Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Indicators of Population Dynamics

- o

- Ratio of yearlings in the bag

- o

- Coefficient of reproduction

- o

- Reproduction index

- o

- Sex ratio

- o

- Population increase

2.3. Semi-Natural Vegetation Model Area

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

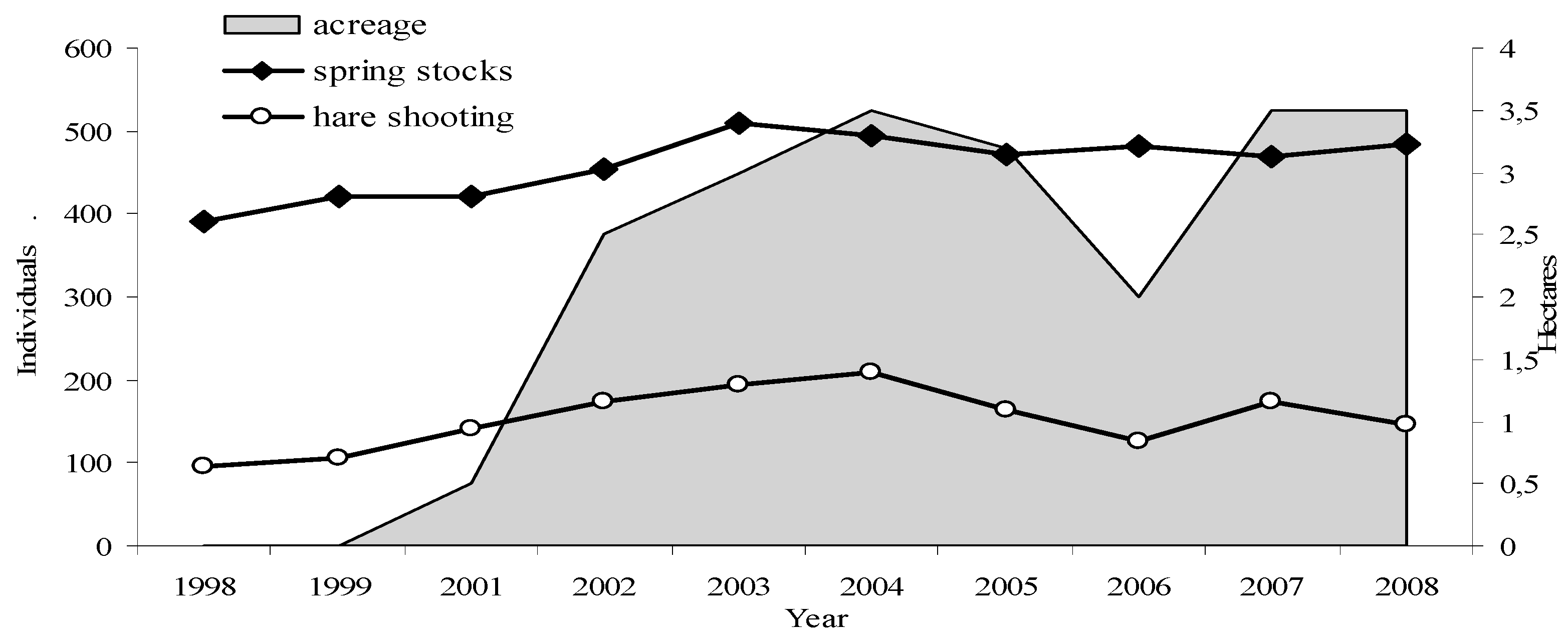

3.1. Hare Population’s Dynamic

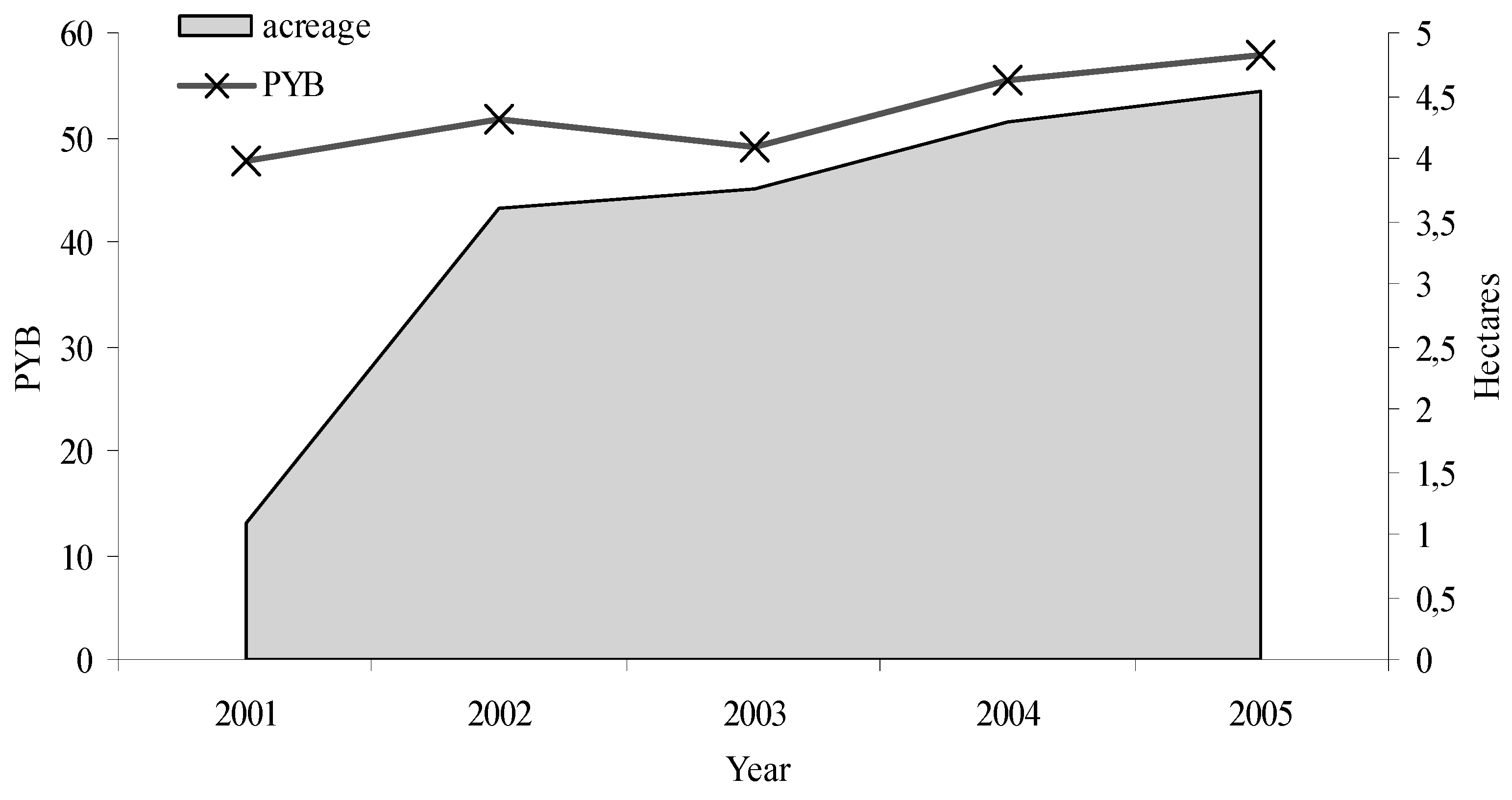

3.2. Improvement of Environment for Hares

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, R.K.; Vaughan Jennings, N.; Harris, S. A quantitative analysis of the abundance and demography of European hares Lepus europaeus in relation to habitat type, intensity of agriculture and climate. Mamm Rev 2005, 35, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Jansson, G.; Pehrson, Å. The recent expansion of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) in Sweden with possible implications to the mountain hare (L. timidus). Eur J Wildl Res 2007, 53, 125–130. ttps://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-007-0086-2.

