Submitted:

12 March 2024

Posted:

13 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What aspects of the synanthropic plant species perception increase the overall residents’ acceptance of these plants in urban spaces?

- How do perceptions of synanthropic plants differ in terms of the demographic profile of respondents?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants and Questionnaire

2.2. Statistical Analysis

- -

- X1 - The use of synanthropic vegetation found in turfgrasses has a positive impact on the visual attractiveness of a site.

- -

- X2 - Synanthropic plant communities present themselves better than others.

- -

- X3 - The presence of synanthropic vegetation in Your estate improves the quality of life in that location.

- -

- X4 - The introduction of synanthropic plants into estate arrangements is a positive.

- -

- X5 - I support the use of synanthropic plants for educational purposes - as elements of playgrounds or in the form of environmental workshops.

2.3. Characteristics of Respondents

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pochodyła, E.; Jaszczak, A.; Illes, J.; Kristianova, K.; Joklova, V. Analysis of green infrastructure and nature-based solutions in Warsaw– selected aspects for planning urban space. Acta Horticulturae et Regiotecturae 2022, 25(1), 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Wittig, R.; Becker, U. The spontaneous flora around street trees in cities—A striking example for the worldwide homogenization of the flora of urban habitats. Flora-Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2010, 205, 704–709. [CrossRef]

- Vega, K.A.; Küffer, C. Promoting wildflower biodiversity in dense and green cities: The important role of small vegetation patches. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 62, 127165. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C.; Livesley, S.J.; Arndt, S.K.; Beaumont, L.; Burley, H.; Ellsworth, D.; Esperon-Rodriguez, M.; Fletcher, T.D.; Gallagher, R.; Ossola, A.; Power, S.A. Can we integrate ecological approaches to improve plant selection for green infrastructure? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2022, 76, 127732. [CrossRef]

- Catalano, C.; Marcenò, C.; Laudicina, V.A.; Guarino, R. Thirty years unmanaged green roofs: Ecological research and design implications. Landscape and Urban Planning 2016, 149, 11-19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, S.; Fan, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, L.; Wu, J.; Zhao, H. Is sustainable extensive green roof realizable without irrigation in a temperate monsoonal climate? A case study in Beijing. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 753, 142067. [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, J.T. Spontaneous dynamics and wild design in green roofs. Israel Journal of Ecology and Evolution 2016, 62(1-2), 23-31. [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, M.K.; Iwachido, Y.; Sun, X.; Maehara, K.; Kawata, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Tsuchihashi, Y.; Sasaki, T. Overlooked plant diversity in urban streetscapes in Oulu and Yokohama. Global Ecology and Conservation 2023, 46, e02621. [CrossRef]

- Schrieke, D.; Lönnqvist, J.; Blecken, G. T.; Williams, N. S.; Farrell, C. Socio-Ecological Dimensions of Spontaneous Plants on Green Roofs. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 2021, 3, 777128. [CrossRef]

- Greene, B.; Walls, W. Wood for the trees: Design and policymaking of urban forests in Berlin and Melbourne. Journal of Landscape Architecture 2023, 18(1), 94-103. [CrossRef]

- Kamionowski, F.; Fornal-Pienak, B.; Bihuňová, M. Application of synanthropic plants in the design of green spaces in Warsaw (Poland). Acta Horticulturae et Regiotecturae 2023, 26(2), 168-172. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Koda, E.; Červenová, J.; Napieraj, K.; Żółtowski, M.; Jakimiuk, A.; Podlasek, A.; Vaverková, M.D. Fragmentation and biodiversity change in urban vegetation: A case study of tram lines. Land Degradation & Development 2024, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y. Green roof evolution through exemplars: Germinal prototypes to modern variants. Sustainable cities and society 2017, 35, 69-82. [CrossRef]

- Rafflegeau, S.; Gosme, M.; Barkaoui, K.; Garcia, L.; Allinne, C.; Deheuvels, O.; Grimaldi, J.; Jagoret, P.; Lauri, P.; Merot, A.; Metay, A.; Reyes, F.; Saj, S.; Curry, G.N.; Justes, E. The ESSU concept for designing, modeling and auditing ecosystem service provision in intercropping and agroforestry systems. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2023, 43(4), 43. [CrossRef]

- RHS. Available online: https://www.rhs.org.uk/shows-events/rhs-hampton-court-palace-garden-festival/gardens/2022/what-does-not-burn (accessed on 31.01.2024).

