Submitted:

02 September 2024

Posted:

03 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Growth and Flowering

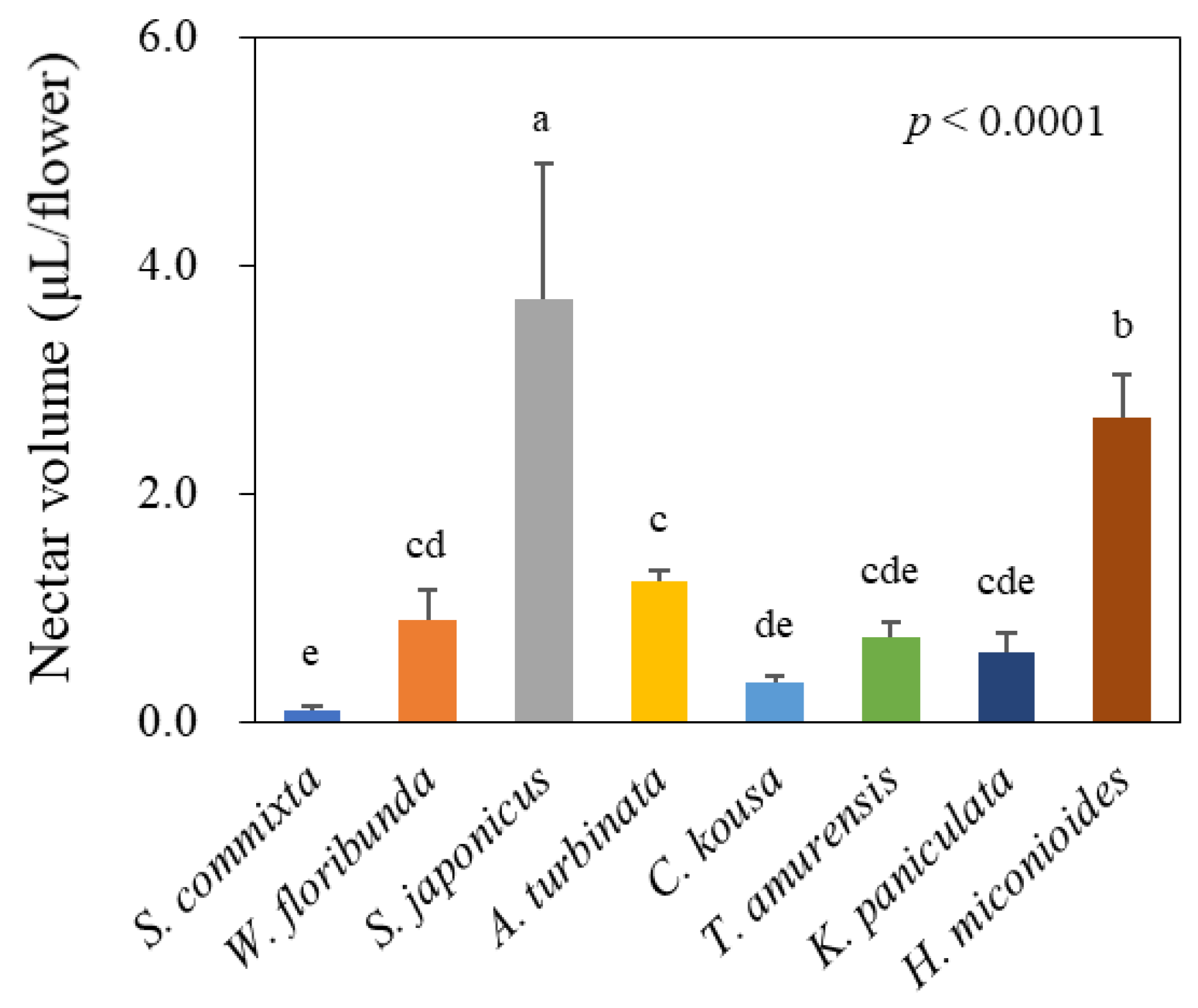

2.2. Nectar Volume and Composition

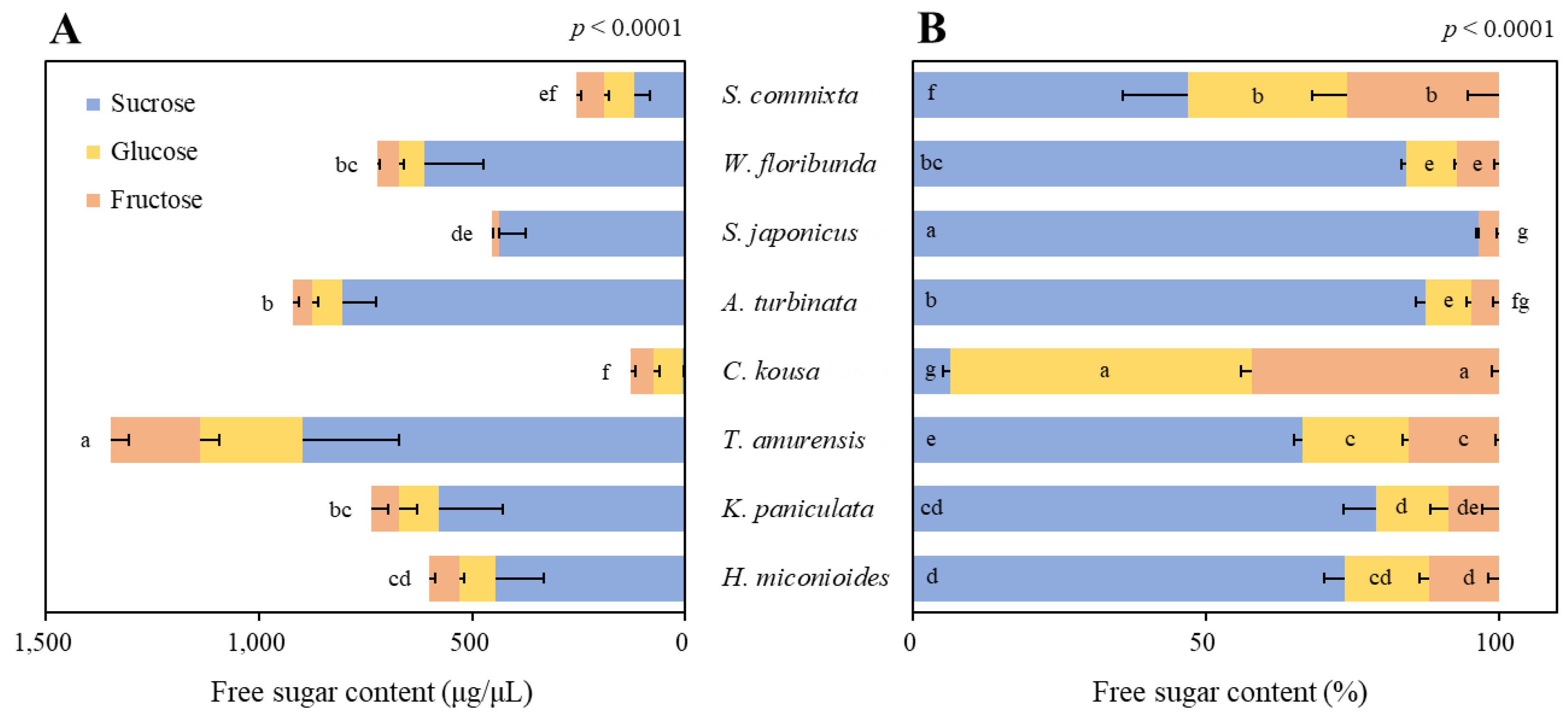

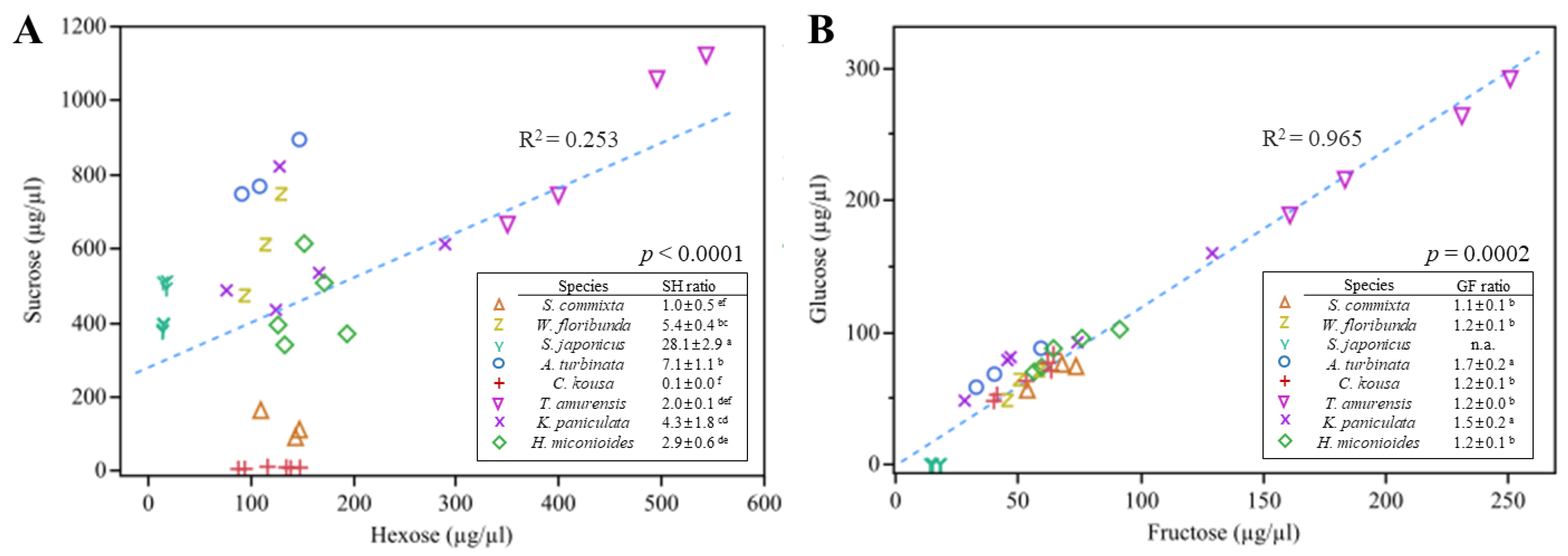

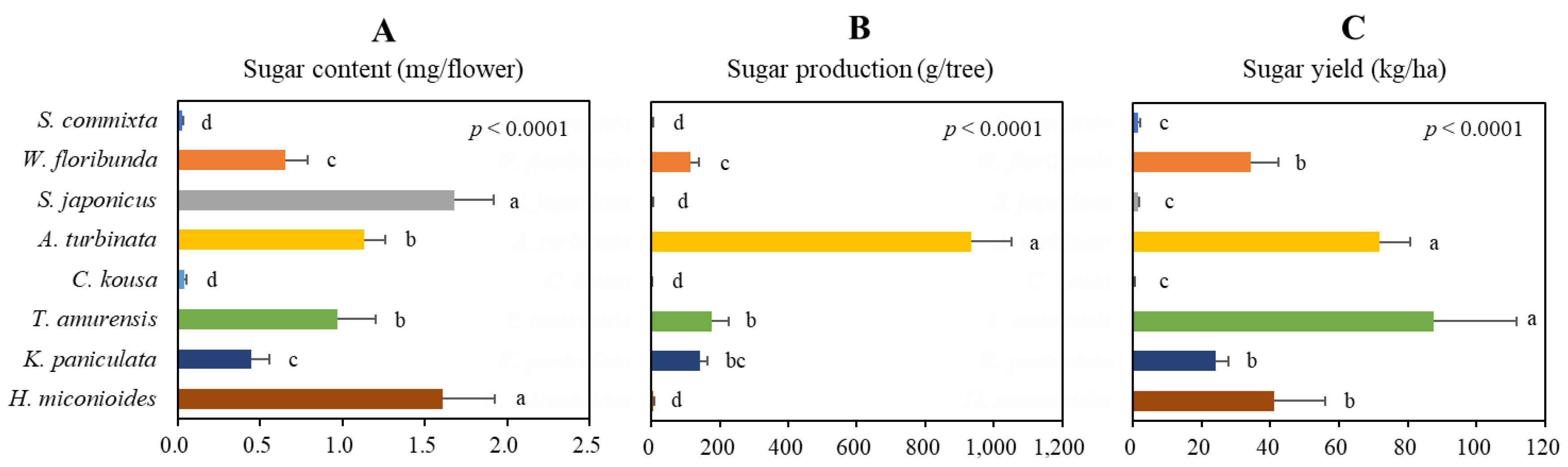

