Submitted:

20 March 2024

Posted:

22 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

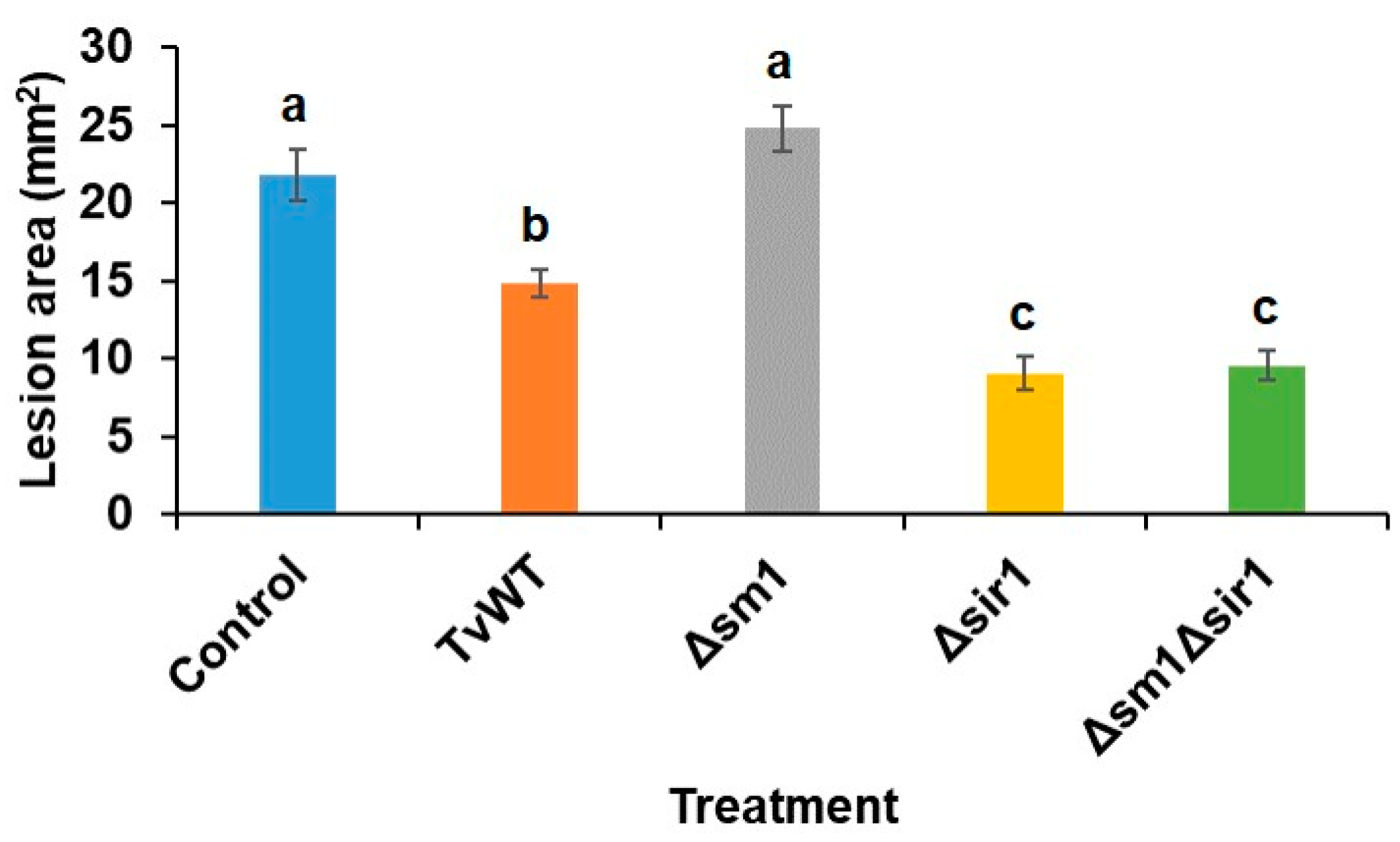

2.1. Colonization of Maize Roots by either Δsir1 or Δsm1Δsir1 Enhanced Greater Levels of ISR against C. Graminicola

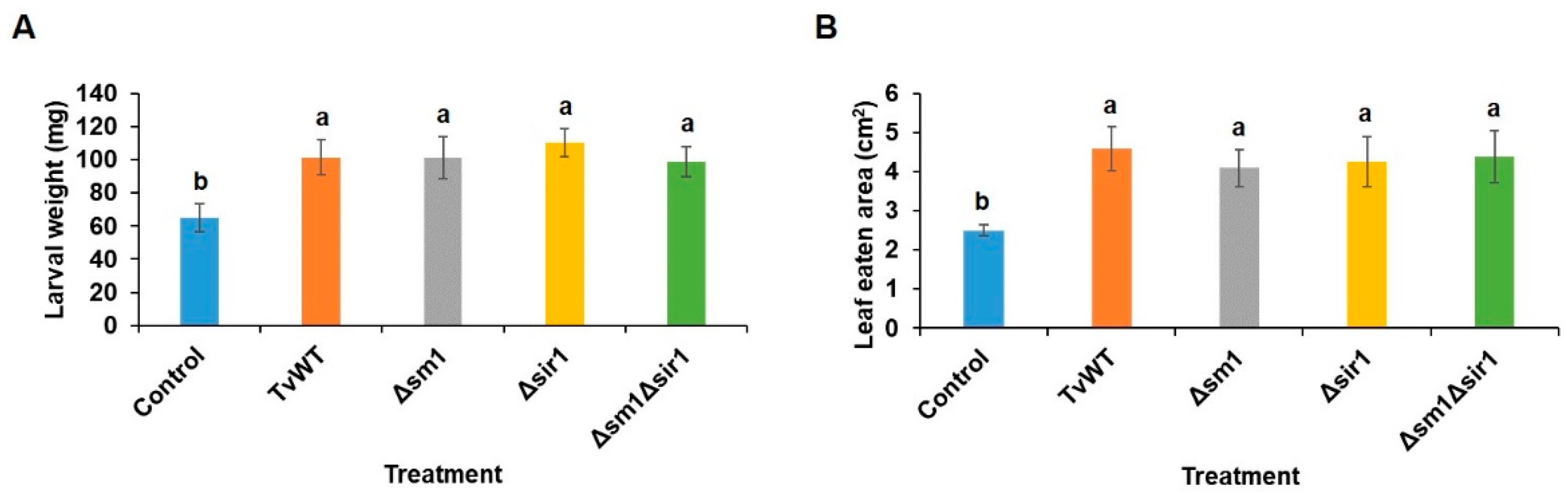

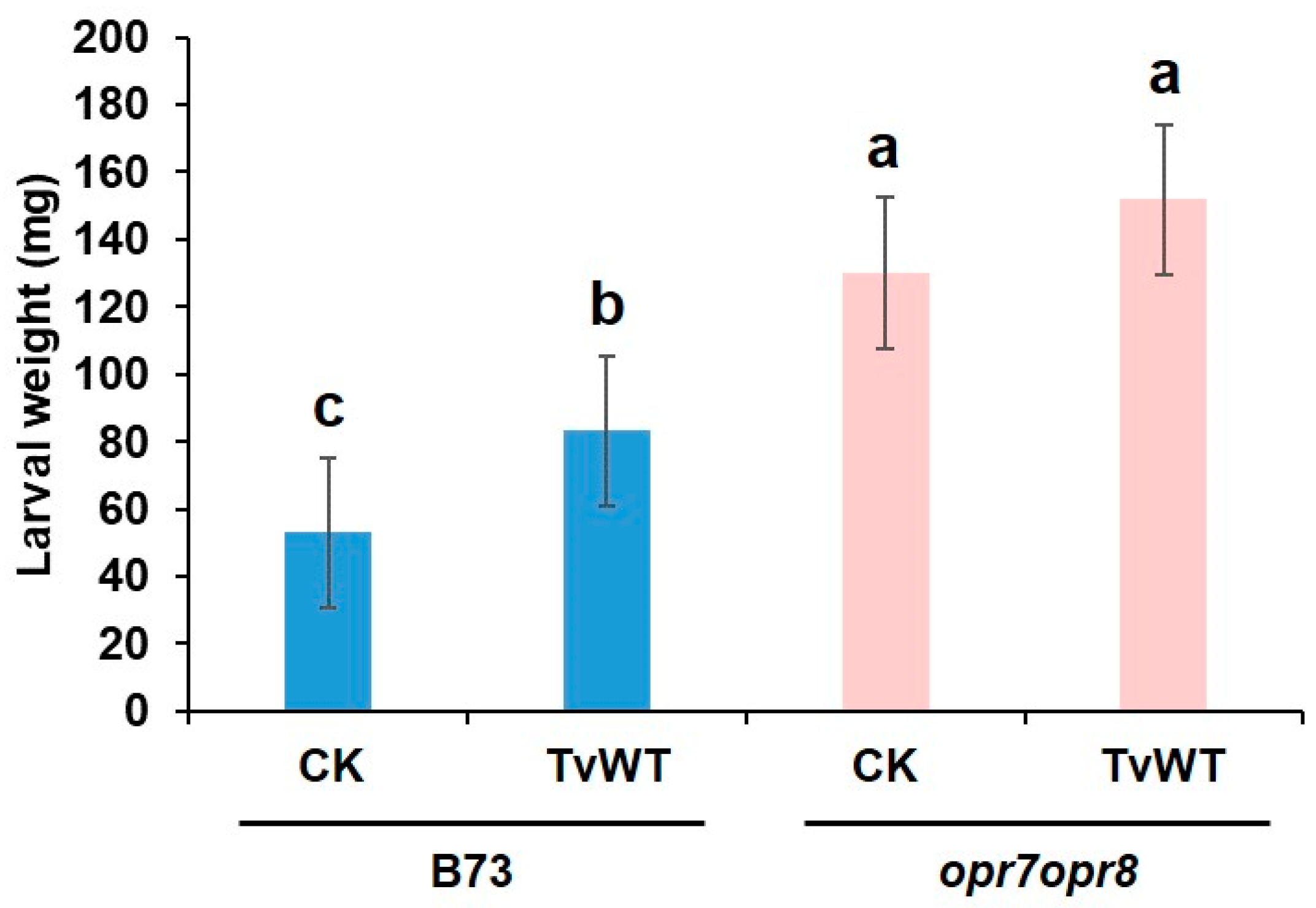

2.2. T. virens Colonization Suppressed Insect Defense