- RHS. Available online: https://www.rhs.org.uk/shows-events/rhs-chelsea-flower-show/news/2023/trends-themes-chelsea-2023 (accessed on 31.01.2024).

- Stakelienė, V.; Pašakinskienė, I.; Ložienė, K.; Ryliškis, D.; & Skridaila, A. Vertical columns with sustainable green cover: meadow plants in urban design. Plants 2023, 12(3), 636. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.K.; von der Lippe, M.; Rillig, M.C.; Kowarik, I. Creating novel urban grasslands by reintroducing native species in wasteland vegetation. Biological Conservation 2013, 159, 119-126. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.R.; Su, M.H.; Li, Y.H.; Chen, M.C. A proposed framework for a social-ecological traits database for studying and managing urban plants and assessing the potential of database development using Floras. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2024, 91, 128167. [CrossRef]

- Straka, T.M.; Mischo, M.; Petrick, K.J.S.; Kowarik, I. Urban Cemeteries as Shared Habitats for People and Nature: Reasons for Visit, Comforting Experiences of Nature, and Preferences for Cultural and Natural Features. Land 2022, 11, 1237. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.H.; Yue, Z.E.J.; Ling, S.K.; Tan, H.H.V. It’s ok to be wilder: Preference for natural growth in urban green spaces in a tropical city. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 38, 165-176. [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Kowarik, I.; Säumel, I. A walk on the wild side: Perceptions of roadside vegetation beyond trees. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2014, 13(2), 205-212. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lu, Y.; Jia, J.; Chen, Y.; Xue, J.; Liang, H. Urban spontaneous vegetation helps create unique landsenses. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 2021, 28(7), 593-601. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.P.; Fernandes, C.O.; Ryan, R.; Ahern, J. Attitudes and preferences towards plants in urban green spaces: Implications for the design and management of Novel Urban Ecosystems. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 314, 115103. [CrossRef]

- Mathey, J.; Arndt, T.; Banse, J.; Rink, D. Public perception of spontaneous vegetation on brownfields in urban areas—Results from surveys in Dresden and Leipzig (Germany). Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2018, 29, 384-392. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.P.; Fan, S.X.; Kühn, N.; Dong, L.; Hao, P.Y. Residents’ ecological and aesthetical perceptions toward spontaneous vegetation in urban parks in China. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 44, 126397. [CrossRef]

- de Val, G.D.L.F. The effect of spontaneous wild vegetation on landscape preferences in urban green spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2023, 81, 127863. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.; Lindquist, M. Just weeds? Comparing assessed and perceived biodiversity of urban spontaneous vegetation in informal greenspaces in the context of two American legacy cities. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 62, 127151. [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, P.; Wińska-Krysiak, M.; Chormański, J.; Krauze, K.; Kubacka, K.; Sikorska, D. Low-maintenance green tram tracks as a socially acceptable solution to greening a city. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2018, 35, 148–164. [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J.; Padullés Cubino, J.; Pearse, W.D.; Hobbie, S.E.; Lange, A.J.; Knapp, S.; Nelson, K.C. Horticultural availability and homeowner preferences drive plant diversity and composition in urban yards. Ecological Applications 2020, 30(4), e02082. [CrossRef]

- Bonthoux, S.; Chollet, S.; Balat, I.; Legay, N.; Voisin, L. Improving nature experience in cities: What are people's preferences for vegetated streets?. Journal of environmental management 2019, 230, 335-344. [CrossRef]

