5. Conclusions

This research study consists of the development of an aeroelastic optimization framework which with appropriate configuration is useful for either mass or similarity optimization between a sub-scale model and a reference wing. The core of the framework consists of the aeroelastic analysis (static and dynamic) combined with the appropriate functions for the objectives and constraints and an ACO algorithm (MIDACO). The parameterization of the wing includes geometric parameters and thicknesses for the stiffness distribution and 10 lumped masses for the mass distribution (for the scaling problem).

A mass optimization problem was initially set up for the uCRM wing. In this case, there were only geometric and thickness parameters (e.g., spar positions, number of ribs, number of stringers and thicknesses at specified control points). Stiffness, stress, and flutter constraints were included with target values being set based on the literature and the Civil Aviation Regulations FAR-25. The optimizer converged at a structural mass of while all the constraints were satisfied. Of interest are the optimized variables’ values. The thickness parameters decrease gradually along the wing, except of the Yehudi break where maximum stress usually arises. The spars’ position, as expected, converged around the position of the airfoil’s maximum thickness in order to optimize the stiffness in the x direction while the underestimated drag (because of the potential flow implemented by DLM does not require so much stiffness in the z direction. Finally, the ribs’ number converged to 51, which is close to the optimal solution presented in [37].

As far as the scaling problem is concerned, the objectives and constraints were modified in order to meet similarity requirements. In fact the problem’s objectives were the RMS error of in-flight shape difference and the average MAC of the N modes that were selected to optimize. The constraints included were the equality of each eigenfrequency, the equality of the model’s mass to a target value defined by the scaling parameters, and the avoidance of maximum stresses greater than the maximum allowable. Also, a constraint to avoid flutter at a certain speed for the optimal solution was considered.

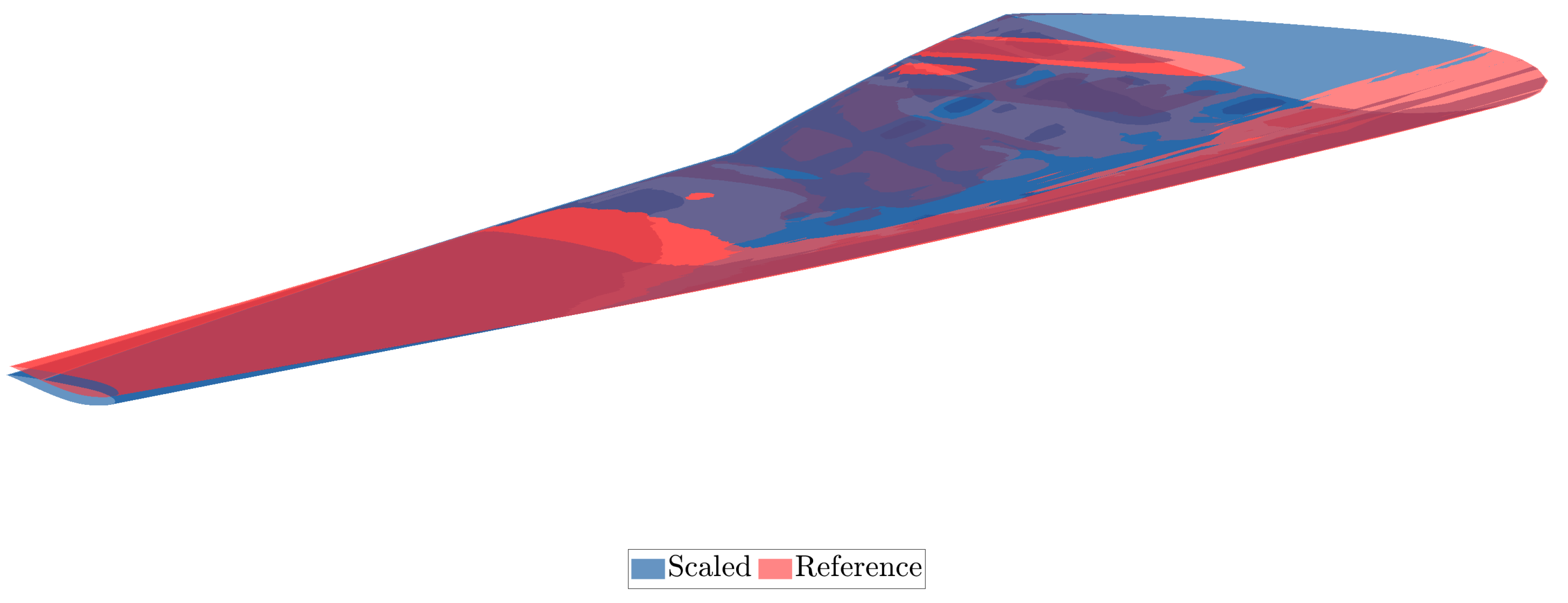

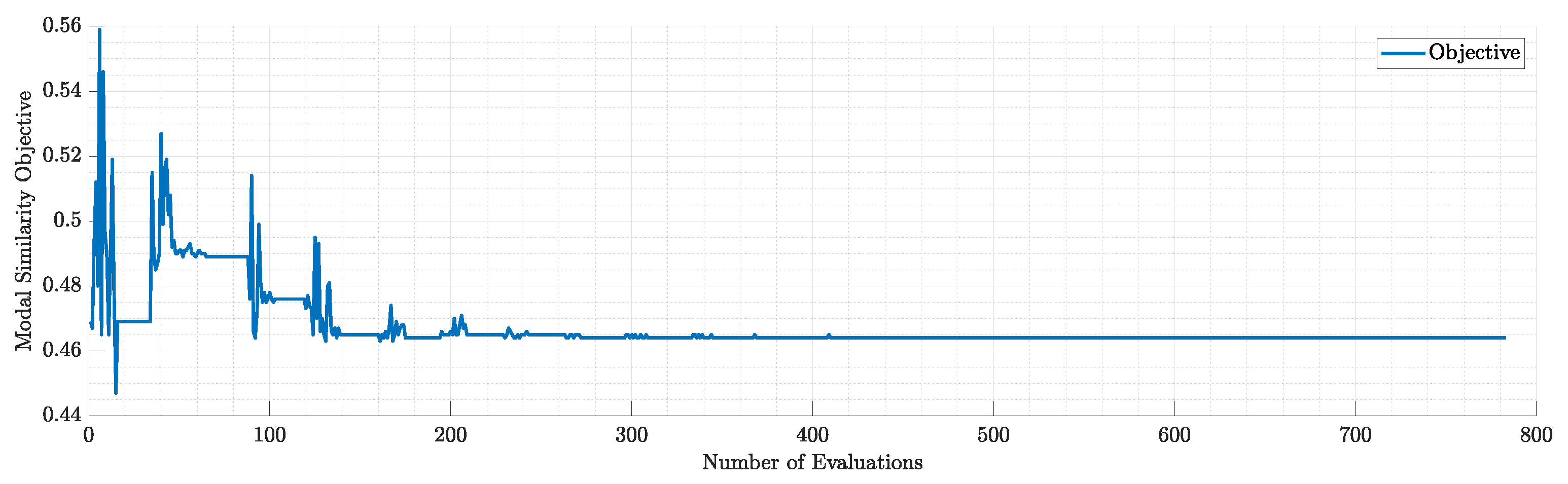

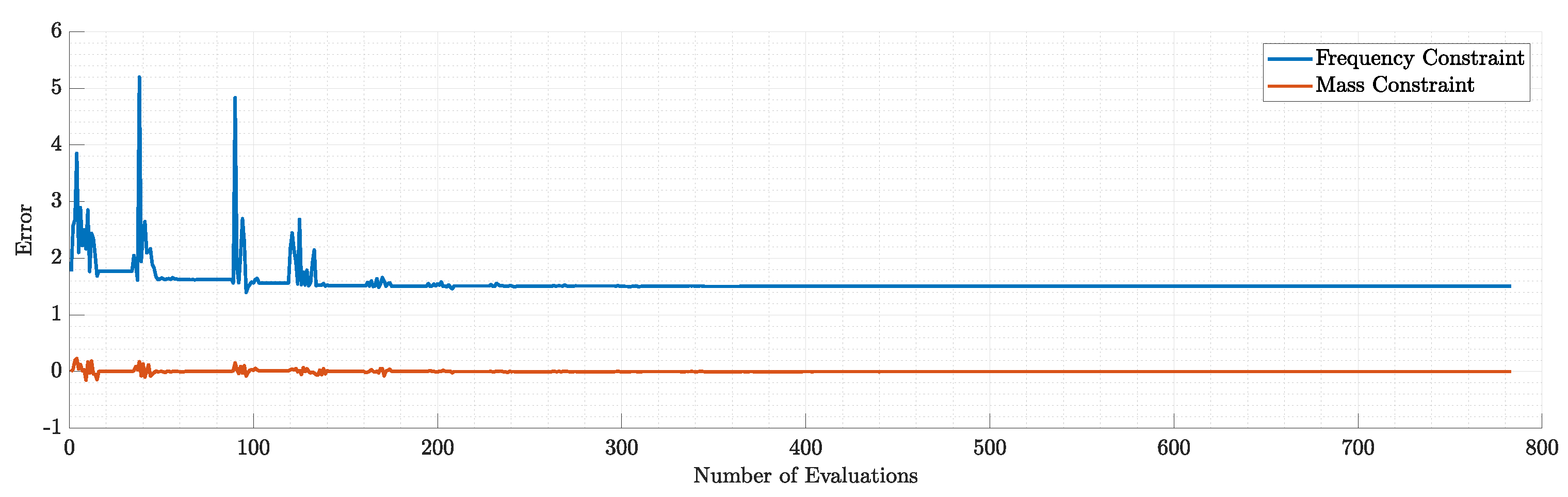

The pre-described optimization problem was first run with a single-step approach, for N=10 modes to optimize and the material was aluminium. The results were deemed unacceptable. The RMS error of the in-flight shape difference converged to the value of 0.45, indicating bad matching of the static aeroelastic response. The constraints of the modal response were satisfied but the modal similarity was quite low indicating no similarity at all. These problems were addressed by changing the material to magnesium, changing the modes to match to N=5 and the one-step approach to a two-step (serial) approach in order to reduce the computing time and get acceptable results quicker. After those alterations, the optimizer converged to acceptable values indicating a good matching of both the static aeroelastic and modal response. In fact the RMS error of the in-flight shape difference of the optimal solution is and the mean MAC value of the first 5 modes is . The constraints of the problem were also satisfied but there is room for improvement mainly in terms of frequency error. As far as the flutter is concerned, the flutter speed of the optimal solution is way beyond the diving speed, indicating no flutter.

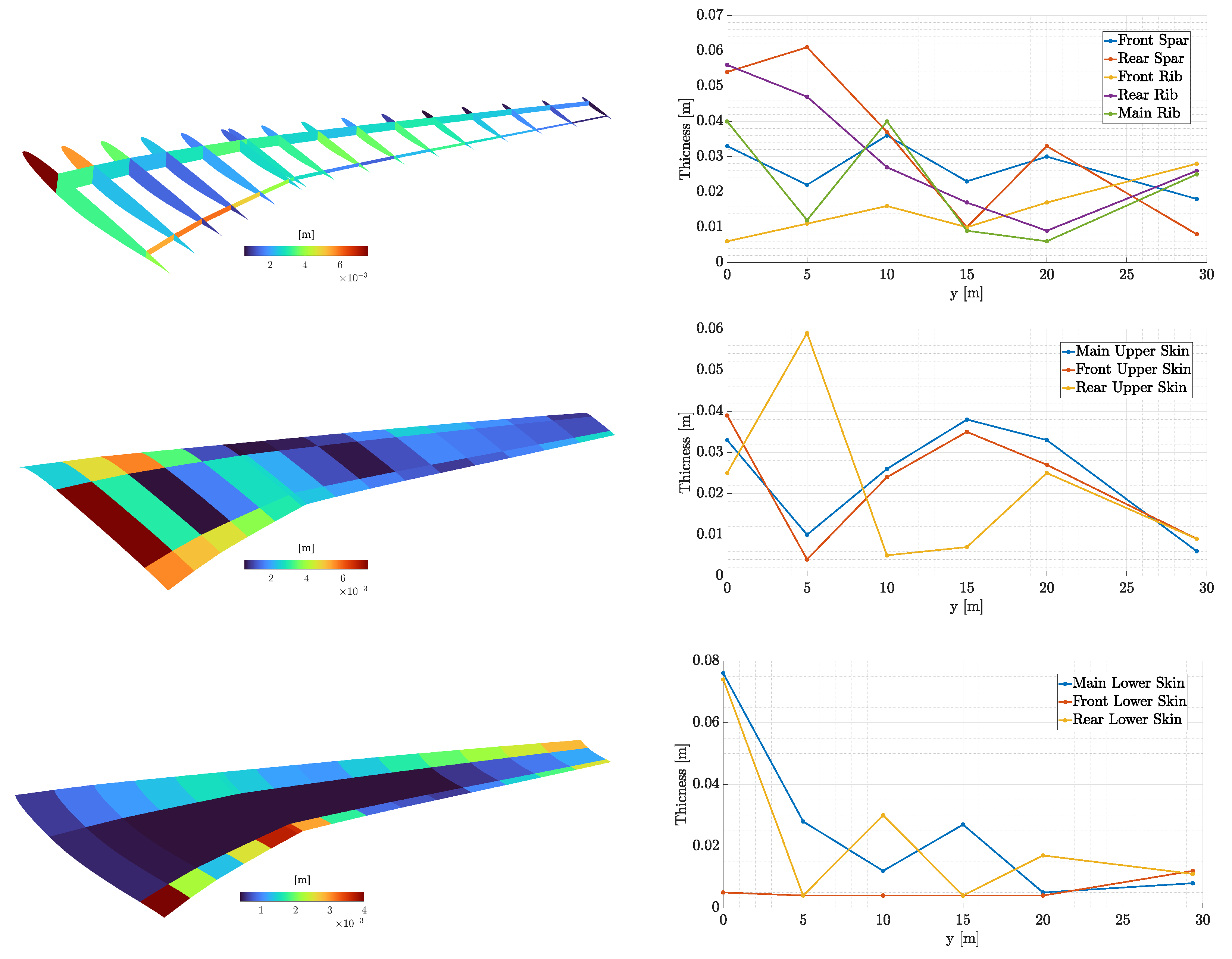

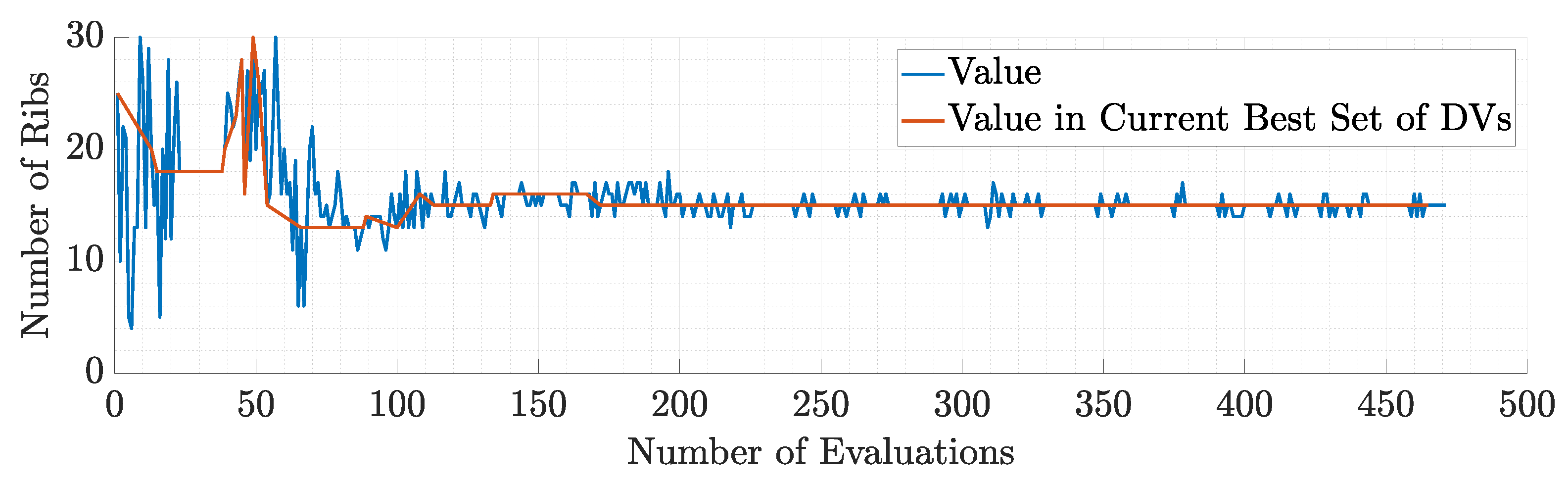

Of interest is the location of the spars, which are quite close to the leading and trailing edges, in contrast to the reference wing. This is likely due to the increased stiffness presented by the sub-scale structure given the reduced aerodynamic loads. Placing the spars towards the edges, reduces the stiffness around the x-axis and thus the structure becomes more flexible thus avoiding the very low values of the thicknesses and thus the construction difficulties. The number of ribs was also reduced to 15 in order to reduce the torsional stiffness of the wing indicating the significance of the parameterization of ribs’ number. Future implementations in the framework are directed towards the following:

The investigation of other types of materials (such as wood or composites) and combination of them would greatly increase the design space and ensure the presence (or absence) of the effects of the full model (such as skin buckling).

The calculation of derivatives in order to include a gradient-based optimizer in the framework. It will give the opportunity for a more efficient optimization since we take advantage of a gradient-free optimizer.

Introduction of a high fidelity aerodynamic solver such as Euler or RANS. As already mentioned, the potential theory upon which the DLM is based, underestimates the drag distribution while overestimating the lift. A high-fidelity solver will avoid such problems and provide more accurate load prediction.

The parameterization of the number of spars will give the opportunity to design wings with more than two spars and it will greatly increase the design space. Also, it will allow the design of other types of wings such as military aircraft wings that incorporate multi-spar configurations.

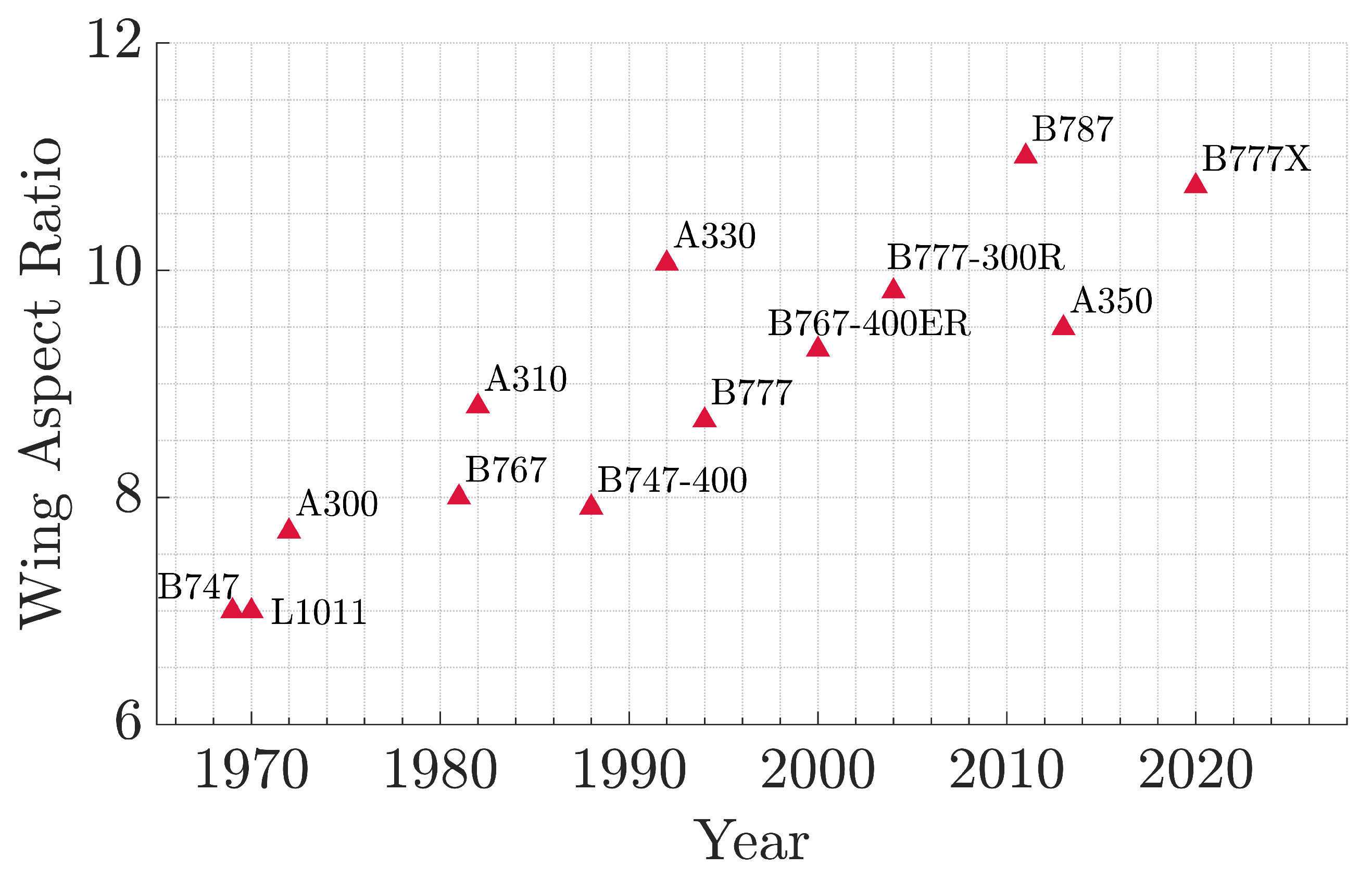

Figure 1.

