1. Introduction

Heilongjiang Province is the largest commercial production region for Acanthopanax senticosus in China [

1]. While the Application of chemical fertilizers enhances the Acanthopanax senticosus yield and bioactive compound content [

2], long-term excessive deteriorates soil physicochemical properties, resulting in agricultural non-point source pollution, and lead to environmental degradation [

3,

4]. Excessive nitrogen input,in particular, not only waste resources, but also lead to environmental pollution and soil degradation [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Consequently, sustainable cultivation practices are imperative meet market demand and protect the wild resources [

26].

Acanthopanax senticosus has specific ecological requirements, thriving within a narrow temperature range (12-18℃) and preferring loose, fertile and well-drained soil [

13]. As a slow-growing plant, it takes 5-7 years to grow from planting to harvesting, necessitating sustained soil fertility. These constraints pose significant challenges to its challenges to its cultivation, underscoring the need for scientifically sound soil management strategies.

Identify reasonable fertilization practices that mitigate the environmental impacts of excessive fertilizer applications is therefore urgent. Integrated fertilization-combining reduced chemical fertilizer with organic fertilizer-has emerged as an environmental friendly practice [

14]. Appropriate organic substitution can enhance Acanthopanax senticosus yield, improve soil nutrient status, and protects soil ecology [

15]. This approach reduces nutrient losses [

16], increase fertilizer use efficiency, elevates soil organic matter [

17], activates soil nutrients, change soil enzyme activity, and enhances the content of bioactive compound in Acanthopanax senticosus [

18]. Furthermore, it enhances soil microbial activity, improves soil fertility, and reduces soil salinization and soil-borne diseases [

19], enhances root activity [

20], boosts antioxidant enzyme activity and leaf pigment content [

21]. It also increases water and fertilizer conservation and ultimately improves Acanthopanax senticosus yield and stress resistance.

Privious study found that conventional fertilization combined with amino acid, fulvic acid, and biogas slurry yielded higher productivity and economic returns than conventional fertilization [

22,

23]. Bio-organic fertilizers outperformed conventional organic fertilizers in improving phosphorus use efficiency; replacing 40% of chemical fertilizer with bio-organic fertilizer significantly increased both yield and active chemical ingredients [

24]. Combined fertilization also increased the abundance of bacteria and actinomycetes, decreased the abundance of fungi, and increased activities of urease, catalase, sucrose, and alkaline phosphatase [

25]. A 30% reduction in nitrogen fertilization reduced soil electrical conductivity and improved nutrient content, leading to higher yield and bioactive compound content [

26]. These findings confirm the economic and agronomic viability of reduced chemical fertilization supplemented with organic inputs.

However, few studies have focused on how such practices influence the soil microbial community structure and function in

Acanthopanax senticosus systems. Microbial communities are sensitive indicators of soil health and are crucial in nutrient cycling and plant health. For instance, in maize silage, increased nitrogen fertilization raised the abundance of aerobic bacteria, yeasts, and lactic acid bacteria but reduced mold abundance [

27]. Similarly, in rice grains, appropriate nitrogen application promoted beneficial microbial colonization more effectively than either deficient or excessive application [

28].

In this study, we conducted a pot experiment to investigate the effects of different fertilization regimes on soil nutrient dynamics and microbial community structure. We hypothesized that (1) reducing chemical fertilizer combined with organic fertilizer enhances soil nutrient availability; and (2) such practice significantly changes the structure and diversity of soil microbial communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Soil Sampling

A pot experiment was conducted at the Institute of Nature and Ecology of Heilongjiang Academy of Sciences (126.65 E, 45.71 N). Soil samples were collected at the harvest time of Acanthopanax senticosus in September 2024. Four fertilization treatments were established: T1, T2, T3 and T4. Each pot was pre-amended with a basal application of 40 g of fermented fungal chaff (rotted wood chips) and 120 g of decomposed cow manure, mixed with 6.6 kg of raw soil. T1 (Conventional fertilization) received a total nutrient input equivalent to 1.5 kg of urea, 12 kg of ammonium phosphate, and 6 kg of potassium sulfate per 667 m². T2, T3, T4 (Reduced fertilization) received 20%, 40%, and 60% reductions in total chemical nutrients, respectively, based on the T1 regimen.

At harvest, soil samples were collected from each pot. Visible stones and plant residues were removed, and the soil was passed through a 2-mm sieve. Each sample was divided into two subsamples: one was air-dried for the analysis of soil physicochemical properties, and the other was stored at -80°C for subsequent DNA extraction and microbial community analysis.

At harvest, soil samples were collected from each pot. Visible stones and plant residues were removed, and the soil was passed through a 2-mm sieve. Each sample was divided into two subsamples: one was air-dried for the analysis of soil physicochemical properties, and the other was stored at -80°C for subsequent DNA extraction and microbial community analysis.

2.2. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

Soil physicochemical properties were determined according to the method [

29]. Specifically: soil organic matter was determined by sulfuric acid oxidation with potassium chromatic; soil alkaline nitrogen was determined by alkaline diffusion, soil available phosphorus was determined by scandium molybdenum antimony cliometric method, and soil total nitrogen was determined by Heyerdahl method.

2.3. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

According to the instructions, total soil DNA was extracted from 1g of fresh soil using a soil DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.). DNA was quantified by agarose gel electrophoresis and NANODROP, and all DNA concentrations were adjusted to 50ng/μL and used for subsequent PCR. Bacterial PCR amplification was performed using universal primers 341F: 5′-ACTCCTACGGAGGCAGCA-3′; 806R: 5′-GGACTACHVGGGGTTTCTAAT-3′ for V3-V4 region of 16S ribosomal RNA gene, with TransStart Fastpfu DNA polymerase, 20μL Reaction system: 5× FastPfu buffer 4μL, 2μL 2.5mM DNTPs, 0.8μL each forward primer (5μM) primer and reverse primer (5μM) primer, 0.4μL Fast Pfu polymerase and 10ng template DNA, supplemented with H2O to 20μL. The amplification procedure was: predenaturation at 95°C for 2min, followed by 25cycles of amplification: 95°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s and finally extension at 72°C for 5min. The Fungal PCR amplification was performed using primers ITS1F (F:CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA; R:GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC). According to the instructions, PCR products were purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, U.S.). Purified PCR products were quantified using Qubit 3.0 (Life Invitrogen), and amplicons from each of the 24 barcodes were mixed equally. After adding the barcode to each PCR product, the mixed DNA products were used to prepare Illumina pair-end libraries according to the Illumina genomic DNA library preparation procedure. The amplicon libraries were then subjected to 2×250 paired-end sequencing on the Illumina platform according to standard protocols.

2.4. Bioinformatic Analyses

Raw sequencing data were processed using the QIIME2 pipeline (2023.5 distribution). Sequences were quality-filtered, denoised, and merged using the DADA2 plugin to infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), which provide a higher resolution than traditional OTU clustering [

30]. Chimeric sequences were identified and removed. Taxonomy was assigned to the 16S rRNA and ITS ASVs using the classify-sklearn naive Bayes classifier trained on the SILVA (SSU138) and UNITE (v9.0) reference databases for bacteria and fungi, respectively, with a confidence threshold of 80% [

31].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the BMKCloud online platform (

https://www.biocloud.net/) and SPSS software (version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's honest significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test was used to determine significant differences (P < 0.05) in soil properties and alpha-diversity indices among treatments. Alpha diversity within samples was assessed using the Chao1 and ACE (richness), Shannon and Simpson (diversity) indices. Rarefaction curves were generated to evaluate sequencing depth. Beta diversity between samples was analyzed based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices and visualized via principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was used to test for significant differences in microbial community structure among groups. Differential abundance analysis of taxa (biomarkers) between specific groups was identified using statistical methods such as linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) or the Kruskal-Wallis test.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Soil Physicochemical Properties Under Different Fertilization Treatments

All the soil physicochemical properties (i.e. pH, AP, AN, TN, TOC) were significantly different among treatments (P<0.05), with the exception of AK (

Table 1). Soil pH exhibited a gradient decrease as fertilizer application was reduced, showing significant differences across all treatments (P < 0.05).The T4 treatment (60% reduction) showed the most pronounced effects on enhancing soil nitrogen and organic carbon accumulation. Its alkaline dissolved nitrogen (AN: 294.47±21.40 mg/kg) and organic carbon (TOC: 2.967±0.002 g/kg) were significantly higher than thost in all other treatments (P<0.05). Total nitrogen content (TN: 0.214±0.001 g/kg) in T4 also reached the highest value. In contrast, the conventional fertilization treatment (T1) resulted in the highest content of available phosphorus (AP: 53.29±2.56 mg/kg) and available potassium (AK: 222.51±17.35 mg). Notably, the T2 treatment (20% reduction) appeared to suppress total nutrient levels, showing the lowest values for TN (0.183±0.001 g/kg), TOC (2.685±0.002 g/kg) and AP (38.47±0.24 mg/kg).

