1. Introduction

Metamaterials and architected cellular solids based on Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces (TPMSs) have attracted significant interest due to their unique ability to combine lightweight design with tailored mechanical, thermal, and acoustic properties. TPMSs were first described in 1865 by Schwarz [1], who introduced notable examples such as the Schwarz’s primitive and diamond surfaces. Subsequent developments were made by Neovius [2] in 1883, who proposed the Neovius’ surfaces, and Schoen [3] in 1970, who identified the gyroid and I-Wrapped Package (IWP) surfaces. TPMSs are not only found in various natural systems, such as butterfly wing scales and biological membranes, but are also observed in artificial systems like zeolite crystals [4]. These surfaces can be modelled using implicit mathematical equations, often represented through Fourier series, where the coefficients dictate both the surface topology and its mechanical behaviour [5]. Furthermore, TPMS structures can be differentiated into sheet-based or solid-based structures: sheet-based TPMS structures can be generated by thickening the surface geometry, whereas solid TPMS types are created by solidifying the regions split by the TPMS parametric function [6].

Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces have emerged as promising candidates because of their attractive mechanical performance, particularly when compared to conventional lattice structures. Their smooth surfaces and continuous periodic architectures make them particularly suitable for additive manufacturing, enabling structures with high stiffness-to-weight ratios [7], tunable energy absorption [8], and multifunctional performance [9]. These characteristics have already led to applications in aerospace, automotive, and biomedical engineering, ranging from lightweight sandwich cores [10] to impact-mitigation components [11] and bone scaffolds [12]. Additionally, TPMSs can overcome one of the primary limitations of truss-based lattices, namely the stress concentrations that occur at the joints, by offering better interconnectivity and reducing the likelihood of failure under higher loads [13,14].

To fully exploit the potential of TPMSs in design and optimization, reliable prediction of effective mechanical properties is essential, as direct experimental testing of each topology and density level is often impractical and computationally expensive at the full-structure scale. The prediction of the effective mechanical behaviour of various TPMS topologies has already been explored by several authors, employing different methods for generating the topologies and perform the homogenisation. Refai et al. [15] employed the Finite Element Method (FEM) to study multiple geometries, including the gyroid, and reported that all showed an elastic response governed by cubic symmetry, except for the octahedral geometry, which displayed transverse isotropy. Ramirez et al. [16] also applied FEM-based homogenisation to primitive and gyroid structures at different relative densities and compared the results with those of array configurations of the same Representative Unit Cells (RUCs) obtained through numerical analyses. Zhang et al. [17] focused on hybrid TPMS structures, that is, a combination of multiple topologies through Boolean union operation, with the objective of reducing structural anisotropy. By contrast, Liu et al. [18] adopted asymptotic homogenisation, implemented in MATLAB using voxel models, to study the primitive, IWP, and gyroid topologies. Despite the growing adoption of TPMS-based lattices, accurately and efficiently predicting their effective mechanical behaviour remains a challenge. FEM homogenisation is widely used and provides detailed insight, but it often requires high computational effort, especially when exploring multiple relative densities and topologies.

In contrast, the Mechanics of Structured Genome (MSG) method [19] offers an alternative semi-analytical framework that can significantly reduce computational cost while preserving accuracy in capturing the essential physics of periodic heterogeneous materials. More details about this method will be given in the Methodology. A systematic comparison between these two approaches has, to the authors’ knowledge, not yet been carried out in the literature. The present work aims to address this gap by clarifying the respective strengths, limitations, and applicability of the two methods within the design workflow of architected metamaterials.

The paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, the modelling of TPMSs and RUCs is introduced, followed by the theoretical background of FEM-based RUC homogenisation and MSG-based homogenisation, along with a comparison between the two methods.

Section 3 presents the homogenisation results obtained for the different TPMS structures, including the effective elastic properties, as well as the distribution of the directional Young’s modulus. These results are then used to compare the two approaches in terms of their strengths and weaknesses. Finally,

Section 4 summarizes the main findings of the work.

2. Methodology

In this section, the approach used for generating the TPMS and RUC structures is presented, together with a description of the homogenisation methods employed, namely FEM-based RUC homogenisation and MSG-based homogenisation.

2.1. Generation of TPMS Geometry

To generate TPMS models for FEM or MSG analysis, different methods can be followed. One option is to create isosurfaces using parametric equations in software such as MATLAB [20] or Surface Evolver [21] among many, then add thickness in a CAD program to obtain a solid model [22]. The geometry can subsequently be meshed in tools like Hypermesh [23] or Gmsh [24]. Another alternative is to use dedicated software for modelling TPMS structures, such as MSLattice [25]. With MSLattice, RUCs of various TPMS topologies can be created with different sizes, relative densities, and resolutions, as well as with customized shapes and functional grading [17]. Both sheet and solid TPMSs can be generated. The output files are in STL format; therefore, additional software is required to generate solid models for further analysis. A more stream-lined alternative, used in this work, is offered by the Python library Microgen [26]. This library allows the modelling of a wide range of RUCs, from strut-based unit cells to general TPMS topologies. Furthermore, it is possible to extend the original code to be able to model any type of TPMS using parametric equations. Similarly to MSLattice, Microgen is not limited to unit-cells, but also supports the generation of array configurations and spherical shapes. It provides flexibility in output formats, including STL, mesh files, and even input files that can be used directly in Abaqus, removing the need for intermediate software. An important aspect when performing FEM homogenisation with Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBCs) is to ensure that the mesh is periodic such that these boundary conditions are applied correctly and the results remain reliable. Microgen addresses this requirement by offering a function to create periodic meshes through Gmsh [27]. Depending on the software used for the RUC generation, it is possible to either have as an input the thickness of the RUC or its relative density. In most of the literature explored, the latter is more commonly used, as is also the case for Microgen. Our tool assessment showed us that it is not guaranteed that the geometry created will be identical even though the same TPMS topology is chosen in Microgen or MSLattice. There might be differences in the thickness spatial distribution due to how the material is distributed based on the algorithms used to create the geometry and the calculations followed to calculate the relative density.

2.2. FEM-Sased RUC Homogenisation

To determine the effective mechanical properties of the TPMS architectures, this study employs a computational homogenisation scheme based on the finite element analysis of a Representative Unit Cell. This approach, often termed “virtual testing”, is a robust and widely accepted method for characterising complex microstructures by simulating their response under well-defined boundary conditions [28]. The fundamental principle is to replace the complex, heterogeneous TPMS lattice with an equivalent (or effective) homogeneous material, whose constitutive behaviour can be described by a constant, effective material stiffness tensor

. The relationship between the volume-averaged (macroscopic) stress tensor

and strain tensor

for the equivalent homogeneous material is governed by the generalised Hooke’s law:

Within the RUC, the local stress field

must satisfy the static equilibrium equation, which, assuming the absence of body forces, reads [28]:

where an index preceded by a comma stands for a derivative with respect to that index. Combining this with the local constitutive relation and the strain-displacement kinematics, the problem is formulated in terms of the displacement field

as a well-posed boundary value problem.The objective of the RUC analysis is to solve for the local stress and strain fields resulting from a set of prescribed macroscopic strains and then, compute the corresponding macroscopic stresses to populate the effective stiffness matrix

. For periodic materials such as TPMS lattices, the choice of boundary conditions is critical. Periodic Boundary Conditions are considered the most appropriate as they accurately represent a unit cell’s kinematic constraints within an infinite lattice and satisfy the Hill-Mandel condition of macro-homogeneity, ensuring energetic equivalence between the micro- and macro-scales. PBCs enforce that the displacement fluctuations on opposite faces of the RUC are equal, and the tractions are equal and opposite. The displacement

at a point

within the RUC is decomposed into a macroscopic part and a fluctuating part

[28]:

The periodicity constraint is applied to the fluctuation field, requiring that it has the same value on corresponding points on opposite faces of the RUC cube (e.g., faces at

and

):

In the Abaqus/CAE environment, these conditions are implemented by applying constraint equations that link the Degrees of Freedom (DOFs) of corresponding node pairs on opposite faces of the TPMS unit cell [29]. The effective stiffness matrix is computed by conducting a series of six independent static linear elastic simulations on the high-fidelity finite element mesh of the TPMS RUC. For each simulation, a distinct unit macroscopic strain component is prescribed, while all other components are set to zero. The six fundamental load cases correspond to three normal strains (

) and three shear strains (

). For each of the six analyses, the following steps are performed:

A single component of the macroscopic strain tensor is set to unity (e.g., ), and all others are set to zero. This macroscopic strain is enforced on the RUC via the PBCs.

A static analysis is performed in Abaqus to solve for the resulting local stress field throughout the entire volume V of the RUC.

The macroscopic stress tensor

is calculated by volume-averaging the local stress field [28]:

The resulting six-component vector of volume-averaged macroscopic stresses , , , , , forms the corresponding column of the effective stiffness matrix.

By repeating this procedure for all six unit strain cases, the complete anisotropic stiffness matrix for the TPMS architecture is systematically populated.