- Tsokana, C.N.; Sokos, C.; Giannakopoulos, A.; Birtsas, P.; Valiakos, G.; Spyrou, V; Athanasiou, L.V.; Rodi Burriel, A. European Brown hare (Lepus europaeus) as a source of emerging and re-emerging pathogens of Public Health importance: A review. Vet Med Sci 2020, 00, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Treml, F.; Pikula, J.; Bandouchova, H.; Horakova, J. European brown hare as a potential source of zoonotic agents. Vet Med 2007, 52(10), 451–456. [CrossRef]

- Bartel, M.; Grauer, A.; Greiser, G.; Klein, R.; Muchin, A.; Straus, E.; Wenzelides, L. Winter A Wildtierinformationssystem der Länder Deutschlands. In proceedings of Status und Entwicklung ausgewählter Wildtierarten in Deutschland (2002–2005), Jahresbericht 2005. Deutscher Jagdschutz – Verband e.V., Bonn, 2006.

- Grauer, A, Greiser G, Klein R, Muchin A, Strauss E, Wenzelides L, Winter A Wildtierinformationssystem der Länder Deutschands. In Proceedings of Status und Entwicklung ausgewählter Wildtierarten in Deutschland, Jahresbericht 2007. Deutscher Jagdschutz – Verband e.V., Bonn, 2008.

