Submitted:

17 July 2024

Posted:

19 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Sampling sites

- DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing

- Bioinformatic processing and data analysis

- Taxonomic assignment

- Coding sequence prediction and functional annotation

- Statistical analyses and data processing

3. Results

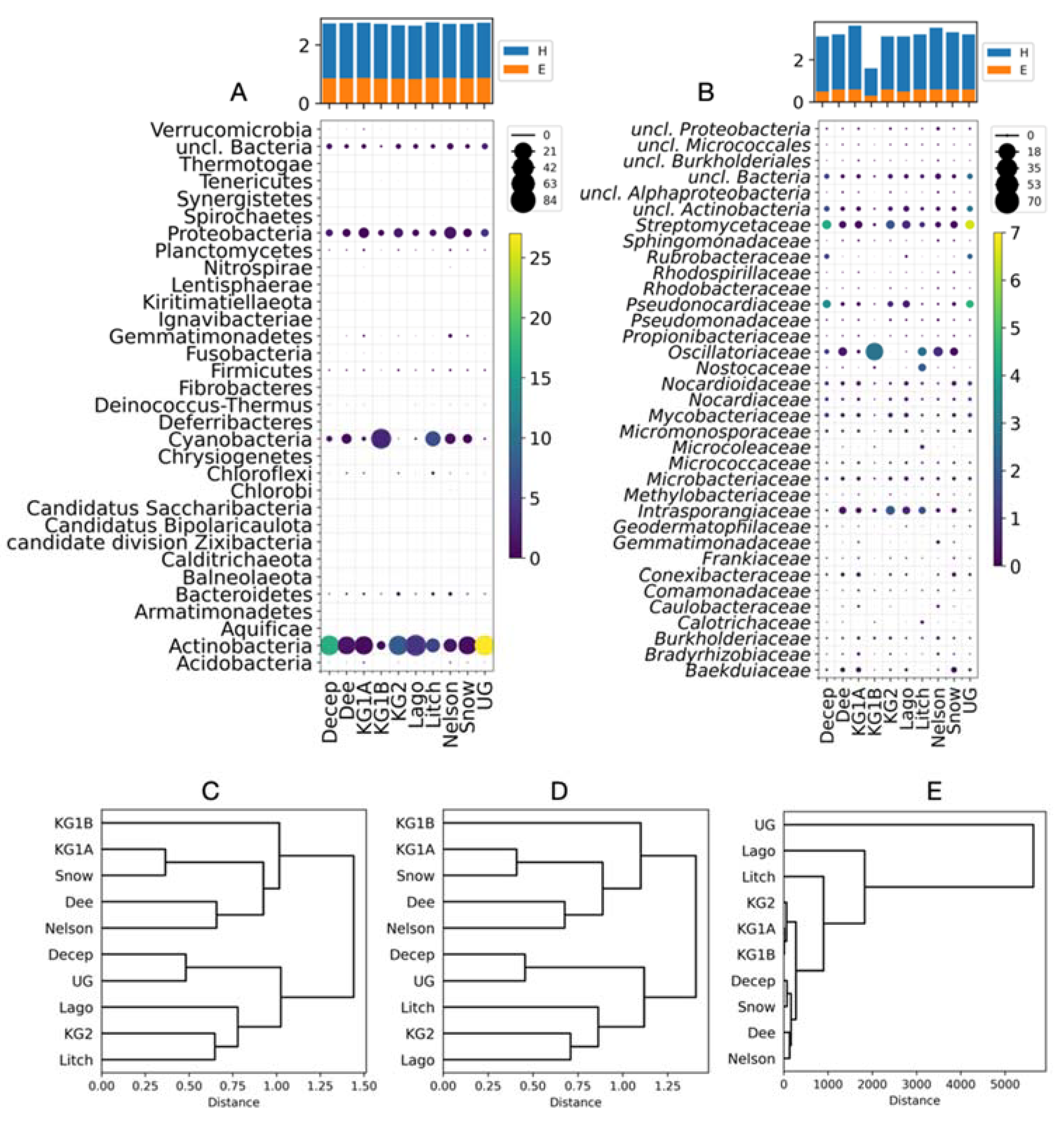

- Analysis of bacterial taxa in soils from different Antarctic sites

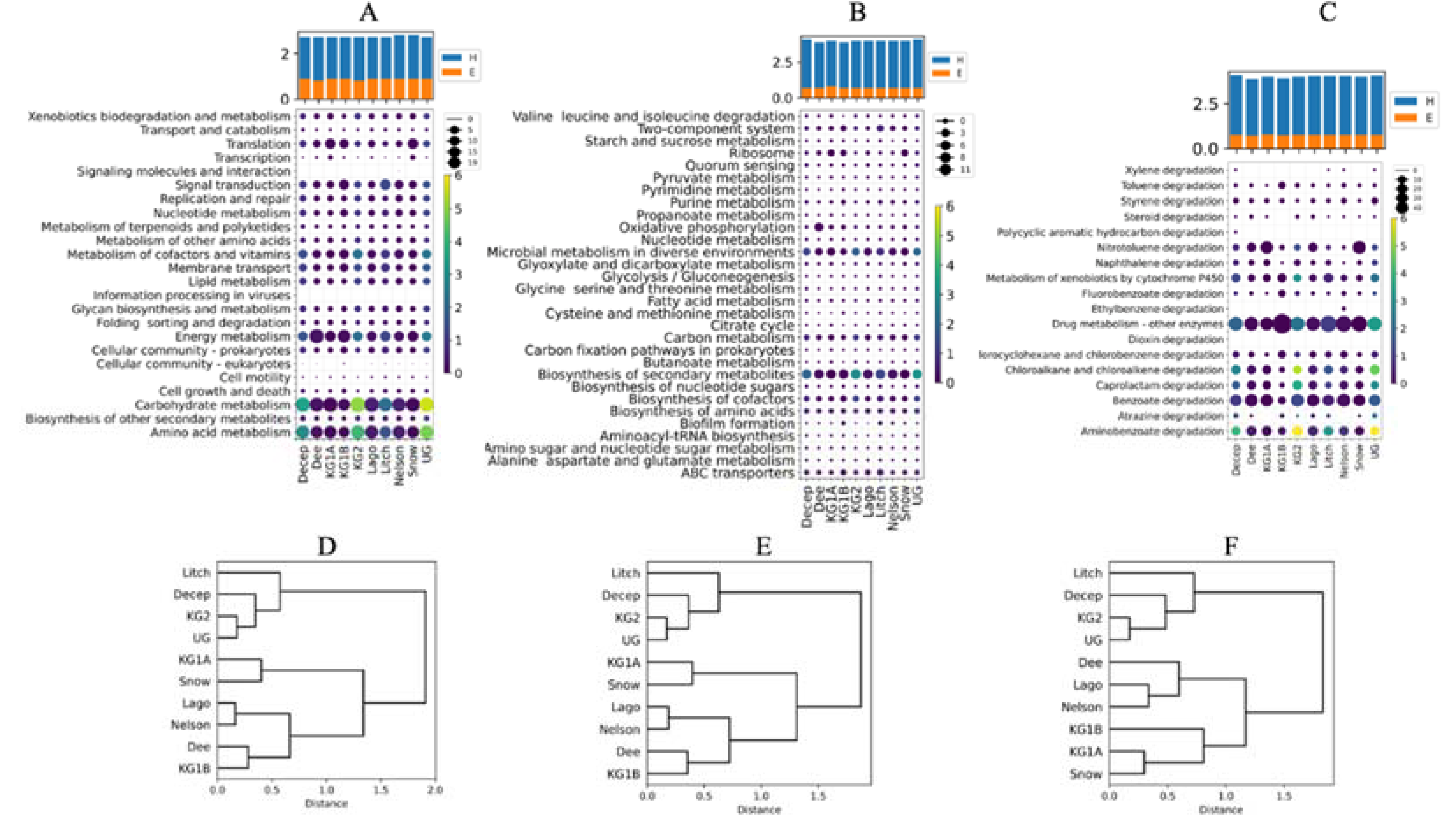

- Metabolic potential of soils from different Antarctic sites

