Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

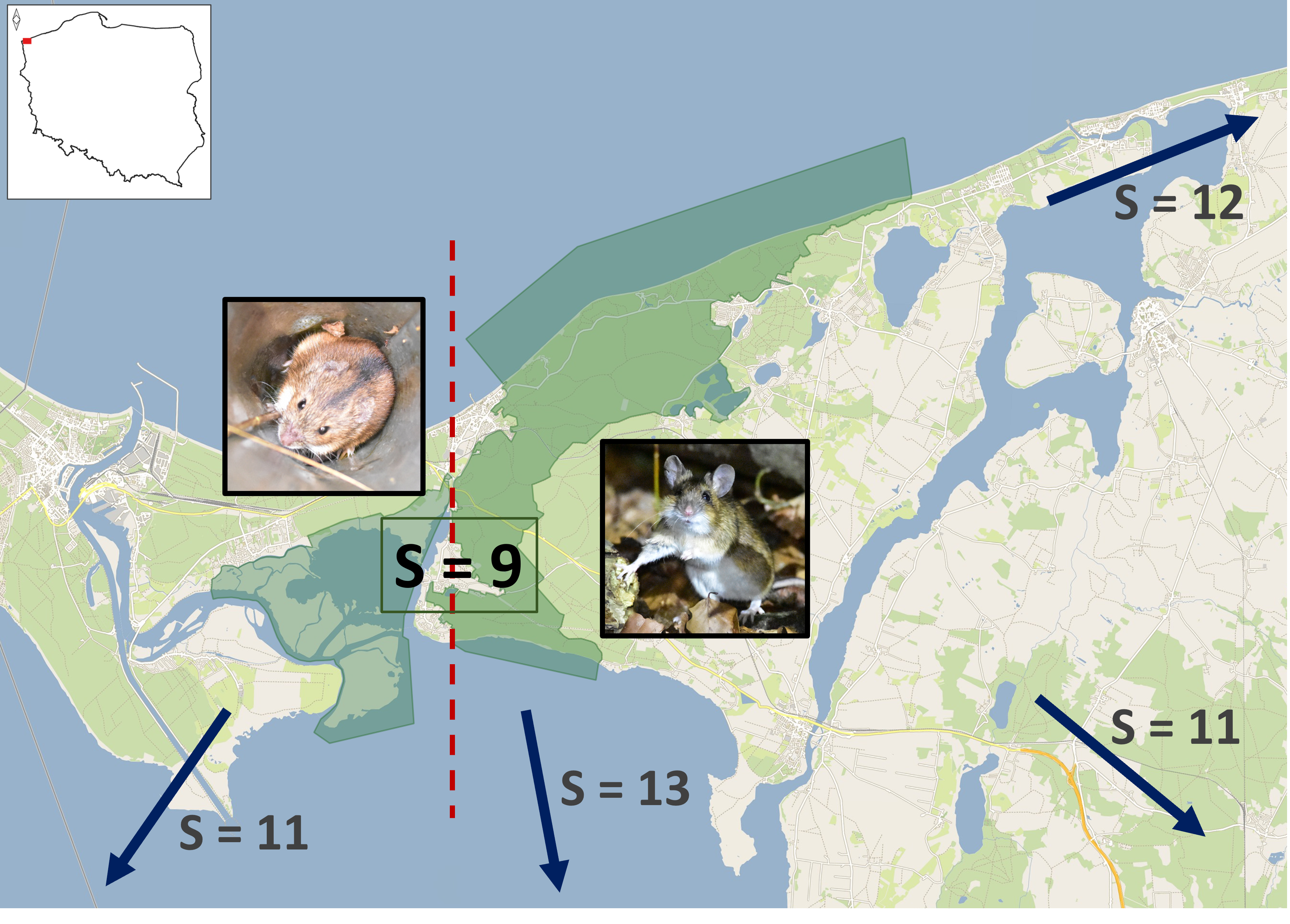

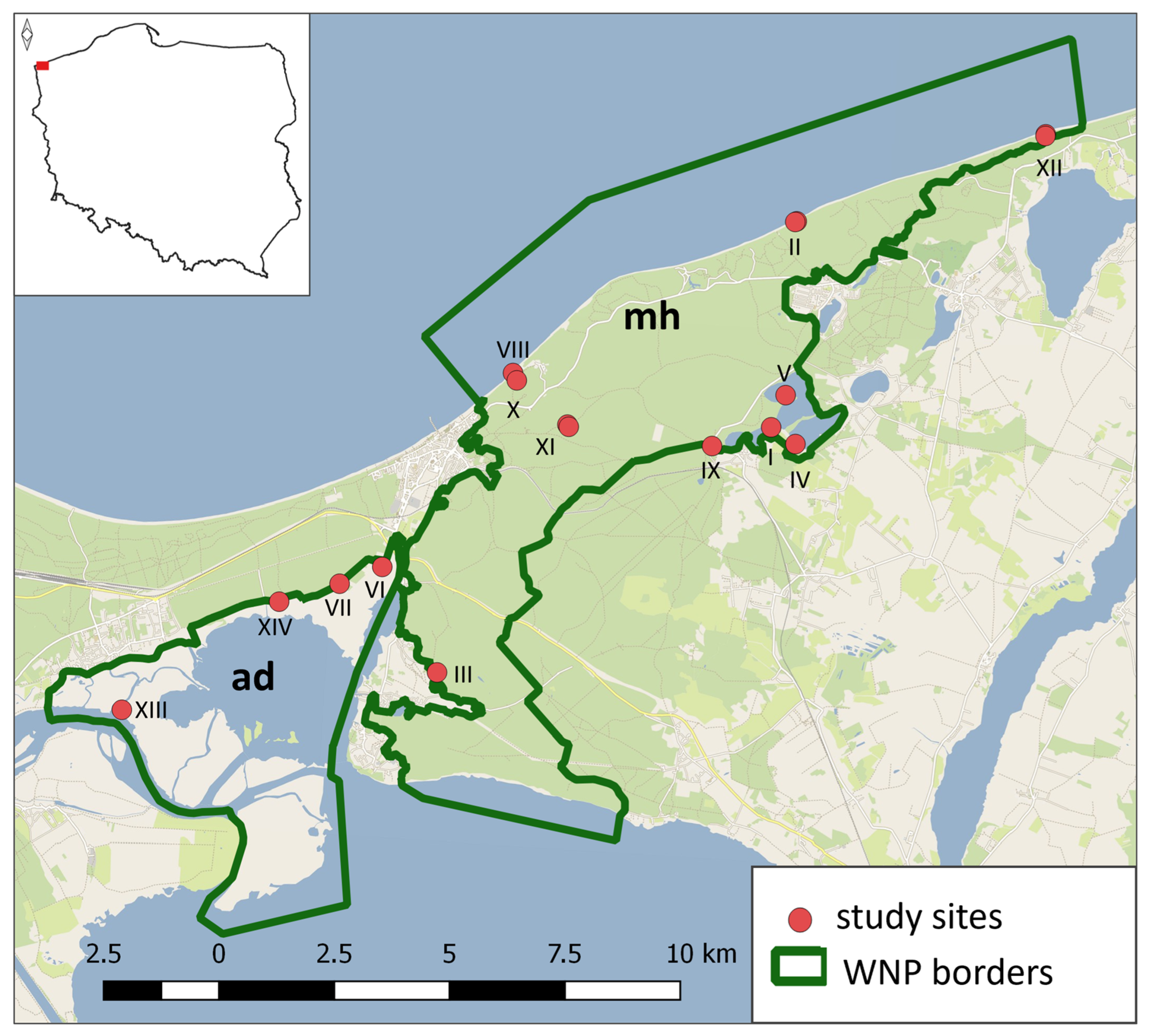

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Small Mammals Survey

| Site | Landscape unit | Habitat characteristics |

| I | mh | Alder-ash riparian forest Fraxino-Alnetum (70 years) along a stream between two lakes, transitioning to the ecotone of black alder swamp forest and reed bed along the shore of eutrophic lake |

| II | mh | Treeless communities on coastal dunes; the site divided into two shorter trap-lines of equal length: IIa – grey dunes Helichryso-Jasionetum, IIb – white dunes Elymo-Ammophiletum |

| III | mh | Mesic meadow Arrhenatherion elatioris on a hill slope, regularly mowed; few scattered shrubs near the trap-line |

| IV | mh | Black alder swamp forest Ribeso nigri-Alnetum (45 years) along the shore of eutrophic lake; hollows filled with water, locally patches of reed Phragmites australis in the herbaceous layer |

| V | mh | Moist subatlantic oak-hornbeam forest Stellario-Carpinetum (40-165 years) on a lakeside terrace and parallel slope; abundant hazelnut Corylus avellana in the undergrowth |

| VI | ad | A mosaic of wet, glycophilous meadows, low reed, and sedge beds, adjacent to the narrow (50-60 m) stripe of trees (pedunculate oaks, black alders) along the ditch; during the trapping meadows were freshly mowed and partially flooded |

| VII | ad | A dike (5-10 m wide) between the two canals, covered by a mosaic of sedge communities and willow shrubs, surrounded by black alder swamp forests Ribeso nigri-Alnetum (96 years) from both sides |

