1. Introduction

Alcohol is one of the most abused drugs worldwide [

1,

2]. Hazardous alcohol consumption is commonly associated with liver, brain, and gastrointestinal tract disorders; however, since the COVID-19 pandemic, diseases of the respiratory system are becoming more widely linked to hazardous alcohol consumption [

3]. Ties between chronic alcohol abuse and pneumonia have been well established for some time [

4]. However, the connection between binge alcohol intoxication and pulmonary bacterial infections has not been described until more recently [

5,

6,

7]. Binge alcohol intoxication is a hazardous alcohol intake pattern characterized by the consumption of 4–6 standard drinks or reaching a minimum of 0.08% or higher alcohol concentration within a 2–3-hour episode [

8]. Hazardous alcohol consumption, but not necessarily a binge intake pattern, has been shown to alter the initial host-pathogen interactions during infections caused by

Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC)

, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Burkholderia thailandensis [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The exact mechanisms by which alcohol can lead to pulmonary pathology remain unclear, but a major focal point is innate immune dysfunction [

13,

14]. Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are the first line of defense during pulmonary infections, located in the distal respiratory tract, and are critical for detecting, capturing, and eliminating pathogens while initiating the early host immune response. It has been proposed that chronic alcohol exposure, in conjunction with disruptions in the alveolar epithelial barrier integrity and alterations in host defenses of the upper and lower airways, induces a phenotypic change in alveolar macrophages, collectively labeled as the “alcoholic lung” phenotype. Chronic alcohol exposure also inhibits the expression and function of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), preventing Nrf2-dependent production of antioxidants crucial to fighting against pulmonary infections [

15].

Opportunistic pathogens, such as

B. thailandensis and

S. epidermidis, take advantage of impaired early host immune responses to cause infection [

16]. Growing antibiotic resistance makes these types of opportunistic infections a source of great concern [

17].

S. epidermidis is a Gram-positive bacterium that is associated with pneumonia in immunocompromised individuals [

18,

19,

20,

21].

B. thailandensis is a Gram-negative bacterium found in the environment.

B. thailandensis infections are an emerging public health concern both because of the predominate pulmonary infections and its potential to be misidentified as the highly infectious

B. pseudomallei, its closest phylogenetic relative. Both

B. thailandensis and

B. pseudomallei are endemic to the regions of northern Australia and southeast Asia. However,

B. thailandensis has been detected in the United States in the areas of Puerto Rico, Mississippi, and southern Texas by water and soil sampling [

22]. A single binge-like alcohol dose altered phagocytosis in murine AM cells and increased intracellular survival of

B. thailandensis in vitro [

23]. Additionally, in vivo,

B. thailandensis infectivity increased in mice exposed to a binge-like alcohol dose, thus disseminating bacteria in the bloodstream and colonizing major organs [

24].

Depending on the hazardous alcohol consumption case, hospital treatments may include activated charcoal, IV fluids, glucose, thiamine, or medications to manage withdrawal symptoms. However, a viable prophylactic option to mitigate the toxic effects of hazardous alcohol consumption and protect otherwise healthy individuals from opportunistic infection is currently unavailable and not well studied. Phytonutrients are a class of plant-derived compounds that are bioactive and can affect cytoprotective cellular processes. One of the more promising phytonutrients is sulforaphane (SFN), an isothiocyanate, generated from the enzymatic cleavage of glucoraphanin which is present in cruciferous vegetables such as kale and broccoli [

25]. Although SFN itself is weakly prooxidant, SFN has been shown to induce cytoprotective measures via Nrf2. Nrf2 is a redox-sensitive transcription factor that regulates the activation of the antioxidant response element (ARE), which has a significant role in cellular protection via antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes [

26,

27,

28]. Furthermore, SFN protects against the effects of oxidative damage and phagocytic dysfunction induced by chronic alcohol use in alveolar macrophages [

29]. Phagocytic activity and engulfment have been shown to increase in mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages when pretreated with SFN in the absence of an alcohol stimulus [

30]. Given this evidence, SFN is attractive for therapeutic purposes to prevent alcohol-induced innate immune dysfunction in the context of infection because of its cellular protective properties, and the compound requires a low concentration for maximal bioactivity [

26].

Small-molecule drug discovery is a multi-step process that integrates target validation, fragment-based screening, followed by lead optimization and preclinical testing. In addition to basic toxicology cell culture studies, incorporating low-cost insect models significantly enhances this pipeline by providing inexpensive, high-throughput, whole-animal screens that inform compound selection and early toxicity profiling, paving the way for fewer failures in rodent models and, ultimately, human trials.

Galleria mellonella larvae, also known as wax worms, were first used for published research in the 1950’s [

31]. They are a useful bridge between cellular and mammalian experiments because they have a notably similar innate immune system to that of mammalian species [

32]. As such, they have been widely used in studying bacterial and fungal infections and have served as low-cost models for testing new antibiotic therapies [

33]. An additional benefit to the

G. mellonella model for the study of human opportunistic infection is the standard 37 °C incubation. This temperature induces expression of bacterial virulence factors and is at or near human body temperature [

31,

34], thus creating a more relevant clinical context for research.

The present study evaluated SFN’s therapeutic potential against alcohol--induced immune dysfunction using both in vitro and in vivo models. First, we established dose-response curves in murine (MH--S) and human (THP--1) macrophage cell lines. Next, we assessed SFN as a prophylactic agent by pretreating these cells prior to exposure to hazardous levels of alcohol. We then extended our in vitro findings by challenging SFN--pretreated macrophages with live bacterial infection. Finally, we translated this paradigm into an in vivo G. mellonella larval model, measuring survival after SFN pretreatment and subsequent alcohol and bacterial challenge. We hypothesized that SFN pretreatment would preserve macrophage phagocytic function previously shown to be impaired by alcohol and improve larval survival compared to controls.

These experiments provide the first comprehensive comparison of SFN’s protective effects across murine, human, and insect models. By demonstrating SFN’s ability to both restore macrophage function in human cells and enhance host resilience in an invertebrate infection model, our study highlights a novel, cross--species therapeutic approach. These findings lay the groundwork for future clinical investigations, suggesting that SFN supplementation may mitigate alcohol--related immune deficiencies in patients and ultimately improve outcomes in alcohol--exacerbated infections

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Murine alveolar macrophage (ATCC: MH-S, CRL-2019) and human monocytes (ATCC: THP-1, TIB-202) were used in these studies at passages ≤ 6 and ≥ 90% confluency. Cells were regularly grown in T-75 cell culture flasks in phenol red-free RMPI-1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 mg/mL streptomycin. Both MH-S and THP-1 cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5.5% CO

2. Cells were seeded in 24-well cell culture plates at 1 × 10

6 cells/well and incubated for all experiments in low evaporative cell culture plates, a compensating system previously described by Jimenez et al., to avoid evaporation of alcohol during treatments [

23]. RPMI-1640 media supplemented with alcohol (ethanol absolute, 200 proofs, Fisher BioReagents) were used based on biological relevancy and cell viability > 85%.

THP-1 cell differentiation: THP-1 cells required differentiation from monocytes to macrophages prior to SFN and alcohol exposure. This was accomplished by incubating THP-1 cells in 100 ng/mL of PMA (phorbol myristate acetate, Cayman Chemical Item No. 10008014) and 10ng/ml Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) for 24 hours and then verified using microscopy. After differentiation, cells were rinsed and immediately used experimentally.

2.2. Cell Viability Assay

To optimize the dose of SFN or alcohol, dose response experiments were conducted. Both MH-S and THP-1 cells were cultured with 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 50 μM SFN for 2 or 24 hours. The effects of alcohol (i.e., ethanol) on MH-S and THP-1 cell viability were tested in a similar procedure; cells were cultured with 0, 0.08, 0.2, 0.4% alcohol (v/v) for 3 or 24 hours. Five µM SFN and 0.2% (v/v) alcohol concentrations were used for all further experiments based on ≥ 85% cell viability after a CyQUANT LDH viability assay (ThermoFisher Cat # C20300). Briefly, spontaneous, positive, vehicle controls, and samples were transferred to a flat bottom 96-well plate, incubated with reaction mixture, and read via BioTek Synergy microplate reader at wavelengths described by the manufacturer.

The percentage of viable cells were calculated as follows:

2.3. Intracellular Killing Assay

Both MH-S and differentiated THP-1 cell lines were pre-treated with 0 or 5 μM SFN for 24 hours; cell monolayers were rinsed and then challenged with 0 or 0.2% (v/v) alcohol. Cell monolayers were co-cultured with viable B. thailandensis for MH-S cells, or S. epidermidis for THP-1 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1:1 for 3 hours and 8 hours at 37 ⁰ C, and with 5.5% CO2, to allow phagocytosis to occur. At a MOI of 1:1 cell viability was ≥ 90%. After 3 and 8 hours, extracellular bacteria were removed by washing the cells with DPBS and replacing culture media with new media supplemented with 250 μg/mL of kanamycin for 1 hour. Thereafter, the cell monolayers were incubated at 37 ⁰ C in media with 50 μg/mL kanamycin for an additional 2 hours to completely remove any residual extracellular bacteria. Any intracellular bacterial remained unaffected by the antibiotic treatment.

Intracellular phagocytic killing occurred for a total of 3 hours post infection. After 3 hours, cell culture media was removed, and the infected cell monolayers were washed. To determine the ability of MH-S and THP-1 cells to kill intracellular bacteria, cell monolayers were lysed with DPBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Viable intracellular bacteria were quantified by plating serial dilutions of the lysate, and average CFUs were determined on LB agar plates.

2.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Samples for the ELISA were prepared using extracted supernatant from the intracellular killing assay for human THP-1 cells from both the 3-hour and 8-hour cultures prior to the initial DPBS wash. Invitrogen ELISA kits were used to measure levels of TNF-α (Cat #88-7346-22), Interleukin-10 (IL-10) (Cat #88-7106-22), and IFN-γ (Cat #88-7316-22) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Testing was run in triplicates in a 96-well plate for each condition collected from the human THP-1 experiment. The controls were plated in duplicate. Absorbance measurements were quantified by BioTek synergy microplate reader at wavelengths described by the manufacturer.

2.5. Galleria mellonella Model

Galleria mellonella larvae were purchased from Bio suppliers, maintained at 37 °C in the dark, and used within 3 days. The normal supply of larvae was fasted prior to experimental use. Larvae weighed between 100 and 150 mg at time of inoculation. Twenty larvae per group (N=20) were each injected with 10 μL of inoculum into the caudal prolegs using a 22s-gauge point style 25µL microliter syringe (Hamilton PN 84855). Each group of 20 insects were incubated at 37 °C in 9 cm petri dishes without food for up to 5 days unless otherwise specified.

