1. Introduction

Greenhouse cultivation is widespread globally, driving the economies of many regions. Presently, China boasts the largest greenhouse cultivation area, with the highest concentration found in southeastern Spain [

1]. The expansion of greenhouse cultivation responds to the need to feed a growing population under economic, environmental, and social criteria.

To achieve sustainable development in intensive greenhouse agriculture, it is crucial to design structures based on the climate of the installation area [

2]. This involves maximizing the utilization of solar energy and reducing energy consumption. An appropriate plastic covering can reduce the annual energy demand by up to 9.8% in cooling and 6.3% in heating [

3]. Other influencing factors to achieve this objective include greenhouse orientation, angle, and roof geometry.

The orientation of the greenhouse’s longitudinal axis influences the amount of intercepted solar radiation. Various studies have shown that a North-South orientation captures more solar radiation throughout the year compared to East-West, a trend generally observed at all northern latitudes, leading to significant differences in energy savings ranging from 2% to 28% as latitude increases [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. During summer in temperate climates and middle latitudes, the interior temperature of an East-West oriented greenhouse is 3°C to 5°C lower than that of a North-South orientation. Additionally, during winter, the total solar radiation gain is greater throughout the day in an East-West orientation, resulting in reduced energy consumption for heating in winter and cooling in summer [

9,

10,

11], with significant savings in cooling expenses of up to 9.28% [

12].

Research results demonstrate that the temperature inside the greenhouse is dependent on the greenhouse covering shape [

6]. The angle and geometry of the cover influence the capture of solar energy and the energy consumption of the greenhouse, to a greater or lesser extent depending on latitude and climatic conditions [

13]. Higher cover angles enable increased solar radiation input during winter, when the sun is low, and decrease it in summer, when the sun is high. In cold climates and northern latitudes, the total solar gain inside the greenhouse increases with the angle of inclination and the surface area of the cover.

Classifying different geometric cover shapes based on the annual amount of captured solar radiation, in decreasing order, includes elliptical, asymmetrical, gable, semicircular, and Gothic forms [

14]. The greenhouse with an asymmetrical cover receives annually between 8.4% -11.3% more solar radiation than the gable greenhouse, while arched and quonset forms receive 1.8% and 11.6% less, respectively [

6,

7]. The Gothic or ogival-shaped cover is the most efficient in capturing solar energy for cold climates and high latitudes [

14]. In warm climates and middle latitudes, the arched shape receives the least annual radiation and would be more appropriate when energy needs are higher due to cooling [

12,

15,

16].

The efficiency in capturing solar radiation varies among different greenhouse cover shapes depending on the season. During winter, greenhouses with arched and asymmetrical covers capture 6.2% and 5.7% more solar radiation, respectively, than the gabled greenhouse. In contrast, during summer, the arched shape receives 1.8% less, while the asymmetrical shape receives 9.7% more solar radiation than the gabled greenhouse [

17]. Therefore, considering this seasonal behavior, in arid climates, a greenhouse should be designed to receive minimal radiation in summer and maximum radiation in winter [

16].

On the other hand, the angle of the greenhouse cover, regardless of its geometric shape, plays a crucial role in its energy efficiency. Recommended angles depend on the latitude and climate of the location. Generally, the optimal angle to increase the amount of captured solar radiation is between 18º and 30º [

14,

18]. Scale experiments in multispan greenhouses with a gabled cover find that the optimal cover angle is 30º [

19]. However, in arid areas like Qatar, a cover inclination of 26.5º is recommended [

16]. While in mid-to-high latitudes, a value of 45º is suggested, measured at the base of the cover [

20], although it should be considered over its entire curved surface [

21]. Other studies show that the overall light transmittance of the greenhouse increases with the angle of the cover up to values of 28° to 32°, beyond which it barely changes, and the accumulation of energy due to solar radiation on the greenhouse floor decreases [

22]. The cover angle is implicitly considered through the ratio, Z, defined as the height of the greenhouse/span width, finding that solar radiation interception increases with increasing Z [

15], compensating for part of the decrease that occurs with increasing latitude.

The energy efficiency of the greenhouse relies on the balance between capturing solar energy and heat losses that occur through the cover and walls, especially when these need to be offset through heating and cooling systems. About 40% of heat losses primarily occur through conduction and convection across the greenhouse’s outer surface [

5,

7]. In cold climates, the larger the cover surface, the more energy is needed to heat the greenhouse interior [

17]. The heating energy consumption of a gabled greenhouse is 8% lower than that of a semicylindrical one [

11] and between 2.6% - 4.2% higher than that of a Gothic-shaped greenhouse [

4]. In temperate climates, the Gothic-shaped cover is more energy-efficient compared to gabled and semicylindrical covers, respectively [

23].

Natural ventilation is the primary cooling system used by most greenhouses in warm climates, with better results achieved by semicircular-shaped greenhouses compared to gabled ones [

12]. Increasing the ventilation ratio results in higher temperature and relative humidity inside the semicircular cover compared to the Gothic shape, with the situation reversing during the summer [

24].

The ratio between the exterior surface of greenhouses and the cultivated soil surface is lower in multispan greenhouses than in single-span ones, reducing heat losses through the walls and heating energy consumption by 4%-10% [

25]. The opposite occurs in warm climates, where cooling needs prevail over heating [

12].

The number of spans and the width of spans influence solar energy gain and energy consumption in the greenhouse. Increasing the span width reduces the amount of solar radiation captured by a single-span greenhouse, by up to 35% in winter and 23.4% in summer [

7]. In multispan greenhouses, decreasing the span width only results in an 8% and 3% reduction in solar radiation entering the greenhouse in winter and summer, respectively. However, the decrease in energy consumption with increasing span width is significant in cold climates, decreasing by 13.4% and 3.5% in single-span and multispan greenhouses, respectively [

17].

The ratio (width/length) of the greenhouse influences its energy efficiency when using the cooling system with evaporative panels. It has been found that when the ratio is 1:3, the interior temperature along the longitudinal axis of the greenhouse is lower than when the ratio is 3:4 [

16].

The angle of the greenhouse cover influences its luminous and thermal performance, especially during winter when the sun is low [

26]. It also plays a role in reducing condensation on the cover, which can cause damage to crops and decrease light transmission through plastic materials [

27,

28]. At the same time, condensation increases diffuse radiation inside the greenhouse [

29], which can favor certain crops and decrease the yield of others, such as microalgae [

30].

The use of plastics containing anti-fog/anti-drip additives as greenhouse cover material improves light transmission but comes with drawbacks of high cost and low durability [

31]. Reducing condensation results in a higher plant growth rate and more abundant crops, which can be achieved with a cover angle that encourages the sliding of condensed water.

