Submitted:

08 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fertilizers Manufacturing

2.2. Experimental Design

- 45 g of composted olive pomace (OP)

- 5 g of Sulfur Bentonite + Olive Pomace (SBOP)

- 5 g of Sulfur Bentonite (SB)

- 4.2 g of synthetic fertilizer (NPK).

- Unfertilized soil (CTR)

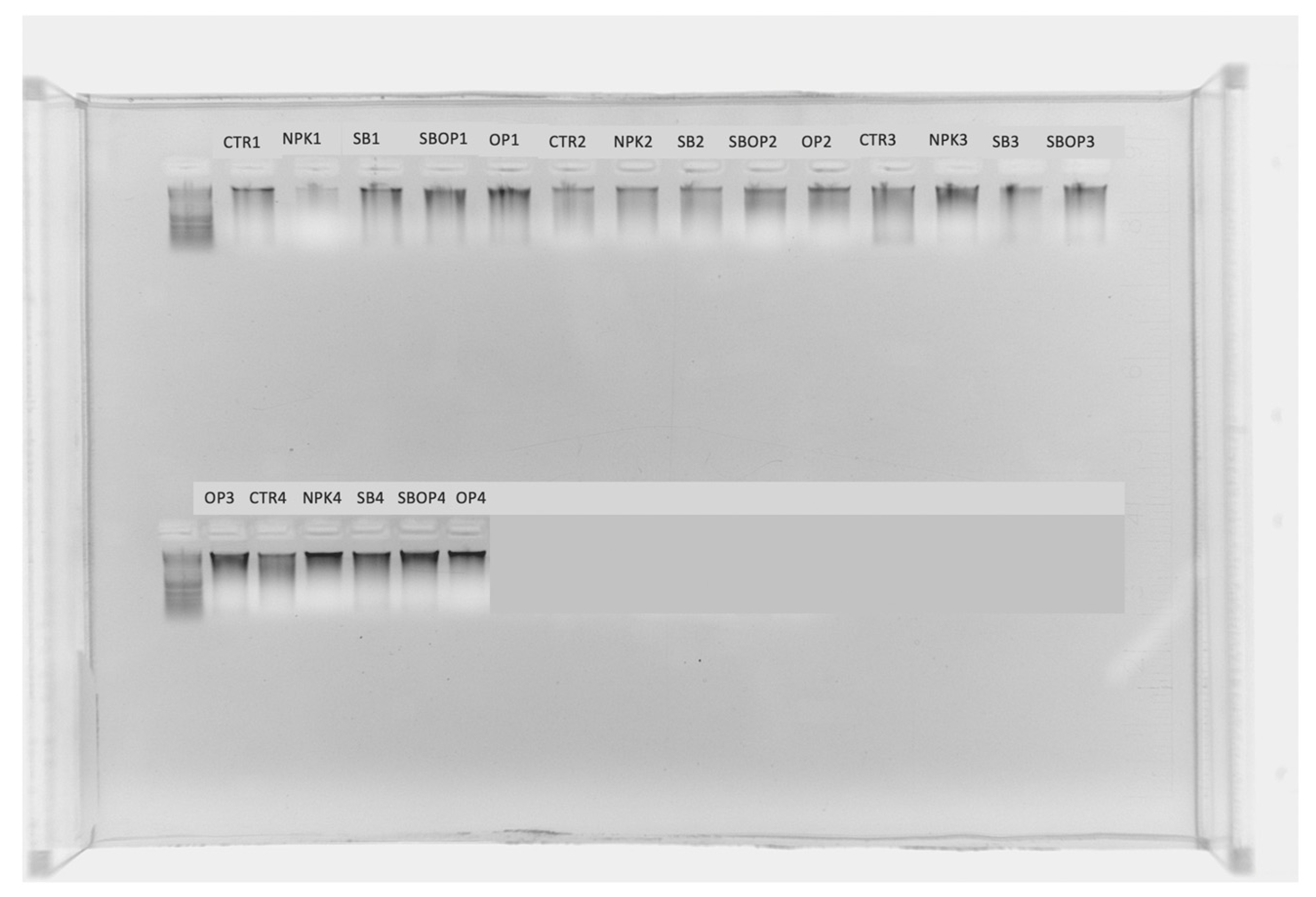

2.3. Samples Collection and DNA Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Biodiversity Assessment and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

