Submitted:

24 January 2024

Posted:

25 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell preparation

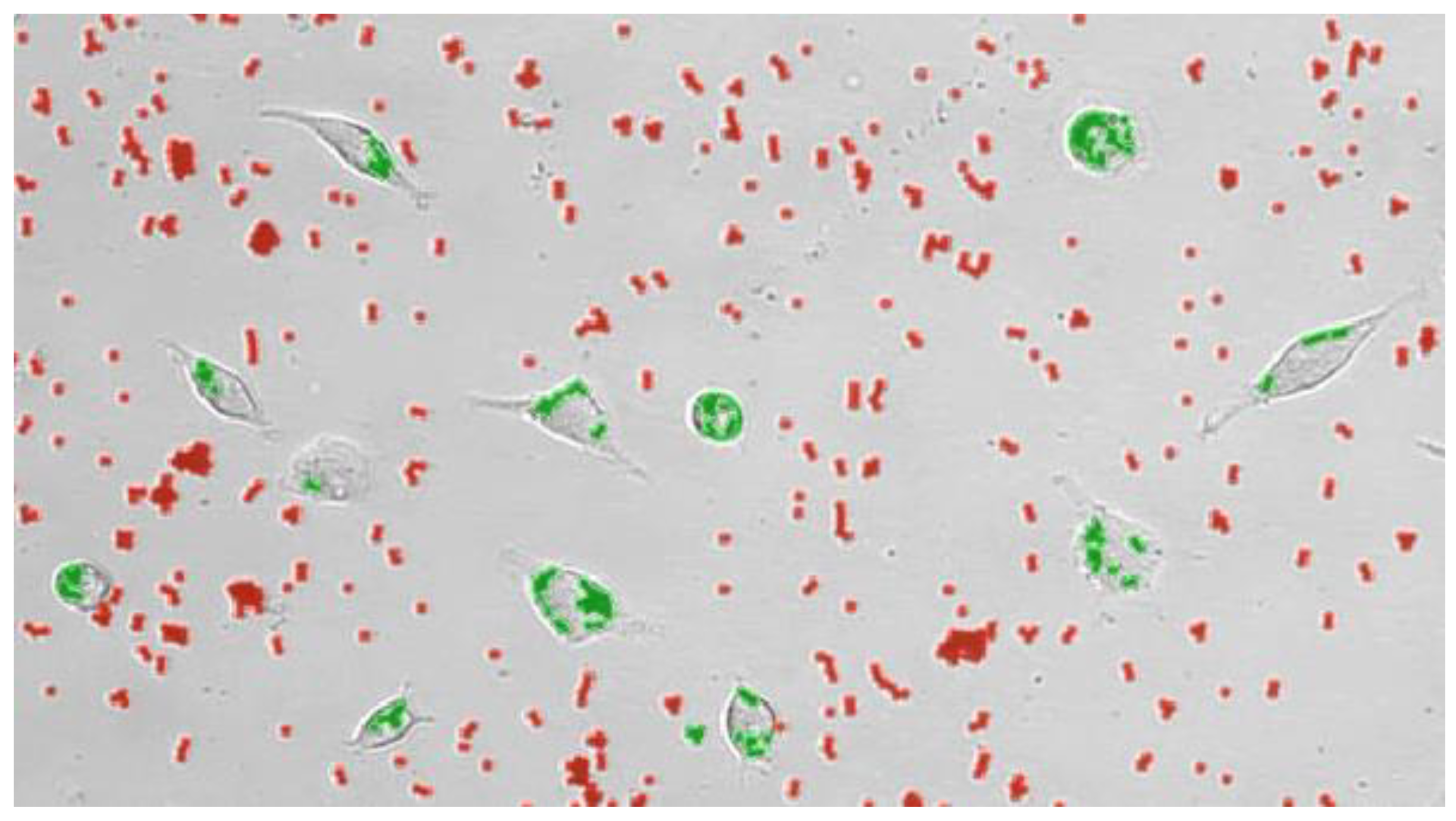

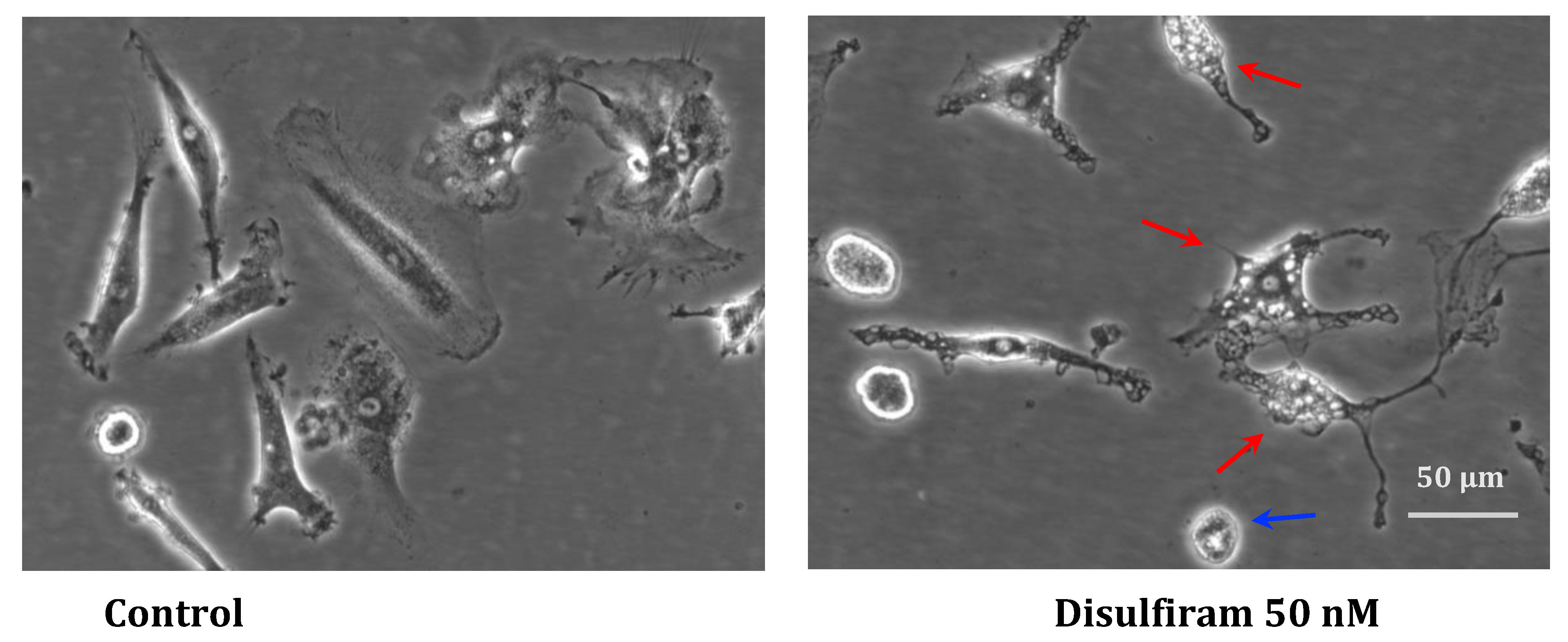

2.3. Macrophage images based on Phase-contrast microscopy

2.4. Cytospin preparation and Wright-Giemsa stain

2.5. Monitoring phagocytosis by video microscopy

2.6. Metabolic characterization cultured macrophages and dendritic cells activated in vivo.

2.7. Flow cytometry

2.8. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Quantification of functional phenotypes expressed by cultured macrophages

