1. Introduction

The greenhouse effect refers to the increase in temperature that occurs when a microenvironment is enclosed by a transparent material that allows incoming solar radiation (Tiwari, 2001). The effect results from two combined mechanisms, which may act simultaneously and to different degrees. The first is the spectral selectivity of transparent enclosures: materials such as glass or polycarbonate are highly transparent to solar radiation, while opaque or partially opaque to longwave radiation. Once solar radiation enters the enclosure, it is absorbed by interior opaque surfaces (e.g. walls or ground) and re–emitted as longwave radiation, which is then trapped inside the enclosure due to the longwave opacity of the transparent material.

The second mechanism is the retention of air caused by the physical enclosure of the space. Indeed, even if the structure were fully transparent to longwave radiation, a greenhouse effect would still occur, since the absorbed solar radiation heats the interior surfaces and, in turn, the confined air [

1]. The temperature rise would be maintained simply because air exchange with the exterior is restricted. In high–performance passive solar systems, these two conditions - longwave opacity and airtightness - combine to produce substantial temperature increases. In other cases, such as greenhouses covered with ordinary thin films, the longwave opacity is only partial, and the greenhouse effect is reduced. Similarly, in semi–outdoor spaces that are fully transparent to longwave radiation but poorly enclosed against air exchange, the greenhouse effect is strongly diminished.

In conventional greenhouses, the heat generated through the greenhouse effect is intended to condition the indoor environment for plant growth. But when greenhouses are attached to a building, part of the heat can be transferred to the adjacent interior space, either by conduction through the internal wall, by convective thermosyphoning, or by a combination of both [

2,

3,

4].

A more specialized version of the attached greenhouse is the solar wall [

5,

6]. The solar wall can be considered a greenhouse in which the depth of the space has been minimized, so that height and length dominate over width. As a result, winter solar gains depend mainly on aperture height and length, while thermal losses are strongly proportional to the aperture width. Reducing the width, therefore, decreases heat losses while only minimally reducing solar gains, which improves the thermal efficiency of the system [

7].

As in greenhouses, solar walls can deliver heat to the interior by conduction, convection, or a combination of both [

8,

9]. Early solar walls were massive and relied primarily on conduction. In these systems, the wall mass acts both as thermal storage and as a regulator of heat transfer, depending on its thickness, thermal conductivity and density. A drawback of massive solar walls, however, is that on cloudy winter days, they can become a source of heat loss due to conduction through the mass in the absence of solar gains [

10,

11]. This has made the earliest versions of passive solar walls primarily successful in climates characterized by a regular strike of winter cold nights and sunny days, like in New Mexico. To reduce heat losses and to accelerate heat transfer to the interior, ventilated solar walls were developed - commonly known as Trombe walls [

12] - where heat can be transferred by conduction and convection, and convection can be interrupted when solar input is insufficient [

13].

In configurations with low thermal mass and opaque insulation in the cavity, heat transfer by conduction is also limited. In such cases, heat transfer is achieved mainly through convection, either by passive thermosyphoning or by fan-assisted ventilation [

14] (Ong and Chow, 2003). These systems are usually classified in the literature as solar air collectors rather than solar walls.

An advantage of both Trombe walls and insulated wall air collectors is that in the hot season their circulation loop can be cut off from the interior space, so that they discharge heat directly toward the outside, from outside to outside, in order to limit (in case of Trombe wall) or nullify (in case of insulated wall air collectors) their solar gains [

15,

16,

17]; and enhancements to this scheme via coupling with solar chimneys has been studied [

18]. But in any case, such a strategy can be defined of overheating avoidance, rather than passive cooling. The other strategy for controlling the performance of Trombe wall of wall passive air collectors is also based on overheating avoidance, and consists of solar control, most usually via shading fins [

19,

20] coupled with outside-to-outside or inside-to-outside ventilation [

21].

To improve the thermal performance of Trombe walls, transparent insulation can be introduced beneath the glazing to reduce heat losses [

22,

23]. In addition, selective coatings with high solar absorptance and low thermal emittance may be applied to the wall surface. These measures significantly improve performance, so as to make cavity ventilation not certainly detrimental, but unneeded to get results which are considered sufficient. The consequence is that in current practice, the most common type of solar wall is non-ventilated and insulated with transparent insulation [

24].

This article assumes that, if a solar wall is installed on the interior side of a room, facing outdoors, it can transfer the heat generated by the greenhouse effect from the room to the exterior, rather than from the exterior to the room. The idea is that, in this way, the room could be maintained at a lower temperature than it would be without the interior solar wall, under the same indoor solar radiation conditions. Such a configuration is meaningful in situations where high daylight levels are required indoors, as is often the case in modern buildings in temperate climates. The deeper implication of this strategy lies in expanding the architectural palette of passive cooling solutions in hot-climate countries. In many of these countries - often including developing regions - traditional buildings tend to be dark inside in order to avoid overheating, with daylight levels that are insufficient for common modern activities such as reading, or high-precision work. These situations apply not only to dwellings but also to schools, offices, and libraries, and may even affect greenhouses cultivating light-demanding plant species.

