1. Introduction

Large mammals are particularly vulnerable to anthropopression because of their extensive spatial requirements, usually low reproductive rates, and often insufficient population numbers. Additionally, the presence of those species stimulates conflicts related to damages to crops, competition with the livestock, or traffic accidents [

1,

2]. Being an attractive source of meat and trophies, they are often threatened by overhunting or poaching [

3,

4].

Due to their nutritional requirements, foraging habits, and biomass, large herbivores are significant components of complex food webs and are the main food source for predators and scavengers. They contribute to the maintenance of habitat mosaics and exert essential impacts on vegetation dynamics and nutrient cycling [

2,

5]. In many cases, habitat patches that are suitable for the survival of large mammals are too small to support their viable populations due to strongly modified and fragmented contemporary landscapes [

6]. Therefore, so important is the maintenance of networks of ecological corridors providing a linkage among isolated subpopulations, which may allow them to function as a metapopulation. Large intact tracts of forest habitats are particularly valuable for that purpose [

7,

8,

9].

The wisent (European bison)

Bison bonasus L., the largest native mammal inhabiting forest ecosystems of Europe, belongs to gregarious species, spending their lives in groups counting from a few animals to even several tens of individuals. The species was rescued from the brink of extinction a hundred years ago, when only a few animals remained alive in captivity. Therefore, the present world population originates from just 12 founders. Hence, its gene pool is extremely narrow, and as a consequence, the level of inbreeding within existing populations is excessively high [

10]. Therefore, to avoid further loss of genetic diversity, it is so important to maintain populations of this species at possibly high numbers [

11]. For this species, a minimal, genetically safe population is estimated for about 100 individuals [

12,

13].

Free-ranging wisents have been restored to the Carpathians through introductions after their absence, lasting for about 250 years. At the moment within this eco-region, their populations exist in four countries: Poland, Slovakia, Romania, and Ukraine. All of them consist of individuals belonging to the Lowland-Caucasian line [

14,

15]. According to the official census, there are now: 750 wisents in Poland in herds of the Bieszczady Mountains, 58 animals in National Park Poloniny in Slovakia, and 96 in three herds within Ukrainian Carpathians [

16].

By the 90s of the XXth century, the numbers of this species within the whole territory of Ukraine were estimated at 685 individuals. However, due to mismanagement, overhunting, poaching, etc., the numbers of free-ranging wisents dwindled there to 425, and four of the formerly created free-ranging herds were lost. Presently, animals belonging to three remaining herds in the Carpathians constitute almost 25% of the whole Ukrainian population. The herd from Skolyvski Beskydy N.P., situated just some 30 km from the Polish herd in the Bieszczady Mountains, counts 43 animals [

16]. Since their ranges are being relatively the least threatened by acts of present warfare, the survival of Carpathian herds is extremely important for the future existence of this species in Ukraine [

17]. Moreover, wisents inhabiting the Ukrainian part of the Carpathians may, in some perspective, provide a connection between Polish, Slovak, and Romanian herds, extending the range of this species over the whole eco-region. Therefore, so important seems the facilitation of transboundary contacts among wisents dwelling in Polish Bieszczady Mountains, Slovak N.P. Poloniny, and Ukrainian Skolyvski Beskydy N.P., allowing for creation of their functional metapopulation.

There were several attempts in the past to identify the most effective ecological corridors allowing for wildlife migrations along the Carpathian arch [

18,

19,

20]. Nevertheless, together with changing conditions of land cover and local development, limiting continuous tracts of forests, as well as specific requirements of wisents towards their migration routes, it is necessary to confirm and update available knowledge on ecological connectivity there and indicate potential ecological corridors for wisents within the transboundary area of those three neighboring countries.

Therefore, this paper aims at the identification of potentially the most optimal solutions, allowing for wisents to move among present home ranges of the closely situated herds of Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine.

