1. Introduction

Proliferation of plastic waste is a growing concern over the environmental and health impacts of plastic-derived micro- and nanoparticles [

1,

2]. Plastic particles smaller than 1 µm, known as nanoplastics (NPs), constitute a concerning class of pollutants due to their small size, environmental persistence, and potential for bioaccumulation [

3]. Among those are polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs), which are frequently used in consumer products and are prevalent in air, water, and soil [

4]. Their ubiquity and persistence raise significant concerns regarding their impact on human health, especially through inhalation, ingestion, or dermal exposure [

5,

6]. Once inside the body, these particles may cross biological barriers, accumulate in tissues, and interact with various cell types, potentially inducing toxic or immunomodulatory effects [

7].

Macrophages are professional phagocytic immune cells that play a central role in innate immunity by engulfing and destroying pathogens, clearing cellular debris, and orchestrating inflammatory responses [

8,

9,

10]. Given their role in surveillance and immune regulation, macrophages are among the first cell types to interact with foreign particles, including NPs [

11]. Internalization of NPs by macrophages can interfere with normal cellular functions through physical interactions, inducing oxidative stress, altering signaling pathways, modulating gene expression, metabolism, and inflammation [

12,

13,

14]. Therefore, better understanding how macrophages respond to PS-NPs is essential for assessing the potential health risks associated with exposure to these particles [

15,

16].

Despite increasing recognition of NPs as environmental and health hazards, their specific interactions with immune cells, particularly their intracellular localization and their effects on anti-microbial and inflammatory responses, remain poorly understood. Prior studies have suggested that NPs can localize within cellular compartments, such as lysosomes, endosomes, and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), potentially disrupting key cellular functions [

17,

18]. However, the extent and implications of such intracellular trafficking in macrophages are still being elucidated. Moreover, while oxidative stress has been proposed as a mechanism of NP-induced toxicity [

19], its direct relationship with immune cell function, including microbicidal activity remains poorly understood.

The present study aimed at examining the functional impact of PS-NPs on macrophages. Our findings indicate that PS-NPs localize in various intracellular compartments and that they increase macrophage bactericidal activity through a mechanism involving the generation of reactive oxigen species (ROS) and of the mitochondrial metabolite itaconate. These results deepen our understanding of NPs-immune cells interactions by providing novel insights on the impact of NPs on immune and metabolic processes in macrophages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institut national de la recherche scientifique.

2.2. Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-P115, rabbit anti-calnexin, and mouse anti-Rab7 (Invitrogen–Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and rat anti-LAMP-1 monoclonal antibody (clone 1D4B), developed by J. T. August and obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA), supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence were as follows: Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, and Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated anti-rat IgG (Invitrogen–Molecular Probes).

2.3. Macrophage Culture

The LM-1 immortalized bone marrow-derived macrophage cell line (iBMMs) [

20] was maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; high glucose, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), and 2 mM L-glutamine. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO

2. For routine passaging, cells were washed with sterile Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and detached using a cell scraper or by gentle pipetting, as iBMMs are adherent but do not strongly attach. Cells were seeded at appropriate densities depending on the experimental design. Medium was refreshed every 2–3 days, and cells were passaged when they reached approximately 70–80% confluency. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were generated as previously described [

21]. Wild-type (WT) and

Acod1 knockout (

Acod1-/-) C57BL/6 male and female mice aged 8 to 12 weeks (JAX) were euthanized in accordance with institutional animal care and use guidelines. Femurs and tibias were collected under sterile conditions, and bone marrow was flushed using HBSS (Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution) through a 26½ G needle attached to a 10 mL syringe. The extracted marrow was passed through a 70 µm cell strainer and centrifuged at 2000 RPM for 5–6 min at 4 °C. Red blood cells were lysed using ammonium chloride (NH

4Cl) lysis buffer, followed by a wash in HBSS and a second centrifugation. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in complete Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone), 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 15% (v/v) L929 cell-conditioned medium (as a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor, M-CSF). Cells were plated in non-adherent Petri dishes and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO

2. Medium was supplemented with fresh L929-conditioned medium on days 3, 5, and 7 to promote macrophage differentiation. On day 8, BMMs were harvested by gentle scraping in cold HBSS containing HEPES and antibiotics, followed by centrifugation. To render the BMMs quiescent, cells were cultured for an additional 24 h in complete DMEM lacking L929-conditioned medium prior to downstream experiments.

2.4. Characterization of PS-NPs

Commercial 100 nm fluorescent polystyrene nanoparticles (PS-NPs) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. These nanoparticles were supplied as aqueous suspensions at a concentration of 1% solids by weight in deionized water, containing trace amounts of surfactant and preservative to prevent aggregation and maintain colloidal stability. The PS-NPs had a density of 1.06 g/cm3 and a refractive index of 1.59. The particles were internally dyed with fluorescent dye.

2.5. Treatment of Cells with PS-NPs

Cells were seeded in either 96-well plates (200 μL/well), 24-well plates (500 μL/well), or 6-well plates (2 mL/well) using complete DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The following day, cells were treated with various stimuli depending on the experimental conditions, including PS-NPs. All treatments were carried out in fresh medium, and cells were incubated for the indicated time points prior to downstream analyses.

