Submitted:

05 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

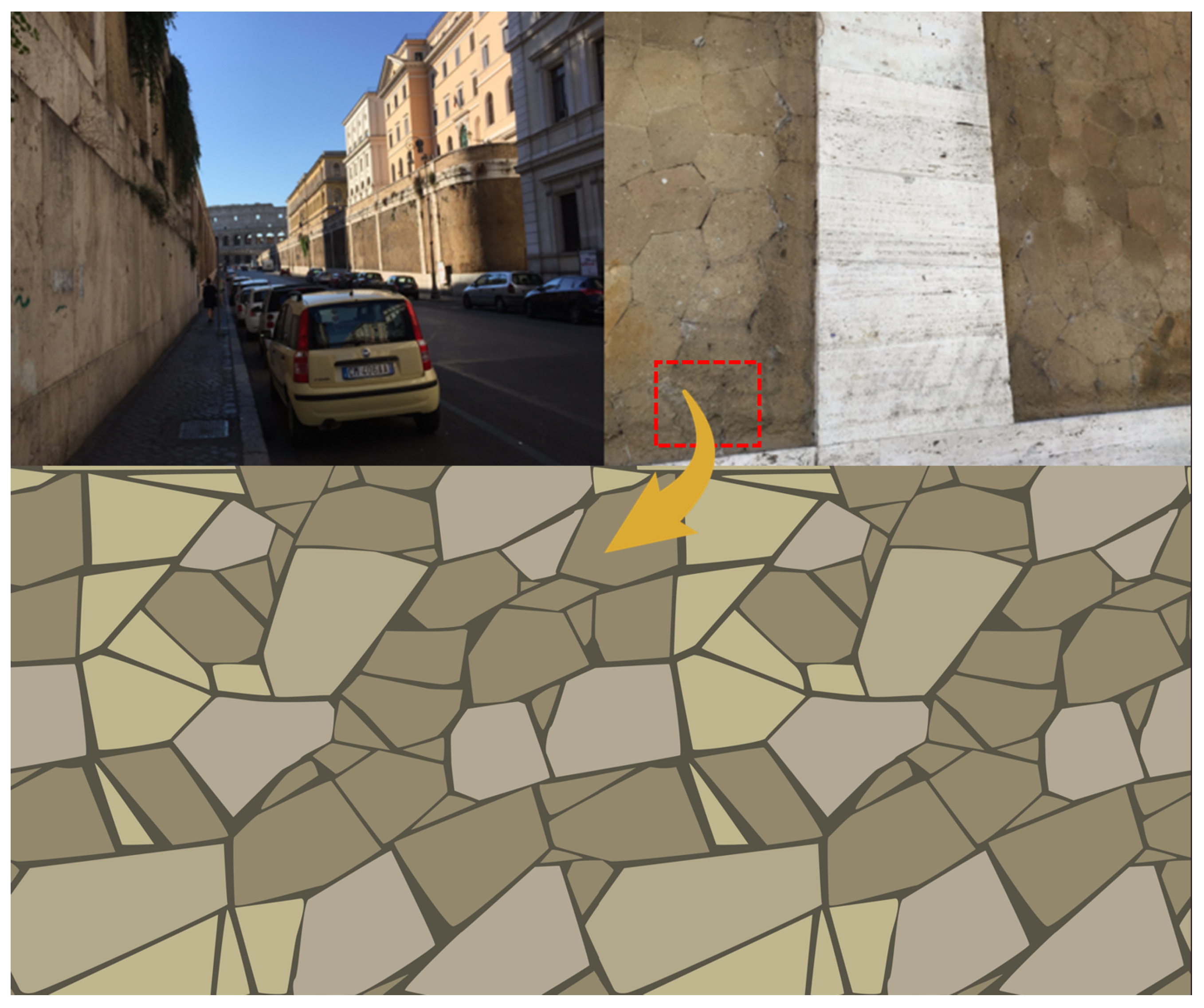

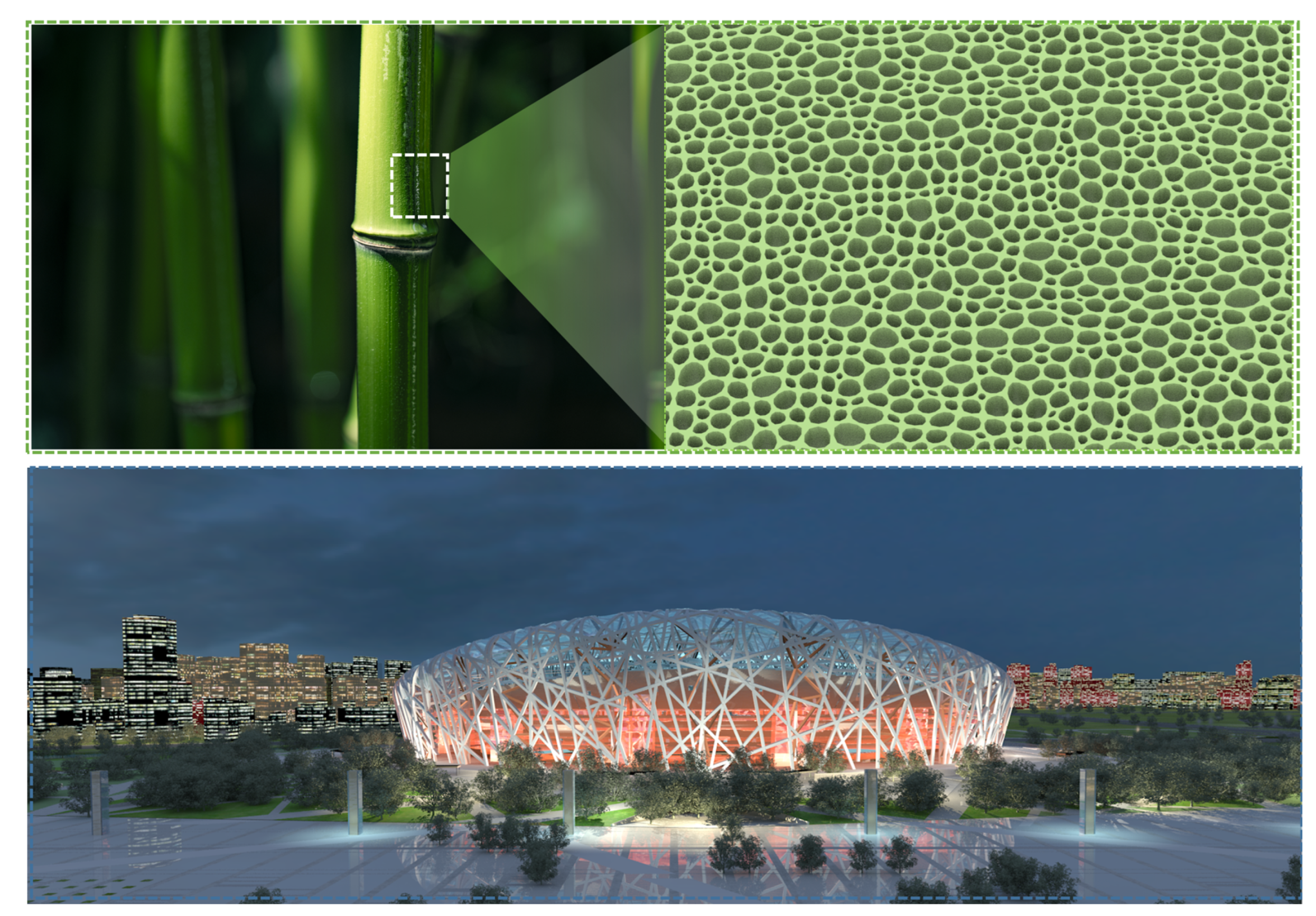

1. Introduction

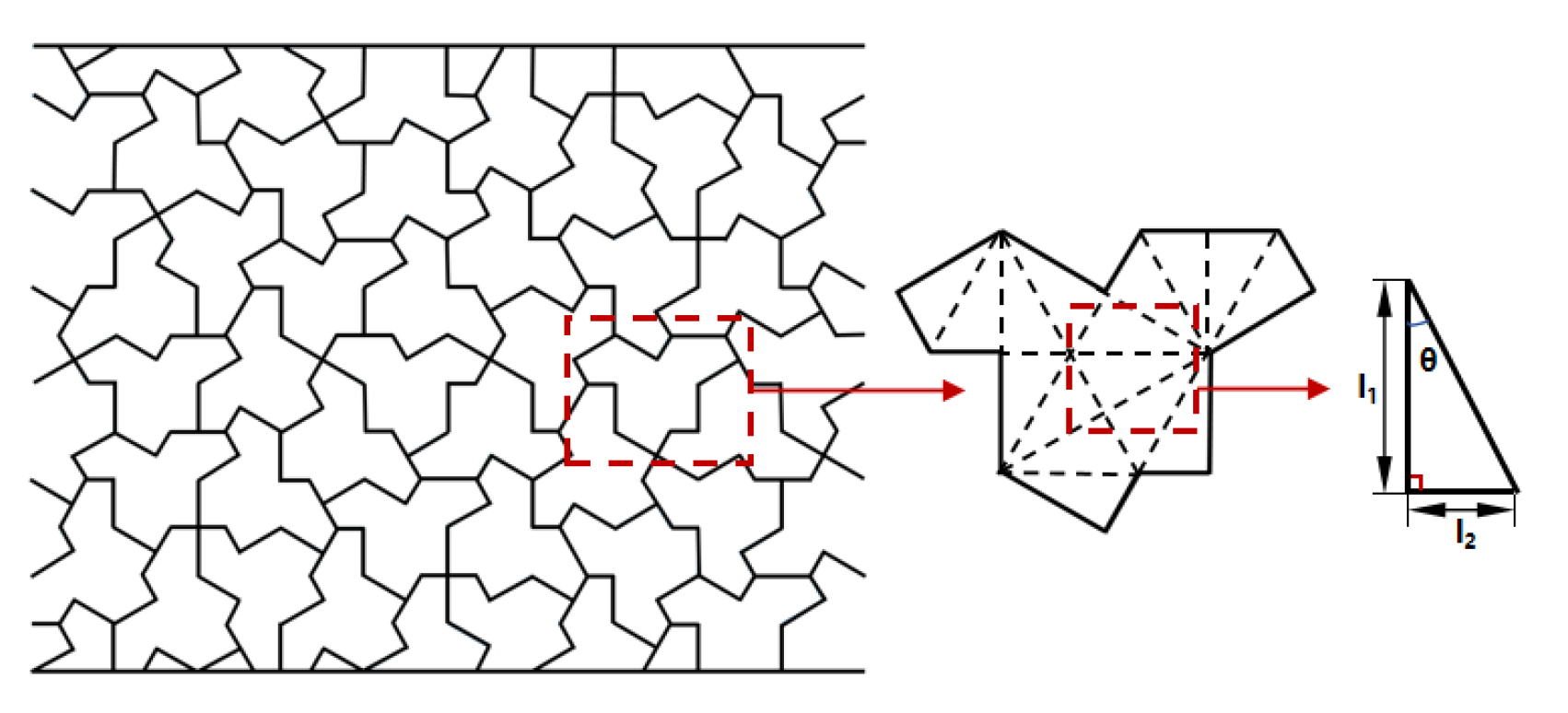

2. Entropy of Topological Disorder Mtamaterials/Strucures

2.1. Entropy Definition of Topological Disorder Metamaterials/Strucures

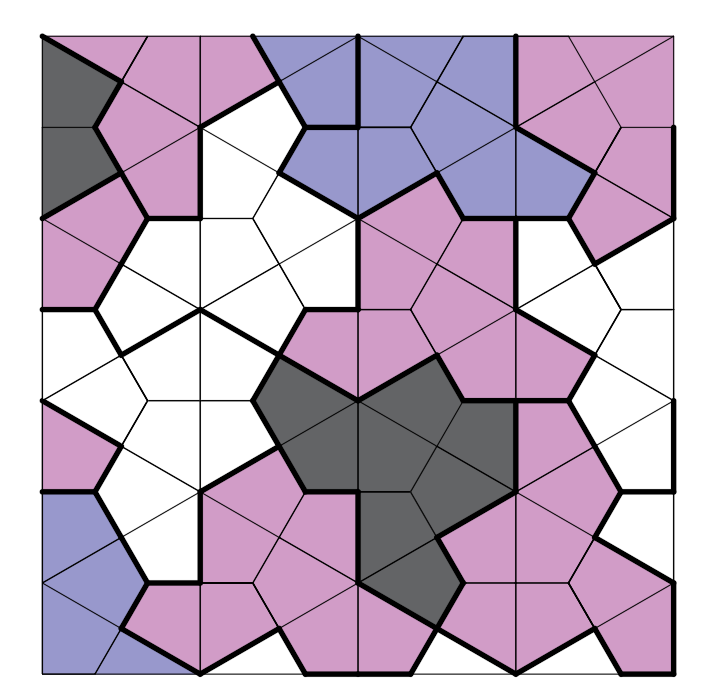

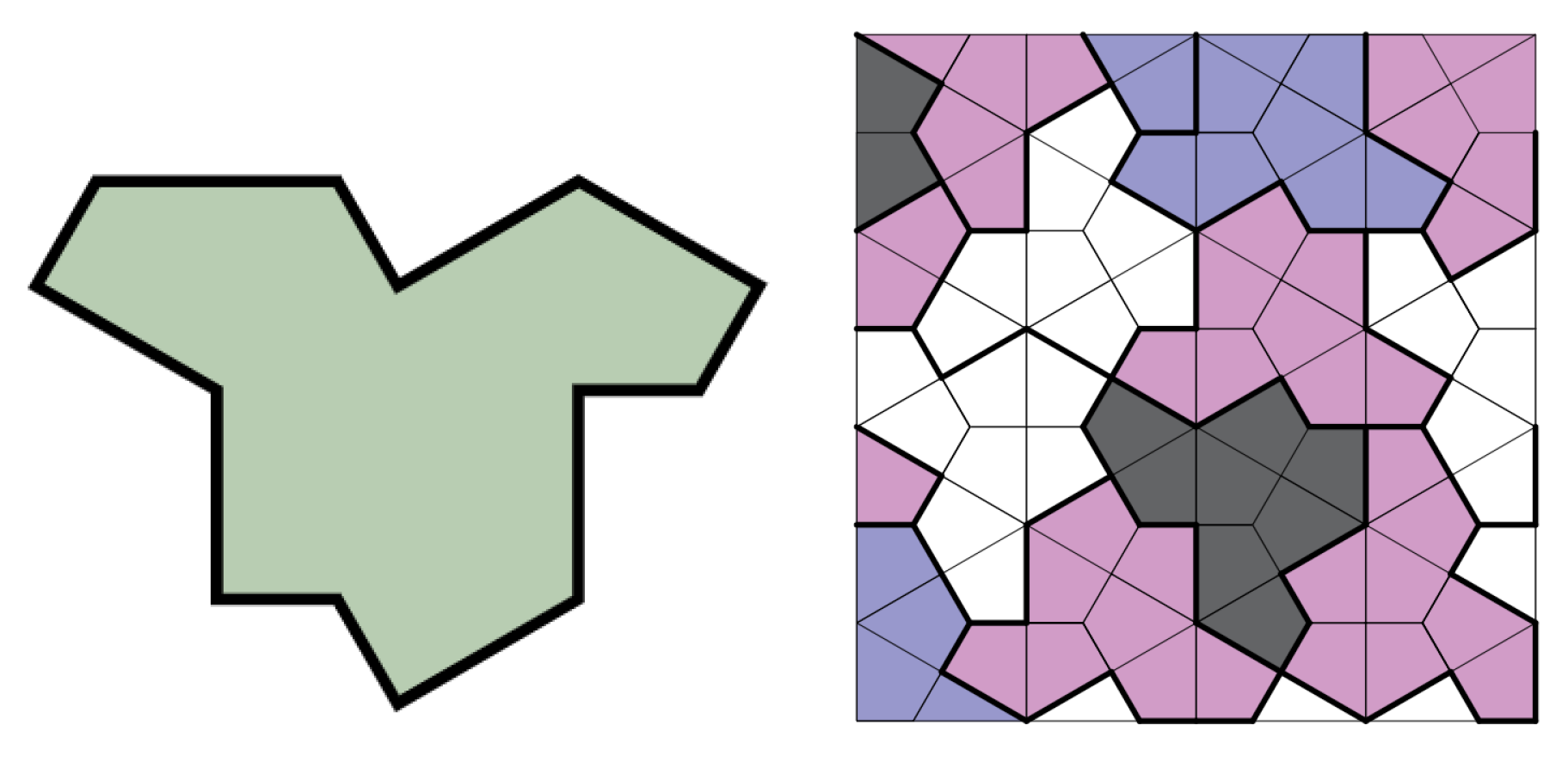

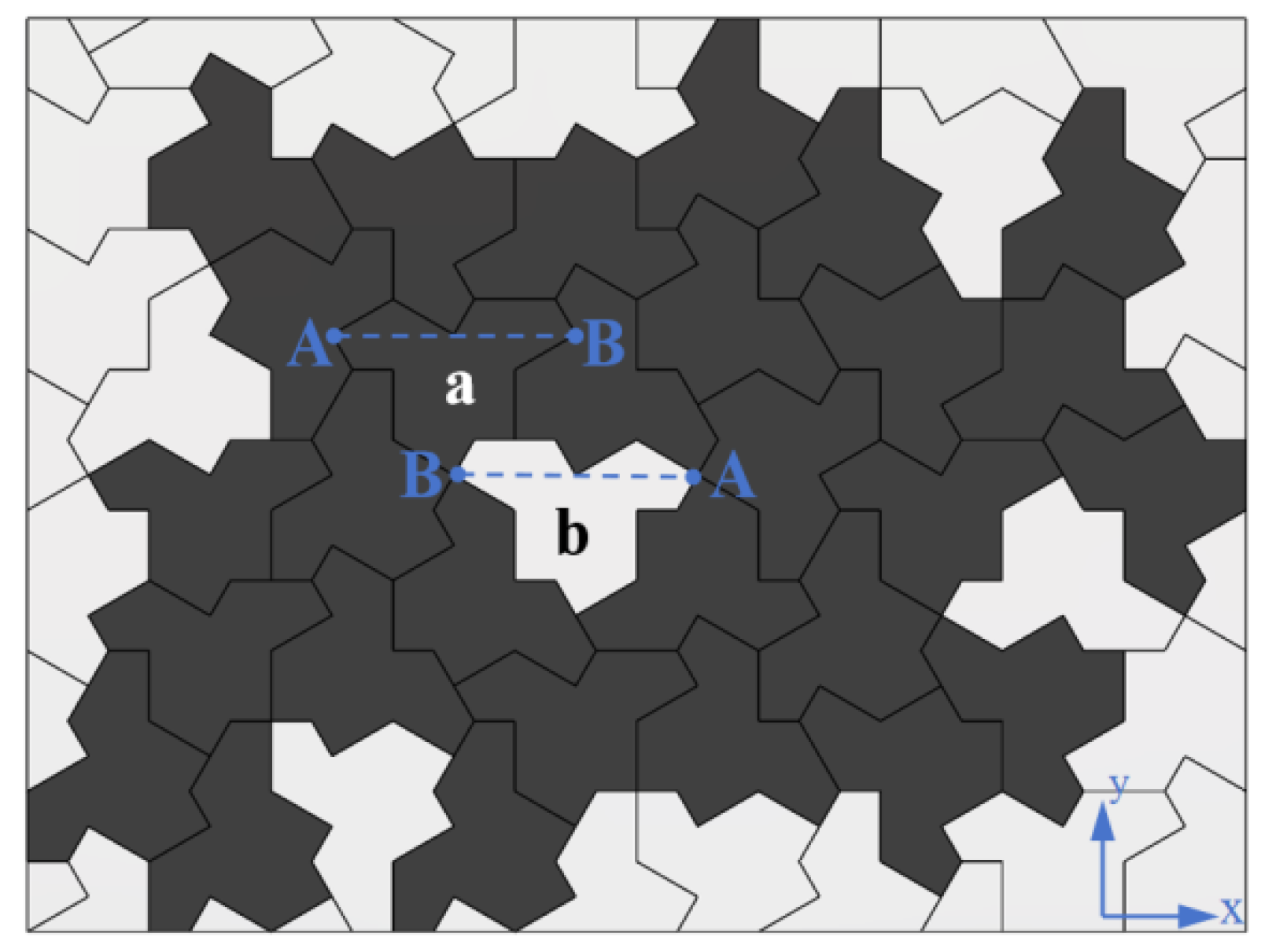

2.2. Entropy of the Hat Honeycomb Metamaterial

3. Sample Manufacturing and Mechanical Testing

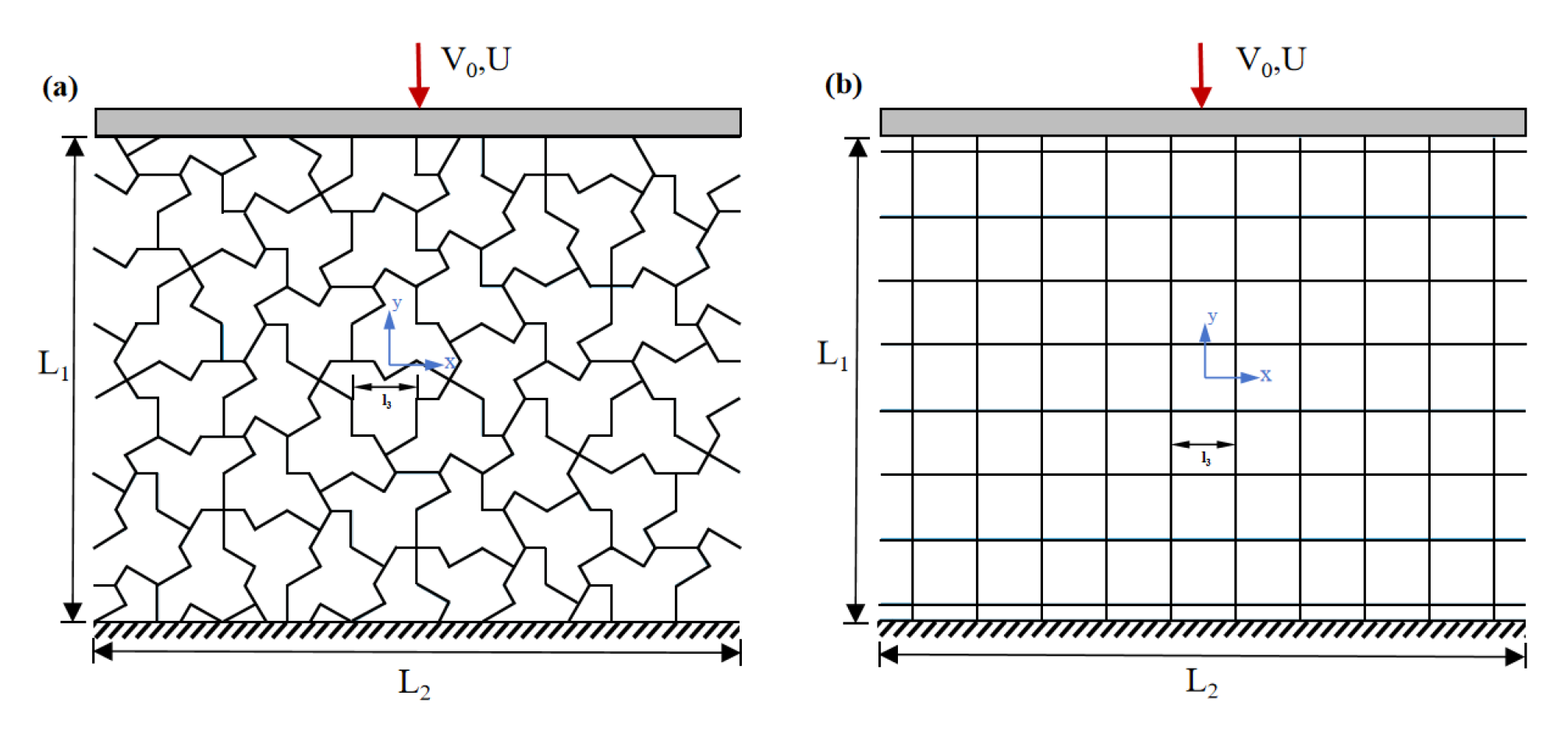

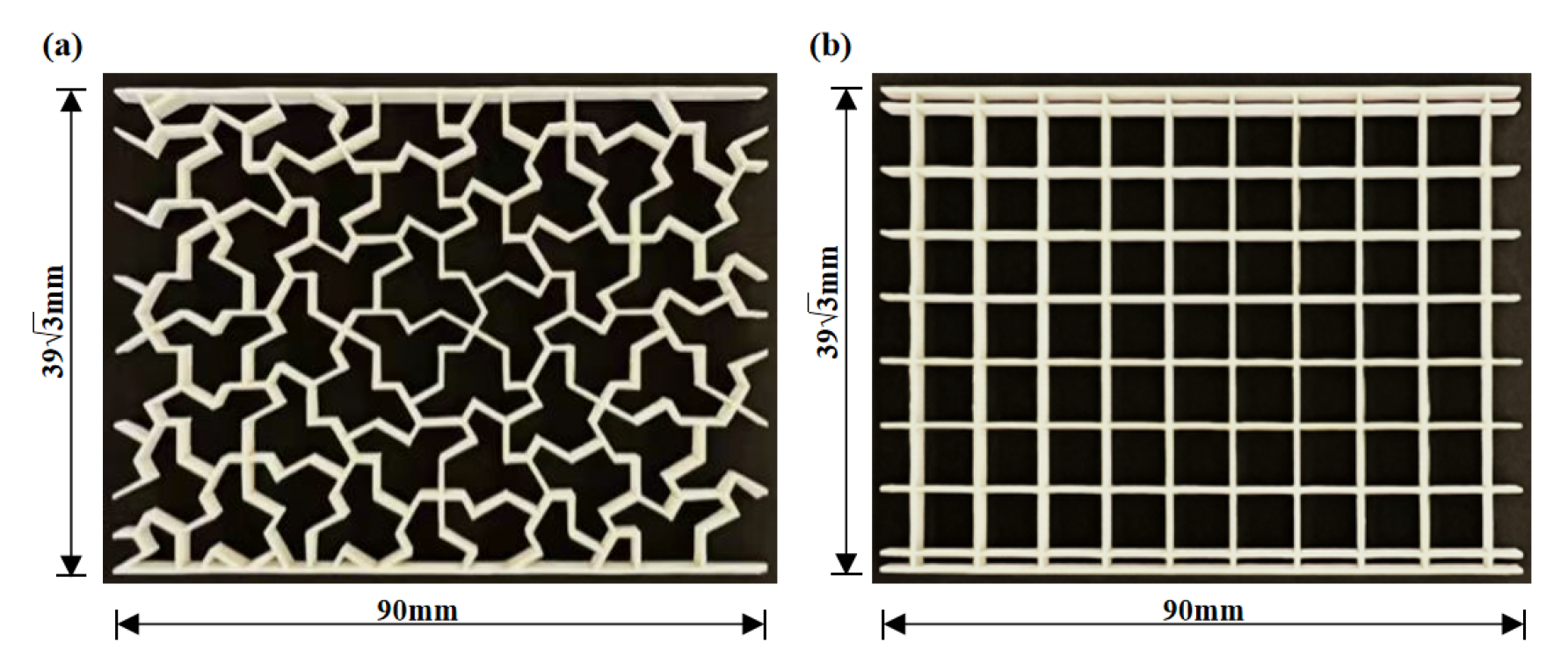

3.1. Structural Design

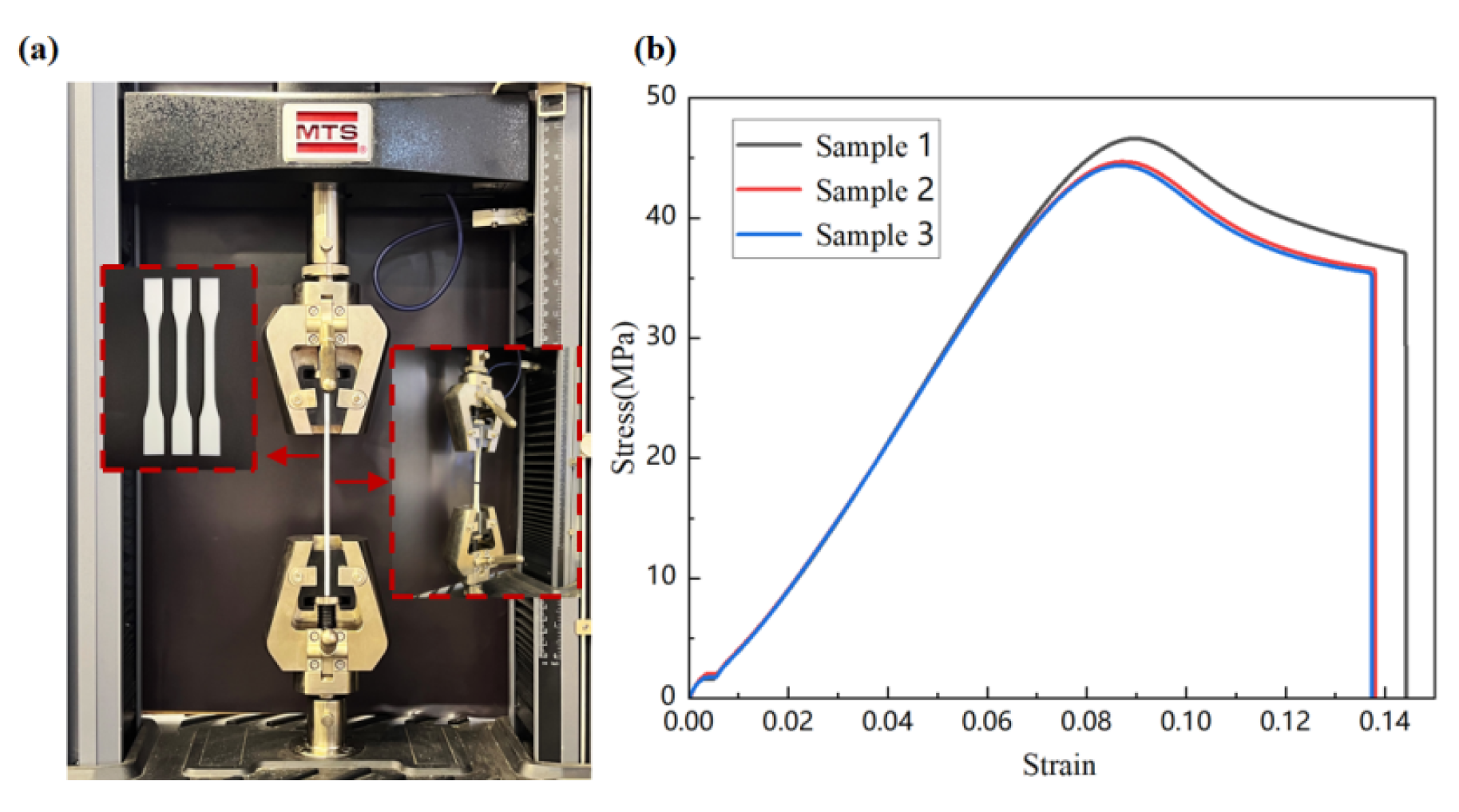

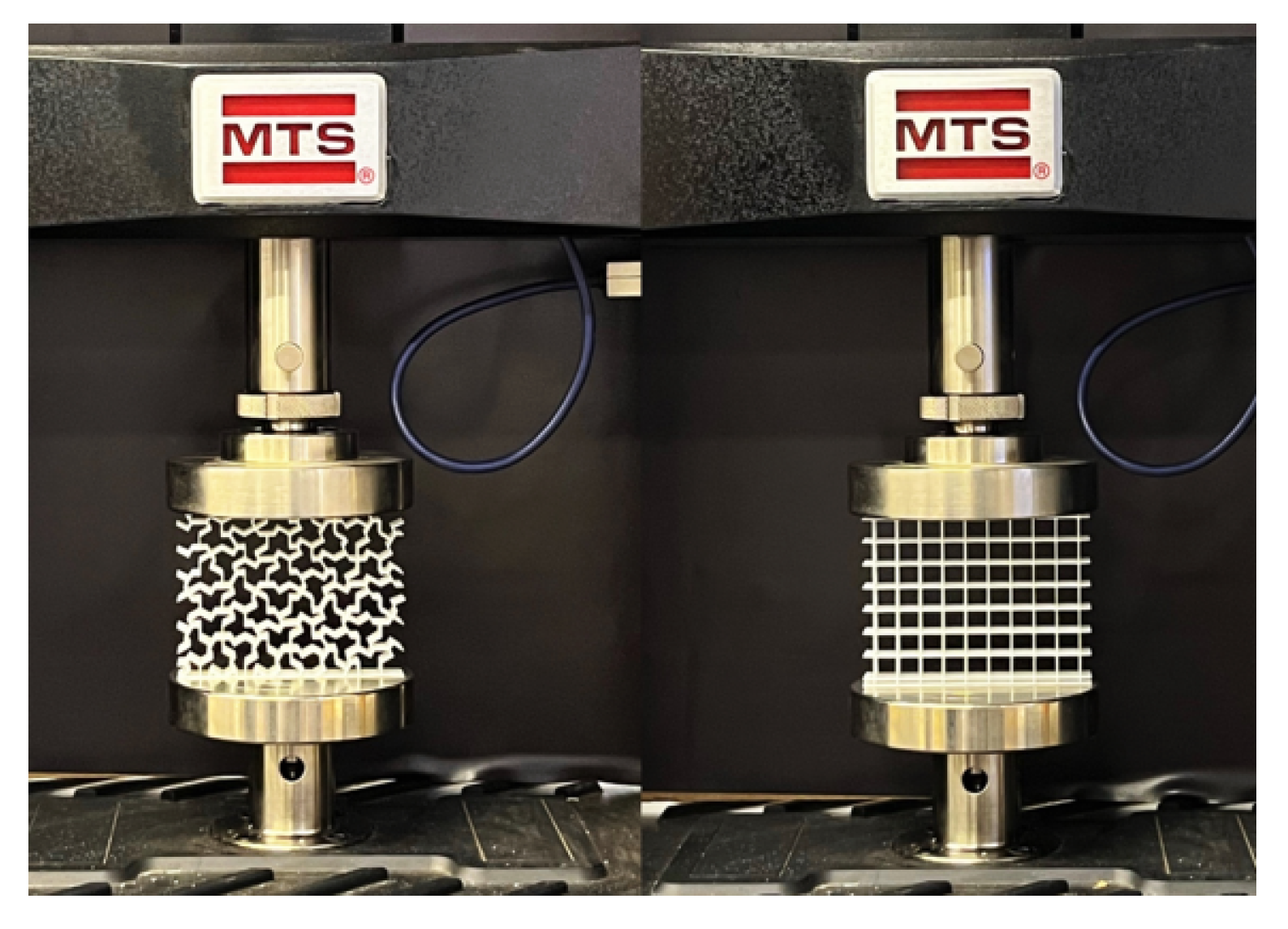

3.2. Sample Manufacturing