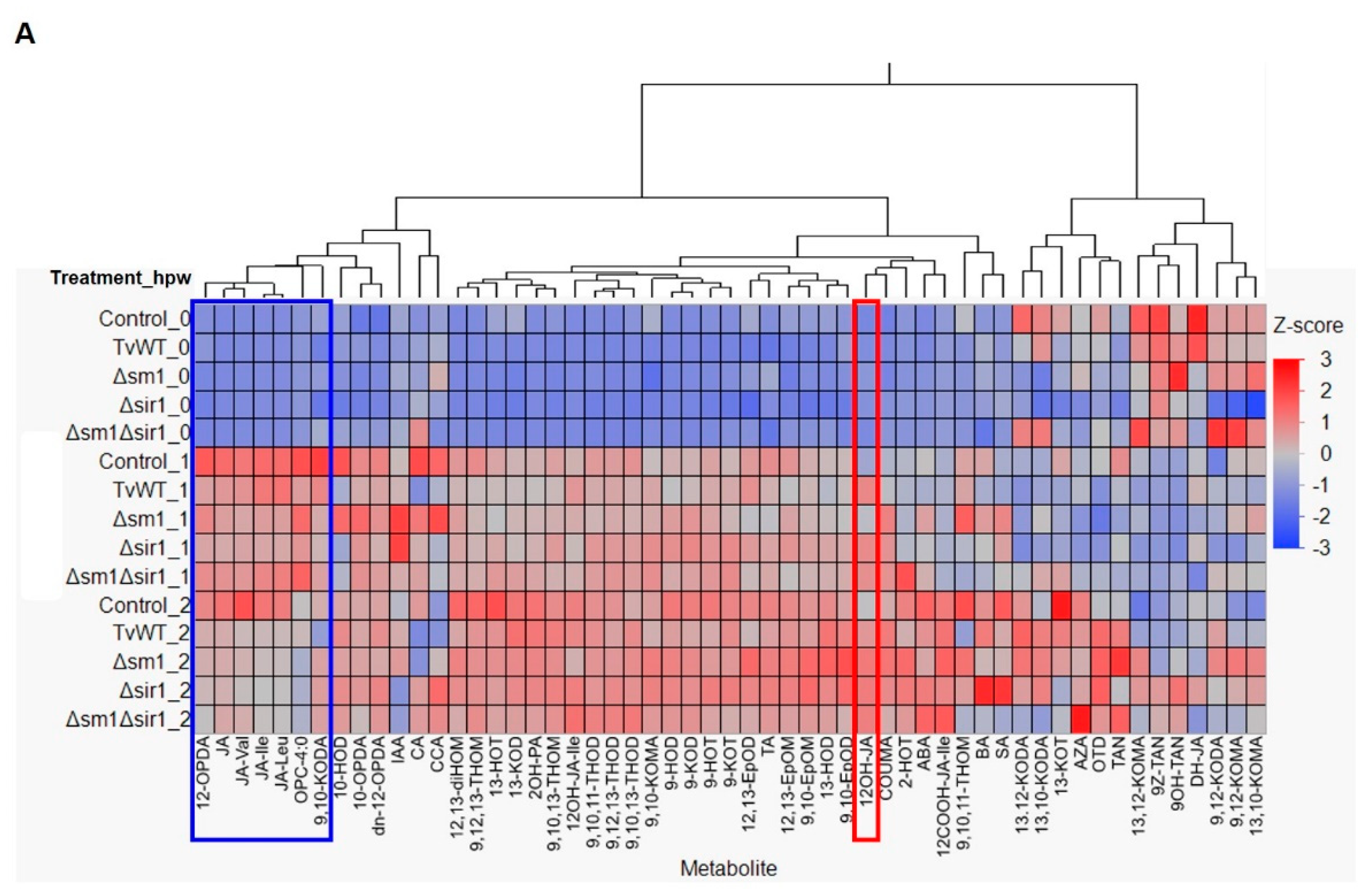

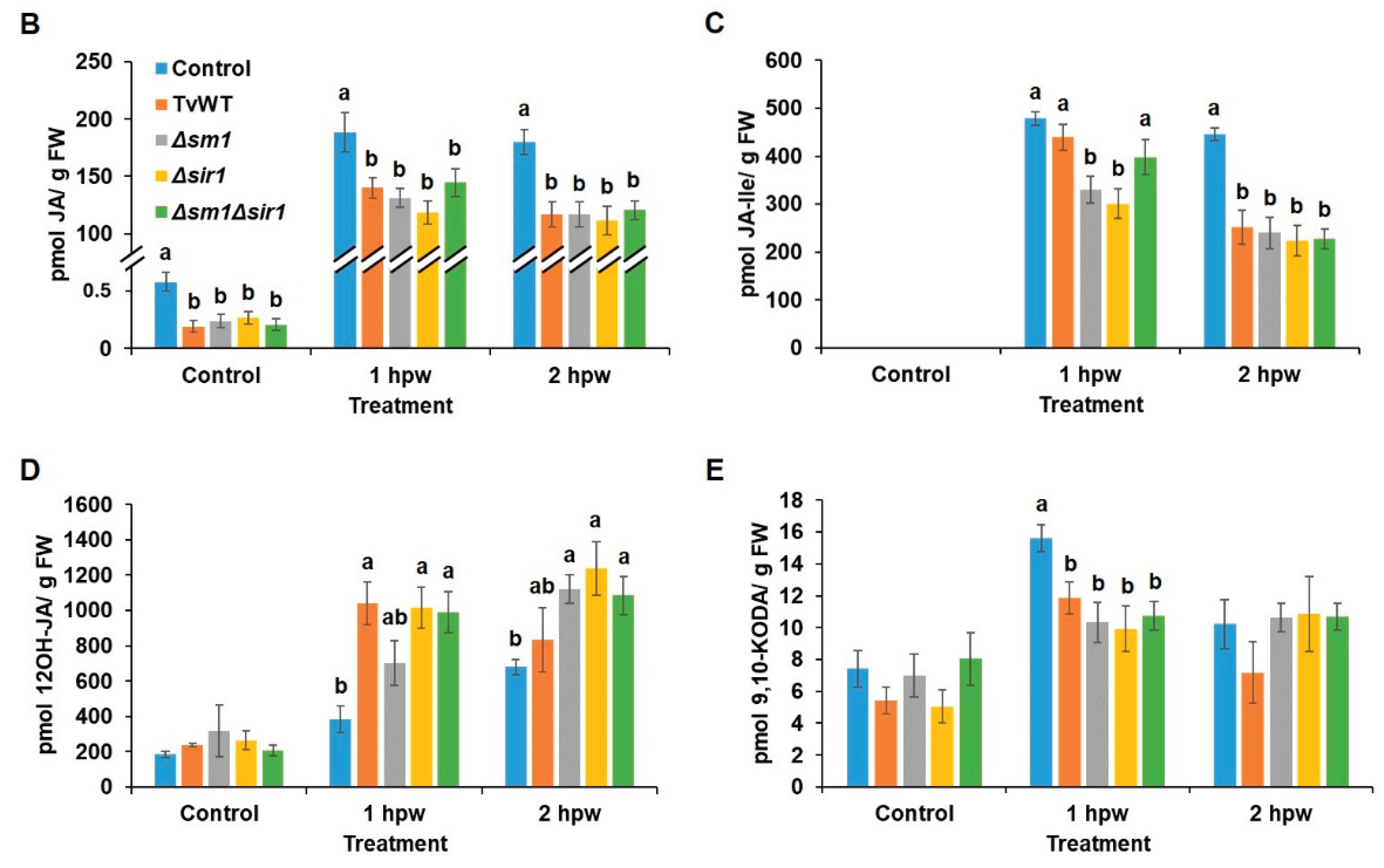

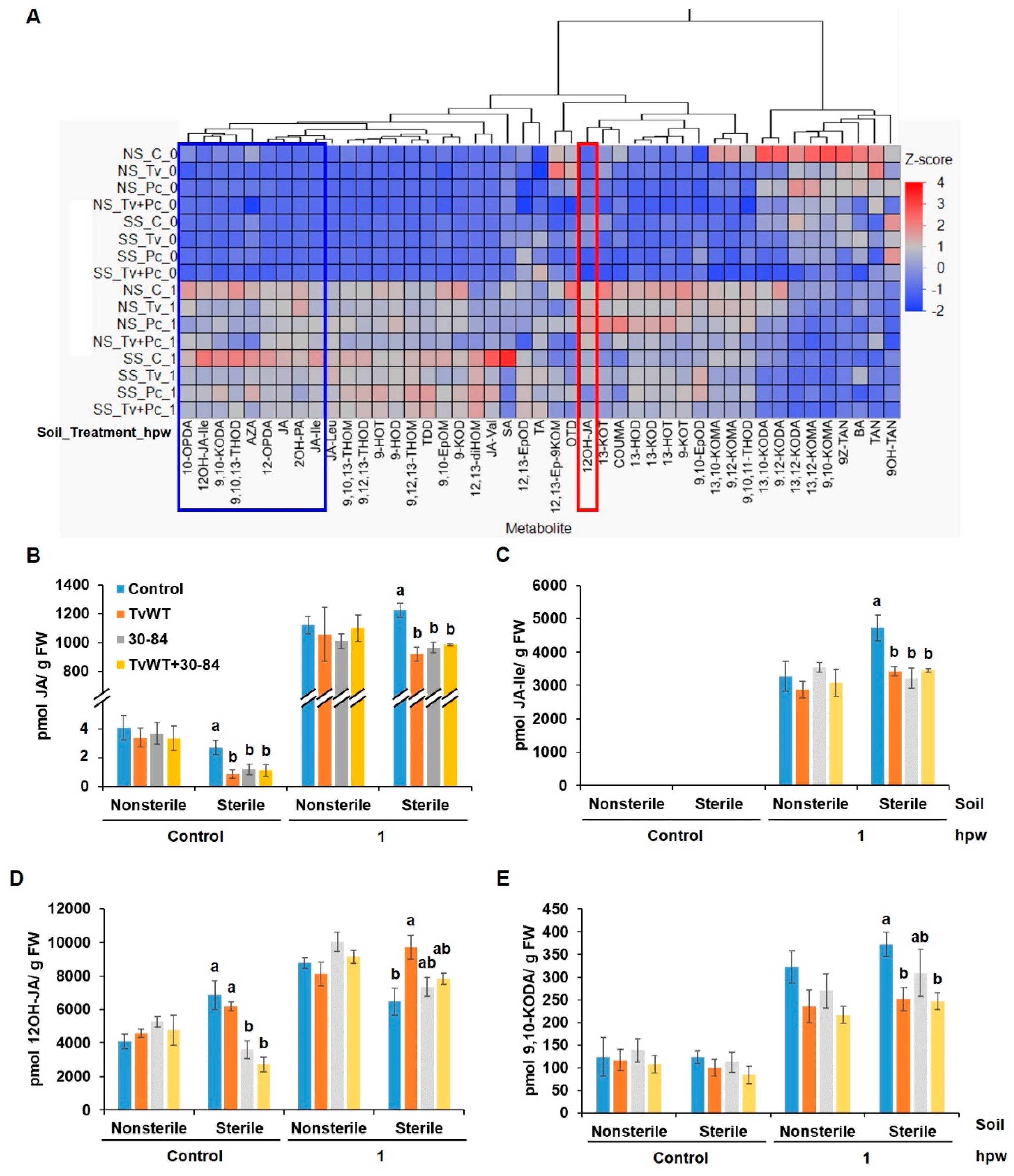

2.3. T. virens Treatment Reduced Wound-Induced JA Accumulation by Suppressing Biosynthesis and Enhancing Catabolism

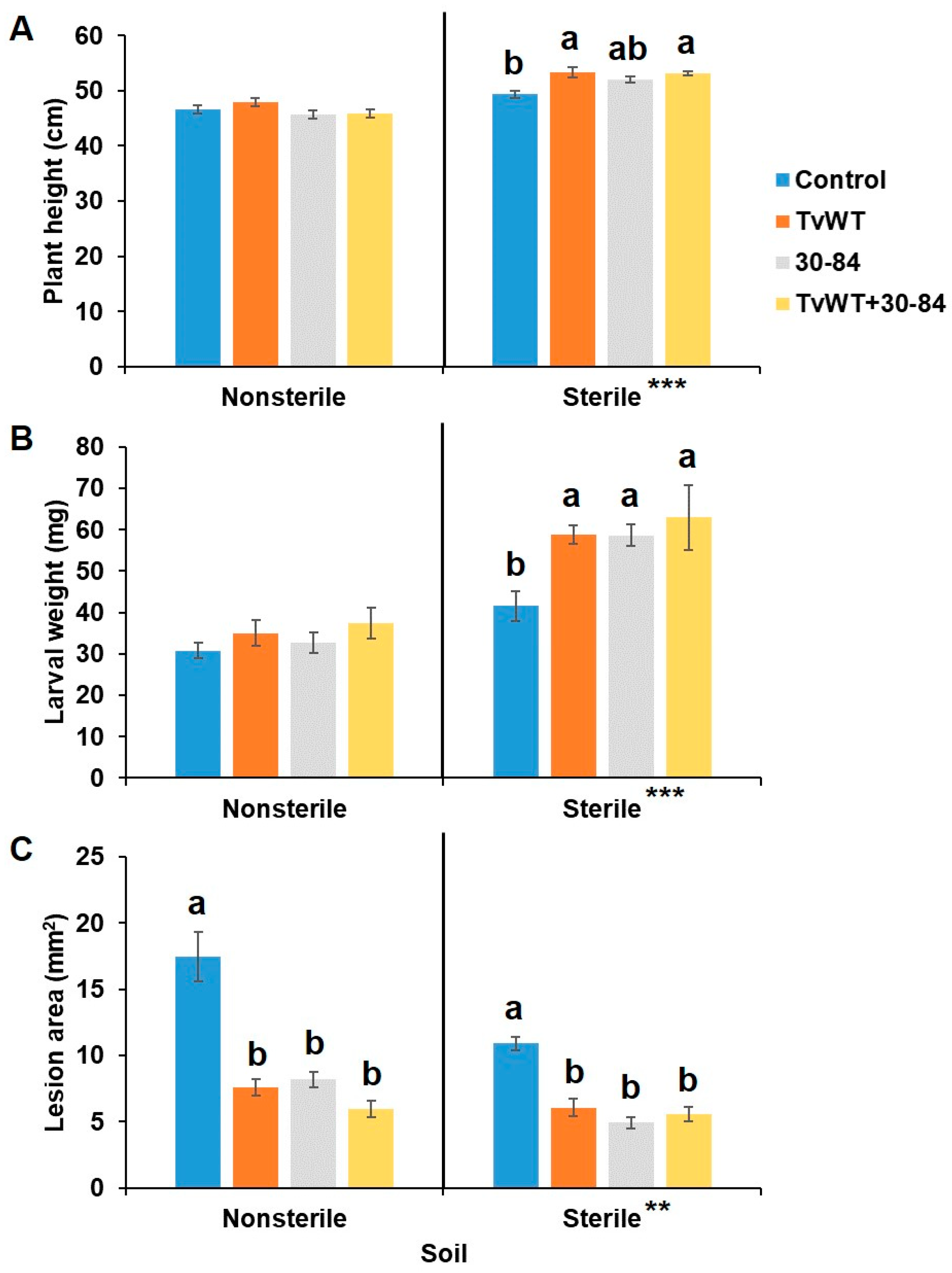

2.4. T. virens and P. chlororaphis Colonization Enhanced