1. Introduction

The Iberian wild goat

Capra pyrenaica is an endemic Iberian Caprinae whose populations today occupy many areas of the Iberian Peninsula. After the extinction of two subspecies,

C. p. lusitanica, in the 19th century and

C. p. pyrenaica in the year 2000 [

1],

C. p. victoriae, occupies the center and NW of the peninsula and

C. p. hispanica the S and E [

2]. The bases of this taxonomic classification were the body size, the shape and size of the horns, and the pattern of the black coat in males [

3]. Currently, various studies point the need for a new classification [

4,

5,

6], in which the existence of subspecies is not accepted by specialists [

2]. In addition, the species entity of the extinct Pyrenean wild goat rather than a subspecies should be considered a species (it would become

Capra pyrenaica Schinz, 1838), and makes the correct current name for the living Iberian wild goats

Capra hispanica Schimper, 1948 and not

Capra pyrenaica [

7]. Currently, most of the populations are expanding throughout their range [

2].

It can be described as a gregarious, polygynous species with marked sexual dimorphism, which is characterized by its high adaptability to different types of environment. It inhabits from sea level to 3000 m and the only characteristics common to the habitat of all its populations is the dependence on the slope or the rocky substrate [

8,

9,

10,

11].

It has been a species very persecuted by man, either indirectly through the pressure of livestock or through indiscriminate hunting, reducing dramatically its numbers and populations. These population bottlenecks have resulted in one of the main causes of threat that the species currently faces: the low genetic variability of its populations, which produces a high vulnerability to diseases [

12], particularly sarcoptic mange

Sarcoptes scabiei. It is considered as Least Concern (LC) by the IUCN and is a huntable species in Spain, but not in Andorra, France and Portugal. Its exclusive hunt produces important revenues to local hunting grounds and private owners [

13].