Commercial aircraft wings aspect ratio trend [

4].

Figure 1.

Commercial aircraft wings aspect ratio trend [

4].

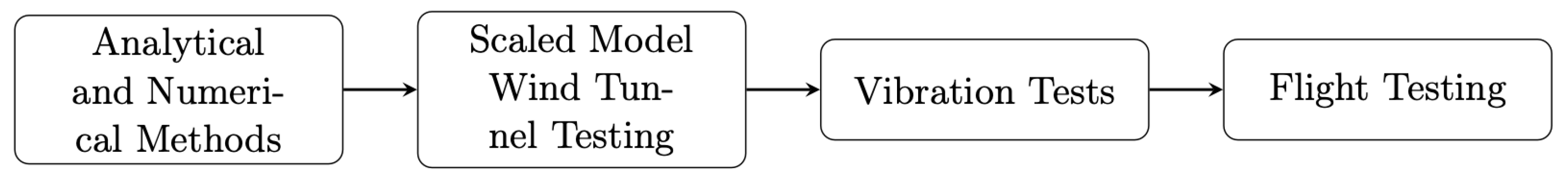

Figure 2.

Modern approach for aeroelastic effects investigation.

Figure 2.

Modern approach for aeroelastic effects investigation.

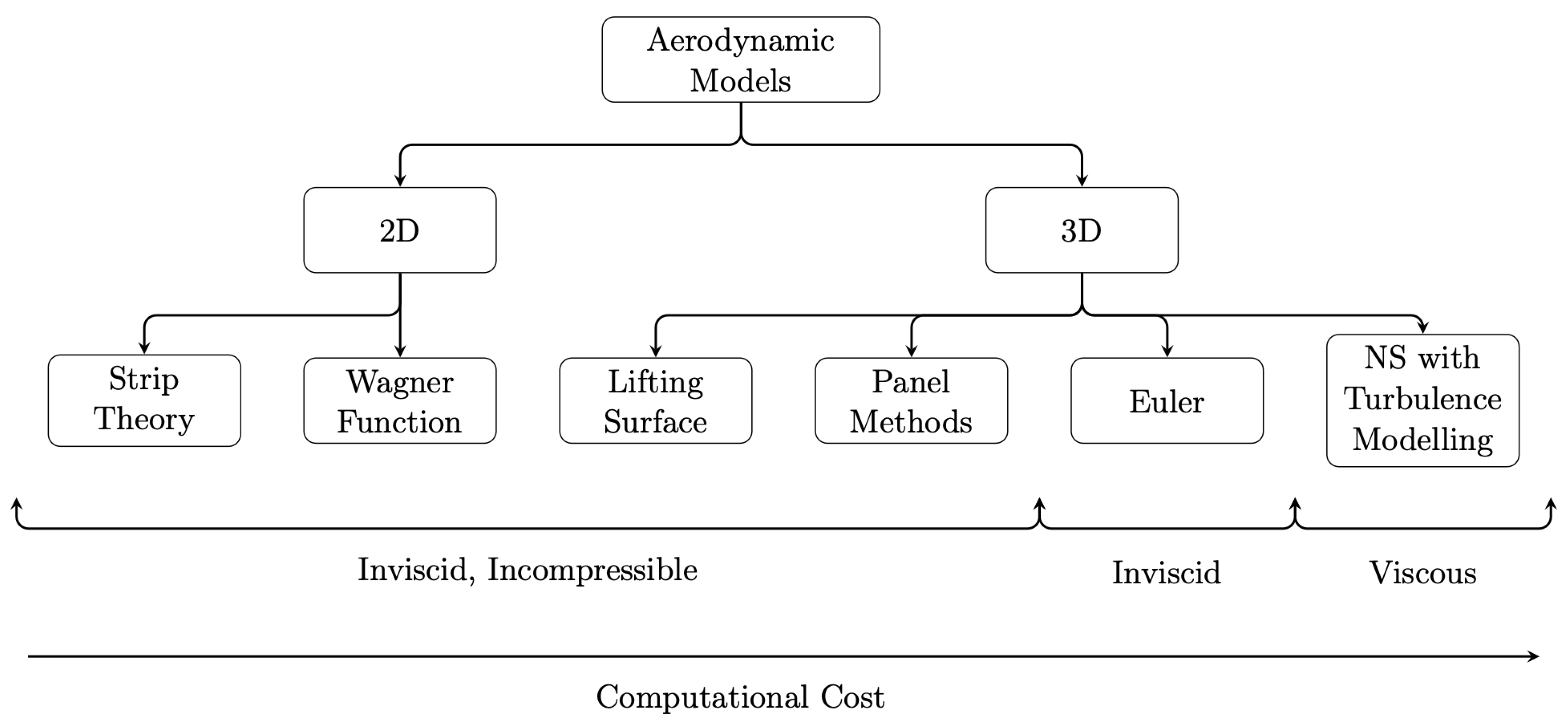

Figure 3.

Aerodynamic models used in aeroelastic calculations.

Figure 3.

Aerodynamic models used in aeroelastic calculations.

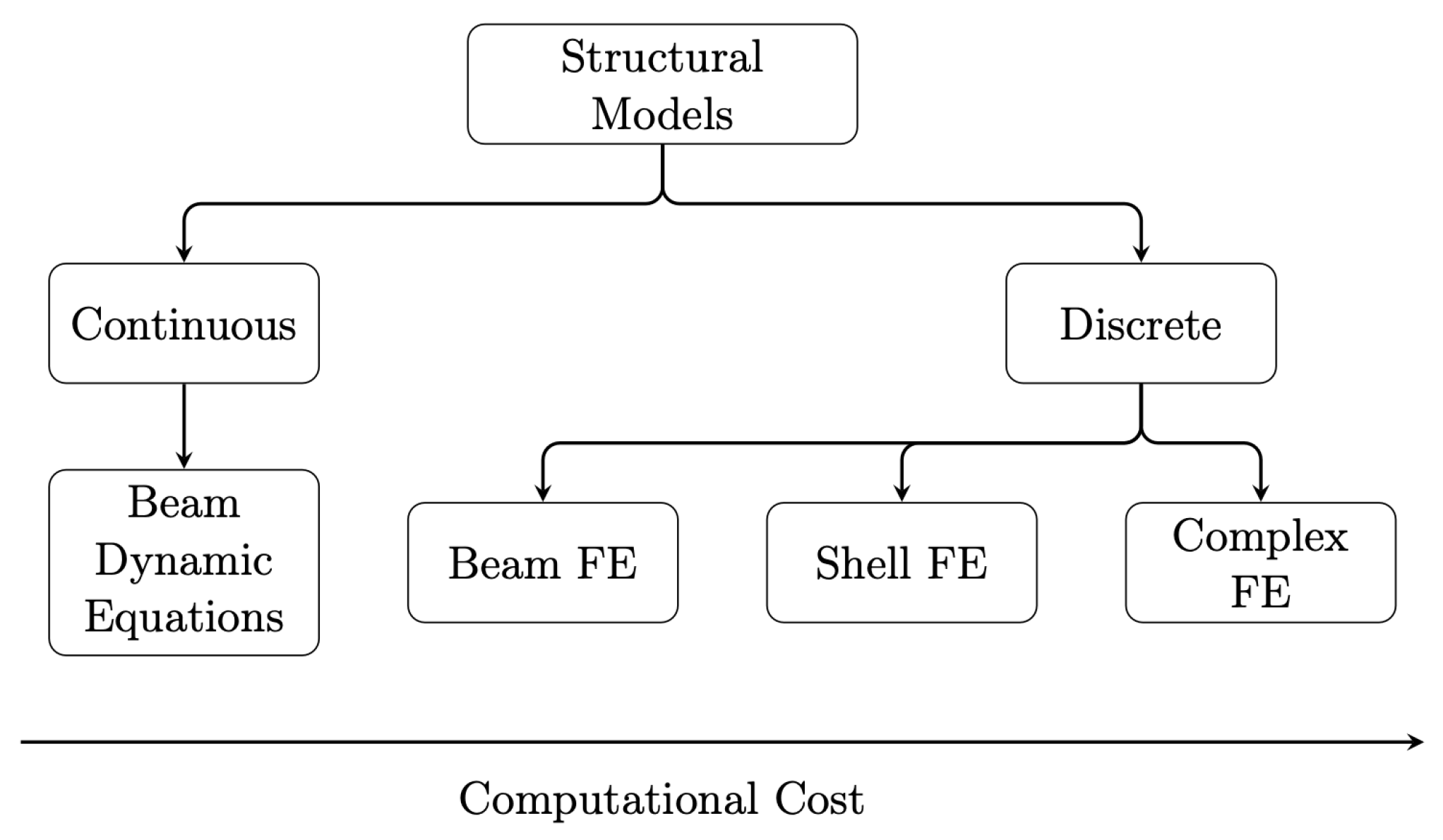

Figure 4.

Structural models used in aeroelastic calculations.

Figure 4.

Structural models used in aeroelastic calculations.

Figure 5.

The American experimental aircraft Grumman X-29.

Figure 5.

The American experimental aircraft Grumman X-29.

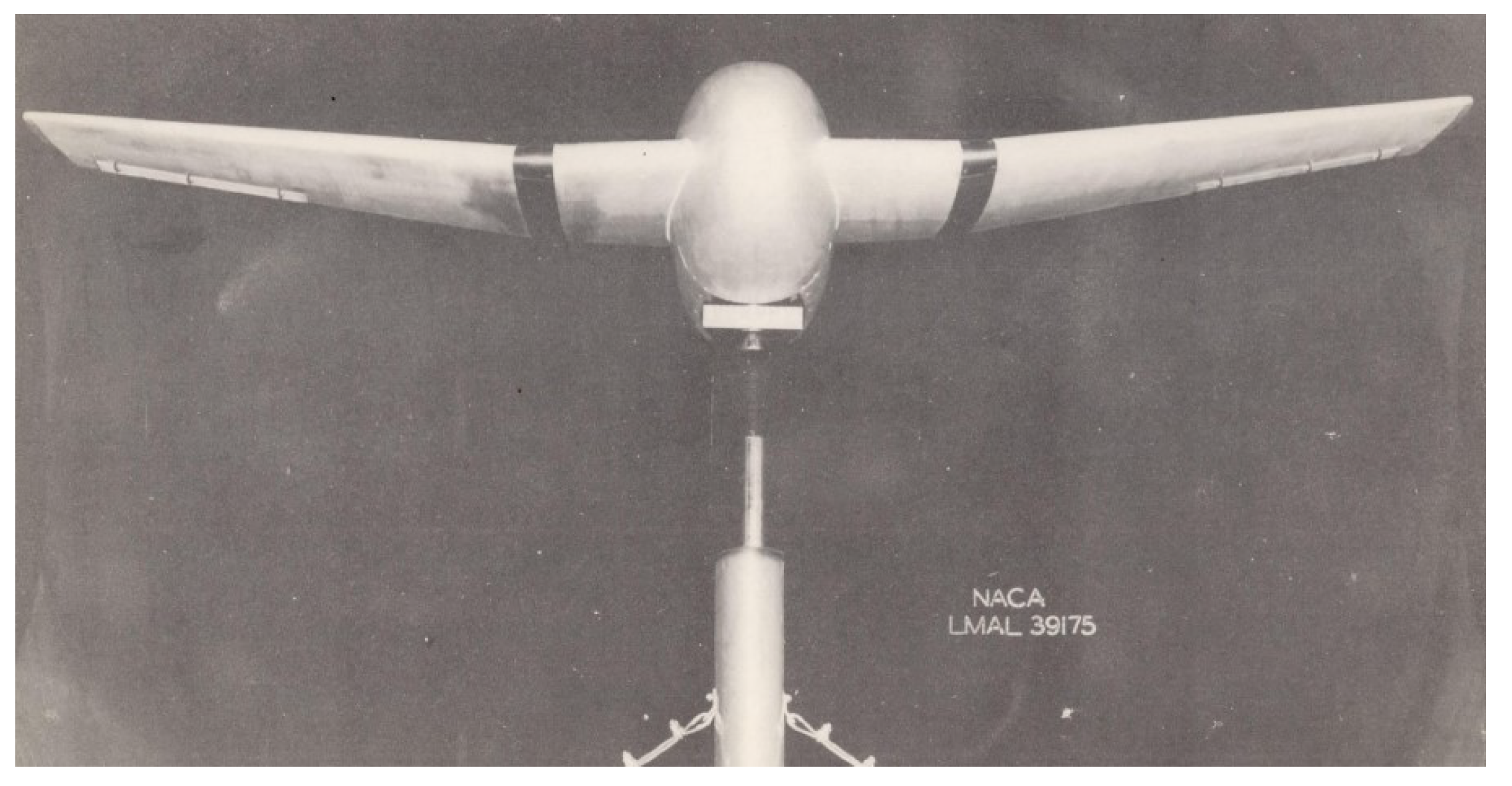

Figure 6.

High subsonic flutter model of Grumman F6F in NACA Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory [19].

Figure 6.

High subsonic flutter model of Grumman F6F in NACA Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory [19].

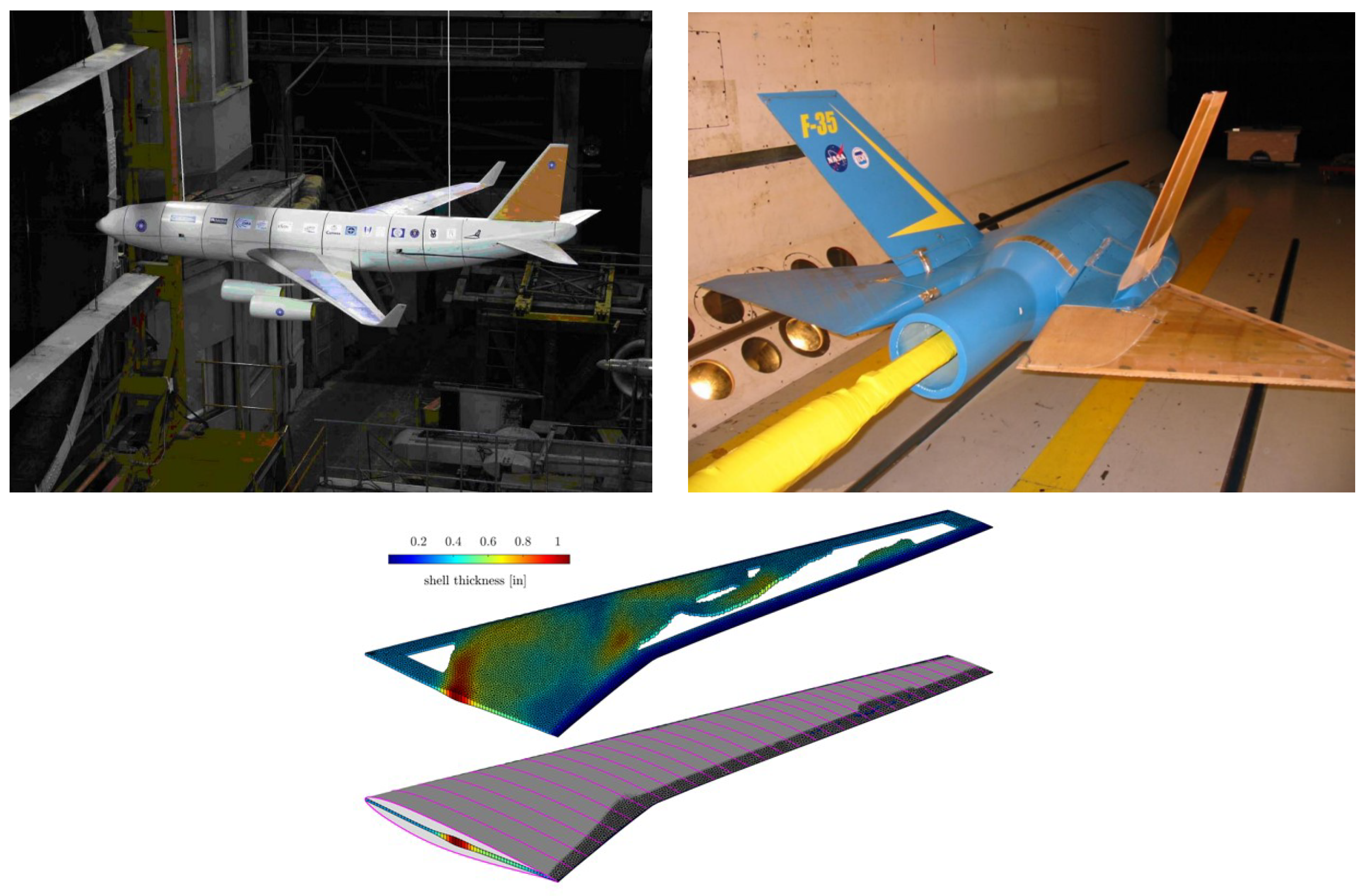

Figure 7.

Recent aeroelastic scaling practises ([20,21,22]).

Figure 7.

Recent aeroelastic scaling practises ([20,21,22]).

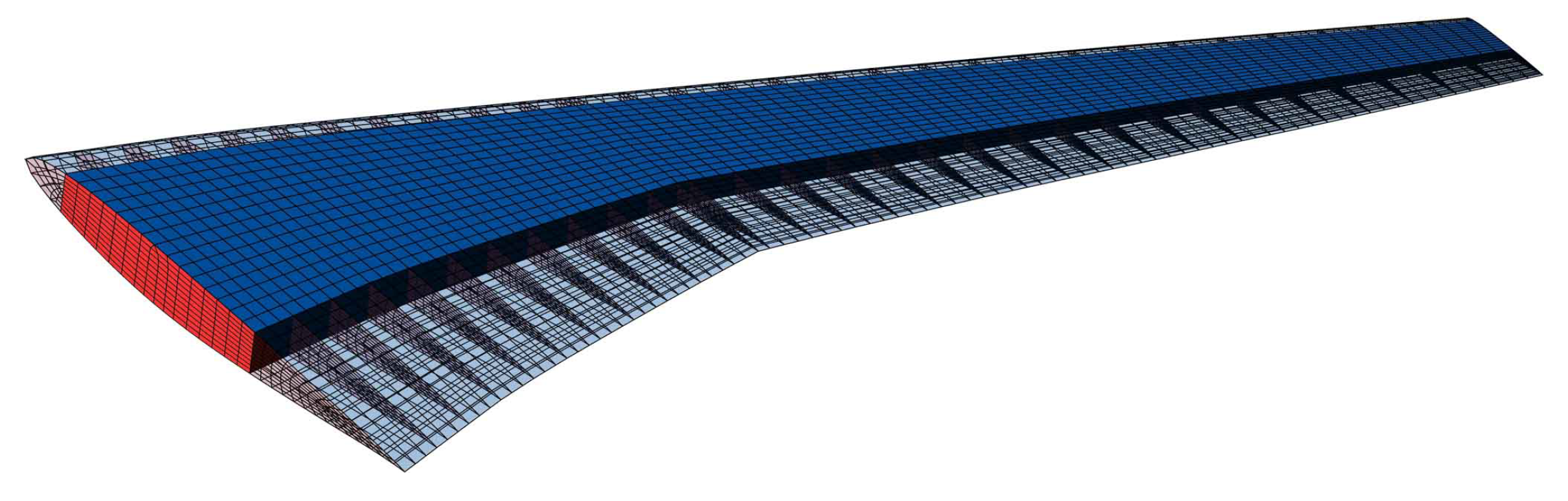

Figure 8.

