Submitted:

22 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Soil Physico-Chemical Parameters

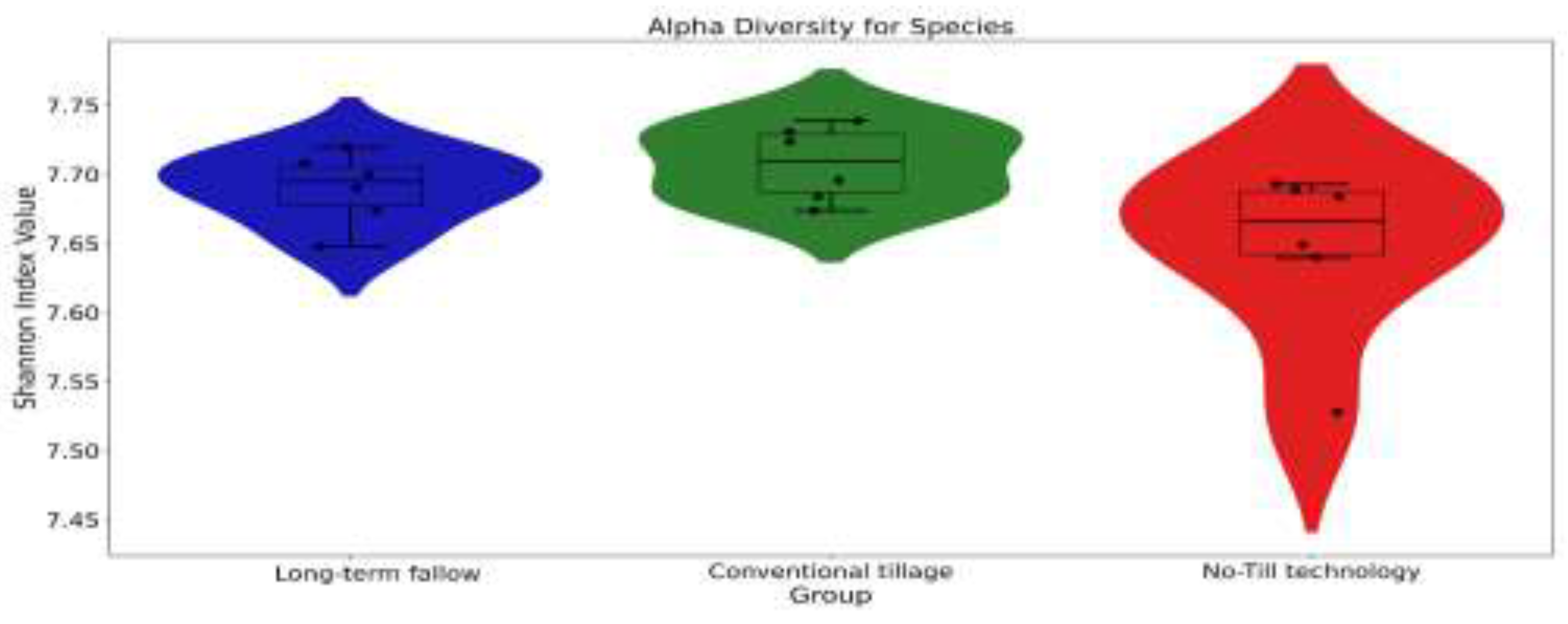

