Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

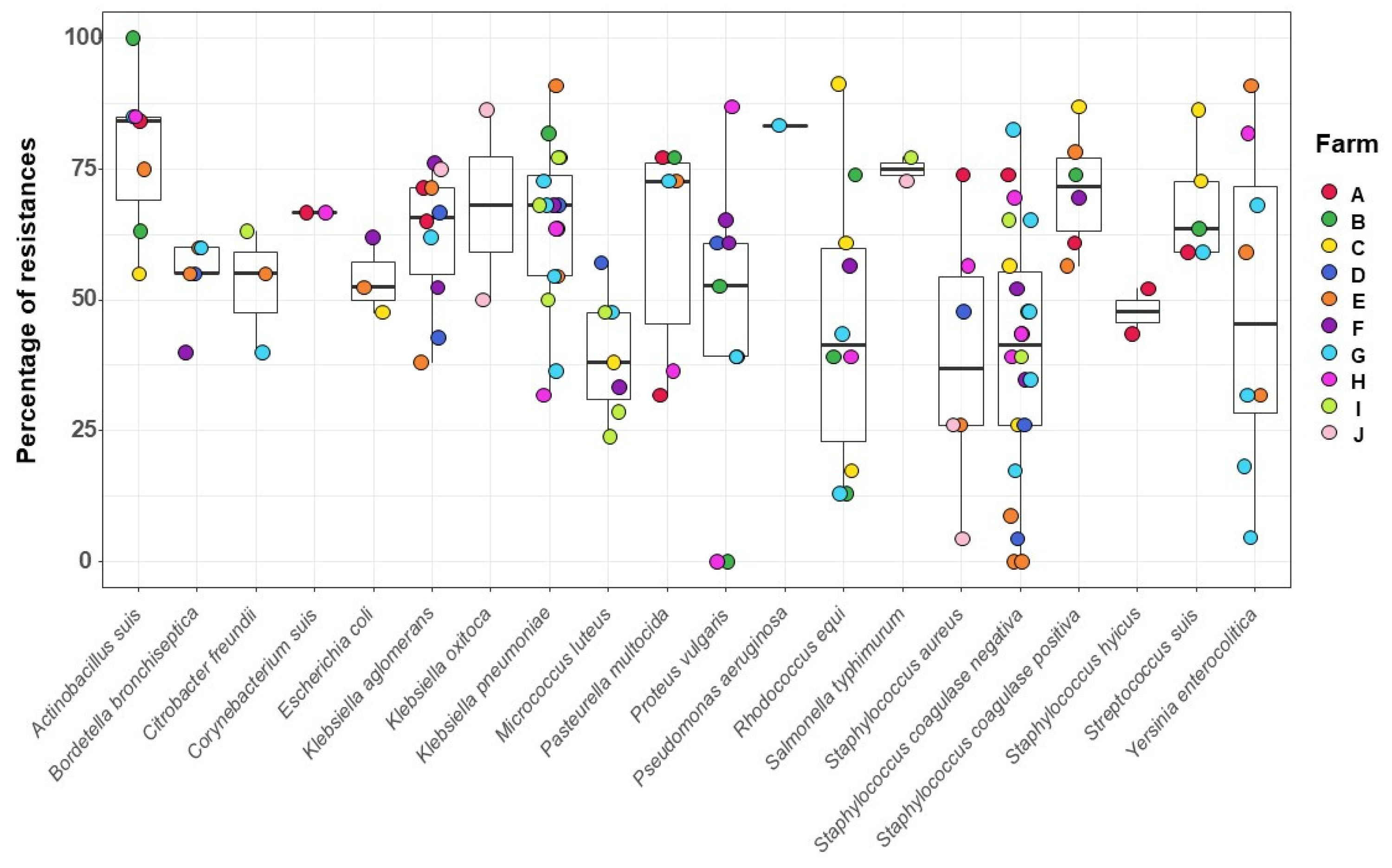

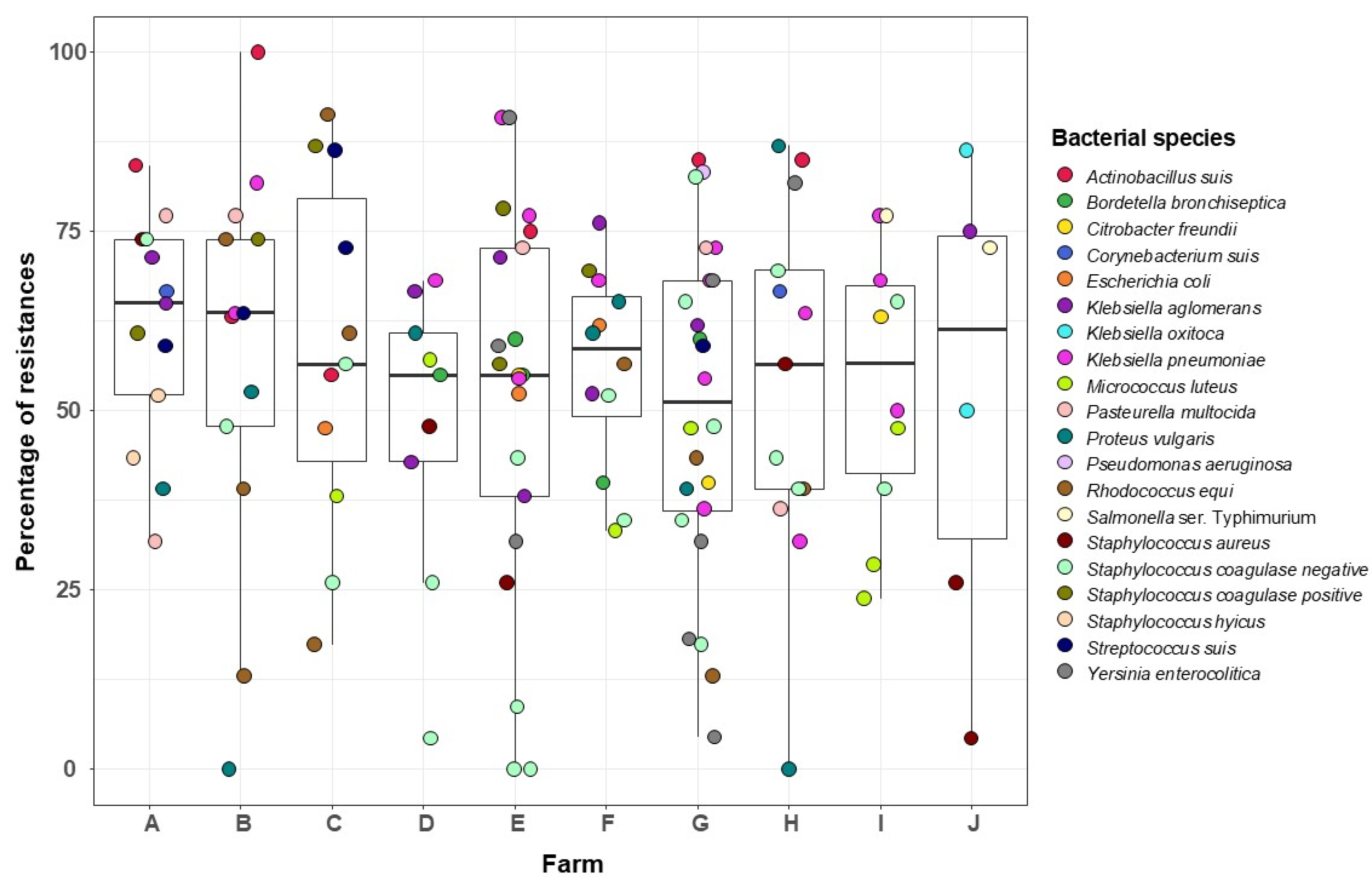

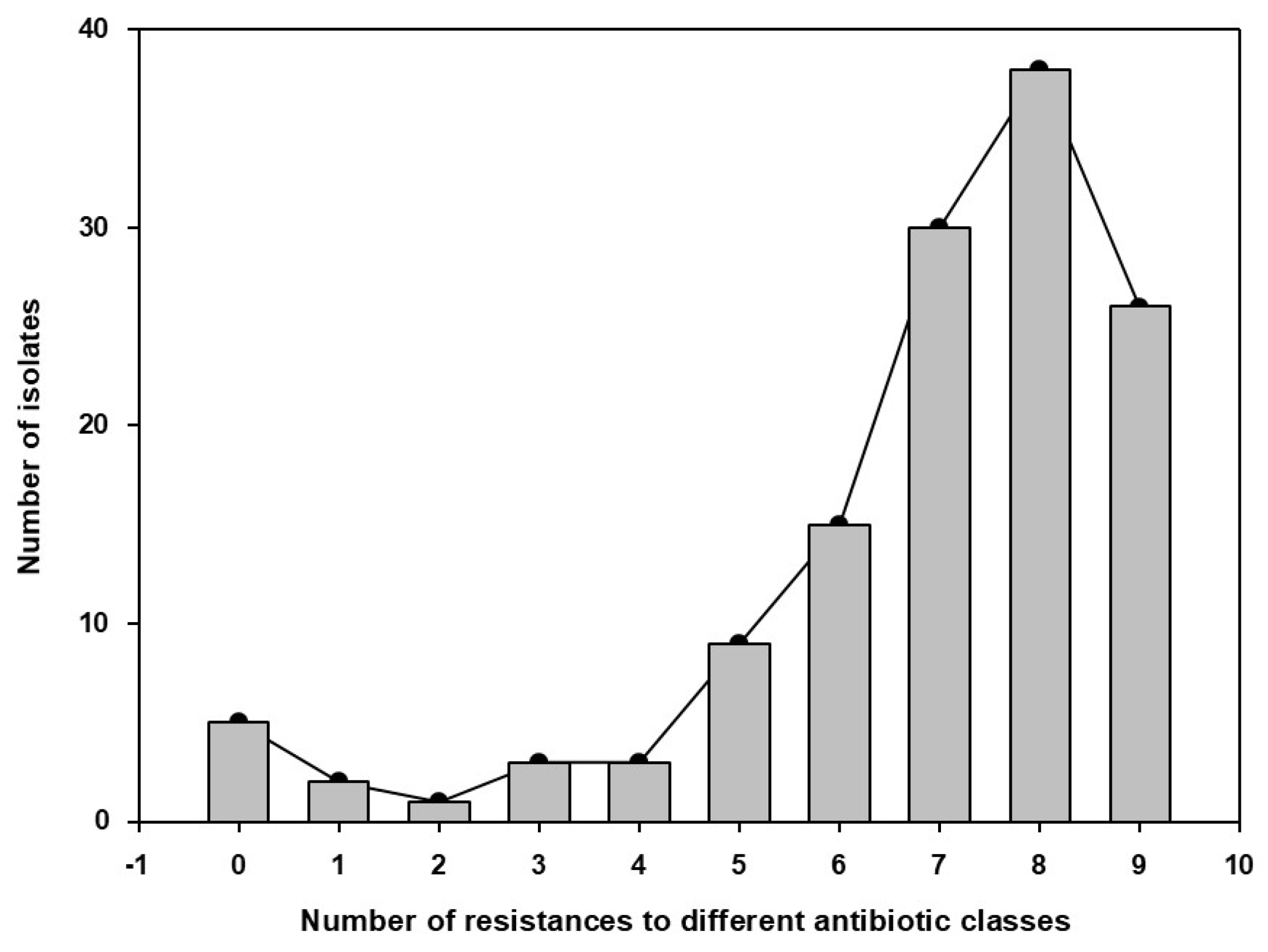

Antimicrobial resistance is a universal threat and is leading to a new awareness of antimicrobial use. The colonization of tissues by some microorganisms carrying resistance genes may pose a risk of spreading resistance to pathogens. Antimicrobials may induce an unstable microbiome that compromises the animal's immunity. Indeed, dysbiosis has been linked to many alterations in the immune response. Here, we isolated bacterial colonizers from the nasal microbiota of sows to describe the phenotypic resistance profile on different health managements. One hundred and thirty-two strains