3.2. Soil Microbial α-and β-Diversities Under Different Fertilization Treatments

The α-diversity indices (including Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson) of both bacterial and fungal communities showed no significant differences among the various fertilization treatments (

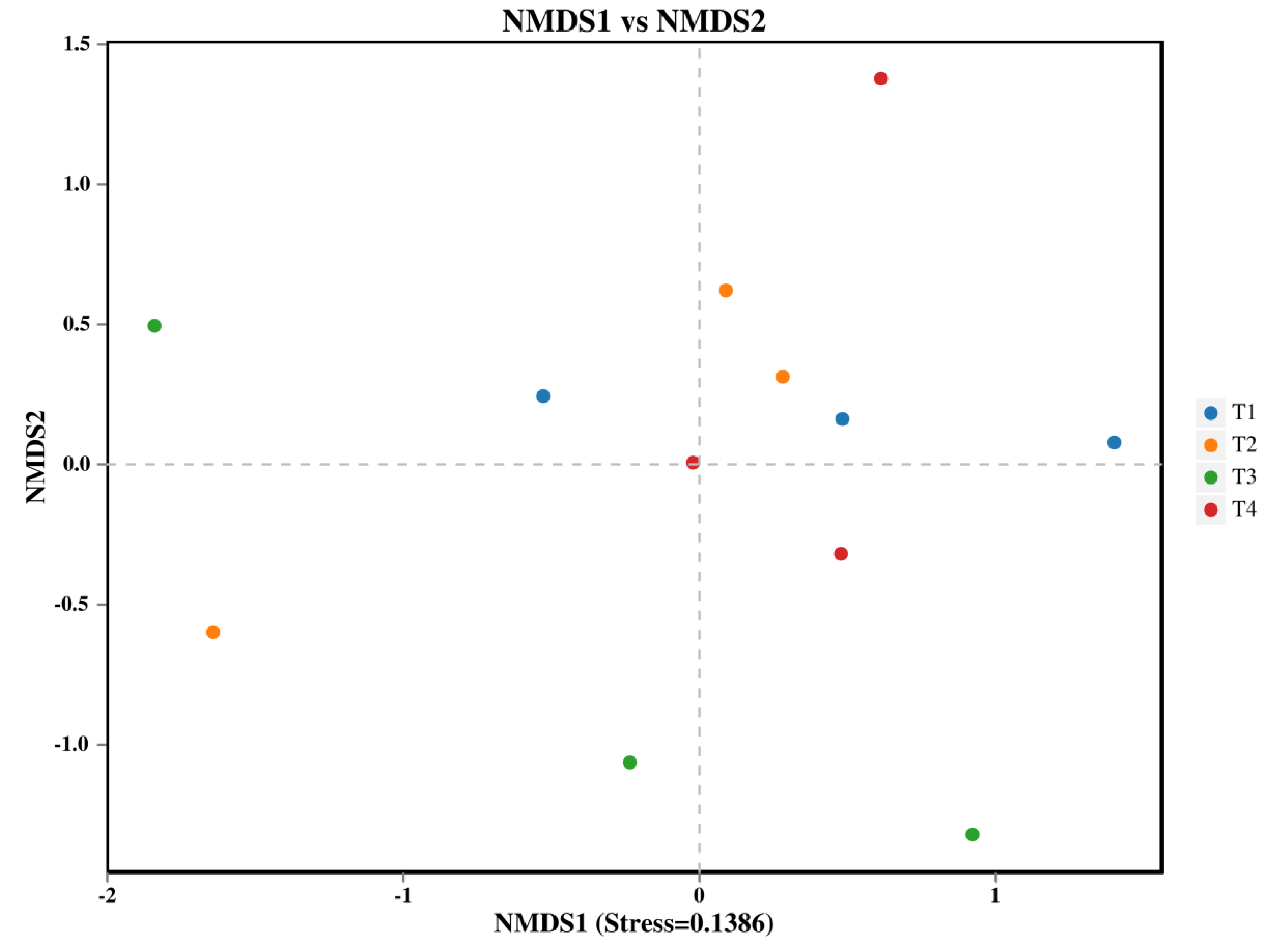

Table 2). In contrast, the β-diversity of the soil bacterial community, analyzed using Non-Metric Multi-Dimensional Scaling (NMDS), was significantly altered by the fertilization regimes (Figure1a, PERMANOVA, P < 0.05). Specifically, the bacterial community structure in the T3 treatment (40% reduction) was significantly distinct from those in both the T1 (conventional fertilization) and T4 (60% reduction) treatments.

Figure 2.

NMDS analysis of soil bacteria: each point in the graph represents a sample; different colors represent different groups.

Figure 2.

NMDS analysis of soil bacteria: each point in the graph represents a sample; different colors represent different groups.

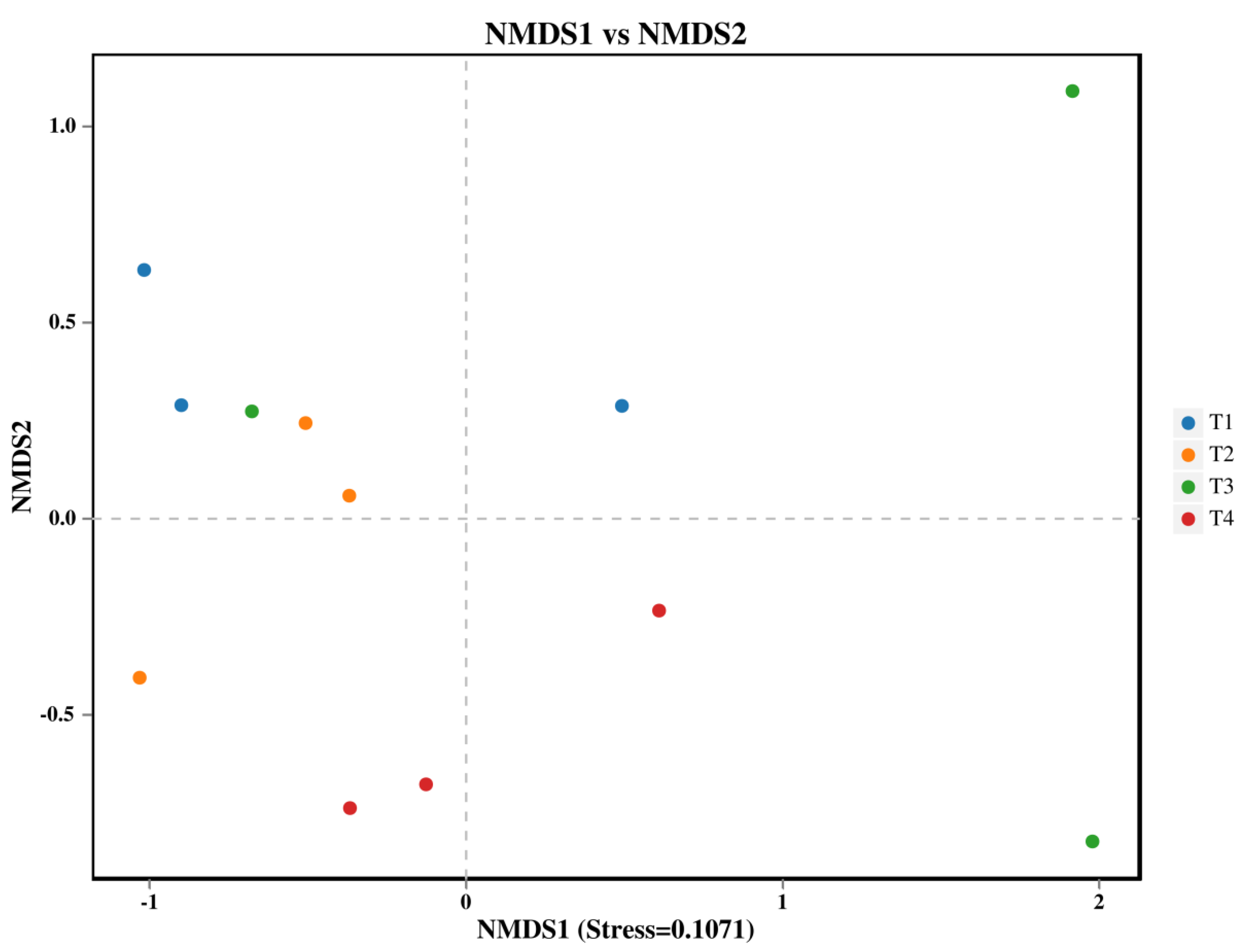

Soil fungal β-diversity changed significantly in different fertilization applications (Figure1a, permanova P<0.05). T1 treatment differed significantly compared to T4 treatment.

Figure 3.

NMDS analysis of soil fungal: each point in the graph represents a sample; different colors represent different groups.

Figure 3.

NMDS analysis of soil fungal: each point in the graph represents a sample; different colors represent different groups.