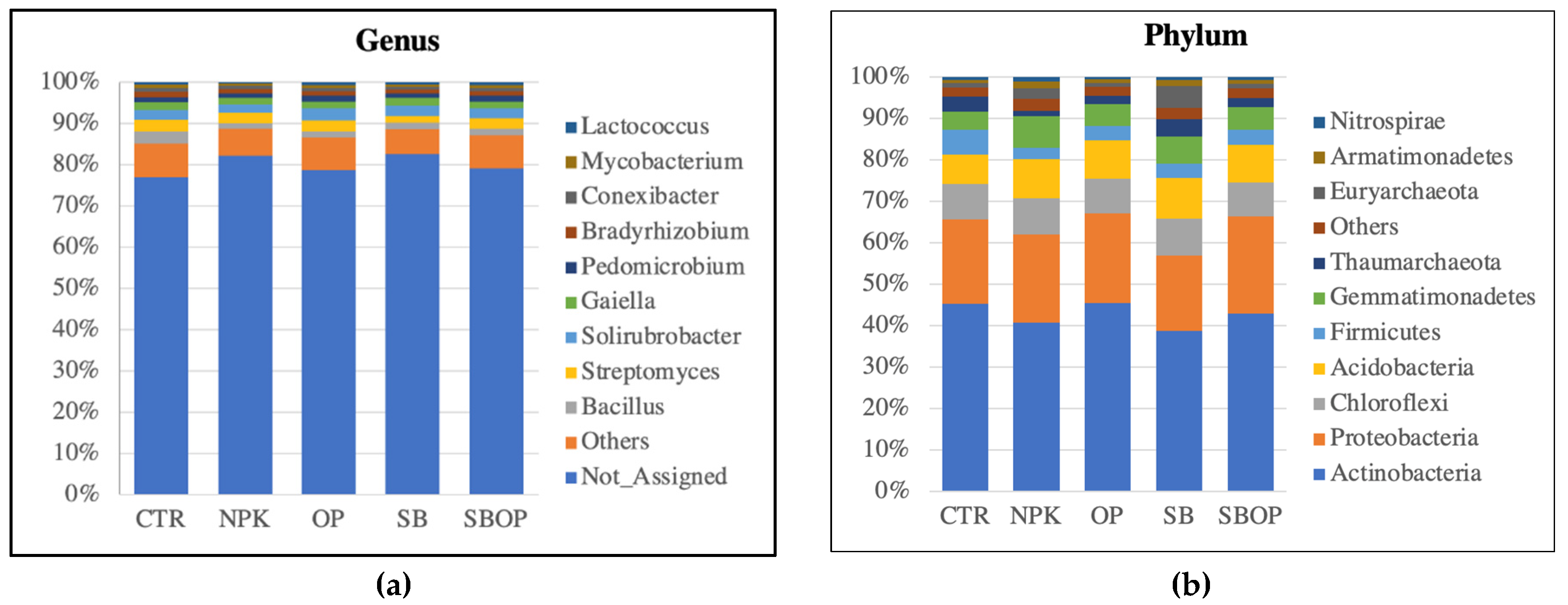

3.1 Bacteria Taxa Abundance

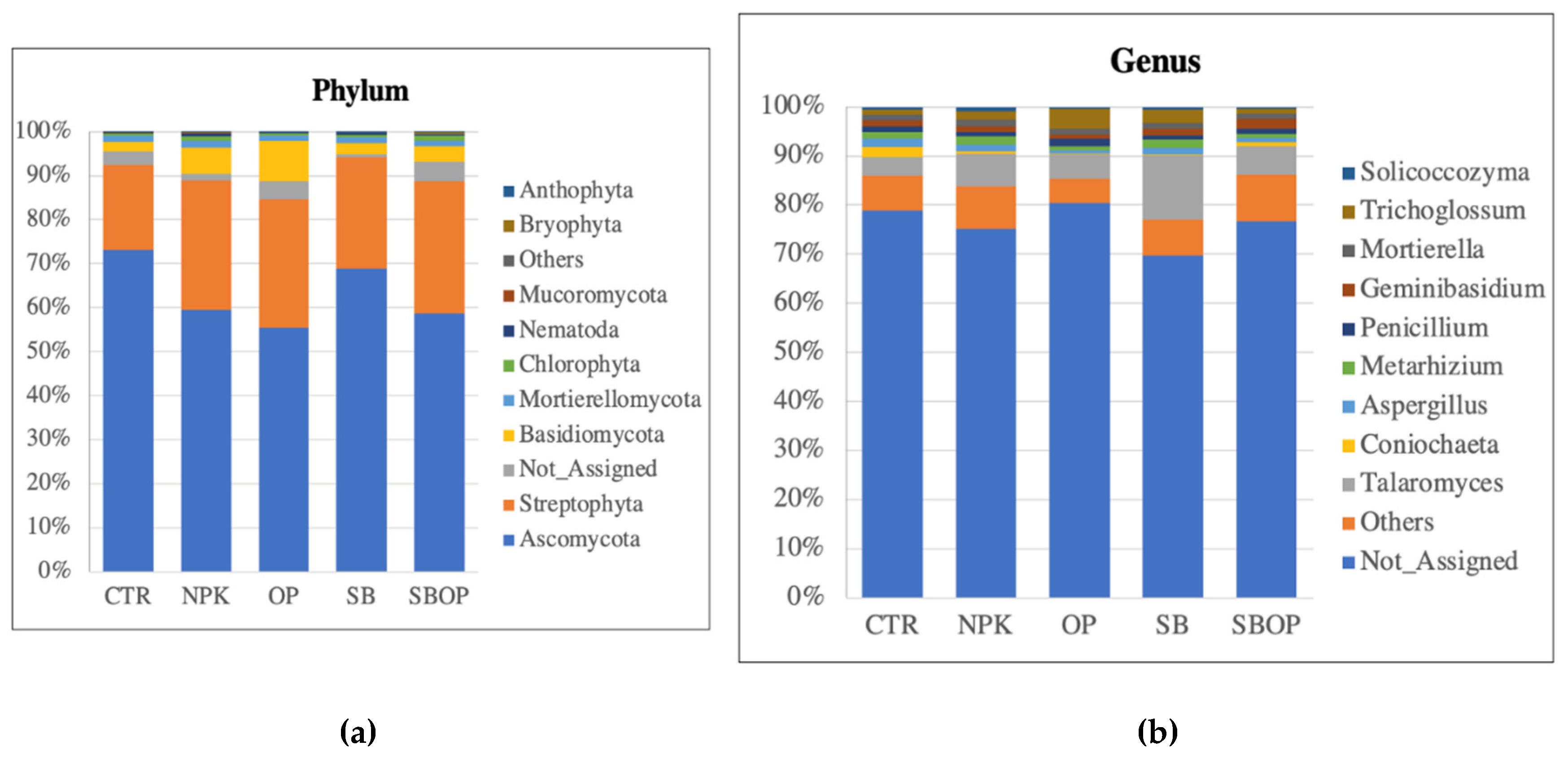

3.2. Fungi Taxa Abundance

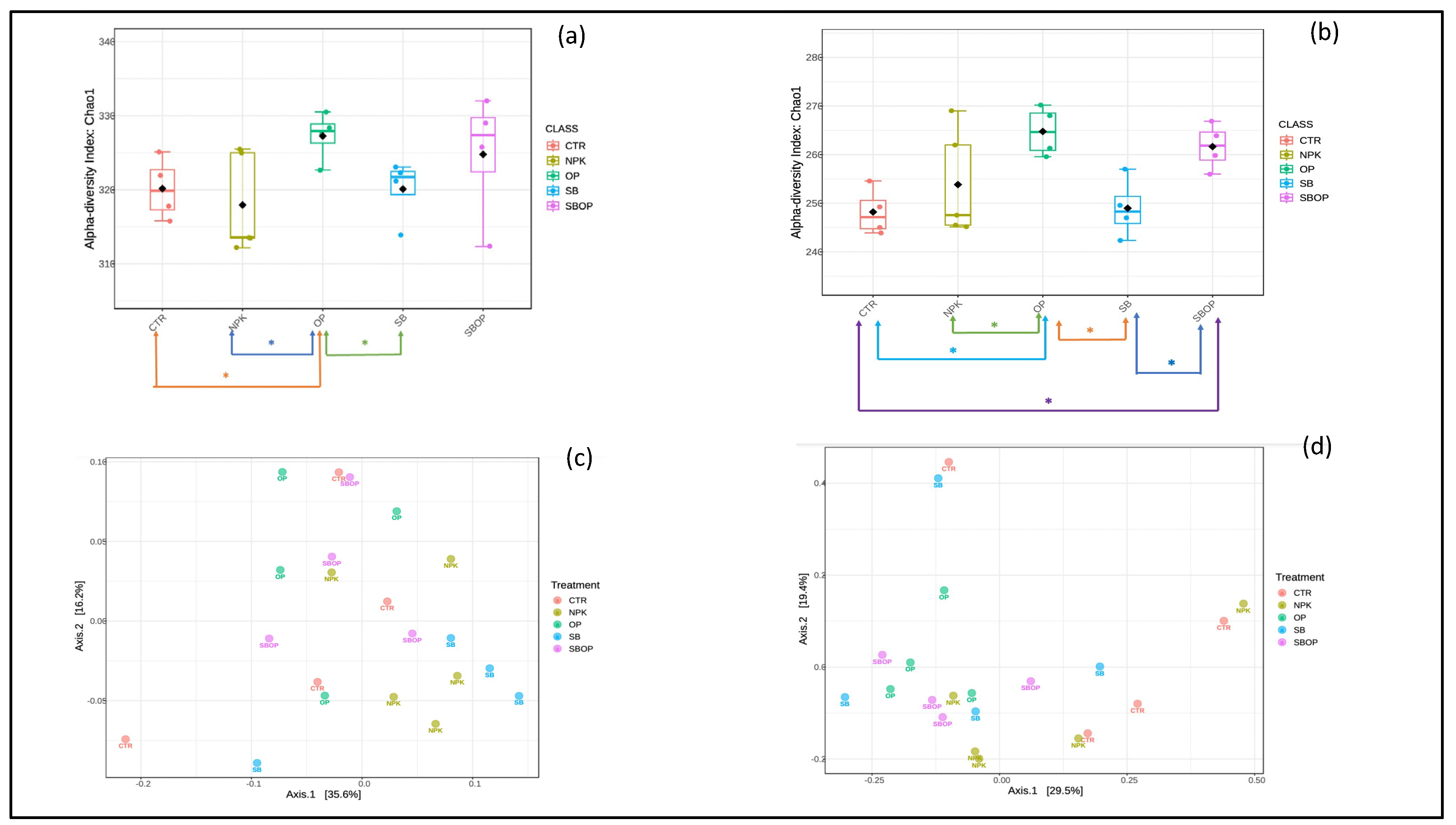