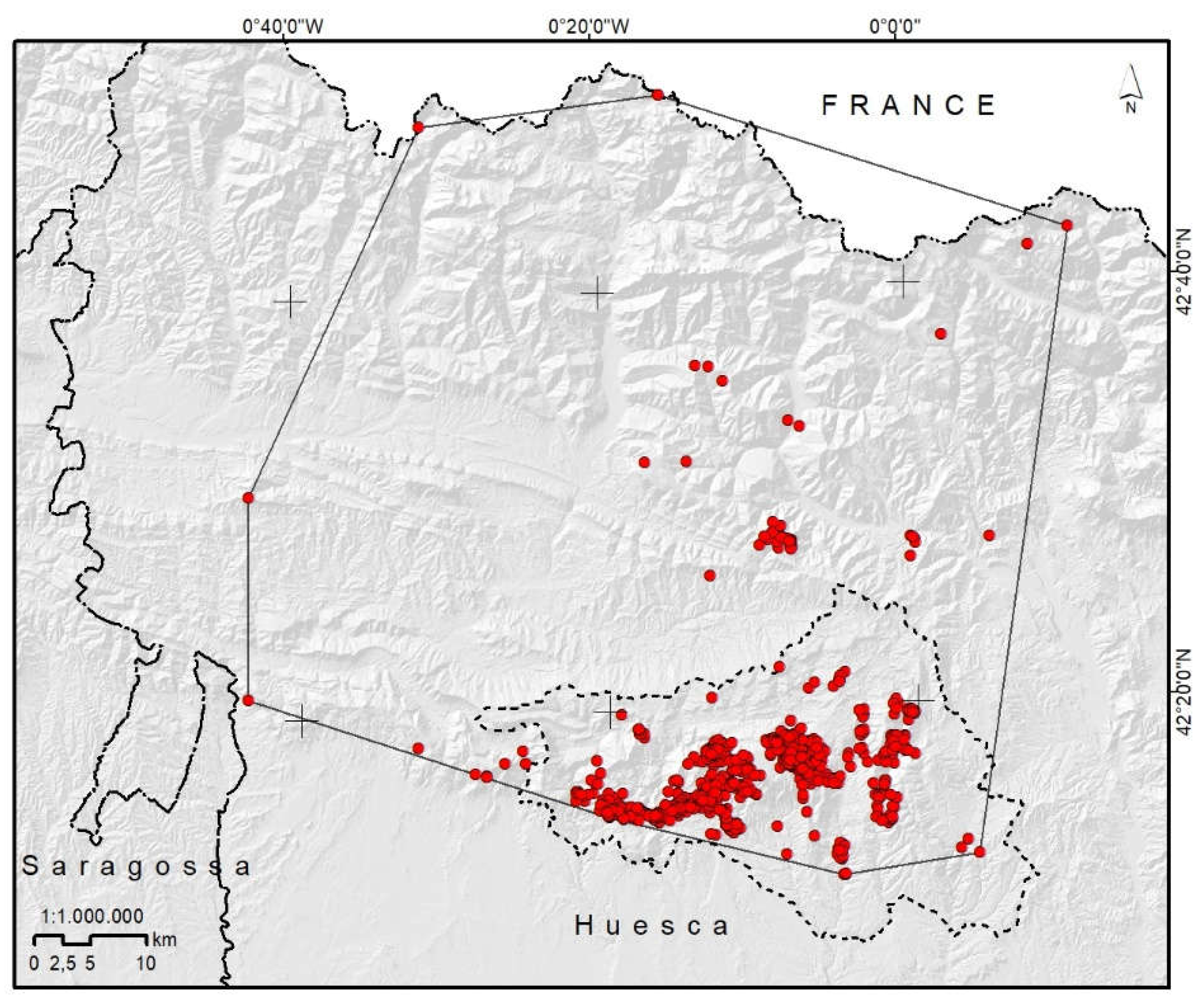

At the end of the seventies of the last century (1977-80) an indeterminate number of Iberian wild goats (more than 20) were transferred from the Sierra de Cazorla (Region of Andalusia) in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, to a hunting enclosure in the current Sierra and Cañones de Guara Natural Park (GNP) [

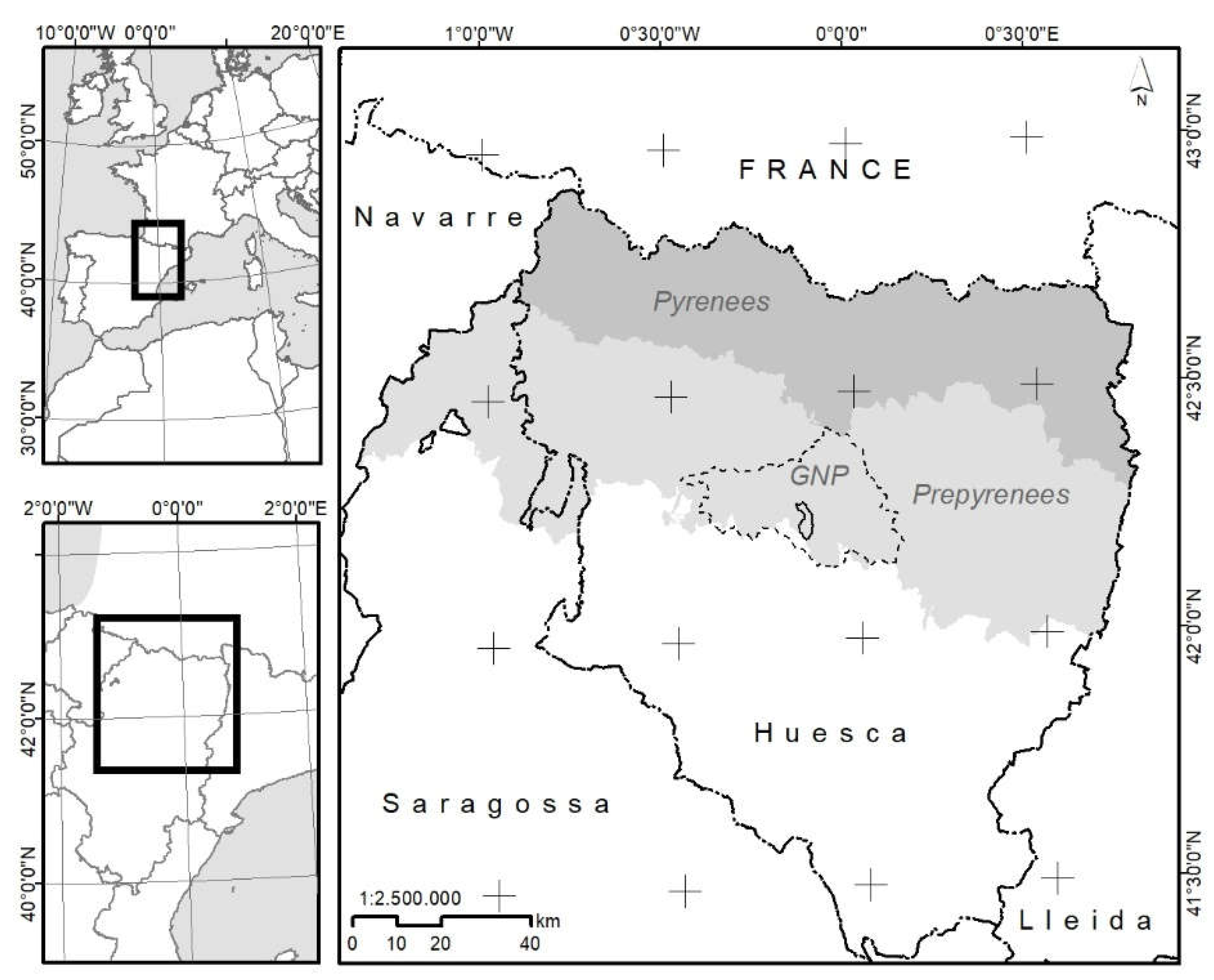

14], Region of Aragon (

Figure 1). If there have been more releases and if they were of different genetic origin, remains unknown. Since at least the nineties a population established outside the enclosure and from 2006 onwards it is monitored annually.