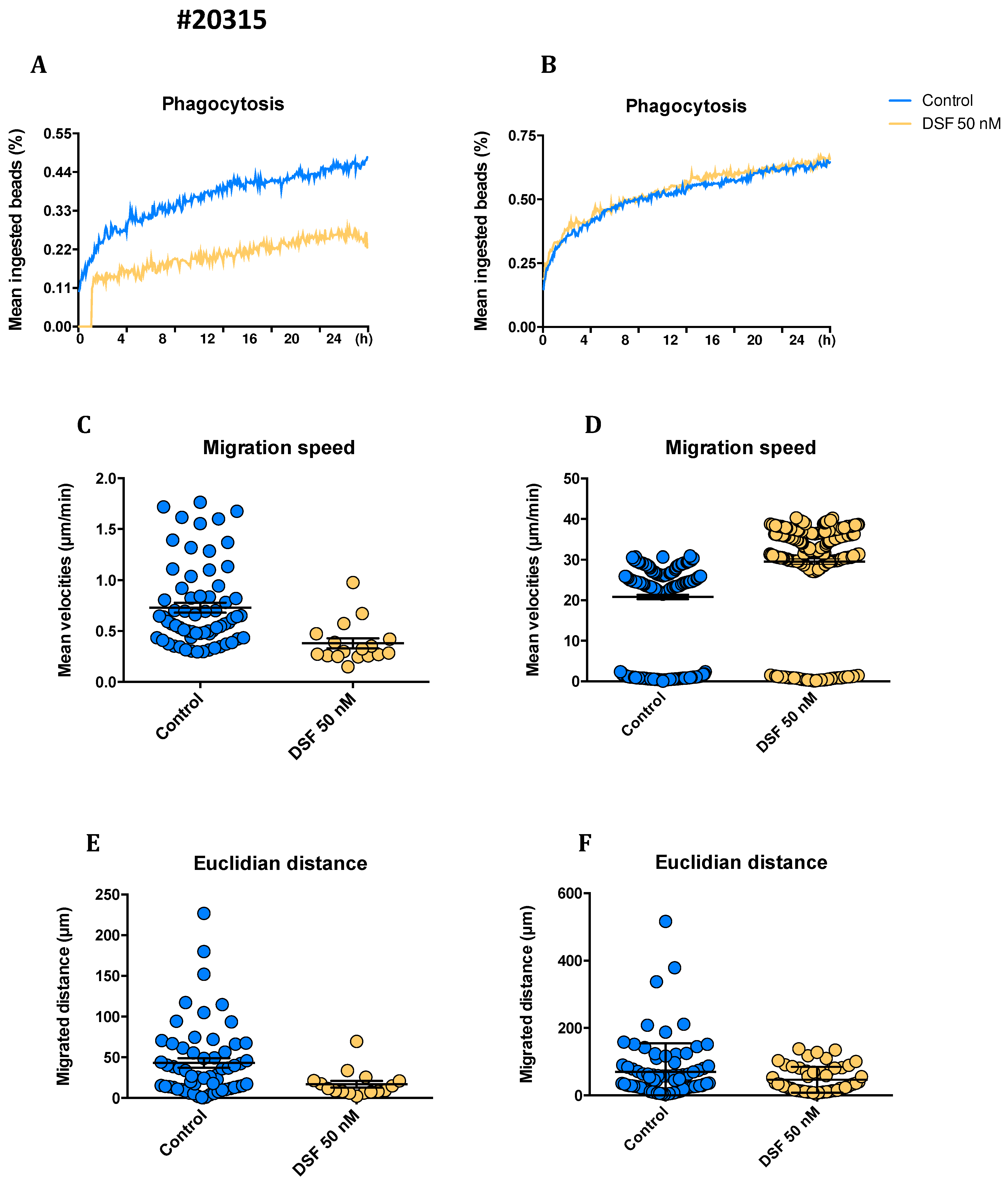

3.1.1. Phagocytosis

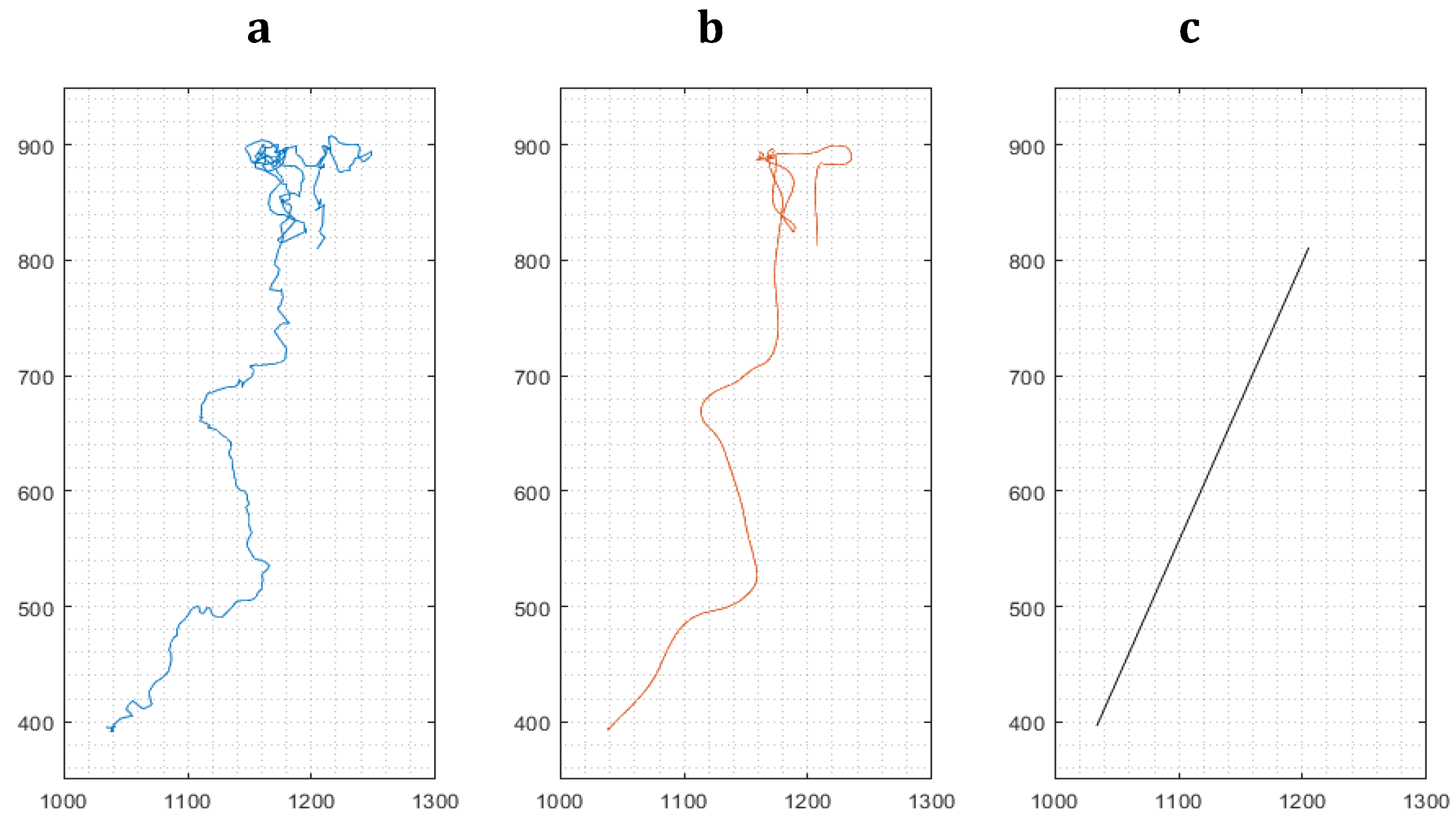

3.1.2. Cell movement analysis for migration distance velocity

3.2. Identification of macrophage phenotypes

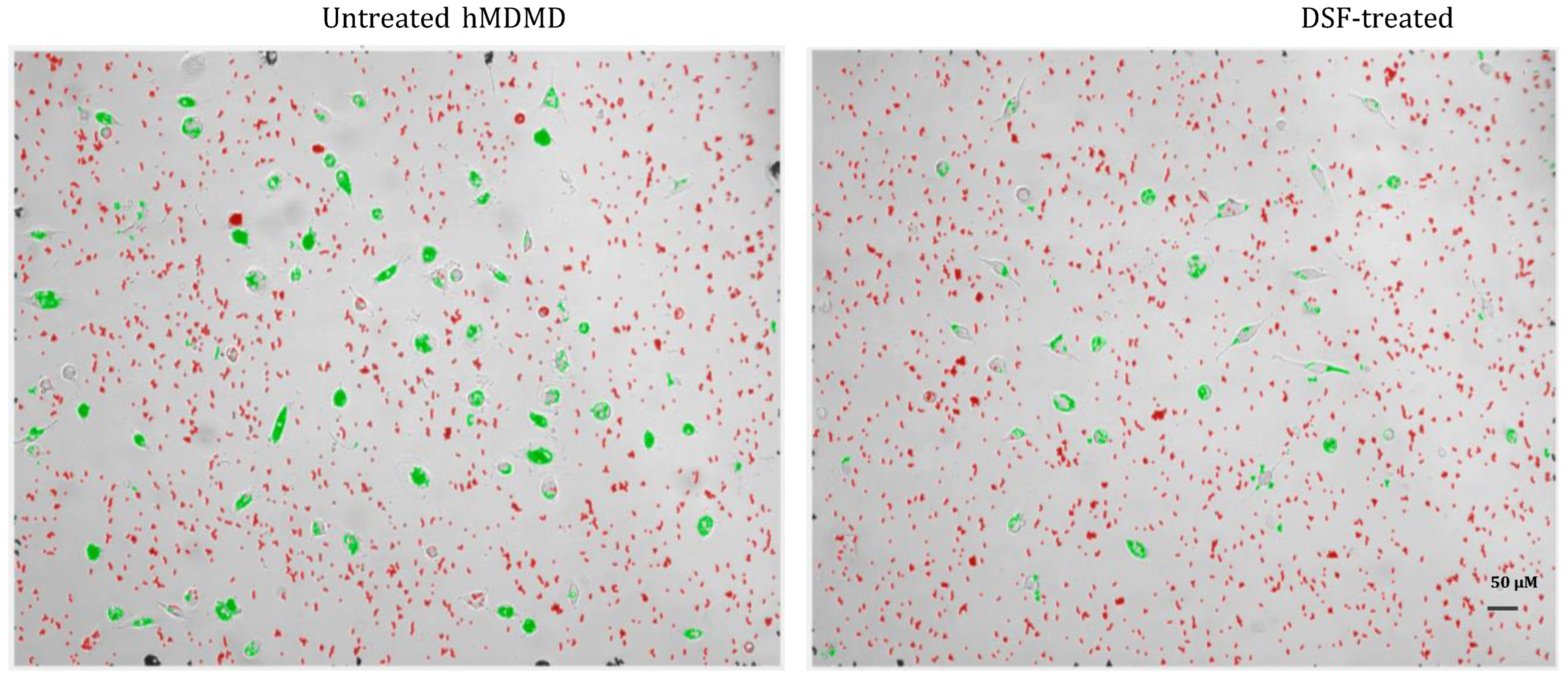

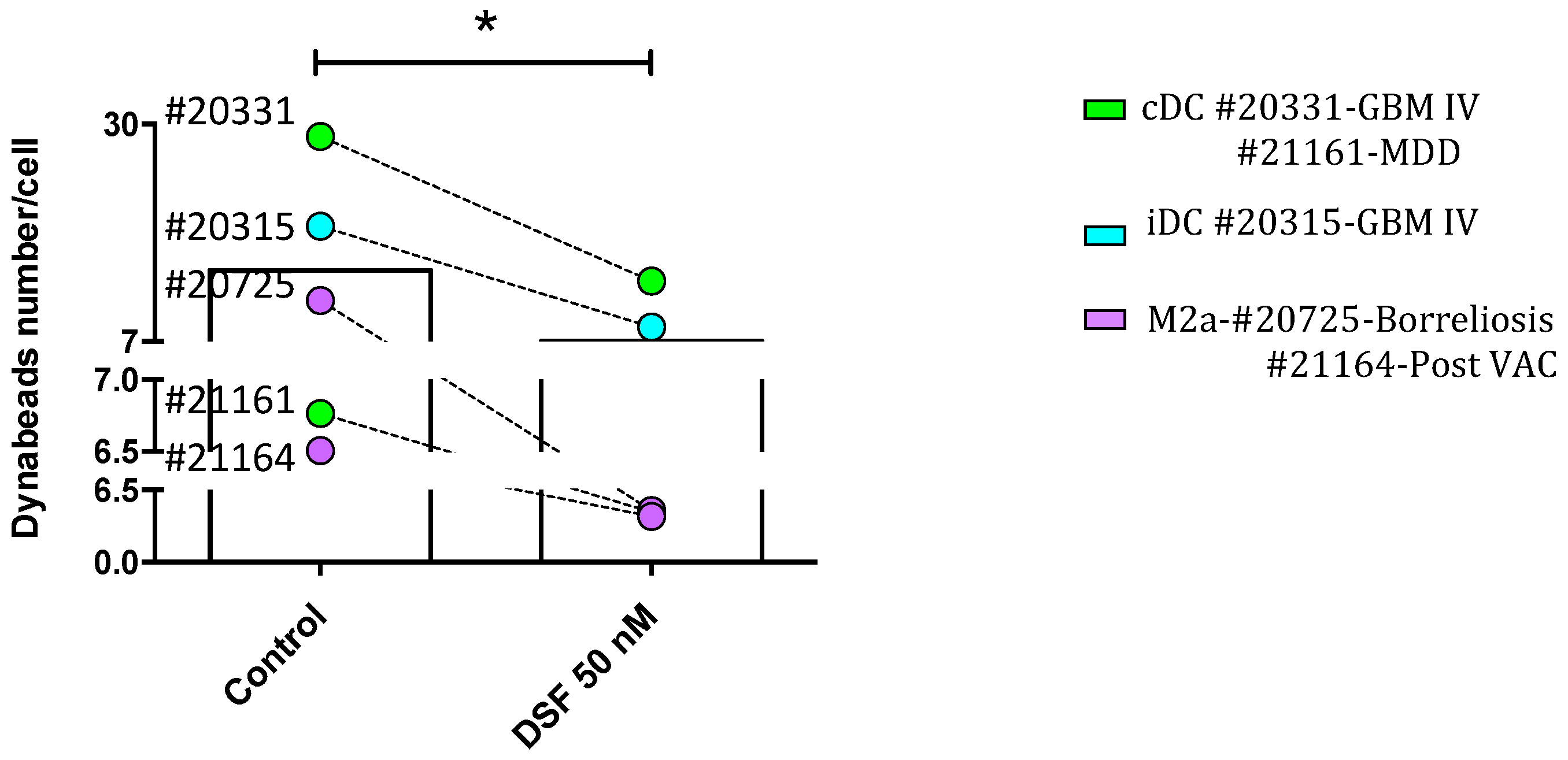

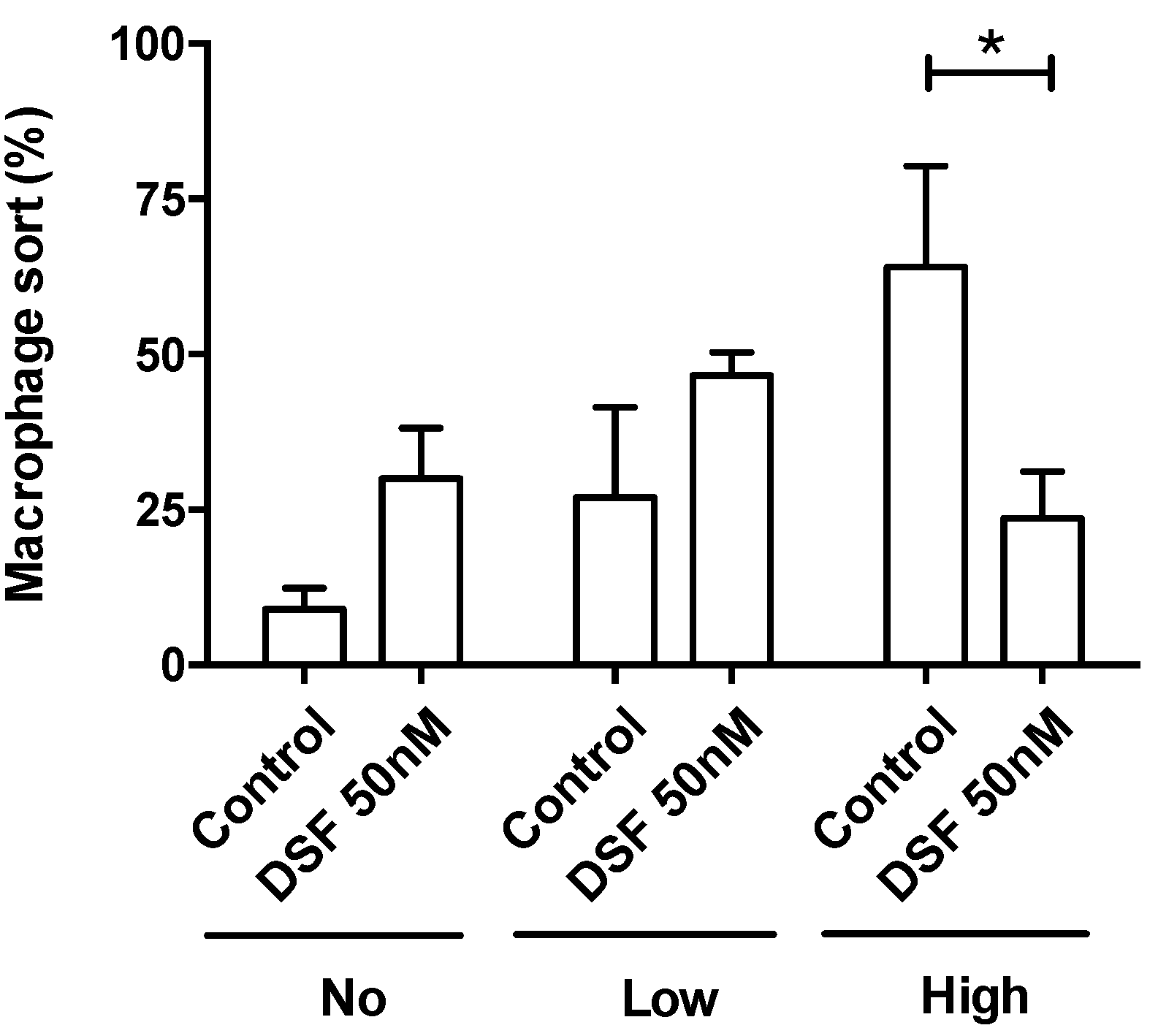

