Introduction

There is a growing demand for safe foods that contribute to well-being and promote longevity. Among these, probiotic dairy products are highly sought after due to the health benefits associated with probiotic bacteria [

1]. Several strains of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) are commonly used as probiotics, with the most extensively studied strains belonging to the genera

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium. Other genera, including

Streptococcus,

Lactococcus, and

Enterococcus, are also recognized for their health-promoting properties and are considered valuable probiotics.[

2]

Studies on the beneficial properties of probiotics have demonstrated that certain strains can serve as alternatives to antibiotic therapy. These probiotics can be administered to prevent infectious diseases, enhance the barrier function of the gut microflora, and provide non-specific immune system support. This is particularly important, as antibiotic treatments can disrupt the balance of the resident gut flora and act as immunosuppressors [

3]. To achieve the desired health benefits, probiotics must successfully colonize, adhere to, and remain viable and active in different parts of the intestines [

4]. These strains must survive the harsh conditions of the stomach and small intestine in order to reach the colonization site. In particular, they must overcome biological barriers such as stomach acid and bile in the intestines [

5].

Bioprospecting for efficient probiotic strains from various ecological niches, especially those that are poorly explored, is an exciting area of research, given the considerable diversity among probiotics [

6]. One such niche is camel milk, which holds potential as a source of probiotic LAB strains that have yet to be fully characterized. Existing literature indicates that, like other types of milk, camel milk contains LAB strains, predominantly Lactobacilli, Lactococci, and Enterococci [

7]. However, the unique composition of camel milk, when compared to cow milk [

8], along with its origins in arid environments with minimal anthropogenic influence, could result in significant differences in its microbial ecosystem and the biological properties of its microbiota. Numerous studies have demonstrated the therapeutic benefits of camel milk for various diseases, including food allergies and diabetes [

9]. Furthermore, camel milk contains antimicrobial agents [

10]. Al-Otaibi et al. [

11] reported that camel milk is a natural source of probiotics, showing that LAB strains isolated from camel milk could prevent the adhesion of

Staphylococcus aureus and inhibit

Escherichia coli in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [

12]. However, research on the probiotic properties of LAB strains isolated from camel milk remains limited. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to isolate LAB from camel milk and assess their probiotic potential.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Culture of Bacterial Strains

LAB strains were isolated from camel milk (Camelus dromedarius) sourced from the herd at the Arid Lands Institute (IRA), Medenine, Tunisia. Milk samples were collected from the camel flock at the Arid Lands Institute, Medenine, Tunisia. The LAB were cultured on MRS (Pronadisa, Madrid, Spain) agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 hours to perform conventional tests for identification and probiotic screening. The strains were tested for Gram staining, catalase activity, and motility.

Gram-positive, catalase-negative, and non-motile isolates were selected and stored in MRS broth supplemented with 30% sterile glycerol as a cryoprotectant at -80°C. Prior to analysis, the purified cultures were revived by sub-culturing twice in MRS broth.

Molecular Identification Using 16S rRNA Gene

Genomic DNA of the strains was extracted using a DNA extraction and purification kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Fermentas, Cambridge, UK). The PCR reaction mixture contained 0.5 μL of template DNA, 2.5 μL of reverse primer (10 mM), 2.5 μL of forward primer (10 mM), 2 μL of dNTP (25 mM), 4 μL of MgCl₂ (25 mM), 5 μL of PCR buffer (10X), and 1 μL of Taq polymerase, making a final volume of 50 μL. The primers used were S1 (5’ AGAGTTTGATC(A,C)TGGCTCAG 3’) and S2 (5’ GG(A,C)TACCTTGTTACGA(T,C)TTC 3’).

The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation step at 94ºC for 3 minutes, followed by 29 cycles of 94ºC for 40 seconds, 55ºC for 50 seconds, and 72ºC for 2 minutes. The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the 1500 bp bands were purified. The resulting amplicons were then cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega Corp., France), followed by plasmid extraction using the GeneJET Plasmid Mini Prep (Thermo Scientific, Surrey, UK). Sequencing of the amplicons was performed by the sequencing facility at Eurofins (Ebersberg, Germany).

The obtained nucleotide sequences were analyzed using BioEdit software and compared against sequences in the NCBI database using the BLAST tool (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to determine identity percentages.

Assessment of Probiotic Potential

Tolerance to pH and Bile Salts

The isolated LAB strains were evaluated for their ability to withstand low pH and bile salts. A pH of 2, representative of gastric conditions, was used in the experiment. After 16 to 18 hours of culture under aerobic conditions, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The resulting pellets were washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then resuspended in PBS at pH 2 and incubated at 37°C. After 4 hours of incubation, colonies were counted, and the number of LAB was calculated following the standard ISO 15214 (1998). The survival rate was determined by comparing the number of LAB colonies grown on MRS agar after 4 hours of incubation to the initial number of LAB colonies.

Strains that showed resistance to low pH were subsequently tested for bile tolerance. Considering that the average intestinal bile concentration is approximately 0.3% (w/v) and food typically stays in the small intestine for about 4 hours [

20], the experiment was conducted at this concentration of bile for 4 hours. MRS medium containing 0.3% bile (Oxoid) was inoculated with active cultures (incubated for 16-18 hours). During the 4-hour incubation, viable cells were enumerated every hour using the pour plate technique, and growth was monitored by measuring the optical density (OD600).

Lactococcus lactis, a non-probiotic strain, was used as a negative control.

Assessment of Adhesion Properties

Adhesion to Hydrocarbons

The bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbons test (BATH) was conducted following the methods of Collado et al. [

13] and Kos et al. [

14]. Cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) and resuspended in the same buffer to an optical density (OD600) of approximately 0.25 ± 0.05 (OD₀) to standardize the bacterial concentration (10⁷–10⁸ CFU/mL). An equal volume of solvent was then added. The two-phase system was mixed vigorously for 5 minutes. After 1 hour of incubation at room temperature, the aqueous phase was separated, and its optical density at 600 nm (OD₁) was measured. The percentage of bacterial adhesion to the solvent was calculated using the following formula:

Two solvents were tested in this study: chloroform, a monopolar and acidic solvent, and ethyl acetate, a monopolar and basic solvent.

