Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Field Experiments

2.2. Determination of Phenotypic Characteristics and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

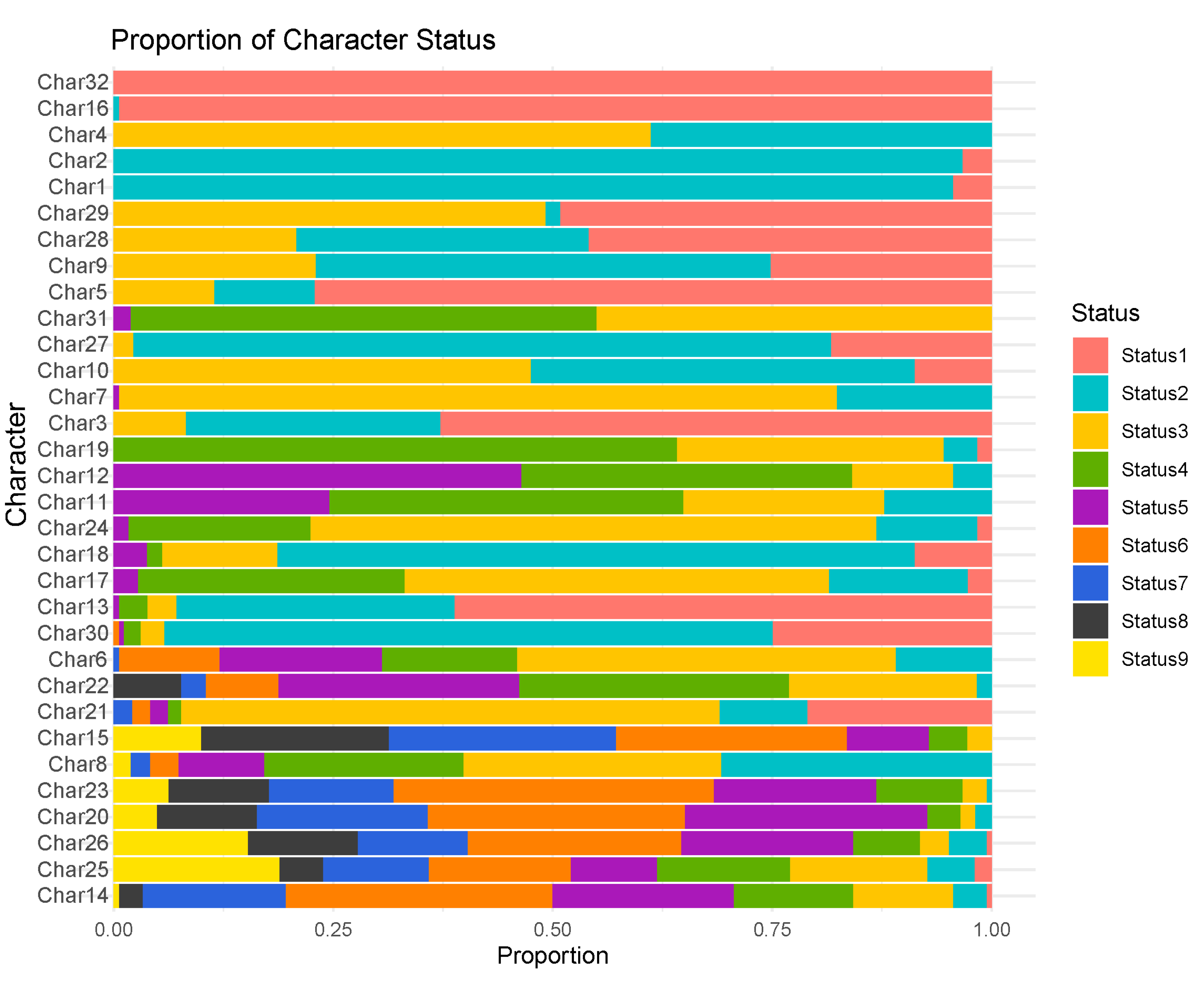

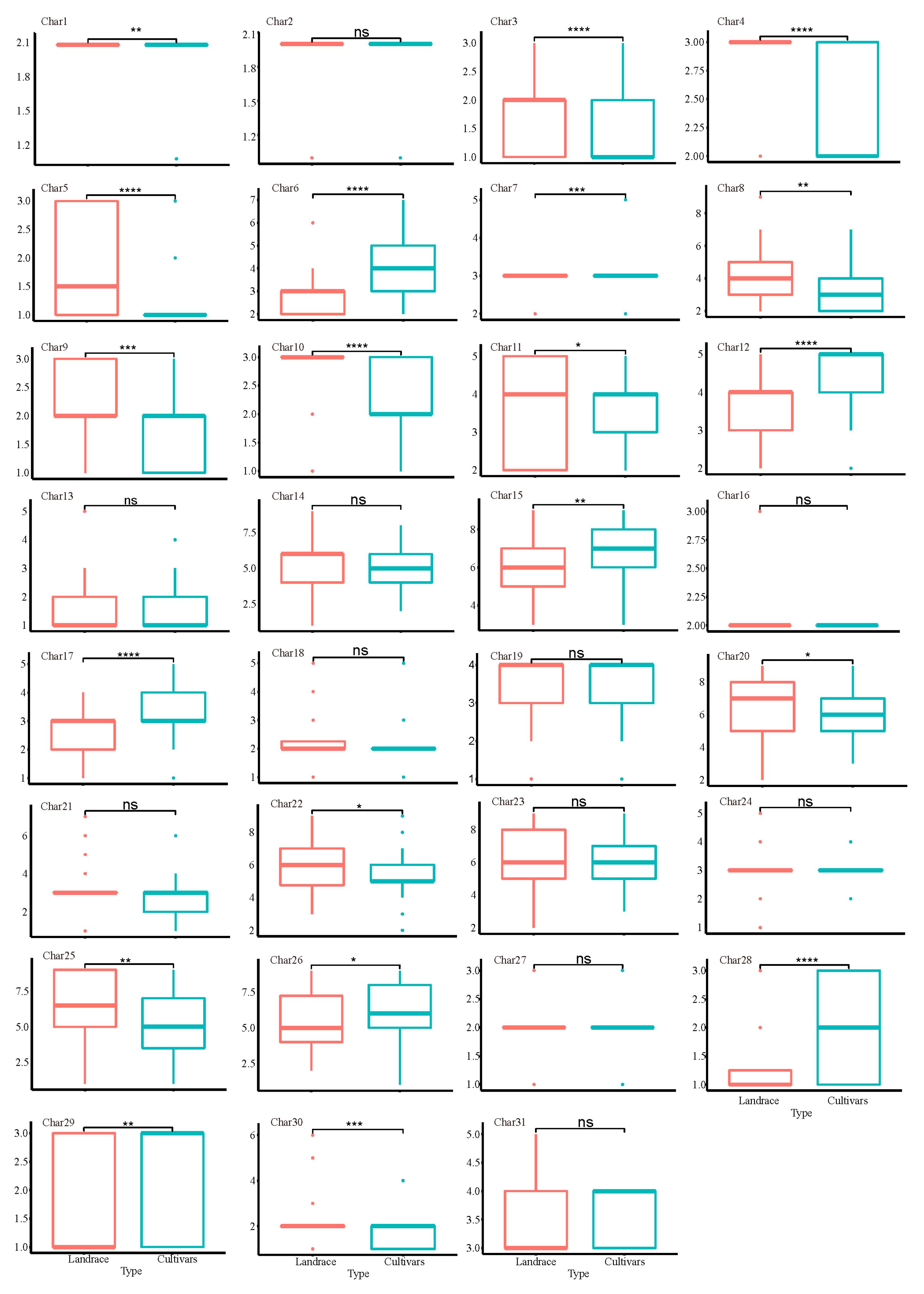

3.1. Observation and Analysis of DUS Testing Characteristics

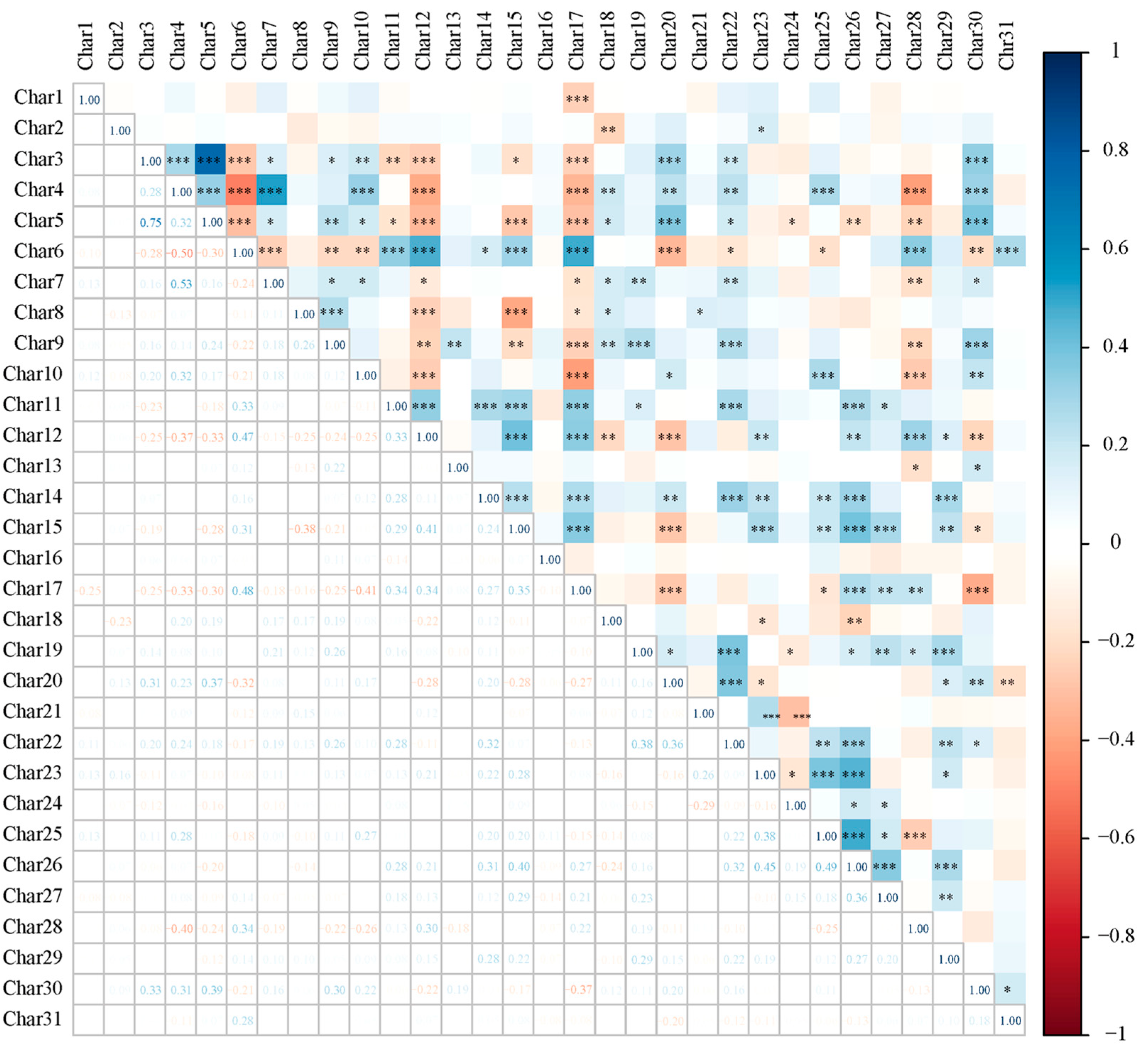

3.2. Correlation of Phenotypic Characteristics

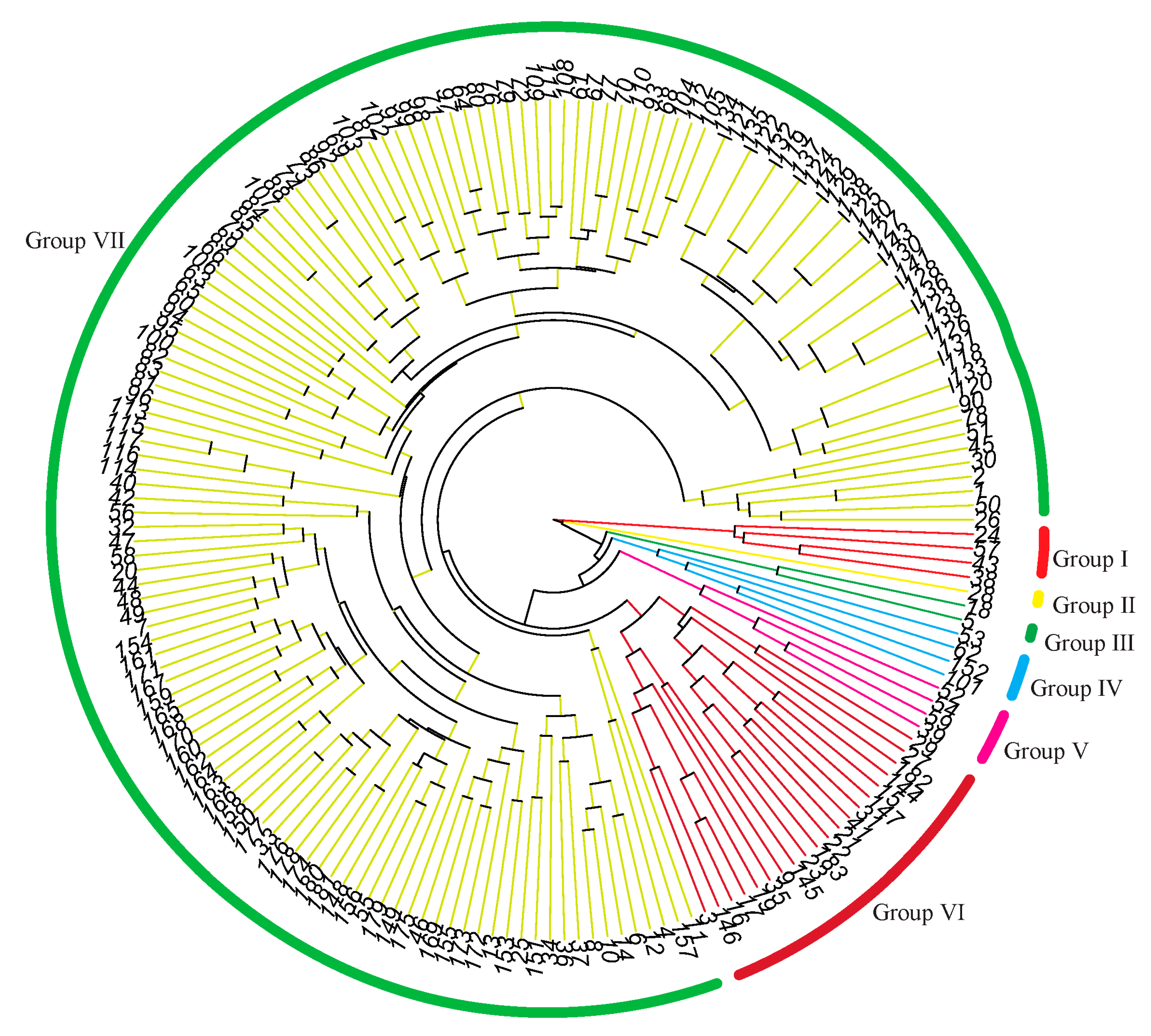

3.3. Cluster Analysis

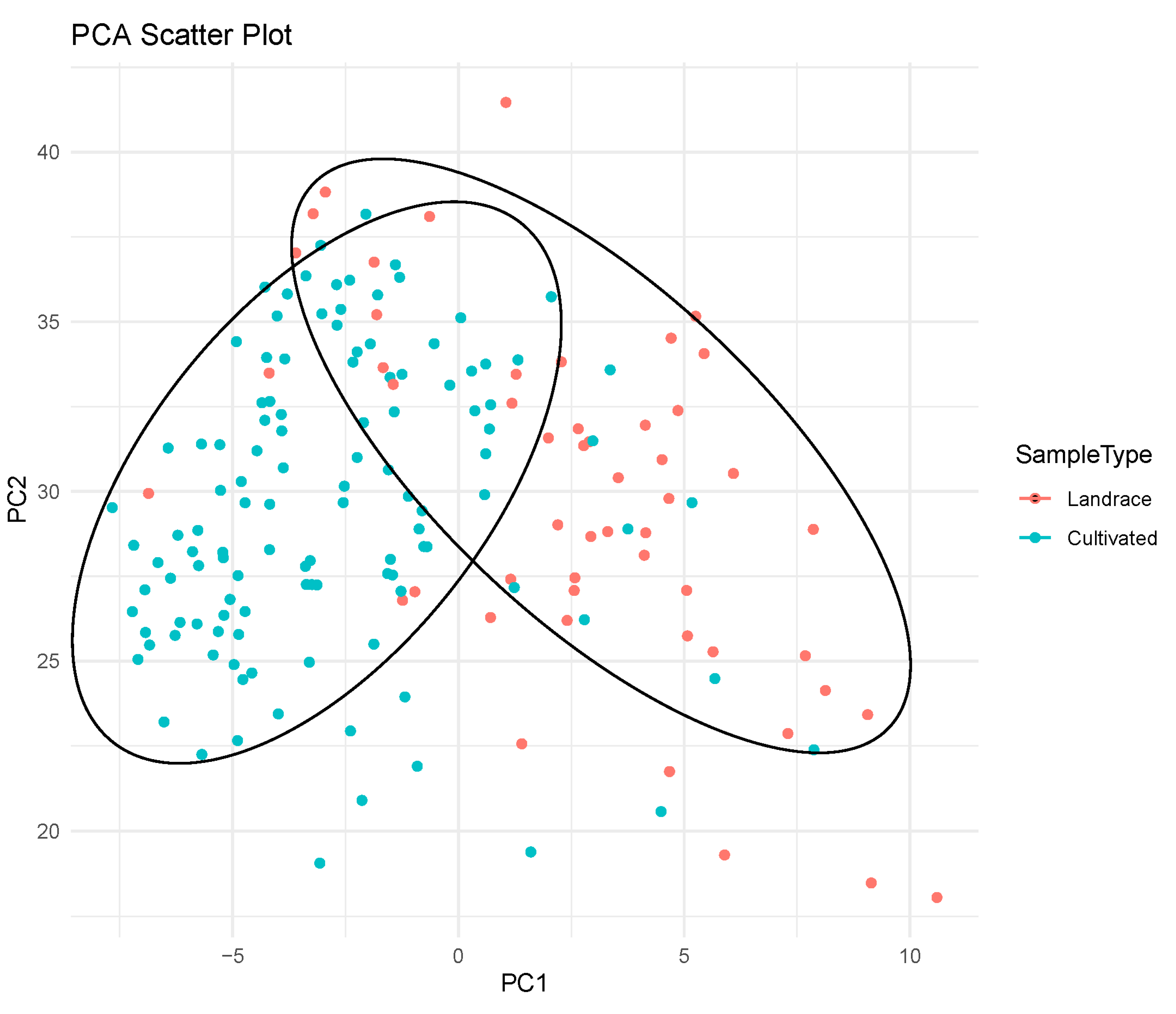

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.5. Analysis of Breeding Trends

3.6. Comprehensive Evaluation Using TOPSIS Algorithm

4. Discussion

4.1. Phenotypic Variation of Foxtail Millet Resources

4.2. Correlation Analysis and PCA

4.3. Analysis of Breeding Trends and Screening of Potential Varietal Resources

5. Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Austin, D.F. Foxtail millets (Setaria: Poaceae)—abandoned food in two hemispheres. Econ. Bot 2006, 60, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolai, I.V. On the Origin of Cultivated Plants. 2014, 0, 0–0.

