). A consistent dominance of Bacteroidia (> 40%) was observed across all adult dogs, but no common dominant class was identified between puppies and adult dogs.

At the order level, puppy B3 had the highest proportion of Enterobacterales (75.33%), followed by Clostridiales (17.22%) and Bacterodiales (2.79%). Puppy B5 was primarily composed of Veillonellales (36.96%), followed by Bacteroidales (20.62%) and Lactobacillales (10.28%). Puppy B7 showed the highest abundance of Fusobacteriales (62.09%), followed by Pseudomonadale (7.54%) and Campylobacterales (6.66%). Each puppy was dominated by different orders—Enterobacterales, Veillonellales, and Fusobacteriales, respectively—with no shared dominant order observed. However, similar to the phylum and class levels, no common dominant order was identified between puppies and adult dogs.

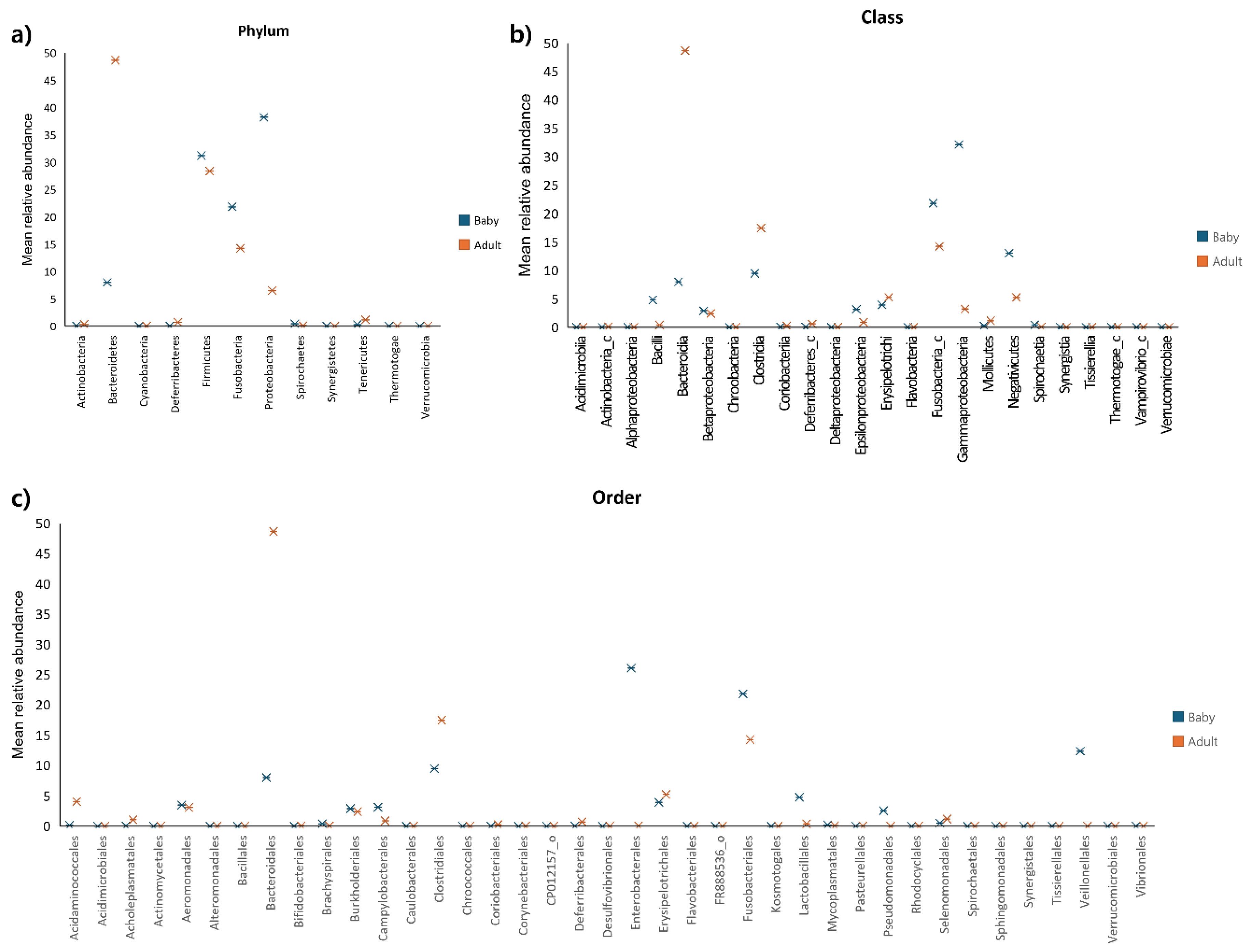

3.3. Differences in Gut Microbial Composition Between Puppies and Adult Dogs

The differences in gut microbiota composition between puppies and adult dogs were analysed by comparing correlations at the phylum, class, and order levels (

Figure 3). At the phylum level, puppies showed higher relative abundances of

Firmicutes,

Fusobacteria,

Proteobacteria,

Spirochaetes, and

Verrucomicrobia, while adult dogs had higher proportions of

Actinobacteria,

Bacteroidetes,

Cyanobacteria,

Deferribacteres,

Synergistetes,

Tenericutes, and

Thermotogae. The phyla with more than a 1.5-fold difference between the groups included

Bacteroidetes,

Fusobacteria, and

Proteobacteria.

Bacteroidetes accounted for 7.98% of the microbiota in puppies and 48.66% in adult dogs, representing an approximately 6-fold difference. The

Fusobacteria constituted 21.82% in puppies and 14.23% in adult dogs, a 1.53-fold difference.

Proteobacteria comprised 6.49% of puppies and 38.21% in adult dogs, showing a 5.88-fold difference. No other phyla exhibited differences exceeding 1.5-fold.