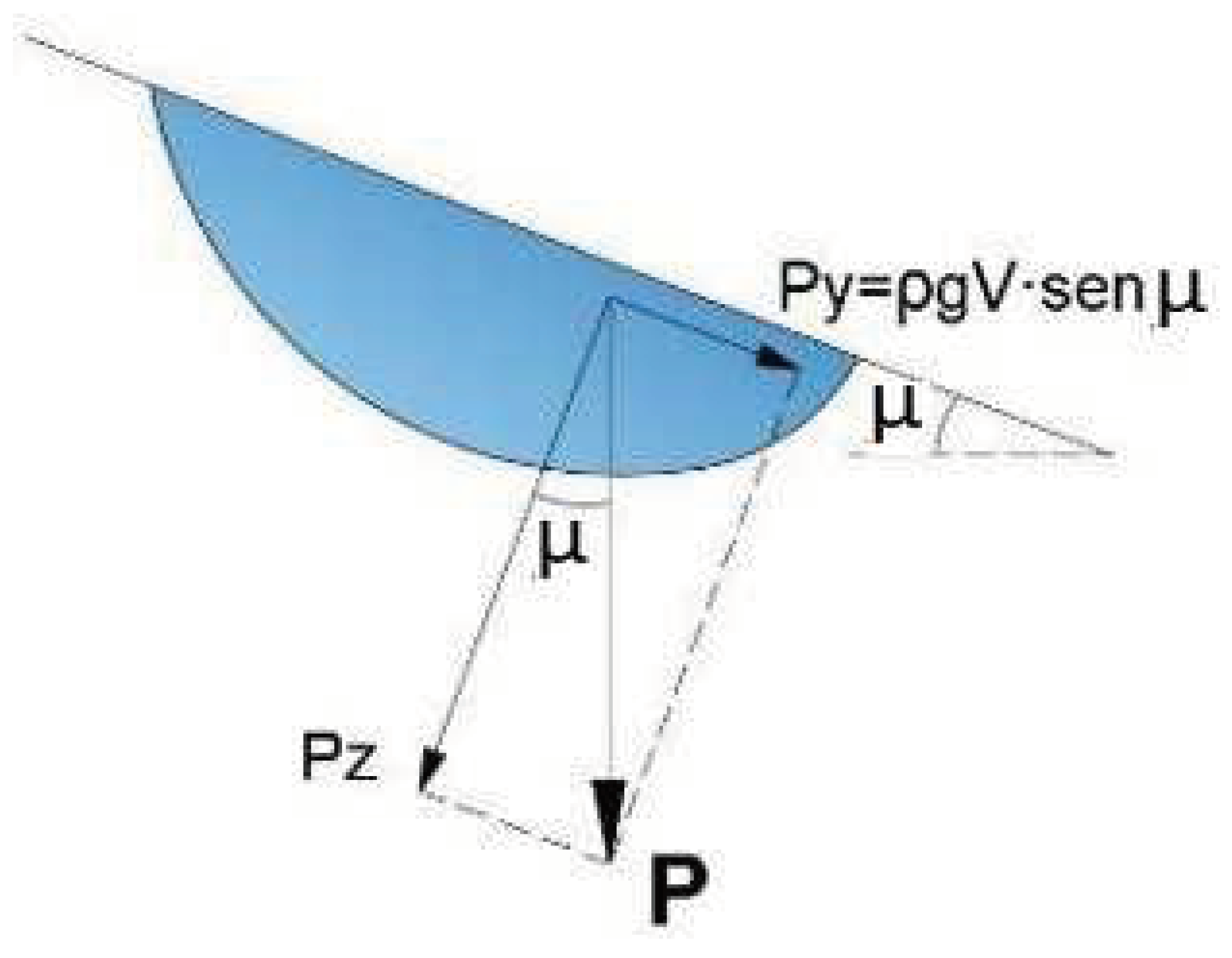

A water droplet begins to slide on a surface when the contact angle exceeds its most stable value (

Figure 1), which is constant and determines the shape of the droplet [

32,

33,

34].

The minimum incline value of a surface, denoted as µ, on which a water droplet adheres and from which it begins to slide, has been determined by various authors through simulation techniques, µ ≥ 30º [

35], or through laboratory experiments, µ > 28º [

36]. Additionally, a surface with a 30º inclination not only promotes droplet sliding but also facilitates water collection by gravity [

37,

38], which is particularly relevant in water-scarce areas.

It is deduced that the inclination required for a water droplet to slide on a polyethylene surface is lower when its volume is larger [

39]. Increasing the inclination reduces the required droplet size to initiate movement [

40], and the maximum radius the droplet reaches when it starts to fall is inversely proportional to the roof’s incline angle [

41]. The minimum water volume value for a sliding droplet is obtained for a vertical surface, µ

c = 90º [

42].

The objetive of this study is to investigate various design parameters influencing the energy efficiency of greenhouses and reducing the amount of water condensing on the roof. We consider only roof shapes suitable for multi-span greenhouses. We have developed a Matlab program that allows us to calculate, for any span width and arch height, the angle and surface for gothic, semicylindrical, and gable roof types, among others. Additionally, we calculate the cultivation surface where dripping occurs, the air volume, and the optimal greenhouse length.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Analysis and evaluation of the roof to reduce dripping due to condensation

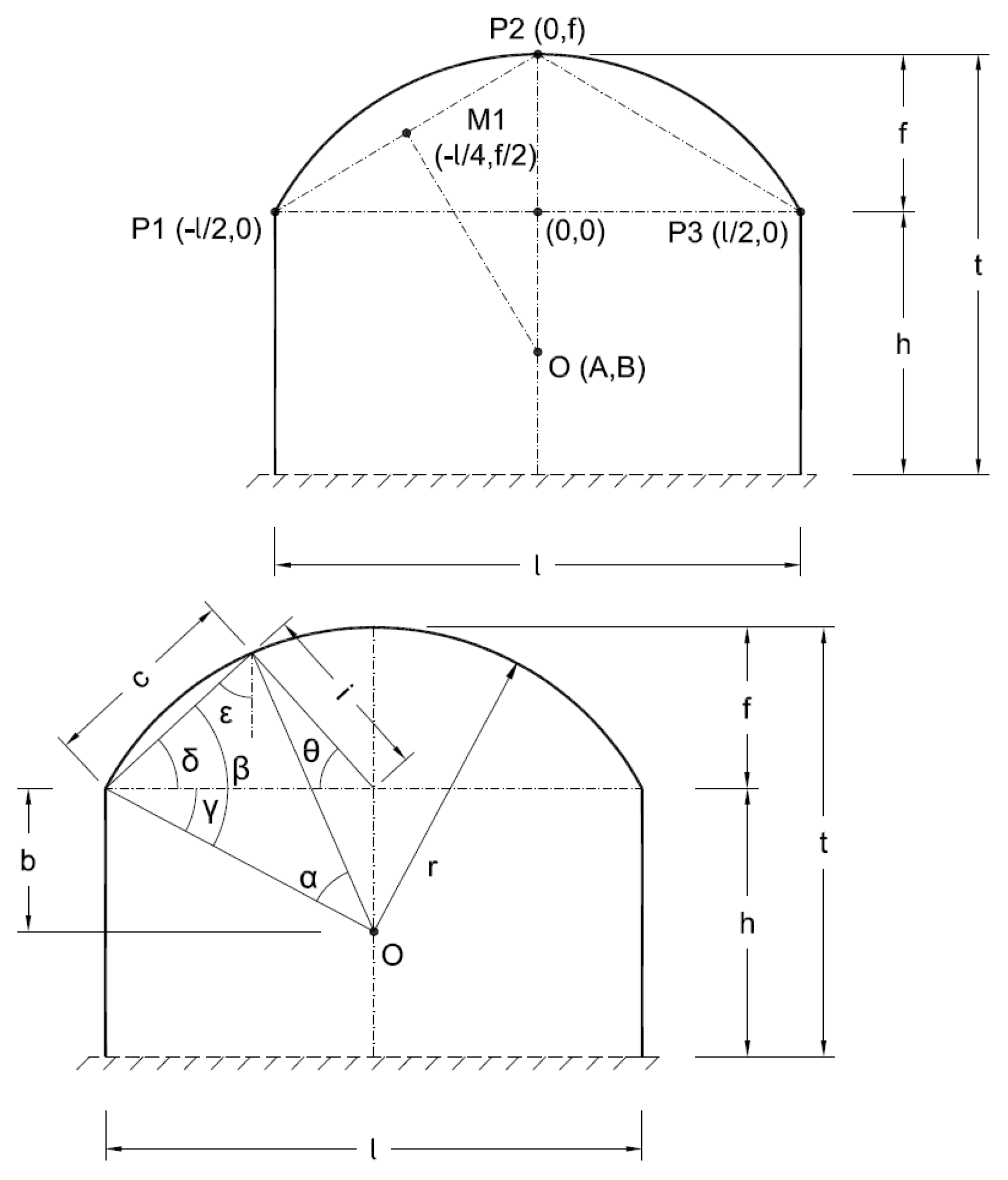

We define the geometric parameters of the roof shapes considered in this study, which are necessary for calculating the ground surface where condensation water drips from the greenhouse roof.

