1. Introduction

The Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber Linnaeus, 1758) is the last recorded mammal species in Bulgaria, despite its impressive size, the specific visible traces it leaves by biting the trunks of large trees and its permanent establishment in Bulgaria more than 15 years ago. Sensationally, for the first time in March of 2021, this giant rodent was photo-documented in the area of the confluence of the Cherni and Baniski Lom rivers (Kodzhabashev et al. 2021). Meanwhile, traces of beaver activities were also found in the same region by Natchev et al. (2021). Since then until the beginning of 2025, we studied and demonstrated the permanent and large-scale incognito settlement of numerous beaver families along the entire 470 km length of the Danube River, on all its islands and on seven of the Danube tributaries – the Timok, the Lom, the Ogosta, the Iskar, the Osam, the Yantra and the Rusenski Lom Rivers (Кodzhabashev 2022, Кodzhabashev et al. 2022, 2023, 2025 and a paper in preparation).

Studies on the Eurasian beaver are extremely diverse in their subject and are related to different aspects of the species, its importance for the territories it inhabits and the changes that occurred after its mass killing in the 18th and 19th centuries. Particular attention is paid to the subsequent reintroductions in the 20th and 21st centuries that led to the recovery of its range, as well as to the dynamics of its modern distribution and the acquisition of new territories. Conservation and management action plans have been developed in the countries where the Eurasian beaver has recovered and its densities are now relatively high, creating opportunities for a conflict with humans. Monographic sources on various aspects of the species are numerous and are mostly by authors who have studied the beaver for decades and have been actively involved in its recovery. Notable works related to the study of taxonomic, biological and ecological features of natural and reacclimatized beaver populations, their dynamics and habitat changes include those by Khlebovich (1938), Fedyushin (1935), Ognev (1947), Barabash-Nikiforov (1950), Skalon (1951), Poyarkov (1953), Lavrov (1961, 1981), Dyakov (1975), Dezhkin et al. (1986), Balodis (1990), Danilov (2007), Dgebuadze et al. (2012), Zavyalov and Khlyap (2018), Rosell and Campbell-Palmer (2022).

The Eurasian beaver is a monogamous, highly territorial, amphibiotic rodent whose main diet consists of wood cellulose obtained by gnawing on stems of shrubs and tree trunks, through which activities the species involuntarily demonstrates its presence. In all quantitative studies on the Eurasian beaver, the main subject is the family groups, their numbers, age structure and the occupied family territory. The methods applied to establish the number of family groups and their individuals are based on direct and indirect traces of their life activities, direct observations and subsequent quantitative reporting. Dyakov (1975) summarised, analysed and divided all the methods of quantitative study on the Eurasian beaver that were introduced and experimented by his predecessors into 4 main groups: statistical, ecological-statistical, morpho-ecological and expert-measurement of the total family capacity (family “power”).

The statistical method was firstly applied by Khlebovich (1938) and is based on accurately identifying and counting of beaver family groups in a given territory, after which a conversion factor is calculated representing the arithmetic mean of the number of individuals participating in the family. The calculation of this coefficient can be done in different ways, by direct and indirect means, the basis of which is the determination of the exact number of individuals in each family group. The variation of the coefficient is in the range of 2.5 to 5 individuals and depends on many environmental factors. The method is relatively simple and fast, which is why it is very often applied to both the Eurasian beaver and the North American beaver accounts in the USA and Canada, when a quick expert estimate of numbers for large territories is needed. For the purpose of the biological extrapolation, an average transformation factor of 4 is used (Dyakov 1975), which means that each established family group contains on average 4 individuals. Zharkov (1960) applied a modification of this method by using an aerial camera to snapshot beaver huts (lodges) and felled trees in the Eurasian beaver lake ecological form in areas where the species is in relatively low density and no other means of passing are possible through the extensive floodplains.

The main merit of these methods is the relatively rapid result for the total number of individuals in large areas; Diakov (1975) points out as a disadvantage the lack of possibility for the exact establishing of the distribution of individuals by family groups, as well as the considerable degree of assumption of the whole information. The method allows for subjective assessment, i.e., error, and therefore the overall quantitative assessment is not entirely accurate. In other words, the accuracy of the method is within certain limits, which are acceptable in the absence of other mechanisms for fast counting.

The statistical method has been updated and simplified by Kondratov et al. (2017) through a new method for calculating the conversion coefficient (the average number of individuals in the family group) using the percentage of breeding families relative to all established families. This information is transformed into a corresponding numerical coefficient in a table, depending on the established percentage ratio. The method used in the past to determine the conversion coefficient was through complete capture (killing or radio identification) of a certain percentage of family groups, which made this research technique cruel, laborious, slow and expensive.

The group of morpho-ecological methods for quantitative study of the beaver is based on indirect measurement of body dimensions, which depend on the size and age of the individuals. They were first applied by Fedushin (1935), who used the size, shape, and structure of the incisor marks left by the animals when feeding, as well as the size of the hind footprints, to determine three size-age structures, which are used to determine the number of individuals in the family group. According to Dyakov (1975), this method is more accurate than the statistical method and those applied by Lavrov (1952), in which the number of individuals in a family group is estimated by visually assessing the total number of traces left by that group. The main advantage of this method is the relatively quick and easy determination of size groups and individuals, which provides information about the size of each family group. The disadvantages include the inability to determine the exact number of individuals when one age-size class is established, i.e., whether there are one or more individuals, as well as the inability to determine the presence of two or more year-old animals remaining in the family group, given the overlap in body size of all individuals aged 2+. A modification by Kondratov et al. (2017) of the Lavrov’s (1961) method of the total “power” of the family expression, specifies how to identify and distinguish a single adult animal from a formed family couple, or from individuals remained in the family after their second year.