2.3. Sugar Content

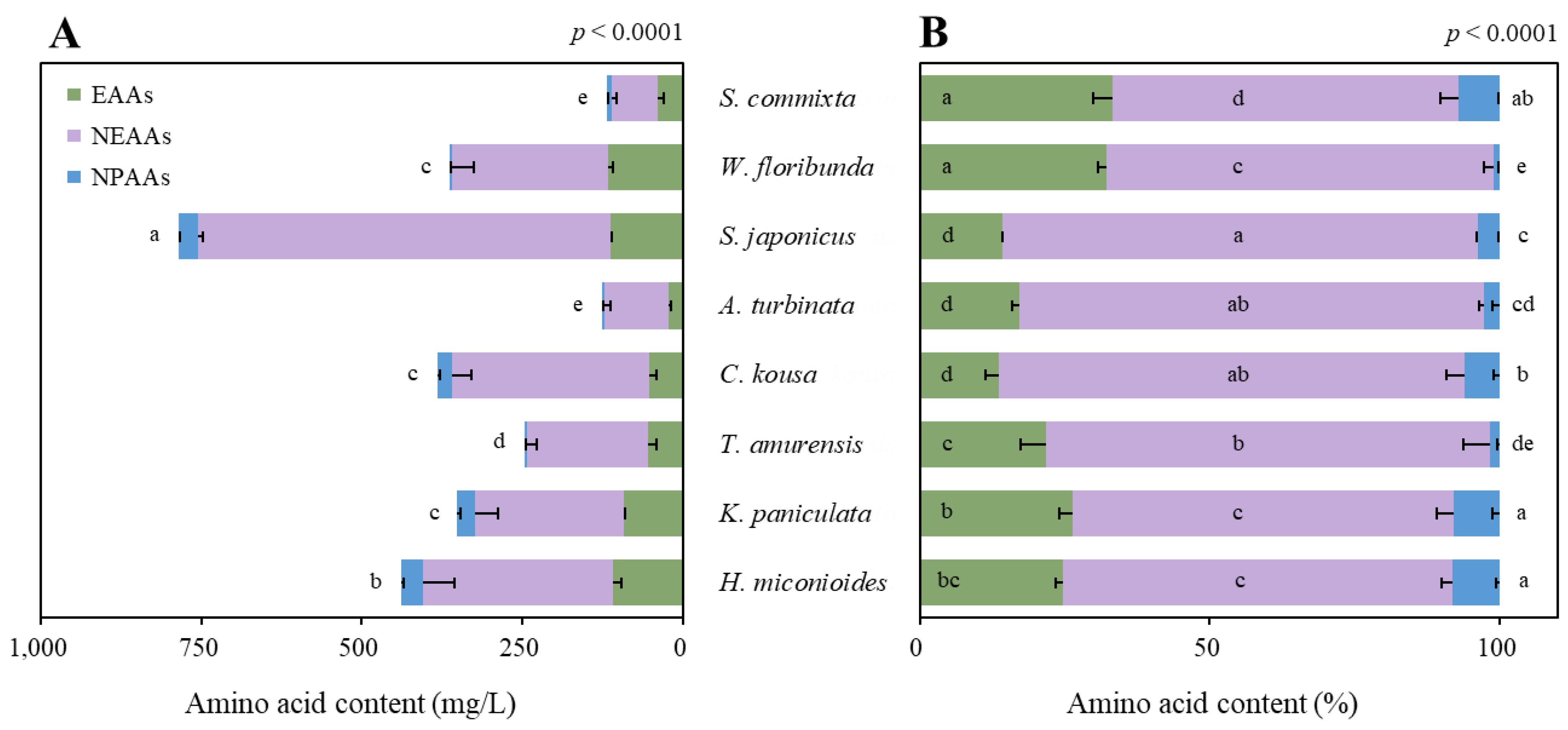

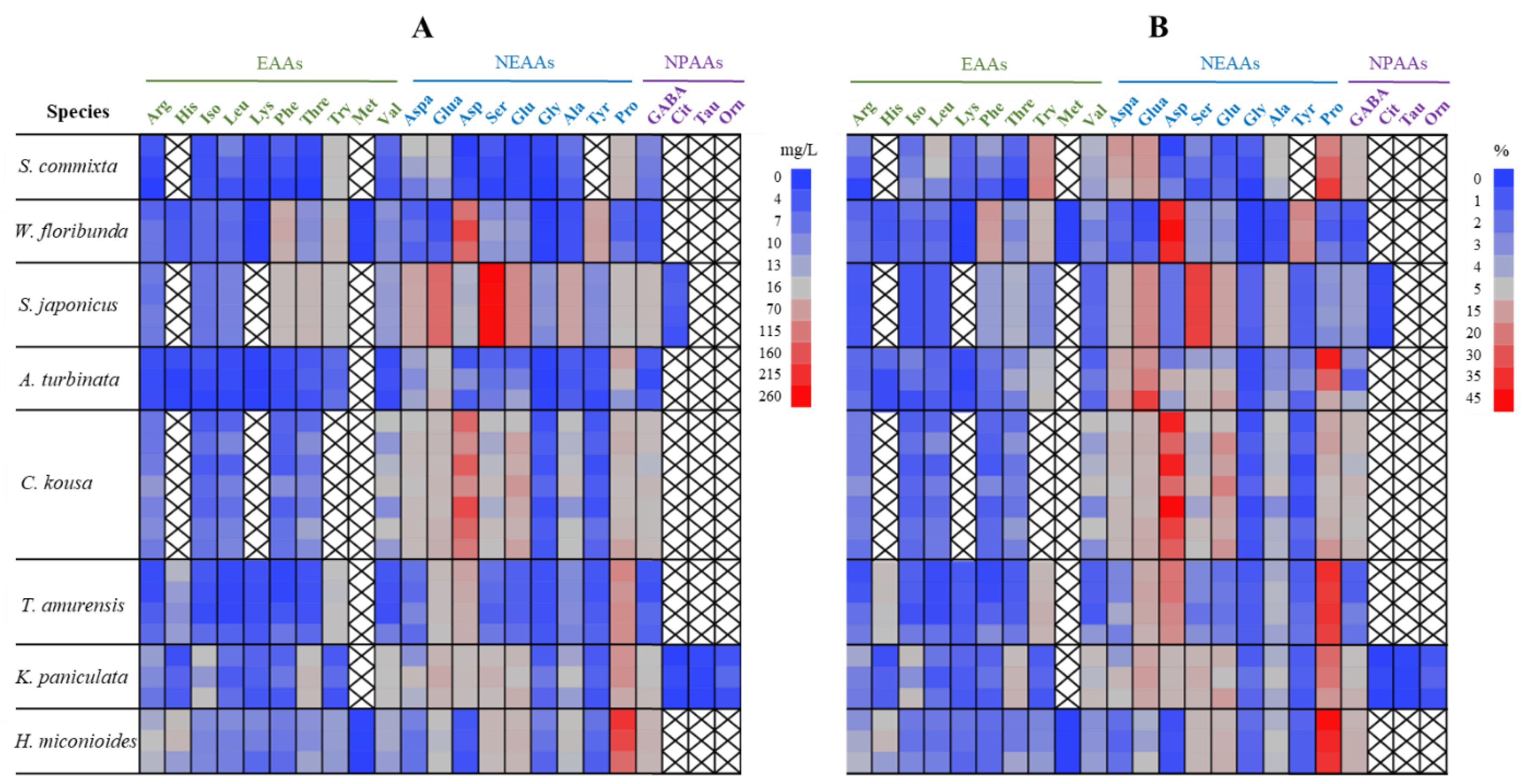

2.4. Amino Acid Content and Composition

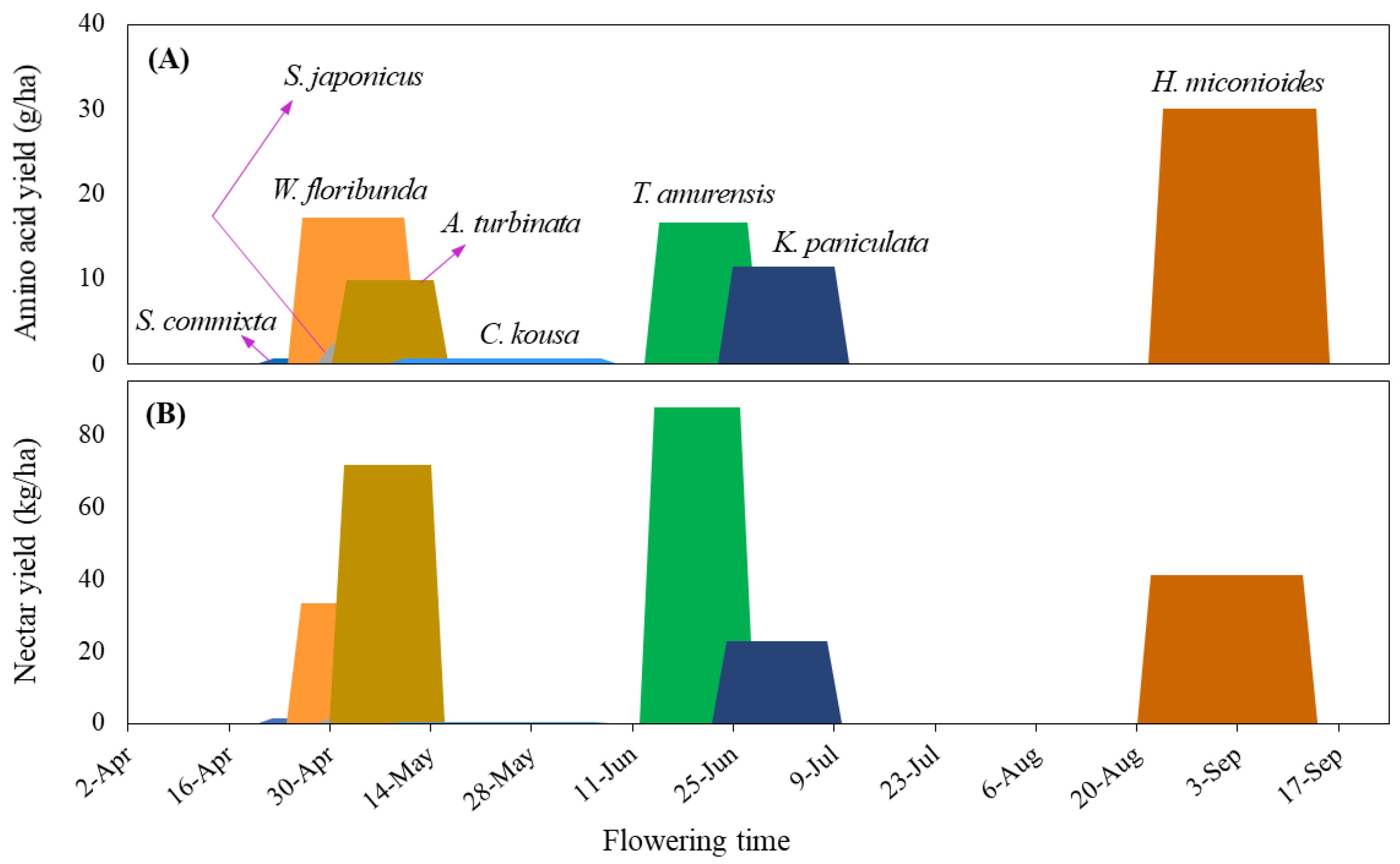

2.5. Production Potential of Sugar

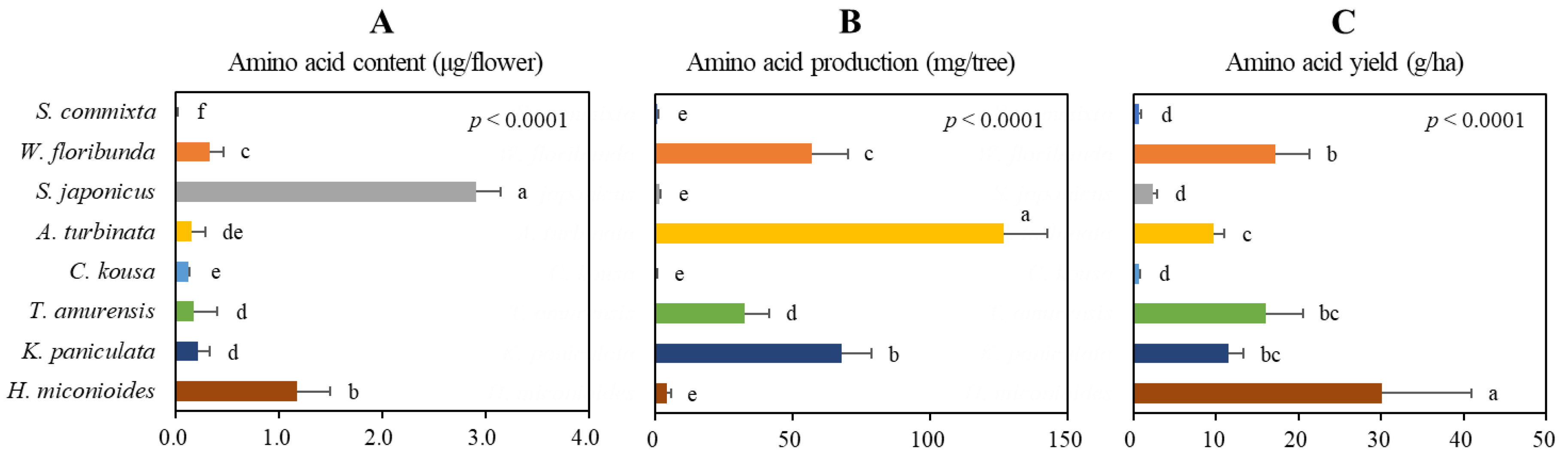

2.6. Production Potential of Amino Acid

3. Discussion

3.1. Evaluating the Usefulness of Floral Resources Requires a Comprehensive Consideration of Various Factors

3.2. Sugar and Amino Acid Availability

3.3. Limitations

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Study Site and Tree Species

4.2. Nectar Measurement

4.3. Sugar and Amino Acid Analysis

4.4. Amino Acid Content and Composition

4.5. Production Potential

4.6. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ollerton, J.; Winfree, R.; Tarrant, S. How many flowering plants are pollinated by animals? Oikos 2011, 120, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, L.A.; Sáez, A.; Aizen, M.A.; Fijen, T.; Bartomeus, I. Crop pollination management needs flower-visitor monitoring and target values. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmer, P. Pollination and Floral Ecology. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA. 2011.