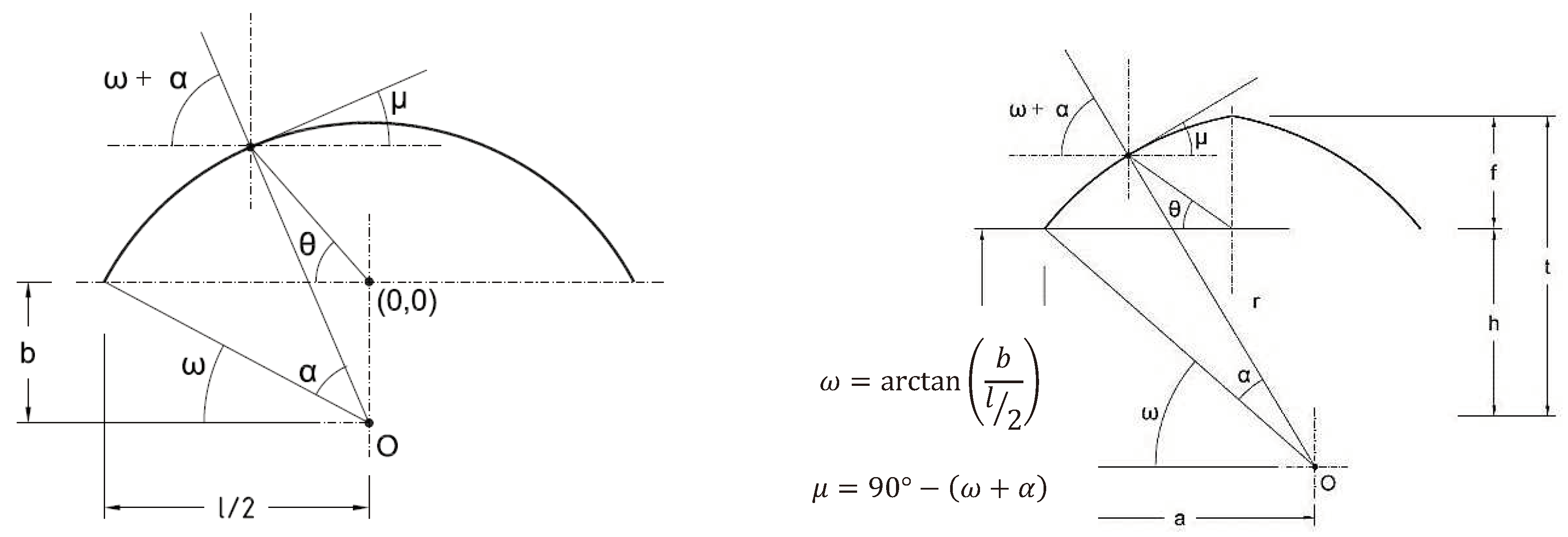

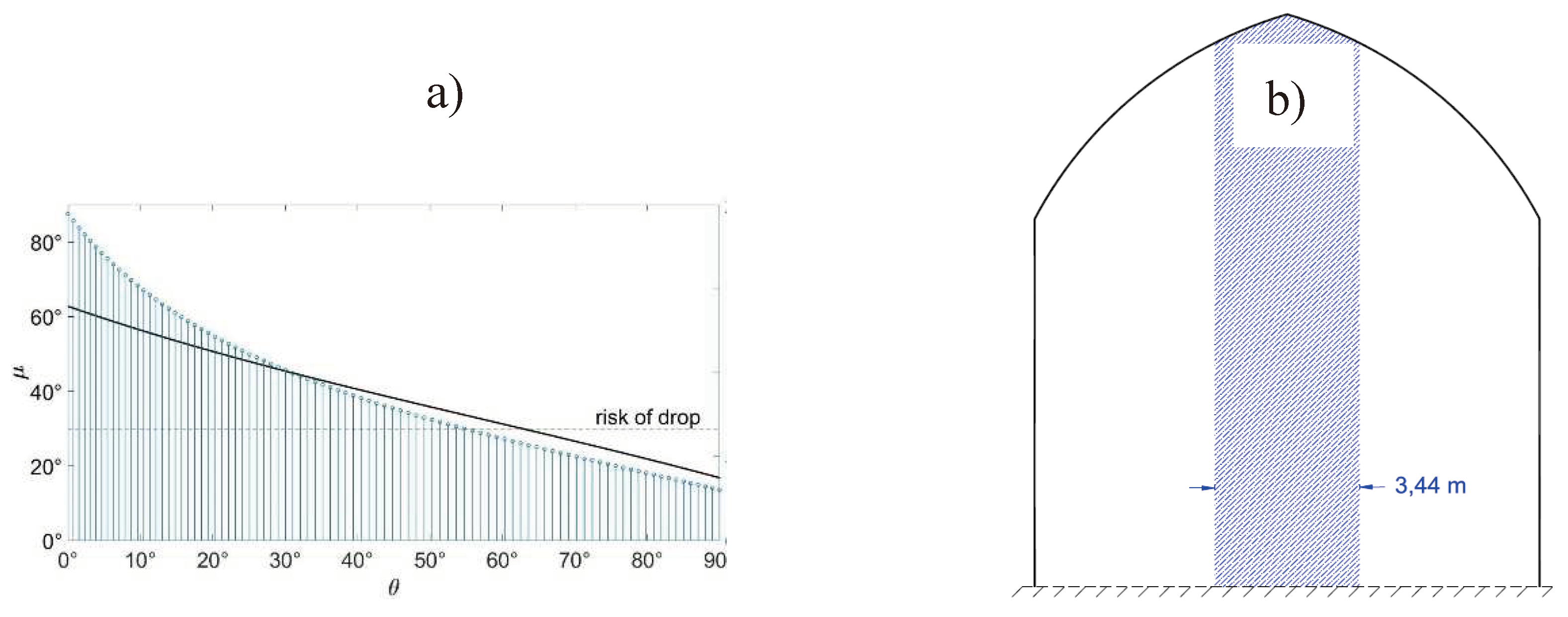

The program calculates the angle at each point of the curve, µ, for both the semicircular and the gothic or ogee geometries (

Figure 4). To do this, it is necessary to know the vertical distance from the center of the arch to the starting point, b, and the span width, l. The position of each point along the length of the arch is defined by its angle (ω+α), where ω is the arc formed by the vertical distance from the center of the arch to the starting point, b, and half of the span width (l/2), and α is the angle from the starting point of the arch to any point on the roof.

For angles, µ, greater than or equal to 30º, it is considered that there is no dripping inside the greenhouse, and moreover, it facilitates water collection at the ends of the roof [

37,

38]. Taking advantage of the symmetry of the roof, we calculate the roof inclination angle, µ, only for half of the arch, as a function of the angle θ that covers the roof and for different span widths (

Figure 5a). Additionally, we also determine the length of the roof with angles less than 30º, which we call "length of roof with precipitation risk,"

lcr, as well as its horizontal projection, which we call "drip length,"

lcs. If dripping occurs, it always happens in the central part of the greenhouse (

Figure 5b). The greatest length of dripping on the ground,

lcs, occurs in the semicircular greenhouses.

Next, we study the geometric evolution of the roof when varying the position of the arches that define it, seeking the one that minimizes the area of the ground on which condensation water can drip. To compare various geometries and generalize for any greenhouse, we have kept the following parameters constant and equal: the number of bays (n), pillar height (h), and bay length (p).