- Duc, Q.N.; Joyce, V.E.; Andrew, L.E.; Christopher, P.L.G. Robust and Reproducible Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation System of the C4 Genetic Model Species Setaria viridis. Front. Plant Sci 2020, 11, 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Sangam, L.; Hari, D.; Upadhyaya, S.; Senthilvel, C.T.; Kenji, F.; Xianmin, D. , Dipak, K., Santra, D., Baltensperge, M.P. Millets: Genetic and Genomic Resources. Plant Breed. Rev 2011, 0, 247–375. [Google Scholar]

- Carla, P.C.; Pu, H.; Thomas, P.B. Setaria viridis as a Model for C4 Photosynthesis. Plant Genet. Genomics Crops Models 2011, 0, 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, N.D.; Elizabeth, A.K.; Katrien, M.D.; Jeffrey, L.B. Foxtail Millet: A Sequence-Driven Grass Model System. Plant Physiol 2009, 149, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhi, H.; Yang, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, B.; Chen, M.; Diao, X.M. Population genetics of foxtail millet and its wild ancestor. BMC Genom. Data 2010, 11, 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.Y.; He, Q.; Lv, M.J.; Shi, T.; Gao, Q.; Zhi, H.; Wang, H.; Jia, G.Q.; Tang, S.; Cheng, X.L.; Wang, R.; Xu, A.D.; Wang, H.G.