Growth but Suppressed Insect Defense against FAW in Sterile Soil While Increasing Resistance to C. graminicola in both Sterile and Nonsterile Soil

2.5. T. virens and P. chlororaphis 30-84 Colonization Reduced Wound-Induced JA Accumulation by Suppressing Biosynthesis and Enhancing Catabolism in Plants Grown in Sterile Soil

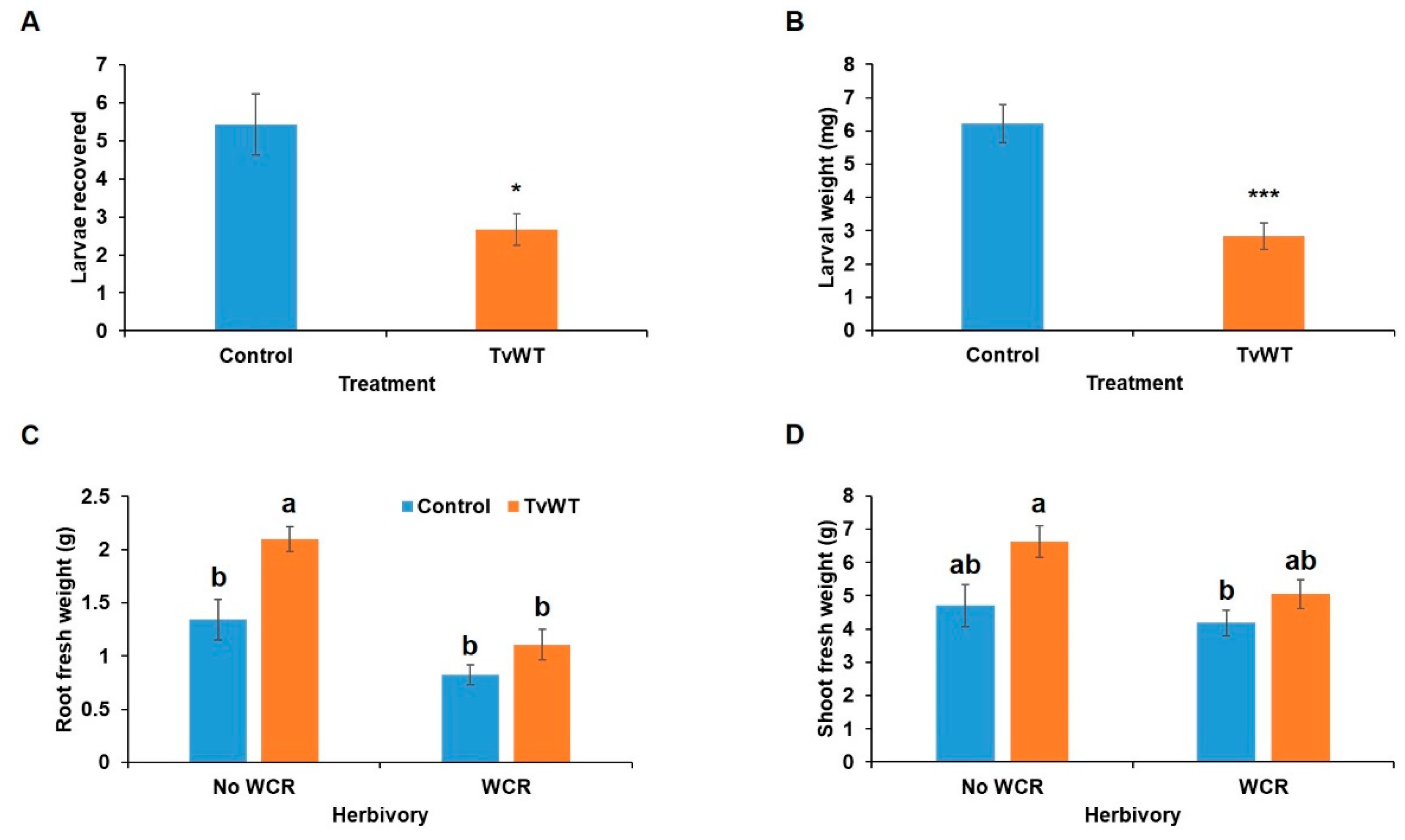

2.6. T. virens Colonization Suppressed WCR Larval Survival and Weight Gain

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant, Growth Medium, and Plant-Beneficial Inoculants

4.2. Anthracnose Leaf Blight Assay

4.3. Fall Armyworm Assay

4.4. Oxylipin Profiling of Wounded Leaf Tissue

4.5. Western Corn Rootworm Bioassays

4.6. Statistical Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B. M. , Global maize production, consumption and trade: trends and R&D implications. Food Security 2022, 14(5), 1295–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S. J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A., The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nature ecology & evolution 2019, 3 (3), 430-439.