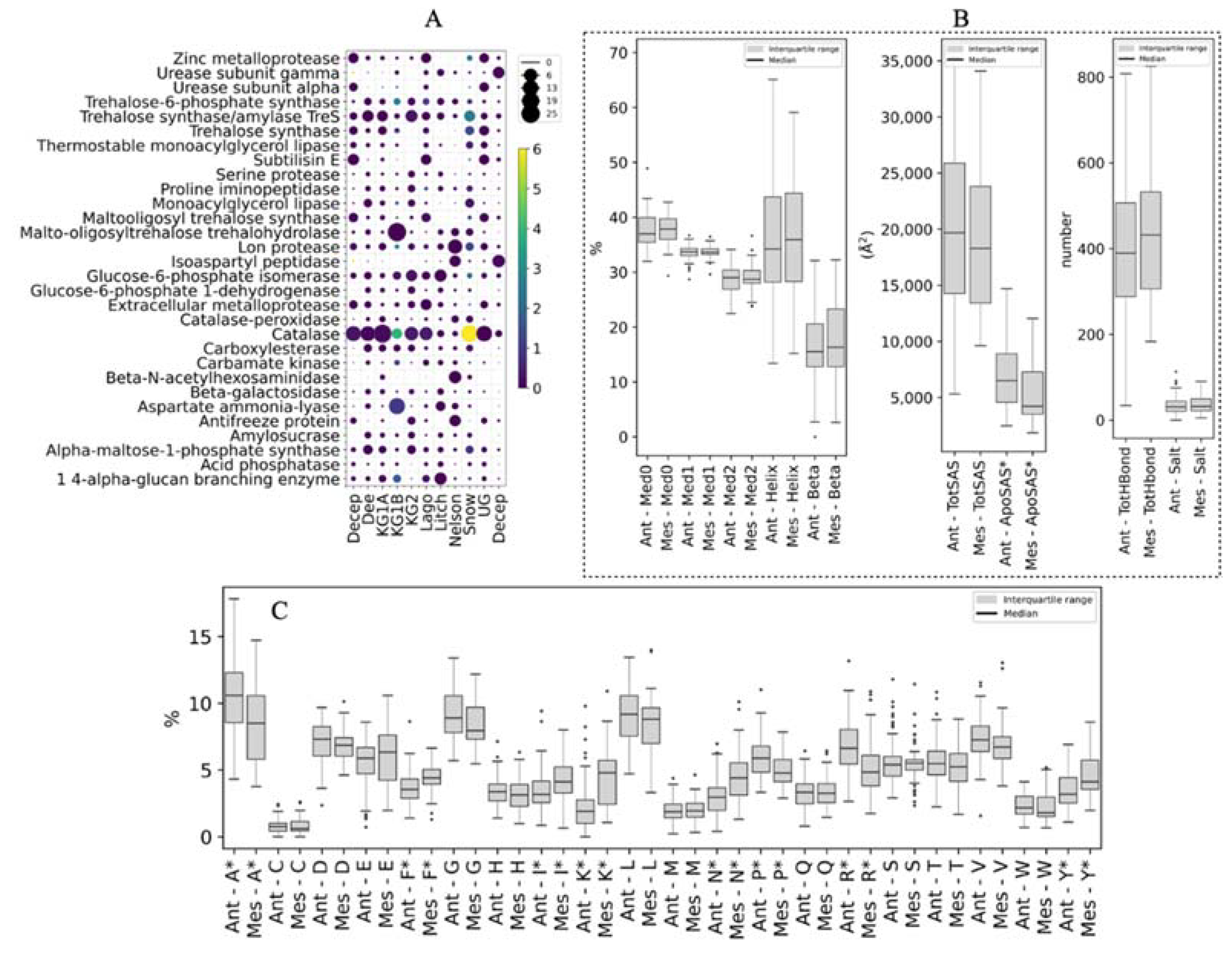

- Gene mining for putative enzymes with potential applications and protein structure analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cowan DA, Tow LA: Endangered Antarctic Environments. Annu Rev Microbiol 2004, 58, 649–690. [CrossRef]

- Terauds A, Chown SL, Morgan F, J. Peat H, Watts DJ, Keys H, Convey P, Bergstrom DM: Conservation biogeography of theAntarctic. Diversity and Distributions 2012, 18:726-741. [CrossRef]

- Lee JR, Raymond B, Bracegirdle TJ, Chadès I, Fuller RA, Shaw JD, Terauds A: Climate change drives expansion of Antarctic ice-free habitat. Nature 2017, 547:49-54. [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts S, Willems A, Tahon G: Uncovering the Uncultivated Majority in Antarctic Soils: Toward a Synergistic Approach. Front Microbiol 2019, 10:242. [CrossRef]

- Margesin R, Miteva V: Diversity and ecology of psychrophilic microorganisms. Res Microbiol 2011, 162:346-361. [CrossRef]

- Stan-Lotter H, Fendrihan S: Adaption of Microbial Life to Environmental Extremes Springer; 2017.

