Introduction

Global urbanisation is accelerating, with an estimated 68% of the world’s population projected to live in urban areas by 2050 (United Nations, 2018). This expansion is a major driver of biodiversity loss, as natural and semi-natural habitats are replaced by high-density built infrastructure (Seto et al., 2012; Li et al., 2022). In the UK, this trend is driven by housing targets and brownfield redevelopment priorities (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2024). In densely built environments, opportunities for conventional horizontal greenspace are limited, prompting growing interest in green infrastructure solutions that integrate vegetation into the vertical built environment (Tzoulas et al., 2007). Among these, living wall systems (LWS)— modular panels of vegetation with hydroponic or substrate-based rooting media attached vertical to buildings—have gained attention for their potential to contribute to urban biodiversity (Ottelé et al., 2011; Francis & Lorimer, 2011)

Green infrastructure can support significant biodiversity when appropriately designed (Aronson et al., 2014; Ives et al., 2016) and offers a multifunctional solution to the environmental problems of urbanisation, providing aesthetic and thermal benefits (Perini et al., 2013; Cameron et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2022; Lunt et al., 2022), supporting ecosystem services such as air purification, noise attenuation, and façade protection (Rondeau et al., 2012; Ismail, 2013; Köhler, 2008).

Vertical surfaces make up a high percentage of the surface area in high rise city developments, highlighting the potential scale of their contribution (Chen et al. 2020). Living wall systems could offer habitats for a wide range of organisms, reducing urban habitat loss, fragmentation and isolation. However, the biodiversity potential of LWS remains underexplored. A systematic review by Tiago et al. (2024) found just 56 peer-reviewed papers focused on biodiversity in LWS or green roofs, with few examining multiple taxonomic groups or temperate climate contexts. Most studies focused on arthropods, and only four assessed more than one faunal group. This underscores significant research gaps, especially regarding soil invertebrates and the role of rooting substate in shaping ecological outcomes (Madre et al., 2015; Pérez-Urrestarazu et al., 2021).

While LWS are valued primarily for their visual and thermal performance, their design parameters, particularly substrate and plant choice, are critical to their ecological value (Salisbury et al. 2023). Native plant species adapted to desiccating urban microclimates support recruitment of native fauna and improve resilience (Dunnett & Kingsbury, 2008; Weiler & Scholz-Barth, 2009; Francis & Lorimer, 2011). Moreover, soil-based growth media outperform artificial substrates in water retention, nutrient cycling, and sustain beneficial microbial and invertebrate communities (Bustami et al. 2019; Uthappa et al., 2022; Lewandowski et al. 2023). Soil invertebrates, such as mites (Acari), springtails (Collembola), and millipedes (Diplopoda), play key roles in decomposition, nutrient regulation, and ecological function (Uthappa et al. 2022). More generally, LWS design must balance biodiversity performance with ease of maintenance and water use efficiency. Modular systems allow for easy replanting, and innovations such as rainwater harvesting and greywater reuse can improve long-term sustainability (Manso & Castro-Gomes, 2015; Pérez-Urrestarazu et al., 2016).

Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) is a concept which focuses on enriching biodiversity as part of the development process, resulting in a natural environment that is measurably better once works are completed. In February 2024, BNG became a statutory requirement in England, requiring new developments to have a 10% uplift in biodiversity above predevelopment levels (Environment Act 2021). This compliance requirement uses Defra’s Biodiversity Metric 4.0 methodology (Natural England, 2023b) to score the predevelopment extent of UKHab index areas and compare scores to proposed post development habitat. BNG can be inset (on site) or offset (off-site biodiversity gain compensation), with the former preferred where possible. Typically for small scale developments the gain is inset, with an average of 80% as onsite mitigation (Defra, 2025).

An alternative approach to assessing the ecological impacts of development is the Wallacea biodiversity assessment framework (Wallacea Trust 2023), which incorporates field-based measurements of ecological richness, abundance, and functional diversity. By capturing fine-scale biodiversity data—including that from vertical and soil systems—this method may better reflect the real-world ecological value of LWS.

This study uses field-based biodiversity measurements to evaluate how soil-based LWS can contribute to biodiversity in urban developments. Specifically, we investigate how planting choices and rooting substrates influence invertebrate communities and assess the ecological value of LWS.

Objectives

To identify knowledge gaps in current LWS biodiversity research.

To evaluate the role of plant species choice in supporting aboveground and soil-dwelling invertebrates on LWS.

To assess the contribution of soil-based growth media to invertebrate diversity and ecological function.

To evaluate the biodiversity value of LWS.

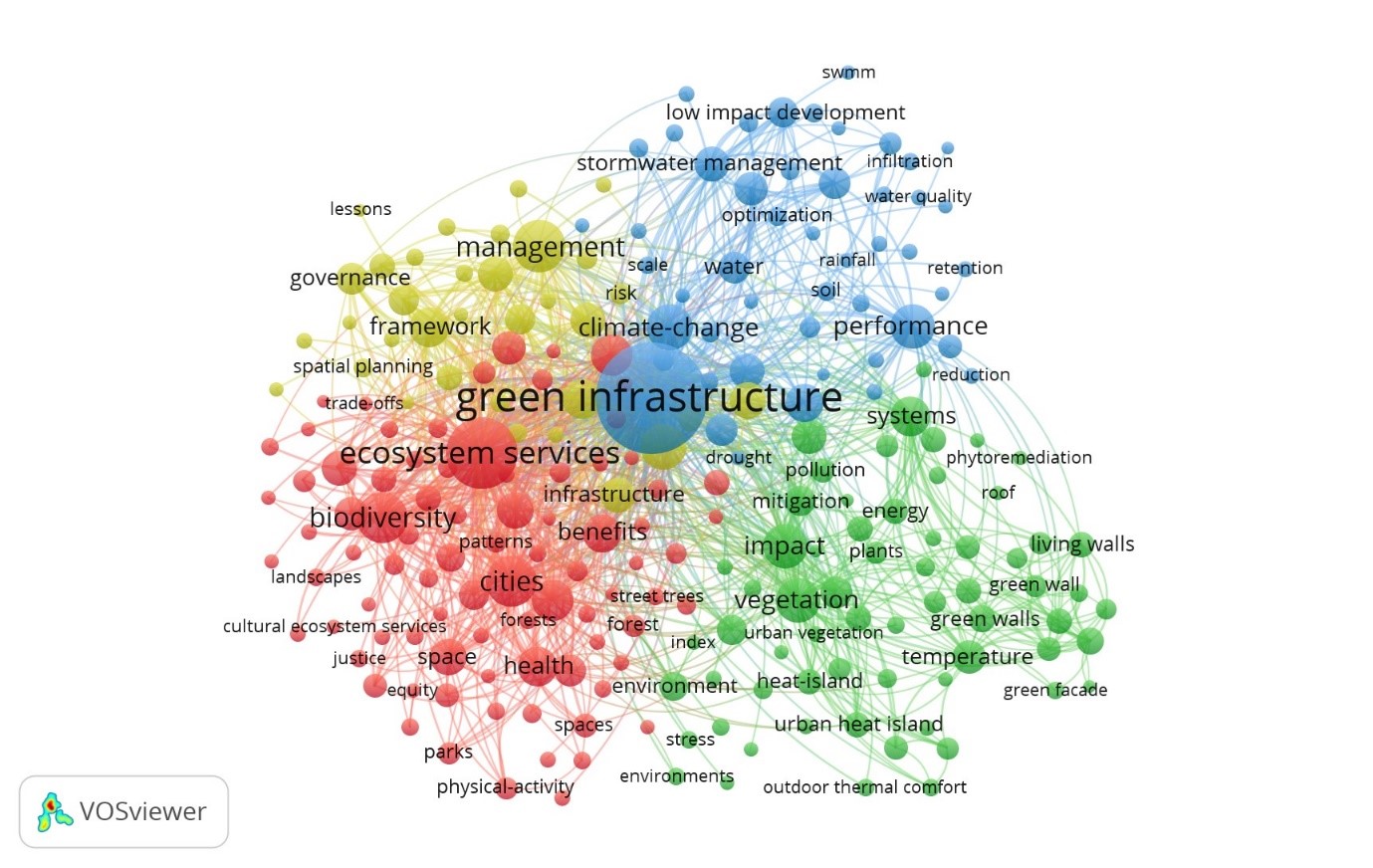

Scoping Review of Living Walls Biodiversity Benefits Literature

A scoping review of the peer reviewed literature on green infrastructure was carried out using the following databases: Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Google Scholar and ScienceDirect (Foo et al. 2021). The thematic analysis yielded over 2,638 journal articles from 1970 to 2025 (

Table 1). Less than 10% of papers were pre 2014 publications with over half the papers published in the last 5 years (2020-2025). A similar key word search showed that the most frequently referred to countries (taken as country of research location) in the LWS literature in order of frequency were USA, China, Italy, Spain, South Korea, Netherlands, Sweden, Poland, Portugal and Brazil.

