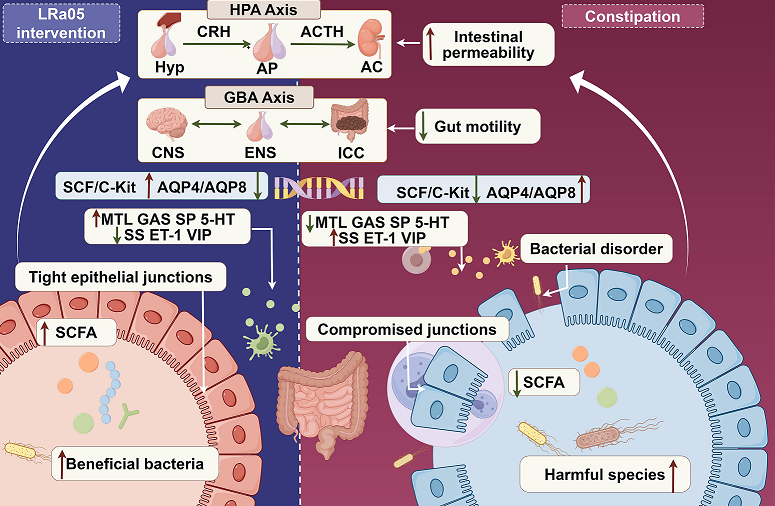

3.1. LRa05-Mediated Alterations in Excretory Patterns and Intestinal Functionality

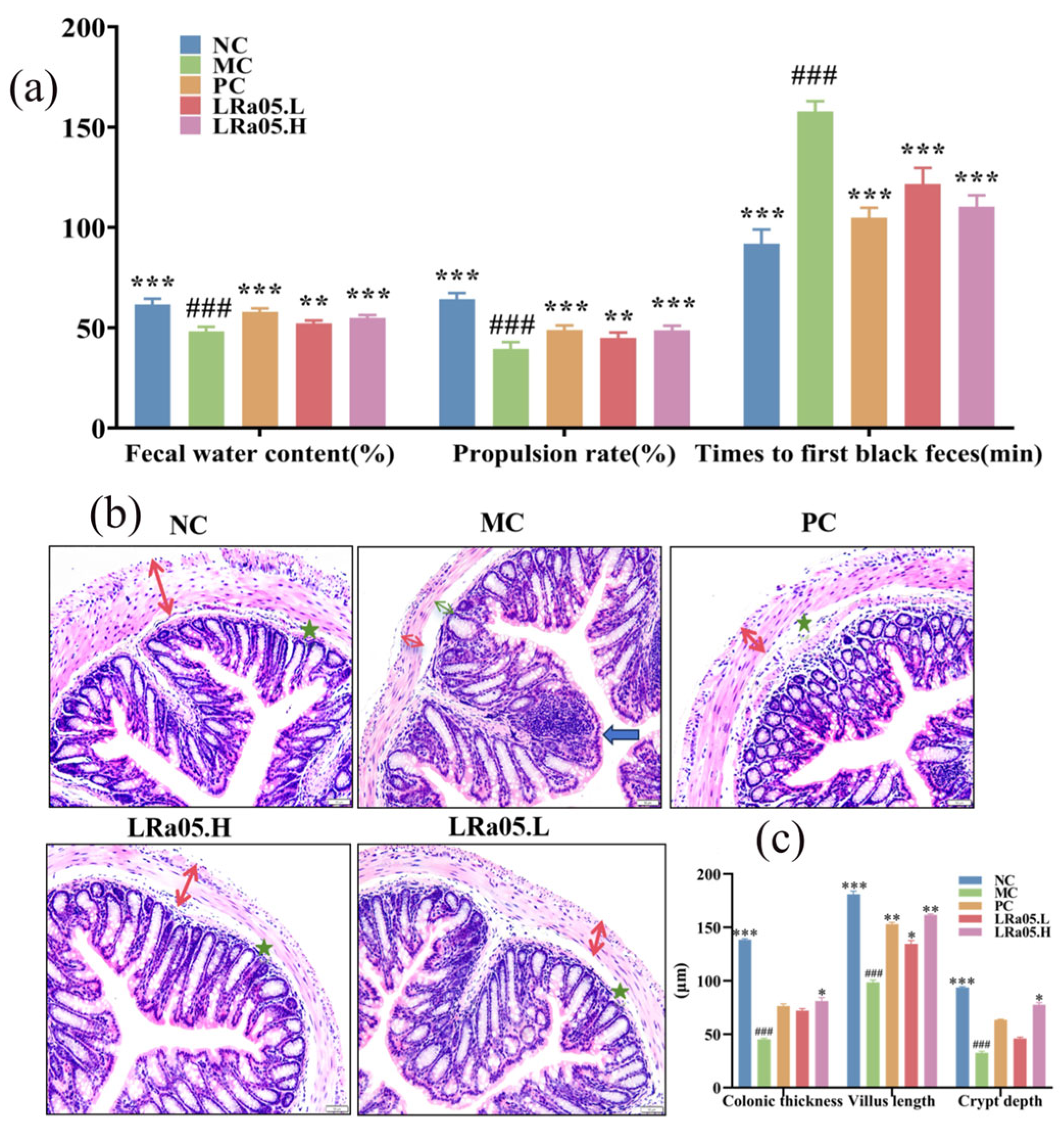

Constipation pathophysiology manifests as colonic dysmotility, diminished defecation frequency, and prolonged intestinal transit latency. When compared to the NC group, the loperamide-induced constipation model (MC group) demonstrated marked stool dehydration, exhibiting 38.2% reduction in fecal water content versus native controls (NC, 61.5 ± 1.7%; MC, 48.2 ± 2.1% [g H₂O/g stool],

p < 0.001;

Figure 1a). The duration until the initial occurrence of black feces was notably prolonged (NC, 91.8 ± 7.1; MC, 157.8 ± 5.1 min,

p < 0.001; Fig 1a). This indicated that the mice clearly experienced defecation difficulties after the establishment of the constipation model.

Upon intragastric delivery of Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05, there was a significant elevation in the moisture content of mouse feces relative to the MC group (p < 0.01) reaching 52.17% and 54.83% in the low- and high-dose groups (LRa05.L and LRa05.H), respectively. Additionally, the time to initial black feces passage showed a substantial reduction (p < 0.001 vs. MC group), with decreases of 22.9% (LRa05.L, 121.7 ± 8.0 min) and 30.1% (LRa05.H, 110.3 ± 5.6 min) for the two dosage regimens.

These results implied that

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 has the potential to optimize defecation-related metrics in mice suffering from constipation. Specifically, it could stimulat the defecation process and boosts the moisture content of feces. In prior investigations, it has been convincingly shown that

Bifidobacterium strains are capable of substantially accelerating intestinal peristalsis, preserving the water content within feces, and reducing the time taken for defecation. Collectively, these observations underscore the crucial role that probiotics play in alleviating constipation symptoms [

21].