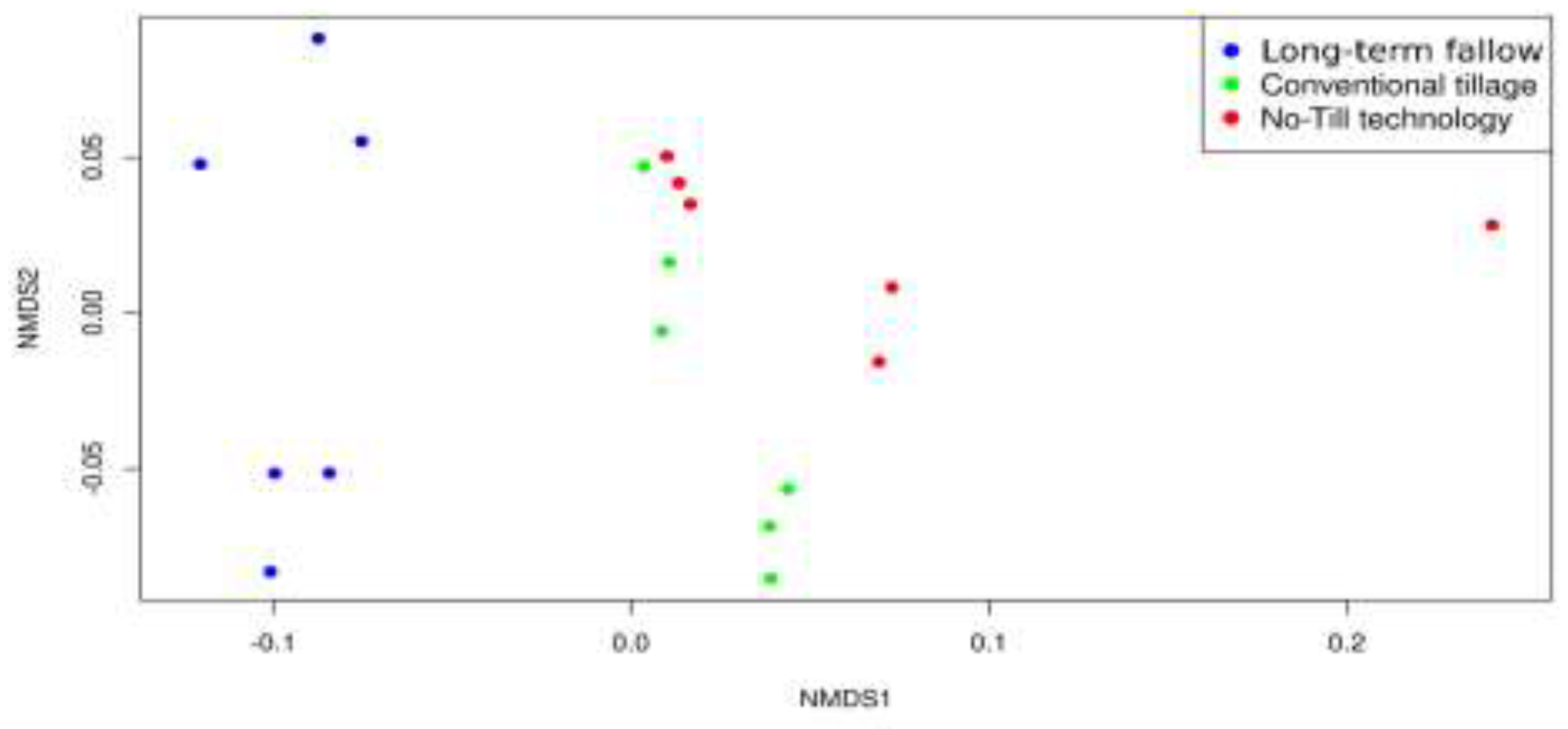

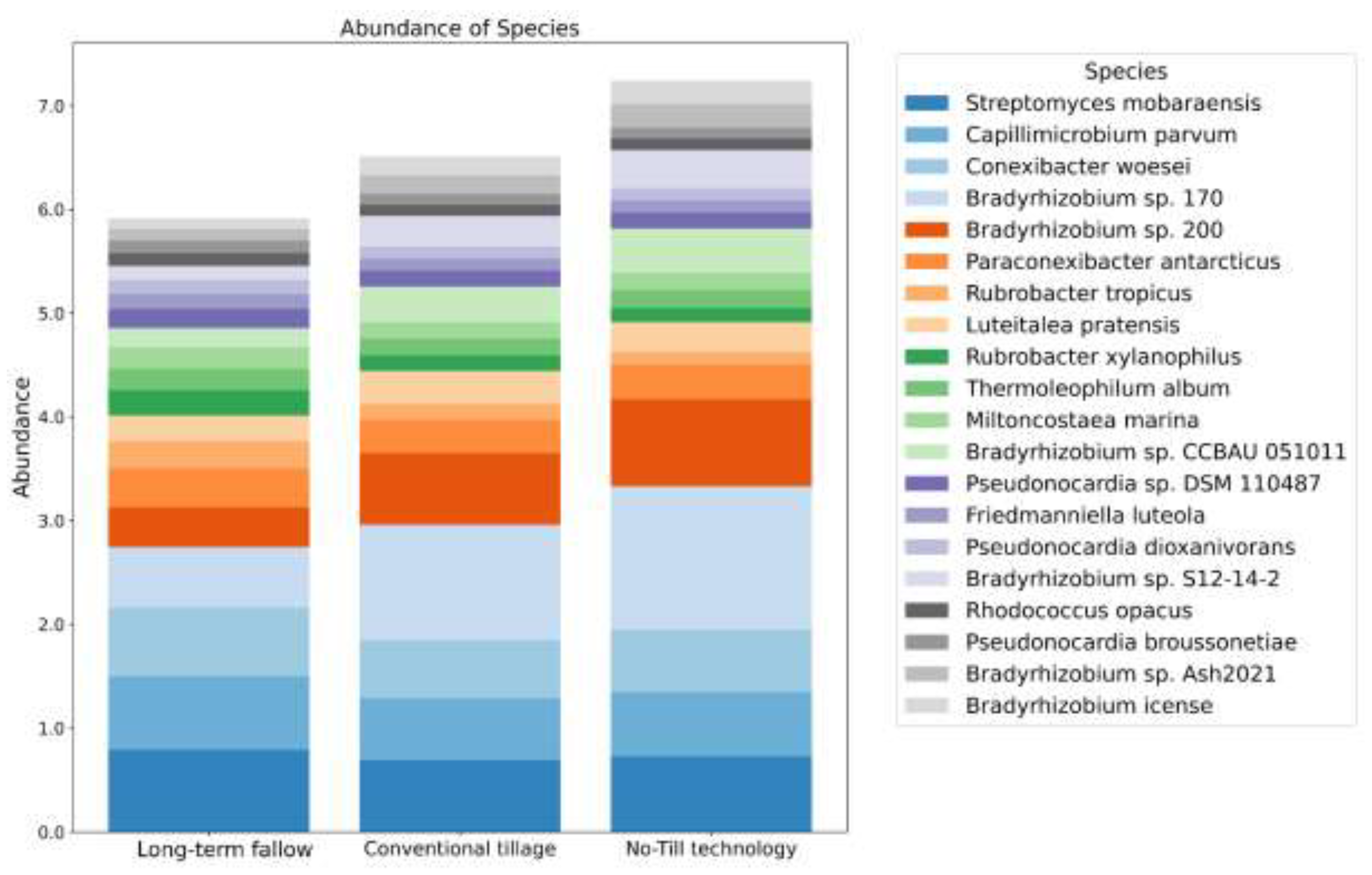

3.2.2. Taxonomy Analysis

