Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

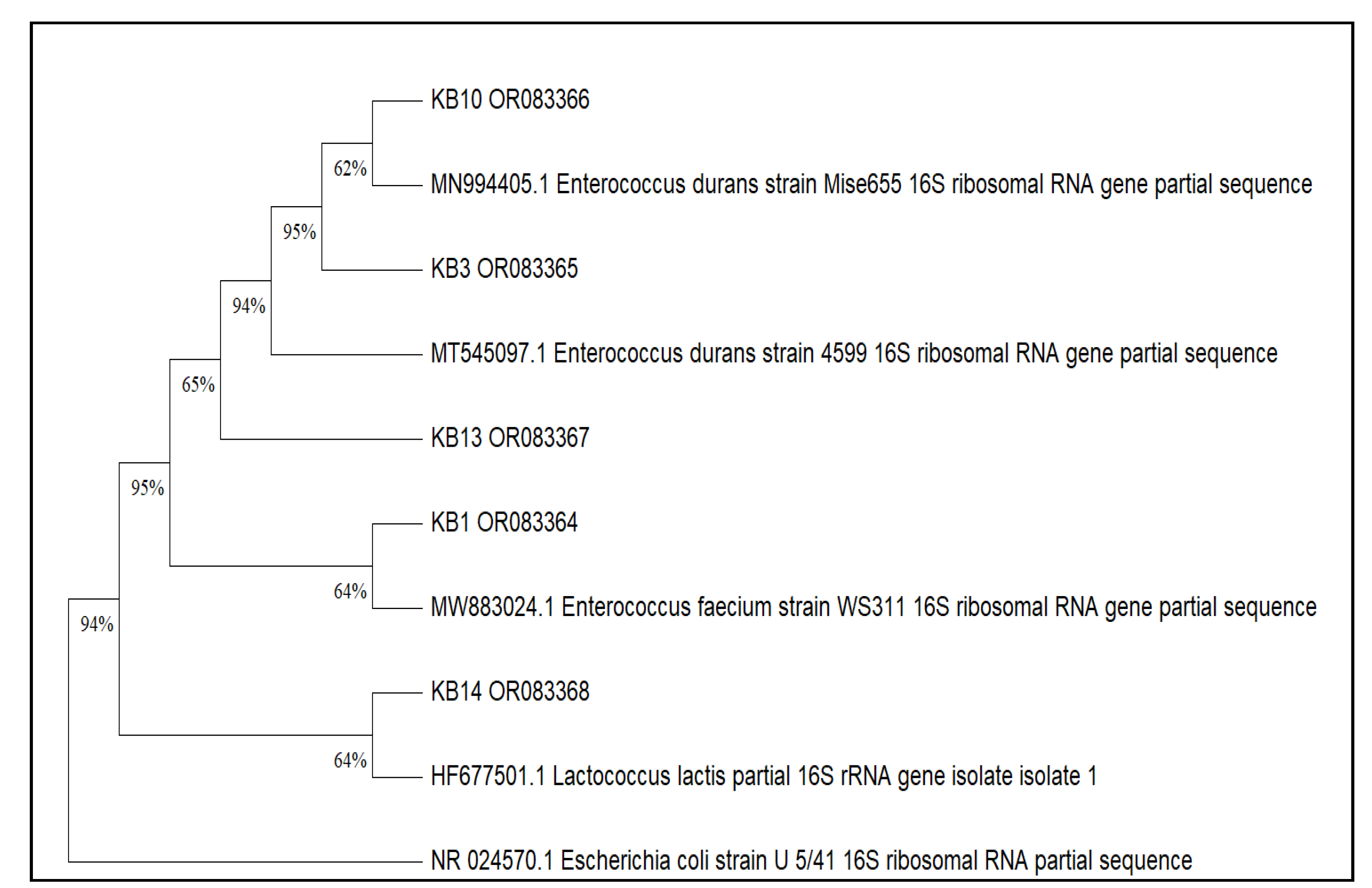

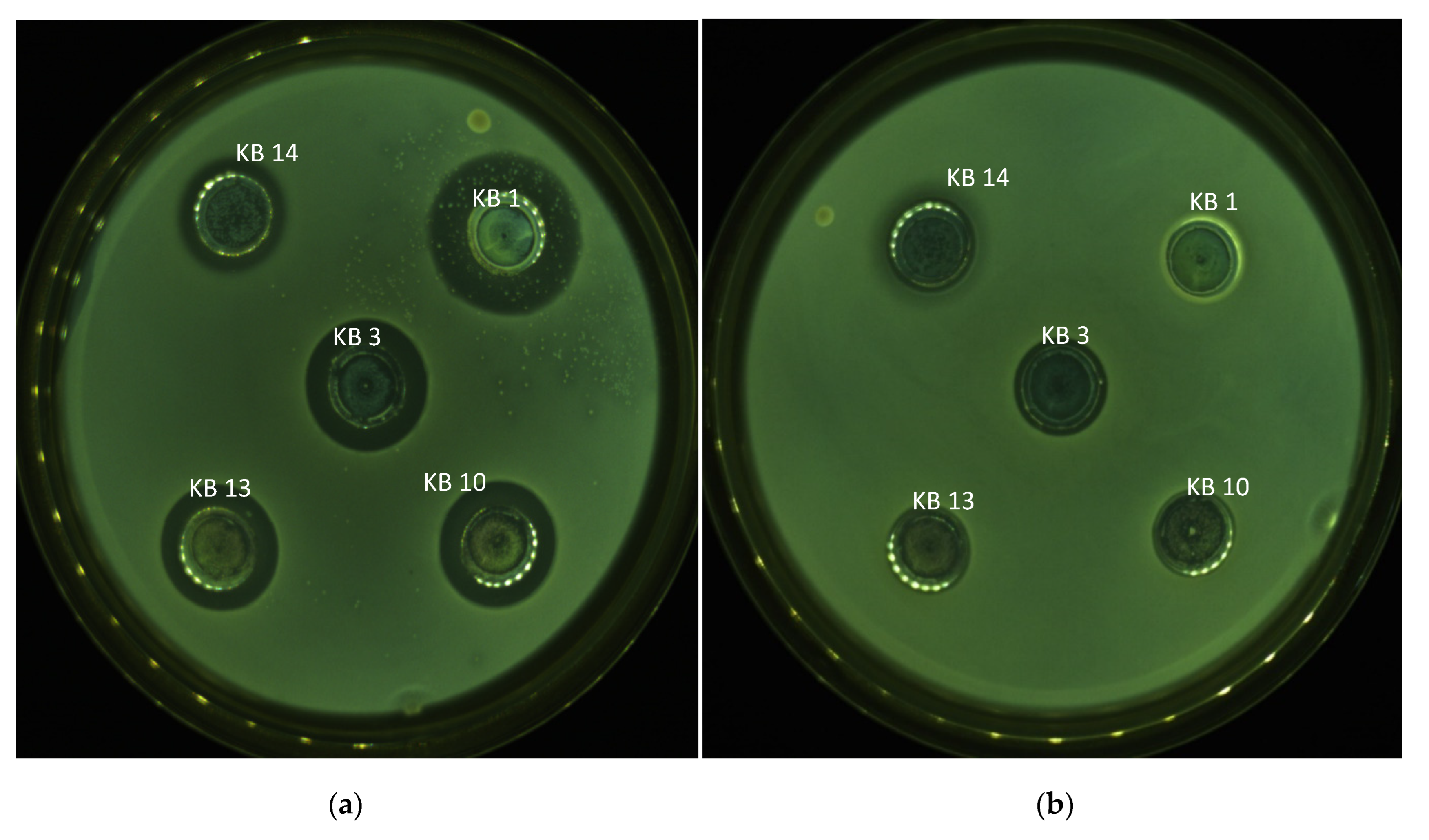

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are increasingly recognized for their role in food biopreservation due to their ability to synthesize antimicrobial compounds. Milk naturally harbors a wide variety of lactic acid bacteria, offering a promising source for identifying strains with biopreservative potential. This study investigated the antagonistic effects, safety characteristics, and technological properties of LAB strains isolated from traditionally fermented milk. Thirty-two dairy samples were analyzed, and the resulting LAB isolates were screened for inhibitory activity against Listeria monocytogenes CECT 4032 and Staphylococcus aureus CECT 976 using agar spot and well diffusion assays. All tested strains exhibited strong antimicrobial effects, with particularly notable inhibition of L. monocytogenes. After phenotypic screening, five representative isolates were selected for molecular identification and further assessment of safety-related attributes, functional capabilities, auto- and co-aggregation properties 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed that four strains belonged to the genus Enterococcus, specifically, one E. faecium and three E. durans, while one was classified as a Lactococcus species. Moreover, none of the strains showed proteolytic or lipolytic activities which highlights their potential use in dairy fermentation processes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of LAB from Milk

