Submitted:

27 May 2024

Posted:

27 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Experimental Design

| Trial | Treatment symbol |

Topping method |

Plant density | Light intensity |

| plants m-2 | μmol m-2 s-1 | |||

| Topping method | LTi | Late | 39 | 100 |

| ET-LDii | Early | 72 | 100 | |

| ET-HDiii | Early | 126 | 100 | |

| Light intensity | ET-P050iv | Early | 72 | 50 |

| ET-P100iv | Early | 72 | 100 | |

| ET-P150iv | Early | 72 | 150 |

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Yield of Pea Shoots

2.3.2. Leaf Gas Exchange Measurement

2.3.3. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Characteristics

2.3.4. Quality Determination

2.3.5. Light Energy Use Efficiency

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth of Pea Shoots under Different Cultivation Methods

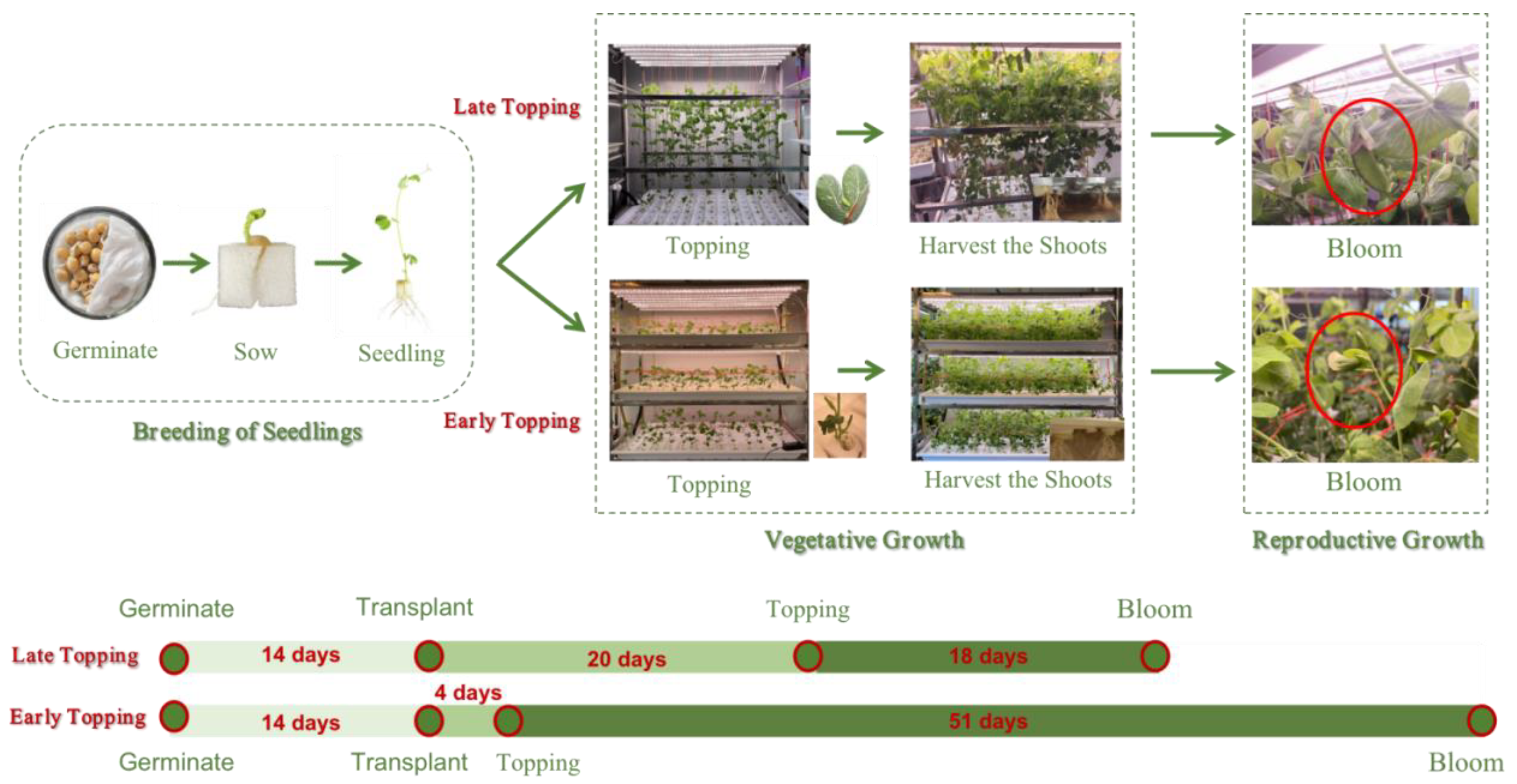