- de Snoo, G.R.; van Dijk, J.; Vletter, W.; Musters, C.J.M. People’s appreciation of colorful field margins in intensively used arable landscapes and the conservation of plants and invertebrates. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2023, 43(6), 80. [CrossRef]

- Brun, M.; Di Pietro, F.; Bonthoux, S. Residents’ perceptions and valuations of urban wastelands are influenced by vegetation structure. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2018, 29, 393-403. [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Iwankowski, P. Where do we want to see other people while relaxing in a city park? Visual relationships with park users and their impact on preferences, safety and privacy. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2021, 73, 101532. [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Iwankowski, P. Why is dense vegetation in city parks unpopular? The mediative role of sense of privacy and safety. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 59, 126988. [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Zalewska, K.; Pardela, Ł.; Adamczak, E.; Cenarska, A.; Bławicka, K.; Brzegowa, B.; Matiiuk, A. How the amount of greenery in city parks impacts visitor preferences in the context of naturalness, legibility and perceived danger. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 228, 104556. [CrossRef]

- Pardela, Ł.; Lis, A.; Zalewska, K.; Iwankowski, P. How vegetation impacts preference, mystery and danger in fortifications and parks in urban areas. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 228, 104558. [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, C.; Xue, D.; Liu, J.; Jin, K.; Wang, Y.; Gao, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiu, L.; Gao, T. Lawn or spontaneous groundcover? Residents’ perceptions of and preferences for alternative lawns in Xianyang, China. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14, 1259920. [CrossRef]

- Vissoh, P.V.; Mongbo, R.; Gbèhounou, G.; Hounkonnou, D.; Ahanchédé, A.; Röling, N.; Kuyper, T.W. The social construction of weeds: different reactions to an emergent problem by farmers, officials and researchers. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 2007, 5(2-3), 161-175. [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; He, W.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X. Awareness of Spontaneous Urban Vegetation: Significance of Social Media-Based Public Psychogeography in Promoting Community Climate-Resilient Construction: A Technical Note. Atmosphere 2023, 14(11), 1691. [CrossRef]

- Łąka. Available online: https://laka.org.pl/laki/badania/ (accessed on 31.01.2024). [In Polish].

- Fundacja Krajobrazy. Available online: http://fundacjakrajobrazy.pl/szkolenie-zachwyt-nad-chaszczami-czyli-o-bioroznorodnosci-i-nie-tylko/ (accessed on 31.01.2024). [In Polish].

- A&B. Available online: https://www.architekturaibiznes.pl/rabaty-pelne-chwastow,23684.html (accessed on 31.01.2024). [In Polish].

| Gender | |||

| Female | Male | ||

| 71.36 | 28.64 | ||

| Age | |||

| 18-25 | 26-35 | 36-55 | Over 55 |

| 63.76 | 7.16 | 22.37 | 6.71 |

| Education | |||

| Primary | Vocational | Secondary | Higher |

| 8.05 | 3.36 | 54.81 | 33.78 |

| Place of residence | |||

| Countrysides | Towns up to 100 thous. Inhabitants | Towns between 100 and 500 thous. inhabitants | Towns over 500 thous. inhabitants |

| 20.13 | 24.16 | 9.84 | 45.86 |

| Per Capita Income PLN (EUR)1 | |||

| No answer | Under 2500 PLN (576.15EUR) |

2501-4500 PLN (576.16 -1037.06EUR) |

Over 4500 PLN (1037.06EUR) |

| 9.40 | 25.06 | 38.03 | 27.52 |

| Variables | assessment b | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The use of synanthropic vegetation found in turfgrasses has a positive impact on the visual attractiveness of a site | X1 | 0.1604 | 0.0000 |

| Synanthropic plant communities present themselves better than others | X2 | 0.0771 | 0.0272 |

| The presence of synanthropic vegetation in Your estate improves the quality of life in that location | X3 | 0.1403 | 0.0003 |

| The introduction of synanthropic plants into estate arrangements is a positive | X4 | 0.3085 | 0.0000 |

| I support the use of synanthropic plants for educational purposes - as elements of playgrounds or in the form of environmental workshops | X5 | 0.2840 | 0.0000 |

