Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

20 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Treatments

2.2. Preparation and Component Detection of BT

2.2.1. Preparation of BT

2.2.2. Component Detection of BT

2.3. Determination of Immunoglobulin

2.4. Detection of Oxidative Stress Levels

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.6. SCFAs Content Measurement

2.7. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis of Cecal and Pulmonary Microbiota

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

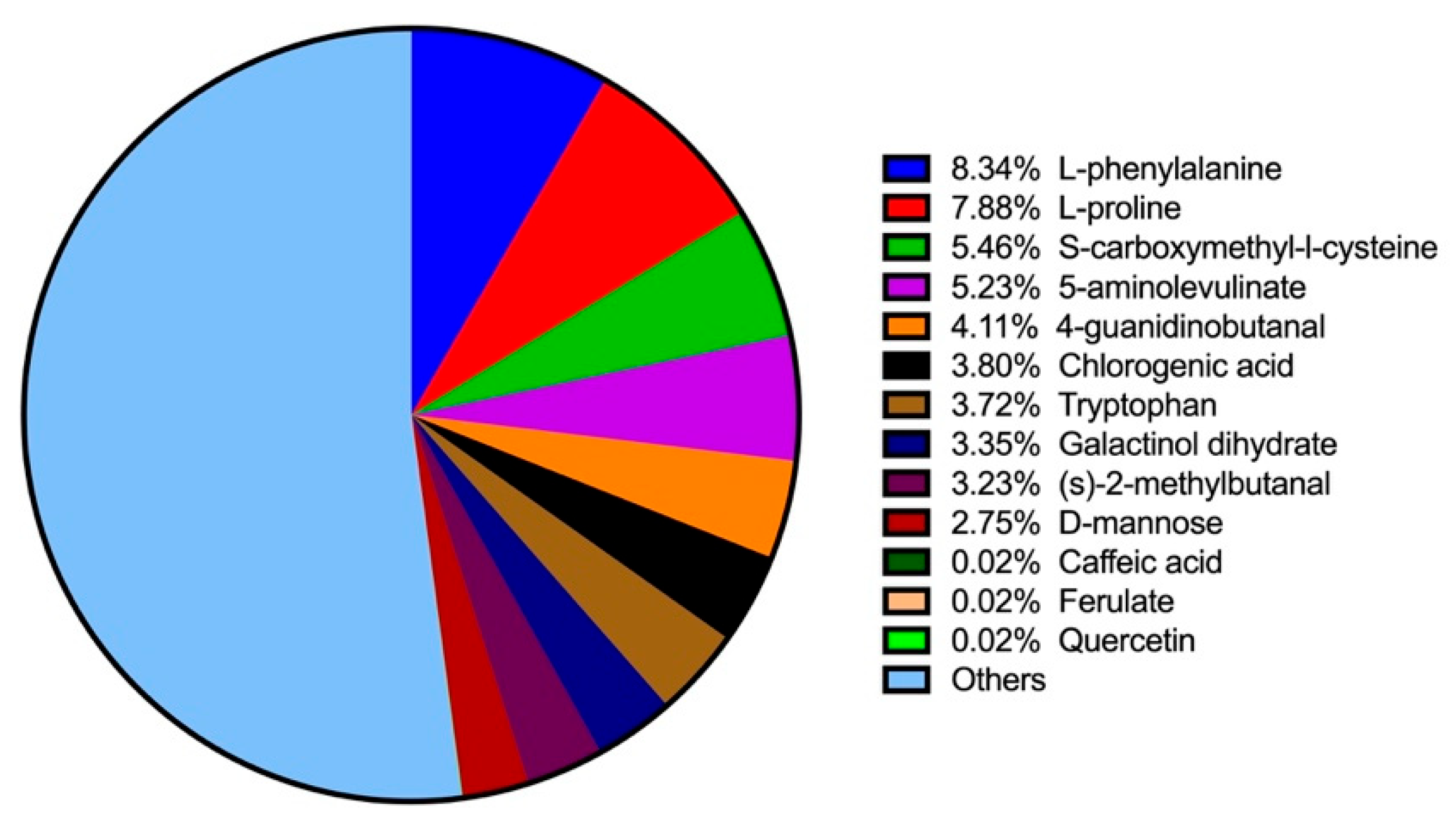

3.1. The Components of BT

3.2. Effect of BT on Growth and Organ Indices

3.3. Effect of BT on Immunoglobulin Levels

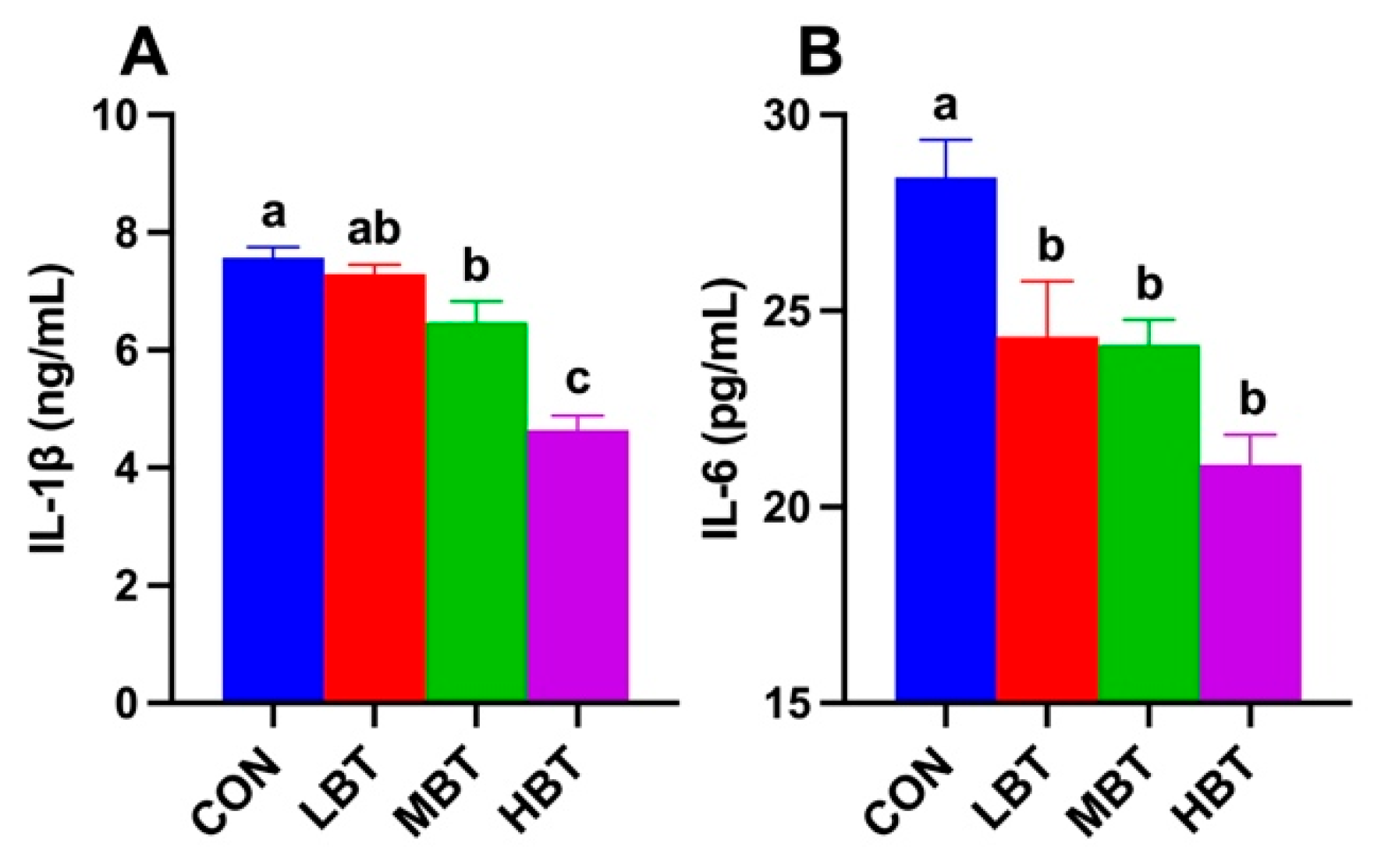

3.4. Effect of BT on Levels of MDA, SOD and CAT Activity

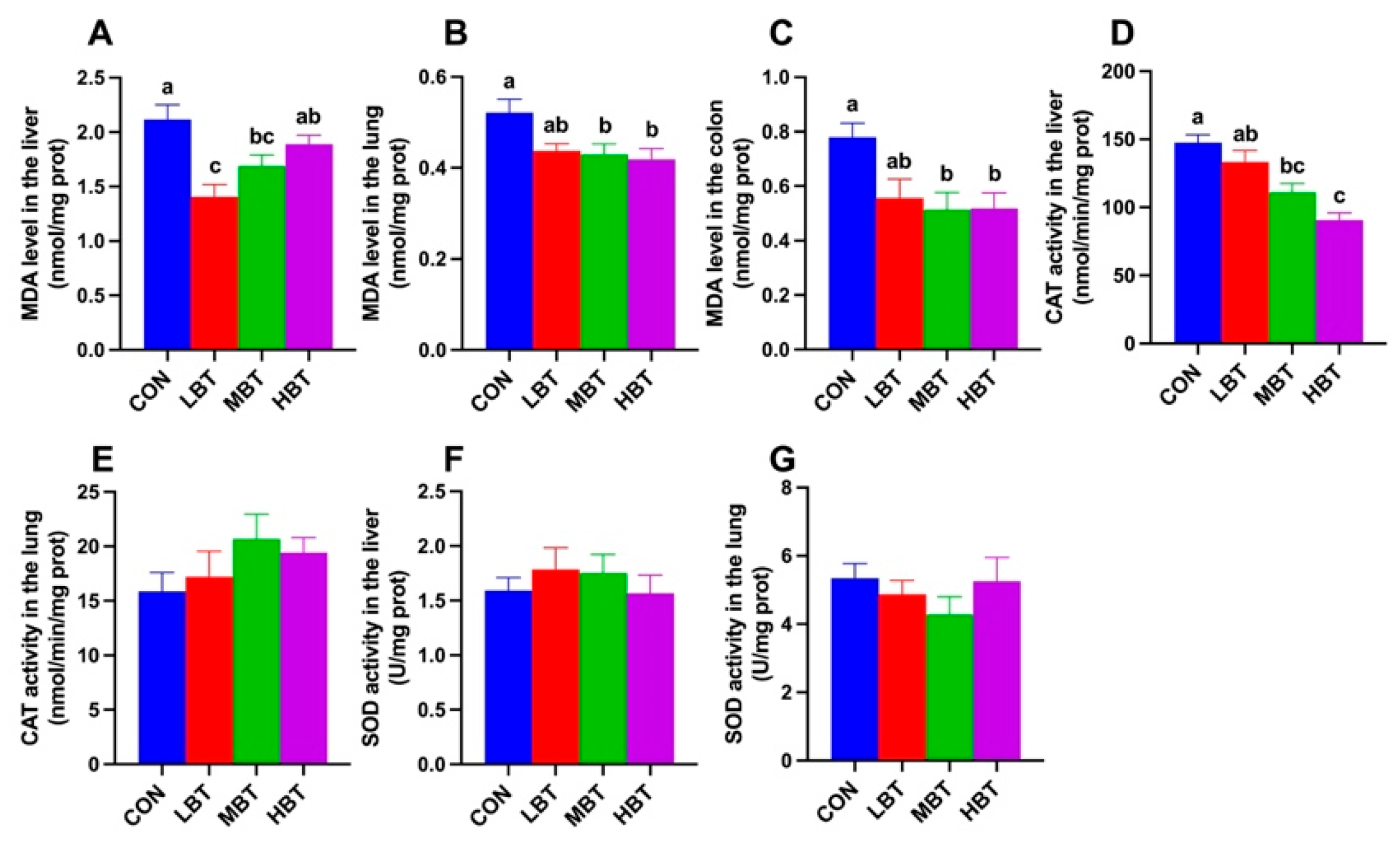

3.5. Effect of BT on Cecal Microbiota