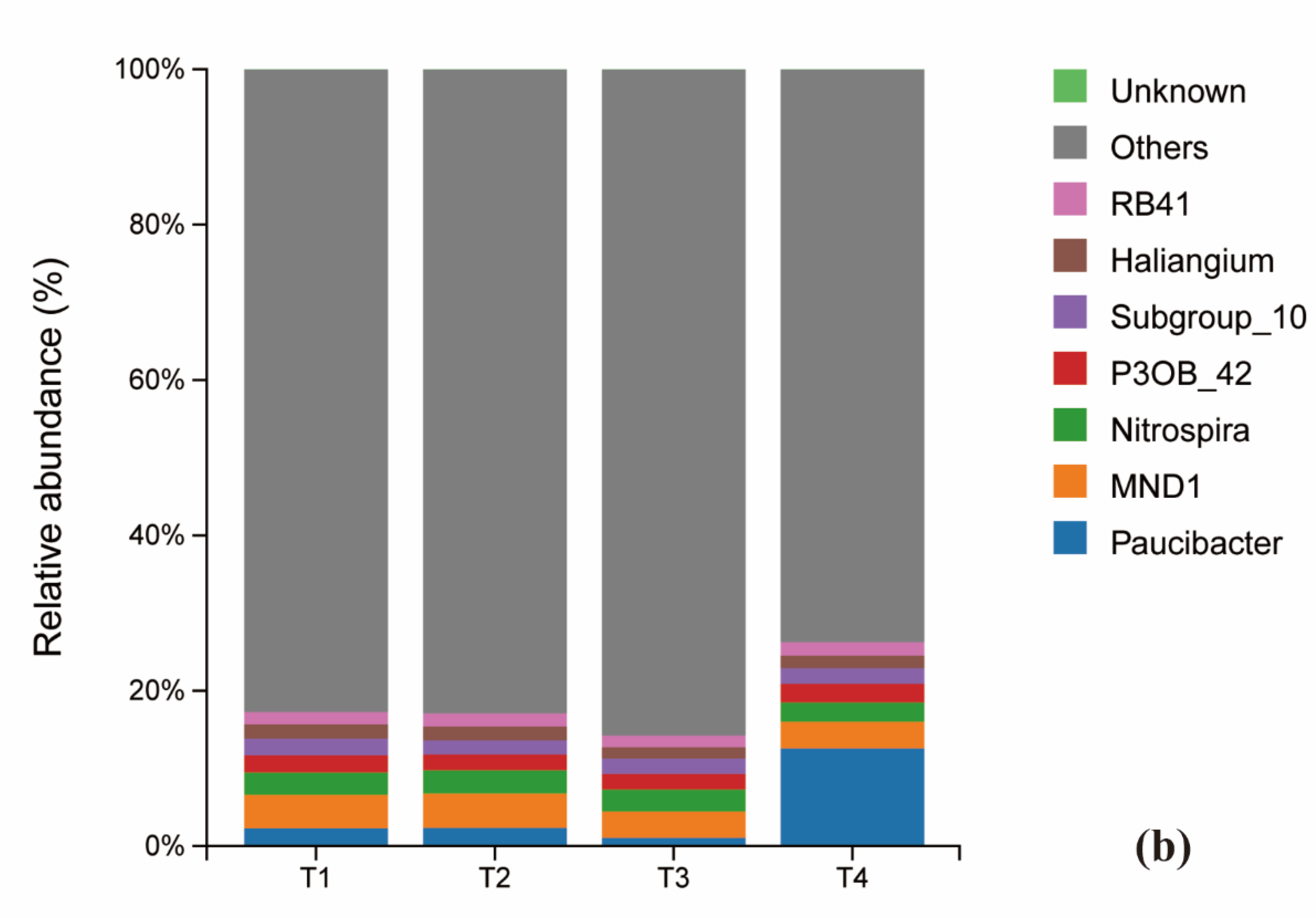

3.3. Soil Microbial Composition in Response to Different Fertilization Measures

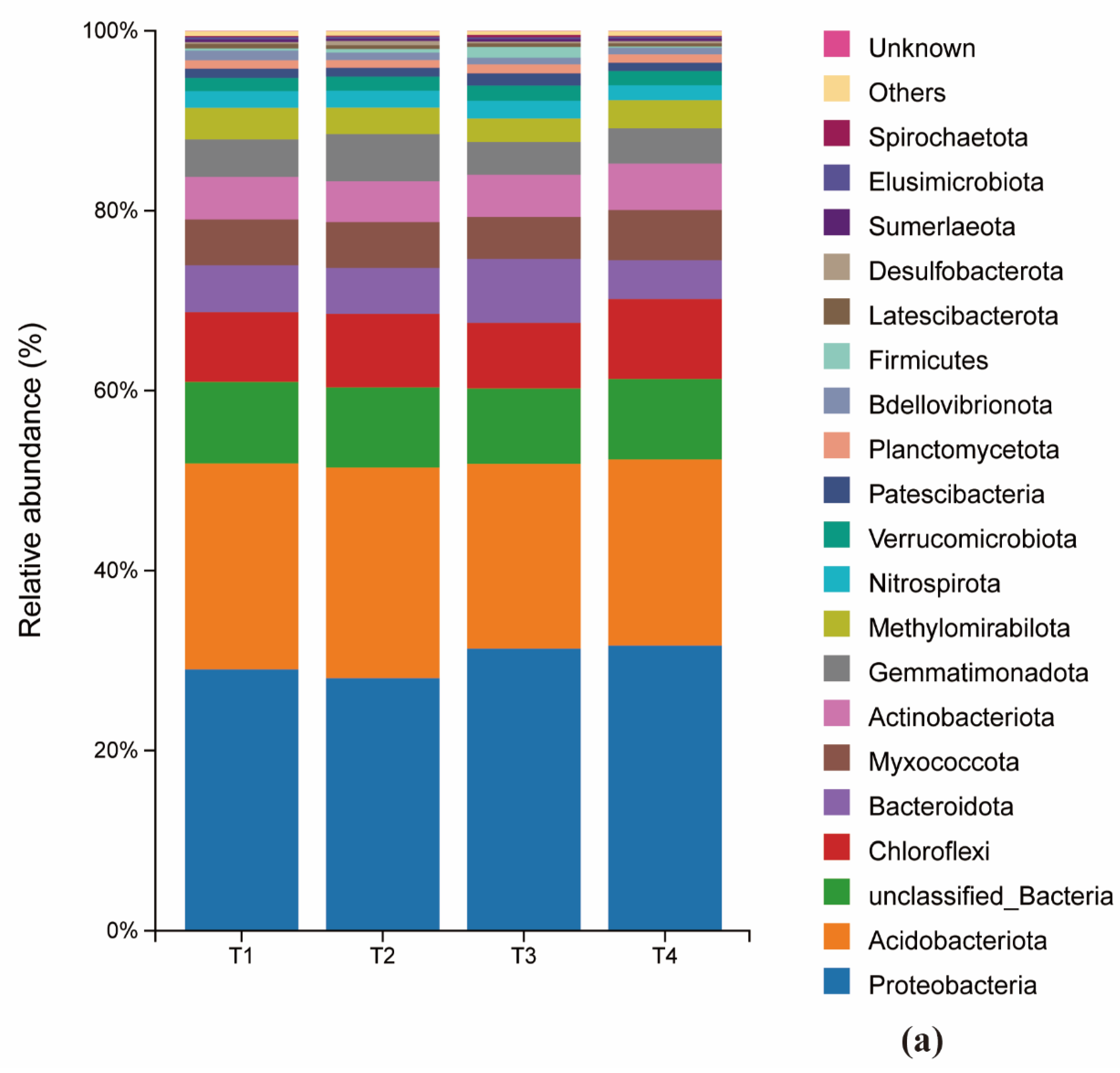

The composition of both bacterial and fungal communities was significantly influenced by the fertilization treatments. At the phylum level, the bacterial communities across all treatments were predominantly composed of proteobacteria (29.0%, 28.1%, 31.3%, 31.7%), Acidobacteria (22.9%, 23.4%, 20.5%, 20.7%). Chloroflexi and Proteobacteria also represented substantial proportions of the community. A notable shift was observed in response to fertilizer reduction: the relative abundance of Bacteroidota decreased initially and then increased, reaching its minimum at T2. Conversely, the abundance of Bacteroidota increased and then decreased, peaking at T2. In contrast, the relative abundances of Myxococota and Actionbacteriota remained relatively stable across treatments (

Figure 4a).

At the genus level of bacteria, the relative abundance of Bactericide changed extremely significantly (1.47%, 1.49%, 0.73%, 8.41%) with the reduction of fertilizer additions, showing a decreasing and then significantly increasing trend, which was significantly higher in the T4 group than in the other treatments; the abundance of the genera of Chloroform, and Gemmatimonadaceae bacteria first increased and then decreased and was significantly higher in T2 group than other treatments; Vicinamibacterales abundance showed a decreasing trend; while Nitrospira abundance had the maximum peak (1.94%) under T3 treatment (

Figure 4b)

.

At the genus level, the relative abundance of Paucibacter changed most dramatically, exhibiting a pattern of decrease followed by a significant increase (T1:1.47%, T2:1.49%, T3:0.73%, T4:8.41%). Its abundance in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than in all other groups. The abundance of Gemmatimonas and bacteria from the family Gemmatimonadaceae first increased and then decreased, with the T2 treatment showing a significantly higher abundance than others. The abundance of Vicinamibacteraceae showed a general decreasing trend across the treatment gradient. Notably, the abundance of the nitrifying genus Nitrospira reached its maximum (1.94%) under the T3 treatment (

Figure 4b).