2. Study Area, Materials, Methods

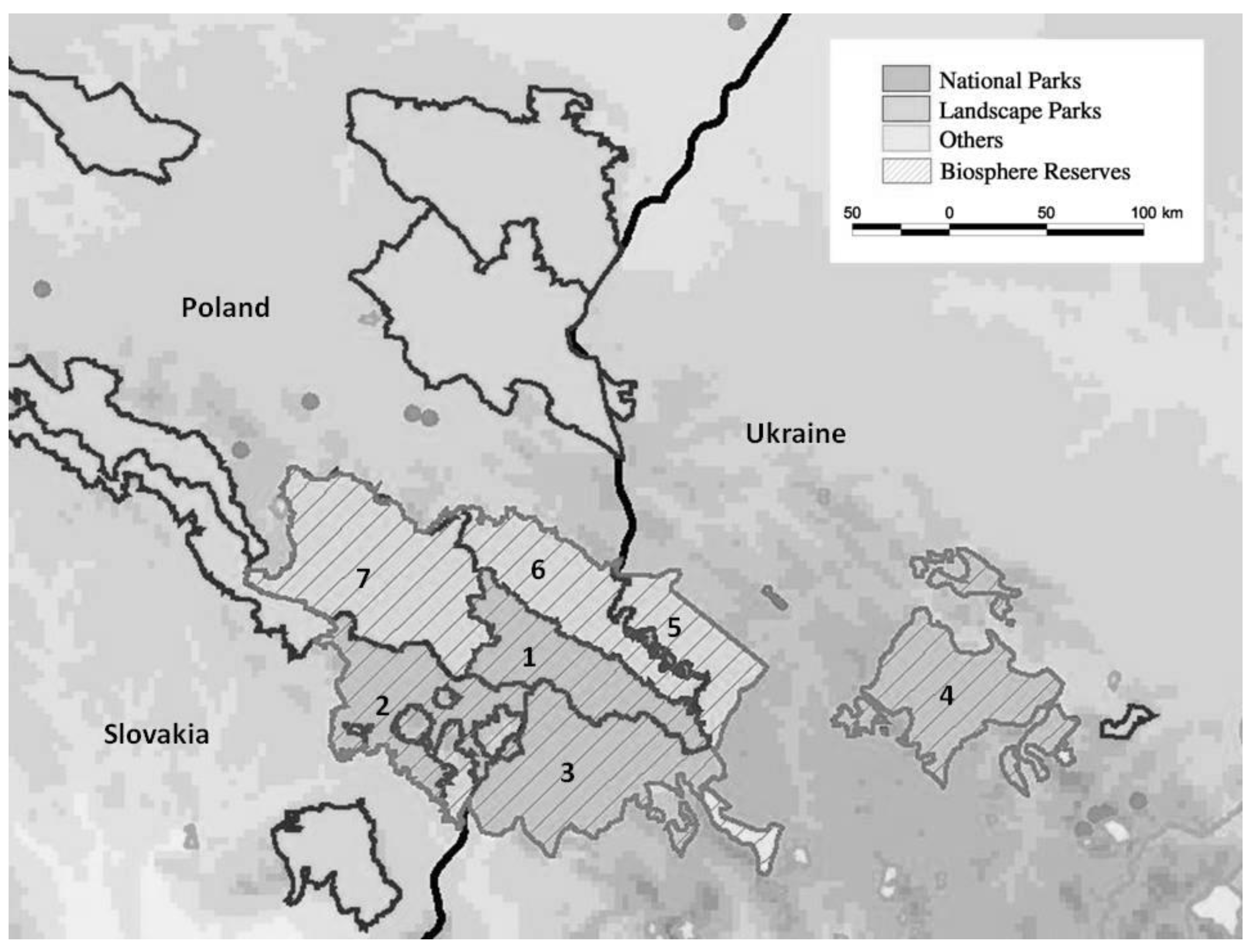

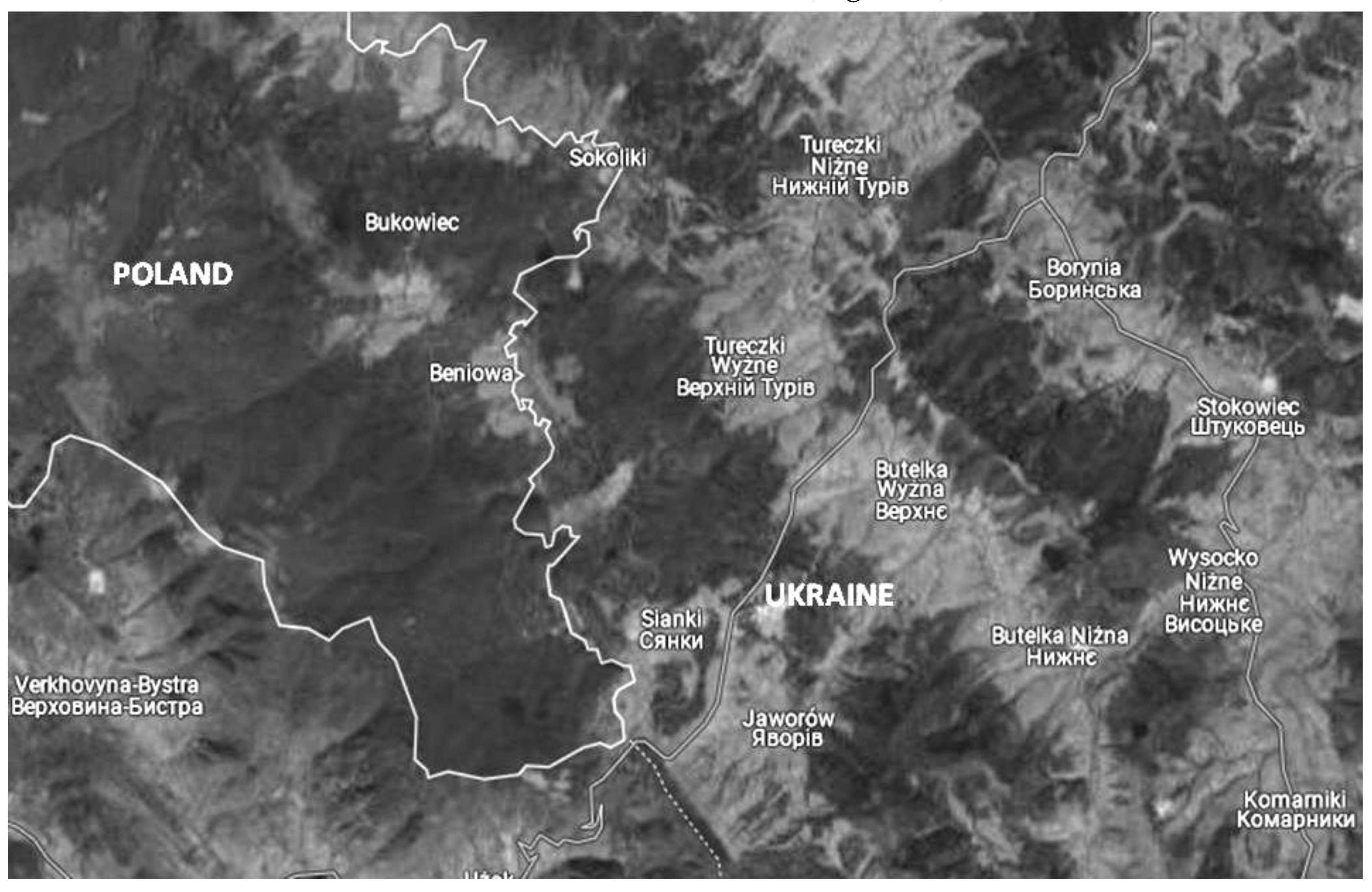

Data for this paper was collected within the transboundary area of Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine, including Bieszczadzki National Park with Forest Districts of Lutowiska, Stuposiany, Cisna, and Komańcza (including two landscape parks) on the Polish side, Poloniny National Park in Slovakia, and the Uzhansky National Park with recently established National Park Boikivshchyna (partially the Nadsiansky Landscape Park) in Ukraine (

Figure 1).