2.6. MTT Assay for Cell Viability

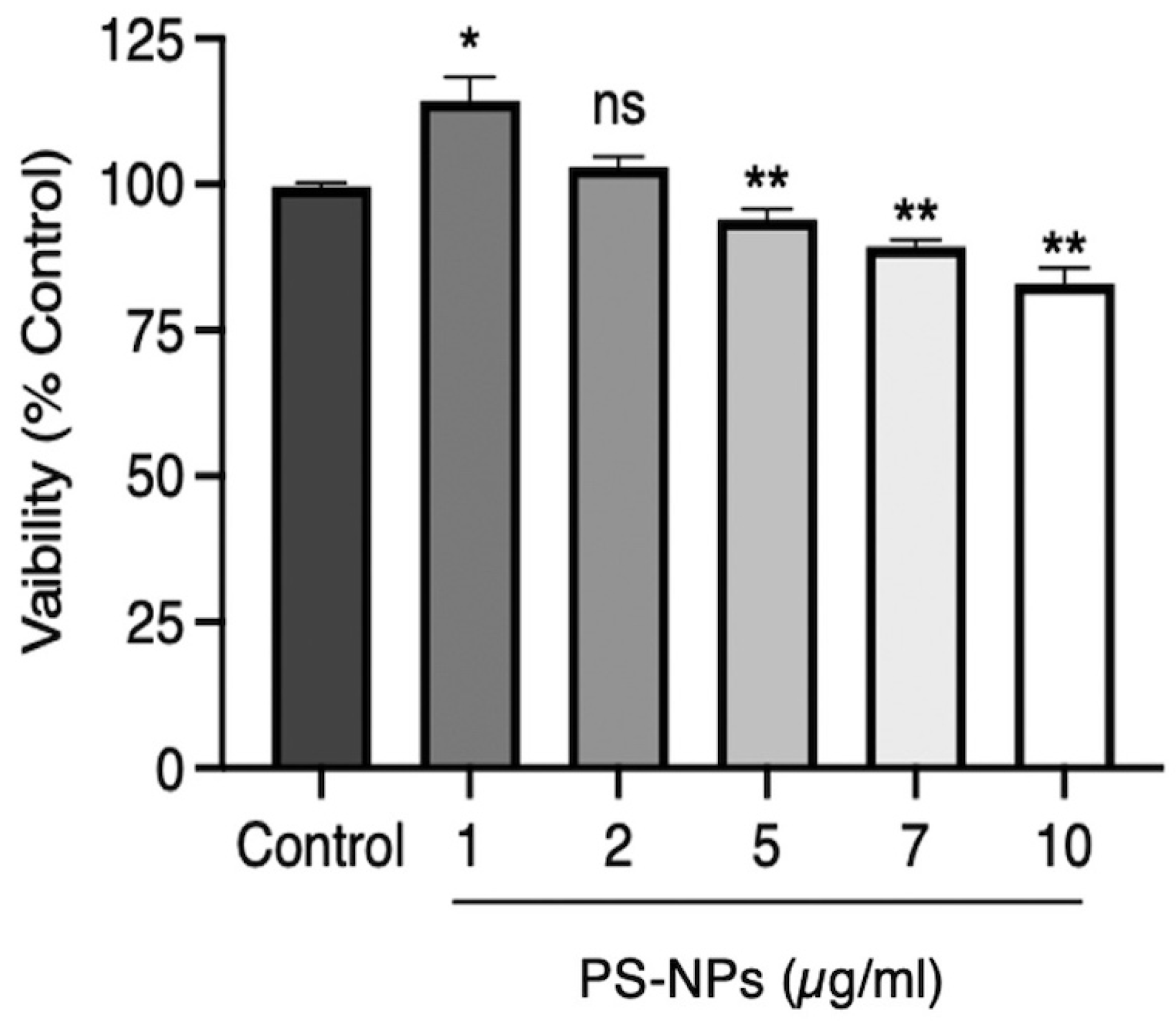

Viability of iBMMs exposed to PS-NPs was ascertained using the MTT assay [

22]. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a concentration of

1.5×104 cells and left for overnight incubation to allow the cells to adhere. The cells were then treated for 24 h with various concentrations of PS-NPs (0, 1, 2, 7, 5, and 10 μg/mL) to assess cytotoxicity. After the exposure period, cell viability was determined by the MTT assay (Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide). An MTT solution was prepared to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL in cell culture medium and pipetted into wells. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h so that viable cells could convert MTT to purple formazan crystals. Following incubation, the MTT-containing medium was slowly aspirated and 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added in each well for the dissolution of formazan crystals and plates were read at 570 nm on a microplate reader. Cell viability was calculated by comparing treated cells’ absorbance values with the control untreated group.

2.7. Confocal Microscopy

iBMMs were seeded in 24-well plates containing sterile microscope coverslips and treated with PS-NPs as described above. After treatment, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min at room temperature, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Following permeabilization, samples were blocked in 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h. Cells were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the following primary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA/PBS: rat LAMP1 (1:500), mouse Rab7 (1:600), rabbit P115 (1:500), and rabbit Calnexin (1:500). After washing, cells were incubated for 1 hour with the appropriate secondary antibodies at 1:500 dilution: anti-rat Alexa Fluor 647, anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488, and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647. Coverslips were washed three times with PBS after each step and mounted individually onto glass slides using Fluoromount-G (Invitrogen). Imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope equipped with a Plan-Apochromat X 63 oil-immersion objective (NA 1.4) in differential interference contrast (DIC) mode. Images were acquired in sequential scanning mode and processed using ZEN 2012 software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging). For each condition, a minimum of 25 cells were analyzed using ZEN 2012 or Icy image analysis software.

2.8. Bactericidal Assay

iBMM and BMM derived from WT and

Acod1-/- mice treated with PS-NPs were infected with non-opsonized

Escherichia coli DH1 (OD600=0.6) at a ratio of 20:1. Bacteria were added in 20

μl of PBS, and plates were centrifuged at 1000 g for 1 min. Plates were next incubated at 37°C for 20 min prior to four washes with 1 ml PBS. Complete DMEM with 5 mg/ml of gentamicin (Life Technologies) was then added for 20 min (zero time point) or for an additional 4 h [

23]. Bactericidal activity was assessed by counting colonies in agar plates, and results were expressed as the log

10 of colony forming units per ml (CFU/ml).

2.9. ROS Measurement

iBMM were incubated in the presence of 5 μM CellROX Deep Green Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 5 μM MitoSOX™ Mitochondrial Superoxide Indicators Red. Subsequently, after two washes with PBS, cells were collected by scraping in HBSS, fixed for 10 min in 4% PFA and washed twice with PBS. Samples were acquired in the APC channel on a LSRFortessa SORP cytometer with the BD FACSDiva6.2 software (BD Biosciences) [

24].

2.10. Nitric Oxide Production

Nitric oxide production was quantified by measuring nitrite, a stable NO metabolite, using the Griess reagent assay [

25]. Briefly, 100 μL of cell culture supernatants were mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide and 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride) in a 96-well plate and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Absorbance was read at 570 nm using a microplate reader. A standard curve was generated using sodium nitrite (NaNO

2) to calculate nitrite concentration.

2.11. Gene Expression Analysis by RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from iBMMs subjected to various experimental conditions, including untreated control, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation, exposure to PS-NPs, bacterial infection, and co-treatment with PS-NPs and bacteria, at 8 h and 18 h post-treatments. RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with acceptable A260/A280 ratios ranging between 1.8 and 2.0. RNA integrity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis in selected samples. First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 500 ng of total RNA using the iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) following the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR was conducted using the iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on either the Stratagene Mx3000P or QuantStudio™ 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression levels of Acod1 were quantified using gene-specific primers, with Rps29 used as the housekeeping gene for normalization. Relative expression was calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method, comparing treated samples to control conditions after normalization to the housekeeping gene. The following primers were used: Acod1-F: 5′-GCAACATGATGCTCAAGTCTG-3′; Acod1-R: 5′-TGCTCCTCCGAATGATACCA-3′; Rps29-F: 5′-CACCCAGCAGACAGACAAACTG-3′; Rps29-R: 5′-GCACTCATCGTAGCGTTCCA-3′.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All data resulted from the average of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 software, and the statistical analysis was performed using the two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance was defined as a *p ≤0.05, **p ≤0.01, ***p ≤0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Intracellular Localization of PS-NPs in iBMM

To study the intracellular localization of fluorescent PS-NPs and their impact on macrophage function, we first exposed iBMMs to PS-NPs at various concentrations for 24 h to assess their toxicity. As illustrated in

Figure 1, PS-NPs were slightly cytotoxic at concentrations above 2 µg/mL.