The third group of methods for quantitative reporting on beavers’ family groups is the ecological-statistical methods (Dyakov 1975), first developed by Poyarkov (1953), but introduced by Ponomarev (1938) and supplemented by Dyakov (1959). This type of methods consists of a complete counting and classification of all traces of beaver activity in each occupied family territory, if possible, with subsequent determination of the number of animals based on this data. With these methods, all registered signs of life activity are recorded and entered into a table, and values are then calculated based on the number of members in the specific family group. First, all fresh gnaw marks are assessed. They are recorded by the number and size of the felled and cut bushes and trees and their degree of assimilation. The number of exits, beaver trails, volume of the food store during the autumn-winter period, and number of dens and huts, if any, are recorded. Kudryashov (1969, 1970) simplified and improved the method and developed the form of the tables for recording the number of individuals according to the different types of life traces and their quantitative values. This group of methods is the most accurate, despite the laborious and slow process of determining the number of individuals, and is recommended for protected areas and for calculating the conversion coefficient when applying the statistical method. In a simplified and modernized form (Kondratov et al. 2017), the method is used when a detailed study of the capacity and current state of the habitat is needed for the purposes of a long-term monitoring of the species.

The fourth group of methods was developed by Lavrov (1952) and is known as the method of manifestation of the total power of the family group. The total number and distribution of the family group life traces are determined by expert estimation by sight, which is used to determine the number of individuals in the group. This counting technique requires a very high degree of specialisation and field experience on the part of the expert and suffers to some extent from subjectivity if the researcher does not have the necessary qualifications and ability to realistically assess the quantitative indicators of the life traces (according to Dyakov 1975). Kondratov et al. (2017) refine and simplify the technique for recording and assessing the total power of the established life traces of a particular family group and develop a methodology for valuing and quantitatively assessing the number and type of individuals in a given occupied family territory, referring to methodologies developed by Lavrov (1961) and Dyakov (1975).

The methods of radio telemetry and photo trapping commonly used in a number of European countries are not suitable for large-scale studies, because they are expensive, require numerous qualified teams of experts, high-tech expensive equipment, annual capture of large numbers of individuals for tagging (capture, anesthetize, and tag all zero-year-old beavers), and are applicable only to some limited in size and type areas.

The goal of our study was to compile and describe a set of methods for surveying the Eurasian beaver, which are inexpensive, effective, and easy to apply. Depending on the season and the use of specific methodologies, in many cases we have applied rationalizations of the techniques and corresponding methods. We wanted to experiment and to analyse the results obtained, and to find the most rational approach in studying the beaver, based on our current knowledge. We also wanted to build a database for the species, which would be continuously supplemented, updated, and used by those sympathetic to our nature conservation cause. Part of our goal was, through mass public advocacy, promotion, and the development of an information system based on citizen science, as well as through interactive and remote learning methods, to attract interested citizens and nature enthusiasts as volunteers and to experiment with the possibilities of collecting and documenting classified information about the beaver in Bulgaria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Periods

We conducted our experimental study on the beavers in Bulgaria between March 2021 and March 2025. We explored the following model study areas (rivers): 1) As a model for a very large river – the Danube (bank, Danube islands); 2) As a model for large rivers – Rusenski Lom and Yantra; 3) As a model for medium-sized rivers – Cherni Lom and Beli Lom (tributaries of the Rusenski Lom) and Rositsa (tributary of Yantra); 4) As a model for small rivers – the tributaries of Beli Lom, Cherni Lom and Rositsa.

Registrations and mapping were conducted as follows:

• The Danube and its islands – along coastal transects – in August and September 2022, August 2023, August and September 2024;

• Rusenski Lom River (and the tributaries Cherni Lom, Baniski Lom, Beli Lom) – in March 2021 – March 2025;

• Yantra River (the tributaries Rositsa and Negovanka and Yantra near the town of Byala) – in September 2021 – March 2025.

2.2. Equipment Needed for Studying the Eurasian beaver

GPS, photo camera (could be replaced with a mobile phone with a GPS app and dash camera), measuring tape, ruler, field notebook, pencil and pen, binoculars, pruning shears, saw, digital pedometer, tubes with ethanol, camera traps.

2.3. Methods Used to Record the Beaver Presence

Our new synthetic method for studying beavers is based on the refinement, calibration, and combination of techniques and methodologies used by Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian specialists, who have extensive and large-scale field experience acquired from studying natural autochthonous populations and from restoring the species in vast areas where it had been exterminated. These research techniques and methodologies are unknown or little known to the Western European scholars due to the linguistic barrier that existed in the past.

1) Citizen science – it is based on information on beaver sightings reported by citizens after organized mass public campaign, which included popular science publications, print and electronic media, information boards and posters. Online information was provided to state and public authorities and institutions, NGOs. For group communications in virtual space, public presentations, photos, and videos created with our materials were uploaded. Registrations of the species were also based on information from inquisitive and curious citizens, nature lovers, and government officials by locating the site (with a mobile phone) and then visiting the site.