3.3. Bacteria Alpha and Beta Diversity

3.4 Fungi Alpha and Beta Diversity

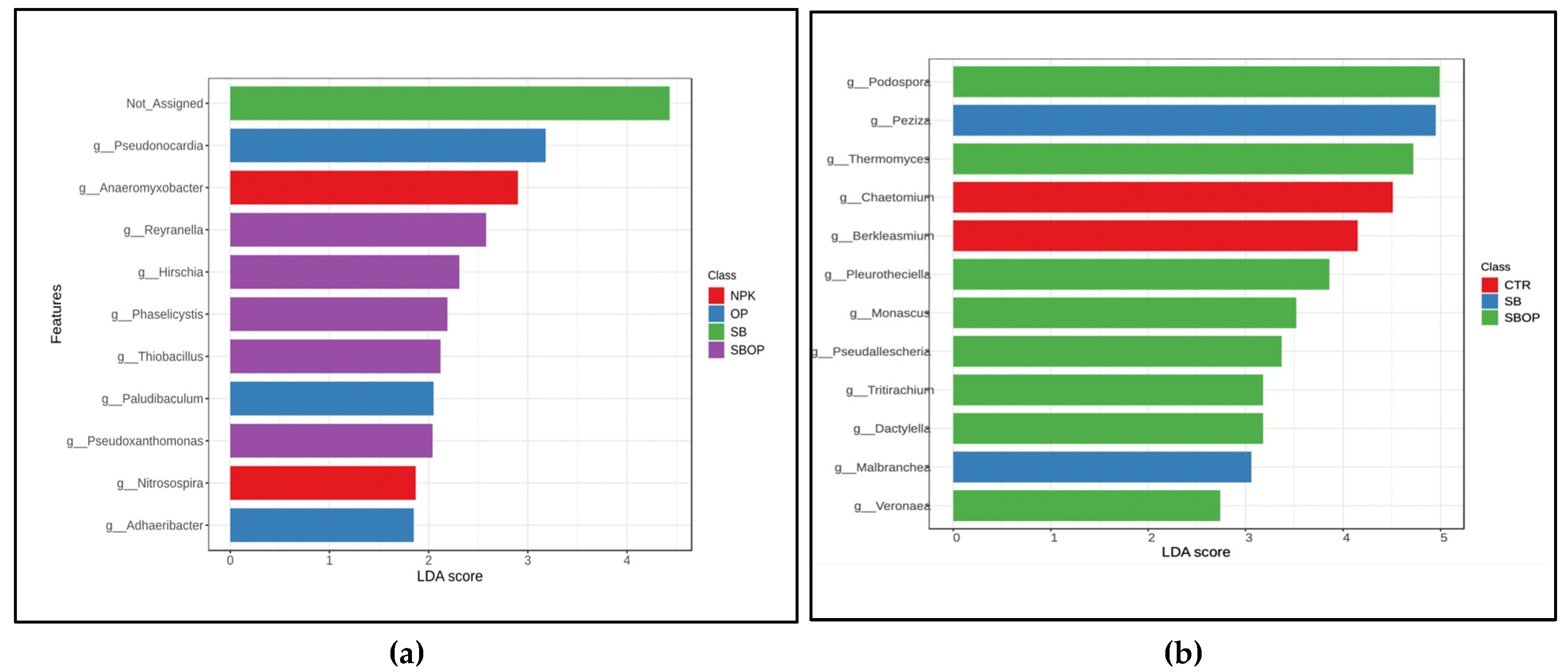

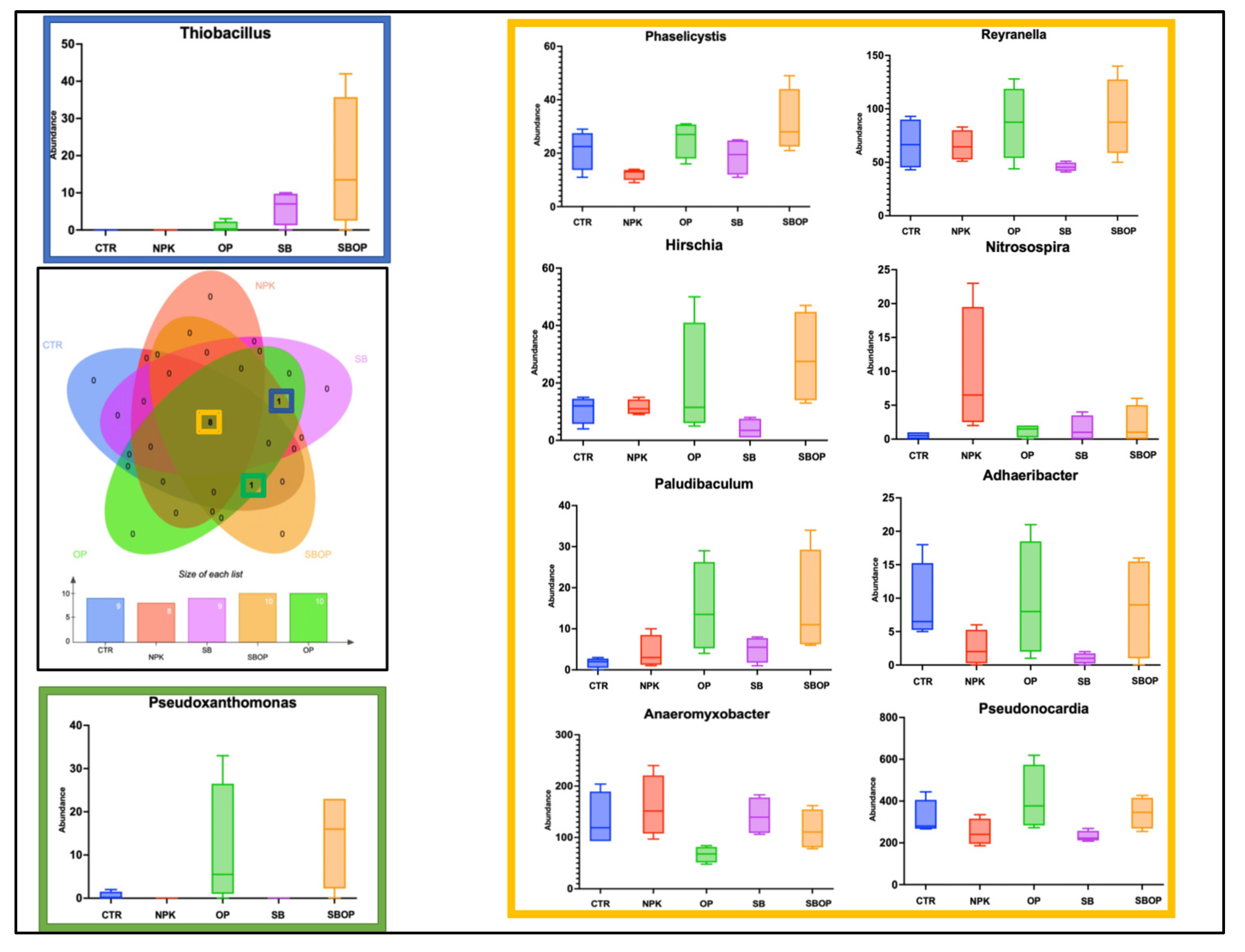