- Potts, S.G.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Kremen, C.; Neumann, P.; Schweiger, O.; Kunin, W.E. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J. Pollinator decline – An ecological calamity in the making? Sci. Prog. 2018, 101, 121–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Uribe, M.M.; Ricigliano, V.A.; Simone-Finstrom, M. Defining pollinator health: A holistic approach based on ecological, genetic, and physiological factors. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2020, 8, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D.; Nicholls, E.; Botías, C.; Rotheray, E.L. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 2015, 347, 1255957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, E.I.; Ghazoul, J. Plant-pollinator interactions within the urban environment. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011, 13, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazoul, J. Buzziness as usual? Questioning the global pollination crisis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, T.; Winfree, R. Urban drivers of plant-pollinator interactions. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.A.; Boscolo, D.; Lopes, L.E.; Carvalheiro, L.G.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; da Rocha, P.L.B.; Viana, B.F. Forest and connectivity loss simplify tropical pollination networks. Oecologia 2020, 192, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.H.D.; Gomes, I.N.; Cardoso, J.C.F.; Bosenbecker, C.; Silva, J.L.S.; Cruz-Neto, O.; Oliveira, W.; Stewart, A.B.; Lopes, A.V.; Maruyama, P.K. Diverse urban pollinators and where to find them. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 281, 110036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Haase, D. Green spaces of European cities revisited for 1990–2006. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 110, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threlfall, C.G.; Mata, L.; Mackie, J.A.; Hahs, A.K.; Stork, N.E.; Williams, N.S.G.; Livesley, S.J. Increasing biodiversity in urban green spaces through simple vegetation interventions. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1874–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldock, K.C.R.; Goddard, M.A.; Hicks, D.M.; Kunin, W.E.; Mitschunas, N.; Morse, H.; Osgathorpe, L.M.; Potts, S.G.; Robertson, K.M.; Scott, A.V.; et al. A systems approach reveals urban pollinator hotspots and conservation opportunities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixo, K.P.; de Faria, L.B.; Groppo, M.; Castro, M.M.N.; da Silva, C.I. Spatiotemporal distribution of floral resources in a Brazilian city: Implications for the maintenance of pollinators, especially bees. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braaker, S.; Ghazoul, J.; Obrist, M.K.; Moretti, M. Habitat connectivity shapes urban arthropod communities: the key role of green roofs. Ecology 2014, 95, 1010–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldock, K.C.R.; Goddard, M.A.; Hicks, D.M.; Kunin, W.E.; Mitschunas, N.; Osgathorpe, L.M.; Potts, S.G.; Robertson, K.M.; Scott, A.V.; Stone, G.N.; et al. Where is the UK’s pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower-visiting insects. Proc. R. Soc. B 2015, 282, 20142849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D.M.; Ouvrard, P.; Baldock, K.C.R.; Baude, M.; Goddard, M.A.; Kunin, W.E.; Mitschunas, N.; Memmott, J.; Morse, H.; Nikolitsi, M.; et al. Food for pollinators: Quantifying the nectar and pollen resources of urban flower meadows. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0158117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, A.; Grass, I.; Belavadi, V.V.; Tscharntke, T. How urbanization is driving pollinator diversity and pollination–a systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marselle, M.R.; Bowler, D.E.; Watzema, J.; Eichenberg, D.; Kirsten, T.; Bonn, A. Urban street tree biodiversity and antidepressant prescriptions. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somme, L.; Moquet, L.; Quinet, M.; Vanderplanck, M.; Michez, D.; Lognay, G.; Jacquemart, A.-L. Food in a row: urban trees offer valuable floral resources to pollinating insects. Urban Ecosyst. 2016, 19, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachuła, J.; Denisow, B.; Strzałkowska-Abramek, M. Floral reward and insect visitors in six ornamental Lonicera species – Plants suitable for urban bee-friendly gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzałkowska-Abramek, M. Nectar and pollen production in ornamental cultivars of Prunus serrulate (Rosaceae). Folia Hort. 2019, 31, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitruk, M.; Strzałkowska-Abramek, M.; Bożek, M.; Denisow, B. Plants enhancing urban pollinators: Nectar rather than pollen attracts pollinators of Cotoneaster species. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaux, C.; Ducloz, F.; Crauser, D.; Le Conte, Y. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biol. Lett. 2010, 6, 562–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipiak, M.; Kuszewska, K.; Asselman, M.; Denisow, B.; Stawiarz, E.; Woyciechowski, M.; Weiner, J. Ecological stoichiometry of the honeybee: Pollen diversity and adequate species composition are needed to mitigate limitations imposed on the growth and development of bees by pollen quality. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0183236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsmann, M.; von Wehrden, H.; Klein, A.M.; Leonhardt, S.D. Plant diversity and composition compensate for negative effects of urbanization on foraging bumble bees. Apidologie 2015, 46, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, A.; Armitage, J.; Bostock, H.; Perry, J.; Tatchell, M.; Thompson, K. Enhancing gardens as habitats for flower-visiting aerial insects (pollinators): should we plant native or exotic species. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.N.; Bosenbecker, C.; Silva, V.H.D.; Cardoso, J.C.F.; Pena, J.C.; Maruyama, P.K. Spatiotemporal availability of pollinator attractive trees in a tropical streetscape: unequal distribution for pollinators and people. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 83, 127900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Kahn, P.H. Living in cities, naturally. Science 2016, 352, 938–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.J.; Petrokofsky, G. The natural capital of city trees. Science 2017, 356, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Slik, F. Are street trees friendly to biodiversity? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 218, 104304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney, S.; Purdy, J. Dietary requirements of individual nectar foragers, and colony-level pollen and nectar consumption: a review to support pesticide exposure assessment for honey bees. Apidologie 2020, 51, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalcoff, V.R.; Aizen, M.A.; Galetto, L. Nectar concentration and composition of 26 species from the temperate forest of South America. Ann. Bot. 2006, 97, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, D. Nectar sugar composition and volumes of 47 species of Gentianales from a southern Ecuadorian montane forest. Ann. Bot. 2006, 97, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Dunker, S.; Durka, W.; Dominik, C.; Heuschele, J.M.; Honchar, H.; Hoffmann, P.; Musche, M.; Paxton, R.J.; Settele, J.; Schweiger, O. Eco-evolutionary processes shaping floral nectar sugar composition. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardener, M.C.; Gillman, M.P. Analyzing variability in nectar amino acids: Composition is less variable than concentration. J. Chem. Ecol. 2001, 27, 2545–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petanidou, T.; Van Laere, A.; Ellis, W.N.; Smets, E. What shapes amino acid and sugar composition in Mediterranean floral nectars? Oikos 2006, 115, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, S.W. Sweet solutions: Nectar chemistry and quality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2022, 377, 20210163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzałkowska-Abramek, M.; Jachuła, J.; Wrzesień, M.; Bożek, M.; Dąbrowska, A.; Denisow, B. Nectar production in several Campanula species (Campanulaceae). Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus. 2018, 17, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitruk, M.; Wrzesień, M.; Strzałkowska-Abramek, M.; Denisow, B. Pollen food resources to help pollinators. A study of five Ranunculaceae species in urban forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishchuk, O.; Odintsova, A. Micromorphology and anatomy of the flowers in Clivia spp. and Scadoxus multiflorus (Haemantheae, Amaryllidaceae). Acta Agrobot. 2021, 74, 7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertazzini, M.; Forlan, G. Intraspecific variability of floral nectar volume and composition in rapeseed (Brassica napus L. var. oleifera). Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, S.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, J.M. Nectar characteristics and honey production potential of five rapeseed cultivars and two wildflower species in South Korea. Plants 2024, 13, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, V.T.; Agostini, K.; Souza, C.S.; Maruyama, P.K. Tropical urban areas support highly diverse plant-pollinator interactions: an assessment from Brazil. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, K.P.; McDougall, F.O.; Seymour, R.S. A review of the energetics of pollination biology. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2013, 183, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepi, M. Beyond nectar sweetness: The hidden ecological role of non-protein amino acids in nectar. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalisova, N.I.; Kamyshe, N.G.; Lopatina, N.G.; Kontsevaya, E.A.; Urtieva, S.A.; Urtieva, T.A. Effect of encoded amino acids on associative learning of honey bee: Apis mellifera. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2011, 47, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, N.K.; Gray, H.E.; Wright, G.A. Single amino acids in sucrose rewards modulate feeding and associative learning in the honeybee. J. Insect Physiol. 2014, 69, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roguz, K.; Bajguz, A.; Chmur, M.; Gołębiewska, A.; Roguz, A.; Zych, M. Diversity of nectar amino acids in the Fritillaria (Liliaceae) genus: Ecological and evolutionary implications. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandelook, F.; Janssens, S.B.; Gijbels, P.; Fischer, E.; van den Ende, W.; Honnay, O.; Abrahamczyk, S. Nectar traits differ between pollination syndromes in Balsaminaceae. Ann. Bot. 2019, 124, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlesso, D.; Smargiassi, S.; Pasquini, E.; Bertelli, G.; Baracchi, D. Nectar non-protein amino acids (NPAAs) do not change nectar palatability but enhance learning and memory in honey bees. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, E.A. Nonprotein amino acids of plants: Significance in medicine, nutrition, and agriculture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2854–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.A.; Chatt, E.C.; Mahalim, S.-N.; Guirgis, A.; Guo, X.; Nettleton, D.S.; Nikolau, B.J.; Thornburg, R.W. Metabolomic Profiling of Nicotiana Spp. Nectars indicate that pollinator feeding preference is a stronger determinant than plant phylogenetics in shaping nectar diversity. Metabolites 2020, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, S.; Bicker, G. Distribution of GABA-like immunoreactivity in the brain of the honeybee. J. Comp. Neurol. 1986, 246, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachse, S.; Galizia, C.G. Role of inhibition for temporal and spatial odor representation in olfactory output neurons: A calcium imaging study. J. Neurophysiol. 2002, 87, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccuglia, D.; Mueller, U. Focal uncaging of GABA reveals a temporally defined role for GABAergic inhibition during appetitive associative olfactory conditioning in honeybees. Learn. Mem. 2013, 20, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicker, G. Taurine-like immunoreactivity in photoreceptor cells and mushroom bodies: A comparison of the chemical architecture of insect nervous systems. Brain Res. 1991, 560, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustard, J.A.; Jones, L.; Wright, G.A. GABA signaling affects motor function in the honey bee. J. Insect Physiol. 2020, 120, 103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito Vera, G.A.; Pérez, F. Floral nectar (FN): drivers of variability, causes, and consequences. Braz. J. Bot. 2024, 47, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoń, S.; Denisow, B. Nectar production and carbohydrate composition across floral sexual phases: contrasting patterns in two protandrous Aconitum species (Delphinieae, Ranunculaceae). Flora 2014, 209, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Height (m) | Crown width (m) | Flowering period | Flowering day |