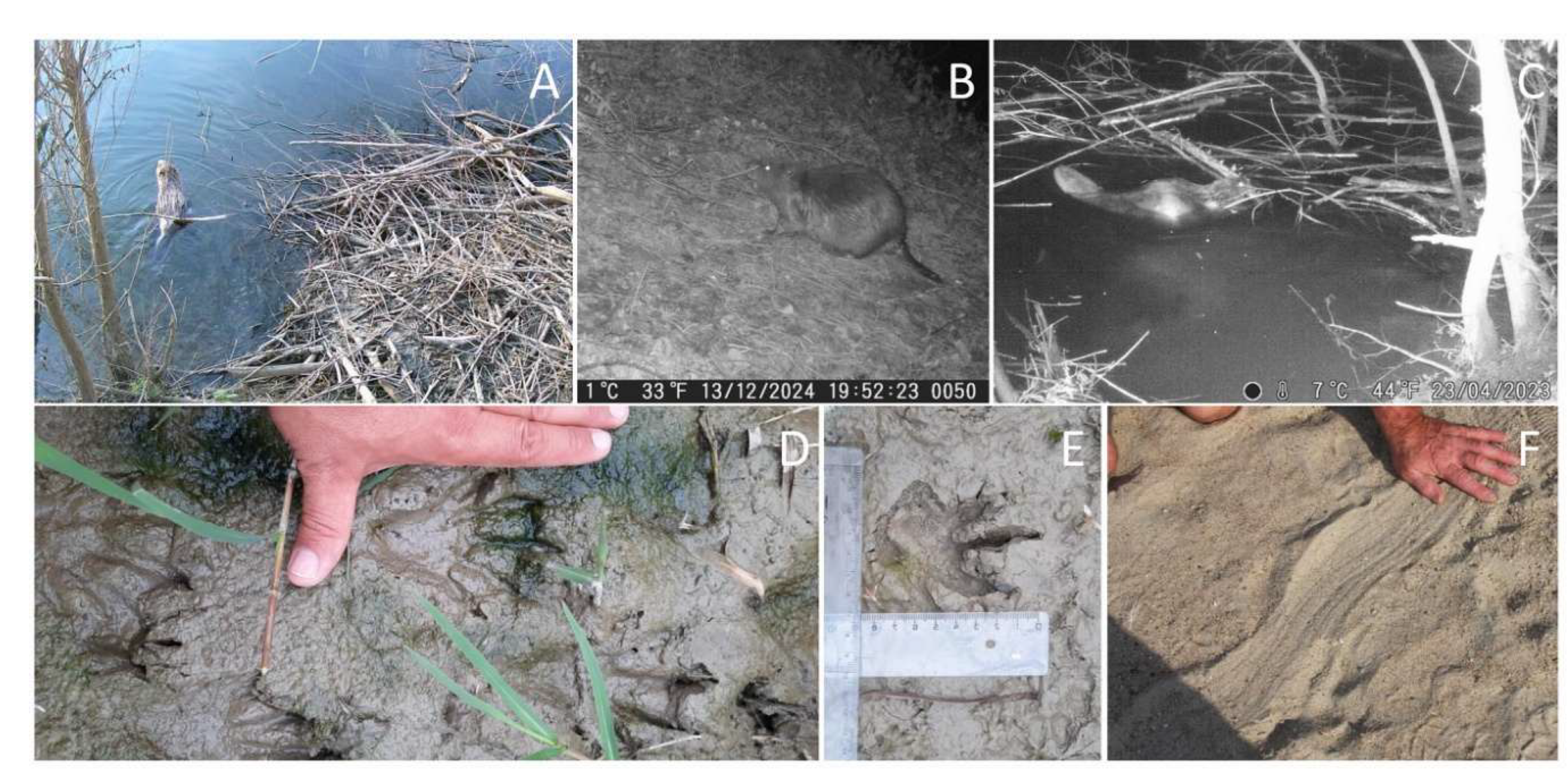

2) Direct registrations (visual contact) (

Figure 1) – three more amphibious mammal species are found in the study areas, the identification of which in aquatic and terrestrial environments requires some experience and practice. The main characteristics used to identify the four species were the size, tail shape, body proportions, body position, mode of movement in aquatic environments, and behaviour. In poor lighting conditions and with poor recordings or photographs of swimming animals, identification is not always possible and requires mandatory evidence of specific and recognisable traces of life activities, usually gnaw marks (

Figure 2).

3) Indirect registrations – they are based on traces of life activities – gnawed tree trunks, footprints on the coastal surface, tail drag trails on the sand, marking elements, feeding areas and storage areas, dens, construction of dams, beaver paths, ditches and canals, sound signals of gnawing or felling of trees, tail slaps when frightened. The methodology used for measuring footprints (

Figure 1D, E) and other traces (

Figure 2E, G, H) is based on Formozov (2006) and Oshmarin and Pikunov (1990).

2.4. Methods for Quantitative Reports on the Number of Family Groups and Individuals

1) Determining the boundary of the occupied family territory – initial establishment of the feeding epicentre of the family group and subsequent search for the border with the neighbouring group or abandoned and unoccupied territory. The place where the traces of activity disappear completely or are incidental is considered the boundary between two occupied family territories or the end of the occupied territory. This boundary is 100 – 200 to 300 linear meters. An occupied territory is considered to be actively used when there are fresh traces from the last few (2–3) days. If all gnawing marks are old and there are many new tree shoots, the territory is considered abandoned, and if there are no traces of life, the territory is considered unoccupied. In the absence of suitable habitats – rocky gorges, modified and deforested banks, destroyed feeding habitats – the area is considered unsuitable. When walking along a riverside transect, a GPS track is activated, on which the type of coastal habitat is marked and recorded by marking coordinates – occupied (inhabited) family territory, abandoned territory, uninhabited territory, unsuitable territory. If it is impossible to determine the boundary between two beaver family groups, it is sufficient to determine their feeding epicentres, and the point in the middle of the coastal contour is marked as a conditional boundary.

2) Determining the number of members of the family group

Using the morpho-ecological method based on the size of incisor marks, hind footprints and the width of the trail left by the dragging of the tail (

Table 1). With this method, it is assumed that if one size class of tracks is found, there are 1–2 individuals; if two size classes are found, there are 3–5 individuals; and if three size classes of tracks are found, there are 6–8 individuals in the family group. When one size class is registered and it is only of adults, Lavrov’s rule (1961) is applied to determine the number of individuals, i.e., whether it is a solitary animal or a beaver family. If the occupied territory is inhabited by a single adult animal, there are no concentrated gnaw marks on bushes and trees (no feeding epicentre), there are 3–5 fallen trees, there are 50–70 gnawed branch remnants and there is no winter food storage. The path to the feeding site is single and slightly trodden. If a family has formed, necessarily there is a distinct food epicentre and a winter food storage and the paths are heavily trodden. The boundaries with neighbouring occupied territories are clearly distinguishable.