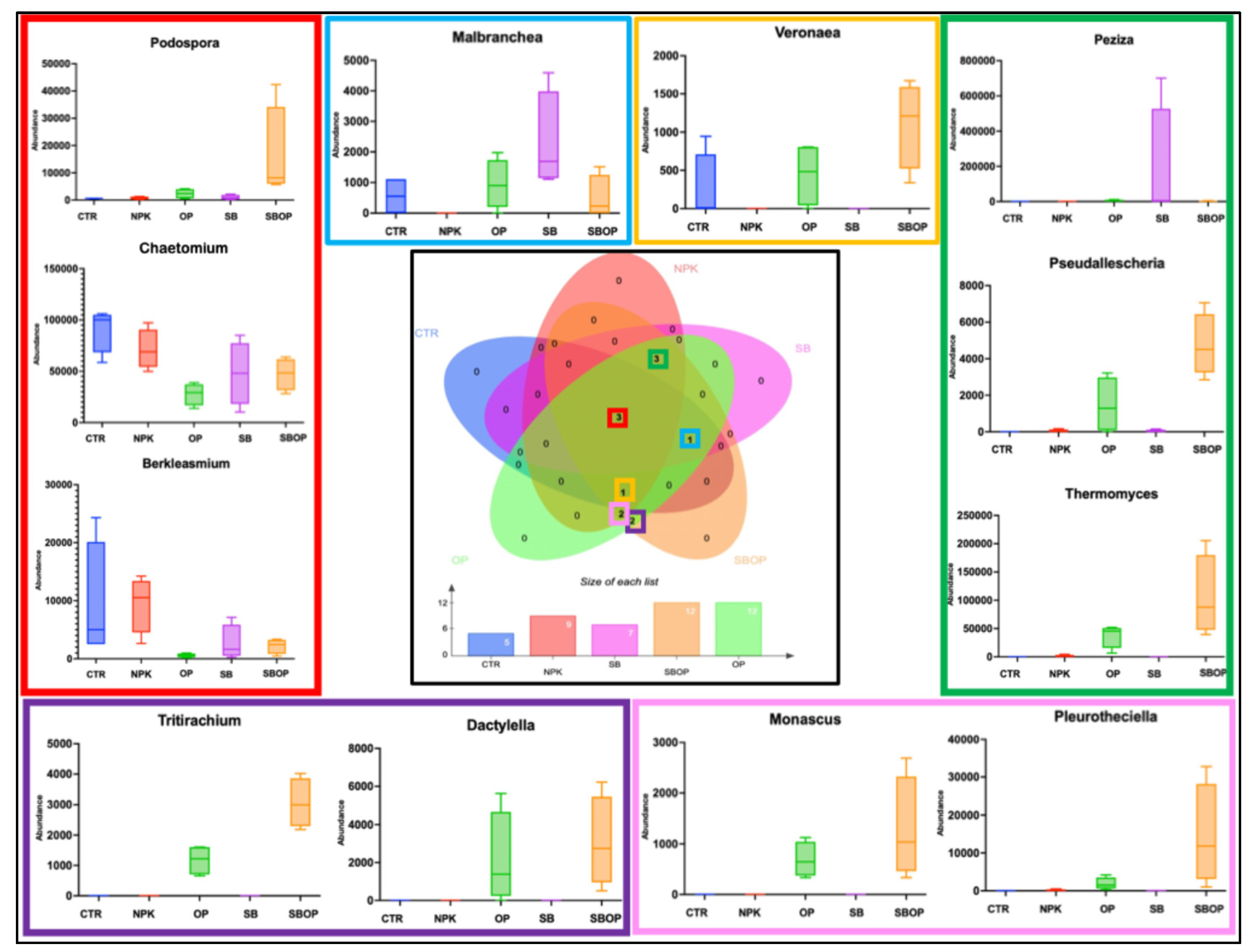

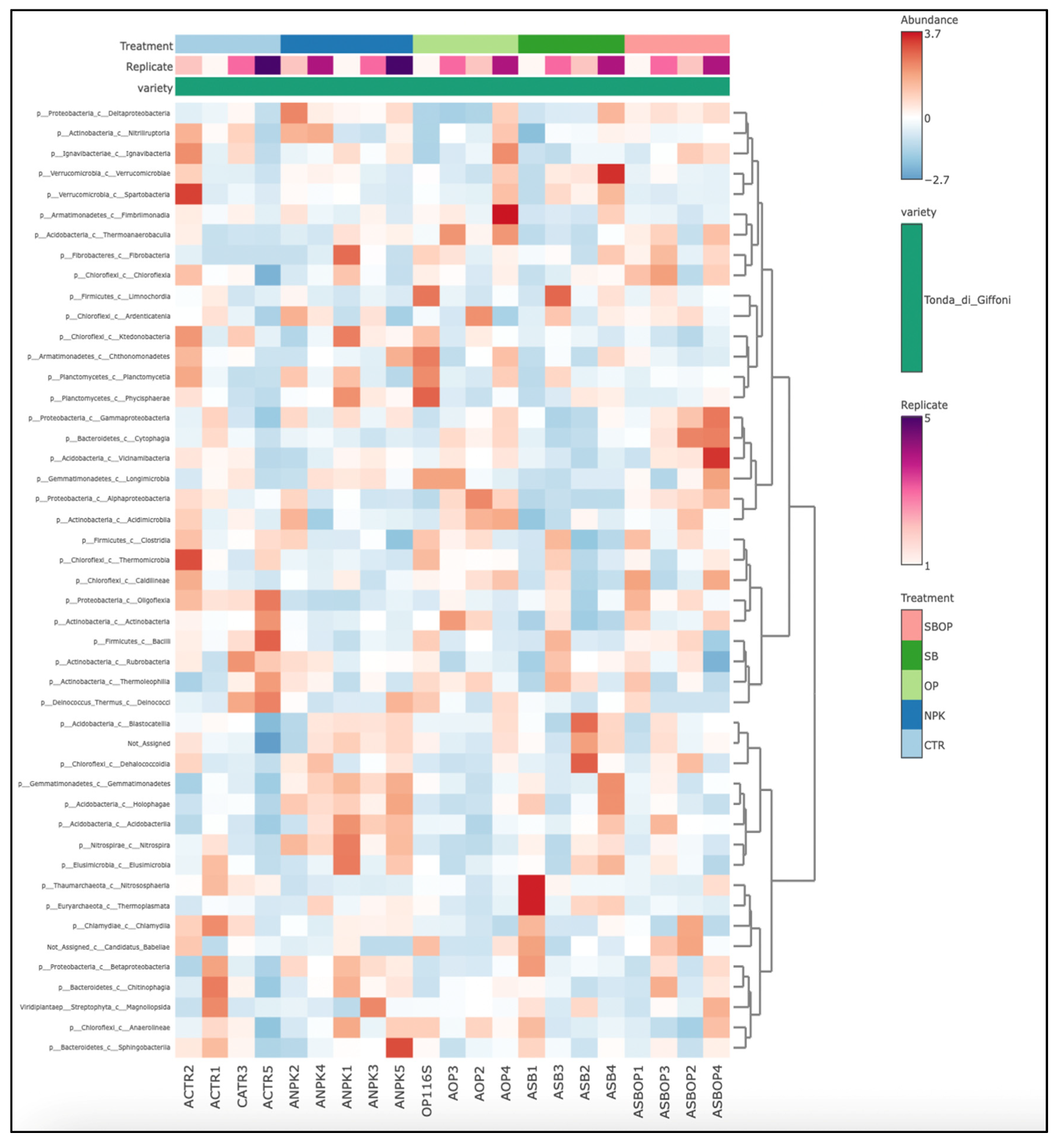

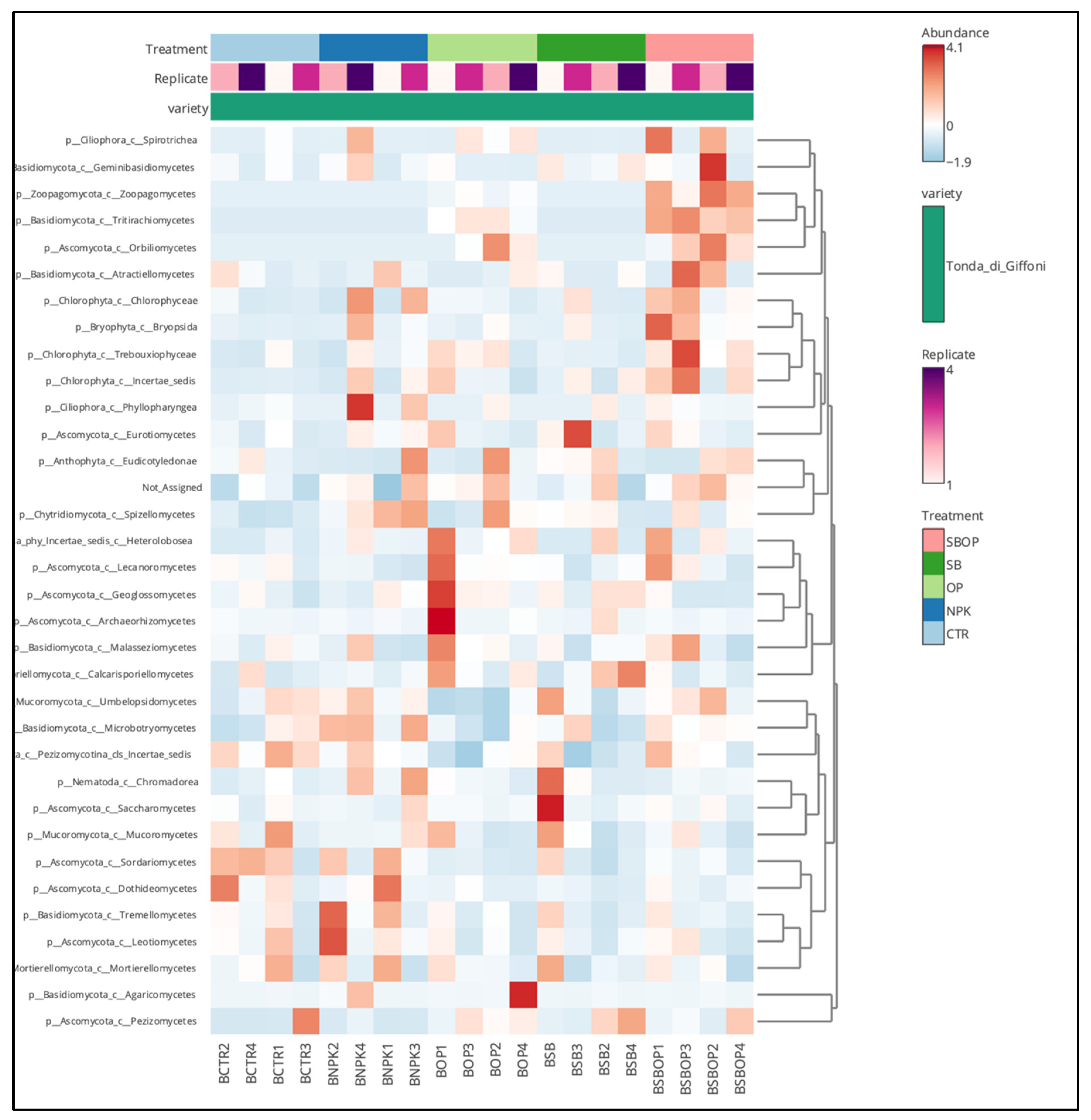

3.5. Comparison Analysis with LEfSe, Heatmap of Relative Abundance and Veen Diagram

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Fertilization on Microbial Composition and Biodiversity