3.2. Analysis of the Semicylindrical Arch Roof

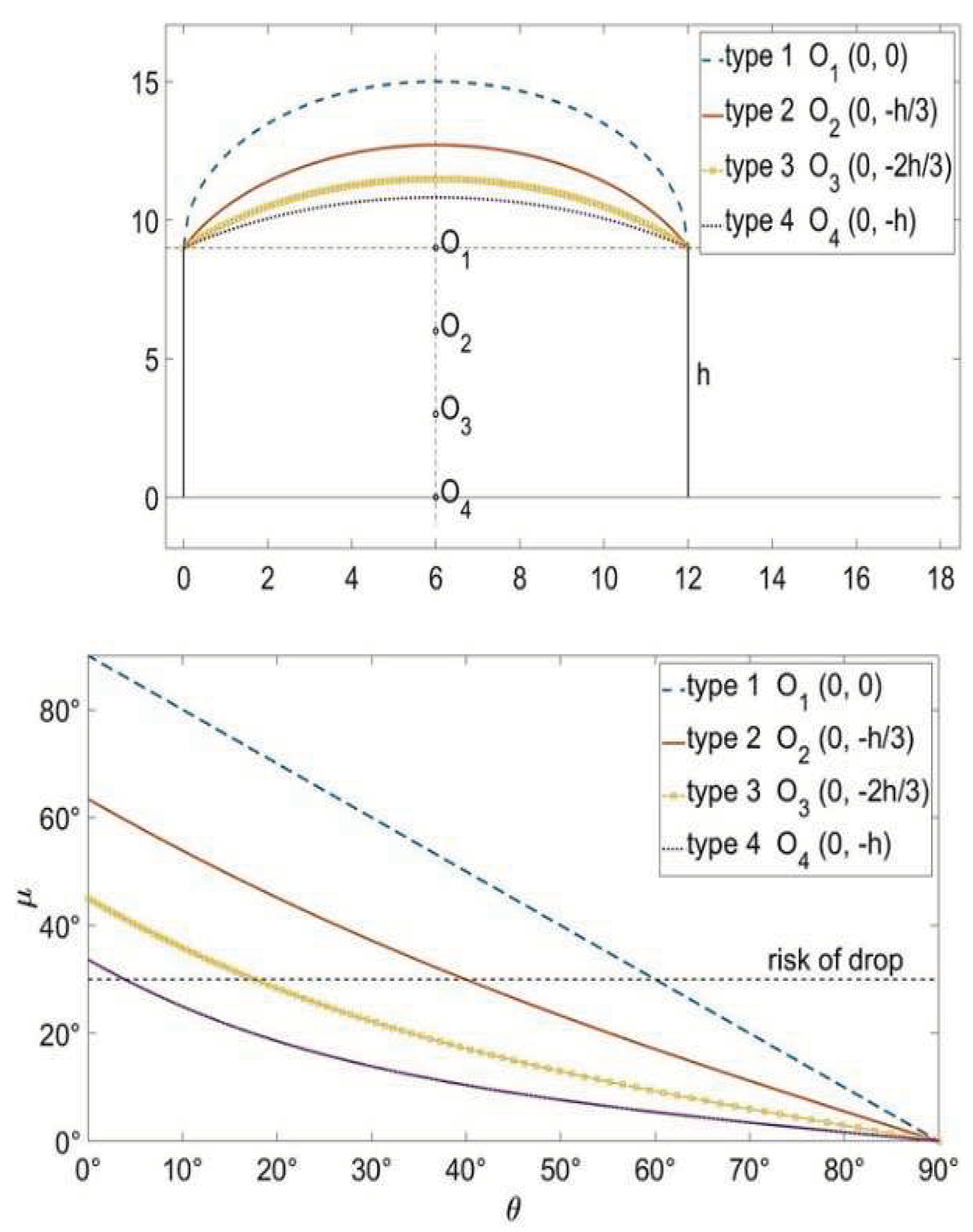

In this section, we are seeking the semicylindrical form of the roof that would result in the least condensation drip inside the greenhouse. In the initial analysis, we study four types in which we vary the y-coordinate of the arch center at 1/3 of the pillar height, h. Type 1, with center O

1(l/2, 0), corresponds to a semicylindrical roof with a radius of l/2, and type 4, with center at O

4(l/2, -h), represents a nearly flat roof (

Figure 6a).

Given the symmetry of the roof, we represent the calculation of the roof’s inclination angle at each point, µ, only for half of it, θ, i.e., between 0 and 90º. The condensed water droplet on the roof will fall into the greenhouse when the roof angle, µ, is less than 30º. For all four types, we observe that µ decreases as it approaches the ridge (

Figure 6b), facilitating dripping in the central zone of the nave.

Of the four types, the semicylindrical form with center at O1 has the longest roof length with angles µ ≥ 30º; therefore, the condensation drip will affect the smallest cultivated floor area. As the arch center decreases, so does the ridge height, and the roof length with µ < 30º increases, affecting a larger cultivation area.

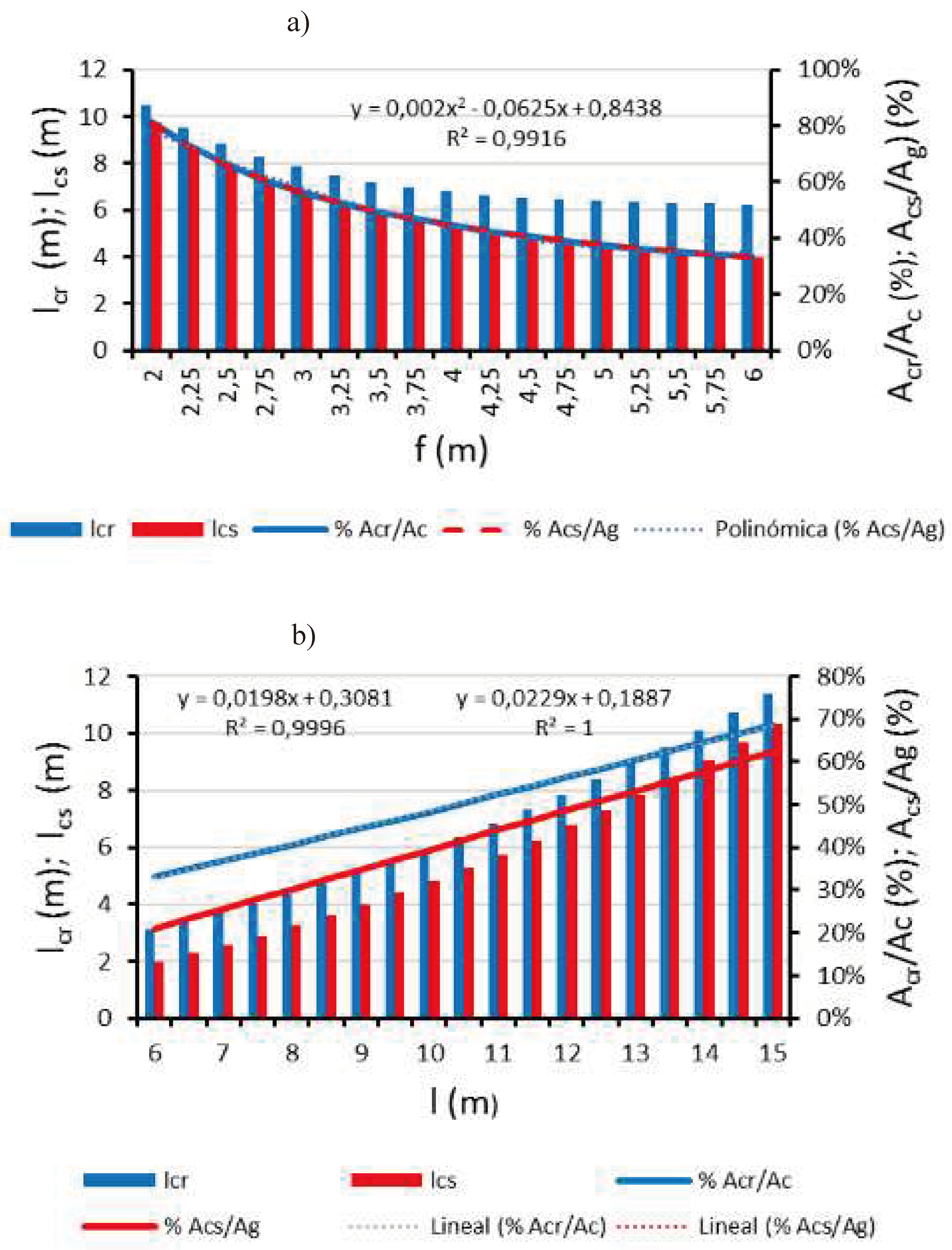

In the greenhouse with a semicylindrical roof, we analyzed the influence of the nave width, l, and the arch height, f, on the condensation water dripping inside the greenhouse. To do this, we calculated the lengths of the roof with a high risk of precipitation, lcr, i.e., with μ <30º, and the length of the ground that defines the horizontal projection of said roof, lcs. Additionally, we calculated the percentage of roof area from which dripping occurs, Acr, relative to the total roof area, Ac. We also obtained the percentage of ground area at risk of dripping, Acs, relative to the total ground area under the greenhouse, Ag. The greenhouse length was considered the same for all cases studied.

We analyzed 17 greenhouses with semicylindrical roofs, in which we varied the ridge height from 2 m to 6 m, keeping the nave width, l, constant (

Figure 7a). We observed that the roof length, l

cr, decreases as the arch height, f, decreases, but to a lesser extent than the ground width on which dripping would occur, l

cs. The variation of A

cr/A

c and A

cs/A

g is identical, fitting a second-degree polynomial function with R

2 = 0.9916. The ground area at risk of dripping, A

cs, decreases by 25% when increasing the ridge height from 2m to 3m, 12% when increasing from 3m to 4m, and only 6.7% and 4.4% when the arch height increases to 5m and 6m, respectively (

Figure 7a). No ridge height was found for which the semicylindrical geometry posed no risk of interior dripping, i.e., A

cs = 0.

For the study of the influence of the porch width, l, we used 19 greenhouse models, in which l varies between 6m and 15m. The ridge height is kept constant at f = 3m, a value that favors structural stability without excessively raising construction costs. The results show that all simulated arches have a high risk of dripping inside the greenhouse (

Figure 7). The relationships of A

cr/A

c and A

cs/A

g fit linear functions with an R

2 = 1 for the latter. In all cases, condensation dripping occurs, and only in widths between 6m and 7.5m is the affected ground surface, A

cs, less than 30% of the total cultivated ground surface, A

g.