| VIII | mh | Active marine cliff with mosaic of early (Trifolio-Anthyllidetum swards with abundant grasses and field wormwood Artemisia campestris) and later (sea-buckthorn Hippophae rhamnoides shrubland) succession stages |

| IX | mh | Surrounding of forester’s lodge – traps located along buildings’ walls, in the garden, on piles of firewood, under shrubs, and in an orchard |

| X | mh | Fertile, woodruff beach forest Galio-odorati Fagetum (125-165 years) with abundant coarse woody debris of natural origin |

| XI | mh | A complex of acidophilic, broadleaved woodlands (90-165 years); the site divided into two shorter trap-lines of equal length: IIa – acid-poor beech forest Luzulo pilosae-Fagetum with traces of recent active restoration (mostly removal of planted Scotch pine) resulting in abundant woody debris, IIb – acid-poor oak-beech forest Fago-Quercetum |

| XII | mh | A complex of coastal woodlands on dunes; the site divided into two shorter trap-lines of equal length: XIIa – pine forest Empetro nigri-Pinetum (52 years), XIIb – acidic birch-oak forest Betulo-Quercetum (65-135 years) |

| XIII | ad | Halophytic mire Glauco-Puccinietalia, consisting of low sward dominated by Juncus gerardi, intensively grazed by cattle, and patches of higher vegetation, including Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani along a flooded depression. |

| XIV | ad | Reed bed Phragmitetum commune, consisted mostly of high reeds, forming an ecotone (10-40 m wide) between birch-oak forest and mowed, glycophilous meadows |