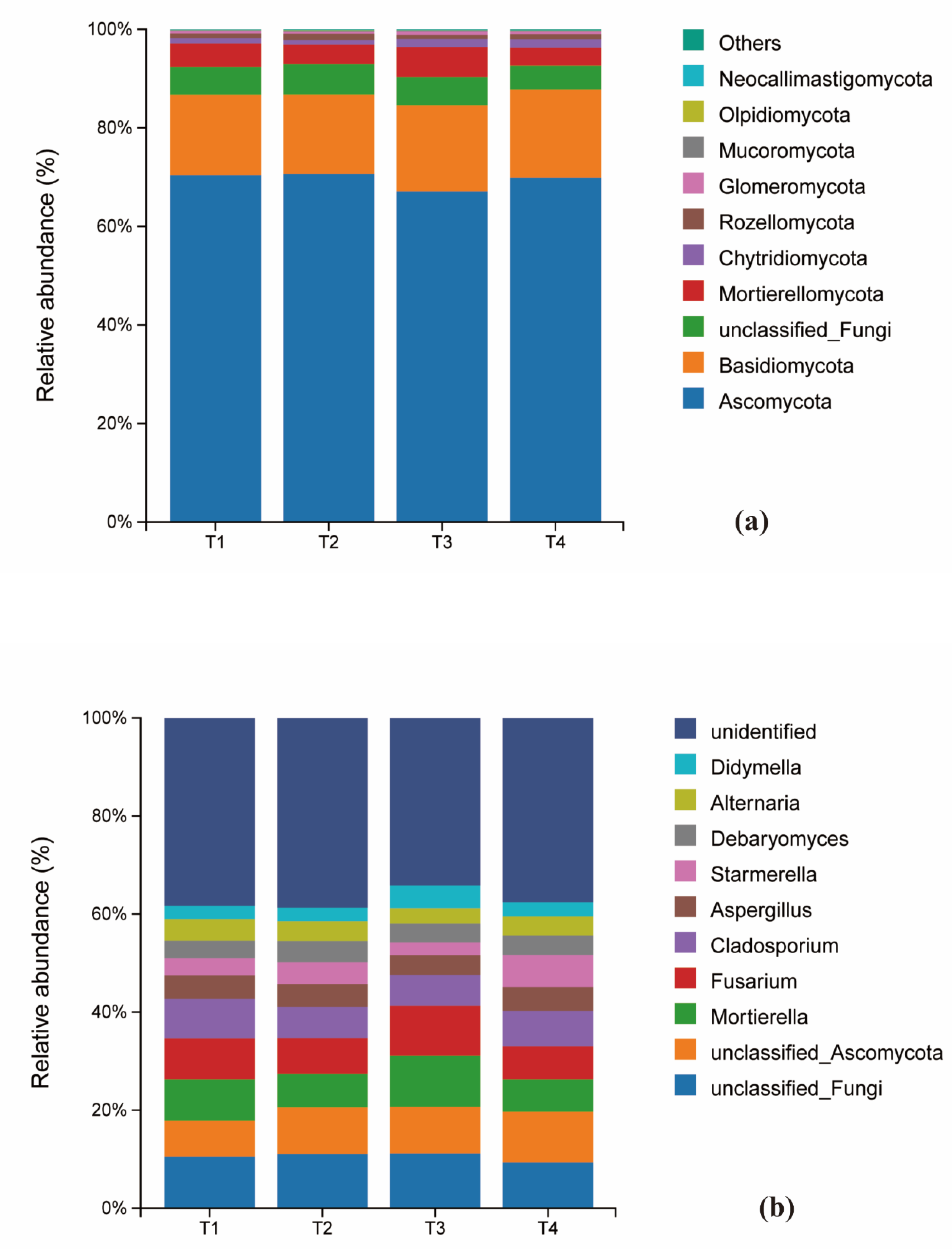

At the phylum level of fungi, Ascomycota was the dominant phylum across all treatments, representing 70.4%, 70.6%, 67.1%, and 69.9% of the communities in T1 through T4, respectively. Notably, its relative abundance in the T3 treatment was lower than in the other treatments. Basidiomycota was the second most abundant phylum. The relative abundances of other fungal phyla remained largely unchanged across the fertilization gradient (

Figure 4c). Significant shifts were observed at the genus level. The relative abundance of Mortierella varied considerably (T1:4.61%, T2:3.89%, T3:5.39%, T4:3.42%), with its abundance in the T4 treatment being significantly lower than in all other treatments. In contrast, the abundance of Cladosporium was highest under the conventional fertilization treatment (T1) compared to the reduced fertilization groups (

Figure 4d).

Figure 5.

Histograms of fungal species distribution under different fertilization levels: sample names on the horizontal axis; percentage of relative

Figure 5. Histograms of fungal species distribution under different fertilization levels: sample names on the horizontal axis; percentage of relative abundance on the vertical axis; different colors indicate different species. Figure (a) shows the composition of soil fungi at the phylum level for the top 10 species in terms of abundance, while figure (b) shows the composition of soil fungi whose abundance ranked among the top 10 at the genus level.

Figure 5.

Histograms of fungal species distribution under different fertilization levels: sample names on the horizontal axis; percentage of relative

Figure 5. Histograms of fungal species distribution under different fertilization levels: sample names on the horizontal axis; percentage of relative abundance on the vertical axis; different colors indicate different species. Figure (a) shows the composition of soil fungi at the phylum level for the top 10 species in terms of abundance, while figure (b) shows the composition of soil fungi whose abundance ranked among the top 10 at the genus level.

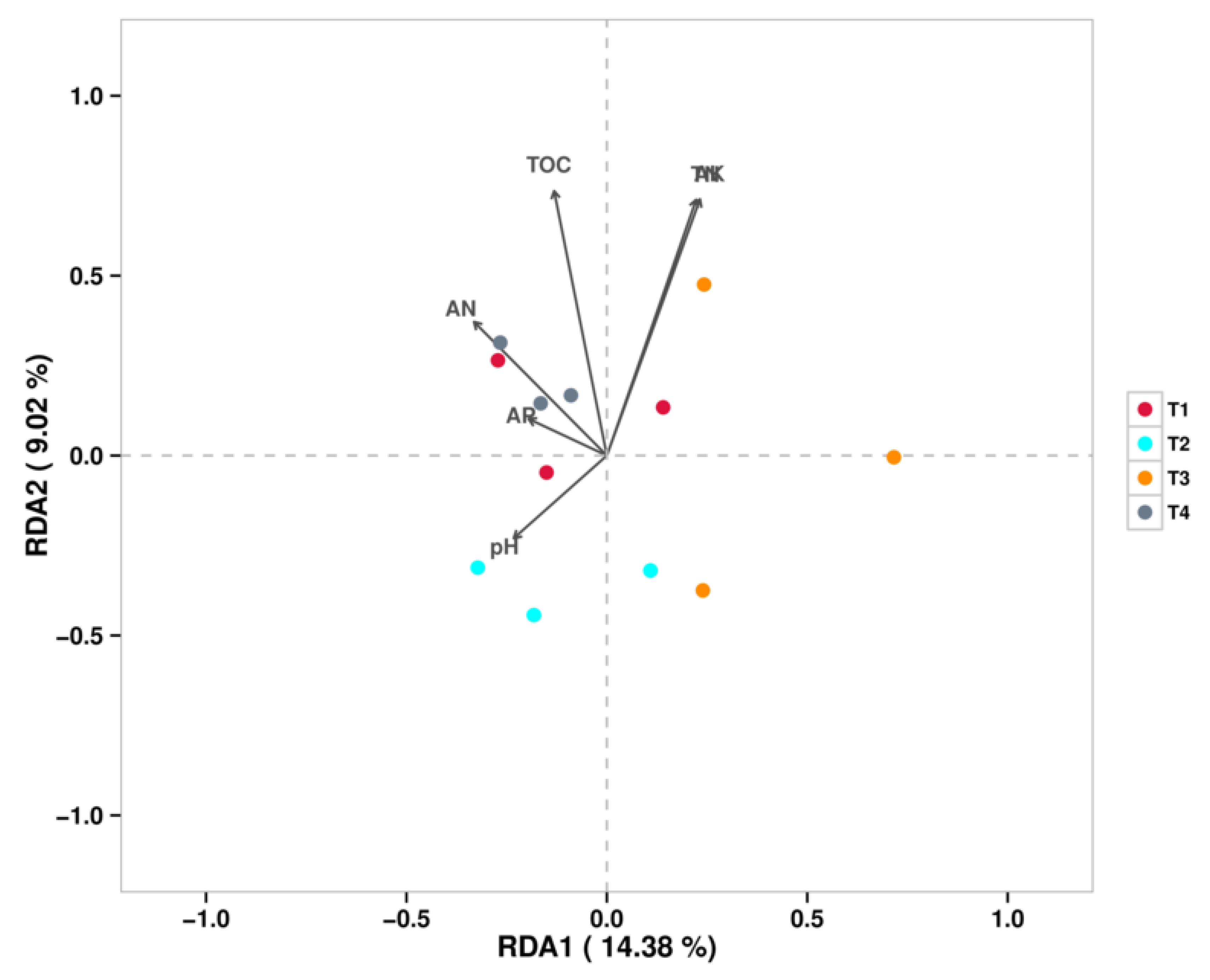

3.4. Relationships Between Soil Microbial Communities and Soil Physicochemical Properties

Redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed to elucidate the relationships between soil bacterial communities (genus level) and environmental variables (

Figure 6). The results indicated that total organic carbon (TOC) was the strongest environmental factor explaining the variations in bacterial community structure under different fertilization regimes. The distribution of bacterial communities from different treatments along the RDA axes revealed distinct correlations with soil properties: The bacterial community in the T1 (conventional fertilization) treatment was positively correlated with total nitrogen (TN), available nitrogen (AN), and available potassium (AK), but negatively correlated with pH. The bacterial community in the T2 (20% reduction) treatment showed a positive correlation with pH but negative correlations with AK and TOC. The bacterial community in the T4 (60% reduction) treatment was positively correlated with AN, TN, and TOC.