2.2. Using Poyarkov’s Methodology from the Ecological-Statistical Method

Determination of the number of individuals based on the quantity and quality of the gnawed trunks and branches using the method of Poyarkov (1953) (based on the number of gnaw marks), with modifications by Kondratov et al. (2017). With this laborious method, which is good for accurately determining the number of individuals in the family group and calibrating the quantity of life activity traces, all gnaw marks in the family territory are recorded and then converted into food units in three consecutive tables, finally accounting for the number of individuals in the studied family group. For details, see

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 (representing, respectively,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 on pp. 42–43 in Kondratov et al. (2017).

2.3. Using Kondratov’s Methodology from the Statistical Method

According to the statistical method, when more than one size-age class of individuals is proven and it is impossible to establish more traces of the family group’s life activities, it is assumed that the conversion coefficient (expressing the average number of individuals in a family, based on a large number of family groups, calculated by direct or extrapolative approach) is 4, i.e., the family consists of two adults and two zero-year-olds. This approach is very often used when studying the abundance of large territories for both species of beavers, and practice has shown that when express data on their abundance is needed, this extrapolation is entirely permissible and acceptable. This approach was applied provided that there are two clearly distinguishable size-age classes of tracks and when only traces of zero-year-olds are detected, which would not survive on their own. The simplified version of calculating the conversion coefficient is based on the percentage ratio of family groups that have reproduced and have a presence of zero-year-old individuals. Determination of the correction coefficient (average number of individuals in a family group) based on the percentage ratio of breeding family groups to their total number according to the

Table 5 (representing Table 6 in Kondratov et al. (2017).

Table 5.

Determination of the correction coefficient (average arithmetic number of individuals in a family) based on the number of beaver families with established this year’s (zero-year-old) beaver cubs (recorded reproduction.

Table 5.

Determination of the correction coefficient (average arithmetic number of individuals in a family) based on the number of beaver families with established this year’s (zero-year-old) beaver cubs (recorded reproduction.

| Number of families with zero-year-old cubs, % |

Correction coefficient (average number of individuals in a family) |

| < 34% |

2,5 ind. |

| 35–51 |

3,0 |

| 52–59 |

3,5 |

| 60–72 |

4,0 |

| > 73 |

4,5 |

2.4. Determining the Total “Power” of the Family Group’s Life Traces

Using Kondratov’s modified methodology from Lavrov’s method, we applied techniques for determining and distinguishing the territory occupied by a single animal from that of a formed family couple, as well as assessing and distinguishing sexually mature individuals from two-year-olds which had not dispersed and remained in the family group.

2.5. Sequence Used in the Study of the Eurasian beaver in Established Sites in Bulgaria

1) Registration of the species’ locations using citizen science and direct survey methods; 2) Determination of the boundaries and feeding epicentres between family groups in the studied location using direct survey or biological extrapolation methods; 3) Mapping family groups in the locality using direct survey and biological extrapolation methods; 4) Determining the number of individuals in family groups in the habitat through direct counting or biological extrapolation; 5) Calculation of the number of individuals in the locality; 6) Summing up the family groups and individuals; 7) Plotting the sites on a large-scale river map with sequential numbering, taking into account their order of registration and, respectively, the pace and scale of colonization.

2.6. Meaning of the Terms Used

Field transect – a coastal section of a river that has been surveyed by a field expert and where all traces of Eurasian beaver activity have been recorded, including feeding sites and boundaries between family groups, as well as all morphometric imprints relevant to the size-age class of the individual and, respectively, to the number of members of the beaver family, which is measured in km and in which, in addition to the occupied territories, abandoned areas, unoccupied and unsuitable territories are also recorded and registered with coordinates.

Locality – occupied or abandoned by the family group(s) riverside territory, in which the number of families can vary from 1-2 to 50-100 and more. For each large locality, with more than 10 family groups, the modified statistical method is used to establish the correction coefficient, while for smaller sites, the number of family group members is calcilated using the methodologies for complete mapping of the morpho-ecological and eco-statistical methods.

Biological extrapolation – a technique for determining the abundance in large (lengthy) areas where environmental conditions are similar and a uniform density of beaver family groups is assumed. For example, coastal habitats on Danube islands with dense natural riparian vegetation that is impenetrable and does not allow for direct visual contact.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gathering Information Through Popularising, Educational, and Media Campaigns

Promoting information about the Eurasian beaver in Bulgaria proved to be extremely important and successful for the future study of the species, especially with regard to its distribution. As a newly established species, although proven to be autochthonous to Bulgaria in the recent past (Boev 1958, 1975; Boev and Spasov 2019), the unclear status of the species proved to be an obstacle to the legal mechanisms for financing our research. The official information on the registration of the beaver in Bulgaria was published on 22 September 2021 in the scientific journal Acta zoologica bulgarica, and just a few days later, on 2 October 2021, this interesting and sensational event was reported on the website Geograf.bg, which attracted the attention of the national print, electronic, and online media. Shortly after the media campaign, we began to receive information about new sites and traces of beaver activity in various areas of northern Bulgaria, mainly along the Danube and its islands. Particularly strong interest aroused the popular science article published in issue 5 (May) of the “Hunting and Fishing” magazine (Kodzhabashev 2022), which is the main source of information for members of the Union of Hunters and Fishermen in Bulgaria.

Since this initial information campaign until the end of 2021, we collected information about 12 new sites scattered throughout the Danube and three of its tributaries, and by the end of 2022, we had a total of 21 new sites registered, 13 of which were on Danube islands. The main method used to identify the species was the documentation of tree trunk gnawing and, in a small number of cases, direct observation of swimming or resting animals.

Referring to the Habitats Directive (Articles 4, 12, and 22), where the Eurasian beaver is listed as a species for which Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) are established in the Natura 2000 network, in October 2021, we made a proposal to include the species in Annexes 2 and 3 of the Biological Diversity Act (BDA 2002) (Notifications from 8.10.2021 and 22.12.2022 with authors Kodzhabashev and Teofilova). Notification of the responsible, nature conservation and other affected state institutions (Ministry of Environment and Water of the Republic of Bulgaria, National Nature Conservation Service, Executive Environment Agency, Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Executive Forests Agency, Executive Agency for Fisheries and Aquaculture) and nature conservation NGOs also contributed to the collection of new and useful information about the species, which formed the basis of the planned large-scale study.