2.6. Galleria mellonella Survival Curves

Survival curves were generated to optimize doses of SFN, alcohol,

S. epidermidis, and

B. thailandensis in the larvae. For the prophylaxis study, the

G. mellonella larvae were divided into nine test groups. The groups consisted of the following: negative control (no injections), vehicle control (1% DMSO), and the rest of the groups were inoculated with 100 µM SFN, 0.08% (v/v) ALC, and/or

S. epidermidis or

B. thailandensis. SFN was injected into the right caudal proleg, ALC in the left caudal proleg, and bacteria in the right cephalad proleg to minimize injection trauma. Injections were spaced so that ALC was administered 3-hours after SFN prophylaxis, and then with pathogen inoculation 1 hour later (

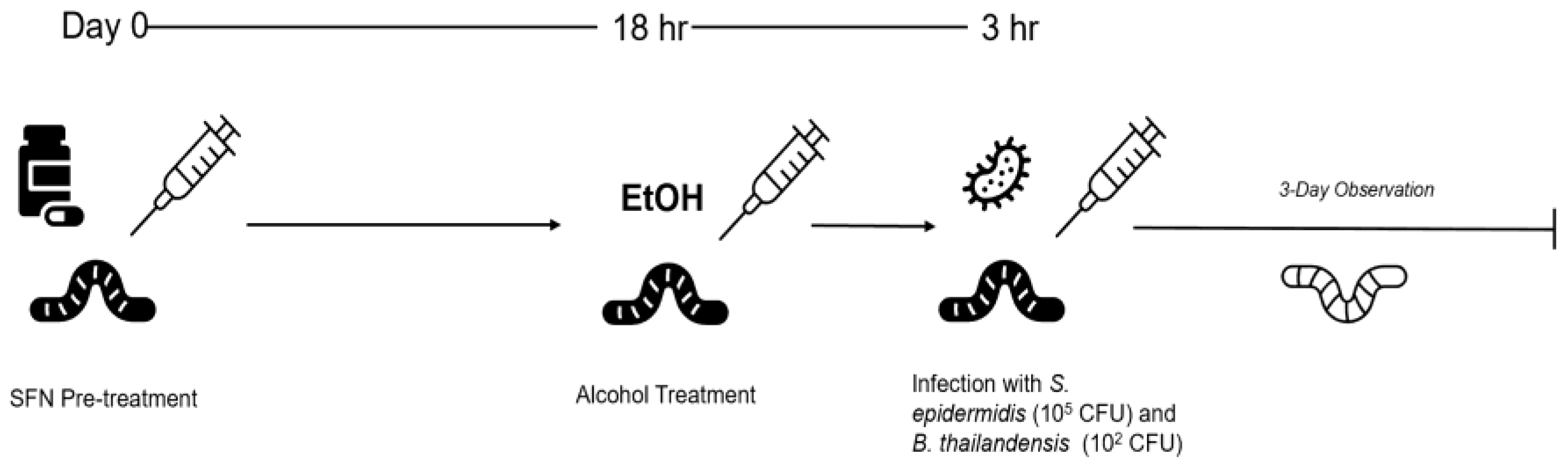

Figure 1).

2.7. Monitoring of Galleria mellonella Larvae

To optimize doses for SFN, alcohol, or to study various post-infection doses, G. mellonella larvae were monitored over a 72-hour period in 24-hour intervals for the following attributes: activity, extent of silk production (cocoon formation), and melanization. The attributes were used to determine survival. In addition, a score was provided that contributed toward an overall health index of an individual wax worm. A healthy wax worm typically scored between 9 and 10, and an infected, dead wax worm typically scored 0.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data analysis was completed using Prism 10.0 software (Graph Pad, 10.1, San Diego, CA). The assay replicating independence and significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons, and Student’s t-test. Each N represents at least 4 experimental replicates (i.e., identical experimental wells) and at least 2 assay replicates from each experimental replicate. Each cell culture experiment was conducted independently at least twice on different days. Additional statistics were performed using R, and non-parametric, unequal variances. Survival analysis of G. mellonella consisted of Kaplan-Meier survival curves (log-rank test). At least three independent experiments were conducted, and a representative one is presented on the plot. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Discussion

Binge alcohol intoxication (BAI) in humans is defined as elevated blood alcohol concentration to a minimum of 0.08% in a single episode [

8]. BAI has a profound effect on innate immunity and is associated with impaired macrophage responses during an infection. The impairment of macrophage phagocytic ability increases the risk of opportunistic bacterial infections. Utilization of SFN as a prophylactic therapy to mitigate the deleterious effects of hazardous alcohol consumption on innate immunity, remains to be explored. Furthermore, the cytoprotective effects of SFN as a pre-treatment to hazardous alcohol consumption in the context of a bacterial infection have not been quantified.

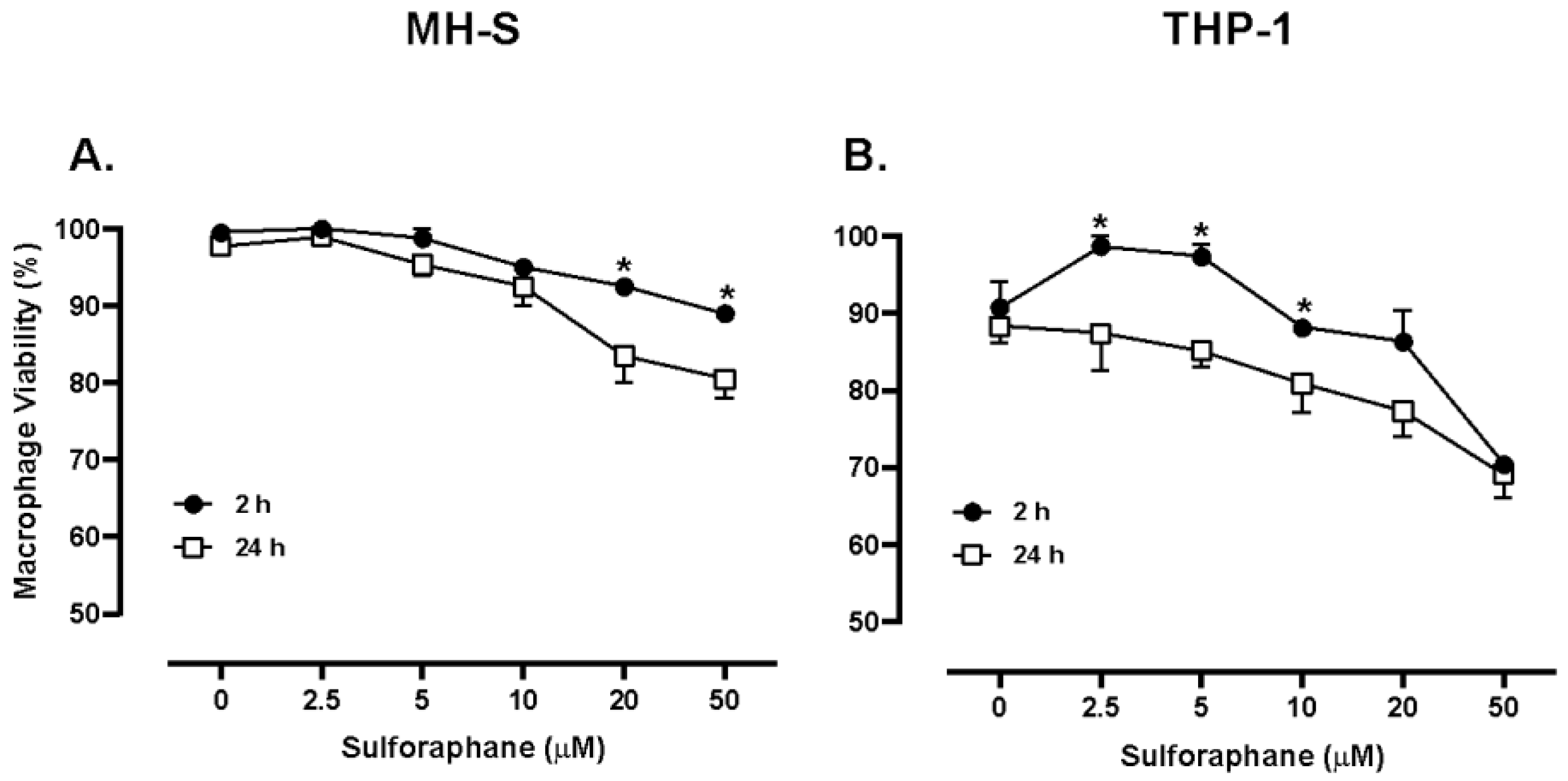

In the current study, murine MH-S cells treated with SFN for 24 hours with doses below 20 μM resulted in cell viability of approximately 90%. However, human THP-1 cells treated with SFN doses below 10 μM for 24 hours resulted in cell viability of approximately 90%. The downward and rightward shift in the THP-1 dose-response curve suggests an increased SFN potency with the human cell line (

Figure 1). To test approximate equivalent doses in terms of cellular effects, 5 μM SFN was tested in subsequent experiments as the cell viability was similar between cell lines. It is plausible that the differences in SFN cytotoxicity between species results from variations in metabolism. Nevertheless, these data indicate 5 μM SFN is not cytotoxic to murine or human macrophage cells. Similarly, Eren et al. found that N9 microglial cells experienced no significant decrease in cell viability after 24-hour exposure to SFN concentrations of 10μM or less [

35]. Tuttis et al. observed that human prostate cancer cells (DU145 and PC-3) treated with concentrations of 2, 4, and 8 μM of SFN for 24 hours also showed no significant loss of cell viability [

36]. Additionally, SFN in the 5-20 μM range may affect other cellular immune functions. Schwab et al. found in their study that human HT-29 colonocytes expressed mRNA for HBD-2, an endogenous antimicrobial peptide, in a dose dependent manner starting at 5 μM up to 20 μM, expressing 3x greater mRNA levels compared to controls. Additionally, HBD-2 protein levels were 1.6x greater than untreated controls after being exposed to 20 μM SFN for 24 hours of SFN exposure [

37]. Myzak et al. noted that with a 10 μM oral gavage of SFN in APC

min mice, HDAC activity was decreased by 65%. There was also a significant 2-fold increase in H3 and H4 histone acetylation within the colonic mucosa after 6 hours [

38]. Likewise in the current study a significant effect in phagocytic function of macrophages after both three- and eight-hour incubation was measured. Taken together, these findings provide support for SFN doses below 10 μM being non-toxic and biologically relevant.

An alcohol binge is a single alcohol consumption event that brings blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08% or above. For most adults, this means having 5 or more drinks (male), or 4 or more drinks (female), in the space of near 2 hours [

39]. Moreira et al. provided an equation for estimation of BAC which would indicate that if a human male or female of average weight in the United States drank the minimum binge dose according to the NIAAA definition listed above, the blood alcohol would be 0.081% for males and 0.056% for females [

40,

41]. These benchmarks set an ideal minimum for studying binge alcohol type behavior in humans. However, in other experiments using an in vivo mouse model, an alcohol binge was defined as the administration of 5g/kg body weight by gavage. The blood alcohol concentration of these mice reached nearly 400 mg/dL which equates to a blood alcohol level of near 0.4%. It must be considered, however, that before administration of their “binge dose,” the mice in the study were observing a liquid diet meant to model chronic alcohol abuse and had pre-binge blood alcohol concentrations of near 180 mg/dL [