Disrupted intestinal motility may extend fecal retention in the colon, resulting in excessive water reabsorption from intestinal contents and subsequent formation of dry, hardened stools. As depicted in

Figure 1a and

Figure S1, the carbon powder transport experiment demonstrated that mice in the MC group exhibited significantly reduced intestinal propulsion capacity, with an intestinal propulsion rate of 39.3 ± 3.4%, which was markedly lower than that of NC group (64.2 ± 3.0%,

p < 0.001). Significantly, the intervention with LRa05 enhanced intestinal propulsion in a dose-dependent manner (LRa05.L, 44.8 ± 2.8%; LRa05.H, 48.7 ± 2.3%). The effect was especially remarkable at elevated dosages, with a marked disparity relative to the MC group (

p < 0.001). These findings corroborated existing literature demonstrating that

Lactobacillus rhamnosus enhanced gastrointestinal transit efficiency and ameliorates constipation by modulating intestinal motility, thereby aligning with the observed functional effects [

22].

Table S2 delineated longitudinal alterations in body mass and food intake profiles across experimental cohorts. Univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed the trend of weight loss in intervention groups relative to baseline controls (NC group) during modeling phase (

Δmass = 0.62-0.86 vs. 1.02 g). The administration of

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 (LRa05.H, 2.4×109 CFU/d) restored adipostatic equilibrium, achieving mass accretion indices comparable to the NC group (

Δmass = 0.58 vs. 0.81 g,

p > 0.05), whereas model group (MC group) exhibited negligible somatic recovery (

Δmass = 0.08 g).

A quantitative investigation disclosed that, during the course of treatment, the food intake of the MC group's constipated mice was diminished by 25% in comparison with the NC group. Subsequent probiotic intervention with

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 restored circadian feeding rhythms, achieving 99% recovery of food intake. The findings indicated that LRa05 could alleviate the weight loss and food intake reduction caused by constipation in mice to a certain extent. This might be related to the dual-action mechanism of LRa05. For example, it enhanced ghrelin-mediated orexigenic signaling while suppressing leptin-induced appetite inhibition, thereby playing a role in improving the symptoms associated with constipation-induced decreases in food intake and body weight in mice [

23].

3.2. Impact of LRa05 on the serum concentrations of gastrointestinal regulatory peptides

To investigate whether Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 is capable of modulating the levels of gastrointestinal hormone peptides, serum levels of MTL, GAS, SP, SS, ET-1, VIP, and 5-HT were quantified. In this context, MTL, GAS and SP, as excitatory neurotransmitters, enhanced gastrointestinal motility, while ET-1, SS and VIP, as inhibitory ones, decreased it. In the intestine, a dynamic equilibrium exists between inhibitory peptides and excitatory peptides, which respectively regulate intestinal secretion and absorption functions. 5-HT bidirectionally regulates gastrointestinal motility. Deficiency causes constipation, while excess leads to diarrhea.

The results, as depicted in

Table 1, revealed a significant reduction in the concentrations of excitatory neurotransmitters, namely SP, MTL, and GAS, when comparing the MC group with the native NC group (

p < 0.001). Specifically, the concentration of MTL, GAS and SP measured 395.0 ± 8.6 pg/mL, 66.4 ± 2.2 pg/mL, and 304.1 ± 8.0 pg/mL respectively. In stark contrast, in the MC group, these levels decreased to 264.8 ± 13.5 pg/mL, 36.8 ± 2.4 pg/mL, and 176.4 ± 8.5 pg/mL, respectively. The observed neurotransmitter depletion likely reflects a vicious cycle where constipation-induced ICC/ENS damage, inflammation, and SCF/C-Kit suppression collectively impair excitatory signaling, exacerbating colonic inertia. Upon the intervention of LRa05, when compared with the concentration in the MC group, the high-dose LRa05 could significantly restore the concentration of GAS and SP (

p < 0.001). Specifically, the level of GAS increased by 31.1% (from the baseline value in the MC group to 48.2 ± 1.5 pg/mL), and the level of SP increased by 26.7% (from the baseline value in the MC group to 223.5 ± 5.6 pg/mL). This suggested that

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 beneficially regulates excitatory neurotransmitter levels in constipation. By restoring their reduced levels, it could enhance gastrointestinal motility. LRa05 likely promoted SP and GAS synthesis or release, perhaps by interacting with gut-related receptors or signaling pathways involved in neurotransmitter production and secretion. It could also modulate neurotransmitter-producing cell activity, raising levels and improving gut function [

24].

Meanwhile, compared with the NC group, the levels of inhibitory neurotransmitters VIP, SS, and ET-1 (

Table 1) in the serum of MC group were significantly elevated (

p < 0.001), reaching 174.1 ± 5.7 pg/mL, 135.8 ± 5.5 pg/mL, and 216.7 ± 10.0 pg/mL respectively. This dominance of inhibitory peptides likely promotes excessive intestinal water absorption, contributing to dehydration-associated constipation. The elevated inhibitory neurotransmitters in constipated mice likely represent a maladaptive interplay between neuroimmune activation, compensatory dehydration mechanisms, and ENS-ICC cross-talk disruption. Targeting VIP/SS/ET-1 signaling (

e.g., receptor antagonists) or restoring neuro-glial-ICC balance could break this cycle and alleviate dehydration-related constipation. After the intervention of LRa05, the levels of VIP, SS, and ET-1 in the high-dose group were significantly reduced by 18.06%, 36.44%, and 38.30% (from the baseline value in the MC group to 142.6 ± 7.1 pg/mL, 86.3 ± 2.5 pg/mL, 133.7 ± 7.9 pg/mL,

p < 0.01), respectively. These findings suggested that LRa05 rebalanced gut neurotransmission by suppressing inhibitory pathways, likely via inhibiting enzymes/transcription factors involved in their synthesis or modulating secretory cell activity. This intervention restored the gut's excitatory-inhibitory neurotransmission balance, potentially enhancing gastrointestinal motility [

25]. Through dual modulation of peptide networks, LRa05 could concurrently promote intestinal fluid secretion, alleviate luminal dehydration, and softens fecal consistency. This multi-targeted intervention addresses the upstream etiology of constipation-disruption of mucosal water-salt homeostasis-by restoring epithelial transport function and neuromodulatory signaling.

5-HT levels, which bidirectionally regulate gut motility, were severely reduced in constipated mice (NC, 5.68 ± 0.20 pg/mL; MC, 2.24 ± 0.06 pg/mL;

p < 0.001;

Table 1). The collapse of 5-HT levels in constipated mice reflects EC cell failure, microbiota-ENS-ICC axis disruption, and inflammatory-ischemic damage. Restoring 5-HT signaling (e.g., probiotics, 5-HT4 agonists, or tryptophan supplementation) could break the cycle of motility arrest and dehydration. Similar to moxapride applied in the PC group, partially restored 5-HT (PC, 5.07 ± 0.16 pg/mL; LRa05.L, 2.90 ± 0.08 pg/mL; LRa05.H, 3.66 ± 0.11 pg/mL;

p < 0.01 or

p < 0.001;

Table 1). Though less effective than the drug moxapride, LRa05 likely enhanced tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH1) activity in enterochromaffin cells or modulates gut microbiota metabolites to boost 5-HT signaling [

26]. Optimal 5-HT concentrations balance bidirectional signaling in the gut-brain axis (GBA) while coordinating hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis cross-talk, thereby optimizing intestinal motility and mucosal permeability. Specifically, 5-HT binds to 5-HT4 receptors on enteric neurons, stimulating acetylcholine release and enhancing smooth muscle contraction, thereby accelerating intestinal transit. Conversely, chronic 5-HT elevation (

e.g., in diarrhea) desensitizes 5-HT receptors (

e.g., 5-HT4), paradoxically reducing motility. Furthermore, excess 5-HT recruits mucosal immune cells (

e.g., mast cells) to release inflammatory mediators (

e.g., histamine), indirectly inhibiting smooth muscle activity.