Boolean operators and search strings were used to select “Living* Wall*” AND “Ecosystem Service*” papers containing specific keywords in titles and abstracts from 2015 - 2025. The review identified climate as the most frequently reported ecosystem service benefit of LWS (43% of 46 papers) with health (39%), and biodiversity (30%) also showing strongly. In relation to biodiversity, the search was limited exclusively to five terms, ranked by frequency of occurrence:

species,

birds,

native plants,

invertebrates, and

bats (

Table 1). However, out of the 500 papers reporting on living walls and biodiversity only 134 (27%) made specific reference to a species, suggesting papers make general reference to biodiversity benefits but not specific components of biodiversity.

The analysis of rooting substrates was restricted to soils, hydroponic (non-soil) systems, and artificial substrates. Of these, 81 publications referred to soils, 16 to hydroponic systems, and 20 to perlite; additional artificial substrates (rockwool and vermiculite) were recorded at lower frequencies (

Table 2). Of the mineral substrates, restricted to clay, biochar, peat, and clay pellets, clay was most frequently mentioned (13 papers). Twelve publications were identified that included the combined keywords: green wall, biodiversity, and soils.

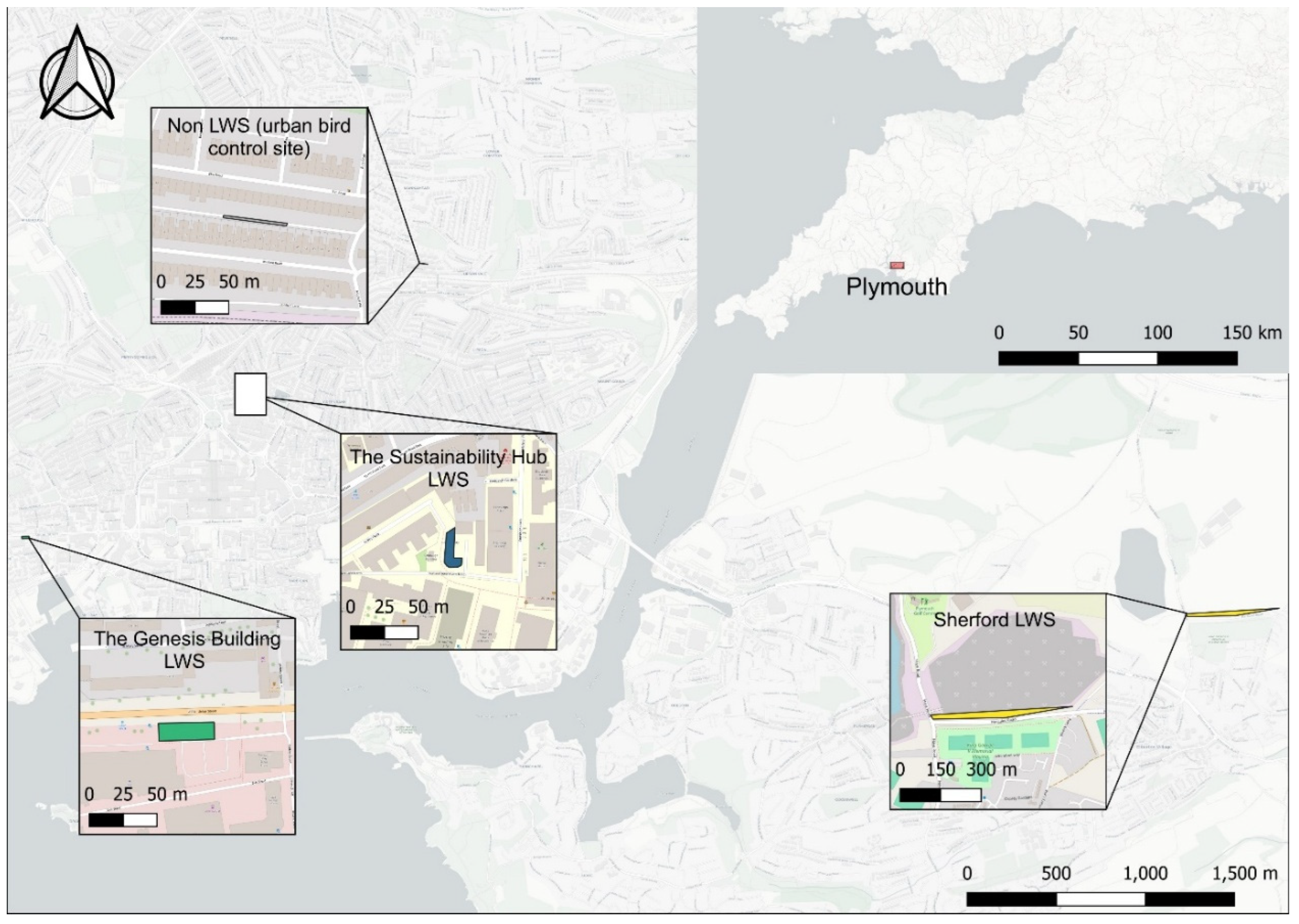

Study Sites and Living Wall Systems

Plymouth, located in southwest England, has a temperate oceanic climate (Murphy et al., 2019). Three distinct living wall systems (LWS) within the city were evaluated: the Sustainability Hub LWS, the Genesis Building LWS, and the Sherford LWS (

Figure 2).

The Sustainability Hub LWS is installed on a two-storey building at the University of Plymouth. Established in 2019, it comprises a modular Fytotextile system designed by Scotscape (Scotscape, 2018). The system uses a multi-layered fabric structure with a waterproof inner lining, an absorptive middle layer, and a permeable felt outer layer, forming discrete planting pockets filled with general-purpose potting compost. These 1.5 × 1 m panels were mounted on a wooden frame fixed to the building’s exterior.

The Genesis Building LWS, on a four-storey office building, employs a modular, soil-free, hydroponic plug-plant system developed by Biotexture (Biotecture Ltd., no date). Plants are supported in a highly absorbent synthetic rooting medium, with irrigation and nutrients delivered by a pump-driven drip system. The Sustainability Hub and Genesis Building systems both operate with this irrigation approach.

The Sherford LWS, by contrast, is a large-scale, soil-based system constructed on a retaining embankment along Hercules Road. It consists of a geogrid framework with soil-filled pockets and is entirely rainfed. The wall reaches up to 10 m in height, extends approximately 380 m in length, and accommodates around 26,000 plants.

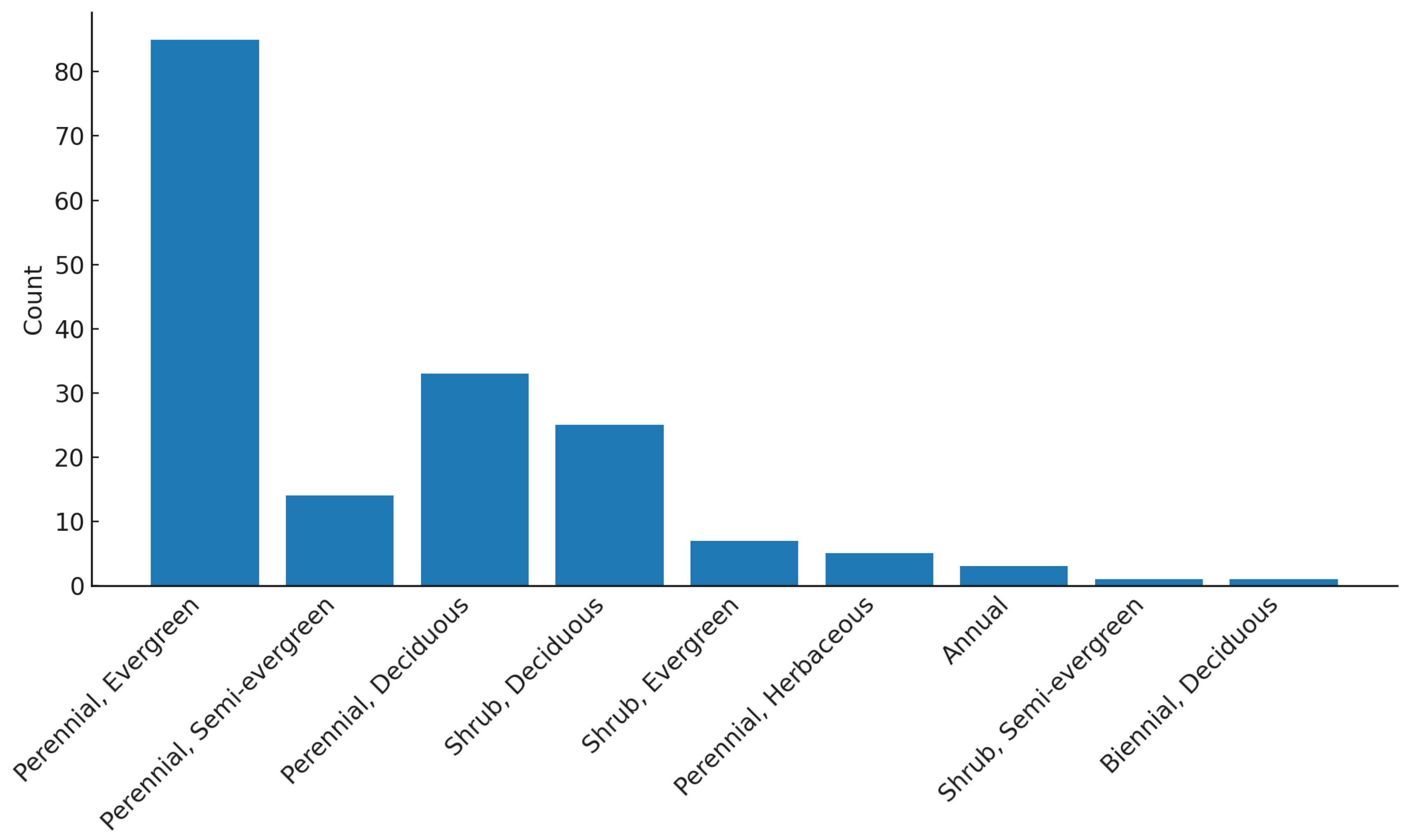

Across all three LWS, planting combined native and non-native evergreen shrubs and herbaceous species typical of temperate climates. Species were chosen for their durability, low maintenance requirements, and visual impact.

