1. Introduction

As part of the valorization of Tunisian flora,

P. tomentosa (Thunb.), hardwood tree, plantation which is a majestic tree originating from Asia and which belongs to the Paulowniaceae family [

1]. There are different species of Paulownia but the most important of them include P. kawakamii, P. catalpifolia, P. australis, P. albiphloea, P. fargesii, P. fortunei, P. elongata, and

P. tomentosa [

2].

P. tomentosa is considered a park and ornamental tree, it is widespread in temperate zones [

3]. In fact, this tree is largely planted for their multiple uses in environment (afforestation, reclamation of degraded soils), economy (wood production) and for medicinal purposes [

4].

Moreover,

P. tomentosa has various assets on biodiversity, it is considered a soil builder, also its leaves are rich in lipids, proteins and minerals, its flowers are appreciated by bees thanks to the scent of lavender. In addition, it is a nitrogen-fixing tree very resistant to high salt levels and retains the soil well. This pioneer species always seeks light and lives in open habitats. In places with several other young plantations are developing therefore the native vegetation can be affected by a lack of light due to rapid growth of

P. tomentosa [

5].

The bioclimatic boundaries of Paulownia will probably be pushed back to altitude be-cause this species, thanks to its robustness, hardiness and rapid growth, is one of those trees that will be able to adapt to this climate change [

5]. This miraculous tree can absorb up to ten times more CO2 than most other plant species, which allows purifying the atmospheric air in a more efficient way [

6]. In addition,

P. tomentosa presents famous ability to grow and produces important biomass (60-80 ton/ha) [

6]. It is truly a providential specific source of wood which provides excellent material for furniture, toys, plywood, musical instruments and packing boxes [

7]. Another specificity of this species is its ability to grow in dense plantations of about 2000 trees per hectare which makes it quite profitable from an economic point of view [

8].

P. tomentosa can withstand different temperatures, and it is also known to grow at an altitude of 2000 m. Thus, under optimal conditions,

P. tomentosa can expect a chest height increase of 6 meters per year. However, it is a tree that has a good rooting system and adapts to various types of soils except waterlogged soils [

9]. The horizontally extended root system of

P. tomentosa prevents surface erosion of the soil and thanks to the regeneration of the roots its rapid growth this species can survive forest fires [

5].

P. tomentosa tree adapts to various soil types, even if it resists unfavorable conditions. This species requires hard peat and prefers medium loamy soil as well as deep soil. It can grow in alkaline and acidophilic soils with a pH of 5-8 but preferably a neutral pH.

P. tomentosa also grows very well in very salty and nutrient-poor soils thanks to its ability to absorb Ca++ and Mg++ ions [

9].

Paulownia has been used for various herbal purposes to relieve bronchitis, especially to reduce cough, asthma and phlegm, conjunctivitis, dysentery, enteritis, erysipelas, gonorrhea, hemorrhoids, mumps, traumatic hemorrhage, tonsillitis and lower blood pressure [

10,

11]. It is previously indicated that

P. tomentosa flower extracts are of particular interest including the presence of flavonoids, and especially apigenin which has antioxidant, antiinflammatory, antispasmodic and antihypertensive effects [

1]. [

12] reported that the es-sential oil extracted from

P. tomentosa flowers has antibacterial activity (Bacillus subtilis NRRL B-543, Staphylococcus aureus NRRL B-313 and Escherichia coli NRRL B-210), potential efficacy against bronchial asthma in Cavia porcellus, neuroprotective effects to inhibit glutamate toxicity [

1]. According to Bahri [

13], Paulownia cortex is also largely used to cure several diseases (dysentery, gonorrhea, and erysipelas).

P. tomentosa plants can be established using numerous types of planting stock, including bare root seedlings, seeds, containerized seedlings, and cuttings [

14]. Several studies showing that Paulownia is effectively propagated by seed and several vegetative means have been limited to plant production without determining the plants’ subsequent field growth. Using of traditional methods for propagation of Paulownia tree requires large areas and large numbers of workers [

15]. However, increasing demand on Paulownia in the market has pushed researchers to find appropriate methods of propagation. Plant tis-sue culture technique is one of the most important methods used in the propagation of Paulownia tree. However, there are also some inherent problems with in vitro culture such as: a) excessive callus growth at the base of explants and weakened axillary shoot proliferation; b) development of adventitious shoots on callus at the explant base; c) explant pushed out of the medium by emerging leaves; and d) difficulty in cultures observation due to large sized leaves [

16].

More precisely,

P. tomentosa and other species (P. elongata, P. fortunei, and their hy-brids results) were produced in nursery to cover the multiplex human needs. The dra-matic success of

P. tomentosa nursery production is the consequence of its ability to tolerate temperature fluctuations [

17]. In general, the most used culture media in plant micro-propagation is Murashige and Skoog media (MS), which usually depend on addition of micro and macro elements to culture media supplemented with growth regulators. Among these issues is the application of commercial rooting hormones. Exogenous ap-plication of commercially available auxins, such as Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) and α-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA), increases rooting in stem cuttings, but success rates vary by species [

18]. However, several culture medias are used for micropropagation of Paulownia tree, with different concentrations of growth regulators (benzyl adenine (BA) and Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA)) which, added to the dietary medium [

19], and MS culture media are usually used in the micropropagation of P. elongata tree [

20].

Tryptophan aminotransferase of Arabidopsis1 (TAA1) and the YUCCA enzyme fam-ily are used in the primary auxin biosynthesis pathway [

21]. Tryptophan is transformed into indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPyA) by the TAA1 family of aminotransferase enzymes. The YUCCA family of flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes then transforms IPyA into IAA. The conversion of IPyA to IAA is the rate-limiting step in this process; overexpression of YUCCA family members causes high auxin levels. Furthermore, tissue-specific expression of distinct YUCCA family members allows for de novo auxin production, which drives specific elements of plant development [

22]. In addition to IAA production via the IPyA route, the pool of active auxin can be regulated by inputs from other storage forms and precursors, including as IAA conjugates and indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) [

23].

For this, our specific objectives were obtaining a suitable method to propagate P. to-mentosa tree and obtain large quantities to obtain a successful procedure for its cultivation through testing the survival sprouting derived from different root cuttings diameters, IBA (Inodol -3-Butiric- Acid) levels, and type of soils under Tunisian climatic conditions. Also, we evaluated the phytochemical characterization of the new resulted plants based on the determination of the contents of pigments, phenolic compounds. In addition, the phenology of P. tomentosa flowers were estimated.

3. Results and Discussion

Because of the economic potential of Paulownia, it is propagated to utilize the ad-vantage of its wood in many businesses; thus, certain governments invest in these trees to reduce poverty and combat COVID-19 [

31]. Obtaining large quantities of plants in a short period is one of the most important challenges facing scientific researchers. The propagation of these trees faced various issues such as seed-borne diseases and pests, poor seed germination, and altered growth habits. As well, seedling growth is slow compared to root cutting originating from plants [

32]. About asexual propagation technique, the survival and acclimation ability and costs of production (cost influence new plant price) of the new sprouts must be studied [

33]. In Paulownia clonal forestry, effective vegetative propagation is crucial for producing high-quality clones of the plant species [

34]. According to Magar et al. [

35] and Bochnia [

16], Paulownia production is more successful by the traditional technique (cutting root) when compared to in vitro culture one presenting inherent problems. Growth hormones promote plant growth, productivity, and quality. Growth regulators can also be combined with natural materials, followed by conventional breeding, to increase Paulownia tree out-put [

36]. In this regard, Bhojwani and Dantu [

37] noted that cytokinins kinetin and zeatin are frequently utilized to increase cell differentiation and cell division, whilst auxins such as (IAA), (NAA), and (IBA) are commonly employed to boost root formation. For these reasons, in our study cutting roots were used to realize Paulownia propagation depending on cutting diameter, soil type and growth hormone concentration.