Collectively,

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 exerts its constipation-relieving effects through multi-faceted modulation of gut hormone peptides, with a primary focus on GBA pathway. These effects are hypothesized to be mediated via direct interactions with intestinal epithelial cells, microbial metabolites, or host signaling cascades, underscoring its potential as a functional probiotic. This observation aligns with prior studies demonstrating that divergent

Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains could selectively elevate MTL and 5-HT levels via distinct molecular routes, thereby improving gastrointestinal transit in constipated murine models [

27]. Gut microbiota are known to directly or indirectly synthesize and regulate host neuroactive compounds such as 5-HT and SP, thereby exerting far-reaching effects on both enteric nervous system (ENS) and central nervous system (CNS) physiology. Mechanistically, LRa05 augmented 5-HT biosynthesis through tryptophan metabolic reprogramming-manifested by TPH1 upregulation and IDO1 inhibition-and promoted SP secretion, thereby triggering vagal afferent signaling to brainstem nuclei such as the nucleus tractus solitarius. Furthermore, through suppression of pro-inflammatory mediators ET-1 and VIP, LRa05 restored gut-brain signaling integrity. Specifically, ET-1 reduction mitigated intestinal ischemia and inflammatory responses, whereas VIP downregulation diminishes its inhibitory effects on ENS excitability, rebalancing smooth muscle contractility. This multi-transmitter balancing capability positions LRa05 as a promising therapeutic candidate, potentially outperforming single-target interventions such as 5-HT agonists by concurrently addressing gastrointestinal motility disorders, visceral hypersensitivity, and central nervous system comorbidities.

The observation that the positive control group (e.g., treated with mosapride citrate) demonstrated more pronounced alterations in gastrointestinal peptide levels (e.g., MTL, VIP shown in Table1) relative to the probiotic intervention group (LRa05.), yet failed to achieve superior constipation relief (displayed by Figure1a), highlighted the multifactorial complexity of constipation regulation. This paradox underscores that gastrointestinal peptides alone do not fully govern constipation pathophysiology, and additional mechanisms-particularly those modulated by probiotics-are critical for symptom resolution.

3.3. Mediation of Colonic Histopathological Integrity by LRa05

To evaluate the restorative potential of

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 on colonic integrity, systematic histopathological analyses in loperamide-induced constipated mice were performed. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) stained colon sections were examined at 200× magnification to characterize tissue architecture (

Figure 1b) and quantify indices (

Figure 1c).

The NC group displayed intact colonic morphology featuring orderly intestinal villi alignment and abundant goblet cell populations within crypts. In contrast, the MC group exhibited hallmark colonic pathological alterations, including disrupted epithelial polarity, mucosal atrophy with muscularis dissociation (green arrow), focal inflammatory infiltrates (blue arrow), and significant muscularis propria thinning (red arrow) in

Figure 1b. Quantitative histomorphometric analysis demonstrated severe constipation-induced colonic structural degeneration (

Figure 1c). The smooth muscle layer thickness plummeted by 67.4% in the model group (MC, 45.2 ± 0.9 μm) compared to native controls (NC, 138.6 ± 6.7 μm;

p < 0.001), indicating compromised contractile capacity. The crypt depth and villus height reduced 65.1% and 45.6% (NC, 93.6 ± 0.8 and 181.3 ± 2.9 μm vs. MC, 32.7 ± 1.3 and 98.6 ± 2.1 μm). These metrics collectively reflect profound mucosal-muscular dissociation and impaired barrier functionality, hallmarks of chronic constipation pathophysiology. These observations aligned with established constipation models demonstrating goblet cell disorganization, muscular hypoplasia, and leukocyte migration [

28]. These pathological changes in the MC group likely arose from constipation-related physiological impairments. Slow fecal transit exerts abnormal mechanical stress on the colonic mucosa, which disrupts epithelial architecture and induces muscularis propria dissociation. Prolonged contractile hypoactivity in constipation progressively thins the muscular layer. Concurrently, compromised epithelial barrier function triggers focal inflammatory infiltrates via immune cell migration. The disorganization of goblet cells-critical for mucus production that maintains intestinal lubrication-further exacerbates mucosal dysfunction. Impaired mucus secretion culminates in dry, hardened stools, perpetuating a vicious cycle of colonic tissue damage [

29].

Notably, LRa05 administration dose-dependently reversed pathological remodeling. The low-dose group (LRa05.L) restored colonic architecture to levels comparable with the positive control (PC) group, demonstrating intermediate recovery of mucosal folds (PC, 76.3 ± 12.0 μm and 72.2 ± 6.8 μm) and goblet cell density. The high-dose group (LRa05.H) achieved the reestablished goblet cell stratification and attenuated inflammatory infiltration (Figure1b), which was critical for intestinal lubrication and barrier defense. Colon wall thickness surged 1.8-fold versus the model group (MC, 45.2 ± 0.9 μm vs. LRa05.H, 81.2 ± 0.9 μm;

Figure 1c), reinstating contractile vigor. The crypt depth and villus height achieved 2.7-fold recovery, and 64.1% restitution (MC, 32.7 ± 1.3 and 98.6 ± 2.1 μm vs. LRa05.H, 87.8 ± 2.0 and 161.7 ± 1.1 μm;

Figure 1c), enhancing absorptive surface area. These findings demonstrated LRa05’s capacity to repair mucosa-muscularis dissociation and reinstate colonic architectural homeostasis, aligning with its prokinetic efficacy. This functional profile parallelled reports that

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRJ-1 alleviated distal colonic injury via goblet cell regeneration and muscularis reinforcement (

p < 0.05).

The observed effects of

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 were likely mediated by dual mechanisms, augmentation of gastrointestinal motility and biosynthesis of bioactive metabolites, which acted synergistically to mitigate constipation-induced colonic injury. Reduced fecal retention alleviates mechanical stress on the mucosa and limits exposure to cytotoxic metabolites (

e.g., ammonia, secondary bile acids) and pathogenic bacteria-derived endotoxins. This mitigates epithelial barrier disruption and inflammatory cascades, preserving crypt-villus architecture and goblet cell functionality. Additionally, as a commensal probiotic, LRa05 could ferment dietary fibers to produce SCFAs (

e.g., acetate, propionate, butyrate), which exert pleiotropic restorative effects [

30,

31]. The histomorphometric data demonstrated that

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 mitigated constipation-associated colonic degeneration through mucosal barrier regeneration and anti-inflammatory reprogramminga. These structural improvements likely synergize with its prokinetic effects (

Figure 1a) and serotonergic modulation (

Table 1), collectively restoring gut homeostasis.