Invertebrate Surveys

For above-ground invertebrate assessments, three major arthropod taxa were selected: bees (Insecta: Hymenoptera), hoverflies (Insecta: Diptera) and spiders (Araneae). These groups are taxonomically diverse and provide essential ecosystem services, including pollination and biological control. Bees and hoverflies, which may be either resident or transient on LWS, serve as effective indicators of floral resource availability and habitat connectivity. Spiders, typically resident predators, are valuable indicators of local invertebrate community health and trophic structure.

Below-ground invertebrates were also surveyed due to their critical roles in soil health, nutrient cycling, and plant–soil interactions. To capture a representative range of plant–invertebrate associations, eight commonly used non-native and one native plant species were selected based on their growth forms and flowering phenology (

Table 3).

Surveys of both above-ground (flower-visiting bees and hoverflies, and spiders) and below-ground (root- and detritivore-feeding) invertebrates were conducted during the primary activity period for most UK invertebrates, from May to November. Adult specimens were identified to species level where possible, or to morpho-species level when taxonomic resolution was possible. Morpho-species refer to taxonomically unresolved groups distinguished by shared morphological traits, typically classified at the family to genus level.

Assessment of Above-Ground Flower-Visiting Bees and Predatory Spiders

For Hymenoptera (specifically bees), three repeat surveys were conducted monthly during June and July 2021. Surveys were carried out under optimal UK weather conditions, with temperatures ranging from 17 to 27 °C, mostly sunny skies with partial cloud cover, and wind speeds between 7 and 13 mph. Ten 2 × 2 m survey plots were established at each of the two soil-based LWS. Each survey consisted of three repeated 5-minute observation periods per plot. Bee and hoverfly species, associated plant species, and behavioural observations were recorded, and photographs were taken to support later identification.

For Araneae (spiders), the same ten 2 × 2 m plots per soil-based LWS were surveyed once per month from June to November. When spider webs were present, individuals were gently coaxed out by triggering the web to facilitate observation. Spiders were photographed in situ to aid identification and to document their location within the LWS, whether on plant material or structural components (Rooney & Robertson, 2016; Natural History Museum of Bern, 2022).

Below-Ground Soil Meso- and Macrofaunal Invertebrate Sampling Methods

Soil invertebrate sampling was conducted on the Sustainability Hub LWS, focusing on four plant species representing three distinct growth forms. These included the herbaceous ornamental

Erigeron karvinskianus, the grass-like

Carex oshimensis, and two evergreen shrubs,

Fatsia japonica and

Sarcococca confusa (

Table 3). For each plant species, five planting pockets on the lower (accessible) section of the wall were randomly selected.

Once selected, the above-ground plant material was carefully removed. The roots and associated soil from each pocket were transferred into individual Tullgren funnels. Glass collection bottles containing 50 ml of 70% industrial denatured alcohol (IDA) were placed beneath each funnel to collect invertebrates displaced by the heat and light. Funnels were illuminated with 20-watt light bulbs for a continuous 14-day period. Collection bottles were checked every two days, and IDA levels topped up to maintain preservation quality.

At the end of the extraction period, the collection bottles were removed and the invertebrates sorted into major taxonomic groups (e.g., Acariformes, Collembola, Hemiptera, Hymenoptera). Earthworms were identified to family level (Lumbricidae). Where possible, other soil invertebrates (e.g., Acariformes) were also classified to family level to enable calculation of family-level diversity indices.

Avian Acoustic Monitoring Methods

Bird song recordings were conducted at all three LWS sites and at a control site representing a typical urban street in Plymouth (terraced housing) without green infrastructure. Surveys were carried out on three separate occasions between 26 July and 20 September 2023.

Acoustic data were collected using the Merlin ID app (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2025) on a mobile device. Recordings began at dawn and continued for 90 minutes under suitable weather conditions. Data included species identification, number of individuals, and behavioural codes based on Merlin classifications. Visual aids were used to assist with bird identification in the surrounding area. Seagulls (Laridae) were excluded from the analysis due to their wide-ranging behaviour and ubiquitous presence in coastal cities such as Plymouth.

Bat Emergence Surveys

Three bat dusk emergence and dawn re-entry surveys were carried out on all three LWS in July to September 2023. Dusk surveys began 15 to 30 minutes before sunset and continued for up to two hours. Dawn surveys began two hours before sunrise and continued for up to 30 minutes after sunrise. Surveys were only conducted in suitable weather conditions, avoiding rain, strong winds, and temperatures below 10 °C. Evidence of bat emergence was observed visually using a night vison scope and bat activity recorded using an Anabat SD2 full-spectrum bat detector.

Statistical Analysis of Biodiversity Indicators

All statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software (R Core Team, 2025). Data visualisations were produced using the ggplot2 package (Wickham, 2016). A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied to all tests.

Differences in biodiversity indicators among the three LWS were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Prior to analysis, data were checked for normality and equality of variances across groups using the Shapiro-Wilk test of residuals (Fox & Weisberg, 2019). Where necessary, non-normally distributed data were log-transformed to meet the assumptions of ANOVA. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test to identify significant differences between LWS sites.

Results

Above-Ground Plant-Invertebrate Associations on Living Walls

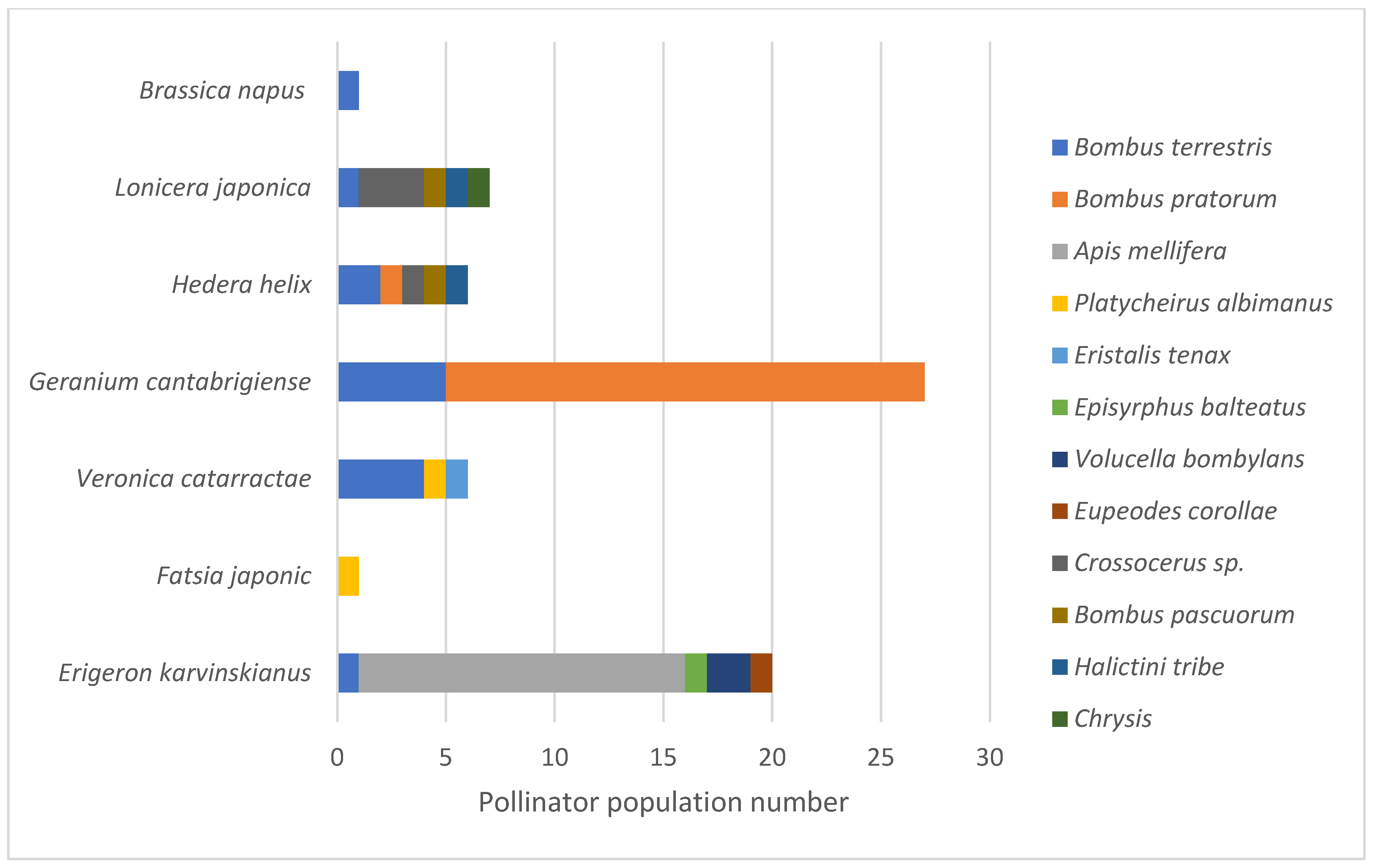

Visiting pollinator diversity varied amongst the seven plant species on the two urban LWS (

Figure 3).