- Baeza M, Flores O, Alcaíno J, Cifuentes V: Yeast Thriving in Cold Terrestrial Habitats: Biodiversity and Industrial/Biotechnological Applications. In Fungi in Extreme Environments: Ecological Role and Biotechnological Significance Edited by Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019:253-268.

- Solden L, Lloyd K, Wrighton K: The bright side of microbial dark matter: lessons learned from the uncultivated majority. Curr Opin Microbiol 2016, 31, 217–226. [CrossRef]

- Wang NF, Zhang T, Zhang F, Wang ET, He JF, Ding H, Zhang BT, Liu J, Ran XB, Zang JY: Diversity and structure of soil bacterial communities in the Fildes Region (maritime Antarctica) as revealed by 454 pyrosequencing. Front Microbiol 2015, 6:1188. [CrossRef]

- Baeza M, Alcaíno J, Cifuentes V, Turchetti B, Buzzini P: Cold-Active Enzymes from Cold-Adapted Yeasts. In Biotechnology of Yeasts and Filamentous Fungi Edited by Sibirny AA. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017:297-324.

- Feeser KL, Van Horn DJ, Buelow HN, Colman DR, McHugh TA, Okie JG, Schwartz E, Takacs-Vesbach CD: Local and Regional Scale Heterogeneity Drive Bacterial Community Diversity and Composition in a Polar Desert. Front Microbiol 2018, 9:1928. [CrossRef]

- Rogers SO, Shtarkman YM, Koçer ZA, Edgar R, Veerapaneni R, D’Elia T: Ecology of subglacial lake vostok (antarctica), based on metagenomic/metatranscriptomic analyses of accretion ice. Biology (Basel) 2013, 2:629-650. [CrossRef]

- Pearce DA, Newsham KK, Thorne MA, Calvo-Bado L, Krsek M, Laskaris P, Hodson A, Wellington EM: Metagenomic analysis of a southern maritime antarctic soil. Front Microbiol 2012, 3:403. [CrossRef]

- Lopatina A, Medvedeva S, Shmakov S, Logacheva MD, Krylenkov V, Severinov K: Metagenomic Analysis of Bacterial Communities of Antarctic Surface Snow. Front Microbiol 2016, 7:398. [CrossRef]

- Alves Junior N, Meirelles PM, de Oliveira Santos E, Dutilh B, Silva GG, Paranhos R, Cabral AS, Rezende C, Iida T, de Moura RL, Kruger RH, Pereira RC, Valle R, Sawabe T, Thompson C, Thompson F: Microbial community diversity and physical-chemical features of the Southwestern Atlantic Ocean. Arch Microbiol 2015, 197:165-179. [CrossRef]

- Ogaki MB, Câmara PEAS, Pinto OHB, Lirio JM, Coria SH, Vieira R, Carvalho-Silva M, Convey P, Rosa CA, Rosa LH: Diversity of fungal DNA in lake sediments on Vega Island, north-east Antarctic Peninsula assessed using DNA metabarcoding. Extremophiles 2021, 25:257-265. [CrossRef]

- Rosa LH, Ogaki MB, Lirio JM, Vieira R, Coria SH, Pinto OHB, Carvalho-Silva M, Convey P, Rosa CA, Câmara PEAS: Fungal diversity in a sediment core from climate change impacted Boeckella Lake, Hope Bay, north-eastern Antarctic Peninsula assessed using metabarcoding. Extremophiles 2022, 26:16. [CrossRef]

- de Souza LMD, Ogaki MB, Câmara PEAS, Pinto OHB, Convey P, Carvalho-Silva M, Rosa CA, Rosa LH: Assessment of fungal diversity present in lakes of Maritime Antarctica using DNA metabarcoding: a temporal microcosm experiment. Extremophiles 2021, 25:77-84. [CrossRef]

- da Silva TH, Câmara PEAS, Pinto OHB, Carvalho-Silva M, Oliveira FS, Convey P, Rosa CA, Rosa LH: Diversity of Fungi Present in Permafrost in the South Shetland Islands, Maritime Antarctic. Microb Ecol 2022, 83:58-67. [CrossRef]