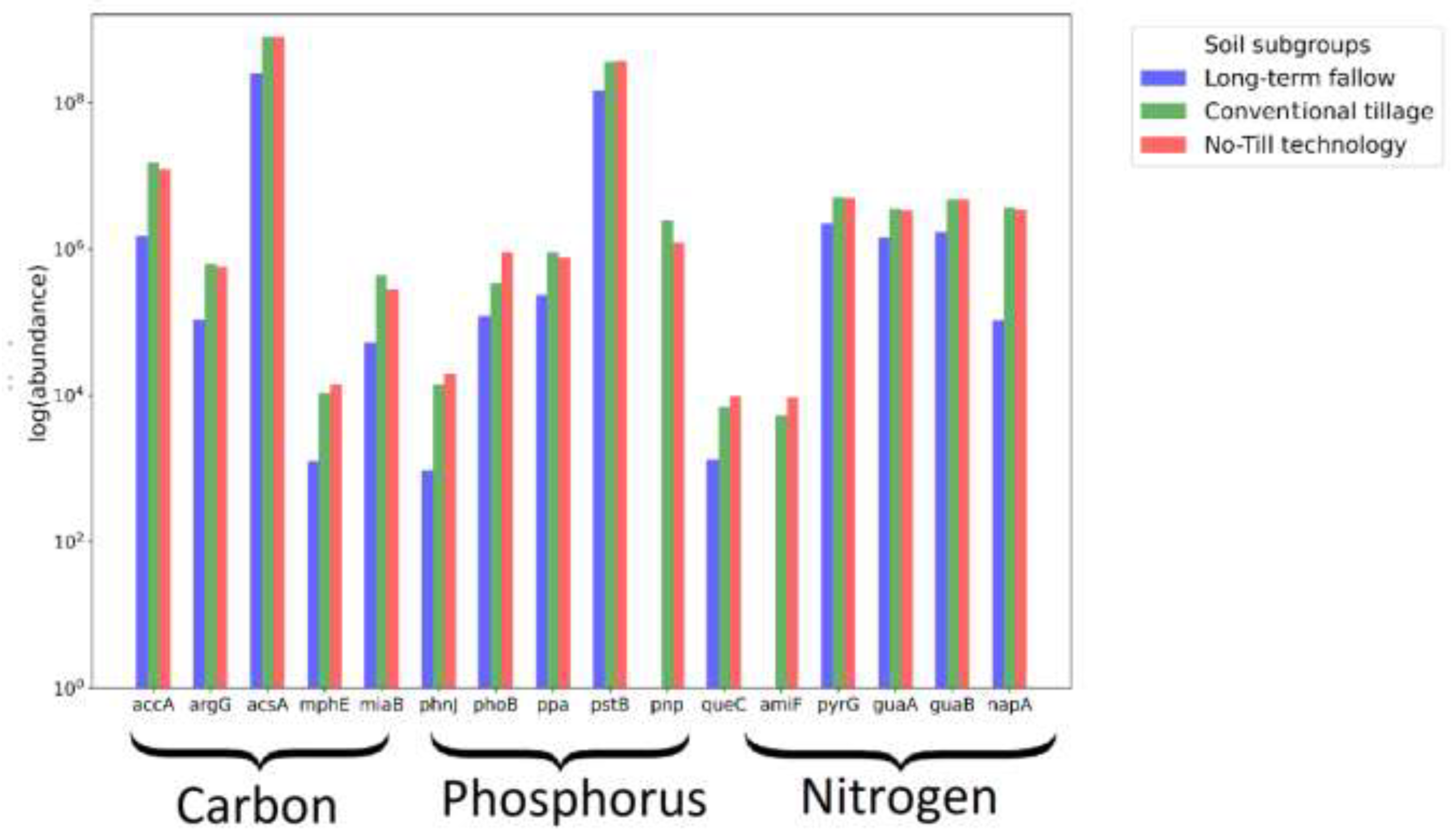

3.3. Analysis of Genes

3.3. Signature Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