Erigeron karvinskianus (Mexican fleabane),

Hedera helix (Ivy) and

Lonicera japonica (Japanese honeysuckle) attracted the highest number of pollinator species (5 species each). Although

H. helix is the only native species,

E. karvinskianus and

Lonicera japonica are both fully naturalised species in the UK with similarities to closely related native species. Notably, visitation rates to

E. karvinskianus were 2.9x higher than to the other two plant species, but this was driven by a clear preference of

Apis mellifera for

E. karvinskianus.

Geranium cantabrigiense (cranesbill) attracted the largest number of pollinator visits, but only from two

Bombus species, with visitation dominated by

Bombus pratorum (Early Bumblebee; 22 individuals;

Figure 3). Eighty-four % of the pollinators were observed to be visiting flowers (pollinator behaviour) with 13% resting and 3% involved in other behaviours.

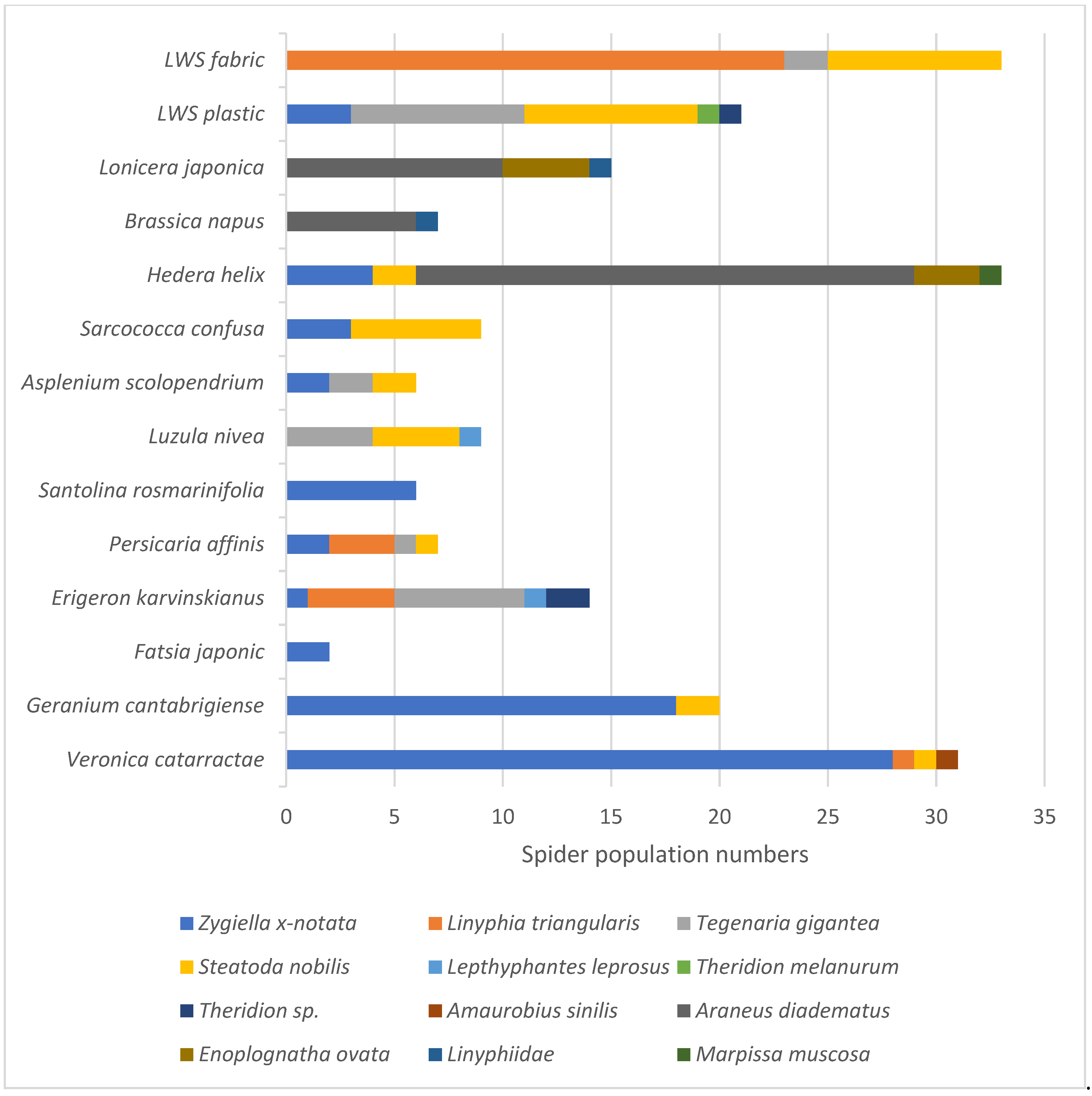

Similarly, spider abundance and diversity varied across the two soil-based LWS surfaces and 12 plant species (

Figure 4). Overall, 274 adult spider specimens from 12 taxa were sampled, with the three most abundant spider (Araneid) taxa being

Araneus diadematus (28.5% of the total spider abundance),

Zygiella x-notata (27.5%) and

Steatoda nobilis (14.2%).

H. helix, E. karvinskianus and the plastic surround of the LWS hosted the most resident araneid taxa (5 species each;

Figure 4).

H. helix and the textile fabric of the LWS supported the largest number of spiders (33 individuals each), with the native

H. helix hosting the largest numbers of

Araneus diadematus (European garden spider).

Veronica catarractae (Parahebe ‘Avalanche’) hosted the next highest abundance of spiders (31 individuals from 4 taxa). Parahebe (see

Table 3) has a rigid but open structure favoured by web spinning spiders, as shown by the high numbers of the missing sector orb weaver (

Zygiella x-notata) recorded on this plant.