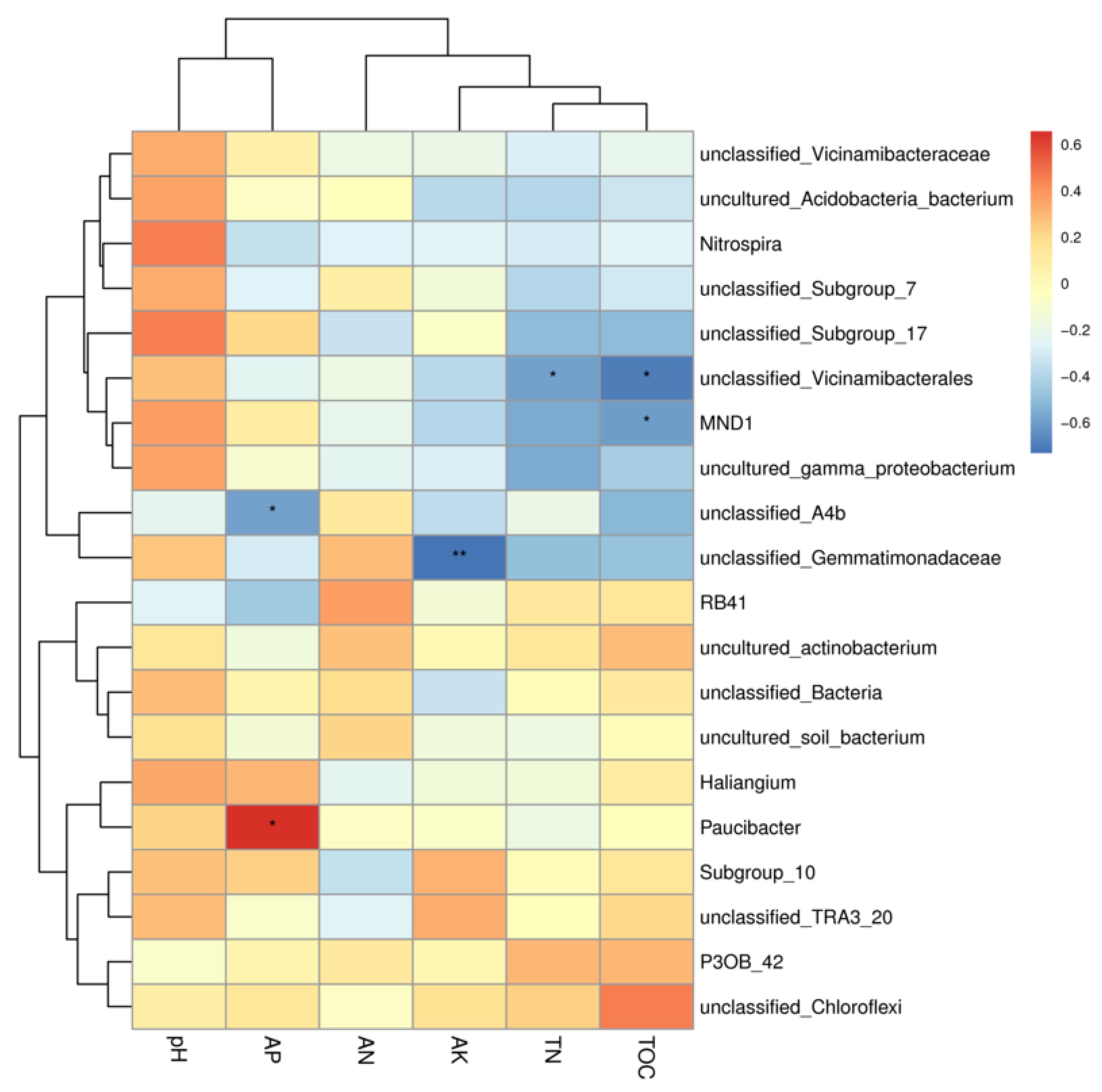

A heat map of the correlation between the 20 most abundant bacterial genera and soil physicochemical properties was made (

Figure 7), in which the main genera in the bacterial community were Nitrospira, Paucibacter, and MND1, whereas Paucibacter showed a strong correlation with AP, Chloroflexi showed a stronger correlation with TOC, and Nitrospira, MND1 and pH also showed a positive correlation, MND1 was also correlated with pH.

A heatmap was constructed to visualize the Spearman correlation coefficients between the relative abundance of the top 20 most abundant bacterial genera and the soil physicochemical properties (

Figure 7). Nitrospira exhibited a significant positive correlation with soil pH. Paucibacter showed a strong positive correlation with available phosphorus (AP). Chloroflexi (representing a phylum; the dominant genus within it should be specified if possible) was strongly positively correlated with total organic carbon (TOC). MND1 (a candidate genus) was positively correlated with pH.

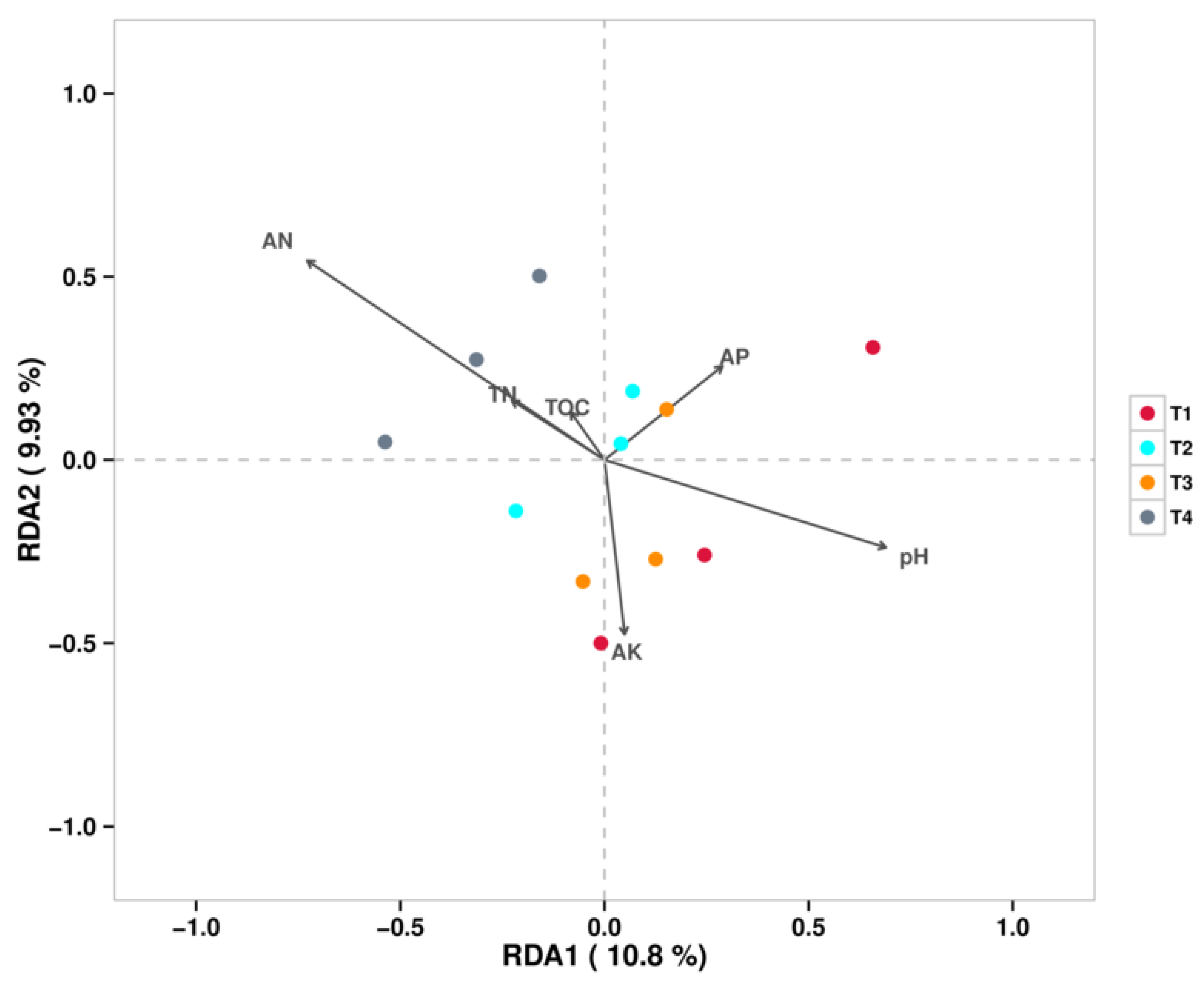

Figure 8 shows the RDA/CCA analysis at the fungal genus level, which indicated that the strongest factor contributing to the differences in soil fungal communities under different fertilization conditions was AN. The soil fungal communities of all T4 treatments were positively correlated with AN and negatively correlated with pH, while Fusarium abundance was positively correlated with pH.