Bacterial Adhesion to Gastric Mucin

Enterococci strains were evaluated for their ability to adhere to immobilized porcine gastric mucin (Type III, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 96-well polystyrene microplates (Nunc Maxisorp, Denmark). Each well was coated with 100 µL of porcine gastric mucin solution (10 mg/mL) in sterile PBS (pH 7) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The wells were then washed twice with 200 µL of sterile PBS to remove any unbound mucin. To block non-specific binding sites, 200 µL of bovine serum albumin solution (2% w/v in PBS) was added, and the microplates were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Following this, the wells were washed twice with 200 µL of sterile PBS.

Bacterial cells were harvested at three different growth stages (9, 12, and 24 hours) by centrifugation at 3500 g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The pellets were washed twice with 1 mL of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and then centrifuged again. The cells were resuspended in PBS and diluted to achieve an optical density (OD600) of 0.1 ± 0.02, corresponding to approximately 3 × 10⁷ CFU/mL. A 100 µL aliquot of each bacterial suspension was added to the wells, and the microplates were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. After incubation, the liquid was removed by pipetting, and each well was washed five times with 200 µL of PBS.

To desorb the adhered cells, 200 µL of 0.5% Triton X-100 solution (v/v) was added for 20 minutes at room temperature, with orbital stirring at 150 rpm. The number of desorbed bacteria was determined by plating the solution onto MRS agar plates. All adhesion tests were performed in triplicate.

Adhesion to Intestinal Cell Line (STC-1)

Adhesion to the mouse intestinal endocrine tumor cell line (STC-1) was assessed. STC-1 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle’s Minimal Essential Medium), supplemented with 10% (v/v) calf serum, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 IU/mL penicillin (Gibco), and maintained at 37°C in a 95% air / 5% CO₂ atmosphere. The medium was replaced every 2 days, and the cells were used after reaching full confluence on day 15.

For the adhesion assay, cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 10⁴ cells per well in 24-well plates and incubated at 37°C until a confluent monolayer was formed. Prior to bacterial inoculation, the wells were washed with pre-warmed medium to remove any antibiotics. Bacteria were grown in MRS medium for 18 hours at 37°C and then washed twice in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The bacterial suspension was diluted in DMEM to obtain a final concentration of 1 × 10⁷ CFU/mL. One mL of the bacterial suspension was added to each well.

After a 2-hour incubation, free bacteria were removed by washing with 1 mL of pre-warmed phosphate buffer. To detach the adherent bacteria, 1 mL of 1% Triton X-100 was added, and after 10 minutes of incubation, serial dilutions of the solution were plated onto MRS agar. Plates were incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. This test was performed in triplicate.

Auto-Aggregation Test

Auto-aggregation assays were performed following the method described by Del Re et al. [

15], with some modifications. LAB strains were cultured in MRS broth for 18 hours at 37°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 g for 15 minutes, washed twice, and then resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to achieve a viable count of approximately 10⁸ CFU/mL. Cell suspensions (4 mL) were mixed by vortexing for 10 seconds.

After an incubation period of 4 hours at 37°C, 0.1 mL of the upper suspension was transferred to a new tube containing 3.9 mL of PBS. The optical density (OD) was measured at 600 nm. The auto-aggregation rate was calculated using the following formula:

Co-aggregation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Co-aggregation tests were performed following the method described by Collado et al. [

13]. Briefly, bacterial suspensions were prepared as described for the auto-aggregation assays. Equal volumes (100 µL each) of bacterial suspensions from different

Enterococcus strains and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (grown in Sabouraud Dextrose Broth, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, for 24 hours) were mixed and incubated at 20°C and 37°C without agitation. Pure bacterial suspensions (200 µL each) were incubated under similar conditions to serve as controls for self-flocculation.

After 4 hours of incubation, the optical density (OD) of the mixtures and the pure bacterial suspensions was measured at 600 nm. The co-aggregation percentage was calculated using the following formula described by Malik et al. [

25]:

Where:

ODSac represents the OD600 of S. cerevisiae at time T0.

ODBact represents the OD600 of the bacterial suspension at time T0.

ODMix represents the OD600 of the mixture after 4 hours of incubation.

Survival Under Simulated In Vitro Digestion Conditions

The survival of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) during simulated in vitro digestion was assessed following the method described by Seiquer et al. [

16] with some modifications. Initially, the strains were grown in skimmed milk for 8 hours at 30°C. One gram of the resulting fermented milk was then diluted to 1/10 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To simulate gastric digestion, the pH of the sample was adjusted to 3.0, and pepsin was added to a final concentration of 5% (w/v). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 90 minutes with agitation at 110 rpm. For the intestinal digestion simulation, the pH was adjusted to 6.0, and solutions of pancreatin and bile salts were added to final concentrations of 0.1% and 0.3% (w/v), respectively. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 150 minutes, with agitation at 110 rpm. After digestion, the number of viable cells was determined by serial dilution and plating on MRS agar under anaerobic conditions, with incubation at 37°C for 48 hours. The survival of LAB was expressed as the log percentage of the final bacterial count (log10 CFU/mL) relative to the initial count (log10 CFU/mL), allowing for a comparison of different isolates despite differences in initial bacterial concentrations.

Antagonistic Activity

The antibacterial activity of the selected isolates was evaluated using the agar spot-on-lawn test, as described by Schillinger and Lücke [

17] with some modifications. The indicator bacteria used in this study included

Listeria innocua,

Micrococcus luteus, and

Escherichia coli. One microliter of each overnight culture of the selected lactic acid bacteria (LAB) was spotted onto MRS plates containing 0.2% glucose and 1.2% agar. These plates were then incubated under anaerobic conditions for 48 hours to allow colony development. A 0.25 mL portion of a 1:10 dilution of an overnight culture of the indicator bacteria was added to 9 mL of Brain Heart Infusion (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) soft agar (0.7% agar). The medium was then immediately poured over the MRS plate on which the tested LAB strain had grown. The plates were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 24 hours. Antibacterial activity was determined based on the clear inhibition zone around the LAB colonies, which was calculated by measuring the difference between the total inhibition zone diameter and the diameter of the growth spot of the selected strains. Zones with diameters larger than 1 mm were considered to exhibit antagonistic activity, as per the criteria outlined by Yavuzdurmaz [

18]. To further assess the antagonistic activity, 1 µL of the LAB culture was replaced with 1 µL of nisin solution.