Through this information method and subsequent in-situ verification, by spring 2025, we have received over 180 reports of beaver presence in more than 50 sites scattered across the entire 450-kilometer sector of the Danube and seven of its tributaries at a distance of up to 160 km from their mouths (Marinova et al. 2025, Bradley and Deleva 2025, Kodzhabashev et al. unpublished results, in preparation).

Along with gathering information about new localities, public presentations, posters and ongoing media campaigns throughout the years also aimed to popularize the new species and serve educational purposes, which were at the heart of our conservation strategy for the Eurasian beaver. It was emphasized and explained to the general public that the beaver is of great importance for the restoration and maintenance of rivers and riparian habitats, which is why we must protect it, strive for its restoration, and inform interested parties about any contact with the species. Beaver is a key species that positively affects all hydrobionts and river habitats, as well as the very existence of the river body itself, by regulating river flow and increasing the floodplain (Dgebudze et al. 2012, Zavyalov and Khlyap 2018, Rosell and Campbel-Palmer 2022). Thus, the people’s knowledge of this species is of exceptional conservation importance, as well as the promotion of the idea that there will be no second chance for the recovery of the species after its almost complete destruction in the last century.

For the first time, through the massive promotion of a newly established in Bulgaria species protected by European legislation, a mechanism for the public collection of biological information from the media, state institutions, NGOs, nature lovers and curious citizens was experimentally applied, and a scheme for creating of an electronic database through citizen science was developed.

3.2. Direct Observations. Identification of Species and Age Status

Direct observations of beavers (individuals, family groups and footprints) are rare and accidental for non-specialists and require certain knowledge related to professional experience and practice. For most of the year, beavers are nocturnal and lead a secretive lifestyle, which makes them difficult to observe. The information initially collected on beaver observations was systematised and subsequently analysed. Regarding the daily activity of the newly established beaver population in Bulgaria, we were able to gather valuable information from camera traps installed near two family groups on the Cherni Lom River (near the village of Shirokovo) and the Yantra River (near the town of Byala) between March 2021 and March 2025. We use the recorded photos and videos for self-training and for verifying data and biological information when developing methodologies for studying the species based on traces of its life activities and direct observations.

Over the past century, during the reintroduction and reacclimatization of the Eurasian beaver in Europe and Asia, the North American species (Castor canadensis Kuhl, 1820) was also introduced in several European countries too. It still exists in the northernmost regions of Europe (Finland and northwestern Russia) and Asia (the Far East of Russia) (Danilov and Fyidorov 2016, Hollender et al. 2017, Fyodorov and Krasovsky 2019), as well as in parts of Western Europe (Belgium, Liechtenstein, and Germany) (Pigueur et al. 2024), where this alien species has been declared invasive.

Distinguishing the Eurasian beaver from the North American beaver through direct observation in the wild is not always possible and requires detailed and prolonged observation of the animal or photographic documentation and mandatory subsequent analysis of the recorded morphological features. The need to distinguish between the two species is undeniable. Bobeva et al. (2025), without arguments or analytical evidence, put forward a hypothesis based solely on a biased opinion that there are no morphological differences between the two species and that the only way to identify them is genetically. The authors base their analyses and conclusions on an insignificant number of samples from a relatively small area of the species’ current habitats in Bulgaria, ignoring the information published by Kodzhabashev (2022), as well as data from recolonizations carried out in the neighbouring Danubian countries of Romania and Serbia and the subsequent expansion along the Danube, reflected in a number of articles (Cirovic et al. 2013, Smeraldo et al. 2017, Pasca et al. 2018, Fedorca et al. 2021, Dragovic 2022). Lavrov (1981) points out that the main differences between the two species are in the colouring of the coat, the colour of the hair on the cheeks, the shape and relative size of the tail and the ear. Some authors, such as Danilov et al. (2007) believe that due to the large variations in morphological characteristics between the two species and their frequent overlap, their identification in nature is almost impossible, although their work emphasizes the characteristic morphological features used as species diagnostics. During our numerous observations, we have not found any individuals with morphological characteristics of the North American beaver, i.e., with a strong reddish tinge of their fur (especially on the back above the tail), with contrasting light-coloured cheeks, a relatively short and rounded tail, which in its last third has gradually narrowing outer edges, and nostrils forming a trapezoidal opening, while in the Eurasian beaver the shape is triangular. In practice, there are indeed very few opportunities for precise assessment of all characteristic features, given the need for continuous observation from short distance and in good lighting conditions. However, based on data from genetic studies in Bulgaria’s neighbouring countries and reintroduction programs in the Danube River basin, which involve only Eurasian beavers, the likelihood of the appearance and, even more so, the massive expansion and colonization of North American beavers is illogical. Therefore, the possibility of the appearance and, even more so, the massive expansion and colonization of North American beavers is illogical, impossible and unnecessary to subject to scientific commentary.

In areas where the Eurasian beaver is known to live, there are four other amphibious mammals that can be mistaken for it. The water vole (Arvicola amphibius (Linnaeus, 1758) is a common inhabitant of all water bodies where beavers are found, but the likelihood of confusion is almost zero due to the visible differences in body size. Even new-born beavers are three times larger, so there is no need to specify other differences. The difference in body size between beavers and muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus (Linnaeus, 1766) is similar. An adult of this invasive North American species is about the size of a one-month-old beaver, recently emerged from its underground burrow. The other main differences for identification are the mandatory presence of the large female beaver, which is always in the front position, and the shape of the tail when the animals are on shore. When observing swimming individuals, the body position of the small beaver and the muskrat are very similar, with the entire back visible, but a distinctive feature is the tail, which is visible when the muskrat is swimming and has a snake-like shape and a well-defined keel on top. The footprints are also easily distinguishable. In beavers, they are five-toed, and the hind feet are very long with well-developed webbing between them. In muskrats, four toes are visible on the front feet, and the hind feet are not webbed. When observing an animal feeding in the water, the fur on the muzzle under the nose of the muskrat is contrasting light in colour, while that of the beaver is the same shade as on its head. In our research, we have encountered both species in the same water bodies only on the banks of the Danube islands during the summer-autumn low water period. During the other seasons, muskrats inhabit the Danube marshes and floodplains, while beavers stick to the banks of rivers.