3.5. Significance Analysis of Differences Between Soil Microbiomes of Different Fertilization Practices

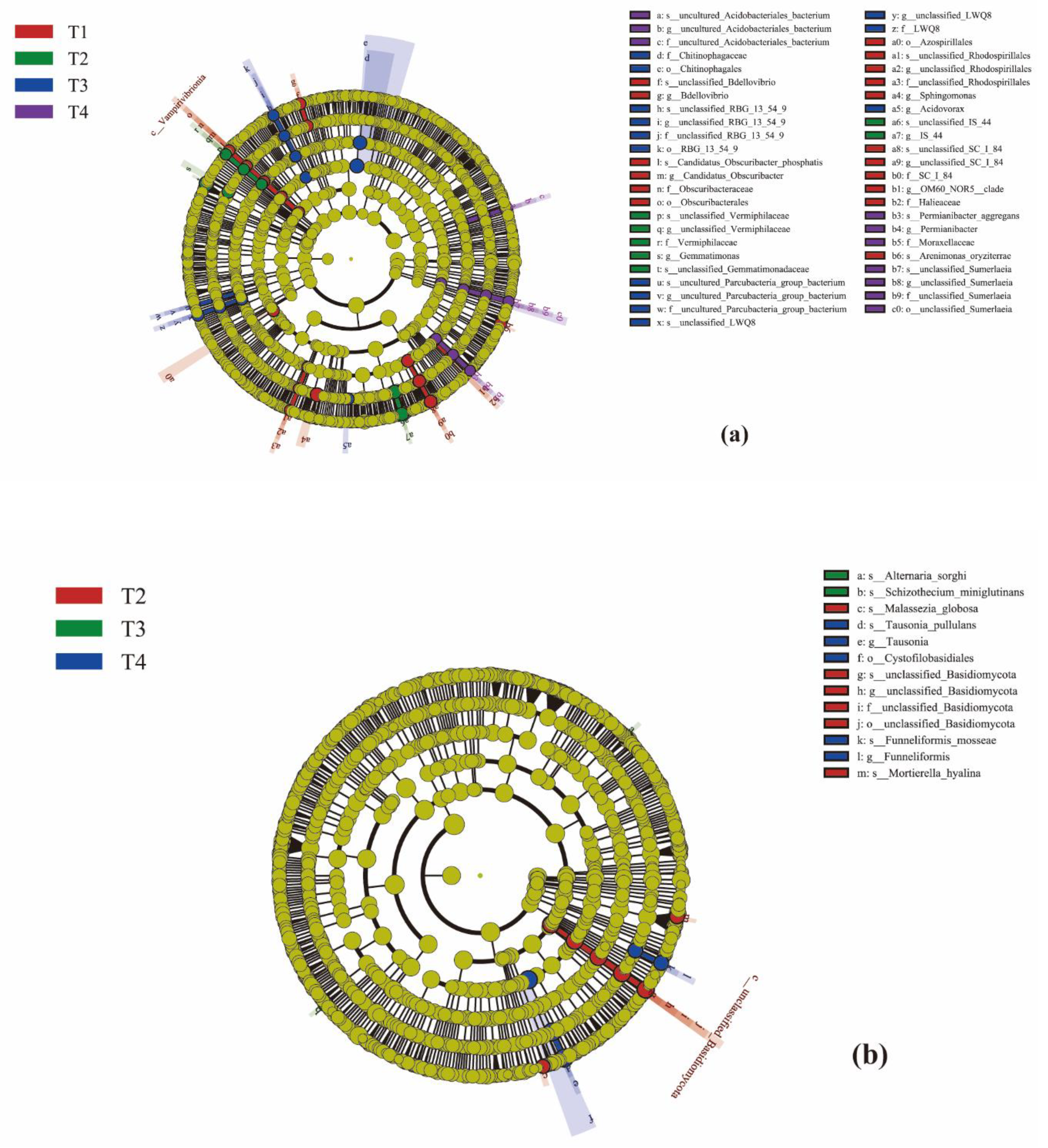

LEfSe (Line Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Effect Size) analysis was able to search for statistically different Biomarkers between groups (

Figure 9a,b). Under the four treatments, Figure a shows differences in 47 bacterial taxa, where LDA > 2.0, and Figure b shows differences in 13 fungal taxa, but only in T2, T3, and T4, where LDA > 2.0.

4. Discussion

4.1. Dual Effects of Fertilizer Application on Soil Fertility

Long-term over-application of chemical fertilizers not only leads to soil structure degradation, nutrient imbalance and declines in enzyme activity ,which can inhibit crop physiological metabolism and growth, thereby threatening the sustainable use of soil resources [

32,

33,

34]. In this study, although the high fertilizer application rate (T1) increased the contents of available phosphorus (AP) and available potassium (AK) (53.29 mg/kg and 222.51 mg/kg, respectively) in the short term, it also induced a significant increase in pH (7.74). This alkalization may inhibit the microbial activity in naturally acidic soils, consistent with previous studies that excessive fertilizer leads to soil acidification or salinization [

35].

In contrast, the low fertilization rate (T4) optimized long-term soil fertility sustainability. It promoted organic matter decomposition (resulting in a TOC of 2.967 g/kg) and achieved the highest total nitrogen (TN) content (0.214 g/kg) among all treatments. This indicates that reducing chemical fertilizer input while incorporating organic matter can effectively enhance soil carbon and nitrogen sequestration capacity, providing a more stable energy source and substrates for microbial activities [

36]. These results verify the advantages of organic-inorganic fertilization in maintaining soil fertility sustainability [

37], which is particularly crucial for slow-growing perennial plants like Acanthopanax that require long-term stable nutrient supply.

Furthermore, the available nitrogen (AN) content under the T4 treatment (294.47 mg/kg) was significantly higher than in other treatments (ranging from 139.23 to 155.27 mg/kg). This suggests that reducing chemical fertilizer combined with organic substrates (e.g., fungal chaff, decomposed cow manure) may more efficiently promote soil organic nitrogen mineralization and/or biological nitrogen fixation. On one hand, lower chemical nitrogen input may reduce the nitrification inhibition effect, potentially enhancing the activity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (e.g., Nitrospira) (

Figure 4b). On the other hand, organic matter input likely stimulated the functional expression of nitrogen-fixing and organic nitrogen-mineralizing bacteria [

38]. This aligns with previous observations in rice studies, where appropriate nitrogen fertilization enhanced microbial colonization to improve seed quality [

28].

4.2. Effect of Fertilization Rate on Microbial Diversity and Structure

Soil microorganisms are one of the key factors in soil nutrient transformation, and their diversity and community structure represent the metabolic capacity of soil ecosystems [

39]. In our analysis of of bacterial and fungal diversity, the reduction in fertilizer application did not lead to obvious differences in diversity indices, which contrasts with the findings of Nie et al. [

40]. This discrepancy may be related to the relatively short duration of our experiment (one year).

Notably, all four diversity indices for the fungal community were highest in the T3 treatment. In contrast, the Shannon index of the bacterial community showed a positive correlation with fertilizer application rate, indicating enhanced community evenness under high-fertilizer conditions. This may stem from excess fertilizer stimulating the explosive growth of a few eutrophic bacterial taxa (e.g., Proteobacteria) to form a dominant community (

Figure 6A). Similarly, studies on silage maize have found that increased nitrogen fertilizer application alters microbial community structure [

27]. However, the Chao1 and ACE indices, reflecting species richness, were lowest in the T2 treatment (20% reduction) and highest in T4 (60% reduction). This suggests that medium-level fertilization (T2) may create ecological stress, where invading populations compete with native species for resources, forcing some microbial taxa to narrow their niche breadth. Conversely, low-level fertilization (T4) combined with organic inputs appeared to create a more heterogeneous environment that facilitated the recovery and coexistence of rare species.