From 2014 to 2022, the Region of Madrid has sold Iberian wild goats to the Parc National des Pyrénées (PNP), to the Parc Naturel Régional des Pyrénées Ariégeoises (PNA), both in France, and to Andorra [

16]. These animals came originally from the Central Mountain range of the Iberian Peninsula, so they had a different genetic origin. Some of the individuals released in France have spread to Spain and established there. Releases are expected to continue in the coming years.

The objective of this work is to describe the demographic characteristics and the colonization process of the Iberian wild goat in the Aragonese Pyrenees between 2006 and 2022.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study area was the GNP and as the result of the expansion, the rest of the Aragonese Pyrenees (

Figure 1).

GNP (42 ° 16′ 38″ N; 0 ° 7′ 59 ″ W) covers a 40-km-long S Prepyrenean E-W mountain range of 81,494 ha, rangings between 430 m and 2077 m. The landscape has steep slopes and rough relief. Half of the surface consists of shrubs (Echinospartum horridum, common juniper Juniperus communis, common box Buxus sempervirens), one fourth consists of forest (mainly holm oak Quercus ilex, Scots pine Pinus sylvestris, Austrian pine Pinus nigra, downy oak Quercus cerrioides, mountain pine Pinus uncinata and beech Fagus sylvatica, in decreasing order of importance), and one-fourth is rock. Hunting is not allowed in about one-fourth of the park, and the remainder comprises hunting grounds managed by local hunters. One fenced hunting ground was the origin of the wild goats escaped. The main game animal is wild boar Sus scrofa and over 1,000 are harvested each year. The Iberian wild goats co-exists with other huntable wild ungulates (roe deer Capreolus capreolus, red deer Cervus elaphus, European mouflon Ovis aries, fallow deer Dama dama) and feral goat Capra hircus.

2.2. Field Survey

Field surveys were undertaken by rangers of the Regional Government of Aragon and ourselves with the occasional help of volunteers. Three kinds of samplings were done filling up a specific sheet: occasional sightings, additional surveys and coordinated survey. Occasional sightings reported animals seen randomly which represented valuable data (new areas, large groups). Additional surveys were done specifically to explore new areas or confirm testimonies. Testimonies of non-professionals played a key role in the localization of new occupied areas.