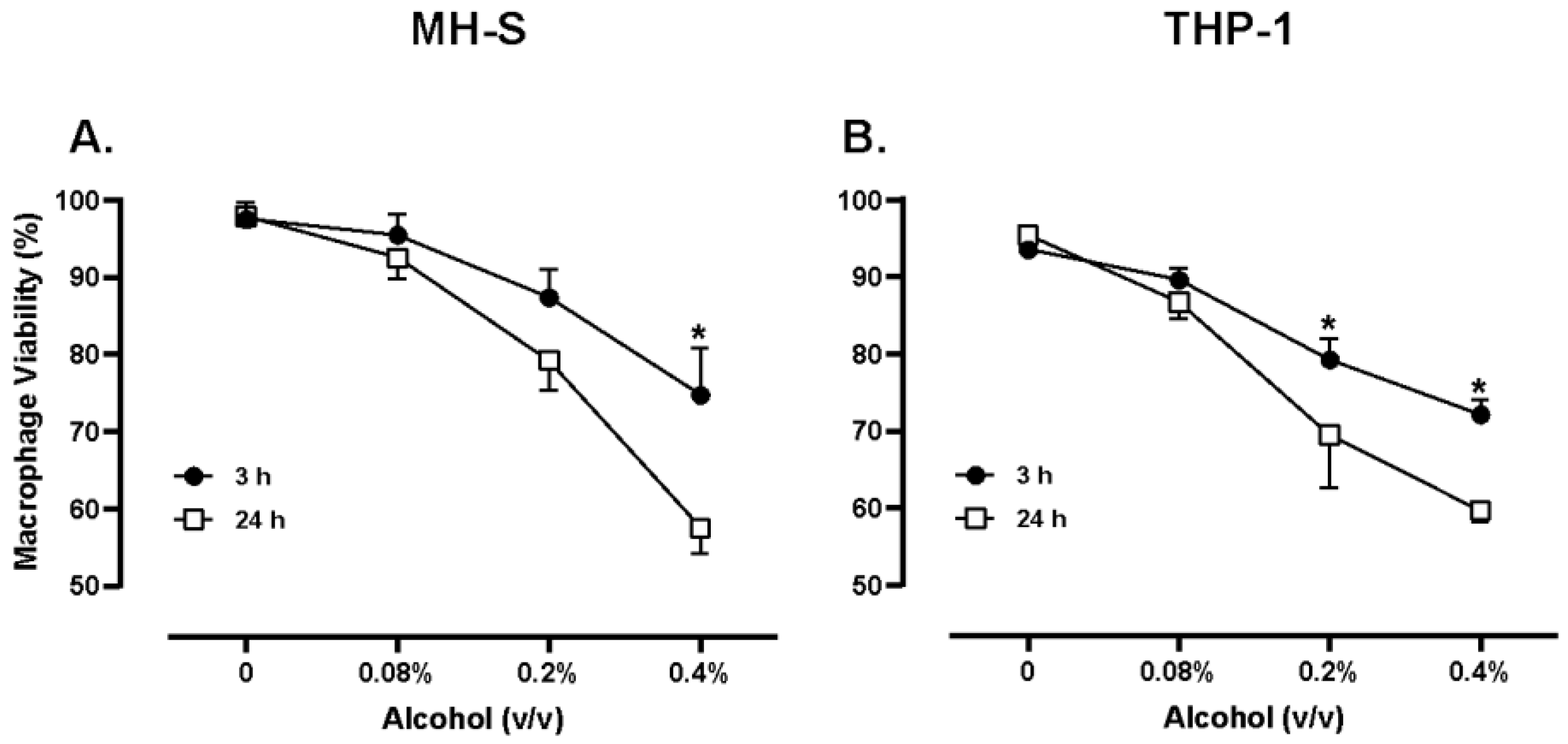

42]. In the current study an alcohol dose of 220 mg/dL or 0.22% v/v was utilized to model hazardous alcohol consumption. Jimenez et al. noted that with concentrations of alcohol at 0.2% (v/v) and an exposure period of 8 hours, MH-S macrophages had a 2.5-fold increase in intracellular bacterial survival, suggesting that 0.2% (v/v) alcohol is a dose that could dampen the innate immune response and set the stage for opportunistic infections. In the current study, various doses of alcohol were studied in both murine and human cells to optimize biologically relevant doses for the remainder of the study. Pursuant to these findings, we measured both human and murine macrophage viability when exposed to 0.2% (v/v) alcohol to be near 70-80%. The current study also noted significant increases in intracellular bacterial survival in Gram-positive and Gram-negative species when macrophages of both mice and humans were exposed to 0.2% (v/v) alcohol (

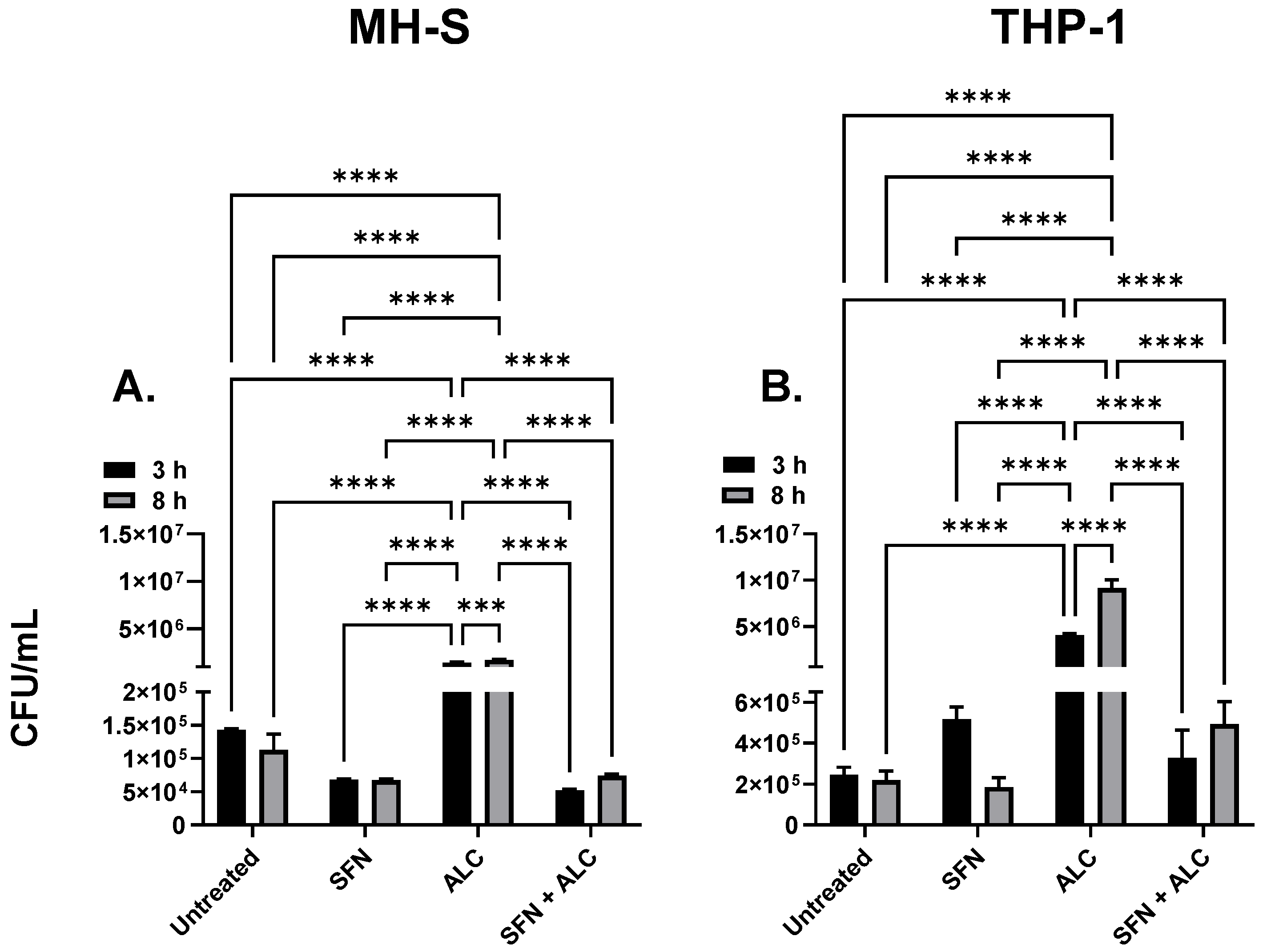

Figure 3). These data suggest that 0.2% (v/v) alcohol is a dose capable of causing significant impairment to innate immune functions, yet preserves the viability of cells, indicating biological relevance.

To test SFN as a pretreatment to hazardous alcohol exposure, murine or human tissue cells were pretreated with SFN for 24 hours, followed by the removal of SFN treatment and exposure to the hazardous alcohol insult and bacterial challenge. Macrophage function was tested by measuring viable intracellular survival of Gram-positive

S. epidermidis and Gram-negative

B. thailandensis. In both murine and human cell lines, alcohol exposure significantly impaired macrophage phagocytic ability (

Figure 3). The alcohol-induced impairment served as a primary biological insult, allowing opportunistic pathogens to cause infection or prolonged bacterial survival. In fact, tens of thousands of deaths each year are attributed to alcohol-induced opportunistic infections [

15]. In the current study, SFN pretreatment induced a 50-fold reduction of bacterial survival compared to alcohol only treated cells (

Figure 3-B). Treatment groups of both THP-1 and MH-S cell lines significantly decreased levels of bacteria compared with the ALC only administered group. These data show that both

B. thailandensis, a Gram-negative organism, and

S. epidermidis, a Gram-positive organism, are susceptible to SFN pretreated macrophages and thus that SFN could serve as a potential immunomodulating agent for defense against various opportunistic pathogens. Suganuma et al. demonstrated similar immunomodulatory results, where SFN treated RAW 264.7 cells exhibited an increase in phagocytosis of 2 μM polystyrene beads through the inhibition of migration inhibitory factor (MIF) [

30].