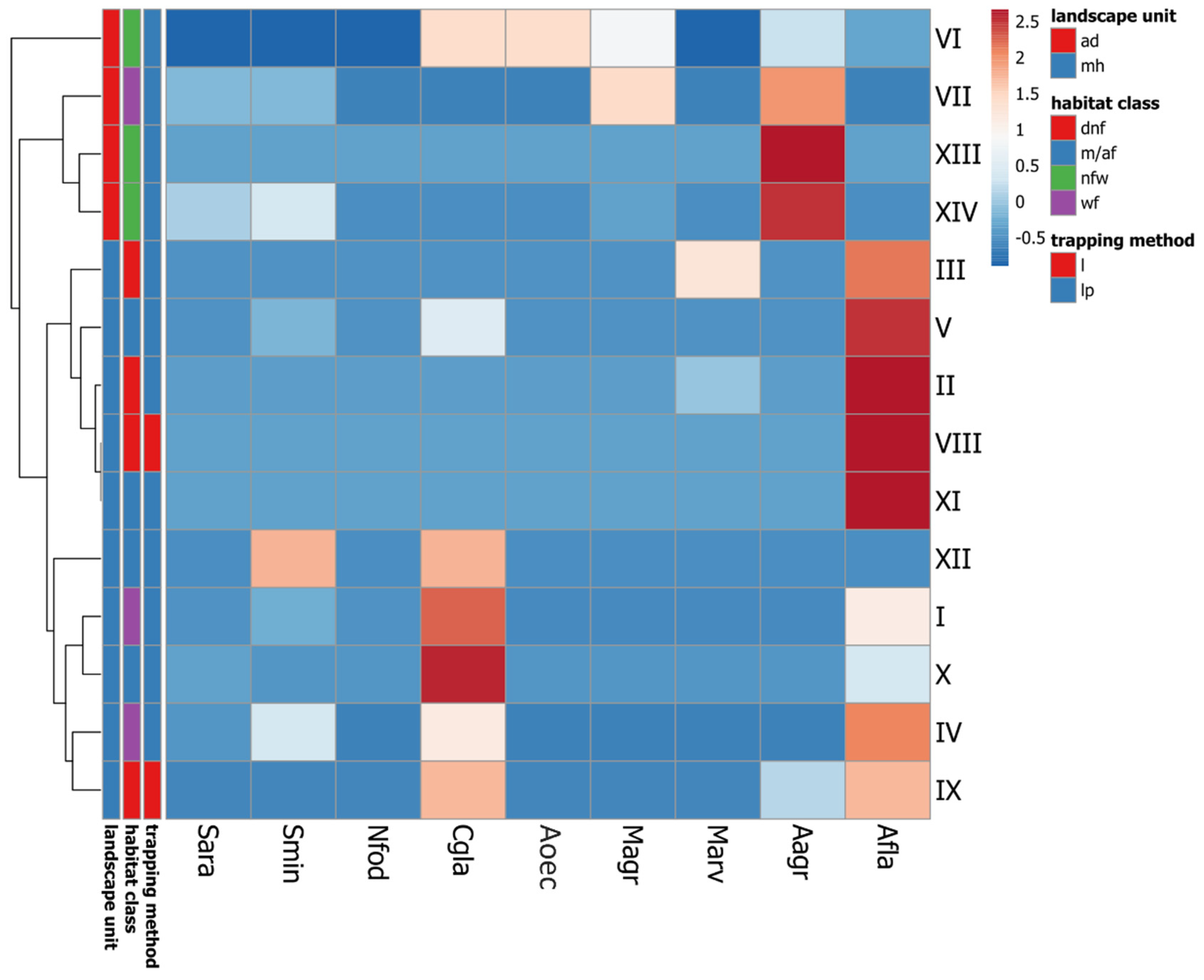

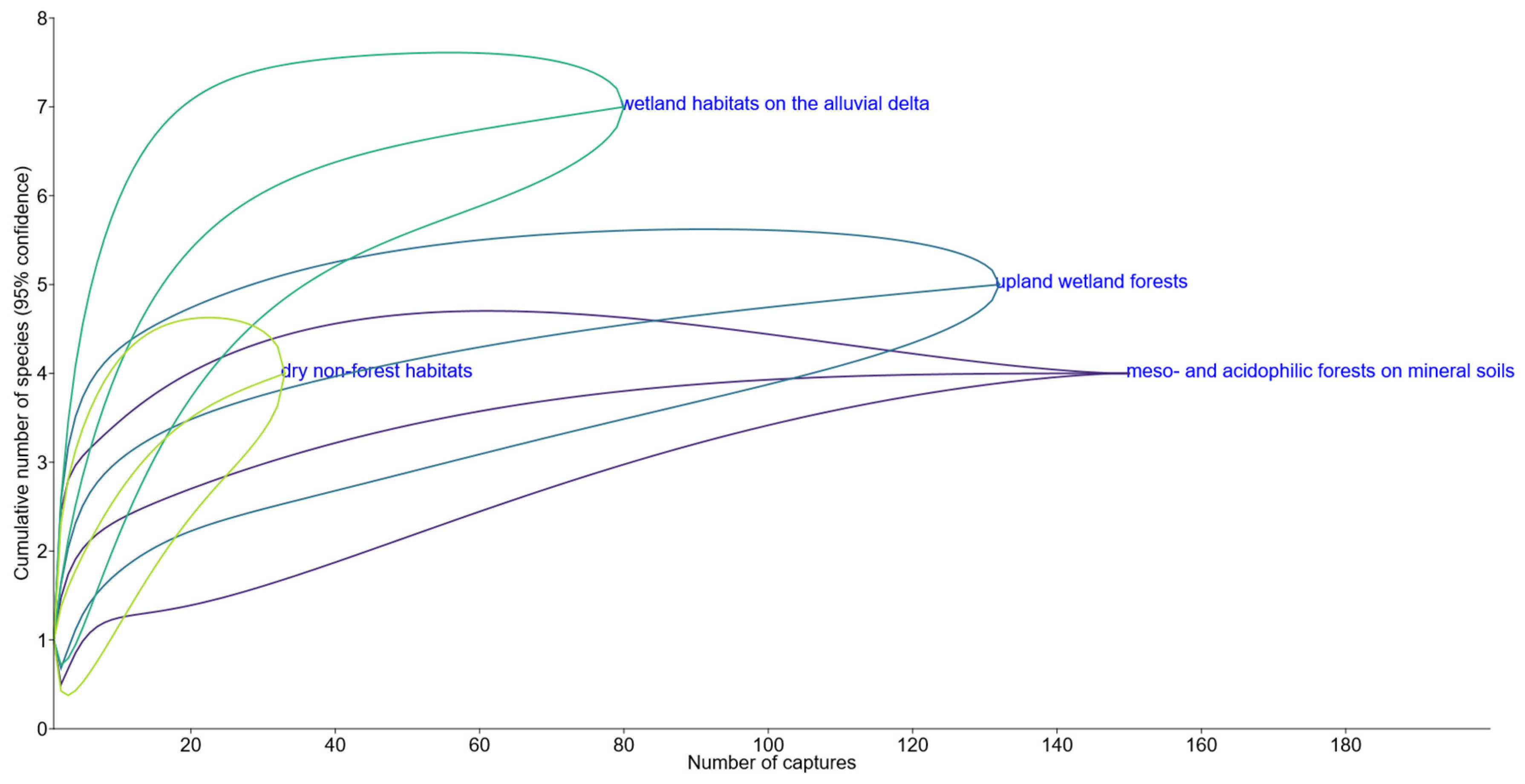

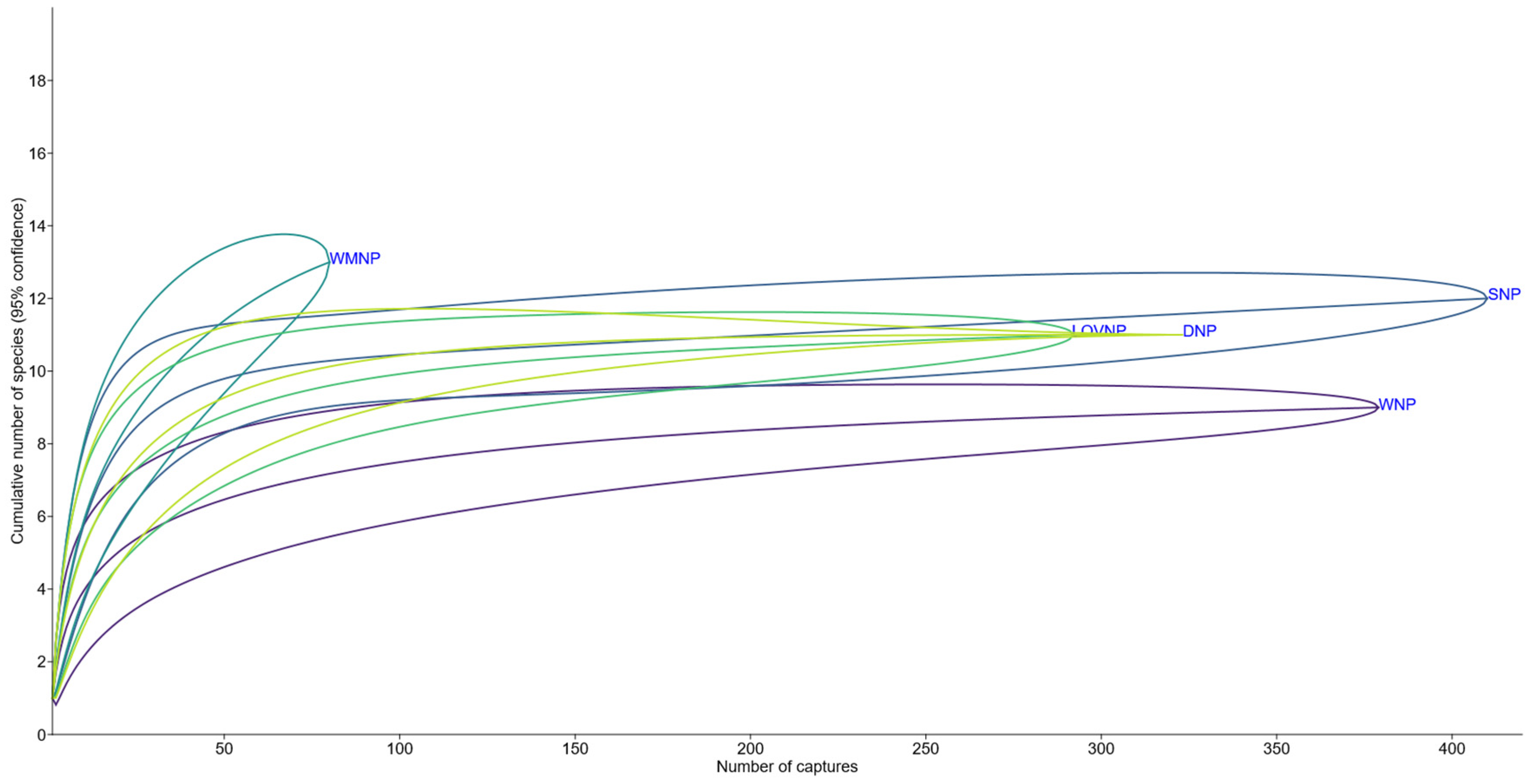

3. Results

4. Discussion

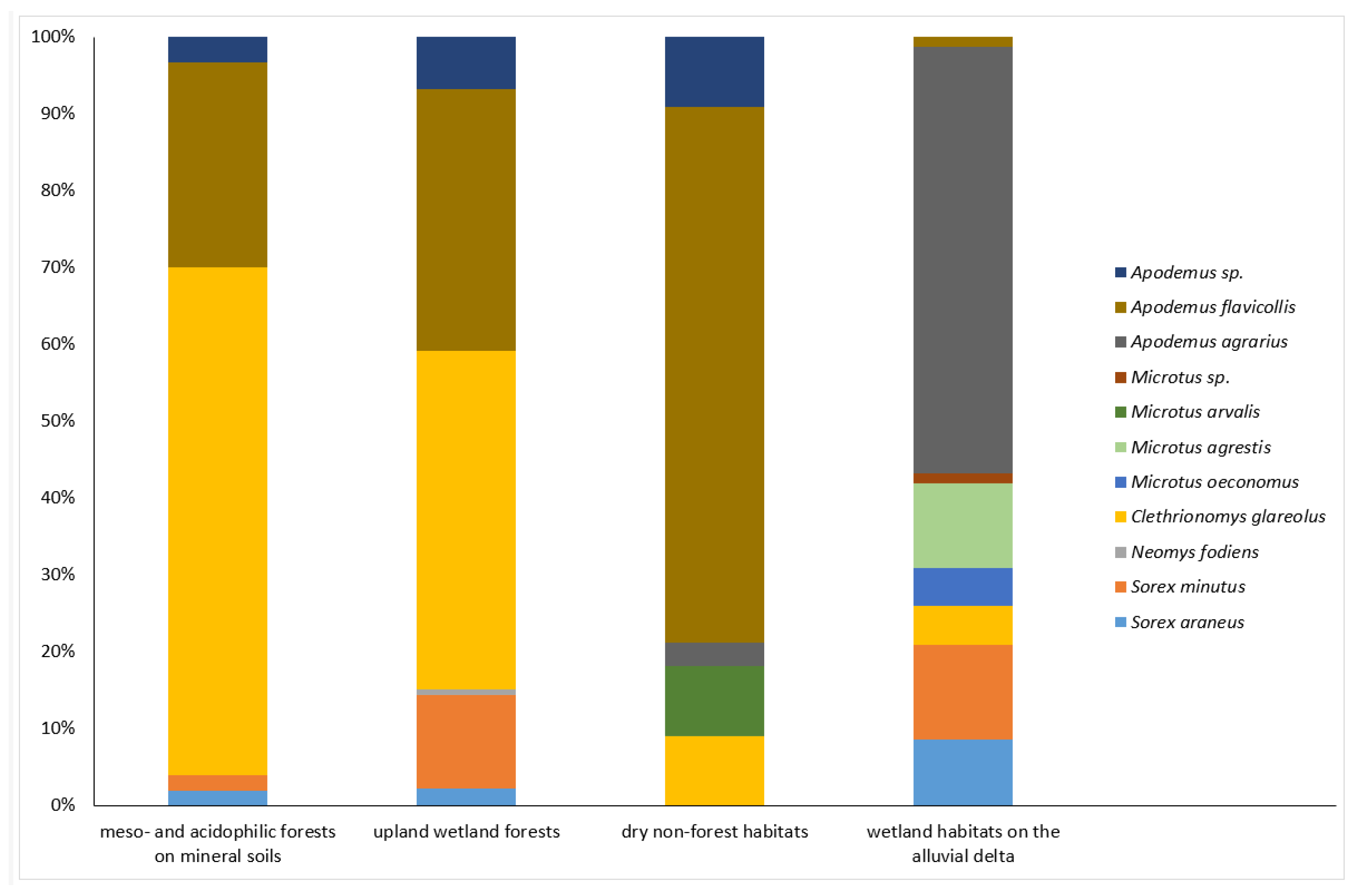

4.1. Species Composition

4.2. Potential Methodological Bias Affecting the Structure of Small Mammal Samples

4.3. Factors Leading to Depauperation of Small Mammal Assemblage

4.4. Structure of Small Mammal Assemblages and Habitat Selection by Particular Species

4.5. Small Mammal Zonation in the Wolin National Park Forced by Topography?

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WNP | Wolin National Park |

| DNP | Drawieński National Park |

| LOVNP | Lower Oder Valley National Park |

| SNP | Słowiński National Park |

| WMNP | Warta Mouth National Park |

| NP | National Park |

References

- Hayward, G.F.; Phillipson, J. Community structure and functional role of small mammals in ecosystems. Ecol Small Mammals 1979, 135–211. [Google Scholar]

- Gardezi, T.; da Silva, J. Diversity in relation to body size in mammals: a comparative study. Am. Nat. 1999, 153, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgin, C.J.; Colella, J.P.; Kahn, P.L.; Upham, N.S. How many species of mammals are there? J Mammal 2018, 99, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, R.B.; Anderson, E.M. Habitat associations and assemblages of small mammals in natural plant communities of Wisconsin. J Mammal 2014, 95, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulak, W. Small mammal communities of the Białowieża National Park. Acta Theriol. 