3.4. LRa05's Role in Affecting the Content of SCFAs

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), the primary metabolites of gut microbial fermentation, alleviate constipation through multiple mechanisms: modulating gut microbiota composition, stimulating luminal hydration, and preserving intestinal barrier integrity [

32].

As shown in

Table 1, constipated mice treated with loperamide in MC group exhibited significantly reduced cecal SCFA levels relative to the NC group (

p < 0.05). The levels of acetic acid (9.46 µmol/g), propionic acid (5.43 µmol/g), butyric acid (4.17 µmol/g), isobutyric acid (3.78 µmol/g), valeric acid (1.32 µmol/g), and isovaleric acid (2.10 µmol/g) were notably lower the NC group. These reductions could be attributed to constipation-induced fecal stasis disrupting the gut microbial ecosystem, leading to suppression of SCFA-producing taxa such as

Bacteroides,

Clostridium, and

Roseburia. This systemic SCFA depletion be likely to contributed to impaired intestinal motility and stool desiccation in constipation.

Notably,

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 intervention dose-dependently restored SCFA production, with the high-dose group (LRa05.H) showing superior efficacy (

p < 0.01). Specifically, the high-dose LRa05 could increase the acetic acid and butyric acid contents to 38.2 µmol/g and 12.3 µmol/g, respectively, which were higher than thosein the NC group (27.1 µmol/g and 8.55 µmol/g). Acetic acid, a dominant SCFA, binds to G protein-coupled receptor 43 (GPR43) on enteroendocrine cells and enteric neurons, triggering release of motility-stimulating peptides (e.g., PYY, GLP-1), which accelerate colonic transit [

33]. Butyric acid, functions as the main energy source for colonocytes, undergoing β-oxidation to generate ATP essential for maintaining epithelial integrity and tight junction function (e.g., upregulating occludin and zonula occludens-1). Additionally, butyrate acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-6) while promoting regulatory T-cell (Treg) differentiation. This dual action mitigates "leaky gut"-induced inflammation and preserves ENS and ICC function critical for motility [

34]. Propionate enhances vagal afferent signaling to the brainstem, thereby stimulating defecation reflexes. Valerate modulates serotonin receptor (5-HT4) sensitivity, potentiating smooth muscle contraction. As a probiotic, LRa05 competitively inhibits pathogenic bacteria (

e.g.,

Escherichia,

Enterobacter) while promoting symbiotic SCFA-producing microbiota. This microbial rebalancing reactivates dietary fiber fermentation-the primary substrate for SCFA synthesis. Mechanistically, LRa05 upregulates key microbial enzymes involved in SCFA biosynthesis, including butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase (for butyrate) and phosphate acetyltransferase (for acetate), thereby restoring SCFA metabolic pathways disrupted in constipation.

These results indicate that

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 exerts constipation-relieving effects through dual mechanisms: restoring microbiota-gut crosstalk via SCFA-mediated motility enhancement, and preserving intestinal barrier homeostasis through butyrate-driven anti-inflammatory pathways. The underlying mechanisms involve intricate interactions among LRa05, microbiota modulation, and SCFA-mediated host signaling networks, which collectively target the core pathophysiology of constipation, including motility dysfunction, barrier injury, and neuroendocrine dysregulation. Compared to the MC group, the PC group (treated with mosapride citrate) demonstrated partial restoration of SCFA production, though its efficacy was significantly weaker than that of the probiotic intervention group (LRa05.L and LRa05.H). For instance, acetic acid levels in the mosapride group reached 21.6 µmol/g, compared to 38.1 µmol/g in LRa05.H and 9.46 µmol/g in MC (

Table 1). This disparity suggested that mosapride citrate and LRa05 operate through divergent mechanistic pathways to alleviate constipation. The differential efficacy between mosapride citrate and LRa05 underscores the importance of microbiota-centric therapies in addressing SCFA-mediated constipation. While mosapride transiently improves motility, probiotics achieve sustained recovery by rebuilding the gut ecosystem and enhancing host-microbe crosstalk. Combining prokinetics with probiotics may synergize motility enhancement and SCFA restoration.

3.5. LRa05's Role in Affecting the Expression of Linked Genes

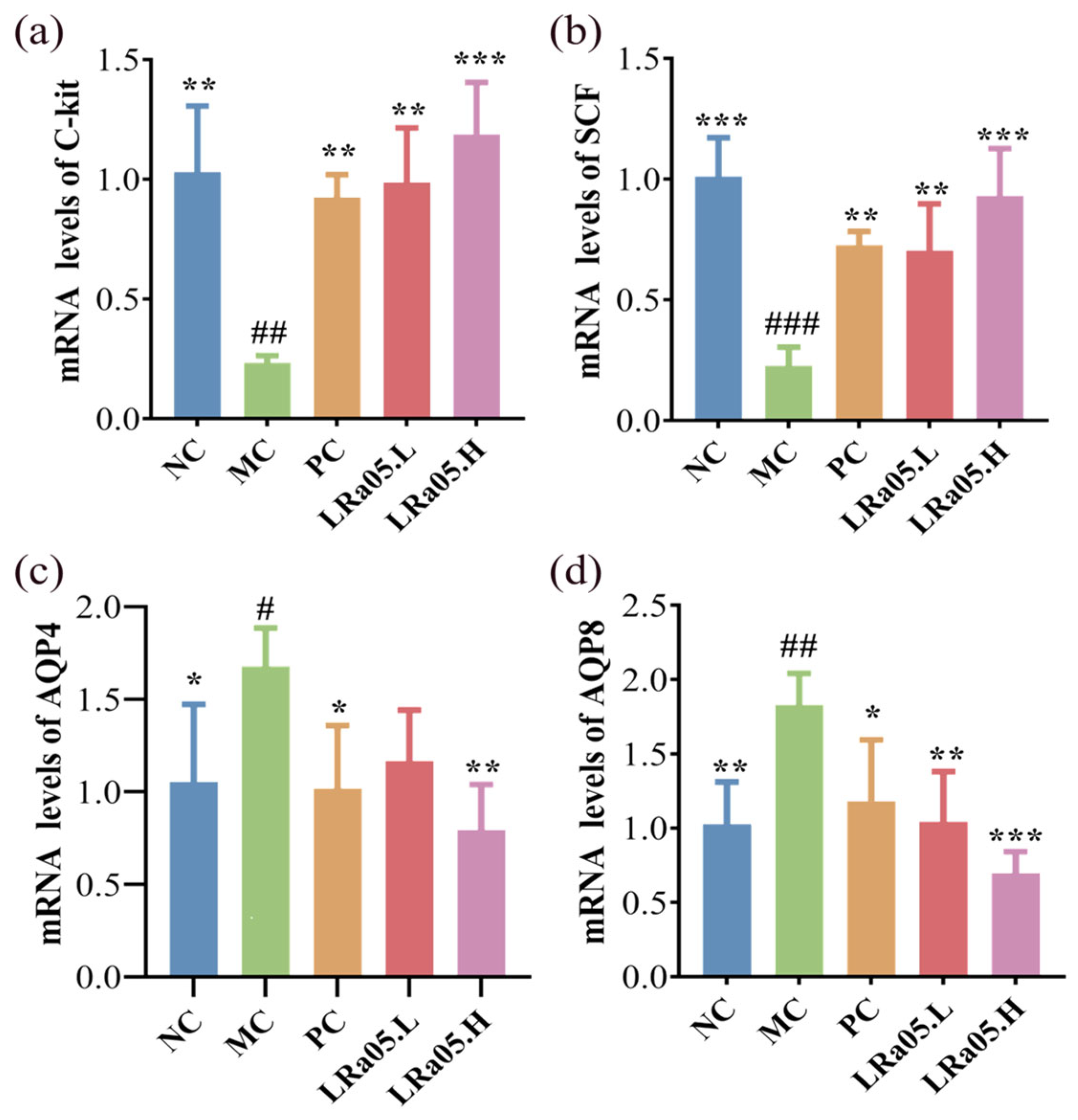

To delve deeper into the mechanism underlying the effects of

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05, the critical genes governing gastrointestinal motility and fluid homeostasis were profiled systematically (