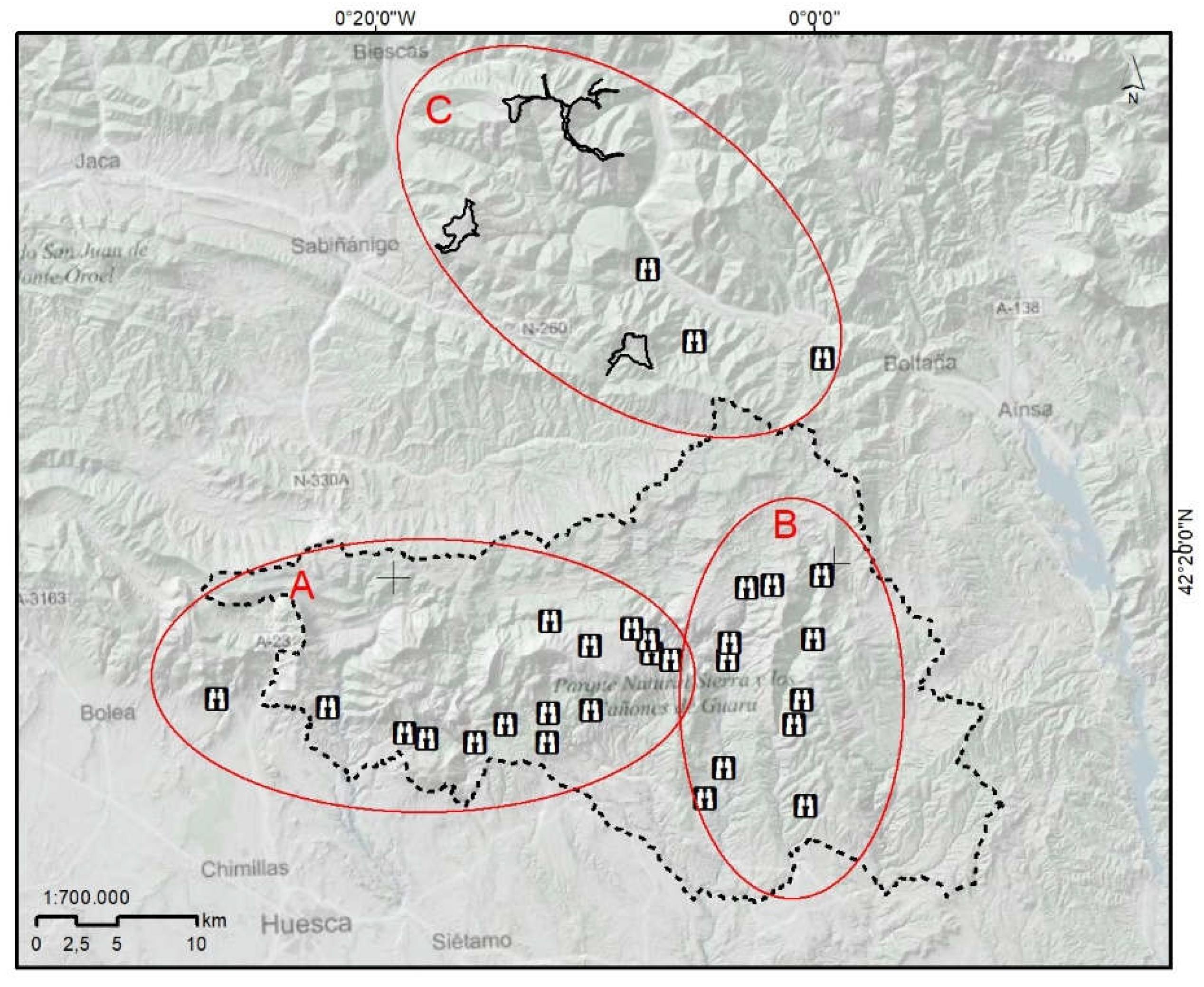

For the coordinated survey we performed vantage points [

17,

18] and itineraries (block counts) to localize Iberian wild goats using binoculars and spotting scopes. Vantage points were placed considering testimonies on the presence of the species. Surveys were done when Iberian wild goats were more active [

19] during 3 h after dawn (2006-2022) and also in late afternoon (2006 and 2007). The vantage points were selected considering spots with good accessibility and visibility (

Figure 2).

Sex and age of the animals were recorded, assigning individuals assigned to one of the following age-sex classes: kids, 1- and 2-year-old yearlings, adult females, young males (3 – 6 years), middle age males (7-10 years), and old males (> 10 years). This allowed to describe population structure, productivity (kids/adult females) and sex-ratio (adult males/adult females).

A pilot survey of the rut was undertaken in 2006. Between 2007 and 2012 four annual surveys were undertaken (before parturition, April; after parturition, June; before rut, October, and during rut, November-December). Due to economic restrictions between 2013 and 2017 three annual surveys were done (after parturition, before rut and rut). Since 2018 and because of population increase the number of annual surveys was reduced to after parturition and rut, but the number of fixed points were increased, Iberian wild goats were counted from 29 vantage points and five itineraries (

Figure 2).

Three main subpopulations areas were defined: Guara, Balced and Sobrepuerto (

Figure 2). For the estimation of the minimum number of living animals for each of them we combined the results of all the counts in each annual survey. This allowed to calculate the trend.

2.3. Trend

We used the change in the annual number of Iberian wild goats as a function of time and analyzed it using Poisson regression [

20,

21]. The dependent variable was a count that followed the Poisson distribution. For this, we defined a generalized linear model fit with the GLM procedure of R [

21]. The response variable given by the annual count of Iberian wild goats had a Poisson error distribution, and a natural log link function for the exponential growth model. The parameter b can be interpreted as r or the intrinsic rate of increase, and lambda λ as the annual population growth rate coming from the r neperian antilog.

2.4. Cartography

To carry out the cartography that illustrates the study area, various thematic layers of digital cartography provided by the Government of Aragon were used. From these layers, some parameters have also been calculated using a Geographic Information System (GIS). The resolution with which we have worked with the layers in Raster format were defined by the pixel size of the digital elevation model (DEM), 20 m on each side. The slope was calculated from that DEM of the study area. The maps of the itineraries were made using the 1:25,000 scale sheets of the National Geographic Institute in digital format, which occupy the study area, and also using orthoimages belonging to the National Plan of Aerial Orthophotography of the Ministry of Development of Spain (2006). The digitization of the goat locations has been carried out directly on the screen on these maps or by calculating the coordinates with the help of the orthoimages of the SIGPAC Viewer.

2.5. Population Estimation

The viewshed area was calculated, with a limit of 2,500 m, for each of the vantage points (VP) located within the GNP. To calculate the total area, the existing overlaps in the individual VP were eliminated. The average density after the parturition and during the rut was calculated, and it was multiplied by the area of the PNG with a slope >30 % (28 966 ha), following the methodology proposed by Prada et al. 2019 [

22]. To this estimation we added the results of block counts in Sobrepuerto and testimonies of animals localized at great distances.