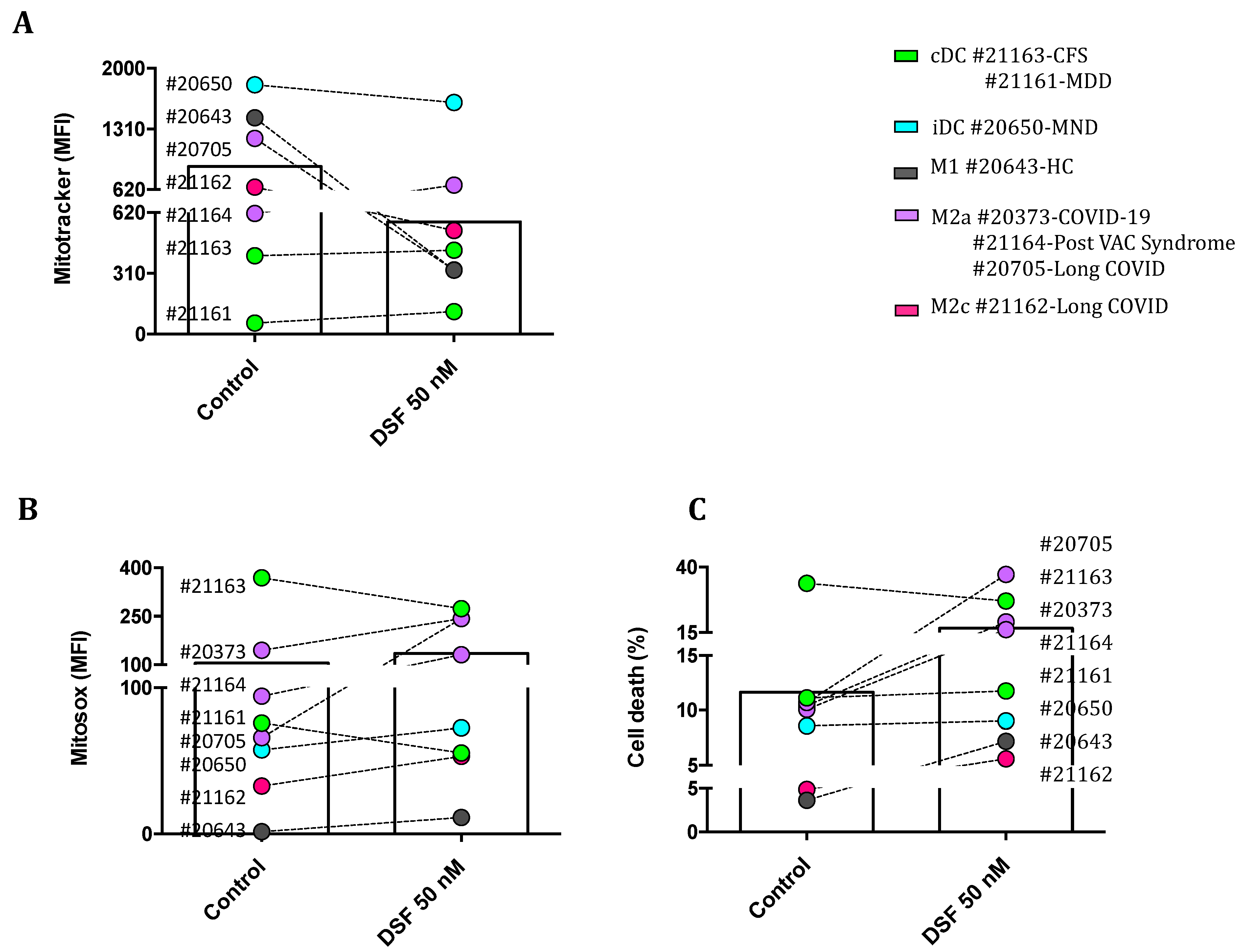

3.3. Modulation of macrophage and dendritic cell function and viability by DSF

3.3.1. Correlation of reduced phagocytosis and cell death induced by DSF

3.3.2. Correlation of DSF-induced mitochondrial ROS and cell death

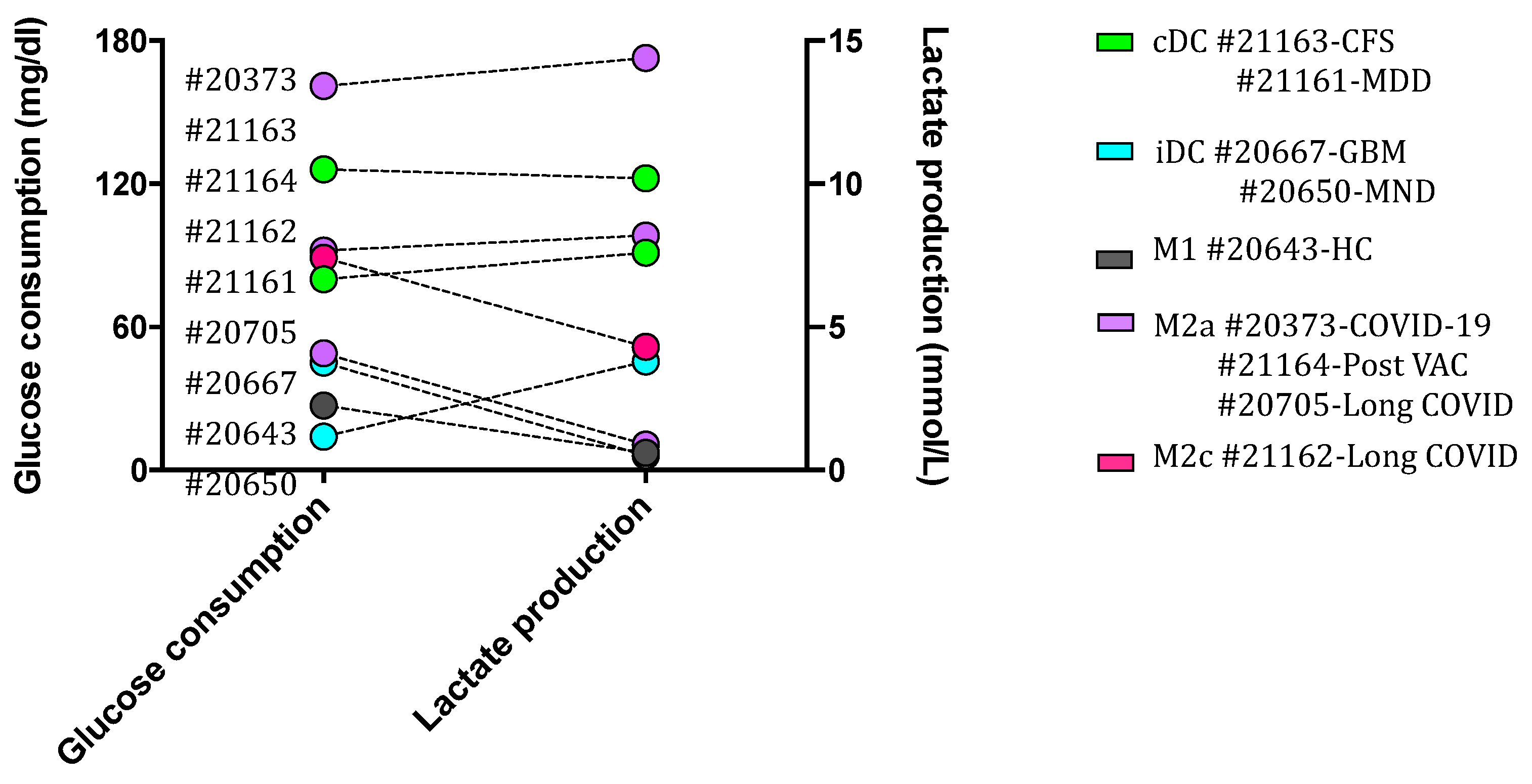

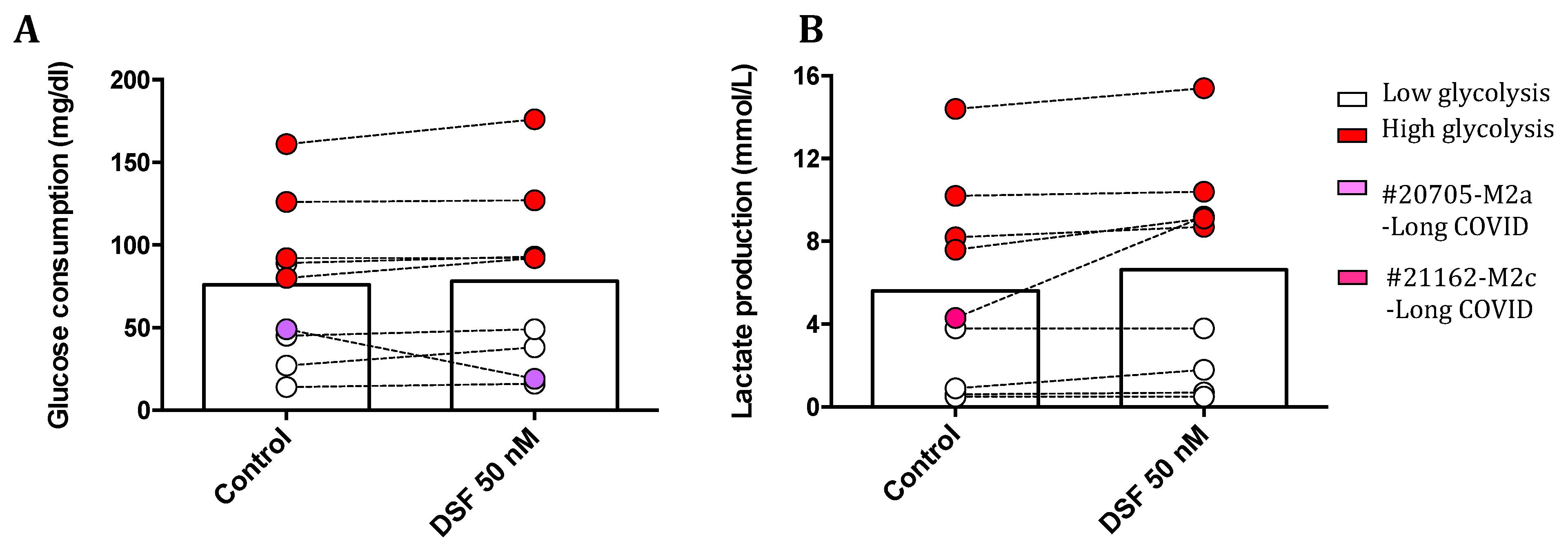

