Submitted:

02 May 2024

Posted:

06 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

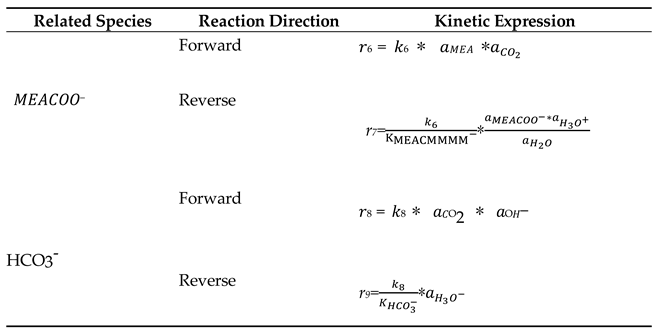

3.1. Model Parameters

3.2. Modelling Methodology

- The components within the properties section were selected and confirmed.

- In response to Aspen HYSYS acknowledging the selected components list, the amine package was recommended for process simulation, fluid properties prediction, and acid gas cleaning evaluations.

- Enter feed data into model parameters.

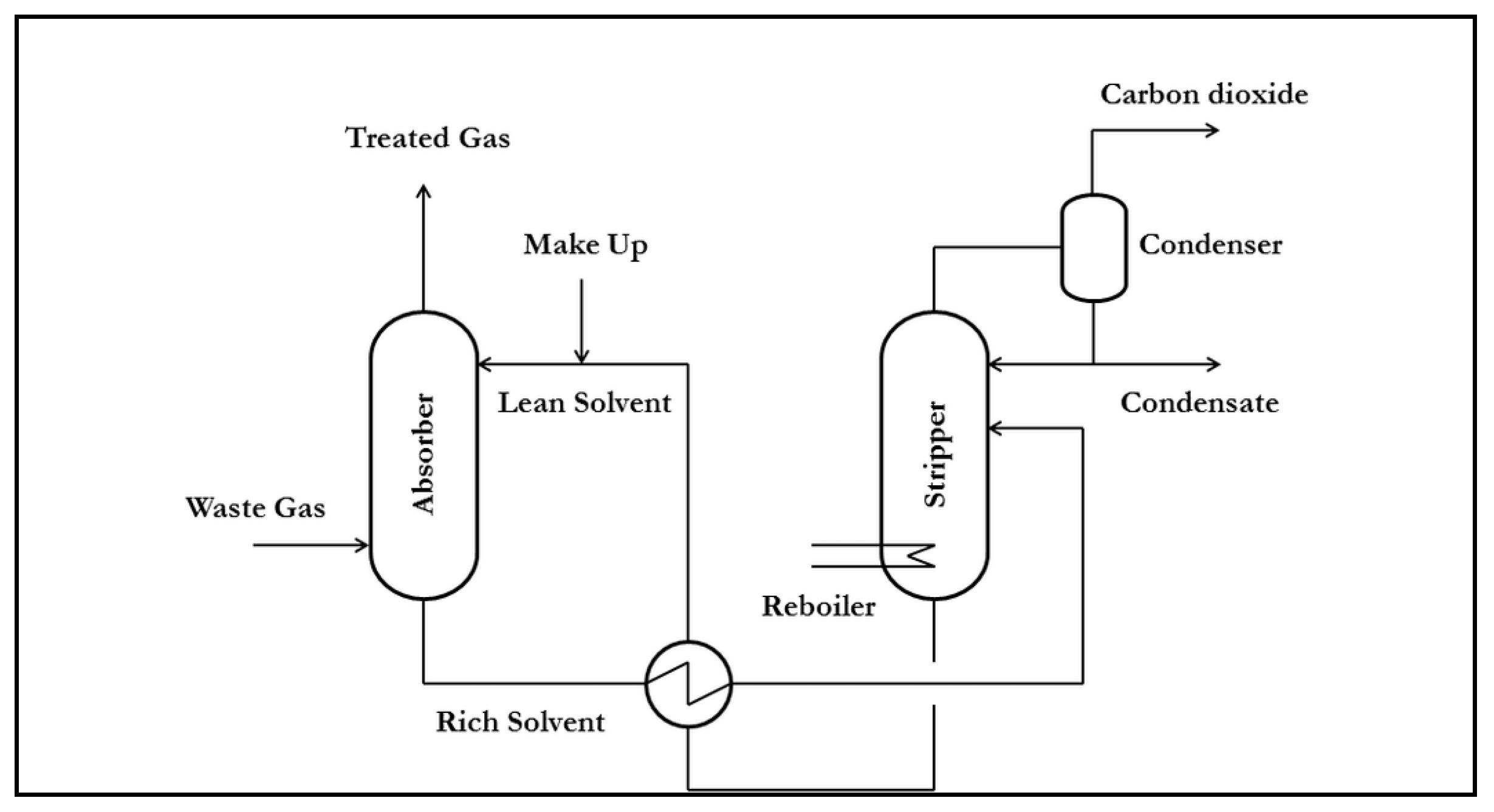

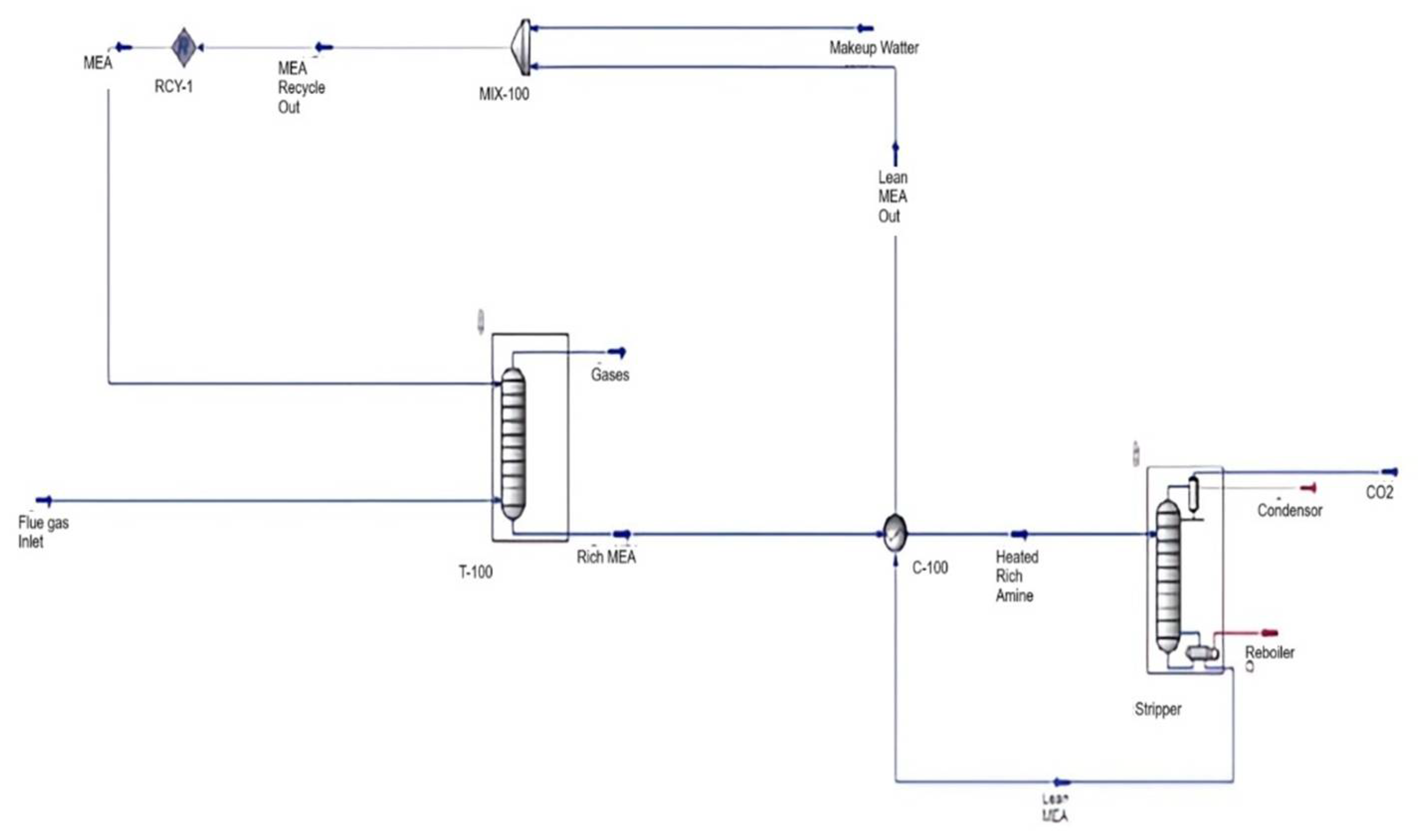

- Figure 3 shows the flowsheet, which includes the absorbing column, cross heat exchanger, stripper column with reboiler and condenser, mixer, and recycle.

- Column convergence was achieved after many iterations (see Table 5).