1970, 15, 465–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedziałkowska, M. , Kończak; J., Czarnomska, S.; Jędrzejewska, B. Species diversity and abundance of small mammals in relation to forest productivity in northeast Poland. Ecoscience 2010, 17, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenišťák, J.; Baláž, I.; Tulis, F.; Jakab, I.; Ševčík, M.; Poláčiková, Z.; Klimant, P.; Ambros, M.; Rychlik, L. Changes of small mammal communities with the altitude gradient. Biologia 2020, 75, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirichella, R.; Ricci, E.; Armanini, M.; Gobbi, M.; Mustoni, A.; Apollonio, M. Small mammals in a mountain ecosystem: the effect of topographic, micrometeorological, and biological correlates on their community structure. Community Ecol 2022, 23, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassini, O.; Aghemo, A.; Baldeschi, B.; Bedini, G.; Petroni, G.; Giunchi, D.; Massolo, A. Some like it burnt: species differences in small mammal assemblage in a Mediterranean basin nearly 3 years after a major fire. Mamm Res 2024, 69, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, I.; Ribas, A.; Puig-Gironès, R. Effects of post-fire management on a Mediterranean small mammal community. Fire 2023, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiulionis, M.; Stirkė, V.; Balčiauskas, L. The distribution and activity of the invasive raccoon dog in Lithuania as found with country-wide camera trapping. Forests 2023, 14, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikar, Z.; Ciechanowski, M.; Zwolicki, A. The positive response of small terrestrial and semi-aquatic mammals to beaver damming. Sci Total Environ 2024, 906, 167568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentili, S.; Sigura, M.; Bonesi, L. Decreased small mammals species diversity and increased population abundance along a gradient of agricultural intensification. Hystrix 2014, 25, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołk, E.; Wołk, K. Responses of small mammals to the forest management in the Białowieża Primeval Forest. Acta Theriol 1982, 27, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Venier, L. Small mammals as bioindicators of sustainable boreal forest management. Forest ecology and management 2005, 208, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ważna, A.; Cichocki, J.; Bojarski, J.; Gabryś, G. Impact of sheep grazing on small mammals diversity in lower mountain coniferous forest glades. Appl Ecol Environ Res 2016, 14, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, G.H.; Wilson, M.L. Small mammals on Massachusetts islands: the use of probability functions in clarifying biogeographic relationships. Oecologia 1985, 66, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq SM, A. Multi-benefits of national parks and protected areas: an integrative approach for developing countries. Environ Socio-econ S 2016, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamroży, G. Ssaki polskich parków narodowych: drapieżne, kopytne, zajęczaki, duże gryzonie. Instytut Bioróżnorodności Leśnej; Wydział Leśny Uniwersytetu Rolniczego, Uniwersytet Rolniczy im. Hugona Kołłątaja & Vega Studio Adv. Tomasz Müller: Kraków, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski, M.; Wikar, Z.; Borzym, K.; Janikowska, E.; Brachman, J.; Jankowska-Jarek, M.; Bidziński, K. Exceptionally Uniform Bat Assemblages across Different Forest Habitats Are Dominated by Single Hyperabundant Generalist Species. Forests 2024, 15, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucek, Z. (1984). Klucz do oznaczania ssaków Polski [Key for identification of Polish mammals]. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa.