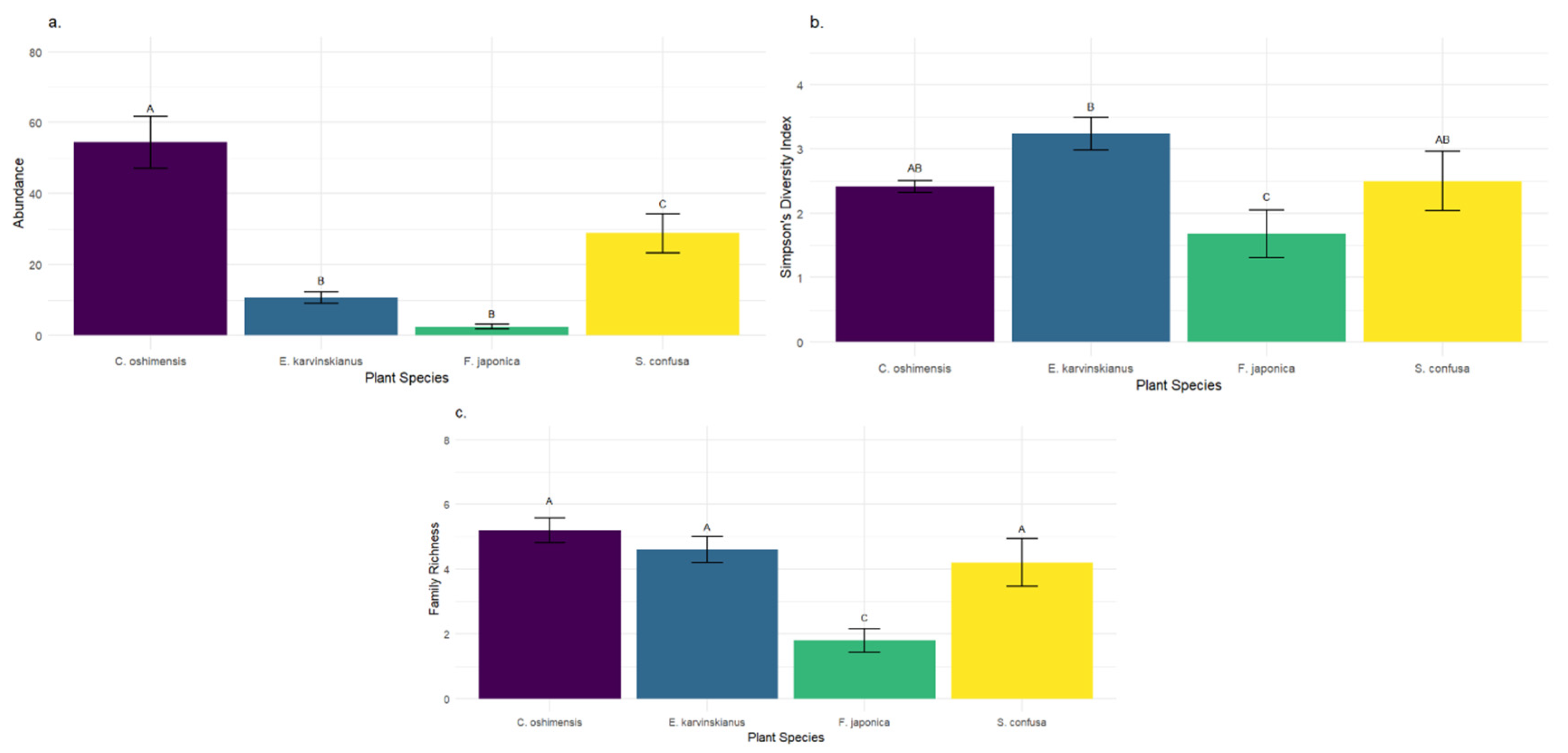

Soil Invertebrates Associated with Living Wall Plants

Tullgren sampling of soil from LWS planting pockets from four plant species yielded a total of 481 individual invertebrates across 19 different families. Over half of the individuals (258) belonged to the Mesostigmata (soil mites), making it the most abundant order, followed by the (60) Collembola (springtails). Plant species had a significant effect on soil invertebrate community composition (

Figure 5). Invertebrate abundance was found to vary significantly (F3, 55 = 24.8,

p ≤ 0.001) with plant species. Soil from

Carex oshimensis hosted significantly more soil invertebrates (272) than all other plant species, with

Sarcococca confusa hosting an intermediate (144) but significantly higher (

p ≤ 0.05) soil invertebrate abundance than both

E. karvinskianus (53) and

Fatsia japonica (12).

There was a significant difference in Simpsons Diversity of soil invertebrates between plant species (F3,16 = 3.91, p < 0.05).

E. karvinskianus had a significantly higher Simpson’s Diversity score than that of

F. japonica (

p = 0.017) but did not significantly differ from the other two plant species.

Figure 5 shows that soil invertebrate family richness (number of families observed) also showed a significant difference across plant species (F3,16 = 9.07,

p < 0.001).

F. japonica showed significantly lower family richness than

E. karvinskianus (

p = 0.005),

C. oshimensis (

p = 0.001), and

S. confusa (

p = 0.016).

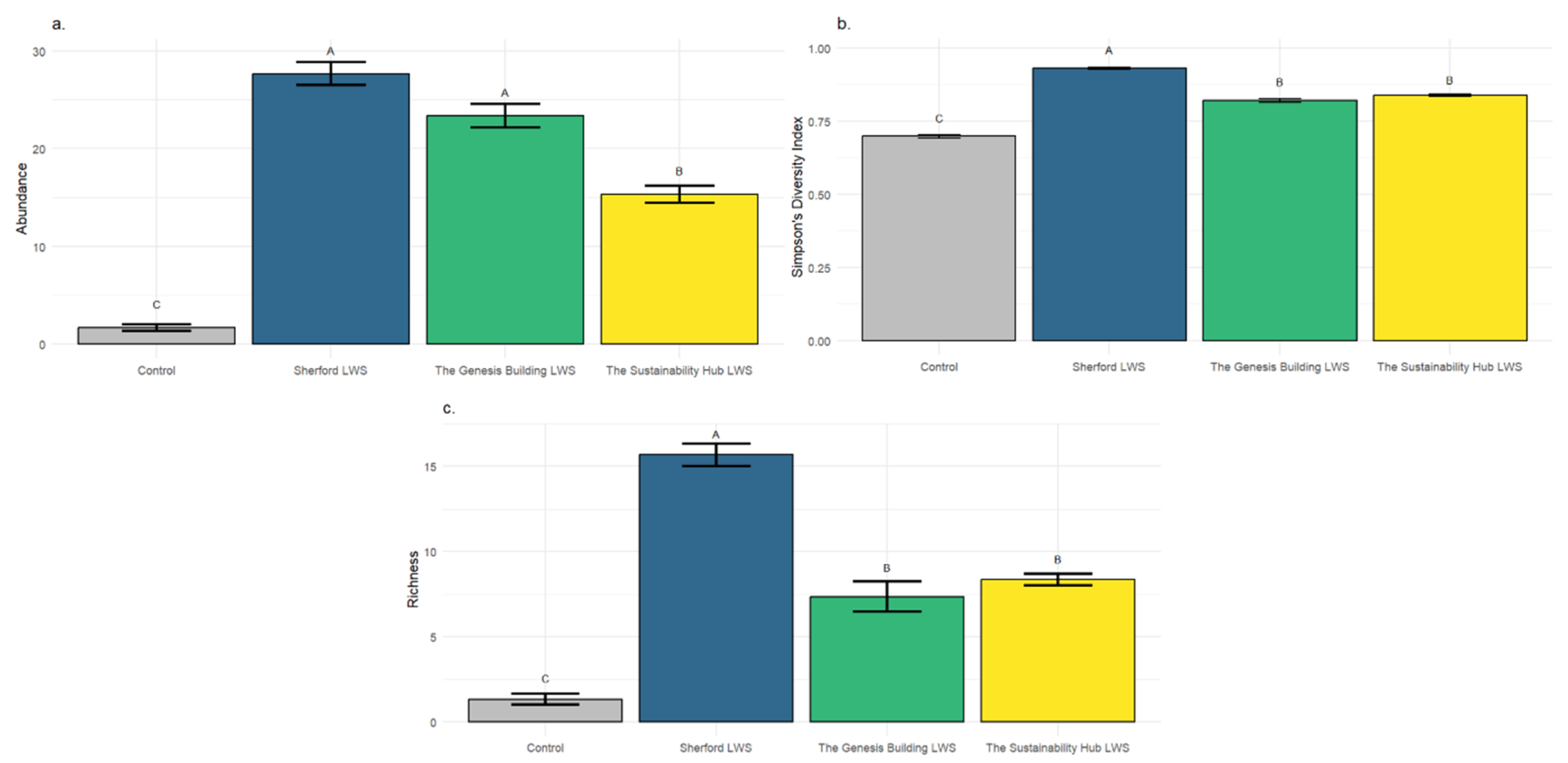

Avian Acoustic Survey Results

Acoustic monitoring recorded a total of 489 individual and 32 species. Over half of the individuals (285) belonged to the genus Larus (seagulls). Seagulls were excluded from the analysis because of their wide roaming and ubiquitous presence in coastal cities. Significant differences (F3, 55 = 24.8, p ≤ 0.001) were found in species abundance with the Sherford and Genesis Building LWS attracting significantly p ≤ 0.001) more birds, 28 and 24 respectively. The Sustainability Hub LWS showed an intermediate but significantly higher (p ≤ 0.001) bird abundance than the non LWS control area. Three species were observed using the LWSs for nesting or feeding: House sparrow (Passer domesticus) with 4 pairs confirmed breeding on the Genesis Building LWS, and Eurasian robin (Erithacus rubecula) and Eurasian Blackbird (Turdus merula) as possible breeders.

There was a significant difference in Simpsons Diversity Index of bird species between sites (F3,16 = 3.91, p < 0.05). The Sherford LWS had significantly higher Simpson’s Diversity scores than those of the other two LWS (p = 0.017), which supported intermediate but significantly higher bird diversity than the non LWS control area (p ≤ 0.001). Bird species number also showed a significant difference across sites (F3,16 = 9.07, p < 0.001). The Sherford LWS supported the highest number of bird species, significantly higher (p = 0.017), than that of the other two LWS which were intermediate but significantly higher (p ≤ 0.001) than the non LWS control area.

Figure 6.

Bird species abundance, diversity and number associated with three Plymouth living wall sites and a control urban street. a) Bird abundance; b) Simpson’s diversity Index; c) Species number. Values represent means (n=3) and bars show +/- standard error. Significant differences (p≤0.05) between LWS means are denoted by differences in superscript capital letters.

Figure 6.

Bird species abundance, diversity and number associated with three Plymouth living wall sites and a control urban street. a) Bird abundance; b) Simpson’s diversity Index; c) Species number. Values represent means (n=3) and bars show +/- standard error. Significant differences (p≤0.05) between LWS means are denoted by differences in superscript capital letters.

Discussion

Biodiversity is important for human health and wellbeing and urban environments, where most people live, require special consideration for biodiversity (Fuller et al. 2007: Collins et al. 2017; Goel et al. 2022). LWS in high density urban conurbation represent an opportunity for biodiversity enhancement (Tiago et al. 2024). Our results demonstrate that LWS can provide significant biodiversity benefits, but that this depends on their design from choices about planting to underlying substrates for plant growth.