3.1.1. Growth Process of Pea Shoots under Different Cultivation Methods

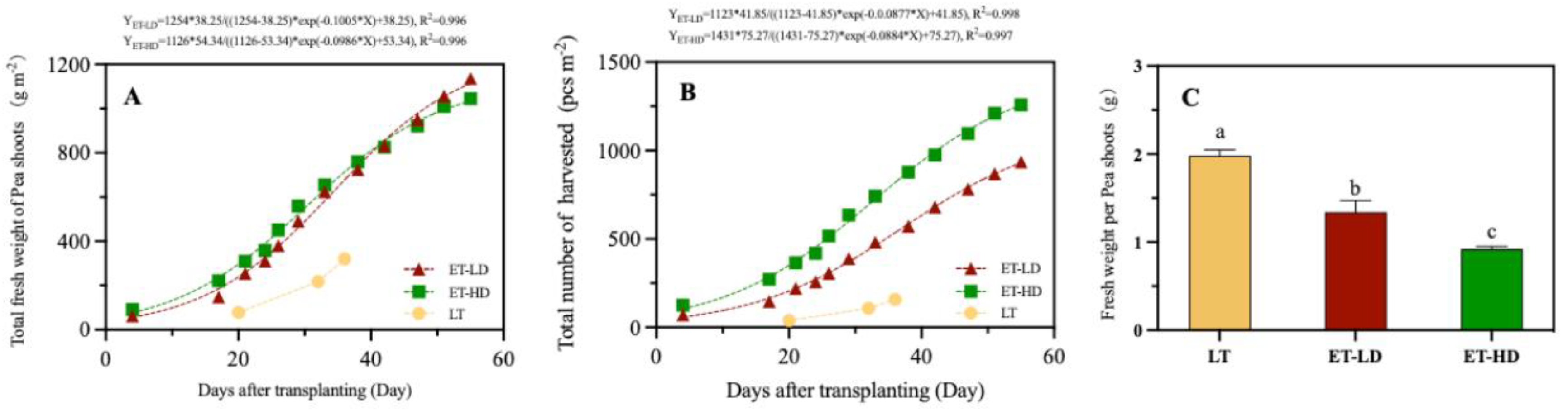

3.1.2. Yield of Pea Shoots under Different Cultivation Methods

3.2. Effect of Light Intensity Combined with ET on Growth and Quality of Pea Shoots

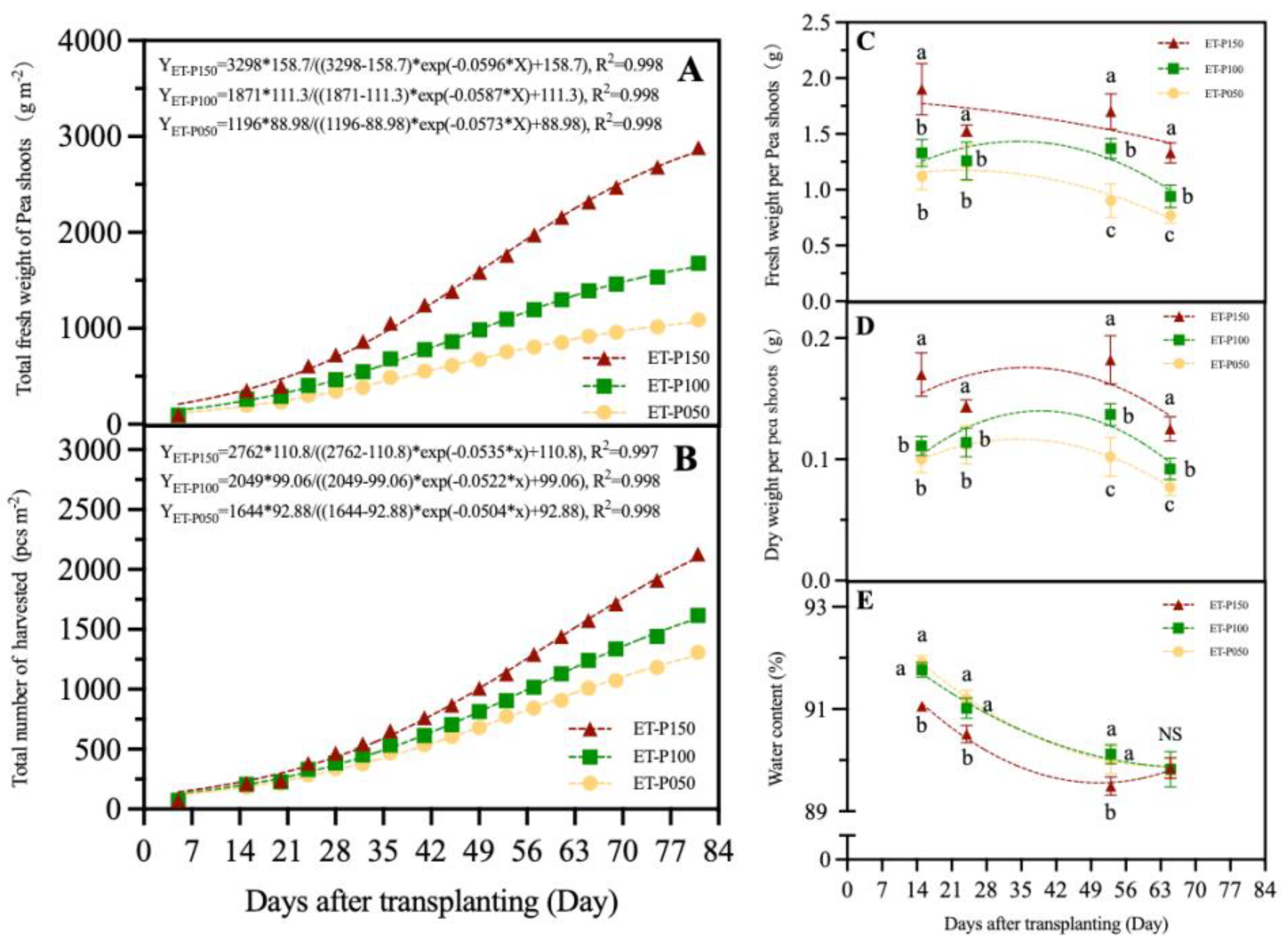

3.2.1. Biomass of Pea Shoots under Different Light Intensity Combined with ET

3.2.2. Leaf Gas Exchange Measurement of Pea Shoots at Different Periods