Example of FEM mesh with shell and beam elements.

Figure 8.

Example of FEM mesh with shell and beam elements.

Figure 9.

3D wing surface modeled by flat panels.

Figure 9.

3D wing surface modeled by flat panels.

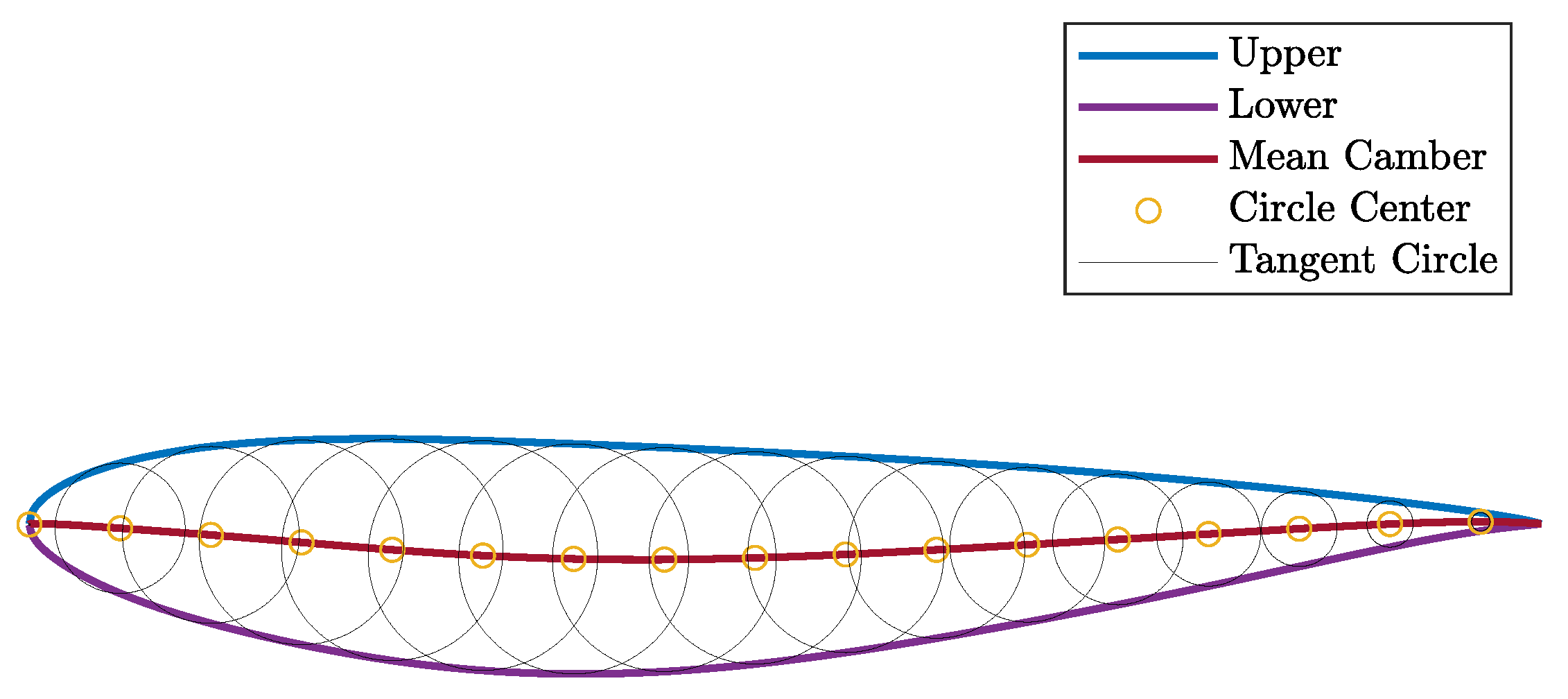

Figure 10.

Mean camber line construction method.

Figure 10.

Mean camber line construction method.

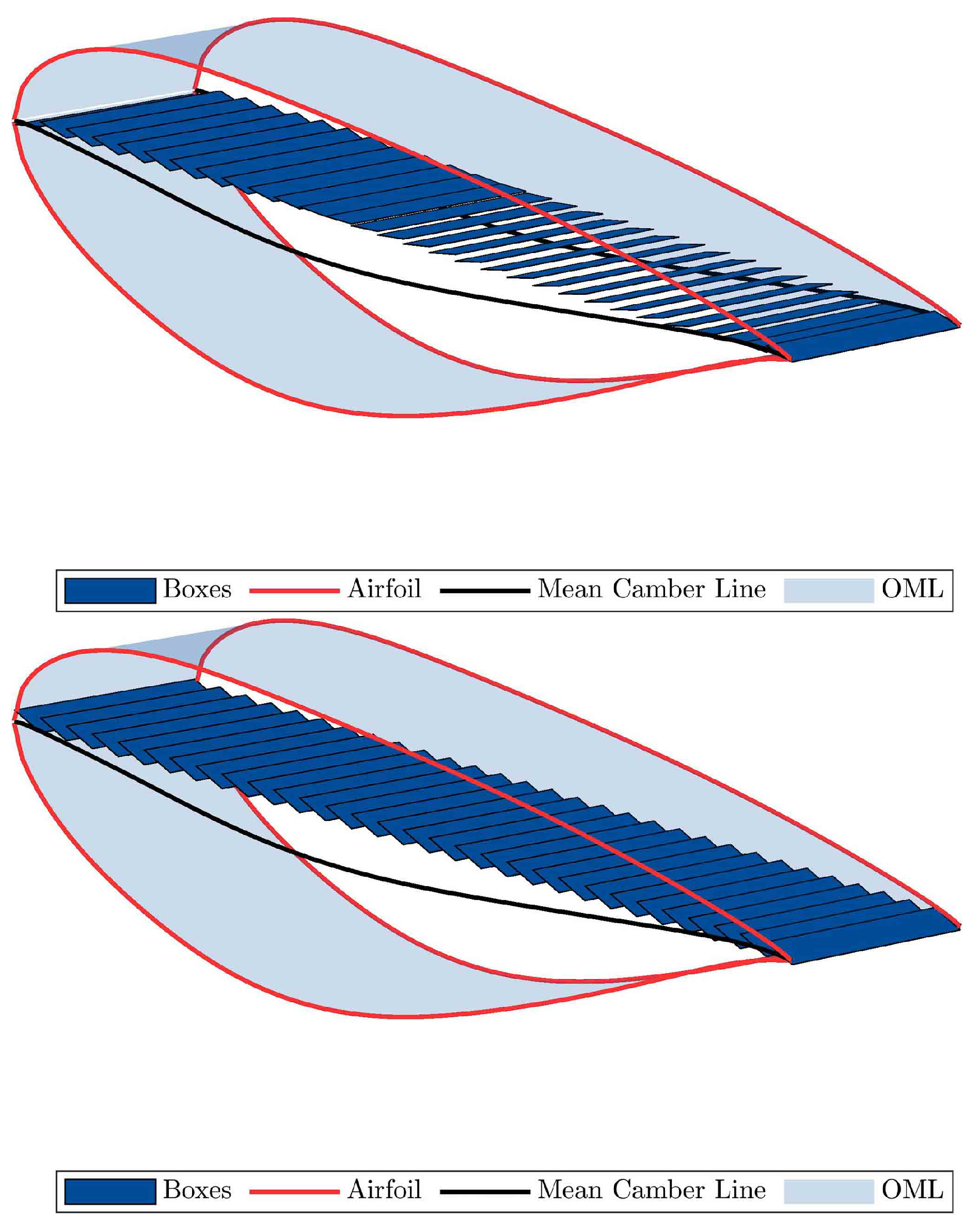

Figure 11.

W2GJ matrix influence on boxes’ inclination.

Figure 11.

W2GJ matrix influence on boxes’ inclination.

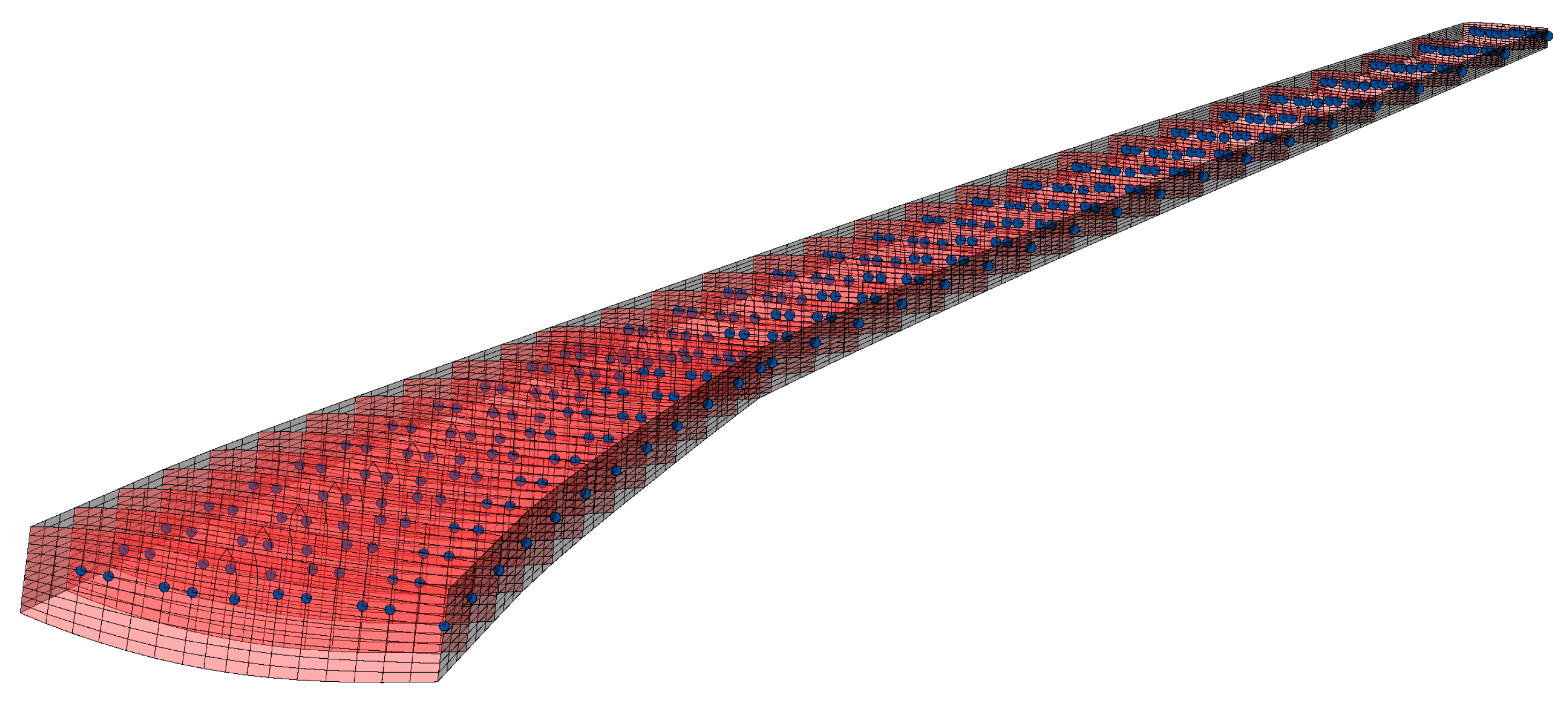

Figure 12.

Example of coupling nodes in a wing.

Figure 12.

Example of coupling nodes in a wing.

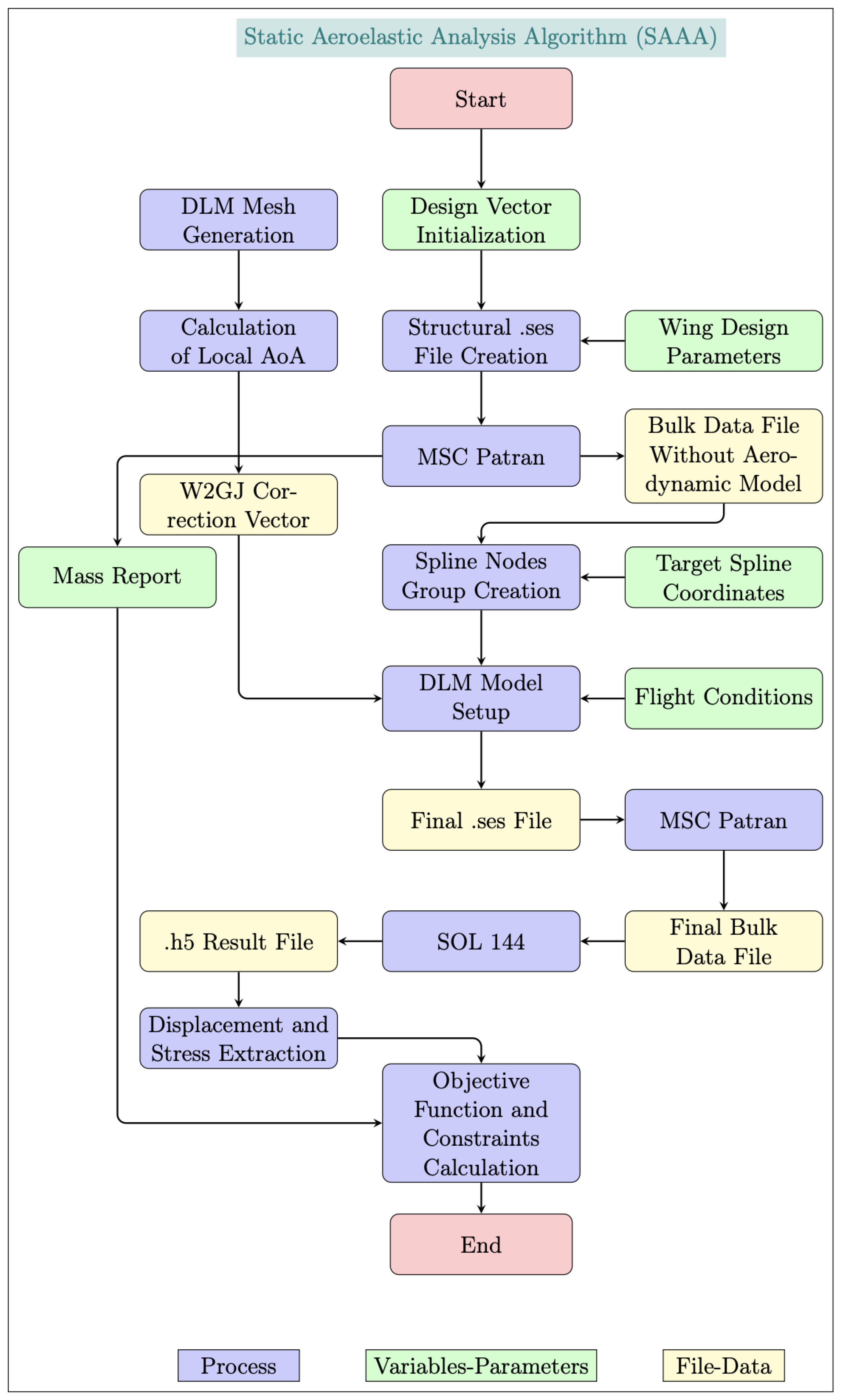

Figure 13.

Static aeroelastic framework flowchart.

Figure 13.

Static aeroelastic framework flowchart.

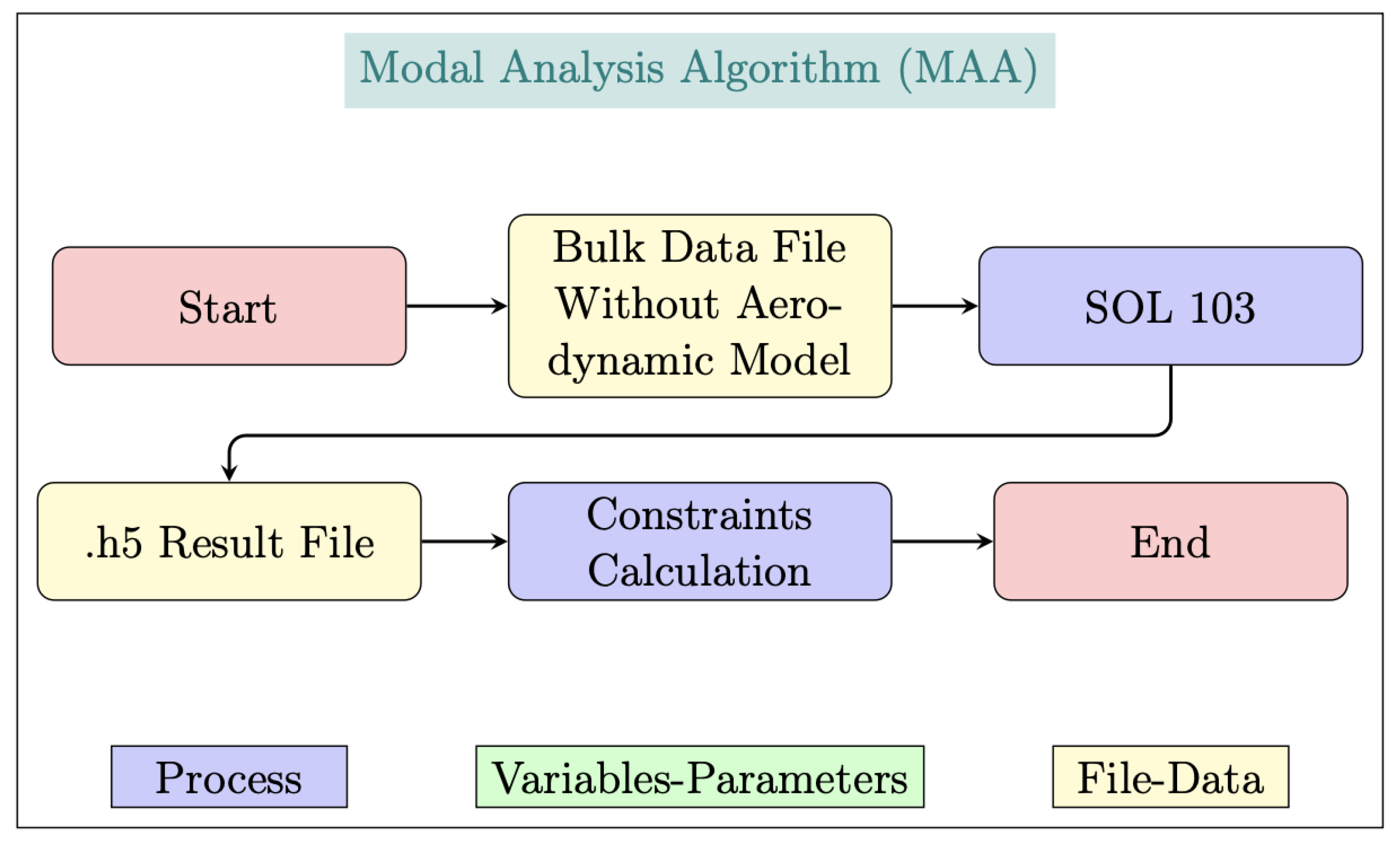

Figure 14.

Modal analysis framework flowchart.

Figure 14.

Modal analysis framework flowchart.