3.1. Morphological traits of P. tomentosa sprouts under the three interactive parameters

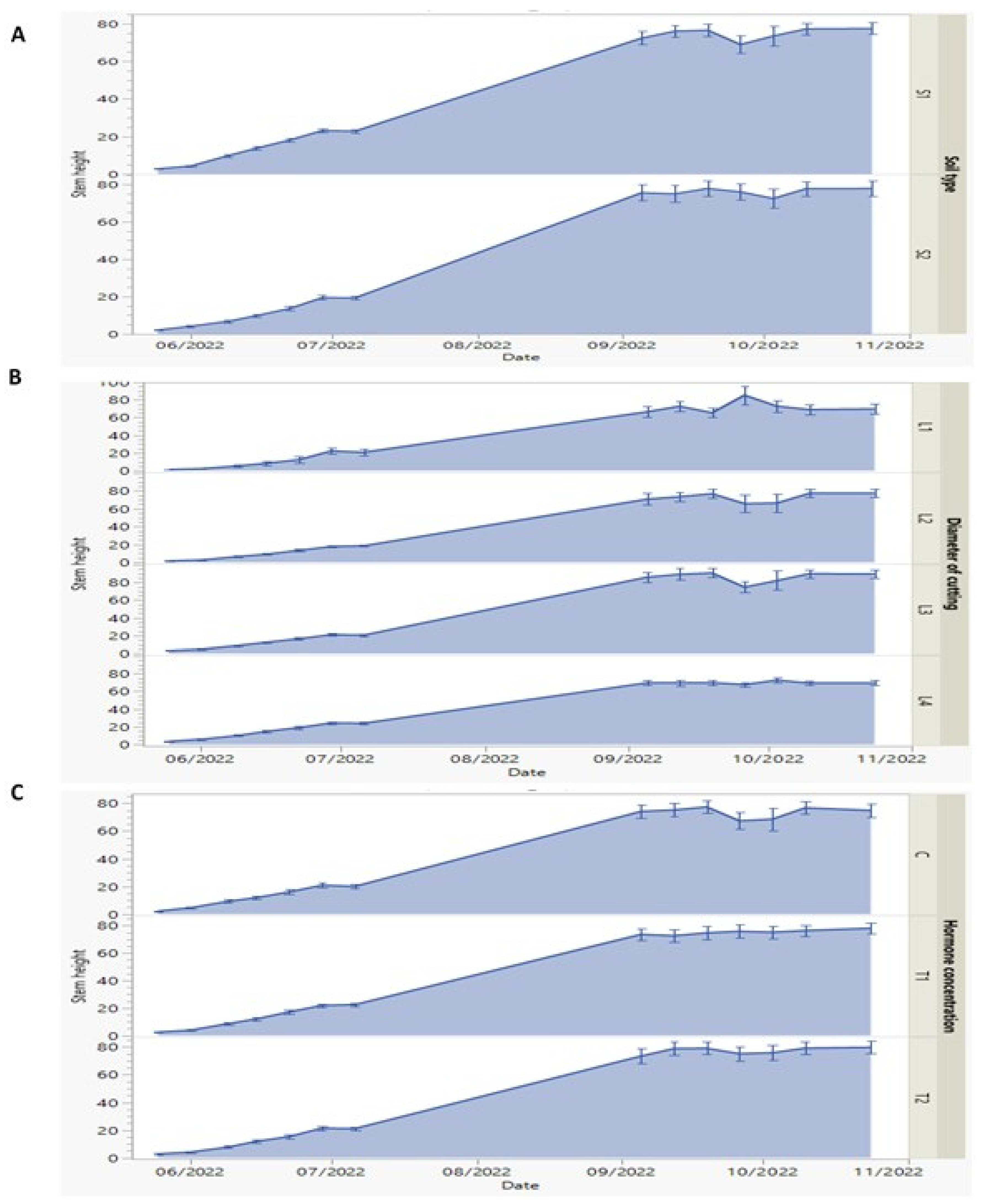

3.1.1. Kinetics of first-year growth parameters

The kinetic and dynamics of growth parameters (stem height and leaves numbers) were recorded from May to November 2022. During the first period (May- July) of growth, the elongation of stem was more pronounced in the studied seedlings under the three in-teractive factors. After six months, the growth parameters dropped during September 2022, then restored their increase until the end of the year as observed in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. According to Maqbool and Aftab [

38] and Preece et al. [

39], growth of woody species shoot is possible in winter, springer and until fall. For this reason, we can understand the growth of the new sprouts detected in our study reaching October (2022).

Regarding the interaction among the three interactive factors, the results showed mostly the same trend in elevation and decline in stem height records with some slight differences. According to soil type factor, the stem height records increased gradually over time until reach to 26th Sep., there was a slight decline as the values were 68.97 and 75.94 cm for S1 and S2 soil type, respectively.

While the decline of stem height under S2 soil type was recorded as 72.40 cm on 3rd October, then it increased until reaching the final stem height records as 80 cm as shown in

Figure 2A. Moreover, we can confirm that the noted one week shift in growth com-partment of the juvenile Paulownia grown on S2 soil type, is related to the distribution of three natures of soil (potty, silt and sandy) mixed. We suggested that the water state in the rhizospheres reflecting the soil water retention capacity that affects roots development. In fact, high water retention results in O2 deficiency causing shoot growth reduction ion [

38].

The stem height records showed differences with different root cuttings diameters (L1, L2, L3, and L4). On the 26th of September, the highest stem values were recorded as 85.33 cm with L1 diameter. With L2 cutting diameter, the stem height decreased to 65.79 cm and the decline was less (74.85 cm) with L3 diameter at the same date. In addition, the stem height showed the lowest records with L4 among the rest root cutting diameters rec-ords. When comparing the effect of root cutting diameters effects, the elevation of stem height was more important correlated when the root cuttings diameter was small as ob-served in

Figure 2B. In this investigation, the cutting diameter did not affect directly the shoot growth in height. It seems that cutting diameter affects basely the rooting density causing enhancement of shoot growth and development. In addition, the results con-cluded that the smaller diameter (L1) and laid horizontally, correspond to the more pro-nounced growth. Similar suggestions that there is a positive relationship between cutting root diameter and ability to regenerate have been noted by Ede et al. [

40].

Regarding hormone concentrations effect on the stem height (

Figure 2C), we noticed that T1 and T2 concentrations showed a slight increase in their values compared to the C (control). The stem height in more than 20 cm at July (2022). After 4 months (November 2022), the height reached 80 cm depending on the concentration of hormone. On the 26th of September, the stem height decreased to 67.40 cm at C treatment, while it increased to 75.87 and 75.22 cm under T1 and T2 concentrations, respectively. Among the three inter-active factors, the root cutting diameters factor was the most effective as in L1 diameter the stem height showed the maximum value.

In our study, regardless of the hormone concentration, the root cuttings showed root-ing success and shoot development, similarly as showed by Antwi-Wiredi et al. [

41]. Also, the positive effect of growth hormone application was more pronounced when root cut-ting diameter is small (L1). The beneficial effect of growth hormone was mentioned by Mohamad et al. [

32], who essay micro-propagation of Paulownia and put out that prolif-eration of roots and shoot part was largely induced by presence of growth hormone (IBA).

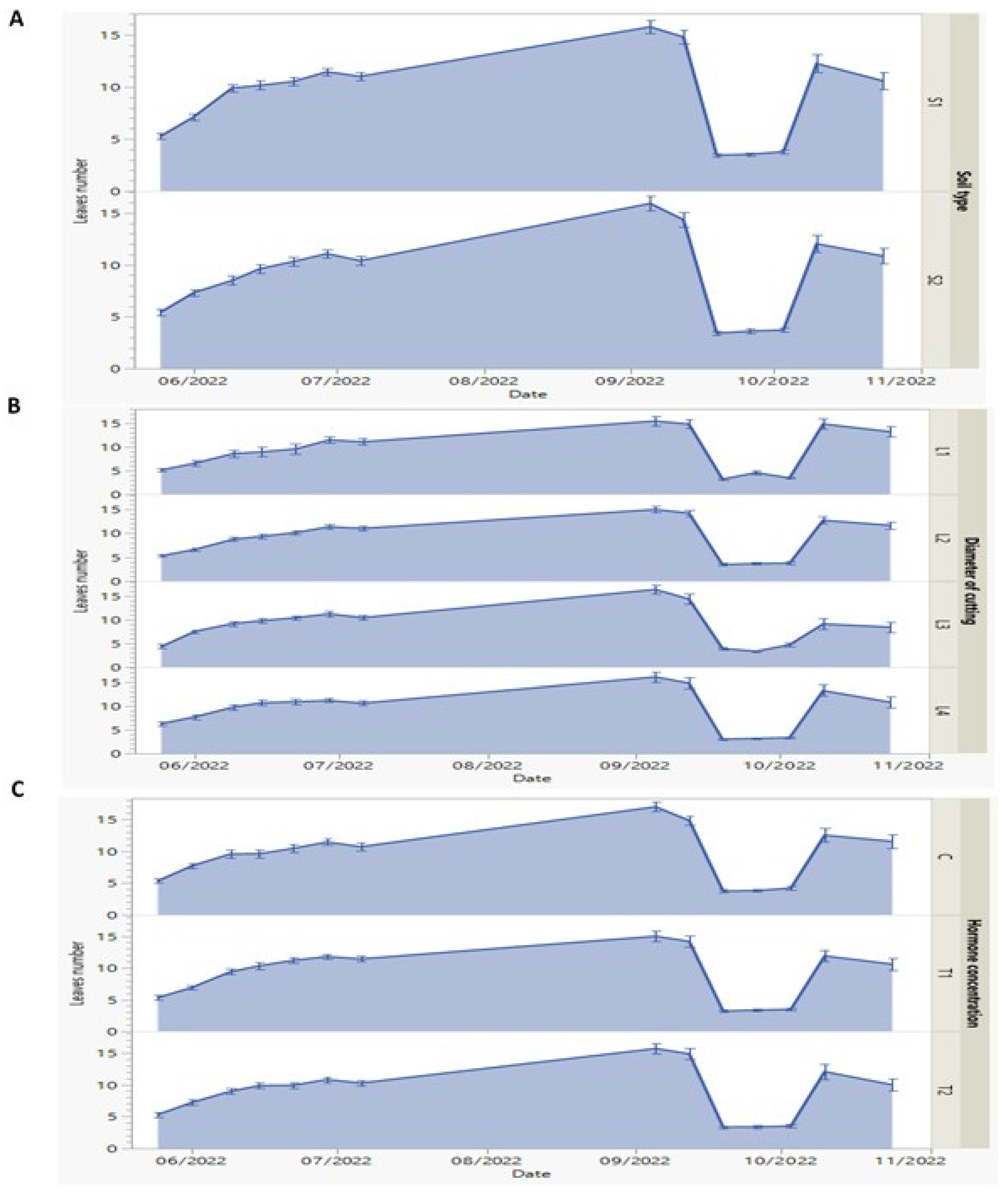

The number of leaves is one of the important aspects of plant growth due to its direct relation to photosynthetic capacity of the plant. Leaves numbers, which is, the second studied vegetative growth parameter, were dramatically affected by root cutting diameter than the two other factors (soil type and hormone concentration) (

Figure 3). Firstly, we dis-tinguished that the leaves number increased from May to September 2022. At the next month (October) there is spectacular leaves fall in all conditions of growth and then re-store again its increase to the end of the year. The leaves number seemed to be not affected by the S1 or S2 type of soil as illustrated (

Figure 3A). On the 26th of September, the number of leaves showed the lowest value (3.53) under S1 soil type and (3.60) under S2 soil type. The maximum values were recorded as 15.77 and 15.92 under S1 and S2 soil types, re-spectively.