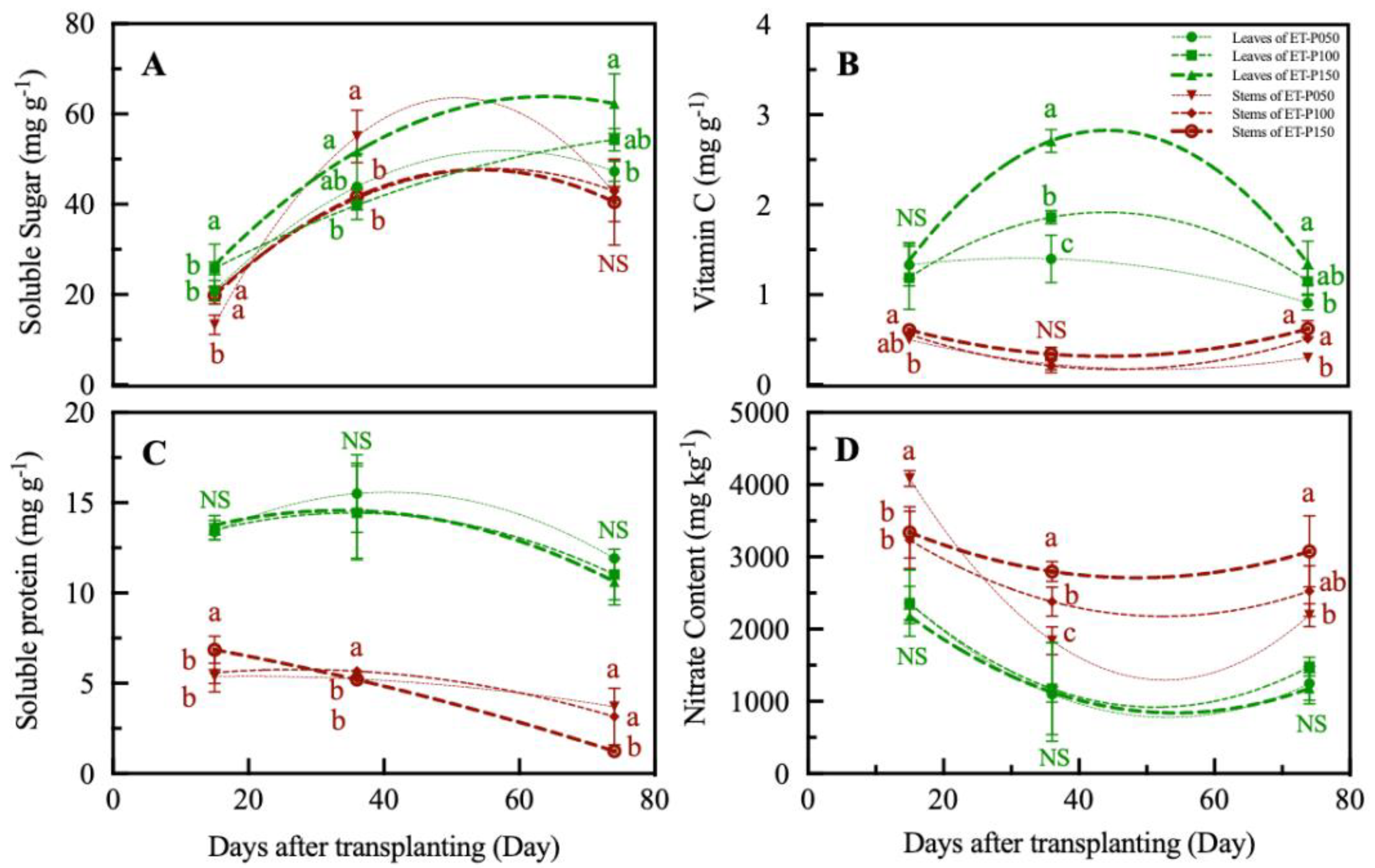

3.2.3. Quality of Pea Shoots at Different Periods

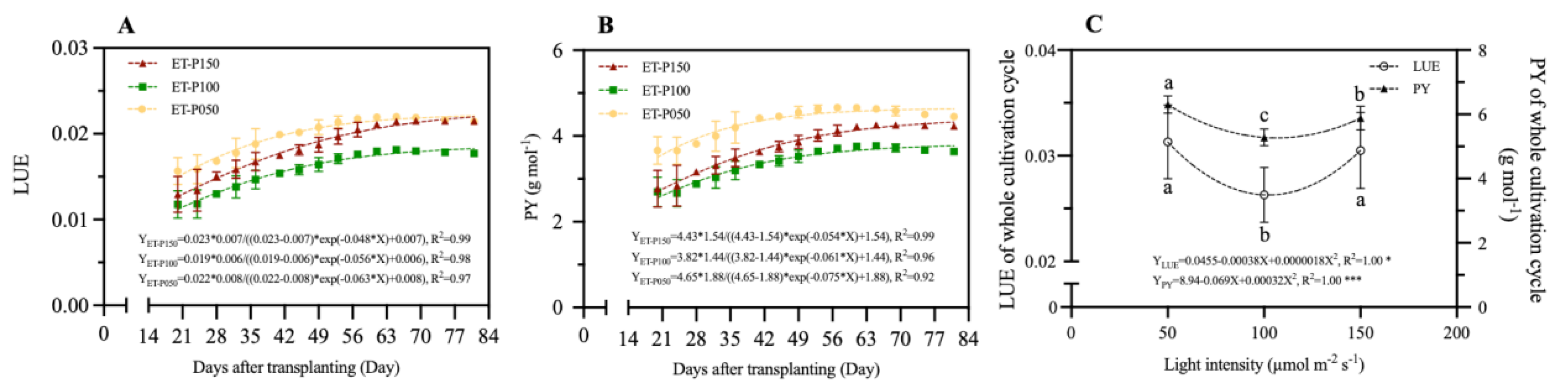

3.2.4. Light Energy Use Efficiency of Pea Shoots at Different Periods and Stages

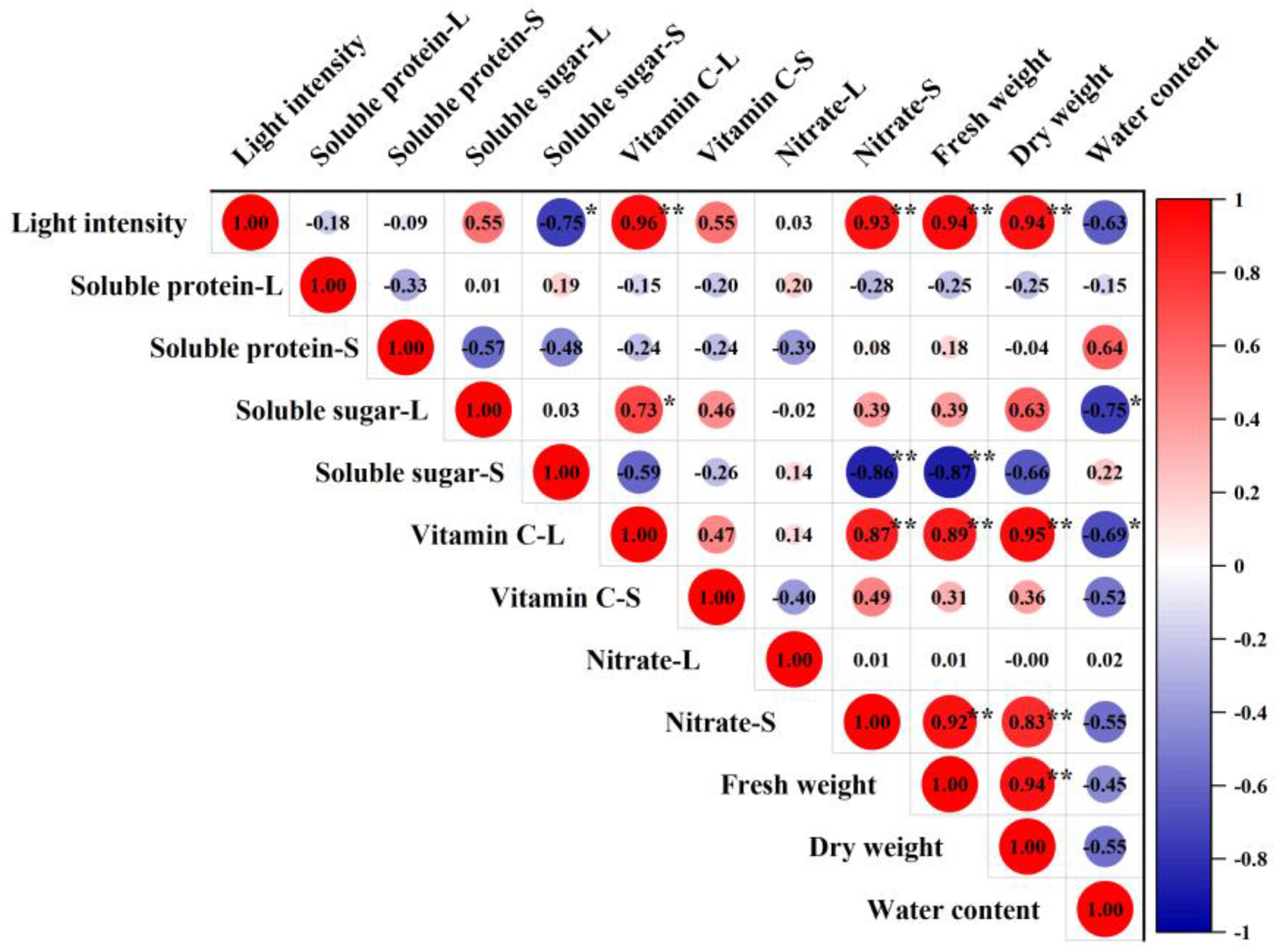

3.2.5. Correlation Analysis between Light Intensity and Various Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. Early Topping and Appropriate Planting Density Can Improve the Yield

4.2. Higher Light Intensity Combined with ET-LD Can Improve Yield and Quality

4.3. The LUE of Pea Shoots Showing an Optimal Response with Planting Period

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Miles, C.A.; Sonde, M. Pea shoots. Washington State University Cooperative Extension, Pullman, WA, USA, 2003. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242372648_Pea_Shoots.