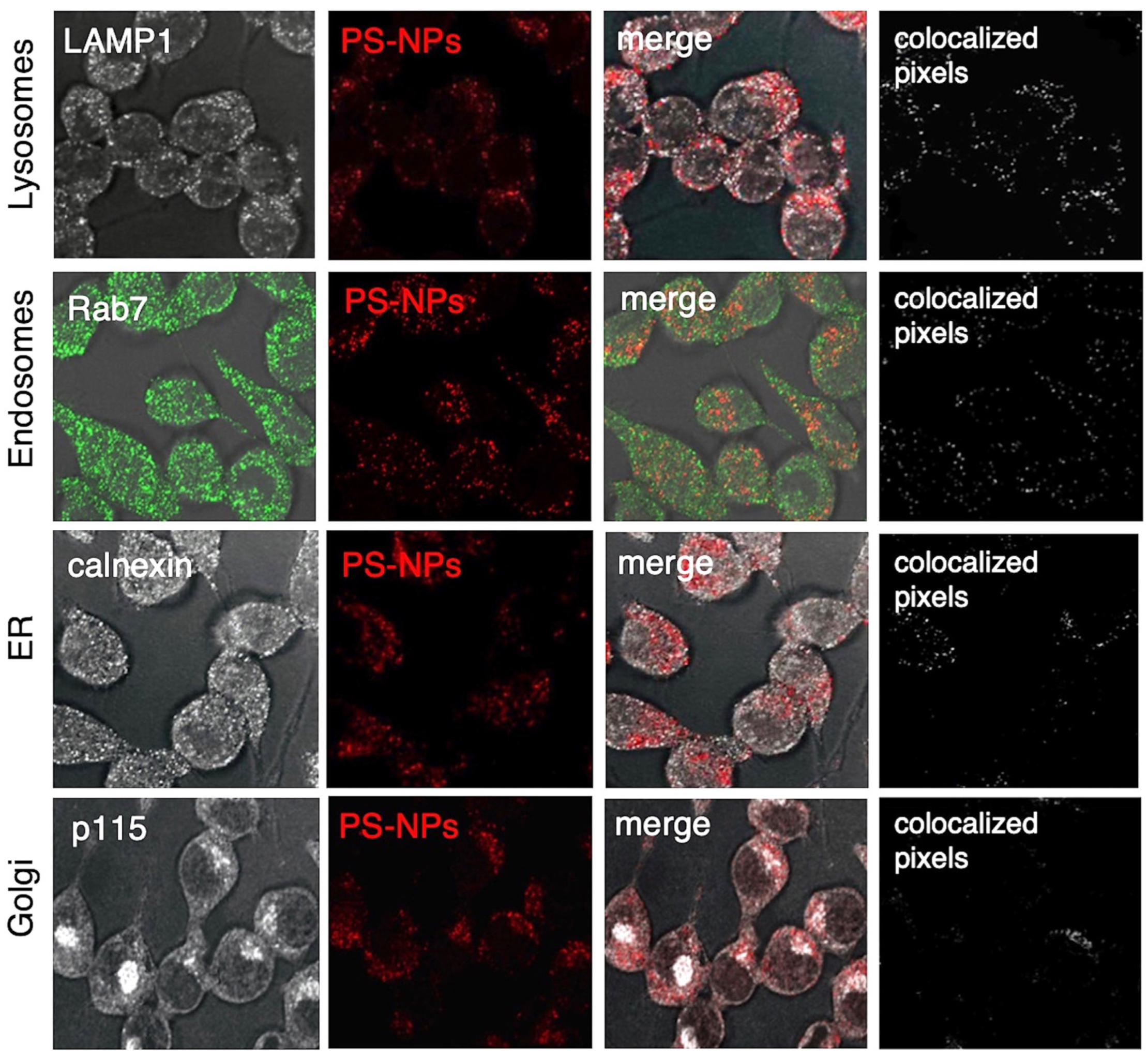

We therefore decided to use 1 µg/mL of PS-NPs for our experiments, a concentration that did not affect iBMM viability. To assess the intracellular localization of PS-NPs 24 h post-internalization, we used confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. As shown in

Figure 2, fluorescent PS-NPs colocalized with the lysosomal protein LAMP1 (

Figure 2A), the endosomal protein Rab7 (

Figure 2B), as well as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein calnexin (

Figure 2C). On the other hand, we did not observe significant colocalization of PS-NPs with the Golgi protein p115 (

Figure 2D). These results indicate that PS-NPs are internalized by macrophages, with accumulation predominantly in lysosomes and endosomes, and to a lesser extent in the ER. These findings underscore the endo-lysosomal pathway as a route for intracellular PS-NPs trafficking.

3.2. PS-NPs Increase the Bactericidal Activity of Macrophages

Given the importance of the endo-lysosomal compartments in the killing of internalized bacteria [

26,

27], we tested the hypothesis that accumulation of PS-NPs in those compartments may alter the bactericidal capacity of macrophages. To this end, iBMM incubated in the presence or absence of 1 µg/mL PS-NPs for 18 h were fed with

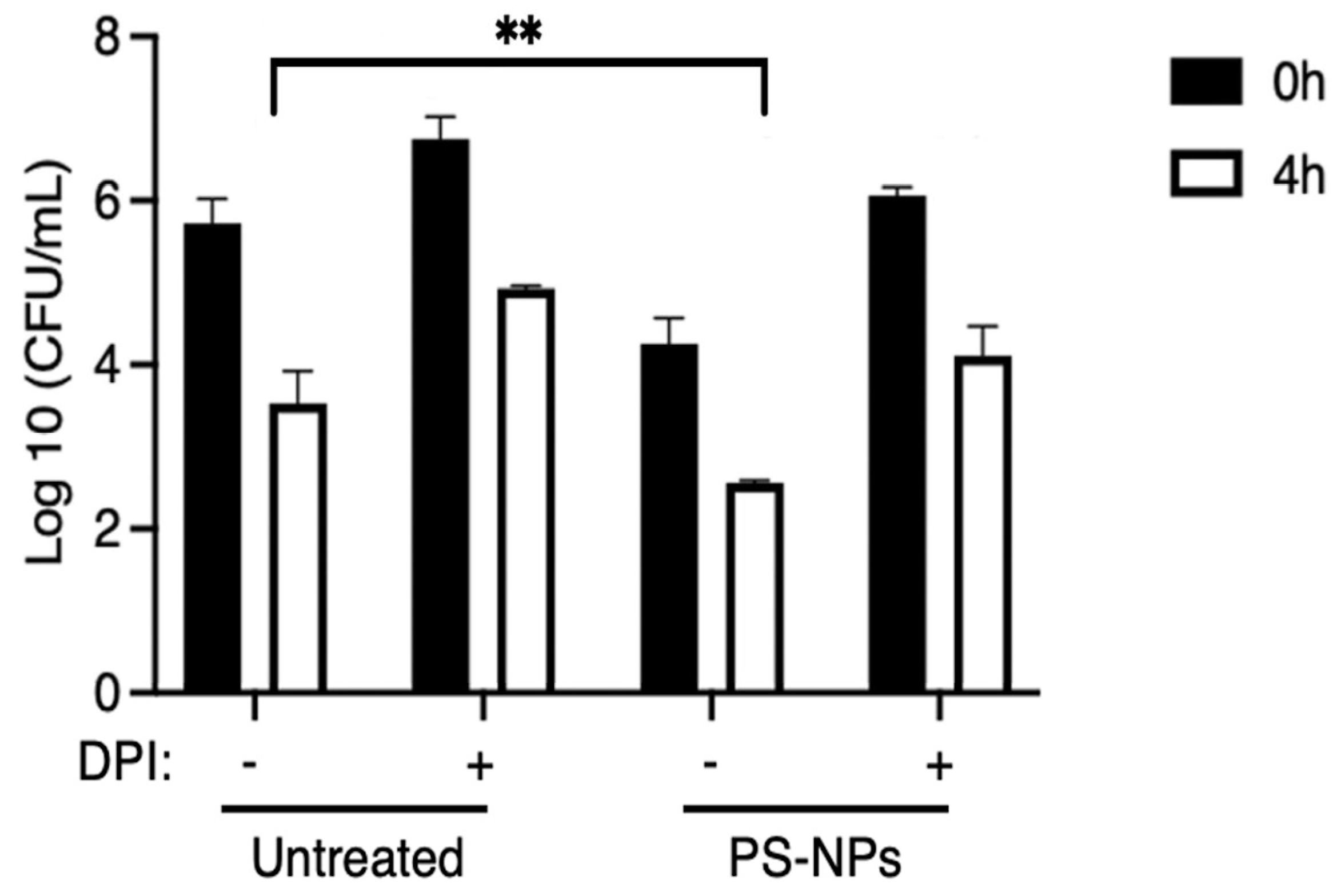

E. coli. Since reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a major role in bacterial killing [

28], we determined their contribution using diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), a potent inhibitor of the NADPH oxidase [

29]. After infection, cells were lysed and diluted lysates were plated in agar plates. Results shown in

Figure 3 indicate that exposure to PS-NP significantly increased the ability of macrophages to kill

E. coli. Furthermore, pre-treatment of iBMM with DPI markedly attenuated bacterial clearance, suggesting that the enhanced bactericidal activity induced by PS-NPs is, at least in part, dependent on NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS production.