- Belisário, R.; Robertson, A. E.; Vaillancourt, L. J. , Maize Anthracnose Stalk Rot in the Genomic Era. Plant Disease 2022, 106(9), 2281–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergstrom, G. C.; Nicholson, R. L. , The Biology of Corn Anthracnose: Knowledge to Exploit for Improved Management. Plant Disease 1999, 83(7), 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J. A. L.; Pretorius, Z. A.; Hammond-Kosack, K. E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P. D.; Rudd, J. J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; Foster, G. D. , The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Molecular plant pathology 2012, 13(4), 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenis, M. B. , Giovanni; Biondi, Antonio; Calatayud, Paul-André; Day, Roger; Desneux, Nicolas; Harrison, Rhett D; Kriticos, Darren; Rwomushana, Ivan; van den Berg, Johnnie; Verheggen, François; Zhang, Yong-Jun; Agboyi, Lakpo Koku; Ahissou, Régis Besmer; Ba, Malick N; Wu, Kongming, Invasiveness, biology, ecology, and management of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Entomologia Generalis 2023, 43(2), 55. [Google Scholar]

- Overton, K.; Maino, J. L.; Day, R.; Umina, P. A.; Bett, B.; Carnovale, D.; Ekesi, S.; Meagher, R.; Reynolds, O. L. , Global crop impacts, yield losses and action thresholds for fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda): A review. Crop Protection 2021, 145, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. E.; Sappington, T. W.; Miller, N. J.; Moeser, J.; Bohn, M. O. , Adaptation and invasiveness of western corn rootworm: intensifying research on a worsening pest. Annu Rev Entomol 2009, 54, 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlington, M.; Reinders, J. D.; Sethi, A.; Lu, A. L.; Ramaseshadri, P.; Fischer, J. R.; Boeckman, C. J.; Petrick, J. S.; Roper, J. M.; Narva, K. E.; Vélez, A. M. , RNAi for Western Corn Rootworm Management: Lessons Learned, Challenges, and Future Directions. Insects 2022, 13 (1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, S.; Smith, D. , Has resistance taken root in US corn fields? Demand for insect control. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2018, 100(4), 1136–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyeraj, A.; Szalai, M.; Pálinkás, Z.; Edwards, C. R.; Kiss, J. , Effects of adult western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte, Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) silk feeding on yield parameters of sweet maize. Crop Protection 2021, 140, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, Z.; Christensen, S. A.; Yan, Y.; He, Y.; Borrego, E.; Kolomiets, M. V. , Green leaf volatiles and jasmonic acid enhance susceptibility to anthracnose diseases caused by Colletotrichum graminicola in maize. Molecular plant pathology 2020, 21(5), 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P. C.; Tate, M.; Berg-Falloure, K. M.; Christensen, S. A.; Zhang, J.; Schirawski, J.; Meeley, R.; Kolomiets, M. V. , A non-JA producing oxophytodienoate reductase functions in salicylic acid-mediated antagonism with jasmonic acid during pathogen attack. Molecular plant pathology 2023, 24(7), 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Christensen, S.; Isakeit, T.; Engelberth, J.; Meeley, R.; Hayward, A.; Emery, R. J.; Kolomiets, M. V. , Disruption of OPR7 and OPR8 reveals the versatile functions of jasmonic acid in maize development and defense. Plant Cell 2012, 24(4), 1420–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S. A.; Nemchenko, A.; Borrego, E.; Murray, I.; Sobhy, I. S.; Bosak, L.; DeBlasio, S.; Erb, M.; Robert, C. A.; Vaughn, K. A.; Herrfurth, C.; Tumlinson, J.; Feussner, I.; Jackson, D.; Turlings, T. C.; Engelberth, J.; Nansen, C.; Meeley, R.; Kolomiets, M. V. , The maize lipoxygenase, ZmLOX10, mediates green leaf volatile, jasmonate and herbivore-induced plant volatile production for defense against insect attack. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 2013, 74 (1), 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P. C.; Grunseich, J. M.; Berg-Falloure, K. M.; Tolley, J. P.; Koiwa, H.; Bernal, J. S.; Kolomiets, M. V. , Maize OPR2 and LOX10 Mediate Defense against Fall Armyworm and Western Corn Rootworm by Tissue-Specific Regulation of Jasmonic Acid and Ketol Metabolism. Genes 2023, 14(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castano-Duque, L.; Loades, K. W.; Tooker, J. F.; Brown, K. M.; Paul Williams, W.; Luthe, D. S., A Maize Inbred Exhibits Resistance Against Western Corn Rootwoorm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera. Journal of chemical ecology 2017, 43 (11-12), 1109-1123.

- Köhl, J.; Kolnaar, R.; Ravensberg, W. J. , Mode of Action of Microbial Biological Control Agents Against Plant Diseases: Relevance Beyond Efficacy. Frontiers in plant science 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiénébo, E. O.; Harrison, K.; Abo, K.; Brou, Y. C.; Pierson, L. S., 3rd; Tamborindeguy, C.; Pierson, E. A.; Levy, J. G., Mycorrhization Mitigates Disease Caused by "Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum" in Tomato. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 8 (11).

- El-Saadony, M. T.; Saad, A. M.; Soliman, S. M.; Salem, H. M.; Ahmed, A. I.; Mahmood, M.; El-Tahan, A. M.; Ebrahim, A. A. M.; Abd El-Mageed, T. A.; Negm, S. H.; Selim, S.; Babalghith, A. O.; Elrys, A. S.; El-Tarabily, K. A.; AbuQamar, S. F. , Plant growth-promoting microorganisms as biocontrol agents of plant diseases: Mechanisms, challenges and future perspectives. Frontiers in plant science 2022, 13, 923880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zin, N. A.; Badaluddin, N. A. , Biological functions of Trichoderma spp. for agriculture applications. Annals of Agricultural Sciences 2020, 65(2), 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyśkiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J., Trichoderma: The Current Status of Its Application in Agriculture for the Biocontrol of Fungal Phytopathogens and Stimulation of Plant Growth. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23 (4).