In the microbial community structure analysis, the bacterial phyla Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria emerged as dominant groups, collectively accounting for over 50% of the community and serving as the core drivers of soil nutrient cycling [

41]. Their abundance variations reflect changes in soil nutrient cycling capacity. As fertilizer application decreased, the abundance of Proteobacteria (typically copiotrophic) showed a "V"-shaped trend (lowest in T2), while Acidobacteria (typically oligotrophic) exhibited an inverted "V"-shaped trend (highest in T2). The T2 treatment (20% reduction) may have created a "transition pressure," inhibiting copiotrophic Proteobacteria while transiently promoting oligotrophic Acidobacteria. The 60% reduction in T4, coupled with organic matter supplementation, may have helped re-establish a balance between these two phyla.

The enrichment of Sphingomonas and Gemmatimonas in the T4 group is noteworthy, as these genera are known to promote the synthesis of bioactive compounds like sphingans and can directly enhance medicinal plant quality, aligning with previous studies [

43]. In contrast, the over-expansion of Acidobacteria in T2 may be related to decreased soil carbon metabolism efficiency. Additionally, the increase in methanol-oxidizing bacteria in the T3 group suggests that this fertilization rate might optimize carbon source utilization pathways and reduce energy loss.

The genus Paucibacter showed an increasing trend in relative abundance with fertilizer reduction, reaching its highest level in the T4 treatment (

Figure 6B). Paucibacter has been reported to participate in organic matter degradation (e.g., aromatic compounds) and possesses plant-beneficial potential [

44,

45]. Its dominance in low-fertilizer, high-organic-matter environments (T3, T4) suggests a key role in carbon cycling and plant-root interactions.

The fungal community was primarily dominated by the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, consistent with previous reports [

46], with Trichoderma, Fusarium, and Cladosporium as the top three dominant genera. Ascomycota are a major component of the root-associated soil mycobiome, mostly comprising saprophytes that decompose organic matter and play vital roles in nutrient cycling. However, this phylum also contains many plant pathogens like Fusarium, which causes significant damage through diseases like tobacco wilt and root rot [

47,

48]. Basidiomycota are particularly efficient in decomposing lignocellulose, converting plant residues into plant-available nutrients [

49]. In this study, the abundance of Fusarium was significantly lower in T3 and T4 treatments compared to other groups. This reduction may be related to Fusarium's preference for low-nutrient soils, as its abundance has been shown to be negatively correlated with soil nitrogen content [

50]. Specifically, the significant reduction of Fusarium in T4 aligns with findings that a 20% reduction in conventional nitrogen application with microbial inoculants could effectively reduce Fusarium abundance in tobacco soils [

51]. Similarly, Ding Jianing [

52] found that organic fertilizer substitution could reduce the relative abundance of Ascomycota. These results collectively suggest that reduced fertilizer application promotes soil nutrient cycling and reduces the risk of pathogen proliferation.

4.3. Effects of Soil Properties on Microbial Communities

Both correlation heatmap and redundancy analysis (RDA) of the bacterial community clearly indicated that total organic carbon (TOC) was the strongest environmental factor driving bacterial community differences. The T4 treatment showed strong positive correlations with TOC, AN, and TN. This strongly suggests that the low fertilizer input combined with high organic matter amendments drove microbial community assembly toward a composition potentially more functionally adapted to organic matter degradation and nutrient cycling, shaped by the unique soil nutrient environment created by this management practice. This is consistent with findings from Wang et al. [

53] in mango cultivation and Sun et al. [

54] in tobacco fields, where reduced chemical fertilizer combined with organic amendments improved both soil microbial communities and physicochemical properties. LEfSe analysis (

Figure 7) further identified that the T4-treated plots contained the highest number of significantly differentiated bacterial and fungal biomarkers, including enrichments of the Chloroflexi phylum and Paucibacter genus. This statistically confirms the uniqueness of the T4 microbial community and demonstrates the progressive shaping of microbial communities along the fertilization gradient. In the RDA analysis of the fungal community, available nitrogen (AN) emerged as the strongest factor influencing fungal community structure. The pathogenic genus Fusarium showed a positive correlation with pH, while its abundance significantly decreased in the T4 group with reduced fertilizer application. This further illustrates that reduced fertilizer application decreases the abundance of pathogenic genera, contributing to a healthier soil ecosystem.

5. Conclusions

This study elucidates the mechanisms through which fertilizer application rates influence Acanthopanax senticosus growth and medicinal quality by modulating interactions between the soil nutrient environment and microbial community. Through comprehensive analysis of soil fertility, microbial diversity, and their correlations, we demonstrate that reduced chemical fertilizer application combined with organic amendments represents an optimal strategy for balancing ecological sustainability and production efficiency in A. senticosus cultivation. This approach reshaped soil microbial diversity, community structure, and functional potential, thereby optimizing nutrient cycling efficiency within the rhizosphere microenvironment. This microbiome-centric soil management strategy not only alleviated the stress of over-fertilization on microbial community stability but also provides novel insights for enhancing medicinal plant quality through rhizosphere engineering. Future research should focus on long-term field experiments to validate the dynamic effects of this fertilization regime on the accumulation of bioactive compounds in A. senticosus roots. Such studies would provide a scientific foundation for precision soil management in medicinal plant cultivation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Zhuolun Li: Writing–review & editing, Writing–original draft, Data cura-tion, Conceptualization. Zhuolun Li: Software, Methodology, Data curation. Xin Sui and Mengsha Li and Zhimin Yu; Writing–review & editing, Writing–original draft; Zhimin Yu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation.

Funding

This research received financial support from Heilongjiang Province Key Scientific Research Project (NO. ZDGG2024ZR01).

Data Availability Statement

A portion of the data is presented in the Supplementary Data Table.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang Zelun. Optimization of Extraction Process and Preliminary Evaluation of Active Components in Cynanchum Stoloniferum [D]. Northeast Forestry University, 2022.

- Li Xiangquan, Wang Honggang, Liu Yanjie, et al. Effects of Nitrogen-Potassium Fertilization on Growth and Active Components of Siberian Ginseng [J]. Forestry Science and Technology, 2024,49(03):21-24+49.

- Chen Yuping, Zheng Hazhang, Zhou Fei, et al. Effects of crop rotation and organic fertilizer on soil microbial populations in coastal gray tidal soil [J]. Zhejiang Agricultural Science, 2020, 61(10): 2159-2162.

- Fan Pengfei, Liu Wen, Ren Tianbao, et al. Effect of biochar-based fertilizer on inorganic nitrogen content of tobacco planting soil under drip irrigation [J]. Journal of Henan Agricultural University, 2020, 54(5): 740-747, 761.

- LUO Longsu, LI Yu, ZHANG Wen'an, et al. Characteristics of maize yield and fertilizer utilization in loamy dryland under long-term fertilization[J]. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2013, 24 (10): 2793-2798.

- JI Jinghong, LI Yuying, LIU Shuangquan, et al. Effects of controlled-release urea application on yield and efficiency and nitrogen utilization of spring corn in Heilongjiang Province [J]. Heilongjiang Agricultural Science, 2016(5):30-33.

- Thapa S, Prasanna R, Ramakrishnan B, et al. Interactive effects of Magnaporthe inoculation and nitrogen doses on the plant enzyme machinery and phyllosphere microbiome of resistant and susceptible rice cultivars[J]. Archives of Microbiology, 2018, 200(9): 1287- 1305.

- Chen H, Song Y, Wang Y, et al. ZnO nanoparticles: improving photosynthesis, shoot development, and phyllosphere microbiome composition in tea plants[J]. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 2024, 22(1): 389.

- Gao Jinhui, Research on the protection and restoration technology of germplasm resources of wild endangered Acanthopanax. Heilongjiang Province, Yichun Branch of Heilongjiang Forestry Academy of Sciences, 2022-12-07.

- Bi Liandong, Lv Ye, Zhang Dan, et al. Problems and analysis of cultivation technology of Sophora japonica in Heilongjiang Province[J]. China Forest By-Products,2024,(03):76-77. [CrossRef]

- Grice EA, Kong HH, et al. (2009). Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. science, 324(5931): 1190-1192.

- GAO J H, HAN J Y, ZHANG H L, et al. Elevational changes in community diversity and similarity analysis of a Acanthopanax senticosus community[J]. Forest Engineering, 2022, 38(4):53-60.

- Liu Shun. Study on the influence of different cultivation conditions on photosynthetic characteristics and growth physiology of Spermophilus spicatus[D]. Jilin Agricultural University, 2011.

- Han Wulong, Zhang Li, Wang Weimin, et al. Impact of reduced chemical fertilizer application with organic fertilizers on microbial diversity and tobacco leaf quality in soil [J/OL]. Shandong Agricultural Science, 1-20 [2025-09-04].

- Řezáčová, V., Czakó, A., Stehlík, M. et al. Organic fertilization improves soil aggregation through increases in abundance of eubacteria and products of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Sci Rep 11, 12548 (2021).

- Shi Y, Niu X, Chen B, Pu S, Ma H, Li P, Feng G and Ma X (2023) Chemical fertilizer reduction combined with organic fertilizer affects the soil microbial community and diversity and yield of cotton. Front. Microbiol. 14:1295722.

- Shanyi Tian, Baijing Zhu, Rui Yin, Mingwei Wang, Yuji Jiang, Chongzhe Zhang, Daming Li, Xiaoyun Chen, Paul Kardol, Manqiang Liu,Organic fertilization promotes crop productivity through changes in soil aggregation,Soil Biology and Biochemistry,Volume 165,2022,108533.