The fact that bacterial clearance was not fully inhibited by DPI indicates that other components of the macrophage microbicidal machinery contribute to

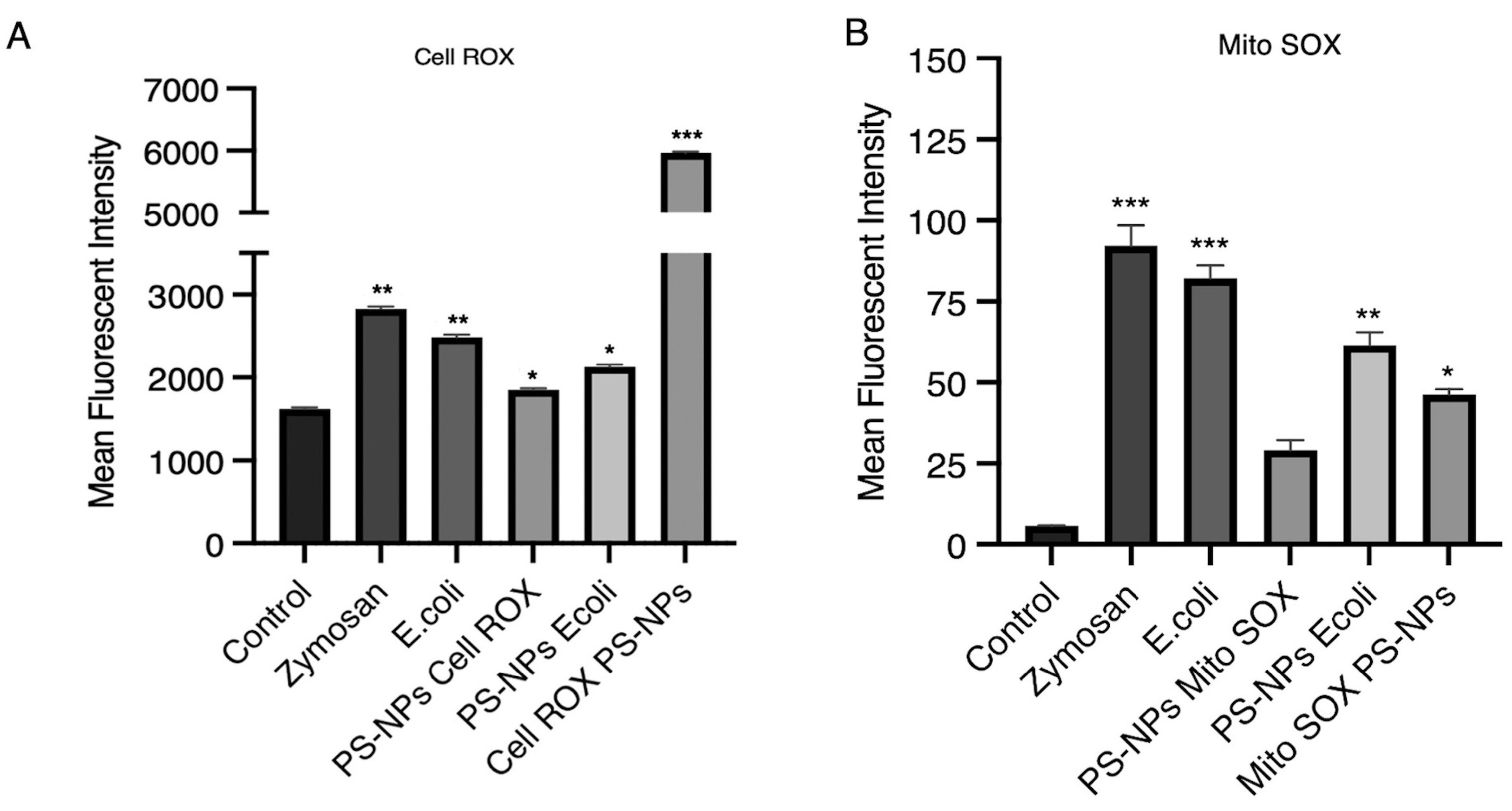

E. coli killing, regardless of the presence of PS-NPs. To determine the extent of ROS produced by untreated and PS-NPs-treated iBMM, we next quantified ROS produced by control and PS-NPs-treated iBMM exposed to

E. coli. To this end, we measured by flow cytometry total cell ROS using CellROX and mitochondrial ROS using MitoROS. As expected, iBMM exposed to zymosan or

E. coli produced high levels of total cellular ROS, whereas iBMM exposed to PS-NPs for 18 h produced slightly higher levels of cellular ROS than control iBMM (

Figure 4A). Of note, initial exposure of iBMM to PS-NPs induced high levels of total cellular ROS, which declined over 24 h. In contrast, iBMM incubated for 18 h with PS-NPs produced less cellular ROS than untreated iBMM upon exposure to

E. coli. In the case of mitochondrial ROS, we observed that PS-NPs alone induced lower levels with respect to zymosan and

E. coli and that iBMM exposed for 18 h to PS-NPs produced less mitochondrial ROS that untreated iBMM in response to

E. coli (

Figure 4B). Hence, although ROS contribute to the enhanced bacterial killing observed in iBMM pretreated with PS-NPs, our results suggest that ROS-independent mechanism contribute to the bactericidal activity of PS-NPs-treated iBMM.

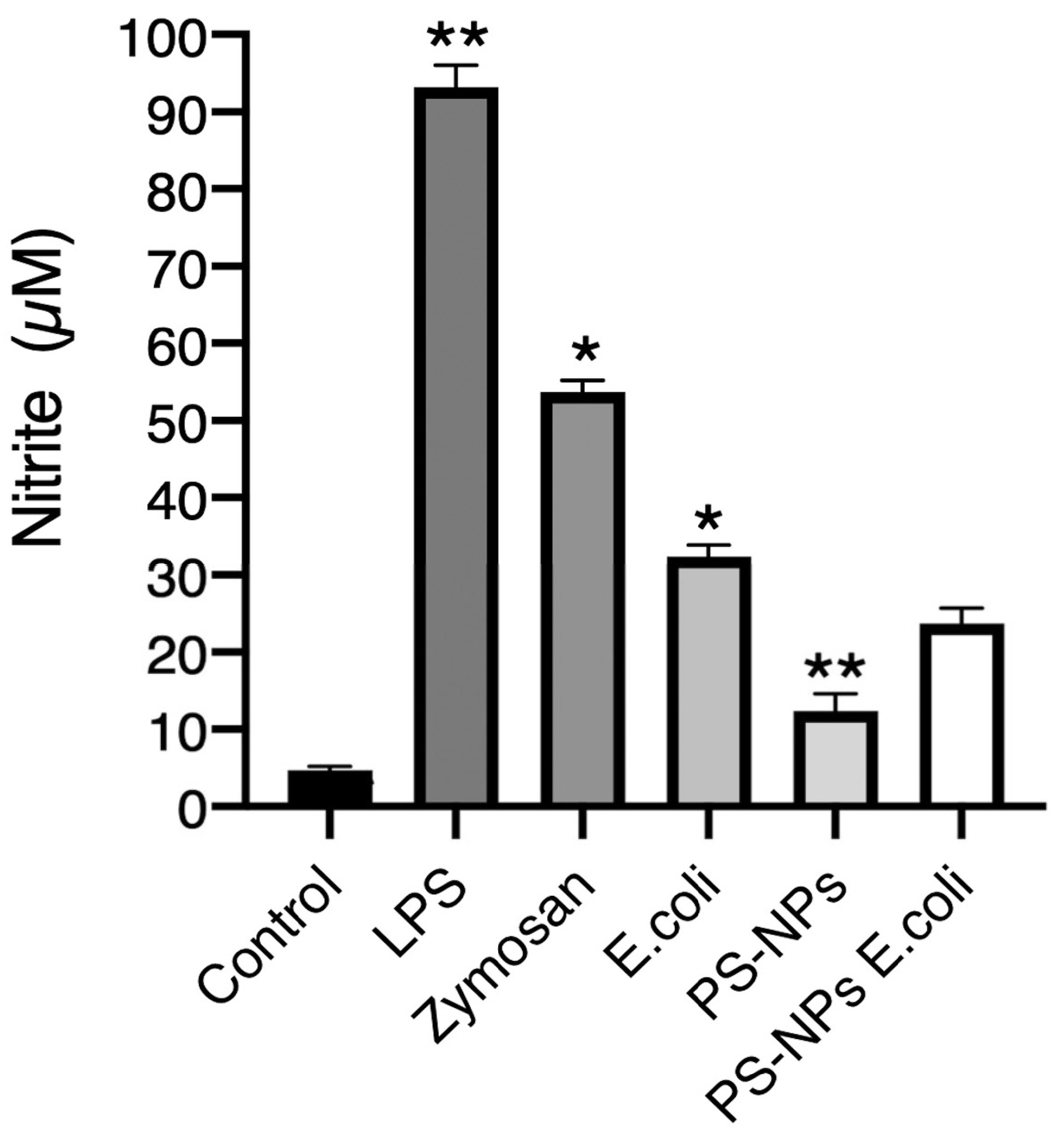

3.3. PS-NPs Impair Nitric Oxide Production

Nitric oxide (NO) is a potent microbicidal molecule [

30]. To assess its potential role in the enhanced bacterial killing observed in iBMM pretreated with PS-NPs, we determined its production in iBMM under various treatment conditions by measuring nitrites in cell supernatants. As expected, very low levels of nitrites were present in the supernatants of untreated cells, indicating minimal inducible nitric oxide synthase activity in the absence of stimulation, whereas exposure of iBMM to LPS, zymosan, and