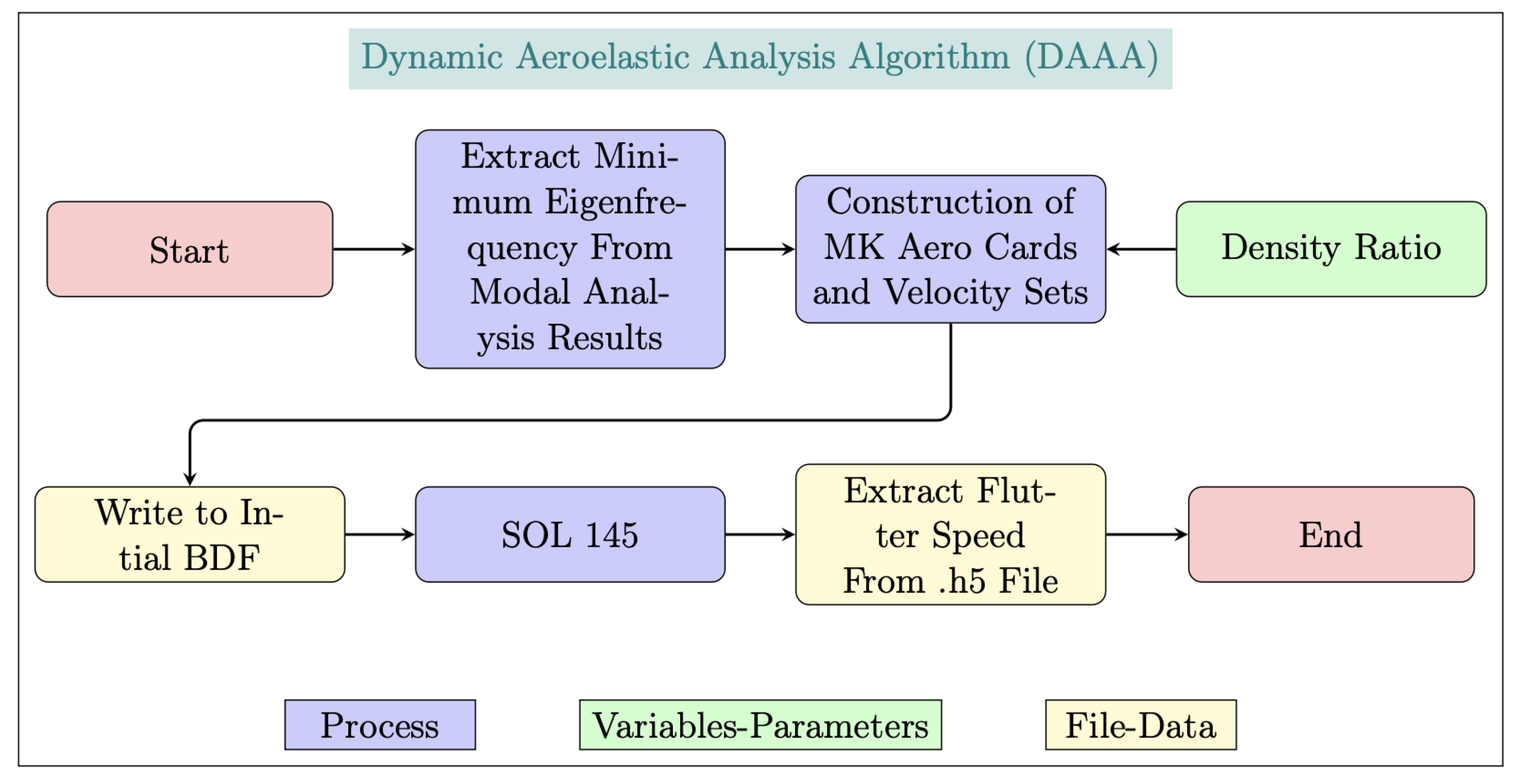

Figure 15.

Dynamic aeroelastic framework flowchart.

Figure 15.

Dynamic aeroelastic framework flowchart.

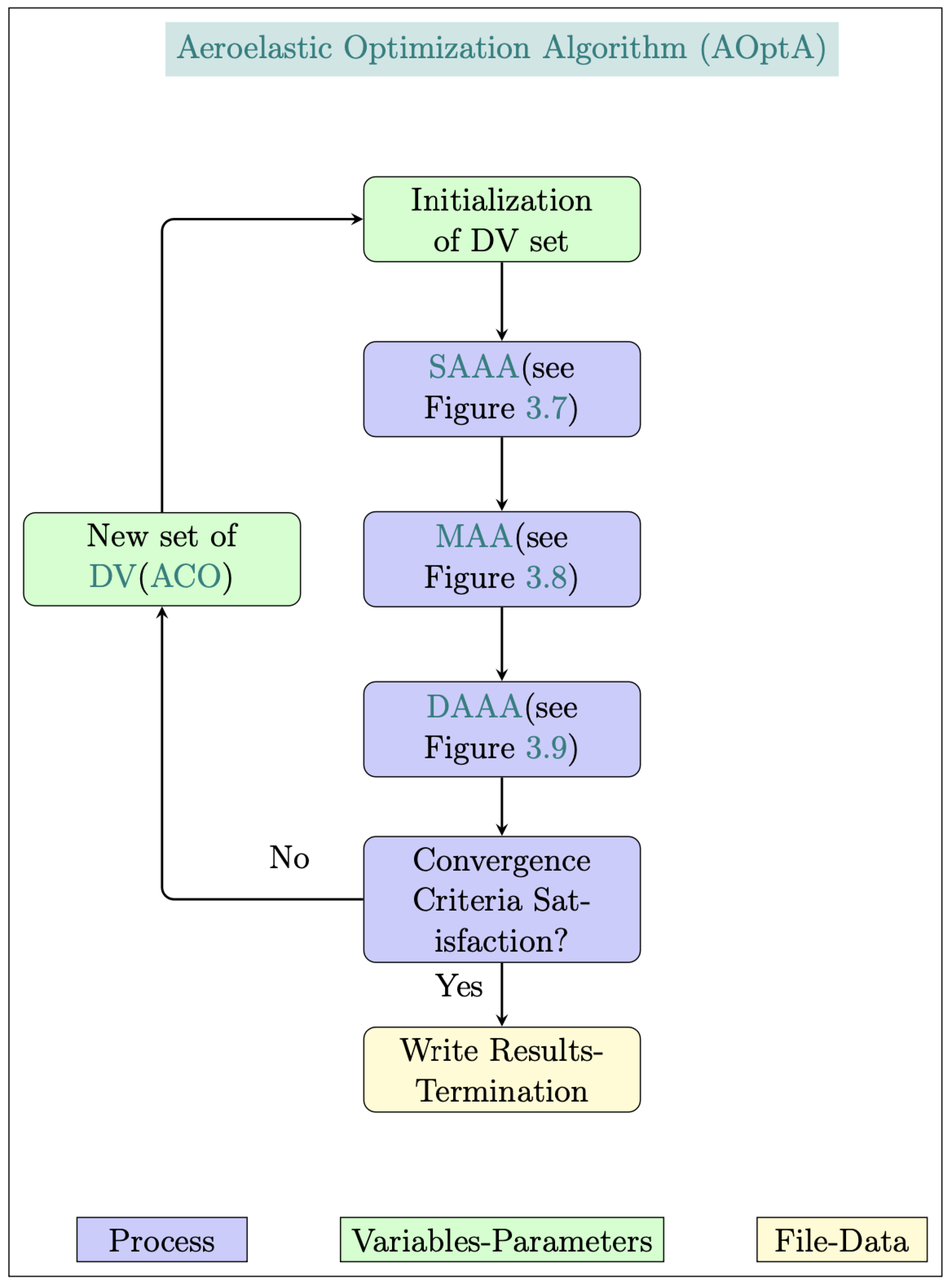

Figure 16.

Aeroelastic optimization framework flowchart.

Figure 16.

Aeroelastic optimization framework flowchart.

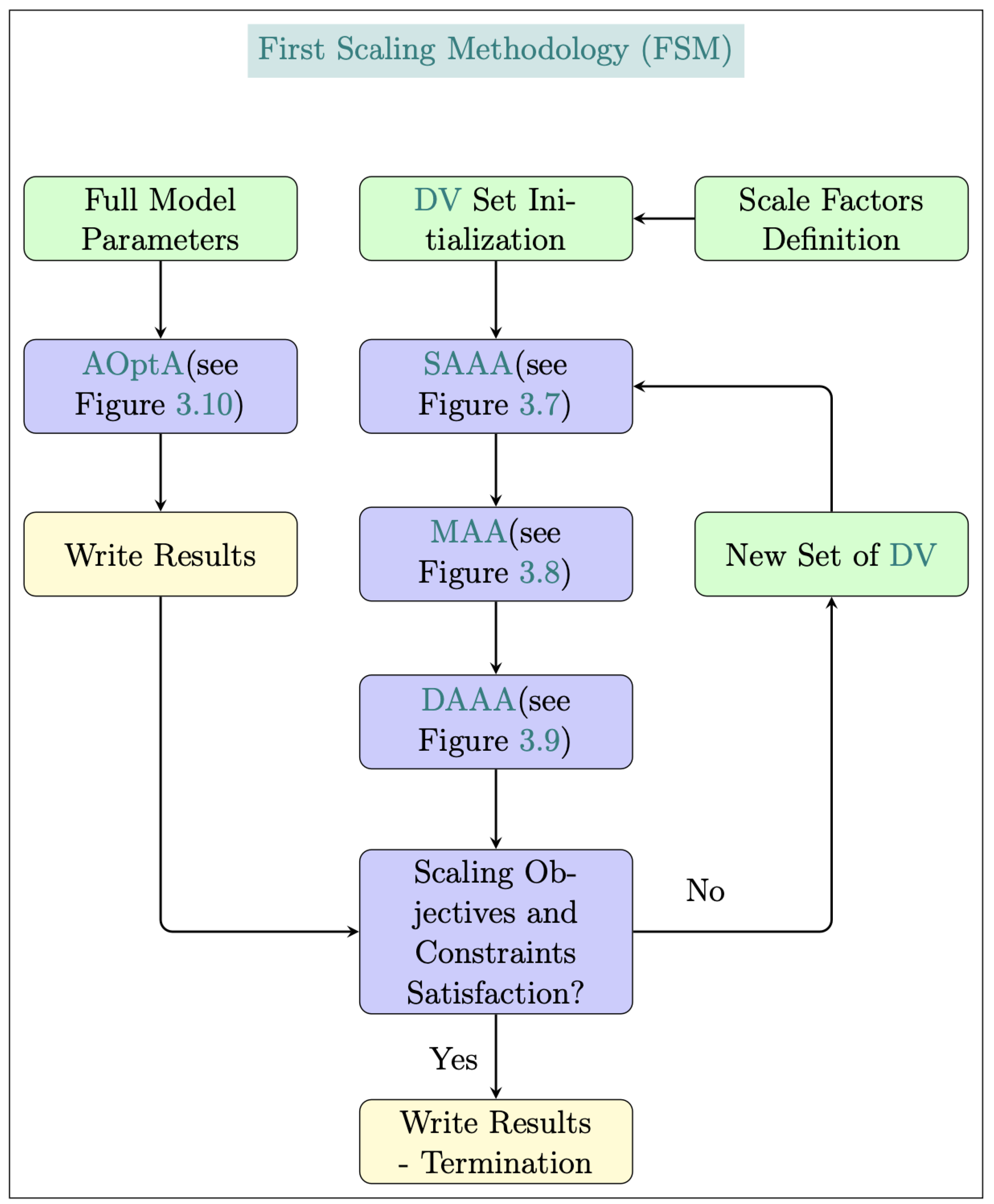

Figure 17.

Aeroelastic scaling framework flowchart.

Figure 17.

Aeroelastic scaling framework flowchart.

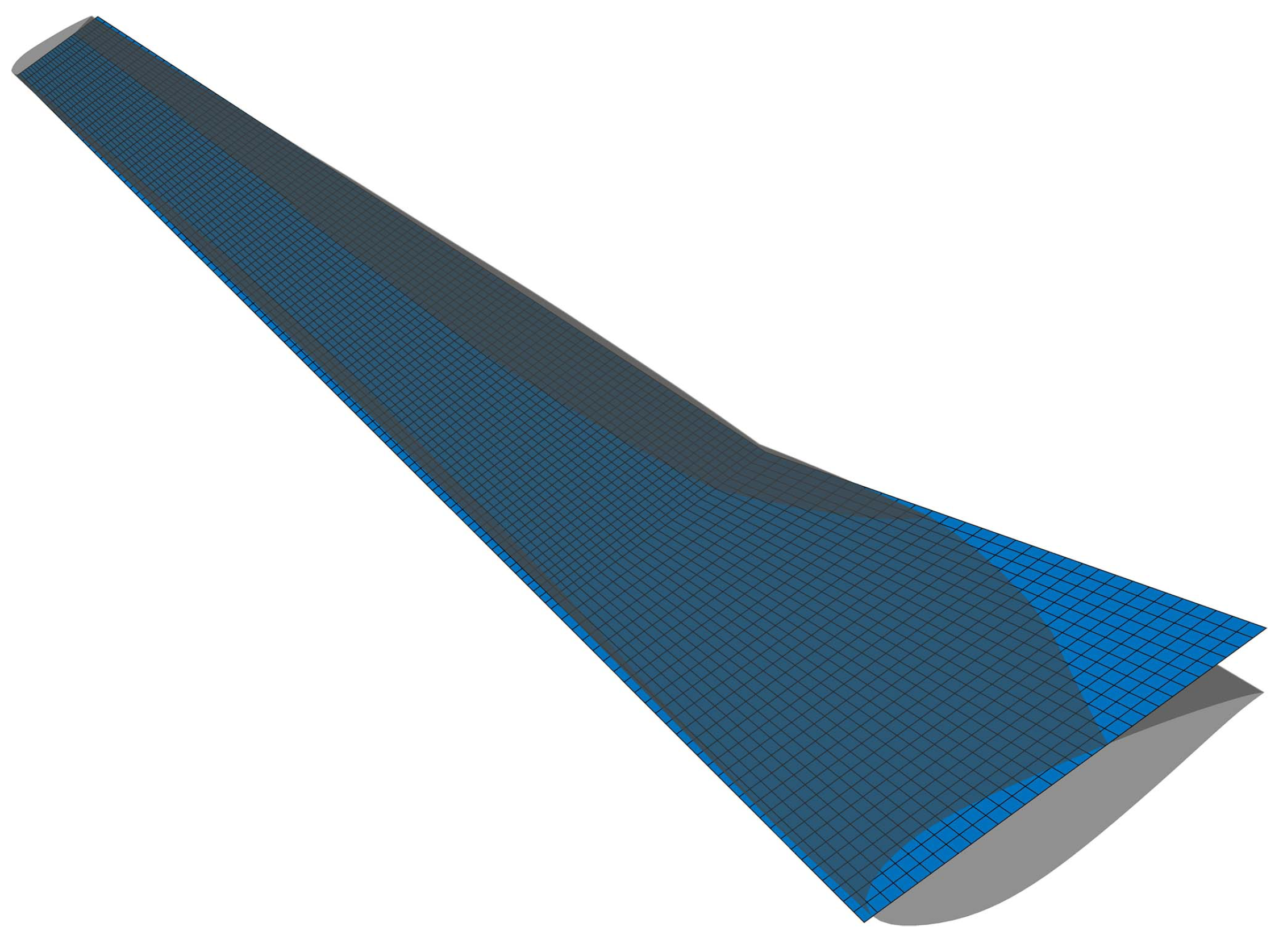

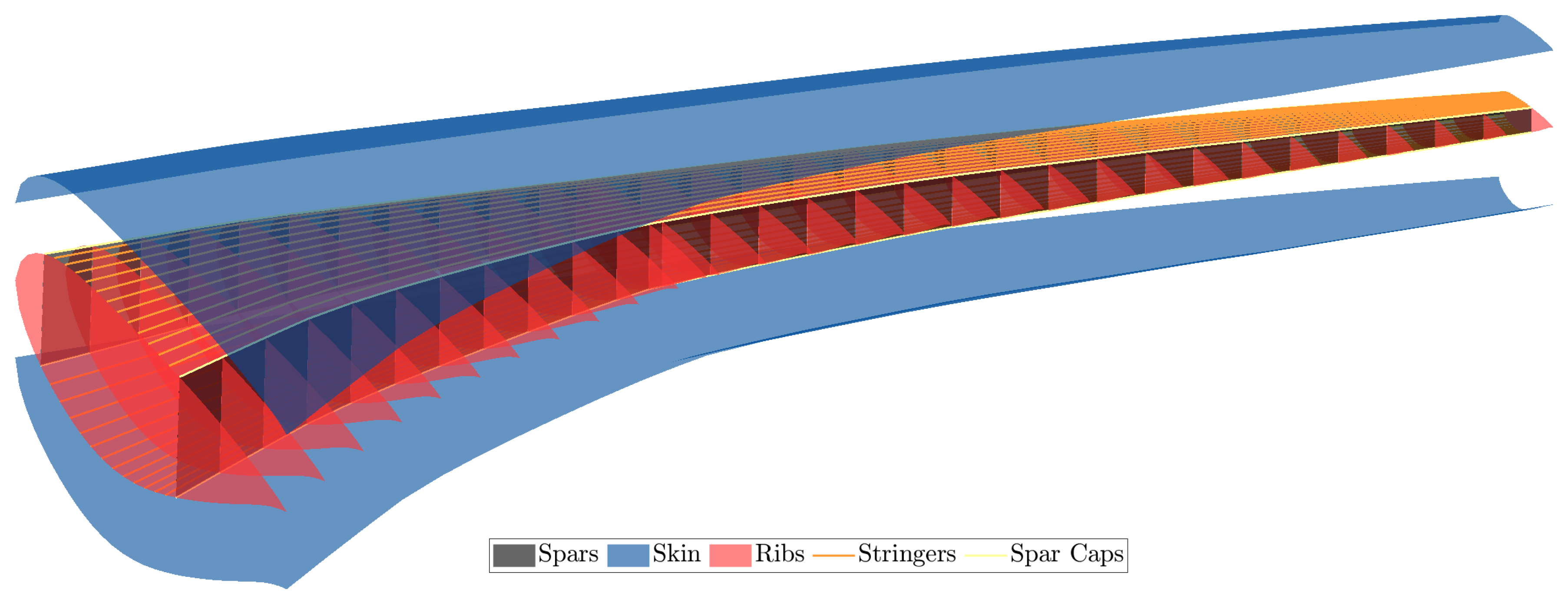

Figure 18.

uCRM wing OML and internal structure.

Figure 18.

uCRM wing OML and internal structure.

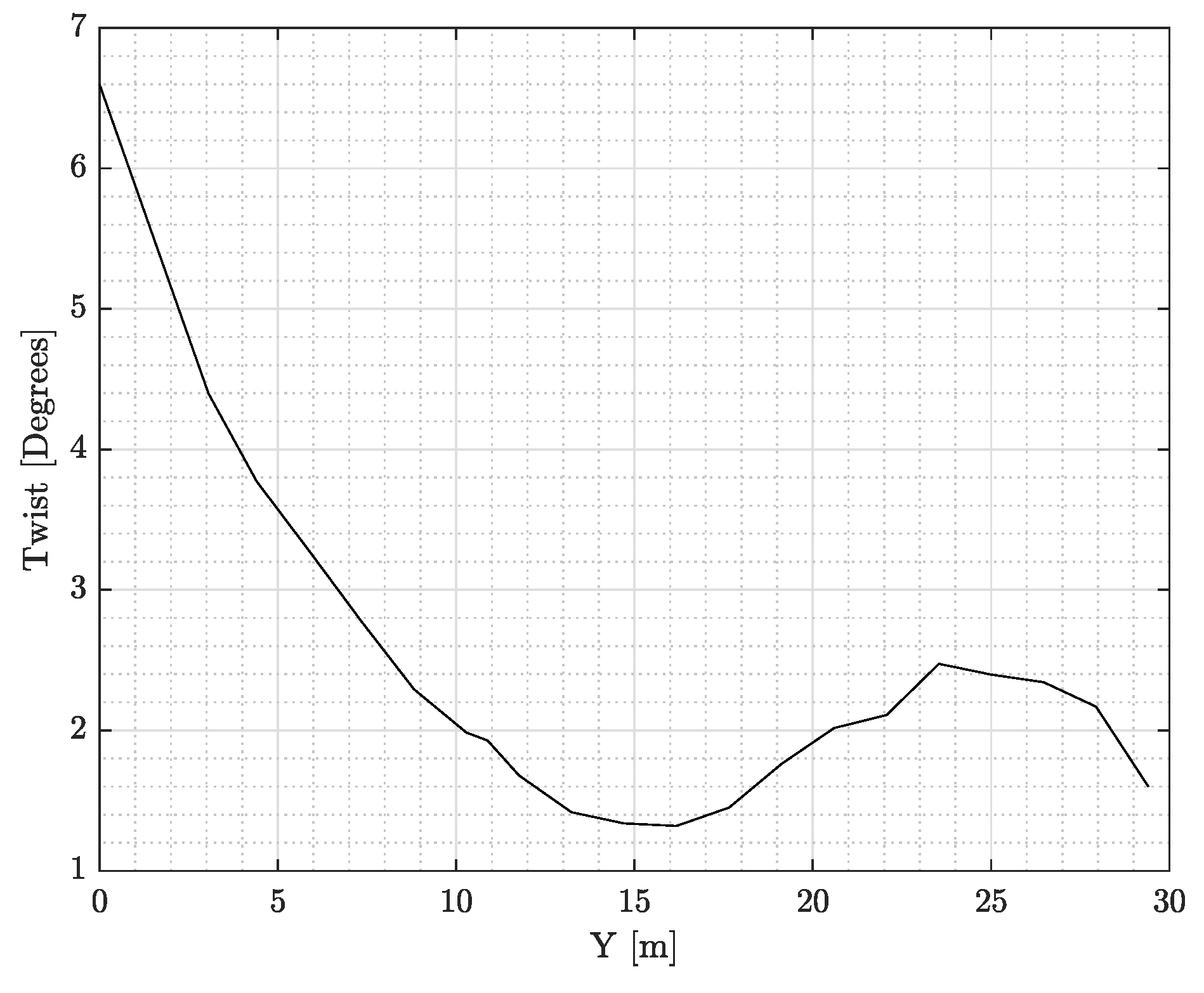

Figure 19.

uCRM wing twist distribution.