Safety Assessment of Enterococcus faecium Strains

Antibiotic Susceptibility

The antibiotic susceptibility of the Enterococcus faecium strains was determined using the agar disc diffusion method. The strains were grown overnight in MRS broth at 37°C, and 100 µL of the diluted culture (approximately 10^6 viable cells) was streaked onto MRS agar plates. The following antibiotics were used at the indicated concentrations: 30 µg Tetracycline, 10 µg Ampicillin, 1000 µg Kanamycin, 15 µg Erythromycin, 30 µg Rifampicin, and 30 µg Vancomycin. The plates were incubated at 37°C under anaerobic conditions for 18 hours, and the inhibition zones were measured. According to CLSI zone diameter interpretative standards, strains were considered resistant if the inhibition zone diameter was less than 17 mm for Vancomycin, Erythromycin, and Tetracycline; less than 16 mm for Ampicillin; and less than 10 mm for Kanamycin [

19].

Cytotoxic Assay on STC-1 Cells

The cytotoxicity of the

Enterococcus faecium strains was evaluated on STC-1 cells according to the method of Rindi et al. [

20]. Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at 7000 cells per well in 150 µL of DMEM medium (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 4.5 g/L glucose, 5% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 IU/mL penicillin) and cultured for approximately 72 hours at 37°C in a 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere until they reached confluence. The DMEM medium was then removed, and the cells were washed twice with minimum medium (without serum or antibiotics). A volume of 80 µL of minimum medium containing bacterial strains at concentrations of 10^5 or 10^7 CFU/mL was added, with sterile minimum medium serving as the control. Twenty µL of propidium iodide at a concentration of 5 µg/mL was added to each well. Fluorescence emission was monitored over 60 minutes, every 30 seconds, using excitation/emission wavelengths of 575/615 nm with 5 nm slits, on a spectrofluorimeter (SAFAS, Monaco). The results were expressed as the fluorescence emission “fold of control” compared to non-treated cells.

Statistical Study

All tests were replicated three times, and the data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The present work's statistical analysis was carried out using XLSTAT software (2014.5.03, Addinsoft, Pearson edition, Waltham, MA, USA). Differences are considered significant at p ˂ 0.05.

Results and Discussion

3.Recovery and Preliminary Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria

A total of 62 strains were isolated from camel milk using MRS agar incubated at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. All isolates were Gram-positive, non-motile cocci, and catalase-negative, which are typical preliminary characteristics of lactic acid bacteria.

3.Functional Screening: Acid and Bile Salt Resistance

Resistance to low pH is a key criterion in selecting potential probiotic strains [

21], as they must survive the harsh conditions of the stomach to reach the small intestine [

22]. In this study, only 26 isolates demonstrated tolerance to acidic conditions and were subsequently tested for bile salt resistance.

At this stage, ten strains were selected for further probiotic evaluation and molecular identification. These strains exhibited good tolerance to bile salts: eight strains (SSC1-2, SCC1-6, SCC1-8, SCC1-13, SCC1-15, SCC1-24, SCC1-33, and SLch14) maintained survival rates above 0.5 OD600 units after incubation, while two strains (SCC1-7 and SLch6) showed survival rates exceeding 1 OD600 unit.

3.Genetic Characterization of Isolates by 16S rRNA Sequencing

A ~1500 bp fragment of the 5' region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced for the ten selected isolates. Sequence analysis using the NCBI database revealed that all ten isolates shared 99% identity with

Enterococcus faecium (

Table 1).

These results are consistent with previous studies reporting that lactic acid bacteria isolated from camel milk are predominantly

Enterococcus species [

23]. Specifically,

E. faecium has been previously isolated from Egyptian camel milk [

24], as well as from both raw and fermented Bactrian camel milk [

25].

3.Evaluation of Adhesion to Organic Solvents, Gastric Mucin, and Intestinal Cells

3.4.Microbial Adhesion to Hydrocarbons (MATH) Assay of E. faecium Strains

Bacterial adhesion to organic solvents is involved in various interfacial phenomena, including microbial attachment to host tissues and surfaces. In this study, the adhesion of

Enterococcus faecium strains to chloroform and ethyl acetate was assessed to determine the Lewis acid-base characteristics of their cell surfaces. Chloroform, an acidic solvent and electron acceptor, and ethyl acetate, a basic solvent and electron donor, were used following the methodology described by Kos et al. [

14].

Our findings revealed that the tested strains exhibited medium to low affinity toward both solvents (

Table 2). The highest adhesion to chloroform was observed for

E. faecium SCC1-13 (30.4% ± 7.58), SCC1-15 (28.6% ± 5.05), and SLch6 (25.5% ± 0.76), while the lowest adhesion was recorded for SCC1-2 (12% ± 5.66). In contrast, the affinity to ethyl acetate ranged from 0% to 34.56% ± 4.88, with SCC1-8 showing the highest adhesion and SCC1-13 the lowest. These results suggest that most strains possess predominantly acidic and electron-accepting surface properties.

Interestingly, SCC1-13 demonstrated a higher affinity for chloroform than ethyl acetate (30.4% vs. 0%), indicating a non-acidic, electron-donor character of its surface [

26].

Our results are in agreement with previous studies by Kos et al. [

14], who reported similar trends for

Lactobacillus acidophilus M92 and

E. faecium L3, with high adhesion to chloroform (36.06% and 61.21%, respectively) and no adhesion to ethyl acetate. Similarly, Xu et al. [

27] observed high adhesion to chloroform in

L. brevis (52.9%),

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (51.2%), and

L. rhamnosus GG (47.7%), while strains such as

L. acidophilus ADH (22.6%) and

Pediococcus acidilactici (25.8%) showed lower affinities. In contrast to chloroform, bacterial adhesion to ethyl acetate was generally lower, ranging between 5.1% and 16.9%.

Comparable findings were reported by Singh et al. [

28] for various

L. reuteri strains, with adhesion to chloroform ranging from 32.86% to 80.45%, and relatively lower values for ethyl acetate, aligning with our results. Other authors have also described variable adhesion capacities, typically between 5% and 47% [

29].

3.4.Adhesion to Gastric Mucin and STC-1 Cells

The adhesion and colonization of probiotic bacteria within the host gastrointestinal tract are considered essential for exerting their beneficial effects. This includes preventing washout by intestinal peristalsis [

30], promoting colonization [

31], stimulating the host immune system [

32], and providing antagonistic activity against enteropathogens [

33].