E. coli led to high levels of nitrites in the supernatants (

Figure 5). These results indicate that these stimuli induced the production NO in iBMM. In contrast, exposure to PS-NPs stimulated the production of low NO levels, as determined by the levels of nitrites in the supernatants. Pretreatment of iBMM with PS-NPs resulted in a reduced production of NO in response to

E. coli, suggesting that PS-NPs may impair the ability of macrophages to produce NO. Taken together, these results suggest that NO plays a minor role in the increased bactericidal activity of macrophages exposed to PN-NPs.

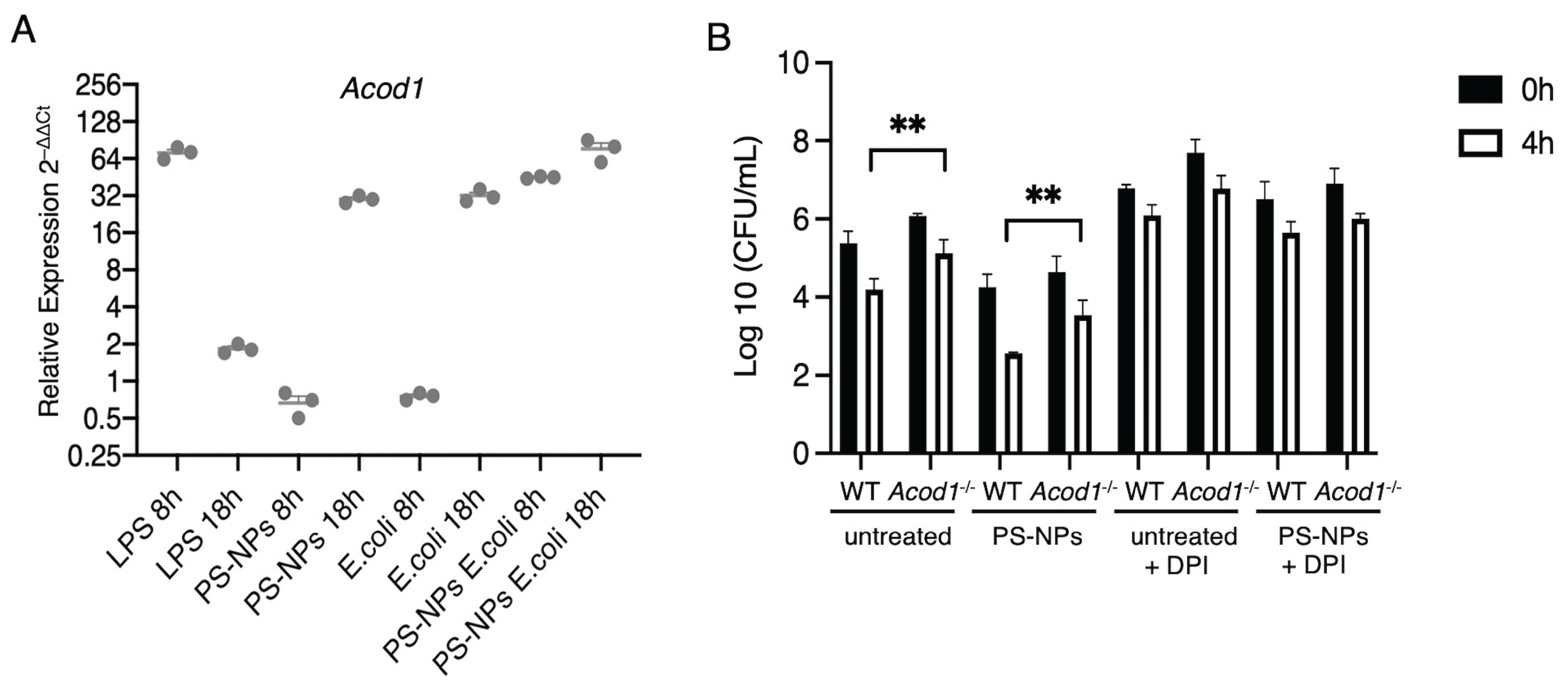

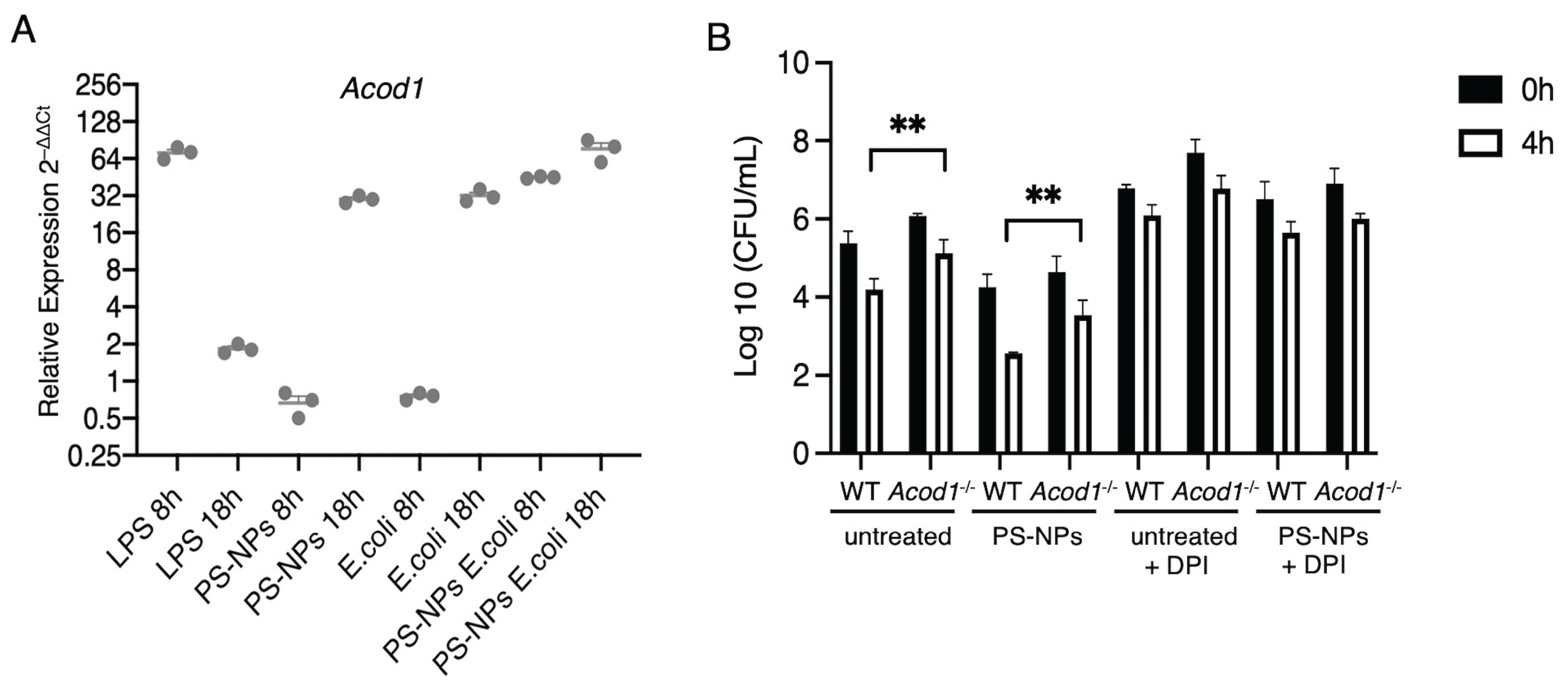

3.4. Itaconate Mediates PS-NPs-Induced Bactericidal Activity

Pro-inflammatory stimuli such as LPS induce the expression of cis-aconitate decarboxylase (ACOD1), which catalyzes the conversion of aconitate to itaconate [

31]. In addition to its anti-inflammatory properties, itaconate contributes to the antimicrobial activity of macrophages [

32,

33,

34]. We therefore sought to investigate the possible impact PS-NPs exposure on the expression of

Acod1.