isolated from 50 nasal swabs collected from sows were tested against up to 23 antimicrobial agents by disk diffusion. Overall, the nasal communities showed 55% antimicrobial resistance (1605/2888 tests). Resistance was detected for all tested antimicrobials. The antimicrobial showing higher rate of resistance was bacitracin (92%), while the lowest was found in the aminoglycosides. Actinobacillus suis was one of the species with highest rate of resistance. The time and number of drugs used in feed influenced the resistance rate in the isolates. Vaccination was confirmed as a strategic protocol for disease control Studies on antimicrobial resistance in commensals may allow the identification of microorganisms to be used in surveillance and may constitute a tool for evaluating strategies to reduce antimicrobial use in pig herds.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Sampling, Swine Farms and Sows

2.3. Biosecurity Data Collection

2.4. DNA Extraction and PCR Assays

2.5. Culture and Bacterial Isolation

2.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Swine Farms and Sows’ Health Management

| Farm | AMB Agents | Vaccines | Production Type |

| A | AMO, CLI, TET, ENO, OXY | M. hyopneumoniae, circovirus, P. multocida, S. ser. Typhimurium | One-site-herd: piglet unit production |

| B | AMO, FLF, PEN | M. hyopneumoniae, circovirus, G. parasuis, S. suis. | One-site-herd: piglet unit production |

| C | AMO, FLF | P. multocida, B. bronchiseptica, G. parasuis, S. ser. Typhimurium, E. coli. | Two-site-herd: piglet and gilt and young boar production |

| D | AMO, FLF | G. parasuis | One-site-herd: piglet unit production |

| E | AMO | None | Farrow-to-finish: piglet to hog-finished production |

| F | AMO, FLF, PEN | P. multocida, S. ser. Typhimurium, S. suis. | One-site-herd: piglet unit production |

| G | AMO | None | Farrow-to-finish: piglet to hog-finished production |

| H | AMO, FLF | M. hyopneumoniae, circovirus, P. multocida, S. ser. Typhimurium, S. suis | One-site-herd: piglet unit production |

| I | AMO, FLF, TYL | M. hyopneumoniae, circovirus, P. multocida, G. parasuis, S. ser. Typhimurium | One-site-herd: piglet unit production |

| J | AMO, CLI | P. multocida, G. parasuis | Farrow-to-finish: piglet to hog-finished production |