- Lim, T.K. Edible medicinal and non-medicinal plants: Volume 1. Fruits 2013, 16, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y. Response of growth, yield, and quality of edible-podded snow peas to supplemental LED lighting during winter greenhouse production. Can J Plant Sci 2019, 99, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Sun, B.; Xue, S.L.; Xia, X.; Tian, Y.X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, S. Analysis of main nutrients, bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacities in pea tip. Food Machinery 2016, 32, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Herrero, M.; Mendiola, J.A.; Oliva-Teles, M.T.; Ibanez, E.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Assessment of nutritional and metabolic profiles of pea shoots: The new ready-to-eat baby-leaf vegetable. Food Res Int 2014, 58, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.T.; Yang, F.; Hu, C.Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.B.; Lv, M.Y.; Wang, L.P. A New Pea Variety Specialized for Sprout Production-Yunwan No.1. China Veg 2020, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Llewellyn, D.; Zheng, Y. Response of growth, yield, and quality of pea shoots to supplemental light-emitting diode lighting during winter greenhouse production. Can J Plant Sci 2018, 98, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y. Response of growth, yield, and quality of edible-podded snow peas to supplemental LED lighting during winter greenhouse production. Can J Plant Sci 2019, 99, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, T.; Maki, S.L. Pisum sativum L. shoot architecture manipulation in hydroponics with LED lighting and increased dissolved oxygen. Acta Hortic 2022, 1337, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagaki, M.; Hara, H.; Kozai, T. Micro- and mini-PFALs for improving the quality of life in urban areas. In Plant Factory; Chiba, Japan, 2016; pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozai., T.; Niu, G. Plant factory as a resource-efficient closed plant production system. In Plant Factory; Japan, 2016; pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgoustaki; Despoina, D.; Xydis, G. Indoor vertical farming in the urban nexus context: Business growth and resource savings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozai, T. Resource use efficiency of closed plant production system with artificial light: Concept, estimation and application to plant factory. P Jpn Acad B-Hys 2013, 89, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.X.; Kozai, T.; Niu, G.; Zhang, X. Light-emitting diodes for horticulture: Materials, processes. Devices Appl 2019, 513–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.M.; Li, H.Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, H.; Cao, Z.Y.; Manukovsky, N.S.; Liu, H. Interaction effects of light intensity and nitrogen concentration on growth, photosynthetic characteristics and quality of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. Var. youmaicai). Sci Hortic 2017, 214, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S. Experimental principle and technology of plant physiology and biochemistry. Higher Education Press: China, 2000; pp. 123–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cataldo, D.A.; Haroon, M.; Schrader, L.E.; Youngs, V.L. Rapid colorimetric determination of nitrate in plant-tissue by nitration of salicylic-acid. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 1975, 6, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, G.; Pistillo, A.; Orsini, F.; Cellini, A.; Spinelli, F.; Nicola, S.; Fernandez, J.A.; Crepaldi, A.; Gianquinto, G.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Optimal light intensity for sustainable water and energy use in indoor cultivation of lettuce and basil under red and blue LEDs. Sci Hortic 2020, 272, 109508–109518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.L.; Gao, T.M.; Zhang, H.Y.; et al. Effect on sesame yield, quality and photosynthetic character after topping in different stage in different site. Acta Agri BorealiSinica 2010, 25, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, S.; Missihoun, T.; Germain, H. Early topping: An alternative to standard topping increases yield in cannabis production. Plant Sci Today 2020, 7, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.P.; Shen, H.H.; Luo, Y.K.; Xu, L.C.; Liu, S.S.; Zhu, Y.K.; Zhao, M.Y.; Xing, A.J.; Fang, J.Y. Effects of planting density on growth and biomass of Medicago sativa. Chin J Plant Ecol 2020, 44, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D. Impact of plant density on yield and yield components of pea (Pisum sativum ssp. sativum L.) cultivars. J Agric Biol Sci 2013, 8, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, J.M.; Warkentin, T.; Shirtliffe, S. Basal branching in field pea cultivars and yield-density relationships. Can J Plant Sci 2010, 90, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Yang, Q.C.; Song, W.P.; Wang, L.C.; Guo, W.Z.; Xue, X.Z. Growth and nutritional properties of lettuce affected by different alternating intervals of red and blue LED irradiation. Sci Hortic 2017, 223, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromdijk, J.; Głowacka, K.; Leonelli, L.; Gabilly, S.T.; Iwai, M.; Niyogi, K.K.; Long, S.P. Improving photosynthesis and crop productivity by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science 2016, 354, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Z.H.; Cui, J.J.; Fu, Y.M.; Yu, J.; Liu, H. Optimization of light intensity and nitrogen concentration in solutions regulating yield, vitamin C, and nitrate content of lettuce. J Hortic Sci Biotech 2021, 96, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.S.; Zhou, X.L.; Liu, M.Q. Effect of LED supplemental lighting system on the growth of pea shoots. 2013 10th China SSL 2013, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Delden, S.H.; SharathKumar, M.; Butturini, M.; et al. Current status and future challenges in implementing and upscaling vertical farming systems. Nat Food 2021, 2, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.H.; Krishnakumar, S.; Atulba, S.L.S.; Jeong, B.R.; Hwang, S.J. Light intensity and photoperiod infuence the growth and development of hydroponically grown leaf lettuce in a closed-type plant factory system. Hortic Environ Biote 2013, 54, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsdorff, H.H.M.; Barbosa, K.B.F.; Volp, A.C.P.; Bressan, B.P.J.; Zulet, M.A.; Martinez, J.A. Vitamin C and fibre consumption from fruits and vegetables improves oxidative stress markers in healthy young adults. Br J Nutr 2012, 107, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.Y.; Mei, Y.H.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.J.; Yang, Z.C. CO2 enrichment promoted the growth, yield and light-use efficiency of lettuce in plant factory with artificial lighting. Agron J 2021, 113, 5196–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutsinos, O.; Mastoraki, M.; Ntatsi, G.; Liakopoulos, G.; Savvas, D. Comparative assessment of hydroponic lettuce production either under artificial lighting, or in a Mediterranean greenhouse during wintertime. Agriculture 2021, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Ewa, B.; Bozena, M.; Stanislaw, K.; Jacek, D.; Waldemar, K.; Anna, W.; Justyna, S.G. Assessment of romaine lettuce cultivars grown in a vertical hydroponic system at two levels of LED light intensity. Sci Hortic 2023, 313, 111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.G. Assimilatory Nitrate Reduction. In Techniques in bioproductivity and photosynthesis (Second Edition); Spain, 1985; pp. 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.K.; Subedi, P.P.; Walsh, K.B. Robustness of tomato quality evaluation using a portable Vis-SWNIRS for dry matter and colour. Int J Anal Chem 2017, 2863454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.A.; Tong, Y.X.; Li, L.; Sahari, S.Q.; Almogahed, A.M.; Cheng, R.F. Integrative effects of CO2 concentration, illumination intensity and air speed on the growth, gas exchange and light use efficiency of lettuce plants grown under artificial lighting. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.P.; Zhang, H.L.; Huang, Z.A.; Yang, X.L.; Kang, H.J. Model construction of light use efficiency and water use efficiency based on a photosynthetic mechanistic model of light response. Plant Physiol 2017, 53, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.P.; Yang, X.L.; Kang, H.J. Comparison of light-use and water-use efficiency for C3 and C4 species. Acta Agri Zhejiangensis 2016, 28, 1867–1873. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.B.; Tao, F.L. Research progress on the mechanism of high light use efficiency in wheat. Chinese Journal of Agrometeorology 2022, 43, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.G.; Li, P.P.; Wu, Y.Y. Effects of different light intensities on chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics and yield in lettuce. Sci Hortic 2012, 135, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trial treatment | Pn | Gs | Ci | Tr | Fv/Fm | ||