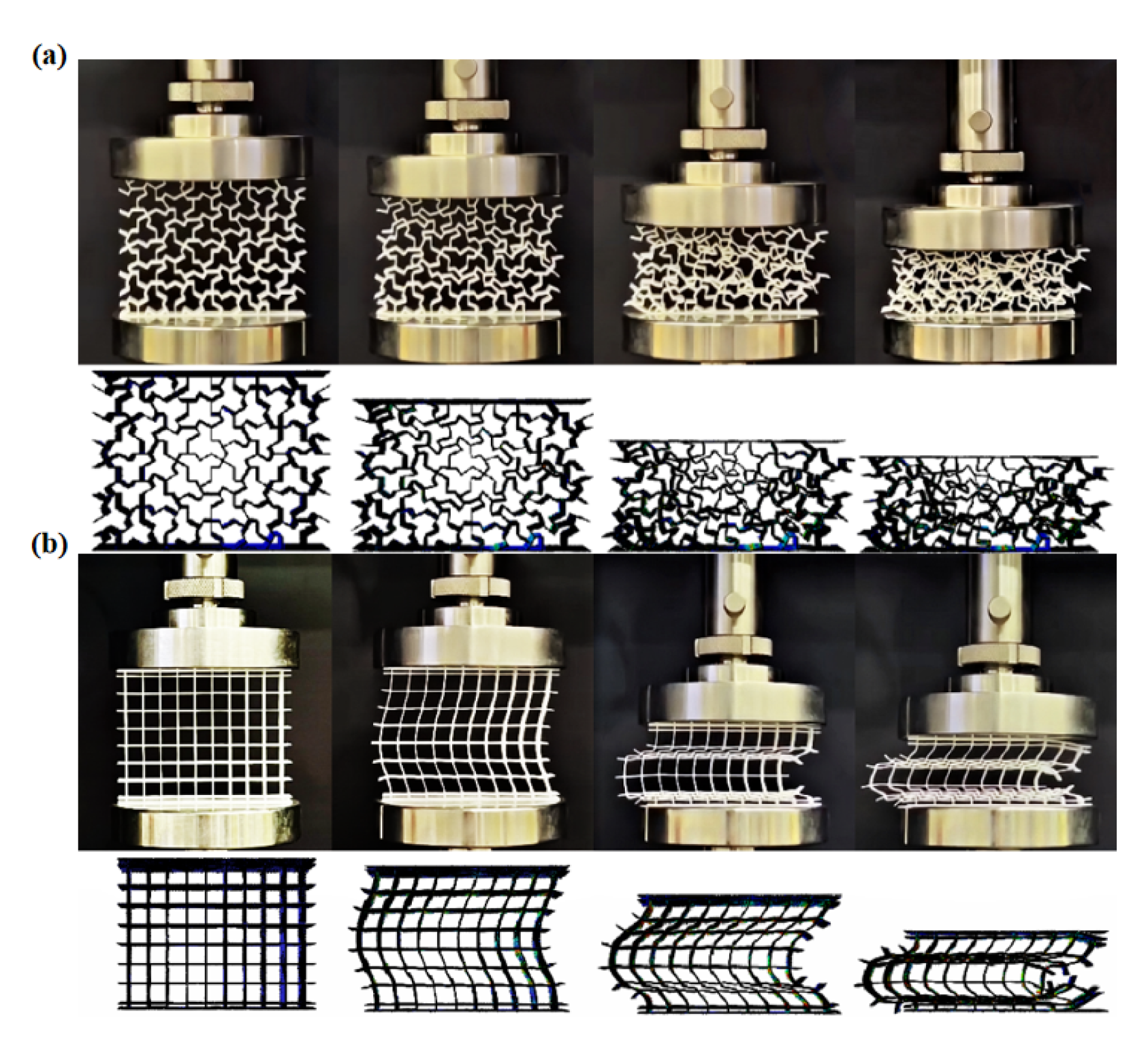

3.3. Mechanical Testing

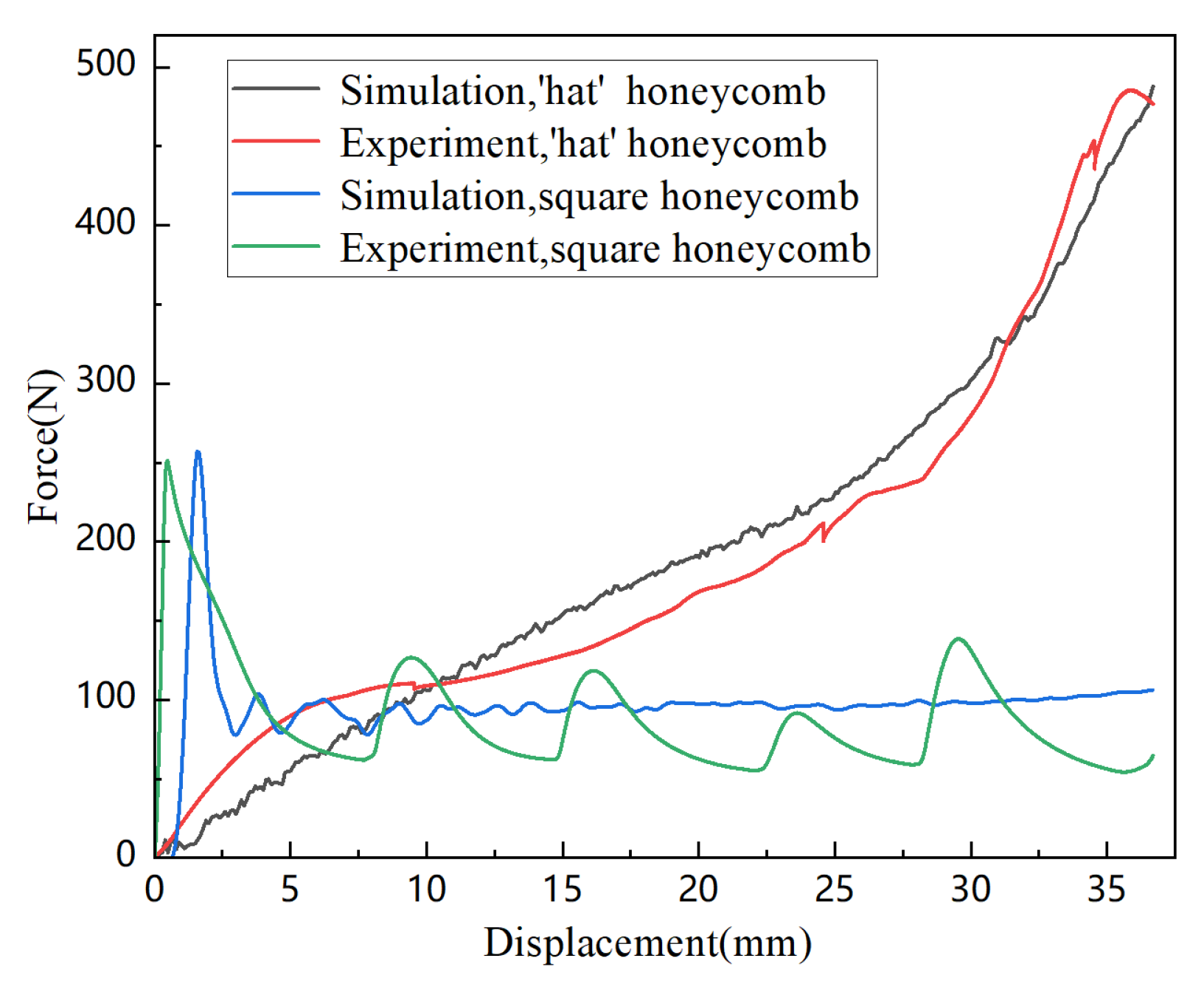

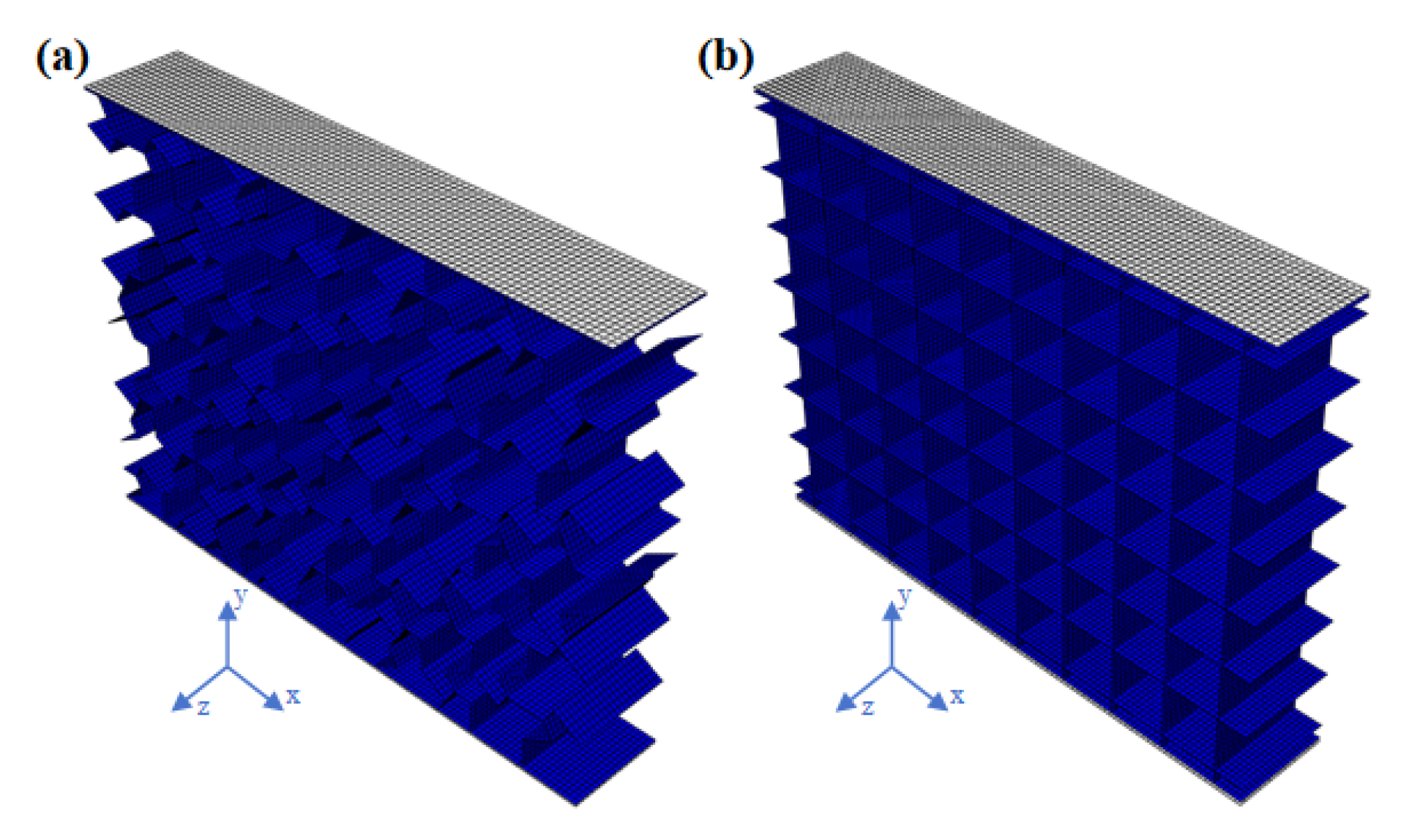

4. Numerical Simulation Compared with Experiment

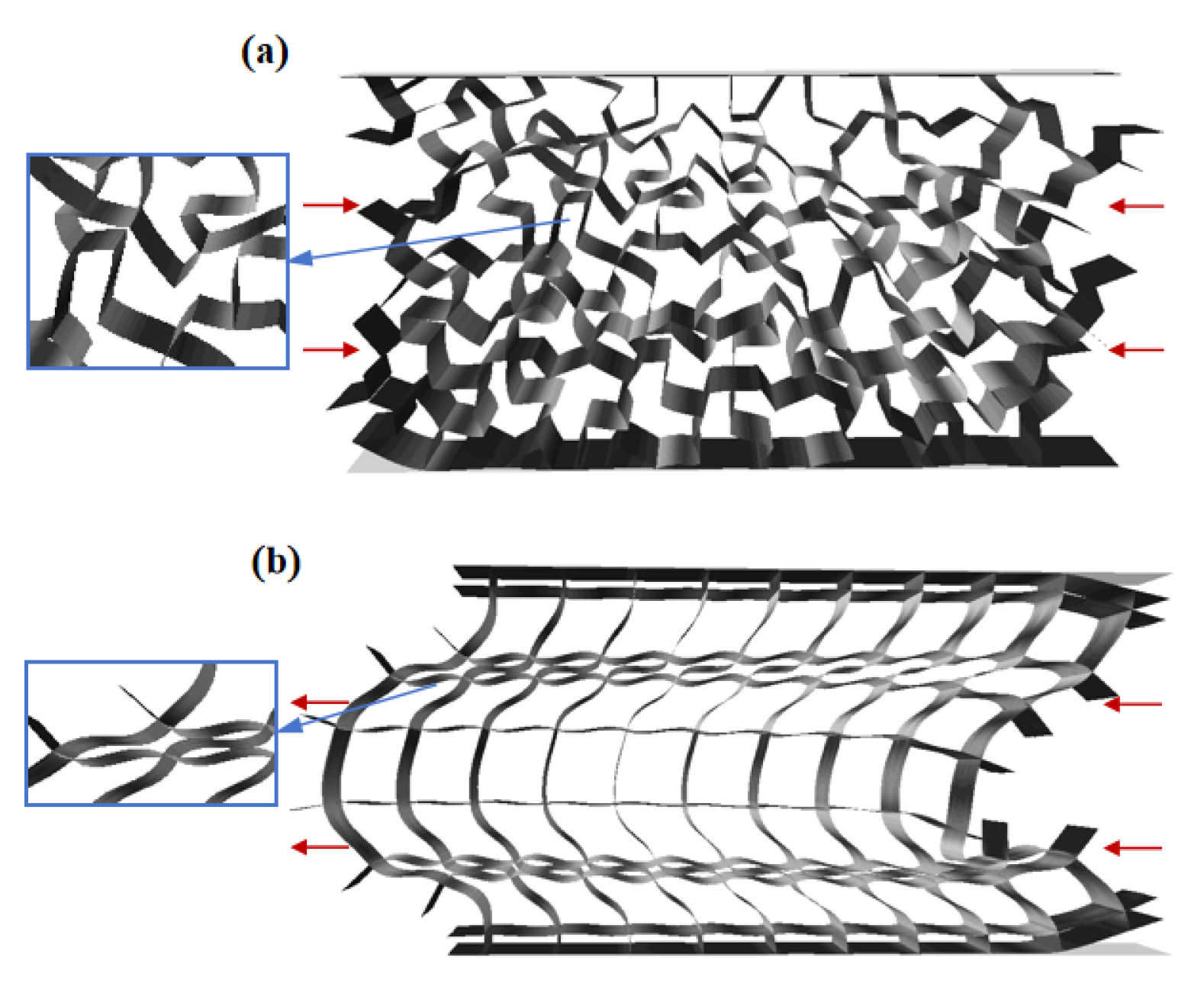

4.1. Compression Deformation Characteristics and Mechanical Properties

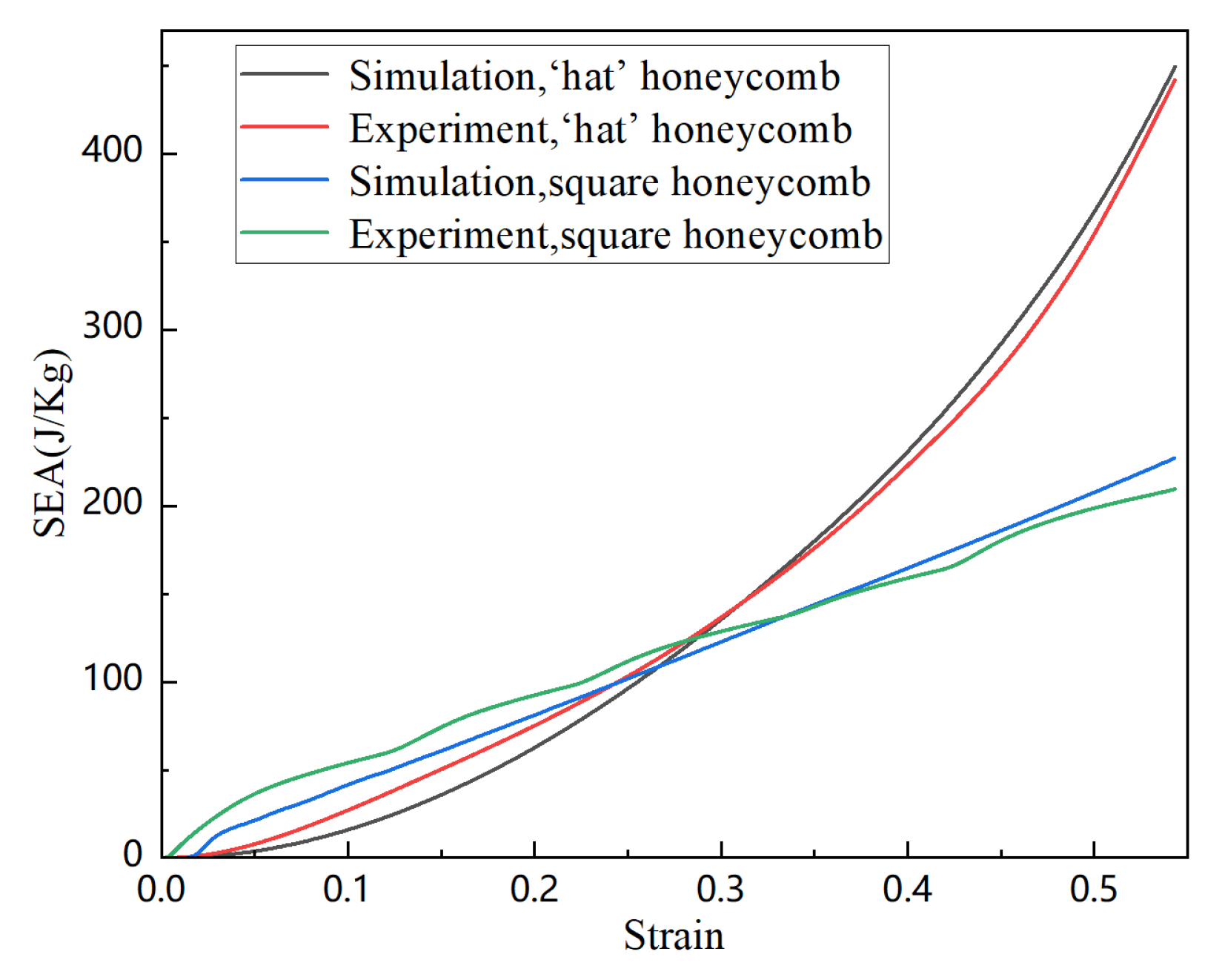

4.2. Absorption Performance Analysis

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Conflicts of Interest

Availability of data

References

- E. Conover, Mathematicians have finally discovered an elusive ’einstein’ tile, Science News, April 24, 2023.

- Smith, D., Myers, J. S., Kaplan, C. S. Goodman-Strauss, C. An aperiodic monotile, arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10798 (2023). [CrossRef]