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Diao, X.M.; Gao, Y. Integrated genomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals genes associated with plant height of foxtail millet. Crop J 2023, 11, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuraloviya, M.; Vanniarajan, C.; Sudhagar, R.; Vetriventhan, M. Phenotypic diversity and stability of early maturing Barnyard Millet (Echinochloa sp.) germplasm for grain yield and its contributing traits. Indian J. Exp. Biol 2022, 60, 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, B.L.; Liu, L.Y.; Zhang, L.X.; Song, S.B.; Wang, J.G.; Wu, L.Y.; Li, H.J. Characterization of culm morphology, anatomy and chemical composition of foxtail millet cultivars differing in lodging resistance. J. Agric. Sci 2015, 153, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.B.; Yuan, Y.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Song, H.; Yang, Q.Y.; Yang, P.; Gao, X.L.; Gao, J.F.; Feng, B.L. Conuping BSA-Seq and RNA-Seq Reveal the Molecular Pathway and Genes Associated with the Plant Height of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). Int. J. Mol. Sci 2022, 23, 11824–11824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, K.A.; Kudakwashe, H.; Johanna, S.V.; Helena, N.N.; Evans, K.S.; Barthlomew, Y.C.; Lydia, N.H.; Simon, A.; Akundabweni, L.S.M.; Osmund, M. Co-Cultivation and Matching of Early- and Late-Maturing Pearl Millet Varieties to Sowing Windows Can Enhance Climate-Change Adaptation in Semi-Arid Sub-Saharan Agroecosystems. Climate 2022, 11, 227–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sreeja, R.; Balaji, S.; Arul, L.; Kumari, A.; Kannan, B.; Subramanian, A. Association of lignin and FLEXIBLE CULM 1 (FC1) ortholog in imparting culm strength and lodging resistance in kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum L.). Mol. Breed 2016, 36, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Mi, J.X.; Li, F.C.; Liang, M.S. An improved TOPSIS method for multi-criteria decision making based on hesitant fuzzy β neighborhood. AI Rev 56, 793–831. [CrossRef]