3.5.1. ASVs Analysis of Cecal Microbiota

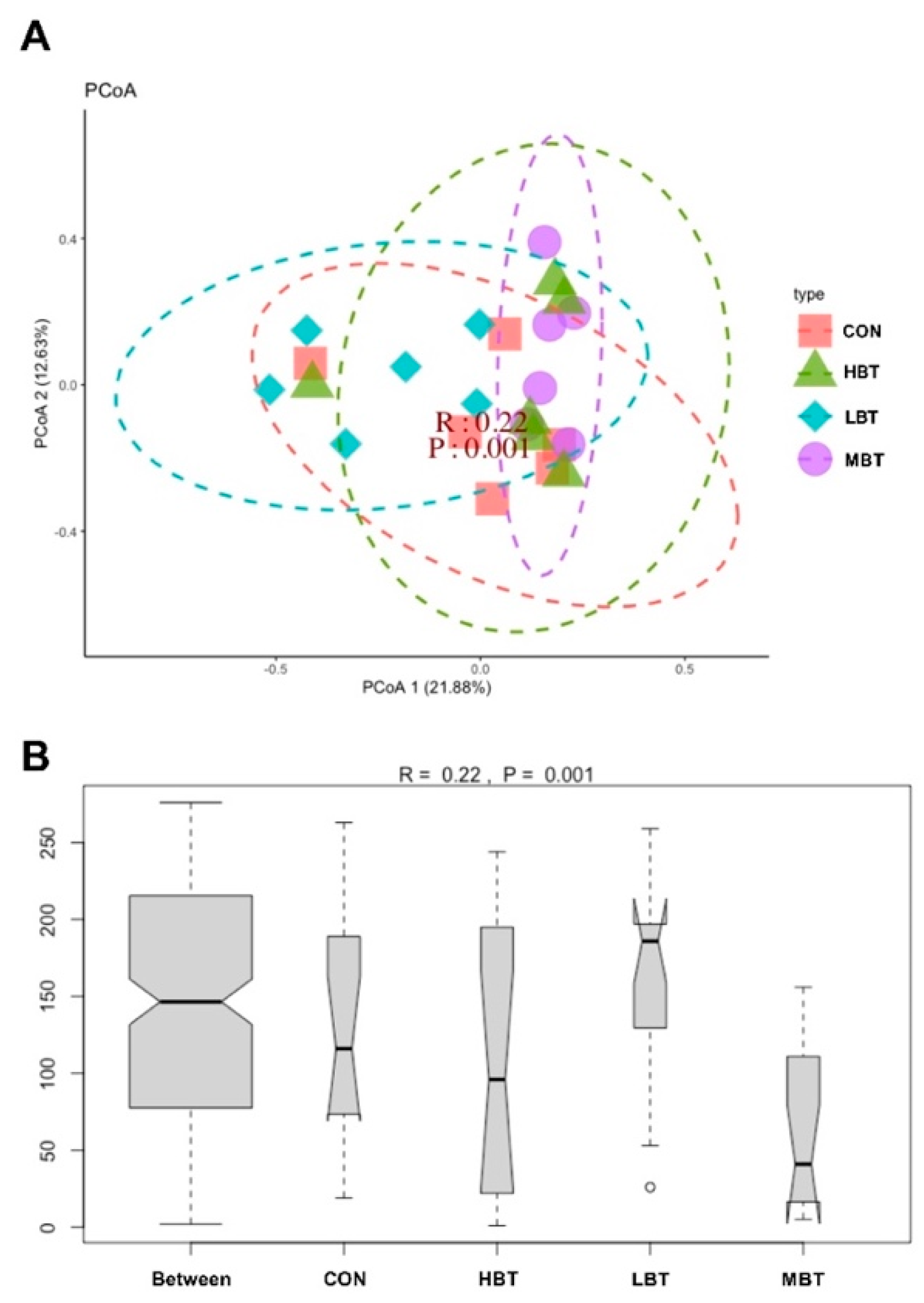

3.5.2. Differences in Diversities of Cecal Microbial Community

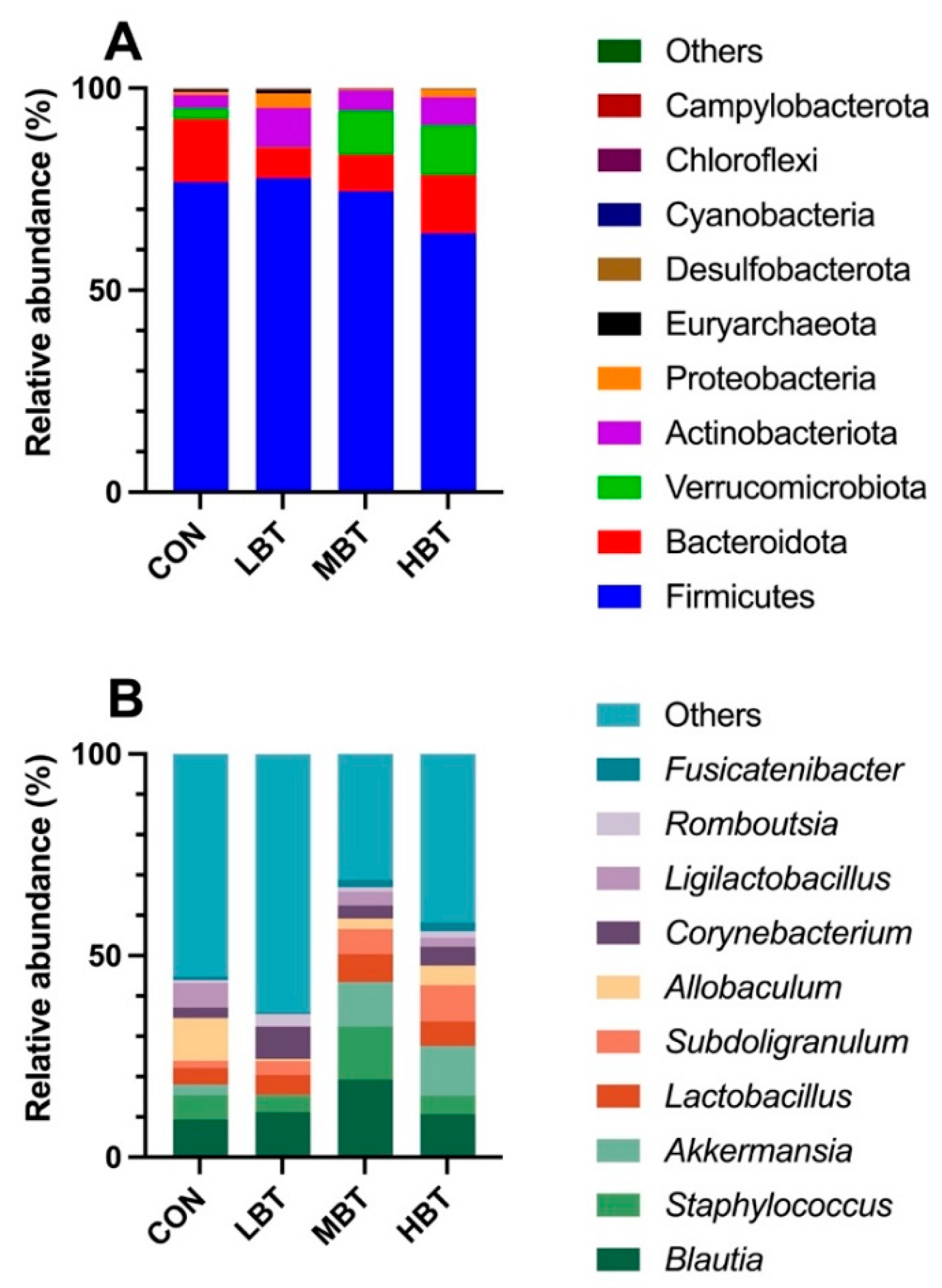

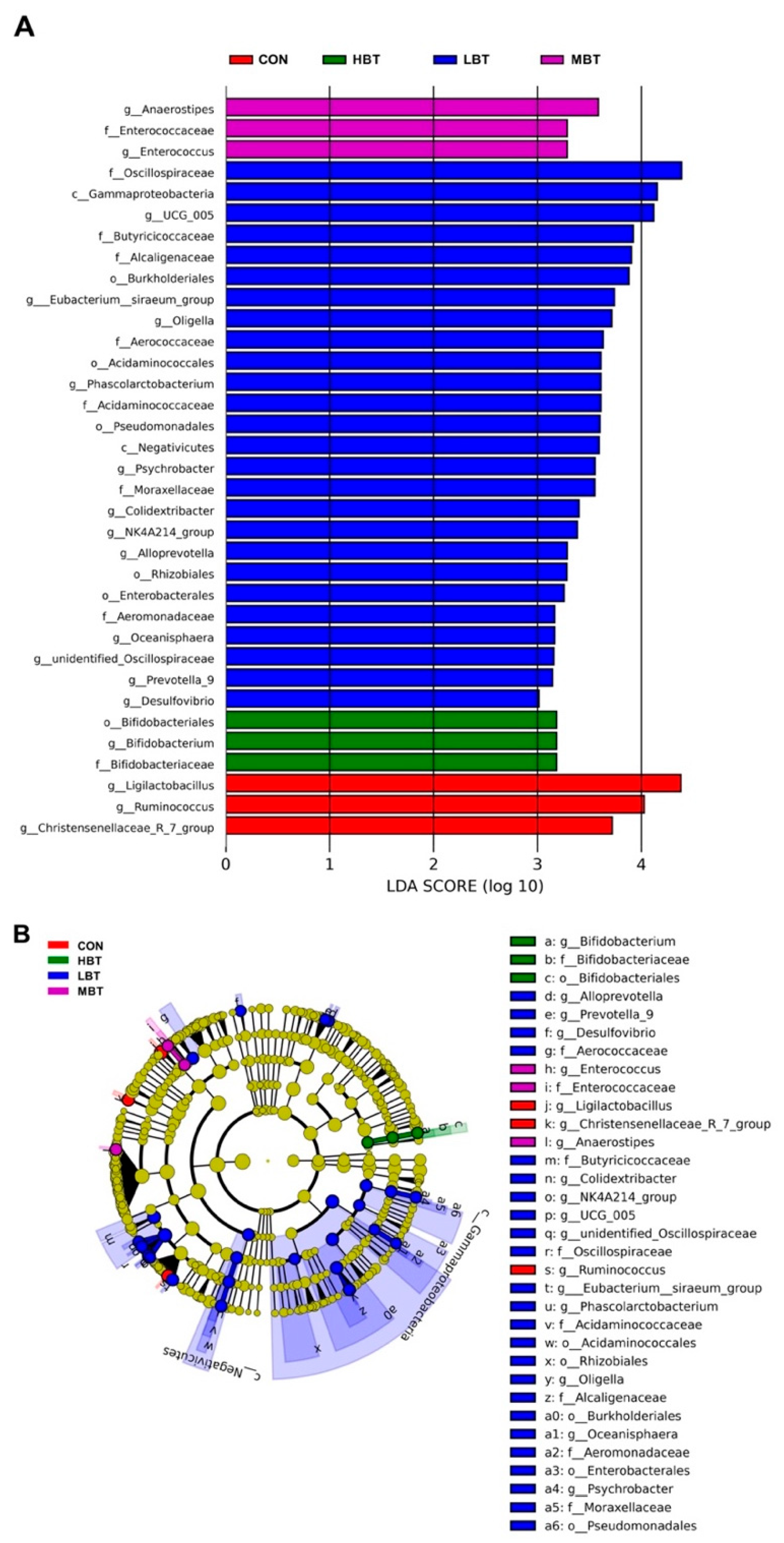

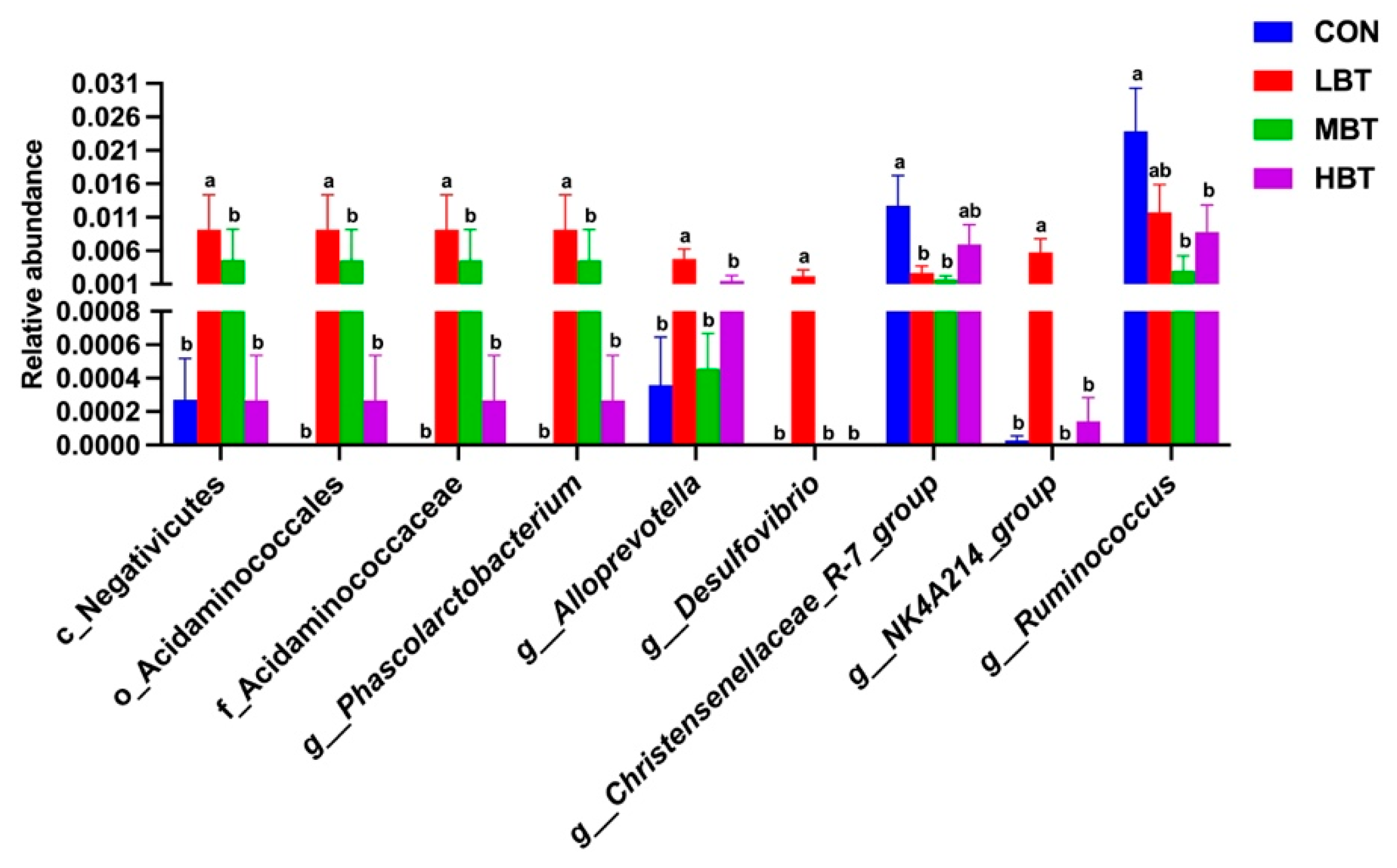

3.5.3. Differences in Abundances of Cecal Microbiota

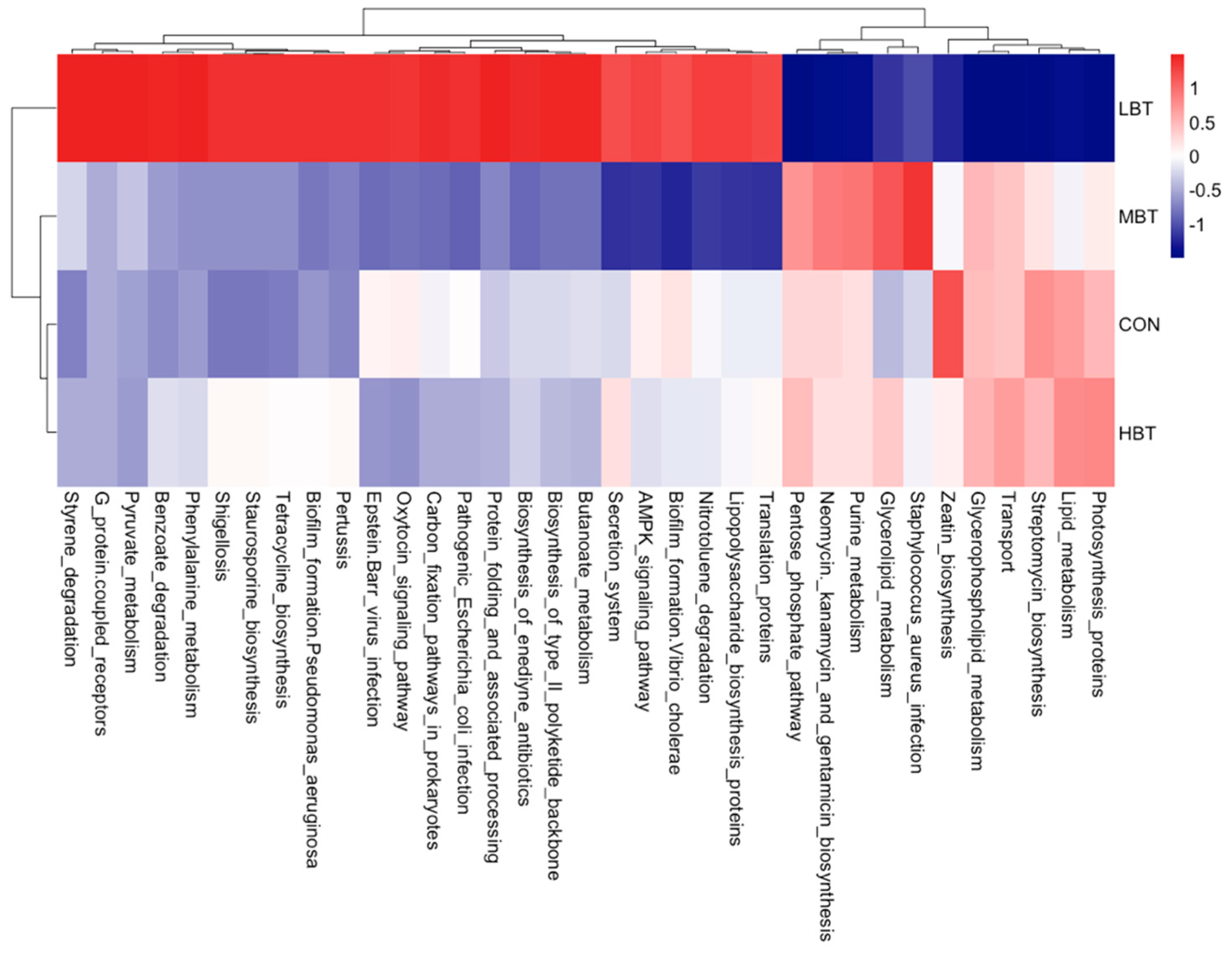

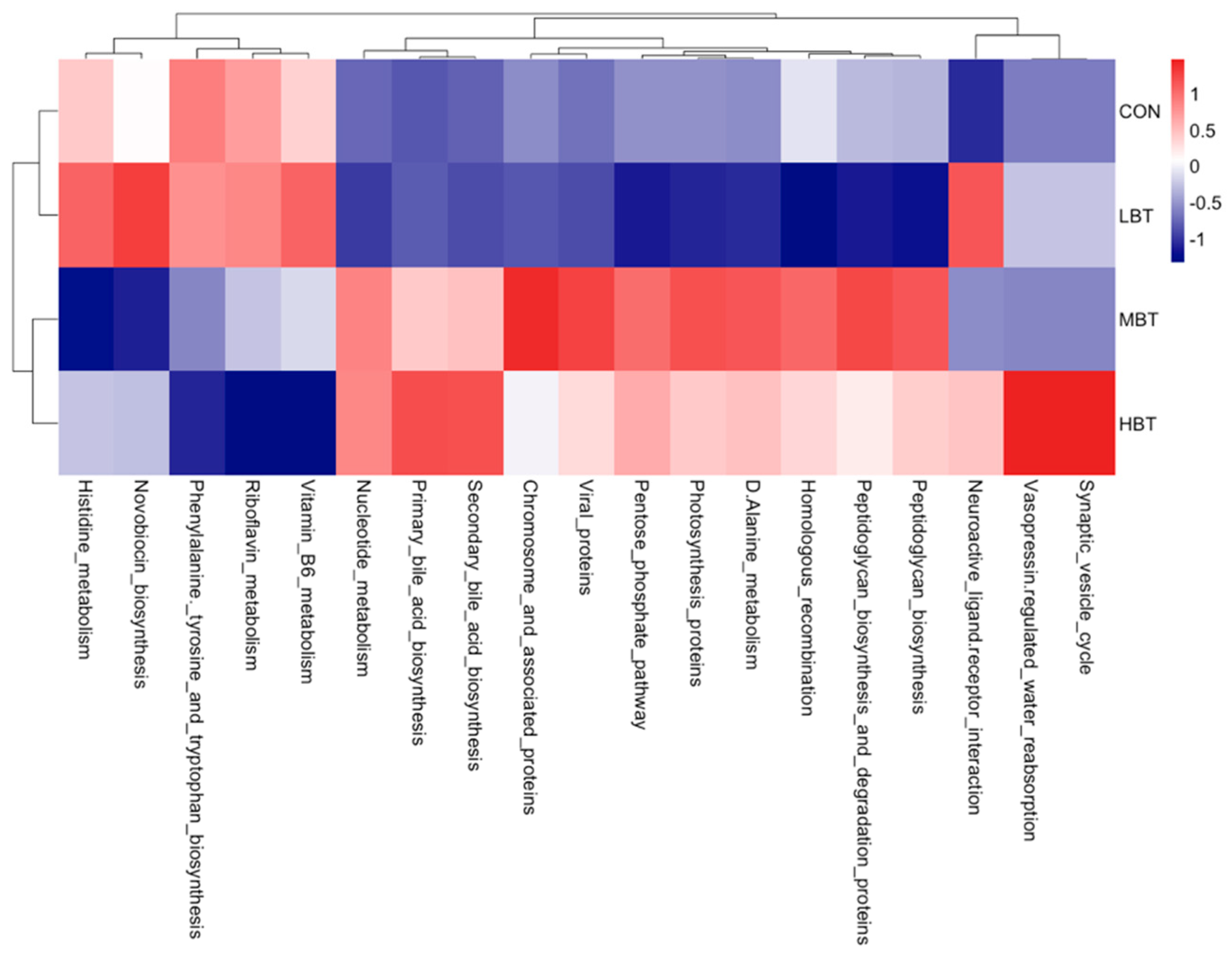

