Submitted:

29 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin and Collection of Milk Samples

2.2. Isolation, Purification, and Preservation of LAB Isolates

2.3. Phenotypic, Physiological, and Biochemical Characterization

2.4. Bacterial Species Identification by MALDI-TOF MS

2.4.1. Matrix Preparation

2.4.2. Sample Deposition on the MALDI-TOF MS Target

2.4.3. Spectral Acquisition and Species Identification

- Score ≥2.0: Secure identification at the species level

- Score 1.7–1.99: Probable identification at the genus level

- Score <1.7: Unreliable identification

2.5. Evaluation of the Technological Properties of LAB Strains

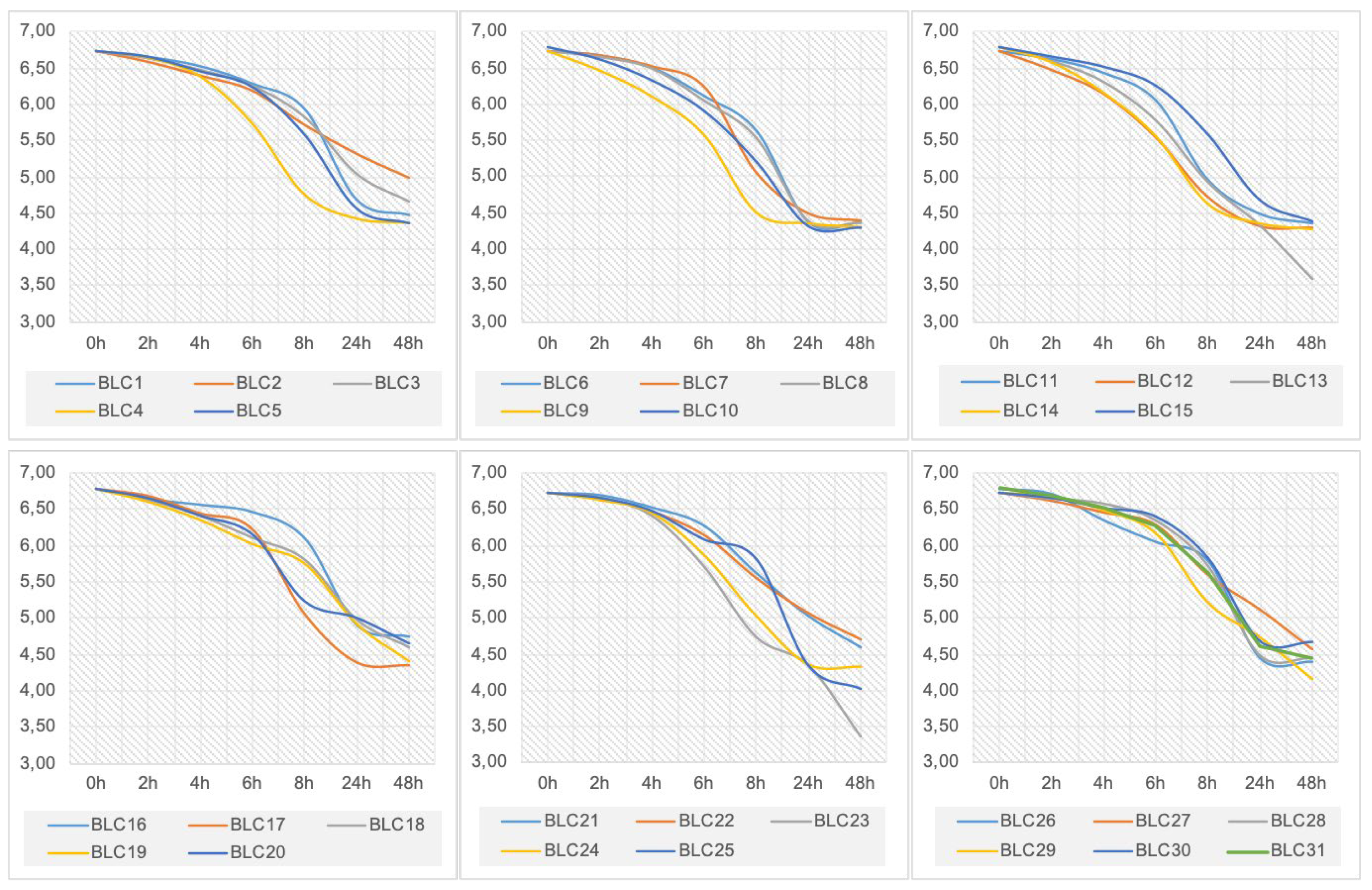

2.5.1. Acidification Activity

- pHinitial: Initial pH of the UHT milk

- pHmeasured: pH recorded after the incubation period

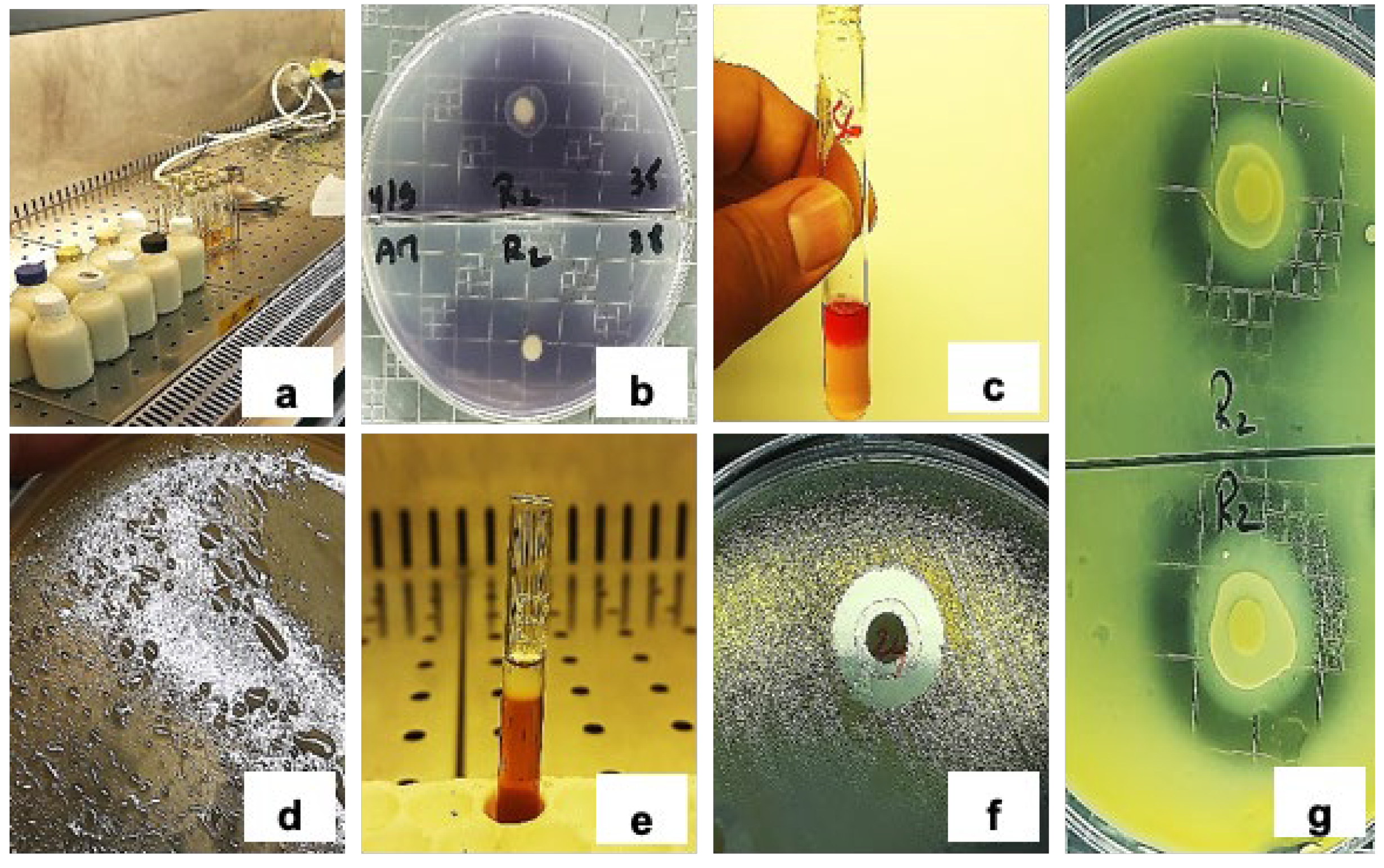

2.5.2. Lipolytic Activity

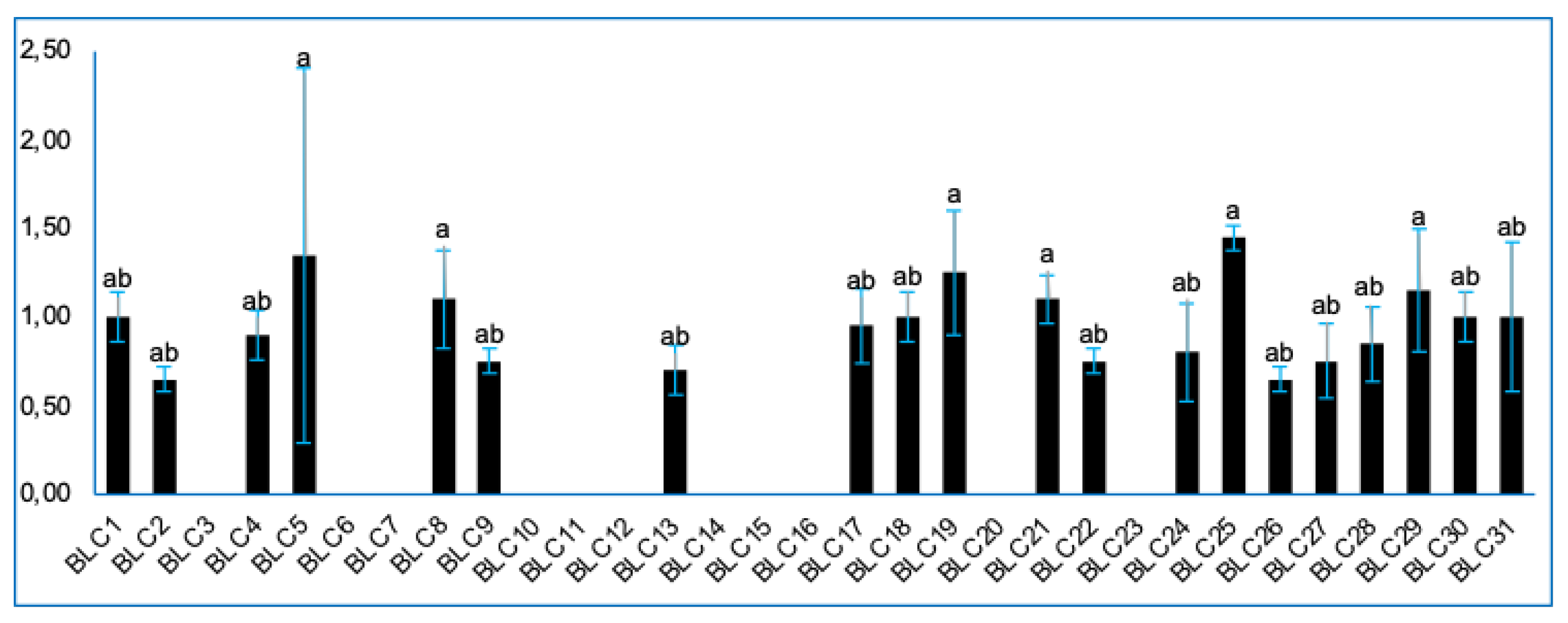