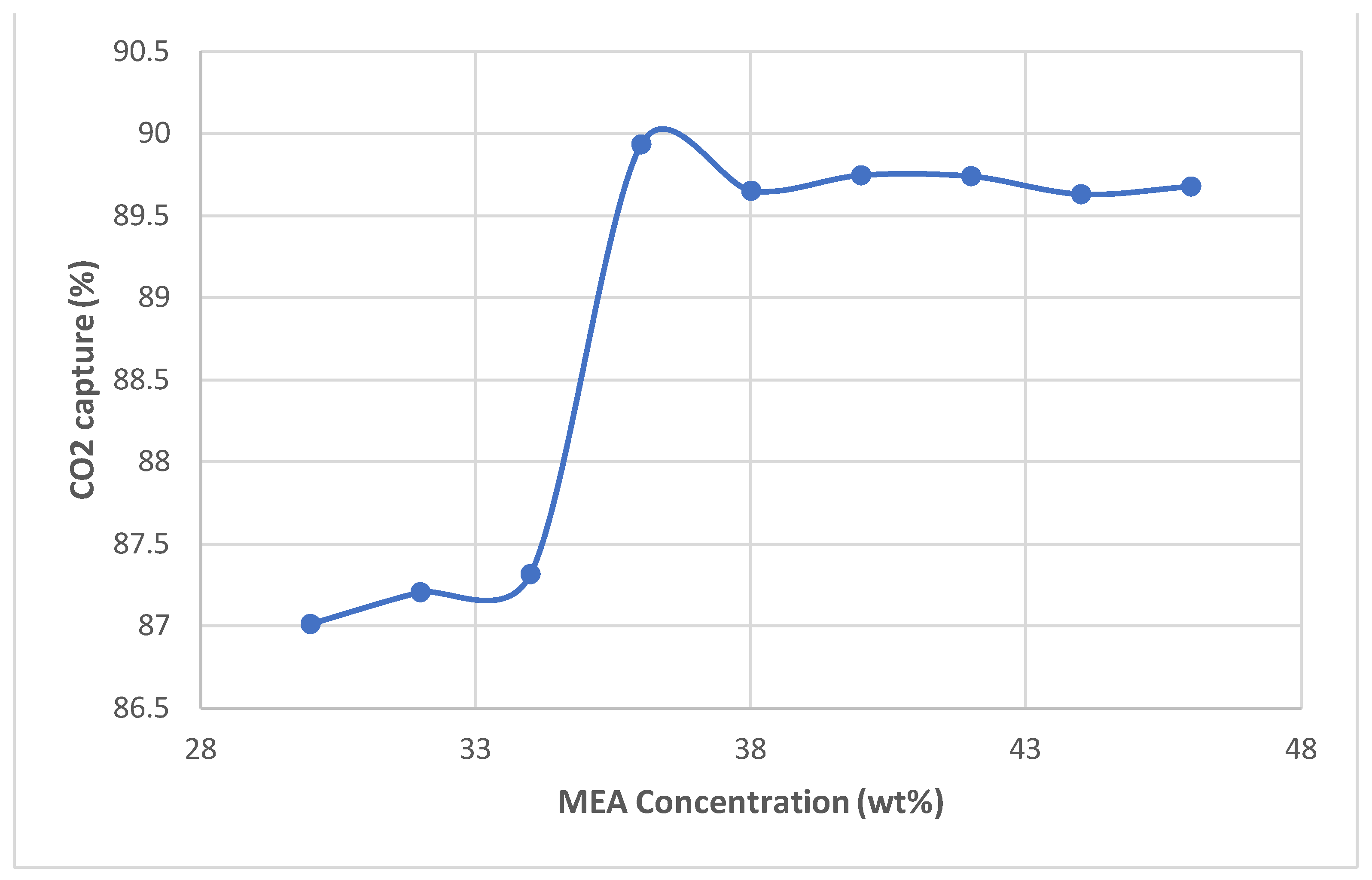

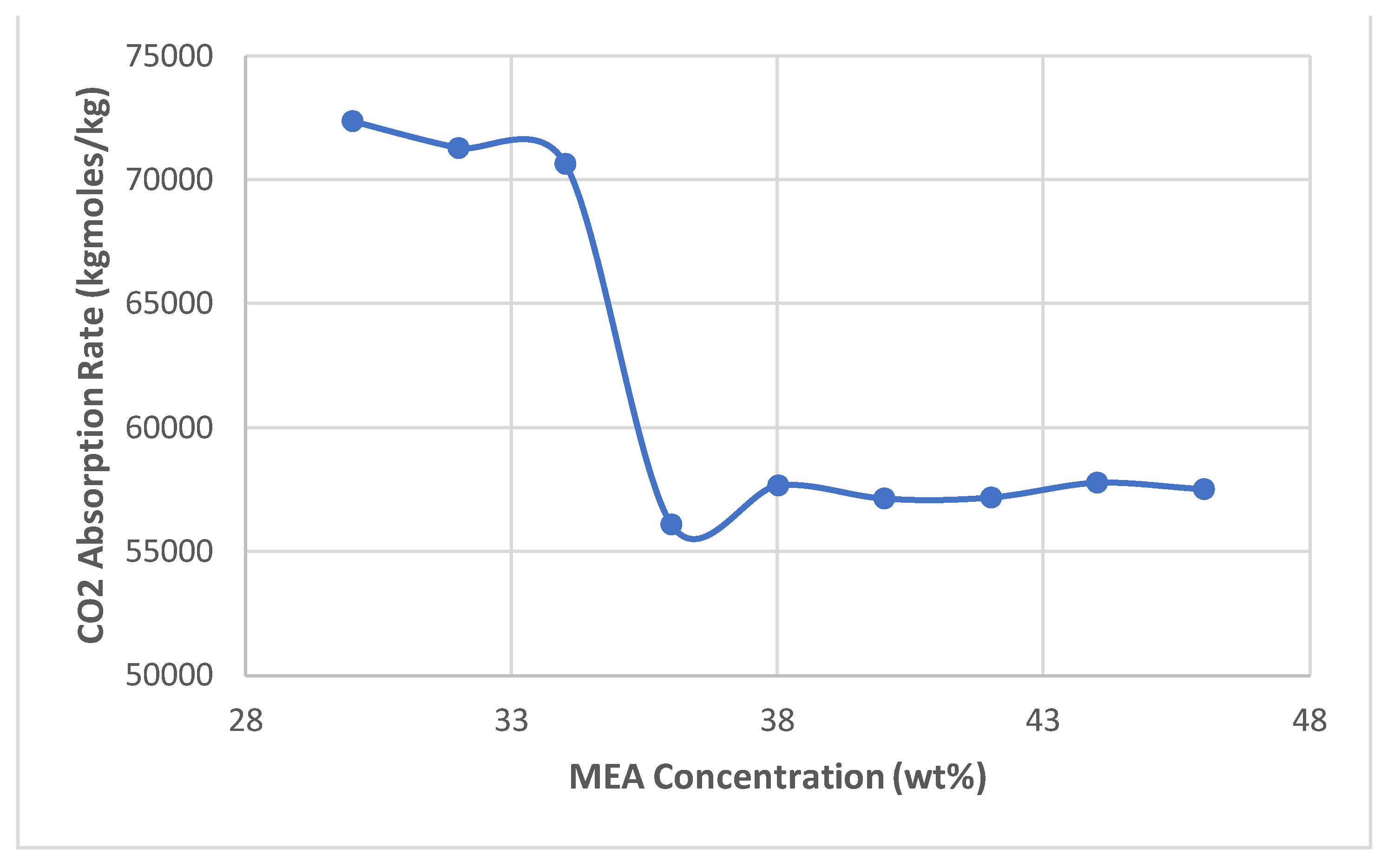

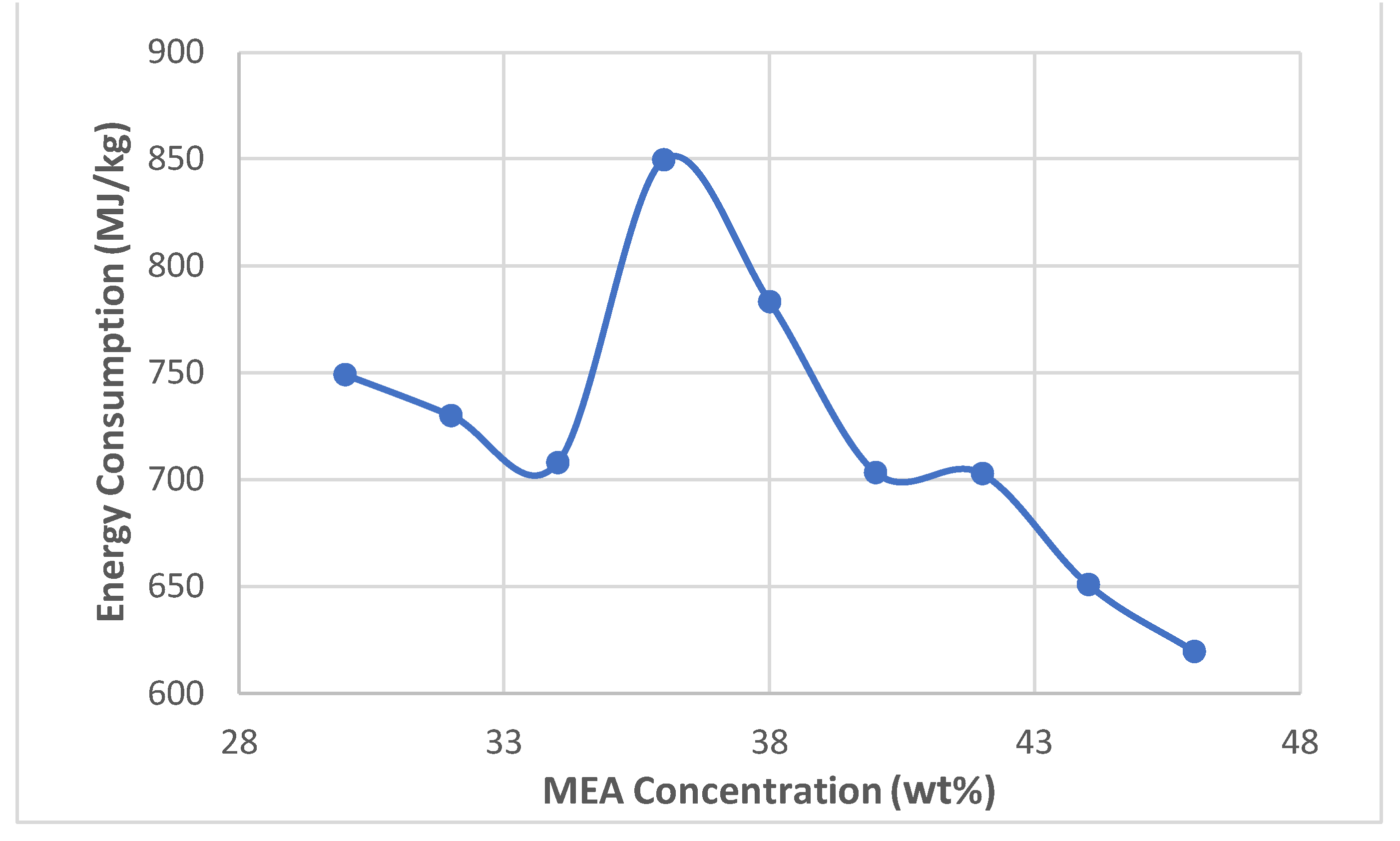

- Once the base case results were validated, the solvent concentrations were varied by 2 wt% and the simulation was run to collect 30 - 46 wt% data

- The calculations were made, and the obtained results were plotted in Excel.

- Using the existing simulation, two new parameters were chosen to vary, as the behavior at peak concentration showed potential.