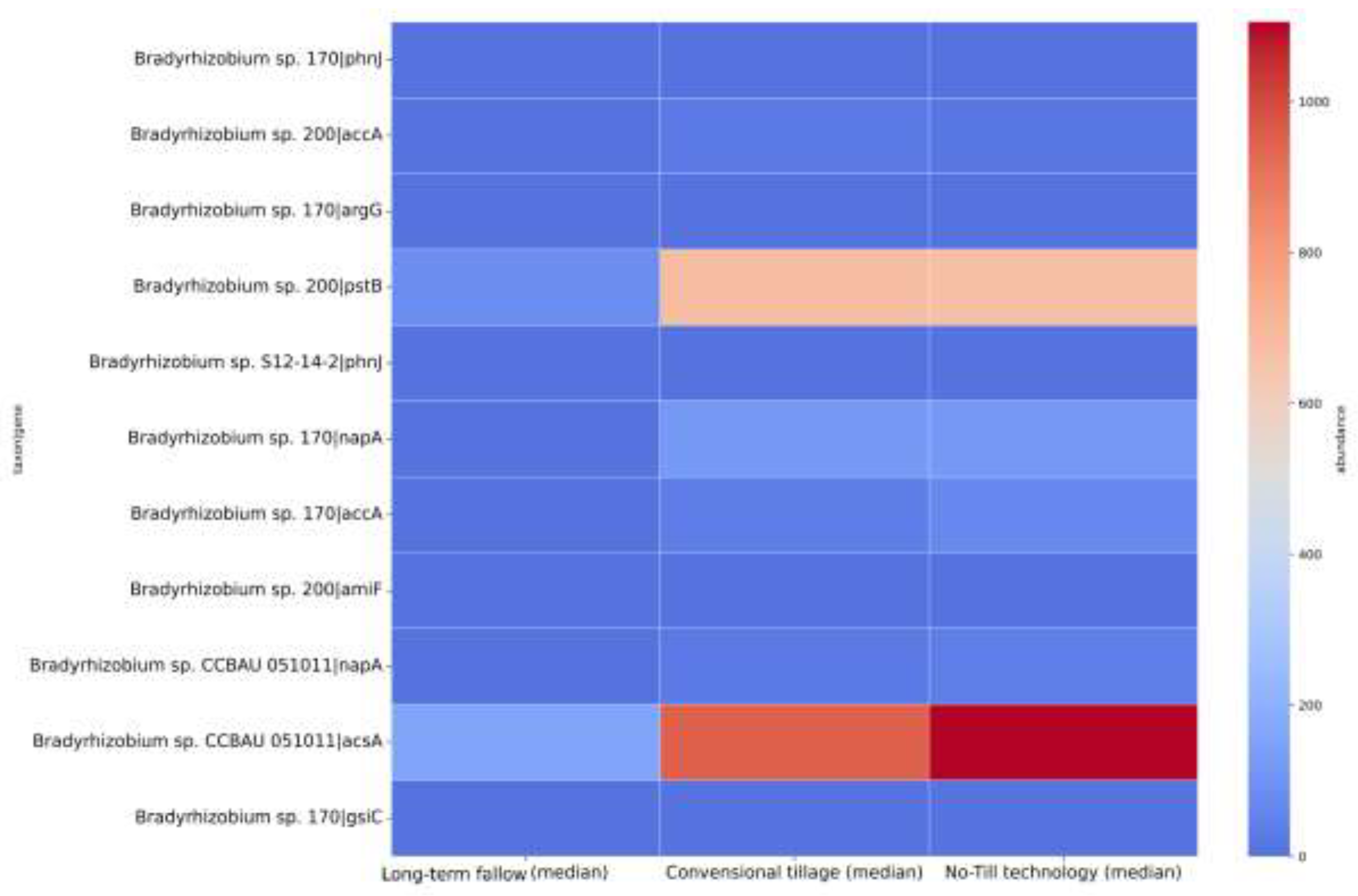

| Gene | Long-term fallow | Conventional tillage (median) | No-Till technology (median) |