Within this area, the elevation of its highest peak is 1346 m above sea level, and the forest cover occupies up to 85% of the range. Among forest stands, the beech-fir (

Fagus sylvatica-Abies alba) association dominates, while along watercourses, alder-willow (

Alnus glutinosa-Salix spp.) stands occur. The Scotch pine (

Pinus sylvestris) overgrows former cultivated fields [

21].

Included were all available records of wisents’ presence (direct observations, tracts, feces, and telemetric fixes) collected in Poland between 2003-2022, in Slovakia between 2004-2024, and in Ukraine between 2003-2024, in a proximity of national borders. Data was collected by staff members of national parks, rangers, and foresters of three countries and the staff of the Carpathian Wildlife Research Station of the Polish Academy of Sciences. In total, 105758 such records were considered in this analysis.

The distribution of data was analyzed with the ArcView 9.3 software (Esri Polska:

https://www.esri.pl/, accessed on 10.08.2024). Habitat (parameters were classified according to the CORINE Land Cover (CLC), including the features of the terrain (elevation above sea level), land cover, and potential human-related obstacles for animal movements (settlements, roads, fencing).

3. Results

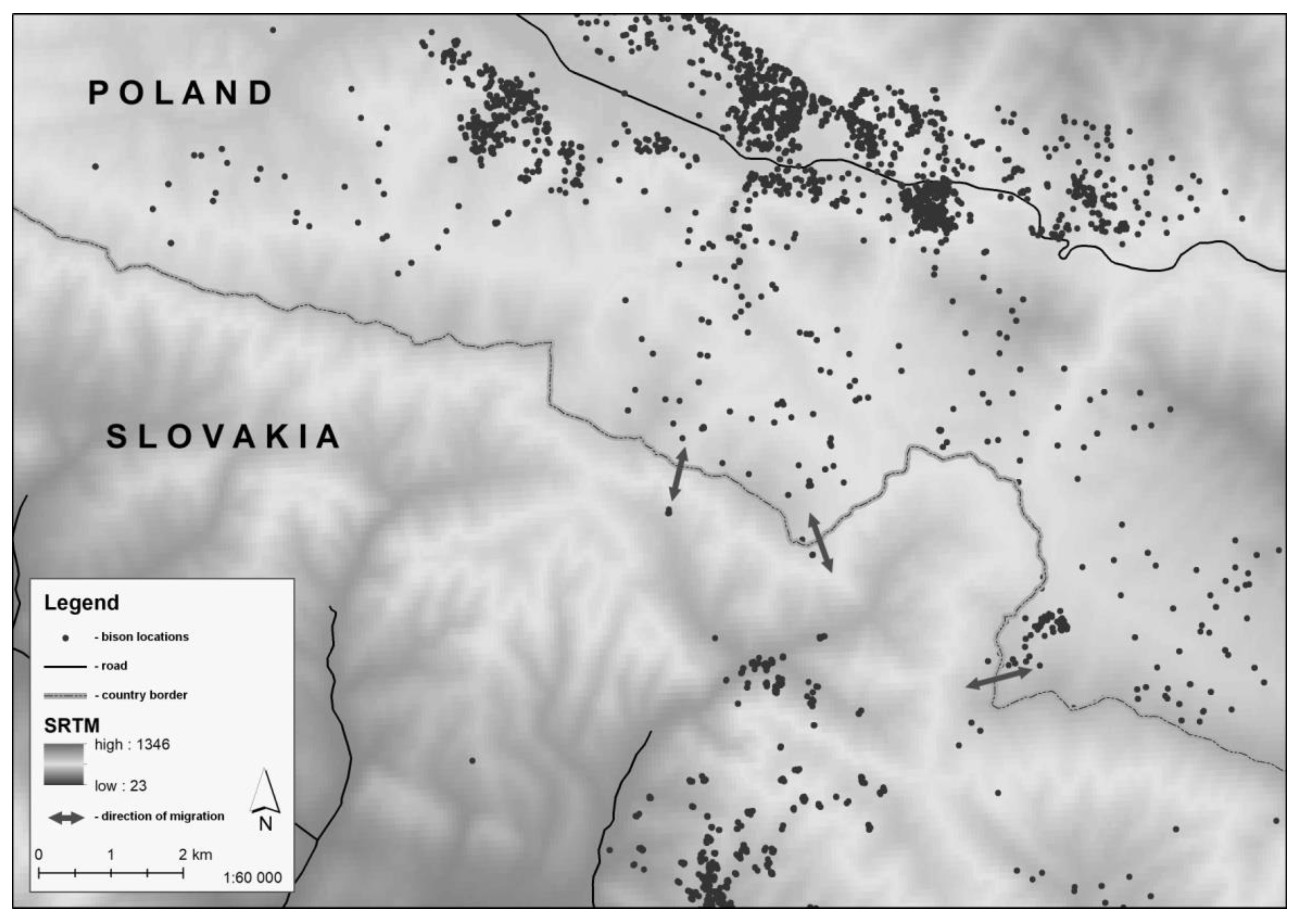

Generally, when animals were approaching the line of a national border, they were following the least demanding route, leading to possibly the lowest available part of the mountain ridge. This was particularly well visible along the state border between Poland and Slovakia, which runs along the main ridge of the Carpathians (

Figure 2)

The maximal elevation where wisents were observed within this area was 1145 m above sea level; however, this was only one record. Above 1000 m, only 5 observations were recorded. An absolute majority of wisents’ occurrence was recorded there between 555 and 705 m above sea level. Nevertheless, even the records obtained there at the highest elevations come from the forested area.

