Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

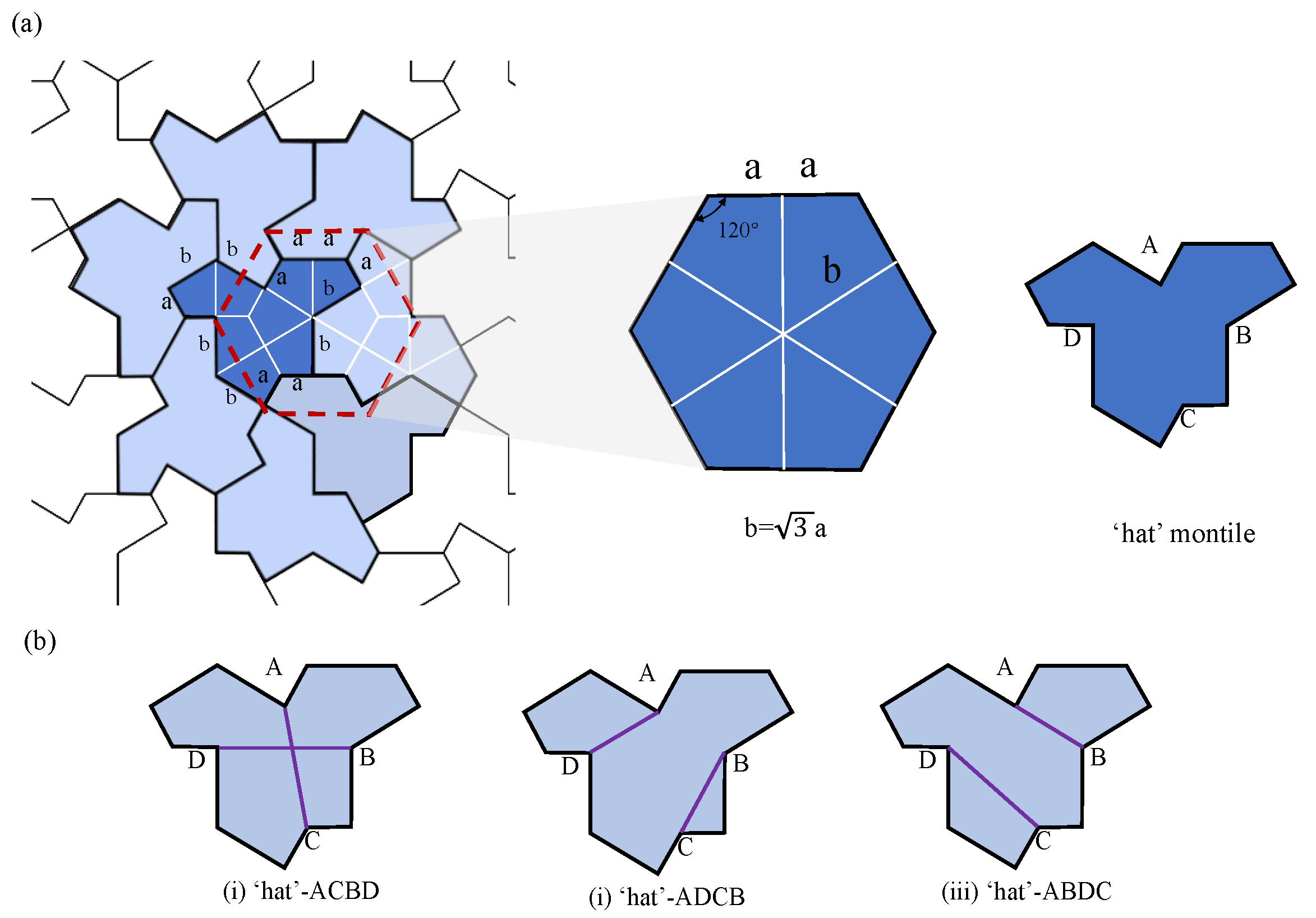

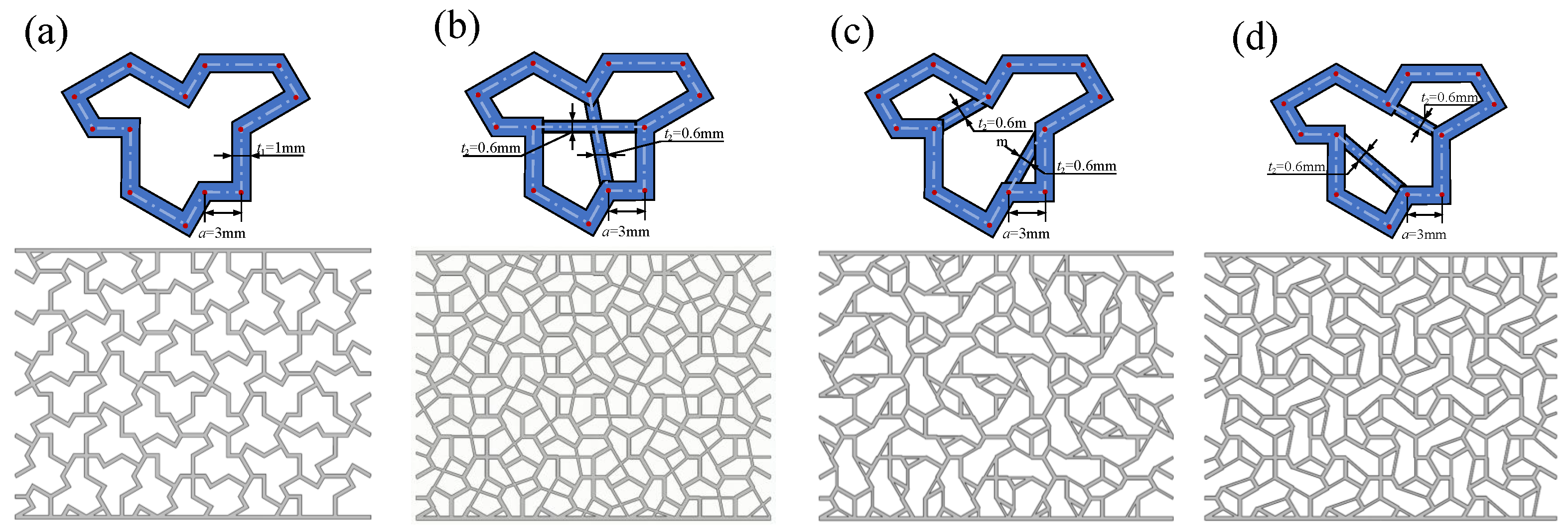