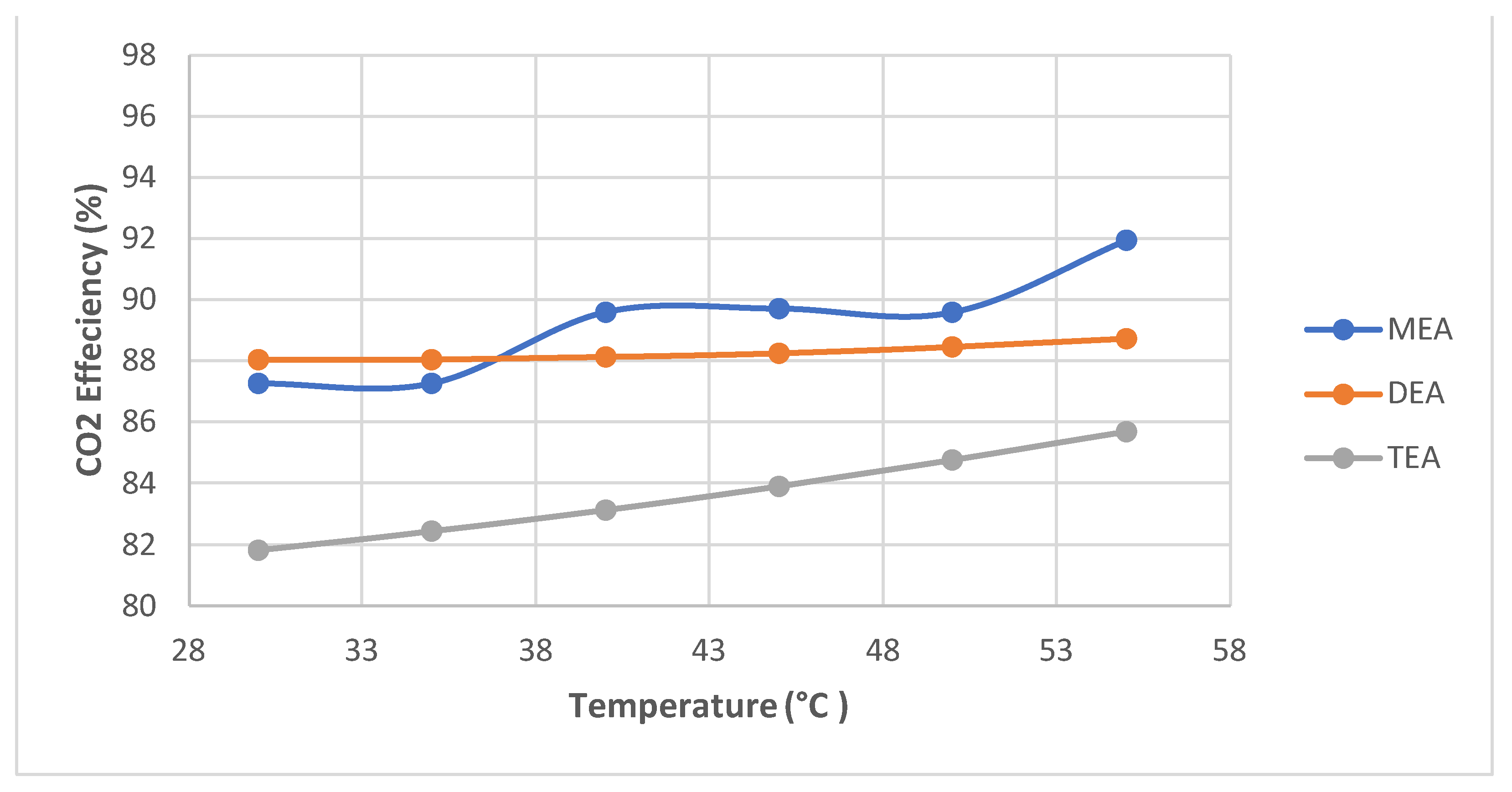

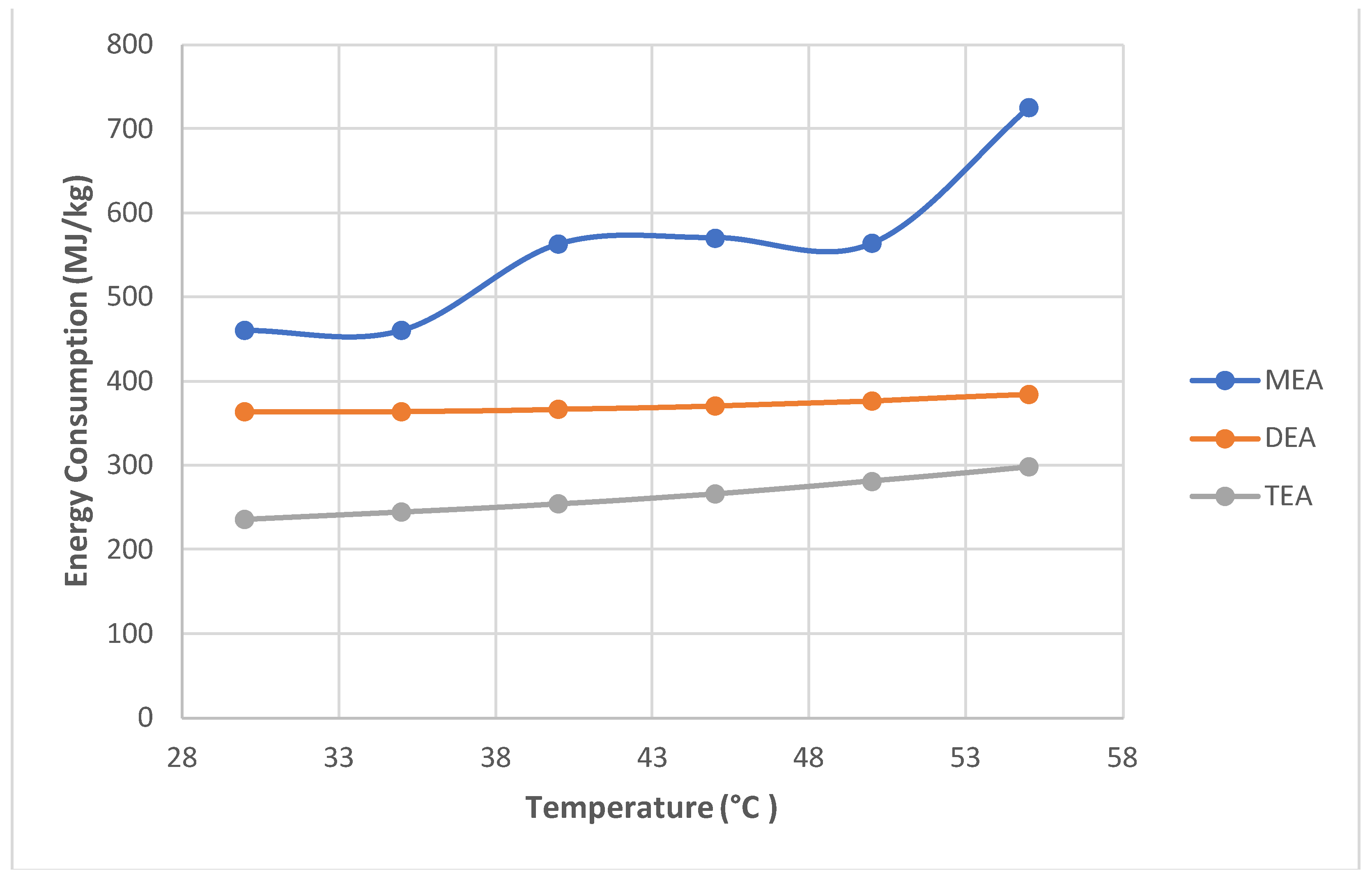

- The chosen parameter was the temperature (rising in 5 °C increments) of the solvent, within the limits ranging from 303 K to 328 K (30-55 °C) from Zhang and Chen [5]. In contrast, the maximum temperature was 80 °C, which is not simulated because corrosion and oxidation increase dramatically at this temperature, as shown in Fischer et al. [42].