2.6. Colonizing Process

The colonization process is described from the information generated by the testimonies and its verification as well as that of the participants in the survey (occasional sightings). The annual Maximum Convex Polygon (MCP) was calculated annually including all the sightings.

2.7. Coordination Meetings

Every year during the spring and before the beginning of the field work, the follow-up was the subject of an annual meeting for coordination and presentation of results. The attendees were: rangers, technicians and ourselves. Demographic and sanitary results were discussed together with the field work calendar.

3. Results

3.1. Trend

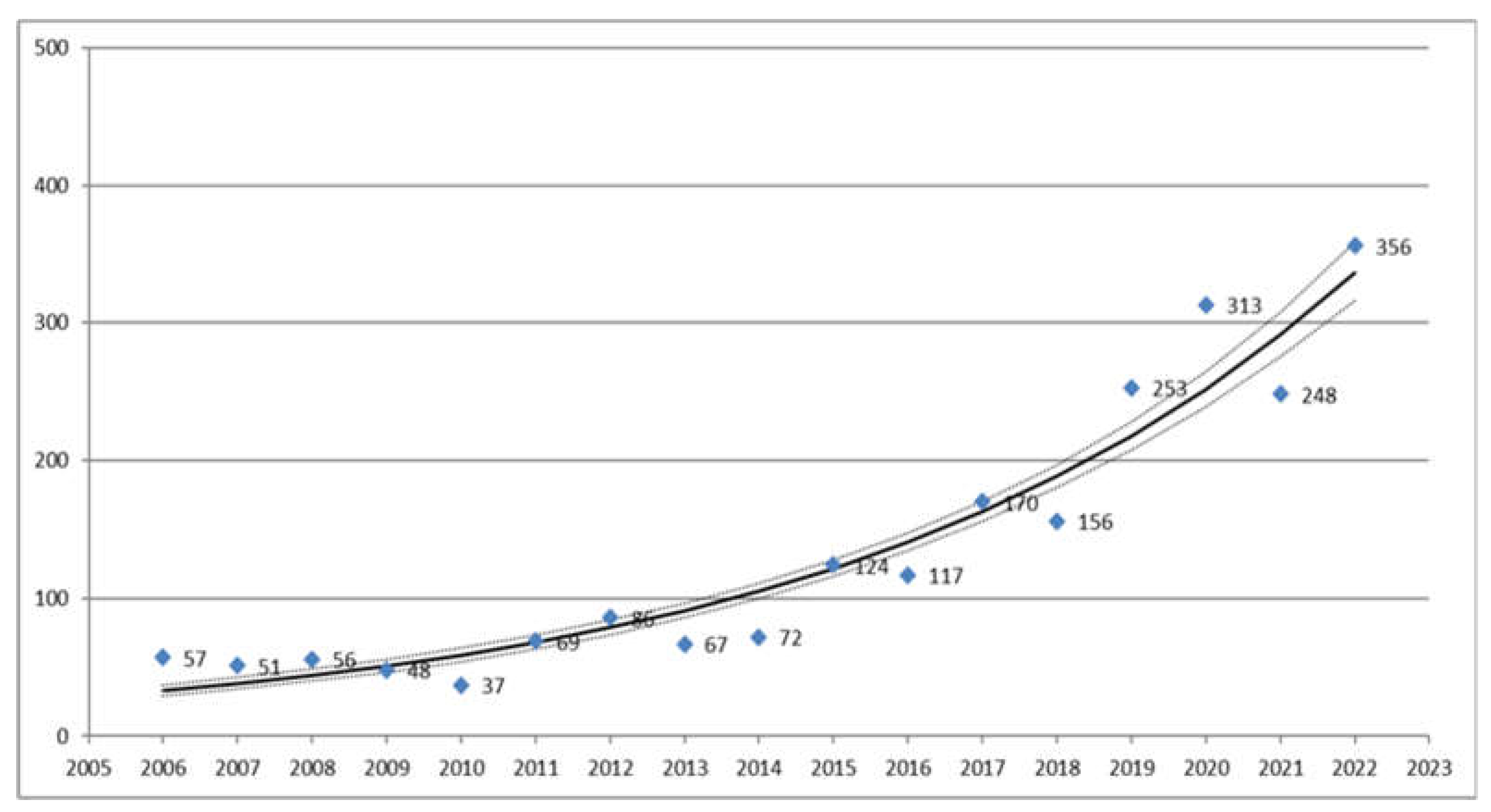

The average annual growth rate (λ), calculated with the minimum number of Iberian wild goats observed from the vantage points in the GNP and surrounding areas, was 15.6% (95% CI: 14.5-16.8) (

Figure 3).