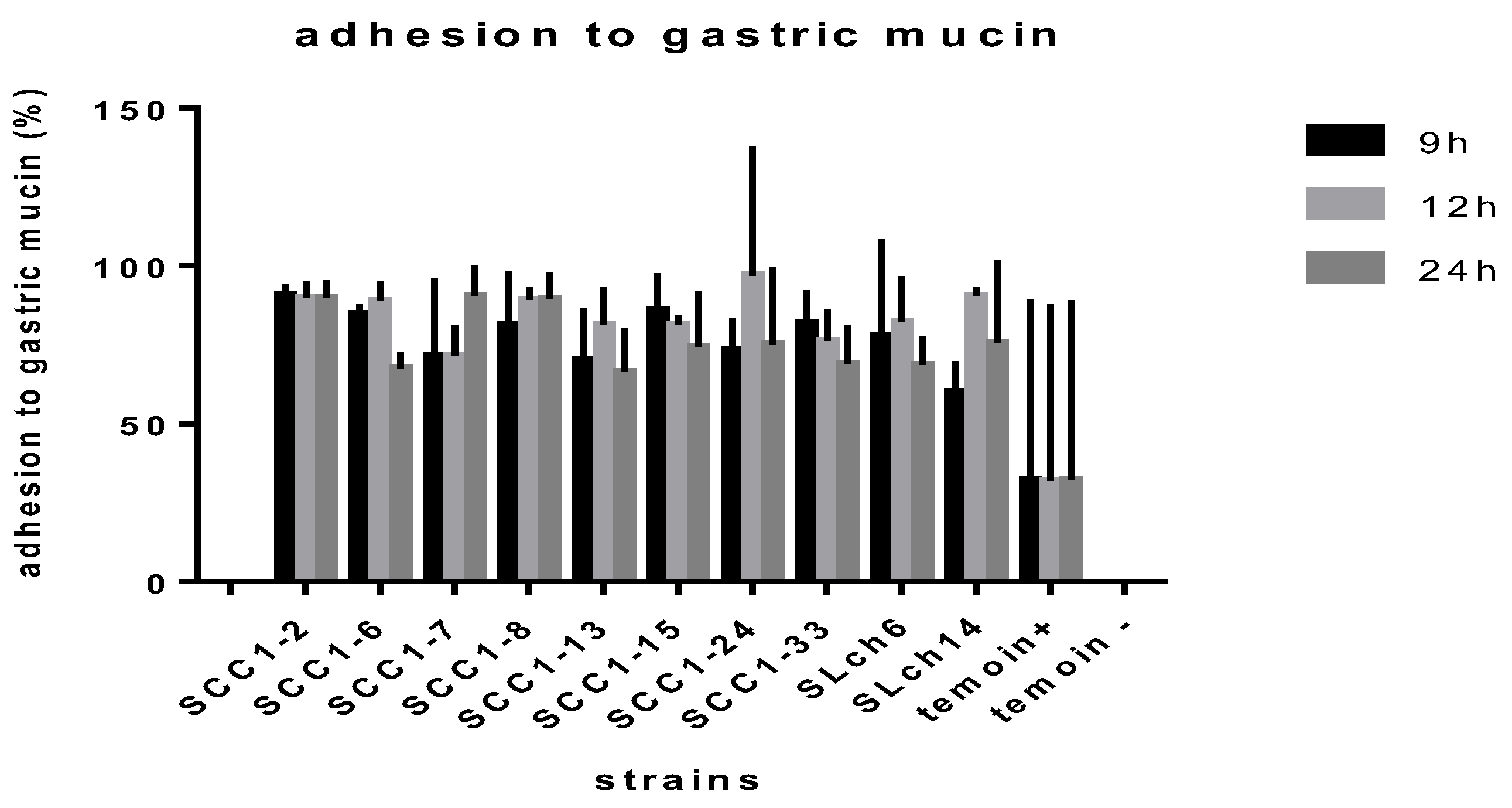

The selected

Enterococcus faecium strains were evaluated for their adhesion to gastric mucin at different growth phases (

Figure 1). All strains exhibited strong adhesion to mucin, with rates exceeding 60% throughout all stages of growth. However, a decline in adhesion was observed during the stationary phase, likely due to nutrient depletion and the accumulation of metabolic byproducts.