Figure 19.

uCRM wing twist distribution.

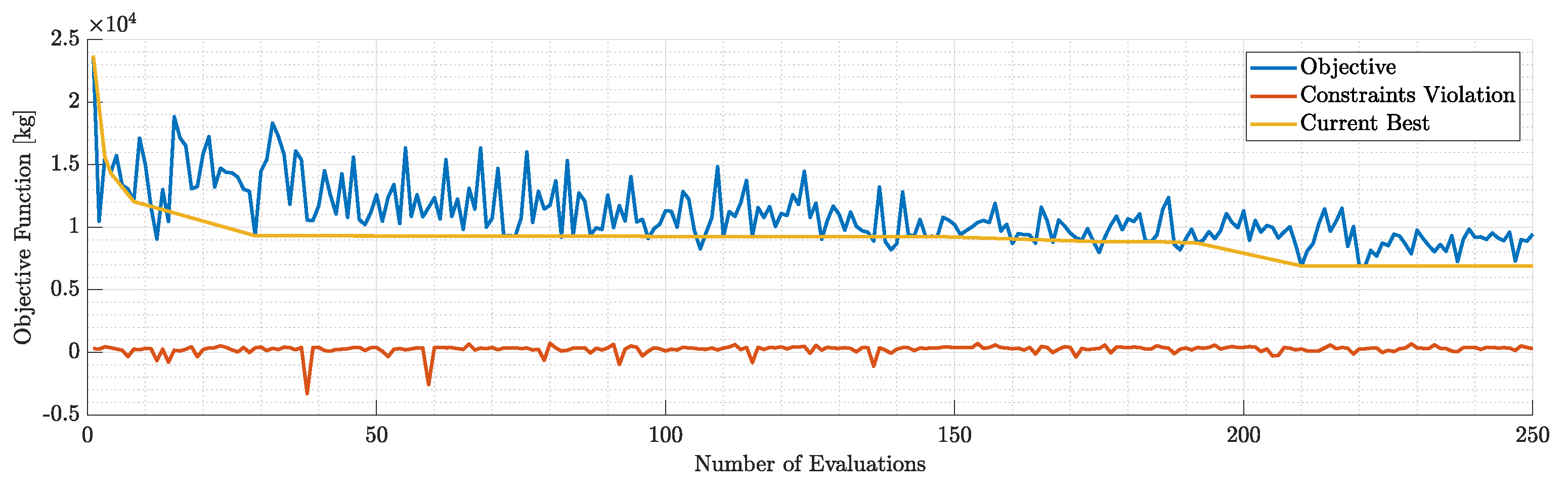

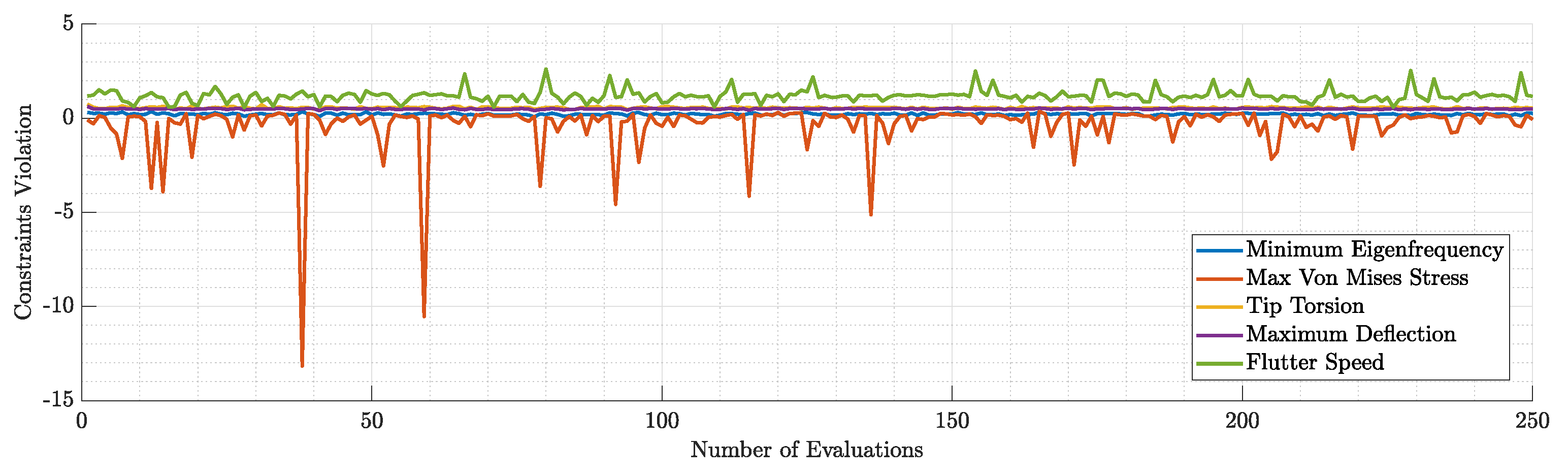

Figure 20.

Objective and constraints violation during the 1st run.

Figure 20.

Objective and constraints violation during the 1st run.

Figure 21.

Violation of each constraint during the 1st run.

Figure 21.

Violation of each constraint during the 1st run.

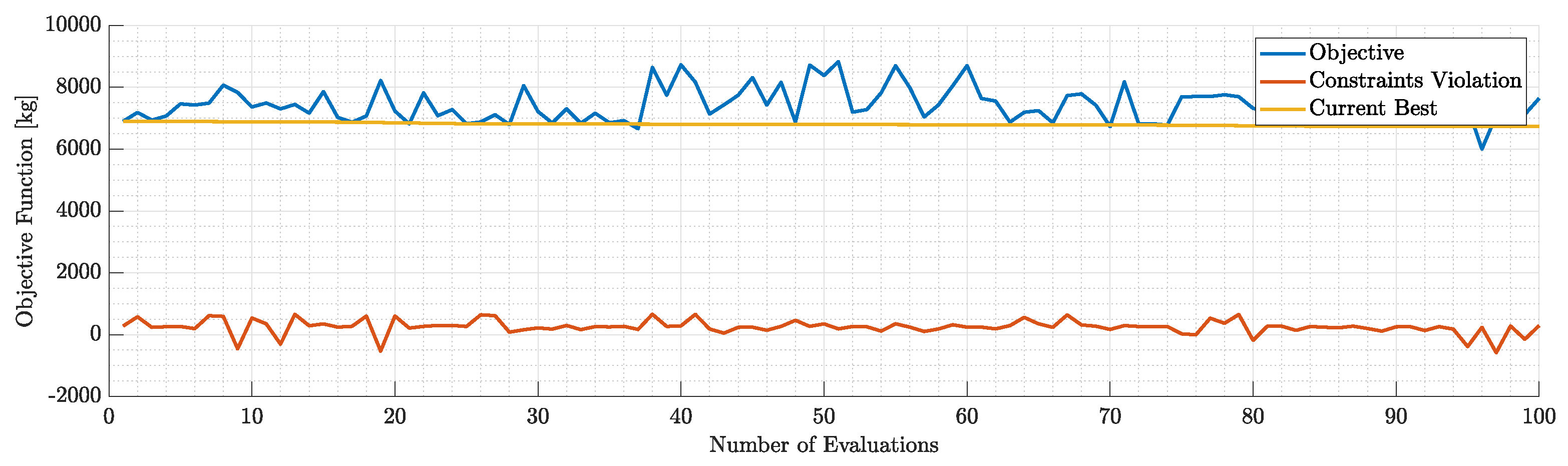

Figure 22.

Objective and constraints violation during the 2nd run.

Figure 22.

Objective and constraints violation during the 2nd run.

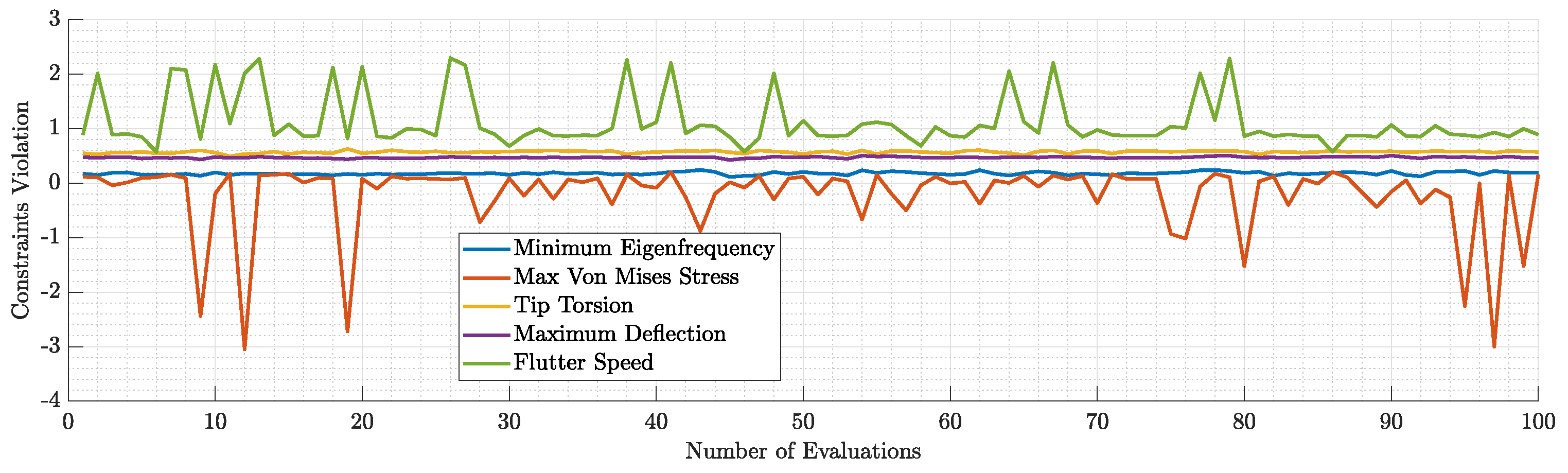

Figure 23.

Violation of each constraint during the 2nd run.

Figure 23.

Violation of each constraint during the 2nd run.

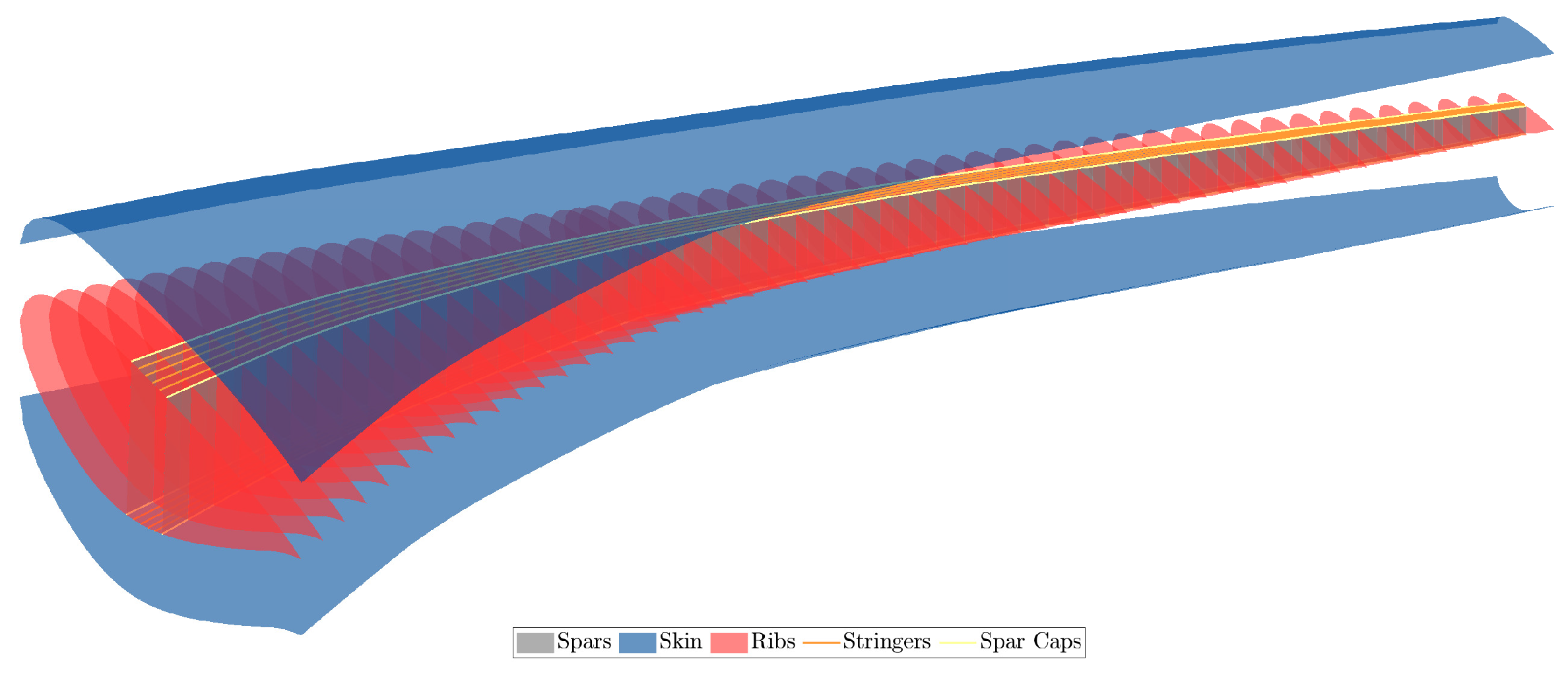

Figure 24.

3D view of the optimized geometry.

Figure 24.

3D view of the optimized geometry.

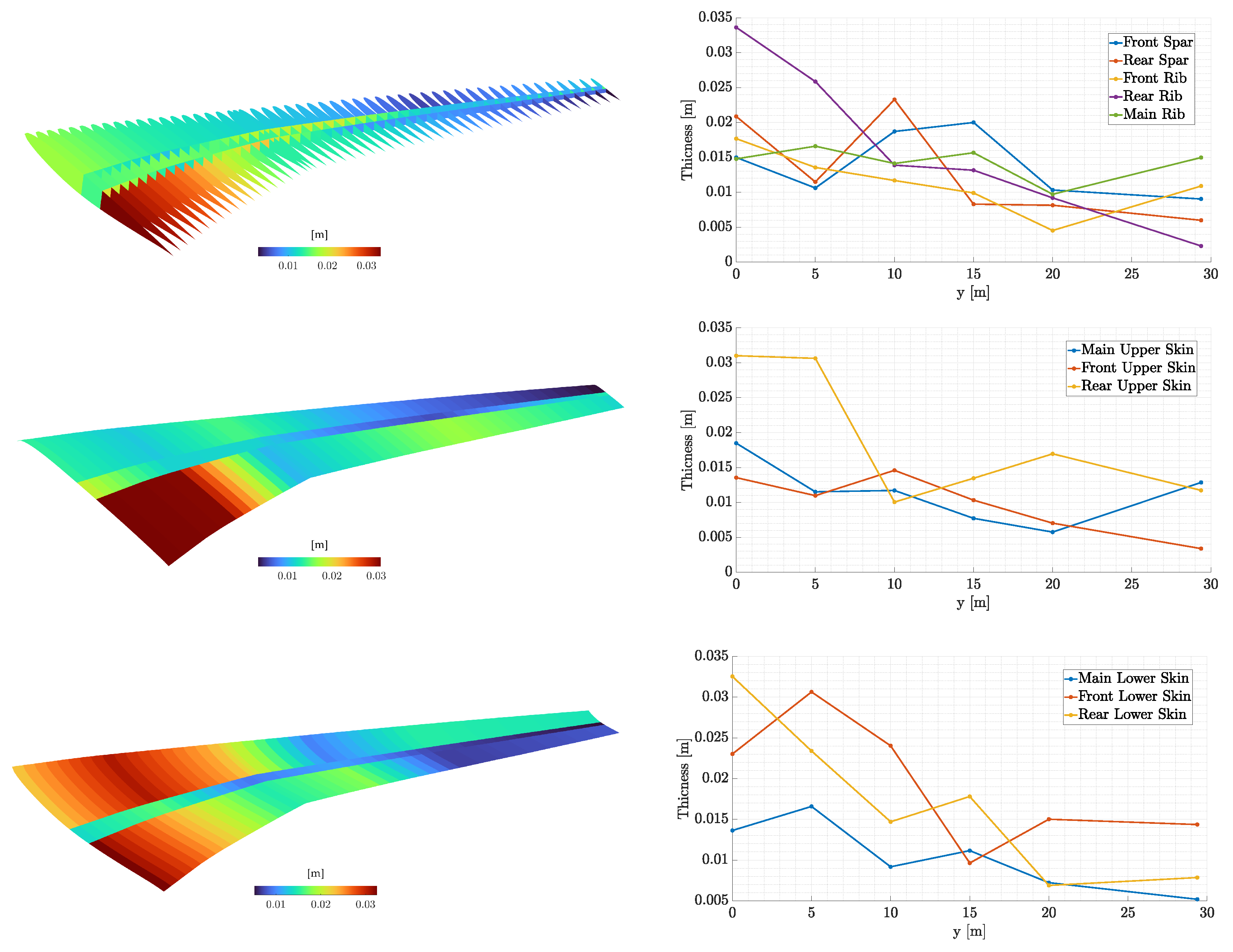

Figure 25.

Optimized thickness distribution of the internal geometry, upper and lower skins along with the corresponding control point values.

Figure 25.

Optimized thickness distribution of the internal geometry, upper and lower skins along with the corresponding control point values.

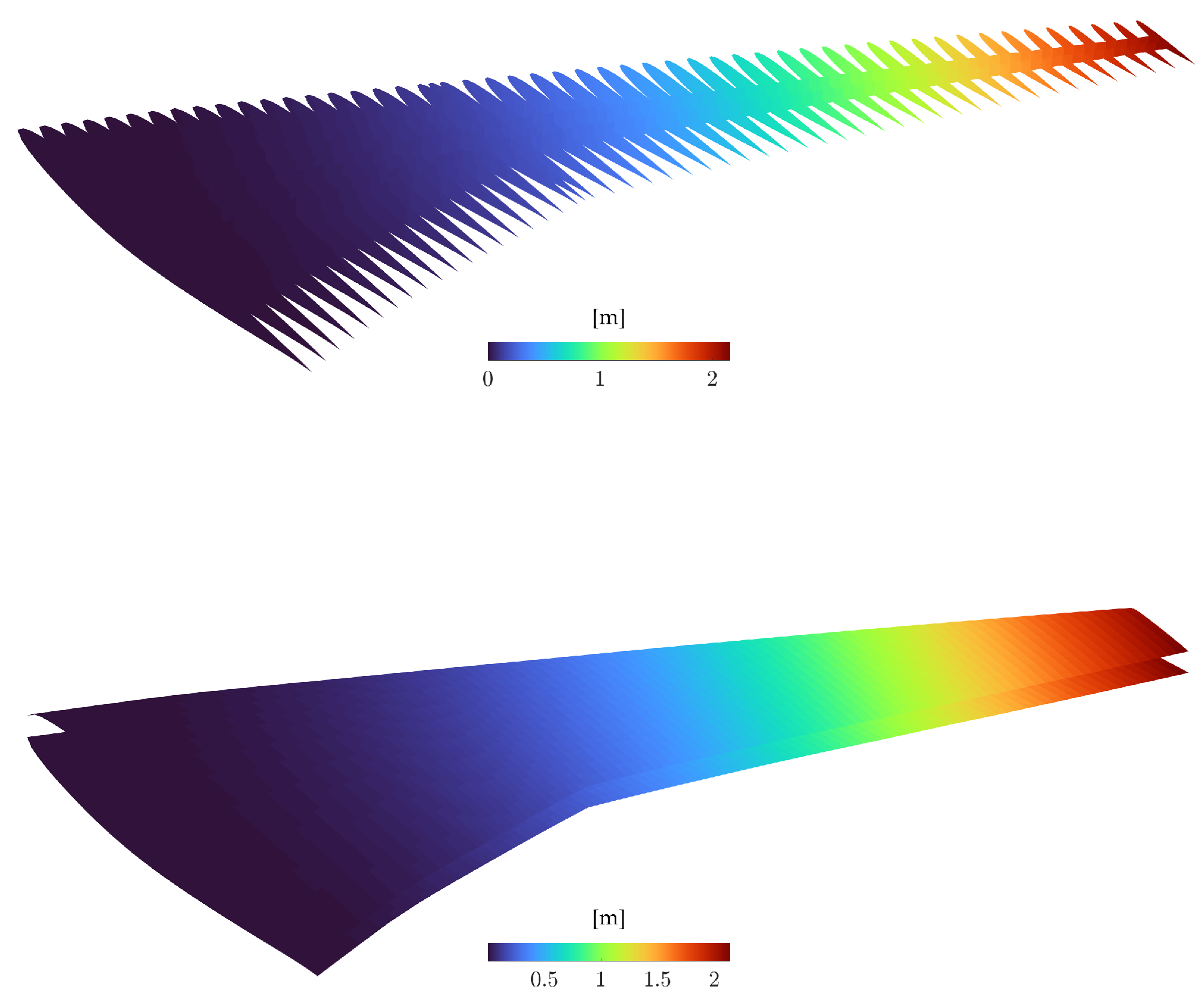

Figure 26.