- Michaux, J. R.; Chevret, P.; Filippucci, M. G.; Macholan, M. Phylogeny of the genus Apodemus with a special emphasis on the subgenus Sylvaemus using the nuclear IRBP gene and two mitochondrial markers: cytochrome b and 12S rRNA. Mol Phyl Evol 2002, 23, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piłacińska, B.; Ziomek, J.; Bajaczyk, R. Drobne ssaki Drawieńskiego Parku Narodowego [Small mammals of the Drawieński National Park]. Bad Fizjogr Pol Zach 1999, 46, 46–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszyn, G.; Rutkowski, T.; Lesiński, G.; Stephan, W.; Salamandra, P. T. O. P. Soricomorphs and rodents of the Ujście Warty National Park and the surrounding area. Chrońmy Przyr Ojczystą 2015, 71, 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik, L. S.; Eichert U., M.; Kowalski, K. Diversity of small mammal assemblages in natural forests and other habitats of the Słowiński National Park, northern Poland - preliminary results. In Nationalpark-Jahrbuch Unteres Odertal; Vössing, A., Ed.; 2020; Volume III, pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Decher, J.; Bakarr, I.; Hoffmann, A.; Jentke, T.; Klappert, A.; Kowalski, G.; Kuzdrowska, K.; Malinowska, B.; Rychlik, L. S. Aktualisierung unserer Kenntnisse über die Kleinsäugergemeinschaften im Nationalpark Unteres Odertal. In A. Vössing (ed.), Nationalpark-Jahrbuch Unteres Odertal 2021, 18, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A.; Jankowiak, Ł.; Modelska, Z.; Piórkowska, K.; Decher, J.; Jentke, T.; Klappert, A.; Kuzdrowska, K.; Malinowska, B.; Sęk, O. W.; Rychlik, L. S. Diversität von Kleinsäugern im nördlichen Teil des Nationalparks Unteres Odertal. In Vössing, A. (ed.), Nationalpark-Jarbuch Unteres Odertal, 2022, 19, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, W. Zur Kleinsäugerfauna der Insel Usedom und Wolin. Dohrniana, Stettin 1934, 13, 176–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pucek, Z.; Raczyński, J. (Eds.) Atlas rozmieszczenia ssaków w Polsce; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, W. Beiträge zur Säugetierfauna Usedom-Wollins. I Abch Ber Pommerschen Nat-forsch Ges Stettin, 1921, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Open Forest Data. Available online: https://dataverse.openforestdata.pl/dataverse/zoo (accessed on 05.05.2024).

- Ciechanowski, M.; Wikar, Z.; Kowalewska, T.; Wojtkiewicz, M.; Brachman, J.; Sarnowski, B.; Borzym, K.; Rydzyńska, A. Department of Vertebrate Ecology and Zoology. University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland, 2023. Unpublished data.

- Gaffrey, G. Die rezenten wildlebenden Säugetiere Pommerns. Doctoral dissertation, Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Skuratowicz, W. Materiały do fauny pcheł (Aphaniptera) Polski. Acta Parasitol Pol 1954, 2, 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, W. Zur Verbreitung der Schlagmäuse in Pommern. I Abch Ber Pommerschen Nat-forsch Ges Stettin 1922, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, W. Zum Vorkommen von Glis glis (L.). Dohrniana, Stettin 1939, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Goc, M. Stanowisko popielicy szarej Glis glis w Słowińskim Parku Narodowym. Przegląd Przyr 2019, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Rathke, D.; Bröring, U. Colonization of post-mining landscapes by shrews and rodents (Mammalia: Rodentia, Soricomorpha). Ecol Eng 2005, 24, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, V.; Colyn, M. Relative efficiency of three types of small mammal traps in an African rainforest. Belg J Zool 2006, 136, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Pucek, Z. Trap response and estimation of numbers of shrews in removal catches. Acta theriol 1969, 14, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, C.; McShea, W. J.; Guimondou, S.; Barriere, P.; Carleton, M. D. Terrestrial small mammals (Soricidae and Muridae) from the Gamba Complex in Gabon: species composition and comparison of sampling tecnhiques. Bull Biol Soc Wash 2006, 12, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Bovendorp, R.S.; Mccleery, R.A.; Galetti, M. Optimising sampling methods for small mammal communities in Neotropical rainforests. Mamm Rev 2017, 47, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankakoski, E. The cone trap—a useful tool for index trapping of small mammals. Ann Zool Fennici 1979, 16, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan, J. , Zejda, J.; Holisova, V. Efficiency of different traps in catching small mammals. Folia Zool 1977, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Darinot, F. Dispersal and genetic structure in a harvest mouse (Micromys minutus Pallas, 1771) population, subject to seasonal flooding; TEL - Thèses en ligne: France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Occhiuto, F.; Mohallal, E.; Gilfillan, G. D.; Lowe, A.; Reader, T. Seasonal patterns in habitat use by the harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) and other small mammals. Mammalia 2021, 85, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziomek, J. Drobne ssaki (Micromammalia) Roztocza. Część I. Micromammalia wybranych biotopów Roztocza Środkowego. Fragm faunist 1998, 41, 93–123. [Google Scholar]

- Juskaitis, R. Peculiarities of habitats of the common dormouse, Muscardinus avellanarius, within its distributional range and in Lithuania: a review. Folia Zool Praha 2007, 56, 337. [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski, M.; Cichocki, J.; Ważna, A.; Piłacińska, B. Small-mammal assemblages inhabiting Sphagnum peat bogs in various regions of Poland. Biol Lett 2012, 49, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell-Jones, A. J.; Mitchell, J.; Amori, G.; Bogdanowicz, W.; Spitzenberger, F.; Krystufek, B.; Reijnders, P J. H.; Spitzenberger, E.; Stubbe, M.; Thissen, J. B. M.; Vohralik, V.; Zima, J. The atlas of European mammals; T & AD Poyser: London; vol. 3. [CrossRef]