3.2. Lung Lesions and Pathogen Detection

3.3. Bacterial Isolates from the Sows` Nasal Microbiota and Resistance Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prescott, JF. History and current use of antimicrobial drugs in veterinary medicine. Microbiol Spectr 2017, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeon O, Kibe LW. Antimicrobial Drug Resistance and Antimicrobial Resistant Threats. Phys Assist Clin 2023, 8, 411–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson NT, Kitzenberg DA, Kao DJ. Persister-mediated emergence of antimicrobial resistance in agriculture due to antibiotic growth promoters. AIMS Microbiol 2023, 9, 738–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letek, M. Alexander Fleming. The discoverer of the antibiotic effects of penicillin. Front Young Minds 2020, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012, 18, 268–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D. Selection and evolution of resistance antimicrobial drugs. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 521–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collignon PJ, McEwen SA. One Health—its importance in helping to better control antimicrobial resistance. Trop Med Infect Dis 2019, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam MA, Al-Amin MY, Salam MT, Pawar JS, Akhter N, Rabaan AA, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Hurtado M, Barba-Vidal E, Maldonado J, Aragon V. Update on Glässer’s disease: how to control the disease under restrictive use of antimicrobials. Vet Microbiol 2020, 242, 108595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra MC, Moreno LZ, Dias RA, Moreno AM. Antimicrobial Use in Brazilian Swine Herds: Assessment of Use and Reduction Examples. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman NEM, Van Dijk MAM, Broens EM, Wagenaar JA, Heederik DJJ, Van Geijlswijk IM. Quantifying antimicrobial use in Dutch companion animals. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdinand AS, Coppo MJC, Howden BP, Browning GF. Tackling antimicrobial resistance by integrating One Health and the Sustainable Development Goals. BMC Glob Public Health 2023, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirolo M, Espinosa-Gongora C, Bogaert D, Guardabassi L. The porcine respiratory microbiome: recent insights and future challenges. Anim Microbiome 2021, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Flores G, Pickard JM, Núñez G. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance: mechanisms and regulation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Fuertes M, Sibila M, Franzo G, Obregon-Gutierrez P, Illas F, Correa-Fiz F, Aragón V. Ceftiofur treatment of sows results in long-term alterations in the nasal microbiota of the offspring that can be ameliorated by inoculation of nasal colonizers. Anim Microbiome 2023, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Fiz F, Gonçalves JMS, Illas F, Aragón V. Antimicrobial removal on piglets promotes health and higher bacterial diversity in the nasal microbiota. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgamal Z, Singh P, Geraghty P. The upper airway microbiota, environmental exposures, inflammation, and disease. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan Z, Liu J, Zhang Y, Chen S, Ma J, Dong W, Wu Z, Yao H. A novel integrative conjugative element mediates the transfer of multi-drug resistance between Streptococcus suis strains of different serotypes. Vet Microbiol 2019, 229, 110–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Nishino K, Roberts MC, Tolmasky M, Aminov RI, Zhang L. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Front Microbiol 2015, 6, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Ning Y, Zhang Z, Song L, Qiu H, Gao H. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus suis strains isolated from clinically healthy sows in China. Vet Microbiol 2008, 131, 386–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebret B, Čandek-Potokar M. Review: Pork quality attributes from farm to fork. Part I. Carcass and fresh meat. Animal. 2022, 16 (Suppl 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhilegaonkar KN, Kolhe RP, Kumar MS. Good animal husbandry practices. In: Encyclopedia of Food Safety. 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2024. p. 407–15. [CrossRef]

- Albernaz-Gonçalves R, Antillón GO, Hötzel MJ. Linking Animal Welfare and Antibiotic Use in Pig Farming-A Review. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselani, K. Resíduos de medicamentos veterinários em alimentos de origem animal. Arq Cienc Vet Zool UNIPAR 2014, 17, 189–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância das Doenças Transmissíveis. Plano de ação nacional de prevenção e controle da resistência aos antimicrobianos no âmbito da saúde única 2018-2022 (PAN-BR) [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Jun 8]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/.

- Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento. Instrução Normativa SDA/MAPA nº113 de 16 de dezembro de 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sanidade-animal-e-vegetal/saude-animal/programas-de-saude-animal/sanidade-suidea/legislacao-suideos/2020IN113de16dedezembroBPMeBEAgranjasdesunoscomerciais.pdf/view.

- Guardabassi L, Apley M, Olsen JE, Toutain PL, Weese S. Optimization of antimicrobial treatment to minimize resistance selection. Microbiol Spectr 2018, 6, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brombilla T, Ogata RA, Nassar AFC, Cardoso MV, Ruiz VLA, Fava CD. Effect of bacterial agents of the porcine respiratory disease complex on productive indices and slaughter weight. Cienc Anim Bras 2019, 20, e51615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, BK. Clinical Veterinary Microbiology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2013.

- Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol. Americ Soc 2016, 1, 23, https://asm.org/getattachment/2594ce26‐bd44‐47f6‐8287‐0657aa9185ad/Kirby‐Bauer‐Disk‐Diffusion‐ Susceptibility‐Test‐Protocol‐pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). M100-S15 Vol. 25 No. 1. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/.

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated development for R. Boston: RStudio, PBC; 2020. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2009.