| constant | 0.3160 |

| Variables | Men | Women | Z-value U Mann–Whitney test men vs woman | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of acceptance of synanthropic vegetation in urban greenery (Yw) | 3.98 | 4.19 | -1.9 | 0.060 |

| The use of synanthropic vegetation found in turfgrasses has a positive impact on the visual attractiveness of a site (X1) | 3.66 | 3.83 | -1.27 | 0.203 |

| Synanthropic plant communities present themselves better than others (X2) | 3.20 | 3.15 | 0.39 | 0.695 |

| The presence of synanthropic vegetation in Your estate improves the quality of life in that location (X3) | 3.53 | 3.85 | -2.74 | 0.006 |

| The introduction of synanthropic plants into estate arrangements is a positive (X4) | 3.82 | 4.15 | -3.16 | 0.002 |

| I support the use of synanthropic plants for educational purposes - as elements of playgrounds or in the form of environmental workshops (X5) | 3.96 | 4.26 | -2.64 | 0.008 |

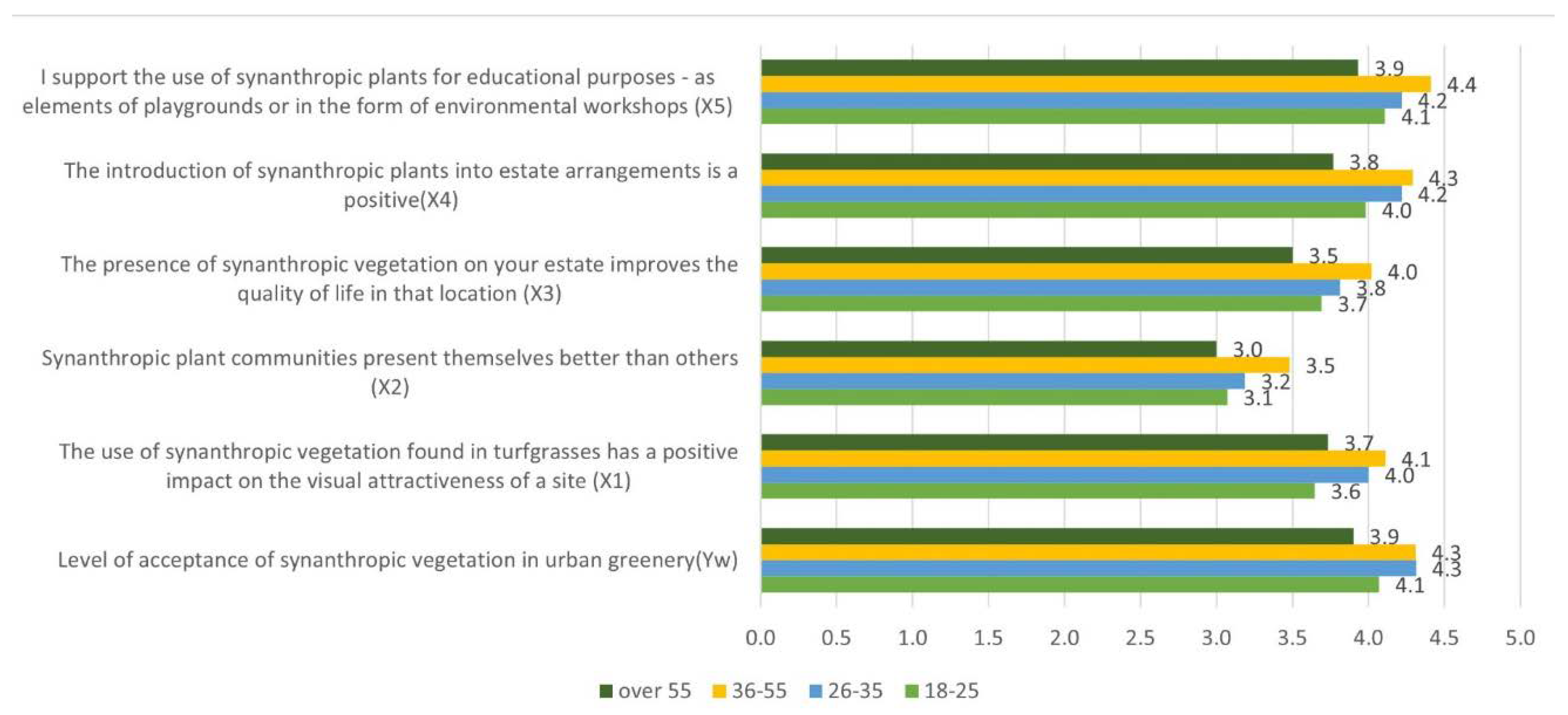

| Statements | Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-value U Mann–Whitney test for pairs age groups | H-value Kruskal-Wallis test for age | ||||