3.3.3. Correlation between glycolytic metabolism and macrophages phenotype regulated by DSF

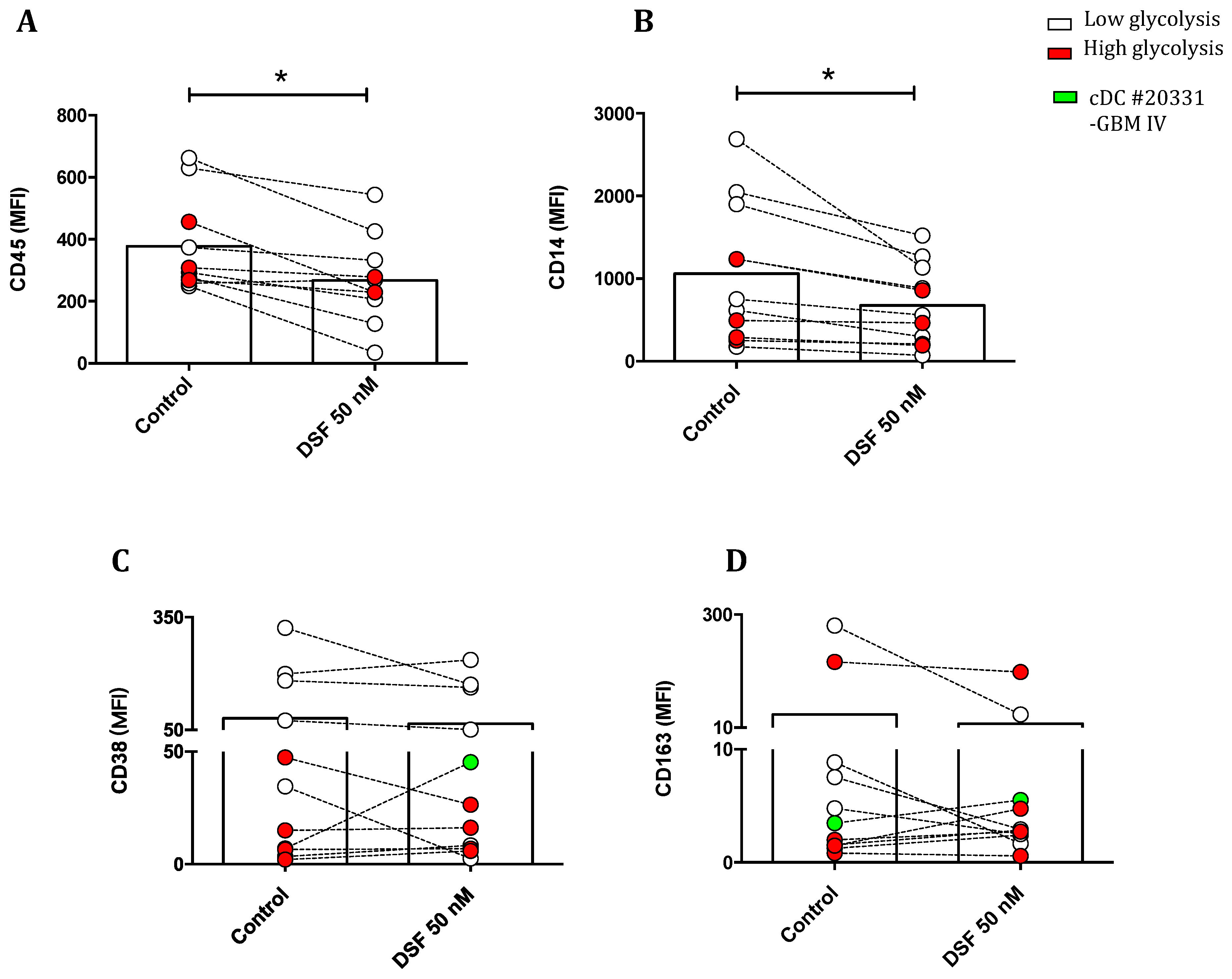

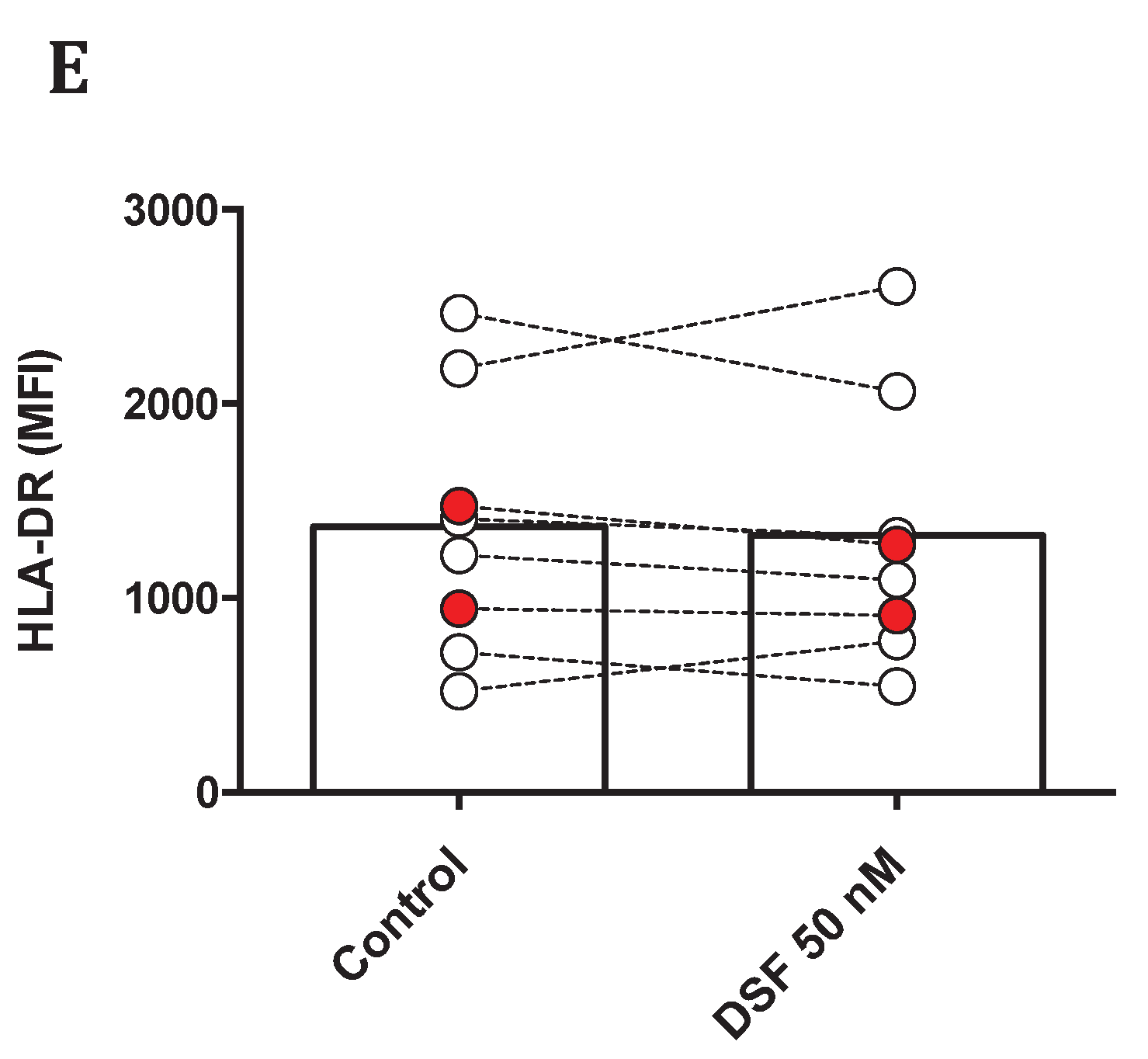

3.3.4. Modulation of surface antigens expression by DSF

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Hein, T.M.; Sander, P.; Giryes, A.; Reinhardt, J.O.; Hoegel, J.; Schneider, E.M. Cytokine Expression Patterns and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in Patients with Chronic Borreliosis. Antibiotics (Basel) 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prete, A.; Salvi, V.; Soriani, A.; Laffranchi, M.; Sozio, F.; Bosisio, D.; Sozzani, S. Dendritic cell subsets in cancer immunity and tumor antigen sensing. Cell Mol Immunol 2023, 20, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyshev, I.; Malyshev, Y. Current Concept and Update of the Macrophage Plasticity Concept: Intracellular Mechanisms of Reprogramming and M3 Macrophage “Switch” Phenotype. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 341308. [Google Scholar]