2.2. Screening for Bacteriocinogenic LAB

2.3. Indicator Pathogens and Antimicrobial Spectrum

2.4. Stability of Bacteriocin-like Activity After Exposure to Proteolytic Enzymes

2.5. Identification of Antagonistic LAB

2.5.1. Phenotypic and Biochemical Identification

2.5.2. Molecular Identification (16S rRNA)

2.6. Technological Assessment of LAB Strains

2.6.1. Proteolytic and Lipolytic Activities

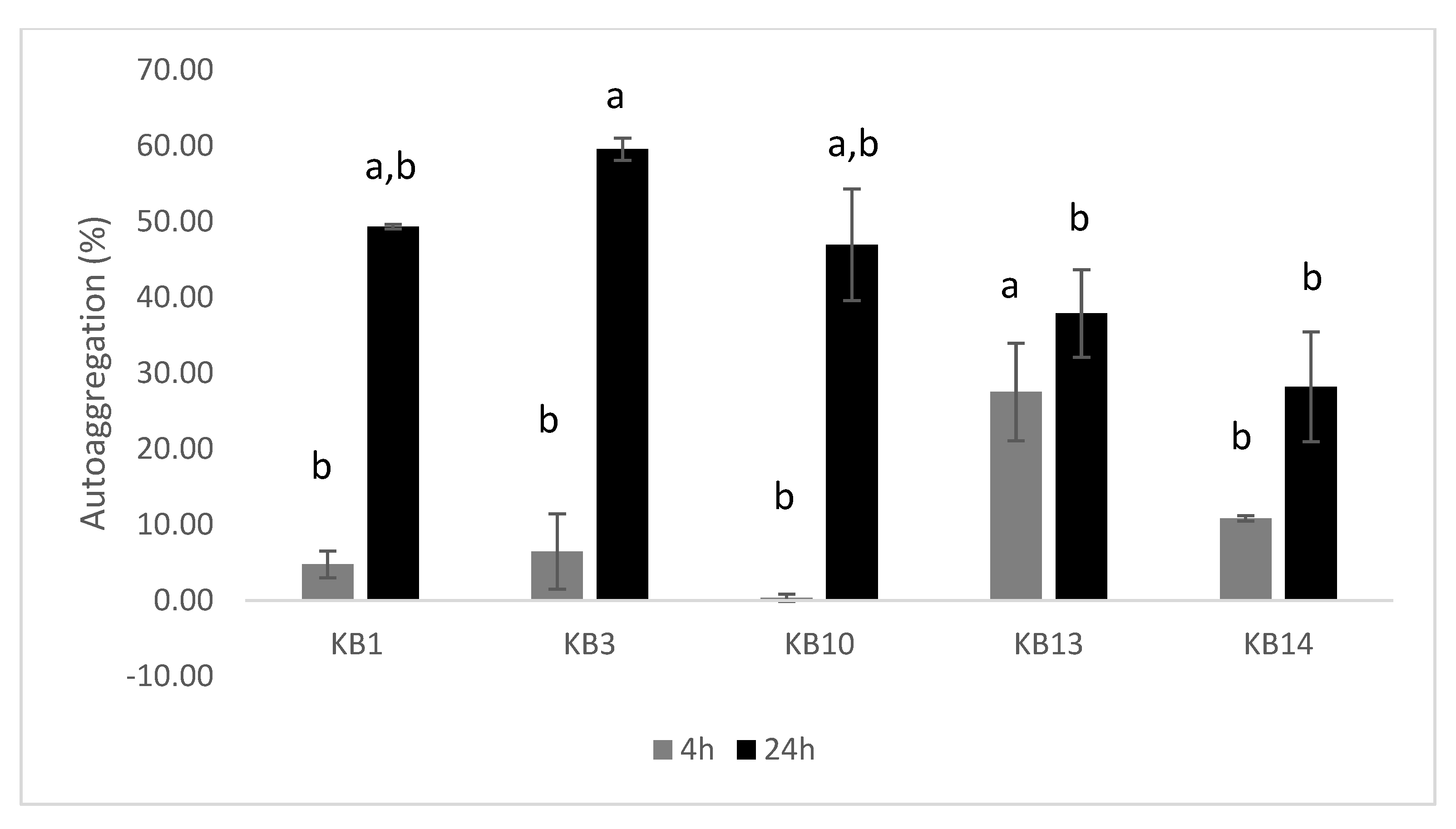

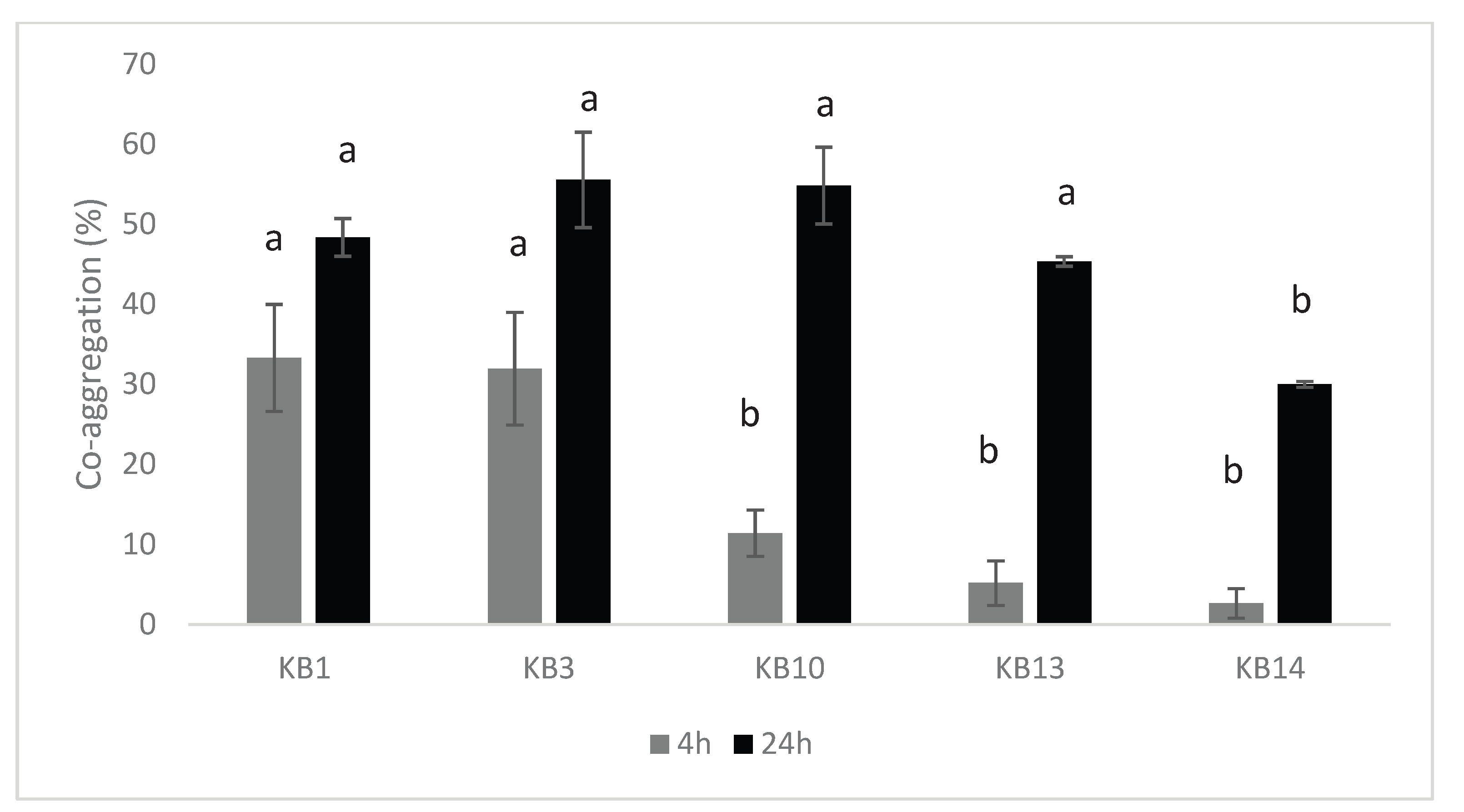

2.6.2. Aggregation Abilities

2.7. Evaluation of Safety-Related Traits

2.7.1. Hemolytic Activity

2.7.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility

2.7.3. Gelatinase Activity and Biogenic Amine Production

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bacteriocinogenic Potential of LAB Strains