Displacement distribution of the uCRM wing.

Figure 26.

Displacement distribution of the uCRM wing.

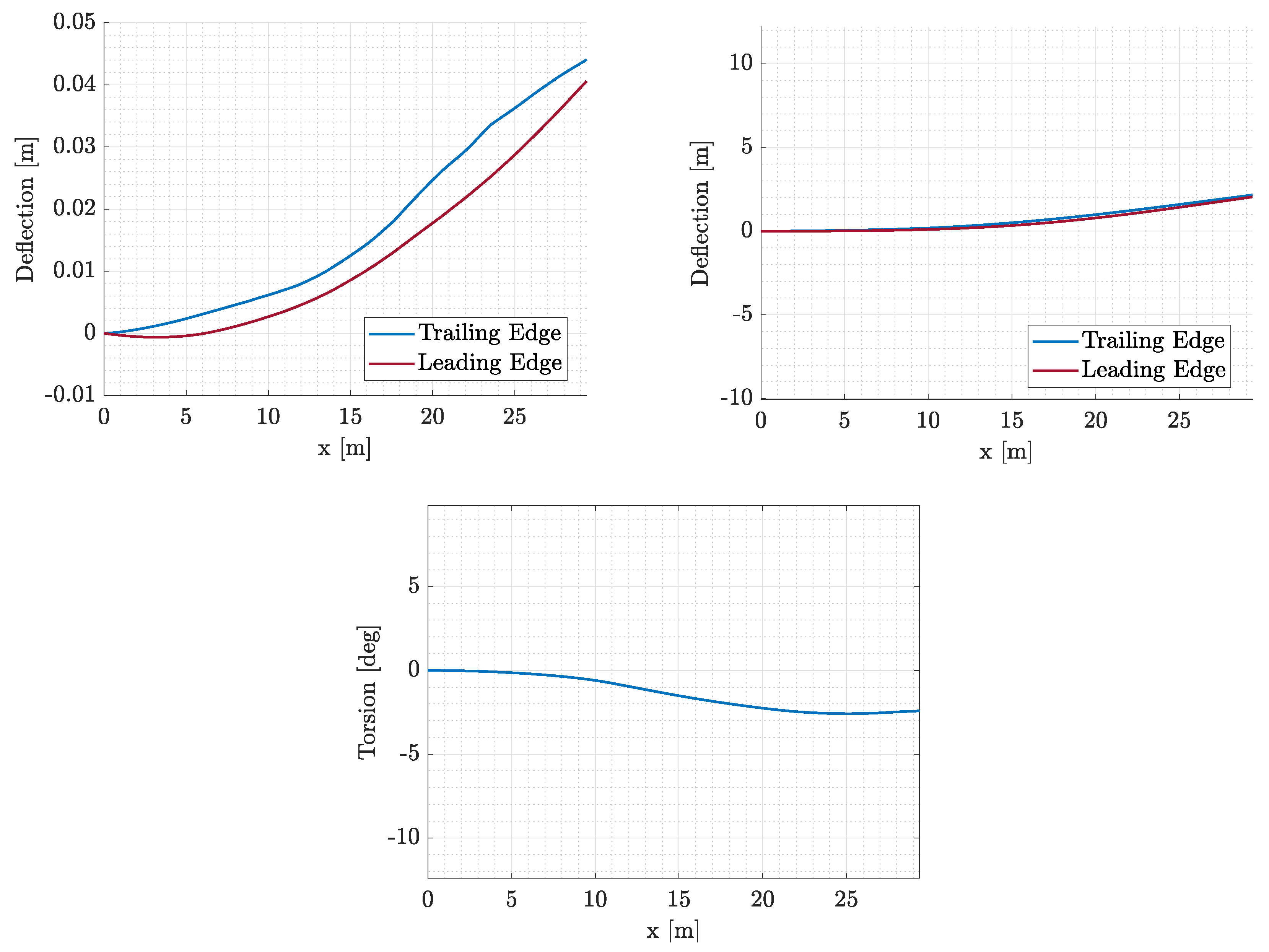

Figure 27.

Wing static aeroelastic displacements.

Figure 27.

Wing static aeroelastic displacements.

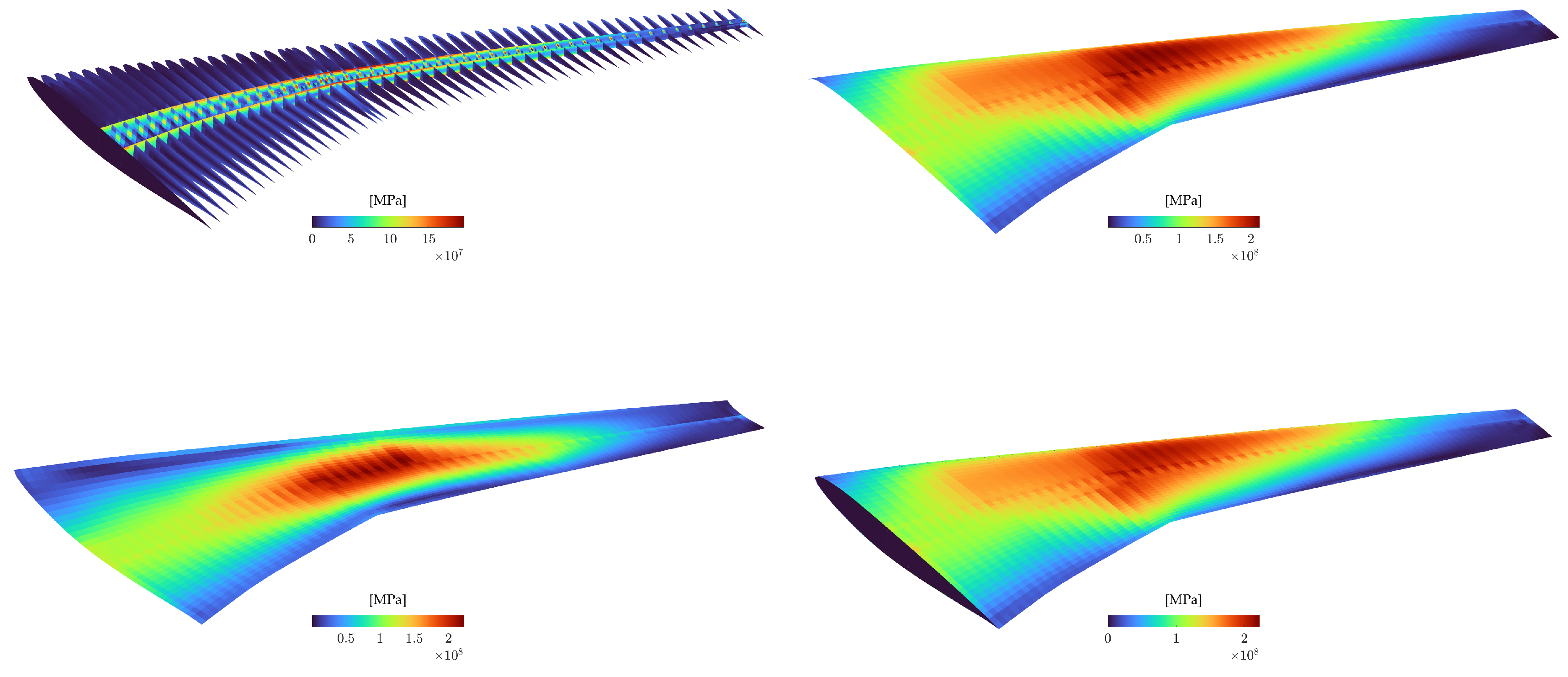

Figure 28.

Von Mises stress distribution of the uCRM wing.

Figure 28.

Von Mises stress distribution of the uCRM wing.

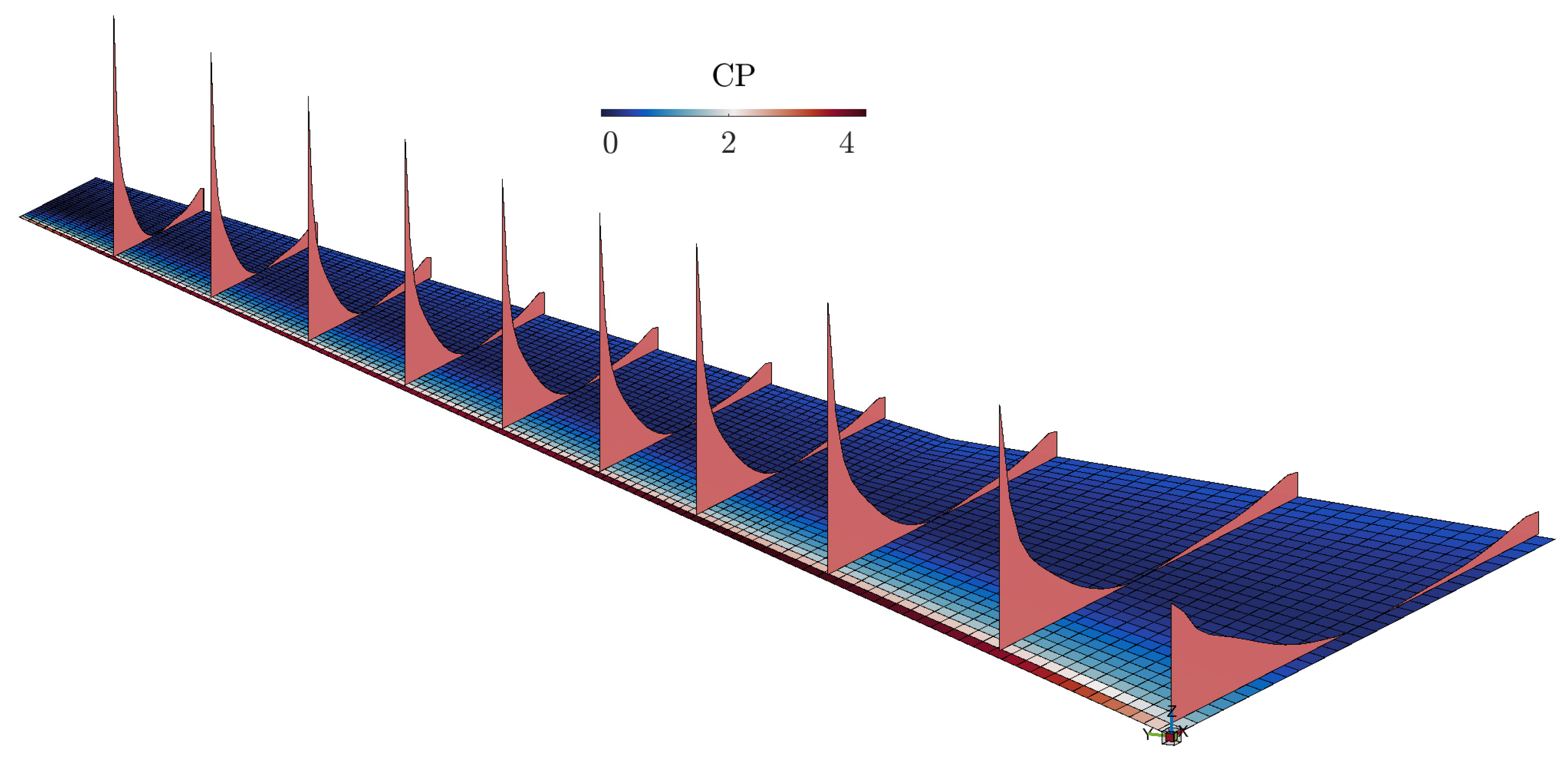

Figure 29.

Coefficient of pressure distribution.

Figure 29.

Coefficient of pressure distribution.

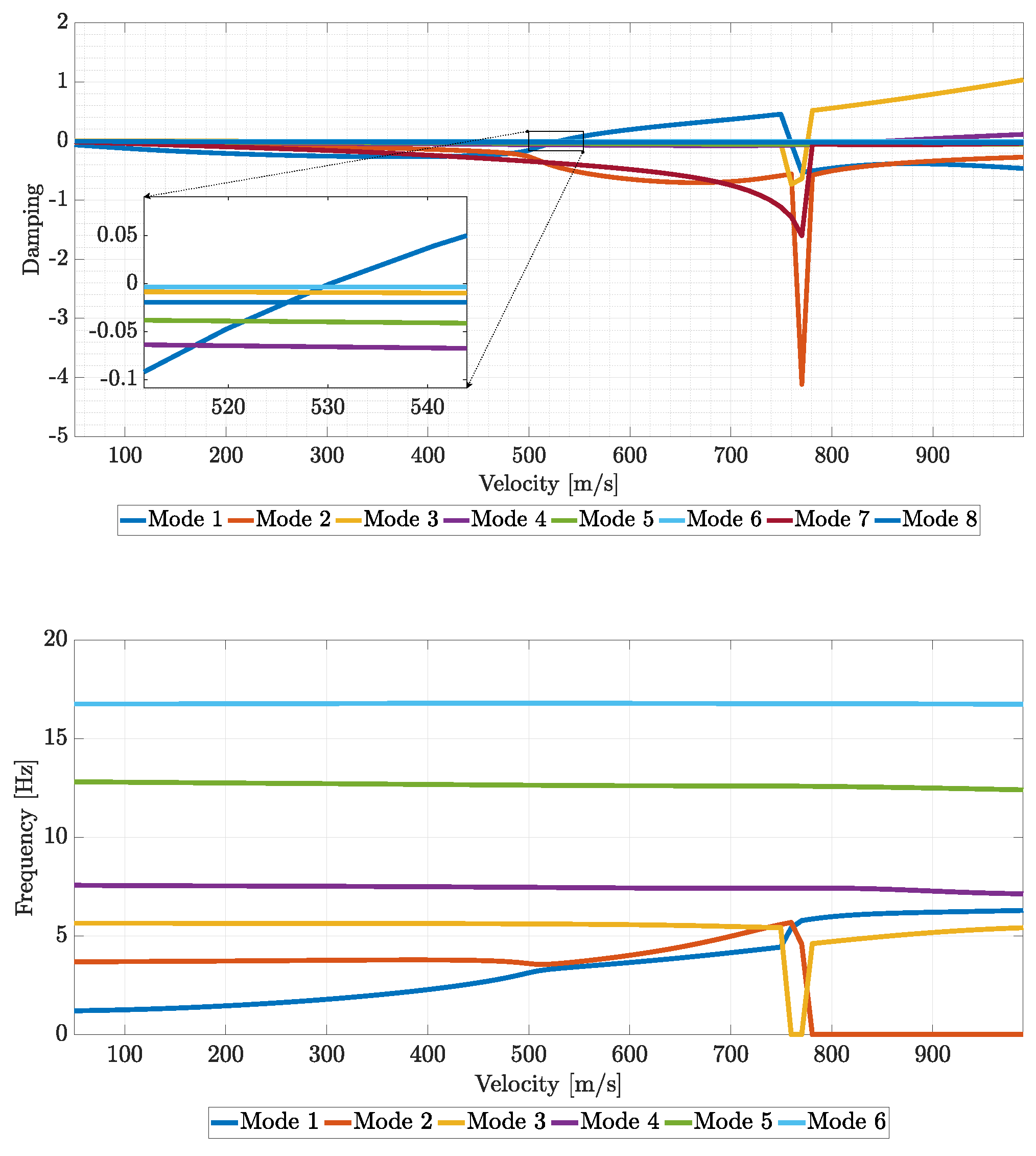

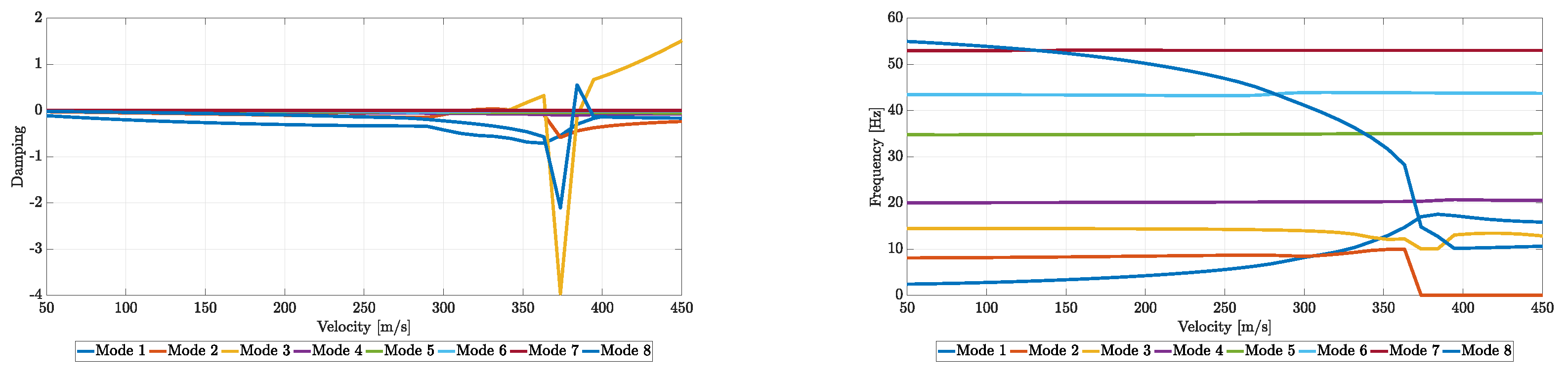

Figure 30.

V-g and V-f plots.

Figure 30.

V-g and V-f plots.

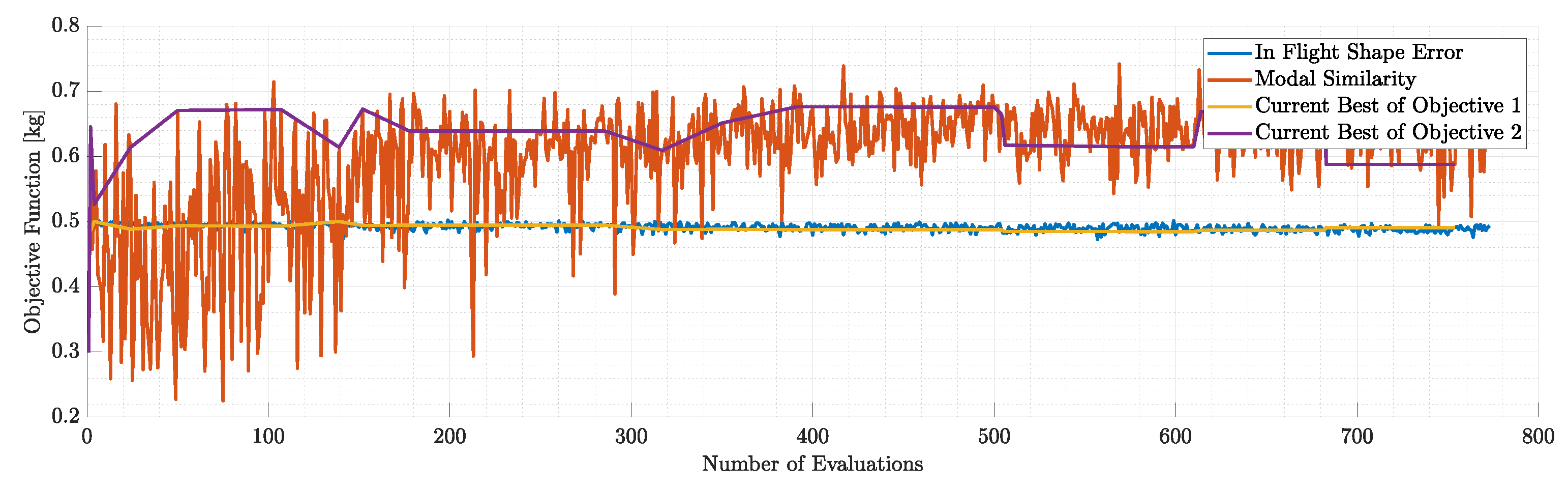

Figure 32.