- Dubinský, P.; Vasilková, Z.; Hurníková, Z.; Miterpáková, M.; Slamečka, J.; Jurčík, R. Parasitic infections of the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas, 1778) in south-western Slovakia. Helminthologia 2010, 47(4), 219–225. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.J.; Fletcher, M.R.; Berny, P. Review of the factors affecting the decline of the European brown hare, Lepus europaeus (Pallas, 1778) and the use of wildlife incident data to evaluate the significance of paraguat. Agr Ecosyst Environ 2000, 79, 95-103. [CrossRef]

- Amori, G.; Contoli, L.; Nappi, A. In Mammalia II: Erinaceomorpha, Soricomorpha, Lagomorpha, Rodentia. Fauna d’Italia. Edizioni Calderini de Il Sole-24 Ore, Italy, 2008, Volume 44.

- Schmidt, N.M.; Asferg, T.; Forchhammer, M.C. Long-term patterns in European brown hare population dynamics in Denmark: effects of agriculture, predation and climate. BMC Ecol 2004, 4, 15. [CrossRef]

- Slamečka, J.; Grácová, M.; Gašparík, J.; Hell, P.; Massányi, P. Damages in agriculture caused by European hare (Lepus europaeus) and protection against them. In proceedings of 3rd World Lagomorph Conference, Abstract Book. Morelia, , Michoacán de Ocampo, México, p 137, 10–13 November 2008.

- Cattadori, I.M.; Haydon, D.T.; Thirgood, S.J.; Hudson, P.J. Are indirect measures of abundance a useful index of population density? The case of red grouse harvesting. Oikos 2003, 100(3), 439–446. [CrossRef]

- Pintur, K.; Popovic, N.; Alegro, A.; Severin, K.; Slavica, A.; Kolic, E. Selected indicators of brown hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas, 1778) population dynamics in northwestern Croatia. Vet Arhiv 2006, 76, S199-S209.

- Slamečka, J.; Hell, P.; Jurčík, R. Brown hare in the Westslovak Lowland. Acta Sci Nat Brno 1997, 31(3–4), 58–67.

- Hell, P.; Rášo, V.; Slamečka, J. Contribution to knowing the effect of landscape vegetation on field game in agrarian country (in Slovak). Folia venatoria 2003, 33, 63–77.

- Suchentrunk, F.; Willing, R.; Hartl, G.B. On eye lens weights and other criteria of the Brown hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas, 1778). Z Säugetierkunde 1991, 56, 365–374.

- Slamečka, J.; Hell, P.; Gašparík, J.; Rajský, M. Súčasný stav a možnosti ekologizácie životného prostredia zveri v agrárnej krajine. In proceedings of Životné prostredie a poľovníctvo, Zborník referátov z medzinárodnej konferencie, Levice. SCPV Nitra, Slovakia, pp 23–34, 25 March 2006.

- Hell, P.; Slamečka, J.; Flak, P. Einflus der Witterungsverhältnisse auf die Strecke und den Zuwachs des Feldhasen in der südslowakischen Agrarlandschaft. Beitr Jagd Wildforsch 1997, 22,165-172.

- Nyenhuis, H. Der Einfluss des Wetters auf die Besatzschwankungen des Feldhasen (Lepus europaeus). Z Jagdwiss 1995, 41, 182-187. [CrossRef]

- Kolar, B. Večina uplenjenih zajcev je bila starejših od 2 let. Lovec 2003, 11, 519-521.

- Krupka, J.; Dziedzic, R.; Lipecka, C. Ocena biometryczna zajaca (Lepus europaeus Pallas) na Lubelszczyznie. In proceedings of Zeszyty Problemowe Postepow Nauk Rolniczych, Warszava, Poland, Panstwowe Wydawn, Naukowe, 259, 211-216, 1981.

- Bensinger, S. Untersuchungen zur Reproduktionsleistung von Feldhäsinnen (Lepus europaeus PALLAS, 1778), gleichzeitig ein Beitrag zur Ursachenfindung des Populationsrückganges dieser Wildtierart. Inaugural-Dissertation. Veterinärmedizinische Fakultät, Universität Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany, 2002.

- Marboutin, E.; Bray, Y.; Peroux, R.; Mauvy, B.; Lartiges, A. Population dynamics in European hare and sustainable harvest rates. J Appl Ecol 2003, 40, 580-591.

- Semizorová, I. Die Hasenproduktion unter den gegenwärtigen Bedingungen in Tschechoslowakei. Beitr Jagd- und Wildf 1986, 14, 204-209.