There was no significant variation (P ≤ 0.05) observed in leaves number which con-firm that once rooting process is well established and stem growth is pronounced, the soil nature lost its influence on leaves development. This is important, because our principal aim is the research of factors performing growth, biomass production and principally survival ability of the new sprouts produced. These opinions were previously discussed and approved by Antwi-Wiredu et al. [

41].

In contrast, when focusing on the effect of root cutting diameters, L3 condition caused the maximum number of leaves (16.41) in the new seedlings (

Figure 3B). On the 26th of September, the leaves’ values showed different behavior as 4.57, 3.68, 3.35 and 3.18 cm for L1, L2, L3 and L4 diameters, respectively. In contrast to rooting process which prefers a smaller root cutting diameter (L1), the development of photosynthetic organs favored a bigger diameter (L3). This can be explained as mentioned by Stenvall et al. [

42] suggesting that the bigger diameter of root cutting furnish more assimilate amount to regeneration of new leaves.

According to the hormone concentrations, the different concentrations took the same behavior as the two rest factors. On the 26th of September, the leaves numbers decreased and recorded as 3.82, 3.35, 3.35, and 3.38 under C, T1 and T2, respectively as shown in

Figure 3C. This is logical because the primordial role of the hormone is assigned in the first step of experiment when forcing rooting process and growth in height as shown in the previous sections. Maqbool and Aftab [

38] have discussed similar findings in their study. On the other hand, Gerson Riffo et al. [

43], found that Paulownia plantlets genera-tion based on cuttings root propagation technique and their growth performance are prin-cipally linked to the cutting material and age of trees.

3.1.2. Measures of growth parameters of P. tomentosa every year in October (2023/ 2024)

The diagnostic of the new tree’s growth during 2023 and 2024 years, is to test their survive ability and acclimation with experimental conditions. The choice of October month is not marginal, but, because after this time, growth starts to slow down until it stops. In addition, Dubova et al. [

44] confirmed that April- November is the vegetative pe-riod of

P. tomentosa and June-October is the period of its intense growth. In fact, growth recovers every new year, and comportment reflected the trees responses to environmental, physiological, genetic and other several factors [

45]. More precisely, factors controlling growth recovery of woody species after traversing dormancy season [

46].

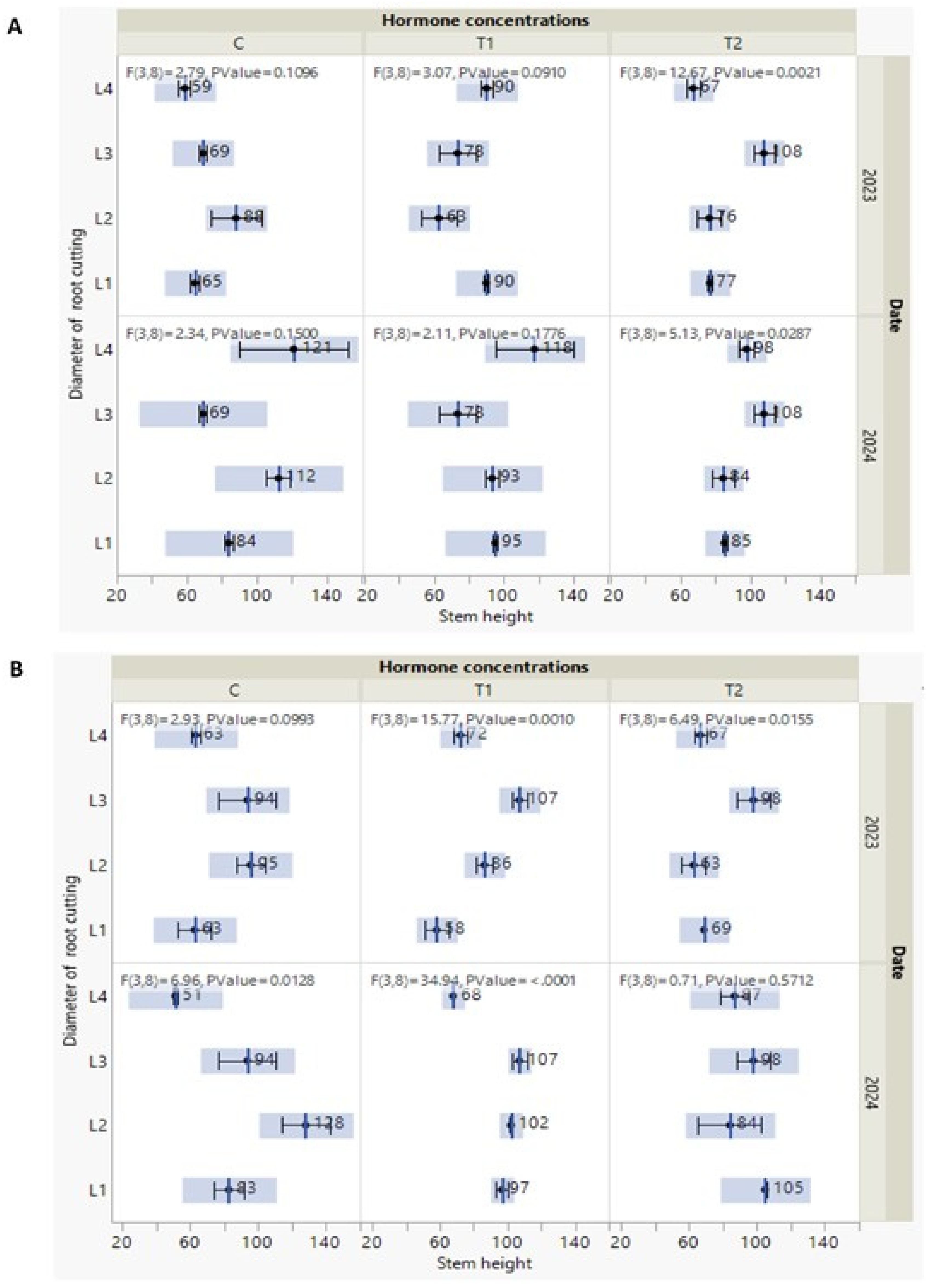

The data of this section was demonstrated by

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, showing measures of line of fit with F test of stem height and leaves number of

P. tomentosa taken out in Octo-ber 2023/ 2024 under the interactive effect of the studied treatments (soil type, cutting di-ameters, and hormone concentrations). F statistics with two degrees of freedoms (3, 8) and stem height values showed moderate significance (P ≤ 0.01) among T2 concentration and the other cutting diameters in S1 soil type in 2023, while (P ≤ 0.05) in 2024 as shown in

Figure 4A.

Regarding stem height, we noticed that, in October 2023 there is no distinguished ef-fects of hormone concentrations on stem height of the new

P. tomentosa grown on S1 type soil. Except in

P. tomentosa seedling issued from L3 cutting diameter, stem height in-creased (69, 73 and 108 cm) with hormone concentration (C, T1 and T2), respectively in both two years (

Figure 4A). Concerning plants grown on S2 type soil, a dramatic change of stem height was observed in October 2024.

P. tomentosa derived from L4 and L1 cutting diameters, showed an increase of stem height parallelly with augmentation of hormone concentration. Precisely, from control (C) to T1 and T2 concentrations, stem height gets higher from 51 to 68 and 87 cm in L4 and from 83 to 97 and 105 cm in L1. According to F statistics, stem height values under T1 concentration with other root cutting diameters showed high significance (P ≤ 0.001) in both 2023 and 2024 followed by T2 concentration with diameters in which it displayed a moderate significance (P ≤ 0.001) in 2023 (

Figure 4B).

According to all these observations, and regardless of the details, all the new trees continued to grow and had distinct morphological responses. These findings are persuasive as we seek approaches to make experiments effective and produce

P. tomentosa capa-ble of producing biomasses and meeting covering requirements. In addition, we agreed with the study of Antwi-Wiredi et al. [

41] who consider the cutting of survival is the first important success followed by the second aim to produce biomasses.