- Dayao DAE, Gibson JS, Blackall PJ, Turni C. Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria associated with porcine respiratory disease in Australia. Vet Microbiol. 2014, 171, 232–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Fiz F, Neila-Ibáñez C, López-Soria S, et al. Feed additives for the control of post-weaning Streptococcus suis disease and the effect on the faecal and nasal microbiota. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjirin, N.F. , Miller, E.L., Murray, G.G.R. et al. Large-scale genomic analysis of antimicrobial resistance in the zoonotic pathogen Streptococcus suis. BMC Biol 2021, 19, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura M, Aragon V, Brockmeier SL, Gebhart C, Greeff A, Kerdsin A, et al. Update on Streptococcus suis research and prevention in the era of antimicrobial restriction: 4th International Workshop on S. suis. Pathogens 2020, 9, 374. [CrossRef]

- Guitart-Matas J, Gonzalez-Escalona N, Maguire M, Vilaró A, Martinez-Urtaza J, Fraile L, et al. Revealing genomic insights of the unexplored porcine pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae using whole genome sequencing. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e01185–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa Gongora C, Larsen N, Schønning K, Fredholm M, Guardabassi L. Differential analysis of the nasal microbiome of pig carriers or non-carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0160331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman AL, Deckert AE, Carson CA, Poljak Z, Reid-Smith RJ, McEwen SA. Antimicrobial use in lactating sows, piglets, nursery, and grower-finisher pigs on swine farms in Ontario, Canada during 2017 and 2018. Porc Health Manag 2022, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klima CL, Holman DB, Cook SR, Conrad CC, Ralston BJ, Allan N, et al. Multidrug resistance in Pasteurellaceae associated with bovine respiratory disease mortalities in North America from 2011 to 2016. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 606438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Blas I, Fernández Aguilar X, Cabezón O, Aragon V, Migura-García L. Antimicrobial resistance in Pasteurellaceae isolates from Pyrenean Chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica) and domestic sheep in an alpine ecosystem. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou KT, Allen HK, Alt DP, Trachselb J, Haua SJ, Coetzeec JF, Holmand DB, Kellnerb S, Lovingb CL, Brockmeier SL Shifts in the nasal microbiota of swine in response to different dosing regimens of oxytetracycline administration. Vet Microbiol 2019, 237, 108386.

- Bonillo-Lopez L, Obregon-Gutierrez P, Huerta E, Correa-Fiz F, Sibila M, Aragon V. Intensive antibiotic treatment of sows with parenteral crystalline ceftiofur and tulathromycin alters the composition of the nasal microbiota of their offspring. Vet Res 2023, 54, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neila-Ibáñez C, Brogaard L, Pailler-García L, Martínez J, Segalés J, Segura M, et al. Piglet innate immune response to Streptococcus suis colonization is modulated by the virulence of the strain. Vet Res 2021, 52, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Decreto Nº 12.031, de 2024. Diário Oficial da União. Available from: https://www.gov.br/agricultura.

- Hopkins D, Poljak Z, Farzan A, Friendship R. Factors contributing to mortality during a Streptococcus suis outbreak in nursery pigs. Can Vet J 2018, 59, 623–30. [Google Scholar]