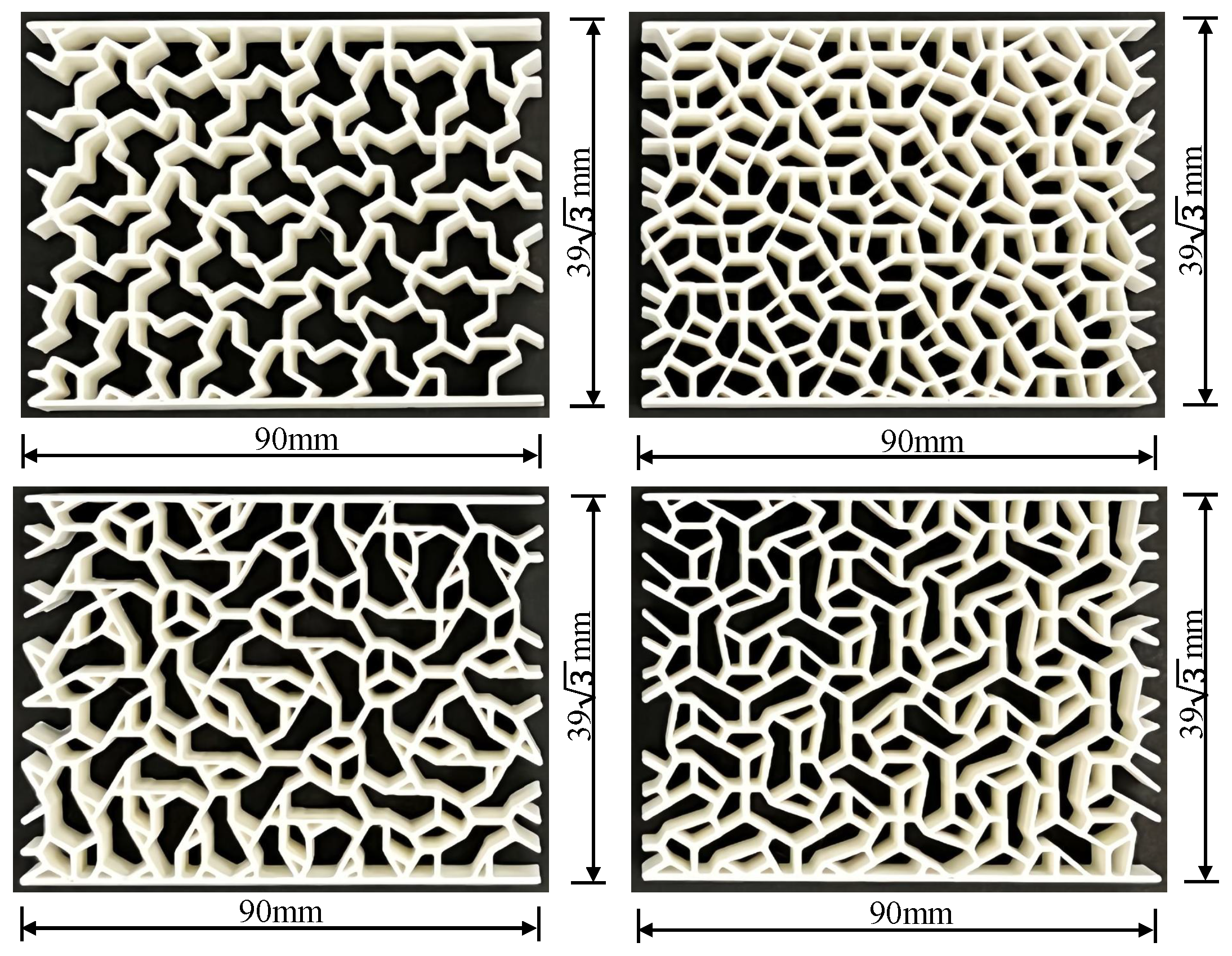

2. Design and Manufacturing

3. Experimental

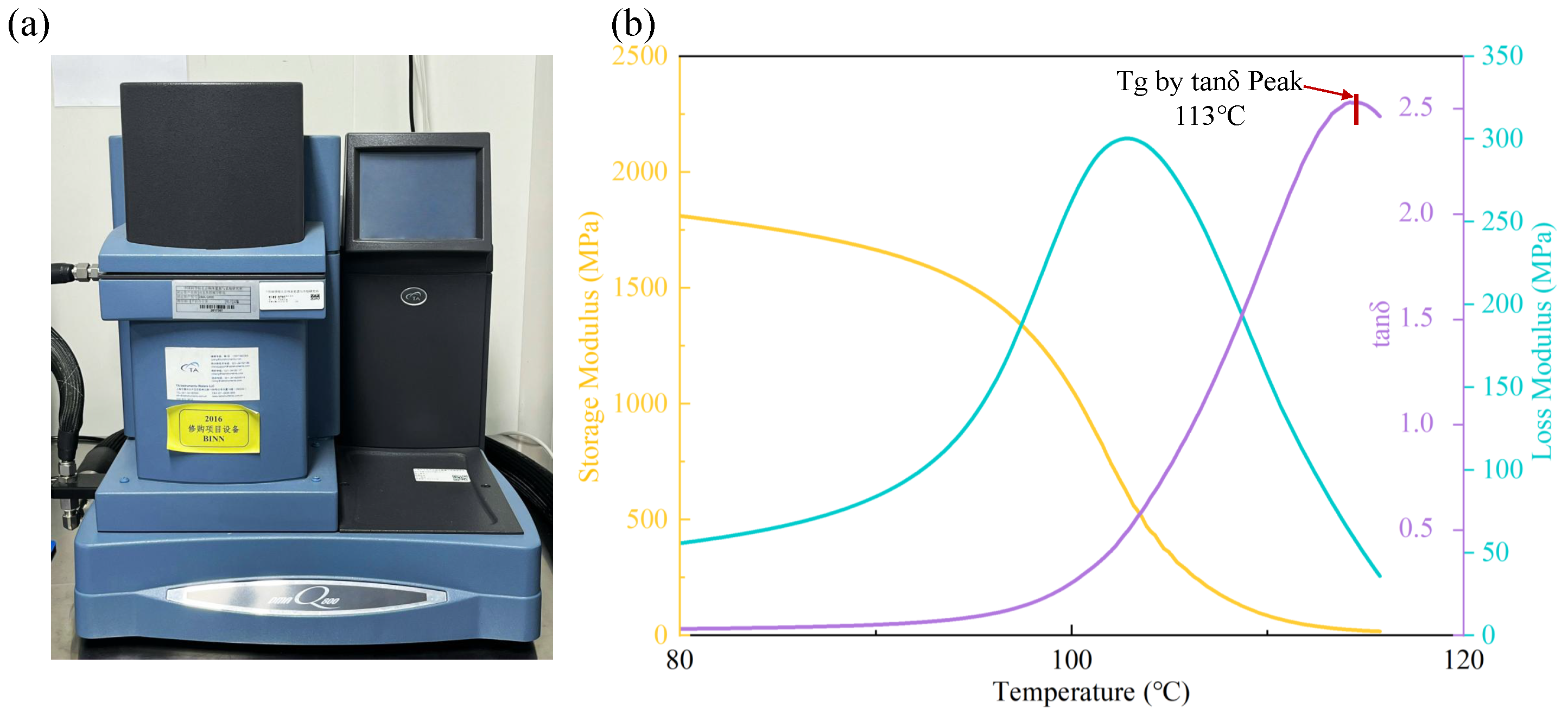

3.1. Material Characterization

3.2. Compression Test

4. Numerical Simulation

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Compressive Mechanical Properties