LWS have the potential to enhance urban biodiversity by acting as ecological stepping stones or corridors that facilitate wildlife movement across fragmented landscapes (Mayrand and Clergeau 2018; Hecht et al. 2025). These structures can connect isolated habitat patches, thereby improving ecological resilience in urban areas facing pressures from climate change, habitat loss, and local species extinction (Hecht et al. 2025). While such connectivity can support native species, it may also inadvertently aid the spread of non-native organisms, as urban environments often facilitate the establishment and dispersal of invasive species through reduced biotic resistance and enhanced connectivity (Glen et al., 2013; Crooks et al. 2016; Gaertner et al. 2016).

Evidence from Partridge and Clark (2018) indicates that green roofs support greater abundance and richness of birds and arthropods compared to conventional roofs, particularly during migration and breeding seasons. This suggests that vegetated vertical structures, such as LWS, may similarly contribute to habitat quality and connectivity in urban environments (Benedict and McMahon, 2006; Belcher et al. 2018).

In addition to supporting general biodiversity, LWS may play a specific role in conserving native pollinators. Tonietto et al. (2011) demonstrated that green roofs planted with diverse native forbs provide valuable foraging and nesting resources for native bees, highlighting their potential as pollinator habitats in cities. Braaker et al. (2017) demonstrated that arthropod diversity on green roofs increased with greater habitat connectivity and plant species richness, regardless of substrate depth or roof height. If similar principles apply to LWS these findings suggest that plant diversity is a key driver of biodiversity but not the height above ground.

These findings underscore the importance of integrating LWS into urban planning frameworks, particularly within the context of biodiversity objectives, where enhancing ecological connectivity and supporting functional species groups are key priorities (Tiago et al. 2024).

Optimising Living Wall Systems (LWS) for Biodiversity: The Role of Plant Species Selection

We found that plant composition directly shaped the invertebrate communities recruited to LWS. Insect-pollinated flowering plants provide nectar and pollen for pollinators, while others support high densities of predatory taxa such as spiders or soil-dwelling invertebrates (Salisbury et al., 2023; Tartaglia and Aronson, 2024). Conversely, some species, such as

Fatsia japonica (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), consistently demonstrate low ecological value, suggesting that alternative species should be prioritised in future installations. Perennial evergreens, particularly

Hedera helix (ivy), can dominate LWS and suppress plant diversity by outcompeting annuals, deciduous perennials, and shrubs for light and space. This was evident at the Sherford LWS, where ivy covered more than 80% of the installation within three years of planting.

Plant selection in LWS is not determined solely by ecological function but also by practical and aesthetic considerations. Year-round visual appeal, species availability, and maintenance requirements strongly influence design choices. In the UK, evergreen and non-deciduous species dominate LWS installations because their persistent foliage increases visual appeal. Perennials are generally favoured over larger shrubs that require regular trimming. The predominance of non-native species in LWS reflects both the limited pool of native evergreen plants in the UK flora and the urban greening preference for evergreen perennials and shrubs (Law et al., 2025; Salisbury et al., 2017).

Birds, invertebrates, and soil organisms are widely recognised as indicators of habitat quality. The structural diversity hypothesis predicts that species richness and abundance increase with ecosystem complexity (Siemann et al., 1998; Voigt et al., 2014). This highlights the importance of thoughtful species selection in LWS design (Salisbury et al., 2023). While differences in biodiversity value between native and non-native plants are evident, they may be less pronounced in urban environments dominated by generalist species. Nonetheless, plant choice remains a critical determinant of the ecological value of LWS

Soil-Based Growth Media and Its Contribution to Biodiversity in Living Wall Systems

Our results clearly demonstrated that LWS soils can support extensive belowground invertebrate communities. Several studies have also reported the superior biodiversity associated with soil-based living wall systems (LWS) compared with soilless or hydroponic designs (Madre et al., 2015; Bustami et al., 2019; Tiago et al., 2024). However, direct peer-reviewed comparisons between soil-based and artificial media systems remain limited. Unlike inert substrates, soil-based media sustain trophic complexity by supporting soil organic matter, which provides resources for decomposer communities as well as beneficial nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi (Lunt and Hedger, 2003; Bustami et al., 2019; Droz et al., 2020). This ecological foundation underpins the greater biodiversity value of soil-based systems.

Soil-based LWS foster diverse invertebrate communities that enhance nutrient cycling, improve plant health, and provide essential prey for higher trophic groups, including birds and bats (Bray and Wickings, 2019; Chiquet et al., 2013; Tiago et al., 2024). We also found that the plant species used can significantly impact the abundance and diversity of belowground soil communities. The establishment of functional soil ecology and associated planting choices is therefore critical to the sustainability of LWS, enabling natural plant colonisation and supporting multi-trophic interactions (Fullthorpe et al., 2018).

Design choices also influence biodiversity outcomes. Soil-based substrates offer richer organic resources and structurally more complex habitats than artificial growth media (Lunt et al., 2022). For example, Madre et al. (2015) found that modular pocket systems filled with sphagnum moss supported significantly higher spider richness and abundance than felt-layer facades, climbing plant facades, or bare walls. These results were attributed to the moist microhabitats and detritivore communities sustained by the moss substrate. Beyond invertebrates, soil-based LWS provide habitat value for vertebrates. Urban birds utilise them for foraging, nesting, and shelter, while crevice-inhabiting bat species may exploit cavities behind installations (Chiquet et al., 2013; Tiago et al., 2024). Systems incorporating diverse plantings further enhance these opportunities, strengthening their role in urban wildlife conservation (Aronson et al., 2014; Tiago et al., 2024; Viritopia, 2025).

Finally, soil biodiversity underpins multiple ecosystem functions fundamental to urban greenspaces, including carbon cycling, organic matter decomposition, water regulation, and pathogen control (Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2023). These processes are closely linked to the richness and functional diversity of soil invertebrates, reinforcing the ecological importance of soil-based substrates within LWS.

Possible Approaches for Biodiversity Valuation of LWS

Our findings show that living wall systems (LWS), particularly soil-based designs, can support diverse assemblages of plants, birds, and invertebrates. Yet, both in the UK and internationally, no biodiversity valuation framework exists that adequately accounts for the ecological potential of human-designed habitats such as LWS.

Current biodiversity valuation frameworks used in development mitigation fall broadly into two categories. The first, represented by the UK Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) metric, is habitat-based: biodiversity value is determined by habitat classification, quality (e.g., naturalness or potential for creation), and area. The second category is species-based, exemplified by the Wallacea biodiversity assessment method (Wallacea Trust, 2023), the most widely applied global credit system for biodiversity recovery. This framework uses composite scoring based on species richness and abundance across at least five indicator groups, including functional taxa such as soil invertebrates and zoological groups such as birds and bees.

Development-led compliance mechanisms have significant potential to fund LWS and deliver biodiversity gains in high-density urban areas where ground space is limited. However, under the BNG metric, LWS are classified within the category Urban – Built-up Areas and Gardens, an artificial habitat type associated with non-native species and assigned low distinctiveness scores. Consequently, LWS receive minimal credit for biodiversity enhancement (Natural England, 2023a) and are currently unsuitable for offsetting habitat losses arising from new developments (Rampling et al., 2024). This reveals a clear disconnect between the demonstrated ecological value of LWS and their treatment in planning compliance frameworks.

Urban habitats that provide food and shelter for rare or legally protected species may be particularly valuable. In the UK, all bat species and their roosts are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981). While bats were observed foraging near the LWS in Plymouth, no individuals were recorded entering or emerging from the structures. This suggests that current LWS designs do not yet provide suitable roosting opportunities. Nevertheless, modular frame systems, such as the Sustainability Hub installation, show potential for supporting crevice-dwelling bats, with possible future use as hibernacula or maternity roosts (Lehrer et al., 2021). Further research is required to evaluate the conservation value of LWS for bats in urban environments.

In the absence of an appropriate valuation system, developers are unlikely to adopt LWS as biodiversity interventions and will instead seek alternative offsite options, representing a missed opportunity for urban biodiversity enhancement. Species-based valuation methods may offer a more appropriate means of assessing LWS, especially where all species are treated equally without weighting for rarity, naturalness, or native status. While these methods can be more time-intensive and costly than area-based assessments, advances in AI-powered photo and bioacoustic recognition technologies are making species surveys increasingly cost-effective and scalable (Microsoft Research, 2024).

Future valuation frameworks should also consider the full suite of ecosystem services provided by LWS, including climate regulation, aesthetic value, air pollution mitigation, natural flood management, and biodiversity support (Larcher et al., 2018). Although LWS are expensive to install and maintain and vulnerable to system failure—particularly from irrigation breakdowns—optimising their biodiversity value requires an integrated approach. This should combine careful design, species selection, faunal habitat provision, water efficiency, and maintenance, all of which are critical for building resilient, multifunctional LWS in urban landscapes.

Conclusions

Urban biodiversity is under increasing pressure from development, underscoring the need for innovative approaches that strengthen ecological resilience. LWS present a promising strategy in high-density cities where ground space is limited, yet their potential remains largely unrealised due to inadequate valuation frameworks, weak policy integration, and limited funding. Stronger alignment between biodiversity policy and local planning is required, with enforceable standards that promote green infrastructure adoption (Rampling et al., 2024).