- Yao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, M.; Ruan, J.; Chen, J. , Trichoderma and its role in biological control of plant fungal and nematode disease. Frontiers in microbiology 2023, 14, 1160551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A. J.; Kim, Y. C. , Insights into plant-beneficial traits of probiotic Pseudomonas chlororaphis isolates. Journal of medical microbiology 2020, 69(3), 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H. A.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.; del-Val, E.; Larsen, J. , The root endophytic fungus Trichoderma atroviride induces foliar herbivory resistance in maize plants. Applied Soil Ecology 2018, 124, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, J. , Trichoderma as biocontrol agent against pests: New uses for a mycoparasite. Biological Control 2021, 159, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djonović, S.; Pozo, M. J.; Dangott, L. J.; Howell, C. R.; Kenerley, C. M., Sm1, a proteinaceous elicitor secreted by the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma virens induces plant defense responses and systemic resistance. Molecular plant-microbe interactions : MPMI 2006, 19 (8), 838-53.

- Djonovic, S.; Vargas, W. A.; Kolomiets, M. V.; Horndeski, M.; Wiest, A.; Kenerley, C. M. , A proteinaceous elicitor Sm1 from the beneficial fungus Trichoderma virens is required for induced systemic resistance in maize. Plant physiology 2007, 145(3), 875–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamdan, N. L.; Shalaby, S.; Ziv, T.; Kenerley, C. M.; Horwitz, B. A., Secretome of Trichoderma interacting with maize roots: role in induced systemic resistance. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 2015, 14 (4), 1054-63.

- Wang, K. D.; Borrego, E. J.; Kenerley, C. M.; Kolomiets, M. V. , Oxylipins Other Than Jasmonic Acid Are Xylem-Resident Signals Regulating Systemic Resistance Induced by Trichoderma virens in Maize. Plant Cell 2020, 32(1), 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. A. A.; Najeeb, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Hou, J.; Liu, T. , Insights into the molecular mechanism of Trichoderma stimulating plant growth and immunity against phytopathogens. Physiologia plantarum 2023, 175(6), e14133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehbi, I.; Achemrk, O.; Ezzouggari, R.; El Jarroudi, M.; Mokrini, F.; Legrifi, I.; Belabess, Z.; Laasli, S. E.; Mazouz, H.; Lahlali, R., Beneficial Microorganisms as Bioprotectants against Foliar Diseases of Cereals: A Review. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 12 (24).

- Saldaña-Mendoza, S. A.; Pacios-Michelena, S.; Palacios-Ponce, A. S.; Chávez-González, M. L.; Aguilar, C. N., Trichoderma as a biological control agent: mechanisms of action, benefits for crops and development of formulations. World journal of microbiology & biotechnology 2023, 39 (10), 269.

- Yuan, P.; Borrego, E.; Park, Y. S.; Gorman, Z.; Huang, P. C.; Tolley, J.; Christensen, S. A.; Blanford, J.; Kilaru, A.; Meeley, R.; Koiwa, H.; Vidal, S.; Huffaker, A.; Schmelz, E.; Kolomiets, M. V. , 9,10-KODA, an α-ketol produced by the tonoplast-localized 9-lipoxygenase ZmLOX5, plays a signaling role in maize defense against insect herbivory. Molecular plant 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. M.; Wang, D.; Pierson, L. S., 3rd; Pierson, E. A. , Effect of Producing Different Phenazines on Bacterial Fitness and Biological Control in Pseudomonas chlororaphis 30-84. The plant pathology journal 2018, 34(1), 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Pan, H.; Boak, E. N.; Pierson, L. S., 3rd; Pierson, E. A. , Phenazine-Producing Rhizobacteria Promote Plant Growth and Reduce Redox and Osmotic Stress in Wheat Seedlings Under Saline Conditions. Frontiers in plant science 2020, 11, 575314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G. E.; Howell, C. R.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I.; Lorito, M. , Trichoderma species — opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2004, 2(1), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorito, M.; Woo, S. L.; Harman, G. E.; Monte, E. , Translational research on Trichoderma: from 'omics to the field. Annual review of phytopathology 2010, 48, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S. L.; Hermosa, R.; Lorito, M.; Monte, E. , Trichoderma: a multipurpose, plant-beneficial microorganism for eco-sustainable agriculture. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21(5), 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, M.; Cascone, P.; Chiusano, M. L.; Colantuono, C.; Lorito, M.; Pennacchio, F.; Rao, R.; Woo, S. L.; Guerrieri, E.; Digilio, M. C. , Trichoderma harzianum enhances tomato indirect defense against aphids. Insect science 2017, 24(6), 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, M.; Cascone, P.; Lelio, I. D.; Woo, S. L.; Lorito, M.; Rao, R.; Pennacchio, F.; Guerrieri, E.; Digilio, M. C. , Trichoderma atroviride P1 Colonization of Tomato Plants Enhances Both Direct and Indirect Defense Barriers Against Insects. Frontiers in physiology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, M.; Diretto, G.; Digilio, M. C.; Woo, S. L.; Giuliano, G.; Molisso, D.; Pennacchio, F.; Lorito, M.; Rao, R. , Transcriptome and Metabolome Reprogramming in Tomato Plants by Trichoderma harzianum strain T22 Primes and Enhances Defense Responses Against Aphids. Frontiers in physiology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M. S.; Subbiah, V. K.; Siddiquee, S. , Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Trichoderma Isolates against Sugarcane Woolly Aphid, Ceratovacuna lanigera Zehntner (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Horticulturae 2022, 8(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarbeigi, F.; Samih, M. A.; Alaei, H.; Shirani, H. , Induced Tomato Resistance Against Bemisia tabaci Triggered by Salicylic Acid, β-Aminobutyric Acid, and Trichoderma. Neotropical entomology 2020, 49(3), 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muvea, A. M.; Meyhöfer, R.; Subramanian, S.; Poehling, H. M.; Ekesi, S.; Maniania, N. K. , Colonization of onions by endophytic fungi and their impacts on the biology of Thrips tabaci. PLoS One 2014, 9(9), e108242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H. A.; del-Val, E.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.; Alarcón, A.; González-Esquivel, C. E.; Larsen, J. , Trichoderma atroviride, a maize root associated fungus, increases the parasitism rate of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda by its natural enemy Campoletis sonorensis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2018, 122, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lelio, I.; Coppola, M.; Comite, E.; Molisso, D.; Lorito, M.; Woo, S. L.; Pennacchio, F.; Rao, R.; Digilio, M. C. , Temperature Differentially Influences the Capacity of Trichoderma Species to Induce Plant Defense Responses in Tomato Against Insect Pests. Frontiers in plant science 2021, 12, 678830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papantoniou, D.; Vergara, F.; Weinhold, A.; Quijano, T.; Khakimov, B.; Pattison, D. I.; Bak, S.; van Dam, N. M.; Martínez-Medina, A., Cascading Effects of Root Microbial Symbiosis on the Development and Metabolome of the Insect Herbivore Manduca sexta L. Metabolites 2021, 11 (11).