The solution in question can be seen as an indoor analogue of the ventilated facade, in which the heat gained in the cavity promotes the thermal buoyancy in it and favour heat flush [

25,

26,

27]; with the difference that a ventilated facade is usually ventilated in an outer layer, due to the heat gained from the outside [

28,

29] , while in the present case, the ventilated cavity is towards the interior and the heat is gained in a passive solar manner from the inside.

The feasibility of the proposed strategy has been demonstrated, as a proof of concept, through monitoring and calibrated simulation of small-scale prototypes, and through simulation of a real building retrofitting scenario, considering both unventilated (conductive only) and ventilated versions of the system.

2. Methodology

This study combines physical experimentation and simulation to test the effectiveness of reverse solar walls in reducing indoor temperatures. Two approaches were pursued: (1) small-scale twin prototype testing; 2) calibrated simulation of the small-scale prototype and of real-scale ones derived from the former ones; (3) simulation of retrofit scenarios in a real building exemplifying a possible architecturally integrated use of the system.

2.1. Prototype Experiments

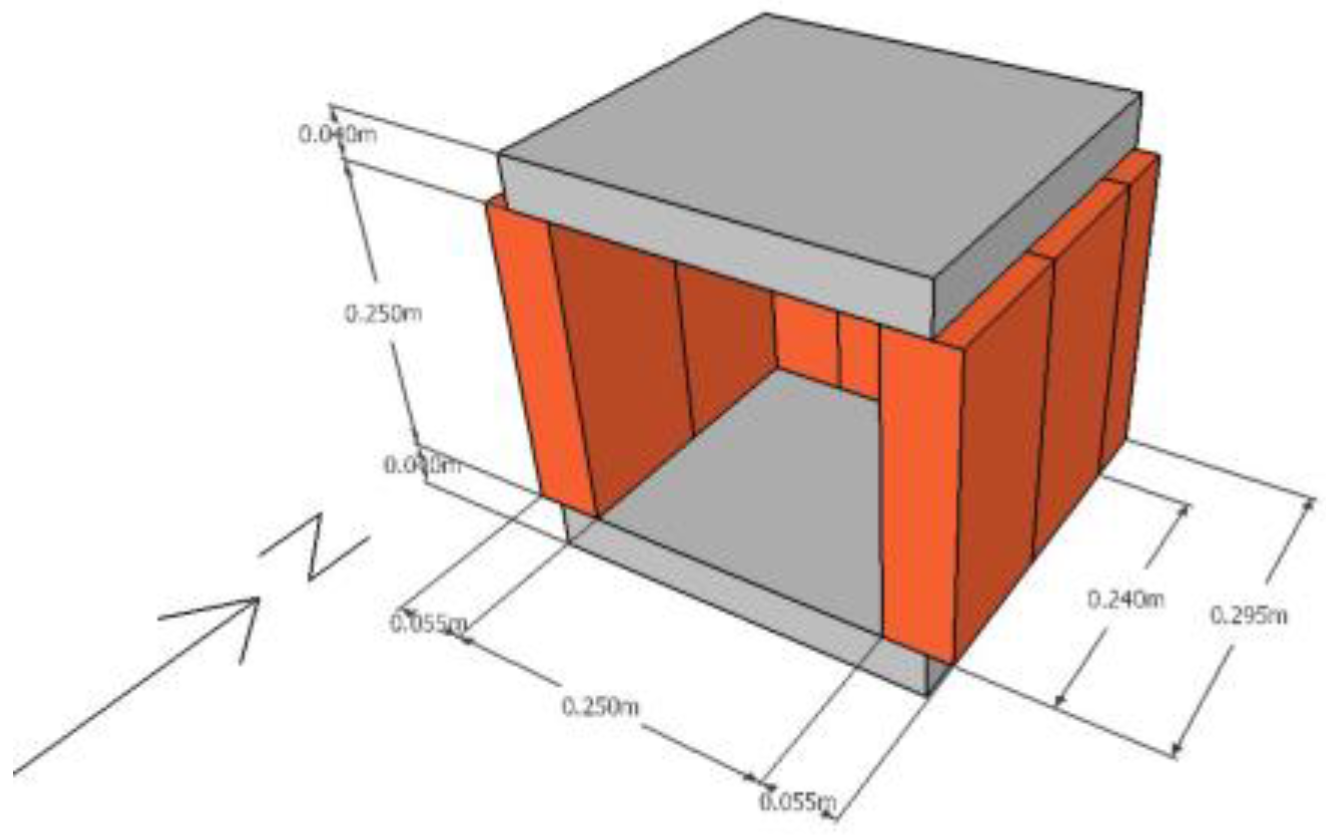

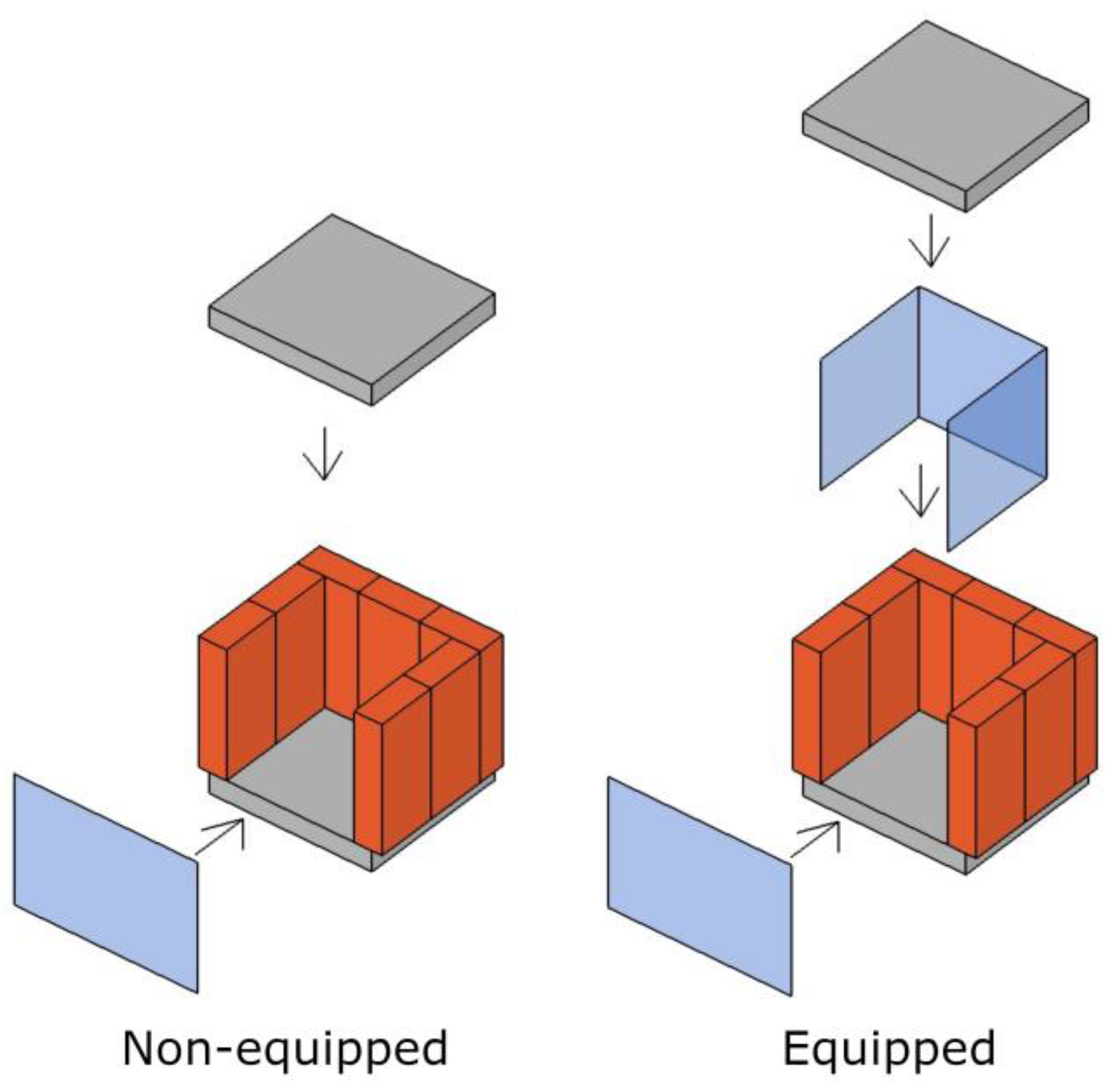

Two twin small-scale prototypes were constructed and monitored during August 2025 in the city of Trapani, Sicily, Italy (latitude 38.01°N), to compare thermal behaviour with and without the proposed system. Each prototype consisted of a small chamber measuring 25 × 18 cm in plan and 25 cm in height. The roof and floor were made of 4 cm thick concrete slabs, while the walls were constructed with vertically placed fired clay bricks (standard size: 25 × 18 × 5.5 cm - net dimensions), using the short side to determine wall thickness (

Figure 1).