- Abootalebi, S.; Hadi-Vencheh, A.; Jamshidi, S. Ranking the Alternatives With a Modified TOPSIS Method in Multiple Attribute Decision Making Problems. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 2022, 69, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubna, L.; Mohammed, C.A.; Mohammed, T.A. New distributed-topsis approach for multi-criteria decision-making problems in a big data context. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, B.; Amin, G. Modeling land suitability evaluation for wheat production by parametric and TOPSIS approaches using GIS, northeast of Iran. Model. Earth Syst. Environ 2016, 2, 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Puja, P.N.; Anindita, D. An entropy-based TOPSIS approach for selecting best suitable rice husk for potential energy applications: pyrolysis kinetics and characterization of rice husk and rice husk ash. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2022, 0, 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, E.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, T.-J. Effects of humic acid on japonica rice production under different irrigation practices and a TOPSIS-based assessment on the Songnen Plain, China. Irrig. Sci 2021, 40, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.X.; Zheng, Q.; Luo, S.Y.; Xiang, T.; Zhou, L.J.; Feng, S.L.; Yang, H.C.; Ding, C.B. Characterization and comprehensive evaluation of phenotypic characters in wild Camellia oleifera germplasm for conservation and breeding. Front. Plant Sci 2023, 14, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Zheng, Y.; Duan, L.L.; Wang, M.M.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Li, R.Y.; Zhang, H. Artificial Selection Trend of Wheat Varieties Released in Huang-Huai-Hai Region in China Evaluated Using DUS Testing Characteristics. Front. Plant Sci 2020, 13, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Yao, Z.Y.; Ma, Q.; Liu, J.M.; Liu, Y.X.; Liang, W.; Zhang, T.; Yin, D.X.; Liu, W.; Qiao, Q. A study on the phenotypic diversity of Sinopodophyllum hexandrum (Royle) Ying. Pak. J. Bot 2022, 54, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.M.; Yang, L.; Gao, G.; Liao, D.S.; Li, L.; Qiu, J.; Wei, H.L.; Deng, Q.E.; Zhou, Y.C. A comparative study on the leaf anatomical structure of Camellia oleifera in a low-hot valley area in Guizhou Province, China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262509–e0262509. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, K.L.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.X.; Qiao, P.F.; Wang, J.X.; Shi, W.P.; Guo, J.; Diao, X.M. Efficient identification of QTL for agronomic traits in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) using RTM- and MLM-GWAS. Theor. Appl. Genet 2024, 137, 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.P.; Sam, F. Source-sink manipulations indicate seed yield in canola is limited by source availability. Eur. J. Agron 2018, 96, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, M.; Saisana, M.; Saltelli, A.; Tarantola, S. Tools for composite indicators building. Eur. Comission Ispra. 2005, 15, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc A 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, X.M. ; Production and genetic improvement of minor cereals in China. Crop J 2017, 5, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.X.; Guo, W.Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; He, Q.; Chen, W.Y.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.Z.; Dong, K.J.; Ren, R.Y.; Tian, y.; Zhang, L.Y.; Qi, M.Y.; Li, C.K.; Zhao, M.; Wang, H.G.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.Q.; Jiang, Y.M.; Liu, G.Q.; Song, X.Q.; Deng, Y.W.; Lv, H.; Yan, F.; Dong, Y.; Li, Q.Q.; Li, T.; Yang, W.; Cui, J.H.; Wang, H.R.; Zhou, Y.F.; Zhang, X.M.; Jia, G.Q.; Lü, P.; Zhi, H.; Tang, S.; Diao, X.M. Pangenome analysis reveals genomic variations associated with domestication traits in broomcorn millet. Nat. Genet 2023, 55, 2243–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kei, S.; Yohei, M.; Kunihiko, Naito.; Kenji, F. Construction of a foxtail millet linkage map and mapping of spikelet-tipped bristles 1(stb1) by using transposon display markers and simple sequence repeat markers with genome sequence information. Mol. Breeding 2013, 31, 675–684. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.Y.; Zhang, L.; Cui, L.; Guo, E.H.; Zhao, P.Y.; Xu, Z.S.; Li, Q.; Guo, S.S.; Wu, Y.J.; Li, Z. Identification of a QTL for Setaria italica bristle length using QTL-seq. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol 2023, 0, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.C.; Tang, S.; Zhang, H.S.; He, M.; Liu, J.H.; Zhi, H.; Sui, Y.; Liu, X.T.; Jia, G.Q.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Yan, J.J.; Zhang, B.C.; Zhou, Y.H.; Chu, J.F.; Wang, X.C.; Zhao, B.; Tang, W.Q.; Li, J.Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Liu, X.G.; Diao, X.M. ; DROOPY LEAF1 controls leaf architecture by orchestrating early brassinosteroid signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2022, 117, 21766–21774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Character code | Type of expression | Method of observation | States and code of expression |

| First leaf: shape of tip | char1 | PQ | VG | pointed(1)pointed to rounded(2)rounded(3) |

| Seedling: Leaf color | char2 | PQ | VG | yellow green(1)green(2)light purple(3)purple(4) |

| Seedling: Leaf sheath color | char3 | PQ | VG | green(1)light purple(2)medium purple(3) |

| Seeding: growth habit | char4 | PQ | VG | upright(1)semi-upright(2)spreading(3)drooping(4) |

| Seedling: Anthocyanin shows color in leaf midrib | char5 | QN | VG | absent or weak(1)medium(2)strong(3) |

| Time of heading | char6 | QN | MG | very early(1)early(3)medium(5)late(7)very late(9) |

| Plant: growth habit | char7 | PQ | VG | upright(1)semi-upright(2)spreading(3)drooping(4) |

| Panicle: length of bristles | char8 | QN | VG | short(3)medium(5)long(7) |

| Panicle: bristles color | char9 | PQ | VG | green(1)yellow(2)purple(3) |

| Anther: color | char10 | PQ | VG | white(1)yellow(2)brown(3) |

| Flag leaf: length of blade | char11 | QN | MS/MG | short(1)medium(3)long(5) |

| Flag leaf: width of blade | char12 | QN | MS/MG | narrow(1)medium(3)broad(5) |

| Panicle: color of glume | char13 | PQ | VG | yellow green(1)green(2)red(3)light purple(4)medium purple(5) |

| Stem: length | char14 | QN | MS/MG | very short(1)short(3)medium(5)long(7)very long(9) |

| Stem: diameter | char15 | QN | MS/MG | narrow(3)medium(5)broad(7) |

| plant:color | char16 | PQ | VG | yellow(1)green(2)light purple(3)medium purple(4) |