At the class level, puppies showed higher relative abundances of Acidimicrobiia, Alphaproteobacteria, Bacilli, Betaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria, Epsilonproteobacteria, Fusobacteria_C, Gammaproteobacteria, Negativicutes, Spirochaetia, and Verrucomicrobiae. In contrast, adult dogs had higher proportions of Actinobacteria_c, Bacterodia, Chroobacteria, Clostridia, Coriobacteriia, Deferribacters_c, Erysipelotrichi, Flavobacteria, Mollicutes, Synerfistia, Tissierellia, Thermotogae_c, and Vampirovibrio_c. Classes with differences (> 1.5 fold) between puppies and adult dogs included Bacilli, Bacterodia, Clostridia, Eplionproteobacteia, Fusobacteria_c, Gammaproteobacteria, and Negativicutes. For instance, Bacilli represented 4.79% of the microbiota in puppies and 0.39% in adult dogs (12.28-fold difference). Bacteroidia accounted for 7.89% in puppies and 48.66% in adult dogs (6.09-fold difference). Clostridia was present at 9.46% in puppies and 17.45% in adult dogs (1.84-fold difference). Epsilonproteobacteria accounted for 3.14% in puppies and 5.25% in adult dogs (1.67%-fold difference). Fusobacteria_c constituted 21.82% in puppies and 14.23% in adult dogs (1.53-fold difference). Gammaproteobacteria comprised 32.16% in puppies and 3.21% in adult dogs (10.01-fold difference). Negativicutes accounted for 13.01% in puppies and 5.24% in adult dogs (2.48-fold difference).

At the order level, puppies showed higher relative abundances of Aeromonadales, Alteromonadales, Bacillales, Brachyspirales, Burkholderiales, Campylobacterales, Caulobacterales, Enterobacterales, Fusobacteriales, Lactobacillales, Mycoplasmatales, Pseudomonadlaes, Spirochaetales, Sphingomonadales, Veillonellales, Verrucomicrobiales, and Vibrionales. In contrast, adult dogs exhibited higher proportion of Acidaminoccocales, Acidimicrobiales, Acholeplasmatales, Actinomycetales, Bacteroidales, Bifidobacteriales, Clostridiales, Chroococcales, Coriobacteriales, Corynebacteriales, Kosmotogales, Pasteurellales, Rhodocyclales, Selenomonadales, Synergistales, and Tissierellales. Orders with differences (> 1.5 fold) between puppies and adult dogs included Acidaminococcales, Bacteroidales, Clostridiales, Enterobacterales, Fusobacteriales, Lactobacillales, Pseudomonadales, and Veillonellales. For example, Acidaminococcales accounted for 0.15% of the microbiota in puppies and 4.05% in adult dogs (25.8-fold difference). Clostridiales was present at 9.46% in puppies and 17.45% in adult dogs (1.84-fold difference). Enterobacterales accounted for 26.06% in puppies and 14.23% in adult dogs (1.53-fold difference). Lactobacillales comprised 4.76% in puppies and 0.39% in adult dogs (12.24-fold difference). Pseudomonadales constituted 2.54% in puppies but were absent in adult dogs. Veillonellales accounted for 12.33% of puppies and 0.02% in adult dogs (456-fold difference). No other order exhibited a significant difference (>1.5 fold).

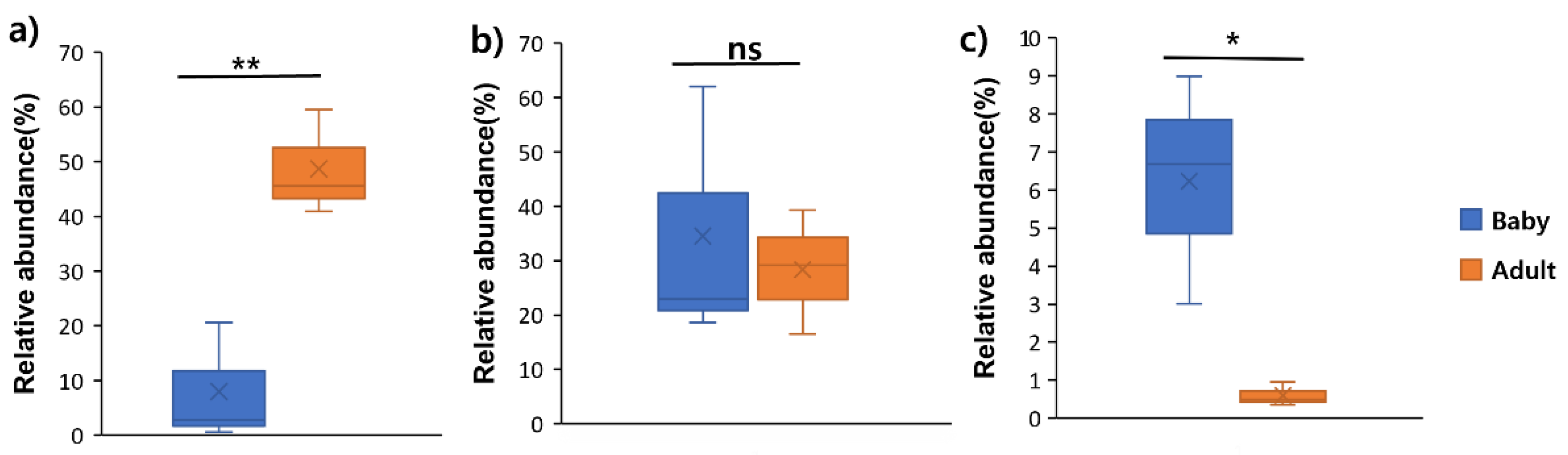

3.4. F/B Ratio in Adult Dogs and Puppies

To investigate the

Firmicutes/

Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio and its potential effect, the gut microbiota composition in adult dogs and puppies was analysed. Genomic DNA was extracted, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed to profile the gut microbiota. The relative abundances of

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidetes at the phylum level were compared. In puppies,

Firmicutes accounted for 34.54% on average (range: 18.66−62.03%), while in adult dogs, it was 28.35% on average (range: 16.48−39.35%. Conversely,

Bacteroidetes was significantly less abundant in puppies, with an average of 7.99% (range: 0.55−20.63%), compared to that in adult dogs, which exhibited an average of 48.66% (range: 40.9−59.48%). These findings indicate that puppies had a higher proportion of

Firmicutes and a lower proportion of

Bacteroidetes than those of adult dogs (

Figure 4). The F/B ratio was calculated as the relative abundance of

Firmicutes divided by that of

Bacteroidetes. The F/B ratio in puppies was 11.12 on average (range: 3.01−23.67), whereas in adult dogs, it was 0.6 (range: 0.36−23.67). This suggests that the F/B ratio is significantly higher in puppies than in adult dogs.