3.2. Aggregation Capacity of LAB Isolates

4. Discussion

4.1. Antimicrobial Potential and Safety Assessment of LAB Strains

4.2. Proteolytic and Lipolytic Activities

4.3. Auto-Aggregation and Co-Aggregation Capabilities of LAB Strains

4.4. Protein-Based Features of Antimicrobial Substances from LAB

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| MRS | De Man, Rogosa and Sharpe |

| BEA | Bile Esculin Agar |

| BHI | Brain Heart Infusion |

| MHA | Mueller-Hinton Agar |

| TSA | Tryptic Soy Agar |

Appendix A

| Strains | KB1 | KB2 | KB3 | KB4 | KB5 | KB6 | KB7 | KB8 | KB9 | KB10 | KB11 | KB12 | KB13 | KB14 | KB15 | KB16 | KB17 | KB18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes CECT 7467 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 5725 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 935 | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| S. aureus CECT 976 | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| E. coli CECT 4076 | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | * | * | * | * | * | * | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| B. subtilis DSMZ 6633 | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | * | * | * | * | * | * | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| S. enterica CECT 704 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | * | * | * | * | * | * | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| P. aeruginosa CECT 118 | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | * | * | * | * | * | * | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Strains | KB1 | KB2 | KB3 | KB4 | KB5 | KB6 | KB7 | KB8 | KB9 | KB10 | KB11 | KB12 | KB13 | KB14 | KB15 | KB16 | KB17 | KB18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes CECT 7467 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 5725 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 935 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S. aureus CECT 976 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| E. coli CECT 4076 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| B. subtilis DSMZ 6633 | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| S. enterica CECT 704 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| P. aeruginosa CECT 118 | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

References

- Maky, M.A., Ishibashi, N., Gong, X., Sonomoto, K., Zendo, T. Distribution of Bacteriocin-like Substance-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria in Egyptian Sources. Appl Microbiol 2025, 5. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Sieiro, P., Montalbán-López, M., Mu, D., Kuipers, O.P. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria: extending the family. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 2939-2951. [CrossRef]

- Karapetyan, K., Huseynova, N., Arutjunyan, R., Tkhruni, F., Haertle, T. Perspective of using new strains of lactic acid bacteria for biopreservation. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip 2010, 24, 460-464. [CrossRef]

- Zanzan, M., Achemchem, F., Hamadi, F., Latrache, H., Elmoslih, A., Mimouni, R. Anti-adherence activity of monomicrobial and polymicrobial food-derived Enterococcus spp. biofilms against pathogenic bacteria. Curr Microbiol 2023, 80, 216. [CrossRef]

- De Martinis, E.C.P., Freitas, F.Z. Screening of lactic acid bacteria from Brazilian meats for bacteriocin formation. Food Control 2003, 14, 197-200. [CrossRef]

- Ortolani, M.B.T., Moraes, P.M., Perin, L.M., Viçosa, G.N., Carvalho, K.G., Silva Júnior, A., Nero, L.A. Molecular identification of naturally occurring bacteriocinogenic and bacteriocinogenic-like lactic acid bacteria in raw milk and soft cheese. J Dairy Sci 2010, 93, 2880-2886. [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, A., Abriouel, H., López, R.L., Omar, N.B. Bacteriocin-based strategies for food biopreservation. Int J Food Microbiol 2007, 120, 51-70. [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.H., Zendo, T., Sonomoto, K. Novel bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria (LAB): various structures and applications. Microb Cell Fact 2014, 13, S3. [CrossRef]

- Bintsis, T. Yeasts in different types of cheese. AIMS microbiol 2021, 7, 447-470. [CrossRef]