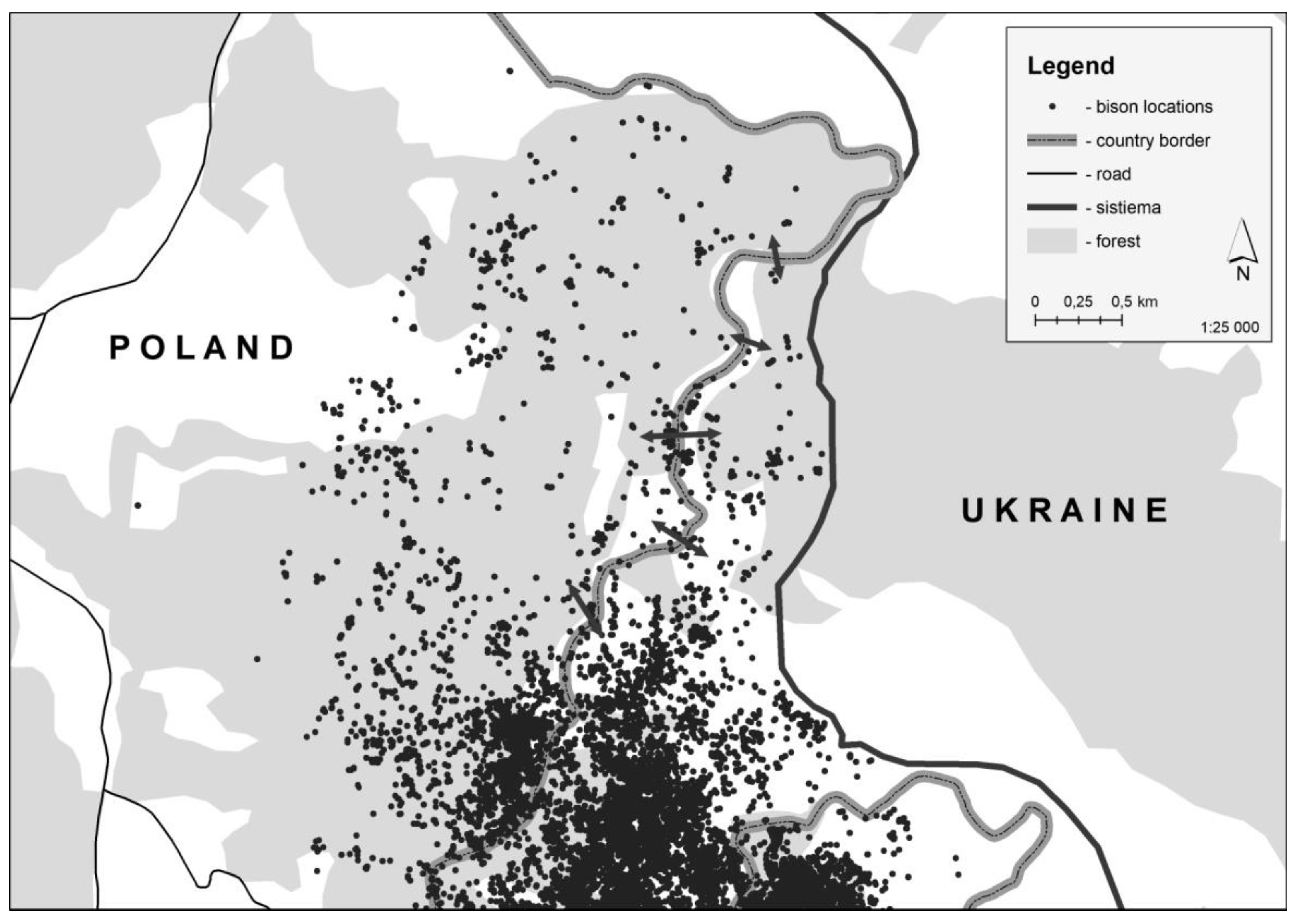

Regarding preferences towards the land cover, there was a strong tendency for movements of wisents to select forested areas or at least to cross an open land at its possibly the most narrow stretch. Since the whole extend of the Polish-Slovak border is below the timberline (in Bieszczady estimated for about 1150 m above sea level), this relation could not be well observed there. However, along the Polish-Ukrainian border there are numerous open areas belonging to former villages that disappeared after 1945. Therefore, wisents approaching the border, although they were using those open habitat patches for grazing, generally preferred to stay under tree canopy (

Figure 3).

Within the zone wide for 150 m, which we assumed as the area when wisents are the most likely to cross the state border, 56% of their records of occurrence were within the forested land, while the remaining 44% were recorded on open land.