- Sica, A.; Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 787–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, K.A.; Amici, S.A.; Webb, L.M.; Jde, D.R.-R.; Popovich, P.G.; Partida-Sanchez, S.; Guerau-de-Arellano, M. Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0145342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Rendón-Huerta, E.P.; Ortiz-Navarrete, V.; Montaño, L.F. CD38 and Regulation of the Immune Response Cells in Cancer. J Oncol 2021, 2021, 6630295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.M.; Liu, K.; Liu, J.H.; Jiang, X.L.; Wang, X.L.; Chen, Y.Z.; Li, S.G.; Zou, H.; Pang, L.J.; Liu, C.X.; Cui, X.B.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Shen, X.H.; Jiang, J.F.; Liang, W.H.; Yuan, X.L.; Li, F. CD163 as a marker of M2 macrophage, contribute to predicte aggressiveness and prognosis of Kazakh esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 21526–21538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.L.; Peres, C.; Conniot, J.; Matos, A.I.; Moura, L.; Carreira, B.; Sainz, V.; Scomparin, A.; Satchi-Fainaro, R.; Préat, V.; Florindo, H.F. Nanoparticle impact on innate immune cell pattern-recognition receptors and inflammasomes activation. Semin Immunol 2017, 34, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrchen, J.M.; Roth, J.; Barczyk-Kahlert, K. More Than Suppression: Glucocorticoid Action on Monocytes and Macrophages. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Li, X.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, X. Disulfiram: a novel repurposed drug for cancer therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2021, 87, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najlah, M.; Suliman, A.S.; Tolaymat, I.; Kurusamy, S.; Kannappan, V.; Elhissi, A.M.A.; Wang, W. Development of Injectable PEGylated Liposome Encapsulating Disulfiram for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parny, M.; Bernad, J.; Prat, M.; Salon, M.; Aubouy, A.; Bonnafé, E.; Coste, A.; Pipy, B.; Treilhou, M. Comparative study of the effects of ziram and disulfiram on human monocyte-derived macrophage functions and polarization: involvement of zinc. Cell Biol Toxicol 2021, 37, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cao, L.; Egami, Y.; Kawai, K.; Araki, N. Cofilin contributes to phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized particles but not non-opsonized particles in RAW264 macrophages. Microscopy (Oxf) 2016, 65, 233–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderem, A.; Underhill, D.M. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu Rev Immunol 1999, 17, 593–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palecanda, A.; Kobzik, L. Receptors for unopsonized particles: the role of alveolar macrophage scavenger receptors. Curr Mol Med 2001, 1, 589–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobzik, L. Lung macrophage uptake of unopsonized environmental particulates. Role of scavenger-type receptors. J Immunol 1995, 155, 367–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palecanda, A.; Paulauskis, J.; Al-Mutairi, E.; Imrich, A.; Qin, G.; Suzuki, H.; Kodama, T.; Tryggvason, K.; Koziel, H.; Kobzik, L. Role of the scavenger receptor MARCO in alveolar macrophage binding of unopsonized environmental particles. J Exp Med 1999, 189, 1497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huth, J.; Buchholz, M.; Kraus, J.M.; Schmucker, M.; von Wichert, G.; Krndija, D.; Seufferlein, T.; Gress, T.M.; Kestler, H.A. Significantly improved precision of cell migration analysis in time-lapse video microscopy through use of a fully automated tracking system. BMC Cell Biol 2010, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norling, M.; Karlsson-Lindsjö, O.E.; Gourlé, H.; Bongcam-Rudloff, E.; Hayer, J. MetLab: An In Silico Experimental Design, Simulation and Analysis Tool for Viral Metagenomics Studies. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0160334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, P.; Okai, B.; Hoare, J.I.; Erwig, L.P.; Wilson, H.M. SOCS3 is a modulator of human macrophage phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol 2016, 100, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patente, T.A.; Pinho, M.P.; Oliveira, A.A.; Evangelista, G.C.M.; Bergami-Santos, P.C.; Barbuto, J.A.M. Human Dendritic Cells: Their Heterogeneity and Clinical Application Potential in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis-Toth, K.; Hajdu, P.; Bacskai, I.; Szilagyi, O.; Papp, F.; Szanto, A.; Posta, E.; Gogolak, P.; Panyi, G.; Rajnavolgyi, E. Voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.7 maintains the membrane potential and regulates the activation and chemokine-induced migration of a monocyte-derived dendritic cell subset. J Immunol 2011, 187, 1273–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comi, M.; Avancini, D.; de Sio, F.S.; Villa, M.; Uyeda, M.J.; Floris, M.; Tomasoni, D.; Bulfone, A.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Gregori, S. Coexpression of CD163 and CD141 identifies human circulating IL-10-producing dendritic cells (DC-10). Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerke, C.; Mueller, P.; Nebe, B. Attempted caveolae-mediated phagocytosis of surface-fixed micro-pillars by human osteoblasts. Biomaterials 2016, 76, 102–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, C.; Grazu, V.; Guisan, J.M. Immobilization of enzymes on monofunctional and heterofunctional epoxy-activated supports. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 1051, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gu, B.J.; Duce, J.A.; Valova, V.A.; Wong, B.; Bush, A.I.; Petrou, S.; Wiley, J.S. P2X7 receptor-mediated scavenger activity of mononuclear phagocytes toward non-opsonized particles and apoptotic cells is inhibited by serum glycoproteins but remains active in cerebrospinal fluid. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 17318–17330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, J.D.; Feig, B.; Vasta, G.R. Effect of fetal bovine serum glycoproteins on the in vitro proliferation of the oyster parasite Perkinsus marinus: development of a fully defined medium. J Eukaryot Microbiol 1995, 42, 307–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kholmukhamedov, A.; Schwartz, J.M.; Lemasters, J.J. Isolated mitochondria infusion mitigates ischemia-reperfusion injury of the liver in rats: mitotracker probes and mitochondrial membrane potential. Shock 2013, 39, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Tao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhao, J.; Huang, R.; Pei, Z. DL-3-n-butylphthalide protects endothelial cells against oxidative/nitrosative stress, mitochondrial damage and subsequent cell death after oxygen glucose deprivation in vitro. Brain Res 2009, 1290, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.M.; Chen, C.L.; Yang, C.M.; Wu, P.H.; Tsou, C.J.; Chiang, K.W.; Wu, W.B. The carotenoid lutein enhances matrix metalloproteinase-9 production and phagocytosis through intracellular ROS generation and ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and RARβ activation in murine macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 2013, 93, 723–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.C.; Wlodarska, M.; Liu, D.J.; Abraham, N.; Johnson, P. CD45 regulates migration; proliferation, and progression of double negative 1 thymocytes. J Immunol 2010, 185, 2059–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, A.E.; Johnson, P. Modulation of immune cell signalling by the leukocyte common tyrosine phosphatase, CD45. Cell Signal 2010, 22, 339–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwingmann, C.; Leibfritz, D.; Hazell, A.S. Energy metabolism in astrocytes and neurons treated with manganese: relation among cell-specific energy failure, glucose metabolism, and intercellular trafficking using multinuclear NMR-spectroscopic analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2003, 23, 756–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummer, L.; Zaradzki, M.; Vijayan, V.; Arif, R.; Weigand, M.A.; Immenschuh, S.; Wagner, A.H.; Larmann, J. Vascular Signaling in Allogenic Solid Organ Transplantation - The Role of Endothelial Cells. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, J.; Moulefera, M.A.; Balthazard, R. On the structure-function of MHC class II molecules and how single amino acid polymorphisms could alter intracellular trafficking. Hum Immunol 2019, 80, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crux, N.B.; Elahi, S. Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) and Immune Regulation: How Do Classical and Non-Classical HLA Alleles Modulate Immune Response to Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Hepatitis C Virus Infections? Front Immunol 2017, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaglini, F.; Viaggi, C.; Piro, V.; Pardini, C.; Gerace, C.; Scarselli, M.; Corsini, G.U. Acetaldehyde; parkinsonism: role of CYP450. Front Behav Neurosci 2013, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boscá, L.; González-Ramos, S.; Prieto, P.; Fernández-Velasco, M.; Mojena, M.; Martín-Sanz, P.; Alemany, S. Metabolic signatures linked to macrophage polarization: from glucose metabolism to oxidative phosphorylation. Biochem Soc Trans 2015, 43, 740–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orihuela, R.; McPherson, C.A.; Harry, G.J. Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br J Pharmacol 2016, 173, 649–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.L.; O’Neill, L.A. Reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism in macrophages as an anti-inflammatory signal. Eur J Immunol 2016, 46, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, R.; Gu, H.; Zhang, E.; Qu, J.; Cao, W.; Huang, X.; Yan, H.; He, J.; Cai, Z. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophage responses. Biomark Res 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Moses, D.C.; Hsieh, C.H.; Cheng, S.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Sun, C.Y.; Chou, C.Y. Disulfiram can inhibit MERS and SARS coronavirus papain-like proteases via different modes. Antiviral Res 2018, 150, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Ye, F.; Feng, Y.; Yu, F.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Sun, H.; Huang, B.; Niu, P.; Song, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Tan, W.; Qi, J.; Gao, G.F. Both Boceprevir and GC376 efficaciously inhibit SARS-CoV-2 by targeting its main protease. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froggatt, H.M.; Heaton, B.E.; Heaton, N.S. Development of a Fluorescence-Based, High-Throughput SARS-CoV-2 3CL(pro) Reporter Assay. J Virol 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.J.; Liu, X.; Xia, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ruan, J.; Luo, X.; Lou, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Hollingsworth, L.R.; Magupalli, V.G.; Zhao, L.; Luo, H.R.; Kim, J.; Lieberman, J.; Wu, H. FDA-approved disulfiram inhibits pyroptosis by blocking gasdermin D pore formation. Nat Immunol 2020, 21, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Fei, C.Y.; Chen, Y.P.; Sargsyan, K.; Chang, C.P.; Yuan, H.S.; Lim, C. Synergistic Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Replication Using Disulfiram/Ebselen and Remdesivir. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2021, 4, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potula, H.S.K.; Shahryari, J.; Inayathullah, M.; Malkovskiy, A.V.; Kim, K.M.; Rajadas, J. Repurposing Disulfiram (Tetraethylthiuram Disulfide) as a Potential Drug Candidate against Borrelia burgdorferi In Vitro and In Vivo. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troxell, B.; Ye, M.; Yang, Y.; Carrasco, S.E.; Lou, Y.; Yang, X.F. Manganese and zinc regulate virulence determinants in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun 2013, 81, 2743–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grage-Griebenow, E.; Flad, H.D.; Ernst, M. Heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets. J Leukoc Biol 2001, 69, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coillard, A.; Segura, E. , In vivo Differentiation of Human Monocytes. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Hoyo, G.M.; Martín, P.; Vargas, H.H.; Ruiz, S.; Arias, C.F.; Ardavín, C. Characterization of a common precursor population for dendritic cells. Nature 2002, 415, 1043–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrusiewicz, K.; Rodriguez, B.; Wei, J.; Hashimoto, Y.; Healy, L.M.; Maiti, S.N.; Thomas, G.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Q.; Elakkad, A.; Liebelt, B.D.; Yaghi, N.K.; Ezhilarasan, R.; Huang, N.; Weinberg, J.S.; Prabhu, S.S.; Rao, G.; Sawaya, R.; Langford, L.A.; Bruner, J.M.; Fuller, G.N.; Bar-Or, A.; Li, W.; Colen, R.R.; Curran, M.A.; Bhat, K.P.; Antel, J.P.; Cooper, L.J.; Sulman, E.P.; Heimberger, A.B. Glioblastoma-infiltrated innate immune cells resemble M0 macrophage phenotype. JCI Insight 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremble, L.F.; Forde, P.F.; Soden, D.M. Clinical evaluation of macrophages in cancer: role in treatment, modulation and challenges. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2017, 66, 1509–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; Liao, Q.; Chen, Z.; Peng, H.; Zhou, Y. CD38: A Significant Regulator of Macrophage Function. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 775649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavasi, F.; Deaglio, S.; Funaro, A.; Ferrero, E.; Horenstein, A.L.; Ortolan, E.; Vaisitti, T.; Aydin, S. Evolution and function of the ADP ribosyl cyclase/CD38 gene family in physiology and pathology. Physiol Rev 2008, 88, 841–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilber, M.T.; Gregory, S.; Mallone, R.; Deaglio, S.; Malavasi, F.; Charron, D.; Gelin, C. CD38 expressed on human monocytes: a coaccessory molecule in the superantigen-induced proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 2840–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechler, C.; Ritter, M.; Orsó, E.; Langmann, T.; Klucken, J.; Schmitz, G. Regulation of scavenger receptor CD163 expression in human monocytes and macrophages by pro- and antiinflammatory stimuli. J Leukoc Biol 2000, 67, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tippett, E.; Cheng, W.J.; Westhorpe, C.; Cameron, P.U.; Brew, B.J.; Lewin, S.R.; Jaworowski, A.; Crowe, S.M. Differential expression of CD163 on monocyte subsets in healthy and HIV-1 infected individuals. PLoS One 2011, 6, e19968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PatNo. | Diagnosis | Age | Gender | Phenotype | Exosome |

| 20231 | Xanthogranuloma | 43 | M | cDC (80%), 20% M1) | 21% |

| 20315 | Glioblastoma °IV | 73 | M | iDC | 21% |

| 20331 | Glioblastoma °IV | 66 | F | cDC | 16% |

| 20365 | Pancreatic cancer | 55 | M | M2a | 26% |

| 20373 | COVID-19 infection after stem cell transplantation | 18 | M | M2a | 10% |

| 20643 | Healthy donor | 33 | M | M1 | 5% |

| 20650 | Motor neuron disease | 58 | M | M1+iDC | 1% |

| 20667 | Glioblastoma °IV | 40 | M | M2b+iDC | 2% |

| 20705 | Long-COVID | 20 | F | M2a | 3% |

| 20725 | Borreliosis after DSF treatment | 48 | M | M2a | 2% |

| 21161 | Major depressive disorder | 30 | F | cDC | 10% |

| 21162 | Long-COVID | 32 | M | cDC+M2c | 4% |

| 21163 | Chronic fatigue syndrome | 44 | M | cDC | 17% |

| 21164 | Post VAC syndrome | 43 | F | M2a | 22% |

| 21428 | Prostate cancer | 63 | M | DC-10 | 7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).