| Plant: number of elongated internodes | char17 | QN | MG | few(1)medium(3)many(5) |

| Plant: number of culms per panicle | char18 | QN | MS | few(1)medium(3)many(5) |

| Panicle neck: attitude | char19 | PQ | VG | straight(1)medium curve(2)strong curve(3)claw(4) |

| Panicle neck:length | char20 | QN | MS | short(3)medium(5)long(7) |

| Panicle: type | char21 | PQ | VG | conical(1)spindle(2)cylindrical(3)club(4)duck mouth(5)cat foot(6)branched(7) |

| Panicle: length | char22 | QN | MG | very short(1)short(3)medium(5)long(7)very long(9) |

| Panicle:diameter | char23 | QN | MS | narrow(3)medium(5)broad(7) |

| Panicle:density | char24 | QN | VG | lax(1)lax to medium(2)medium(3)medium to dense(4)dense(5) |

| Panicle: single-grain number | char25 | QN | MG | very few(1)few(3)medium(5)many(7)very many(9) |

| Panicle: single panicle weight | char26 | QN | MS | very low(1)low(3)medium(5)high(7)very high(9) |

| Panicle: Grain yield per panicle | char27 | QN | MS | low(1)medium(2)high(3) |

| 1000 grain weight | char28 | QN | MG | low(1)medium(2)high(3) |

| Grain: shape | char29 | PQ | VG | narrow ovate(1)medium ovate(2)circular(3) |

| Grain: color | char30 | PQ | VG | white(1)yellow(2)red(3)brown(4)grey(5)black(6) |

| Dehusked grain:color (not polished) | char31 | PQ | VG | white(1)grey green(2)light yellow(3)medium yellow(4)grey(5) |

| Endosperm: type | char32 | QL | VG | waxy(1)non-waxy(2) |

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | CV | Max | Min | H’ |

| char1 | 1.96 | 0.19 | 9.89 | 2 | 1 | 0.183 |

| char2 | 1.97 | 0.18 | 9.15 | 2 | 1 | 0.147 |

| char3 | 1.46 | 0.65 | 44.08 | 3 | 1 | 0.864 |

| char4 | 2.63 | 0.48 | 18.43 | 3 | 2 | 0.661 |

| char5 | 1.35 | 0.68 | 50.31 | 3 | 1 | 0.707 |

| char6 | 3.79 | 1.24 | 32.70 | 7 | 2 | 1.490 |

| char7 | 2.83 | 0.42 | 14.69 | 5 | 2 | 0.503 |

| char8 | 3.31 | 1.31 | 39.54 | 9 | 2 | 1.493 |

| char9 | 1.97 | 0.69 | 35.21 | 3 | 1 | 1.218 |

| char10 | 2.40 | 0.65 | 26.98 | 3 | 1 | 1.129 |

| char11 | 3.78 | 0.96 | 25.43 | 5 | 2 | 1.489 |

| char12 | 4.25 | 0.83 | 19.55 | 5 | 2 | 1.228 |

| char13 | 1.51 | 0.76 | 50.52 | 5 | 1 | 1.045 |

| char14 | 5.22 | 1.51 | 29.02 | 9 | 1 | 1.790 |

| char15 | 6.78 | 1.34 | 19.79 | 9 | 3 | 1.705 |

| char16 | 2.01 | 0.07 | 3.72 | 3 | 2 | 1.078 |

| char17 | 3.15 | 0.82 | 26.06 | 5 | 1 | 1.431 |

| char18 | 2.19 | 0.78 | 35.39 | 5 | 1 | 1.156 |

| char19 | 3.56 | 0.65 | 18.28 | 4 | 1 | 1.100 |

| char20 | 6.14 | 1.36 | 22.23 | 9 | 2 | 1.709 |

| char21 | 2.69 | 1.10 | 40.59 | 7 | 1 | 1.256 |

| char22 | 5.37 | 1.21 | 22.51 | 9 | 2 | 1.579 |

| char23 | 6.06 | 1.44 | 23.80 | 9 | 2 | 1.737 |

| char24 | 3.10 | 0.68 | 21.84 | 5 | 1 | 1.379 |

| char25 | 5.66 | 2.29 | 40.45 | 9 | 1 | 2.032 |

| char26 | 6.20 | 1.91 | 30.84 | 9 | 1 | 1.949 |

| char27 | 1.84 | 0.42 | 23.11 | 3 | 1 | 0.58 |

| char28 | 1.74 | 0.77 | 44.35 | 3 | 1 | 1.045 |

| char29 | 1.98 | 0.99 | 50.13 | 3 | 1 | 0.766 |

| char30 | 1.83 | 0.66 | 36.25 | 6 | 1 | 0.812 |

| char31 | 3.55 | 0.52 | 14.65 | 5 | 3 | 0.745 |

| char32 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2 | 2 | 0.000 |

| characters | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Char1 | 0.134 | 0.097 | -0.243 | -0.060 | -0.114 | 0.088 | -0.286 | 0.181 | 0.535 | 0.110 | -0.054 |

| Char2 | -0.036 | 0.124 | 0.023 | -0.143 | 0.507 | -0.140 | -0.055 | 0.271 | 0.200 | -0.372 | 0.145 |

| Char3 | 0.579 | 0.074 | 0.178 | 0.096 | 0.519 | -0.001 | 0.039 | -0.209 | -0.079 | 0.207 | -0.130 |

| Char4 | 0.620 | 0.335 | -0.209 | 0.074 | -0.127 | 0.036 | 0.214 | -0.331 | 0.116 | -0.206 | 0.140 |

| Char5 | 0.671 | -0.014 | 0.212 | 0.123 | 0.430 | 0.067 | 0.176 | -0.112 | -0.055 | 0.144 | -0.092 |

| Char6 | -0.686 | -0.021 | 0.349 | 0.160 | 0.054 | 0.337 | -0.040 | 0.041 | 0.054 | 0.104 | -0.045 |

| Char7 | 0.401 | 0.281 | 0.007 | -0.165 | -0.190 | 0.225 | 0.190 | -0.258 | 0.372 | -0.243 | 0.209 |