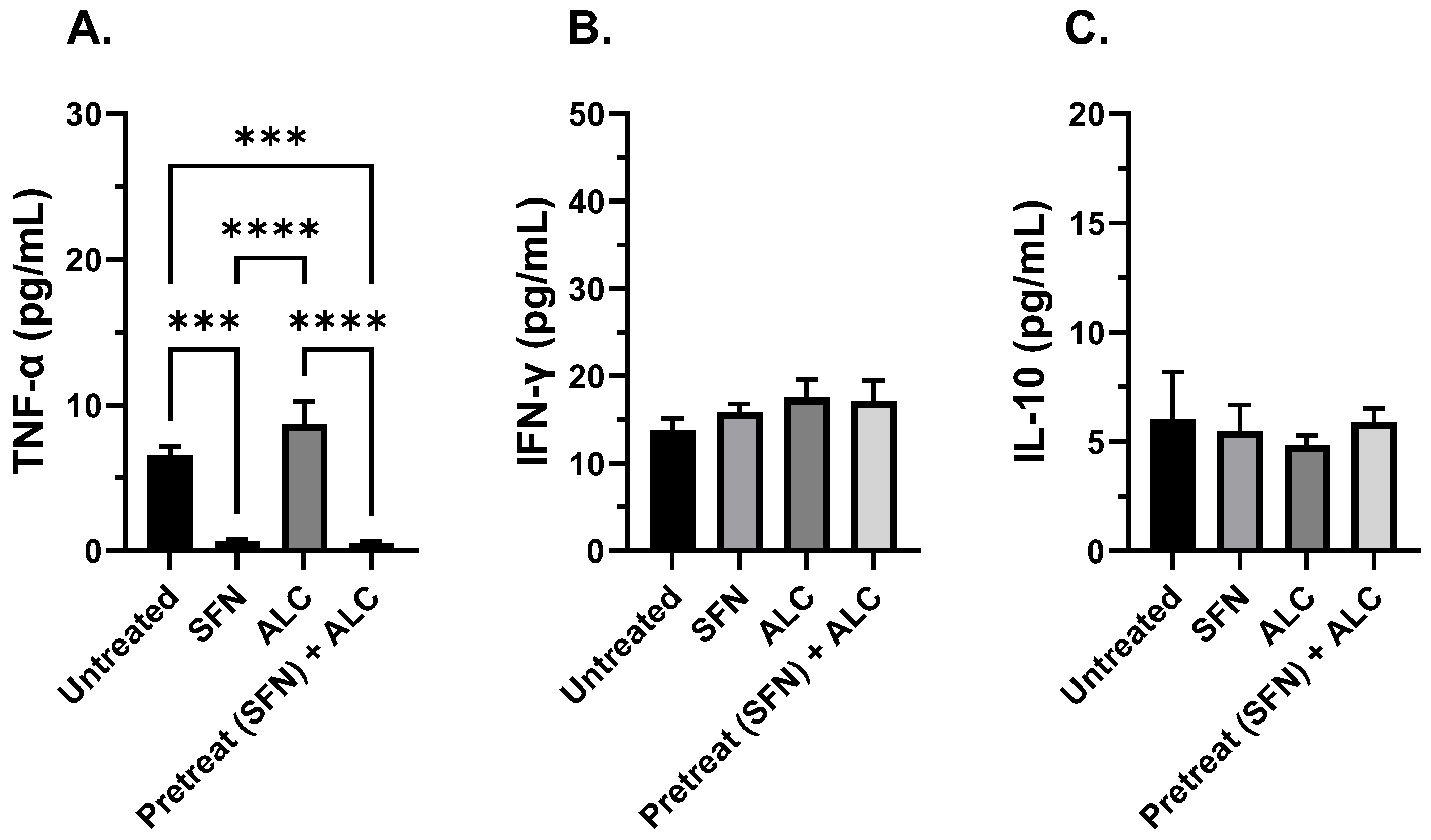

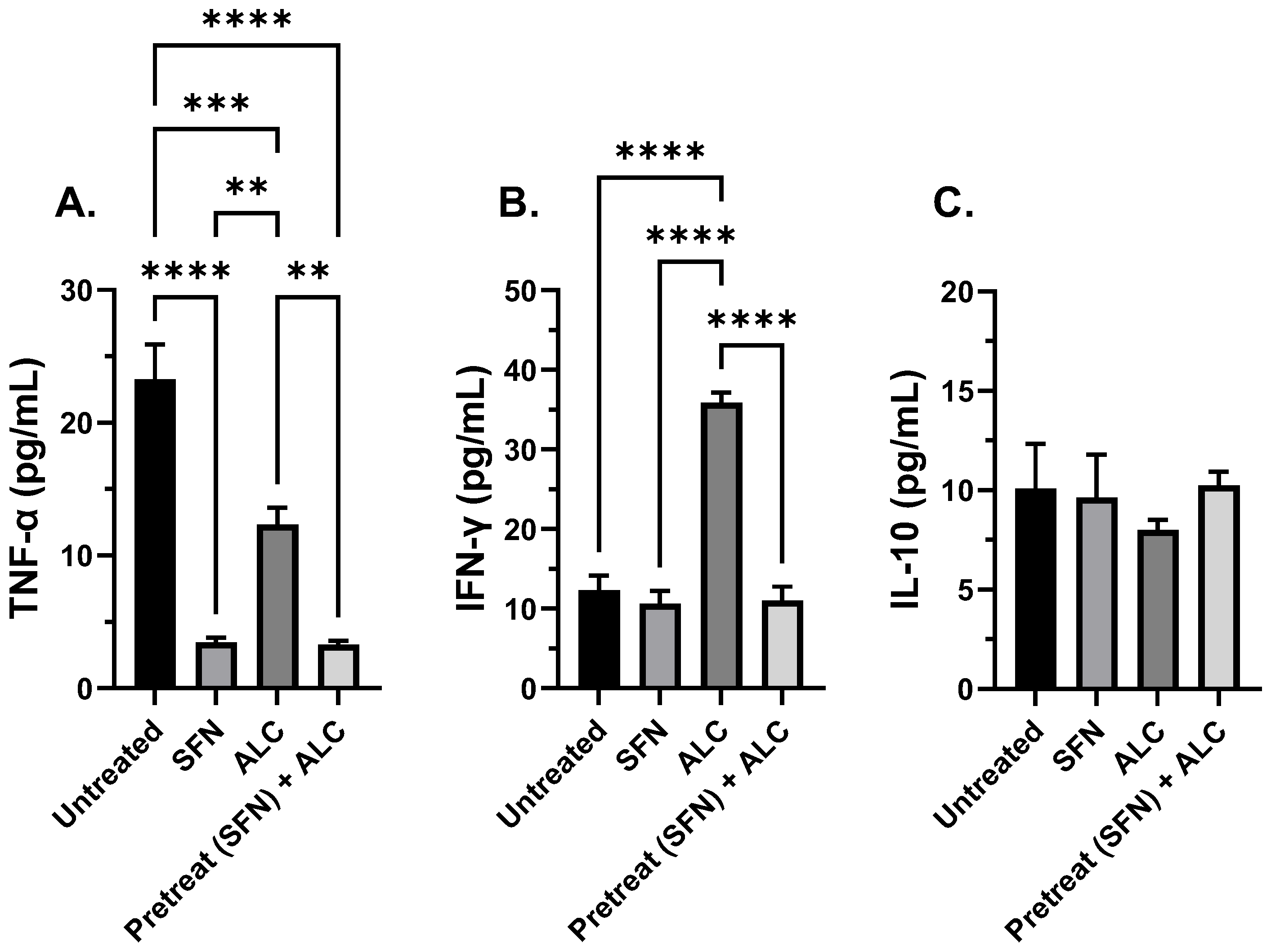

In addition to investigating macrophage function, immunomodulation was tested by measuring critical pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels (i.e., TNF-α, IL-10, and IFN- γ). TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory agent that regulates many facets of macrophage function and has been shown to be one of the most abundant early mediators in inflamed tissue [

46]. IL-10 is a cytokine with potent anti-inflammatory properties, repressing the expression of prominent inflammatory cytokines [

47]. IFN-γ is an autocrine cytokine that enhances the macrophage’s ability to mount an effective immune response, ranging from antigen presentation, autophagy of intracellular pathogens, and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [

48].

Schütze et. al. demonstrated that macrophages exposed to increased levels of IFN-γ while co-stimulated with LPS reduced phagocytosis of

E. coli ten-fold, warranting the measurement of IFN-γ in the presence of SFN [

49].

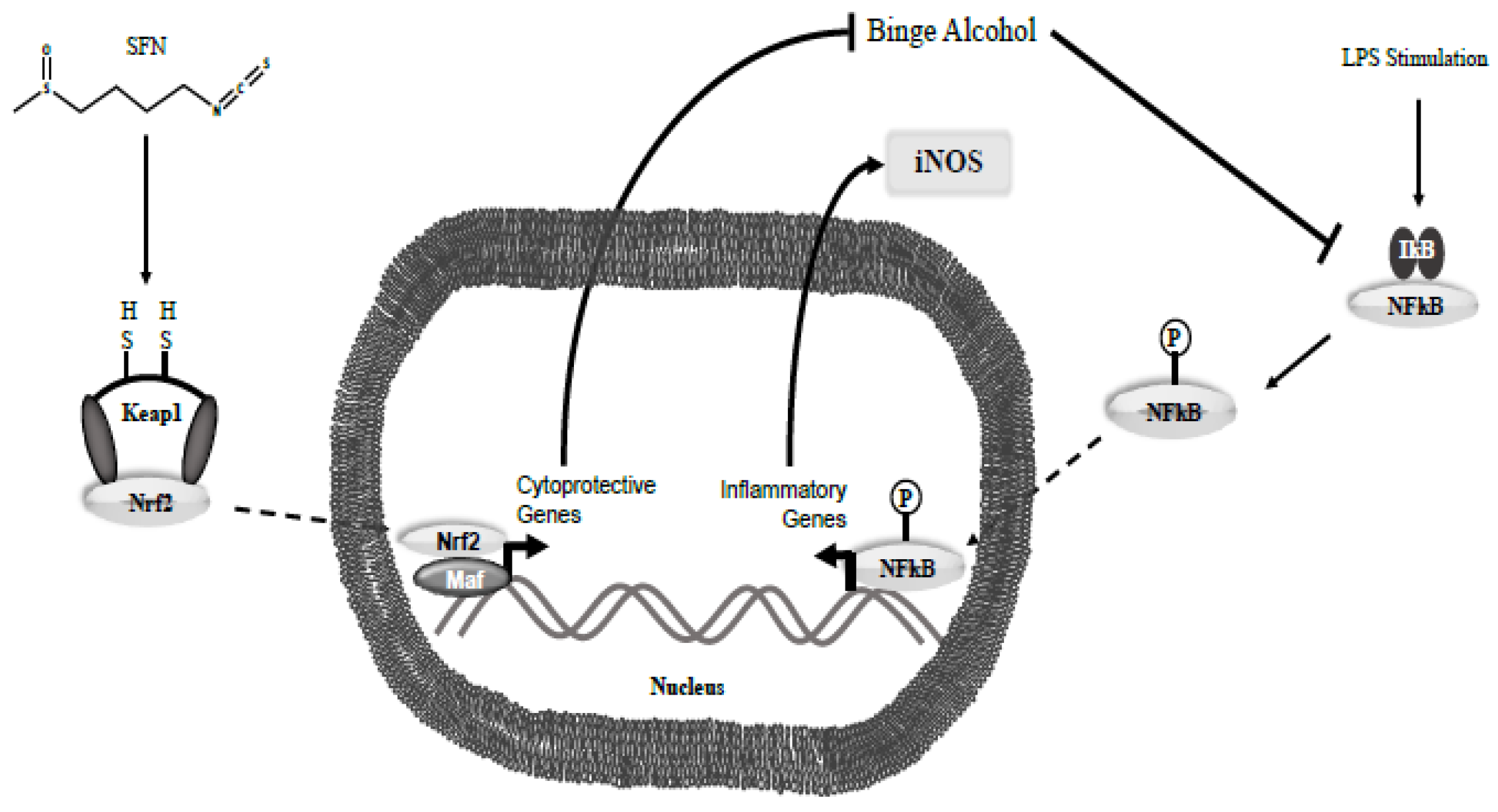

When SFN was administered, a decrease in TNF-α levels along with constant levels of IL-10 in both control and treated populations were observed. In addition, IFN-γ was also measured at elevated levels in longer exposure to alcohol when not pretreated with SFN in both murine and human alveolar macrophages. It is plausible that there are two processes involved in decreasing levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ in the current study:

One, changes in TNF-α expression may be the result of inhibition of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer (NF-kB) pathway, in addition to SFN induced Nrf2 transcription modifications. Alcohol can induce ROS production through several mechanisms such as cytochrome p450 family induction, alteration of metal levels in the body, and antioxidant elimination, leading to a state of oxidative stress [

50]. This increased level of ROS eventually leads to the induction of the NF-kB pathway via inactivation of the IκB subunit, promoting translocation of NF-kB into the nucleus and promoting inflammation, notably with the production of TNF-α [

51]. Although relative levels of TNF-α were lower in alcohol-exposed MH-S and THP-1 cells compared to the negative control, the TNF-α levels were still statistically significantly higher than SFN treated cell lines alone. Similarly, Negi et al. found that treating Neuro2a cells with SFN decreased levels of NF-kB and abrogated high NF-kB levels induced by 30 mM glucose in Neuro2a cells when 0.5 and 1 mg/kg SFN were administered. Subsequent experiments measured TNF-α and IL-6 levels in both diabetic and normoglycemic rats that showed a significant reduction in both parameters when exposed to SFN at 0.5 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg [

52]. Heiss et al. also demonstrated that prophylactic administration of 10-20 µM SFN to RAW 264.7 macrophages prior to LPS induction causes SFN to bind reversibly to Cys residues on NF-kB, inhibiting DNA binding of NF-kB [

53]. Checker et al. additionally found that a 2-hour pretreatment of 20 µM SFN in RAW 264.7 macrophages reduced secretion of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IFN-γ in a concentration-dependent manner [

54].