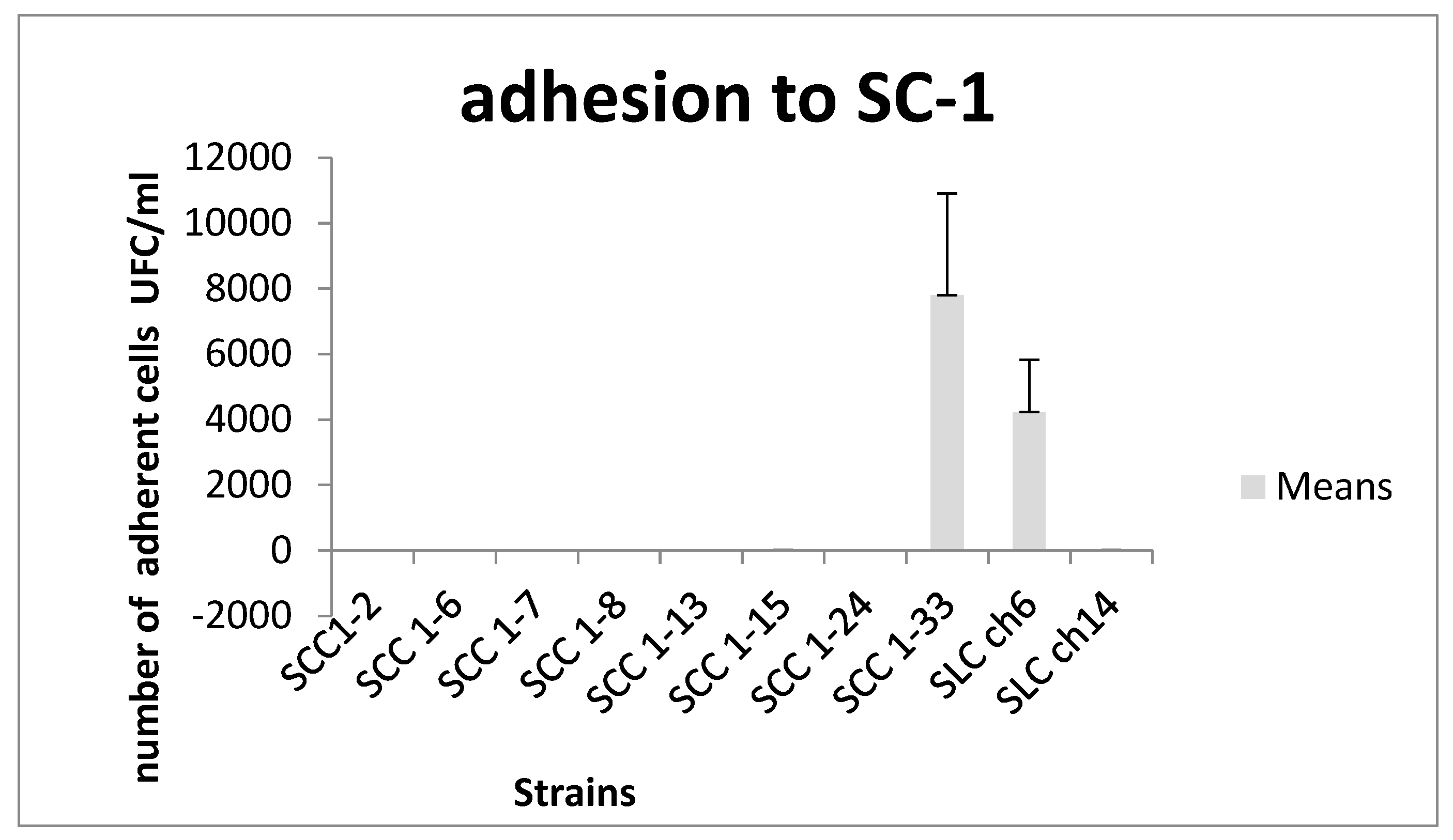

In addition, the adhesion capacity of the ten strains to STC-1 epithelial cells was assessed in vitro. Overall, E. faecium strains demonstrated low adhesion levels to STC-1 cells. Only two strains—SCC1-33 and SLch6—showed a notable ability to colonize epithelial cells, with adhesion values of 7.8 × 10³ and 4.2 × 10³ CFU/mL, respectively.

These values are comparable to those reported by Kotikalapudi [

34] for

Bacillus catenulatum (3.1 × 10³ CFU/mL) and significantly higher than those found for

Bifidobacterium adolescentis and

Bifidobacterium infantis, which exhibited relatively poor adhesion at the end of the assay, with values of 2.6 × 10¹ and 1.5 × 10¹ CFU/mL, respectively.

3.Auto-Aggregation and Co-Aggregation

Auto-aggregation and co-aggregation are essential properties of probiotic organisms as they contribute to their retention within the gastrointestinal tract, preventing their elimination. The auto-aggregation and co-aggregation abilities of the selected probiotic strains are presented in

Table 2 Among the ten

Enterococcus faecium strains tested, six strains exhibited a high auto-aggregation rate (greater than 60%). All strains demonstrated strong co-aggregation with

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, with the highest rates observed at 20°C. Ayyash et al. [

23] reported lower co-aggregation values for

Enterococcus and

Streptococcus strains isolated from camel milk, which co-aggregated with pathogenic bacteria at both 20°C and 37°C.

According to Jensen et al. [

35], bacterial adhesion is a multifactorial process, not solely attributed to a single component. It involves electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and specific bacterial surface structures, all contributing to the overall adhesion and aggregation process.