- Kinyungu, S. W.; Agbessenou, A.; Subramanian, S.; Khamis, F. M.; Akutse, K. S. , One stone for two birds: Endophytic fungi promote maize seedlings growth and negatively impact the life history parameters of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Frontiers in physiology 2023, 14, 1253305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lelio, I.; Forni, G.; Magoga, G.; Brunetti, M.; Bruno, D.; Becchimanzi, A.; De Luca, M. G.; Sinno, M.; Barra, E.; Bonelli, M.; Frusciante, S.; Diretto, G.; Digilio, M. C.; Woo, S. L.; Tettamanti, G.; Rao, R.; Lorito, M.; Casartelli, M.; Montagna, M.; Pennacchio, F. , A soil fungus confers plant resistance against a phytophagous insect by disrupting the symbiotic role of its gut microbiota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2023, 120(10), e2216922120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, M. L.; Samaras, K.; Koufakis, I.; Broufas, G. D. , Beneficial Soil Microbes Negatively Affect Spider Mites and Aphids in Pepper. Agronomy 2021, 11(9), 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, H. A. d.; Araújo Filho, J. V. d.; Freitas, L. G. d.; Castillo, P.; Rubio, M. B.; Hermosa, R.; Monte, E. , Tomato progeny inherit resistance to the nematode Meloidogyne javanica linked to plant growth induced by the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma atroviride. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 40216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Yao, M.; Wang, H.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Duan, Y.; Chen, L. , Isolation and effect of Trichoderma citrinoviride Snef1910 for the biological control of root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. BMC Microbiology 2020, 20(1), 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharan, R.; Patil, J. A.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, A.; Goyal, V. , The nematicidal potential of novel fungus, Trichoderma asperellum FbMi6 against Meloidogyne incognita. Scientific Reports 2023, 13(1), 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berini, F.; Caccia, S.; Franzetti, E.; Congiu, T.; Marinelli, F.; Casartelli, M.; Tettamanti, G. , Effects of Trichoderma viride chitinases on the peritrophic matrix of Lepidoptera. Pest Management Science 2016, 72(5), 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayakumar, N.; Alagar, S.; Madanagopal, N. , Effects of chitinase from Trichoderma viride on feeding, growth and biochemical parameters of the rice moth, Corcyra cephalonica Stainton. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2016, 4(4), 520–523. [Google Scholar]

- Massry, S.; Shokry, H. M.; Hegab, M. In EFFICIENCY OF Trichoderma harzianum AND SOME ORGANIC ACIDS ON THE COTTON BOLLWORMS, Earias insulana AND Pectinophora gossypiella, 2016.

- Chinnaperumal, K.; Govindasamy, B.; Paramasivam, D.; Dilipkumar, A.; Dhayalan, A.; Vadivel, A.; Sengodan, K.; Pachiappan, P. , Bio-pesticidal effects of Trichoderma viride formulated titanium dioxide nanoparticle and their physiological and biochemical changes on Helicoverpa armigera (Hub.). Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 2018, 149, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S. K.; Pal, S. , Entomopathogenic potential of Trichoderma longibrachiatum and its comparative evaluation with malathion against the insect pest Leucinodes orbonalis. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2015, 188(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Huang, X.-F.; Guo, J.; dos-Santos, M. L.; Vivanco, J. M. , Trichoderma gamsii affected herbivore feeding behaviour on Arabidopsis thaliana by modifying the leaf metabolome and phytohormones. Microbial Biotechnology 2018, 11(6), 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. D.; Gorman, Z.; Huang, P. C.; Kenerley, C. M.; Kolomiets, M. V. , Trichoderma virens colonization of maize roots triggers rapid accumulation of 12-oxophytodienoate and two ᵧ-ketols in leaves as priming agents of induced systemic resistance. Plant signaling & behavior 2020, 15 (9), 1792187. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Huang, P.-C.; Borrego, E.; Kolomiets, M. , New perspectives into jasmonate roles in maize. Plant signaling & behavior 2014, 9 (10), e970442–e970442. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Liu, B.; Liu, L.; Song, S. , Jasmonate action in plant growth and development. Journal of Experimental Botany 2017, 68(6), 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Song, L.; Gong, X.; Xu, J.; Li, M. , Functions of Jasmonic Acid in Plant Regulation and Response to Abiotic Stress. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21 (4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažok, R.; Lemić, D.; Chiarini, F.; Furlan, L. , Western Corn Rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) in Europe: Current Status and Sustainable Pest Management. Insects 2021, 12 (3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddock, K. J.; Robert, C. A. M.; Erb, M.; Hibbard, B. E. , Western Corn Rootworm, Plant and Microbe Interactions: A Review and Prospects for New Management Tools. Insects 2021, 12 (2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrière, Y.; Brown, Z.; Aglasan, S.; Dutilleul, P.; Carroll, M.; Head, G.; Tabashnik, B. E.; Jørgensen, P. S.; Carroll, S. P. , Crop rotation mitigates impacts of corn rootworm resistance to transgenic Bt corn. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117(31), 18385–18392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.; Kenerley, C. , Detection and enumeration of a genetically modified fungus in soil environments by quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2006, 25, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C. A.; Rasband, W. S.; Eliceiri, K. W. , NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 2012, 9(7), 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).