2.3. Mechanics of Structure Genome-Based Homogenisation

To determine the effective mechanical properties of TPMS architectures, this study also employs the Mechanics of Structure Genome methodology. MSG is a unified multi-scale constitutive modelling approach that is particularly well-suited for periodic heterogeneous materials [19]. The core of the methodology is the Structure Genome (SG), defined as the smallest mathematical building block that contains all the necessary constitutive information of the structure, analogous to how a biological genome contains the information for an organism’s development. For a material with three-dimensional heterogeneity, such as a TPMS lattice, the SG is a three-dimensional repeating unit cell, serving a similar role to the conventional RUC [19,30,31]. However, the strength of MSG lies in its rigorous theoretical foundation, which is based on the principle of minimum information loss. This principle states that the homogenised model should be constructed by minimizing the discrepancy in strain energy between the original heterogeneous model and the effective homogeneous model. The formulation begins by decomposing the displacement field

within the SG into a macroscopic homogenised component

and a fluctuating component

, which captures the local microstructural variations. This kinematic relationship is expressed as:

where

and

represent the macroscopic and microscopic coordinates, respectively. The macroscopic displacement

is defined as the volume average of the local displacement field,

. This definition imposes a zero-average constraint on the fluctuation function, i.e.,

. Following this kinematic assumption, the local strain field

can be related to the macroscopic strain

and the gradient of the fluctuation function. Neglecting higher-order terms, this relationship is given by:

where

denotes the symmetric part of the gradient of the fluctuation function. To solve for the unknown fluctuation function

, MSG minimizes the strain energy of the original model over the SG domain, subject to the relevant constraints. The variational problem leads to the following Euler-Lagrange equation, which governs the response of the SG [19,30]:

Here,

is the local, spatially varying stiffness tensor of the constituent material within the SG. For TPMS architectures, which are periodic structures, the fluctuation function

must also be periodic. This governing equation can be solved numerically (e.g., using the finite element method) to find

in terms of the prescribed macroscopic strains

. The solution can be expressed symbolically as

, where

is an influence function tensor that links the macroscopic strains to the local displacement fluctuations [19,30]. Once determined, the effective stiffness tensor

for the homogenised TPMS structure is computed by volume averaging the strain energy density, yielding the final expression:

This formulation provides a direct and computationally efficient pathway to calculate the full three-dimensional anisotropic stiffness matrix of the TPMS architecture from a single analysis of its fundamental building block, the SG.

2.4. Comparison of RUC Analysis and MSG

While both the FE-based RUC analysis and the MSG are powerful tools for mechanical homogenisation, they are founded on different theoretical principles and exhibit significant differences in computational implementation and scalability. This section provides a comparative analysis of the two approaches, contextualising their application to the multi-scale modelling of TPMS architectures.

2.4.1. Theoretical Equivalence for 3D Periodic Media

For the specific case of a three-dimensional, periodic microstructure, such as the TPMS lattices studied in this work, the underlying governing equations for RUC analysis with PBCs and MSG are identical. Both methods ultimately solve for a displacement fluctuation field that satisfies the same equilibrium equation given in Equation 8 within the unit cell [28]. Consequently, when applied to the same three-dimensional unit cell with PBCs, both RUC analysis and MSG are expected to yield the exact same results for effective properties and local fields, provided the numerical discretisation is equivalent. The primary distinction, therefore, lies not in the final result for this class of problems, but in the efficiency and elegance of the computational workflow.

2.4.2. Computational Implementation and Efficiency

A significant divergence between the two methods emerges from their computational implementation. A standard RUC analysis performed in commercial FE software like Abaqus typically requires setting up and solving six independent boundary value problems to populate the stiffness matrix. The application of PBCs via coupled equation constraints affects the global stiffness matrix of the FE model, necessitating a full re-factorisation for each of the six unit strain load cases. In contrast, the MSG framework is structured to be far more efficient. Its implementation solves the problem by factorising the linear system’s coefficient matrix only once. The six load cases, corresponding to the six unit macroscopic strains, are then treated as multiple right-hand sides. This allows for the solution to be obtained with one factorisation followed by six back-substitutions, a computationally much cheaper process. This makes the MSG approach theoretically five to six times more efficient than a conventional RUC analysis for computing the complete stiffness matrix.

2.4.3. Fundamental Advantages of the MSG Framework

Beyond computational speed-up for three-dimensional problems, MSG holds fundamental advantages that establish it as a more versatile and scalable multi-scale modelling theory.

Variational Foundation: MSG is derived directly from a variational statement seeking to minimise the information loss (in terms of strain energy) between the original and homogenised models. RUC analysis, while satisfying the Hill-Mandel condition, is typically formulated based on the strong form of the boundary value problem.This variational foundation gives MSG a more rigorous mathematical underpinning.

Dimensional Scalability: The most powerful feature of MSG is its ability to use a Structure Genome of the lowest possible dimensionality to characterise the material. For instance, to find the complete three-dimensional effective properties of a laminated composite (one-dimensional heterogeneity) or a continuous fibre-reinforced composite (two-dimensional heterogeneity), MSG can perform the analysis on a one- or two-dimensional SG, respectively. This drastically reduces the computational cost by avoiding the need to mesh and solve a full 3D domain. A conventional RUC analysis, in contrast, would still require a full three-dimensional RUC to extract its properties, making it unnecessarily expensive for such materials.

While the TPMS architectures in this study possess three-dimensional heterogeneity and, thus, require a three-dimensional SG, this inherent scalability makes MSG a superior general-purpose tool for the multi-scale analysis of a wider class of architected and composite materials, offering unparalleled efficiency without sacrificing accuracy.

3. Numerical Results and Discussion

To compare the FEM-based RUC homogenisation method with the MSG approach, a comprehensive study was conducted by analysing various TPMS topologies and predicting their effective elastic properties, with the structures being: gyroid, diamond, PMY and F-Rhombic Dodedecahedron (F-RD). The FEM simulations were performed using Abaqus, with PBCs applied via the Micromechanics plug-in. For the MSG approach, the in-house C++ code CmbsFE, previously employed in Koutsawa et al. [30,31], was extended in this work to investigate the elastic behaviour of TPMS structures.

To ensure the reliability of the results, two configurations from previously published works were first reproduced to validate the methods used in this study. These configurations are presented in Table 1, together with the topology of the TPMS structure, the relative density of the RUC (ratio between the effective volume of the TPMS RUC and that of the RUC bounding box), its size, and the base material properties (Young’s modulus , shear modulus and Poisson’s ratio ).

Table 1.

Configurations from literature used for validation

Table 1.

Configurations from literature used for validation

| Source |

TPMS |

|

RUC size [mm] |

[GPa] |

[GPa] |

|

| Refai et al. [15] |

Gyroid |

0.1 |

3 |

110 |

41 |

0.34 |

| Zhang et al. [17] |

Diamond |

0.3 |

5 |

190 |

73 |

0.30 |

For all the analysed models, a quadratic tetrahedral mesh was used. A convergence study was carried out to verify that the mesh resolution was sufficient to accurately estimate the effective properties. The results showed that, for RUCs with cubic sizes of 3 and 5 mm, a mesh element size of up to 0.3 mm can accurately predict the effective elastic properties, with an error as high as 1%. The effective elastic properties are normalised using the properties of the elastic material used to characterise the TPMS structures. In doing so, the properties are made independent of the bulk material used. The normalised properties are defined as follows:

where

,

, and

are respectively the effective Young’s modulus, shear modulus, and Poisson’s ratio.