5.1.1. Quasi-Static Compressive Mechanical Properties at Room Temperature

5.1.2. Quasi-Static Compressive Mechanical Properties at Variable Temperatures

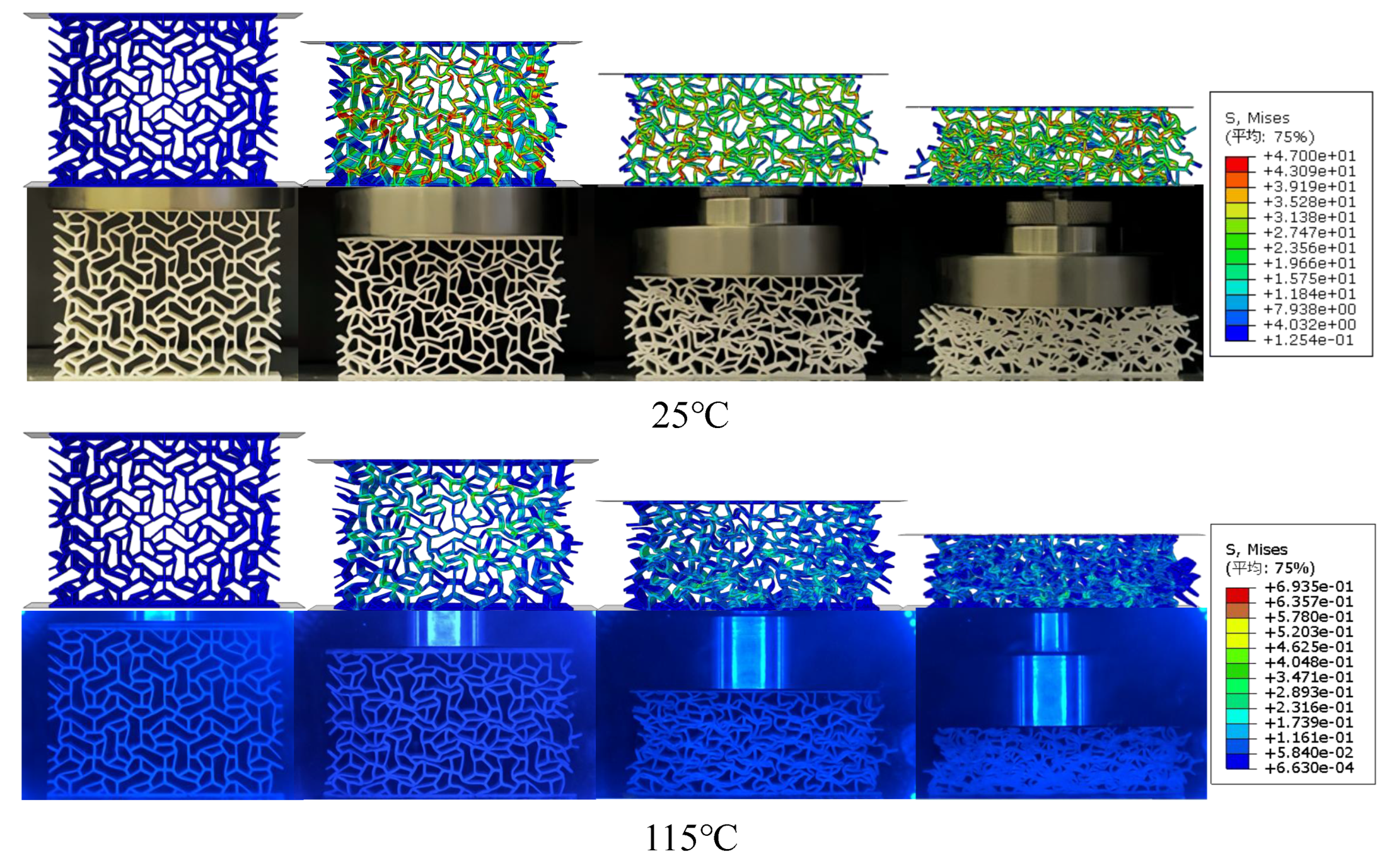

5.2. Compressive Deformation Characteristics

5.2.1. Macrostructural Compressive Deformation Characteristics