The otter (Lutra lutra (Linnaeus, 1758) is a frequent companion of the beaver in Bulgaria. The main differences in identifying them on the shore are their body proportions, mainly the head to torso ratio and the shape of the tail. The otter’s head is relatively small. When observed in water, the swimming beaver usually submerges its entire body behind its shoulders, while the otter shows only its small head. The otter’s footprints are trapezoidal and web-toed on both pairs of limbs, and the thin, pointed claws usually do not leave marks. There is no significant difference in size between the two pairs of footprints, as is observed in beavers. The claw prints are also different when the animal has used them to climb out of a steep bank. In beavers, they are massive and always imprinted, even when the track is on a hard substrate.

Of all amphibious mammals coexisting with the beaver in Bulgaria, only distinguishing it from the nutria (Myocastor coypus (Molina, 1782) requires practical experience, and in some cases identification is impossible. Visually, the most significant and easy-to-apply morphological feature is the shape of the tail. It is relatively easy to recognize the animal with good visual contact with the features of the head. The nutria has an elongated muzzle, and the eye is located twice as far from its front edge as from the base of the ear. The nose is covered with white downy hair, and the whiskers are particularly long and also white. The cheeks are distinctly light-coloured and contrasting. In beavers, the muzzle is relatively short, and the eye is located halfway between the tip of the upper lip and the base of the ear. The nose is black and hairy, and the whiskers are also black. The nostrils of the nutria are oval-elliptical in shape, while those of the beaver are always sharply angled at the front. However, it is particularly difficult to recognize an animal swimming in the distance in low light conditions. When swimming, the head and pelvic area of the nutria are usually visible, and less often the entire back, while in adult beavers, the whole rear part is usually submerged under water. With careful observation and good visibility, one can see the movement and shape of the tail, which give the body a different thrust. In cases of recordings made with a phone camera, which we often receive from citizens, the recognition rate is approximately 50%. In these cases, it is necessary to collect additional data on traces of activity, such as gnawed branches and trunks or footprints. In nutria, the hind feet have a common webbing between the four toes, and the fifth toe is counter-positioned and free. In many cases, when we find traces of movement of both species in the same places, there are also traces of the tail dragging, as well as nutria faeces.

During our field observations and transects along river banks, we recorded, documented, and mapped all data on traces found or animals observed, which provide information on accompanying species and potential predators. In the experimental studies of the beaver, we tested methods for recording locations and counting family groups, which included volunteers who were trained beforehand to recognize the traces of the species’ activities. Our meetings with local fishermen, hunters, and residents who have daily or frequent contact with coastal habitats and, respectively, with beavers, proved to be extremely useful and informative. In almost all places, the beaver was unknown as a species, despite the visible characteristic gnaw marks on tree trunks and repeated observations of “huge otters with square heads and flat backs”. The gnaw marks were thought to be the result of “poaching”, and the animals were thought to be huge, well-fed otters, lying in wait to “steal” from fishing nets, which they “relishing” destroy. All the locals who knew about the presence of the beaver and could distinguish it from the otter and the nutria, mainly by the shape of its tail, had come across an animal drowned in fishing nets or a carcass washed up on the shore.

Our attempts to use a drone for the rivers in the Danube catchment proved infeasible and futile given the peculiarities of the beavers’ riverine ecological form. The experiments we conducted in the early stages of our research proved unsuccessful, given the fact that this ecological form lives under the thick canopy of tall and dense riparian vegetation and inhabits underground burrows. In addition to the above arguments for the impossibility of applying remote methods, the following considerations are also of great importance: the Danube is a border river and the use of aircraft is subject to a permit regime; the presence of a nuclear power plant makes the problems with issuing permits even greater; most river banks are steep and heavily sloped, which further reduces visibility, and in spring, when the vegetation is still bare, the rivers are in full flow and the beavers’ habitats are flooded, which is also a visual obstacle; last, but not least, the islands and banks are also habitats for many protected species, the disturbance of which is unnecessary and unacceptable.

3.3. Indirect Records of Eurasian beavers Based on Traces of Their Activities

The traces left by beavers when feeding, by gnawing trees and branches in a specific way, are the main way to prove the presence of the species and analyse the characteristics of the feeding individual(s). Regardless of seasonal differences in the species’ diet, gnawed branches are a daily, mandatory element in its existence and, respectively, in proving its presence. During the spring and summer months, when vegetation is actively growing and the river is abundant with macrophytes, feeding on woody vegetation is minimized or greatly reduced. However, regardless of the rich alternative menu, gnawed stems and branches dragged into the river, mainly from willow and poplar trees, can always be found in the active beaver’s habitats. Such were found during all our visits, although during the summer months in some locations this required a lot of time (for passing through).

Inspecting river sections around road bridges during the summer months, when riverbanks are heavily overgrown, difficult to traverse and visibility is reduced, proved to be extremely useful and effective. In three-quarters of our inspections, when the river section was occupied by beavers, there were gnawed branches stuck around the bridge. They are easily recognizable and visible, and this method proves to be extremely useful and effective. Beaver gnaw marks, in addition to being evidence of presence, are also an important source of information about the size and age composition of the family group and, respectively, about the presence of reproduction, as well as the potential number of individuals in the family, which is proven by the differences in the size of the incisor prints.