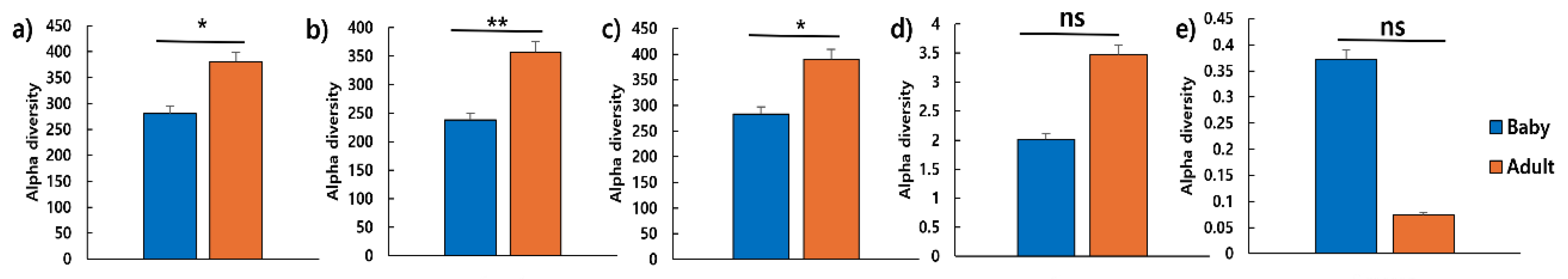

3.5. Differences in Gut Microbiota Diversity Between Puppies and Adult Dogs

In total, 263,479 V4 16S rRNA sequence reads were collected from six samples, with an average of 41,472 reads per sample. Species richness and diversity were assessed using ACE, Chao 1, Jackknife, Shannon, and Simpson indices. The ACE, Chao 1, and Jackknife indices were significantly higher in adult dogs than in puppies (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 5).

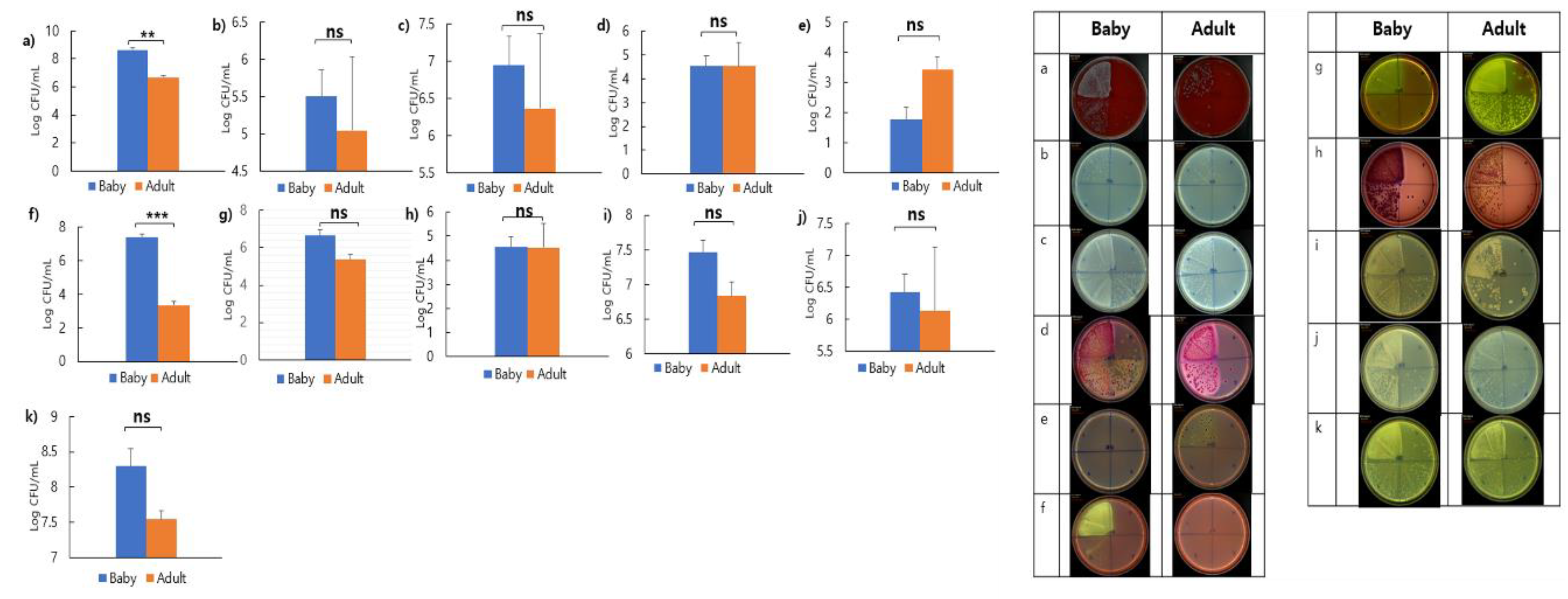

3.6. Comparison of Faecal Microbial Distribution Between Puppies and Adult Dogs

To compare the faecal microbial distribution between healthy puppies and adult dogs, colony counts were obtained via direct culture using selective media.

Figure 6 shows the microbial distribution of faecal samples from 10 puppies and 30 adult dogs on each medium. On blood agar, the colony count for puppies was 3.98 × 10