Figure 2). ICCs, the pacemakers of gastrointestinal rhythmicity, coordinate smooth muscle contractions through electrical slow waves [35, 36]. The SCF/C-Kit axis is indispensable for ICC maintenance, with SCF binding to its tyrosine kinase receptor C-Kit to drive ICC proliferation and network formation [

37]. Dysregulation of this pathway disrupts slow-wave generation, precipitating motility disorders [

38].

The qRT-PCR data of mRNA levels revealed constipation-induced colonic suppression of both SCF and C-Kit (4.41- and 3.8-fold downregulation, respectively) in the MC group versus the NC group (

p < 0.01 or

p < 0.001;

Figure 2a and 2b). This was because SCF/C-Kit signaling was essential for the growth, survival, and functional maintenance of ICC-the pacemaker cells responsible for generating intestinal slow-wave potentials. Reduced SCF expression and C-Kit receptor downregulation disrupt ICC network integrity, leading to diminished slow-wave activity and impaired gastrointestinal motility. This molecular perturbation aligns with the pathophysiological hallmark of chronic constipation-the loss of ICC density and function. ICC depletion directly compromises the intrinsic myoelectric activity of the intestinal smooth muscle, resulting in aberrant peristaltic contractions and reduced propulsive motility, which are cardinal features of hypomotility disorders. The SCF and C-Kit axis dysfunction thus represents a critical molecular node linking colonic mucosal signaling to motility deficits in constipation, underscoring its role as a potential target for restoring ICC-mediated gastrointestinal rhythm.

Following treatment with various doses of LRa05 or administration of mosapride citrate tablets, all experimental groups demonstrated differential recovery responses. LRa05 intervention dose-dependently restored SCF and C-Kit expression levels (

p < 0.01 for LRa05.L and

p < 0.001 for LRa05.H vs. MC), showing 73.1% and 47.2% recovery with low-dose treatment, and 92.6% and 69.6% recovery with high-dose treatment. Mechanistically, SCF activation bound to C-Kit receptors on ICC progenitor cells, promoting their proliferation and differentiation. This molecular restoration correlated with the histological observations of muscularis propria thickening (

Figure 1c) and enhanced intestinal propulsion (

Figure 1a), suggesting LRa05 reactivates ICC-dependent pacemaking to reinstate peristaltic rhythms. This recovery likely stemmed from LRa05-mediated GBA regulation. Probiotic SCFAs boosted enterochromaffin cell activity, increasing 5-HT biosynthesis (

Table 1). 5-HT activates 5-HT4 receptors on epithelial cells or ICCs, triggering cAMP/PKA signaling that enhances SCF secretion [

39]. SCF, in turn, binds to C-Kit on ICCs, promoting their proliferation and restoring slow-wave generation (

Figure 2b). In addition, Lactobacillus strains, including LRa05, could directly engage Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) on intestinal epithelial cells, activating MyD88-dependent signaling to upregulate SCF transcription [

40]. SCFAs amplify this process by stabilizing epithelial barrier function, ensuring sustained SCF release [

41]. The PC group (mosapride citrate-treated) exhibited only partial restoration of SCF and C-Kit expression (

e.g., 53.8% and 32.4% recovery vs. MC, respectively), significantly lagging behind the probiotic intervention groups. This disparity implies that mosapride’s monotherapy primarily targets acute motility enhancement rather than addressing the multifactorial pathophysiology of constipation.This differential therapeutic effect can be mechanistically attributed to Mosapride's role as a selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist, which transiently enhances serotonin-dependent smooth muscle contractility. However, it lacks direct regulatory effects on ICC progenitor cell proliferation or SCF transcriptional activity-key processes required for sustainable ICC network regeneration. Moreover, Mosapride fails to restore intestinal microbiota diversity or SCFA concentrations (notably butyrate), which are critical for epithelial SCF secretion and ICC metabolic homeostasis.

Complementary to motor function, the levels of aquaporins (AQP4 and AQP8) governing intestinal water transport were assessed. Compared with the NC group, chronic constipation led to a significant upregulation of AQP4 and AQP8 in the MC group, as shown in

Figure 2c,d. Specifically, the expression level of AQP4 was 1.68-fold higher (

p < 0.05), and that of AQP8 was 1.83-fold higher (

p < 0.01) than those in the NC group. This aligned with prior evidence that AQP overexpression exacerbates pathological fluid retention and stool desiccation [

42]. LRa05 administration reversed this dysregulation, with high-dose treatment reducing AQP4 and AQP8 expression to 47.3% and 38.1% of MC levels (

p < 0.01), effectively rebalancing luminal hydration. Overexpression of AQPs in constipation is often driven by inflammatory cytokines (

e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) that upregulate AQP transcription via NF-κB/MAPK pathways. LRa05-derived SCFAs could suppress these pathways, reducing AQP4/AQP8 expression [

43,

44]. SCFAs could interact with GPR43 receptors on enterocytes, activating intracellular calcium signaling to modulate AQP trafficking or degradation, thereby reducing membrane AQP density [

45]. From a gastrointestinal peptide synergy perspective,

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 lowers inhibitory peptides (VIP, SS; Table. 1), which were known regulators of AQP activity. Reduced VIP/SS levels could decrease cAMP signaling in enterocytes, thereby indirectly normalizing AQP-mediated water reabsorption. Concurrently, elevated 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT;

Table 1) and restored MTL enhance fluid secretion by stimulating chloride channels (

e.g., cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, CFTR), counteracting AQP-driven water retention. The coordinated actions of AQP modulation and neuropeptide regulation synergistically maintain optimal fecal viscoelasticity (rheological plasticity) and prevent stool dehydration, thereby preserving intestinal transit efficiency.

This dual modulation of inhibitory-excitatory peptide networks likely rebalanced intestinal water flux, alleviating constipation-associated dehydration. At the motility level, SCF/C-Kit activation rebuilds ICC networks, rescuing slow-wave activity for propulsive contractions [

46]. Concurrently, at the osmoregulatory level, AQP suppression prevents excessive water extraction, maintaining stool plasticity [

47]. This mechanistic synergy could explain the accelerated fecal transit, improved stool hydration, and normalized defecation frequency observed in LRa05-treated groups(

Figure 1a).