There are three recognizable size-age groups registered by the incisor size, which we also used in our experimental quantitative reports on the species: zero-year-olds, one-year-olds, and adults. The gnawed branches during the autumn period, starting in mid-September, are used to build food stores, which we found on all the large, medium, and small rivers studied. Each store found was measured, documented, and recorded in the field notebook for subsequent analysis. We did not find any winter food stores on the banks of the Danube and its islands, which may be due to three factors. The woody food resources in these habitats are inexhaustible and in close proximity to the inhabited dens, which does not necessitate the creation of food stores. The climate changes felt over the last two decades have caused some big changes in the Danube’s water regime, river flow, and lack of long cold periods during the winter months, which might have led to changes in how beavers act in these types of habitats. It is very likely that the period in which we have studied the Danube and its islands does not coincide with the period of food storage construction, and that the spring floods carry away the remains of the accumulated branches, which is why they remain unnoticed. This issue requires further clarification through visits to active family groups in late autumn and winter, given the lack of scientific information about similar studies on the Danube.

During our research on large, medium, and small rivers, we often came across gnawed branches placed perpendicular to the riverbank, which represented marking elements of the family group. The camera traps we set up have documented individuals marking the length of the branch with their castoreum. The piles of gnawed branches or of mud or clay mixed with chewed-up twigs and leaves, which are usually used to mark the territory occupied by the family group, are of a similar nature. Similar marking elements have also been mentioned by a number of authors who have studied the ecology of the beaver (Ognev 1947, Barabash-Nikiforov 1950, Lavrov 1961, Dyakov 1975, etc.).

In its continuous movements within its occupied family territory, the beaver forms characteristic exits, feeding areas, beaver trails to the feeding sites, and trenches along the muddy riverbanks, which we used not only as life activity traces for recording but also as elements for quantitative reporting, which are highly dependent on the number of individuals in the family group. These traces and their quantitative representation are the basis of two of the quantitative methods tested in our studies – the ecological-statistical method of Poyarkov (1953), and that of Lavrov (1961), for visual assessment of “total family power”. These are relatively laborious, but with the modifications applied by Kondratov et al. (2017) and the rational improvements we made, they proved to be extremely useful for refining the number of individuals in the respective family group.

Another characteristic feature for indirect identification of the species and individual is the footprint of the hind limb, which is often impossible to determine or the information cannot be used to determine the size-age group. During the summer months, when rivers are at their lowest and the banks are dry, footprints were completely absent or very faint, making it impossible to use them for both registration and determining the size and age group of the individual. It was also impossible to use tracks on dry sandy banks, as well as to observe them in close proximity to the shore where the water washes them away. During our studies at the Danube and its islands during periods of low water in 2022, 2023, and 2024, we observed well-defined tracks left on the sandbars by the wide and heavy tail, the width of which was measured and used as a marker to determine the size-age class of the respective individual.

Research into the territory inhabited by the family group necessarily included establishing the feeding epicenter, which we considered to be the place with the highest concentration of food remains and gnaw marks. A number of literary sources (Ognev 1947, Barabash-Nikiforov 1950, Lavrov 1961, Dyakov 1975, Dezhkin et al. 1986, Rosell and Campbell-Palmer 2022) show the main den of the beaver family is located near the feeding epicenter. In all sites in Bulgaria we have identified the riverine ecological form of the Eurasian beaver, in which the family group inhabits an underground burrow with an underwater entrance-exit, a living chamber in the steep bank, and a “chimney vent” at the top. In the northern latitudes, where there are extensive standing and slow-flowing water bodies formed by the floodplains of the large rivers, and in the absence of steep river banks, the lake form of the beaver is found. It lives in huts – floating islands with an underwater opening and a living chamber built in the middle. The dens of the river form, being built underground and having an underwater opening are difficult to locate. During the summer, we often came across lodges whose openings were revealed after the river waters receded. These were also the appropriate periods for exploration. In 2022, we were able to gather particularly valuable information about the structure of the dens on the banks of the Danube and its islands where during low waters the loess banks had collapsed and the living chambers were exposed. The presence of dens with several connected living chambers can be successfully used as information for dating the time of the family group’s subsistence in this territory (Barabash-Nikiforov 1950, Lavrov 1961, Dyakov 1975). The more chambers there are, the longer the period of use of the den, with some dens with 4–5 chambers being used for at least 5–6 years.

3.4. Experimented and Tested Ways to Count Family Groups and Individuals. Finding the Feeding Epicentre and Boundaries of the Family Territory

In all quantitative studies on the Eurasian beaver, the family group is the basis of the research, given the monogamous sex structure of the species. Regardless of the method used, the first important element of quantitative reporting is determining the number of family groups in the study area. The beaver is a highly territorial species, and each family group has a strict and defended family territory with clearly defined boundaries. The size of the territory varies greatly and is highly dependent on the trophic capacity, food availability and location of the feeding complex (includes all food habitats in the family territory – trees or also grasses, algae, reeds, papyrus, etc.) in the specific habitat (Dyakov 1975). We found that the boundaries of the occupied family territories ranged from 2–3 to 5–7 km for small and medium-sized rivers, about 1–2 km for large rivers, and between 200–300 to 400–600 m for the Danube and its islands. Similar distances have been recorded by Dyakov (1975) and Rosell and Campbell-Palmer (2022). In our field studies, we first sought to establish the feeding epicentre and then the outer boundaries of the actively occupied family territory. We considered only territories with traces of life activity at the time of the study to be active. We noted old traces and abandoned territories in the field diary, as well as territories where we found no signs of habitation. When we came across old gnaw marks in abandoned territories, we documented all traces for subsequent analysis of the probable reasons for the absence of living individuals.