| Char8 | 0.244 | -0.080 | 0.291 | -0.338 | -0.570 | 0.017 | -0.093 | 0.123 | -0.243 | -0.069 | -0.084 |

| Char9 | 0.456 | 0.167 | 0.176 | -0.126 | -0.178 | 0.290 | 0.029 | 0.458 | -0.204 | 0.184 | 0.219 |

| Char10 | 0.449 | 0.211 | -0.189 | 0.137 | -0.129 | 0.204 | -0.220 | -0.115 | -0.029 | -0.003 | -0.335 |

| Char11 | -0.358 | 0.429 | 0.311 | 0.056 | -0.163 | 0.017 | 0.258 | 0.001 | 0.266 | -0.103 | 0.134 |

| Char12 | -0.665 | 0.203 | 0.051 | -0.142 | 0.184 | 0.160 | -0.070 | -0.054 | 0.123 | 0.075 | 0.067 |

| Char13 | 0.041 | 0.044 | -0.012 | 0.329 | 0.144 | 0.295 | 0.292 | 0.550 | -0.149 | -0.118 | 0.157 |

| Char14 | -0.090 | 0.556 | 0.276 | 0.150 | -0.030 | 0.021 | 0.217 | 0.110 | 0.031 | 0.194 | -0.491 |

| Char15 | -0.482 | 0.498 | -0.246 | 0.238 | 0.108 | 0.215 | 0.079 | -0.146 | 0.181 | 0.044 | 0.048 |

| Char16 | 0.121 | -0.035 | -0.216 | -0.111 | 0.095 | 0.151 | -0.066 | -0.016 | 0.086 | 0.665 | 0.302 |

| Char17 | -0.689 | 0.107 | 0.127 | 0.063 | 0.059 | -0.066 | 0.481 | -0.024 | -0.134 | 0.051 | 0.005 |

| Char18 | 0.258 | -0.118 | 0.305 | 0.205 | -0.421 | 0.195 | 0.360 | -0.102 | 0.186 | 0.179 | -0.096 |

| Char19 | 0.137 | 0.383 | 0.520 | -0.286 | 0.013 | -0.019 | -0.247 | -0.139 | -0.026 | 0.137 | 0.375 |

| Char20 | 0.488 | 0.150 | 0.321 | 0.163 | 0.125 | -0.499 | 0.002 | 0.133 | 0.120 | -0.042 | -0.160 |

| Char21 | 0.039 | 0.085 | -0.032 | -0.617 | 0.064 | 0.146 | 0.297 | -0.136 | -0.321 | -0.079 | -0.016 |

| Char22 | 0.298 | 0.578 | 0.305 | -0.089 | -0.036 | -0.225 | 0.038 | 0.149 | 0.164 | 0.101 | 0.055 |

| Char23 | -0.106 | 0.524 | -0.355 | -0.458 | 0.016 | 0.140 | 0.078 | 0.224 | -0.025 | -0.047 | -0.234 |

| Char24 | -0.109 | 0.017 | -0.091 | 0.543 | -0.335 | -0.209 | -0.191 | 0.167 | -0.036 | 0.046 | 0.162 |

| Char25 | 0.160 | 0.605 | -0.427 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.052 | -0.149 | -0.016 | -0.182 | 0.187 | -0.040 |

| Char26 | -0.247 | 0.749 | -0.162 | 0.056 | 0.008 | -0.224 | -0.055 | 0.062 | -0.194 | 0.007 | 0.063 |

| Char27 | -0.201 | 0.385 | 0.117 | 0.341 | -0.086 | -0.071 | -0.135 | -0.383 | -0.401 | -0.088 | 0.234 |

| Char28 | -0.430 | -0.142 | 0.416 | -0.273 | 0.098 | -0.103 | -0.226 | -0.058 | 0.122 | 0.117 | -0.037 |

| Char29 | -0.078 | 0.482 | 0.256 | -0.036 | -0.061 | 0.026 | -0.390 | 0.017 | -0.054 | -0.142 | -0.194 |

| Char30 | 0.518 | 0.099 | 0.150 | 0.202 | 0.188 | 0.277 | -0.122 | 0.173 | -0.057 | -0.180 | 0.206 |

| Char31 | -0.068 | -0.069 | 0.255 | 0.154 | 0.120 | 0.644 | -0.319 | -0.119 | -0.036 | -0.207 | -0.155 |

| variety num | score | rank | variety num | score | rank | variety num | score | rank |