3.1. Gyroid TPMS

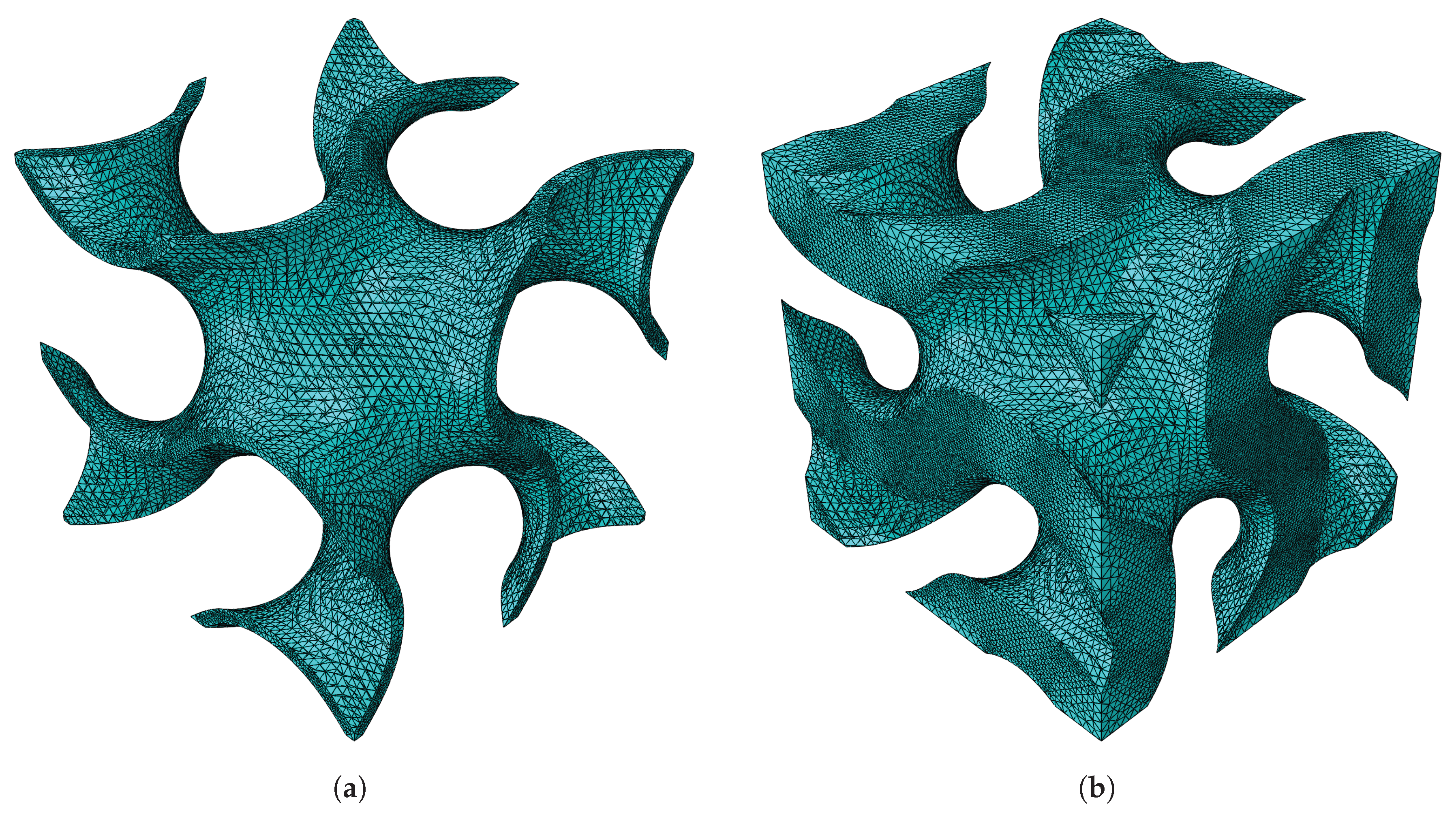

The first topology observed is the gyroid shape. The first configuration given in Table 1 is followed to validate the results obtained using FEM and MSG. For better visualisation, the gyroid RUCs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Gyroid RUC at minimum and maximum relative densities: (a) . (b) .

Figure 1.

Gyroid RUC at minimum and maximum relative densities: (a) . (b) .

The normalised effective elastic properties are presented in Table 2 for the minimum and maximum relative densities analysed.

Table 2.

Homogenisation results for gyroid shape.

Table 2.

Homogenisation results for gyroid shape.