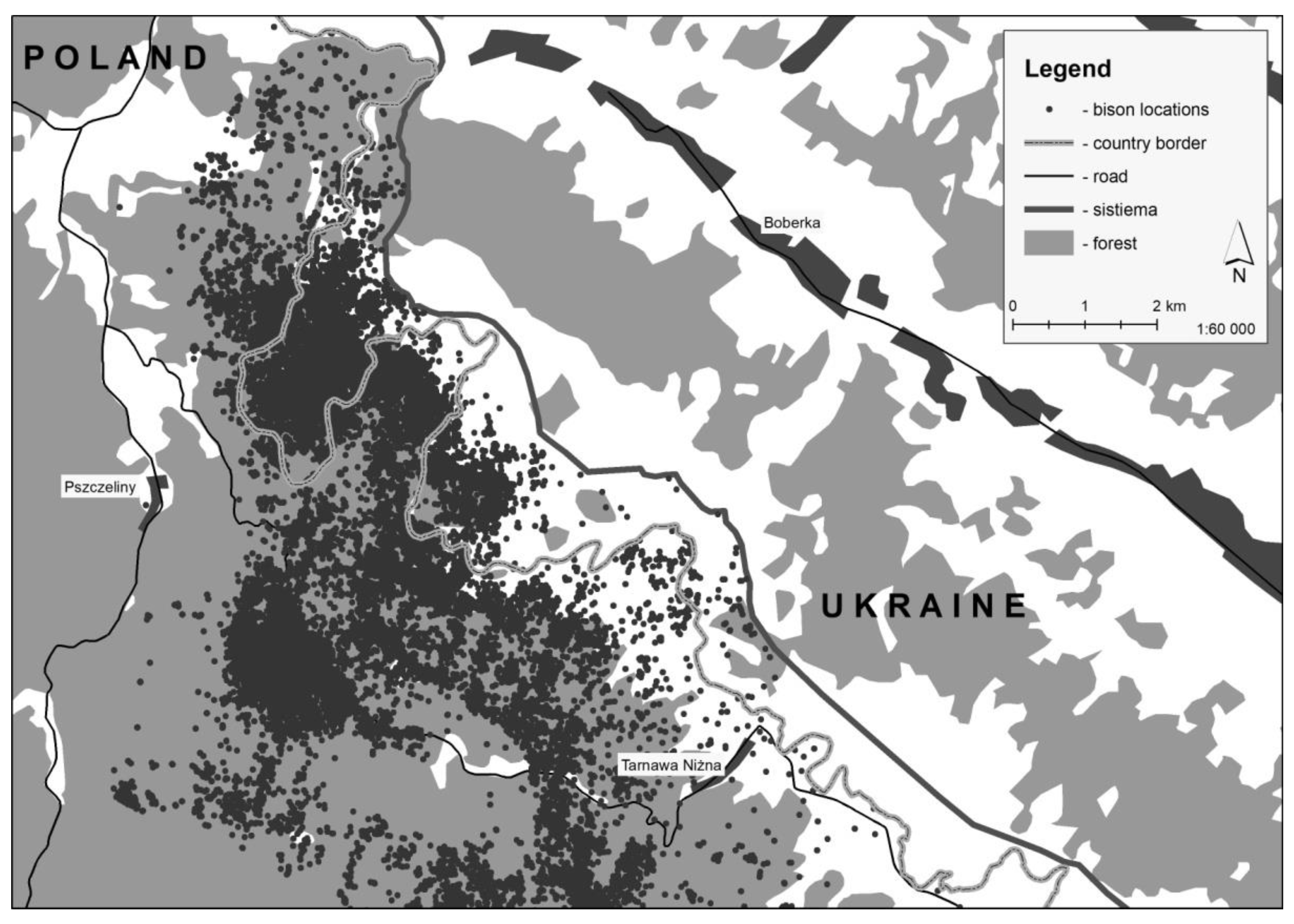

A critical barrier preventing wisents’ movements is a border fence (so-called „systiema”) along the Ukrainian border. Presently, none of the large ungulates inhabiting this area is able to come across. The distribution of records of wisents’ presence along the eastern Polish border clearly proves this situation (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Within the transboundary zone in the Carpathians of Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine, there are presently three separate populations of wisents. Together they count over 900 individuals, which makes this potential metapopulation the second in numbers after Polish and Belarussian herds, living in Białowieska Forest [

16]. Such population size could assure its viability over a considerable period of time.

An important aspect suggesting the urgent need to secure the future of wisent population in the Ukrainian Carpathians is the fact that those are the only herds of this country still living outside the area directly threatened by the acts of warfare. Other Ukrainian herds are situated either in close proximity of military activities or their home ranges became already heavily mined [

17,

22]. It is well known that due to its body size and gregarious behavior, this species is particularly vulnerable to anthropopression, especially persecution, illegal killing, etc. The disappearance of wisents from Białowieska Forest in 1919 was a direct effect of such events connected with World War I [

10]. Presently, Ukrainian herds in the Carpathians are too small to guarantee their viability in the long term, and their supplementation with new individuals through an import of animals from other countries is too difficult now due to the current political situation.

Therefore, an optimal solution for mitigation of their further inbreeding would be the creation of conditions for spontaneous migrations of animals among Polish, Slovak, and Ukrainian herds [

13,

23]. A favorable circumstance for such initiative is the existence of the International Biosphere Reserve „Eastern Carpathians”, including national and landscape parks, situated exactly within the transboundary area of those three countries. Part of this area belongs also to the Natura 2000 site. Mutual international agreements may make the management of wildlife populations more efficient there and help to protect remaining patches of natural forest habitats within this area [

24,

25,

26] (

Figure 1).