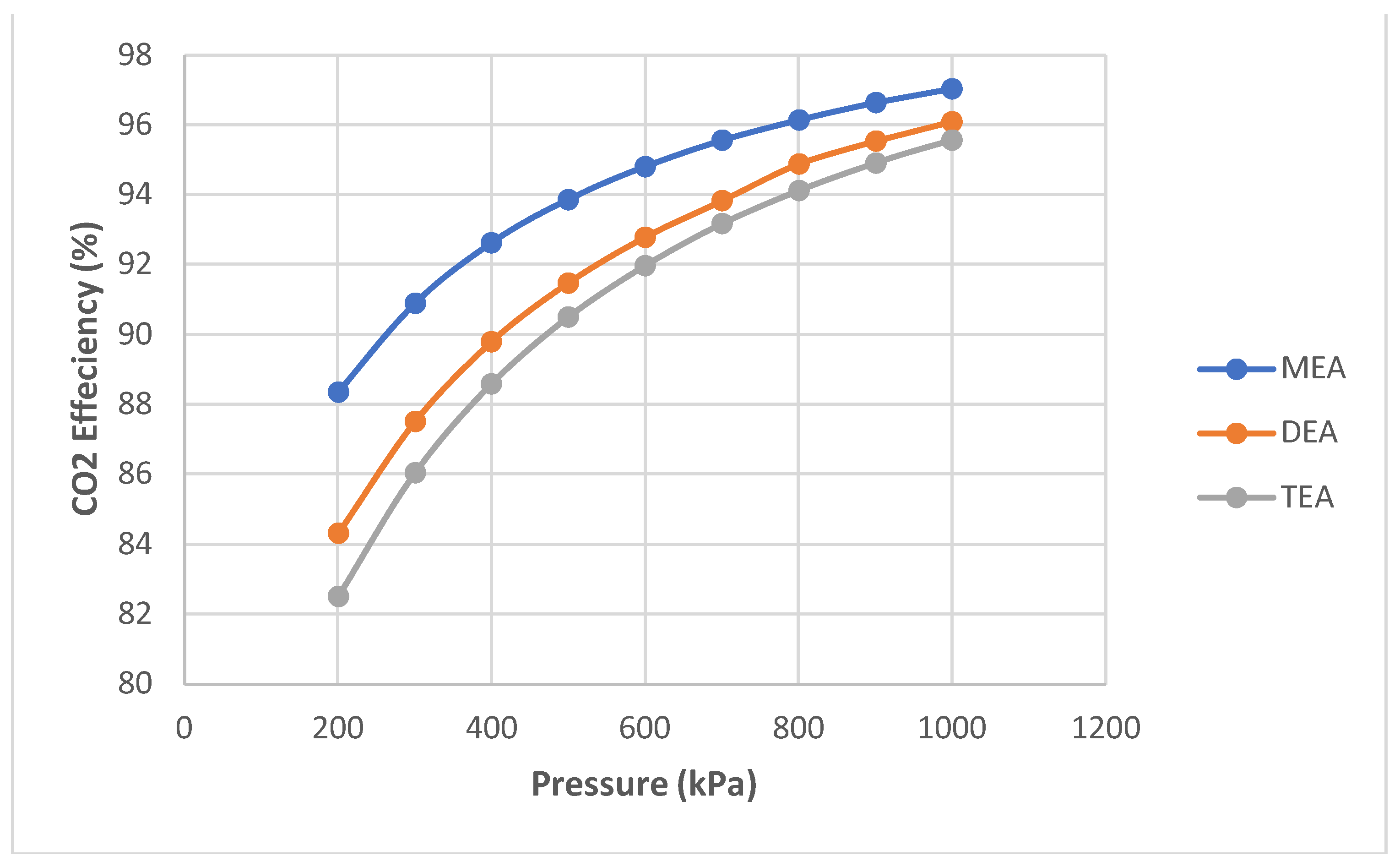

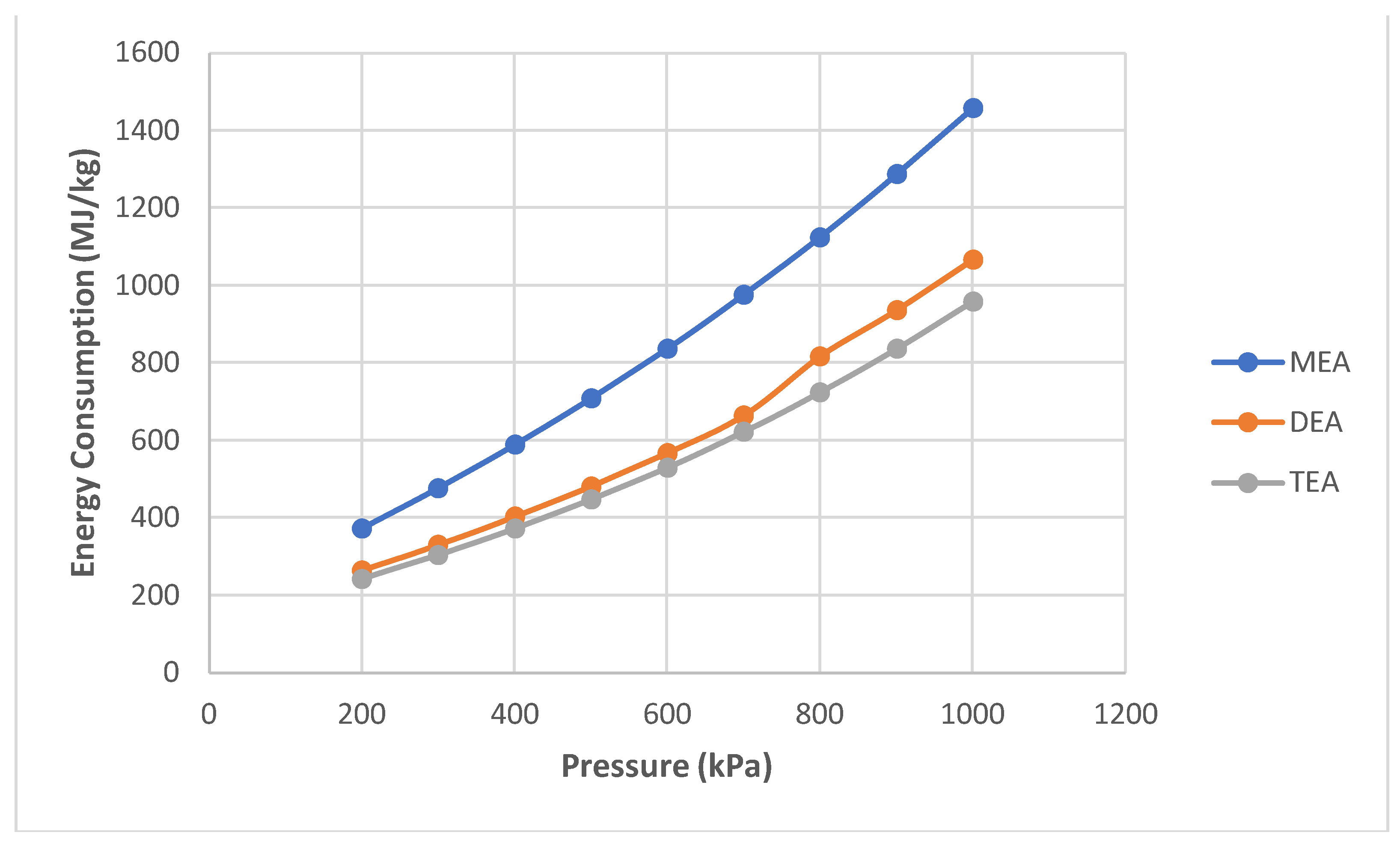

- Pressure was the second chosen parameter. It was simulated from 200 kPa to 1000 kPa in 100 kPa increments.

- A further simulation of the same configuration was performed. However, simulations to compare MEA with two other amines, DEA and TEA, were performed in separate flow sheets and are not shown for brevity. Pressure and temperature sensitivities were simulated in MEA.

- The obtained data were analyzed and discussed.

3.3. Convergence Chalenges

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Further Result and Discussion

5. Conclusions

- After 36 wt.%, all higher concentrations are constant and less than the optimum concentration for CO2 absorption efficiency.