8 CFU/mL, while for adult dogs, it was 4.86 × 10

6 CFU/mL. This showed that puppies had 100 times more colonies than those of adult dogs (

Figure 6a). On TSN, the colony count was 3.19 × 10

5 CFU/mL for puppies and 1.1 × 10

5 CFU/mL for adult dogs. This showed that puppies had approximately 3.16 times more colonies than those of adult dogs (

Figure 6b). On PDA, puppies had 8.85 × 10

6 CFU/mL, and adult dogs had 2.34 × 10

6 CFU/mL, showing that puppies had 10 times more colonies than those of adult dogs (

Figure 6c). On MAC, both puppies and adult dogs had colony counts of 3.3 × 10

4 CFU/mL (

Figure 6d). On SS, puppies had 5.85 × 10

1CFU/mL and adult dogs had 2.71 × 10

3 CFU/mL, showing that adult dogs had 100 times more colonies than those of puppies (

Figure 6e). On MS, puppies had 2.48 × 10

7 CFU/mL, and adult dogs had 2.19 × 10

3 CFU/mL, confirming that puppies had 10,000 times more colonies than those of adult dogs (

Figure 6f). On BG, puppies had 4.46 × 10

6 CFU/mL, and adult dogs had 2.32 × 10

5 CFU/mL, showing that puppies had 10 times more colonies than that of adult dogs (

Figure 6g). On MACS, both puppies and adult dogs had colony counts of 3.4 × 10

4 CFU/mL (

Figure 6h). On MRS, colony counts were 2.87 × 10

7 CFU/mL for puppies and 6.84 × 10

6 CFU/mL for adult dogs (

Figure 6i). On TOS, puppies and adult dogs had 2.68 × 10

6CFU/mL and 1.71 × 10

6CFU/mL, respectively (

Figure 6j). On PCA, puppies had 1.98 × 10

8CFU/mL and adult dogs had 3.47 × 10

7 CFU/mL (

Figure 6k). Across PCA, MRS, and TOS media, puppies had approximately 3.16 times more colonies than those of adult dogs. No significant differences were observed between puppies and adult dogs in all media except for the MS medium.

3.7. Selection of Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains Through Multi-Step Screenings

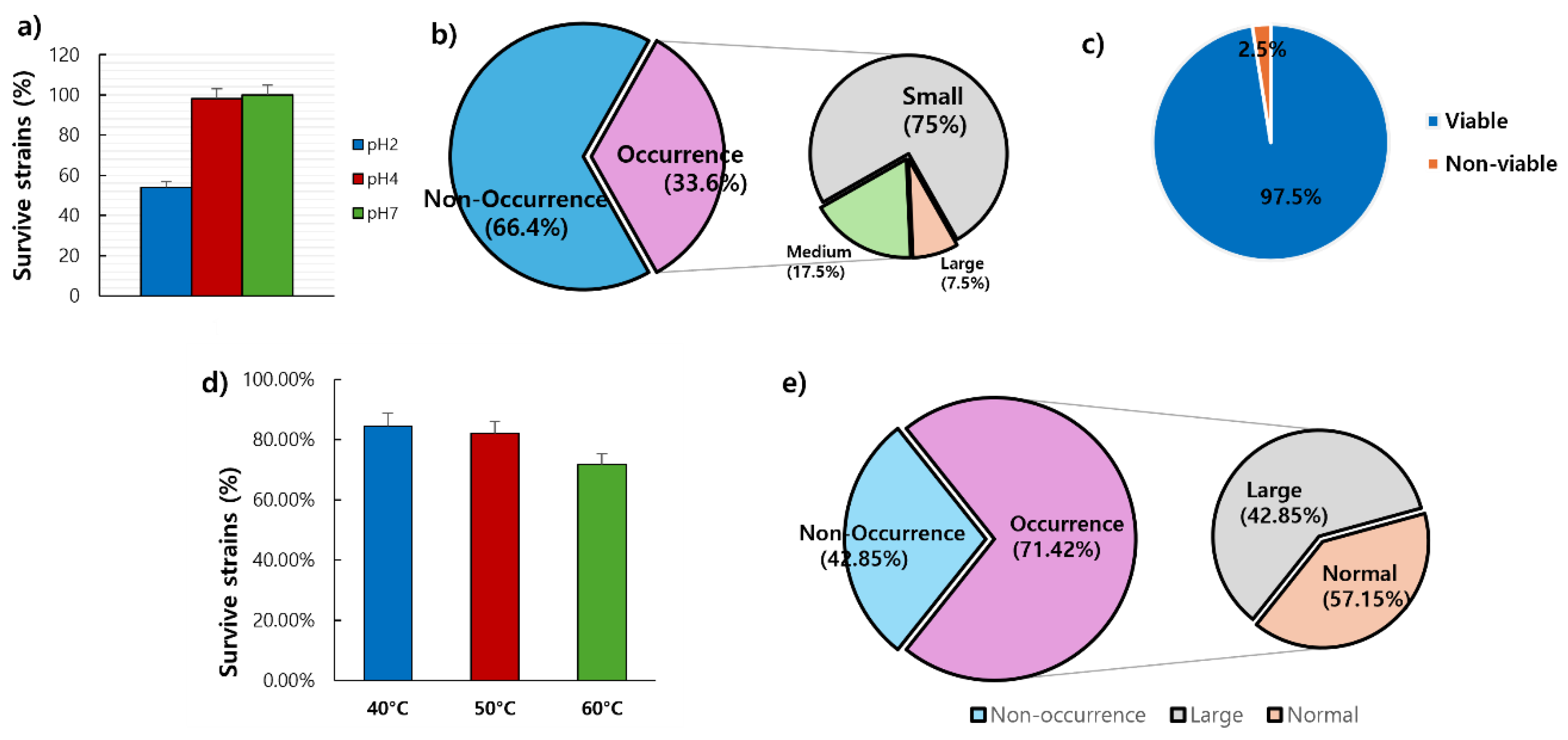

3.7.1. Acid Tolerance Test

Forty faecal samples from dogs were diluted 10-fold and spread on PCA with BCP agar to select 109 lactic acid-producing strains. To identify strains with high probiotic potential, an acid tolerance test was performed. The survival rates at pH 2 and pH 4 were measured (

Table 1 and

Figure 7a). At pH 2, 57 out of 109 strains (52.3%) survived, while at pH 4, 107 out of 109 strains (98.17%) survived. The control strain,

L. acidophilus KCTC 3111, survived at both pH levels, confirming its acid tolerance.

3.7.2. Lactic Acid Production Test

A test was performed to isolate lactic acid-producing strains. Among the 119 strains, 40 (33.61%) produced lactic acid, while 79 (66.39%) did not (

Table 1 and

Figure 7b). The lactic acid-producing strains were categorised by colony size: small, medium, or large. Among the 40 strains, 30 produced the smallest colonies, 7 produced medium-sized colonies, and 3 produced the largest colonies. The control strain,

L. acidophilus KCTC 3111, produced medium-sized colonies and was identified as a lactic acid-producing strain.

3.7.3. Bile Tolerance Test

To identify bile-tolerant strains, a bile tolerance test was conducted on the 40 strains that had previously demonstrated acid resistance and lactic acid production. All strains, except for one, grew on plates containing 1% Oxgall (Difco