- C. S. Kaplan, Private commumication, 21 June, 2023.

- D. Shechtman, et al. Metallic phase with long-range orientational order and no translational symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 1951 (1984). [CrossRef]

- I. Georgescu, 50 years of Penrose tilings, Nat Rev Phys 6, 408 (2024). [CrossRef]

- K. Bertoldi, V. Vitelli, J. Christensen & M. van Hecke, Flexible mechanical metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17066 (2017). [CrossRef]

- M. Ashby, The properties of foams and lattices. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 364, 15-30 (2006). [CrossRef]

- R. Lakes, Foam structures with a negative Poisson’s ratio. Science 235, 1038, C1040 (1987). [CrossRef]

- M. Hanifpour, C.F. Petersen, M.J. Alava & S. Zapperi, Mechanics of disordered auxetic metamaterials. Eur. Phys. J. B 91, 271 (2018). [CrossRef]

- M. Zaiser and S. Zapperi, Disordered mechanical metamaterials, Nat Rev Phys 5, 679-688 (2023). [CrossRef]

- D. Tüzes, P.D. Ispanovity & M. Zaiser, Disorder is good for you: the influence of local disorder on strain localization and ductility of strain softening materials, Materials Today, Volume 73, March/April 2024.

- S. Bonfanti, R. Guerra, F. Font-Clos, D. Rayneau-Kirkhope & S. Zapperi, Automatic design of mechanical metamaterial actuators. Nat. Commun. 11, 4162 (2020). [CrossRef]

- K. Liu, R. Sun, & C. Daraio, Growth rules for irregular architected materials with programmable properties. Science 377, 975-981 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Q.W. Li, B.H. Sun, Optimization of a lattice structure inspired by glass sponge. Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, 18(1): 016005 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Q.W. Li, B.H. Sun, Numerical analysis of low-speed impact response of sandwich panels with bio-inspired diagonal-enhanced square honeycomb core. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 173, 104430 (2023). [CrossRef]

- F. Wu and B.H. Sun, Study on functional mechanical performance of array structures inspired by cuttlebone. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 136, 105459 (2022). [CrossRef]

- X.L. Guo and B.H. Sun, Detachable connection mechanics of thin-walled cylindrical snap fit docking. Extreme Mechanics Letters, 67, 102122 (2024). [CrossRef]

- X.L. Guo and B.H. Sun, Mechanics of a thin-walled segmented torus snap fit. Thin-Walled Structures, 198, 111676 (2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Wei and B.H. Sun, Bioinspiration: Pull-Out Mechanical Properties of the Jigsaw Connection of Diabolical Ironclad Beetle’s Elytra, Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 36, 86, C94 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Wei and B.H. Sun, Study on the mechanical properties of cylindrical mechanical metamaterials with biomimetic honeycomb units of the diabolical ironclad beetle, Extreme Mechanics Letters, 67 102127 (2024). [CrossRef]

- D.J. Clarke, F. Carter, I. Jowers, R.J. Moat, An isotropic zero Poisson’s ratio metamaterial based on the aperiodic hat monotile, Applied Materials Today, 35 101959 (2023). [CrossRef]