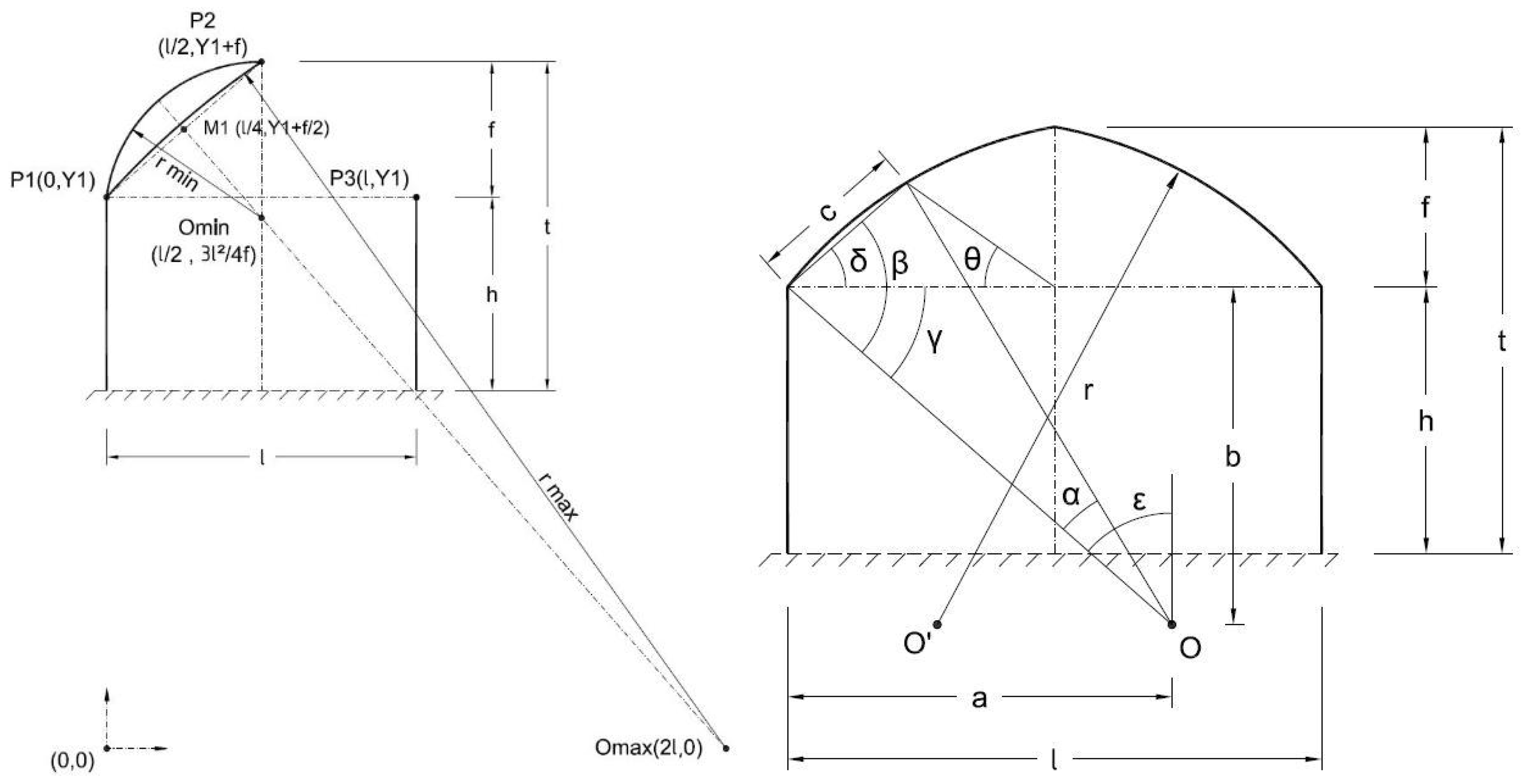

3.3. Analysis of the Ojival Arch Cover

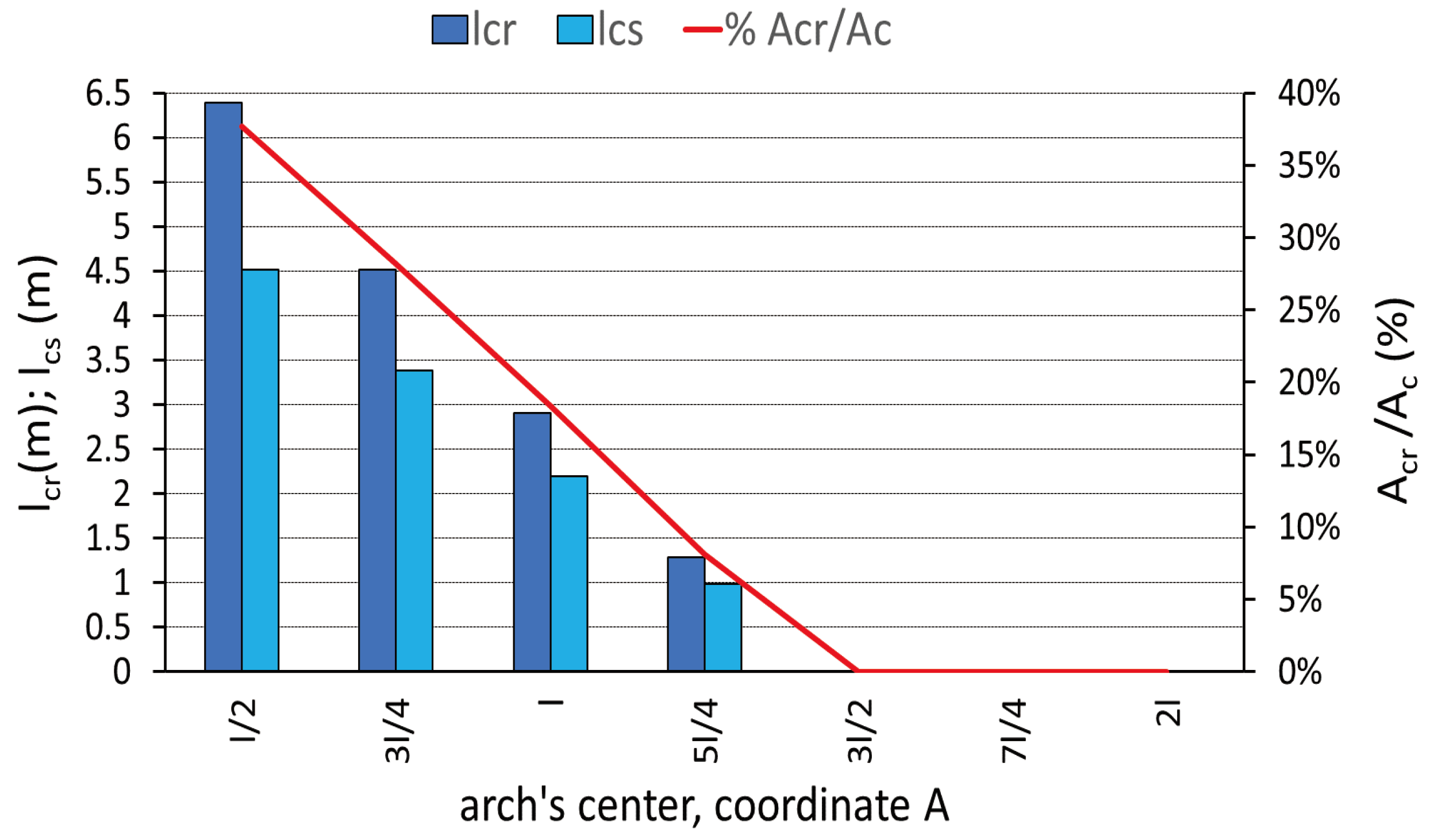

In the greenhouse with a pointed arch shape (ojival), the roof angle, µ, at each point along its length increases as the radius of the arches defining it increases. Unlike the semicylindrical greenhouse, in the pointed arch, it is possible to find an arch with µ ≥ 30° throughout its length, allowing condensation droplets to slide to the ends and not drip inside the greenhouse. Using a pointed arch with l=12m and f=5m, we have analyzed different center positions, O(A,0), defined according to section 2.1.2, in order to identify those where the risk of condensation dripping is negligible. We analyzed 7 types of pointed arches, varying their center coordinate A by l/4, from a minimum to a maximum value. When A=l/2, we obtain the center of the minimum pointed arch, Omin(l/2,0), which corresponds to a semicylindrical roof shape. For A=2l, we obtain the maximum value, Omax (2l,0), and the arch shape has little curvature, resembling a flat two-pitched roof.

The results show that the arches with zero risk of dripping, both in roof length l

cr and its horizontal projection on the ground lcs, correspond to those with a coordinate A between 3l/2 and 2l (

Figure 8). Additionally, the area of the roof that would produce dripping, A

cr, is 38% of the roof area, A

c, in the semicylindrical form (l/2), 18% when A=l, and zero for A=3l/2 to A=2l. From this preliminary study, to obtain more significant differences between the types, we chose four of these roof shapes, denoting them with the value of their coordinate A: semicylindrical (type l/2), two pointed or Gothic (type l and type 3l/2), and two-pitched (type 2l).