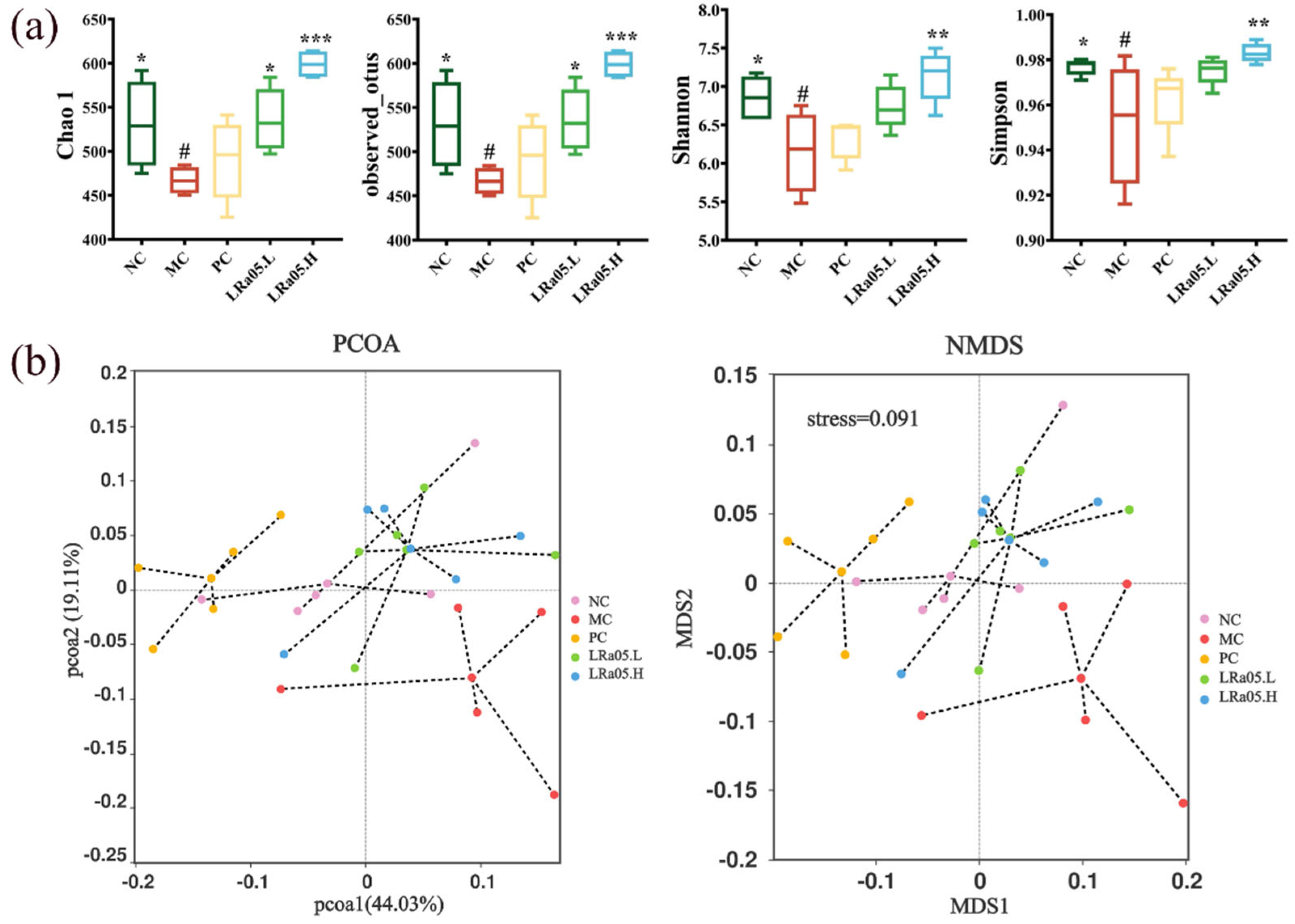

3.6. Functional Role of LRa05 in Modulating the Gut Microbiota

To evaluate the microbiota-modulatory effects of

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 in constipated mice, 16S rRNA gene sequencing targeting the V3-V4 hypervariable regions was conducted on colonic contents collected at the study endpoint. Alpha diversity metrics (Chao1 and observed otus for richness, Shannon and Simpson for diversity) were analyzed via species richness and community diversity indices (

Figure 3a). Beta diversity was assessed using PCoA and NMDS based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (

Figure 3b).

In the MC group, significant (

p < 0.05) reductions were observed in both microbial richness (Chao1 and observed OTUs) and diversity (Shannon and Simpson indices) compared to the NC group. The LRa05 intervention reversed these perturbations in a dose-dependent manner, with the LRa05.H group demonstrating significantly enhanced Chao1 richness and observed OTUs (

p < 0.001), as well as Shannon and Simpson indices (

p < 0.01), surpassing both the low-dose LRa05.L and PC groups (

Figure 3a).

PCoA and NMDS revealed distinct clustering patterns. Compared to the NC group, the MC group exhibited a marked separation along the second principal component (PC2, 19.1% variance), confirming constipation-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis (

Figure 3b). Notably, both LRa05.H and LRa05.L groups overlapped with the NC group, indicating partial restoration of microbiota composition. Conversely, the PC group showed a clear separation along the first principal component (PC1, 44.0% variance) relative to other groups, highlighting the distinct role of moxapride (used in the PC group) in modulating gut microbiota composition.