Objectives during the parallel optimization run.

Figure 32.

Objectives during the parallel optimization run.

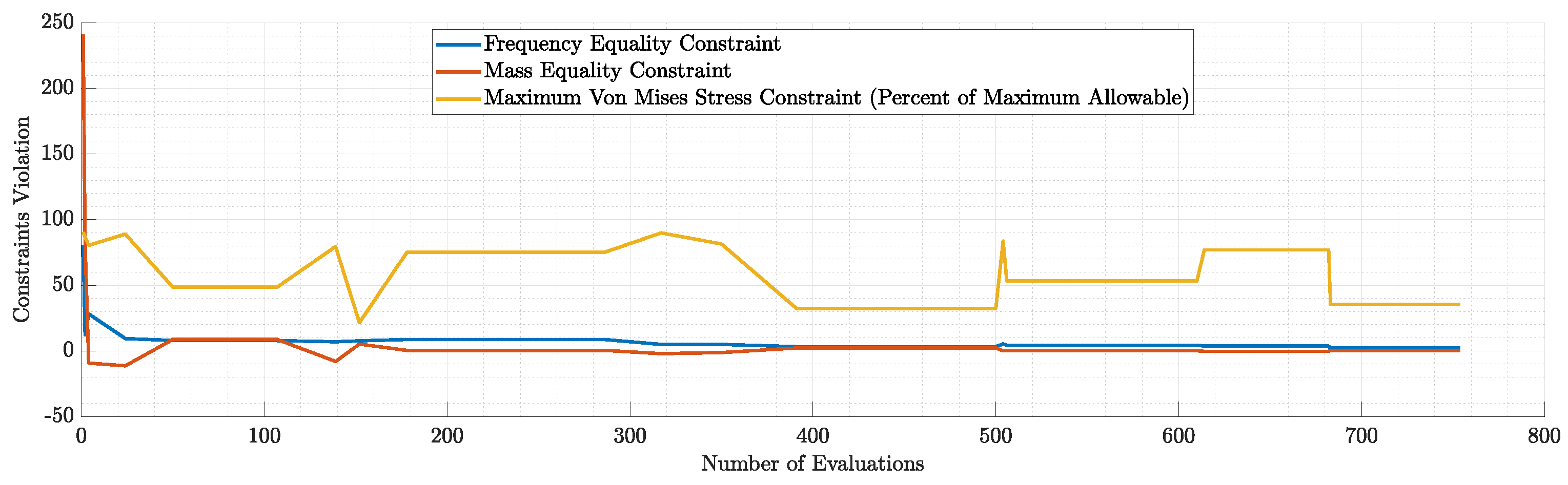

Figure 33.

Violation of each constraint during the parallel optimization run.

Figure 33.

Violation of each constraint during the parallel optimization run.

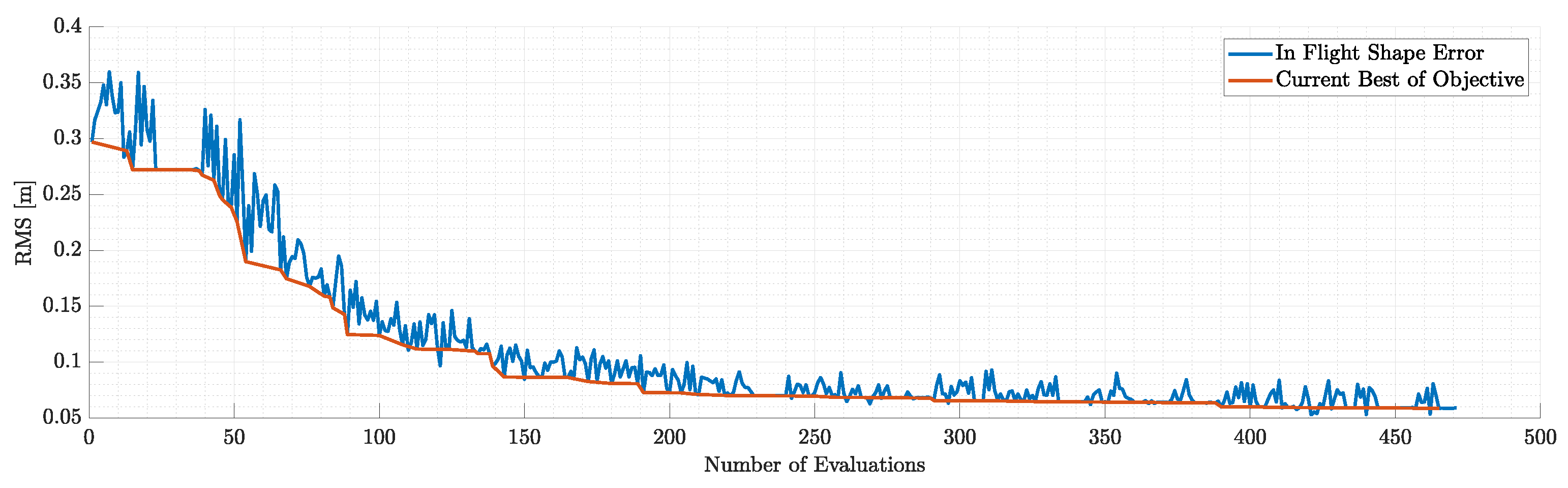

Figure 34.

Objectives during 1st run of static aeroelastic response similarity optimization.

Figure 34.

Objectives during 1st run of static aeroelastic response similarity optimization.

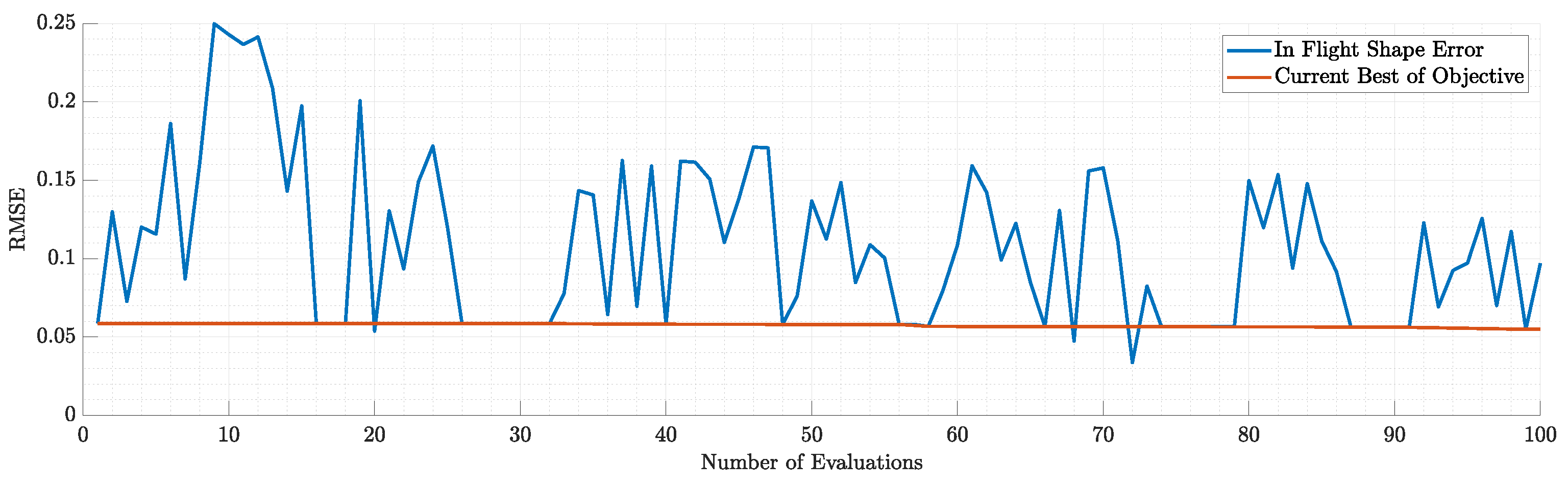

Figure 35.

Objectives during 2nd run of static aeroelastic response similarity optimization.

Figure 35.

Objectives during 2nd run of static aeroelastic response similarity optimization.

Figure 36.

Optimized thickness distribution of each component and its corresponding control point values for the scaling problem.

Figure 36.

Optimized thickness distribution of each component and its corresponding control point values for the scaling problem.

Figure 37.

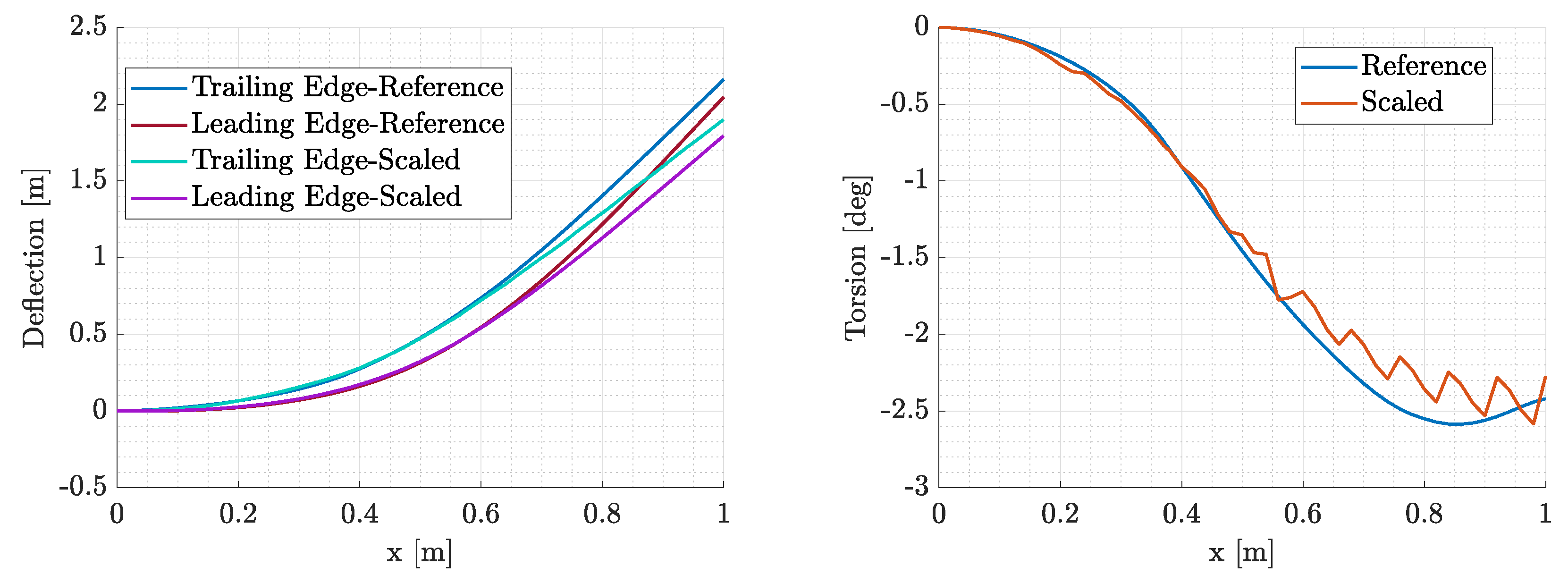

In-flight aerodynamic surface of the optimized design compared to the target shape.

Figure 37.

In-flight aerodynamic surface of the optimized design compared to the target shape.

Figure 38.

Comparison of the scaled and reference wing.

Figure 38.

Comparison of the scaled and reference wing.

Figure 39.

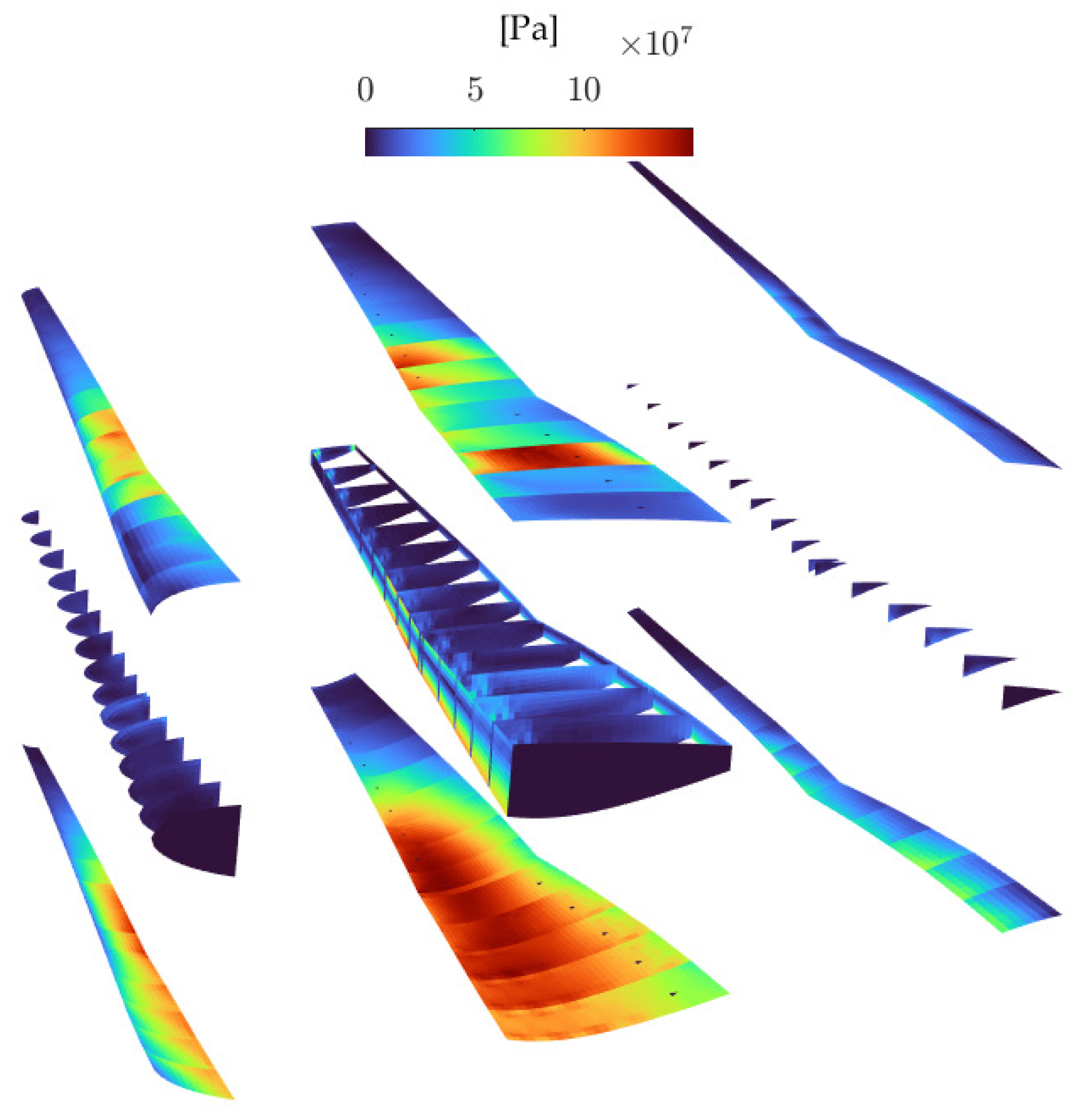

Von Mises stress distribution of the scaled model.

Figure 39.

Von Mises stress distribution of the scaled model.

Figure 40.

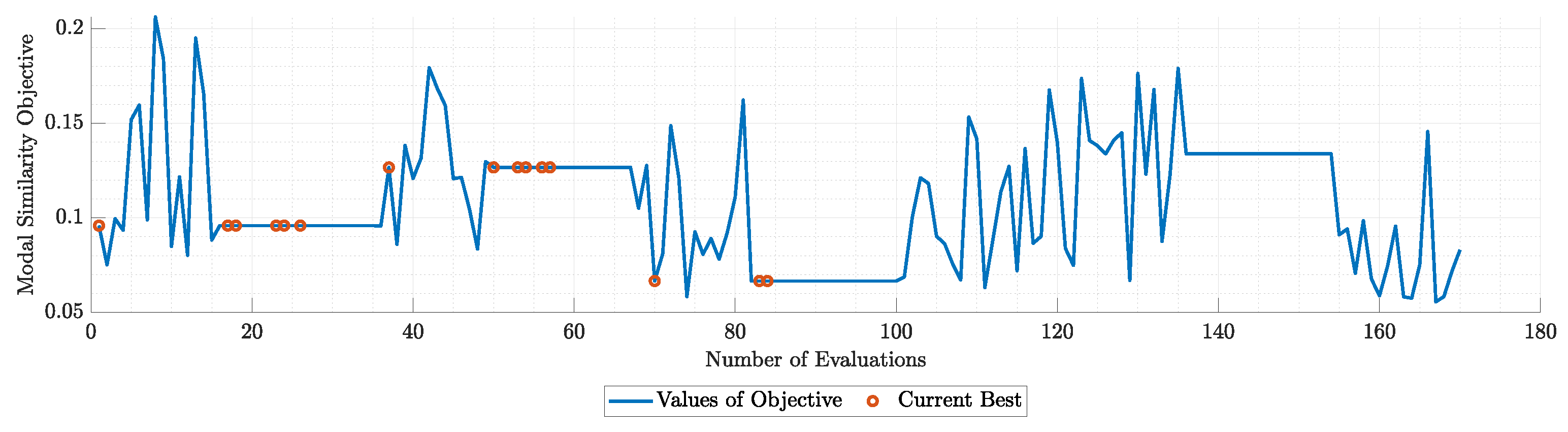

Objectives during the run of modal similarity optimization for N=5 modes.

Figure 40.

Objectives during the run of modal similarity optimization for N=5 modes.

Figure 41.

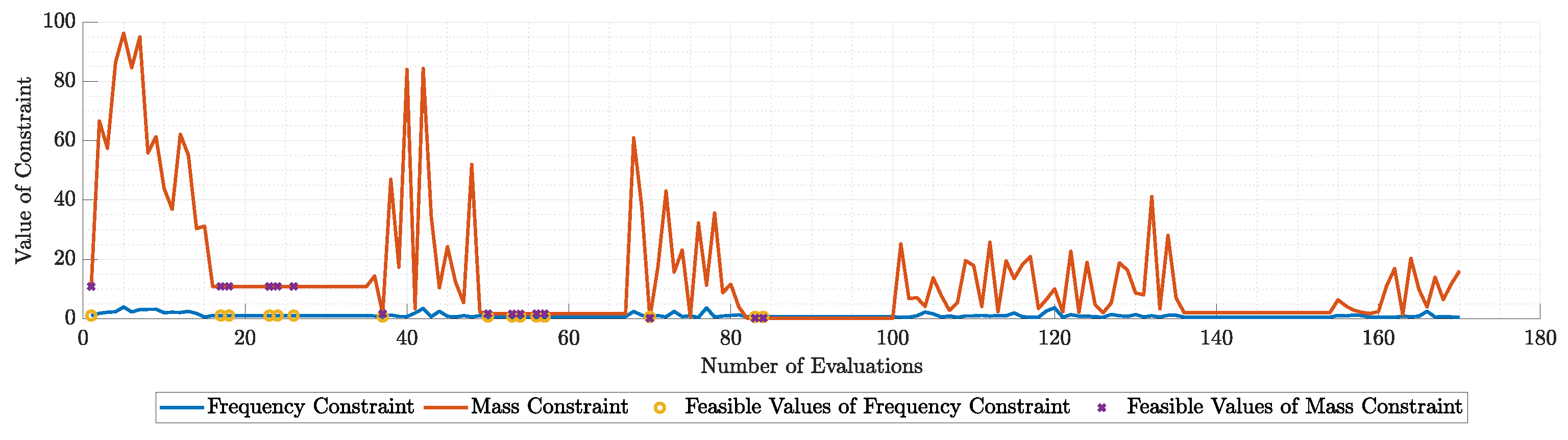

Violation of each constraint during the run of modal similarity optimization for N=5 modes.