Using the Matlab program developed, we calculated the A

cs/A

g ratio for the four aforementioned types, where A

cs is the area of the soil where dripping would occur, obtained as the horizontal projection of A

cr, and A

g is the area of the soil under the greenhouse. For each type, we studied 4 span widths and four arch heights, f, making a total of 68 cover geometries. The span widths, l, used were 9m, 11m, 13m, and 15m, and the maximum arch height, f, ranged from 2.5m to 4m. The results are shown for f/l ratios, distinguishing between different types of arches [

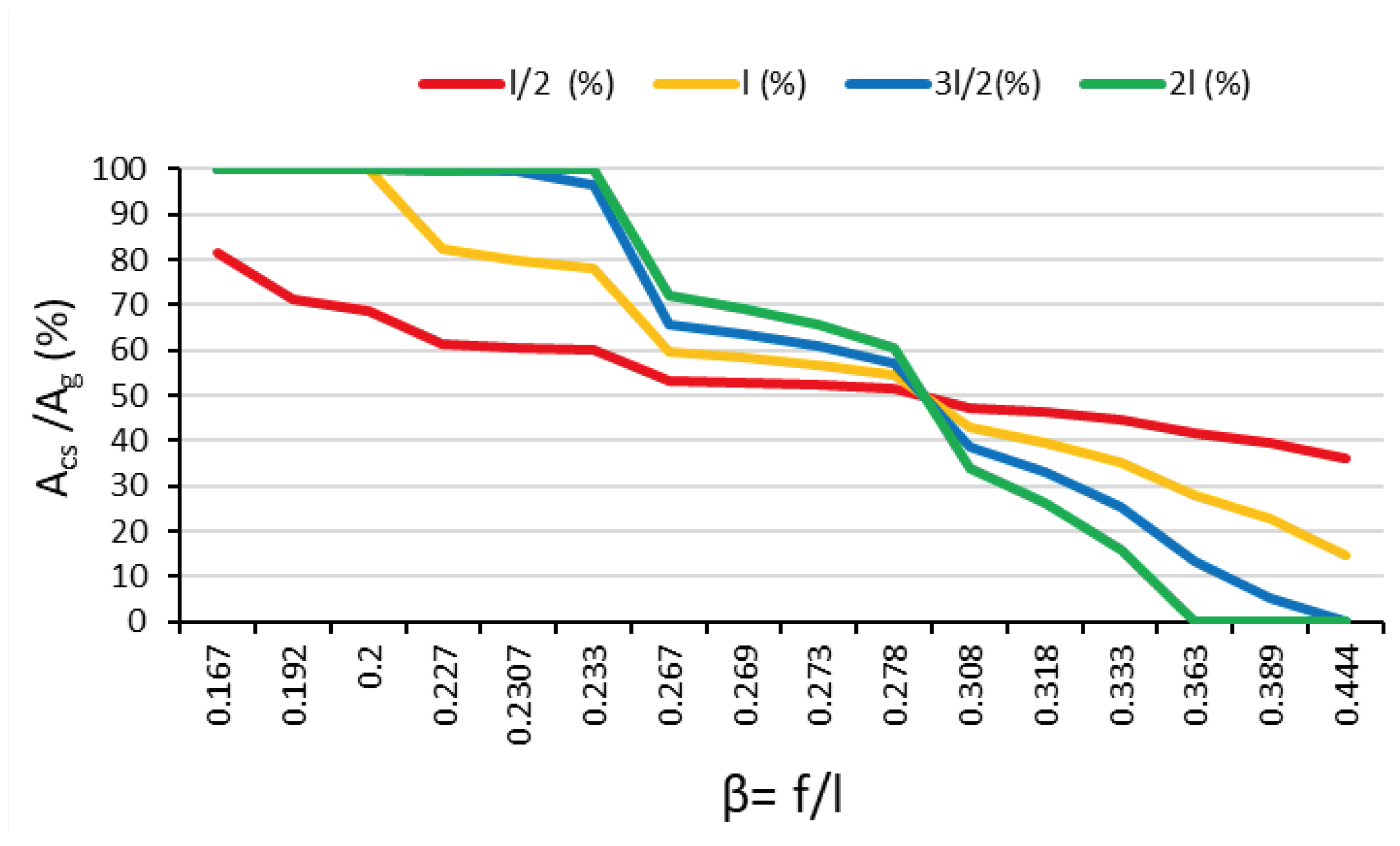

47], denoted as β.

In the four studied cover shapes, the dripping of condensation inside the greenhouse affects more than 50% of the soil area, A

g, when β ≤ 0.278. The gabled form, type 2l, would affect the largest area, while the cylindrical form, type l/2, would be the least affected (

Figure 9). For higher values, β > 0.278, the behavior regarding dripping of different greenhouse shapes reverses, and the affected soil area is less than 50%, with the gabled cover being the least affected and the cylindrical cover being the most affected. In the semicircular greenhouse, dripping affects more than 35% of the soil area, A

g, in all cases studied, while it becomes zero for the ogival forms, 3l/2, and gabled, 2l, when β > 0.389 and β > 0.363, respectively. We conclude that only in those arcs with smaller widths, l=9m, and greater heights, f=4m and 3.5m, dripping does not occur on the crop.

3.4. Influence of the cover shape on the greenhouse volume

The height of the greenhouse determines the unit volume of air inside and its thermal inertia [

1]. Taller greenhouses have greater thermal inertia and improve ventilation efficiency. Under equal design parameters, those with a semicircular cover,

l/2, enclose the greatest volume of air, while those with a straight gable cover enclose the least. In this study, we consider the four cover shapes from the previous section, namely types

l/2, l, 3l/2, and

2l, to determine which cover shape would be most suitable under different climatic conditions.

We define the following design parameters: number of spans,

n; span width,

l; pillar height,

h; span length

, p; arc length,

lc; the angle that defines the cover,

µ; and the transversal cover area,

Act. To calculate the volume of air inside the greenhouse (Equation 10) and make it dependent only on the cover shape, we keep the parameters

n and

p constant. The pillar height,

h, is set at 6m.