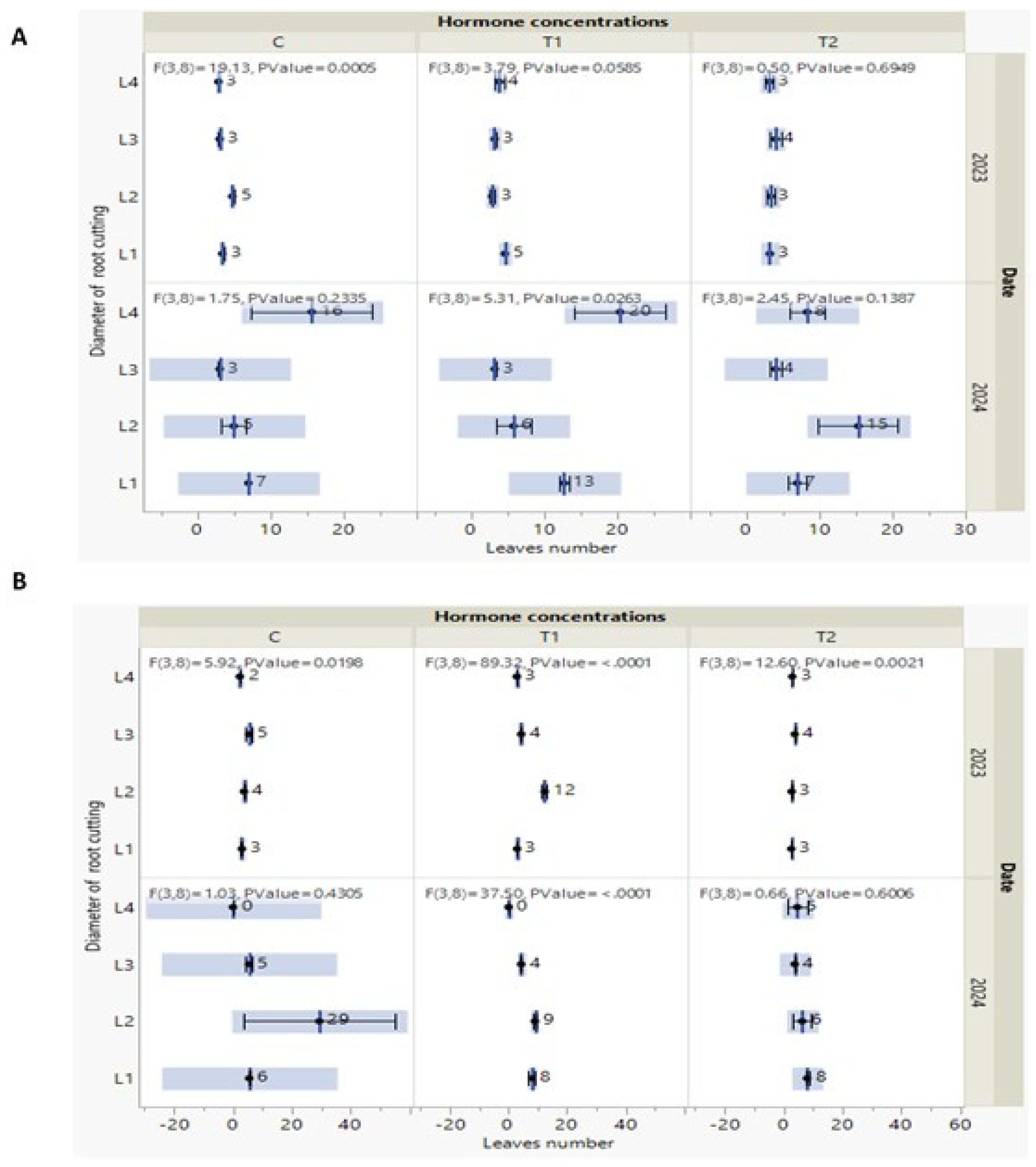

Regarding the other vegetative growth parameter (leaves numbers) measured in Oc-tober 2023, there are no significant effects of hormone concentration and soil types (S1 and

S2) on it (

Figure 5). Whereas, in October 2024 the higher stem height was detected in

P. tomentosa treated by L4/ T1 and grown on S1 soil type (

Figure 5A).

In October 2024, the higher number of leaves was detected in

P. tomentosa treated by L2/C (

Figure 5B). It is logical that after passing the steps of survival and acclimation re-flected by shoot development in height, to follow growth of leaves as source of assimilate securing general growth. Even though parameters during 2023, and the marginal did not affect the leaves number variation of these measured parameters, S2 soil type is the more exhibited condition to optimize

P. tomentosa macropropagation.

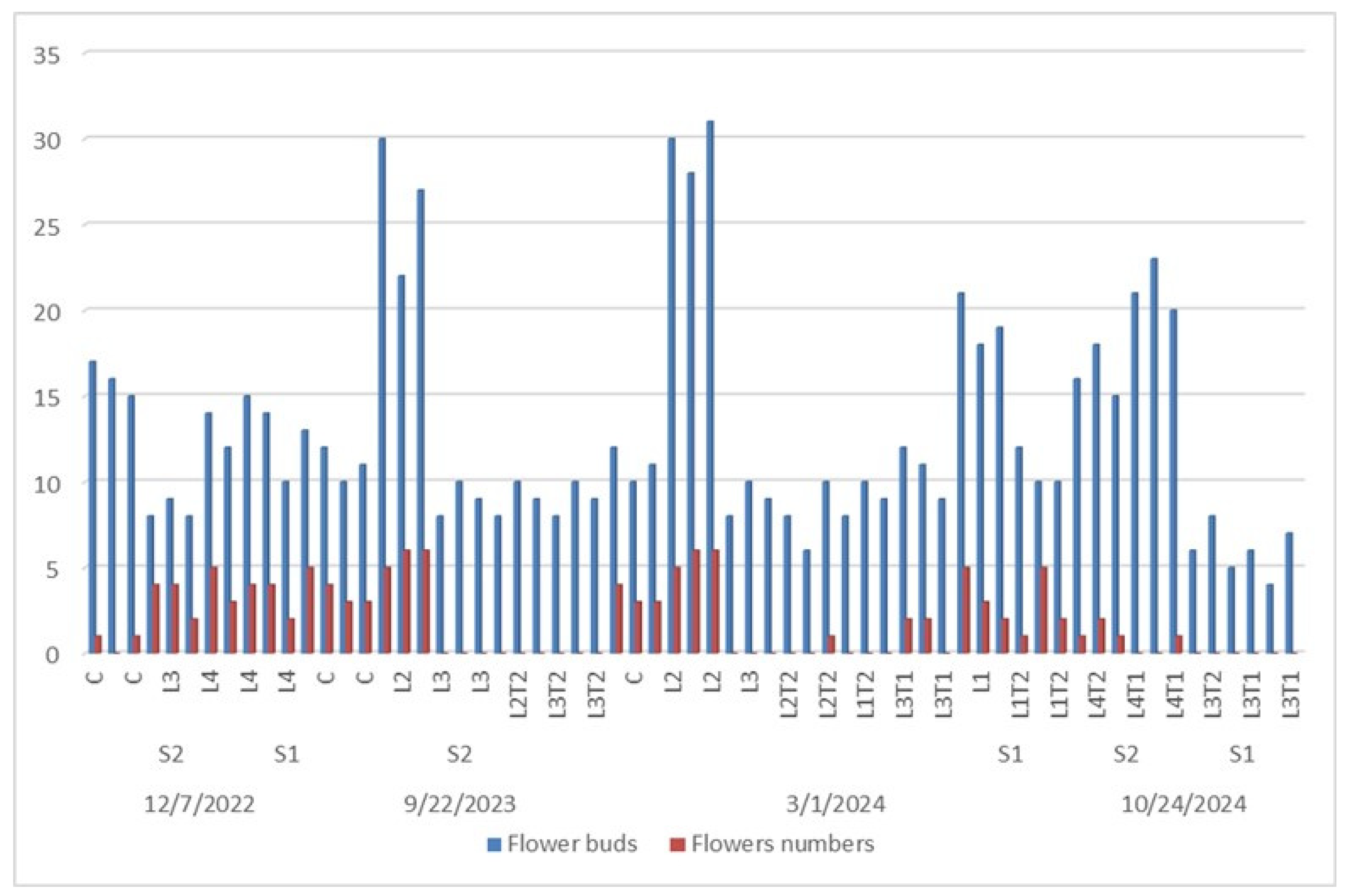

3.1.3. Generative flowering phenology of P. tomentosa

The flowering time is under influence of endogenous factors (genetic) and several en-vironmental signals (photoperiod, temperature), and stresses factors (biotic and abiotic) [

47,

48]. The follow up of flower phenology and flower bud’s emergence in

P. tomentosa under different interactive treatments (root cutting diameter, hormone concentration and soil type) effects were recorded every year during (2022, 2023 and 2024). The general over-view demonstrated different times and seasons of flower buds and flowers appearances as illustrated in

Figure 6.

The first appearance of buds which were not detected in all seedlings, was in De-cember 2022. At this time, only L4S2 (C, T1 and T2), S2L3T2 and S1L4T2 presented flow-ering buds. The greater number of buds was shown in S2L4C (16) followed by S1L4T2 (12) treated seedlings (

Figure 7).

The next year, bud flowers appeared in September (2023) in L4C, L4T2, L1C, L2T2, L2T1, L3T1 growing on S2 soil type. The greater bud flowers (26) were detected in S2L4T2 seedling. But, in 2024, flower buds’ appearance and flowering process taken place two times in several plants. Firstly, in March L1T1, L1T2, L2C, L2T2, L3T1 and L3T2 growing on S2 soil type and, S1L3 (T2 and C). Secondly, in October 2024, in L4T1S2, L4T2S2, L3T2S1 and L3T1S1. Based on all these data, during the three cycles (2022-2023-2024) the higher frequence of flower buds’ appearance was showed at the maximum of flower buds was noted in S2L4T2 (26) and S2L2T2 (29), respectively in March and October months (

Figure 7).

In this investigation, these data demonstrated the panoramic changes in flowering of

P. tomentosa issued from root cutting culture under several experimental conditions (cut-ting diameters, hormone concentration and soil types). The molecular study of Wang and Ding [

49] suggesting that the seasonal activity–dormancy growth, pleiotropic effects, ju-venility, habits media of trees are specific mechanisms regulating flowering time in per-ennial trees. Also, Dubova et al., [

44] suggested that generative organs development in Paulownia is largely affected by temperature. More precisely, when spring is warm, flow-ering starts in April. Whereas, after a strong winter bloom does not take place.

As explained by Wang and Deng [

49], in flowering plants, the length of life cycle, which is considered as vegetative growth, reproductive development and senescence suc-cession, varies according to many factors. Linked to one factor or all these previously de-scribed ones, we can understand the flowering state shown in this study. More than that, this study suggested that there is more than one endogenous difference in the new Pau-lownia trees issued from the different parameters of micropropagation fixed in our ex-periment.

To get more explications, we can rely on our data to studies of Wang [

50], and Wang and al., [

51], who suggested that induction of flowering process is related to transition from the juvenile vegetative phase to adult one (age pathway in flowering) regulation. For that, we can understand the margin of differences in flowering process showed in our study.

3.2. Biochemical contents in P. tomentosa sprouts under the three interactive parameters

P. tomentosa has a rich source of biologically active secondary metabolites such as (flavonoids, phenolic glycosides, lignans, quinones, terpenoids, glycerides, phenolic ac-ids) which is traditionally used in herbal medicine. Because the richness of plants in bio-chemical compounds is an important parameter for evaluating raw [

52,

53], we have measured the content of several compounds.