- Raczynski, J. Studies on the European Hare. V. Reproduction. Acta Theriol 1964, 9, 305-352. [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, M. Population dynamics of the European hare Lepus europaeus Pallas, 1778 in Central Poland. Acta Theriol 1991, 36, 267-274. [CrossRef]

- Šelmić, V.; Đaković, D.; Novkov, M. Istraživanja realnog prirasta zečijih populacija i mikropopulacija u Vojvodini. Godišnji izveštaj o naučnoistraživačkom radu u organizaciji LS Vojvodine, Novi Sad. pp.3-9, 1999.

- Semizorová, I.; Švarc, J. Zajíc [Hare]. SZN, Praha, pp.168, 1987.

- Vodňanský, M. In Sommer wird es eng. Die Pirsch 2003, 8, 8–9.

- Hutchings, M.R.; Harris, S. The current status of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) in Britain. School of Biological Science, University of Bristol, Woodland Road, Btistol BS8 1UG. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, 1996, 42-52.

- Reichlin, T.; Klansek, E.; Hackländer, K. Diet selection by hares (Lepus europaeus) in arable land and its implications for habitat management. Eur J Wildl Res 2006, 52, 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Rühe, F.; Fischbeck, I.; Rieger, A. Zum Einfluss von Habitatmerkmalen aud die Populations dichte von Feldhasen (Lepus europaeus PALLAS) in Agrargebieten Norddeutschlands. Beitr zur Jagd- und Wildf 2004, 29, 333–342.

- Smith, R.K.; Jennings–Vaughan, N.; Robinson, A.; Harris, S. Conservation of European hares Lepus europaeus in Britain: is increasing habitat heterogeneity in farmland the answer? J Appl Ecol 2004, 41, 1092–1102. [CrossRef]

- Tapper, S.C.; Barnes, F.W. Influence of farming practice on the ecology of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus). J Appl Ecol 1986, 23, 39–52. [CrossRef]

- Genghini, M.; Capizzi, D. Habitat improvement and effects on brown hare Lepus europaeus and roe deer Capreolus capreolus: a case study in northern Italy. Wildl Biol 2005, 11(4), 319–329. [CrossRef]

- Marboutin, E.; Aebischer, N. Does harvesting arable crops influence the behaviour of the European hare Lepus europaeus? Wildl Biol 1996, 2, 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Meriggi. A.; Alieri, R. Factors affecting brown hare density in northern Italy. Ethol Ecol & Evol 1989, 1, 255–264. [CrossRef]

- Paniek, M.; Kamieniarz, R. Relationships between density of brown hare Lepus europaeus and landscape structure in Poland in the years 1981–1995. Acta Theriol 1999, 44, 67–75.

- Hell, P.; Plavý, R.; Slamečka, J.; Gašparík, J. Losses of mammals (Mammalia) and birds (Aves) on roads in the Slovak part of the Danube Basin. Eur J Wildl Res 2005, 51, 35–40. [CrossRef]

| Male | Female | SE | p-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juvenile | 3.83 | 3.85 | 0.014 | 0.602 |

| Adult | 4.21a | 4.32b | 0.077 | 0.049 |

| 1987-1991 | 1992-1997 | 1998-2002 | 2003-2007 | 2008-2012 | 2013-2017 | 2018-2023 | SE | p-Value* | Corr. Coeff. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1154a | 505b | 320c | 386c | 277cd | 271cd | 206d | 234.7 | .050 | -0.753 |

| Njuv | 584a | 250b | 164bc | 196bc | 113c | 117c | 83c | 119.2 | .043 | -0.769 |

| PYB | 49a | 50a | 51a | 46ab | 41ab | 45ab | 37b | 2.410 | .021 | -0.830 |

| R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.098 | .065 | -0.725 |

| r | 2.05 | 2.30 | 2.15 | 2.03 | 1.52 | 1.70 | 1.26 | 0.185 | .021 | -0.827 |

| Si | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.48a | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.012 | .497 | -0.311 |

| adult female | 283a | 115b | 78c | 96bc | 76c | 78c | 63c | 56.95 | .050 | -0.739 |

| males | 558a | 247b | 162c | 197c | 125cd | 131cd | 97d | 104.6 | .032 | -0.795 |

| total females | 596a | 258b | 157c | 201bc | 132c | 140c | 109d | 116.6 | .039 | -0.779 |

| % adult females in bag | 25.04c | 22.58d | 24.57c | 25.89c | 27.87b | 27.85b | 31.26a | 1.170 | .010 | 0.876 |

| % young fem on total female | 48b | 44c | 50b | 53ab | 58a | 55ab | 57a | 2.697 | .012 | 0.863 |

| PI% | 40a | 40a | 44a | 40a | 19c | 31b | 16c | 6.920 | .046 | -0.732 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).