- Giraffa, G. Lactic Acid Bacteria: Enterococcus in Milk and Dairy Products☆. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences (Third Edition), P.L.H. McSweeney and J.P. McNamara, Editors, Academic Press: Oxford, Country, 2022, p. 151-159. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, S., Imran, M., Hassan, M.N., Iqbal, M., Zafar, Y., Hafeez, F.Y. Potential of bacteriocinogenic Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis inhabiting low pH vegetables to produce nisin variants. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2014, 59, 204-210. [CrossRef]

- Kondrotiene, K., Kasnauskyte, N., Serniene, L., Gölz, G., Alter, T., Kaskoniene, V., Maruska, A.S., Malakauskas, M. Characterization and application of newly isolated nisin producing Lactococcus lactis strains for control of Listeria monocytogenes growth in fresh cheese. LWT 2018, 87, 507-514. [CrossRef]

- Foulquié Moreno, M.R., Sarantinopoulos, P., Tsakalidou, E., De Vuyst, L. The role and application of enterococci in food and health. Int J Food Microbiol 2006, 106, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Mancini, L., Carbone, S., Calabrese, F.M., Celano, G., De Angelis, M. Isolation and characterization from raw milk of Enterocin B-producing Enterococcus faecium: A potential dairy bio-preservative agent. Appl Food Res 2025, 5, 100857. [CrossRef]

- Achemchem, F., Martínez-Bueno, M., Abrini, J., Valdivia, E., Maqueda, M. Enterococcus faecium F58, a bacteriocinogenic strain naturally occurring in Jben, a soft, farmhouse goat’s cheese made in Morocco. J Appl Microbiol 2005, 99, 141-150. [CrossRef]

- Ghrairi, T., Manai, M., Berjeaud, J.M., Frère, J. Antilisterial activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from rigouta, a traditional Tunisian cheese. J Appl Microbiol 2004, 97, 621-628. [CrossRef]

- Perin, L.M., Nero, L.A. Antagonistic lactic acid bacteria isolated from goat milk and identification of a novel nisin variant Lactococcus lactis. BMC Microbiol 2014, 14, 36. [CrossRef]

- Elotmani, F., Revol-Junelles, A.-M., Assobhei, O., Millière, J.-B. Characterization of anti-Listeria monocytogenes bacteriocins from Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, and Lactococcus lactis strains isolated from Raïb, a moroccan traditional fermented milk. Curr Microbiol 2002, 44, 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Achemchem, F., Cebrián, R., Abrini, J., Martínez-Bueno, M., Valdivia, E., Maqueda, M. Antimicrobial characterization and safety aspects of the bacteriocinogenic Enterococcus hirae F420 isolated from Moroccan raw goat milk. Can J Microbiol 2012, 58, 596-604. [CrossRef]

- Elidrissi, A., Ezzaky, Y., Boussif, K., Achemchem, F. Isolation and characterization of bioprotective lactic acid bacteria from Moroccan fish and seafood. Braz J Microbiol 2023, 54, 2117-2127. [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, Ç.B., Duran, M. Isolation and characterization of aroma producing lactic acid bacteria from artisanal white cheese for multifunctional properties. LWT 2021, 150, 112053. [CrossRef]

- Zanzan, M., Ezzaky, Y., Achemchem, F., Hamadi, F., Amzil, K., Latrache, H. Bacterial biofilm formation on stainless steel: exploring the capacity of Enterococcus spp. isolated from dairy products on AISI 316 L and AISI 304 L surfaces. Biologia 2024, 79, 1539-1551. [CrossRef]

- Angmo, K., Kumari, A., Savitri, Bhalla, T.C. Probiotic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented foods and beverage of Ladakh. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2016, 66, 428-435. [CrossRef]

- Doménech-Sánchez, A., Laso, E., Pérez, M.J., Berrocal, C.I. Microbiological levels of randomly selected food contact surfaces in hotels located in Spain during 2007–2009. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2011, 8, 1025-1029. [CrossRef]

- CLSI, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, in CLSI supplement M100. 2020: Wayne, PA.