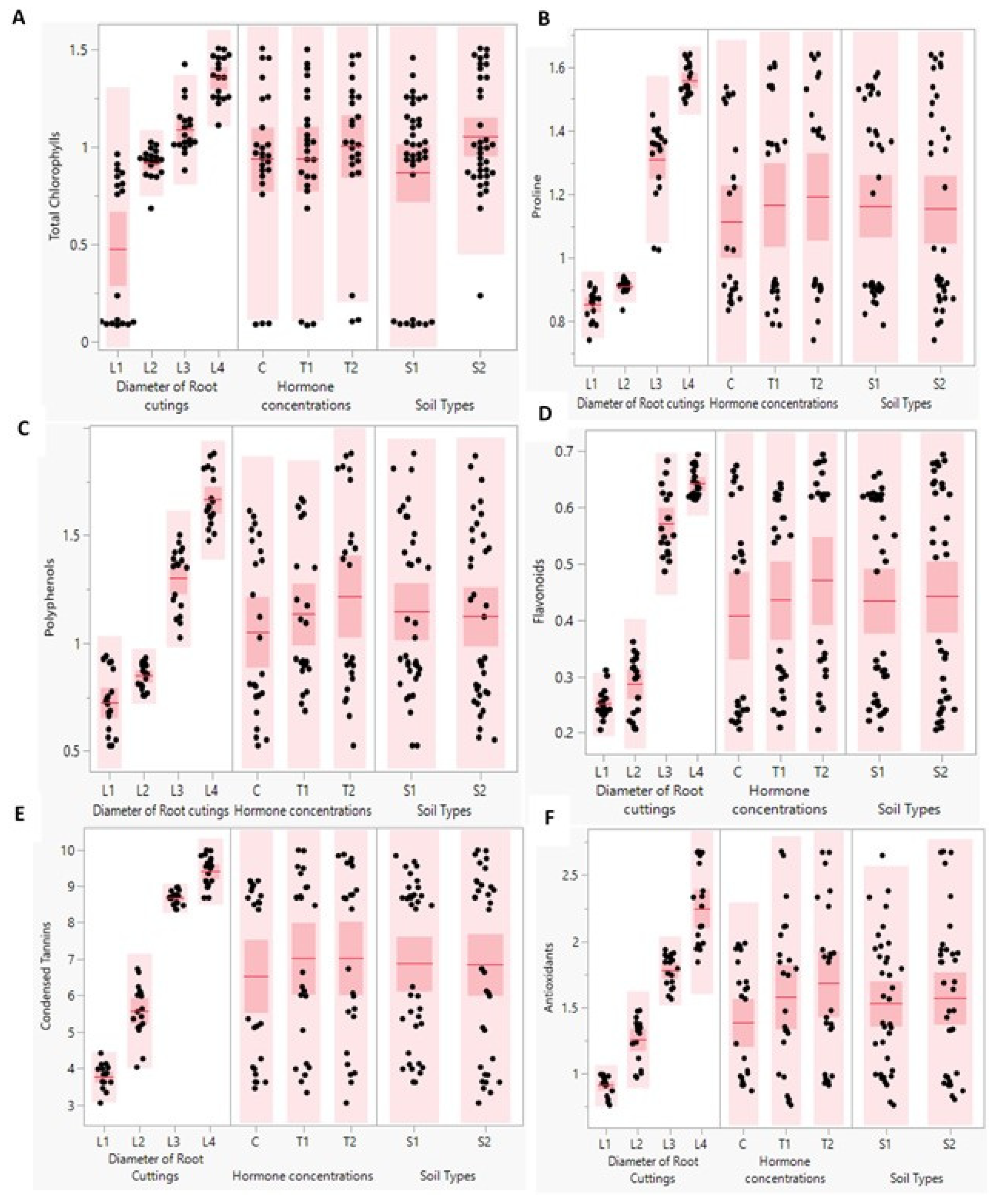

In this investigation, data showed that compared to hormone concentration and type of soil, the diameter of root cuttings was the major factor influencing the biochemical con-tents of the new 4 months-aged

P. tomentosa sprouts (

Table 1). As shown in scatter plots of some biochemical parameters (

Figure 8), the total chlorophyll content was mostly affected by the cuttings root diameter factor. The increase of cuttings root diameter was accompa-nied by an increase of photosynthetic pigments (total chlorophyll) content. Under control condition (without hormone treatment), the higher content (1.32 mg/mg FW) was observed in sprout treated by L4CS2 and L1CS1 (

Table 1). In another way, when cutting roots were treated with hormone concentration (T1), we found that the higher content of total chlo-rophyll was detected in L1T2S1 and L4T2S2 (1.25 mg/mg FW) followed by L3T2S2 (1.10 mg/mg FW), L2T1S2 (0.95 mg/mg FW) and L1T1S2 (0.09 mg/mg FW).

For proline (

Figure 8), the results showed that content of this osmoregulatory was widely affected by diameter of cutting and concentration of hormone used before start of our experiment. When the diameter of root cutting is larger than 0.8 cm (L3 and L4) pro-line is highly accumulated. In plus, the increase of hormone dose was accompanied by accumulation of proline. More precisely, the proline content varied from 1.63l, 1.41 and 0.80 (nmol/g DW) were reported at L4T2S2, L3T2S2 and L1T2S2 sprouts, successively (

Table 1).

According to results presented in

Figure 8, there is a dramatic impact of roots cutting diameter on secondary metabolites contents in new sprouts of

P. tomentosa. Flavonoids represent the most numerous groups of secondary metabolites isolated from

P. tomentosa . The results remarked that total polyphenols, total flavonoids and condensed tannins con-tents were augmented by increase of root cuttings diameters used to propagate P. tomentosa. Also, the rise of cutting roots diameter resulted in elevation of all these measured com-pounds. In contrast, soil type had no effect on previously described contents. Based on values presented in

Table 1, we found that the total polyphenol compounds contents were detected as follows 1.82, 1.44 and 0.57 (mg eq AG/g DW), respectively in sprout treated by L4T1S2, L3T2S2 and L1CS2 (

Table 1). These same sprouts total flavonoids contents were scored as 0.68, 0.65 and 0.24 (mg eq QU/g DW), respectively. Moreover,

Table 1 showed that the condensed tannins contents reached to 9.81, 8.78 and 3.50 (mg eq Catechol/g DW) in L4T1S2, L3T2S2, L3T1S2 and L1T2S2 sprouts, respectively.

Antioxidative activity enhanced in the different new sprouts was dramatically affected by root cutting diameters and the concentration of hormone (

Figure 8). The results recorded in

Table 1 showed that antioxidative activity decreased by reducing the diame-ter of cutting to reach values of 2.65, 1.87 and 0.84 (mg EAG/g DW) in L4T2S2; L3T2S2 and L1T1S1, respectively.

Three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of some biochemical factors were per-formed as the dependent variables separately for each model (diameter of root cuttings, hormone concentrations of Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA) and soil types and their interac-tive effects (

Table 2). Levene's test of equality showed a strong significance (P ≤ 0.001) in all parameters except flavonoids (P ≤ 0.01). For F statistics, the diameter of root cuttings vari-able was strongly significant (P ≤ 0.001) in all the measured biochemical estimates, whereas the soil type variable was not significant in all parameters. However, the hor-mone concentrations variable was strongly significant (P ≤ 0.001) in all compared param-eters except total chlorophyll.

According to the interactive factors, diameter of cuttings with hormone concentra-tions were at the same line with effect the hormone alone. While the diameter of cuttings with soil type interactive effect was strong significant (P ≤ 0.001) for total chlorophyll and proline, moderate significance (P ≤ 0.01) for flavonoids and the condensed tannins and finally not significant effect on polyphenol and antioxidant activities. In addition, the in-teractive effect of hormone concentration with soil type variables was not significant in all studied parameters except proline (P ≤ 0.05). Lastly, the interactive three factors effect was very strong significance (P ≤ 0.001) for proline, moderate significance (P ≤ 0.01) for tannins and not significant for chlorophyll, polyphenol and antioxidant parameters.

Independently of our experimental parameters (cutting diameter, hormone concen-tration and soil type), all P. tomentosa leaves are rich in secondary metabolites. Schnei-derova´ and Smejkal [

54] demonstrated similar richness in biologically active molecules. However, the dramatic reality is that the sprouts grown on S2 soil type and derived from treated cutting by hormone presented the major sources of secondary metabolites and pro-line. It is well demonstrated that flavonoids constitute the most numerous groups of sec-ondary metabolites in P. tomentosa leaves [

54]. This distinction in containing such phenol-ic compounds, explain the biological activity (antioxidant) detected in P. tomentosa [

55,

56,

57]. Precisely, antiradical activity in anti-DPPH assay was detected in the varied leaves samples, independently of the studied parameters.

3.3. IBA-derived auxin drives aspects of P. tomentosa root development

Indole 3-butyric acid (IBA) is a key phytohormone necessary for multiple plant growth and developmental processes, especially for organogenesis, various plant metabo-lism and environmental responses [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. Indole 3-butyric acid (IBA) is a type of auxin precursor which can convert to indole 3-acetic acid (IAA) by a peroxisomal β-oxidation process [

63]. IBA and IAA are structurally similar except the side chain for both hormones; the IBA has a four-carbon side chain while the IAA has two carbons. Un-like, the IAA which has ability to binds to the TIR1/AFB-Aux/IAA (TRANSPORT INHIBI-TOR RESPONSE 1/AUXIN SIGNALING F-BOX PROTEIN-Auxin/INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID) for initiated the downstream auxin-responsive gene expression, while the IBA is unable to bind and formation the auxin co-receptor complex because of its lengthened side chain [

64,

65].