Furthermore, Gasparello et al. showed the therapeutic potential of SFN as an adjuvant therapy in COVID-19 by demonstrating the ability of SFN to significantly reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-8 as well as reduce the expression of the inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB in bronchial epithelial cells [

43]. These data demonstrate the potential for SFN as an immunotherapy to mitigate infection beyond bacteria to include viruses. Interestingly, Saez et al. discovered that SFN pretreatment of HeLa cells for 24 hours prior to infection with

Chlamydia trachomatis for 24 hours corresponded with a significantly increased number and size of intracellular inclusion bodies indicating a worsening of the infection. Given that SFN is a known inducer of antioxidant genes and

C. trachomatis is an obligatory intracellular bacterium, they hypothesized that an increased quantity of intracellular ROS may be a mechanism by which the cells combat Chlamydia species after they additionally found that inducing intracellular ROS decreased infection burden [

44,

45]. These findings together point to the fact that although SFN may have broad reaching potential for improvement of immune function in Gram-negative, Gram-positive, and even viral infections, there may be some pathogens and associated infectious mechanisms in which SFN may not be a beneficial agent. The current study reinforces the therapeutic potential of SFN as a possible prophylactic measure to prevent some serious nosocomial infections.

Second, additional experiments have demonstrated increased nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and Nrf2 expressions due to SFN treatment [

55]. Given Nrf2’s role in transcription of several anti-oxidation related genes, this could be another possible explanation for the decrease in levels of TNF-α. Previous studies have shown that SFN increases the expression of Nrf2, an important antioxidative transcription factor. To validate the expression of Nrf2 in SFN treated macrophages in the current study, Nrf2 gene expression was measured. A subsequent 3-fold increase in Nrf2 levels was observed when compared to untreated control. To mimic the environment of a Gram-negative bacteria, LPS was added, and a 12-fold increase in Nrf2 expression was noted (Supplemental

Figure 1). These data illustrate that SFN is acting, at least in part, to its upregulation of Nrf2 and continues to suggest that the SFN can effectively serve as potential immuno-treatment to prevent opportunistic infections due to dysfunctional immune response, as seen in binge alcohol intoxication (

Figure 12).

The therapeutic potential of SFN was extended beyond an i

n vitro cell culture model to include an in vivo

G. mellonella model. Colloquially known as waxworms, these species possess a hemolymph system that is like that of the human innate immune system. These larvae are especially useful in studying the relationship between toxins, infections, and the innate immune system, and have been used to study more prominent bacteria and toxins. Several studies have explored the use of SFN within the larvae that focuses on the direct interaction of SFN with

Shigella and

Vibrio spp., not on SFN’s potential ability to bolster the immune system [

56,

57]. Additionally, there is limited literature on the effects of alcohol on the larvae; limited to the threshold dose for alcohol if used as a solvent. Suay-Garcia et. al. demonstrated that alcohol concentrations up to 30% were considered safe to use within the larvae [

58]. Finally,

B. thailandensis has been used in the past in a

G. mellonella model, but there is no literature on the use of

S. epidermidis in the same model [

59]. Ultimately, the

G. mellonella model provides a cheaper yet promising alternative platform to evaluate how alcohol exposure and pathogen challenge interact with SFN prophylaxis in an in vivo model.

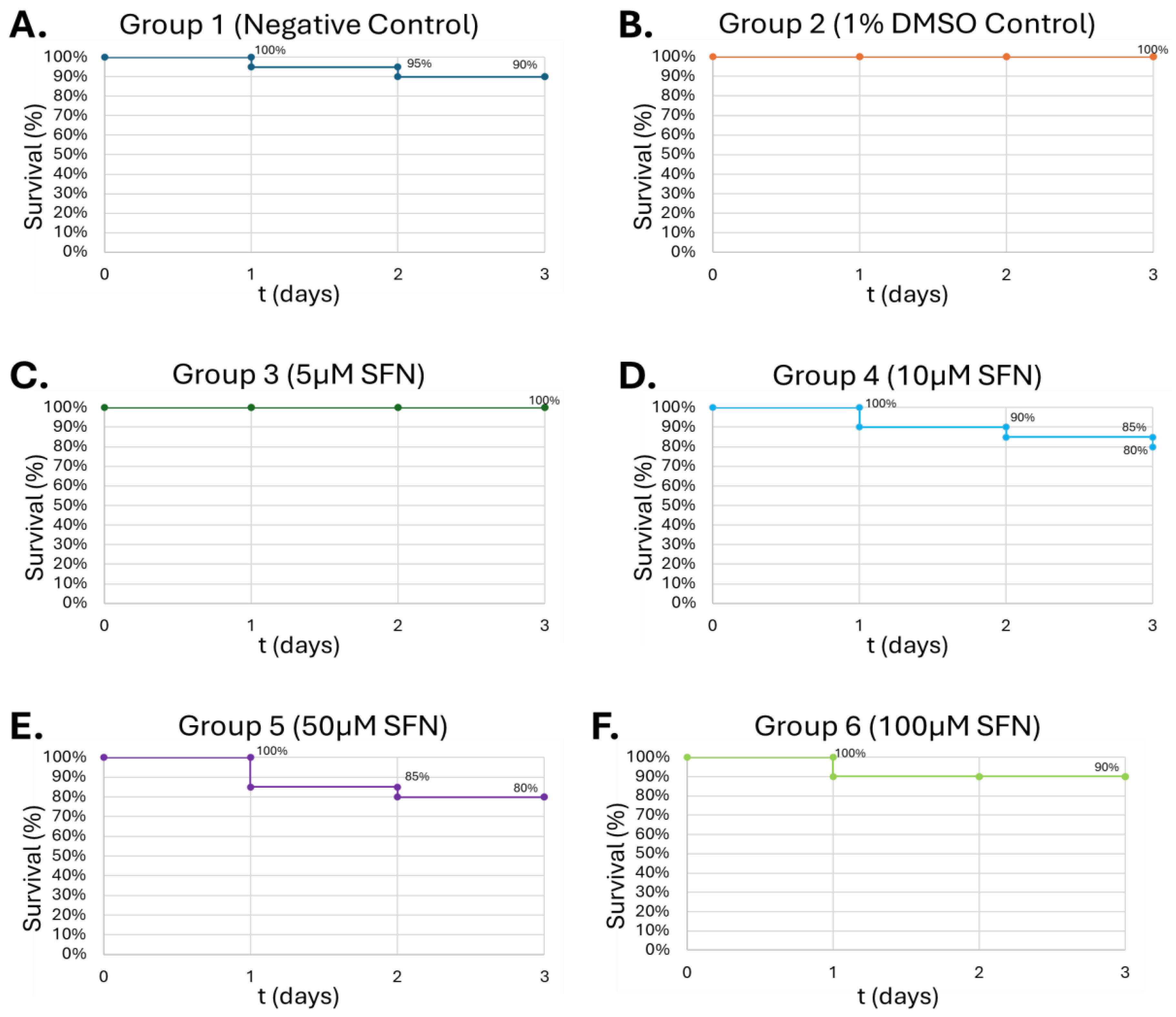

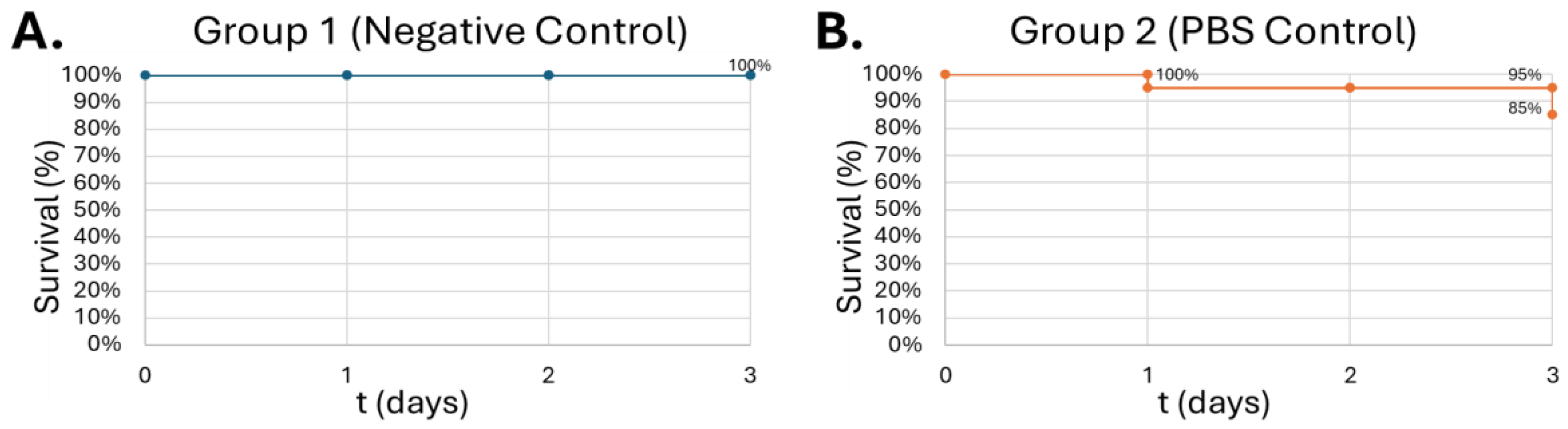

In the current study, waxworms tolerated increasing doses of SFN up to 100 μM, with survivability up to 80% at 50 μM of SFN (

Figure 6). This is consistent with studies by Nowicki et. al. and Krause et. al., which used concentrations up to 25 mg/kg in the larvae and were generally well tolerated [

56,

57]. 100 μM SFN was used for the final study to minimize SFN degradation within the larvae before introducing alcohol. Next, the larvae were injected with increasing concentrations of alcohol. Interestingly, the larvae showed increasing tolerance to alcohol in a dose-dependent manner, showing greatest lethality at 0.08% (v/v) (

Figure 7-C). The typical diet of waxworms contains raw beeswax which may offer some explanation for this tolerance of alcohol at higher concentrations. A similar metabolic trait is present in the Oriental hornet

Vespa orientalis which feed on fermented carbohydrates on top of other insects, creating an adaptation to permit chronic consumption of alcohol in concentrations up to 80% [

60]. Waxworms may share this type of alcohol tolerance. Lower concentrations of alcohol may not reach the required threshold to induce protein expression for alcohol metabolism, which could account for the lethality observed in these experiments. Alcohol concentrations of 0.08% (v/v) were used for future experiments due to the consistent demonstration of the greatest lethal effect on

G. mellonella. This concentration also represents a similar binge-alcohol concentration in humans and helps solidify the model as an analog for human physiology.