- As equilibrium is reached, the absorption remains constant at higher concentrations as the capture rate falls.

- Despite the optimum MEA concentration of 36 wt.%, the highest energy consumption also resulted in the highest costs, so the optimum concentration also has higher costs.

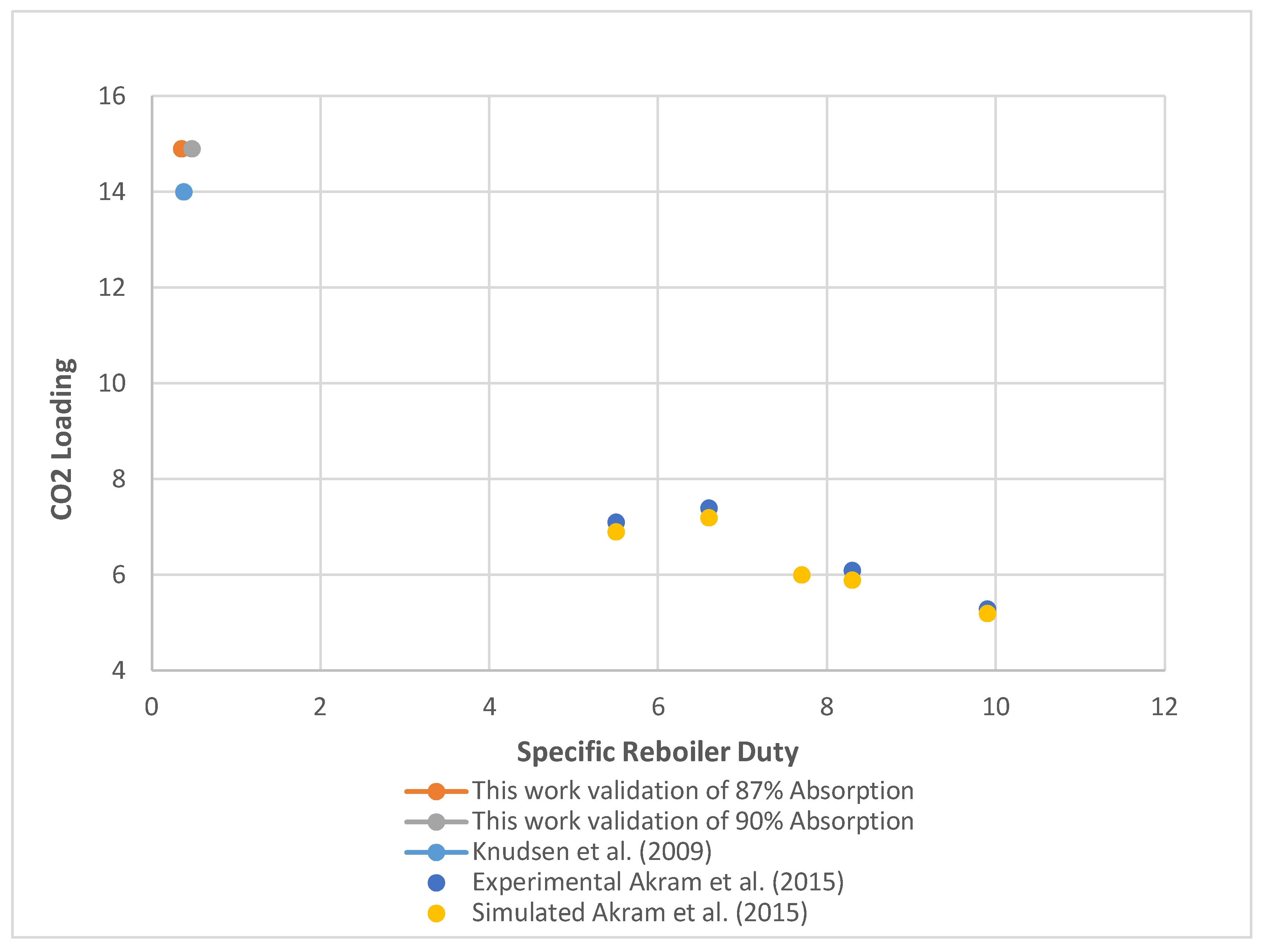

- The working simulation model confirmed agreement with literature values for the base case's reaction kinetics and absorption efficiency.

- In the simulated temperature and pressure ranges, MEA had the highest absorption (up to 97%) compared to DEA and TEA.

- Energy consumption increased as absorption increased with temperature and pressure.