2.5.3. Proteolytic Activity

2.5.4. Exopolysaccharide (EPS) Production

2.5.5. Amylase Production Potential

2.5.6. Acetoin Production Capacity

2.6. Antimicrobial Activity Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

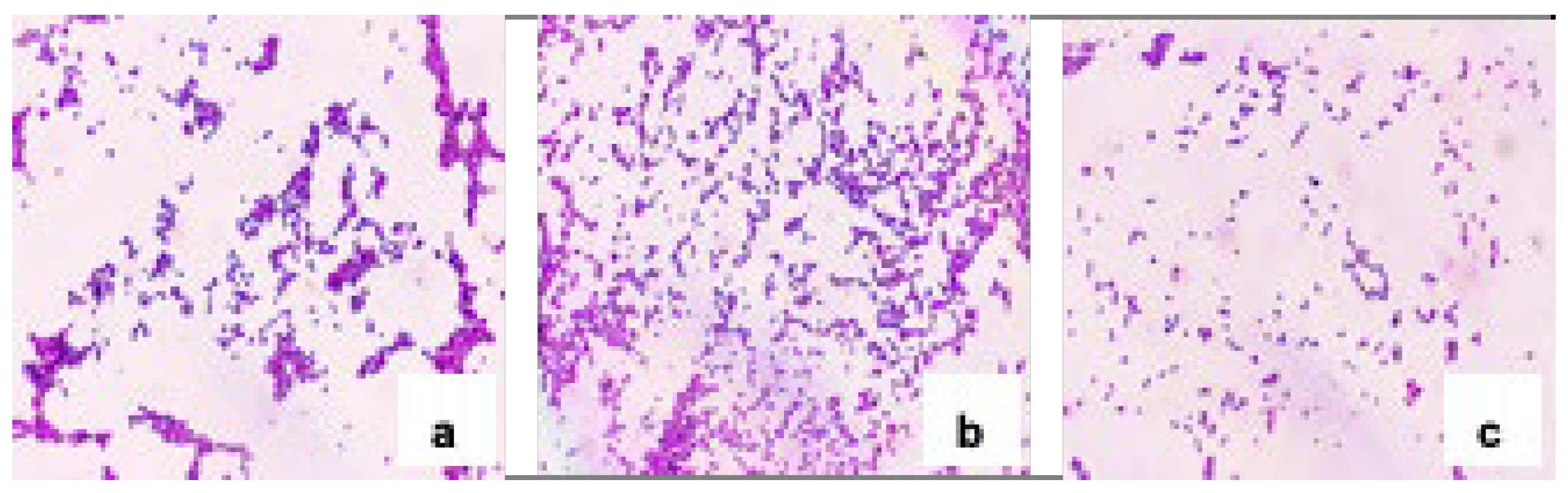

3.1. Isolation and Preliminary Characterization

3.2. Phenotypic Characterization

- 27 strains were identified as belonging to the Lactococcus genus. These strains were tetrad-negative, capable of growth at 10 °C but not at 45 °C, did not produce CO2, and were intolerant to alkaline conditions (pH 9.6).

- 2 strains were assigned to the Enterococcus genus, characterized by growth at 45 °C, tolerance to 6.5% NaCl and pH 9.6, and absence of tetrads.

- The single Leuconostoc isolate produced CO2 but tested negative for arginine dihydrolase activity.

- One isolate, identified as Lactobacillus, demonstrated growth at 15 °C without CO2 production (Figure 3).