- Igea, J.; Aymerich, P.; Bannikova, A. A.; Gosálbez, J.; Castresana, J. Multilocus species trees and species delimitation in a temporal context: application to the water shrews of the genus Neomys. BMC evol biol 2015, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichocki, J.; Kościelska, A.; Piłacińska, B.; Kowalski, M.; Ważna, A.; Dobosz, R.; Nowakowski, K.; Lesiński, G.; Gabrys, G. Occurrence of lesser white-toothed shrew Crocidura suaveolens (Pallas, 1811) in Poland. Zeszyty Naukowe. Acta Biol. Uniwersytet Szczeciński 2014, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl, W.; Kryštufek, B. Spatial distribution and population density of the harvest mouse Micromys minutus in a habitat mosaic at Lake Neusiedl, Austria. Mammalia 2003, 67, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmacki, A.; Gołdyn, B.; Tryjanowski, P. Location and habitat characteristics of the breeding nests of the harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) in the reed-beds of an intensively used farmland. Mammalia 2005, 69, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziński, M.; Jedlikowski, J.; Komar, E. Space use, habitat selection and daily activity of water voles Arvicola amphibius co-occurring with the invasive American mink Neovison vison. Folia Zool 2019, 68, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Putten, T. A.; Verhees, J. J.; Koma, Z.; van Hoof, P. H.; Heijkers, D.; de Boer, W. F.; Esser, H. J.; Hoogerwerf, G.; Lemmers, P. Insights into the fine-scale habitat use of Eurasian Water Shrew (Neomys fodiens) using radio tracking and LiDAR. J Mammal 2025, gyae146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczyński, J.; Fedyk, S.; Gębczyńska, Z.; Pucek, M. Drobne ssaki środkowego i dolnego basenu Biebrzy. Zeszyty problemowe postępów nauk rolniczych 1983, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik, L. Habitat preferences of four sympatric species of shrews. Acta Theriol 2000, 45 (Suppl. 1), 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łopucki, R.; Mróz, I.; Klich, D.; Kitowski, I. Small mammals of xerothermic grasslands of south-eastern Poland. Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences-SGGW. Anim Sci 2018, 57, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, F. H.; Macdonald, D. W.; Hart, B. J.; Manley, W. J.; Feber, R. E. Habitat use by wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) in a changeable arable landscape. J Zool 2001, 255, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gębczyńska, Z.; Raczyński, J. Fauna i ekologia drobnych ssaków Narwiańskiego Parku Narodowego. Parki Narodowe i Rezerwaty Przyrody 1997, 16, 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Suchomel, J.; Purchart, L.; Čepelka, L. Structure and diversity of small-mammal communities of lowland forests in the rural central European landscape. Eur J For Res 2012, 131, 1933–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.C. Responses of small mammals to coarse woody debris in a southeastern pine forest. J Mammal 1999, 80, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T. P.; Sullivan, D. S. Maintenance of small mammals using post-harvest woody debris structures on clearcuts: linear configuration of piles is comparable to windrows. Mamm Res 2018, 63, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejewski, W.; Jędrzejewska, B. Rodent cycles in relation to biomass and productivity of ground vegetation and predation in the Palearctic. Acta Theriol 1996, 41, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, H. P.; Sundell, J.; Ecke, F.; Halle, S.; Haapakoski, M.; Henttonen, H.; Huitu, O.; Jacob, J.; Johnsen, K.; Koskela, E.; Luque-Larena, J.; Lecomte, N.; Leirs, H. , Mariën, J.; Neby, M.; Rätti, O.; Sievert, T.; Singleton, G. R.; van Cann, J.; Vanden Broecke B.; Ylönen, H. Population cycles and outbreaks of small rodents: ten essential questions we still need to solve. Oecologia 2021, 195, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trout, R.C. A review of studies on populations of wild harvest mice (Micromys minutus (Pallas). Mamm Rev 1978, 8, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balčiauskas, L. , & Balčiauskienė, L. Long-Term Stability of Harvest Mouse Population. Diversity 2023, 15, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowski, M.; Fałtynowicz, W.; Zieliński, S. (eds). The nature of the planned reserve “Dolina Mirachowskiej Strugi” in the Kaszubskie Lakeland (northern Poland). Acta Bot Cassubica 2004, 4, 5–137. [Google Scholar]