| Source |

|

|

|

|

| Refai et al. [15] |

0.1 |

0.032 |

0.035 |

1.000 |

| FEM |

0.1 |

0.032 |

0.035 |

1.000 |

| MSG |

0.1 |

0.032 |

0.035 |

1.000 |

| FEM |

0.5 |

0.249 |

0.293 |

0.896 |

| MSG |

0.5 |

0.249 |

0.293 |

0.896 |

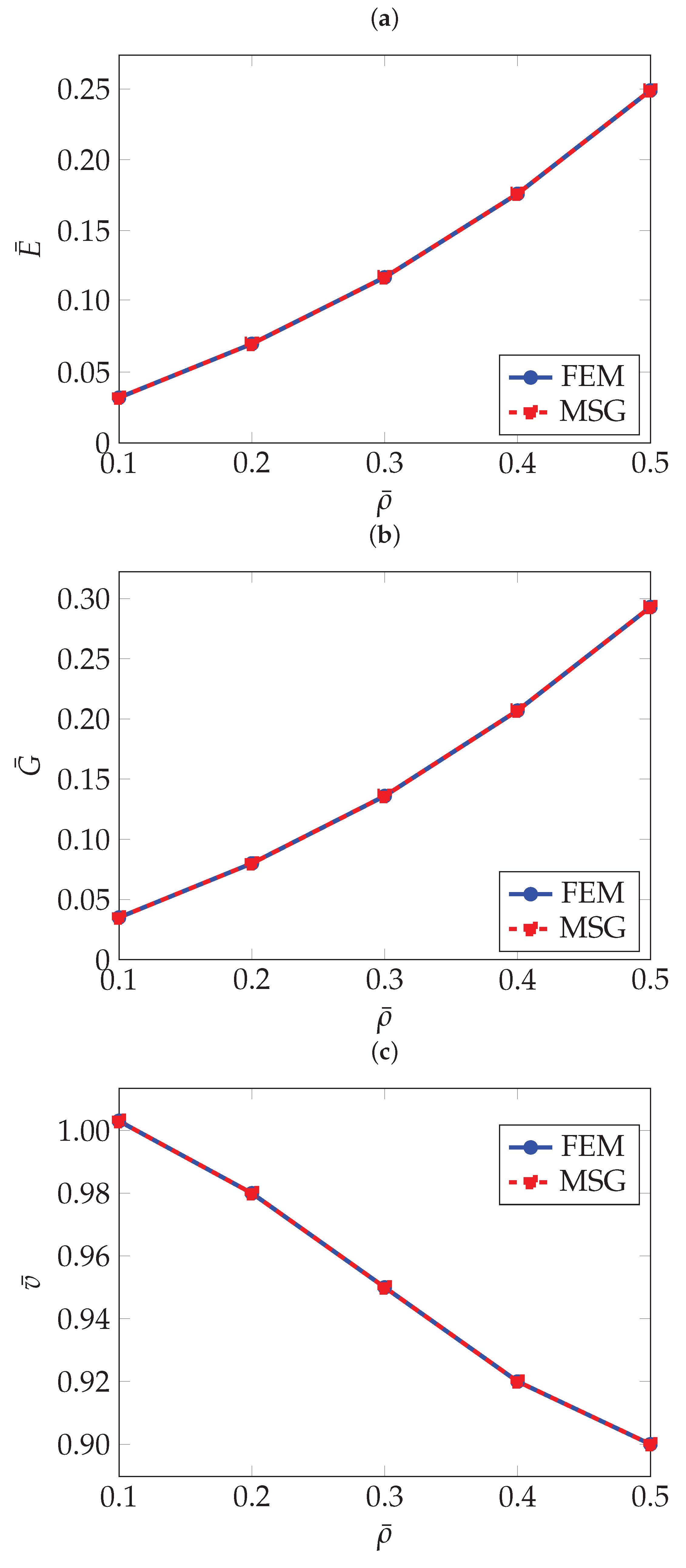

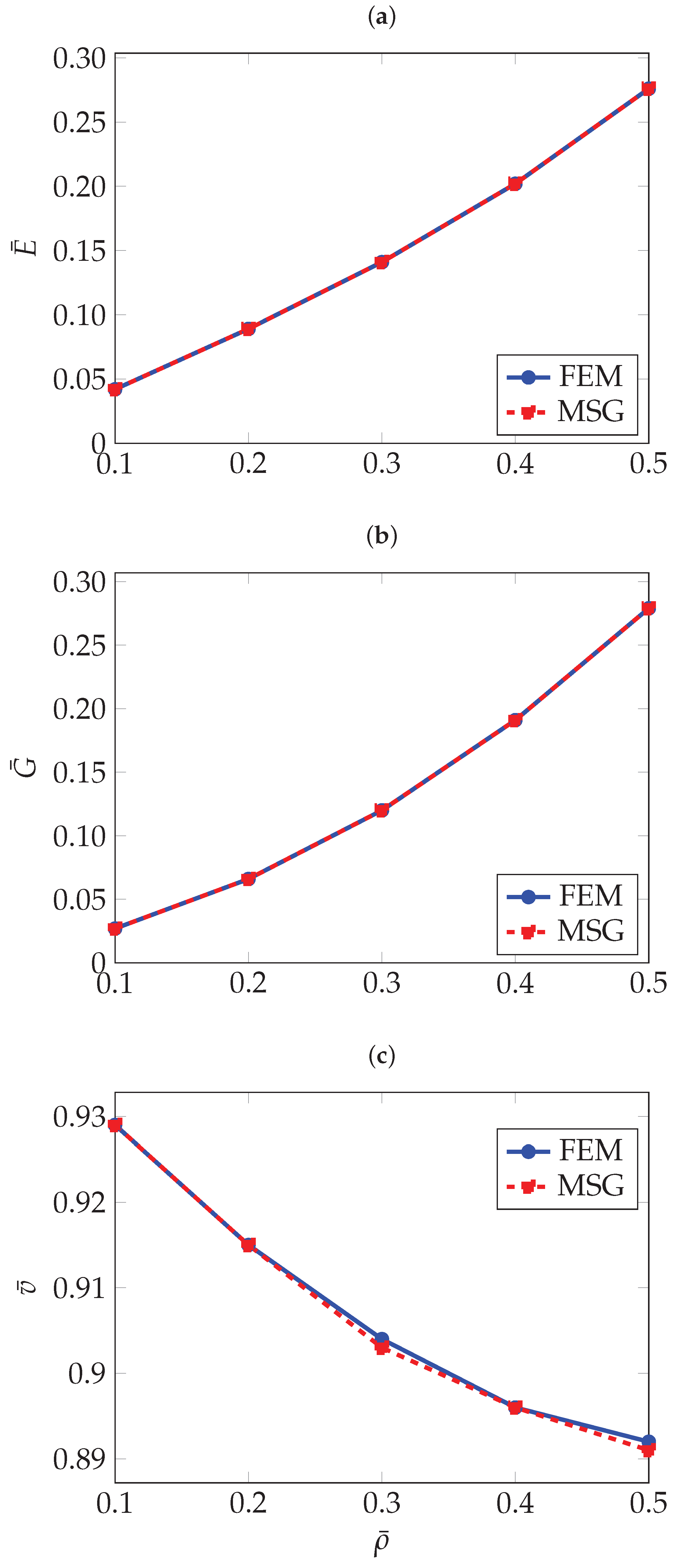

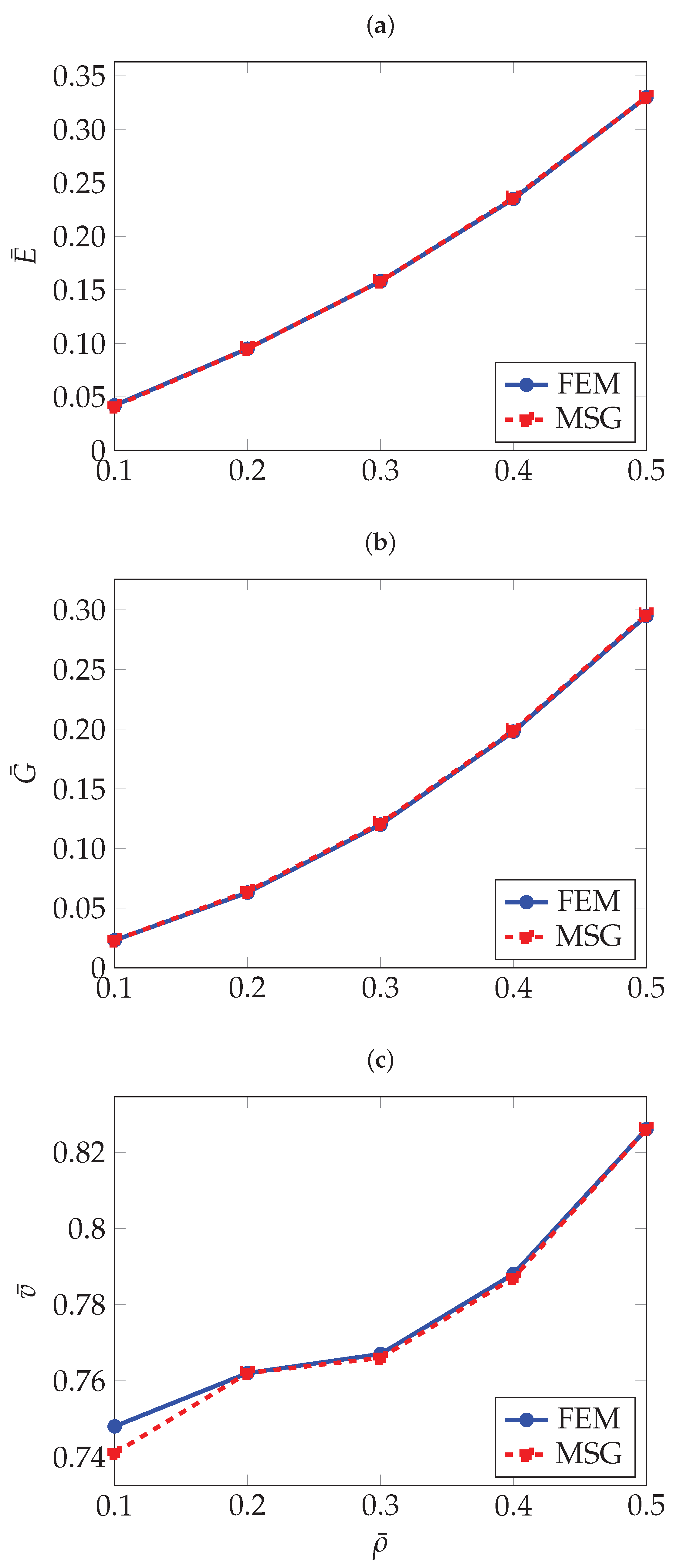

As can be seen in Table 2, the FEM and MSG-based results match closely. The effect of the relative density on the effective elastic properties can be better seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Normalised effective elastic properties of gyroid TPMS as a function of relative density: (a) Normalised effective Young’s modulus , (b) Normalised effective shear modulus , (c) Normalised effective Poisson’s ratio .

Figure 2.

Normalised effective elastic properties of gyroid TPMS as a function of relative density: (a) Normalised effective Young’s modulus , (b) Normalised effective shear modulus , (c) Normalised effective Poisson’s ratio .