| S. commixta | 3.3±0.5 | 3.1±0.4 | Apr 23–May 3 | 11 |

| W. floribunda | 3.0 | 3 x 11 * | Apr 27–May 11 | 15 |

| S. japonicus | 3.3±0.2 | 2.6±0.3 | May 1–May 15 | 15 |

| A. turbinata | 15.7±0.8 | 11.4±0.4 | May 3–May 15 | 13 |

| C. kousa | 3.9±1.7 | 2.0±0.3 | May 12–Jun 7 | 27 |

| T. amurensis | 4.8±1.4 | 4.5±1.3 | Jun 16–Jun 28 | 14 |

| K. paniculata | 5.6±0.9 | 7.7±0.2 | Jun 24–Jul 9 | 16 |

| H. miconioides | 2.1±0.3 | 1.2±0.2 | Aug 24–Sep 14 | 22 |

| Species | Number of flowers per tree (thous.) | Number of flowers per ha (thous.) | ||

| Mean±SD | Min - Max | Mean±SD | Min–Max | |

| S. commixta | 49.5±20.7d | 21.6–82.1 | 51,515±21,540b | 22,441–85,401 |

| W. floribunda | 174.0±40.9c | 134.6–216.2 | 52,723±12,393b | 40,785–65,526 |

| S. japonicus | 0.6±0.0e | 0.4–0.7 | 829±154d | 633–976 |

| A. turbinata | 824.7±104.1a | 720.6–928.8 | 63,460±8,009b | 55,450–71,469 |

| C. kousa | 2.0±0.7e | 1.1–2.6 | 4,943±1,661a | 2,811–6,559 |

| T. amurensis | 182.3±50.0c | 100.4–279.6 | 90,019±24,814a | 49,556–138,050 |

| K. paniculata | 318.3±50.9b | 267.4–369.2 | 53,684±8,589c | 45,094–62,273 |

| H. miconioides | 3.7±1.3e | 2.0–6.2 | 25,600±9,237c | 14,000–42,933 |

| p-value | < 0.0001 | - | < 0.0001 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).