- Qingjie Li, Daqi Zhang, Hongyan Cheng, Lirui Ren, Xi Jin, Wensheng Fang, Dongdong Yan, Yuan Li, Qiuxia Wang, Aocheng Cao,Organic fertilizers activate soil enzyme activities and promote the recovery of soil beneficial microorganisms after dazomet fumigation,Journal of Environmental Management,Volume 309,2022,114666.

- Li Wang, Peina Lu, Shoujiang Feng, Chantal Hamel, Dandi Sun, Kadambot H.M. Siddique, Gary Y. Gan,Strategies to improve soil health by optimizing the plant–soil–microbe–anthropogenic activity nexus,Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment,Volume 359,2024,108750.

- Tiepo, A.N., Constantino, L.V., Madeira, T.B. et al. Plant growth-promoting bacteria improve leaf antioxidant metabolism of drought-stressed Neotropical trees. Planta 251, 83 (2020).

- Gao, Y., Chen, S., Li, Y. et al. Effect of nano-calcium carbonate on morphology, antioxidant enzyme activity and photosynthetic parameters of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 10, 31 (2023).

- Geng, J., Yang, X., Huo, X. et al. Effects of controlled-release urea combined with fulvic acid on soil inorganic nitrogen, leaf senescence and yield of cotton. Sci Rep 10, 17135 (2020).

- Sun, Yp., Yang, Js., Yao, Rj. et al. Biochar and fulvic acid amendments mitigate negative effects of coastal saline soil and improve crop yields in a three year field trial. Sci Rep 10, 8946 (2020).

- Xin Jin, Jinwen Cai, Shuyun Yang, Shoupeng Li, Xujie Shao, Chunmin Fu, Changzhen Li, Yan Deng, Jiaquan Huang, Yunze Ruan, Changjiang Li,Partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic fertilizer and slow-release fertilizer benefits soil microbial diversity and pineapple fruit yield in the tropics,Applied Soil Ecology,Volume 189,2023,104974.

- Wang N, Nan HY, Feng KY. Effects of reduced chemical fertilizer with organic fertilizer application on soil microbial biomass, enzyme activity and cotton yield. The journal of applied ecology,2020.

- Fei Gong, Yijia Sun, Tao Wu, Fei Chen, Bin Liang, Juan Wu,Effects of reducing nitrogen application and adding straw on N2O emission and soil nitrogen leaching of tomato in greenhouse,Chemosphere,Volume 301,2022,134549.

- SONG Yi, CHEN Hanghang, CUI Xin, et al. Potassium nutrient status-mediated leaf growth of oilseed rape and its effect on interleaf microorganisms[J]. Journal of Botany, 2024, 59: 54-65.

- Wu D, Ma X, Meng Y, et al. Impact of nitrogen application and crop stage on epiphytic microbial communities on silage maize leaf surfaces[J]. PeerJ, 2023, 11: e16386.

- Bao Shidan. Soil agrochemical analysis [M]. Beijing: China Agricultural Press, 2000.

- Amir, A. , Mcdonald, D., Navas-Molina Jose, A., Kopylova, E., Morton James, T., Zech Xu, Z., et al. (2017). Deblur rapidly resolves single-nucleotide community sequence patterns. mSystems:2.

- Kim, M. , and Chun, J. (2014). "Chapter 4 - 16S rRNA gene-based identification of Bacteria and Archaea using the EzTaxon server" in Methods in microbiology. eds. M. Goodfellow, I. Sutcliffe and J. Chun (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 61-74.

- Peng X R, Wang S,Zeng Z H, Wang J L, Wang Y, Feng R. Qin M C. Zhao J K, Lu M, Zhang Y Q. Effects of par-tial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic fertilizer on the yield and fruit qualities of red pomelo and soil properties [J]. Soil and Fertilizer Sciences in China, 2023(11):110-119.

- Zhang B Y, Chen T L, Wang B. Effects of long-term uses of chemical fertilizers on soil quality [J]. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, 2010. 26(11):182-187.

- Ma J Y, Chen J R, Li K J, Cao C Y, Zheng C L. The effect of chemical and organic straw fertilization on the content and properties of soil organic matter [J]. Journal of Hebei Agricultural Sciences,2006,10(4),44-47.

- Zhang Yan, Deng Ruirui, Zhang Chun, et al. Effects of different substitution ratios of organic fertilizers on strawberry quality and soil microbial community[J/OL]. Journal of Agricultural Resources and Environment,1-16[2025-06-09].

- ZHANG Zemao, WU Lei, GAO Tianyu, et al. Integrated analysis of the effects of chemical fertilizers and organic materials application on organic carbon fractions in northeastern black soil[J/OL]. Environmental Science,1-17[2025-07-09].

- REN Tao-yi, HUANG Xue-ru, SUN Hao-lin, et al. Comparison of microbial response to exogenous carbon and nitrogen additions in black soil under no-tillage and organic and inorganic fertilizers with straw mulch[J/OL]. Journal of Microbiology,1-18[2025-06-09].

- LIU Xi, HUANG Hongyuan, YI Shengchang, et al. Progress of research on the interaction between invasive plants and mycorrhizal fungi and its effect on soil nitrogen cycling[J]. Plant Research,2025,45(03):371-385.

- Amato K R, Yeoman C J, Kent A, et al. Habitat degradation impacts black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) gastrointestinal microbiomes[J]. The ISME journal, 2013, 7(7): 1344-1353.

- Nie San'an, Zhao Lixia, Wang Yi, et al. Effects of long-term fertilization on the structure and diversity of soil microbial communities in yellow mud field [J]. Research on Modernization of Agriculture, 2018, 39 (4): 689-699.

- YANG Ling, ZHANG Yi, ZHONG Junjie, et al. Effects of different acid regulators on the microbial community of red soil of planted corn[J]. Journal of Agricultural Environmental Science,2024,43(03):609-616.

- Ren C J, Zhang W, Zhong Z K, el al. Differentinl responses of soil microbial biomass, diversity, and compositions to altitudinal gradients depend on plant and soil characteristics[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018. 610/611: 750 - 758.

- LIN Lianghua, ZHANG Hengrui, YU Haoxiang, et al. Study on the abrogation effect of calcium cyanamide on the barriers of Rhizoma Coptidis[J/OL]. Chinese Journal of Experimental Formulary,1-15[2025-06-09].

- Redouane, El Mahdi,Núñez, Andrés,Achouak, Wafa, et al. Microcystin influence on soil-plant microbiota: Unraveling microbiota modulations and Microcystin influence on soil-plant microbiota: Unraveling microbiota modulations and assembly processes in the rhizosphere of Vicia faba[J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2024, 918: 170634.

- Liu Ying. Effects of microbial fungicides on yield quality and soil properties of nodular kale[D]. Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University,2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Chen Yuzhen, Wu Zidan, et al. Effects of fertilizer reduction on soil fungal community structure and functional groups in tea plantations [J]. Tea Journal, 2021, 62(4): 170-178.

- Ling N, Zhang W, Tan S, et al. Effect of the nursery application of bioorganic fertilizer on spatial distribution of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum and its antagonistic bacterium in tea plantations [J]. and its antagonistic bacterium in the rhizosphere of watermelon[J] .Applied Soil Ecology, 2021, 59: 13-19.

- YAO C X, LI X J,LI Q, QIU R, BAI J K. LIU C, CHEN Y G. KANG Y B, LI S J. Screening and identification of antagonistic fungal against tobacco Fusarium oxysporum and its growth promotion effect [J]. Chinese Journal of Biological Control 2021, 37(5): 1066-1072.

- Cheeke T E, Phillips R P, Brzostek E R, et al. Dominant mycorrhizal association of trees alters carbon and nutrient cycling by selecting for microbial groups with distinct enzyme function [J]. New Phytologist, 2017, 214(1):432-442.

- Kong J Q, He Z B, Chen L F, et al. Efficiency of biochar, nitrogen addition, and microbial agent amendments in remediation of soil properties and microbial community in Qilian Mountainsmine soils [J].Ecology and Evolution, 2021, 11(14): 9318-9331.

- WU Chunyi,ROSHASHA,YANG Ting,et al. Effects of nitrogen reduction with microbial fungicides on yield and soil microbial diversity of roasted tobacco[J]. Guangdong Agricultural Science,2023,50(08):52-65.

- Ding, J. N. . Effects of chemical fertilizer reduction and organic fertilizer application on soil maturation in reclaimed coal mining subsidence area[D]. Shanxi Agricultural University,2022.

- WANG Zisong, YANG Zhengli, ZENG Ziyun, et al. Effects of chemical fertilizer reduction and organic fertilizer application on inter-root microbial diversity and enzyme activity of mango[J]. Jiangsu Agricultural Science,2025,53(02):240-247.

- Sun ZJ,Zhong GX,Zhang SB,et al. Effects of chemical fertilizer reduction and organic fertilizer application on the physicochemical properties and microbial community structure of tobacco planting soil[J]. North China Journal of Agriculture,2024,39(03):146-158.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).