3.2. Population Parametres

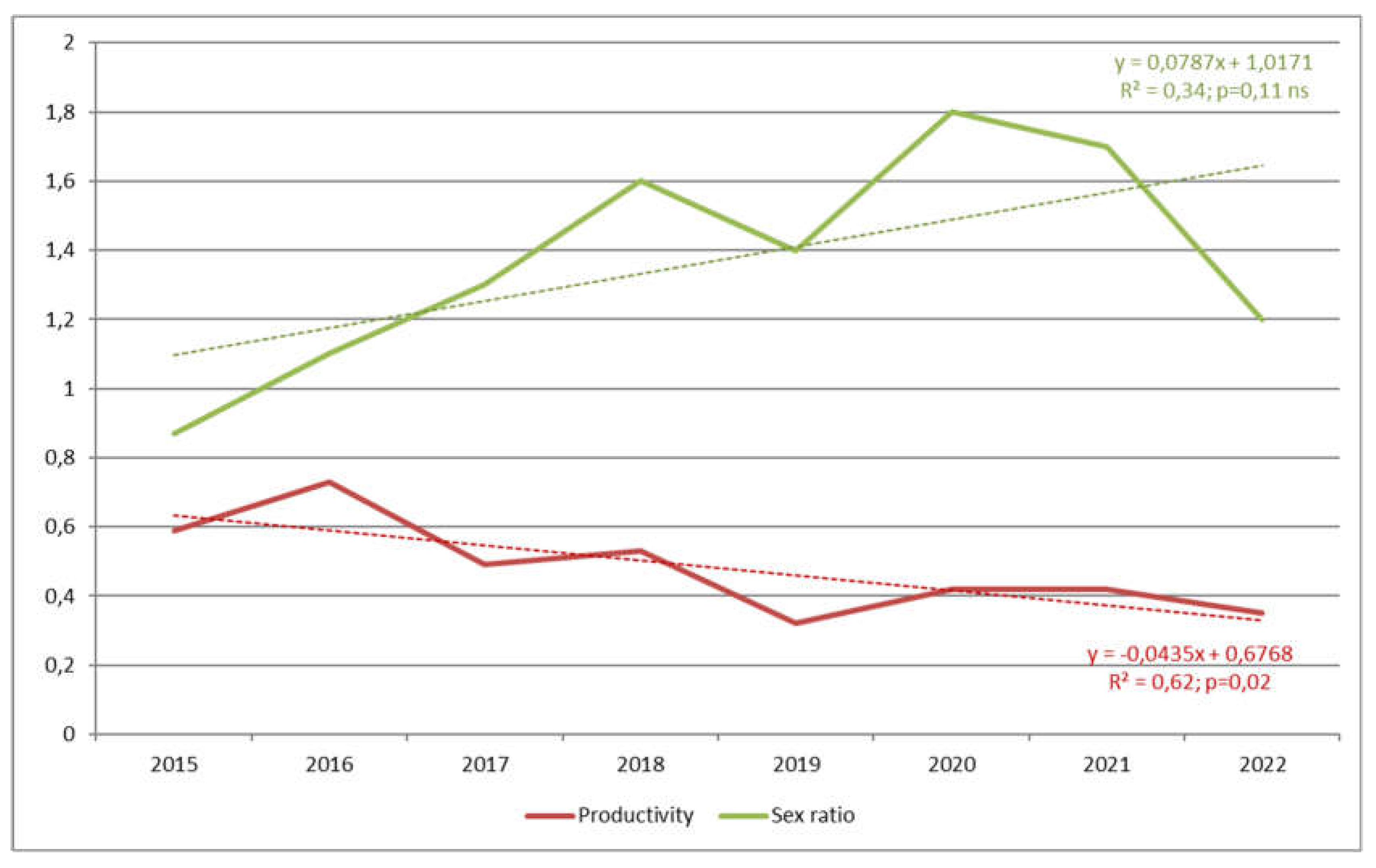

Table 1 shows the main demographic parameters and

Figure 4 the trend of sex ratio (without significant trend, around 1.4) and productivity (decreasing significantly), since 2015, when the population was higher than 100 animals. The MCP surface has increased steadily since 2015 due to the presence of Iberian wild goats of French origin (

Figure 5).

3.2. Density Estimation for Iberian Wild Goat and Feral Goat

Between 2018 and 2022 we calculated for the GNP using the 25 vantage points truncating at 2,500 m of distance. The total sampled surface was 9,779 ha of its 47,638 ha (20%) with 289.66 km

2 of suitable habitat (slope over 30 %) (

Table 2).

3.3. Sympatry with Other Wild and Domestic Ungulates

Iberian wild goats form groups on their own but can coincide with other wild ungulates. This happens with animals living alone and also with normal herds during the rut (

Figure 6). In the first case, they can gather with cows

Bos taurus in summer pastures (1 case), domestic goats (1 young female), domestic goats and sheep (1 young male) or feral goats (1 young male, 2 cases). In the case of feral goats’ relation lasted several years in 1 case. No competence interactions were observed between domestic and Iberian wild goats.

3.4. Hybrids

A possible hybrid female with kid (

Figure 7) and the first record of a leucistic male for the species (

Figure 8) were observed.