4.2. Sulfur with Organic Matter Enhances Beneficial Microbial Component

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ciemniewska-Żytkiewicz, H.; Verardo, V.; Pasini, F.; Bryś, J.; Koczoń, P.; Caboni, M. F. Determination of lipid and phenolic fraction in two hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) cultivars grown in Poland. Food Chemistry 2014, 168, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özmen, S. Responses of hazelnut trees to organic and conventional managements in the dryland. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2017, 60, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. Zhai, Q. The dynamics and correlation between nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and calcium in a hazelnut fruit during its development. Frontiers of Agriculture in China 2010, 4, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, C.; Bacchetta, L.; Bellincontro, A.; Cristofori, V. Advances in cultivar choice, hazelnut orchard management, and nut storage to enhance product quality and safety: an overview. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2020, 101, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannico, A.; Modarelli, G. C.; Stazi, S. R.; Giaccone, M.; Romano, R.; Rouphael, Y.; Cirillo, C. Foliar Nutrition Influences Yield, Nut Quality and Kernel Composition in Hazelnut cv Mortarella. Plants 2023, 12, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, É.-B.; Becze, A.; Laslo, É.; Mara, G. Beneficial soil microbiomes and their potential role in plant growth and soil fertility. Agriculture 2024, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Mougel, C.; Jaillard, B.; Hinsinger, P. Plant-microbe-soil interactions in the rhizosphere: an evolutionary perspective. Plant and Soil 2009, 321, 83–115. [Google Scholar]

- Das, P. P.; Singh, K. R.; Nagpure, G.; Mansoori, A.; Singh, R. P.; Ghazi, I. A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, J. Plant-soil-microbes: A tripartite interaction for nutrient acquisition and better plant growth for sustainable agricultural practices. Environmental Research 2022, 214, 113821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R. L.; Pieterse, C. M. J.; Bakker, P. A. H. M. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends in Plant Science 2012, 17, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J. M.; Lemanceau, P.; Van Der Putten, W. H. Going back to the roots: the microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W. , Parton, W. J., Gonzalez-Meler, M. A., Phillips, R., Asao, S., McNickle, G. G., Brzostek, E., & Jastrow, J. D. Synthesis and modeling perspectives of rhizosphere priming. New Phytologist 2014, 201, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lau, J. A.; Lennon, J. T. Evolutionary ecology of plant–microbe interactions: soil microbial structure alters selection on plant traits. New Phytologist 2011, 192, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez-Romero, Y.; Navarro-Noya, Y. E.; Reynoso-Martínez, S. C.; Sarria-Guzmán, Y.; Govaerts, B.; Verhulst, N.; Dendooven, L.; Luna-Guido, M. 16S metagenomics reveals changes in the soil bacterial community driven by soil organic C, N-fertilizer and tillage-crop residue management. Soil and Tillage Research 2016, 159, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X.B Dai et al. Soil microbial community composition and its role in carbon mineralization in long term fertilization paddy soils. Sci total Environ 2015, 580, 556–53.

- Guo, Z.; Wan, S.; Hua, K.; Yin, Y.; Chu, H.; Wang, D.; Guo, X. Fertilization regime has a greater effect on soil microbial community structure than crop rotation and growth stage in an agroecosystem. Applied Soil Ecology 2020, 149, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lori, M.; Hartmann, M.; Kundel, D.; Mayer, J.; Mueller, R. C.; Mäder, P.; Krause, H.-M. Soil microbial communities are sensitive to differences in fertilization intensity in organic and conventional farming systems. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2023, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, T.P.R.A. , Catalano, S.R., Wos-Oxley, M.L., Stephens, F., Landos, M., Bansemer, M.S., Stone, D.A.J., Qin, J.G., Oxley, A.P.A., 2018. The Inner Workings of the Outer Surface: Skin and Gill Microbiota as Indicators of Changing Gut Health in Yellowtail Kingfish. Front. Microbiol 2664, 8, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, C. H.; Leifert, C.; Cummings, S. P.; Cooper, J. M. Impacts of organic and conventional crop management on diversity and activity of Free-Living nitrogen fixing bacteria and total bacteria are subsidiary to temporal effects. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancon, N.Q. , Edwards, C.A., Bierman, P., Metzger, J.D., Lucht, C., . Effects of vermicomposts produced from cattle manure, food waste and paper waste on the growth and yield of peppers in the field. Pedobiologia 2005, 49, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Gómez-Brandón, M.; Revilla, P.; Domínguez, J. Short-term effects of organic and inorganic fertilizers on soil microbial community structure and function. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2012, 49, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodríguez, C.; Palo, C.; Palo, E.; Rodríguez-Molina, M.C. Control of Phytophthora nicotianae with Mefenoxam, Fresh Brassica Tissues, and Brassica Pellets. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaya, J.; Lacasa, C.; Lacasa, A.; Martínez, V.; Santísima-Trinidad, A.B.; Pascual, J.A.; Ros, M. Characterization of Phytophthora nicotianae isolates in southeast Spain and their detection and quantification through a real-time TaqMan PCR. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotti, R.; Mitchell, A. L.; Pane, C.; Finn, R. D.; Zaccardelli, M. Microbiota characterization of agricultural green Waste-Based suppressive composts using omics and classic approaches. Agriculture 2020, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Mallamaci, C.; Settineri, G.; Calamarà, G. Increasing Soil and Crop Productivity by Using Agricultural Wastes Pelletized with Elemental Sulfur and Bentonite. Agronomy Journal 2017, 109, 1900–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffia, A.; Marra, F.; Canino, F.; Oliva, M.; Mallamaci, C.; Celano, G.; Muscolo, A. Comparative Study of Fertilizers in Tomato-Grown Soils: Soil quality, Sustainability, and Carbon/Water Footprints. Soil Systems 2023, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. , Moon, C.D., Zheng, N. et al. Opportunities and challenges of using metagenomic data to bring uncultured microbes into cultivation. Microbiome 10, 76. [CrossRef]