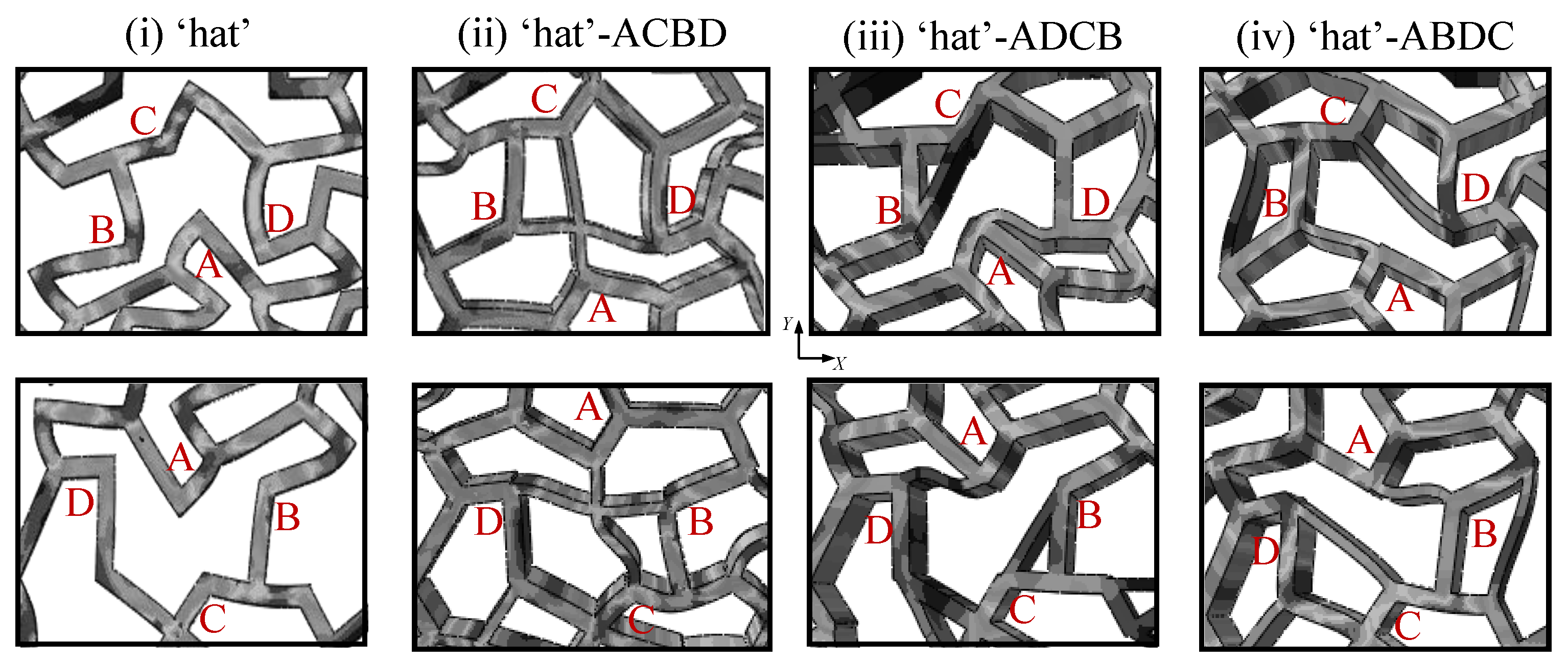

5.2.2. Microscale Unit Cell Deformation Characteristics

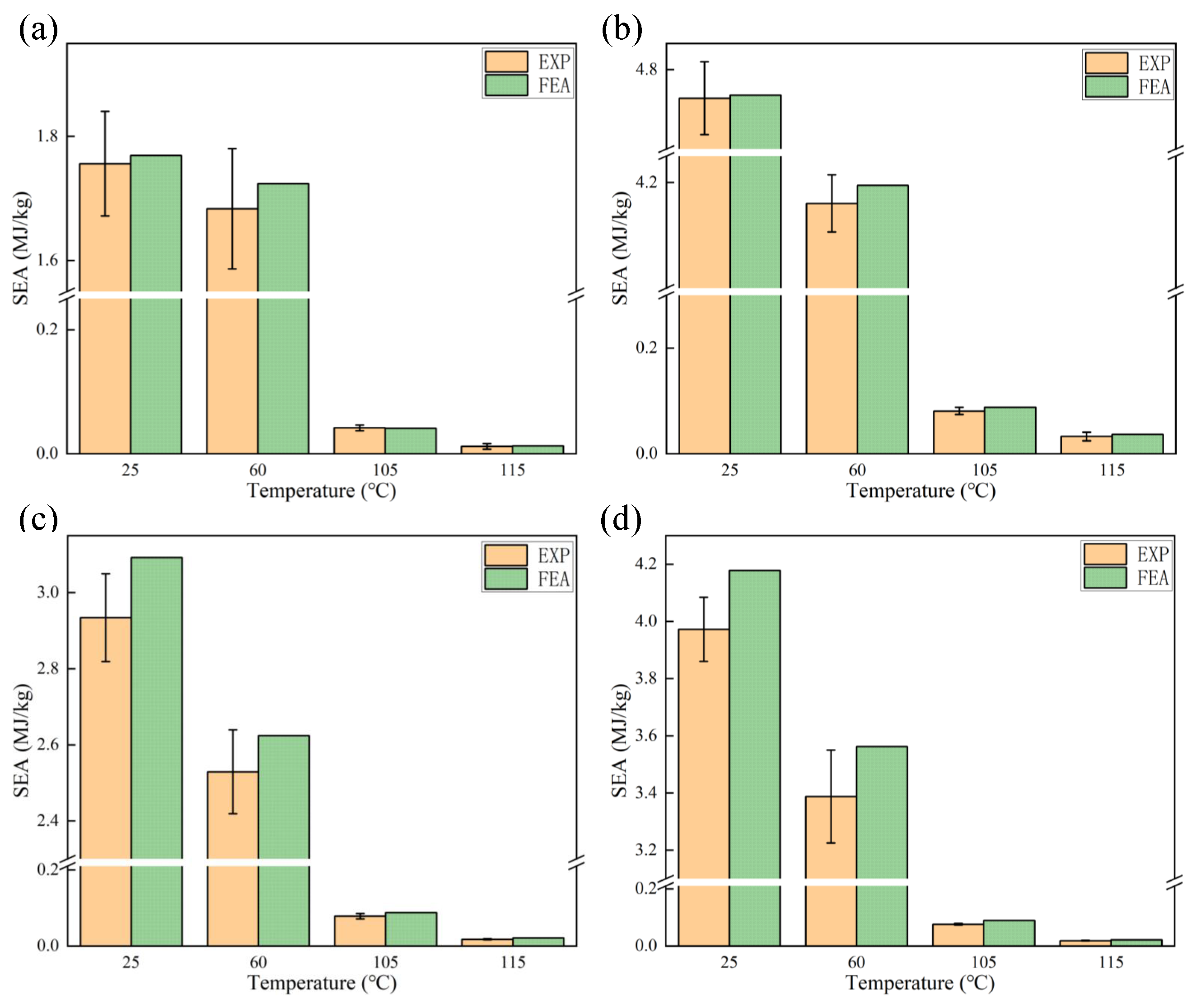

5.3. Absorption Performance Analysis

6. Conclusions

- The aperiodically arranged honeycomb metamaterial structures inspired by the ‘einstein’ monotile exhibit exceptional mechanical properties. The coordinated bending deformation between the concave corners of the unit cells effectively suppresses the lateral displacement of the structure. Compared with traditional periodically arranged honeycomb structures, the aperiodically arranged honeycomb structures show greater stability during overall deformation.