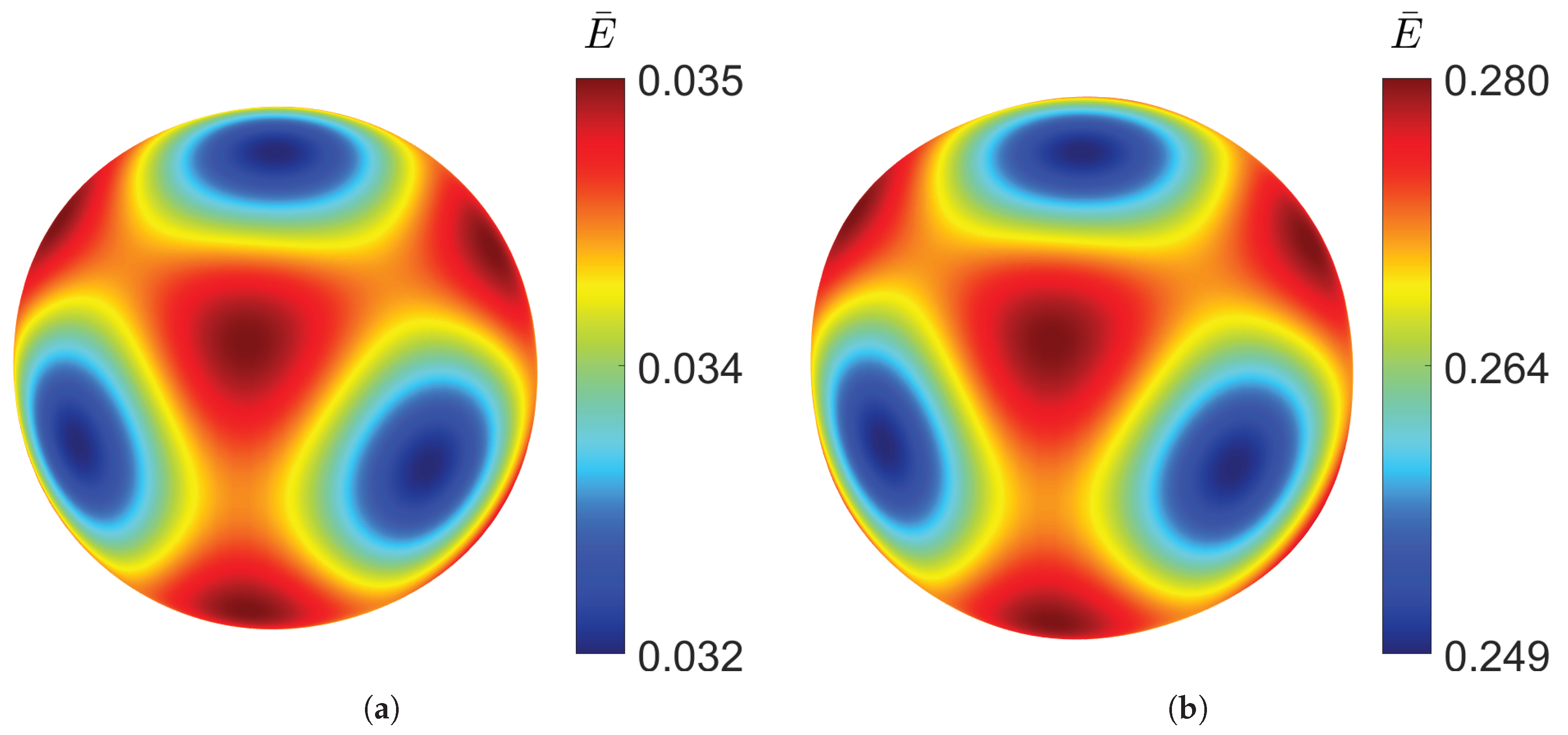

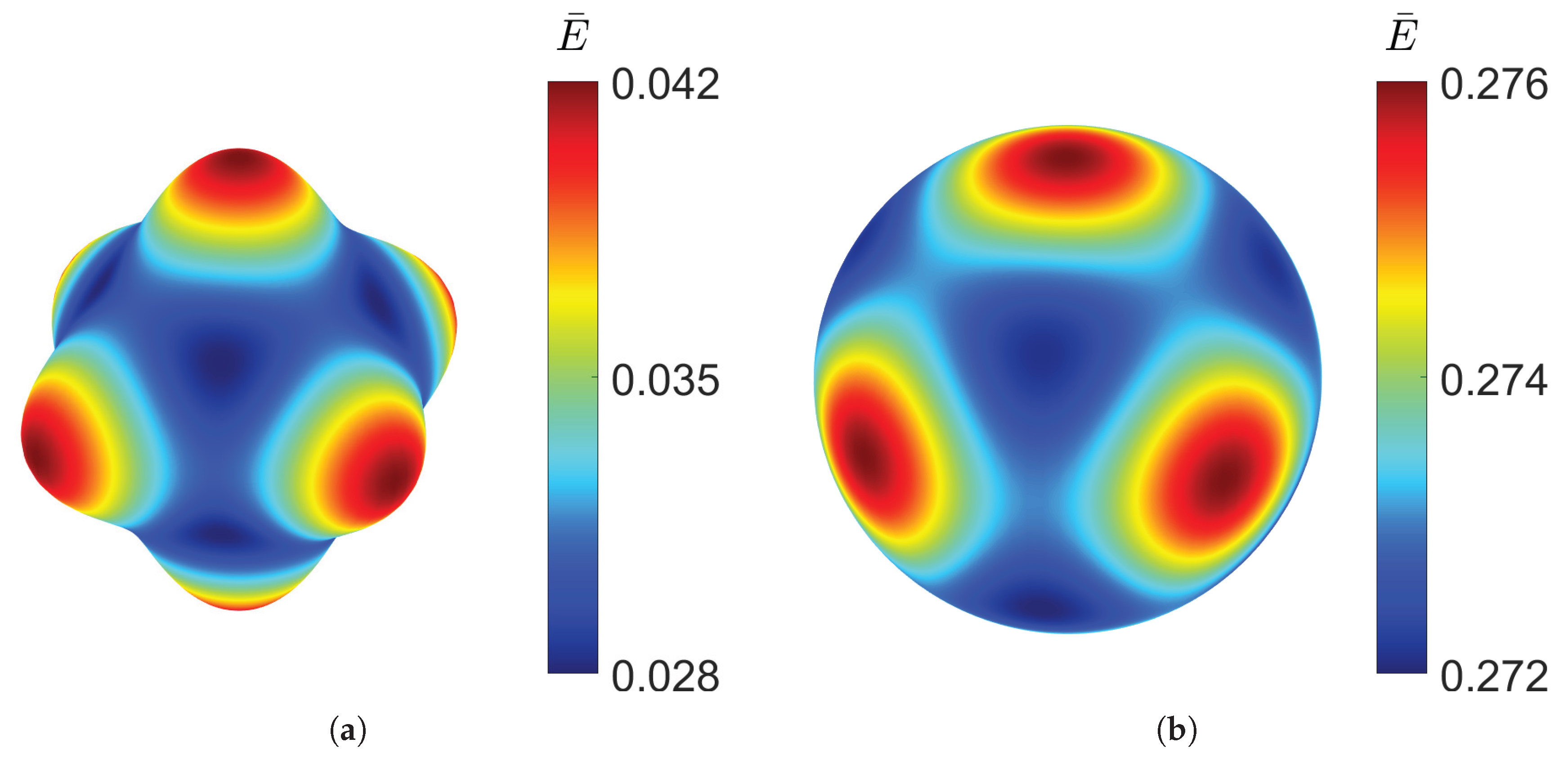

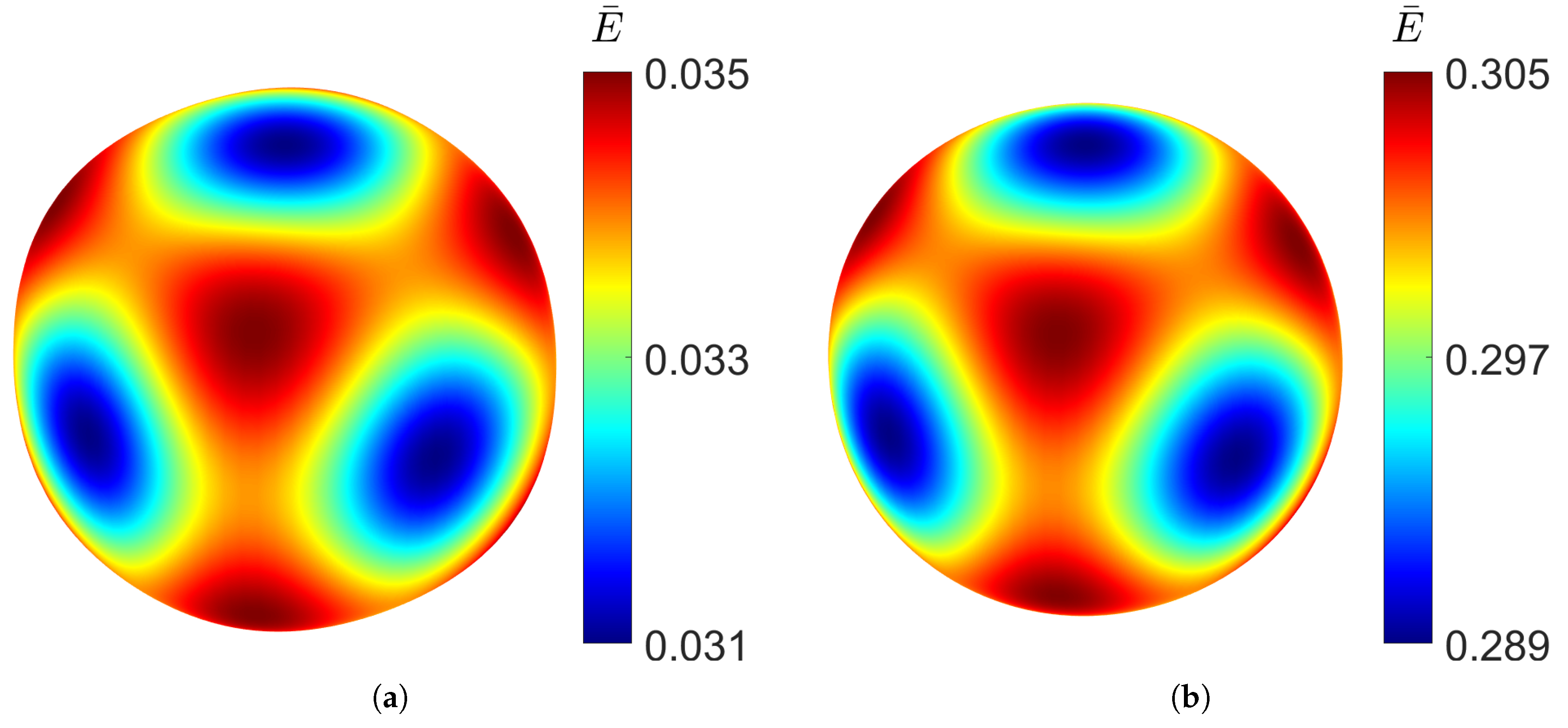

As it can be expected, the higher the relative density, and therefore a higher thickness, the higher both Young’s and shear moduli. On the other hand, the Poisson’s ratio exhibits an apparently opposite trend. Further analysis of RUCs with a relative density greater than 50% revealed that the Poisson’s ratio increases, approaching the value of the original solid material. This behaviour is expected, as higher relative density means the RUC becomes increasingly similar to the bulk material. The spatial distribution of the Young’s modulus can be determined from the effective stiffness tensor obtained through homogenisation using the tool developed by Dong [32]. Figure 3 shows the directional distribution of the Young’s modulus for the gyroid structure for a relative density as low as 10% and as high as 50%.

Figure 3.

Young’s modulus distribution of gyroid TPMS at different relative densities: (a) . (b) .

Figure 3.

Young’s modulus distribution of gyroid TPMS at different relative densities: (a) . (b) .

It can be observed that even at low density, the distribution closely approaches a spherical shape, indicating a high degree of isotropy. Increasing the relative density does not produce significant changes in the distribution of the elastic modulus, demonstrating the structural stability. Although the variation is minimal, the gyroid is slightly stiffer along the principal axes than along the diagonal directions. The cubic symmetry, characteristic of TPMS structures, can also be clearly observed.