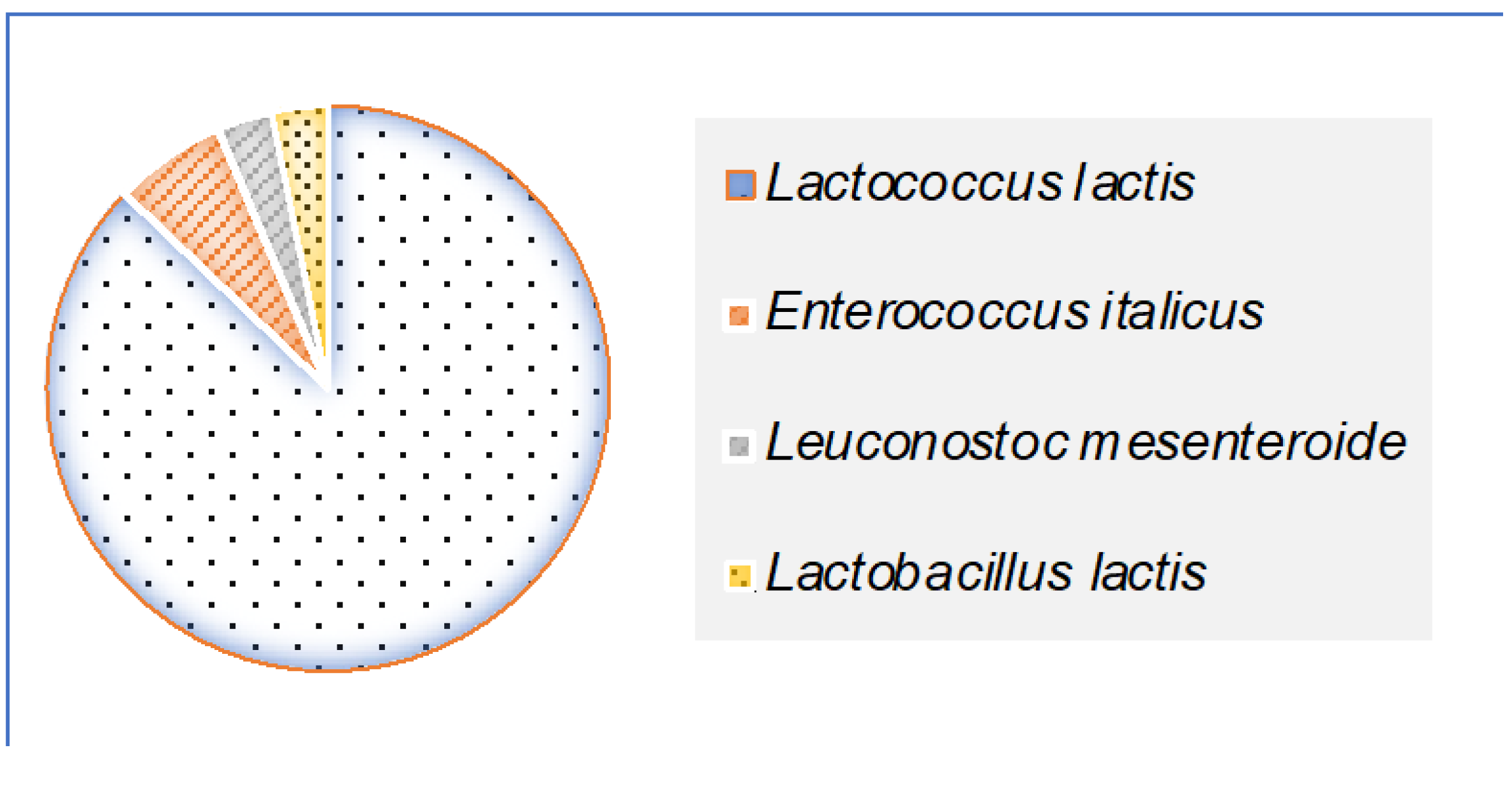

3.3. MALDI-TOF MS Identification of LAB Isolates

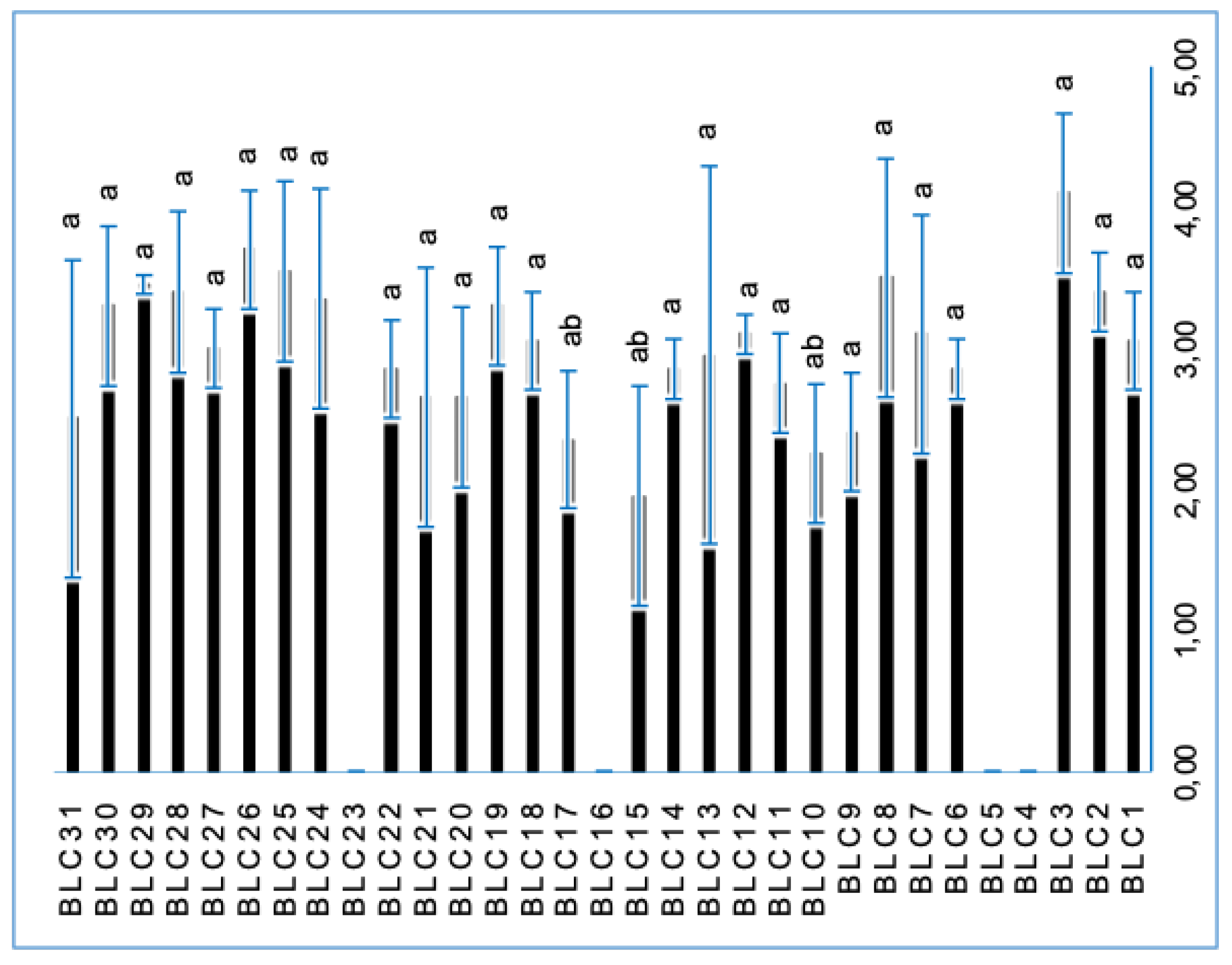

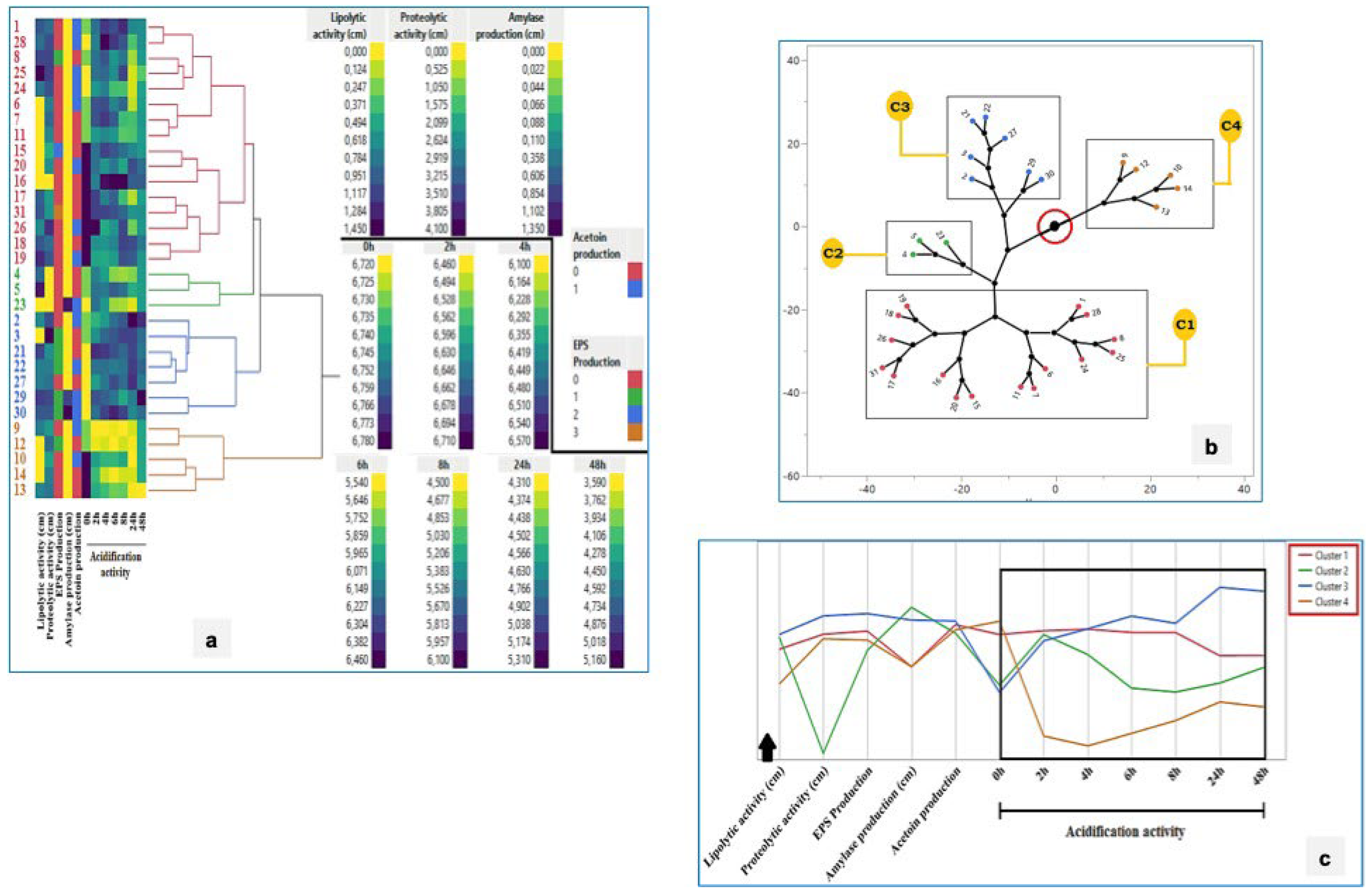

3.4. Acidification Activity

3.5. Lipolytic Activity

3.6. Proteolytic Activity

3.7. Exopolysaccharide (EPS) Production

3.8. Amylolytic Activity