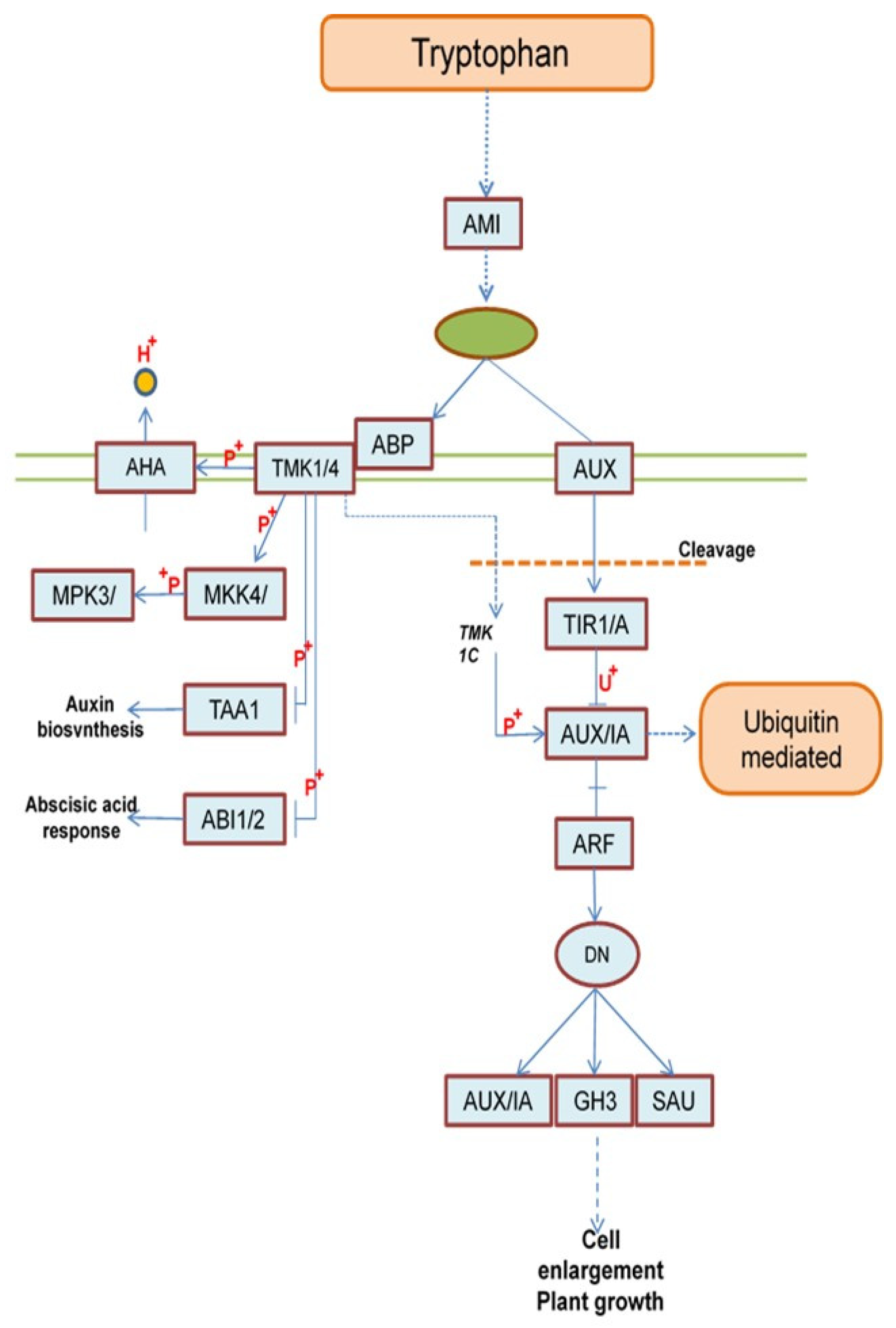

Auxin is biologically synthesized through two sub-pathways starting from Trypto-phan. The first sub-pathway starting from the following genes; AMI1 (KEGG; K01426), then LAX3 (KEGG; K13946), AFB3 (KEGG; K27740), ARF19 (KEGG; K14486), IAA10 (KEGG; K14484), GH3 (KEGG; K14487) and SAUR (KEGG; K14488), which encoding to amidase, auxin influx carrier (AUX1 LAX family), protein auxin signaling F-box 2/3, auxin response factor, auxin-responsive protein IAA, auxin responsive GH3 gene family and SAUR family protein, respectively, see

Figure 9. At the end of the first sub-pathway the last three genes (IAA10, GH3 and SAUR) were effect on the cell DNA molecule, which leads to cell control through cell enlargement or/and plant growth as shown in

Figure 9 and (

https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/ath04075, accessed on 21 April 2025).

While, the second sub-pathway starting from the following genes; ABP1 (KEGG; K27415), TMK (KEGG; K00924), AHA10 (KEGG; K01535), MKK4 (KEGG; K13413), MPK6 (KEGG; K14512), TAR1 (KEGG; K16903) and HAI2 (KEGG; K14497), which encoding to auxin-binding protein, receptor protein kinase TMK, H+-transporting ATPase, mito-gen-activated protein kinase 4/5, mitogen-activated protein kinase 6, L-tryptophan--pyruvate aminotransferase and protein phosphatase 2C, respectively, (

Figure 9). Also, at the end of this second sub-pathway the last two genes are related with the auxin biosynthesis and abscisic acid response (see

Figure 9 and

https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/ath04075 , accessed on 21 April 2025).

In the context, based on the statistical components accompanied by biochemical and morphological data, the previous data showed the effect of different concentrations of In-dole 3-Butyric Acid on the various in morphological and chemical data individual or in combination with other factors such as the soil type and the root cutting diameter. Which mean that the behavior and effect of the IBA hormone that the behavior was not the dom-inant factor for improve the morphological traits (e.g, stem height and leave numbers) and various biochemical compounds (e.g, total chlorophyll, proline, total polyphenol com-pounds, total flavonoids, condensed tannins and antioxidant activity), but the soil type and root cutting diameter can produce comparable results as well. These results are in line with Sevik and Guney [

66] and Korasick et al. [

67] who found the IBA was used as a suit-able hormone for many biological process (e.g, stem bending, rooting of stem cuttings, leaf epinasty, root initiation, root generation and elongation) in various plants such as; Lemon balm, sunflower, tomato, pea, buckwheat, tobacco, bean, Arabidopsis, and potato and across species.

On the other hand, many scientists have pointed out in their studies that the success of propagation plant from stem or root cutting are largely depends on the capacity of ex-plant to form adventitious roots (AR), which controlled by the type and concentration of the endogenous or/and exogenous hormones from side and from the other side the inter-action between the endogenous or exogenous and various metabolic compounds path-ways [

68,

69,

70]. Furthermore, the effects of different types of auxins, especially the IBA through interaction with various metabolic compounds in adventitious root formation, lateral root initiation, root elongation, root gravity response, various plant tissue develop-ment and plant growth have been reported in several studies. In addition, Sevik and Guney [

71] studied the relationship between the level of IBA and the accumulation of flavones and flavanols in various tissues from two Melissa officinalis L genotypes and their roles in rooting formation on stem cuttings. Also, Uğur Tan [

72] analyzed the effectiveness of IBA for enhancing the Chlorophyll content, phenol content, flavonoid content and an-tioxidant traits of Salvia fruticosa cuttings for mitigating the adverse effects of salinity stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.N. and Y.A.; Methodology, A.H.N. and Y.A.; Software, A.H.N. and Y.M.H.; Validation, A.H.N., Y.M.H., M.A. and Y.A; Formal Analysis, A.H.N. and Y.M.H.; Investigation, A.H.N., Y.M.H. and Y.A. Resources, Y.A.; Data Curation, A.H.N., Y.M.H., M.A.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, A.H.N., Y.M.H. and M.A.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.H.N., Y.M.H., M.A., C.A. and Y.A.; Visualization, A.H.N. and Y.A.; Supervision, A.H.N., Y.M.H. and Y.A.; Project Administration, A.H.N. and Y.A.; Funding Acquisition, Y.A.” All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