3.2. Diamond TPMS

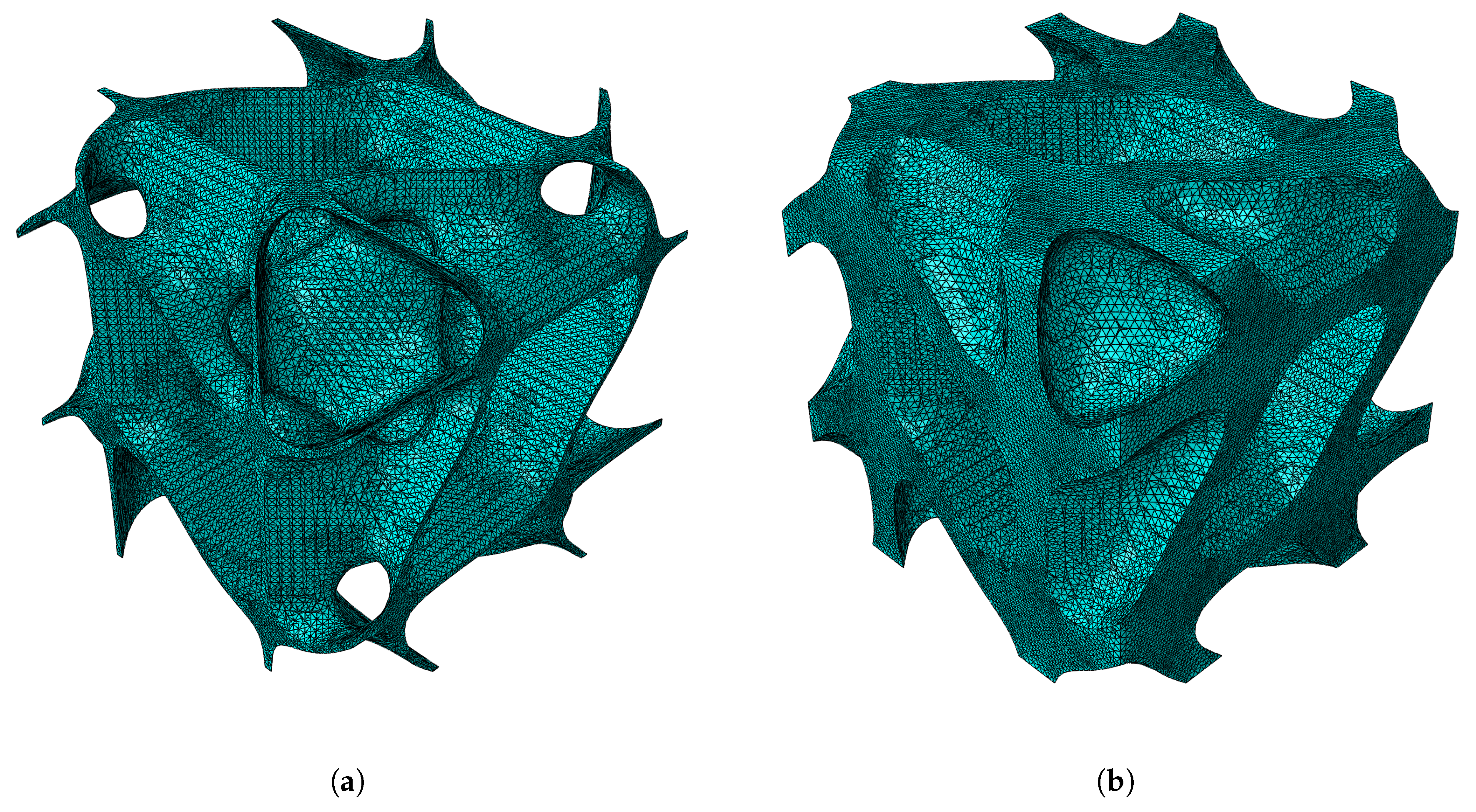

For the diamond shape, the second configuration presented in Table 1 is considered. Figure 4 show the diamond RUCs at the lower and highest considered relative densities.

Figure 4.

Diamond RUC at minimum and maximum relative densities: (a) . (b) .

Figure 4.

Diamond RUC at minimum and maximum relative densities: (a) . (b) .

Table 3 presents the computed equivalent properties, The results by Zhang et al. [17] for a relative density of 30% are used for validation.

Table 3.

Homogenisation results for diamond shape.

Table 3.

Homogenisation results for diamond shape.

| Source |

|

|

|

|

| FEM |

0.1 |

0.042 |

0.027 |

0.929 |

| MSG |

0.1 |

0.042 |

0.027 |

0.929 |

| Zhang et al. [17] |

0.3 |

0.142 |

- |

- |

| FEM |

0.3 |

0.141 |

0.120 |

0.904 |

| MSG |

0.3 |

0.141 |

0.120 |

0.903 |

| FEM |

0.5 |

0.276 |

0.279 |

0.892 |

| MSG |

0.5 |

0.276 |

0.279 |

0.891 |

The results computed via the FEM and MSG approaches match. In Figure 5, the normalised effective elastic properties as a function of the relative density are given.

Figure 5.

Normalised effective elastic properties of the diamond structure as a function of relative density: (a) Normalised effective Young’s modulus , (b) Normalised effective shear modulus , (c) Normalised effective Poisson’s ratio .

Figure 5.

Normalised effective elastic properties of the diamond structure as a function of relative density: (a) Normalised effective Young’s modulus , (b) Normalised effective shear modulus , (c) Normalised effective Poisson’s ratio .

As observed for the gyroid structure, the diamond also shows an increase in Young’s modulus and shear modulus with higher relative density, and the opposite trend for the Poisson’s ratio. With a large difference between the elastic Young’s modulus along the the principal axes and the diagonal directions, the diamond topology shows high levels of anisotropy at low densities, which can be observed in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Young’s modulus distribution of diamond TPMS at different relative densities: (a) . (b) .

Figure 6.

Young’s modulus distribution of diamond TPMS at different relative densities: (a) . (b) .

As the volume of the material increases, the diamond TPMS behaviour becomes more isotropic, as shown by a spherical distribution for the RUC at relative density .

3.3. PMY

The effective elastic properties of the PMY structure are also investigated, where the geometrical parameters and base material properties of the second case in Table 1 are used. The PMY RUCs considered in this study are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

PMY RUC at minimum and maximum relative densities: (a) . (b) .

Figure 7.

PMY RUC at minimum and maximum relative densities: (a) . (b) .

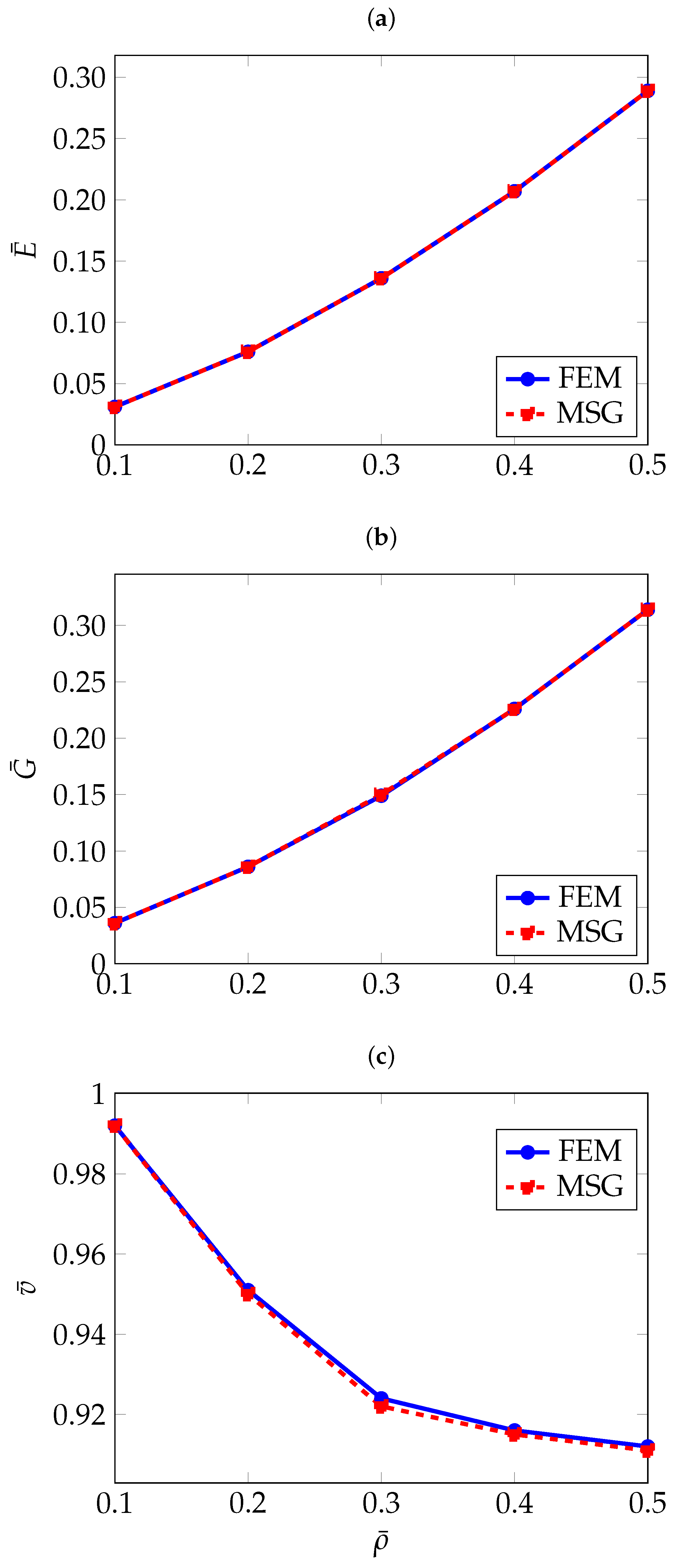

To the author’s knowledge, this topology have not yet been widely investigated, therefore, the comparison is limited to the results obtained using the FEM and MSG methods. As shown in Table 4, which presents the homogenisation results, and in Figure 8, where these results are plotted as a function of relative density, a strong agreement is observed between the two methods.

Table 4.

Homogenisation results for PMY shape.

Table 4.

Homogenisation results for PMY shape.

| Source |

|

|

|

|

| FEM |

0.1 |

0.031 |

0.036 |

0.992 |

| MSG |

0.1 |

0.031 |

0.036 |

0.991 |

| FEM |

0.5 |

0.289 |

0.314 |

0.912 |

| MSG |

0.5 |

0.289 |

0.314 |

0.911 |

Figure 8.

Normalised effective elastic properties of PMY as a function of relative density: (a) Normalised effective Young’s modulus , (b) Normalised effective shear modulus , (c) Normalised effective Poisson’s ratio .

Figure 8.

Normalised effective elastic properties of PMY as a function of relative density: (a) Normalised effective Young’s modulus , (b) Normalised effective shear modulus , (c) Normalised effective Poisson’s ratio .