Our findings highlight that LWS can deliver meaningful biodiversity benefits when designed with ecological principles in mind. Soil-based systems, in particular, support more complex food webs, enhance microclimatic stability, and provide critical resources for microbial, detritivore, and higher trophic communities. Plant species composition is equally important, with structural and functional diversity strongly influencing above- and belowground invertebrate assemblages and, by extension, habitat quality for birds and bats. These findings indicate that species-level or functional approaches to biodiversity valuation, such as Wallacea’s composite methodology (Wallacea Trust, 2023), may better capture the ecological contributions of LWS than area-based metrics such as the UK BNG.

To maximise their ecological value, LWS should be integrated into wider networks of urban GI to enhance connectivity and facilitate species movement. While native plantings should be prioritised, carefully selected non-native evergreens may provide valuable functional roles, particularly under changing climatic conditions.

Future research should address key knowledge gaps, including the long-term biodiversity and performance outcomes of LWS, their role in conserving priority taxa such as bats and pollinators, the ecological significance of natural colonisation and succession, and the potential for structural innovations that support bat roosting opportunities in urban environments.

Overall, LWS represent a viable but underutilised tool for biodiversity enhancement in cities. Their inclusion in planning policy, supported by robust valuation frameworks and long-term monitoring, will be essential for ensuring that urban development contributes positively to ecological resilience and the well-being of urban populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Paul Lunt and Thomas Murphy. Methodology, Paul Lunt, Thomas Murphy and James Buckley. Software Gabriel Thomas; Validation, Paul Lunt, Thomas Murphy and James Buckley; Formal Analysis, Paul Lunt, Thomas Murphy, Gabriel Thomas, Elek Churella and Suzie Mitchell; Investigation, Gabriel Thomas, Elek Churella and Suzie Mitchell; Resources, Paul Lunt, Thomas Murphy and James Buckley; Data Curation, Elek Churella, Suzie Mitchell and Grabriel Thomas; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Paul Lunt and Thomas Murphy; Writing – Review & Editing, Paul Lunt, Thomas Murphy and James Buckley; Visualization, Paul Lunt and Grabriel Thomas. Supervision, Paul Lunt, Thomas Murphy and James Buckley; Project Administration, Paul Lunt and Thomas Murphy; Funding Acquisition, Paul Lunt.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by Low Carbon Devon project. We also thank the efforts of the following undergraduate students, Jennifer Poole and Matthew Philpot who contributed to data collection efforts, as well as Spencer Collins for assistance with species ID.

References

- Aronson, M.F.J., La Sorte, F.A., Nilon, C.H., Katti, M., Goddard, M.A., Lepczyk, C.A., Warren, P.S., Williams, N.S.G., Cilliers, S., Clarkson, B., Dobbs, C., Dolan, R., Hedblom, M., Klotz, S., Kooijmans, J.L., Kühn, I., MacGregor-Fors, I., McDonnell, M., Mörtberg, U., Pyšek, P., Siebert, S., Sushinsky, J., Werner, P. and Winter, M. (2014). A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1780), p.20133330. [CrossRef]

- Aston, D. and Zhu, Y. (2020) Climate resilience and plant selection in urban greening: Implications for frost-sensitive species in temperate zones. Urban Ecology Journal, 12(2), pp.145–158.

- Benedict, M.A. and McMahon, E.T. (2006). Green Infrastructure: Linking Landscapes and Communities. Island Press.

- Belcher, R.N., Fornasari, L., Menz, S. and Schroepfer, T. (2018) Birds’ use of vegetated and non-vegetated high-density buildings—a case study of Milan. Journal of Urban Ecology, 4(1), juy001. [CrossRef]

- Biotecture Ltd. (no date) Why Hydroponics? Available at: https://www.biotecture.uk.com/design-and-specify/why-hydroponics/ (Accessed: 7 August 2025).

- Braaker, S., Ghazoul, J., Obrist, M.K. and Moretti, M. (2017) Habitat connectivity and local conditions shape taxonomic and functional diversity of arthropods on green roofs. Journal of Animal Ecology, 86(3), pp.521–531. [CrossRef]

- Bray, N. and Wickings, K. (2019) The roles of invertebrates in the urban soil microbiome. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, p.359. [CrossRef]

- Bustami, R.A., Belusko, M., Ward, J. & Beecham, S. (2019) A statistically rigorous approach to experimental design of vertical living walls for green buildings. Urban Science, 3(3), 71. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.W.F., Taylor, J.E. and Emmett, M.R. (2014) What’s “cool” in the world of green façades? How plant choice influences the cooling properties of green walls. Building and Environment, 73, pp.198–207.

- Carlon, E. and Dominoni, D.M. (2024) The role of urbanization in facilitating the introduction and establishment of non-native animal species: a comprehensive review. Journal of Urban Ecology, 10(1), juae015. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Wang, Z., Zhou, W., Zheng, Z. & Liu, Y. (2020) Spontaneous vegetation colonisation of urban vertical surfaces: Patterns, drivers and implications. Scientific Reports, 10, 16247. [CrossRef]

- Chiquet, C., Dover, J.W. and Mitchell, P. (2013) Birds and the urban environment: the value of green walls. Urban Ecosystems, 16(3), pp. 453–462. [CrossRef]

- Collins, R., Schaafsma, M. & Hudson, M.D. (2017) The value of green walls to urban biodiversity, Land Use Policy, 64, pp. 114–123. [CrossRef]

- Crooks, J.A., Ruiz, G.M. and Carlton, J.T. (2016). The role of urban and agricultural landscapes in facilitating exotic species dispersal. Biological Invasions, 18(2), pp.343–357. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Reich, P.B., Trivedi, C., Eldridge, D.J., Abades, S., Alfaro, F.D., Bastida, F., Berhe, A.A., Cutler, N.A., Gallardo, A., García-Velázquez, L., Hart, S.C., Hayes, P.E., He, J.-Z., Hseu, Z.-Y., Hu, H.-W., Kirchmair, M., Neuhauser, S., Pérez, C.A., Reed, S.C., Santos, F., Sullivan, B.W., Trivedi, P., Wang, J.-T., Weber-Grullon, L., Williams, M.A. and Singh, B.K. (2020) Multiple elements of soil biodiversity drive ecosystem functions across biomes. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4(2), pp.210–220. [CrossRef]

- Defra (2025) Understanding biodiversity net gain: Guidance on what BNG is and how it affects land managers, developers and local planning authorities. GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/understanding-biodiversity-net-gain (Accessed: 8 August 2025).

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2025) The Small Sites Metric (Statutory Biodiversity Metric): User Guide. First published February 2024, last updated 3 July 2025. [Online], available at: GOV.UK Publications (accessed 20 August 2025).

- Dunnett, N. and Kingsbury, N. (2008) Planting Green Roofs and Living Walls. Portland: Timber Press.

- Droz, A.G., Koyama, A., Zhang, J., Stephan, R., Schindlbacher, A., Rousk, J. & Frey, S.D. (2022) Drivers of fungal diversity and community biogeography differ in green roofs vs. ground soils. Environmental Microbiology, 24(12), pp. 5781–5797. [CrossRef]

- Environment Act 2021 (2021) UK Public General Acts 2021 c.30. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/30/part/6/crossheading/biodiversity-gain-in-planning/enacted (Accessed: 8 August 2025).

- Foo, J., O’Dea, R.E., Koricheva, J., Nakagawa, S. and Lagisz, M. (2021) A practical guide to question formation, systematic searching and study screening for literature reviews in ecology and evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. [CrossRef]

- Fox, M., Morewood, J., Murphy, T., Lunt, P. and Goodhew, S. (2022) Living wall systems for improved thermal performance of existing buildings. Building and Environment. [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.A. & Lorimer, J. (2011). Urban biodiversity and the geographies of everyday life. Progress in Physical Geography, 35(4), pp. 572–589.

- Francis, R.A. and Lorimer, J. (2011) Urban reconciliation ecology: The potential of living roofs and walls. Journal of Environmental Management, 92(6), pp.1429–1437.

- Fuller, R.A., Irvine, K.N., Devine-Wright, P., Warren, P.H. & Gaston, K.J. (2007). Psychological benefits of green space increase with biodiversity. Biology Letters, 3(4), pp. 390–394.

- Fulthorpe, R. et al. (2018) The green roof microbiome: improving plant survival for urban roof ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 5. [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, M., Larson, B.M.H., Irlich, U.M., Holmes, P.M., Stafford, L. & Richardson, D.M. (2016) ‘Managing invasive species in cities: a framework from Cape Town, South Africa’, Landscape and Urban Planning, 151, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Glen, A.S., Pech, R.P. & Byrom, A.E. (2013) ‘Connectivity and invasive species management: towards an integrated landscape approach’, Biological Invasions, 15, pp. 2127–2138. [CrossRef]

- Goel, M. & Sharma, R. (2022) Living walls enhancing the urban realm: a review. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 19, pp. 3511–3530. [CrossRef]

- Hecht, K., Haan, L., Wösten, H.A.B., Hamel, P., Swaminathan, S. & Jain, A. (2025). Rocks and walls: Biodiversity and temperature regulation of natural cliffs and vertical greenery systems. Building and Environment, 268, 112308. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.R. (2013) Quiet environment: Acoustics of vertical green wall systems of the Islamic urban form. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 2(2), pp.162–171.