3.9. Acetoin Production

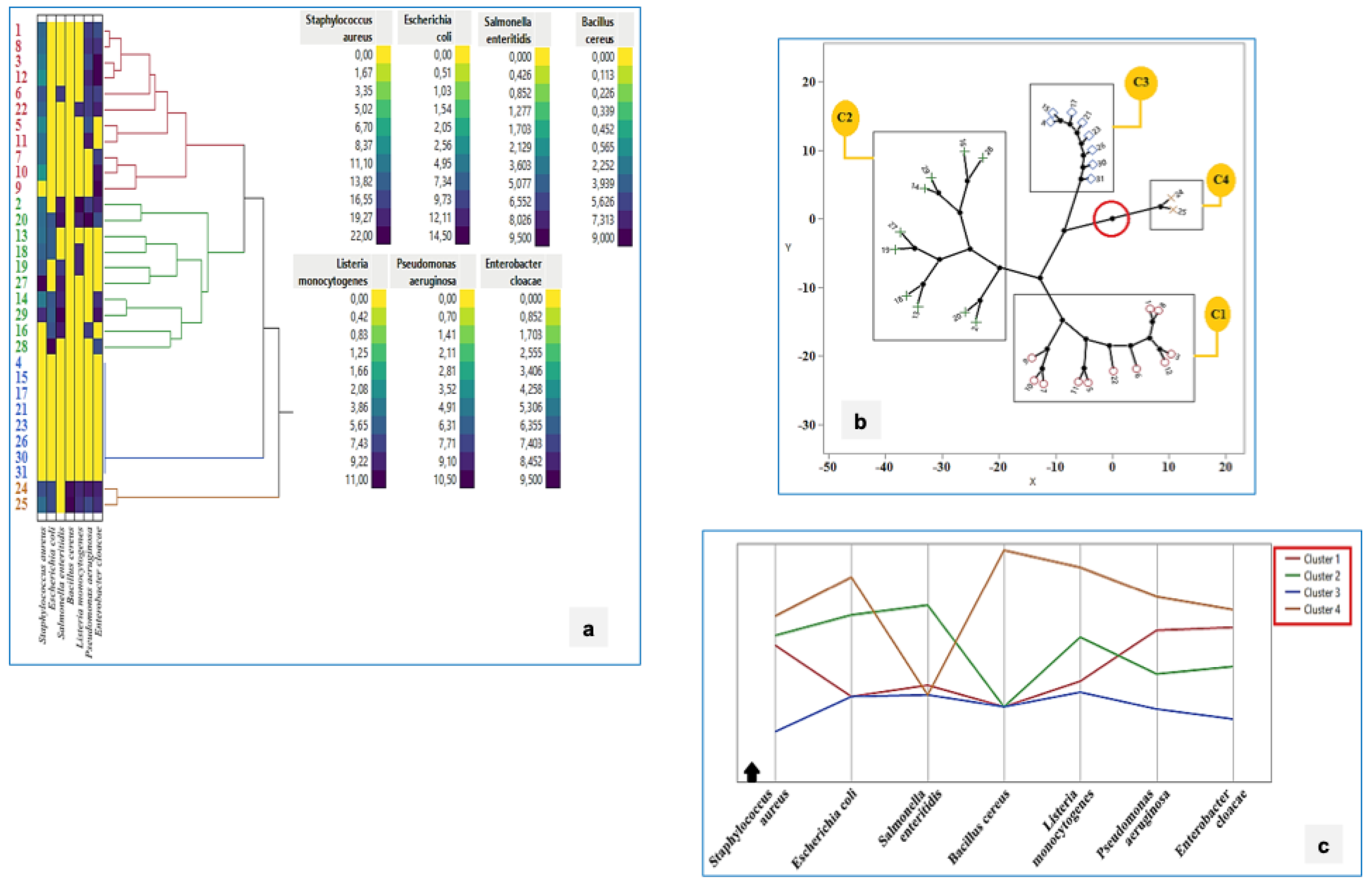

3.10. Antimicrobial Activity

- Enterobacter cloacae (51.6% of strains), with inhibition zones of 7.0 ± 0 mm to 9.5 ± 0.7 mm;

- Escherichia coli (29.0%), with zones ranging from 7.5 ± 0.7 mm to 14.5 ± 2.1 mm;

- Salmonella enteritidis (25.8%), with inhibition zones between 7.0 ± 0 mm and 9.5 ± 0.7 mm;

- Listeria monocytogenes (25.8%), with diameters ranging from 8.5 ± 0.7 mm to 11.0 ± 5.7 mm;

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa (41.9%), with zones from 7.0 ± 0 mm to 10.5 ± 0.7 mm;

- Bacillus cereus (6.5%), with zones between 8.5 ± 0.7 mm and 9.0 ± 1.4 mm.