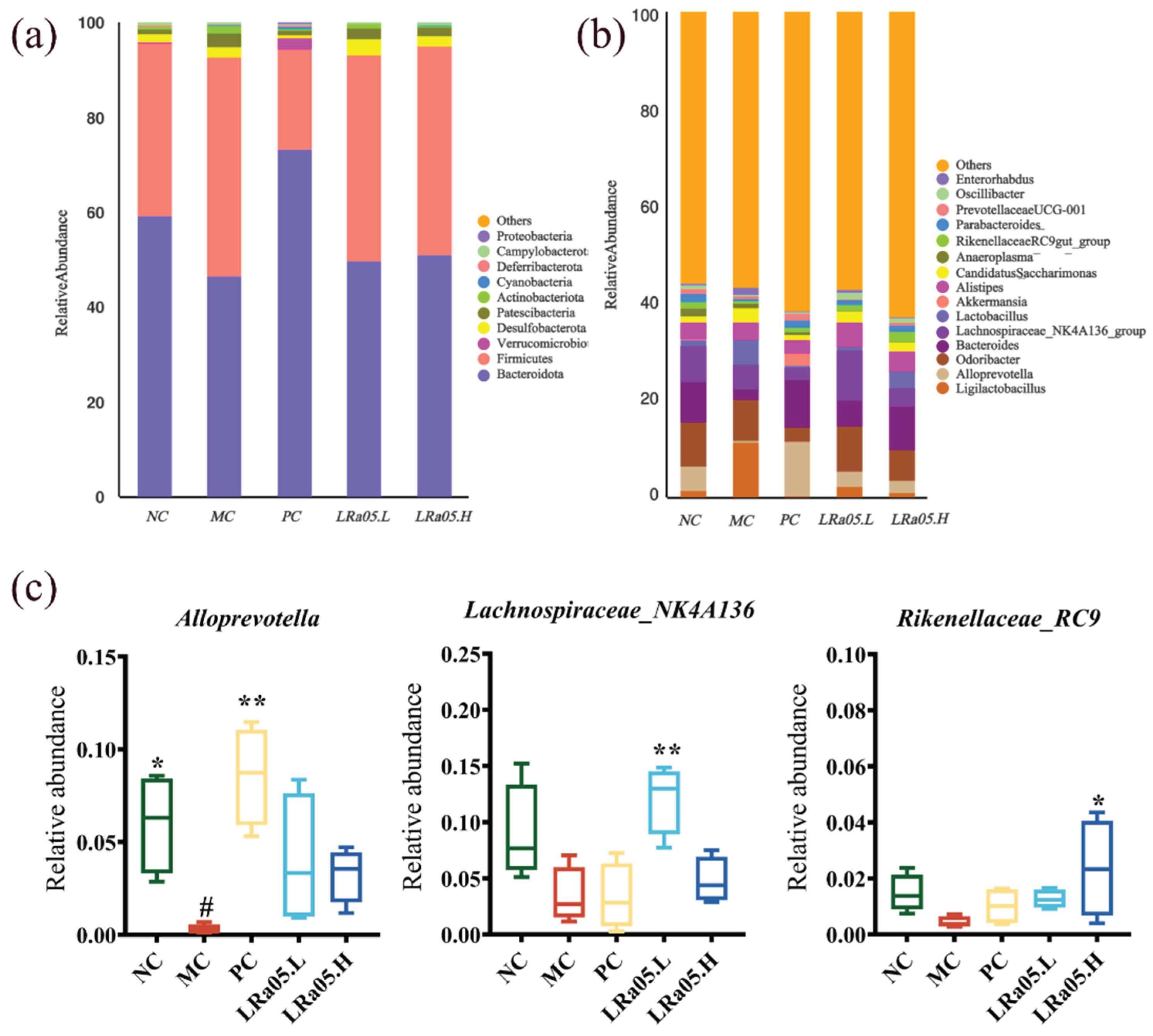

Consistent with established gut microbiota profiles, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes dominated (>90% combined abundance) at the phylum level (

Figure 4a) [

48]. Loperamide-induced constipation disrupted gut microbiota composition, with Bacteroidetes abundance decreasing by 21.2% and Firmicutes increasing by 26.1% relative to the NC control (

p < 0.01). This microbial dysbiosis resulted in a significantly reduced Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio in the MC group (1.01±0.12) compared to NC group (1.62 ± 0.18;

p < 0.05). LRa05 intervention restored the F/B ratio in a dose-dependent manner (LRa05.L: 1.38 ± 0.15; LRa05.H: 1.52 ± 0.14), with the high-dose group achieving NC-equivalent levels (

p > 0.05). This finding aligns with previous studies demonstrating that lactic acid bacteria stabilize F/B ratios to mitigate inflammation and enhance epithelial barrier function [

49].

Constipated microbiota is characterized by decreased beneficial bacteria and increased potential pathogens [

50]. At the genus level (

Figure 4b, 4c), loperamide induced significant compositional shifts. LRa05 intervention notably restored beneficial taxa including

Parabacteroides,

Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group,

Oscillibacter,

Alloprevotella, and

Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group, aligning with prior studies. For instance, functional fruit drinks relieved constipation by upregulating

Alloprevotella and enhancing barrier function [

51], while

Lactobacillus salivus Li01 restored

Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group and

Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group abundances to reduce inflammation [

52]. Emerging evidence indicates

Parabacteroides and

Oscillibacter metabolize dietary tryptophan into indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), a high-affinity aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligand that suppresses neuroinflammation and stabilizes enteric nervous system (ENS) function through gut-brain axis modulation. Mechanistically,

Alloprevotella negatively correlates with pro-inflammatory cytokines and produces SCFAs like butyrate to mitigate intestinal inflammation [

53].

Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, an anaerobic spore-forming probiotic, ferments plant polysaccharides into SCFAs to protect intestinal mucosa and inversely correlates with inflammation markers [

54].

Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group mediates anti-inflammatory effects through immune modulation, strengthening intestinal barrier integrity. In summary,

Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 exerted functional effects by restoring beneficial bacterial genera, promoting SCFA production, modulating inflammatory pathways, and enhancing intestinal barrier function. These concerted actions contribute to microbiota rehabilitation and defecation function recovery in constipation.