- Rosa LH, Pinto OHB, Convey P, Carvalho-Silva M, Rosa CA, Câmara PEAS: DNA Metabarcoding to Assess the Diversity of Airborne Fungi Present over Keller Peninsula, King George Island, Antarctica. Microb Ecol 2021, 82:165-172. [CrossRef]

- Pudasaini S, Wilson J, Ji M, van Dorst J, Snape I, Palmer AS, Burns BP, Ferrari BC: Microbial Diversity of Browning Peninsula, Eastern Antarctica Revealed Using Molecular and Cultivation Methods. Front Microbiol 2017, 8:591. [CrossRef]

- Silva JB, Centurion VB, Duarte AWF, Galazzi RM, Arruda MAZ, Sartoratto A, Rosa LH, Oliveira VM: Unravelling the genetic potential for hydrocarbon degradation in the sediment microbiome of Antarctic islands. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2022, 99:fiac143. [CrossRef]

- Gerday C: Fundamentals of Cold-Active Enzymes. In Cold-adapted Yeasts: Biodiversity, Adaptation Strategies and Biotechnological Significance Edited by Buzzini P, Margesin R. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2014:325-350.

- Parvizpour S, Hussin N, Shamsir MS, Razmara J: Psychrophilic enzymes: structural adaptation, pharmaceutical and industrial applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105:899-907. [CrossRef]

- Alcaíno J, Cifuentes V, Baeza M: Physiological adaptations of yeasts living in cold environments and their potential applications. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 31:1467-1473. [CrossRef]

- Feller G: Psychrophilic enzymes: from folding to function and biotechnology. Scientifica (Cairo) 2013, 2013:512840. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Moon CD, Zheng N, Huws S, Zhao S, Wang J: Opportunities and challenges of using metagenomic data to bring uncultured microbes into cultivation. Microbiome 2022, 10:76. [CrossRef]

- Sharpton TJ: An introduction to the analysis of shotgun metagenomic data. Front Plant Sci 2014, 5:209. [CrossRef]

- Frioux C, Singh D, Korcsmaros T, Hildebrand F: From bag-of-genes to bag-of-genomes: metabolic modelling of communities in the era of metagenome-assembled genomes. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2020, 18:1722-1734. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco M, Rozas JM, Barahona S, Alcaíno J, Cifuentes V, Baeza M: Diversity and extracellular enzymatic activities of yeasts isolated from King George Island, the sub-Antarctic region. BMC Microbiol 2012, 12:251. [CrossRef]

- Barahona S, Yuivar Y, Socias G, Alcaíno J, Cifuentes V, Baeza M: Identification and characterization of yeasts isolated from sedimentary rocks of Union Glacier at the Antarctica. Extremophiles 2016, 20:479-491. [CrossRef]

- Troncoso E, Barahona S, Carrasco M, Villarreal P, Alcaíno J, Cifuentes V, Baeza M: Identification and characterization of yeasts isolated from the South Shetland Islands and the Antarctic Peninsula. Polar Biol 2017, 40:649-658. [CrossRef]

- Baeza M, Barahona S, Alcaíno J, Cifuentes V: Amplicon-Metagenomic Analysis of Fungi from Antarctic Terrestrial Habitats. Front Microbiol 2017, 8:35. [CrossRef]

- FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/.

- fastqc (accessed XXX). [http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc].

- BBTools. http://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/. [http://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/.

- Li D, Luo R, Liu CM, Leung CM, Ting HF, Sadakane K, Yamashita H, Lam TW: MEGAHIT v1.0: A fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods 2016, 102:3-11. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Liu CM, Luo R, Sadakane K, Lam TW: MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31:1674-1676. [CrossRef]

- Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W: Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 2011, 27:578-579. [CrossRef]