TM Oxgall, BD) (

Table 1 and

Figure 7c). The control strain,

L. acidophilus KCTC3111, also grew on MRS agar plates, confirming its bile tolerance.

3.7.4. Heat Resistance Test

A heat resistance test was conducted on 39 strains that exhibited acid tolerance, lactic acid production, and bile tolerance (

Table 1 and

Figure 7d). Among these, 33 (84.61%), 32 (82.05%), and 28 strains (71.79%) survived at 40°C, 50°C, and 60°C, respectively. The control strain,

L. acidophilus KCTC 3111, also survived at all three temperatures, confirming its heat resistance.

3.7.5. Dietary Enzyme of Protease

A protease activity test was conducted on 28 strains that exhibited acid tolerance, lactic acid production, bile tolerance, and heat resistance. The experiment aimed to identify strains capable of producing the digestive enzyme protease (

Table 1 and

Figure 7e). Among these 28 strains, 20 (71.43%) formed clear zones around their colonies, indicating protease production, while 8 strains (28.57%) did not. Among the 20 protease-producing strains, 12 (60%) produced large clear zones, indicating strong protease activity.

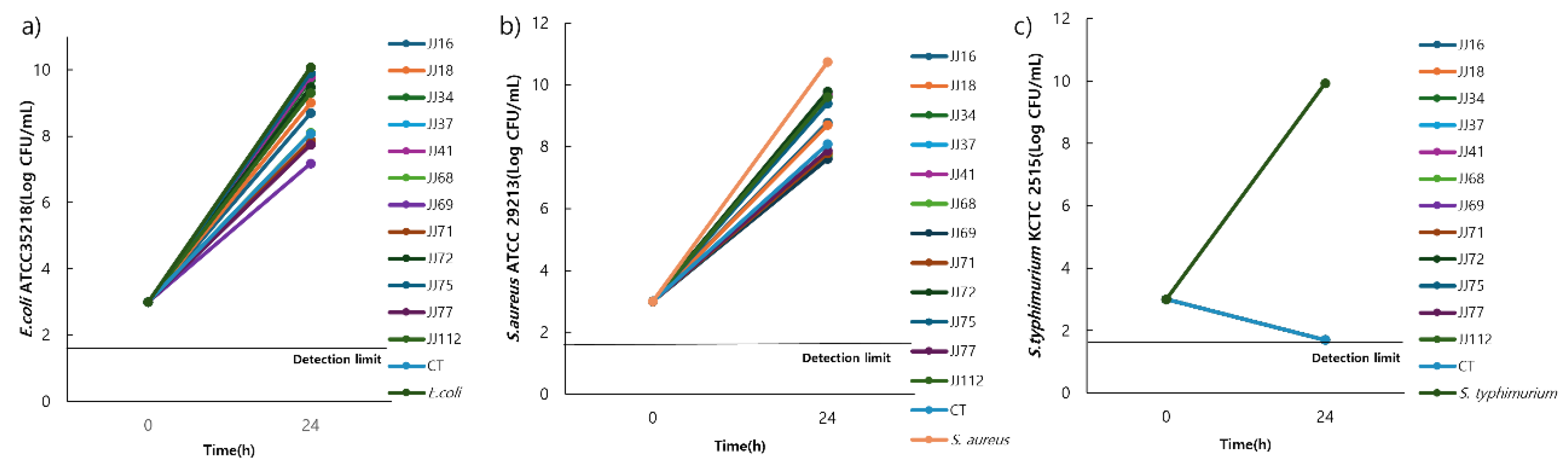

3.8. Identification of Candidate Probiotic Strains

In total, 109 candidate strains (JJ001−JJ109) were isolated from 40 canine faecal samples. Among these, 12 strains were selected for phenotypic characterisation (

Table 2). All strains were Gram-positive, rod-shaped, and catalase-negative. To identify final probiotic candidates, an antibacterial activity test was conducted on the 12 selected strains (

Figure 8). After co-culturing the candidate strains with three pathogenic bacteria—

E. coli ATCC 35218,

S. aureus ATCC 29213, and

S. typhimurium—KCTC 2515 for 24 h. The results showed that five strains (JJ37, JJ68, JJ69, JJ71, and JJ77) exhibited bacterial counts below 10

8 CFU/mL against

E. coli and

S. aureus. The control strain,

L. reuteri KCTC3594, had a bacterial count of 10

8 CFU/ mL against the pathogenic strains, while the remaining strains exceeded 10

8 CFU/mL. Against

S. typhimurium, all strains inhibited bacterial growth to below 10

1 CFU/mL. Based on their antibacterial activity after 24 h of co-culture, the five strains (JJ37, JJ68, JJ69, JJ71, and JJ77) were identified as probiotic candidates.