- Dokulilová, M.; Krojerová-Prokešová, J.; Heroldová, M.; Čepelka, L.; Suchomel, J. Population dynamics of the common shrew (Sorex araneus) in Central European forest clearings. Eur J Wildl Res 2023, 69, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balčiauskas, L.; Balčiauskienė, L. Habitat and Body Condition of Small Mammals in a Country at Mid-Latitude. Land 2024, 13, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucek, Z.; Jędrzejewski, W.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Pucek, M. Rodent population dynamics in a primeval deciduous forest (Białowieża National Park) in relation to weather, seed crop, and predation. Acta Theriol 1993, 38, 199–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, V. V.; Karpenko, S. V. The population dynamics of the water shrew Neomys fodiens (Mammalia, Soricidae) and its helminthes fauna in the northern Baraba. Parazitologiia 2004, 38, 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelczyk, J.; Łabuz, T. Danielewska, A. & Maciag, M., Ed.; Zmiany linii brzegowej oraz powierzchni wyspy Wolin w holocenie i ich wpływ na osadnictwo od mezolitu do czasów współczesnych (Coastline and the surface of the Wolin Island changes in the Holocene and their impact on settlement from the Mesolithic to modern times). In Najnowsze doniesienia z zakresu ochrony środowiska i nauk pokrewnych; Lublin, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bohdal, T.; Navrátil, J.; Sedláček, F. Small terrestrial mammals living along streams acting as natural landscape barriers. Ekológia (Bratislava) 2016, 35, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, F. Comparison of spatial learning in woodmice (Apodemus sylvaticus) and hooded rats (Rattus norvegicus). J Comp Psychol 1987, 101, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawski, C.; Koteja, P.; Sadowska, E. T.; Jefimow, M.; Wojciechowski, M. S. Selection for high activity-related aerobic metabolism does not alter the capacity of non-shivering thermogenesis in bank voles. J Comp Physiol A 2015, 180, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomolino, M. V.; Brown, J. H.; Sax, D. F. Island biogeography theory. The theory of island biogeography revisited 2010, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomolino, M.V. Mammalian island biogeography: effects of area, isolation and vagility. Oecologia 1984, 61, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, E.; Rangel, T. F.; Pellissier, L.; Graham, C. H. Area, isolation and climate explain the diversity of mammals on islands worldwide. Proc R Soc B 2021, 288, 20211879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Yu, M.; Xu, G.; Ding, P. BIODIVERSITY RESEARCH: Nestedness for different reasons: the distributions of birds, lizards and small mammals on islands of an inundated lake. Div Distrib 2010, 16, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinger, E. C.; Khadka, B.; Farmer, M. J.; Morrison, M.; Van Stappen, J.; Van Deelen, T. R.; Olson, E. R. Longitudinal trends of the small mammal community of the Apostle Islands archipelago. Comm Ecol 2021, 22, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, T. R.; Mallinger, E. C.; Farmer, M. J.; Morrison, M. J.; Khadka, B.; Matzinger, P. J.; Kirschbaum, A.; Goodwin, K. R.; Route, W. T.; Van Stappen, J.; Timothy R. Van, Deelen; Olson, E. R. Comparative biogeography of volant and nonvolant mammals in a temperate island archipelago. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltonen, A.; Hanski, I. Patterns of island occupancy explained by colonization and extinction rates in shrews. Ecology 1991, 72, 1698–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, T.S. Island Biogeography of small mammals in Denmark: Effects of area, isolation and habitat diversity. MSc thesis, University of Aarhus, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Girjatowicz, J. P.; Świątek, M. Relationship between air temperature change and southern Baltic coastal lagoons ice conditions. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchomel, J.; Purchart, L.; Čepelka, L.; Heroldová, M. Structure and diversity of small mammal communities of mountain forests in Western Carpathians. Eur J For Res 2014, 133, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolak, R.; Witczuk, J.; Bogdziewicz, M.; Rychlik, L.; Pagacz, S. Simultaneous population fluctuations of rodents in montane forests and alpine meadows suggest indirect effects of tree masting. J Mammal 2018, 99, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowski, J.; Dudek-Godeau, D.; Lesiński, G. The Diversity of Small Mammals along a Large River Valley Revealed from Pellets of Tawny Owl Strix aluco. Biology 2023, 12, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornulier, T.; Yoccoz, N. G.; Bretagnolle, V.; Brommer, J. E.; Butet, A.; Ecke, F.; Framstad, E.; Henttonen, H.; Hörnfeldt, B.; Huitu, O.; Imholt, C.; Ims, R. A.; Jacob, J.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Millon, A.; Petty, S.; Pietiäinen, H.; Tkadlec, H.; Zub, K.; Lambin, X. Europe-wide dampening of population cycles in keystone herbivores. Science 2013, 340, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haitlinger, R. Arthropod communities. Acta Theriol 1983, 28 (Suppl. 1), 55–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodziński, W. The succession of small mammal communities on an overgrown clearing and landslip in the Western Carpathians. Bull Acad Pol Sc, Cl. II 1958, 6, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdziewicz, M.; Zwolak, R. Responses of small mammals to clear-cutting in temperate and boreal forests of Europe: a meta-analysis and review. Eur J For Res 2014, 133, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mažeikytė, R. Small mammals in the mosaic landscape of eastern Lithuania: species composition, distribution and abundance. Acta Zool Litu 2002, 12, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šinkūnas, R.; Balčiauskas, L. Small mammal communities in the fragmented landscape in Lithuania. Acta Zool Litu 2006, 16, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, R.; Maldonado, J. E.; Droege, S. A. M.; McDonald, M. V. Tidal marshes: a global perspective on the evolution and conservation of their terrestrial vertebrates. BioScience 2006, 56, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuil, Y. I.; van Guldener, W. E.; Lagendijk, D. G.; Smit, C. Molecular identification of temperate Cricetidae and Muridae rodent species using fecal samples collected in a natural habitat. Mamm Res 2018, 63, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.T.; Jensen, T.S. Småpattedyrfaunaen på Anholt og Sprogø. Flora og Fauna 2024, 129, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ambros, M. Drobné cicavce (Mammalia: Soricomorpha, Rodentia) území európskeho významu: slaniská a slané lúky. Naturae Tutela 2018, 22, 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, A.; Kindlmann, P.; Sedlacek, F. Barrier effects of roads on movements of small mammals. FOLIA ZOOL-PRAHA 2007, 56, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejewski, R.; Babińska-Werka, J.; Gliwicz, J.; Goszczyński, J. Synurbization processes in population of Apodemus agrarius. I. Characteristics of populations in an urbanization gradient. Acta Theriol 1978, 23, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiński, G.; Gryz, J.; Krauze-Gryz, D.; Stolarz, P. Population increase and synurbization of the yellow-necked mouse Apodemus flavicollis in some wooded areas of Warsaw agglomeration, Poland, in the years 1983–2018. Urban Ecosyst 2021, 24, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangil, B. D.; Rodríguez, A. Environmental filtering drives the assembly of mammal communities in a heterogeneous Mediterranean region. Ecol Appl 2023, 33, e2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sara | Smin | Nfod | Cgla | Aoec | Magr | Marv | A/M | Aagr | Afla | Asp | |||

| I | 1 | 4 | 1 | 37 | - | - | - | - | - | 16 | 6 | 65 | 4 |

| Site/habitat | Species | total | S | ||||||||||

| IIa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 7 | 1 | 9 | 2 |

| IIb | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 |

| III | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| IV | 2 | 12 | - | 21 | - | - | - | - | - | 29 | 3 | 67 | 4 |

| V | - | 2 | - | 6 | - | - | - | - | - | 16 | 2 | 26 | 3 |

| VI | - | - | - | 4 | 4 | 3 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | 15 | 5 |

| VII | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | 5 | - | - | 11 | 4 |

| VIII | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | - | 12 | 1 |

| IX | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | - | 7 | 3 |

| X | 3 | - | - | 92 | - | - | - | - | - | 21 | 3 | 119 | 3 |

| XIa | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 1 |

| XIb | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 |

| XIIa | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| XIIb | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| XIII | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | - | - | 8 | 1 |

| XIV | 6 | 9 | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | 30 | - | - | 47 | 4 |

| total | 13 | 29 | 1 | 164 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 46 | 110 | 17 | 397 | 9 |

| % | 3,3 | 7,3 | 0,3 | 41,3 | 1,0 | 2,3 | 0,8 | 0,3 | 11,6 | 27,7 | 4,3 | 100,0 | |

| number of habitats | 5 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 2 | - | 5 | 12 | - | 17 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).