3.5. Hunting Quota

In 2022 due to the population increase in number, a hunting quota of 20 Iberian wild goats was decided for the GNP.

4. Discussion

The demographic characteristics of Iberian wild goat living in southern Pyrenees appear to be in the range of the rest of populations of the species [

2]. It has increased in number and distribution, has contacted the population coming from France and it is the most abundant in the Pyrenees. The decrease of productivity could be due to the stabilization of the population in its main nucleus, the GNP. The expansion to the north of the population from the Iberian mountain range and the Middle Ebro Valley leaves both populations at less than 50 km so they will contact the near future, following a stepping stone dynamic [

11,

23,

24]. This will represent a mixture of at least three different genetic origins.

The existence of hybrids with domestic goats has been reported for Alpine ibex [

25] and recently for free Iberian wild goats [

26]. Even if this seems to be an old process due to the more than 7,000 years of sympatry, the existence of an abundant feral goat population, may represent a problem for the genetic integrity of Iberian wild goat in the Pyrenees [

15]. The control or eradication of ferals in the Pyrenees should represent a priority in order to favor the conservation and recovery of the Iberian wild goat [

27].

5. Conclusions

The population structure is comparable to that of other populations of the species. Productivity is stable, with annual oscillations, and the sex ratio does not vary significantly. Old males are scarce. The population is increasing in number and expanding and has already contacted the introduced wild goats from France. The Iberian wild goats of the Middle Ebro Valley are less than 50 km away and are also expanding, so both populations will contact in the near future.

Iberian wild goats coexist with domestic and feral domestic goats. There are hybrids of both species. Feral goats are more abundant than Iberian wild goats in GNP. This is a new and potentially important problem for Iberian wild goat genetic integrity. There is no information on the genetic characteristics of Iberian wild goats of the Aragonese Pyrenees, in terms of diversity, origin and domestic goat interbreeding.

This new dynamic situation deserves both national and international attention in order to promote coordinated efforts for its monitoring (demographic, sanitary, genetic) conservation and sustainable use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JH and AGS; methodology, JH and JHS.; software, AGS.; cartography, CP; formal analysis, AGS; field work, JH and AGS; resources, AGS; data curation, AGS; writing—original draft preparation, JH; writing—review and editing, JH, AGS, CP, RGG; project administration, AGS; funding acquisition, AGS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Government of Aragon through several consultancy projects from 2006 to 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data can be shared with other researchers upon request of collaboration.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the rangers, technicians and volunteers who have participated in the field work during this long period. Without them, the monitoring could have not been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- García-González, R.; Herrero, J. El Bucardo de los Pirineos: historia de una extinción. Galemys 1999, 11, pp. 17–26.

- García-González, R.; Herrero, J.; Acevedo, P.; Arnal, M.C.; Fernández de Luco, D. Iberian Wild Goat Capra pyrenaica Schinz, 1838. 2022. In: Corlatti, L., Zachos, F.E. (Eds); Terrestrial Cetartiodactyla. Handbook of the Mammals of Europe. Springer, Cham., Germany. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, Á. The subspecies of the Spanish ibex.. Proc Zool Soc London 1911, 66: pp. 963-977.

- Villalta M.J. ; Folch, J.L. ; Alabart, A. ; Fernández-Arias, A.. Taxonomic status and sex identification from single follicle hairs in endangered Pyrenean Ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica). Theriogenology 1997, 1,(47): 410.

- Manceau V. ; Crampe J.P. ; Boursot, P. ; Taberlet, P. Identification of evolutionary significant units in the Spanish wild goat, Capra pyrenaica (Mammalia, Artiodactyla). Anim Conserv 1999, 2, pp. 33-39. [CrossRef]

- García-González, R. Elementos para una filogeografía de la cabra montés ibérica (Capra pyrenaica Schinz, 1838). Pirineos 2011, 166, pp. 87–122. [CrossRef]

- García-González R.; Herrero, J. Which is the correct Latin name for the Iberian wild goat? Caprinae News 2022: pp. 12-14.

- Fandos P. La cabra montés (Capra pyrenaica) en el Parque Natural de Cazorla, Segura y Las Villas. Colección Técnica. Icona, Madrid. 1991, 176 p.

- Alados C.L.; Escós, J. Ecología y Comportamiento de La Cabra Montés y Consideraciones para su Gestión. CSIC, Madrid, Spain, 1996.

- Pérez J.M.; Granados, J.E.; Soriguer, R.C.; Fandos, P.; Marquez, F.J.; Crampe, J.P. Distribution, status and conservation problems of the Spanish ibex, Capra pyrenaica (Mammalia: Artiodactyla). Mammal Rev 2002, 32, pp. 26–39. [CrossRef]

- Lucas P.; Herrero, J.; Fernández-Arberas, O.; Prada, C.; García-Serrano, A, Saiz, H.; Alados, C.L. Modelling the habitat of a wild ungulate in a Mediterranean semi-arid environment of South-West Europe: small cliffs as key predictors for the presence of Iberian wild goat. J Arid Environ 2016, 129, pp. 56–6312.