|---|---|---|---|

| accA | 1.53·106 | 15.15·106 | 12.48·106 |

| acsA | 2.55·108 | 8.09·108 | 8.08·108 |

| amiF | 0 | 5.38·103 | 9.43·103 |

| argG | 108.81·103 | 624.34·103 | 578.59·103 |

| guaA | 1.44·106 | 3.54·106 | 3.41·106 |

| guaB | 1.73·106 | 4.79·106 | 4.72·106 |

| miaB | 53.03·103 | 441.45·103 | 281.52·103 |

| mphE | 1.27·103 | 10.87·103 | 14.29·103 |

| napA | 106.36·103 | 3.67·106 | 3.42·106 |

| phnJ | 0.94·103 | 14.27·103 | 20.07·103 |

| phoB | 121.40·103 | 343.04·103 | 913.79·103 |

| pnp | 0 | 2.46·106 | 1.22·106 |

| ppa | 236.70·103 | 910.72·103 | 772.52·103 |

| pstB | 1.49·108 | 3.68·108 | 3.72·108 |

| pyrG | 2.22·106 | 5.18·106 | 4.96·106 |

| queC | 1.32·103 | 6.84·103 | 9.72·103 |

References

- Wilhelm, R.C.; Amsili, J.P.; Kurtz, K.S.M.; van Es, H.M.; Buckley, D.H. Ecological Insights into Soil Health According to the Genomic Traits and Environment-Wide Associations of Bacteria in Agricultural Soils. ISME Communications 2023, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, J.D.D.; Florez, J.E.M.; Alvarez, D.L. Metagenomics Approaches to Understanding Soil Health in Environmental Research - a Review. Soil Sci. Ann. 2023, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Feng, G.; Paul, V.; Adeli, A.; Brooks, J. Soil Health Assessment Methods: Progress, Applications and Comparison. In Advances in Agronomy; Academic Press, 2022; Vol. 172, pp. 129–210. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, J.I. Dispersing Misconceptions and Identifying Opportunities for the Use of “omics” in Soil Microbial Ecology. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R.A.; Bottos, E.M.; Roy Chowdhury, T.; Zucker, J.D.; Brislawn, C.J.; Nicora, C.D.; Fansler, S.J.; Glaesemann, K.R.; Glass, K.; Jansson, J.K. Moleculo Long-Read Sequencing Facilitates Assembly and Genomic Binning from Complex Soil Metagenomes. mSystems 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Peng, B.; Yang, L.; Gao, J.; Xiao, C. Structure and Function of Microbiomes in the Rhizosphere and Endosphere Response to Temperature and Precipitation Variation in Inner Mongolia Steppes. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnke, G.D.; Kim, N.; Zabaloy, M.C.; Riggins, C.W.; Rodriguez-Zas, S.; Villamil, M.B. Soil Microbial Indicators within Rotations and Tillage Systems. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Zabaloy, M.C.; Riggins, C.W.; Rodríguez-Zas, S.; Villamil, M.B. Microbial Shifts Following Five Years of Cover Cropping and Tillage Practices in Fertile Agroecosystems. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, A.; Owens, P.; Lang, V.; Jiang, Z.; Micheli, E.; Krasilnikov, P. “Black Soils” in the Russian Soil Classification System, the US Soil Taxonomy and the WRB: Quantitative Correlation and Implications for Pedodiversity Assessment. CATENA 2021, 196, 104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughenour, C.M. Innovating Conservation Agriculture: The Case of No-Till Cropping. 2009, 68, 178–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heanes, D.L. Determination of Total organic-C in Soils by an Improved Chromic Acid Digestion and Spectrophotometric Procedure. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.P.E.; Domsch, K.H. A Physiological Method for the Quantitative Measurement of Microbial Biomass in Soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 1978, 10, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milham, P.J.; Awad, A.S.; Paull, R.E.; Bull, J.H. Analysis of Plants, Soils and Waters for Nitrate by Using an Ion-Selective Electrode. Analyst 1970, 95, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaziev, F. Enzymatic Activity of Soils. Moscow: Nauka Publ. 1976, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Lei, R.; Ding, S.-W.; Zhu, S. Skewer: A Fast and Accurate Adapter Trimmer for next-Generation Sequencing Paired-End Reads. BMC Bioinformatics 2014, 15, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved Metagenomic Analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biology 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Rincon, N.; Wood, D.E.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Pockrandt, C.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L.; Steinegger, M. Metagenome Analysis Using the Kraken Software Suite. Nat Protoc 2022, 17, 2815–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, P. VEGAN, a Package of R Functions for Community Ecology. Journal of Vegetation Science 2003, 14, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutet, E.; Lieberherr, D.; Tognolli, M.; Schneider, M.; Bansal, P.; Bridge, A.J.; Poux, S.; Bougueleret, L.; Xenarios, I. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, the Manually Annotated Section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase: How to Use the Entry View. In Plant Bioinformatics: Methods and Protocols; Edwards, D., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4939-3167-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG as a Reference Resource for Gene and Protein Annotation. Nucleic Acids Research 2016, 44, D457–D462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and Sensitive Protein Alignment Using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiryushin, V.K.; Vlasenko, A.N.; Kalichkin, V.K. Adaptive Landscape Farming Systems of the Novosibirsk Region. Novosibirsk, Izdatel’stvo SO RASKhN = The Publishing House of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences 2002, 387. [Google Scholar]