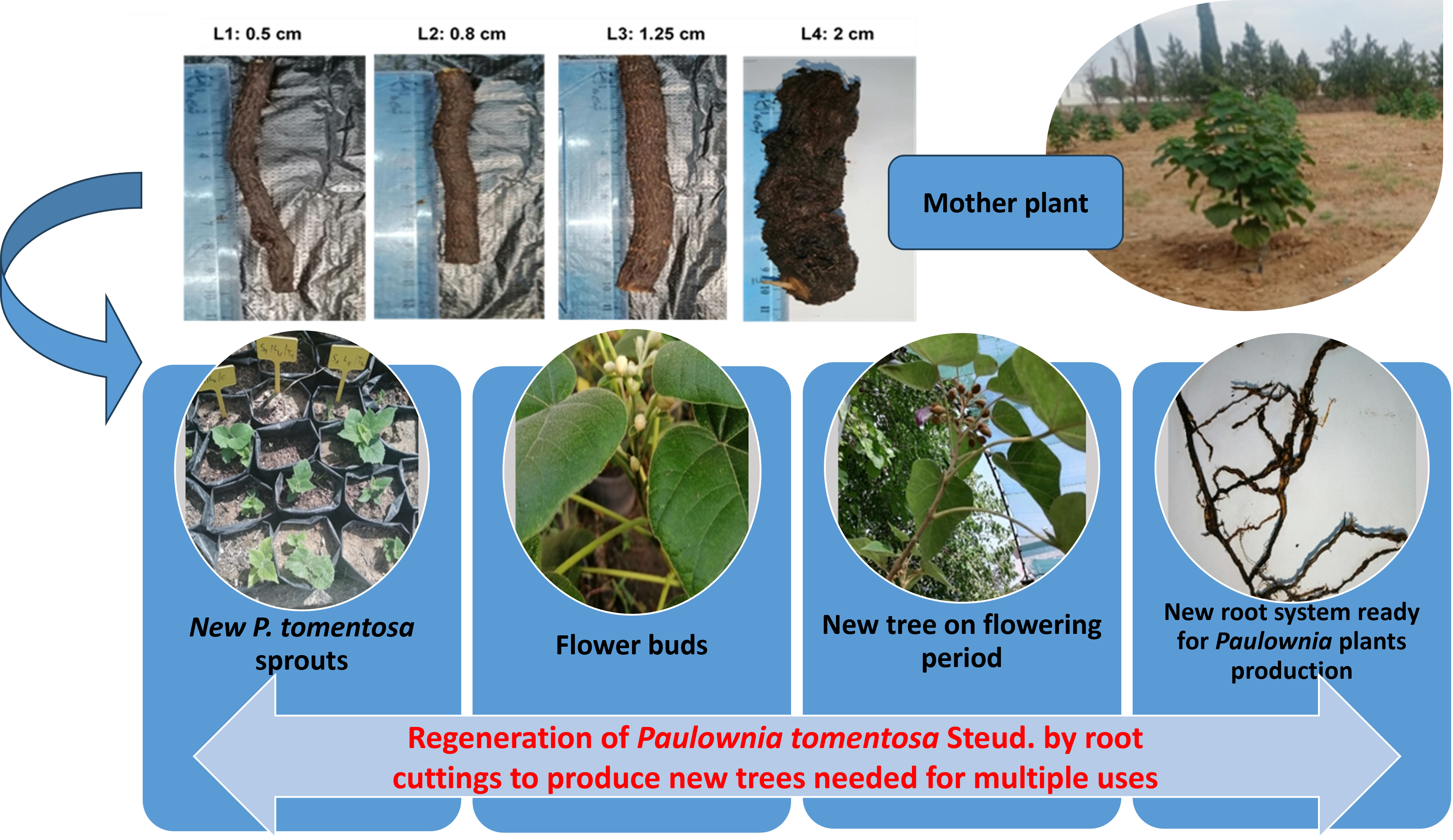

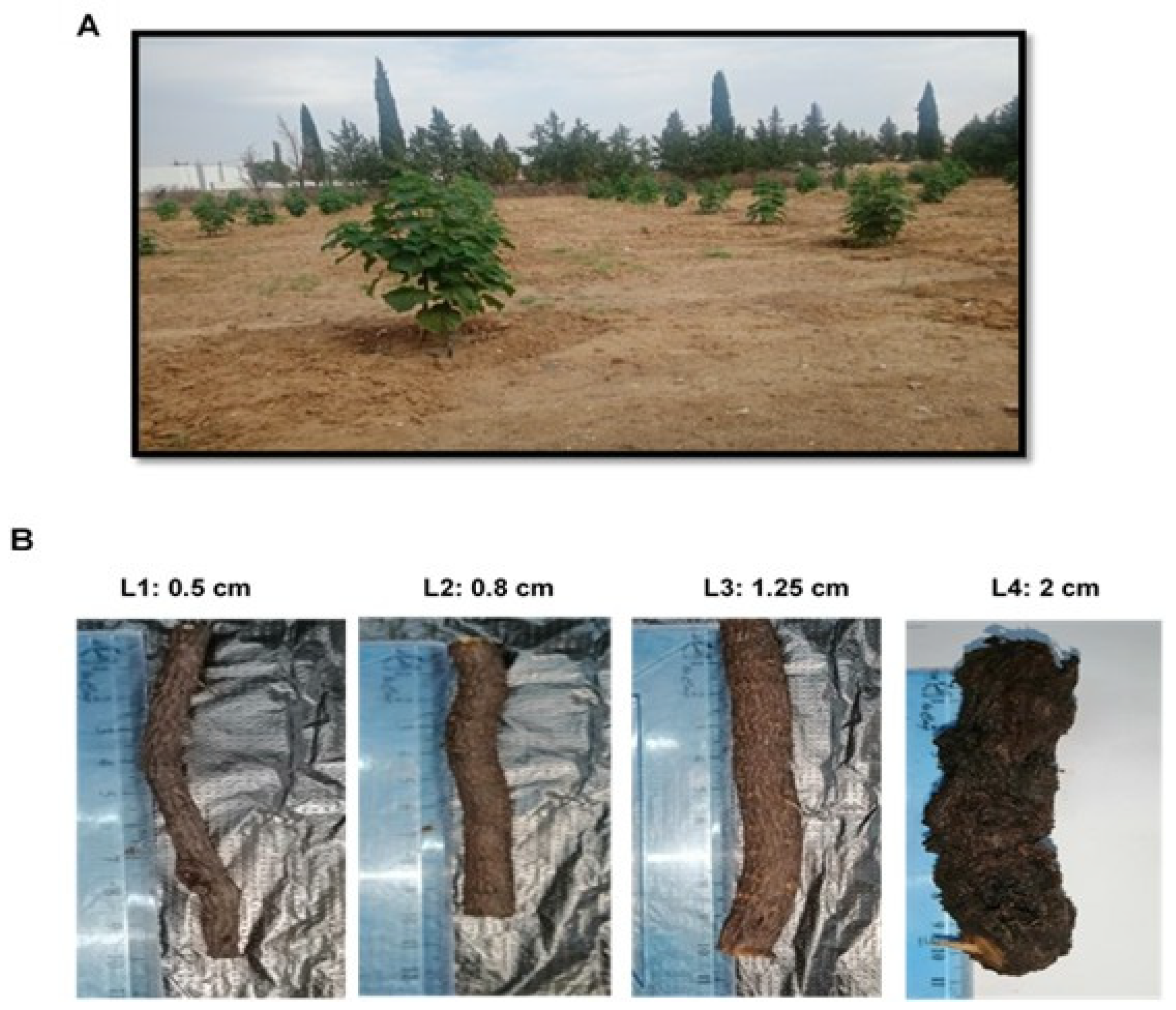

Figure 1.

(A-B) Photographs of parcel of the original mother P. tomentosa trees at the plantation site (Kef Higher School of Agriculture) (ESAK), Tunisia in October 2021 (A) and the 10 cm of root cutting diameters (L1, 0.5; L2, 0.8, L3, 1.25 and L4, 2 cm) (B).

Figure 1.

(A-B) Photographs of parcel of the original mother P. tomentosa trees at the plantation site (Kef Higher School of Agriculture) (ESAK), Tunisia in October 2021 (A) and the 10 cm of root cutting diameters (L1, 0.5; L2, 0.8, L3, 1.25 and L4, 2 cm) (B).

Figure 2.

(A-C) Dynamics of first-year morphological measures of stem height of P. tomen-tosa sprouts against: Soil types (S1, 50% silt +50% potting soil and S2: 43% potting soil + 43% silt + 14% sandy soil) ( A), Diameter of root cuttings (L1, 0.5; L2, 0.8, L3, 1.25 and L4, 2cm) (B), and Hormone (Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA)) concentrations (C, 0; T1, 0.1% and T2, 0.3%) (C) which measured every week from May to October 2022. Data represents as means and error bars.

Figure 2.

(A-C) Dynamics of first-year morphological measures of stem height of P. tomen-tosa sprouts against: Soil types (S1, 50% silt +50% potting soil and S2: 43% potting soil + 43% silt + 14% sandy soil) ( A), Diameter of root cuttings (L1, 0.5; L2, 0.8, L3, 1.25 and L4, 2cm) (B), and Hormone (Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA)) concentrations (C, 0; T1, 0.1% and T2, 0.3%) (C) which measured every week from May to October 2022. Data represents as means and error bars.

Figure 3.

(A-C) Dynamics of first-year morphological measures of leaves number of P. to-mentosa sprouts against soil type (S1, 50% silt +50% potting soil and S2: 43% potting soil + 43% silt + 14% sandy soil) (A), diameter of root cuttings ((L1, 0.5; L2, 0.8, L3, 1.25 and L4, 2cm), (B) and hormone (Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA)) concentrations (C, 0; T1, 0.1% and T2, 0.3%) (C) which measured every week from May to October 2022. Data represents as means and error bars.

Figure 3.

(A-C) Dynamics of first-year morphological measures of leaves number of P. to-mentosa sprouts against soil type (S1, 50% silt +50% potting soil and S2: 43% potting soil + 43% silt + 14% sandy soil) (A), diameter of root cuttings ((L1, 0.5; L2, 0.8, L3, 1.25 and L4, 2cm), (B) and hormone (Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA)) concentrations (C, 0; T1, 0.1% and T2, 0.3%) (C) which measured every week from May to October 2022. Data represents as means and error bars.

Figure 4.

(A-B) Measures of line of fit with F test of stem height of P. tomentosa which were taken out every year in October (2023/ 2024) under the interactive effect of the studied treat-ments. Under S1 soil type (A) and S2 soil type (B). Black point indicates to mean with standard error and F statistics with the two degrees of freedoms and P value.

Figure 4.

(A-B) Measures of line of fit with F test of stem height of P. tomentosa which were taken out every year in October (2023/ 2024) under the interactive effect of the studied treat-ments. Under S1 soil type (A) and S2 soil type (B). Black point indicates to mean with standard error and F statistics with the two degrees of freedoms and P value.

Figure 5.

(A-B) Measures of leaves number of P. tomentosa which were taken out every year in October (2023/ 2024) under S1 soil type (A) and under S2 soil type (B). Black point indicates to mean with standard error and F statistics with the two degrees of freedoms and P value.

Figure 5.

(A-B) Measures of leaves number of P. tomentosa which were taken out every year in October (2023/ 2024) under S1 soil type (A) and under S2 soil type (B). Black point indicates to mean with standard error and F statistics with the two degrees of freedoms and P value.

Figure 6.

(A-C) Monitoring of flower bud’s emergence and maturing at flowering stage under different interactive treatments effects over successive years in December 2022 (A); in De-cember 2023 (B) and in October 2024 (C).

Figure 6.

