Submitted:

02 May 2024

Posted:

06 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Participants

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Extraction of Metabolites and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

2.4. Extraction of Metabolites and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

2.5. Additional Software Applications

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Information

3.2. Altered Serum Metabolites and Functional Pathways Identified in Patients with FD through Multivariate Statistical Analysis

3.3. Analysis of Key Differentially Abundant Serum Metabolites and Model Prediction in Patients with FD

3.4. Altered Urine Metabolites and Functional Pathways Identified in Patients with FD through Multivariate Statistical Analysis

3.5. Analysis of Key Differentially Abundant Urine Metabolites and Model Prediction in Patients with FD

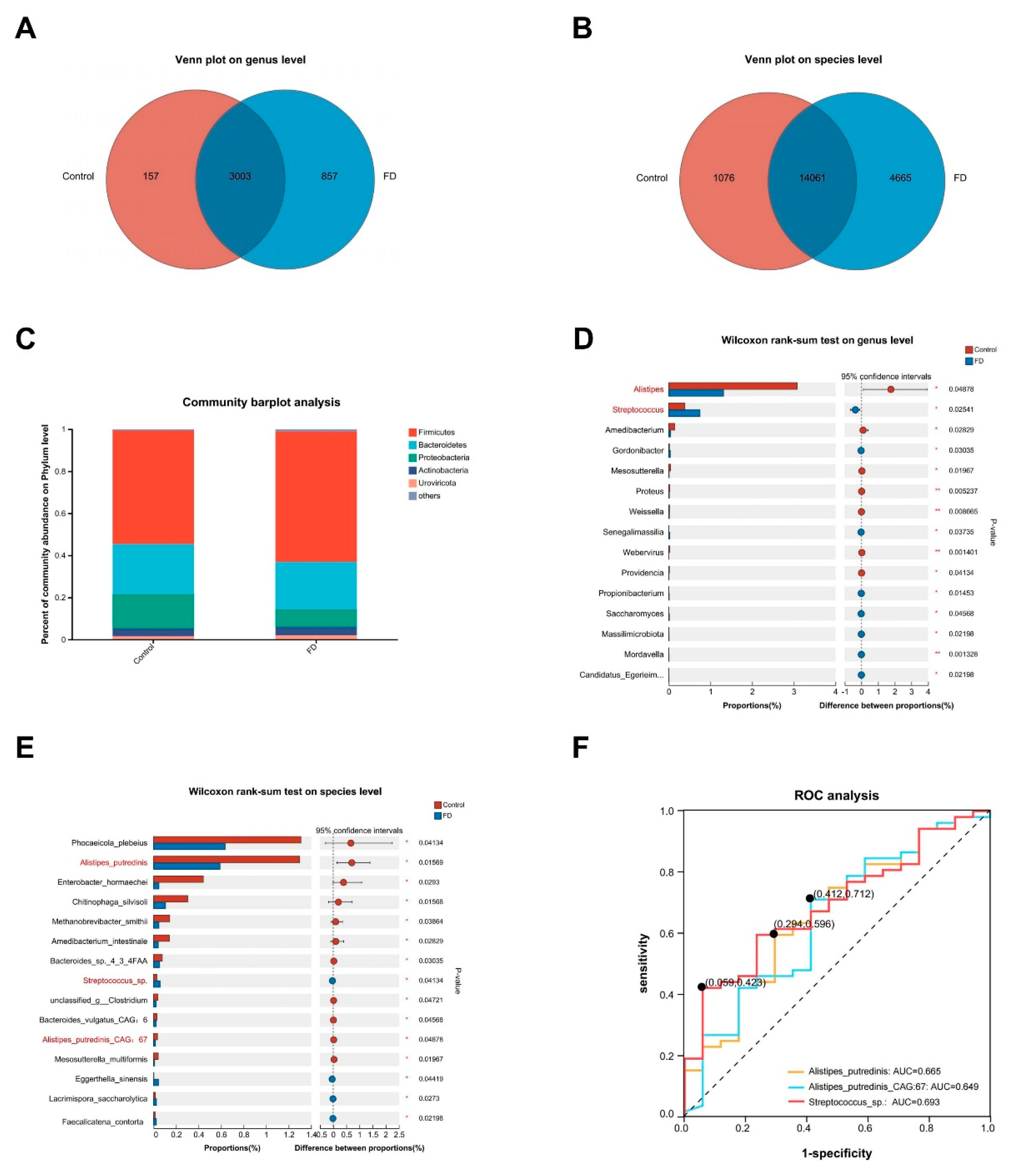

3.6. Alterations in the Microbial Community Structure Specific to FD Identified through Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