- Ives, C.D., Lentini, P.E., Threlfall, C.G., Ikin, K., Shanahan, D.F., Garrard, G.E., Bekessy, S.A., Fuller, R.A., Mumaw, L., Rayner, L., Rodewald, R., Valentine, L.E. and Kendal, D. (2016) Cities are hotspots for threatened species. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 25(1), pp.117–126. [CrossRef]

- Köhler, M. (2008) Green facades—a view back and some visions. Urban Ecosystems, 11(4), pp.423–436.

- Larcher, F., Battisti, L., Bianco, L., Giordano, R., Montacchini, E., Serra, V. and Tedesco, S. (2018) Sustainability of Living Wall Systems Through an Ecosystem Services Lens. In: Urban Horticulture. Springer, pp.31–51.

- Law, C.M.Y., Wong, N.H., Tan, C.L., Lim, H.S. and Wong, D.K.W. (2025) Data-driven approach for optimising plant species selection and planting design on outdoor modular green walls with aesthetic, maintenance, and water-saving goals. Sustainability, 17(8), p.3528. [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, E.W., Gallo, T., Fidino, M., Kilgour, R.J., Wolff, P.J. and Magle, S.B., 2021. Urban bat occupancy is highly influenced by noise and the location of water: Considerations for nature-based urban planning. Landscape and Urban Planning, 210, p.104063. Available at: https://urbanxnaturelab.com/publications/Lehrer_etal_2021_urban-bats.pdf [Accessed 13 Aug. 2025].

- Lewandowski, D., Cortina-Segarra, J., Klein, T. & Früh, B. (2023) Bioreceptivity of living walls: Interactions between building materials and biological colonization. Building and Environment, 241, 110719. [CrossRef]

- Li, G., Fang, C. and Li, Y. (2022) Global impacts of future urban expansion on terrestrial vertebrate diversity. Nature Communications, 13, 1628. [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, J. (2006) Green roofs and facades: A habitat template approach. Urban Habitats, 4(1), pp.87-101.

- Lunt, P.H., Fuller, K., Fox, M., Goodhew, S. and Murphy, T.R. (2022) Comparing the thermal conductivity of three soil types under differing moisture and density conditions for use in green infrastructure. Soils Use & Management. [CrossRef]

- Madre, F., Clergeau, P., Machon, N. and Vergnes, A. (2015) Building Biodiversity: Vegetated Façades as Habitats for Spider and Beetle Assemblages. Global Ecology and Conservation, 3, pp.222–233.

- Manso, M. and Castro-Gomes, J. (2015) Green wall systems: A review of their characteristics. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 41, pp.863-871.

- Mayrand, F. & Clergeau, P. (2018) Green roofs and green walls for biodiversity conservation: a contribution to urban connectivity? Sustainability, 10(4), Article 985. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Research (2024) Accelerating biodiversity surveys with AI. Available at: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/project/accelerating-biodiversity-surveys/ (Accessed: 8 August 2025).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2024) National Planning Policy Framework – revised December 2024. Available at: GOV.UK (accessed 20 August 2025).

- Murphy, T.R., Hanley, M.E., Ellis, J.S. & Lunt, P.H. (2019) ‘Deviation between projected and observed precipitation trends greater with altitude’, Climate Research, 79, pp. 77–89. [CrossRef]

- Natural England (2023a) Biodiversity net gain: how to use the biodiversity metric. GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/biodiversity-net-gain (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

- Natural England (2023b) The Biodiversity Metric 4.0 Technical Annex 2 – Technical Information. Natural England Joint Publication JP039. ISBN: 978-1-7393362-3-3.

- Natural History Museum of Bern (2022) World Spider Catalog. Available at: https://wsc.nmbe.ch/statistics/ (Accessed: 7 April 2022).

- Ottelé, M., Perini, K., Fraaij, A.L.A., Haas, E.M. and Raiteri, R. (2011) Comparative life cycle analysis for green façades and living wall systems. Energy and Buildings, 43(12), pp.3419–3429. [CrossRef]

- Partridge, D.R. and Clark, J.A. (2018) Urban Green Roofs Provide Habitat for Migrating and Breeding Birds and Their Arthropod Prey. PLoS ONE, 13, e0202298.

- Perini, K., Ottelé, M., Fraaij, A.L.A., Haas, E.M. and Raiteri, R. (2013) Vertical greening systems and the effect on air flow and temperature on the building envelope. Building and Environment, 46(11), pp.2287-2294.

- Pérez-Urrestarazu, L., Fernández-Cañero, R., Franco-Salas, A. and Egea, G. (2016) Vertical greening systems and sustainable cities. Journal of Urban Technology, 23(4), pp.59-79.

- Pérez-Urrestarazu, L., Zamorano, M., Fernández-Cañero, R. and Esperanza García, M. (2021) Vertical greening systems and sustainable cities: a comprehensive review. Environmental Science and Technology, 55(4), pp.1919-1932.

- R Core Team (2025) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 20 August 2025).

- Rampling, E.E., Bull, J.W., zu Ermgassen, S.O.S.E. and Hawkins, I. (2024). Achieving biodiversity net gain by addressing governance gaps underpinning ecological compensation policies. Conservation Biology, 38(1), e14198.

- Rondeau, A., Mandon, A., Malhautier, L., Poly, F. and Richaume, A. (2012) Biopurification of air containing a low concentration of TEX: comparison of removal efficiency using planted and non-planted biofilters. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, 87, pp.746-750.

- Rooney, T. and Roberson, E. (2016) Deer herbivory reduces web-building spider abundance by simplifying forest vegetation structure. PeerJ, 4, e2538. [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, A., Armitage, J., Bostock, H., Perry, J., Tatchell, M. and Thompson, K. (2017) Enhancing gardens as habitats for plant-associated invertebrates: should we plant native or exotic species? Biodiversity and Conservation, 26, pp.2657–2673. [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, A., Blanusa, T., Bostock, H. and Perry, J.N. (2023) Careful plant choice can deliver more biodiverse vertical greening (green façades). Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 89, 128118.

- Seto, K.C., Güneralp, B. and Hutyra, L.R. (2012) Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(40), pp.16083–16088. [CrossRef]

- Scotscape (2018) Living Wall Systems: Modular Green Infrastructure for Urban Environments. Scotscape Ltd. Available at: https://www.scotscape.co.uk/our-products/living-walls (Accessed: 20 August 2025).

- Siemann, E., Tilman, D. and Haarstad, J. (1998) Experimental tests of the impacts of plant diversity on community structure and ecosystem functioning. Ecological Monographs, 68(3), pp.427–442.

- Tartaglia, E.S. and Aronson, M.F.J. (2024). Plant native: comparing biodiversity benefits, ecosystem services provisioning, and plant performance of native and non-native plants in urban horticulture. Urban Ecosystems, 27, pp.2587–2611. [CrossRef]

- Tiago, P., Leal, A.I. and Matos Silva, C. (2024) Assessing Ecological Gains: A Review of How Arthropods, Bats and Birds Benefit from Green Roofs and Walls. Environments, 11(4), 76. [CrossRef]

- Tonietto, R., Fant, J., Ascher, J., Ellis, K. and Larkin, D. (2011) A Comparison of Bee Communities of Chicago Green Roofs, Parks and Prairies. Landscape and Urban Planning, 103, pp.102–108.

- Tzoulas, K., Korpela, K., Venn, S., Yli-Pelkonen, V., Kazmierczak, A., Niemelä, J. and James, P. (2007) Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 81(3), pp.167–178. [CrossRef]

- United Nations (2018) Department of Economics and Social Affairs – Population Dynamics. World Urbanization prospects 2018. Available at: https://population.un.org/wup/Download/ (Accessed: 9 November 2023).

- Uthappa, A.R., Shishira, D., Chavan, S. & Kumar, M., 2022. Soil arthropods and their role in soil health sustenance. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362301891_Soil_arthropods_and_their_role_in_soil_health_sustenance [Accessed 13 Aug. 2025].

- Viritopia (2025) Living walls and biodiversity: how vertical gardens support urban wildlife. Available at: https://www.viritopia.com/living-wall (Accessed: 8 August 2025).

- Voigt, A., Kabisch, N., Wurster, D., Haase, D. and Breuste, J. (2014) Structural diversity: a multi-dimensional approach to assess recreational services in urban parks. Ambio, 43, pp.480–491. [CrossRef]

- Wallacea Trust. (2023). Species-level biodiversity assessment methodology. [Online] Available at: https://wallaceatrust.org.

- Wallacea Trust (2023) Methodology for Quantifying Units of Biodiversity Gain (Version 3, October 2023). Available at: https://wallaceatrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Biodiversity-credit-methodology-V3.pdf (Accessed: 7 August 2025).

- Weiler, S.K. and Scholz-Barth, K. (2009) Green Roof Systems: A Guide to the Planning, Design, and Construction of Building Over Structure. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Wickham, H., 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. Available at: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).