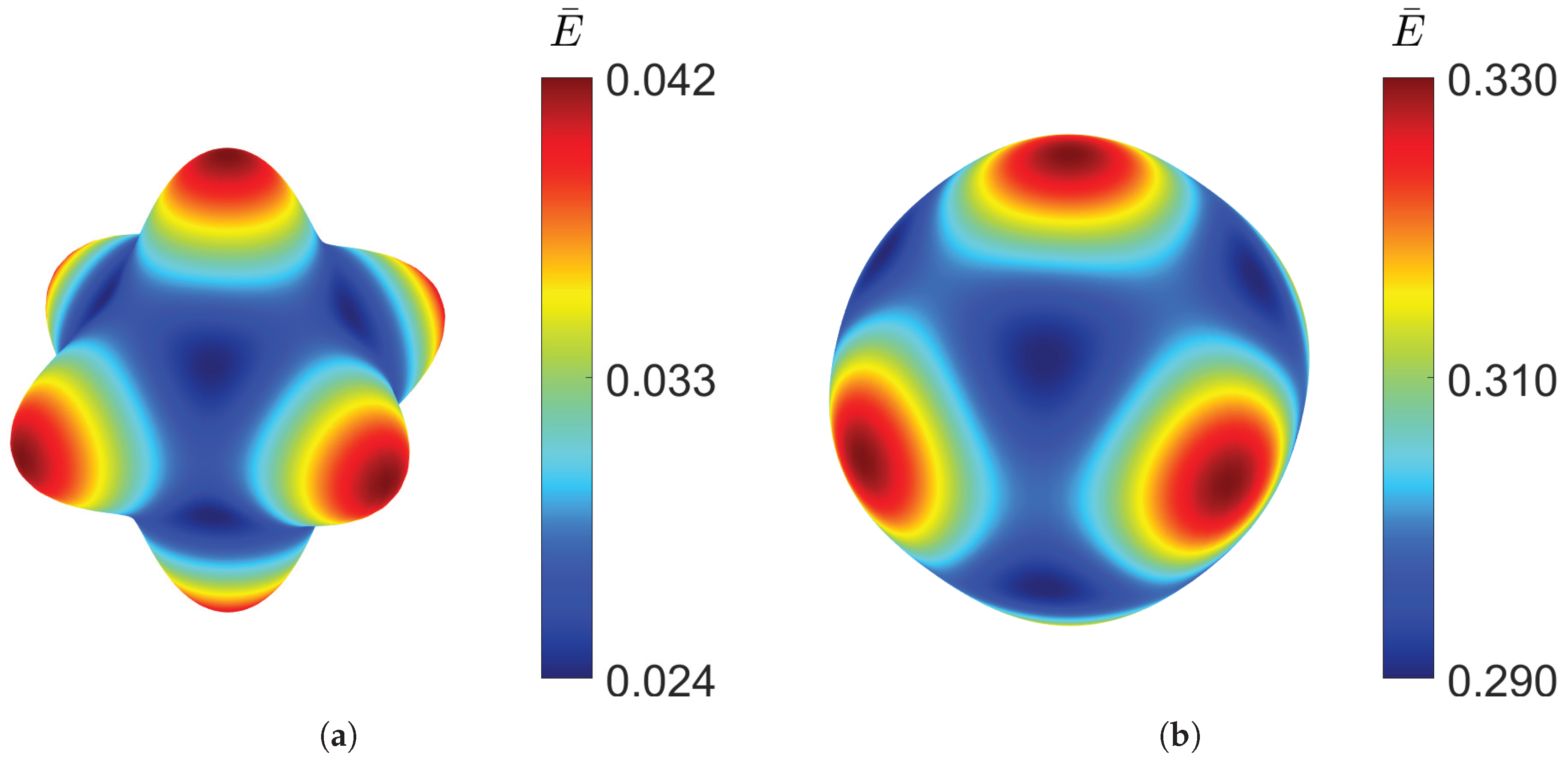

Similar to the gyroid shape, the PMY structure also shows high isotropy at low densities, as can be seen in Figure 9, where the directional Young’s modulus distribution is visualised.

Figure 9.

Elastic Young’s modulus distribution of PMY TPMS at different relative densities, RUC at: (a) and (b) .

Figure 9.

Elastic Young’s modulus distribution of PMY TPMS at different relative densities, RUC at: (a) and (b) .

However, the stiffness distribution shows that the diagonal directional Young’s modulus is the highest, whereas in the x, y, and z directions of the RUC, it is the lowest.

3.4. F-Rhombic Dodecahedron (F-RD)

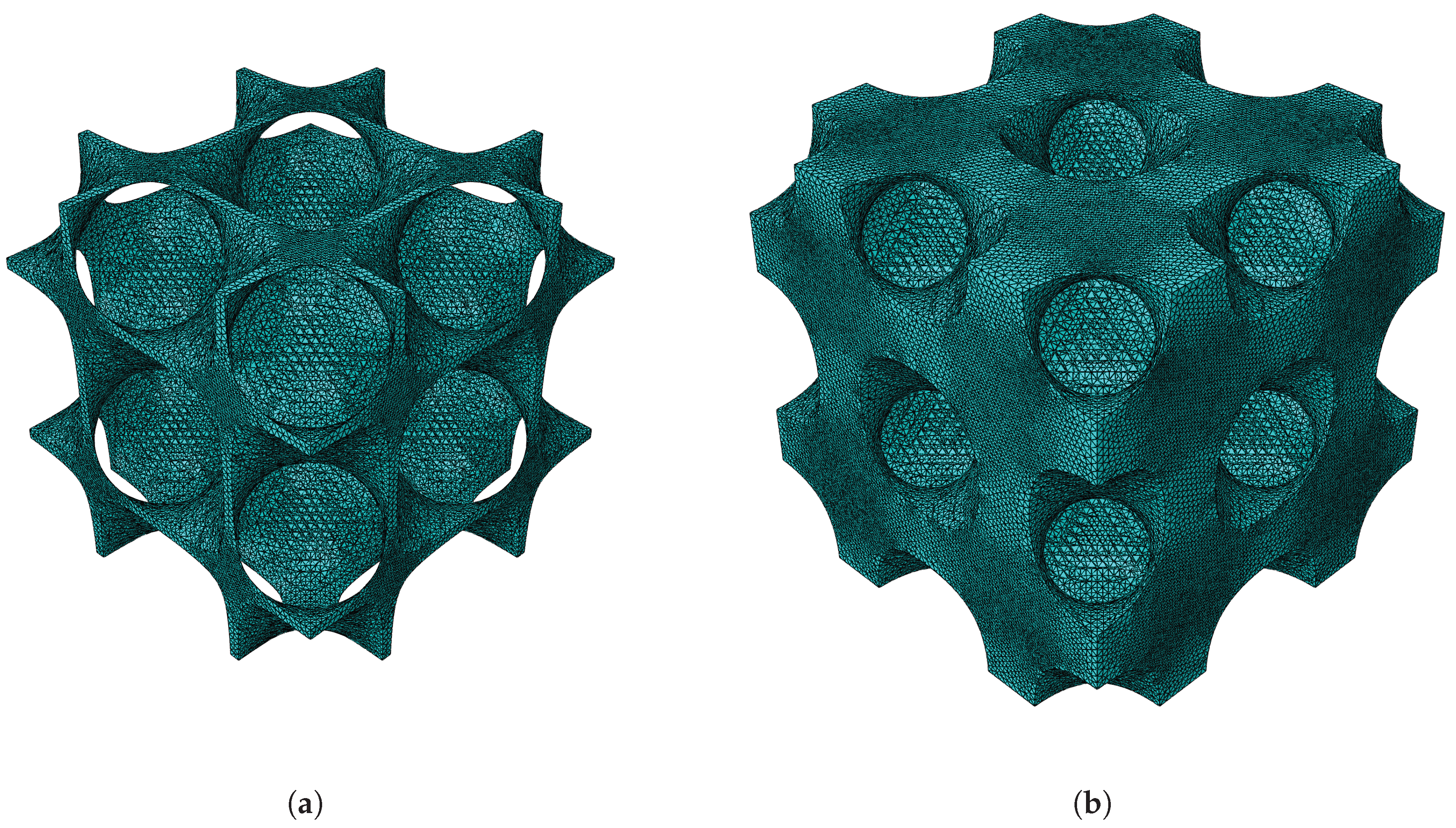

For the F-RD shape, once again the second case properties in Table 1 are used. A visualisation of the RUCs investigated given in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

F-RD RUC at minimum and maximum relative densities: (a) , (b) .

Figure 10.

F-RD RUC at minimum and maximum relative densities: (a) , (b) .

As with the previously analysed TPMS structures, the FEM and MSG results show good agreement, as illustrated in Table 5 and Figure 11, where the homogenisation results are plotted against relative density. A slight discrepancy can be observed in the Poisson’s ratio for the RUCs at a relative density of 10%, amounting to only 1.3%. This difference appears more pronounced due to the scale used to present the results.

Table 5.

Homogenisation results for F-RD shape.

Table 5.

Homogenisation results for F-RD shape.

| Source |

|

|

|

|

| FEM |

0.1 |

0.042 |

0.023 |

0.748 |

| MSG |

0.1 |

0.041 |

0.023 |

0.741 |

| FEM |

0.5 |

0.330 |

0.295 |

0.826 |

| MSG |

0.5 |

0.330 |

0.296 |

0.826 |

Figure 11.