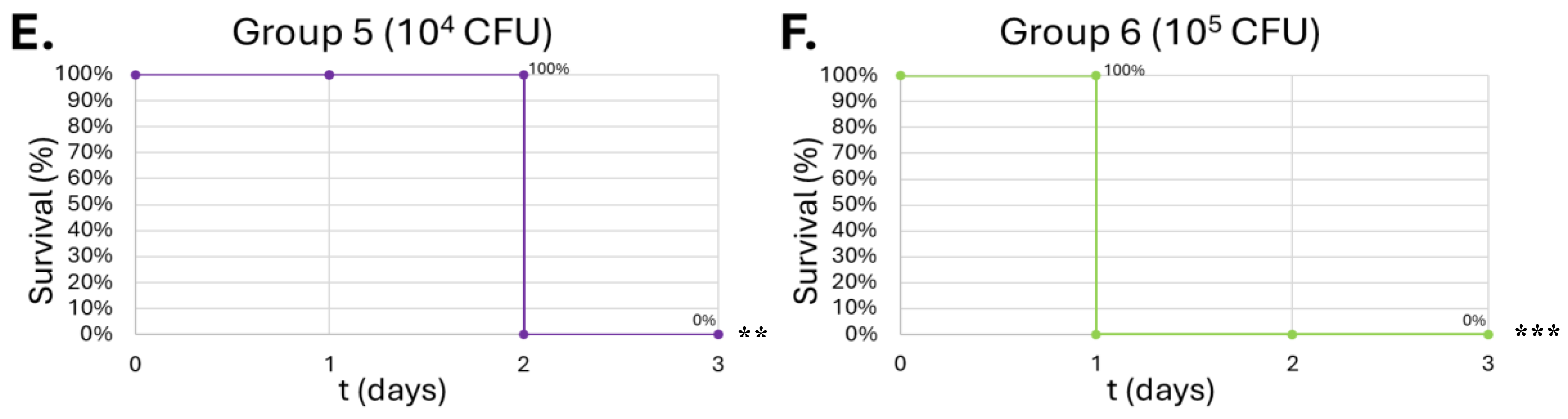

Gram-positive

S. epidermidis and Gram-negative

B. thailandensis were inoculated in the larvae to determine LD

50 of the pathogens. In the

S. epidermidis injections, the survival curve exhibits a dose-dependent lethality on the larvae, showing the greatest lethality at 10

5 CFU at 50% on day 3 (

Figure 9-C).

B. thailandensis injections demonstrated greater lethality compared to

S. epidermidis, due to greater virulence typically observed among Gram-negative bacteria compared to Gram-positive organisms. An LD

50 was observed in concentrations as low as 10

2 CFU, in which that group had 85% lethality by the end of the observation period (

Figure 10-C). Wand et al. produced similar results, where different strains of

B. thailandensis at 10

2 CFU consistently produced mortality within the larvae between 50-80% after a 24-hour observation period [

61]. The dose dependent lethality observed with

S. epidermidis and

B. thailandensis affirms prior findings that

G. mellonella serves as a reliable infection model capable of distinguishing differences in bacterial virulence [

32,

62]. The more lethal outcomes associated with

B. thailandensis are in line with known distinctions between Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms, particularly the role of lipopolysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria that can amplify host immune responses and resistance to clearance [

17].

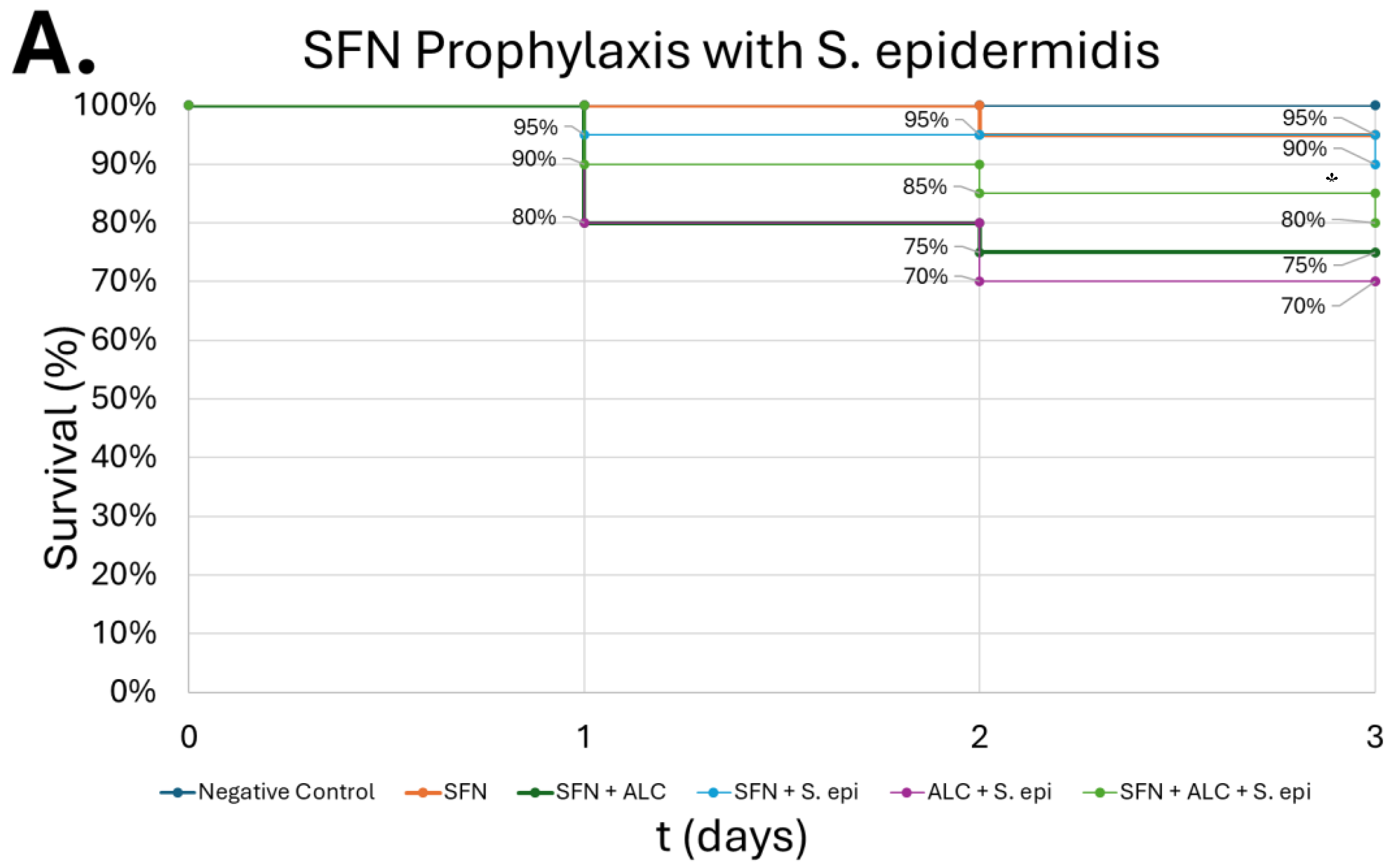

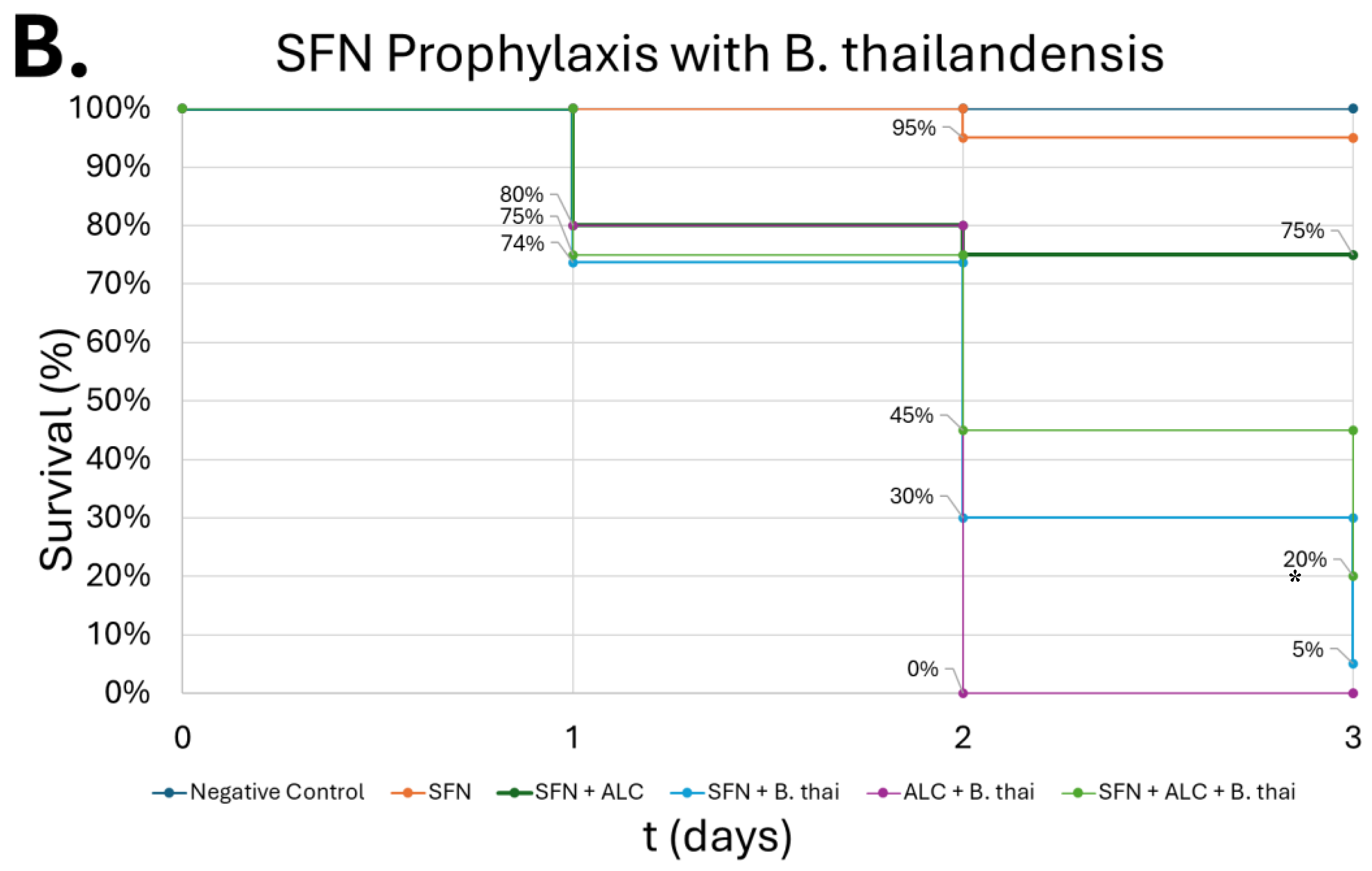

SFN pretreatment presented partial protection against the combined insult of alcohol and infection, improving survivability relative to groups that did not receive the SFN pretreatment (

Figure 11). While the survival rate was not returned to baseline levels, this outcome is consistent with mammalian models where SFN enhanced macrophage phagocytosis and reduced inflammatory dysregulation, even if it did not completely reverse the effects of the pathogen [

32]. These data support the translational relevance of our

G. mellonella findings and suggests that SFN’s protective effects are robust across species. These findings emphasize the promise of SFN as a prophylactic intervention that mitigates alcohol related immune compromise. Building on this work, future studies should integrate transcriptomic or proteomic profiling in

G. mellonella, evaluate a broader spectrum of pathogens, and extend validation to mammalian systems. By doing this, we can better understand the mechanism by which SFN supports host defense and further establish the

G. mellonella model’s potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H., N.C., R.D., D.J., S.Q., B.B., V.T., V.J.; methodology, C.H., N.C., R.D., D.J., S.Q., B.B., V.T., V.J., E.O., ; software, V.J., E.O.; validation, C.H., N.C., R.D., D.J., S.Q., B.B., V.T., V.J., E.O.; formal analysis, V.J.; investigation, , C.H., N.C., R.D., D.J., S.Q., B.B., V.T., V.J., E.O., F.P.M.; resources, V.J., T.T., F.P.M.; data curation, V.J. writing—original draft preparation, C.H., N.C., R.D., D.J., S.Q., B.B., V.T.; writing—review and editing, V.J.; visualization, V.J.; supervision, S.Q., R.D., D.J., V.J.; project administration, V.J., F.P.M.; funding acquisition, V.J., T.T., F.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

G. mellonella larvae were injected on day 0 with a SFN pre-treatment in the caudal prolegs. Eighteen hours later, larvae received injections of alcohol, followed three hours later by inoculation with B. thailandensis or S. epidermidis. The larvae were monitored over the course of three days for change in activity and color.