- Granados J.E., R.C. Soriguer, J.M. Pérez, P. Fandos, J. García-Santiago. Capra pyrenaica Schinz, 1838, In: Palomo L.J.; J. Gisbert, J.C. Blanco, Eds. Atlas y Libro Rojo de Los Mamíferos Terrestres de España. Dirección General para la Biodiversidad-SECEM-SECEMU, Madrid, pp. 366–368, 2007.

- Herrero J.; Acevedo, P.; Arnal, M.C.; Fernández de Luco, D.; Fonseca, C.; García-González, R.; Pérez, J.M; Sourp, E. 2021. Capra pyrenaica (amended version of 2020 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T3798A195855497.

- Fandos París, P.; J. Granados Torres, E.; Prieto Yerro, P.; Cano-Manuel, F.J.; Pérez Jiménez, J. M., Soriguer Escofet, R.C. Evolución histórica de la cabra montés. In: Castillo-Contreras, R.; Fuentes-Rodríguez, E.; Villanueva, L.F.; Sánchez-García, C., Eds.. Cabra montés en España. Aspectos clave sobre su salud, genética, caza y gestión. Fundación Artemisan, Madrid, Spain, 2022.

- Herrero, J.; Fernández-Arberas O.; Prada C.; García-Serrano A.; García-González, R. An escaped herd of Iberian wild goat (Capra pyrenaica, Schinz 1838, Bovidae) begins the re-colonization of the Pyrenees. Mammalia 2013, 77(4), pp. 403–407. [CrossRef]

- Garnier, A.; Besnard, A.; Crampe, J.P.; Estèbe, J.; Aulagnier, S.; Gonzalez, G. Intrinsic factors, release conditions and presence of conspecifics affect post-release dispersal after translocation of Iberian ibex. Animal Conservation 2021, 24(4), pp. 626-636. [CrossRef]

- Reiger, H.A.; Robson, D.S. Estimating population number and mortality rates. In: The Biological Basis of Freshwater Fish Production. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, United Kingdom, pp. 31-66.3, 1967.

- Nievergelt, B.. Estimates of Population Size and Changes of the Walia Ibex. In Ibexes in an African Environment (pp. 77-81). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 1981.

- Escós, J.; Alados, C.L. Estimating mountain ungulate density in sierras de Cazorla y Segura. Mammalia 1988, 52(3), pp. 25-428. [CrossRef]

- Kleinbaum, D.G., Lawrence K.L.; Keith, M.E. Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. 2nd ed. The Duxbury Series in Statistics and Decision Sciences, 1988.

- Doménech, J.M.; Navarro, J.B. Regresión logística binaria, multinomial y de Poisson. Signo, Barcelona, Spain. 2005.

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.Rproject. org/ 2012.

- Prada, C.; Herrero J.; García-Serrano A.; Fernández-Arberas, O.; Gómez, C. Estimating Iberian wild goat abundance in a large rugged forest habitat. Pirineos 2019, 174, pp. 1–72.

- González, J.; Herrero, J.; Prada, C.; Marco, J. Changes in wild ungulate populations in Aragon, Spain between 2001 and 2010. Galemys 25 2013, pp. 51–59.

- Hernández, R.; Herrero, J.; García-Serrano, A. Distribución de los ungulados silvestres y asilvestrados en Aragón durante el quinquenio 2016-20 y su evolución desde mediados del siglo XIX. Internal report of the Regional Government of Aragon, Zaragoza, Spain, 2022.

- Giacometti, M.; Roganti, R.; De Tann, D.; Stahlberger-Saitbekova, N.; Obexer-Ruff. G. Alpine ibex Capra ibex ibex x domestic goat C. aegagrus domestica hybrids in a restricted area of southern Switzerland. Wildl Biol 2004, 10, pp. 137-143. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, T.F.; Luigi-Sierra, M.G. ; Castelló, A. ; Cabrera, B. ; Noce, A. ; Mármol-Sánchez, E. ; García-González, R. ; Fernán- dez-Arias, A. ; Alabart, J.L. ; López-Olvera, J.R. ; Mentaberre, G., Granados-Torres, J.E. ; Cardells-Peris, J. ; Molina, A. ; Sànchez, A. ; Clop, A. ; Amills, M. Assessing the levels of intraspecific admixture and interspecific hybridization in Iberian wild goats (Capra pyrenaica). Evolutionary Applications 2021, 14, pp. 2618-2634. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, I.; Anadón, J.A.; Díaz, M. ; Nicola, G.G., Tella, J.L.; Giménez, A. What is wrong with current translocations ? A review and a decision making proposal. Front Evol Environ 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).