| 26-35 | 36-55 | Over 55 | |||

| Level of acceptance of synanthropic vegetation in urban greenery (Yw) | 18-25 | 1.51 | 2.20 | 0.72 | 8.77* |

| 26-35 | 0.13 | 1.65 | |||

| 36-55 | 1.89 | ||||

| The use of synanthropic vegetation found in turfgrasses has a positive impact on the visual attractiveness of a site (X1) | 18-25 | 1.95 | 3.70* | 0.52 | 16.92* |

| 26-35 | 0.33 | 1.04 | |||

| 36-55 | 0.33 | 1.59 | |||

| Synanthropic plant communities present themselves better than others (X2) | 18-25 | 0.37 | 3.24* | 0.39 | 12.50* |

| 26-35 | 1.51 | 0.57 | |||

| 36-55 | 2.17 | ||||

| The presence of synanthropic vegetation in Your estate improves the quality of life in that location (X3) | 18-25 | 0.88 | 2.82* | 0.67 | 10.27* |

| 26-35 | 0.81 | 1.15 | |||

| 36-55 | 2.20 | ||||

| The introduction of synanthropic plants into estate arrangements is a positive (X4) | 18-25 | 1.58 | 2.72* | 0.97 | 12.43* |

| 26-35 | 0.10 | 1.89 | |||

| 36-55 | 2.42 | ||||

| I support the use of synanthropic plants for educational purposes - as elements of playgrounds or in the form of environmental workshops (X5) | 18-25 | 1.26 | 3.21* | 0.23 | 13.70* |