- Mazlumi, A., Panahi, B., Hejazi, M.A., Nami, Y. Probiotic potential characterization and clustering using unsupervised algorithms of lactic acid bacteria from saltwater fish samples. Sci. Rep 2022, 12, 11952. [CrossRef]

- Amidi-Fazli, N., Hanifian, S. Biodiversity, antibiotic resistance and virulence traits of Enterococcus species in artisanal dairy products. Int Dairy J 2022, 129, 105287. [CrossRef]

- Maijala, R.L. Formation of histamine and tyramine by some lactic acid bacteria in MRS-broth and modified decarboxylation agar. Lett Appl Microbiol 1993, 17, 40-43. [CrossRef]

- Benkerroum, N., Oubel, H., Zahar, M., Dlia, S., Filali-Maltouf, A. Isolation of a bacteriocin-producing Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and application to control Listeria monocytogenes in Moroccan jben. J Appl Microbiol 2000, 89, 960-968. [CrossRef]

- Simova, E.D., Beshkova, D.B., Dimitrov Zh, P. Characterization and antimicrobial spectrum of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Bulgarian dairy products. J Appl Microbiol 2009, 106, 692-701. [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, V., Dornellas, W., Perin, L., Pieri, F., Franco, B., Todorov, S., Nero, L. Genetic diversity and some aspects of antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from goat milk. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2015. [CrossRef]

- Schittler, L., Perin, L.M., de Lima Marques, J., Lando, V., Todorov, S.D., Nero, L.A., da Silva, W.P. Isolation of Enterococcus faecium, characterization of its antimicrobial metabolites and viability in probiotic Minas Frescal cheese. J Food Sci Technol 2019, 56, 5128-5137. [CrossRef]

- Kouhi, F., Mirzaei, H., Nami, Y., Khandaghi, J., Javadi, A. Potential probiotic and safety characterisation of enterococcus bacteria isolated from indigenous fermented motal cheese. Int Dairy J 2022, 126, 105247. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E., González, B., Gaya, P., Nuñez, M., Medina, M. Diversity of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria isolated from raw milk. Int Dairy J 2000, 10, 7-15. [CrossRef]

- González, L., Sandoval, H., Sacristán, N., Castro, J.M., Fresno, J.M., Tornadijo, M.E. Identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Genestoso cheese throughout ripening and study of their antimicrobial activity. Food Control 2007, 18, 716-722. [CrossRef]

- Chahad, O.B., El Bour, M., Calo-Mata, P., Boudabous, A., Barros-Velàzquez, J. Discovery of novel biopreservation agents with inhibitory effects on growth of food-borne pathogens and their application to seafood products. Res Microbiol 2012, 163, 44-54. [CrossRef]

- Akabanda, F., Owusu-Kwarteng, J., Tano-Debrah, K., Parkouda, C., Jespersen, L. The use of lactic acid bacteria starter culture in the production of Nunu, a spontaneously fermented milk product in Ghana. Int J Food Sci 2014, 2014, 721067. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, M.A., Muller, M.P., Berghahn, E., de Souza, C.F.V., Granada, C.E. New enterococci isolated from cheese whey derived from different animal sources: High biotechnological potential as starter cultures. LWT 2020, 131, 109808. [CrossRef]

- Fugaban, J.I.I., Holzapfel, W.H., Todorov, S.D. Probiotic potential and safety assessment of bacteriocinogenic Enterococcus faecium strains with antibacterial activity against Listeria and vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Curr Res Microb Sci 2021, 2, 100070. [CrossRef]

- Slyvka, I., Tsisaryk, O., Musii, L., Kushnir, I., Koziorowski, M., Koziorowska, A. Identification and Investigation of properties of strains Enterococcus spp. Isolated from artisanal Carpathian cheese. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2022, 39, 102259. [CrossRef]

- Sonei, A., Edalatian Dovom, M.R., Yavarmanesh, M. Evaluation of probiotic, safety, and technological properties of bacteriocinogenic Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis strains isolated from lighvan and koozeh cheeses. Int Dairy J 2024, 148, 105807. [CrossRef]

- Kazancıgil, E., Demirci, T., Öztürk-Negiş, H.İ., Akın, N. Isolation, technological characterization and in vitro probiotic evaluation of Lactococcus strains from traditional Turkish skin bag Tulum cheeses. Ann Microbiol 2019, 69, 1275-1287. [CrossRef]