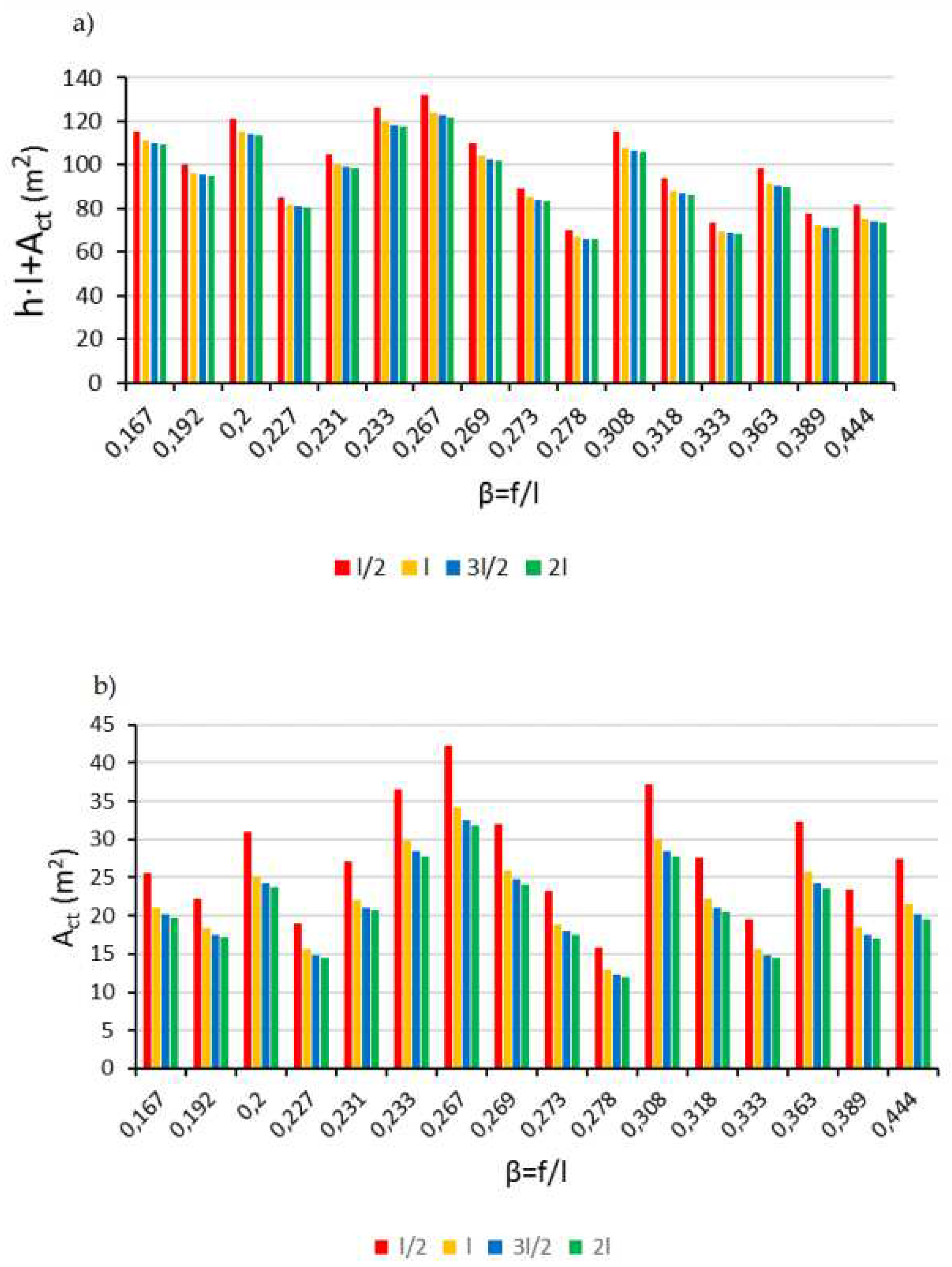

The volume of air depends on the number of spans and the length of the greenhouse, allowing for a comparison of different greenhouse shapes when a specific value for

h is fixed. For h=6m, it is observed that the total area is larger in the semicircular greenhouse,

l/2, and smaller in the gable roof,

2l (

Figure 10a). When comparing the transversal cover area,

Act, (

Figure 10b) with the total area (

Figure 10a), it is found that the volume primarily depends on the pillar height [

48]. The volume does not correlate with the growth of

β.

Greenhouse types that minimize condensation dripping inside correspond to those with smaller l and larger f, i.e., with β ≥ 0.363, and the volume of air due to the shape of the cover is similar to those with β ≤ 0.2. Therefore, it is possible to find relationships between the cover angle and span width that optimize both condensation sliding and the volume of air inside the greenhouse. Thus, for all cover heights, a span width of 9m meets both conditions, and for a span width of 11m, cover heights of 3.5m and 4m also meet the criteria.

Finally, there is only a maximum difference of 1% in the volume of interior air between the 3l/2 and 2l shapes, so this would not be a deciding factor between them.

3.5. Influence of the roof type on heat losses and gains

A greenhouse is more energy-efficient when it requires less fossil energy to heat or cool its interior. From this perspective, the shape of the roof influences the amount of received solar radiation and heat losses to the outside. The four types of greenhouses studied do not have significant differences in the roof angle along their length. However, there are differences in the roof surface, significantly affecting the energy efficiency of the greenhouse.

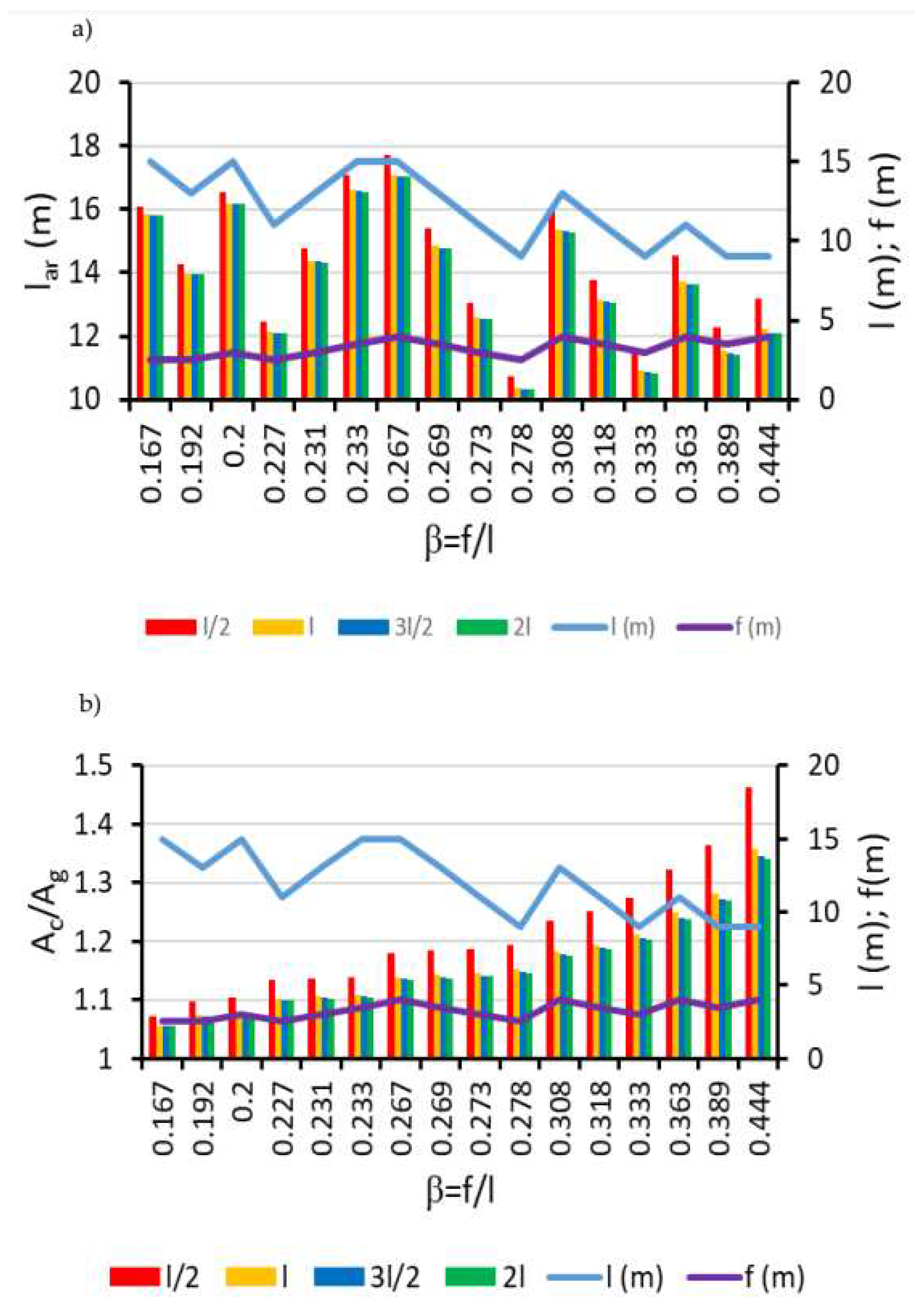

We have calculated the roof surface, which depends only on the arc length,

lar, assuming a constant greenhouse length,

p, for all studied types. Generally, the results show that semicircular roof greenhouses have a longer arc length than ojival roofs, with very small differences among the ojival types when compared for the same width,

l, and height,

f. The semicircular roof has 10% more surface than the other forms, while the difference between the ojival forms is 0.2%. These percentages decrease as the span width increases. Therefore, in terms of solar energy capture by the roof surface, semicircular greenhouses would be more efficient [

49], with almost two-walled ojival ones being the least efficient. However, it is observed that similar arc length values can be obtained for different width values (

Figure 11). Therefore, the efficiency of the roof cannot be determined using the ratio =

f/

l, as it does not show growth or decline when

Ac does.

To compare different greenhouse roof forms when

f and

l vary, it is recommended to calculate both solar radiation capture and heat losses using the ratio

Ac/

Ag, defined as the ratio of the roof surface

Ac to the cultivated ground surface

Ag [

15,

49]. The results for the four roof types (

Figure 11b) show that as the value of

β increases, the

Ac/

Ag ratio also increases. Depending on the season, the efficiency in capturing solar energy varies. During winter, increasing the height of the roof,

f, and decreasing the span width,

l, increases solar energy capture [

50]. The semicircular roof,

l/2, remains the one that will capture the most solar energy for any

β value, followed in decreasing order by types

l, 3

l/2, and 2

l, with the most efficient corresponding to the roof with the smallest width,

l=9

m, and roof height

f=4

m and 3.5

m.