- DEA and TEA require less energy than MEA to achieve similar results when operating at high pressures. Therefore, these fewer common amines are alternatives to MEA at higher operating pressures.

References

- Cousins, A.; Wardhaugh, L.T.; Feron, P.H.M. A Survey of Process Flow Sheet Modifications for Energy Efficient CO2 Capture from Flue Gases Using Chemical Absorption. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2011, 5, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirinik, M.; Ahmed, S.; Rahmanian, N. Comparative Techno-Economic Analysis of Carbon Capture Processes: Pre-Combustion, Post-Combustion, and Oxy-Fuel Combustion Operations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, C.; Tantikhajorngosol, P.; Sema, T.; Liang, Z.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P.; Liu, H. Comparative Desorption Energy Consumption of Post-Combustion CO2 Capture Integrated with Mechanical Vapor Recompression Technology. Sep Purif Technol 2022, 294, 121202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, A.S.; Olaleye, A.K.; Lee, J.G.M.; Wu, K.; Kim, D.; Shah, N.; Kolster, C.; Mac Dowell, N.; Wang, M.; Ramshaw, C.; et al. Carbon Capture. In The Water-Food-Energy Nexus; CRC Press, 2017; pp. 457–632.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.-C. Modeling CO2 Absorption and Desorption by Aqueous Monoethanolamine Solution with Aspen Rate-Based Model. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Cao Nhien, L.; Lee, M. Rate-Based Modeling and Assessment of an Amine-Based Acid Gas Removal Process through a Comprehensive Solvent Selection Procedure. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15, 6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfort, B.; Carrette, P.-L.; Bonnard, L. MEA 40% with Improved Oxidative Stability for CO2 Capture in Post-Combustion. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lawal, A.; Stephenson, P.; Sidders, J.; Ramshaw, C. Post-Combustion CO2 Capture with Chemical Absorption: A State-of-the-Art Review. Chemical engineering research and design 2011, 89, 1609–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi Kouzehkanan, S.M.; Hassani, E.; Feyzbar-Khalkhali-Nejad, F.; Oh, T.S. Calcium-Based Sorbent Carbonation at Low Temperature via Reactive Milling under CO2. Inorganics (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikita, H.; Asai, S.; Ishikawa, H.; Honda, M. The Kinetics of Reactions of Carbon Dioxide with Monoethanolamine, Diethanolamine and Triethanolamine by a Rapid Mixing Method. The Chemical Engineering Journal 1977, 13, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsent, B.R.W.; Pearson, L.; Roughton, F.J.W. The Kinetics of Combination of Carbon Dioxide with Hydroxide Ions. Transactions of the Faraday Society 1956, 52, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.-C. Modeling CO2 Absorption and Desorption by Aqueous Monoethanolamine Solution with Aspen Rate-Based Model. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, B.S.; Rachman, I.; Ikhlas, N.; Kurniawan, S.B.; Miftahadi, M.F.; Matsumoto, T. A Comprehensive Review of Domestic-Open Waste Burning: Recent Trends, Methodology Comparison, and Factors Assessment. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 2022, 24, 1633–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kolawole, T.; Attidekou, P. Carbon Capture from a Simulated Flue Gas Using a Rotating Packed Bed Adsorber and Mono Ethanol Amine (MEA). Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 1834–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Yu, H.; Liang, Z.; Luo, X. Analysis of the Reduction of Energy Cost by Using MEA-MDEA-PZ Solvent for Post-Combustion Carbon Dioxide Capture (PCC). Appl Energy 2017, 205, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariki, S.G.; Movahedirad, S. ; others Comparative Analysis of Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Models: CO2 Loading in MDEA and Blended MDEA/PZ Solvents. Fuel 2024, 357, 129667. [Google Scholar]

- Nessi, E.; Papadopoulos, A.I.; Seferlis, P. A Review of Research Facilities, Pilot and Commercial Plants for Solvent-Based Post-Combustion CO2 Capture: Packed Bed, Phase-Change and Rotating Processes. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2021, 111, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltman, K.; Singh, B.; Hertwich, E.G. Human and Environmental Impact Assessment of Postcombustion CO2 Capture Focusing on Emissions from Amine-Based Scrubbing Solvents to Air. Environ Sci Technol 2010, 44, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mores, P.; Scenna, N.; Mussati, S. Post-Combustion CO2 Capture Process: Equilibrium Stage Mathematical Model of the Chemical Absorption of CO2 into Monoethanolamine (MEA) Aqueous Solution. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2011, 89, 1587–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Yang, L.; Du, X.; Yang, Y. CO2 Capture Using MEA (Monoethanolamine) Aqueous Solution in Coal-Fired Power Plants: Modeling and Optimization of the Absorbing Columns. Energy 2016, 109, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Hou, Z.; Fang, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, T. Evolution of CCUS Technologies Using LDA Topic Model and Derwent Patent Data. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.; Gladis, A.; Jørgensen, J.B.; Thomsen, K.; Von Solms, N.; Fosbøl, P.L. Dynamic Operation and Simulation of Post-Combustion CO2 Capture. Energy Procedia 2016, 86, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, R.H.; Dingman, J.C.; Cronin, D.B.; Browning, G.J. Density and Viscosity of Some Partially Carbonated Aqueous Alkanolamine Solutions and Their Blends. J Chem Eng Data 1998, 43, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Luberti, M.; Liu, Z.; Brandani, S. Process Simulation of Aqueous MEA Plants for Post-Combustion Capture from Coal-Fired Power Plants. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvamsdal, H.M.; Chikukwa, A.; Hillestad, M.; Zakeri, A.; Einbu, A. A Comparison of Different Parameter Correlation Models and the Validation of an MEA-Based Absorber Model. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sharma, M.; Khalilpour, R.; Abbas, A. Optimal Operation of Solvent-Based Post-Combustion Carbon Capture Processes with Reduced Models. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A. Design and Operation Optimisation of a MEA-Based CO2 Capture Unit, M. Sc. thesis). Chemical Engineering Department, Instituto Superior Tecnico~…, 2014.