Normalised effective elastic properties of F-RD as a function of relative density: (a) Normalised effective Young’s modulus , (b) Normalised effective shear modulus , (c) Normalised effective Poisson’s ratio .

Figure 11.

Normalised effective elastic properties of F-RD as a function of relative density: (a) Normalised effective Young’s modulus , (b) Normalised effective shear modulus , (c) Normalised effective Poisson’s ratio .

However, unlike all the structures considered so far, the F-RD shape shows a positive trend with respect to a higher relative density not only with the elastic Young’s modulus and shear modulus, but also the Poisson’s ratio.

Looking at the directional distribution of the Young’s modulus in Figure 12, the F-RD structure shows the highest anisotropy, having the biggest difference between the minimum and maximum Young’s modulus at low density. However, at high densities, the stiffness distribution becomes more uniform. As most TPMSs, the F-RD is the stiffest along the coordinate axes.

Figure 12.

Elastic Young’s modulus distribution of F-RD TPMS at different relative densities, RUC at: (a) and (b) .

Figure 12.

Elastic Young’s modulus distribution of F-RD TPMS at different relative densities, RUC at: (a) and (b) .

4. Conclusions

In this paper, a study was conducted to compare the mechanical homogenisation of Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces, using two different methods: the Finite Element Method and the Mechanics of Structure Genome. The homogenisation analysis was focused on the Representative Unit Cells of four TPMS topologies: gyroid, diamond, PMY, and F-Rhombic Dodecahedron (F-RD). The first two were chosen as they have already been explored extensively in literature, allowing for a validation of the results obtained in this paper. Whereas, the last two topologies were chosen due to the lack of information about their effective elastic properties, allowing us to fill this gap in the literature.

The main parameter that was varied when studying the mechanical behaviour of the TPMS topologies was the relative density, in a range between 10% and 50%. In all the different TPMS configurations presented in this paper, both the FEM and MSG methods have produced results that match very closely.

Through the analysis of the elastic effective properties, it has been shown that all TPMSs have higher Young’s modulus and shear modulus with increasing relative density. The opposite trend can be seen with the Poisson’s ratio for all TPMSs apart from the F-RD structure. The distribution of the directional Young’s modulus was also investigated relative to the amount of volume. It was seen that at low densities, TPMS structures can show different levels of anisotropy based on the topology chosen. The gyroid and the PMY structures show a spherical distribution of the stiffness, indicating high isotropy. On the other hand, the diamond and the F-RD are highly anisotropic at low densities. However, for all the shapes, as the volume increases, the stiffness distribution becomes more isotropic, approaching that of a sphere.

With the results obtained, it was shown that the MSG method can reliably predict the effective elastic properties, reproducing the same values as those obtained with the FEM approach. It achieves this while providing intrinsic computational advantages: unlike the FEM-based RUC analysis, which requires multiple system factorisations to compute the full stiffness matrix, the MSG method performs a single factorisation followed by multiple back-substitutions.

This study focused on the homogenisation of mechanical properties; however, the approaches presented are not limited to this domain. The effective thermal properties of TPMS structures could also be investigated to further compare the performance of the two methods. Moreover, the TPMS topologies analysed here do not represent the full range of existing geometries, and a more extensive study could provide broader insights. Finally, only simulation results were compared in this work, but valuable information could be gained through experimental testing to assess how accurately these methods can predict the real-world mechanical behaviour of architected metamaterials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.M., G.G., Y.K., L.B., L.K., and J.Y.; methodology, S.M., G.G. and Y.K.; software, Y.K.; validation, S.M., Y.K. and G.G.; formal analysis, S.M. and Y.K.; investigation, S.M., G.G., Y.K., L.B., L.K., and J.Y.; data curation, S.M., Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M., G.G. and Y.K.; writing—review and editing, G.G., Y.K., L.B., L.K., and J.Y.; visualisation, S.M.; supervision, G.G., Y.K, L.B., and J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

References

- Schwarz, H.A. Gesammelte Mathematische Abhandlungen: Erster Band; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Neovius, E.R. Bestimmung zweier speciellen periodischen Minimalflächen, auf welchen unendlich viele

gerade Linien und unendlich viele ebene geodätische Linien liegen; Frenckell: Helsingfors, 1883.

- Schoen, A.H. Infinite periodic minimal surfaces without self-intersections. NASA Technical Report C-98,

NASA Electronics Research Center, May 1970.

- Han, L.; Che, S. An overview of materials with triply periodic minimal surfaces and related geometry: from biological structures to self-assembled systems. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, M.C.; Simsek, U.; Ozdemir, M.; Gayir, C.E.; Sendur, P. Innovative vibration control of triply periodic minimum surfaces lattice structures: a hybrid approach with constrained layer damping silicone–viscoelastic layer integration. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2201851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Huang, X.; Kaewunruen, S. Experimental investigations into nonlinear dynamic behaviours of triply periodical minimal surface structures. Compos. Struct. 2023, 323, 117510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, W.; Chen, H.; Che, S.; Han, L. Mechanical properties of 3D-printed polymeric cellular structures based on bifurcating triply periodic minimal surfaces. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2402507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashfi, M.; Nourbakhsh, S.H.; Amiripour, A.; Lim, H.J. Constrained functionally graded gyroid structure for tunable energy absorption. Mater. Des. 2025, 258, 114693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ketan, O.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K. Multifunctional mechanical metamaterials based on triply periodic minimal surface lattices. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1900524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, U.; Arslan, T.; Kavas, B.; Gayir, C.E.; Sendur, P. Parametric studies on vibration characteristics of triply periodic minimum surface sandwich lattice structures. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, L. Vibration isolation and quasi-static compressive responses of curved gyroid metamaterials fabricated by selective laser sintering. Eng. Struct. 2025, 325, 119453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Mu, Y.; Pan, B.; Li, G.; Shao, L.; Du, J.; Jin, Y. Mechanical and biological properties of enhanced porous scaffolds based on triply periodic minimal surfaces. Mater. Des. 2022, 219, 110803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhadi, H.S.; Mian, A. Effect of strut length and orientation on elastic mechanical response of modified body-centered cubic lattice structures. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2019, 233, 2219–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Feih, S.; Daynes, S.; Chang, S.; Wang, M.Y.; Wei, J.; Lu, W.F. Energy absorption characteristics of metallic triply periodic minimal surface sheet structures under compressive loading. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 23, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refai, K.; Montemurro, M.; Brugger, C.; Saintier, N. Determination of the effective elastic properties of titanium lattice structures. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2020, 27, 1966–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, E.A.; Béraud, N.; Montemurro, M.; Pourroy, F.; Villeneuve, F. Effective elastic and strength properties of triply periodic minimal surfaces lattice structures by numerical homogenization. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 9571–9583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, S.; Jing, K.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; He, G. Study on isotropic design of triply periodic minimal surface structures under an elastic modulus compensation mechanism. Compos. Struct. 2024, 342, 118266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Liu, A.; Peng, H.; Tian, L.; Liu, J.; Lu, L. Mechanical property profiles of microstructures via asymptotic homogenization. Comput. Graph. 2021, 100, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W. A unified theory for constitutive modeling of composites. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 2016, 11, 379–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MathWorks. MATLAB, Version R2025a; The MathWorks, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Brakke, K.A. The Surface Evolver, Version 2.70; Susquehanna University: Selinsgrove, PA, USA, 2023. Available online: http://facstaff.susqu.edu/brakke/evolver/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Khan, K.A.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K. Modeling time and frequency domain viscoelastic behavior of architectured foams. J. Eng. Mech. 2018, 144, 04018029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altair Engineering Inc. Altair HyperMesh, Version 2025; Altair Engineering Inc.: Troy, MI, USA, 2025. Available online: https://altairhyperworks.com/product/HyperMesh (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Geuzaine, C.; Remacle, J.-F. Gmsh, Version 4.12; Université de Liège: Liège, Belgium, 2024. Available online: https://gmsh.info/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Al-Ketan, O.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K. MSLattice: A free software for generating uniform and graded lattices based on triply periodic minimal surfaces. Mater. Des. Process. Commun. 2021, 3, e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchais, K.; Chemisky, Y.; d’Esparbès, R.; Guevara, M.R.; Legerstee, Y.; sudeep5511. 3mah/microgen: V1.3.2; Zenodo, 2025. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14643858 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Geuzaine, C.; Remacle, J.-F. Gmsh: A three-dimensional finite element mesh generator with built-in pre- and post-processing facilities. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2009, 79, 1309–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W. An introduction to micromechanics. Composite Materials and Structures in Aerospace Engineering 2016, 828, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, E.J. Finite Element Analysis of Composite Materials using Abaqus®, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsawa, Y.; Tiem, S.; Yu, W.; Addiego, F.; Giunta, G. A micromechanics approach for effective elastic properties of nano-composites with energetic surfaces/interfaces. Compos. Struct. 2017, 159, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsawa, Y.; Karatrantos, A.V.; Yu, W.; Ruch, D. A micromechanics approach for the effective thermal conductivity of composite materials with general linear imperfect interfaces. Compos. Struct. 2018, 200, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G. 3D Homogenization of Cellular Materials. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/67457-3d-homogenization-of-cellular-materials (accessed on 1 September 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).