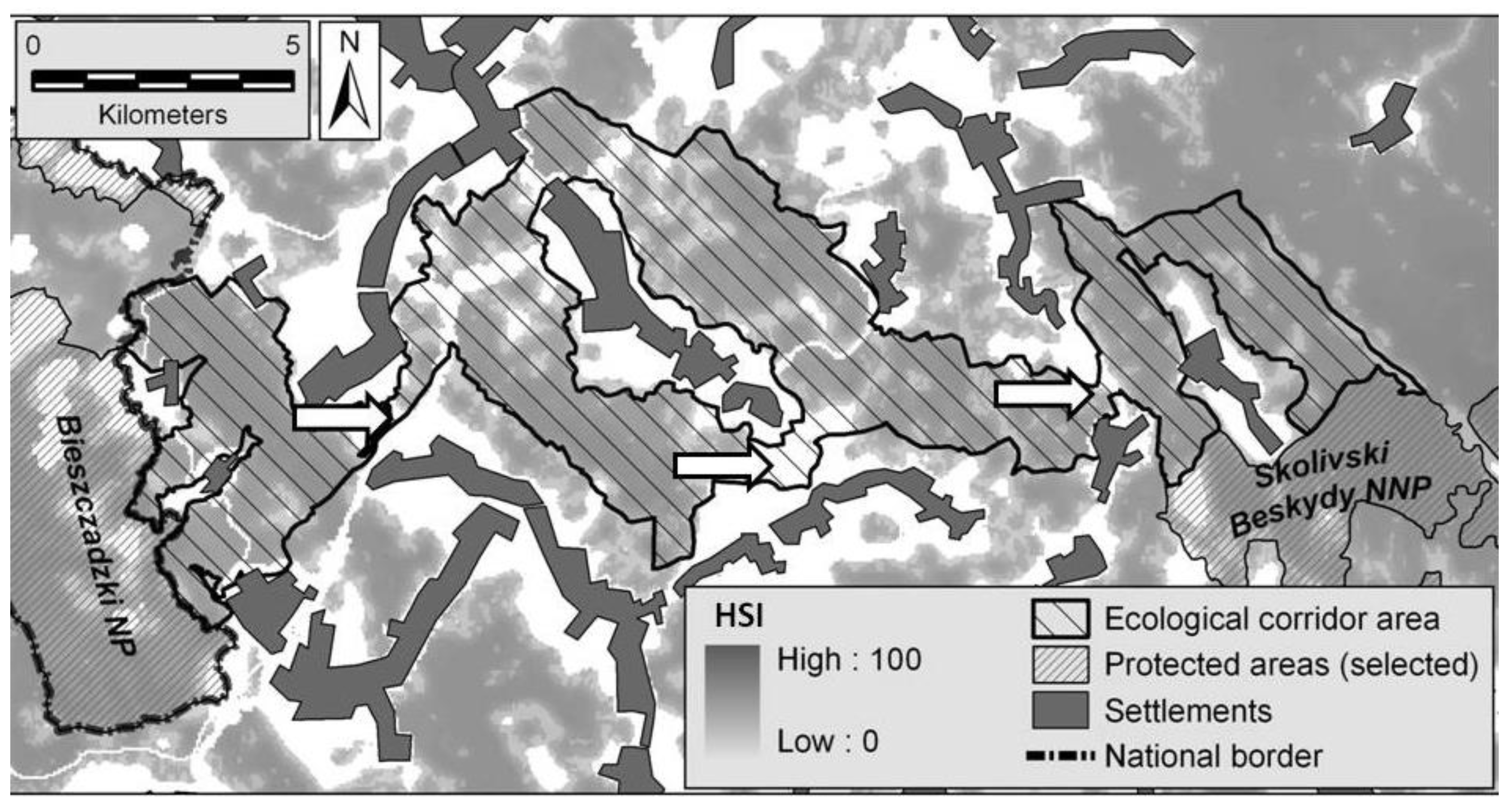

Former papers concerning the possibilities for animal migrations along the Carpathian range were mostly based upon theoretical assumptions using the habitat suitability index (HSI) [

18,

19,

20]. In this paper, we attempted to collect data from all three neighboring countries on the presence records of wisents along national borders. These datasets were compared with land cover and elevation maps, as well as confronted with potential barriers for animals’ movements like border fences, settlements, or transportation routes.

In general, the Carpathians, with forest habitats strongly dominating there, are assumed to be a large migration corridor for the wildlife, connecting the south-eastern part of Europe with the center of the continent [

18,

20]. Nevertheless, across this mountain chain lead numerous roads and railroads, and in many places mountain valleys are densely inhabited by people. Therefore, natural migration routes are often difficult to pass by large mammals, especially the human shy species like wisents in the Carpathians [

27,

28]. Exceptionally favorable conditions for wildlife movements are within some 80 km along the Polish-Slovak border, from the border with Ukraine at Krzemieniec Peak in the east and the border crossing between Poland and Slovakia at Barwinek in the west. Within this distance there is only one rarely used railroad connecting Poland and Slovakia at Nowy Łupków and one second-class public road leading to the small border crossing Radoszyce-Palota. Former villages encroaching mountain valleys on the Polish side mostly disappeared after 1945. Therefore, since the whole of this area is situated below the timberline, it is covered by dense forests with only a few small openings. Earlier observations on wisents crossing the Carpathian ridge there proved that animals within this area could select their routes without any obstacles [

29,

30].

According to obtained records on wisents’ presence along the country border there, for their crossings they prefer sites at possibly low elevations at mountain passes, but in fact single bulls were occasionally observed even at high ridges of Bieszczady [

15]. Since there are no local plans for changes in forest management and land use patterns, there is no need for establishing special corridors securing possibilities for wisent movements between those two countries. A quite different situation exists along borders between Poland and Slovakia on one side and Ukraine on the other. Between the Slovak-Ukrainian border crossing Ubla-Velikij Bereznyj and the Polish-Ukrainian border crossing Krościenko-Smolnyca, there is a distance of some 130 km. Only some 20 km to the north are outside of protected areas like national or landscape parks, so a majority of this area remains under legal protection. River San, which flows along the Polish-Ukrainian border there, is shallow and narrow, not posing any obstacles for wisent crossings. Nevertheless, on the Ukrainian side there are a main road and a major railroad leading from the Lvov Province in the north to the Zakarpacie Province in the south. Both routes are without any installations allowing for undisturbed crossings by animals. Also, the density of human settlements is much higher there compared to the Polish side, while the percentage of forest cover is considerably lower (

Figure 5).

Additional obstacle for animal migrations is a border fence built up along the former Soviet border in the 80s of the XX century, partially neglected in the beginning of the XXI century but recently considerably reinforced. It runs from several hundred meters up to eight km parallel to the actual country border, and such construction is impassable for large ungulates, like it has been proved in relation to other installations along borderlines [

31,

32] (

Figure 4).