3.11. Visual Summary of Technological and Antimicrobial Traits

3.12. Cluster Analysis of Technological and Antimicrobial Properties

3.13. Cluster Analysis of Antibacterial Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arena. M.P.; Russo. P.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. Exploration of the microbial biodiversity associated with north Apulian sourdoughs and the effect of the Increasing Number of Inoculated Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains on the Biocontrol against Fungal Spoilage. Fermentation 2019, 5, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatti-Kaul, R.; Chen, L; Dishisha, T. ; Enshasy, H.E. Lactic acid bacteria: from starter cultures to producers of chemicals. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2018, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, H.; Ozogul, F.; Bartkiene, E.; Rocha, J. M. Impact of lactic acid bacteria and their metabolites on the techno-functional properties and health benefits of fermented dairy products. Crit Revt Food Scit Nutr 2023, 63, 4819–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anumudu, C. K.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H. Multifunctional Applications of Lactic Acid Bacteria: Enhancing Safety, Quality, and Nutritional Value in Foods and Fermented Beverages. Foods 2024, 13, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer Valenzuela, J.; Pinuer, L. A.; Garcia Cancino, A.; Borquez Yanez, R. Metabolic fluxes in Lactic acid bacteria—A review. Food Biotechnol 2015, 29, 185–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, R. H. H.; López-Malo, A.; Mani-López, E. Antimicrobial activity and applications of fermentates from lactic acid bacteria–a review. Sustain Food Technol 2024, 2, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulini, F. L.; Hymery, N.; Haertlé, T.; Le Blay, G.; De Martinis, E. C. Screening for antimicrobial and proteolytic activities of lactic acid bacteria isolated from cow, buffalo and goat milk and cheeses marketed in the southeast region of Braz. J Dairy Res 2016, 83, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayed, L.; M’hir, S.; Nuzzolese, D.; Di Cagno, R.; Filannino, P. Harnessing the health and techno-functional potential of lactic acid bacteria: A comprehensive review. Foods 2024, 13, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.; Tungare, K. , Jathar, S.; Priyaranjan Kunal, S.; Jha, P.; Desai, N.;Jobby, R. Isolation, characteriation and therapeutic evaluation of lactic acid bacteria from traditional and non-traditional sources. Food Biotechnol 2023, 37, 364–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, I. A.; Yang, L.; Farag, M. A.; Korma, S. A.; Khalifa, I.; Cacciotti, I. . Wang, X. A comprehensive review of the composition, nutritional value, and functional properties of camel milk fat. Foods 2021, 10, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudalia, S.; Gueroui, Y.; Zebsa, R; , Arbia, T. ; Chiheb, A. E; Benada, M. H.;... & Bousbia, A. Camel livestock in the Algerian Sahara under the context of climate change: Milk properties and livestock production practices. J Agric Food Res 2023, 11, 100528. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Lavania, M.; Singh, R.; Lal, B. Identification and probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria from camel milk. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meruvu H; Harsa ST Lactic acid bacteria: Isolation–characterization approaches and industrial applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 63, 8337–8356. [CrossRef]

- Iruene, I. T.; Wafula, E. N.; Kuja, J.; Mathara, J. M. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from spontaneously fermented vegetable amaranth. Afr J Food Sci 2021, 15, 254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Mulaw, G.; Sisay Tessema, T.; Muleta, D.; Tesfaye, A. In vitro evaluation of probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from some traditionally fermented Ethiopian food products. Int J Microbiol 2019, 2019(1), 7179514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, F.J.; Chill, D.; Maida, N. The lactic acid bacteria: a literature survey. Crit Rev Microbiol 2002, 28, 281–370. [PubMed]

- Ghalouni, E.; Hassaine, O.; Karam, N. E. Phenotypic Identification and Technological Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from L’ben, An Algerian Traditional Fermented Cow Milk. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormo, H.; Lekhal, D. A. H.; Roques, C. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from raw goat milk and effect of farming practices on the dominant species of lactic acid bacteria. Int Journal Food Microbiol 2015, 210, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seng, P.; Drancourt, M.; Gouriet, F.; La Scola, B. ,, Fournier, P. E.; Rolain, J. M.; Raoult, D. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis 2009, 49, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos-Lopes, M.; Stanton, C.; Ross, P.; Dapkevicius, M.; Silva, C. Genetic diversity, safety and technological characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from artisanal Pico cheese. Food Microbiol 2017, 63, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettache,G. ; Fatma, A.; Miloud, H.; Mebrouk, K.. Isolation and identification of lactic acid bacteria from Dhan, a traditional butter and their major technological traits. World Appl Sci J 2012, 17, 480–488. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçınkaya, S.; Kılıç, G.B. Isolation, identification and determination of technological properties of the halophilic lactic acid bacteria isolated from table olives J Food Sci Technol 2019 56, 2027-2037.

- Hawaz, E.; Guesh, T.; Kebede, A.; Menkir, S. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria from camel milk and their technological properties to use as a starter culture. East Afr Journal Sci 2016, 10, 49–60.

- Benhouna, I.S.; Heumann, A.; Rieu, A.; Guzzo, J.; Kihal, M.; Bettache, G.; Champion, D.; Coelho, C.; Weidmann, S. Exopolysaccharide produced by Weissella confusa: Chemical characterisation, rheology and bioactivity. Int Dairy J 2019, 90, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.K.; Taneja, N.K.; Jain, D.; Ojha, A.; Kumawat, D.; Mishra, V. In vitro assessment of probiotic and technological properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from indigenously fermented cereal-based food products. Fermentation 2022, 8, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, P. P.; Dasgupta, D.; Ray, A.; Suman, S. K. Challenges and prospects of microbial α-amylases for industrial application: a review. World Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 2024 40, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hashemi, A. N. , & Al-Janabi, N. M. (2023, November). Screening of Bacterial Isolates Producing Diacetyl and Selecting the Most Efficient Isolate. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 1259, No. 1, p. 012079). IOP Publishing.

- Yamato, M. , Ozaki, K. , Ota, F. Partial purification and characterization of the bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus YIT 0154. Microbiol. Res 2003, 158, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Eyassu Seifu., E.S.; Araya Abraham, A.A.; Kurtu, M.Y.; Zelalem Yilma, Z.Y. Eyassu Seifu. E.S.; Araya Abraham, A.A.; Kurtu, M.Y.; Zelalem Yilma, Z.Y. Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from Ititu: Ethiopian traditional fermented camel milk. J Camelid Sci 2012, 5:82-98.