- Mr, P.; F, M.; A, M.; C, M.; A, M. Recycling of agricultural (orange and olive) bio-wastes into ecofriendly fertilizers for improving soil and garlic quality. Resources Conservation & Recycling Advances 2022, 15, 200083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Methods of Analysis for Soils of Arid and Semi-Arid Regions; Food and Agricultural Organization: Rome, Italy, 2007; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, T.; Caddell, D. F.; Deng, S.; Coleman-Derr, D. Exploring the Root Microbiome: Extracting Bacterial Community Data from the Soil, Rhizosphere, and Root Endosphere. Journal of Visualized Experiments No. 135. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, T.Y. , and Matsumoto, M. () An improved DNA extraction method using skim milk from soils that strongly adsorb DNA. Microbes Environ 2004, 19, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhariwal, A. Microbiome Analyst: a web based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbioma data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kers, J. G.; Saccenti, E. The Power of Microbiome Studies: Some considerations on which alpha and beta metrics to use and how to report results. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J. , Liu P Zhou G, Xia J. Using microbiome analyst for comprehensive statistical, functional and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nature Protocols 2020, 15, 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, A. Nonparametric-estimation of the number of classes in a Population. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 1984, 11, 265e270. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, L. N.; Fulthorpe, R. R.; Triplett, E. W.; Roesch, L. F. W. Rethinking microbial diversity analysis in the high throughput sequencing era. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2011, 86, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A. E. (2013). Measuring Biological Diversity. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bray RJ, Curtis JT. An ordination of the upland forestcommunities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol Monogr 1957, 27, 325–349. [CrossRef]

- Bardou, P.; Mariette, J.; Escudié, F.; Djemiel, C.; Klopp, C. jvenn: an interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinformatics 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, J.; Duan, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, Q.; Liu, M.; Xue, C.; Guo, S.; Shen, Q.; Ling, N. Long-term manure inputs induce a deep selection on agroecosystem soil antibiotic resistome. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 436, 129163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hu, H.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Xiu, W. Chemical fertilizer reduction with organic material amendments alters co-occurrence network patterns of bacterium-fungus-nematode communities under the wheat–maize rotation regime. Plant and Soil 2022, 473, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ni, T.; Li, Y.; Xiong, W.; Ran, W.; Shen, B.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Responses of bacterial communities in arable soils in a Rice-Wheat cropping system to different fertilizer regimes and sampling times. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ji, L.; Wan, Q.; Li, H.; Li, R.; Yang, Y. Short-Term Effects of Bio-Organic Fertilizer on Soil Fertility and Bacterial Community Composition in Tea Plantation Soils. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, X.; Xi, Y. Responses of microbial activity, abundance, and community in wheat soil after three years of heavy fertilization with manure-based compost and inorganic nitrogen. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 2015, 213, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Wu, Z.; You, Z.; Yi, X.; Ni, K.; Guo, S.; Ruan, J. Effects of organic substitution for synthetic N fertilizer on soil bacterial diversity and community composition: A 10-year field trial in a tea plantation. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 2018, 268, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Fu, R.; Hou, X.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Miao, Y.; Krell, T.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Chemotaxis of Beneficial Rhizobacteria to Root Exudates: The First Step towards Root–Microbe Rhizosphere Interactions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, F.; Maffia, A.; Canino, F.; Greco, C.; Mallamaci, C.; Adele, M. Effects of fertilizer produced from agro-industrial wastes on the quality of two different soils. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 2023, 69, 3600–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffia, A.; Marra, F.; Celano, G.; Oliva, M.; Mallamaci, C.; Hussain, M.I.; Muscolo, A. Exploring the Potential and Obstacles of Agro- Industrial Waste-Based Fertilizers. Land 2024, 13, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, M. Chemical fertilizer reduction with organic fertilizer effectively improve soil fertility and microbial community from newly cultivated land in the Loess Plateau of China. Applied Soil Ecology 2021, 165, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Xia, Q.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Yang, Z. Rhizosphere soil properties, microbial community, and enzyme activities: Short-term responses to partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic manure. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 299, 113650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Menezes, A. B.; et al. C/N ratio drives soil actinobacterial cellobiohydrolase gene diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3016–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. , Singh, B. & Sitaula, B. Soil organic carbon fractions under diferent land uses in Mardi watershed of Nepal. Commun. Soil Sci. Plan. 35, 615–629.

- Liu, Z. , Guo, Q., Feng, Z., Liu, Z., Li, H., Sun, Y., Liu, C., & Lai, H. (2019). Long-term organic fertilization improves the productivity of kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis Planch.) through increasing rhizosphere microbial diversity and network complexity. Applied Soil Ecology 2019, 147, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, F. , Bradford, M.A., Jackson, R.B. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology 2007, 88, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, P. , Anderson, I. C., & Singh, B. K. Microbial modulators of soil carbon storage: integrating genomic and metabolic knowledge for global prediction. Trends in Microbiology 2013, 21, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalam, S.; Basu, A.; Ahmad, I.; Sayyed, R. Z.; El-Enshasy, H. A.; Dailin, D. J.; Suriani, N. L. Recent understanding of soil acidobacteria and their ecological significance: A Critical review. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichorst, S. , Basu, A., Ahmad, I., Sayyed, R. Z., El-Enshasy, H. A., Dailin, D. J., & Suriani, N. L. Recent understanding of soil acidobacteria and their ecological significance: A Critical review. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzyński, J.; Wróbel, B.; Górska, E. B. Taxonomy, ecology, and cellulolytic properties of the genus bacillus and related genera. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, F.; He, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, K. Increased organic fertilizer application and reduced chemical fertilizer application affect the soil properties and bacterial communities of grape rhizosphere soil. Scientific Reports 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cui, S.; Wu, L.; Qi, W.; Chen, J.; Ye, Z.; Ma, J.; Liu, D. Effects of bio-organic fertilizer on soil fertility, yield, and quality of tea. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2023, 23, 5109–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sha, C.; Wang, M.; Ye, C.; Li, P.; Huang, S. Effect of organic fertilizer on soil bacteria in maize fields. Land 2021, 10, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivojienė, D.; Masevičienė, A.; Žičkienė, L.; Ražukas, A.; Kačergius, A. Soil Microbial Community Structure and Carbon Stocks Following Fertilization with Organic Fertilizers and Biological Inputs. Biology 2024, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, C.; Xiao, X.; Shi, L.; Cheng, K.; Wen, L.; Li, W. Effects of short-term manure nitrogen input on soil microbial community structure and diversity in a double-cropping paddy field of southern China. Scientific Reports 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang H-X, Haudenshield JS, Bowen CR and Hartman GL.Metagenome-Wide Association Study and Machine Learning Prediction of Bulk Soil Microbiome and Crop Productivity. Front. Microbiol 2017, 8, 519. [CrossRef]