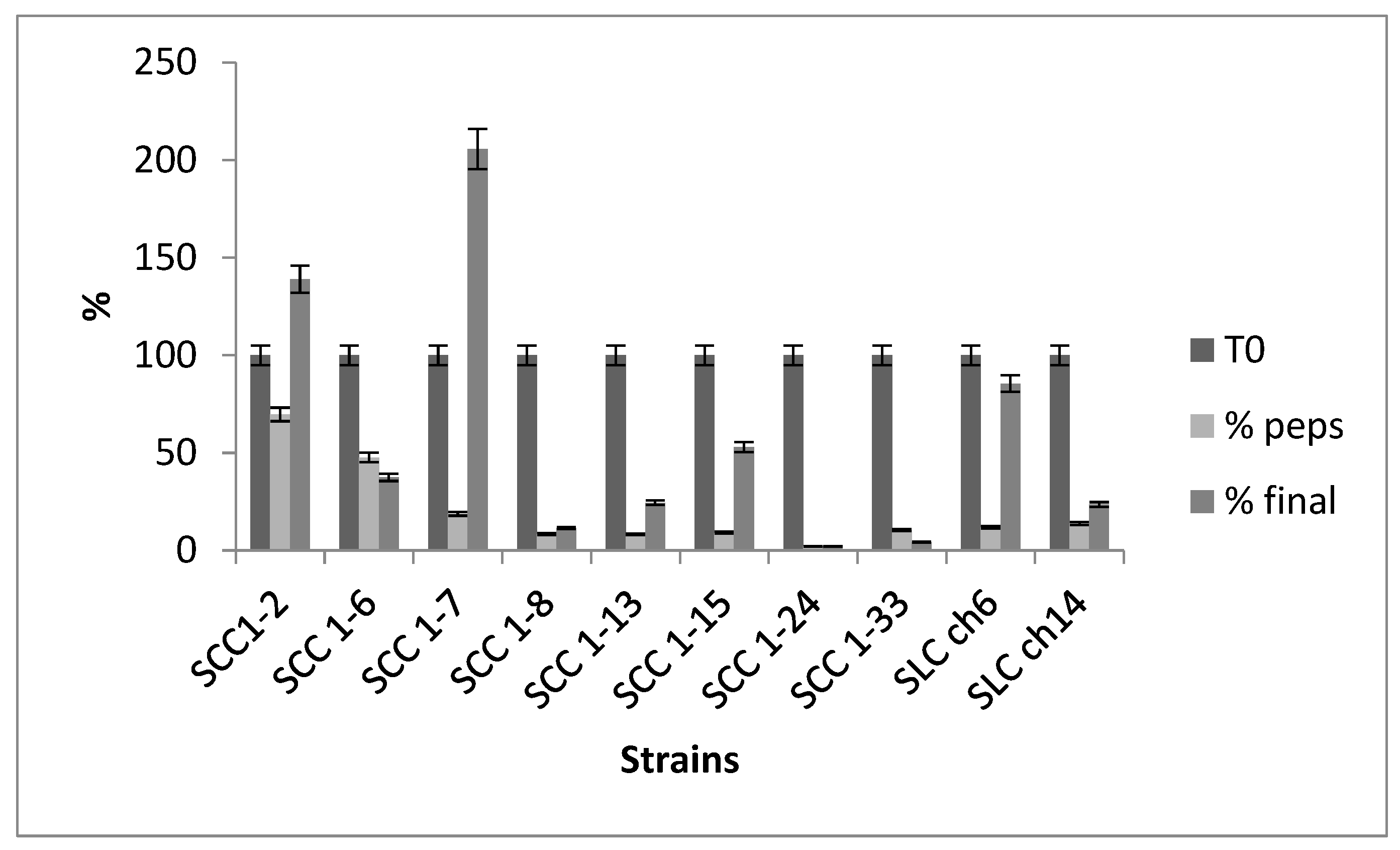

3.Survival in Simulated In Vitro Digestion

The ability of probiotic strains to survive under the harsh conditions of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is crucial for their therapeutic effects, as their health benefits are closely related to their ability to reach the intestine in sufficient numbers. The selected strains were subjected to simulated gastric and intestinal digestion to assess their viability under these stressful conditions. The results, shown in

Figure 2, indicated that two strains, SCC1-2 and SCC1-7, were able to multiply in simulated intestinal fluid. Two other strains, SCC1-5 and SLch6, exhibited a survival rate greater than 50%. Three strains had low survival rates, ranging from 11% to 37%, while two strains did not survive the simulated gastric or intestinal transit, with survival rates lower than 5%. These results are consistent with findings by Nascimento [

36] for

Enterococcus faecium strains SJRP20 and SJRP65, which also demonstrated limited survival under similar conditions.

Figure 2.

Adhesion of strains to SC-1 cells in terms of means.

Figure 2.

Adhesion of strains to SC-1 cells in terms of means.

Figure 3.

Resistance of 10 LAB strains to simulated in vitro digestion.

Figure 3.

Resistance of 10 LAB strains to simulated in vitro digestion.

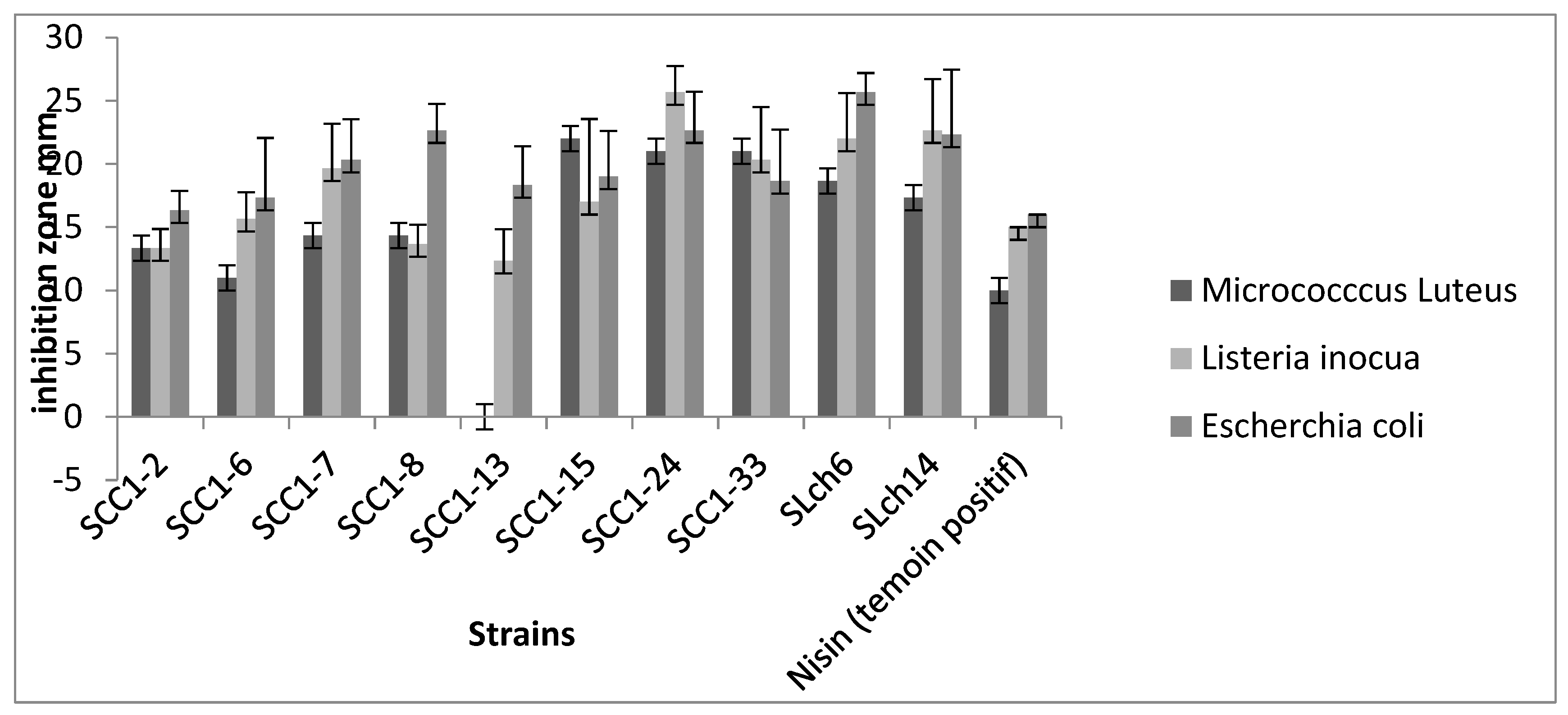

3.Antagonistic Effect

The antagonistic activity of probiotic strains, especially their ability to inhibit pathogens in the GIT, is a key trait for their potential as probiotics. The antagonistic activity of the ten

Enterococcus faecium strains was tested against various pathogens (

Figure 4). All strains demonstrated significant antagonistic effects against the tested pathogens, with varying intensities between strains. However, the SCC1-13 strain did not inhibit the growth of

Micrococcus luteus. Several studies have reported the antibacterial activity of

Enterococcus species. For instance,

Enterococcus strains have an inhibitory spectrum that includes not only Gram-positive pathogens such as

Listeria monocytogenes,

Staphylococcus spp., and

Clostridium spp [

37], but also Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and yeasts [

38].