Figure 1.

G. mellonella larvae were injected on day 0 with a SFN pre-treatment in the caudal prolegs. Eighteen hours later, larvae received injections of alcohol, followed three hours later by inoculation with B. thailandensis or S. epidermidis. The larvae were monitored over the course of three days for change in activity and color.

Figure 2.

MH-S cell viability (A) and THP-1 cell viability (B). Murine MH-S and human THP-1 cell monolayers were treated with media supplemented with 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, or 50 µM SFN. MH-S and THP-1 cells were treated for 2 or 24 hours. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by one-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks * p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

MH-S cell viability (A) and THP-1 cell viability (B). Murine MH-S and human THP-1 cell monolayers were treated with media supplemented with 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, or 50 µM SFN. MH-S and THP-1 cells were treated for 2 or 24 hours. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by one-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks * p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

MH-S cell viability (A) and THP-1 cell viability (B). Murine MH-S and human THP-1 cell monolayers were treated with media supplemented with 0.08%, 0.2% 0.4% alcohol (v/v) for 3 or 24 hours. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by one-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks * p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

MH-S cell viability (A) and THP-1 cell viability (B). Murine MH-S and human THP-1 cell monolayers were treated with media supplemented with 0.08%, 0.2% 0.4% alcohol (v/v) for 3 or 24 hours. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by one-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks * p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

MH-S cell intracellular killing (A) and THP-1 intracellular killing (B). Murine MH-S and human THP-1 cell monolayers were pretreated with media supplemented with 5 μM SFN for 24 hours, rinsed and challenged with 0.2% alcohol (v/v) for 3- or 8-hours; bacterial infection occurred concurrently for 3 or 8 hours. Groups represent the following: untreated = baseline phagocytosis, no sulforaphane (SFN), no alcohol (ALC); SFN = cells pretreated with SFN, no alcohol; ALC = cells challenged with ALC, no SFN; SFN + ALC = cells pretreated with SFN and challenged with ALC. All groups were challenged with live bacteria. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by two-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks *** p < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

MH-S cell intracellular killing (A) and THP-1 intracellular killing (B). Murine MH-S and human THP-1 cell monolayers were pretreated with media supplemented with 5 μM SFN for 24 hours, rinsed and challenged with 0.2% alcohol (v/v) for 3- or 8-hours; bacterial infection occurred concurrently for 3 or 8 hours. Groups represent the following: untreated = baseline phagocytosis, no sulforaphane (SFN), no alcohol (ALC); SFN = cells pretreated with SFN, no alcohol; ALC = cells challenged with ALC, no SFN; SFN + ALC = cells pretreated with SFN and challenged with ALC. All groups were challenged with live bacteria. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by two-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks *** p < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Cytokine expression after 3-hours alcohol exposure. TNF-α (A), IFN-γ (B), and IL-10 (C). Human THP-1 cell monolayers were pretreated with media supplemented with 5 μM SFN for 24 hours, rinsed and challenged with 0.2% alcohol (v/v) and co-cultured with live S. epidermidis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by one-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks *** p < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Cytokine expression after 3-hours alcohol exposure. TNF-α (A), IFN-γ (B), and IL-10 (C). Human THP-1 cell monolayers were pretreated with media supplemented with 5 μM SFN for 24 hours, rinsed and challenged with 0.2% alcohol (v/v) and co-cultured with live S. epidermidis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by one-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks *** p < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

Cytokine expression after 8-hours alcohol exposure. TNF-α (A), IFN-γ (B), and IL-10 (C). Human THP-1 cell monolayers were pretreated with media supplemented with 5 μM SFN for 24 hours, rinsed and challenged with 0.2% alcohol (v/v) and co-cultured with live S. epidermidis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by one-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

Cytokine expression after 8-hours alcohol exposure. TNF-α (A), IFN-γ (B), and IL-10 (C). Human THP-1 cell monolayers were pretreated with media supplemented with 5 μM SFN for 24 hours, rinsed and challenged with 0.2% alcohol (v/v) and co-cultured with live S. epidermidis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant results by one-way ANOVA indicated by asterisks ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001.

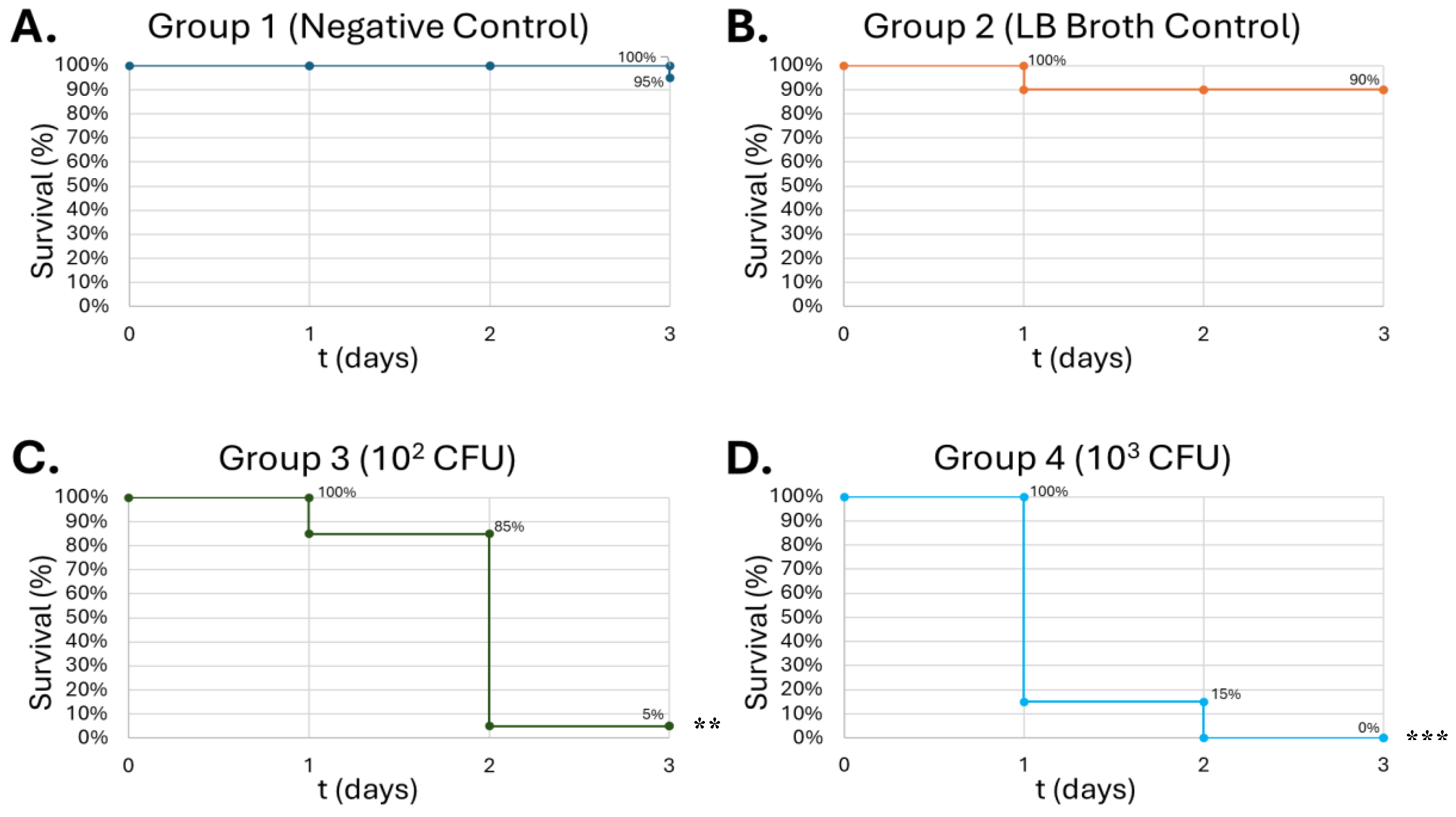

Figure 7.

Survival of G. mellonella larvae after treatment with different concentrations of SFN. Negative control (A) = no injection, vehicle control (B) = vehicle, 5µM (C), 10µM (D), 50µM (E), 100µM (F). Day zero represents the actual day of the inoculation with subsequent days representing 24 h periods. No statistical difference was found between groups.

Figure 7.

Survival of G. mellonella larvae after treatment with different concentrations of SFN. Negative control (A) = no injection, vehicle control (B) = vehicle, 5µM (C), 10µM (D), 50µM (E), 100µM (F). Day zero represents the actual day of the inoculation with subsequent days representing 24 h periods. No statistical difference was found between groups.