Figure 6A illustrates the relative expression levels of the

Acod1 in iBMM exposed to either LPS, PS-NPs,

E. coli, and the combination of PS-NPs-

E. coli, at 8h and 18h post-exposure. Whereas LPS induced a strong but transient upregulation of

Acod1, exposure to PS-NPs or

E. coli led to increased and sustained

Acod1 expression over 18 h. Strikingly, exposure to PS-NPs and

E. coli induced a strong expression of

Acod1 at 8 h post-exposure, which further increased at 18 h. This suggests a synergistic effect of the PS-NPs and

E. coli in inducing robust

Acod1 expression. Having shown that the combination of PS-NPs and

E. coli induced high levels of

Acod1 expression, we next assessed the potential impact of aconitate on the bactericidal activity of BMMs. To this end, wild type (WT) and

Acod1-/- BMMs were either exposed

E. coli alone or to the combination of PS-NPs and

E. coli. As found with iBMMs, WT BMMs exposed to PS-NPs exhibited significantly enhanced bactericidal activity compared to untreated BMMs (

Figure 6B). In the absence of

Acod1, we observed a significant reduction in the bactericidal activity of both untreated and PS-NPs-exposed BMMs (

Figure 6B), consistent with a role for itaconate in mediating bactericidal activity of macrophages [

32,

33]. Inhibition of the NADPH oxidase with DPI markedly attenuated bacterial clearance in both WT and

Acod1-/- BMM, exposed or not to PS-NPs (

Figure 6B), suggesting that both NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS production and itaconate contribute to the enhanced bactericidal activity induced by PS-NPs.

4. Discussion

This study aimed at investigating the localization of PS-NPs in macrophages, as well as at studying their potential impact on the bactericidal activity of these cells. We obtained evidence that in iBMMs, PS-NPs accumulate in the endolysosomal compartment, as well as in the ER. Moreover, we showed that pre-exposure to PS-NPs increases the bactericidal activity of macrophages. Further, we observed that ROS generated by the NADPH oxidase and the Krebs cycle-derived metabolite itaconate are both contributing to the increased bactericidal activity of PS-NPs-exposed macrophages. These data provides an insight on the potential impact of NPs on the function of innate immune cells.

Owing to their small sizes, nanoparticles are readily internalized through endocytosis by macrophages [

14,

35]. As previously reported in several cell types exposed to NPs of various composition [

14,

18], we found that PS-NPs accumulated mainly in the endolysosomal compartment as well as in the ER. The consequences of PS-NPs accumulating within those intracellular compartments remains to be fully elucidated. In the case of endosomes and lysosomes, transiting of particles such as microbes through these compartments normally leads to their digestion and elimination. Lysosomal accumulation of undigestible material may impair the function of those degradative compartments, as previously shown in the murine microglial cell line BV2 exposed to PS-NPs [

36,

37]. In the case of the ER, it is unclear whether PS-NPs reach this central organelle through vesicular trafficking or through direct contact. Given the central role played the ER in protein and lipid synthesis and transport, as well as carbohydrate metabolism [

38], it is reasonable to assume that accumulation of PS-NPs in this organelle may affect its function. Further investigations will be necessary to elucidate how PS-NPs traffic to the ER and to understand their impact on its function.

An important consequence of NPs exposure in different cell types including macrophages, is the generation of ROS [

14,

39,

40]. For instance, PE microplastics increase ROS generation in the macrophage-like cell lines U937 and THP-1 [

41]. Similarly, PET-NPs were reported to induce ROS production in the murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 [

42]. BMMs exposed to PS-NPs are no exception, as we detected the production of cellular and mitochondrial ROS. However, the exact mechanism through which PS-NPs induce ROS production in macrophages is not well understood. Disruption of mitochondrial function and impairment of the electron transport chain, and activation of inflammatory responses are part of the mechanisms that have been proposed to contribute to the generation of ROS [

40,

43,

44]. Production of ROS are central to the antimicrobial activity of macrophages [

45]. Our finding that exposure to PS-NPs increased the bactericidal activity of BMMs raised the possibility that is was mediated by ROS produced in response to PS-NPs. Using the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI, we obtained evidence that ROS produced by the NADPH oxidase play a significant role in the increased bactericidal activity of PS-NPs-exposed BMMs.

Several studies have investigated the role of itaconate in host-pathogen interactions [

32,

46]. The ACOD1/itaconate axis in macrophages is induced in response to various inflammatory stimuli such as bacteria and LPS, suggesting a role for itaconate in infection. Itaconate kills bacteria through a few mechanisms, including its actvity as a bacterial isocitrate lyase inhibitor [

32,

46]. In this context, our observation that exposure to PS-NPs alone or in combination to

E. coli stimulated high levels of

Acod1 expression suggested that itaconate contributes to the increased bactericidal activity of BMM exposed to PS-NPs. This possibiltiy was validated using PS-NPs-exposed

Acod1-/- BMM, which were significantly less bactericidal than PS-NPs-exposed WT BMMs. Interestingly, itaconate was shown to promote ROS production in the RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line in response to LPS [

47]. In normal macrophages, LPS promotes the pentose phosphate pathway by increasing expression of the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and of the 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase. This leads to an increase production of NADPH, an intermediate metabolite of the pentose phosphate pathway, and to an up-regulation of the NADPH oxidase activity [

47]. In LPS-stimulated

Acod1-/- RAW 264.7 cells, there was no increase in the expression of the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and of the 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, and no up-regulation of NADPH oxidase activity to produce ROS [

47]. Consistently, we found that the bactericidal activity of WT and

Acod1-/- BMMs was inhibited to a similar extent by DPI. Clearly, additional studies will be required to elucidate the contribution itaconate in macrophages exposed to PS-NPs. Furthermore, given the role of itaconate in the modulation of immune responses and inflammation [

31,

32,

46], it will be essential to assess the potential impact of itaconate in in vivo models of NPs exposure.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found that exposure of macrophages to PS-NPs stimulated ROS production and induced Acod1 expression, leading to an increased bactericidal activity. Future studies will be necessary to investigate the impact of other NPs of different composition which are increasingly present in the environment, including polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride, polypropylene, and polyethylene phtalate, on the microbicidal activity of macrophages.