Figure 41.

Violation of each constraint during the run of modal similarity optimization for N=5 modes.

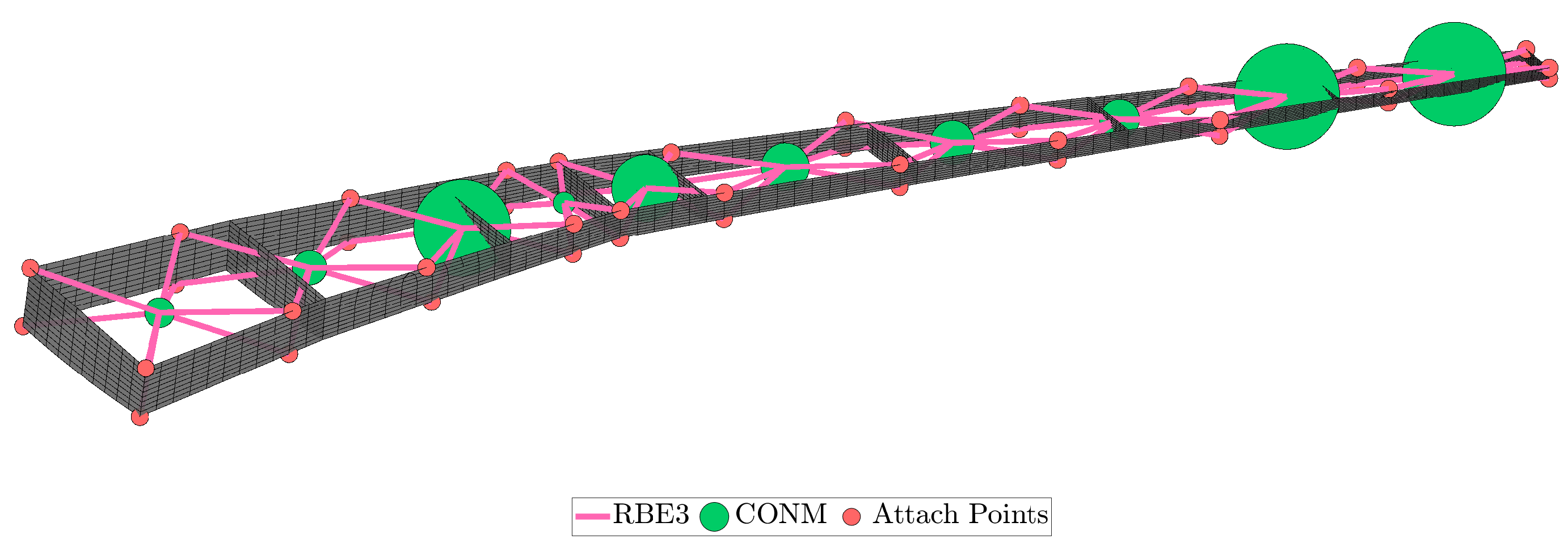

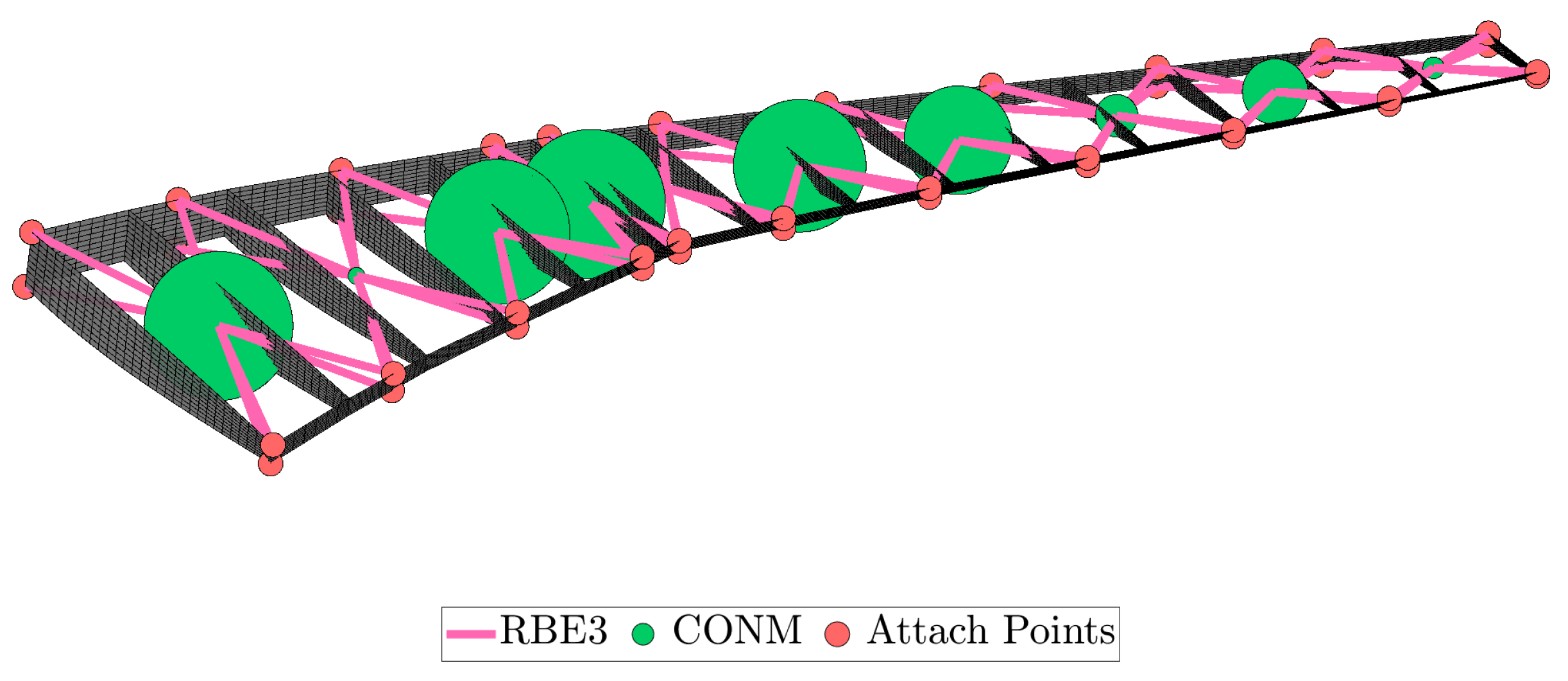

Figure 42.

Optimized lumped masses of the scaled model.

Figure 42.

Optimized lumped masses of the scaled model.

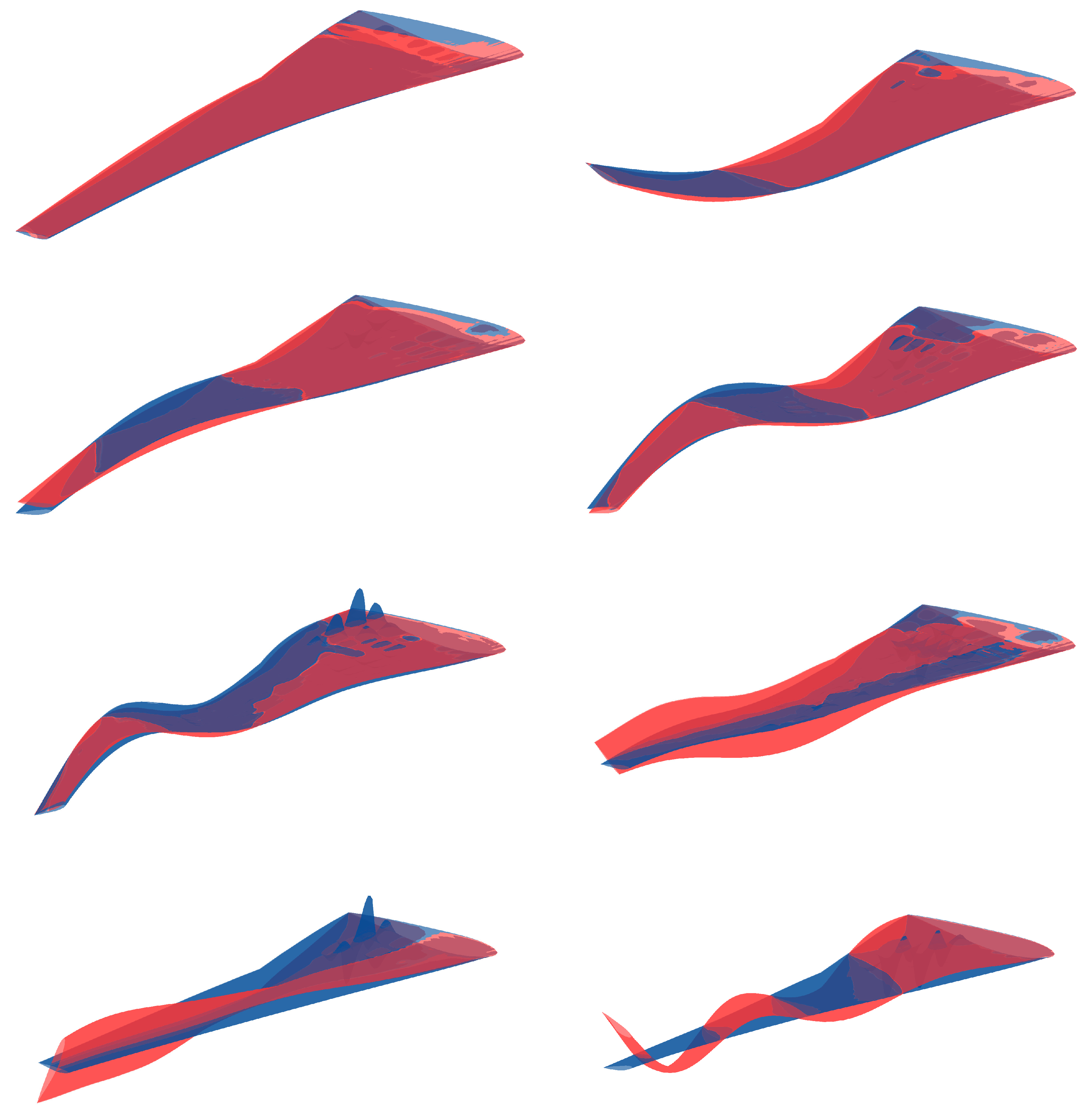

Figure 43.

First eight eigenmodes of the scaled model compared to the modes of the reference wing (red indicates undeformed shape and blue indicates the deformed shape).

Figure 43.

First eight eigenmodes of the scaled model compared to the modes of the reference wing (red indicates undeformed shape and blue indicates the deformed shape).

Figure 44.

Objectives during the run of modal similarity optimization for N=10 modes.

Figure 44.

Objectives during the run of modal similarity optimization for N=10 modes.

Figure 45.

Violation of each constraint during the run of modal similarity optimization for N=10 modes.

Figure 45.

Violation of each constraint during the run of modal similarity optimization for N=10 modes.

Figure 46.

Flutter results of the optimized scaled wing.

Figure 46.

Flutter results of the optimized scaled wing.

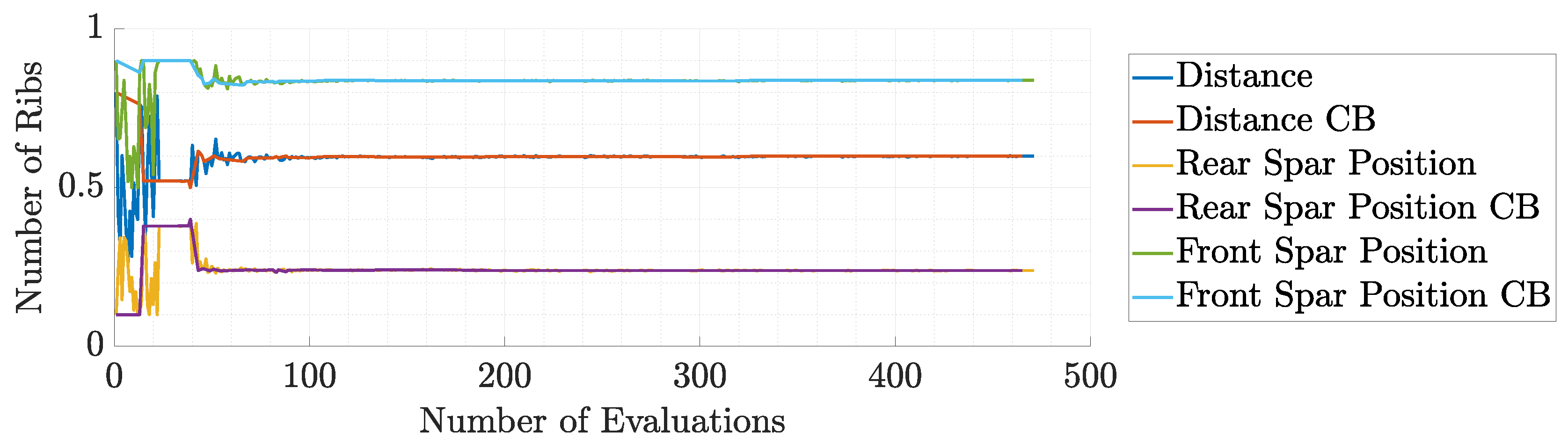

Figure 47.

Spars’ position during the 1st run of static aeroelastic response optimization.

Figure 47.

Spars’ position during the 1st run of static aeroelastic response optimization.

Figure 48.

Number of ribs during the 1st run of static aeroelastic response optimization.

Figure 48.

Number of ribs during the 1st run of static aeroelastic response optimization.

Table 1.

A summary of the features of the publications referenced in this work.

Table 1.

A summary of the features of the publications referenced in this work.

| Author |

Aerodynamic |

Structural |

Optimization |

Thicknesses |

Topology |

| French and Eastep |

DLM |

Beam FEM |

Gradient |

✓ |

✗ |

| Richards et al.

|

Thin Airfoil |

Shell FEM |

Both |

✓ |

✗ |

| Ricciardi et al.

|

VLM |

Shell FEM |

Gradient |

✓ |

✗ |

| Ricciardi et al.

|

VLM |

Shell FEM |

Gradient |

✓ |

✗ |

| Pontillo et al.

|

Strip Theory |

Beam FEM |

Gradient |

✓ |

✗ |

| Spada et al.

|

DLM |

NL Shell FEM |

Gradient |

✓ |

✗ |

| Mas Colomer et al.

|

Panel |

Shell FEM |

Gradient-Free |

✓ |

✗ |

Table 2.

Aluminium’s mechanical properties.

Table 2.

Aluminium’s mechanical properties.

| Quantity |

Value |

Units |

| Density |

2780 |

kg/m3

|

| Young’s modulus |

73.1 |

GPa |

| Poisson ratio |

0.3 |

- |

| Yield strength |

420 |

MPa |

Table 3.

CRM geometric specifications.

Table 3.

CRM geometric specifications.

| Parameter |

uCRM-9 |

Units |

| Aspect Ratio |

9.0 |

- |

| Span |

58.76 |

m |

| Side of body chord |

11.92 |

m |

| Yehudi chord |

7.26 |

m |

| MAC |

7.01 |

m |

| Tip chord |

2.736 |

m |

| Wimpress reference area |

383.78 |

|

| Gross area |

412.10 |

|

| Exposed area |

337.05 |

|

| 1/4 chord sweep |

35 |

deg |

| Taper ratio |

0.275 |

- |

Table 4.

CRM wing critical loading conditions.

Table 4.

CRM wing critical loading conditions.

| Condition |

Lift Constraint |

Mach Number |

Altitude (m) |

| 2.5G Maneuver |

2.5 MTOW |

0.64 |

0 |

Table 5.

Objectives and constraints of the mass minimization problem.

Table 5.

Objectives and constraints of the mass minimization problem.

| Objective |

Target |

| Mass |

Minimization |

| under the constraints |

| Maximum Deflection |

|

| Tip Torsion Angle |

deg |

| First Eigenfrequency |

≥ 1 Hz |

| Maximum Von Mises Stress |

≤ 280 MPa |

| Flutter Speed |

|

Table 6.

Design variables of the optimization problem.

Table 6.

Design variables of the optimization problem.

| Variable |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

Dimension |

| Ribs Number |

6 |

52 |

1 |

| Stringers Number |

4 |

12 |

1 |

| Front Spar Position |

0.1 |

0.4 |

1 |

| Rear Spar Position |

0.5 |

0.9 |

1 |

| Stringer and Spar Cap Thickness |

1 mm |

10 mm |

2 mm |

| Thicknesses at Control Points |

2 mm |

40 mm |

66 mm |

Table 7.

MIDACO parameters.

Table 7.

MIDACO parameters.

| Run |

Iterations |

Accuracy |

FOCUS |

Initial Point |

| 1 |

250 |

0.1 |

0 |

Random |

| 2 |

100 |

0.01 |

10 |

Run 1 |

Table 8.

optimization results summary.

Table 8.

optimization results summary.

| Property |

Value |

| Mass |

6902 kg |

| Minimum Eigenfrequency |

1.1735 Hz |

| Maximum Von Mises Stress |

247.5 MPa |

| Tip Torsion |

2.7 deg |

| Maximum Deflection |

7.89% of span or 2.32 m |

| Flutter Speed |

501 m/s |

Table 9.

Optimized geometric design variables.

Table 9.

Optimized geometric design variables.

| Variable |

Value |

| Ribs Number |

51 |

| Stringers Number |

4 |

| Front Spar Position |

0.3904 |

| Rear Spar Position |

0.5166 |

| Stringer Thickness |

2 mm |

| Spar Cap Thickness |

3 mm |

Table 10.

Objectives and constraints of the scaling problem.

Table 10.

Objectives and constraints of the scaling problem.

| Objective |

Target |

| In-Flight Shape Difference |

Minimization |

| Modal Similarity (MAC) |

Maximization |

Table 11.

Objectives and constraints of the mass minimization problem.

Table 11.

Objectives and constraints of the mass minimization problem.

| Constraint |

Target |

| Frequency Difference |

|

| Overall Mass |

|

| Maximum Von Mises Stress |

|

Table 12.

Target values of frequency for the optimization problem.

Table 12.

Target values of frequency for the optimization problem.

| Mode Number |

Reference Wing Frequency, Hz |

Scaled Wing Frequency, Hz |

| 1 |

1.1915 |

2.6642 |

| 2 |

3.7067 |

8.2885 |

| 3 |

5.6416 |

12.6151 |

| 4th |

7.58 Hz |

16.9494 |

| 5th |

12.8288 |

28.6861 |

| 6th |

16.7503 |

37.4548 |

| 7th |

17.9140 |

40.0570 |

| 8th |

19.4901 |

43.5812 |

Table 14.

Magnesium’s mechanical properties.

Table 14.

Magnesium’s mechanical properties.

| Quantity |

Value |

Units |

| Density |

1800 |

|

| Young’s modulus |

45 |

|

| Poisson ratio |

0.35 |

- |

| Yield strength |

150 |

|

Table 15.

MIDACO parameters of the static aeroelastic response similarity optimization.

Table 15.

MIDACO parameters of the static aeroelastic response similarity optimization.

| Run |

Iterations |

Accuracy |

FOCUS |

Initial Point |

| 1 |

500 |

0.1 |

0 |

Random |

| 2 |

100 |

0.01 |

10 |

Run 1 |

Table 16.

Optimized geometric design variables.

Table 16.

Optimized geometric design variables.

| Variable |

Value |

| Ribs Number |

15 |

| Stringers Number |

5 |

| Front Spar Position |

0.239 |

| Rear Spar Position |

0.839 |

Table 17.

Optimized mass values for the modal response similarity optimization problem.

Table 17.

Optimized mass values for the modal response similarity optimization problem.

| Mass |

Value [kg] |

| 1 |

79.78 |

| 2 |

9.13 |

| 3 |

77.79 |

| 4 |

79.86 |

| 5 |

0.01 |

| 6 |

71.07 |

| 7 |

58.12 |

| 8 |

22.79 |

| 9 |

35.20 |

| 10 |

11.64 |

Table 18.

Target values of frequency for the optimization problem.

Table 18.

Target values of frequency for the optimization problem.

| Mode Number |

Target |

Optimized |

Error |

| 1 |

|

|

14.63 % |

| 2 |

|

|

2.39 % |

| 3 |

|

|

14.60 % |

| 4 |

|

|

18.84 % |

| 5 |

|

|

21.76 % |