(A-C) Monitoring of flower bud’s emergence and maturing at flowering stage under different interactive treatments effects over successive years in December 2022 (A); in De-cember 2023 (B) and in October 2024 (C).

Figure 7.

Phenological (adult individuals) of flower buds and flowers numbers of P. tomentosa under different interactive treatments effects every year during (2022/2024).

Figure 7.

Phenological (adult individuals) of flower buds and flowers numbers of P. tomentosa under different interactive treatments effects every year during (2022/2024).

Figure 8.

(A-F) Scatter plots of some of biochemical parameters. Total chlorophyll (mg/g FW) (A), Proline (nmol/g DW) (B), Polyphenols (mg eq AG/g DW) (C), Flavonoids (mg eq QU/g DW) (D), Condensed tannins (mg eq Catechol/g DW)(E), and Antioxidants (mg EAG/g DW) (F) of P. tomentosa grown under different three factors (Diameter of root cuttings (L1, 0.5; L2, 0.8, L3, 1.25 and L4, 2 cm), Hormone concentrations of Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA) (C, 0; T1, 0.1% and T2, 0.3%) and soil types (S1, 50% silt +50% potting soil and S2: 43% potting soil + 43%silt + 14% sandy soil).

Figure 8.

(A-F) Scatter plots of some of biochemical parameters. Total chlorophyll (mg/g FW) (A), Proline (nmol/g DW) (B), Polyphenols (mg eq AG/g DW) (C), Flavonoids (mg eq QU/g DW) (D), Condensed tannins (mg eq Catechol/g DW)(E), and Antioxidants (mg EAG/g DW) (F) of P. tomentosa grown under different three factors (Diameter of root cuttings (L1, 0.5; L2, 0.8, L3, 1.25 and L4, 2 cm), Hormone concentrations of Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA) (C, 0; T1, 0.1% and T2, 0.3%) and soil types (S1, 50% silt +50% potting soil and S2: 43% potting soil + 43%silt + 14% sandy soil).

Figure 9.

Overview of Auxin metabolism pathways. AMI1 (amidase), LAX3 (auxin influx carrier (AUX1 LAX family)), AFB3 (protein auxin signaling F-box 2/3), ARF19 (auxin response factor), IAA10 (auxin-responsive protein IAA), GH3 (auxin responsive GH3 gene family), SAUR (SAUR family protein), ABP1 ( auxin-binding protein), TMK (receptor protein kinase TMK), AHA10 (H+-transporting ATPase), MKK4 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 4/5), MPK6 (mito-gen-activated protein kinase 6), TAR1 (L-tryptophan--pyruvate aminotransferase) and HAI2 (protein phosphatase 2C).

Figure 9.

Overview of Auxin metabolism pathways. AMI1 (amidase), LAX3 (auxin influx carrier (AUX1 LAX family)), AFB3 (protein auxin signaling F-box 2/3), ARF19 (auxin response factor), IAA10 (auxin-responsive protein IAA), GH3 (auxin responsive GH3 gene family), SAUR (SAUR family protein), ABP1 ( auxin-binding protein), TMK (receptor protein kinase TMK), AHA10 (H+-transporting ATPase), MKK4 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 4/5), MPK6 (mito-gen-activated protein kinase 6), TAR1 (L-tryptophan--pyruvate aminotransferase) and HAI2 (protein phosphatase 2C).

Table 1.

Mean ± standard deviation of some biochemical parameters under the effect of three estimated variables.

Table 1.

Mean ± standard deviation of some biochemical parameters under the effect of three estimated variables.

| Treatments |

Total Chlorophyll

content |

Proline

content |

Total Polyphenol compounds content |

Total Flavonoids content |

Condensed Tannins content |

Antioxidant activity |

| Diameter of root cutting |

Hormone concentration |

Soil type |

| L1 |

C |

S1 |

1.32±0.12 |

0.87±0.01 |

0.65±0.12 |

0.25±0.01 |

3.75±0.21 |

0.94±0.03 |

| S2 |

0.09±0.00 |

0.87±0.01 |

0.57±0.03 |

0.24±0.02 |

3.64±0.19 |

0.90±0.03 |

| T1 |

S1 |

1.24±0.13 |

0.84±0.05 |

0.91±0.02 |

0.26±0.04 |

4.05±0.08 |

0.84±0.13 |

| S2 |

0.09±0.01 |

0.83±0.04 |

0.73±0.04 |

0.26±0.02 |

3.60±0.24 |

0.87±0.09 |

| T2 |

S1 |

1.25±0.03 |

0.91±0.01 |

0.74±0.21 |

0.28±0.03 |

4.14±0.27 |

0.98±0.01 |

| S2 |

0.39±0.49 |

0.80±0.06 |

0.77±0.13 |

0.23±0.02 |

3.50±0.40 |

0.92±0.01 |

| L2 |

C |

S1 |

0.94±0.03 |

0.91±0.01 |

0.81±0.05 |

0.22±0.02 |

5.25±0.10 |

1.12±0.10 |

| S2 |

0.94±0.03 |

0.90±0.06 |

0.79±0.02 |

0.24±0.02 |

4.47±0.57 |

0.98±0.02 |

| T1 |

S1 |

0.95±0.03 |

0.91±0.01 |

0.90±0.02 |

0.31±0.00 |

6.08±0.14 |

1.30±0.06 |

| S2 |

0.95±0.03 |

0.92±0.01 |

0.86±0.09 |

0.28±0.07 |

5.94±0.81 |

1.37±0.08 |

| T2 |

S1 |

0.91±0.05 |

0.91±0.01 |

0.88±0.04 |

0.32±0.02 |

5.54±0.11 |

1.37±0.02 |

| S2 |

0.91±0.05 |

0.91±0.02 |

0.86±0.07 |

0.34±0.01 |

6.26±0.41 |

1.41±0.07 |

| L3 |

C |

S1 |

0.09±0.00 |

1.27±0.07 |

1.26±0.20 |

0.50±0.02 |

8.60±0.12 |

1.60±0.04 |

| S2 |

1.04±0.05 |

1.09±0.11 |

1.26±0.16 |

0.52±0.01 |

8.59±0.26 |

1.67±0.03 |

| T1 |

S1 |

0.09±0.01 |

1.36±0.01 |

1.18±0.14 |

0.56±0.02 |

8.72±0.25 |

1.76±0.03 |

| S2 |

1.08±0.06 |

1.34±0.02 |

1.24±0.10 |

0.56±0.02 |

8.78±0.17 |

1.87±0.03 |

| T2 |

S1 |

0.39±0.49 |

1.40±0.01 |

1.42±0.05 |

0.63±0.02 |

8.59±0.20 |

1.87±0.02 |

| S2 |

1.10±0.07 |

1.41±0.04 |

1.44±0.06 |

0.65±0.03 |

8.78±0.11 |

1.92±0.02 |

| L4 |

C |

S1 |

1.04±0.05 |

1.51±0.01 |

1.57±0.06 |

0.64±0.02 |

8.93±0.24 |

1.96±0.02 |

| S2 |

1.32±0.12 |

1.51±0.03 |

1.52±0.04 |

0.66±0.01 |

9.09±0.06 |

1.92±0.07 |

| T1 |

S1 |

1.08±0.06 |

1.54±0.00 |

1.63±0.04 |

0.62±0.00 |

9.18±0.45 |

2.27±0.33 |

| S2 |

1.24±0.13 |

1.60±0.01 |

1.63±0.03 |

0.63±0.01 |

9.81±0.28 |

2.38±0.28 |

| T2 |

S1 |

1.10±0.07 |

1.56±0.03 |

1.83±0.04 |

0.62±0.00 |

9.68±0.14 |

2.33±0.06 |

| S2 |

1.25±0.03 |

1.63±0.01 |

1.82±0.06 |

0.68±0.01 |

9.75±0.12 |

2.65±0.05 |

Table 2.

Three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) depicting some biochemical fac-tors as the dependent variables separately for each model (Diameter of root cuttings, Hormone concentrations of Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA) and soil types and their interac-tive effects.

Table 2.

Three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) depicting some biochemical fac-tors as the dependent variables separately for each model (Diameter of root cuttings, Hormone concentrations of Indole -3-Butiric- Acid (IBA) and soil types and their interac-tive effects.

| Source of variation/ Variables |

Total

Chlorophyll content |

Proline content |

Total Polyphenols compounds content |

Total Flavonoids content |

Condensed Tannins content |

Antioxidant activity |

| Corrected Model |

22.321*** |

198.42*** |

53.77*** |

172.83*** |

185.17*** |

82.35*** |

| Intercept |

2235.753*** |

69405.89*** |

10736.15*** |

24824.89*** |

37422.47*** |

15910.49*** |

| Diameter of root cuttings |

42.488*** |

1456.07*** |

387.87*** |

1264.04*** |

1383.43*** |

575.43*** |

| Hormone concentrations |

1.696 ns |

26.79*** |

19.00*** |

41.19*** |

20.81*** |

49.38*** |

| Soil types |

0.000 ns |

1.49 ns |

1.17 ns |

1.84 ns |

0.11 ns |

3.09 ns |

| Diameter * Hormone concentrations |

0.861 ns |

14.23*** |

4.42*** |

12.52 *** |

5.03*** |

7.69*** |

| Diameter * Soil type |

123.139*** |

6.86*** |

0.95 ns |

4.02** |

4.09** |

2.07 ns |

| Hormone concentrations * Soil type |

0.000 ns |

3.91* |

0.47 ns |

1.04 ns |

1.29 ns |

2.76 ns |

| Diameter * Hormone concentration * Soil type |

1.325 ns |

4.45*** |

0.60 ns |

1.57 ns |

3.63** |

1.35 ns |

Levene Statistic

(based on mean)

|

10.12*** |

4.81*** |

2.95*** |

2.63** |

3.11*** |

5.64*** |