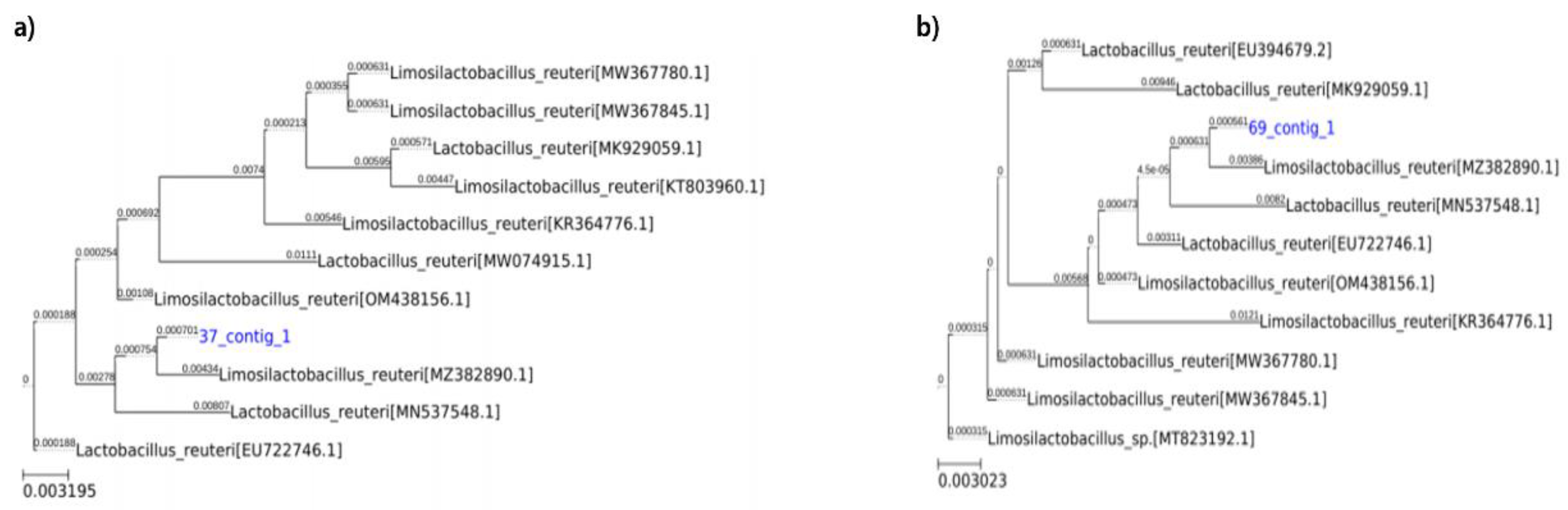

3.9. Identification of L. reuteri JJ 37, 68, 69, 71, and 77

The five selected strains were identified as

L. reuteri JJ37, JJ68, JJ69, JJ71, and JJ77.

Supplementary Figure S2 shows the 16S rRNA gene sequences

L. reuteri JJ37 and JJ69. Microgen analysis confirmed that these strains belonged to

L. reuteri with over 99.9% similarity (

Figure 9).

4. Discussion

In this study, the gut microbiota of healthy puppies and adult dogs were analysed. Cultured microorganisms were then compared to identify and select Lactobacillus strains with probiotic potential. Faecal samples were collected from 40 companion dogs, with only one exhibiting signs of illness. Overall, clinical symptoms in both puppies and adult dogs were generally stable. The puppies weighed less than 2 kg (≤ 2 months old), while the adult dogs had a weight range of 2–7 kg (≥ 2 months old). Haematochezia was observed in one adult dog, but overall health remained stable. This study highlights the differences in gut microbiota composition between puppies and adult dogs and evaluates the potential for selecting Lactobacillus strains with antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria. This analysis is significant as it improves our understanding of gut microbiota changes related to age, weight, and health status. It can serve as foundational data for developing targeted probiotics for companion dogs.

In the phylum classification, no bacterial taxa were consistently abundant among puppies. However, in adult dogs,

Bacteroides was the most prevalent taxon. The gut microbiota comprises over 1,000 bacterial species, with

Bacteroidetes and

Firmicutes being the dominant phyla. In this analysis of three adult dogs and three puppies, the predominant bacterial taxa were

Proteobacteria,

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidetes, and

Fusobacteria. You and Kim et al. [

11] examined the gut microbiota composition of 96 healthy dogs. Their phylum classification identifies

Proteobacteria,

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidetes, and

Fusobacteria as the predominant taxa, indicating that the results are statistically significant.

At the class level, no bacterial taxa were commonly abundant in puppies and adult dogs. Additionally, no bacterial taxa were consistently distributed among puppies. However, in adult dogs,

Bacteroidia was the most abundant taxon, with dominant taxa including

Bacteroidales,

Fusobacteria_C, and

Clostridia. In the phylum classification, no common taxa were observed in puppies, while adult dogs exhibited significant similarities. The bacterial taxa present in puppies included

Enterobacterales,

Veillonellales, and

Fusobacteriales, but no single taxon was consistently abundant. In contrast,

Bacteroidales was the most prevalent bacterial taxon in adult dogs. Puppies showed considerable variability in gut microbiota composition, whereas adult dogs maintained a more stable microbial composition across the phylum, class, and order levels. The gut microbiota composition of adult dogs aligns closely with findings from a previous study[

11], reinforcing the consistency of these findings with other research.

This study was conducted to examine the changes in faecal microbiota composition over time across different growth stages in dogs. In this research, dogs younger than 2 months and those older than 12 months were categorised into two groups to observe variations in faecal microbiota. Previous studies confirm the faecal microbiota composition in both puppies and adult dogs. At the phylum level, bacterial taxa exhibited a significant difference of more than 1.5 fold (>1.5%), including

Bacteroidetes,

Fusobacteria, and

Proteobacteria. At the class level, the identified taxa were

Bacilli,

Bacteroidia,

Clostridia,

Epsilonproteobacteria,

Fusobacteria_C,

Gammaproteobacteria, and

Negativicutes. The order level classification included

Acidaminococcales,

Bacteroidales,

Clostridiales,

Enterobacterales,

Fusobacteriales,

Lactobacillales,

Pseudomonadales, and

Veillonellales. Significant differences in microbial diversity and abundance were observed between pre-weaning and post-weaning stages, as well as among puppies, adult dogs, and elderly dogs [

12,

13]. Previous studies show that faecal microbial composition changes with developmental stages in both humans and pigs. In humans, the faecal microbiota of infants becomes similar to that of adults once they transition to an adult-like diet, indicating that microbial communities are influenced by diet and environmental factors [

14]. In pigs, the microbial population increases until approximately 20 weeks after birth, after which no major changes are observed [

12].

In puppies, the microbial composition is predominantly characterised by

Lactobacillales, while adult dogs exhibit a predominance of

Bacteroidetes. The genus

Lactobacillus, a lactic acid bacterium, is more prevalent in puppies. It plays a crucial role in lactose digestion during the milk consumption phase [

15]. However, following weaning and dietary transition over the first year, its relative abundance decreases, as indicated by taxonomic classification. In contrast, adult dogs show a higher abundance of

Bacteroidetes, a dominant bacterial group in the gastrointestinal tracts of animals and are primarily involved in polysaccharide metabolism [

16]. These findings suggest that as dogs mature, their carbohydrate intake increases, leading to a proportional rise in

Bacteroidetes abundance.

The gut microbiota maintains a stable community by balancing beneficial and harmful bacteria. Beneficial bacteria stimulate the immune function of the host and prevent various bacterial infections, while harmful bacteria induce putrefaction and produce carcinogens or toxins. For optimal gut health, beneficial bacteria must predominate [

17]. Within the biological classification system,

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidetes are the primary constituents of the bacterial species present. A previous study shows that probiotic supplementation improves health status, resulting in a decrease in

Firmicutes from 46–31% and an

increase in

Bacteroidetes from 22–28% [

18]. These findings suggest that improved health is associated with higher

Bacteroidetes and lower

Firmicutes.