3.5.4. Differences in Abundances of Cecal Predicted Microbial Function

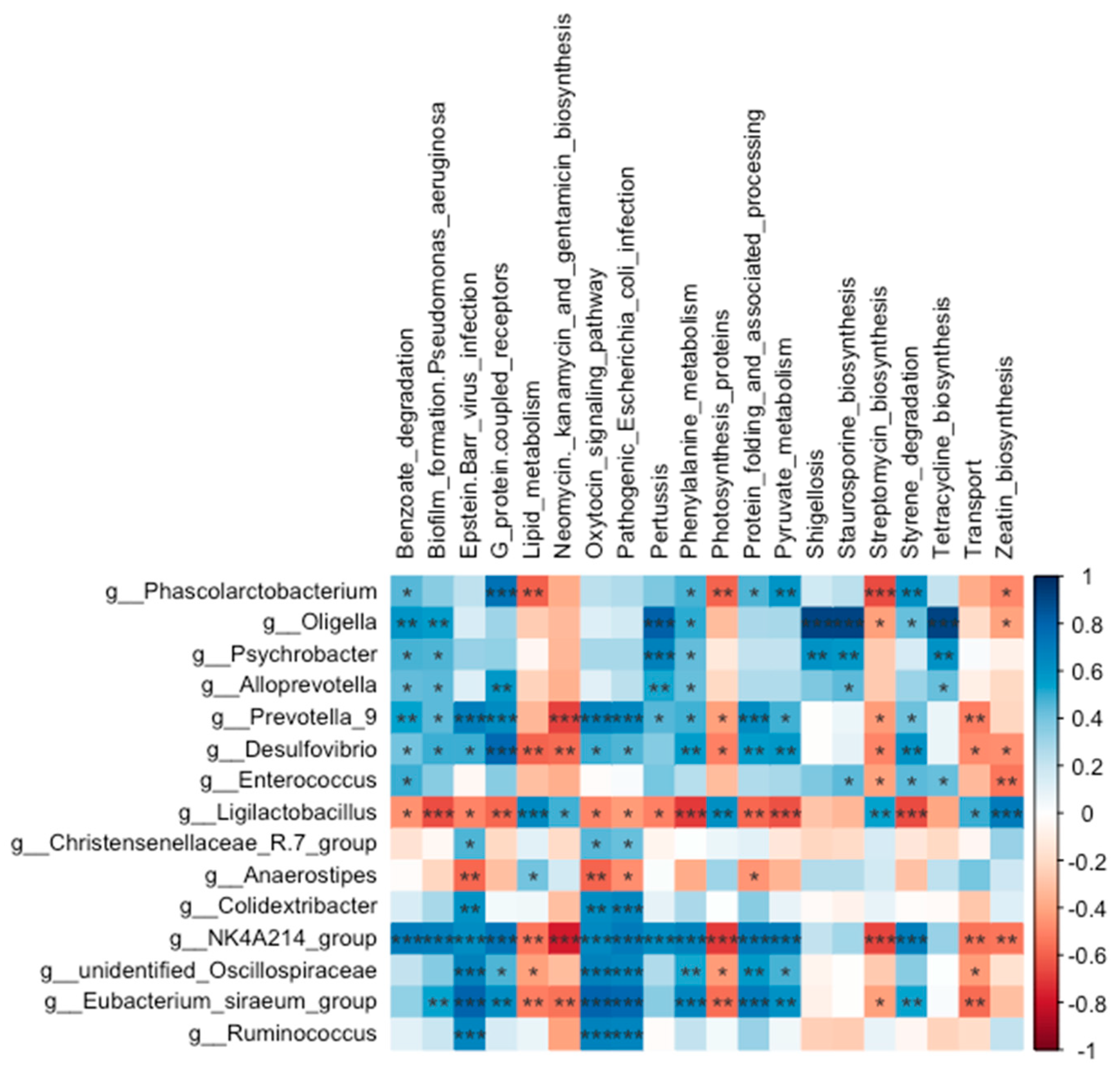

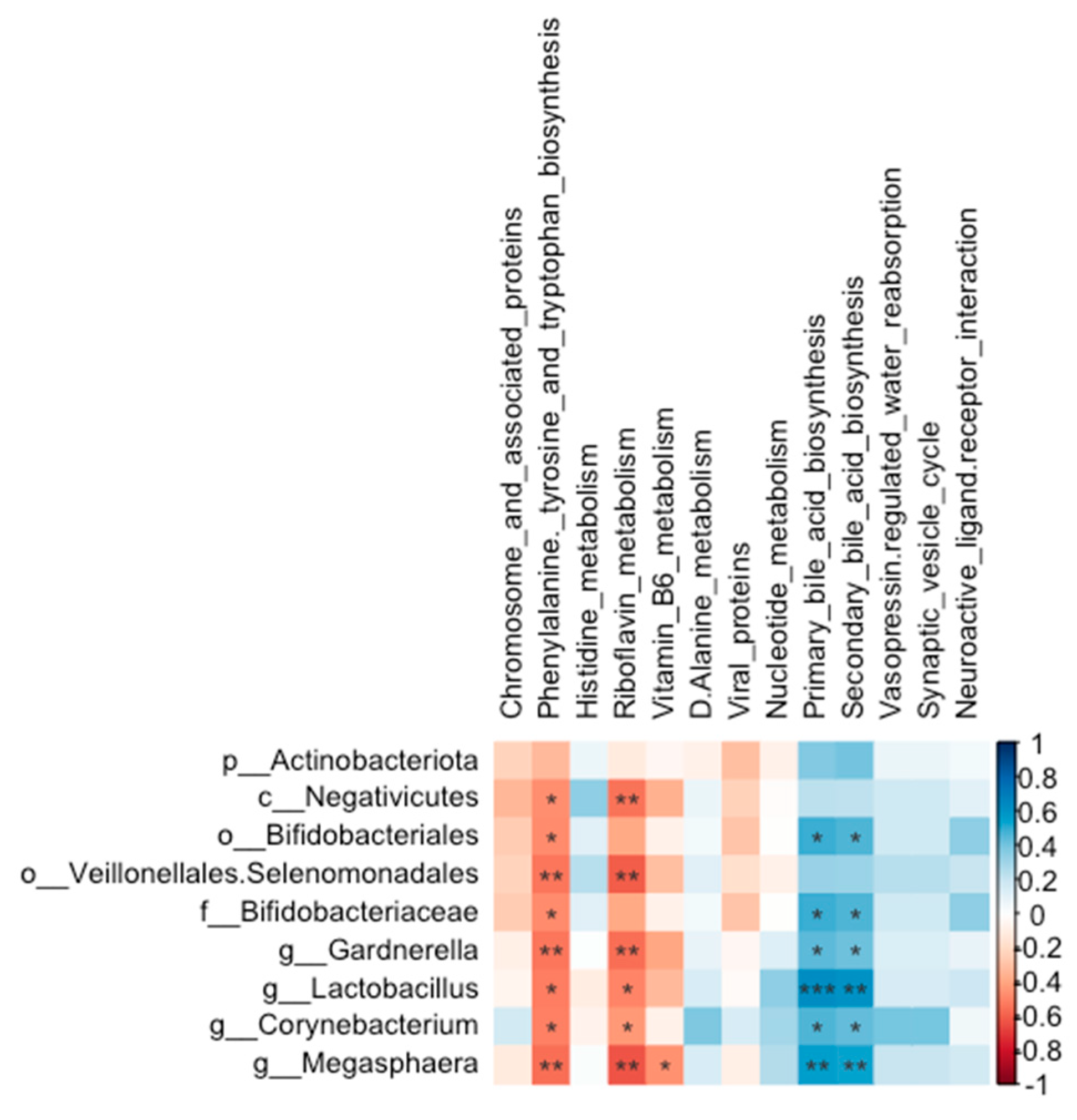

3.5.5. Relationship Between Abundances of Cecal Microbiota and Predicted Microbial Function

3.6. Effect of BT on Pulmonary Microbiota

3.6.1. ASVs Analysis of Pulmonary Microbiota

3.6.2. Differences in Diversities of Pulmonary Microbial Community

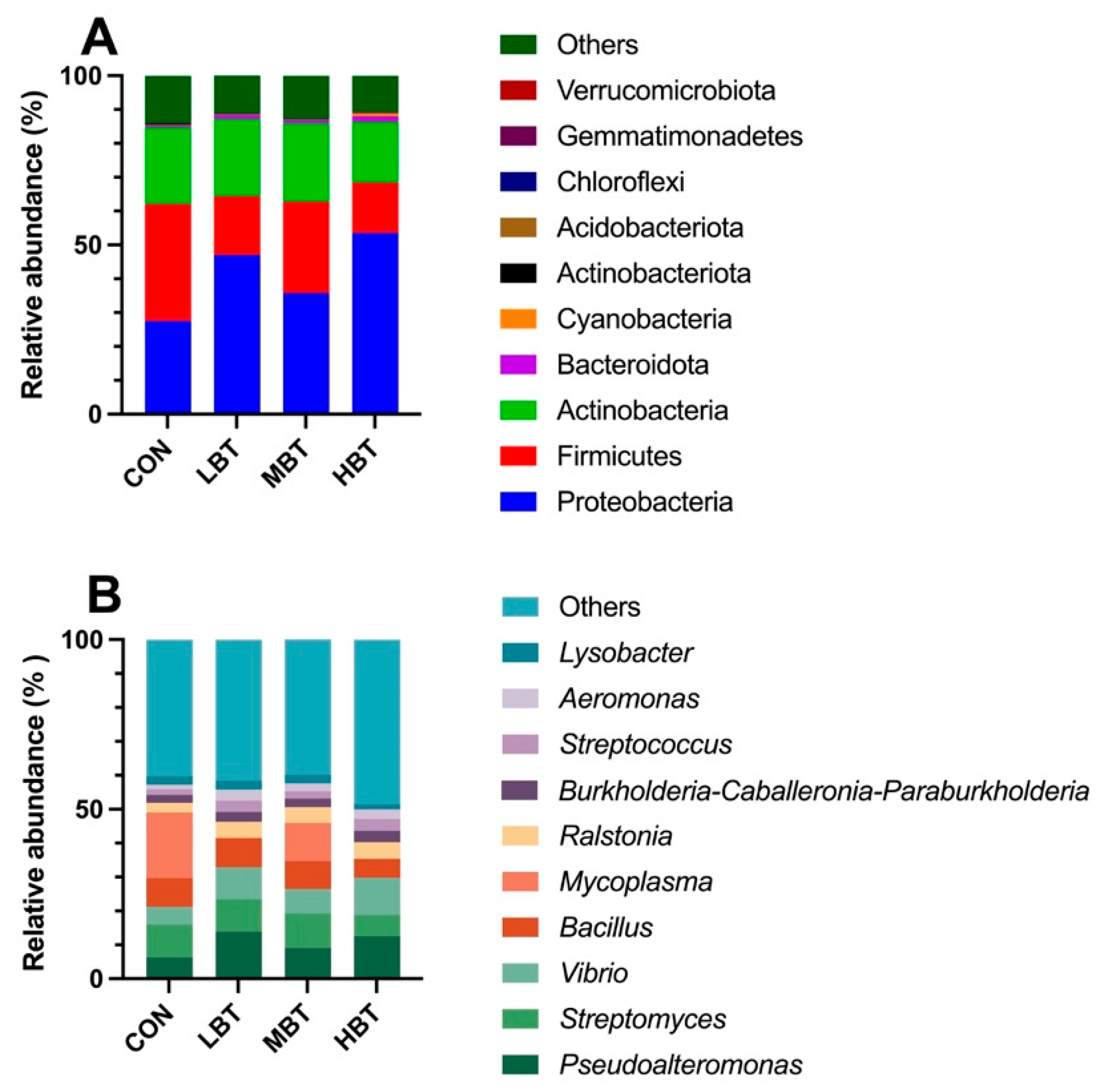

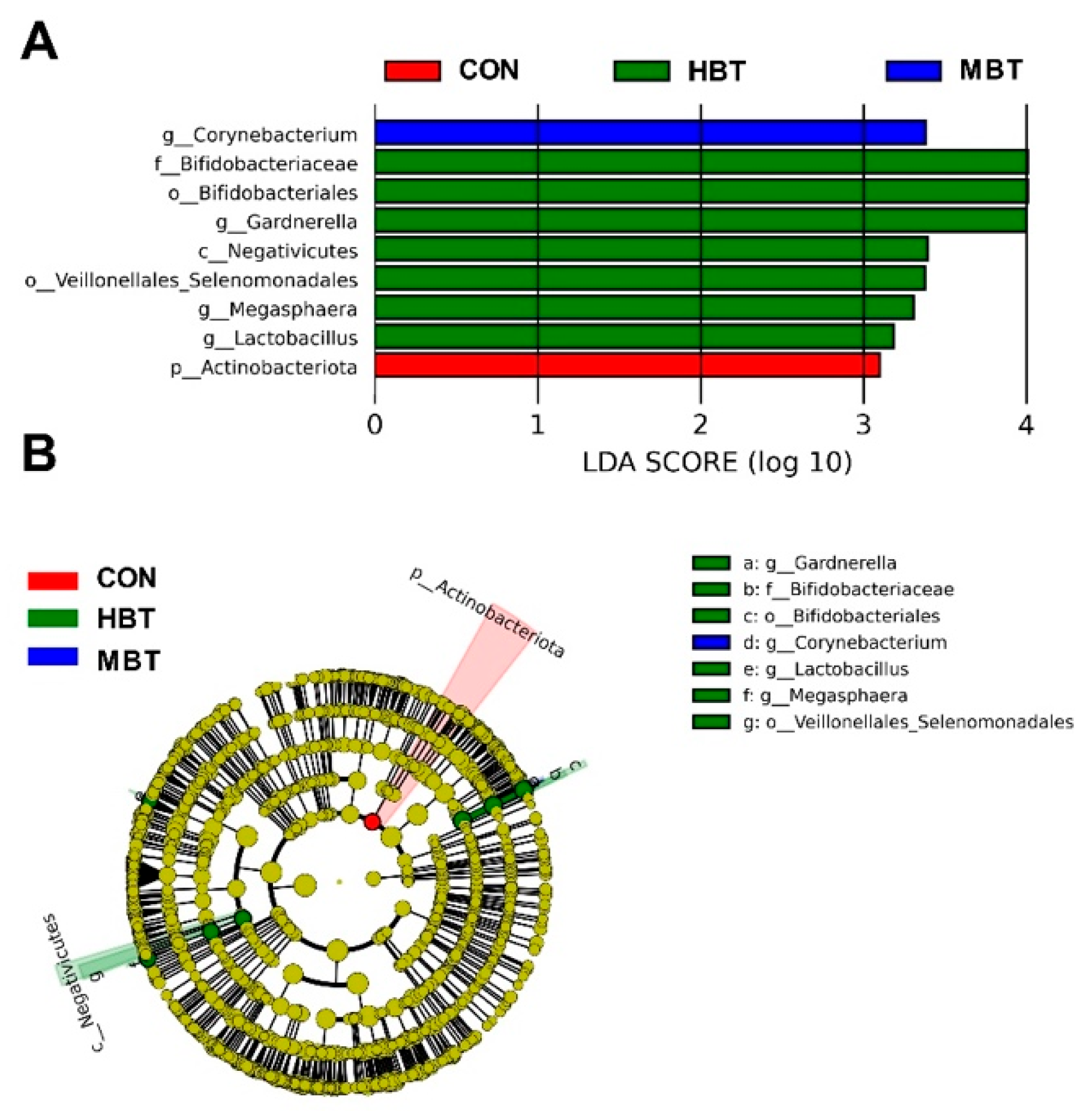