3.7. Alterations in the Microbial Community Structure Specific to FD Identified through Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

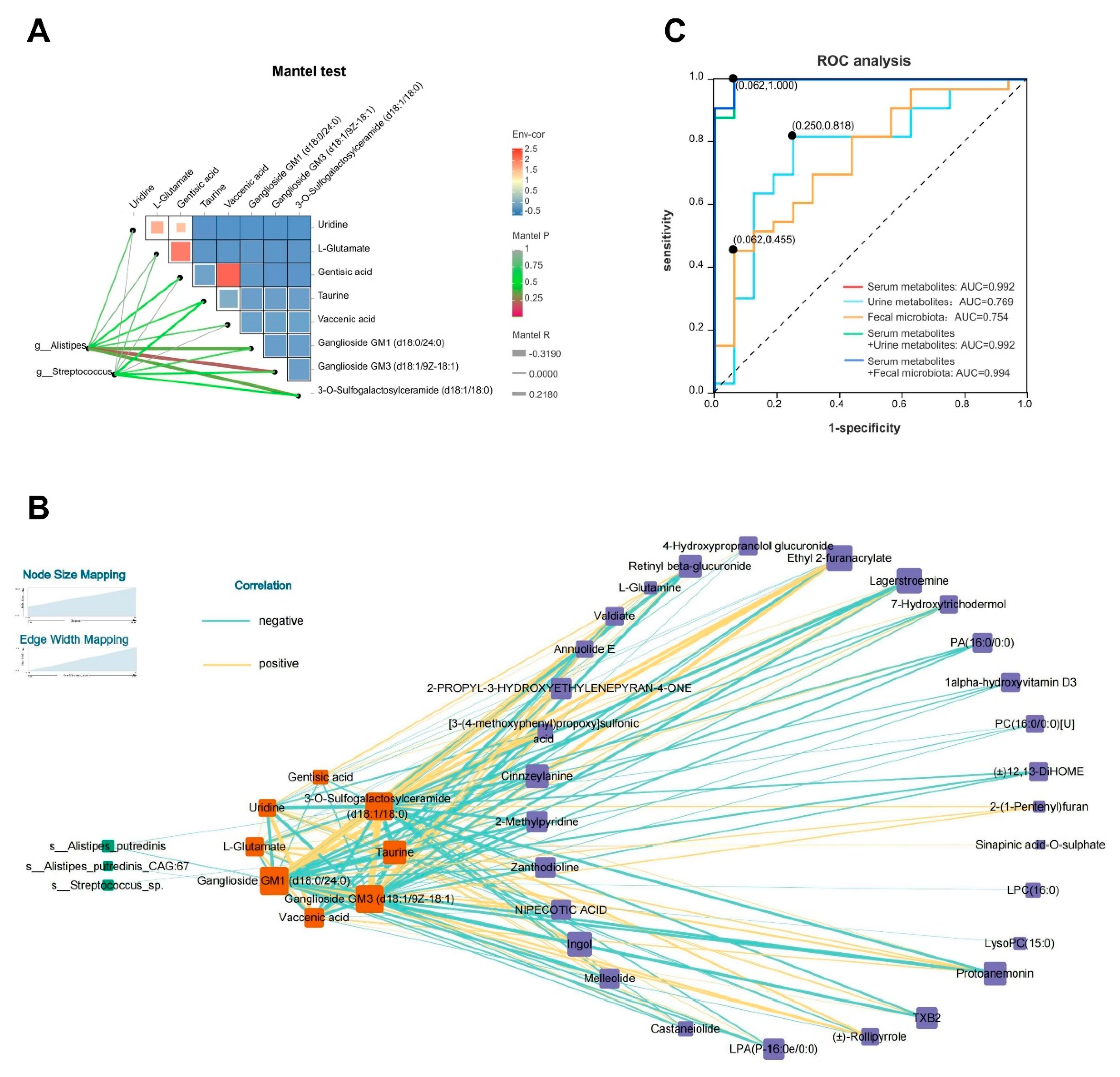

3.8. Construction of a Multifactorial Correlation Network and Joint Diagnostic Value of Blood and Urine Metabolomics with Fecal Macrogenomics in Patients with FD