- Murray GGR, Hossain ASMM, Miller EL, Bruchmann S, Balmer AJ, Matuszewska M, et al. The emergence and diversification of a zoonotic pathogen from within the microbiota of intensively farmed pigs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2023, 120, e2307773120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjirin, N.F. , Miller, E.L., Murray, G.G.R. et al. Large-scale genomic analysis of antimicrobial resistance in the zoonotic pathogen Streptococcus suis. BMC Biol 2021, 19, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco MS, Rossi CC, Brito MAVP, Laport MS, Barros EM, Giambiagi-de Marval M. Characterization of biofilms and antimicrobial resistance of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species involved with subclinical mastitis. J Dairy Res 2021, 88, 179–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng J, Liu K, Wang K, Yang B, Xu H, Wang J, et al. The prevalence of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus associated with bovine mastitis in China and its antimicrobial resistance rate: a meta-analysis. J Dairy Res 2023, 90, 158–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S. , Kehrenberg, C.,Walsh, T.R. Use of antimicrobial agents in veterinary medicine and food animal production. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2001, 17, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obregon-Gutierrez P, Bonillo-Lopez L, Correa-Fiz F, Sibila M, Segalés J, Kochanowski K, et al. Gut-associated microbes are present and active in the pig nasal cavity. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Serrano S, Galofré-Milà N, Costa-Hurtado M, et al. Heterogeneity of Moraxella isolates found in the nasal cavities of piglets. BMC Vet Res 2020, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmmod YS, Correa-Fiz F, Aragon V. Variations in association of nasal microbiota with virulent and non-virulent strains of Glaesserella (Haemophilus) parasuis in weaning piglets. Vet Res 2020, 51, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa Gongora C, Larsen N, Schønning K, Fredholm M, Guardabassi L. Differential analysis of the nasal microbiome of pig carriers or non-carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0160331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penders J, Stobberingh EE, Savelkoul PH, Wolffs PF. The human microbiome as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance. Front Microbiol 2013, 4, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalisi N, Kuhnert P, Amado MEV, Overesch G, Stärk KDC, Ruggli N, et al. Seroprevalence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in sows fifteen years after implementation of a control programme for enzootic pneumonia in Switzerland. Vet Microbiol 2022, 270, 109455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Vega C, Scoglio, C, Clavijo MJ, Robbins R, Karriker L, Liu X, Martínez-López B. A tool to enhance antimicrobial stewardship using similarity networks to identify antimicrobial resistance patterns across farms. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Farm | Farm isolation | Swine herds distance | Road distance | Breeders reposition | Quaran-tine | Vectors control | Type of Feed | Feed Transport | Vehicle disinfection | Human Access | Bio score* |

| A | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| B | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 7 |

| C | 1 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| D | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 7 |

| E | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| F | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 7 |

| G | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 7 |

| H | 0.25 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 7 |

| I | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 7 |

| J | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 6 |

| Pharmacologic Class | Antimicrobials | Concentration disk |

| Aminoglycoside | Amikacin (AMI) | 30 µg |

| Gentamicin (GEN) | 10 µg | |

| Neomycin (NEO) | 30 µg | |

| Amphenicol | Florfenicol (FLF) | 30 µg |

| β-lactamase | Amo + Clavulanic acid (AMC) | 20 µg |

| Amoxicillin (AMO) | 30 µg | |

| Ampicillin (AMP) | 10 µg | |

| Penicillin | Penicillin (PEN) | 30 µg |

| Cephalosporine | Cephalothin (CFL) | 30 µg |

| Cephalexin (CFE) | 30 µg | |

| Ceftiofur (CFT) | 30 µg | |

| Quinolones | Enrofloxacin (ENO) | 5µg |

| Marbofloxacin (MBO) | 5µg | |

| Norfloxacin (NOR) | 10 µg | |

| Lincosamide | Clindamycin (CLI) | 2 µg |

| Macrolide | Erythromycin (ERI) | 15 µg |

| Tylosin (TLS) | 60 µg | |

| Tulathromycin (TUL) | 30 µg | |

| Tetracycline | Tetracycline (TET) | 30 µg |

| Doxycycline (DOX) | 30 µg | |

| Polypeptide | Bacitracin (BC) | 10 µg |

| Sulphonamide | sulfametoxazol (SUL) | 300µg |

| sulfametoxazol-trimetoprim (SUT) | 25 µg |

| Farm | PCR | Culture |

| A | P. multocida | A. suis; P. multocida; S. suis. |

| B | P. multocida; G. parasuis | A. suis; P. multocida; S. suis. |

| C | G. parasuis | A. suis; S. suis |

| D | P. multocida | B. bronchiseptica |

| E | P. multocida | A. suis; B. bronchiseptica; P. multocida |

| F | G. parasuis | B. bronchiseptica |

| G | P. multocida | A. suis; B. bronchiseptica;P. multocida; S. suis |

| H | P. multocida | A. suis; P. multocida |

| I | G. parasuis | A. suis; S. suis |

| J | A. pleuropneumoniae | S. ser. Typhimurium; S. aureus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).