- Danilova, A.A. Biodynamics of Arable Soil at Different Content of Organic Matter. Novosibirsk: SFNCA RAS 2018, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, A.L.; Bacq-Labreuil, A.; Zhang, X.; Clark, I.M.; Coleman, K.; Mooney, S.J.; Ritz, K.; Crawford, J.W. Soil as an Extended Composite Phenotype of the Microbial Metagenome. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kemmitt, S.; White, R.P.; Xu, J.; Brookes, P.C. Carbon Dynamics in a 60 Year Fallowed Loamy-Sand Soil Compared to That in a 60 Year Permanent Arable or Permanent Grassland UK Soil. Plant Soil 2012, 352, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, W.; Zheng, J.; Luo, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, H.; Qi, H. Effect of Long-Term Tillage on Soil Aggregates and Aggregate-Associated Carbon in Black Soil of Northeast China. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0199523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Qi, S.; Gao, W.; Luo, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Wang, M.; et al. Eight-Year Tillage in Black Soil, Effects on Soil Aggregates, and Carbon and Nitrogen Stock. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Shen, T.-J. Nonparametric Estimation of Shannon’s Index of Diversity When There Are Unseen Species in Sample. Environmental and Ecological Statistics 2003, 10, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chendev, Y.G.; Sauer, T.J.; Ramirez, G.H.; Burras, C.L. History of East European Chernozem Soil Degradation; Protection and Restoration by Tree Windbreaks in the Russian Steppe. Sustainability 2015, 7, 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergaki, C.; Lagunas, B.; Lidbury, I.; Gifford, M.L.; Schäfer, P. Challenges and Approaches in Microbiome Research: From Fundamental to Applied. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J.; Clarke, L. The Effect of No-till Farming on the Soil Functions of Water Purification and Retention in North-Western Europe: A Literature Review. Soil and Tillage Research 2019, 189, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrune, F.; Theodorakopoulos, N.; Colinet, G.; Hiel, M.-P.; Bodson, B.; Taminiau, B.; Daube, G.; Vandenbol, M.; Hartmann, M. Temporal Dynamics of Soil Microbial Communities below the Seedbed under Two Contrasting Tillage Regimes. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Soil Macroaggregate Turnover and Microaggregate Formation: A Mechanism for C Sequestration under No-Tillage Agriculture. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2000, 32, 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, G.A.; Richard, D.B.; Nico, M. van S. The Unseen Majority: Soil Microbes as Drivers of Plant Diversity and Productivity in Terrestrial Ecosystems.

- Monciardini, P.; Cavaletti, L.; Schumann, P.; Rohde, M.; Donadio, S. Conexibacter Woesei Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Novel Representative of a Deep Evolutionary Line of Descent within the Class Actinobacteria. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2003, 53, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.; Huber, K.J.; Geppert, A.; Wolf, J.; Neumann-Schaal, M.; Luckner, M.; Wanner, G.; Müsken, M.; Overmann, J. Capillimicrobium Parvum Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Novel Representative of Capillimicrobiaceae Fam. Nov. within the Order Solirubrobacterales, Isolated from a Grassland Soil. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2022, 72, 005508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, S.; Morikawa, T.; Wasai, S.; Kasahara, Y.; Koshiba, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Fujiwara, T.; Tokunaga, T.; Minamisawa, K. Identification of Nitrogen-Fixing Bradyrhizobium Associated With Roots of Field-Grown Sorghum by Metagenome and Proteome Analyses. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agashe, R.; George, J.; Pathak, A.; Fasakin, O.; Seaman, J.; Chauhan, A. Shotgun Metagenomics Analysis Indicates Bradyrhizobium Spp. as the Predominant Genera for Heavy Metal Resistance and Bioremediation in a Long-Term Heavy Metal-Contaminated Ecosystem. Microbiology Resource Announcements 2024, 13, e00245–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, Z.; Lamrabet, M.; Bennis, M.; Kaddouri, K.; Alami, S.; Bouhnik, O.; El Idrissi, M.M. Nitrogen-Fixing Bradyrhizobium Spp. as Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria to Improve Soil Quality and Plant Tolerance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. In Soil Bacteria: Biofertilization and Soil Health; Dheeman, S., Islam, M.T., Egamberdieva, D., Siddiqui, Md.N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; ISBN 978-981-9734-73-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, F.P.; Clark, I.M.; King, R.; Shaw, L.J.; Woodward, M.J.; Hirsch, P.R. Novel European Free-Living, Non-Diazotrophic Bradyrhizobium Isolates from Contrasting Soils That Lack Nodulation and Nitrogen Fixation Genes – a Genome Comparison. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 25858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, L.; Zeng, K.; Wei, Y.; Li, H.; Ji, X. Microbial-Driven Carbon Fixation in Natural Wetland. Journal of Basic Microbiology 2023, 63, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, H.; Xie, X.; Chen, Y.; Lang, M.; Chen, X. Long-Term Moderate Fertilization Increases the Complexity of Soil Microbial Community and Promotes Regulation of Phosphorus Cycling Genes to Improve the Availability of Phosphorus in Acid Soil. Applied Soil Ecology 2024, 194, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocabruna, P.; Domene, X.; Preece, C.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; Maspons, J.; Penuelas, J. Effect of Climate, Crop, and Management on Soil Phosphatase Activity in Croplands: A Global Investigation and Relationships with Crop Yield. European Journal of Agronomy 2024, 161, 127358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.E.; Barea, J.-M.; McNeill, A.M.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Acquisition of Phosphorus and Nitrogen in the Rhizosphere and Plant Growth Promotion by Microorganisms. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 305–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Rensing, C.; Han, D.; Xiao, K.-Q.; Dai, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liesack, W.; Peng, J.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, F. Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Reveals Distinct Phosphorus Acquisition Strategies between Soil Microbiomes. mSystems 2022, 7, e01107–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Xiao, Z.; Ming, A.; Teng, J.; Zhu, H.; Qin, J.; Liang, Z. Soil Phosphorus Cycling Microbial Functional Genes of Monoculture and Mixed Plantations of Native Tree Species in Subtropical China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanuwidjaja, I.; Vogel, C.; Pronk, G.J.; Schöler, A.; Kublik, S.; Vestergaard, G.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Mrkonjic Fuka, M.; Schloter, M.; Schulz, S. Microbial Key Players Involved in P Turnover Differ in Artificial Soil Mixtures Depending on Clay Mineral Composition. Microb Ecol 2021, 81, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.-L.; Liu, J.; Jia, P.; Yang, T.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liao, B.; Shu, W.; Li, J. Novel Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria Enhance Soil Phosphorus Cycling Following Ecological Restoration of Land Degraded by Mining. The ISME Journal 2020, 14, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, C.; Elrys, A.; Shen, F.; Cheng, Y.; Chang, S. Organic Amendment Enhanced Microbial Nitrate Immobilization with Negligible Denitrification Nitrogen Loss in an Upland Soil. Environmental Pollution 2021, 288, 117721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, F.; Gallardo, M.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Global Trends in Nitrate Leaching Research in the 1960–2017 Period. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 643, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Hu, G.; Hu, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ning, K. Comparative Genomics Analysis Reveals Genetic Characteristics and Nitrogen Fixation Profile of Bradyrhizobium. iScience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil indicator | Long-term fallow | Conventional tillage | No-Till technology |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOC % | 4.1 | 4.2 | |