- By connecting the concave points of the “hat” unit cells to create supporting beams, the rigidity of the unit cells is significantly enhanced, thereby effectively improving the structure’s strength, stiffness, and energy absorption capacity. According to experimental data, the compressive modulus and compressive strength increased by approximately 3 to 8 times, and the energy absorption capacity increased by about 2 to 3 times. Therefore, the “hat” honeycomb metamaterial without added supporting beams performs relatively weaker in mechanical properties and energy absorption characteristics.

- A comparative analysis of the compressive mechanical responses of the four types of honeycomb metamaterials at different temperatures revealed that temperature variations significantly affect parameters such as the structure’s strength and modulus. Among them, the ‘hat’-ACBD honeycomb metamaterial forms a bidirectional anti-bending mechanism within the unit cells, which significantly enhances the structure’s strength and stiffness, resulting in excellent mechanical performance across different temperatures. The ‘hat’-ADCB and ‘hat’-ABDC honeycomb metamaterials show a noticeable increase in strength compared to the ‘hat’ honeycomb metamaterial at low temperatures, but this enhancement effect is no longer evident when the temperature exceeds .

- A comparison of the deformation characteristics of the four types of honeycomb metamaterials at different temperatures showed that the aperiodically arranged honeycomb structures all have good overall stability at low temperatures. However, when the temperature exceeds , only the “hat”-ACBD honeycomb metamaterial does not exhibit significant buckling, while the other three types of honeycomb metamaterials all show varying degrees of buckling.

- A comparative analysis of the energy absorption capacities of the four types of honeycomb metamaterials at different temperatures revealed that at low temperatures, the ‘hat’-ACBD honeycomb metamaterial has the best energy absorption capacity, followed by the ‘hat’-ABDC honeycomb metamaterial. When the temperature approaches , the differences in energy absorption capacity among the ‘hat’-ACBD, ‘hat’-ADCB, and ‘hat’-ABDC honeycomb metamaterials are not significant. However, when the temperature exceeds , the “hat”-ACBD honeycomb metamaterial still has the best energy absorption capacity.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Shechtman, I. Blech, D. Gratias, J.W. Cahn, Metallic phase with long-range orientational order and no translational symmetry, Phys. Rev. Lett. 53 (1984) 1951–1953.

- P. Gong, C. Hu, X. Zhou, L. Miao, X. Wang, Isotropic and anisotropic physical properties of quasicrystals, Eur. Phys. J. B 52 (2006) 477–481.

- M. Zaiser, S. Zapperi, Disordered mechanical metamaterials, Nat. Rev. Phys. 5 (2023) 679-688.

- D. Tuzes, P.D. Ispnovity, M. Zaiser, Disorder is good for you: the influence of local disorder on strain localization and ductility of strain softening materials, Mater. Today 73(2024).

- M. Hanifpour, C.F. Petersen, M.J. Alava, S. Zapperi, Mechanics of disordered auxetic metamaterials, Eur. Phys. J. B 91 (2018) 271.

- R.J. Moat, E. Muyupa, C. Imediegwu, D.J. Clarke, I. Jowers, U.G. Grimm, Compressive behaviour of cellular structures with aperiodic order, Results in Materials 15 (2022) 100293.

- R. Penrose, Pentaplexity. Eureka 39 (1978) 16–22.

- S. Choukir, N.Manohara, C.V. Singh, Disorder unlocks the strength-toughness trade-off in metamaterials, Appl. Mater. Today 42 (2025) 102579.

- D. Smith, J. S. Myers, C. S. Kaplan, C. Goodman-Strauss, An aperiodic monotile, arXiv preprint arXiv:2303 (2023) 10798.

- D.J. Clarke, F. Carter, I. Jowers, R.J. Moat, An isotropic zero Poisson’s ratio metamaterial based on the aperiodic ‘hat’ monotile, Appl. Mater. Today 35 (2023) 101959.

- R.J. Moat, D.J. Clarke, F. Carter, D. Rust, I. Jowers, A class of aperiodic honeycombs with tuneable mechanical properties, Appl. Mater. Today 37 (2024) 102127.

- D.J. Clarke, R. Moat, I. Jowers. 2024. Identification of mechanically representative samples for aperiodic honeycombs. Mater. Today Commun., 38, 108505.

- J. Jung, A. Chen, G.X. Gu, Aperiodicity is all you need: Aperiodic monotiles for high-performance composites. Mater. Today 73 (2024) 1–8.