- Im, D.; Jung, H.; Lee, J.H. Modeling, Simulation and Optimization of the Rotating Packed Bed (RPB) Absorber and Stripper for MEA-Based Carbon Capture. Comput Chem Eng 2020, 143, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, A.; Wang, M.; Stephenson, P.; Koumpouras, G.; Yeung, H. Dynamic Modelling and Analysis of Post-Combustion CO2 Chemical Absorption Process for Coal-Fired Power Plants. Fuel 2010, 89, 2791–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Knuutila, H.K.; Gu, S. ASPEN PLUS Simulation Model for CO2 Removal with MEA: Validation of Desorption Model with Experimental Data. J Environ Chem Eng 2017, 5, 4693–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moioli, S.; Nagy, T.; Langé, S.; Pellegrini, L.A.; Mizsey, P. Simulation Model Evaluation of CO2 Capture by Aqueous MEA Scrubbing for Heat Requirement Analyses. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Kim, J.; Jung, J.; Lee, C.S.; Han, C. Modeling and Simulation of CO2 Capture Process for Coal-Based Power Plant Using Amine Solvent in South Korea. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kum, J.; Cho, S.; Ko, Y.; Lee, C.-H. Blended-Amine CO2 Capture Process without Stripper for High-Pressure Syngas. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 150226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, J. Heat Integration of Natural Gas Combined Cycle Power Plant Integrated with Post-Combustion CO2 Capture and Compression. Fuel 2015, 151, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moioli, S.; Pellegrini, L.A.; Gamba, S. Simulation of CO2 Capture by MEA Scrubbing with a Rate-Based Model. Procedia Eng 2012, 42, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, M. Improving Prediction Accuracy of a Rate-Based Model of an MEA-Based Carbon Capture Process for Large-Scale Commercial Deployment. Engineering 2017, 3, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ErikØi, L. Comparison of Aspen HYSYS and Aspen Plus Simulation of CO2 Absorption into MEA from Atmospheric Gas. Energy Procedia 2012, 23, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øi, L.E.; Bråthen, T.; Berg, C.; Brekne, S.K.; Flatin, M.; Johnsen, R.; Moen, I.G.; Thomassen, E. Optimization of Configurations for Amine Based CO2 Absorption Using Aspen HYSYS. Energy Procedia 2014, 51, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, F.; Gale, W.F.; Akram, M.; Hughes, K.J.; Pourkashanian, M. Performance Evaluation and Optimisation of Post Combustion CO2 Capture Processes for Natural Gas Applications at Pilot Scale via a Verified Rate-Based Model. International journal of greenhouse gas control 2016, 53, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, U.; Akram, M.; Font-Palma, C.; Ingham, D.B.; Pourkashanian, M. Part-Load Performance of Direct-Firing and Co-Firing of Coal and Biomass in a Power Generation System Integrated with a CO2 Capture and Compression System. Fuel 2017, 210, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, M.; Rahmanian, N.; Hyatt, X.; Peletiri, S.P.; Nizami, A.-S. Energy Savings in CO2 Capture System through Intercooling Mechanism. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 3683–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian, N.; Rehan, M.; Sumani, A.; Nizami, A.-S. Effect of Packing Structure on CO2 Capturing Process. Chem Eng Trans 2018, 70, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Li, L.-X.; Zhang, L.-T.; Zeng, S.; Feng, C.; Chen, X.-X.; Zhou, H.-L.; Huang, X.-C. Elucidating Influences of Defects and Thermal Treatments on CO2 Capture of a Zr-Based Metal-Organic Framework. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 479, 147605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, S. Energy Landscape Analysis for Two-Phase Multi-Component NVT Flash Systems by Using ETD Type High-Index Saddle Dynamics. J Comput Phys 2023, 477, 111916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspentech Acid Gas Cleaning in Aspen HYSYS®.

- Øi, L.E. Aspen HYSYS Simulation of CO2 Removal by Amine Absorption from a Gas Based Power Plant. In Proceedings of the 48th Scandinavian Conference on Simulation and Modeling (SIMS 2007), Göteborg (Särö); 2007, 30-31 October 2007; pp. 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gervasi, J.; Dubois, L.; Thomas, D. Simulation of the Post-Combustion CO2 Capture with Aspen HysysTM Software: Study of Different Configurations of an Absorption-Regeneration Process for the Application to Cement Flue Gases. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.N.; Jensen, J.N.; Vilhelmsen, P.J.; Biede, O. Experience with CO2 Capture from Coal Flue Gas in Pilot-Scale. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series. Earth and Environmental Science; 2009; Vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Pouladi, B.; Hassankiadeh, M.N.; Behroozshad, F. Dynamic Simulation and Optimization of an Industrial-Scale Absorption Tower for CO2 Capturing from Ethane Gas. Energy reports 2016, 2, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Related Species | Reaction Direction | kj0 (kmol/m3. s) | εj (kJ/gmol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEACOO- | Forward | 3.02 × 1014 | 41.20 |

|

Reverse (Absorption) |

5.52 x 1023 | 69.05 | |

|

Reverse (Desorption) |

6.56 x 1027 | 95.24 | |

| HC | Forward | 1.33 x 1017 | 55.38 |

| Reverse | 6.63 x 1016 | 107.24 | |

| Forward | 3.02 x 1014 | 41.20 |

| Acid Gases | CO2, H2S, COS, CS2 |

| Hydrocarbons | CH4, C12 |

| Olefins | C2=, C3=, C4=, C5= |

| Mercaptans | M-Mercaptan, E-Mercaptan |

| Non-Hydrocarbons | H2, N2, O2, CO, H2O |

| Aromatics | C6H6, Toluene, e-C6H6, m-Xylene |

| Acid Gases | CO2, H2S, COS, CS2 |

| Hydrocarbons | CH4, C12 |

| Olefins | C2=, C3=, C4=, C5= |

| Amine Name | Concentration (Weight %) |

Acid Gas Partial Pressure (psia) |

T oF |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEA | 15-20 | 0.00001-300 | 77-260 |

| DEA | 25-35 | 0.00001-300 | 77-260 |

| TEA, MDEA | 35-50 | 0.00001-300 | 77-260 |

| DGADEA/MDEA | 45-65 | 0.00001-300 | 77-260 |

| 35-50 | 0.00001-300 | 77-260 | |

| MEA/MDEA | 35-50 | 0.00001-300 | 77-260 |

| Description | Value/Selection |

|---|---|

| Flue gas temperature | 51.1 °C |

| Flue gas pressure | 101.7 kPa |

| Flue gas flowrate | 85000 kmole/h |

| MEA temperature | 40 °C |

| MEA pressure | 101.3 kPa |

| MEA flowrate (1st iteration) | 120,000 kmole/h |

| CO2 in inlet | 14.9 mole-% |

| MEA in inlet (1st iteration) | 30 mass-% |

| Stages in absorber | 10 |

| Temperature of absorber | 40 °C |

| Pressure of absorber | 110 kPa |

| Murphree efficiency in the absorber | 0.25 |

| Pressure of desorber | 190 kPa |

| Reflux ratio of desorber | 0.3 |

| Murphree efficiency in the desorber | 1.0 |

| Temperature of reboiler | 120 °C |

| Properties Package | Amine Package |

| Reaction Direction | Zhang et al. (2013) kj0 (kmol/m3. s) |

Zhang etal. (2013) εj (kJ/gmol) |

HYSYS Simulation kj0 (kmol/m3. s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward (Absorption) | 3.02 x 1014 | 41.20 | 3.02 x 1014 |

| Reverse (Absorption) | 5.52 x 1023 | 69.05 | 5.52 x 1023 |

| Forward (Desorption) | 1.33 x 1017 | 55.38 | 1.33 x 1017 |

| Reverse (Desorption) | 6.63 x 1016 | 107.24 | 6.63 x 1016 |

| Reverse (Desorption) | 6.63 x 1016 | 107.24 | 6.63 x 1016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).