| μmol m-2 s-1 | mol m-2 s-1 | μmol mol-1 | mmol m-2 s-1 | ||||

| New leaves | 41 DATi | ET-P050 | 4.6 ± 0.6 C c | 0.29 ± 0.10 A a | 357.1 ± 11.8 A a | 1.4 ± 0.3 NS | 0.835 ± 0.001 NS |

| ET-P100 | 7.0 ± 0.9 B b | 0.24 ± 0.03 A ab | 333.3 ± 5.7 A b | 1.3 ± 0.2 NS | 0.837 ± 0.004 NS | ||

| ET-P150 | 10.2 ± 0.2 A a | 0.19 ± 0.03 A b | 285.4 ± 15.3 B c | 1.2 ± 0.2 NS | 0.835 ± 0.008 NS | ||

| 80 DAT | ET-P050 | 1.2 ± 0.1 C c | 0.30 ± 0.06 A b | 385.8 ± 0.9 A a | 2.0 ± 0.3 NS | 0.842 ± 0.002 NS | |

| ET-P100 | 3.3 ± 0.2 B b | 0.51 ± 0.05 A a | 379.1 ± 1.5 A a | 2.8 ± 0.7 NS | 0.839 ± 0.003 NS | ||

| ET-P150 | 5.5 ± 0.7 A a | 0.48 ± 0.11 A a | 367.0 ± 5.9 B b | 2.6 ±1.2 NS | 0.845 ± 0.003 NS | ||

| Old leaves | 41 DAT | ET-P050 | 4.8 ± 0.4 B b | 0.37 ± 0.11 A a | 362.6 ± 3.3 A a | 1.7 ± 0.3 A a | 0.814 ± 0.004 B b |

| ET-P100 | 7.0 ± 0.4 A a | 0.20 ± 0.04 B b | 320.4 ± 12.5 B b | 1.1 ± 0.2 B b | 0.824 ± 0.008 AB a | ||

| ET-P150 | 7.6 ± 1.1 A a | 0.22 ± 0.02 AB b | 321.0 ± 16.1 B b | 1.3 ± 0.1 AB b | 0.832 ± 0.001 A a | ||

| 80 DAT | ET-P050 | 3.5 ± 0.2 B b | 0.52 ± 0.08 NS | 387.3 ± 1.7 A a | 2.7 ± 0.4 B b | 0.796 ± 0.011 B b | |

| ET-P100 | 3.5 ± 0.4 B b | 0.69 ± 0.07 NS | 380.8 ± 0.8 A a | 3.5 ± 0.2 A a | 0.820 ± 0.004 A a | ||

| ET-P150 | 5.3 ± 0.1 A a | 0.53 ±0.25 NS | 367.1 ± 11.4 A b | 2.5 ± 0.2 B b | 0.831 ± 0.004 A a | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).