- Bradnam KR, Fass JN, Alexandrov A, Baranay P, Bechner M, Birol I, Boisvert S, Chapman JA, Chapuis G, Chikhi R, Chitsaz H, Chou WC, Corbeil J, Del Fabbro C, Docking TR, Durbin R, Earl D, Emrich S, Fedotov P, Fonseca NA, Ganapathy G, Gibbs RA, Gnerre S, Godzaridis E, Goldstein S, Haimel M, Hall G, Haussler D, Hiatt JB, Ho IY, Howard J, Hunt M, Jackman SD, Jaffe DB, Jarvis ED, Jiang H, Kazakov S, Kersey PJ, Kitzman JO, Knight JR, Koren S, Lam TW, Lavenier D, Laviolette F, Li Y, Li Z, Liu B, Liu Y, Luo R, Maccallum I, Macmanes MD, Maillet N, Melnikov S, Naquin D, Ning Z, Otto TD, Paten B, Paulo OS, Phillippy AM, Pina-Martins F, Place M, Przybylski D, Qin X, Qu C, Ribeiro FJ, Richards S, Rokhsar DS, Ruby JG, Scalabrin S, Schatz MC, Schwartz DC, Sergushichev A, Sharpe T, Shaw TI, Shendure J, Shi Y, Simpson JT, Song H, Tsarev F, Vezzi F, Vicedomini R, Vieira BM, Wang J, Worley KC, Yin S, Yiu SM, Yuan J, Zhang G, Zhang H, Zhou S, Korf IF: Assemblathon 2: evaluating de novo methods of genome assembly in three vertebrate species. Gigascience 2013, 2:10. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 GPDPS: The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25:2078-2079. [CrossRef]

- Wood DE, Salzberg SL: Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol 2014, 15:R46. [CrossRef]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215:403-410. [CrossRef]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL: BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10:421. [CrossRef]

- Federhen S: The NCBI Taxonomy database. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40:D136-D143. [CrossRef]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A: Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28:1647-1649. [CrossRef]

- Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL: Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007, 23:673-679. [CrossRef]

- Delcher AL, Harmon D, Kasif S, White O, Salzberg SL: Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res 1999, 27:4636-4641.

- Stanke M, Tzvetkova A, Morgenstern B: AUGUSTUS at EGASP: using EST, protein and genomic alignments for improved gene prediction in the human genome. Genome Biol 2006, 7 Suppl 1:S11.1-8. [CrossRef]

- Stanke M, Morgenstern B: AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33:W465-7. [CrossRef]

- Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M: KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35:W182-5. [CrossRef]

- Mesbah NM: Industrial Biotechnology Based on Enzymes From Extreme Environments. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10:870083. [CrossRef]

- Polaina J, MacCabe AP: Dordrecht: Springer; 2007.

- Bowie JU, Lüthy R, Eisenberg D: A method to identify protein sequences that fold into a known three-dimensional structure. Science 1991, 253:164-170.

- Lüthy R, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D: Assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Nature 1992, 356:83-85.

- Collins T, Feller G: Psychrophilic enzymes: strategies for cold-adaptation. Essays Biochem 2023, 67:701-713. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Jia K, Chen H, Wang Z, Zhao W, Zhu L: Cold-adapted enzymes: mechanisms, engineering and biotechnological application. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2023, 46:1399-1410. [CrossRef]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE: UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 2004, 25:1605-1612. [CrossRef]

- Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Morris JH, Ferrin TE: UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci 2018, 27:14-25. [CrossRef]

- Vander Meersche Y, Cretin G, de Brevern AG, Gelly JC, Galochkina T: MEDUSA: Prediction of Protein Flexibility from Sequence. J Mol Biol 2021, 433:166882. [CrossRef]

- McKinney W: Data structures for statistical computing in Python. 2010, SciPy 445:51-56.

- Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, Haberland M, Reddy T, Cournapeau D, Burovski E, Peterson P, Weckesser W, Bright J, van der Walt SJ, Brett M, Wilson J, Millman KJ, Mayorov N, Nelson ARJ, Jones E, Kern R, Larson E, Carey CJ, Polat İ, Feng Y, Moore EW, VanderPlas J, Laxalde D, Perktold J, Cimrman R, Henriksen I, Quintero EA, Harris CR, Archibald AM, Ribeiro AH, Pedregosa F, van Mulbregt P, SciPy C: SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020, 17:261-272. [CrossRef]

- Hunter JD: Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Computing in science & engineering 2007, 9:90-95.