An analysis of the gut microbiota composition in puppies and adult dogs reveals that puppies have a lower relative abundance of

Bacteroidetes and a higher relative abundance of

Firmicutes than that of adult dogs. This suggests that adult dogs have a more balanced gut microbiome. The proportional changes in

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidetes, along with the F/B ratio, serve as indicators of gut microbial health [

19]. The lower F/B ratio observed in adult dogs indicates that they maintain a more stable gut microbiota.

Blood agar was utilised to isolate a broad spectrum of pathogens that are challenging to culture and to evaluate the haemolytic activity of isolates [

20]. Haemolytic activity was detected in only two adult dogs, with no haemolytic isolates identified in other samples. TSN agar was employed to culture and isolate

Clostridium perfringens [

21]. This bacterium secretes toxins and enzymes responsible for various gastrointestinal diseases, including food poisoning, non-food borne diarrhoea, and enteritis in humans and animals [

22]. PDA was used for the cultivation of fungi and moulds [

23]. MC facilitated the isolation and differentiation of pathogenic enteric bacteria. SS agar was employed to selectively isolate and differentiate

Salmonella and

Shigella. MS agar enables the selective cultivation and isolation of

S. aureus. BG agar was used for the selective isolation of

Salmonella spp., excluding

S. typhimurium. Additionally, MACS was specifically used to culture enterohaemorrhagic

E. coli. MRS agar supported the isolation of

Lactobacillus spp., while TOS selectively promoted the growth of

Bifidobacterium spp. by inhibiting

Lactobacillus growth. PCA was employed to quantify LAB. PCA, MRS, and TOS, which are associated with LAB, exhibited higher microbial counts in puppies. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between puppies and adult dogs in any medium except MS agar. This finding aligns with that of previous research, which reports no significant differences in faecal microbial community distribution patterns between puppies and adult dogs across various media types [

24].

LAB must survive passage through the stomach, where the pH is ≤ 3, and reach the small intestine to exert their physiological functions [

25]. A previous study reports a 40.6% survival was observed when 101 candidate LAB strains isolated from dogs were cultured at pH 2.5 for 3 h [

26]. In the present study, survival was 51.4% when cultured at pH 2 for 1.5 h. Although this difference was not statistically significant, the survival rate consistently remained approximately 50%.

LAB naturally produce lactic acid [

27], which exerts bactericidal effects against susceptible bacteria, thus inhibiting harmful gut microorganisms [

28]. Therefore, acid-producing strains are expected to have a positive effect.

To reach the intestine, ingested LAB must pass through the stomach, pancreas, and duodenum. Bile tolerance in these areas is a critical characteristic [

29]. In this study, when cultured for 2 days in media with 1% bile, all strains, except for one, survived. Similarly, a previous study reports a 99% survival rate when LAB was cultured for 2 h in media with 1% bile, with only one strain failing to survive[

26], which aligns with our findings.

Probiotics are typically administered directly or mixed with feed in the form of powder, pellets, granules, pills, or paste. This processing usually involves heat treatment at temperatures ranging from 50

–80°C [

30]. A previous study shows that probiotic strains isolated from dogs exhibit a 92.5% survival rate after being cultured at 50°C for 5 min, while survival decreases to 80% when cultured at 60°C for 5 min [

26]. In the present study, the survival rate was 71.8% when cultured at 50°C for 1 h, and the same survival rate was observed at 60°C for 1 h. The lower survival rate in this study is attributed to the extended culturing time compared to that of the previous study.

Probiotics have a positive effect on protein digestion, influencing digestion and nutrient absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. They induce the activity of digestive proteolytic enzymes and peptidases in the host, and some strains also release enzymes involved in protein breakdown [

31]. A previous study characterised LAB strains selected for probiotic use, identifying them as Gram-positive properties, catalase-negative, non-motile, non-spore-forming, and rod-shaped

bacilli [

32]. The findings of this present study are similar to those of the previous research, supporting the assessment of candidate probiotic strains. LAB produce lactic acid as a metabolic by-product, lowering pH [

33], which effectively inhibits the growth of pathogenic bacteria through various antimicrobial mechanisms [

34]. Although studies show that increasing LAB populations reduce the growth of pathogenic bacteria such as

S. aureus,

E. coli, and

Salmonella, research on their specific effects remains limited [

35].

With the increase in pet ownership in Korea, pets have become integral family members, raising concerns about health issues, particularly the transmission of infectious diseases between pets and their owners. As of 2023, the number of pet-owning households in Korea has increased approximately 2.8 times compared to that of 2020, with dogs comprising 75.6% of the total pet population [

36]. However, the shared living environment between pets and humans increases the risk of the transmission of infectious diseases such as pathogenic bacteria. A representative zoonotic disease is ringworm, a fungal infection [

37] that spreads from pets to humans through direct contact with fur or skin, posing a higher risk to vulnerable groups such as the elderly and children. Additionally,

Salmonella can be transmitted through pet faeces, causing severe gastroenteritis and, in some cases, septicemia [

38].

Salmonella infection is a significant public health issue, posing a direct risk to both pet and human health. Moreover,

E. coli infection is another concern, as pathogenic

E. coli from pets can be transmitted to humans, causing symptoms such as gastroenteritis, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea [

39]. The emergence of antibiotic-resistant

E. coli strains exacerbates treatment difficulties and is recognised as a critical public health concern. Other bacterial infections, such as

campylobacteriosis, can also spread between pets and humans, typically causing diarrhoea, fever, and abdominal pain, resulting in severe complications in immunocompromised individuals [

40]. To address the issue of infectious disease transmissions between pets and their owners, probiotics have gained attention as a potential alternative to antibiotics.

L. reuteri is a well-studied lactic acid bacterium with demonstrated antimicrobial activity, especially in inhibiting

Salmonella and

E. coli [

41].

Figure 1.

Process of the experiment for probiotic candidate selection. Abbreviation: LAB, lactic acid bacteria.

Figure 1.

Process of the experiment for probiotic candidate selection. Abbreviation: LAB, lactic acid bacteria.

Figure 2.

Taxonomic classification of 40 faecal samples from healthy dogs, including adult dogs and puppies. (a−b) phylum level, (c−d) class level, and (e−f) order level.