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Enck, P.; Azpiroz, F.; Boeckxstaens, G.; Elsenbruch, S.; Feinle-Bisset, C.; Holtmann, G.; Lackner, J.M.; Ronkainen, J.; Schemann, M.; Stengel, A.; et al. Functional dyspepsia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Hao, J.; Li, B.; Huo, Y.; Han, Y.; Wan, L.; Li, J.; Huang, J.; Lu, J.; et al. Serum and urine metabolomics study reveals a distinct diagnostic model for cancer cachexia. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2018, 9, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Geng, W.; Sun, H.; Liu, C.; Huang, F.; Cao, J.; Xia, L.; Zhao, H.; Zhai, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Integrative metabolomic characterisation identifies altered portal vein serum metabolome contributing to human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2022, 71, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psychogios, N.; Hau, D.D.; Peng, J.; Guo, A.C.; Mandal, R.; Bouatra, S.; Sinelnikov, I.; Krishnamurthy, R.; Eisner, R.; Gautam, B.; et al. The human serum metabolome. Plos One 2011, 6, e16957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Xie, J.; Zhang, M.; Ma, J.; Wang, F.; Tang, X. Combination of 15 lipid metabolites and motilin to diagnose spleen-deficiency FD. Chin. Med. 2019, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.; Fauman, E.B.; Petersen, A.; Krumsiek, J.; Santos, R.; Huang, J.; Arnold, M.; Erte, I.; Forgetta, V.; Yang, T.; et al. An atlas of genetic influences on human blood metabolites. Nature Genet. 2014, 46, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, T.; Hicks, M.; Yu, H.; Biggs, W.H.; Kirkness, E.F.; Menni, C.; Zierer, J.; Small, K.S.; Mangino, M.; Messier, H.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies common-to-rare variants associated with human blood metabolites. Nature Genet. 2017, 49, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikoff, W.R.; Anfora, A.T.; Liu, J.; Schultz, P.G.; Lesley, S.A.; Peters, E.C.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 3698–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, N.; Korem, T.; Weissbrod, O.; Zeevi, D.; Rothschild, D.; Leviatan, S.; Kosower, N.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Weinberger, A.; Le Roy, C.I.; et al. A reference map of potential determinants for the human serum metabolome. Nature 2020, 588, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, E.R.; Kang, S.; Staudacher, H.; Shah, A.; Do, A.; Burns, G.; Chachay, V.S.; Koloski, N.A.; Keely, S.; Walker, M.M.; et al. Alterations to the duodenal microbiota are linked to gastric emptying and symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Gut 2023, 72, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; You, Y.; Peng, B.; Zhong, T.; Kuang, Y.; Li, S.; Du, L.; Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Dai, J.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals the metabolic regulators of duodenal low-grade inflammation in a functional dyspepsia model. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 944591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziatzios, G.; Gkolfakis, P.; Leite, G.; Mathur, R.; Damoraki, G.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Triantafyllou, K. Probiotics in Functional Dyspepsia. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceulemans, M.; Wauters, L.; Vanuytsel, T. Targeting the altered duodenal microenvironment in functional dyspepsia. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2023, 70, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, A.C.; Mahadeva, S.; Carbone, M.F.; Lacy, B.E.; Talley, N.J. Functional dyspepsia. Lancet (London, England) 2020, 396, 1689–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, P.; Talley, N.J.; Agréus, L.; Johansson, S.; Bolling-Sternevald, E.; Storskrubb, T.; Ronkainen, J. Functional dyspepsia impairs quality of life in the adult population - PubMed. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, O.; Goyal, P.; Kishore, H.; Kaur, J.; Kumar, P.; Sood, A. Quality of life in Indian patients with functional dyspepsia: Translation and validation of the Hindi version of Short-Form Nepean Dyspepsia Index. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology : Official Journal of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology 2022, 41, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hantoro, I.F.; Syam, A.F.; Mudjaddid, E.; Setiati, S.; Abdullah, M. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in patients with functional dyspepsia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Oudenhove, L.; Vandenberghe, J.; Vos, R.; Holvoet, L.; Demyttenaere, K.; Tack, J. Risk factors for impaired health-related quality of life in functional dyspepsia. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, I.; Palsson, O.S.; Törnblom, H.; Sperber, A.D.; Whitehead, W.E.; Simrén, M. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and associations for symptom-based Rome IV functional dyspepsia in adults in the USA, Canada, and the UK: a cross-sectional population-based study. The Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2018, 3, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapiero, H.; Mathé, G.; Couvreur, P.; Tew, K.D., II. Glutamine and glutamate. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie 2002, 56, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.H. Function of GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the stomach. J. Biomed. Sci. 2005, 12, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi-Shiraishi, I.; Shiraishi, S.; Fujita, S.; Ogawa, S.; Kaneko, M.; Suzuki, M.; Tanaka, T. L-Arginine L-Glutamate Enhances Gastric Motor Function in Rats and Dogs and Improves Delayed Gastric Emptying in Dogs. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2016, 359, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusano, M.; Zai, H.; Hosaka, H.; Shimoyama, Y.; Nagoshi, A.; Maeda, M.; Kawamura, O.; Mori, M. New frontiers in gut nutrient sensor research: monosodium L-glutamate added to a high-energy, high-protein liquid diet promotes gastric emptying: a possible therapy for patients with functional dyspepsia. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 112, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mano, F.; Ikeda, K.; Joo, E.; Yamane, S.; Harada, N.; Inagaki, N. Effects of three major amino acids found in Japanese broth on glucose metabolism and gastric emptying. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 2018, 46, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Gollapalli, K.; Mangiola, S.; Schranner, D.; Yusuf, M.A.; Chamoli, M.; Shi, S.L.; Lopes Bastos, B.; Nair, T.; Riermeier, A.; et al. Taurine deficiency as a driver of aging. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2023, 380, eabn9257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, M.; Tsukada, H.; Ooya, M.; Onomura, M.; Saito, T.; Fukuda, K.; Nakamura, H.; Taniguchi, T.; Tominaga, M.; Hosokawa, M.; et al. Gastric mucosal damage caused by monochloramine in the rat and protective effect of taurine: endoscopic observation through gastric fistula. Endoscopy 2000, 32, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeybek, A.; Ercan, F.; Cetinel, S.; Cikler, E.; Sağlam, B.; Sener, G. Taurine ameliorates water avoidance stress-induced degenerations of gastrointestinal tract and liver. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2006, 51, 1853–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sener, G.; Sehirli, O.; Cetinel, S.; Midillioğlu, S.; Gedik, N.; Ayanoğlu-Dülger, G. Protective effect of taurine against alendronate-induced gastric damage in rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 19, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.; Elidrissi, A.; Schuller-Levis, G.; Chadman, K.K. Taurine Partially Improves Abnormal Anxiety in Taurine-Deficient Mice. Adv.Exp.Med.Biol. 2019, 1155, 905–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Prajapati, S.K.; Krishnamurthy, S. Supplementation of taurine improves ionic homeostasis and mitochondrial function in the rats exhibiting post-traumatic stress disorder-like symptoms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 908, 174361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.G.; Kim, S. Taurine induces anti-anxiety by activating strychnine-sensitive glycine receptor in vivo. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism 2007, 51, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuelsson, M.; Gerdin, G.; Ollinger, K.; Vrethem, M. Taurine and glutathione levels in plasma before and after ECT treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 198, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, R.; Fan, Z.; Luo, D.; Cai, G.; Li, X.; Han, J.; Zhuo, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Taurine Alleviates Chronic Social Defeat Stress-Induced Depression by Protecting Cortical Neurons from Dendritic Spine Loss. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Ren, S.; Tang, R.; Xu, C.; Zhou, J.; Lin, S.; Feng, Y.; Yang, Q.; Hu, J.; Yang, J. Antidepressant effect of taurine in chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depressive rats. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedi, F.; Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. A review on gentisic acid as a plant derived phenolic acid and metabolite of aspirin: Comprehensive pharmacology, toxicology, and some pharmaceutical aspects. Phytotherapy Research : Ptr 2020, 34, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altinoz, M.A.; Ozpinar, A. Acetylsalicylic acid and its metabolite gentisic acid may act as adjunctive agents in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Behav. Pharmacol. 