However, the curved surface, from June to September, with an ojival shape, absorbs less solar radiation as the height,

f, increases in relation to the width,

l. In contrast, from December to March, the opposite occurs when compared to an inclined flat surface [

15]. Therefore, ojival-shaped roofs become less efficient in capturing solar energy as

β increases and the roof surface becomes larger. For this reason, these roofs are suitable for greenhouses located in warm climates at middle latitudes.

On the other hand, it should be considered that the higher the ratio between the roof surface and the ground surface,

Ac/

Ag, the greater the thermal exchange with the external environment. This results in higher energy consumption for heating or cooling the interior [

49]. Thus, in cold and very warm climates, the least energy-efficient roofs would be those with high values of

Ac/

Ag and

β, as a larger roof surface causes greater heat losses [

17]. Additionally, in desert climates, the increased water consumption of evaporative cooling systems is particularly relevant [

51].

Greenhouses with arched roofs require less energy for heating during winter, and the opposite occurs during summer [

12]. In warm climates, the semicircular arched shape, with a low

f/

l, would require less energy annually. However, several authors have studied the energy needs of various greenhouse shapes, finding that the most efficient shape is similar to the gothic form, type

l, studied in this work [

12,

52].

In warm climates and low to mid-latitudes, when cooling needs exceed heating, and natural ventilation is the primary cooling method, roofs with a higher Ac/Ag ratio and a greater angle at all points are the ones that require less energy annually. Therefore, the recommendation is for the ogee-shaped (type l) roof with narrower spans (l=9 m).

In cold climates and high latitudes, high roof angles are recommended to increase solar energy capture, along with low values for the A

c/A

g ratio to minimize heat losses. The ogee-shaped roof, specifically type

3l/2, with small β values (larger spans), is advisable, as suggested by other authors [

17].

Finally, the most energy-efficient greenhouse is the one with the smallest exterior surface area relative to the covered floor area. The energy consumption for heating can increase by up to 42% in single-span greenhouses compared to multi-tunnel structures [

25]. Therefore, in extreme climates, roofs with a lower A

c/A

g ratio and

β values are recommended, especially for multi-span greenhouses."

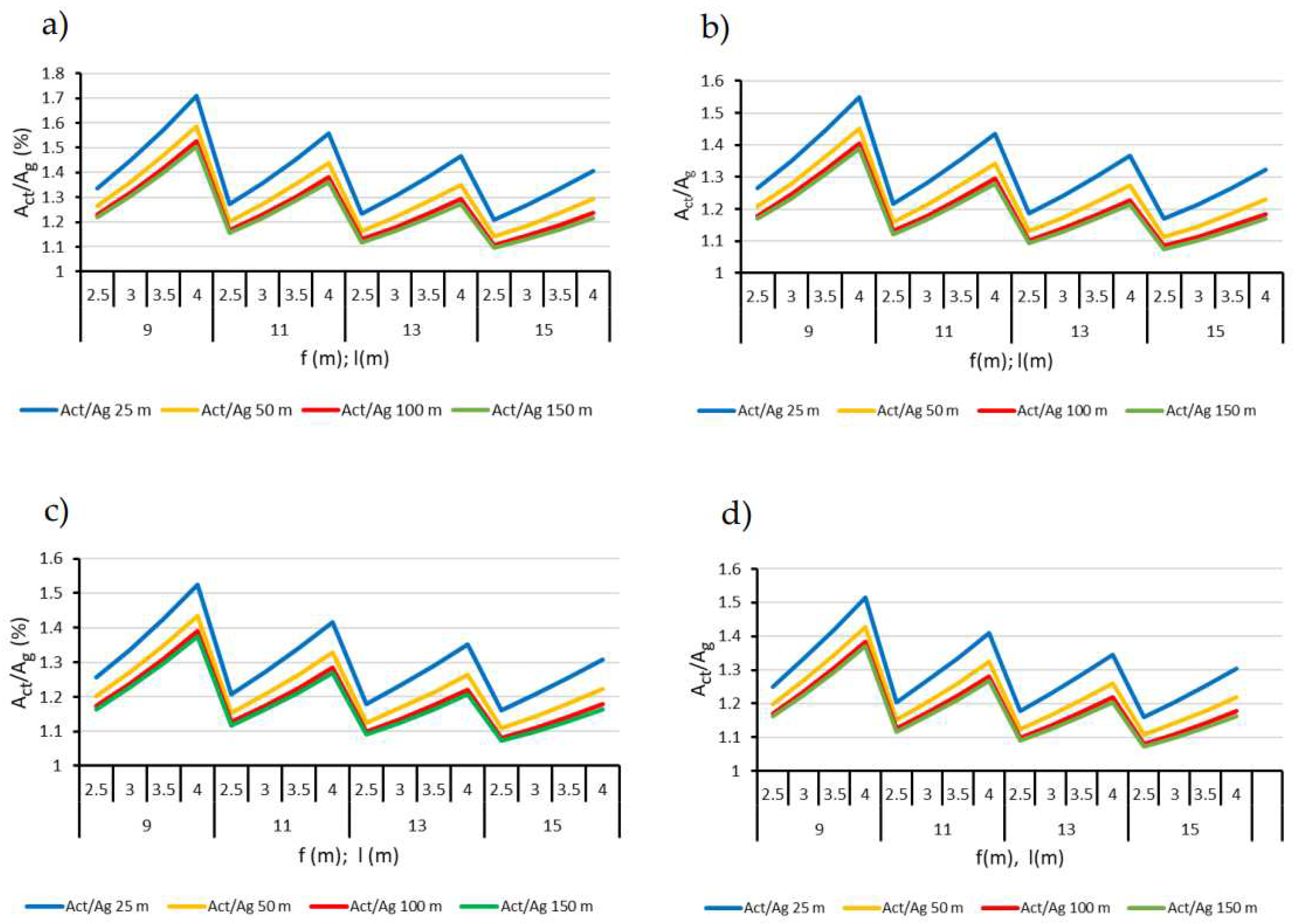

3.6. Impact of greenhouse length on energy efficiency

We have calculated the ratio of the total area of the greenhouse cover, including the cover and end walls (A

ct), to the ground area (A

g), (A

ct/A

g) for the studied greenhouse models:

l/2, l, 3l/2, and

2l, using four greenhouse lengths (25m, 50m, 100m, and 150m). The results show that beyond 100m, the A

ct/A

g ratio barely varies (

Figure 12).

It is observed that in the semicircular greenhouse model,

l/2, the highest values of cover area in relation to cultivated soil are obtained. This type of cover would capture the most solar radiation but also have the highest heat exchange with the exterior [

14]. In general, in all models, the greatest decreases in the ratio correspond to a length of 50m. A larger cover area increases heat losses through it, which is particularly relevant in multi-span greenhouses [

25], as the cover surface is significantly larger than the sidewalls. The length of the greenhouse would not influence energy losses through the cover surface by conduction beyond 100m. The optimal size of the greenhouse in arid climates will have a ratio between its width and length of 0.5 [

16], thus being 50m wide and 100m long.

5. Conclusions

The developed program allows for the calculation of various geometric parameters for both semicylindrical and ovoidal arches. By varying both the span width, l, and the arch height, f, any geometry ranging from an arch with a radius of l/2 to a flat or triangular surface can be obtained.

Ovoidal (ojival) cover shapes facilitate the sliding of condensed water droplets on the greenhouse cover, preventing interior dripping. It is not possible to find a semicylindrical shape that does not result in condensation water dripping into the greenhouse interior.

The volume of air inside the greenhouse depends primarily on the pillar height, with small differences attributable to the shape of the cover.

Solar radiation capture by the greenhouse cover increases for high values of Ac/Ag and β, which is achieved with narrower spans and higher arch heights. Accordingly, we classify the studied cover types in decreasing order of solar energy capture efficiency: type l/2, type l, type 3l/2, and type 2l.

As the cover angle increases, the Ac/Ag ratio also increases, leading to higher heating demands during winter. If the angle is too low, snow accumulation could pose a risk to the structure in northern latitudes, recommending an angle of 25º-30º to allow for snow sliding.

In warm climates and medium to low latitudes, where cooling needs outweigh heating, and natural ventilation is the primary cooling method, covers with a higher Ac/Ag ratio and a greater angle at all points require less energy annually. Therefore, the ovoidal shape 3l/2 and smaller span widths, such as 9 m, are recommended.

Ovoidal cover shapes have a lower Ac/Ag ratio than the semicircular form, reducing energy losses, especially for low β values. In cold climates and high latitudes, the ovoidal shape l is recommended due to its higher angles throughout its length compared to the two-way shape, 2l, and only a small difference in total surface area between them. This increases solar energy capture and decreases heat losses through the cover. Larger span widths of 13m and 15m with a 2.5m arch height are preferable.