During our research on the distribution of the Eurasian beaver and the development of methodologies for quantitative reporting, we gathered a collection of gnawed and nibbled branches, from which we documented the methods for laboratory measurement of incisor marks, and we experimented with determining the birth period of the young based on the size of their incisors. From each established beaver family group, we took a series of documentary photographs of all identified traces of life, which we used to create a database of photographic documents used in the development of quantitative reporting methods and in the training of volunteers. When observing family groups, we took into account the age classes of individuals according to Dyakov’s methodology (1975), which divides them into zero-year-olds, one-year-olds and adults. As the main criteria for determining the relevant class based on external morphological characteristics, we used the abundant information collected, systematised, and analysed by Lavrov (1981), Dyakov (1975), Borodina (1970), and we performed a comparative visual assessment based on the established morphological features and traces –size and proportions of the body, incisor marks, hind footprint or width of the trail from dragging the tail. When observing individuals from a family group, it is easy to assess their relative size and, accordingly, the size-age class. Zero-year-olds are usually close to their parents and their body size is three to four times smaller than that of their parents. One-year-olds are significantly larger and exceed half the body size of their parents. In Bulgaria, we very often found one-year-olds in the border areas of the family group or alone in peripheral and inter-family territories. Such data are available for other parts of the range where the species has a low concentration and is in a process of active expansion and colonization (Zharkov 1960, Borodina 1970). Similar results of self-dispersal of individuals less than one year old, even during the spring flood season of medium and small rivers, have been observed during reintroduction processes by Borodina (1966), Safonov (1966), Dyakov (1975), Dezhkin et al. (1986) and Balodis (1990).

3.5. Quantitative Reports on Family Groups and Determining Their Numbers

After establishing the feeding epicentre and territorial boundaries of the family group, the second step is to determine the number of individuals and their age. In all family groups we have studied, there were a maximum of three age groups: zero-year-olds, one-year-olds, and their mature parents. We found no groups in which two-year-old individuals remained in the family, as is often the case in places where beavers have settled long ago and have a relatively high density, resulting in a shortage of available habitats. Similar studies on the species have been conducted by many authors, who report a correlation between the density of the species in a given habitat and the presence of remained in the family two-year-old individuals, which do not differ in body size from their parents (Borodina 1970, Dyakov 1975, Balodis 1990). For the purposes of our research, we used the number of members in the third size-age group as criteria for the absence of two-year-old individuals, i.e., when two individuals were recorded in the size class of sexually mature individuals, we considered them to be the breeding couple. According to the morpho-ecological method (Dyakov 1975), we experimentally counted the number of size classes, mainly based on the shape and size of the incisor marks and, less frequently, on the size of the footprints and the width of the tail. In cases where we found zero-year-olds but the size class of the parents was missing, which happens very often during the summer periods, we assumed that the parents were present, because otherwise the current generation would not have survived.

When we covered large areas of several tens of kilometres per day during the summer months and had no experience in visually determining size classes, we took cuttings from gnawed branches of different size classes from each feeding epicentre we found, which we subjected to precise laboratory measurements to determine the number of individuals. In combination with the morpho-ecological method, we also used the statistical method, which is based on the average number of individuals in family groups in a relatively large area. In this way, we calculated the total population of the species in Bulgaria. The modification of this method, made by Kondratov et al. 2017 (see

Table 5), is based on calculating the correction coefficient not by a complete counting of a large number of family groups, which is extremely laborious and expensive, but by the number and percentage of breeding families relative to the total number of registered families. In our experimental studies of beaver family groups, the registration of zero-year-old individuals (when present) was always available, so we believe that there are no missing records for this size class. From Lavrov’s method (1961), we tested the determination of the number of individuals (two or one) in cases where we determine only one size class, which is considered one of the shortcomings of the morpho-ecological method.

To check the accuracy of the counting of the number of individuals in a family group using the methods described above – statistical, morpho-ecological, ecological-statistical, and of the total family power of Lavrov, we performed verification in two ways – through direct observation of a family group with cameras and by measuring all gnaw marks within the area of the family group. All gnaw marks are recorded in calculation tables (see

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4), from which the number of individuals in the family group is then determined very accurately.

4. Conclusions

The scheme we used is a combination of all four basic methods used in the research on the Eurasian beaver, depending on the specific situation and the possibility of collecting biological information through citizen science and applying biological extrapolation. The scientific strategies in the field of citizen science, tested to establish the distribution of the Eurasian beaver in Bulgaria through methods of promotion among a wide range of local people and organizations, proved to be free, easy to implement and extremely successful.

The experimental riverine habitats used as models for recording and quantifying family groups and individuals convinced us that the appropriate study periods for large, medium-sized, and small rivers are during the fall and winter, when the animals are most active, visibility is good due to the falling leaves and the opening of the coastal line, and individuals build food stores in preparation for the winter period. For the Danube and its islands, the appropriate and feasible period for study is during the summer-autumn low waters, when traces of all life activities are easily visible and habitats are accessible.

The registration of the species (its presence) and the determination of the number of individuals in family groups is carried out simultaneously and in order to refine the accuracy of the report, it is necessary to collect all available information for each family group, which we determine based on the predefined boundaries of the family territory and subsequent verification of the data by applying a combination of direct and indirect methods.

The only way to study beaver’ riverine ecological form, which inhabits underground burrows, is by directly walking along the riverbank or riverbed, and when the territories are large, biological extrapolation is permissible and necessary. Research using aircraft (drones, planes and helicopters) is not applicable to this ecological form, which lives under the thick canopy of tall and dense riparian vegetation and inhabits underground burrows.

The experimental approaches used to study the Eurasian beaver provide a good basis for developing a national program and strategy for studying the distribution and abundance of the beaver, as well as for predicting the overall recovery of the species after its complete destruction in the recent past.

It is now imperative and urgent, after the four-year period since the first substantiated proposal for the protection of the species was made by the authors in October 2021, the competent nature conservation authorities to take the decision and include the autochthonous in Bulgaria Eurasian beaver in Annexes 2 and 3 of the Biodiversity Act, referring to the commitments made with the signing of the Habitats Directive, the border location of the Danube River with the Republic of Romania (where the species has been protected since 2007), and our membership in the EU, which will ensure not only the protection of the species but also the necessary funds for research, monitoring, and payment of compensation where necessary.