2019, 30, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Meng, H.; Liu, T.; Feng, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H. Blueberry Phenolics Reduce Gastrointestinal Infection of Patients with Cerebral Venous Thrombosis by Improving Depressant-Induced Autoimmune Disorder via miR-155-Mediated Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlezon, W.A.J.; Mague, S.D.; Parow, A.M.; Stoll, A.L.; Cohen, B.M.; Renshaw, P.F. Antidepressant-like effects of uridine and omega-3 fatty acids are potentiated by combined treatment in rats. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, D.G.; Sung, Y.; Hellem, T.L.; Delmastro, K.K.; Jeong, E.; Kim, N.; Shi, X.; Renshaw, P.F. Open-label uridine for treatment of depressed adolescents with bipolar disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacome-Sosa, M.; Vacca, C.; Mangat, R.; Diane, A.; Nelson, R.C.; Reaney, M.J.; Shen, J.; Curtis, J.M.; Vine, D.F.; Field, C.J.; et al. Vaccenic acid suppresses intestinal inflammation by increasing anandamide and related N-acylethanolamines in the JCR:LA-cp rat. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Ruth, M.R.; Goruk, S.D.; Reaney, M.J.; Glimm, D.R.; Vine, D.F.; Field, C.J.; Proctor, S.D. Trans-11 vaccenic acid dietary supplementation induces hypolipidemic effects in JCR:LA-cp rats. The Journal of Nutrition 2008, 138, 2117–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacome-Sosa, M.M.; Borthwick, F.; Mangat, R.; Uwiera, R.; Reaney, M.J.; Shen, J.; Quiroga, A.D.; Jacobs, R.L.; Lehner, R.; Proctor, S.D.; et al. Diets enriched in trans-11 vaccenic acid alleviate ectopic lipid accumulation in a rat model of NAFLD and metabolic syndrome. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2014, 25, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gupta, J.; Kerslake, M.; Rayat, G.; Proctor, S.D.; Chan, C.B. Trans-11 vaccenic acid improves insulin secretion in models of type 2 diabetes in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, T.; Mühlstein, A.; Yaghootfam, C.; Maksimenko, O.; Shipulo, E.; Gelperina, S.; Kreuter, J.; Gieselmann, V.; Matzner, U. Potential of surfactant-coated nanoparticles to improve brain delivery of arylsulfatase A. Journal of Controlled Release : Official Journal of the Controlled Release Society 2017, 253, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Terreni, M.; Sollogoub, M.; Zhang, Y. Ganglioside GM3 and Its Role in Cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 2933–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z. Ganglioside GM1 and the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, S.; Chan, M.; Marathe, G.K.; Parveen, F.; Chen, C.; Ke, L. An Updated Review of Lysophosphatidylcholine Metabolism in Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldyreva, L.V.; Morozova, M.V.; Saydakova, S.S.; Kozhevnikova, E.N. Fat of the Gut: Epithelial Phospholipids in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, V.; Baumann, A.; Brandt, A.; Wodak, M.F.; Staltner, R.; Bergheim, I. Oral Supplementation of Phosphatidylcholine Attenuates the Onset of a Diet-Induced Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis in Female C57BL/6J Mice. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 17, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauss, A.; Ehehalt, R.; Lehmann, W.; Erben, G.; Weiss, K.; Schaefer, Y.; Kloeters-Plachky, P.; Stiehl, A.; Stremmel, W.; Sauer, P.; et al. Biliary phosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylcholine profiles in sclerosing cholangitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 5454–5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaura, A.; Tanida, N.; Nishikawa, M.; Yamamoto, I.; Sawada, K.; Tsujiai, T.; Kang, K.B.; Izumi, K. Inhibitory effect of 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 on N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-induced gastrointestinal carcinogenesis in Wistar rats. Cancer Lett. 1998, 122, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iseki, K.; Tatsuta, M.; Uehara, H.; Iishi, H.; Yano, H.; Sakai, N.; Ishiguro, S. Inhibition of angiogenesis as a mechanism for inhibition by 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 of colon carcinogenesis induced by azoxymethane in Wistar rats. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 81, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, S.; Ozeki, J.; Makishima, M. Modulation of bile acid metabolism by 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 administration in mice. Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals 2009, 37, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macêdo, A.P.A.; Muñoz, V.R.; Cintra, D.E.; Pauli, J.R. 12,13-diHOME as a new therapeutic target for metabolic diseases. Life Sci. 2022, 290, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, C.M.; Lin, Y.; Chen, K.; Ke, H.; Huang, H.; Gong, Y.; Tsai, W.; You, J.; Lu, M.J.; Cheng, H.; et al. Predicting Clinical Outcomes of Cirrhosis Patients With Hepatic Encephalopathy From the Fecal Microbiome. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 8, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziarski, R.; Park, S.Y.; Kashyap, D.R.; Dowd, S.E.; Gupta, D. Pglyrp-Regulated Gut Microflora Prevotella falsenii, Parabacteroides distasonis and Bacteroides eggerthii Enhance and Alistipes finegoldii Attenuates Colitis in Mice. Plos One 2016, 11, e146162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.M.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria With Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strati, F.; Cavalieri, D.; Albanese, D.; De Felice, C.; Donati, C.; Hayek, J.; Jousson, O.; Leoncini, S.; Renzi, D.; Calabrò, A.; et al. New evidences on the altered gut microbiota in autism spectrum disorders. Microbiome 2017, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, M.E. Pathogenicity and virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Cutting to the chase on proteases. Virulence 2021, 12, 766–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hu, W.; Liu, W.; Zhao, L.; Huang, D.; Liu, X.; Chan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Coker, O.O.; et al. Streptococcus thermophilus Inhibits Colorectal Tumorigenesis Through Secreting β-Galactosidase. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1179–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, A.; Takagi, T.; Naito, Y.; Inoue, R.; Kashiwagi, S.; Mizushima, K.; Inada, Y.; Inoue, K.; Harusato, A.; Dohi, O.; et al. Higher Levels of Streptococcus in Upper Gastrointestinal Mucosa Associated with Symptoms in Patients with Functional Dyspepsia. Digestion 2020, 101, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Shanahan, E.R.; Raj, A.; Koloski, N.A.; Fletcher, L.; Morrison, M.; Walker, M.M.; Talley, N.J.; Holtmann, G. Dyspepsia and the microbiome: time to focus on the small intestine. Gut 2017, 66, 1168–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mars, R.A.T.; Yang, Y.; Ward, T.; Houtti, M.; Priya, S.; Lekatz, H.R.; Tang, X.; Sun, Z.; Kalari, K.R.; Korem, T.; et al. Longitudinal Multi-omics Reveals Subset-Specific Mechanisms Underlying Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Cell 2020, 182, 1460–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dar, M.A.; Arafah, A.; Bhat, K.A.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.S.; Ali, A.; Ahmad, S.M.; Rashid, S.M.; Rehman, M.U. Multiomics technologies: role in disease biomarker discoveries and therapeutics. Brief. Funct. Genomics 2023, 22, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.H.; Lei, H.L.; Huang, L.R.; Tsai, L.H. Protective effect of excitatory amino acids on cold-restraint stress-induced gastric ulcers in mice: role of cyclic nucleotides. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2001, 46, 2285–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiba, Y.; Watanabe, C.; Mizumori, M.; Kaunitz, J.D. Luminal L-glutamate enhances duodenal mucosal defense mechanisms via multiple glutamate receptors in rats. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2009, 297, G781–G791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Zhang, B.; Yu, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Gao, F.; Zhou, G. L-Glutamate supplementation improves small intestinal architecture and enhances the expressions of jejunal mucosa amino acid receptors and transporters in weaning piglets. Plos One 2014, 9, e111950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.B. Factors affecting the variability in the observed levels of cadmium in blood and urine among former and current smokers aged 20-64 and ≥ 65years. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 2017, 24, 8837–8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O'Mahony, S.M. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: from bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterology and Motility : The Official Journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 2011, 23, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ridaura, V.K.; Faith, J.J.; Rey, F.E.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2009, 1, 6ra14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| FD (n = 54) | Control (n = 29) | р value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39.20 ± 11.51 | 35.41 ± 9.29 | 0.16 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 22/32 | 11/18 | 0.80 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.07 ± 3.04 | 21.58 ± 2.20 | 0.45 |

| Race | 0.46 | ||

| Ethnic Han | 53 | 29 | |

| Others | 1 | 0 | |

| Education | 0.30 | ||

| Primary | 5 (9.26%) | 1 (3.45%) | |

| Junior | 5 (9.26%) | 3 (10.34%) | |

| High/Technical secondary | 7 (12.96%) | 2 (6.90%) | |

| College degree and above | 37 (68.52%) | 23 (79.31%) | |

| SF36-MH | 54 (36-68) | 60.4 (52-72) | 0.02 |

| Subtype | |||

| PDS | 9 (16.67%) | ||

| EPS | 2 (3.70%) | ||

| PDS + EPS | 43 (79.63%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).