- Abedin, M.M.; Chourasia, R.; Phukon, L.C.; Sarkar, P.; Ray, R.C.; Singh, S.P.; Rai, A.K. Lactic acid bacteria in the functional food industry: Biotechnological properties and potential applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2024, 64, 10730–10748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkheir, K.; Centeno, J.; Zadi-Karam, H.; Karam, N.; Carballo, J. Potential technological interest of indigenous lactic acid bacteria from Algerian camel milk. Ital Journal Food Sci 2016, 28, 598. [Google Scholar]

- Khedid, K.; Faid, M.; Mokhtari, A.; Soulaymani, A.; Zinedine, A. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from the one humped camel milk produced in Morocco. Microbiol Res 2009, 164(1), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmeh, R.; Akbar, A.; Kishk, M.; Al-Onaizi, T.; Al-Azmi, A.; Al-Shatti, A.; Shajan, A.; Al-Mutairi, S.; Akbar, B. Distribution and antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria from raw camel milk. New Microbe New Infect 2019, 30, 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chentouf, H.F.; Rahli, F.; Benmechernene, Z.; Barros-Velazquez, J. 16S rRNA gene sequencing and MALDI TOF mass spectroscopy identification of Leuconostoc mesenteroides isolated from Algerian raw camel milk. J Genet Eng Biotechnol 2023, 21, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Esgueva, M.; Fernández-Simon, R.; Monforte-Cirac, M.L.; López-Calleja, A.I.; Fortuño, B.; Viñuelas-Bayon, J. Use of MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Daltonics) for identification of Mycobacterium species isolated directly from liquid medium. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2021, 39, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, M.; Ozpinar, H. Investigation of probiotic features of bacteria isolated from some food products. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg 2017, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Gantzias, C.; Lappa, I.K.; Aerts, M.; Georgalaki, M.; Manolopoulou, E.; Papadimitriou, K.; De Brandt, E.; Tsakalidou, E.; Vandamme, P. MALDI-TOF MS profiling of non-starter lactic acid bacteria from artisanal cheeses of the Greek island of Naxos. Int Journal Food Microbiol 2020, 323, 108586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zommara, M.; El-Ghaish, S.; Haertle, T.; Chobert, J-M. ; Ghanimah, M. Probiotic and technological characterization of selected Lactobacillus strains isolated from different Egyptian cheeses. BMC Microbiol 2023, 23, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, Y.; Del Rio, B.; Senouci, D.E; Redruello, B.; Martinez, B.; Ladero, V.; Kihal, M.; Alvarez, M.A. Polyphasic characterisation of non-starter lactic acid bacteria from Algerian raw Camel’s milk and their technological aptitudes. Food Technol Biotechnol 2020, 58, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fguiri, I.; Ziadi, M.; Rekaya, K.; Samira, A.; Khorchani, T. Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria strains from raw camel milk for potential use in the production of yogurt. J Food Sci Nutr 2017, 2017 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawaz, E.; Guesh, T.; Kebede, A.; Menkir, S. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria from camel milk and their technological properties to use as a starter culture. East Afr Journal Sci 2016, 10, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dinçer, E.; Kıvanç, M. Lipolytic activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Turkish pastırma. Anadolu Univ J Sci Technol C-Life Sci Biotechnol 2018, 7, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, Z.; Hatzikamari, M.; Georgakopoulos, P.; Yiangou, M.; Litopoulou-Tzanetaki, E.; Tzanetakis, N. Selection of dominant NSLAB from a mature traditional cheese according to their technological properties and in vitro intestinal challenges. J Food Sci 2012, 77, M298–M306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.; Medina, R.; Gonzalez, S.; Oliver, G. Esterolytic and lipolytic activities of lactic acid bacteria isolated from ewe’s milk and cheese. J Food Prot 2002, 65, 1997–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaburi, A.; Di Monaco, R.; Cavella, S.; Toldrá, F.; Ercolini, D.; Villani, F. Proteolytic and lipolytic starter cultures and their effect on traditional fermented sausages ripening and sensory traits. Food Microbiol 2008, 25, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuillemard, J.; Amiot, J.; Gauthier, S. Evaluation de l’activité protéolytique de bactéries lactiques par une méthode de diffusion sur plaque. Microbiol Alim Nutr 1986, 3, 327–332. [Google Scholar]

- Hassaïne, O.; Zadi-Karam, H. ; Karam, N-E.. Technologically important properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from raw milk of three breeds of Algerian dromedary (Camelus dromedarius). Afr J Biotechnol 2007, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.F.; Sarantinopoulos, P.; Tsakalidou, E.; De Vuyst, L. . The role and application of enterococci in food and health. Int J Food Microbiol 2006, 106, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassaïne, O.; Zadi-Karam, H.; Karam, N. . Phenotypic identification and technological properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from three breeds dromedary raw milks in south Algeria. Emir. J. Food Agric 2008, 20, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.; Prajapati, J. Food and health applications of exopolysaccharides produced by lactic acid bacteria. Adv Dairy Res 2013, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Angelin, J.; Kavitha, M. Exopolysaccharides from probiotic bacteria and their health potential. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 162, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korcz, E.; Varga, L. Exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria: Techno-functional application in the food industry. Trends in Food Sci Technol 2021, 110, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu. Y.; Zhou, T.; Tang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Probiotic potential and amylolytic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Chinese fermented cereal foods. Food Control 2020, 111, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Meena, K.K.; Panwar, N.L. ; Gupta, L; Joshi, M. Isolation, characterization, and probiotic profiling of amylolytic lactic acid bacteria from Sonadi sheep milk. Research Square V1. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkheir, K.; Centeno, J.; Zadi-Karam, H.; Karam, N.; Carballo, J. Potential technological interest of indigenous lactic acid bacteria from Algerian camel milk. Ital J Food Sci 2016, 28, 598. [Google Scholar]

- Gänzle, M.G. Lactic metabolism revisited: metabolism of lactic acid bacteria in food fermentations and food spoilage. Curr Opin Food Sci 2015, 2, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymerich, T.; Rodríguez, M.; Garriga, M.; Bover-Cid, S. Assessment of the bioprotective potential of lactic acid bacteria against Listeria monocytogenes on vacuum-packed cold-smoked salmon stored at 8° C. Food Microbiol 2019, 83, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkiene, E.; Lele, V.; Ruzauskas, M.; Domig, K.J.; Starkute, V.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Bartkevics, V.; Pugajeva, I.; Klupsaite, D.; Juodeikiene,G. Lactic acid bacteria isolation from spontaneous sourdough and their characterization including antimicrobial and antifungal properties evaluation. Microorganisms 2019, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddine, S.D.; Yasmine, S.; Fatima, G.; Amina, Z.; Battache, G.; Mebrouk, K. Antifungal and antibacterial activity of some lactobacilliisolated from camel’s milk biotope in the south of Algeria. J Microbiol Biotech Food Sci 2018, 8, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikodinoska, I.; Tabanelli, G.; Baffoni, L.; Gardini, F.; Gaggìa, F.; Barbieri, F.; Di Gioia, D. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from spontaneously fermented sausages: Bioprotective, technological and functional properties. Foods 2023, 12, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglińska,, A, Kołtuniak, A.; Motyl, I.; Berłowska, J.; Czyżowska A.; Cieciura-Włoch, W.; Okrasa, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Gutarowska, B.. Lactic acid bacteria as biocontrol agents against potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) pathogens. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 7763.