| C in mortmass, mg/kg | 67 | 817 | 1133 |

| C in microbial biomass, μg/g | 30 | 100 | 120 |

| N-NO3, mg/kg | 78.6 | 19.8 | 4.4 |

| Phosphatase activity, μg, Р2О5/g per hour | 13.8 | 14.6 | 26.2 |

| Gene name | Enzyme name | KEGG enzyme entry | Metabolic pathway |

| accA | Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase carboxyl transferase subunit alpha | 2.1.3.15 | carbon |

| argG | Argininosuccinate synthase (Forming carbon-nitrogen bonds) | 6.3.4.5 | |

| acsA | Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase | 6.2.1.1 | |

| mphE | 4-hydroxy-2-oxovalerate aldolase | 4.1.3.39 | |

| miaB | tRNA-2-methylthio-N(6)-dimethylallyladenosine synthase (catalyzes methylation) | 2.8.4.3 | |

| phnJ | Alpha-D-ribose 1-methylphosphonate 5-phosphate C-P lyase | 4.7.1.1 | phosphorus |

| phoB | Phosphate regulon transcriptional regulatory protein | 3.6.1.11 | |

| ppa | Inorganic pyrophosphatase | 3.6.1.1 | |

| pstB | Phosphate import ATP-binding protein | 7.3.2.1 | |

| pnp | Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase (catalyzes the phosphorolysis) | 2.7.7.8 | |

| queC | 7-cyano-7-deazaguanine synthase (Forming carbon-nitrogen bonds) | 6.3.4.20 | nitrogen |

| amiF | Formamidase (Acting on carbon-nitrogen bonds) | 3.5.1.49 | |

| pyrG | CTP synthase (glutamine hydrolysing) (Forming carbon-nitrogen bonds) | 6.3.4.2 | |

| guaA | GMP synthase [glutamine-hydrolyzing] (Forming carbon-nitrogen bonds) | 6.3.5.2 | |

| guaB | Inosine-5'-monophosphate dehydrogenase (Acting on the CH-OH group of donors) | 1.1.1.205 | |

| napA | Periplasmic nitrate reductase | 1.9.6.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).