- Mercha, I., Lakram, N., Kabbour, M., Bouksaim, M., Zkhiri, F., El Maadoudi, E.H. Probiotic and technological features of Enterococcus and Weissella isolates from camel milk characterised by an Argane feeding regimen. Arch Microbiol 2020, 202. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z., Uddin, M.E., Rahman, M.T., Islam, M.A., Harun-ur-Rashid, M. Isolation and characterization of dominant lactic acid bacteria from raw goat milk: Assessment of probiotic potential and technological properties. Small Rumin Res 2021, 205, 106532. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T., Wang, L., Guo, Z., Li, B. Technological characterization and antibacterial activity of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris strains for potential use as starter culture for cheddar cheese manufacture. Food Sci Technol 2022, 42, e13022. [CrossRef]

- Allam, M.G.M., Darwish, A.M.G., Ayad, E.H.E., Shokery, E.S., Darwish, S.M. Lactococcus species for conventional Karish cheese conservation. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2017, 79, 625-631. [CrossRef]

- Azat, R., Liu, Y., Li, W., Kayir, A., Lin, D., Zhou, W.-W., Zheng, X. Probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditionally fermented Xinjiang cheese. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2016, 17. [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M., Abushelaibi, A., Al-Mahadin, S., Enan, M., El-Tarabily, K., Shah, N. In-vitro investigation into probiotic characterisation of Streptococcus and Enterococcus isolated from camel milk. LWT 2018, 87, 478-487. [CrossRef]

- Ben Braïek, O., Morandi, S., Cremonesi, P., Smaoui, S., Hani, K., Ghrairi, T. Safety, potential biotechnological and probiotic properties of bacteriocinogenic Enterococcus lactis strains isolated from raw shrimps. Microb Pathog 2018, 117, 109-117. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.C.S., Casarotti, S.N., Todorov, S.D., Penna, A.L.B. Probiotic potential and safety of enterococci strains. Ann Microbiol 2019, 69, 241-252. [CrossRef]

- Krausova, G., Hyrslova, I., Hynstova, I. In vitro evaluation of adhesion capacity, hydrophobicity, and auto-aggregation of newly isolated potential probiotic strains. Fermentation 2019, 5, 100. [CrossRef]

- Furtado, D.N., Todorov, S.D., Landgraf, M., Destro, M.T., Franco, B.D. Bacteriocinogenic Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis DF04Mi isolated from goat milk: Application in the control of Listeria monocytogenes in fresh Minas-type goat cheese. Braz J Microbiol 2015, 46, 201-6. [CrossRef]

- Beshkova, D., Frengova, G. Bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria: Microorganisms of potential biotechnological importance for the dairy industry. Engineering in Life Sciences 2012, 12, 419-432. [CrossRef]

| Strains | Gram Staining | Catalase Activity | Growth Ability at 10 °C |

Growth Ability at 45 °C |

Growth Ability in 4% NaCl |

Growth Ability in 6,5%NaCl |

Growth in Bile-Esculin-Azide Agar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KB1 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB2 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB3 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB4 | + | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| KB5 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB6 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB7 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB8 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB9 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB10 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB11 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB12 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB13 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB14 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB15 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB16 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB17 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| KB18 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| Selected strains | Origin of isolate | Identification | Number of accessions |

| KB1 | Goat’s milk |

E. faecium | OR083364 |

| KB3 | E. durans | OR083365 | |

| KB10 | E. durans | OR083366 | |

| KB13 | E. durans | OR083367 | |

| KB14 | L. lactis | OR083368 |

| Antibiotic | KB1 | KB3 | KB10 | KB13 | KB14 |

| Vancomycin | I | S | S | I | S |

| Fosfomycin | S | S | S | S | S |

| Penicillin G | R | S | S | S | S |

| Ampicillin | I | S | S | S | S |

| Ciprofloxacin | I | S | I | I | I |

| Fusidic Acid | I | S | S | S | I |

| Streptomycin | R | R | I | I | I |

| Gentamicin | R | S | I | I | I |

| Chloramphenicol | S | S | S | R | S |

| Netilmicin | R | S | I | I | I |

| Erythromycin | R | S | S | S | S |

| Tetracycline | S | S | S | S | S |

| Kanamycin | R | S | I | I | I |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).