- Michel V, Gramfort A, Varoquaux G, Eger E, Keribin C, Thirion B: A supervised clustering approach for fMRI-based inference of brain states. Pattern Recognition 2012, 45:2041-2049. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Fernández L, Orellana LH, Johnston ER, Konstantinidis KT, Orlando J: Diversity of microbial communities and genes involved in nitrous oxide emissions in Antarctic soils impacted by marine animals as revealed by metagenomics and 100 metagenome-assembled genomes. Sci Total Environ 2021, 788:147693. [CrossRef]

- Pushkareva E, Elster J, Becker B: Metagenomic Analysis of Antarctic Biocrusts Unveils a Rich Range of Cold-Shock Proteins. Microorganisms 2023, 11:1932. [CrossRef]

- Oh HN, Park D, Seong HJ, Kim D, Sul WJ: Antarctic tundra soil metagenome as useful natural resources of cold-active lignocelluolytic enzymes. J Microbiol 2019, 57:865-873. [CrossRef]

- Varliero G, Lebre PH, Adams B, Chown SL, Convey P, Dennis PG, Fan D, Ferrari B, Frey B, Hogg ID, Hopkins DW, Kong W, Makhalanyane T, Matcher G, Newsham KK, Stevens MI, Weigh KV, Cowan DA: Biogeographic survey of soil bacterial communities across Antarctica. Microbiome 2024, 12:9. [CrossRef]

- Becker B, Pushkareva E: Metagenomics Provides a Deeper Assessment of the Diversity of Bacterial Communities in Polar Soils Than Metabarcoding. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14:812. [CrossRef]

- Štefanac T, Grgas D, Landeka Dragičević T: Xenobiotics-Division and Methods of Detection: A Review. J Xenobiot 2021, 11:130-141. [CrossRef]

- Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012.

- Bhardwaj L, Chauhan A, Ranjan A, Jindal T: Persistent Organic Pollutants in Biotic and Abiotic Components of Antarctic Pristine Environment. Earth Systems and Environment 2018, 2:35-54. [CrossRef]

- Kallenborn R, Reiersen L-O, Olseng CD: Long-term atmospheric monitoring of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the Arctic: a versatile tool for regulators and environmental science studies. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2012, 3:485-493.

- Anzano J, Abás E, Marina-Montes C, del Valle J, Galán-Madruga D, Laguna M, Cabredo S, Pérez-Arribas L-V, Cáceres J, Anwar J: A Review of Atmospheric Aerosols in Antarctica: From Characterization to Data Processing. Atmosphere 2022, 13:1621. [CrossRef]

- Berlemont R, Pipers D, Delsaute M, Angiono F, Feller G, Galleni M, Power P: Exploring the Antarctic soil metagenome as a source of novel cold-adapted enzymes and genetic mobile elements. Rev Argent Microbiol 2011, 43:94-103.

- Staerck C, Gastebois A, Vandeputte P, Calenda A, Larcher G, Gillmann L, Papon N, Bouchara JP, Fleury MJJ: Microbial antioxidant defense enzymes. Microb Pathog 2017, 110:56-65. [CrossRef]

- Baker A, Lin CC, Lett C, Karpinska B, Wright MH, Foyer CH: Catalase: A critical node in the regulation of cell fate. Free Radic Biol Med 2023, 199:56-66. [CrossRef]

- Koleva Z, Abrashev R, Angelova M, Stoyancheva G, Spassova B, Yovchevska L, Dishliyska V, Miteva-Staleva J, Krumova E: A Novel Extracellular Catalase Produced by the Antarctic Filamentous Fungus Penicillium rubens III11-2. Fermentation 2024, 10:58. [CrossRef]

- Krumova E, Abrashev R, Dishliyska V, Stoyancheva G, Kostadinova N, Miteva-Staleva J, Spasova B, Angelova M: Cold-active catalase from the psychrotolerant fungus Penicillium griseofulvum. J Basic Microbiol 2021, 61:782-794. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal J, Mehandia S, Singh G, Raina A, Arya SK: Catalase enzyme: Application in bioremediation and food industry. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2018, 16:192-199. [CrossRef]

- Iordachescu M, Imai R: Trehalose biosynthesis in response to abiotic stresses. J Integr Plant Biol 2008, 50:1223-1229. [CrossRef]

- Cai X, Seitl I, Mu W, Zhang T, Stressler T, Fischer L, Jiang B: Biotechnical production of trehalose through the trehalose synthase pathway: current status and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102:2965-2976. [CrossRef]

- Ban X, Dhoble AS, Li C, Gu Z, Hong Y, Cheng L, Holler TP, Kaustubh B, Li Z: Bacterial 1,4-α-glucan branching enzymes: characteristics, preparation and commercial applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2020, 40:380-396. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).