- X. Wang, X. Li, Z. Li, Z. Wang, W. Zhai, Superior strength, toughness, and damage-tolerance observed in microlattices of aperiodic unit cells, Small 20 (2024) 2307369.

- X. Wang, Z. Li, J. Deng, T. Gao, K. Zeng, X. Guo, X. Li, W. Zhai, Z. Wang, Unprecedented strength enhancement observed in interpenetrating phase composites of aperiodic lattice Metamaterials, Adv. Funct. Mater. 35 (2025) 2406890.

- R. Rieger, A. Danescu, Macroscopic elasticity of the hat aperiodic tiling. Mech. Mater, 193 (2024) 104988.

- M. Naji, R.K.A. Al-Rub, Effective elastic properties of novel aperiodic monotile-based lattice metamaterials, Mater. Design 244 (2024) 113102.

- B. Sun, X. Guo. Mechanics of Topological High-Entropy Structures Made Out of ‘Einstein’Puzzle Pieces. preprints202407.

- C. Imediegwu, D. Clarke, F. Carter, U. Grimm, I. Jowers, R. Moat, Mechanical characterisation of novel aperiodic lattice structures, Mater. Design 229 (2023) 111922.

- Y. Liu, B. Xia, Y. Zhou, K. Wei, Disordered mechanical metamaterials with programmable properties. Acta Materialia, 285 (2025) 120700.

- C. Qi, F. Jiang, S. Yang, Advanced honeycomb designs for improving mechanical properties: A review, Compos. Part B-Eng. 227 (2021) 109393.

- S. Li, R. Yang, S. Sun, B. Niu, Advances in the analysis of honeycomb structures: a comprehensive review, Compos. Part B-Eng. 296 (2025) 112208.

- H. M. Hameed, H. M. Hasan, Exploring honeycomb structures: A review of their types, general applications, and role in vibration damping and structural stability, Structures, 76 (2025) 108837.

- H. Geramizadeh, S. Dariushi, S.J. Salami, Optimal face sheet thickness of 3D printed polymeric hexagonal and re-entrant honeycomb sandwich beams subjected to three-point bending, Compos. Struct. 291 (2022) 115618.

- Z.H. Xu, Y.J. Cui, K.F. Wang, B.L. Wang, B. Wang, Quasi-static compression and impact resistances of novel re-entrant chiral hybrid honeycomb structures, Compos. Struct. 366 (2025) 119206.

- Y. Dong, F. Yan, Z. Zhang, Three-dimensional annular negative stiffness honeycomb structure design and performance study, Compos. Struct. 367 (2025) 119229.

- S. Ouyang, Y. Zhong, H. Poh Leong, Y. Tang, R. Liu, Designing re-entrant nested star-shaped honeycombs for energy-absorbing and load-bearing capabilities. Eng. Struct. 335 (2025) 120258.

- N. Khan, A. Riccio, A systematic review of design for additive manufacturing of aerospace lattice structures: current trends and future directions, Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 149 (2024) 101021.

- W. Gao, W. Zhang, H. Yu, W. Xing, X. Yang, Y. Zhang, C. Liang, 3D CNT/MXene microspheres for combined photothermal/photodynamic/chemo for cancer treatment, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10 (2022) 996177.

- W. Liu, S. Janbaz, D. Dykstra, B. Ennis, C. Coulais, Harnessing plasticity in sequential metamaterials for ideal shock absorption, Nature, 634 (2024) 842–847.

- X. Zhang, Q. Sun, X. Liang, P. Gu, Z. Hu, X. Yang, M. Liu, Z. Sun, J. Huang, G. Wu, G. Zu, Stretchable and negative-poisson-ratio porous metamaterials, Nat. Commun. 15 (2024) 392.

- Q. Li, B. Sun, Numerical analysis of low-speed impact response of sandwich panels with bio-inspired diagonal-enhanced square honeycomb core. Int. J. Impact. Eng. 173 (2023) 104430.

- F. Wu, B. Sun, Study on functional mechanical performance of array structures inspired by cuttlebone. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 136 (2022) 105459.

- J. Wei, B. Sun, Bioinspiration: Pull-Out Mechanical Properties of the Jigsaw Connection of Diabolical Ironclad Beetle’s Elytra, Acta. Mech. Solida. Sin. 36 (2023) 86–94.

- J. Hutchinson, Determination of the glass transition temperature: Methods correlation and structural heterogeneity, J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 98 (2009) 579-589.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).