E. faecium LCW 44, isolated from camel milk, exhibited a broad antibacterial spectrum, showing inhibitory activity against several Gram-positive strains from the genera

Clostridium,

Listeria,

Staphylococcus, and

Lactobacillus [

39].

3.Safety Evaluation of E. faecium Strains

Antibiotic resistance in

Enterococcus species is a major concern in the medical field, as resistance genes are often carried by plasmids or transposons, posing a risk of horizontal gene transfer [

40]. The susceptibility of the selected

Enterococcus faecium strains to various antibiotics was evaluated (

Table 3). All strains were found to be susceptible to tetracycline, vancomycin, erythromycin, ampicillin, and kanamycin, but resistant to rifampicin. In contrast, De Souza et al. [

41] reported different results for

Lactobacillus casei and

Lactobacillus fermentum strains, which showed resistance to vancomycin. Le Blanc [

42] noted that some

E. faecium strains exhibited resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics, such as vancomycin and teicoplanin. The antibiotic susceptibility profile of the

E. faecium strain SLCh6 aligns with previous reports on

E. faecium strains commonly found in food products and meeting safety criteria [

43].

The cytotoxicity test performed on STC1 cells revealed that the strains did not exhibit significant negative effects, confirming their safety for potential use as probiotics.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that camel milk can serve as a valuable source of probiotic candidates. Among the isolates, Enterococcus faecium SLCch6 exhibited strong potential for application as an effective probiotic, both in the food industry and for therapeutic purposes. This strain showed notable resilience to simulated gastrointestinal conditions, along with high auto-aggregation and co-aggregation abilities, strong adhesion to gastric mucin, and acceptable adhesion to epithelial cells—features that indicate a strong capacity for colonization and survival within the gastrointestinal tract.

In addition, E. faecium SLCch6 displayed significant antagonistic activity against several pathogenic microorganisms. Its susceptibility to commonly used antibiotics further suggests the absence of transferable antibiotic resistance genes, reinforcing its safety profile. However, comprehensive in vivo studies and rigorous safety evaluations are essential before considering the clinical or commercial use of E. faecium SLCch6 as a probiotic.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Imen Fguiri and Manel Ziadi.; methodology, Imen Fguiri and Samira Arroum.; validation, imen Fguiri and Manel Ziadi; writing—original draft preparation, imen Fguiri.; writing—review and editing, Imen Fguiri and Manel Ziadi; supervision, Touhami Khorchani. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”

Data Availability Statement

Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in authors archives.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to central laboratory technicians in arid land institute for their collaboration in biochemical analysis

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LAB |

Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| BATH |

Bacterial Adhesion to hydrocarbons test |

| SCC |

Strain Colostrum Camel |

| SLCh |

Strain Milk Chenchou |

References

- Homayouni, A.; Alizadeh, M.; Alikhah, H.; Zijah, V. Factors influencing probiotic survival in ice cream. Inter J Dairy Sci 2012, 7 (1) 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Espinoza, Y.; Gallardo-Navarro, Y. Non-dairy probiotic products. Food Microbiol 2010, 27: 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.; Newberry, S.J.; Maher, A.R.; Wang, Z.; Miles, J.N.; Shanman, R.; Johnsen, B.; Shekelle, P.G. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012 May 9; 307(18):1959-69. [CrossRef]

- Homayouni, A.; Azizi, A.; Ehsani, M.R.; Yarmand, M.S.; Razavi, S.H.Effect of microencapsulation and resistant starch on the probiotic survival and sensor properties of symbiotic ice cream. Food Chem 2008 111: 50-55. [CrossRef]

- Lankaputhra, W.E.V.; Shah, N.P. Survival of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium ssp. in the presence of acid and bile salts. Cult Dairy Prod J 1995, 30: 2-7.

- Gupta, M.; Bajaj, B.K. Functional characterization of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria isolated from Kalarei and development of probiotic fermented oat flour. Prob. Antimicrob Prot 2018,10 (4): 654-66. [CrossRef]

- Kadri, Z.; Vandamme, P.; Ouadghiri, M.; Cnockaert, M.; Aerts, M.; Elfahime, E.M.; Amar, M. Streptococcus tangierensis sp. Nov. And Streptococcus cameli sp. Nov., two novel Streptococcus species isolated from raw camel milk in Morocco. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014,107(2): 503-510. [CrossRef]

- Konuspayeva, G.; Faye, B.; Loiseau, G.; Levieux, D. Lactoferrin and immunoglobulin contents in camel’s milk (Camelus bactrianus, Camelus dromedarius, and hybrids) from Kazakhstan. J Dairy Sci 2007,90:38-46. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Arora, S.; Li, J.; Rahmani, R.; Sun, L.; Steinlauf, A.F.; Mechanick, J.I. et al. W. Bone, inflammation, and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Osteoporosis Rep 2011. [CrossRef]

- Tanhaeian, A.; Shahriari Ahmadi, F.; Sekhavati, M.H.; Mamarabadi, M. Expression and purification of the main component contained in camel milk and its antimicrobial activities against bacterial plant pathogens. Prob Antimicrob Prot 2018, 10 (4): 787-793. [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaibi, M.M.; Al-Zoreky, N.S.; El-Dermerdash, H.A. Camel's milk as a natural source for probiotics. Res J Microbiol 2013, 8 (2):70. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, J.; Gill, H.; Smart, J.; Gopal, P.K. Selection and characterization of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains for use as probiotics. Int. Dairy J 1998, 8: 993-1002. [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C.; Meriluoto, J.; Salminen, S. Adhesion and aggregation properties of probiotic and pathogen strains. Eur Food Res Technol 2008, 226: 1065-1073. [CrossRef]

- Kos, B.; Suskovic, J.; Vukovic, S.; Simpraga, M.; Frece, J.; Matosic, S. Adhesion and aggregation ability of probiotic strain Lactobacillus acidophilus MJ Appl Microbiol 2008, 94:981–987. [CrossRef]

- Del Re, B.; Sgorbati, B.; Miglioli, M.; Palenzola, D. Adhesion, auto-aggregation and hydrophobicity of 13 strains of Bifidobacterium longum. Lett Appl Microbiol 2000, 31: 438-442. [CrossRef]

- Seiquer, I.; Aspe, T.; Vaquero, P.; Navarro, P. Effects of heat treatment of casein in the presence of reducing sugars on calcium bioavailability: in vitro and in vivo assays. J Agri Food Chemist 2001, 49:1049-1055. [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, U.; Lucke, F.K. Antimicrobial activity of Lactobacillus sake isolated from meat. Appl Environ Microbiol 1989, 55 (8): 1901-. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yavuzdurmaz, H. Isolation, characterization, determination of probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria from human Milk. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Engineering and Sciences of Izmir Institute, 2007, pp 1-69.

- Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Eighteenth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S18, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 46–52, 2008.).

- Rindi, G.; Grant, S.G.;, Yiangou, Y.; Ghatei, M.A.; Bloom, S.R.; Bautch, V.L.; Solcia, E.; Polak, J.M. Development of neuroendocrine tumors in the gastrointestinal tract of transgenic mice. Heterogeneity of hormone expression. Am J Pathol 1990, 136 (6):1349-1363.

- . [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Çakır, I. Determination of some probiotic properties on Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria. Ankara University Thesis of Ph.D. 2003.

- Chou, L.S.; Weimer, B. Isolation and characterization of acid and bile tolerant isolates from strains of Lactobacillus acidophilus. J Dairy Sci 1999, 82: 23-31. [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M.; Abushelaibi, A.; Al-Mahadin, S.; Enan, M.; El-Tarabily, K.; Shah, N. In-vitro investigation into probiotic characterisation of Streptococcus and Enterococcus isolated from camel milk. LWT 2018, 87:478-487. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, E. Elattar, A. Identification and some probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Egyptian camels milk. Life Sci J 2013, 10(1): 1952-1961.

- Akhmetsadykova, S.; Baubelkopva, A.; Konuspayeva, G.; Akhmetsadykov, N.; Loiseau, G. Microflora identification of fresh and fermented camel milk from Kazakhstan. Emi J Food Agric 2014, 26(4): 327-332. [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.; Bouley, C.; Cayuela, C.; Bouttier, S.; Bourlioux, P.; Bellon-Fontaine, M.N. Cell surface characteristics of Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei, Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997, 63: 1725–173. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jeong, H.S. Lee, H.Y.; Ahn, J. Assessment of cell surface properties and adhesion potential of selected probiotic strains. LAM 2009, 49: 434-442. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Bioactive compounds in banana and their associated health benefits – A review. Food Chem. 2016, Volume 206, 1 Pages 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Angmo, K.; Kumari, A.; Bhalla, C. Probiotic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented foods and beverage of Ladakh. LWT- Food Sci Technol 2015, 66:428–435. [CrossRef]

- Bernet-Carnard, M.F.; Lievin, V.; Brassart, D.; Neeser, J.R.; Servin, A.L.H. The human L. acidophilus strain LA1 secretes a non bacteriocin anti-bacterial substance(s) active in vitro and in vivo. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997, 63: 2747-2753. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alander, M.; Satokari, R.; Korpela, R.; Saxelin, M.; Vilpponen-Salmela, T.; Mattila-Sandholm, T.; et al. Persistence of colonization of human colonic mucosa by a probiotic strain, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, after oral consumption. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffrin, E.J.; Rochat, F.; Link-Amster, H.; Aeschlimann, J.M.; Donnet-Hughes, A. Immunomodulation of human blood cells following the ingestion of lactic acid bacteria. J. Dairy Sci. 1995, 78, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coconnier, M.H.; Bernet, M.F.; Kernéis, S.; Chauvière, G.; Fourniat, J.; Servin, L. Inhibition of adhesion of enteroinvasive pathogens to human intestinal Caco-2 cells by Lactobacillus acidophilus strain LB decreases bacterial invasion. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1993, 110, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotikalapudi, B.L. Characterization and encapsulation of probiotic bacteria using a pea-protein alginate matrix. Thesis. 2009, 62-138.

- Jensen, H.; Grimmer, S.; Naterstad, K.; Axelsson, L. In vitro testing of commercial and potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Inter. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, Amsterdam, v. 153, n. 1- 2, p. 216–222.

- Nascimento, L.C.S. Probiotic and substance of production of antimicrobial cultures are capable of lactating acid and application in the Leite Fermentado. Ph D. Thesis, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos, Instituto de Biociências, Letras e Ciências Exatas, Universidade Estadual Paulista.2015.

- Ghrairi, T.; Frere, J.; Berjeaud, J.M.; Manai, M. Purification and Characterisation of Bacteriocins Produced by Enterococcus faecium from Tunisian Rigouta Cheese. Food Control 2008, 19, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Galvez, A.; Dubois-Dauphin, R.; Campos, D.; Thonart, P. Genetic determination and localization of multiple bacteriocins produced by Enterococcus faecium CWBI-B1430 and Enterococcus mundtii CWBI-BFood Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 20: 289–296. [CrossRef]

- Vimont, A. ; Fernandez, B. ; Hammami, R. ; Ababsa, A.; Daba, H.; Fliss, I. Bacteriocin-producing Enterococcus faecium LCW 44: A high potential probiotic candidate from raw camel milk. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, p. 865. [CrossRef]

- Hasman, H.; Villadsen, A.G.; Aarestrup, F.M. Diversity and stability of plasmids from glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium (GRE) isolated from pigs in Denmark. Microb Drug Resis 2009,11:178-184. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, B.M.S.; Borgonovi, T.F.; Casarotti, S.N.; Todorov, S.D.; Barretto Penna, A.L. Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus fermentum strains isolated from Mozzarella cheese: probiotic potential, safety, acidifying kinetic parameters and viability under gastrointestinal tract conditions. Prob Antimicrob Prot 2019, 11(2):382-396. [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, D.J. Enterococcus. In: Dworkin M (ed), The prokaryote.2006, 3rd edn vol. Springer, New York,NY, pp 175-204.

- Banwo, K.; Sanni, A.; Tan, H. Functional properties of Pediococcus species isolated from traditional fermented cereal gruel and milk in Nigeria. Food Biotechnol 2013, 27(1), 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).