| 26-35 | 0.68 | 1.10 | |||

| 36-55 | 2.01 | ||||

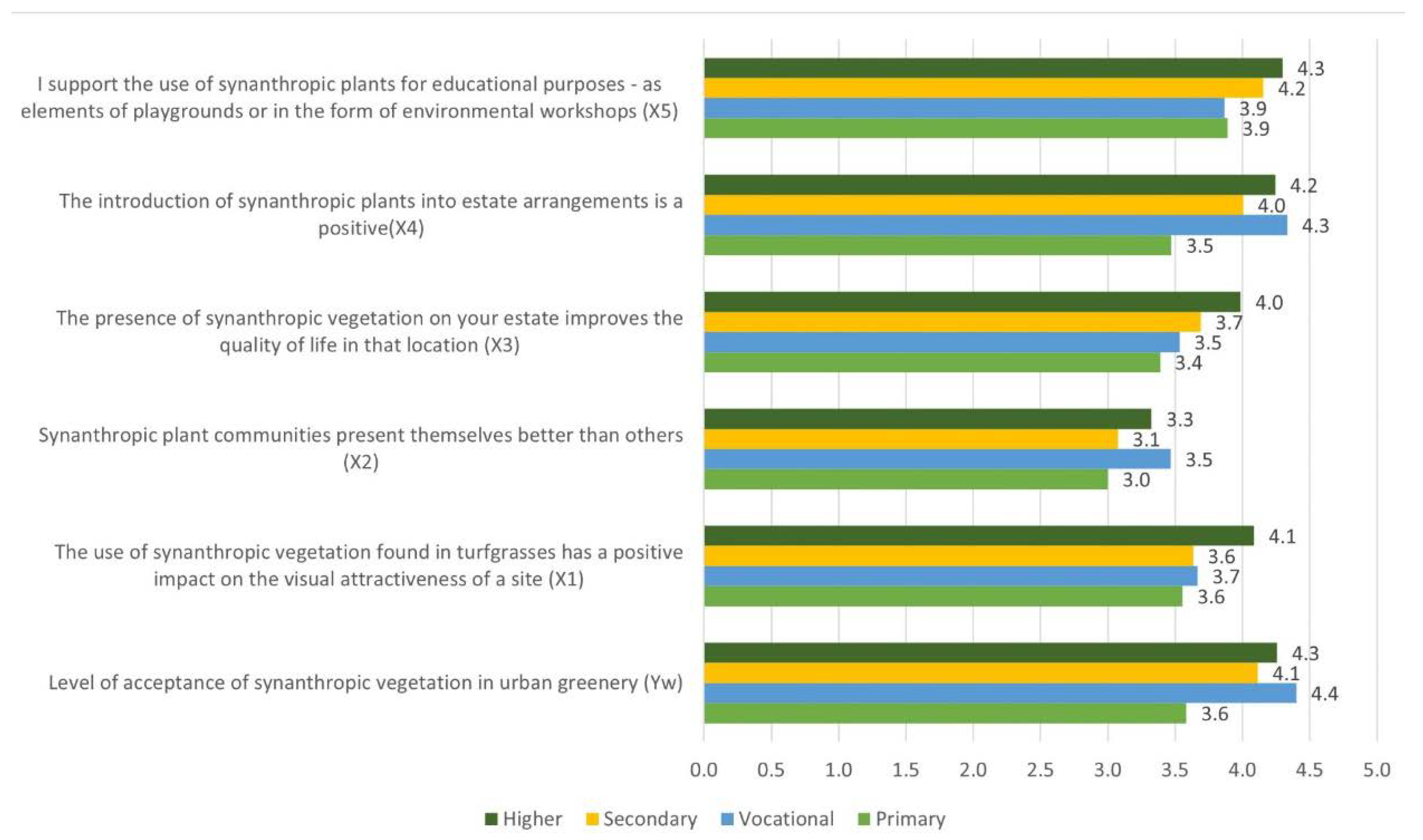

| Statements | Education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U Mann–Whitney test for pairs education groups | Kruskal-Wallis for education | ||||

| Vocational | Secondary | Higher | |||

| Level of acceptance of synanthropic vegetation in urban greenery (Yw) | Primary | 1.51 | 2.20 | 0.72 | 8.77* |

| Vocational | 0.13 | 1.65 | |||

| Secondary | 1.89 | ||||

| The use of synanthropic vegetation found in turfgrasses has a positive impact on the visual attractiveness of a site (X1) | Primary | 2.29 | 2.12 | 2.99 | 12.40* |

| Vocational | 1.23 | 0.56 | |||

| Secondary | 1.70 | ||||

| Synanthropic plant communities present themselves better than others (X2) | Primary | 1.46 | 0.46 | 1.54 | 6.65 |

| Vocational | 1.37 | 0.60 | |||

| Secondary | 1.96 | ||||

| The presence of synanthropic vegetation in Your estate improves the quality of life in that location (X3) | Primary | 0.49 | 1.32 | 2.81* | 12.84* |

| Vocational | 0.32 | 1.36 | |||

| Secondary | 2.75* | ||||

| The introduction of synanthropic plants into estate arrangements is a positive (X4) | Primary | 2.68* | 2.55 | 3.84* | 19.95* |

| Vocational | 1.38 | 0.41 | |||

| Secondary | 2.48 | ||||

| I support the use of synanthropic plants for educational purposes - as elements of playgrounds or in the form of environmental workshops (X5) | Primary | 0.25 | 1.11 | 2.32 | 9.77* |

| Vocational | 0.45 | 1.30 | |||

| Secondary | 2.24 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).