Author Contributions

S.S.M.: Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing (original draft); A.D.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing - review and editing.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada - Plastic Science for a Cleaner Future (grant number 558452-2020 ALLRP).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Jessy Tremblay (Confocal microscopy and Flow cytometry Facility of INRS) for expert assistance with confocal microscopy and flow cytometry; Dr Martin Olivier (McGill University) for kindly providing the LM-1 cell line; and Dr Hamlet Acevedo Ospina for assistance with q-RT-PCR analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

NO

ROS |

Nitric oxide

Reactive oxygen species |

| BMMs |

Bone marrow-derived macrophages |

| NPs |

Nanoplastics |

| PS |

Polystyrene |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| ER |

Endoplasmic reticulum |

References

- Jiang, B.; Kauffman, A. E.; Li, L.; McFee, W.; Cai, B.; Weinstein, J.; Lead, J. R.; Chatterjee, S.; Scott, G. I.; Xiao, S. Health impacts of environmental contamination of micro- and nanoplastics: a review. Environ Health Prev Med 2020, 25 (1), 29. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. N.; Deloid, G. M.; Zarbl, H.; Baw, J.; Demokritou, P. Micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) and their potential toxicological outcomes: State of science, knowledge gaps and research needs. Nanoimpact 2023, 32. DOI: ARTN 100481. [CrossRef]

- Arif, Y.; Mir, A. R.; Zielinski, P.; Hayat, S.; Bajguz, A. Microplastics and nanoplastics: Source, behavior, remediation, and multi-level environmental impact. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 356. DOI: ARTN 120618. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. C.; Gao, Y.; Wu, Q. H.; Yan, B.; Zhou, X. X. Quantifying the occurrence of polystyrene nanoplastics in environmental solid matrices via pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 440. DOI: ARTN 129855. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C. R. S.; Maestri, G.; Tochetto, G. A.; de Oliveira, J. L.; Stiegelmaier, E.; Fischer, T. V.; Immich, A. P. S. Nanoplastics: Unveiling Contamination Routes and Toxicological Implications for Human Health. Current Analytical Chemistry 2025, 21 (3), 175-190. [CrossRef]

- Vethaak, A. D.; Legler, J. Microplastics and human health. Science 2021, 371 (6530), 672-674. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. X.; Wang, Y. Q.; Wang, X. Y.; Lv, C. J.; Zhou, Q. F.; Jiang, G. B.; Yan, B.; Chen, L. X. Beyond the promise: Exploring the complex interactions of nanoparticles within biological systems. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 468. DOI: ARTN 133800. [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, D.; Iida, T.; Nakase, H. The Phagocytic Function of Macrophage-Enforcing Innate Immunity and Tissue Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 19 (1).From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Arango Duque, G.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 491. From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. [CrossRef]

- Flannagan, R. S.; Jaumouille, V.; Grinstein, S. The cell biology of phagocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2012, 7, 61-98. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Mottas, I.; Milosevic, A.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Bourquin, C. A rapid screening method to evaluate the impact of nanoparticles on macrophages. Nanoscale 2017, 9 (7), 2492-2504. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Tang, M. In vitro review of nanoparticles attacking macrophages: Interaction and cell death. Life Sci 2022, 307, 120840. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzfischer, M.; Ruoss, T. S.; Niechcial, A.; Lee, S. S.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Laimbacher, A.; Atrott, K.; Manzini, R.; Wilmink, M.; Linzmeier, L.; et al. Impact of Nanoplastic Particles on Macrophage Inflammation and Intestinal Health in a Mouse Model of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2024, 14 (16). From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M. G.; Casati, L.; Sauro, G.; Taurino, G.; Griffini, E.; Milani, C.; Ventura, M.; Bussolati, O.; Chiu, M. Biological Effects of Micro-/Nano-Plastics in Macrophages. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2025, 15 (5). From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. [CrossRef]

- Adler, M. Y.; Issoual, I.; Ruckert, M.; Deloch, L.; Meier, C.; Tschernig, T.; Alexiou, C.; Pfister, F.; Ramsperger, A. F.; Laforsch, C.; et al. Effect of micro- and nanoplastic particles on human macrophages. J Hazard Mater 2024, 471, 134253. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Mei, A.; Wang, X.; Shi, Q. Cellular absorption of polystyrene nanoplastics with different surface functionalization and the toxicity to RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 252, 114574. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Long, J.; Liu, L.; He, T.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, C.; Li, Z. A review of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and nanoparticle (NP) exposure. Life Sci 2017, 186, 33-42. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Wang, D. Y. Cellular Uptake, Transport, and Organelle Response After Exposure to Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Current Knowledge and Perspectives for Environmental and Health Risks. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2022, 260 (1). DOI: ARTN 12. [CrossRef]

- Manke, A.; Wang, L.; Rojanasakul, Y. Mechanisms of nanoparticle-induced oxidative stress and toxicity. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013, 942916. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Forget, G.; Siminovitch, K. A.; Brochu, S.; Rivest, S.; Radzioch, D.; Olivier, M. Role of host phosphotyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in the development of murine leishmaniasis. Eur J Immunol 2001, 31 (11), 3185-3196. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Descoteaux, A.; Matlashewski, G. c-fos and tumor necrosis factor gene expression in Leishmania donovani-infected macrophages. Mol Cell Biol 1989, 9 (11), 5223-5227. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P. D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the MTT Assay. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2018, 2018 (6). From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Arango Duque, G.; Fukuda, M.; Descoteaux, A. Synaptotagmin XI regulates phagocytosis and cytokine secretion in macrophages. J Immunol 2013, 190 (4), 1737-1745. [CrossRef]

- Matte, C.; Casgrain, P. A.; Séguin, O.; Moradin, N.; Hong, W. J.; Descoteaux, A. Leishmania major Promastigotes Evade LC3-Associated Phagocytosis through the Action of GP63. PLoS Pathogens 2016, 12 (6), e1005690. [CrossRef]

- Green, S. J.; Meltzer, M. S.; Hibbs, J. B., Jr.; Nacy, C. A. Activated macrophages destroy intracellular Leishmania major amastigotes by an L-arginine-dependent killing mechanism. J Immunol 1990, 144 (1), 278-283. From NLM Medline.

- Flannagan, R. S.; Cosio, G.; Grinstein, S. Antimicrobial mechanisms of phagocytes and bacterial evasion strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009, 7 (5), 355-366. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C. C.; Kettle, A. J. Redox reactions and microbial killing in the neutrophil phagosome. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 18 (6), 642-660. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Bode, K.; Hauri-Hohl, M.; Jaquet, V.; Weyd, H. Unlocking the power of NOX2: A comprehensive review on its role in immune regulation. Redox Biol 2023, 64, 102795. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.; Massari, M.; Marchese, S.; Ceccon, M.; Aalbers, F. S.; Corana, F.; Valente, S.; Mai, A.; Magnani, F.; Mattevi, A. A closer look into NADPH oxidase inhibitors: Validation and insight into their mechanism of action. Redox Biol 2020, 32, 101466. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Okda, M.; Spina, S.; Safaee Fakhr, B.; Carroll, R. W. The antimicrobial effects of nitric oxide: A narrative review. Nitric Oxide 2025, 155, 20-40. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L. A. J.; Artyomov, M. N. Itaconate: the poster child of metabolic reprogramming in macrophage function. Nature Reviews Immunology 2019, 19 (5), 273-281. [CrossRef]