| C | Morphology | Gram | Catalase | Motility | Tetrads | Growth at 10°C | Growth at 15°C | Growth at 45°C | CO2 Production | 6.5% NaCl | pH 9.6 | Arginine (ADH) |

| BLC1 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC2 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | + | – | + | + | – |

| BLC3 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC4 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC5 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC6 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC7 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC8 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC9 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC10 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC11 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC12 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC13 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC14 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC15 | Coccus | + | – | – | + | + | ND | – | + | ND | – | – |

| BLC16 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC17 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC18 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC19 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC20 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC21 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC22 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC23 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC24 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC25 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC26 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | + | – | + | + | – |

| BLC27 | Coccus | + | – | – | + | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC28 | Rod | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC29 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC30 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| BLC31 | Coccus | + | – | – | – | + | ND | – | – | ND | – | – |

| Isolate | Identification Result | Score |

| BLC1 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.37 |

| BLC2 | Enterococcus italicus | 2.32 |

| BLC3 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.44 |

| BLC4 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.38 |

| BLC5 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.46 |

| BLC6 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.32 |

| BLC7 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.35 |

| BLC8 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.44 |

| BLC9 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.32 |

| BLC10 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.37 |

| BLC11 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.39 |

| BLC12 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.27 |

| BLC13 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.29 |

| BLC14 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.32 |

| BLC15 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 2.24 |

| BLC16 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.30 |

| BLC17 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.33 |

| BLC18 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.42 |

| BLC19 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.38 |

| BLC20 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.37 |

| BLC21 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.29 |

| BLC22 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.29 |

| BLC23 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.23 |

| BLC24 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.41 |

| BLC25 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.34 |

| BLC26 | Enterococcus italicus | 2.12 |

| BLC27 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.23 |

| BLC28 | Lactobacillus lactis | 2.32 |

| BLC29 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.27 |

| BLC30 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.37 |

| BLC31 | Lactococcus lactis | 2.29 |

| Strain | EPS Production1 | Amylase Production2 (cm) | Acetoin Production3 |

| BLC1 | – | – | + |

| BLC2 | – | – | + |

| BLC3 | + | – | – |

| BLC4 | – | – | – |

| BLC5 | – | – | – |

| BLC6 | – | – | + |

| BLC7 | – | – | – |

| BLC8 | + | – | – |

| BLC9 | – | – | + |

| BLC10 | – | – | + |

| BLC11 | – | – | – |

| BLC12 | + | – | – |

| BLC13 | – | – | – |

| BLC14 | – | – | – |

| BLC15 | ++ | – | – |

| BLC16 | – | – | – |

| BLC17 | – | – | – |

| BLC18 | – | – | – |

| BLC19 | – | – | + |

| BLC20 | – | – | + |

| BLC21 | + | – | – |

| BLC22 | + | – | + |

| BLC23 | – | 1.20 ± 0.14ᵃᵇ | + |

| BLC24 | – | – | + |

| BLC25 | – | – | + |

| BLC26 | – | – | + |

| BLC27 | – | – | – |

| BLC28 | – | – | + |

| BLC29 | + | 0.85 ± 0.07ᵇ | + |

| BLC30 | + | 1.35 ± 0.64ᵃ | + |

| BLC31 | +++ | – | – |

| Antibacterial activity1 | ||||||

| Indicator Strains | ||||||

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

Escherichia coli |

Salmonella enteritidis |

Bacillus cereus |

Listeria monocytogenes |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Enterobacter cloacae |

| 13.0 ± 1.4bcd | - | - | - | - | 8.0 ± 1.4bc | 7.0 ± 0b |

| 12.0 ± 1.4cd | - | 8.5 ± 0.7ab | - | 11 ± 5.7a | 8.0 ± 0bc | 8.5 ± 0.7ab |

| 11.0 ± 1.4cd | - | - | - | - | 7.5 ± 0.7bc | 9.5 ± 0.7a |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9.5 ± 0.7cd | - | - | - | - | 7.0 ± 0c | - |

| 15.0 ± 1.4bc | - | 7.0 ± 0c | - | - | 8.0 ± 1.4bc | 7.5 ± 0.7ab |

| 12.0 ± 1.4cd | - | - | - | - | - | 7.5 ± 0.7ab |

| 12.5 ± 0.7bcd | - | - | - | - | 8.5 ± 0.7abc | 8.0 ± 0ab |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | 9.5 ± 0.7a |

| 8.0 ± 1.4d | - | - | - | - | - | 9.0 ± 0ab |

| 12.0 ± 2.8cd | - | - | - | - | 9.5 ± 0.7ab | - |

| 8.5 ± 0.7d | - | - | - | - | 9.0 ± 0abc | 9.5 ± 0.7a |

| 12.0 ± 1.4cd | 7.5 ± 0.7b | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11.0 ± 1.4cd | 8.0 ± 1.4b | 8.0 ± 0bc | - | - | - | 8.0 ± 1.4ab |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | 8.5 ± 0.7b | 8.5 ± 0.7ab | - | - | 8.0 ± 1.4bc | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 13.5 ± 0.7bcd | 7.5 ± 0.7b | - | - | 9.0 ± 1.4a | - | - |

| 15.0 ± 1.4bc | - | 7.0 ± 0c | - | 9.0 ± 1.4a | - | - |

| 12.5 ± 0.7bcd | 8.0 ± 0b | 9.0 ± 1.4ab | - | 9.5 ± 0.7a | 10.5 ± 0.7a | 7.0 ± 0b |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 13.5 ± 2.1bcd | - | - | - | 8.5 ± 0.7a | 8.0 ± 0bc | 8.5 ± 0.7ab |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15.5 ± 4.9bc | 9.0 ± 0b | - | 8.5 ± 0.7a | 9.0 ± 1.4a | 9.5 ± 0.7ab | 8.5 ± 0.7ab |

| 12.5 ± 2.1bcd | 9.0 ± 1.4b | - | 9.0 ± 1.4a | 8.5 ± 2.1a | 7.5 ± 0.7bc | 8.0 ± 1.4ab |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 22.0 ± 2.8a | - | 8.5 ± 0.7ab | - | - | - | - |

| 13.5 ± 0.7e | 14.5 ± 2.1a | - | - | 10.5 ± 0.7b | - | 7.0 ± 0b |

| 18.5 ± 2.1ab | 7.5 ± 0.7b | 9.5 ± 0.7a | - | - | - | 9.0 ± 1.4ab |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).