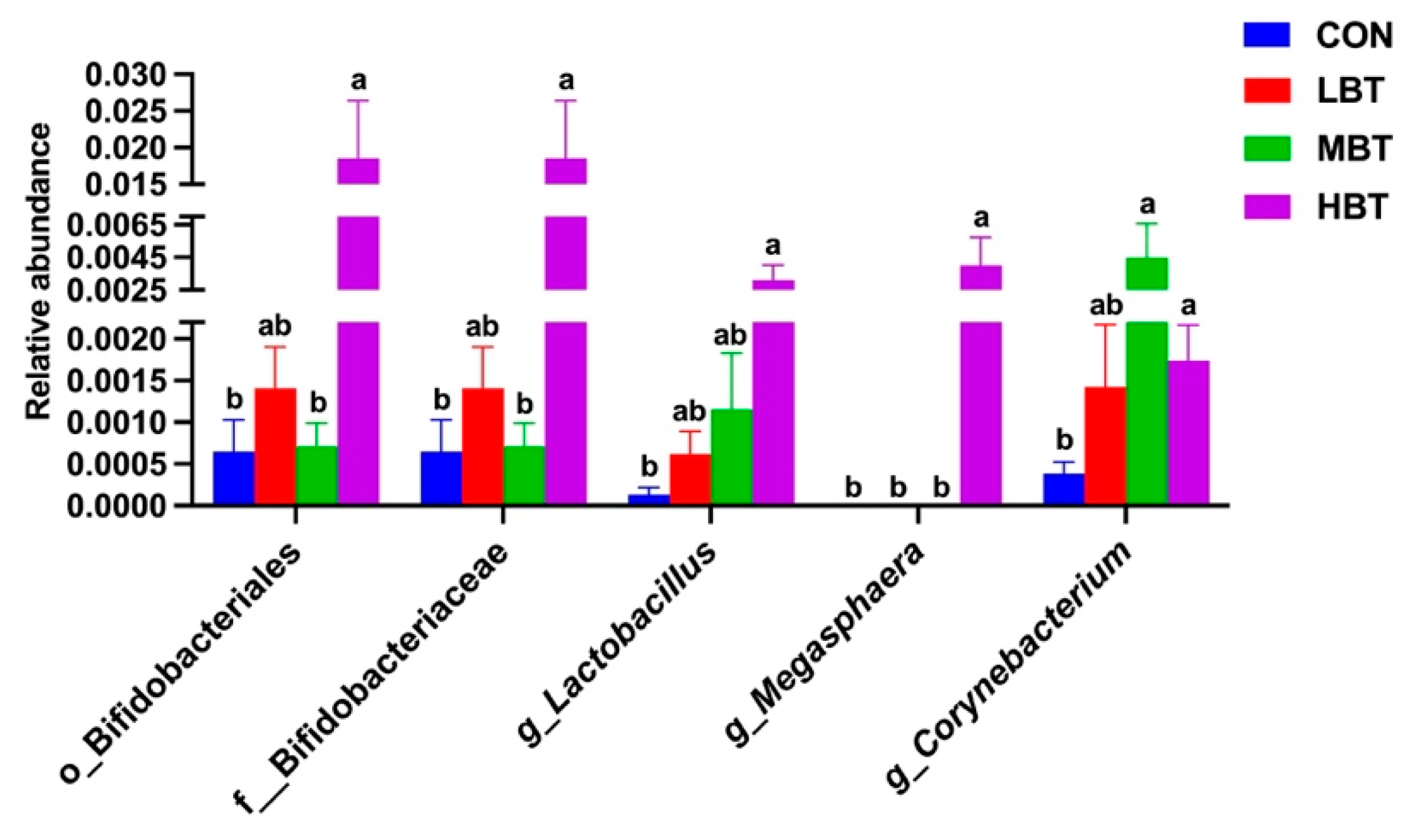

3.6.3. Differences in Abundances of Pulmonary Microbiota

3.6.4. Differences in Abundances of Pulmonary Microbial Predicted Functions

3.6.5. Relationship Between Abundances of Pulmonary Microbiota and Predicted Microbial Functions

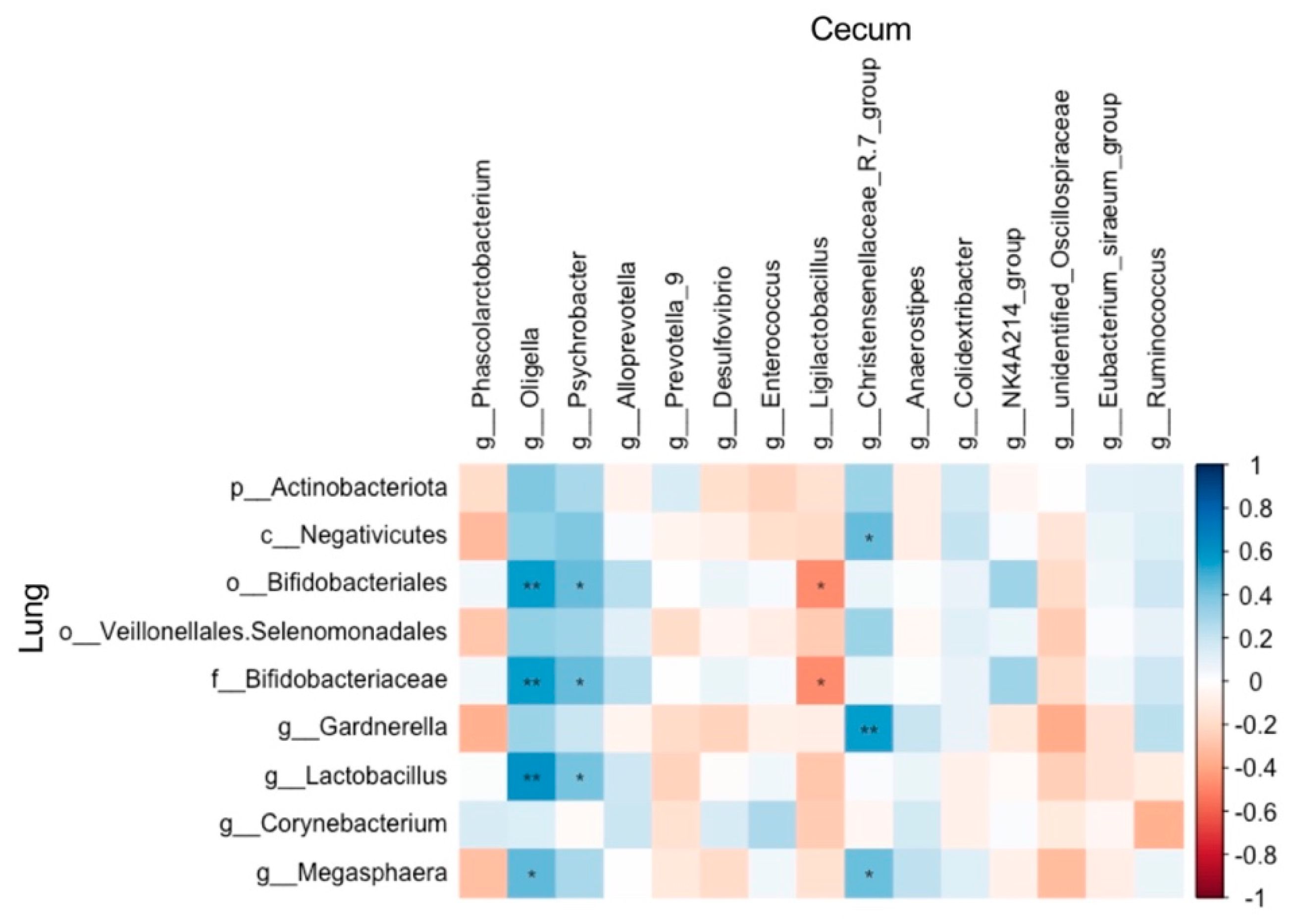

3.7. Relationship Between Abundances of Cecal and Pulmonary Microbiota

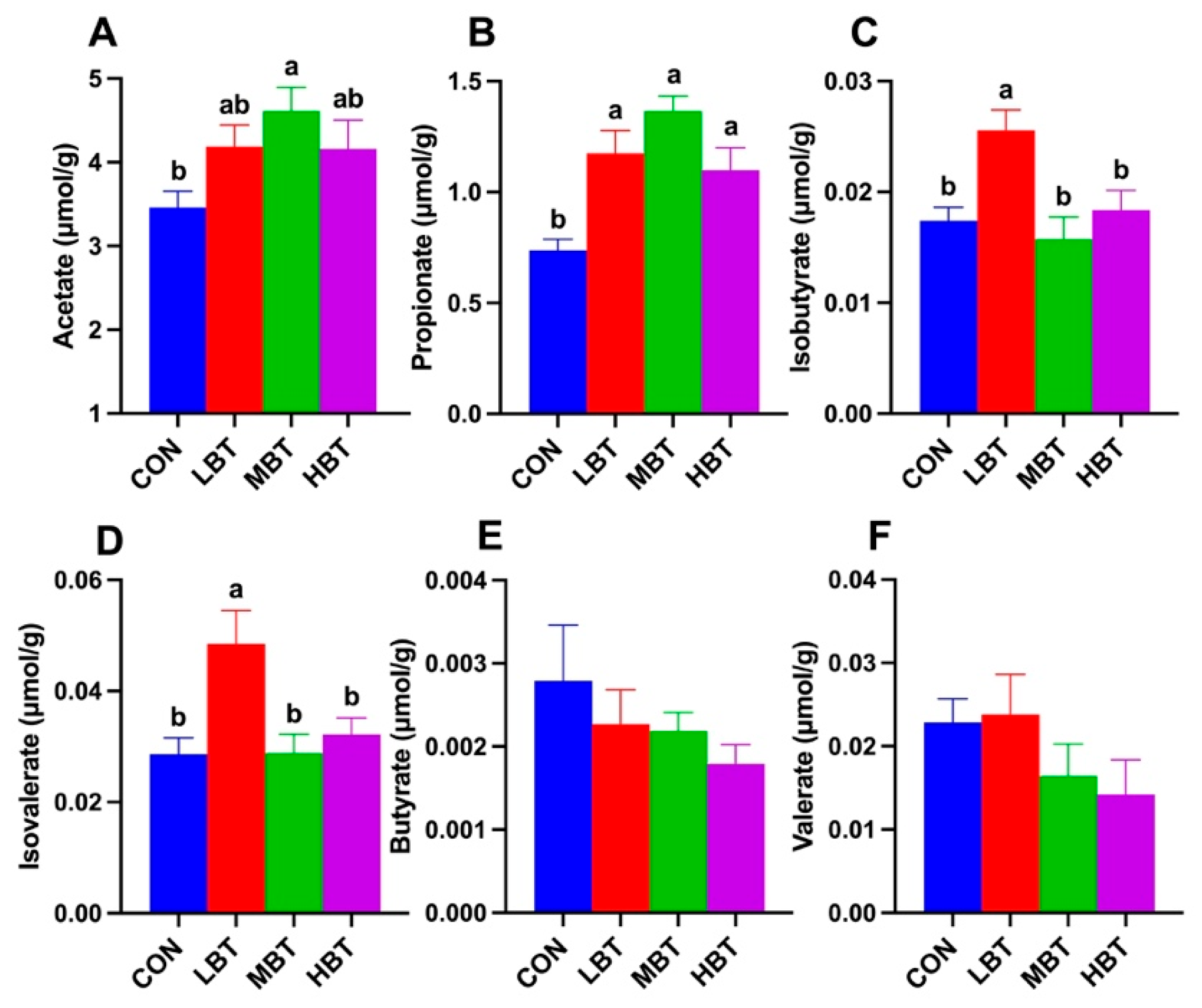