- R.J. Moat et al., A class of aperiodic honeycombs with tuneable mechanical properties, Aplied Materials Today, 37 102127 (2024). [CrossRef]

- X.X. Wang, et al. Unprecedented Strength Enhancement Observed in Interpenetrating Phase Composites of Aperiodic Lattice Metamaterials, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2406890 2024. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Naji and R.K. Abu Al-Rub, study the effective elastic properties of novel aperiodic monotile-based lattice metamaterials, Materials & Design, 244 113102(2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Jung, A.L. Chen, G.X. Gu, Aperiodicity is all you need: Aperiodic monotiles for high-performance composites. Materials Today. 73, 1-8 (2024). [CrossRef]

- B.H. Sun, High-entropy structural mechanics, Lect. 25, a series seminar of Inst. of Mechanics and Technology, Xi’an Uni. of Architecture and Technology, 26 Oct. 2023. https://imt.xauat.edu.cn/info/1008/3763.htm.

- B.H. Sun, Thermodynamics and high-entropy structural mechanics, Lect. 27, a series seminar of Inst. of Mechanics and Technology, Xi’an Uni. of Architecture and Technology, 15 Nov. 2023. https://imt.xauat.edu.cn/info/1008/3801.htm.

- C.E. Shannon, A mathematical theory of communication, Bell Syst. Tech. J., vol. 27, 379-423, 623-656, July-Oct. 1948.

| Angle | ||||||||

| N | K | |||||||

| type-a | 5 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 29 | 6 |

| type-b | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).