- Leliaert, F.; Smith, D. R.; Moreau, H.; Herron, M. D.; Verbruggen, H.; Delwiche, C. F.; De Clerck, O. Phylogeny and molecular evolution of the green algae. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2012, 31, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B. Snow ball earth and the split of Streptophyta and Chlorophyta. Trends in Plant Science 2012, 18, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, F.H. , Li T.L., Qin X.R., Zhao X.D., Jiang L.W., Xie Y.H. Effect of fertilisation on fungal community in topsoil of winter wheat field. Plant Soil Environ 2022, 68, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.K. , Tarafdar J.C. Penicillium purpurogenum, unique P mobilizers in arid agro-ecosystems. Arid Land Research and Management 2011, 25, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, A. , Pal R.K., Chandra R., Singh N.V. Penicillium pinophilum – a novel microorganism for nutrient management in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Scientia Horticulturae 2014, 169, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damo, J.L.C.; Shimizu, T.; Sugiura, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Agake, S.-i.; Anarna, J.; Tanaka, H.; Sugihara, S.; Okazaki, S.; Yokoyama, T.; et al. The Application of Sulfur Influences Microbiome of Soybean Rhizosphere and Nutrient-Mobilizing Bacteria in Andosol. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, M. V.; Krasnov, G. S.; Semenov, V. M.; Van Bruggen, A. Mineral and organic fertilizers distinctly affect fungal communities in the crop rhizosphere. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Effects of Different Proportions of Organic Fertilizer in Place of Chemical Fertilizer on Microbial Diversity and Community Structure of Pineapple Rhizosphere Soil. Agronomy 2024, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, L. ; Sun,F.; Ma, Y.; Yin, D.; Gao, Q.; Zheng, G.;Lv, Y. Combined Organic and Inorganic Fertilization Can EnhanceDry Direct-Seeded Rice Yield byImproving Soil Fungal Communityand Structure. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, A. B. A.; Kahrizi, D.; Ahmadvand, A.; Bashiri, H.; Fakhri, R. Identification of Thiobacillus bacteria in agricultural soil in Iran using the 16S rRNA gene. Molecular Biology Reports 2018, 45, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Li, J.; Lyu, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, G.; Yang, H.; Gao, C.; Jin, L.; Yu, J. Chemical fertilizer reduction combined with bio-organic fertilizers increases cauliflower yield via regulation of soil biochemical properties and bacterial communities in Northwest China. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Wang, G.; Jin, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, H.; Qu, J. Organic amendment improves rhizosphere environment and shapes soil bacterial community in black and red soil under lead stress. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 416, 125805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, S.; Penttinen, P.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zou, L. Organic fertilizers shape soil microbial communities and increase soil amino acid metabolites content in a blueberry orchard. Microbial Ecology 2022, 85, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell, T. Microcalorimetry: a response to challenges in modern biotechnology. Microbial Biotechnology 2007, 1, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.-C.; Li, H.-Y.; Lin, Z.-A.; Zhao, B.-Q.; Sun, Z.-B.; Yuan, L.; Xu, J.-K.; Li, Y.-Q. Long-term fertilization alters soil properties and fungal community composition in fluvo-aquic soil of the North China Plain. Scientific Reports 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromberger, M. E.; Shah, Z.; Westfall, D. G. High specific activity in low microbial biomass soils across a no-till evapotranspiration gradient in Colorado. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2010, 43, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Berbel, N.; Ortega, R.; Lucas-Borja, M. E.; Solé-Benet, A.; Miralles, I. Long-term effects of two organic amendments on bacterial communities of calcareous mediterranean soils degraded by mining. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 271, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Shi, H.; Tao, J.; Jin, J.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, P.; Xiang, B.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Tan, J.; Cao, P. Metagenomic insights into the changes in the rhizosphere microbial community caused by the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in tobacco. Environmental Research 2022, 216, 114848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Fan, K.; Xu, Z.; Yuan, C.; Jia, H.; Ren, Y.; Ding, Z. Differential responses of the rhizosphere microbiome structure and soil metabolites in tea (Camellia sinensis) upon application of cow manure. BMC Microbiology 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betzel, C. , et al. . “Structure of a serine protease proteinase K from Tritirachium album Limber at 0.98 Å resolution. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 3080–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavitha, T. , Priya, R., & Sunitha, T. (2020). Dactylella. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 809–816). [CrossRef]

- Fatima N, Muhammad SA, Khan I, Qazi MA et al Chaetomium endophytes: a repository of pharmacologically active metabolites. Acta Physiol Plant 2016, 38, 136. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.-S.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Yan, W.; Cao, L.-L.; Xiao, Y.; Ye, Y.-H. Chaetomium globosum CDW7, a potential biological control strain and its antifungal metabolites. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2016, fnw287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical properties | Value |

| pH (H2O) | 7.8 ± 0.04 |

| EC (mS cm-1) | 2.6 ± 0.27 |

| Moisture (g kg-1 fw) | 383 ± 0.3 |

| C % (g kg-1 dw) | 426 ± 0.4 |

| Total N (g kg-1 dw) | 19.6 ± 0.1 |

| C/N | 21.7 ± 0.3 |

| Na + (mg g-1 dw) | 4.35 ± 0.02 |

| NH4+ (mg g-1 dw) | 1.50 ± 0.01 |

| K+ (mg g-1 dw) | 9.13 ± 0.06 |

| Mg2+ (mg g-1 dw) | 1.45 ± 0.43 |

| Ca2+ (mg g-1 dw) | 14.06 ± 1.4 |

| Cl- (mg g-1 dw) | 0.02 ± 0.5 |

| PO43- (mg g-1 dw) | 0.40 ± 0.4 |

| SO42- (mg g-1 dw) | 0.18 ± 2.9 |

| WSB (mg TAE g-1 dw) | 2.5 ± 0.05 |

| Fertilizers | Composition |

|---|---|

| Sulfur Bentonite + Olive Pomace (SBOP) | 5 % of composted olive pomace recovered by a two-phase oil mill 10 % of bentonite clay 85% of elementar Sulfur. |

| Sulfur Bentonite (SB): | 90% of elementar Sulfur 10 % of Bentonite clay |

| Composted Olive Pomace (OP) | 34% of composted olive pomace recovered by a two-phase oil mill 33% of buffalo manure 33% of a mixture consisting of wood defibrate and olive leaves. |

| Synthetic fertilizer (NPK) | 20% of N 10% of P2O5 10% of K2O |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).