Unfortunately, any attempt to make some gaps in this infrastructure, allowing for animal movements, is beyond the competency of the Forest or National Park Service and especially difficult now due to present military activities.

The most important for future functioning of wisents’ metapopulation within this transboundary area is a potential ecological corridor connecting Skolivski Beskyd N.P. in Ukraine, which is inhabited by a free-ranging wisent herd, and Bieszczadzki N.P. in Poland, which is a part of the home range of an eastern subpopulation of wisents in Bieszczady Mountains [

33]. A majority of this narrow route is now covered by forests; however, there are several critical points between closely situated settlements in Ukraine where habitat improvements and protection of forest cover would be necessary in the future (

Figure 6).

Therefore, the establishment of metapopulation of wisents among three neighboring countries is potentially possible since there are favorable conditions regarding the land cover (high percentage of forests and low intensity of land use) and the dominance of protected areas in this region. At the moment, there are no natural or anthropogenic obstacles for wisents’ movements between Poland and Slovakia; however, making possible an exchange with Ukrainian herd is currently more complicated and will require further maintenance of continuous forest tracts along the potential migration route. Especially important are critical, narrow passages between neighboring villages [

34].

Therefore, considering present threats for the remaining part of wisent herds in this country, further efforts towards the creation of conditions allowing for the connectivity of the Carpathian herd in Ukrainian Skolyvski Beskyd with Polish and Slovak neighbors are urgent. An approach towards the creation of transboundary metapopulation of wisents proposed in this paper can be useful in cases of small, isolated populations, threatened with inbred, established in neighboring countries with various policies towards the wildlife and different conservation regimes. The success of future management of this wisent population towards the maintenance of its genetic diversity should depend mostly upon effective protection of ecological connectivity, first of all the continuous tracts of forests among home ranges of populations in three neighboring countries.

5. Conclusions

The declining population of free-ranging wisents in Ukraine and further threats connected with the acts of warfare there seriously threaten the future of the species in this country. Connection of wisents from Ukraine with herds dwelling in the Polish and Slovak Carpathians into one functional metapopulation may assure further viability of Ukrainian subpopulation. Generally, habitat conditions within this range still allow for animals’ migrations; however, a critical factor can be the further maintenance of continuous forest cover along the route connecting the Skolyvski Beskyd range in Ukraine with the Bieszczady Mountains in Poland. Currently, an artificial barrier along the Ukrainian border is a major obstacle for maintaining connectivity among wisents in Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kajetan Perzanowski, Aleksandra Wołoszyn-Gałęza and Oksana Maryskevych; Data curation, Kajetan Perzanowski; Formal analysis, Maciej Januszczak; Investigation, Maciej Januszczak, Oksana Maryskevych, Martina Vlasakova and Jozef Štofík; Methodology, Kajetan Perzanowski and Aleksandra Wołoszyn-Gałęza; Project administration, Kajetan Perzanowski; Resources, Aleksandra Wołoszyn-Gałęza, Maciej Januszczak, Oksana Maryskevych, Martina Vlasakova and Jozef Štofík; Software, Maciej Januszczak; Supervision, Kajetan Perzanowski; Validation, Maciej Januszczak; Visualization, Maciej Januszczak; Writing – original draft, Kajetan Perzanowski; Writing – review & editing, Kajetan Perzanowski, Aleksandra Wołoszyn-Gałęza and Oksana Maryskevych. Funding Acquisition, N.A.” All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Field data was collected during the routine activities of the staff of Carpathian Wildlife Research Station, Poloniny National Park, Uzhansky and Bojkivszczyna National Parks.

Data Availability Statement

Available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the staff of Uzhansky and Bojkivszczyna National Parks for passing an info on wisents’ presence records.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- Cardillo, M.; Mace, G.M.; Jones, K.E.; Bielby, J.; Bininda-Emonds, O.R.P.; Sechrest, W.; Orme, C.D.L.; Purvis, A. Multiple causes of high extinction risk in large ammal species. Science 2005, 309, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripple, W.J.; Chapron, G.; López-Bao, J.V.; Durant, S.M.; Macdonald, D.W.; Lindsey, P.A.; Bennett, E.L.; Beschta, R.L.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Campos-Arceiz, A.; Corlett, R.T.; Dickman, A.J.; Dirzo, R.; Dublin, H.T.; Estes, J.A.; Everatt, K.T.; Galetti, M.; Goswami, V.R.; Hayward, M.W.; Hedges, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Hunter, L.T.B.; Kerley, G.I.H.; Letnic, M.; Levi, T.; Maisels, F.; Morrison, J.C.; Nelson, M.P.; Newsome, T.M.; Painter, L.; Pringle, R.M.; Sandom, C.J.; Terborgh, J.; Treves, A.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; Vucetich, J.A.; Wirsing, A.J.; Wallach, A.D.; Wolf, C.; Woodroffe, R.; Young, H.; Zhang, L. Saving the world’s terrestrial megafauna. BioScience 2016, 66, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazy, L.; Bonenfant, C.; Gaillard, J.M.; Courchamp, F. Rarity, trophy hunting, and ungulates. Animal Conservation 2012, 15, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.S.; McCauley, D.J.; Galetti, M.; Dirzo, R. Patterns, causes, and consequences of anthropocene defaunation. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2016, 47, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandom, C.J.; Ejrnæs, R.; Hansen, M.D. Sandom, C.J.; Ejrnæs, R.; Hansen, M.D.; Svenning, J-C. High herbivore density associated with vegetation diversity in interglacial ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 2014, 111, 4162–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodroffe, R. Predators and people: using human densities to interpret declines of large carnivores. Animal Conservation 2000, 3, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanski, I.; Ovaskainen, O. The metapopulation capacity of a fragmented landscape. Nature 2000, 404, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer-Schadt, S.; Kaiser, T.S.; Frank, K.; Wiegand, T. Analysing the effect of stepping stones on target patch colonization in structured landscapes for Eurasian lynx. Landscape Ecology 2014, 26, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, S.; Bodin, Ö.; Fortn, M-J. Stepping stones are crucial for species’ long-distance dispersal and range expansion through habitat networks. J. Appl. Ecology 2013, 51, 171–182. [CrossRef]

- Krasińska, M.; Krasiński, Z. European bison: the nature monograph; Springer, Heidelberg-New York-Dordrecht-London, 2013; p. 317.