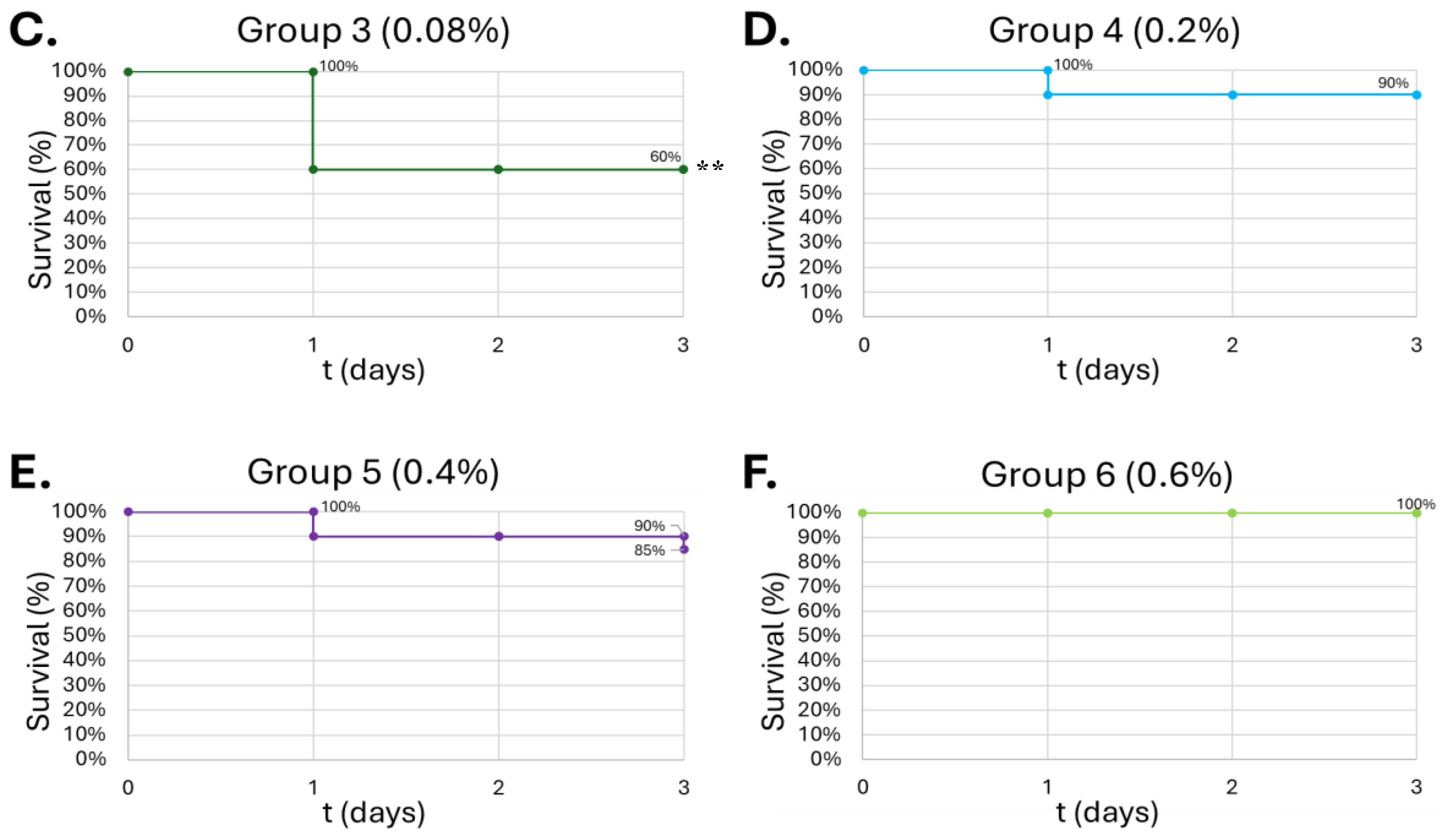

Figure 8.

Survival curve of G. mellonella larvae after 10µL of increasing ALC concentration. Negative control (A) = no injection, PBS control (B) = vehicle, 0.08% (v/v) (C), 0.2% (v/v) (D), 0.4% (v/v) (E), 0.6% (v/v) (F). Day zero = injection day. Asterisks represent statistical differences between untreated control groups and treated groups (survival analysis, p < 0.01, **).

Figure 8.

Survival curve of G. mellonella larvae after 10µL of increasing ALC concentration. Negative control (A) = no injection, PBS control (B) = vehicle, 0.08% (v/v) (C), 0.2% (v/v) (D), 0.4% (v/v) (E), 0.6% (v/v) (F). Day zero = injection day. Asterisks represent statistical differences between untreated control groups and treated groups (survival analysis, p < 0.01, **).

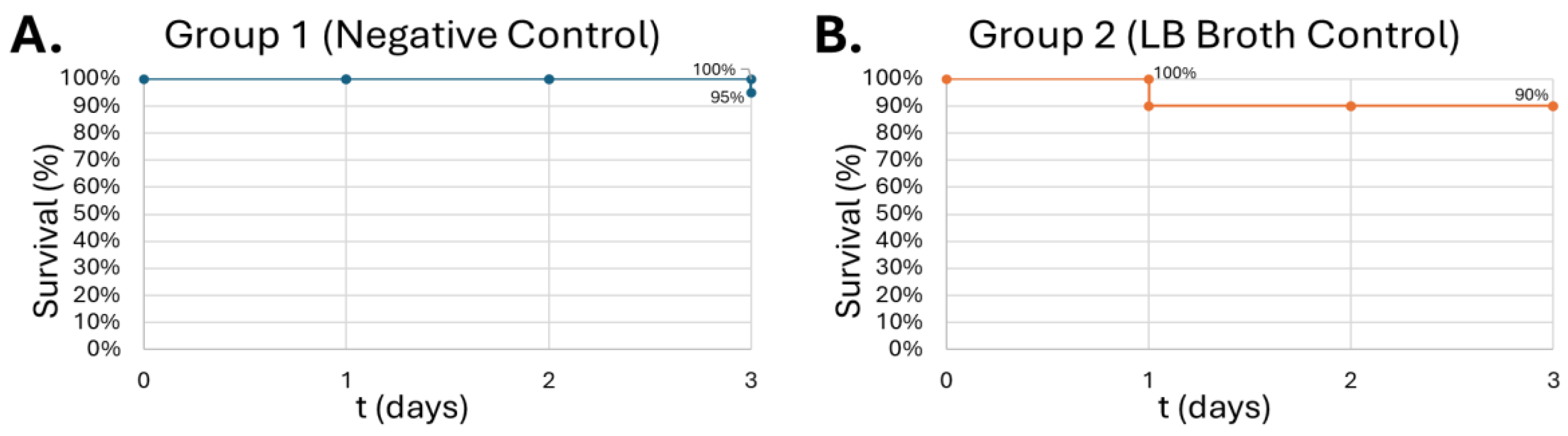

Figure 9.

Survival of G. Mellonella larvae after different doses of S. epidermidis. Negative control (A) = no injection, LB Broth control (B) = vehicle control, 102 CFU (C), 103 CFU (D), 104 CFU (E), 105 CFU (F). Day zero = injection day. Asterisks represent statistical differences between untreated control groups and treated groups (survival analysis, p < 0.01, **).

Figure 9.

Survival of G. Mellonella larvae after different doses of S. epidermidis. Negative control (A) = no injection, LB Broth control (B) = vehicle control, 102 CFU (C), 103 CFU (D), 104 CFU (E), 105 CFU (F). Day zero = injection day. Asterisks represent statistical differences between untreated control groups and treated groups (survival analysis, p < 0.01, **).

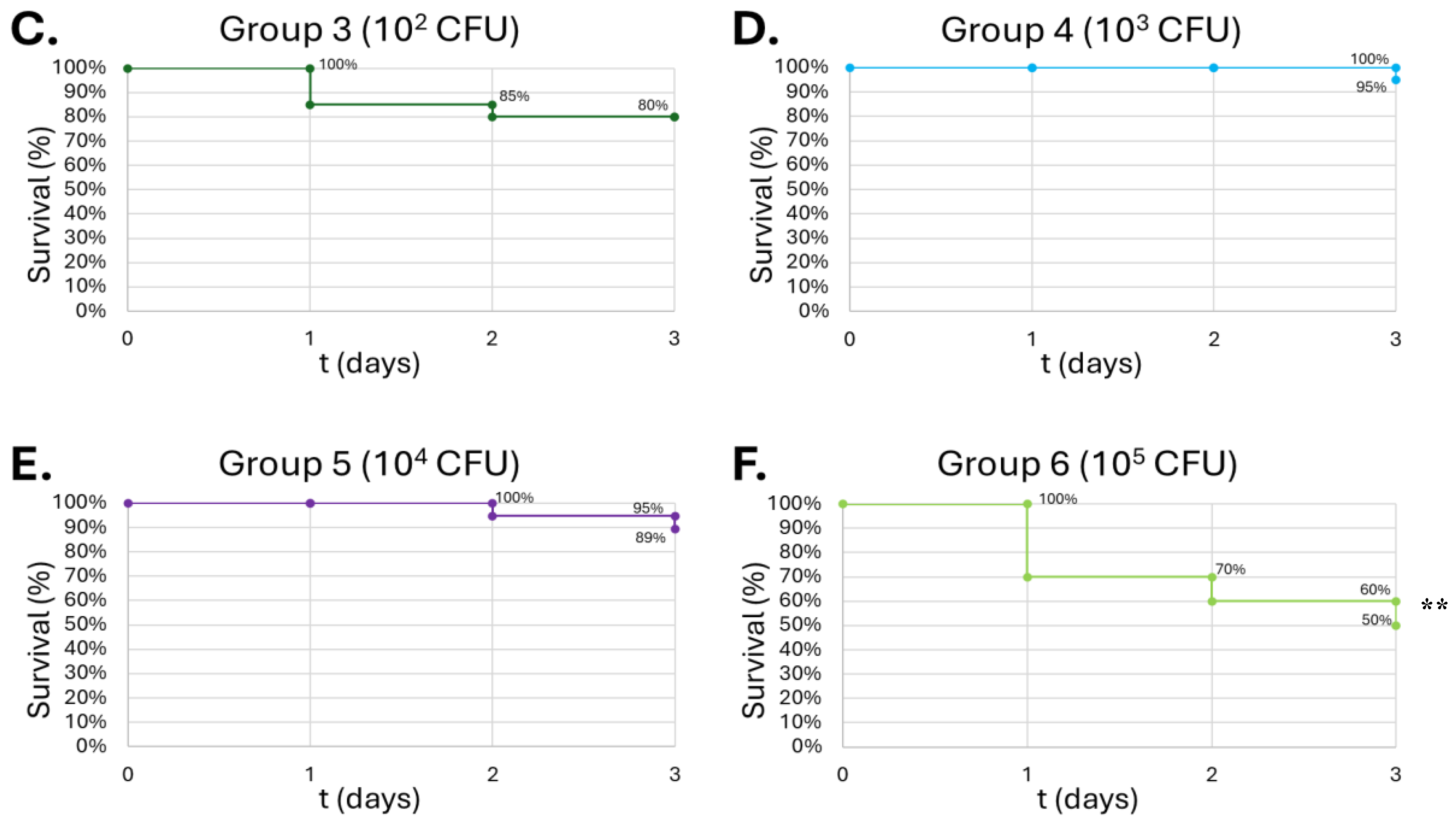

Figure 10.

Survival of G. mellonella larvae after different doses of B. thailandensis. Negative control (A) = no injection, LB Broth control (B) = vehicle control, 102 CFU (C), 103 CFU (D), 104 CFU (E), 105 CFU (F). Day zero = injection day. Asterisks represent statistical differences between untreated control groups and treated groups (survival analysis, p < 0.001, ***).

Figure 10.

Survival of G. mellonella larvae after different doses of B. thailandensis. Negative control (A) = no injection, LB Broth control (B) = vehicle control, 102 CFU (C), 103 CFU (D), 104 CFU (E), 105 CFU (F). Day zero = injection day. Asterisks represent statistical differences between untreated control groups and treated groups (survival analysis, p < 0.001, ***).

Figure 11.

Survival of G. mellonella larvae after SFN prophylaxis from alcohol and bacterial infection insults. S. epidermidis at 105 CFUs (A), B. thailandensis at 102 CFUs (B). Negative control = no injection, Day zero = injection day. Asterisks represent statistical differences between ALC + bacteria group and SFN + ALC + bacteria group (survival analysis, p < 0.05, *).

Figure 11.

Survival of G. mellonella larvae after SFN prophylaxis from alcohol and bacterial infection insults. S. epidermidis at 105 CFUs (A), B. thailandensis at 102 CFUs (B). Negative control = no injection, Day zero = injection day. Asterisks represent statistical differences between ALC + bacteria group and SFN + ALC + bacteria group (survival analysis, p < 0.05, *).

Figure 12.

Hypothesis for the SFN mechanism to counteract effects of binge alcohol use. SFN enables detachment of Keap-1 (endogenous cytoplasmic inhibitor) from Nrf2 transcription factor. Subsequent Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus allows for transcription of cytoprotective genes against alcohol insult. Thus, SFN modulates the inflammatory response through means such as NF-kB.

Figure 12.

Hypothesis for the SFN mechanism to counteract effects of binge alcohol use. SFN enables detachment of Keap-1 (endogenous cytoplasmic inhibitor) from Nrf2 transcription factor. Subsequent Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus allows for transcription of cytoprotective genes against alcohol insult. Thus, SFN modulates the inflammatory response through means such as NF-kB.