- Peace, C. G.; O’Neill, L. A. The role of itaconate in host defense and inflammation. J Clin Invest 2022, 132 (2). From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Sun, H.; Boot, M.; Shao, L.; Chang, S. J.; Wang, W.; Lam, T. T.; Lara-Tejero, M.; Rego, E. H.; Galan, J. E. Itaconate is an effector of a Rab GTPase cell-autonomous host defense pathway against Salmonella. Science 2020, 369 (6502), 450-455. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, C.; Yang, F.; Zeng, Y. X.; Sun, P.; Liu, P.; Li, X. Itaconate is a lysosomal inducer that promotes antibacterial innate immunity. Mol Cell 2022, 82 (15), 2844-2857 e2810. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ma, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, Y. Systematic toxicity evaluation of polystyrene nanoplastics on mice and molecular mechanism investigation about their internalization into Caco-2 cells. J Hazard Mater 2021, 417, 126092. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Florance, I.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Gopinath, P. M.; Mukherjee, A. Exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics impairs lipid metabolism in human and murine macrophages in vitro. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2022, 238, 113612. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Florance, I.; Ramasubbu, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Polystyrene nanoplastics dysregulate lipid metabolism in murine macrophages in vitro. Toxicology 2021, 458, 152850. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, D. S.; Blower, M. D. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016, 73 (1), 79-94. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Li, P. Reactive Oxygen Species-Related Nanoparticle Toxicity in the Biomedical Field. Nanoscale Res Lett 2020, 15 (1), 115. From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G. L.; Lamarre, A. The impact of micro- and nanoplastics on immune system development and functions: Current knowledge and future directions. Reprod Toxicol 2025, 135, 108951. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Jo, J.; Acharya, M.; Maharjan, A.; Lee, D.; K, C. P.; Kim, C.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Heo, Y. Evaluation of potential toxicity of polyethylene microplastics on human derived cell lines. Sci Total Environ 2022, 838 (Pt 2), 156089. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Guzmán, J. C.; Bejtka, K.; Fontana, M.; Valsami-Jones, E.; Villezcas, A. M.; Vazquez-Duhalt, R.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A. G. Polyethylene terephthalate nanoparticles effect on RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Microplastics and Nanoplastics 2022, 2 (1). DOI: ARTN 9. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Palic, D. Micro- and nano-plastics activation of oxidative and inflammatory adverse outcome pathways. Redox Biol 2020, 37, 101620. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.; Yao, X.; Yan, X.; Peng, R. Environmental nanoplastics induce mitochondrial dysfunction: A review of cellular mechanisms and associated diseases. Environ Pollut 2025, 382, 126695. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Lam, G. Y.; Huang, J.; Brumell, J. H. The many roles of NOX2 NADPH oxidase-derived ROS in immunity. Semin Immunopathol 2010, 32 (4), 415-430. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C. Itaconate or how I learned to stop avoiding the study of immunometabolism. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18 (3), e1010361. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y. Itaconic acid exerts anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects via promoting pentose phosphate pathway to produce ROS. Sci Rep 2021, 11 (1), 18173. From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

PS-NPs are not cytotoxic to iBMMs. Cell viability was assessed in iBMMs exposed to 100 nm PS-NPs at concentrations of 0 to 10 µg/mL PS-NPs for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed by an MTT assay. Quantification of cell viability is expressed relative to the exposed iBMMs. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 1.

PS-NPs are not cytotoxic to iBMMs. Cell viability was assessed in iBMMs exposed to 100 nm PS-NPs at concentrations of 0 to 10 µg/mL PS-NPs for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed by an MTT assay. Quantification of cell viability is expressed relative to the exposed iBMMs. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Intracellular localization of PS-NPs in iBMMs. iBMMs were exposed to 1 μg/mL fluorescent PS-NPs for 24 h. Colocalization of PS-NPs (red) with (A) LAMP1 (white), (B) Rab7 (green), (C) calnexin (white), and (D) p115 (white) was assessed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Colocalized pixels are shown in white. Representative images from 3 independent experiments are shown.

Figure 2.

Intracellular localization of PS-NPs in iBMMs. iBMMs were exposed to 1 μg/mL fluorescent PS-NPs for 24 h. Colocalization of PS-NPs (red) with (A) LAMP1 (white), (B) Rab7 (green), (C) calnexin (white), and (D) p115 (white) was assessed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Colocalized pixels are shown in white. Representative images from 3 independent experiments are shown.

Figure 3.

PS-NPs increase the bactericidal activity of iBMMs. iBMMs (untreated or exposed to 1 μg/mL PS-NPs for 24 h) were incubated with E. coli at a ratio of 20 bacteria to 1 macrophage. After washing, cells were incubated with DMEM containing gentamicin for 20 min (0 h time point) or for an additional 4 h. Where indicated, 10 μM DPI was added 1 h prior to the addition of E. coli. After each time point, cells were washed and lysed; lysates were diluted and plated in agar plates. Macrophage bactericidal activity was evaluated by counting CFU. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **p < 0.01.

Figure 3.

PS-NPs increase the bactericidal activity of iBMMs. iBMMs (untreated or exposed to 1 μg/mL PS-NPs for 24 h) were incubated with E. coli at a ratio of 20 bacteria to 1 macrophage. After washing, cells were incubated with DMEM containing gentamicin for 20 min (0 h time point) or for an additional 4 h. Where indicated, 10 μM DPI was added 1 h prior to the addition of E. coli. After each time point, cells were washed and lysed; lysates were diluted and plated in agar plates. Macrophage bactericidal activity was evaluated by counting CFU. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **p < 0.01.

Figure 4.

ROS levels in iBMMs exposed to PS-NPs. (A) Total and (B) mitochondrial ROS produced by iBMMs were assessed by flow cytometry using CellROX Deep Green Reagent and MitoSOX™ Mitochondrial probe, respectively. iBMM, untreated or exposed to 1 μg/mL PS-NPs for 18 h, were incubated with either zymosan, or E. coli for 1 h. Quantification of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for each condition, relative to the untreated control, is shown. Data are presented as mean MFI ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

ROS levels in iBMMs exposed to PS-NPs. (A) Total and (B) mitochondrial ROS produced by iBMMs were assessed by flow cytometry using CellROX Deep Green Reagent and MitoSOX™ Mitochondrial probe, respectively. iBMM, untreated or exposed to 1 μg/mL PS-NPs for 18 h, were incubated with either zymosan, or E. coli for 1 h. Quantification of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for each condition, relative to the untreated control, is shown. Data are presented as mean MFI ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Exposure to PS-NPs impairs NO production. iBMM, untreated or exposed to PS-NPs for 18 h were incubated with either LPS (100 ng /mL), zymosan (5:1), or E. coli (20:1) for 18 h. Cell culture supernatants were then probed for the presence of nitrites. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data are represented as mean concentration ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Exposure to PS-NPs impairs NO production. iBMM, untreated or exposed to PS-NPs for 18 h were incubated with either LPS (100 ng /mL), zymosan (5:1), or E. coli (20:1) for 18 h. Cell culture supernatants were then probed for the presence of nitrites. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data are represented as mean concentration ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Acod1 contributes to the bactericidal activity of PS-NPs-exposed BMM. A. iBMMs were incubated with either LPS (100 ng/mL), PS-NPs (1 μg/mL), or E. coli (20:1) for 8 h and 18 h. Additionally, iBMMs exposed to PS-NPs for 18 h were incubated with E. coli (20:1) for 8 h and 18 h. Acod1 levels were assayed via quantitative RT-PCR. Data are represented as (mean ±SEM). B. BMMs from WT and Acod1-/- mice (untreated or exposed to 1 μg/mL PS-NPs for 18 h) were incubated with E. coli at a ratio of 20 bacteria to 1 macrophage. Where indicated, 10 μM DPI was added 1 h prior to the addition of E. coli. After washing, cells were incubated with DMEM containing gentamicin for 20 min (0 h time point) or for an additional 4 h. After each time point, cells were washed and lysed; lysates were diluted and plated in agar plates. Macrophage bactericidal activity was evaluated by counting CFU. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Acod1 contributes to the bactericidal activity of PS-NPs-exposed BMM. A. iBMMs were incubated with either LPS (100 ng/mL), PS-NPs (1 μg/mL), or E. coli (20:1) for 8 h and 18 h. Additionally, iBMMs exposed to PS-NPs for 18 h were incubated with E. coli (20:1) for 8 h and 18 h. Acod1 levels were assayed via quantitative RT-PCR. Data are represented as (mean ±SEM). B. BMMs from WT and Acod1-/- mice (untreated or exposed to 1 μg/mL PS-NPs for 18 h) were incubated with E. coli at a ratio of 20 bacteria to 1 macrophage. Where indicated, 10 μM DPI was added 1 h prior to the addition of E. coli. After washing, cells were incubated with DMEM containing gentamicin for 20 min (0 h time point) or for an additional 4 h. After each time point, cells were washed and lysed; lysates were diluted and plated in agar plates. Macrophage bactericidal activity was evaluated by counting CFU. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).