| 144 | 0.0044019 | 1 | 47 | 0.0051848 | 62 | 75 | 0.0057543 | 123 |

| 164 | 0.0044072 | 2 | 18 | 0.0051848 | 63 | 80 | 0.0057656 | 124 |

| 169 | 0.0044475 | 3 | 58 | 0.0052139 | 64 | 9 | 0.0057692 | 125 |

| 163 | 0.0044789 | 4 | 160 | 0.0052141 | 65 | 180 | 0.0057746 | 126 |

| 178 | 0.0044814 | 5 | 109 | 0.0052163 | 66 | 28 | 0.0057757 | 127 |

| 136 | 0.0045208 | 6 | 147 | 0.0052227 | 67 | 123 | 0.0057808 | 128 |

| 23 | 0.0045217 | 7 | 82 | 0.0052237 | 68 | 12 | 0.0057846 | 129 |

| 24 | 0.0045440 | 8 | 63 | 0.0052340 | 69 | 97 | 0.0057949 | 130 |

| 130 | 0.0045671 | 9 | 79 | 0.0052358 | 70 | 99 | 0.0058321 | 131 |

| 161 | 0.0045847 | 10 | 64 | 0.0052430 | 71 | 153 | 0.0058577 | 132 |

| 2 | 0.0046025 | 11 | 33 | 0.0052437 | 72 | 13 | 0.0058617 | 133 |

| 137 | 0.0046308 | 12 | 166 | 0.0052499 | 73 | 110 | 0.0058849 | 134 |

| 168 | 0.0046707 | 13 | 10 | 0.0052500 | 74 | 98 | 0.0058937 | 135 |

| 129 | 0.0046859 | 14 | 31 | 0.0052550 | 75 | 172 | 0.0058989 | 136 |

| 73 | 0.0046881 | 15 | 158 | 0.0052550 | 76 | 39 | 0.0059003 | 137 |

| 106 | 0.0046898 | 16 | 142 | 0.0052580 | 77 | 182 | 0.0059397 | 138 |

| 4 | 0.0047016 | 17 | 135 | 0.0052580 | 78 | 72 | 0.0059493 | 139 |

| 133 | 0.0047340 | 18 | 60 | 0.0052635 | 79 | 59 | 0.0059500 | 140 |

| 175 | 0.0047354 | 19 | 19 | 0.0052735 | 80 | 29 | 0.0059534 | 141 |

| 167 | 0.0047465 | 20 | 132 | 0.0052810 | 81 | 68 | 0.0059650 | 142 |

| 138 | 0.0047536 | 21 | 173 | 0.0052846 | 82 | 35 | 0.0059703 | 143 |

| 113 | 0.0047543 | 22 | 8 | 0.0052868 | 83 | 49 | 0.0059762 | 144 |

| 5 | 0.0047684 | 23 | 126 | 0.0052929 | 84 | 124 | 0.0059786 | 145 |

| 177 | 0.0047778 | 24 | 52 | 0.0052994 | 85 | 89 | 0.0059938 | 146 |

| 1 | 0.0047928 | 25 | 17 | 0.0053017 | 86 | 102 | 0.0060098 | 147 |

| 131 | 0.0047944 | 26 | 65 | 0.0053155 | 87 | 122 | 0.0060135 | 148 |

| 61 | 0.0048162 | 27 | 88 | 0.0053402 | 88 | 85 | 0.0060177 | 149 |

| 174 | 0.0048341 | 28 | 127 | 0.0053587 | 89 | 30 | 0.0060186 | 150 |

| 171 | 0.0048344 | 29 | 118 | 0.0053686 | 90 | 48 | 0.0060246 | 151 |

| 159 | 0.0048400 | 30 | 146 | 0.0054040 | 91 | 93 | 0.0060310 | 152 |

| 162 | 0.0048416 | 31 | 62 | 0.0054062 | 92 | 108 | 0.0060672 | 153 |

| 145 | 0.0048555 | 32 | 96 | 0.0054110 | 93 | 46 | 0.0060870 | 154 |

| 128 | 0.0048679 | 33 | 56 | 0.0054122 | 94 | 40 | 0.0060899 | 155 |

| 157 | 0.0048728 | 34 | 7 | 0.0054256 | 95 | 91 | 0.0060950 | 156 |

| 22 | 0.0048753 | 35 | 16 | 0.0054256 | 96 | 27 | 0.0061222 | 157 |

| 134 | 0.0048994 | 36 | 57 | 0.0054285 | 97 | 151 | 0.0061299 | 158 |

| 179 | 0.0049497 | 37 | 120 | 0.0054855 | 98 | 37 | 0.0061510 | 159 |

| 156 | 0.0049500 | 38 | 84 | 0.0055166 | 99 | 104 | 0.0061545 | 160 |

| 77 | 0.0049523 | 39 | 155 | 0.0055502 | 100 | 140 | 0.0061572 | 161 |

| 11 | 0.0049550 | 40 | 141 | 0.0055515 | 101 | 181 | 0.0061625 | 162 |

| 6 | 0.0049585 | 41 | 76 | 0.0055526 | 102 | 36 | 0.0061794 | 163 |

| 15 | 0.0049806 | 42 | 41 | 0.0055599 | 103 | 38 | 0.0061982 | 164 |

| 71 | 0.0050105 | 43 | 83 | 0.0055611 | 104 | 107 | 0.0062144 | 165 |

| 66 | 0.0050126 | 44 | 183 | 0.0055832 | 105 | 149 | 0.0062277 | 166 |

| 165 | 0.0050212 | 45 | 152 | 0.0055913 | 106 | 44 | 0.0062539 | 167 |

| 114 | 0.0050214 | 46 | 125 | 0.0056023 | 107 | 90 | 0.0062543 | 168 |

| 143 | 0.0050331 | 47 | 139 | 0.0056143 | 108 | 34 | 0.0063022 | 169 |

| 170 | 0.0050404 | 48 | 50 | 0.0056196 | 109 | 43 | 0.0063163 | 170 |

| 95 | 0.0050498 | 49 | 55 | 0.0056255 | 110 | 53 | 0.0063217 | 171 |

| 21 | 0.0050560 | 50 | 74 | 0.0056296 | 111 | 150 | 0.0063330 | 172 |

| 25 | 0.0050603 | 51 | 154 | 0.0056363 | 112 | 111 | 0.0063364 | 173 |

| 20 | 0.0050791 | 52 | 69 | 0.0056388 | 113 | 103 | 0.0063750 | 174 |

| 78 | 0.0050879 | 53 | 119 | 0.0056447 | 114 | 100 | 0.0064080 | 175 |

| 87 | 0.0050928 | 54 | 81 | 0.0056666 | 115 | 92 | 0.0064706 | 176 |

| 14 | 0.0050977 | 55 | 51 | 0.0056849 | 116 | 94 | 0.0065087 | 177 |

| 3 | 0.0050979 | 56 | 54 | 0.0056977 | 117 | 45 | 0.0065936 | 178 |

| 112 | 0.0051050 | 57 | 148 | 0.0057056 | 118 | 32 | 0.0066193 | 179 |

| 121 | 0.0051128 | 58 | 115 | 0.0057134 | 119 | 42 | 0.0066241 | 180 |

| 67 | 0.0051468 | 59 | 26 | 0.0057135 | 120 | 86 | 0.0067931 | 181 |

| 116 | 0.0051541 | 60 | 70 | 0.0057182 | 121 | 101 | 0.0068839 | 182 |

| 176 | 0.0051605 | 61 | 117 | 0.0057442 | 122 | 105 | 0.0071148 | 183 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).