Figure 2.

Taxonomic classification of 40 faecal samples from healthy dogs, including adult dogs and puppies. (a−b) phylum level, (c−d) class level, and (e−f) order level.

Figure 3.

Correlation between bacterial taxa and age group (adult dogs vs. puppies) at the phylum level (a), class level (b), and order level (c).

Figure 3.

Correlation between bacterial taxa and age group (adult dogs vs. puppies) at the phylum level (a), class level (b), and order level (c).

Figure 4.

Variability in the F/B ratio (a) and the relative abundances of Firmicutes (b) and Bacteroidetes (c) in the gut microbiota of adult dogs and puppies. Box plots were constructed using R.*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Abbreviation: F/B, Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes; ns, non-significant.

Figure 4.

Variability in the F/B ratio (a) and the relative abundances of Firmicutes (b) and Bacteroidetes (c) in the gut microbiota of adult dogs and puppies. Box plots were constructed using R.*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Abbreviation: F/B, Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes; ns, non-significant.

Figure 5.

Differences in alpha diversity between puppies (n = 3) and adult dogs (n = 3). Species richness reflected via a) ACE, b) Chao1, c) Jackknife, d) Shannon, and e) Simpson indices. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Abbreviation: ns, non-significant.

Figure 5.

Differences in alpha diversity between puppies (n = 3) and adult dogs (n = 3). Species richness reflected via a) ACE, b) Chao1, c) Jackknife, d) Shannon, and e) Simpson indices. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Abbreviation: ns, non-significant.

Figure 6.

Diversity and strain-specific characteristics of gut microbiota, as revealed by culturing faecal samples on various media. Bacterial colony counts on a) Blood agar, b) TSN, c) PDA, d) MC, e) SS, f) MS, g) BG, h) MACS, i) MRS, j) TOS, and k) PCA with BCP media of adult dogs and puppies. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: TSN, tryptone sulfite neomycin; PDA, potato dextrose agar; MC, MacConkey; SS, salmonella-shigella; MS, mannitol salt; BG, brilliant green; MACS, MacConkey sorbitol; MRS, De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe; TOS, transgalactosylated oligosaccharides with MUP; PCA, plate count agar; BCP, bromocresol purple; ns, non-significant.

Figure 6.

Diversity and strain-specific characteristics of gut microbiota, as revealed by culturing faecal samples on various media. Bacterial colony counts on a) Blood agar, b) TSN, c) PDA, d) MC, e) SS, f) MS, g) BG, h) MACS, i) MRS, j) TOS, and k) PCA with BCP media of adult dogs and puppies. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: TSN, tryptone sulfite neomycin; PDA, potato dextrose agar; MC, MacConkey; SS, salmonella-shigella; MS, mannitol salt; BG, brilliant green; MACS, MacConkey sorbitol; MRS, De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe; TOS, transgalactosylated oligosaccharides with MUP; PCA, plate count agar; BCP, bromocresol purple; ns, non-significant.

Figure 7.

Probiotic characteristics of selected LAB from the faeces of dogs a) Acid tolerance, b) Lactic acid production, c) Bile resistance, d) Heat resistance, and e) Dietary enzyme of protease. Abbreviation: LAB, lactic acid bacteria.

Figure 7.

Probiotic characteristics of selected LAB from the faeces of dogs a) Acid tolerance, b) Lactic acid production, c) Bile resistance, d) Heat resistance, and e) Dietary enzyme of protease. Abbreviation: LAB, lactic acid bacteria.

Figure 8.

Co-culture of Lactobacillus with enterotoxigenic pathogen a) E. coli ATCC 35218, b) S. aureus ATCC 29213, and c) Salmonella typhimurium KCTC 2515. The CFU of enterotoxigenic pathogens at 103 CFU/mL after co-culture with Lactobacillus (109 CFU/mL) for 24 h. Abbreviations: E. coli, Escherichia coli; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; CFU, colony-forming units; CT, control.

Figure 8.

Co-culture of Lactobacillus with enterotoxigenic pathogen a) E. coli ATCC 35218, b) S. aureus ATCC 29213, and c) Salmonella typhimurium KCTC 2515. The CFU of enterotoxigenic pathogens at 103 CFU/mL after co-culture with Lactobacillus (109 CFU/mL) for 24 h. Abbreviations: E. coli, Escherichia coli; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; CFU, colony-forming units; CT, control.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of L. reuteri strain a) L. reuteri JJ 37 and b) L. reuteri JJ 69 Abbreviation: L. reuteri, Lactobacillus reuteri.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of L. reuteri strain a) L. reuteri JJ 37 and b) L. reuteri JJ 69 Abbreviation: L. reuteri, Lactobacillus reuteri.

Table 1.

Probiotic characteristics of selected lactic acid bacteria from the faeces of dogs.

Table 1.

Probiotic characteristics of selected lactic acid bacteria from the faeces of dogs.

| Characteristics |

|

Number of isolates (%) |

| Acid tolerance |

pH 2, 1.5 h |

59/109 (51.4) |

| pH 4, 1.5 h |

107/109 (98.17) |

| pH 7, 1.5 h |

109/109 (100.0) |

| Lactic acid production |

+ |

30/119 (25.21) |

| ++ |

7/119 (5.88) |

| +++ |

3/119 (2.52) |

| Bile tolerance |

1.0% Oxgall, 48 h |

39/40 (97.5) |

| Heat resistance |

40°C, 1 h |

33/39 (84.61) |

| 50°C, 1 h |

32/39 (82.05) |

| 60°C, 1 h |

28/39 (71.79) |

| Dietary enzyme of protease |

+ |

8/28 (28.57) |

| ++ |

12/28 (60.0) |

Table 2.

Characterisation of lactobacilli isolated from dog faeces.

Table 2.

Characterisation of lactobacilli isolated from dog faeces.

| Isolates |

Gram staining |

Cell morphology |

Catalase |

Antibacterial activity |

| JJ16 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+ |

| JJ18 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+ |

| JJ34 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+ |

| JJ37 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+++ |

| JJ41 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+ |

| JJ68 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+++ |

| JJ69 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+++ |

| JJ71 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+++ |

| JJ72 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+ |

| JJ75 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+ |

| JJ77 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+++ |

| JJ112 |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+ |

| CT |

+ |

Rod |

− |

+ |