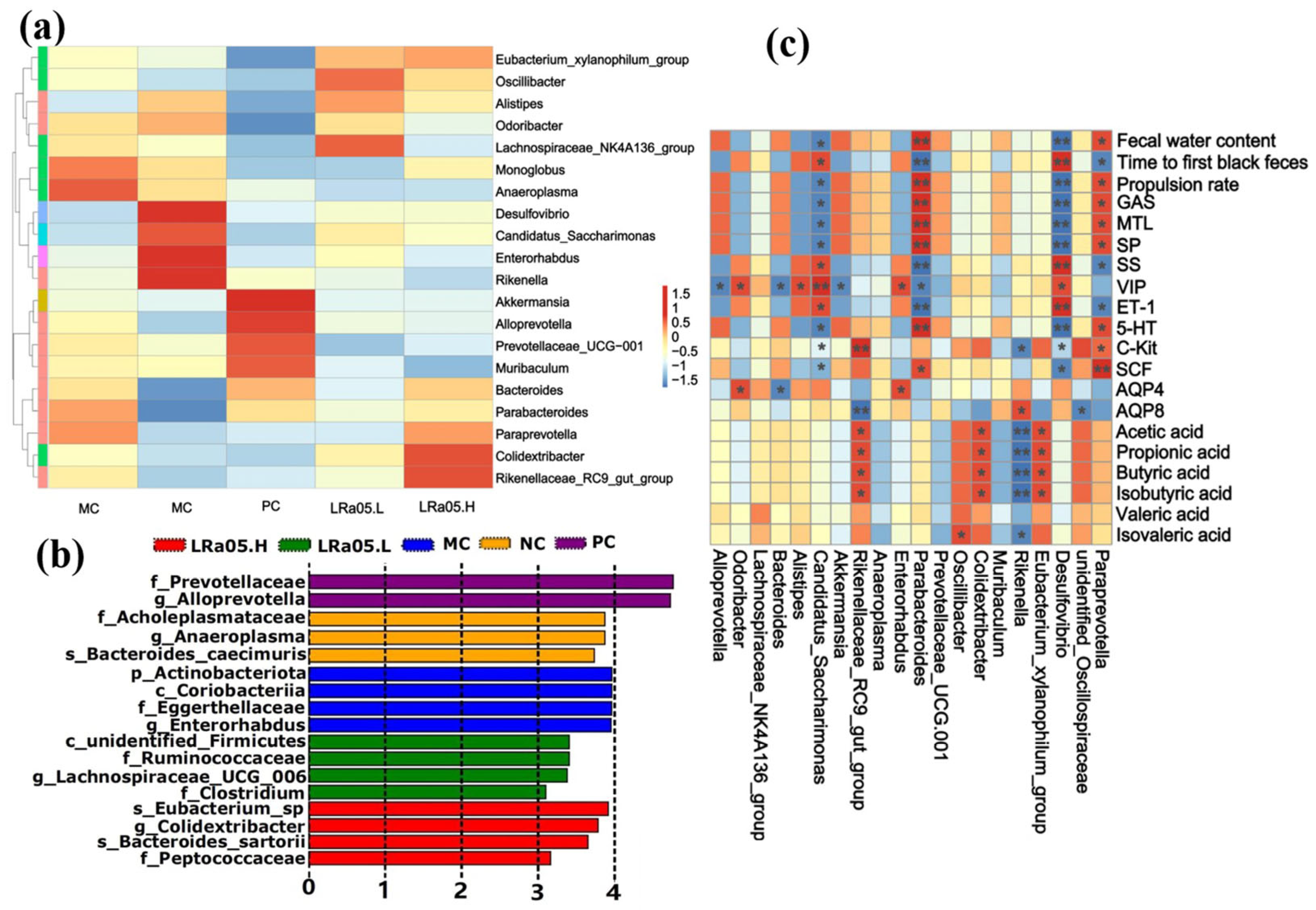

The heatmap and LEfSe analysis (LDA > 3.0,

Figure 5a and 5b) identified distinct microbial signatures across groups. Compared with the other group, the MC group exhibited significant enrichment of

Desulfovibrio,

Candidatus_Saccharimonas,

Enterorhabdus, and

Rikenella (LEfSe analysis, LDA score > 3.0,

p < 0.05). These microbial taxa (

Desulfovibrio,

Candidatus_Saccharimonas,

Enterorhabdus, and

Rikenella) have been extensively documented to be associated with intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction (

e.g., reduced tight junction protein expression and increased permeability) and exacerbation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production (particularly IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β) in both preclinical models and human cohort studies [

55]. Notably,

Enterorhabdus has been specifically implicated in triggering NF-κB-mediated inflammatory cascades through its metabolite interactions with intestinal epithelial cells, as demonstrated by in vitro transwell co-culture systems [

56]. It is worth noting that these inflammatory cytokines or signaling pathways may exacerbate constipation symptoms. For instance, IL-6 slows intestinal peristalsis by inhibiting cholinergic neuron activity in the ENS. TNF-α induces segmental hyperkinesia and transmission delay via RhoA/ROCK-mediated enhancement of smooth muscle contraction persistence. While IL-1β exacerbates fecal dryness through downregulating intestinal epithelial aquaporin and reducing luminal water secretion. This finding was further validated in correlation analysis (

Figure 5c), where

Enterorhabdus and

Rikenella demonstrated significant positive correlations with AQP4 and AQP8, respectively.

The LRa05.H group restored ecological equilibrium via enrichment of bacteria with SCFA synthesis, or immune regulatory functions (such as

Bacteroides,

Parabacteroides,

Paraprevotella,

Colidextribacter,

Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group) [

57]. For instance,

Bacteroides and

Parabacteroides species predominantly mediate SCFA production and mucin degradation, creating a prebiotic niche for secondary fermenters. These taxa provide metabolic substrates (

e.g., acetate, propionate) and mucin-derived oligosaccharides that sustain microbial communities critical for intestinal homeostasis [

58]. The LRa05.L group highlighted enrichment of beneficial bacteria such as

Eubacterium_xylanophilum_group (linked to carbohydrate metabolism and gut barrier integrity),

Oscillibacter (implicated in neurotransmitter production and mental health),

Alistipes (involved in immune regulation and inflammation reduction),

Odoribacter (correlated with improved lipid metabolism), and

Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group (promoting SCFA production critical for colonic health) [

59]. Notably, preferential proliferation of

Oscillibacter and Alistipes—which are specialized in synthesizing neurotransmitter precursors (

e.g., GABA, glutamate) and promoting immune tolerance through regulatory T cell activation—exerts synergistic neuroprotective and immunomodulatory effects [

60].

The LRa05.L (low-dose) and LRa05.H (high-dose) groups exhibited distinct induction patterns of beneficial taxa, demonstrating dose-dependent probiotic modulation of gut microbial ecology. Additionally, the PC group exhibited a unique gut microbiota modulation profile distinct from both LRa05.L and LRa05.H probiotic interventions. Specifically,

Akkermansia,

Alloprevotella,

Prevotellaceae_UCG-001, and

Muribaculum were significantly enriched in the PC group compared to probiotic-treated cohorts, with

Alloprevotella demonstrating the most pronounced enrichment. The PC-induced microbiota profile reflected the ecological mechanisms favoring mucin- and plant glycan-adapted taxa rather than functional resilience, distinct from the probiotic cross-feeding networks observed in LRa05 groups [

61].

The ecological divergence was further supported by the correlation analysis (

Figure 5c). The MC group exhibited significant microbial-metabolic correlations distinct from the probiotic-treated LRa05.H group. The

Desulfovibrio and

Candidatus_Saccharimonas with higher abundances in the MC group, were significantly negatively correlated with fecal water content, propulsion rate, levels of gut motility activators (GAS, MTL, SP, 5-HT), and expression of SCF/C-kit, while showing significant positive correlations with time to first black feces and levels of motility inhibitors (SS, VIP, ET-1). Notably,

Rikenella-another constipation-associated genus enriched in the MC group demonstrated a notable negative correlation with SCFA production (butyrate: r = -0.65; acetate: r = -0.61;

p < 0.05). This aligned with its known role in degrading mucin glycans and releasing pro-inflammatory mediators (

e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), which suppress colonic fermentation and epithelial energy metabolism. The dominance of

Desulfovibrio in the MC group likely impairs gut motility through hydrogen sulfide-mediated smooth muscle relaxation, while its mucolytic activity exacerbates intestinal barrier dysfunction, triggering upregulation of SS/VIP [

62]. Concurrently,

Rikenella thrives in dysbiotic, inflamed environments by preferentially metabolizing host glycans over dietary fibers. This metabolic shift diverts microbial activity toward lactate and ammonia production, further acidifying the intestinal lumen and inhibiting SCFA biosynthesis. Collectively, these distinct microbial-metabolic interactions in the MC group highlight how constipation-associated dysbiosis disrupts host-microbe co-metabolism, perpetuating motility arrest and inflammatory cascades [

63].

In contrast, probiotic-enriched genera

Paraprevotella and

Parabacteroides in the LRa05.H group exhibited inverse correlations with these motility and metabolic parameters, suggesting beneficial modulation of gut function. Specifically,

Parabacteroides likely enhances motility via succinate-TGR5 receptor signaling, which potentiates 5-HT biosynthesis in enterochromaffin cells [

64]. Additionally,

Paraprevotella-derived anti-inflammatory metabolite 3-indolepropionic acid may suppress ET-1 production through nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of NF-κB inhibition [

65]. Furthermore, genera

Eubacterium_xylanophilum_group, Colidextribacter, and

Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group demonstrated significant positive correlations with SCFA production, underscoring their roles in metabolic regulation. Notably, taxa enriched in the positive control PC group (

Akkermansia,

Alloprevotella,

Prevotellaceae) exhibited negligible significant correlations with these functional parameters. The above findings suggested that dietary probiotic supplementation alleviates constipation symptoms through a multi-tiered microbiota-host signaling axis, for instance, SCFA biosynthesis, gastrointestinal regulatory reptide modulation, SCF/C-Kit pathway reactivation, AQP homeostasis restoration.