3.8. Effect of BT on Cecal SCFAs

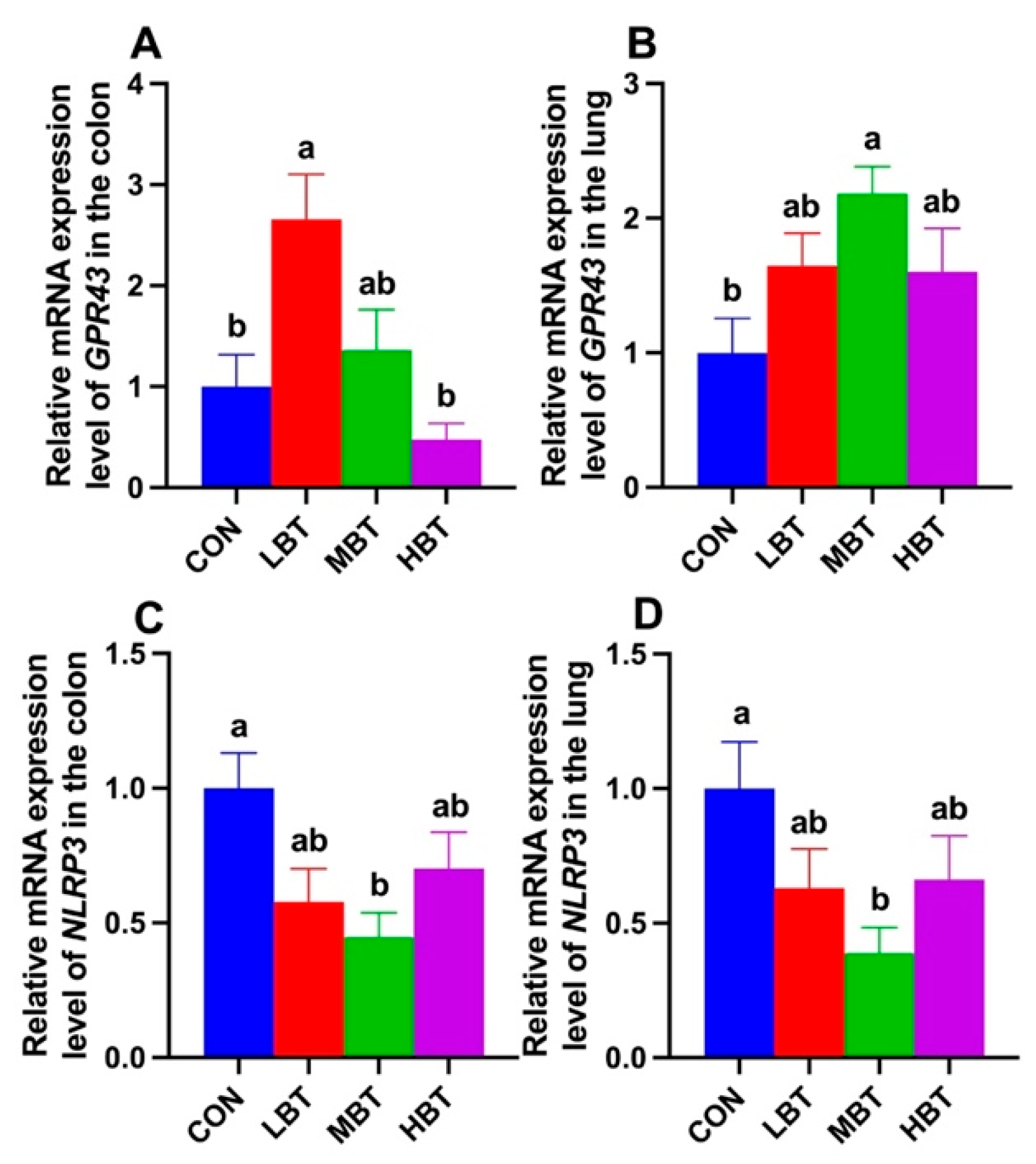

3.9. Expression of SCFAs Receptor and Inflammasome Genes in Colon and Lung

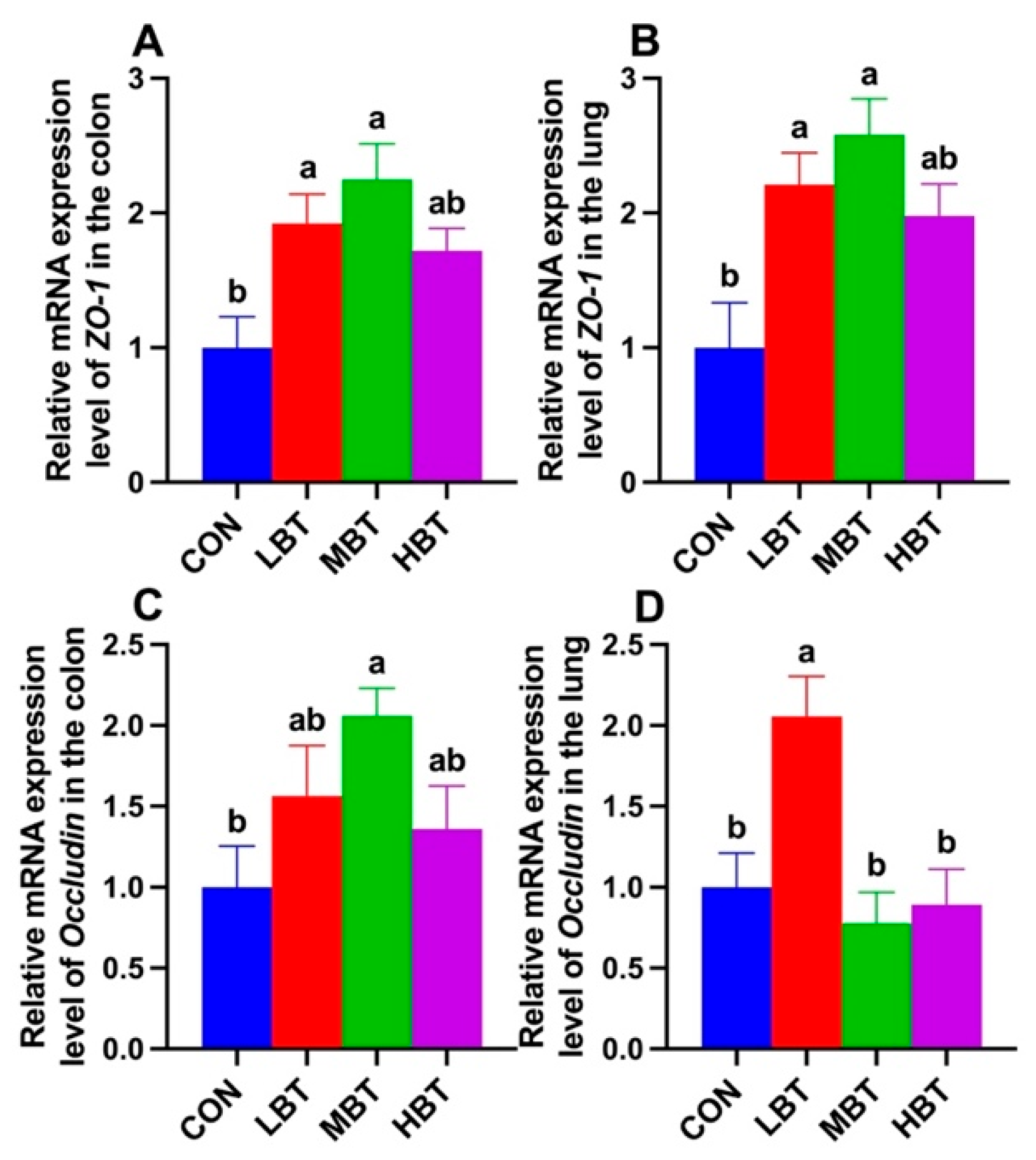

3.10. Effects of BT on Expressions of ZO-1 and Occludin

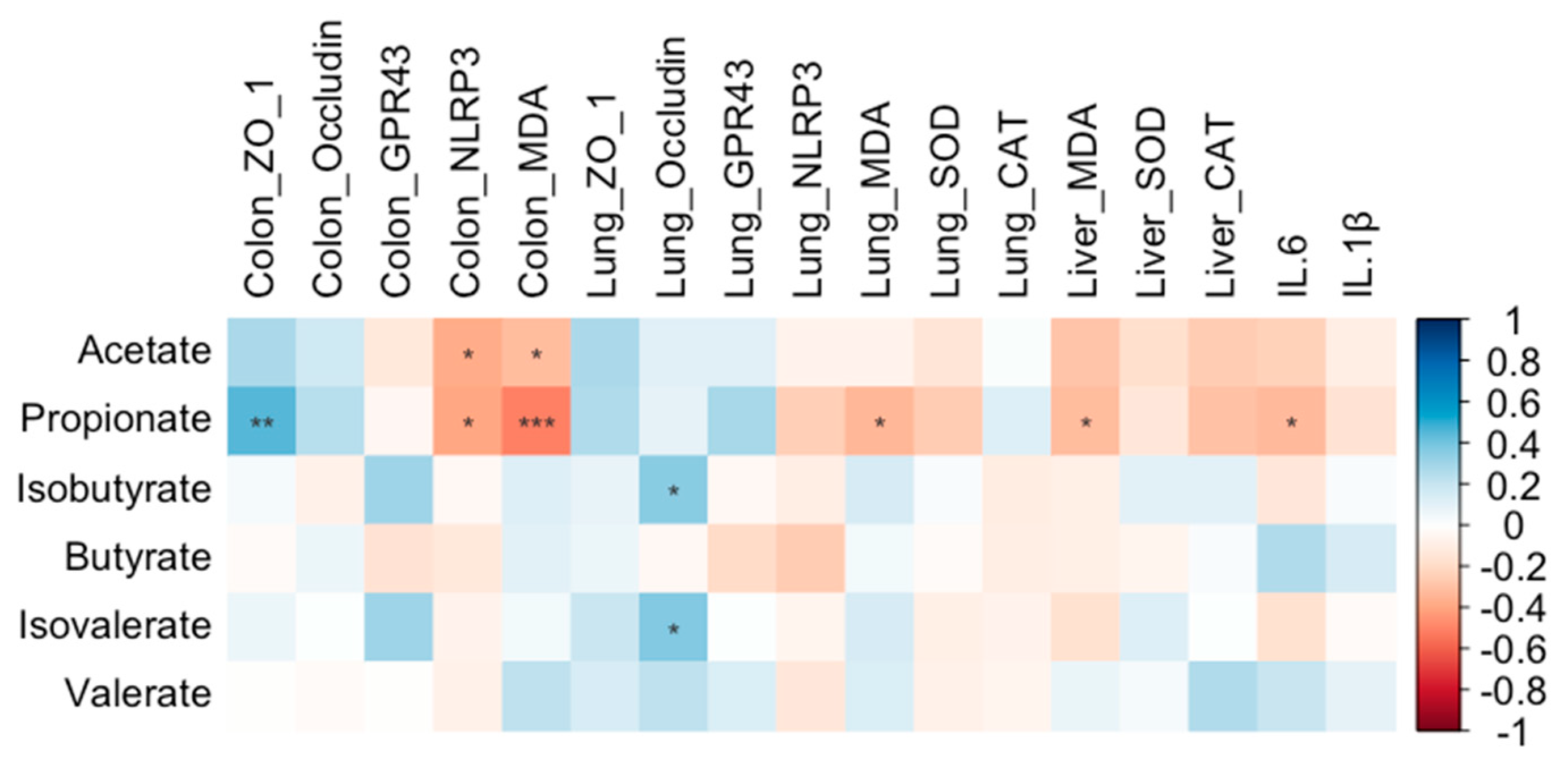

3.11. Relationship Between SCFAs Content, and Genes Expression, Antioxidant and Inflammatory Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability

Ethic Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Bian, C.; Xing, Y.; Xue, H.; Hou, W.; Men, W.; Dou, D.; Kang, T. The burdock database: a multi-omic database for Arctium lappa, a food and medicinal plant. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuki, A.; Tatemichi, M.; Nakazawa, A.; Tsukada, N.; Nagata, H.; Kinoshita, Y. Effects of Burdock tea on recurrence of colonic diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding: An open-labelled randomized clinical trial. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, C.Y. Influence of Roasting Treatment on the Antioxidant Activities and Color of Burdock Root Tea. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 22, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, K.; Ngai, L.; Chiaranunt, P.; Watt, J.; Popple, S.; Forde, B.; Denha, S.; Olyntho, V.M.; Tai, S.L.; Cao, E.Y.; et al. A gut commensal protozoan determines respiratory disease outcomes by shaping pulmonary immunity. Cell 2025, 188, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, J.P.; McCormick, B.A. Aging, Frailty, and the Microbiome—How Dysbiosis Influences Human Aging and Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groschwitz, K.R.; Hogan, S.P. Intestinal barrier function: Molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2009, 124, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, W.T.; Odenwald, M.A.; Turner, J.R.; Zuo, L. Tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 as regulators of epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1514, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisada, M.; Hiranuma, M.; Nakashima, M.; Goda, N.; Tenno, T.; Hiroaki, H. High dose of baicalin or baicalein can reduce tight junction integrity by partly targeting the first PDZ domain of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 887, 173436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.; Wu, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Peng, L. Sodium Butyrate Promotes Reassembly of Tight Junctions in Caco-2 Monolayers Involving Inhibition of MLCK/MLC2 Pathway and Phosphorylation of PKCβ2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J.W.O.; Towarnicki, S.G. Mitochondria, the gut microbiome and ROS. Cell. Signalling 2020, 75, 109737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Wu, W.; Liu, Z.; Cong, Y. Microbiota metabolite short chain fatty acids, GPCR, and inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S.; Mohanty, S.; Sharma, S.; Tripathi, P. Possible role of gut microbes and host’s immune response in gut–lung homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 954339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, H.; Niu, B.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Mi, Y.; Li, P. ACT001 Alleviates chronic kidney injury induced by a high-fat diet in mice through the GPR43/AMPK pathway. Lipids Health Dis. 2023, 22, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimura, K.E.; Sitarik, A.R.; Havstad, S.; Lin, D.L.; Levan, S.; Fadrosh, D.; Panzer, A.R.; LaMere, B.; Rackaityte, E.; Lukacs, N.W.; et al. Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cait, A.; Hughes, M.R.; Antignano, F.; Cait, J.; Dimitriu, P.A.; Maas, K.R.; Reynolds, L.A.; Hacker, L.; Mohr, J.; Finlay, B.B.; et al. Microbiome-driven allergic lung inflammation is ameliorated by short-chain fatty acids. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Ma, S.; Zhao, L.; Ge, P.; Wen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; et al. Mechanisms of Qingyi Decoction in Severe Acute PancreatitisAssociated Acute Lung Injury via Gut Microbiota: Targeting the Short-Chain Fatty Acids-Mediated AMPK/NF-kB/NLRP3 Pathway. Microbiol. Spectrum 2023, 11, e0366422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Lu, L.; Yu, H.; Feng, Q.; Xu, M. Study on Function of Burdock Tea in Reducing Lipemia Auxiliarily. Food and Drug 2012, 14, 399–400. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Jiang, L.Y.; Han, M.; Ye, M.H.; Wang, A.Q.; Wei, W.H.; Yang, S.M. Reproductive responses of male Brandt’s voles (Lasiopodomys brandtii) to 6-methoxybenzoxazolinone (6-MBOA) under short photoperiod. Sci. Nat. 2016, 103, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Luo, Z.; Pang, S.; Wang, C.C.; Ge, L.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, F.; Hong, X.; Zhang, J. The effects of yam gruel on lowering fasted blood glucose in T2DM rats. Open Life Sci. 2020, 15, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Shi, J.; Gu, K.; Wei, W.; Yang, S.; Dai, X. Relationship between food grinding and gut microbiota in Brandt's voles. Can. J. Zool. 2023, 101, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romualdo, G.R.; Silva, E.d.A.; Da Silva, T.C.; Aloia, T.P.A.; Nogueira, M.S.; De Castro, I.A.; Vinken, M.; Barbisan, L.F.; Cogliati, B. Burdock (Arctium lappa L.) root attenuates preneoplastic lesion development in a diet and thioacetamide-induced model of steatohepatitis-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 35, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Kim, J.M.; Jin, Z.; Zhou, J. Prebiotic effectiveness of inulin extracted from edible burdock. Anaerobe 2008, 14, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, N.; Kan, J.; Tang, S.; Sun, R.; Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Jin, C. Polyphenols from Arctium lappa L ameliorate doxorubicin-induced heart failure and improve gut microbiota composition in mice. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-da-Silva, P.; Pestana, M.; Vieira-Coelho, M.A.; Fernandes, M.H.; Albino-Teixeira, A. Assessment of renal dopaminergic system activity in the nitric oxide-deprived hypertensive rat model. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 114, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuga, Y.; Harada, K.; Tsuboi, T. Identification of a regulatory pathway of L-phenylalanine-induced GLP-1 secretion in the enteroendocrine L cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 588, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, J.K.; Kelley, S.P.; Mossine, V.V.; Mawhinney, T.P. Structure, Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Activities of the (4R)- and (4S)-epimers of S-Carboxymethyl-L-cysteine Sulfoxide. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torretta, S.; Scagliola, A.; Ricci, L.; Mainini, F.; Di Marco, S.; Cuccovillo, I.; Kajaste-Rudnitski, A.; Sumpton, D.; Ryan, K.M.; Cardaci, S. D-mannose suppresses macrophage IL-1β production. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala-Jaakkola, R.; Laitila, A.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Lehtoranta, L. Role of D-mannose in urinary tract infections – a narrative review. Nutr. J. 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imre, S.; Tóth, F.; Fachet, J. Superoxide dismutase, catalase and lipid peroxidation in liver of young mice of different ages. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1984, 28, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazelton, G.A.; Lang, C.A. Glutathione peroxidase and reductase activities in the aging mouse. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1985, 29, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nna, V.U.; Ujah, G.A.; Suleiman, J.B.; Mohamed, M.; Nwokocha, C.; Akpan, T.J.; Ekuma, H.C.; Fubara, V.V.; Kekung-Asu, C.B.; Osim, E.E. Tert-butylhydroquinone preserve testicular steroidogenesis and spermatogenesis in cisplatin-intoxicated rats by targeting oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. Toxicology 2020, 441, 152528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Duan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, F. Antioxidant mechanism of tea polyphenols and its impact on health benefits. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 6, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Aguilar, G.A.; Blancas-Benítez, F.J.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G. Polyphenols associated with dietary fibers in plant foods: molecular interactions and bioaccessibility. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 13, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.M.A.; M, T.P.S.C. Burdock (Arctium lappa L) roots as a source of inulin-type fructans and other bioactive compounds: Current knowledge and future perspectives for food and non-food applications. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 109889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, M.; Xiang, L. Pharmacological action and potential targets of chlorogenic acid. Adv. Pharmacol. 2020, 87, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Wei, J.; Gong, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, W.; Liu, S.; Luo, C.; Wang, X. Preventive Effect of Arctium lappa Polysaccharides on Acute Lung Injury through Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.M.; Hinkle, K.J.; McDonald, R.A.; Brown, C.A.; Falkowski, N.R.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Dickson, R.P. Whole lung tissue is the preferred sampling method for amplicon-based characterization of murine lung microbiota. Microbiome 2021, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Din, A.U.; Li, N.; Wang, Q.; Yu, J.Z.; Xu, Z.Y.; Li, C.X.; Zhang, X.M.; Yuan, J.L.; et al. Bacterial association and comparison between lung and intestine in rats. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20191570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Song, Y.; Xu, W.; Chen, J.; Zhou, R.; Yang, M.; Zhu, G.; Luo, X.; Ai, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Pulsatilla chinensis saponins improve SCFAs regulating GPR43-NLRP3 signaling pathway in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 308, 116215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, N.; Kan, J.; Sun, R.; Tang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Jin, C. Anti-inflammatory activity of alkali-soluble polysaccharides from Arctium lappa L. and its effect on gut microbiota of mice with inflammation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Dwyer, D.N.; Ashley, S.L.; Gurczynski, S.J.; Xia, M.; Wilke, C.; Falkowski, N.R.; Norman, K.C.; Arnold, K.B.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Salisbury, M.L.; et al. Lung Microbiota Contribute to Pulmonary Inflammation and Disease Progression in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laiman, V.; Lo, Y.C.; Chen, H.C.; Yuan, T.H.; Hsiao, T.C.; Chen, J.K.; Chang, C.W.; Lin, T.C.; Li, S.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; et al. Effects of antibiotics and metals on lung and intestinal microbiome dysbiosis after sub-chronic lower-level exposure of air pollution in ageing rats. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 246, 114164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.E.; Andrés, S.; Snelling, T.J.; López-Ferreras, L.; Yáñez-Ruíz, D.R.; García-Estrada, C.; López, S. Effect of Sunflower and Marine Oils on Ruminal Microbiota, In vitro Fermentation and Digesta Fatty Acid Profile. Front microbiol 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Ou, Z.; Peng, Y. Phascolarctobacterium faecium abundant colonization in human gastrointestinal tract. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 3122–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Su, H.; Lv, Y.; Tao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ni, Z.; Peng, L.; Chen, X. Inulin intervention attenuates hepatic steatosis in rats via modulating gut microbiota and maintaining intestinal barrier function. Food Res. Int. 2023, 163, 112309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amat, S.; Lantz, H.; Munyaka, P.M.; Willing, B.P. Prevotella in Pigs: The Positive and Negative Associations with Production and Health. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, K.; Gottschalk, G. Methanogenesis from Choline by a Coculture of Desulfovibrio sp. and Methanosarcina barkeri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 45, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Li, L.; Yin, Q.; Wu, G. Solids Retention Times Shift Methanogenic Ethanol Oxidation: Novel Insights into Metabolic Pathways, Microbial Community Dynamics, and Energy Metabolisms. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 15861–15874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boopathy, R. Methanogenesis from furfural by defined mixed cultures. Curr. Microbiol. 2002, 44, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Sheng, L.; Zhong, J.; Tao, X.; Zhu, W.; Ma, J.; Yan, J.; Zhao, A.; Zheng, X.; Wu, G.; et al. Desulfovibrio vulgaris, a potent acetic acid-producing bacterium, attenuates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Xue, Y.; Sun, R.; Sun, X.; Sun, Z.; Liu, S.; Tan, Z.; Zhu, W.; Cheng, Y. Nutrient availability of roughages in isocaloric and isonitrogenous diets alters the bacterial networks in the whole gastrointestinal tract of Hu sheep. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crost, E.H.; Coletto, E.; Bell, A.; Juge, N. Ruminococcus gnavus: friend or foe for human health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramoto, Y.; Akagawa, S.; Hori, S.I.; Tsuji, S.; Higasa, K.; Kaneko, K. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota as a susceptibility factor for Kawasaki disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1268453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancabelli, L.; Milani, C.; Lugli, G.A.; Turroni, F.; Cocconi, D.; van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. Identification of universal gut microbial biomarkers of common human intestinal diseases by meta-analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Liu, F.; Qiu, B.; Li, Y.; Xie, X.; Guo, J.; Wu, L.; Liang, T.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; et al. Analysis of Gut Microbiota Signature and Microbe-Disease Progression Associations in Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated With Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 892401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdó, T.; Ruiz, A.; Jáuregui, R.; Azaryah, H.; Torres-Espínola, F.J.; García-Valdés, L.; Teresa Segura, M.; Suárez, A.; Campoy, C. Maternal obesity is associated with gut microbial metabolic potential in offspring during infancy. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 74, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Li, Y.; Zheng, J.; Liu, N.; Zhang, J.; Tan, H. Important role of a LAL regulator StaR in the staurosporine biosynthesis and high-production of Streptomyces fradiae CGMCC 4.576. Sci. China:Life Sci. 2019, 62, 1638–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laparra, J.M.; Sanz, Y. Interactions of gut microbiota with functional food components and nutraceuticals. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 61, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbury, P.E.; Kalt, W. Xenobiotic metabolism and berry flavonoid transport across the blood-brain barrier. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3950–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdock, G.A.; Cowley, A.B.; Li, Q.S. Repeat-dose animal toxicity studies and genotoxicity study with deactivated alkaline serine protease (DASP), a protein low in phenylalanine (PHE). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharkina, T.; Heinzel, E.; Koczulla, R.A.; Greulich, T.; Rentz, K.; Pauling, J.K.; Baumbach, J.; Herrmann, M.; Grünewald, C.; Dienemann, H.; et al. Analysis of the airway microbiota of healthy individuals and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by T-RFLP and clone sequencing. PLoS One 2013, 8, e68302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, S.A.; Marathe, N.P.; Lanjekar, V.; Ranade, D.; Shouche, Y.S. Comparative genome analysis of Megasphaera sp. reveals niche specialization and its potential role in the human gut. PLoS One 2013, 8, e79353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Maschera, B.; Lea, S.; Kolsum, U.; Michalovich, D.; Van Horn, S.; Traini, C.; Brown, J.R.; Hessel, E.M.; Singh, D. Airway host-microbiome interactions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boeck, I.; Wittouck, S.; Martens, K.; Spacova, I.; Cauwenberghs, E.; Allonsius, C.N.; Jörissen, J.; Wuyts, S.; Van Beeck, W.; Dillen, J.; et al. The nasal mutualist Dolosigranulum pigrum AMBR11 supports homeostasis via multiple mechanisms. iScience 2021, 24, 102978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomar, L.; Brugger, S.D.; Yost, B.H.; Davies, S.S.; Lemon, K.P. Corynebacterium accolens Releases Antipneumococcal Free Fatty Acids from Human Nostril and Skin Surface Triacylglycerols. mBio 2016, 7, e01725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamash, D.F.; Mongodin, E.F.; White, J.R.; Voskertchian, A.; Hittle, L.; Colantuoni, E.; Milstone, A.M. The Association Between the Developing Nasal Microbiota of Hospitalized Neonates and Staphylococcus aureus Colonization. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, ofz062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, E.; Corr, S.C. Lactobacillus spp. for Gastrointestinal Health: Current and Future Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 840245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Mazel-Sanchez, B.; Kandasamy, M.; Manicassamy, B.; Schmolke, M. Influenza A virus infection impacts systemic microbiota dynamics and causes quantitative enteric dysbiosis. Microbiome 2018, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Raichon, L.; Colom, A.; Monard, S.C.; Namouchi, A.; Cescato, M.; Garnier, H.; Leon-Icaza, S.A.; Métais, A.; Dumas, A.; Corral, D.; et al. A Pulmonary Lactobacillus murinus Strain Induces Th17 and RORγt(+) Regulatory T Cells and Reduces Lung Inflammation in Tuberculosis. Journal of Immunology 2021, 207, 1857–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Kan, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Tang, S.; Sun, R.; Liu, J.; Qian, C.; Jin, C. In vivo and in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of water-soluble polysaccharide from Arctium lappa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 135, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhou, J.; Chai, Y.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Dong, Y.; Mei, X.; Jiang, Y.; Lei, H. A metagenomic study of the gut microbiome in PTB'S disease. Microbes and infection 2022, 24, 104893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, O.M.; Eraky, I.; El-Far, M.A.; Osman, H.G.; Ghoneim, M.A. Rapid diagnosis of genitourinary tuberculosis by polymerase chain reaction and non-radioactive DNA hybridization. J. Urol. 2000, 164, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrini, V.; Gennaro, M.L. Foam Cells: One Size Doesn't Fit All. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, R.; Afaghi, A.; Babakhani, S.; Sohrabi, M.R.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Babolhavaeji, K.; Khani Ali Akbari, S.; Yousefimashouf, R.; Karampoor, S. Role of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids in cancer development and prevention. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachmias, N.; Langier, S.; Brzezinski, R.Y.; Siterman, M.; Stark, M.; Etkin, S.; Avriel, A.; Schwarz, Y.; Shenhar-Tsarfaty, S.; Bar-Shai, A. NLRP3 inflammasome activity is upregulated in an in-vitro model of COPD exacerbation. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0214622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Li, Y.; Bian, Q.; Xuan, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Feng, S.; Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, S. The Bufei Jianpi Formula Improves Mucosal Immune Function by Remodeling Gut Microbiota Through the SCFAs/GPR43/NLRP3 Pathway in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Rats. Int. J. Chronic Obstruct. Pulm. Dis. 2022, 17, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Bansal, Y.; Kumar, R.; Bansal, G. A panoramic review of IL-6: Structure, pathophysiological roles and inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, M.M.; Abuharfeil, N.M.; Darmani, H. The role of IL-1β during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, e2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perler, B.K.; Friedman, E.S.; Wu, G.D. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in the Relationship Between Diet and Human Health. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2023, 85, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastyk, H.C.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Perelman, D.; Dahan, D.; Merrill, B.D.; Yu, F.B.; Topf, M.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Van Treuren, W.; Han, S.; et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell 2021, 184, 4137–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celebi Sözener, Z.; Cevhertas, L.; Nadeau, K.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. Environmental factors in epithelial barrier dysfunction. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.S.; Narayanan, S.P.; Somanath, P.R. Cell-cell junctions: structure and regulation in physiology and pathology. Tissue Barriers 2021, 9, 1848212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuoka, A.; Yoshimoto, T. Barrier dysfunction in the nasal allergy. Allergology International 2018, 67, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pat, Y.; Ogulur, I.; Yazici, D.; Mitamura, Y.; Cevhertas, L.; Küçükkase, O.C.; Mesisser, S.S.; Akdis, M.; Nadeau, K.; Akdis, C.A. Effect of altered human exposome on the skin and mucosal epithelial barrier integrity. Tissue Barriers 2023, 11, 2133877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, T.; Bègue, H.; Basmaciyan, L.; Dalle, F.; Bon, F. Tight Junctions as a Key for Pathogens Invasion in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, F.; da Silva, R.I.K.; Vargas-Stampe, T.L.Z.; Cerqueira, A.M.F.; Andrade, J.R.C. Cell invasion and survival of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli within cultured human intestinal epithelial cells. Microbiology 2013, 159, 1683–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyer, M.; Loiselet, A.; Bon, F.; L'Ollivier, C.; Laue, M.; Holland, G.; Bonnin, A.; Dalle, F. Intestinal Cell Tight Junctions Limit Invasion of Candida albicans through Active Penetration and Endocytosis in the Early Stages of the Interaction of the Fungus with the Intestinal Barrier. PLOS One 2016, 11, e0149159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Ding, X.; Li, X.; Jing, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, G.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, C.; et al. Inulin supplementation ameliorates hyperuricemia and modulates gut microbiota in Uox-knockout mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2217–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Liu, C.; Liu, F.; Song, Y.L.; Li, Q.Y.; Yu, L.; Lv, Y. Liver cold preservation induce lung surfactant changes and acute lung injury in rat liver transplantation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Index of alpha diversity | Control | Low-dose BT | Middle-dose BT | High-dose BT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed features | 309 ± 31a | 390 ± 60a | 208 ± 11b | 281 ± 43ab |

| Chao1 | 309.83 ± 31.53a | 390.89 ± 59.48a | 209.54 ± 11.63b | 282.06 ± 43.11ab |

| Shannon | 5.53 ± 0.30a | 6.03 ± 0.36a | 4.53 ± 0.26b | 5.07 ± 0.36ab |

| Simpson | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 0.91 ± 0.02 |

| Pielou | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.63 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).