- Frankham, R. Genetic rescue of small inbred populations: meta-analysis reveals large and consistent benefits of gene flow. Molecular Ecology 2015, 24, 2610–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, L.S.; Smouse, P.E. Demographic consequences of inbreeding in remnant populations. American Naturalist 1994, 144, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olech, W.; Klich, D.; Perzanowski, K. An approach towards an improvement of genetic structure of a wisent (Bison bonasus) population in the Carpathians. European Bison Conservation Newsletter 2021, 13, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Olech, W. The changes of founders’ numbers and their contribution to the European bison population during 80 years of species’ restitution. European Bison Conservation Newsletter 2009, 2, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Perzanowski, K.; Marszałek, E. Powrót żubra w Karpaty/The return of the wisent to the Carpathians; RDLP w Krośnie, Krosno, 2012; p. 175.

- Raczyński, J.; Bołbot, M., Eds. European Bison Pedigree Book 2022. Białowieski Park Narodowy, Białowieża, 2023; p. 81.

- Perzanowski, K.; Smagol, V. European bison in Ukraine threatened by Russian invasion. European Bison Conservation Newsletter 2022, 14, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Deodatus, F.; Protsenko L. Eds. Creation of ecological corridors in Ukraine. State Agency for Protected Areas of the Ministry of Environmental Protection of Ukraine, Altenburg & Wymenga Ecological Consultants, Interecocentre Kyiv, 2010; p. 140.

- Huck, M. Huck, M. , Jędrzejewski, W. , Borowik, T., Miłosz-Cielma, M., Schmidt, K., Jędrzejewska, B., Nowak, S.; Mysłajek, R.W., Habitat suitability, corridors and dispersal barriers for large carnivores in Poland. Acta Theriologica 2010, 55, 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Perzanowski, K.; Pędziwiatr, K.; Konieczna, P.; Śmiełowski, J. Proposed migration corridors for large mammals in the south-east of Polish Carpathians. Zoology and Ecology 2020, 30, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, S.; Szary A. Zbiorowiska leśne Bieszczadzkiego Parku Narodowego. Monografie Bieszczadzkie 1, 1997; p. 175.

- Smagol, V.; Reshetylo, O.; Smagol, V. The impact of Russian military aggression on Ukrainian subpopulations of the European bison. European Bison Conservation Newsletter 2023, 15, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Perzanowski, K.; Akçakaya, H. R.; Beaudry, F.; Van Deelen, T.; Parnikoza, I.; Khoyetskyy, P.; Waller, D.; Radeloff, V. Cost-effectiveness of different conservation strategies to establish a European bison metapopulation in the Carpathians. Journal of Applied Ecology 2011, 48, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, S.A.; McRae, B.; Adriaensen, F.; Beier, P.; Shirley, M.; Zeller, K. Biological corridors and connectivity. In Key Topics in Conservation Biology 2. Macdonald D.W.; Willis, K.J. Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2013; pp. 384–404. [CrossRef]

- Estreguil, C.; Caudullo, G.; de Rigo, D. Connectivity of Natura 2000 forest sites in Europe. Computational Engineering, Finance, and Science (cs.CE); Populations and Evolution (q-bio.PE), 2014, F1000 Posters 5; 485.

- Niewiadomski, Z.; Maryskevich, O.; Perzanowski, K. The East Carpathians Biosphere Reserve/Międzynarodowy Rezerwat Biosfery „Karpaty Wschodnie”. In Biosphere Reserves in Poland/Rezerwaty Biosfery w Polsce. Kunz, M.; Nienartowicz, A. Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, Toruń, 2013; pp. 109–128.

- Perzanowski, K.; Januszczak, M.; Wołoszyn-Gałęza, A. Characteristics of seasonal migration corridors of wisents at Bieszczady. Roczniki Bieszczadzkie 2016, 24: 145-156.

- Perzanowski, K.; Wołoszyn-Gałęza, A.; Januszczak, M. Habitat parameters within seasonal migration trails of Bieszczady wisents. European Bison Conservation Newsletter 2019, 12, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Perzanowski, K.; Januszczak, M. Movements and habitat use of wisents in intensively managed rural landscape of Slovak Carpathians. European Bison Conservation Newsletter 2016, 9, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wasiak, P.; Perzanowski, K. Post-release dispersal patterns of wisent bulls introduced to Bieszczady Mountains. European Bison Conservation Newsletter 2014, 7, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Linnell, J.D.C.; Trouwborst, A.; Boitani, L.; Kaczensky, P.; Huber, D.; Reljic, S.; Kusak, J.; Majic, A.; Skrbinsek, T.; Potocnik, H. Border security fencing and wildlife: the end of the transboundary paradigm in Eurasia? PLOS Biology 2016, 14, e1002483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trouwborst, A.; Fleurke, F.; Dubrulle, J. Border fences and their impacts on large carnivores, large herbivores and biodiversity: An international wildlife law perspective. Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 2016, 25, 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Maryskevych, O.; Kulykiv, O. Problemy reintrodukcji żubra w Beskidach Skolskich. Roczniki Bieszczadzkie 2015, 23, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger, A.P.; Wierzchowski, J.; Chruszcz, B.; Gunson, K. GIS-generated, expert-based models for identifying wildlife habitat linkages and planning mitigation passages. Conservation Biology 2002, 16, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).