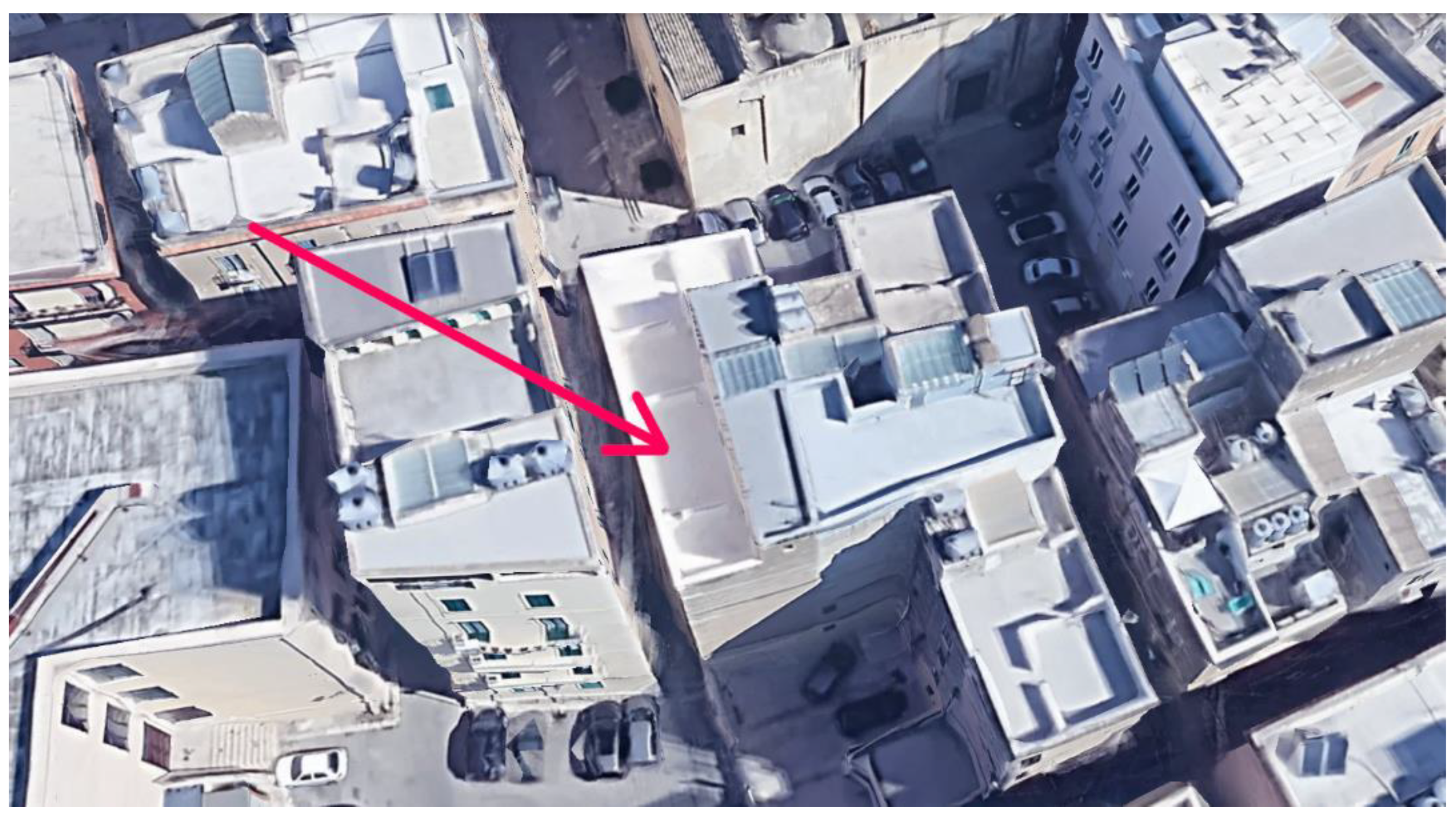

The front (solar facing) side of each chamber was enclosed with a transparent polyethylene mesh with module of 4 x 4 mm, expected to let a ventilation efficiency of about 75%. In the calibration models, this surface was oriented 18° counterclockwise from due south (i.e., facing south-southeast), so as to let the walls of the chambers be parallel with the edges of the rooftop that were utilized, which was a flat high-albedo (≈ 0.8)) flat roof, lime-coated, albedo, shaded by surrounding built volumes except the hours between 10:00 and 14:00 (11:00 to 15:00 daylight saving time) (

Figure 2,

Figure 3).

One chamber was configured with a passive solar arrangement (

Figure 4). Its inner side and rear walls were clad with three transparent polyethylene film layers, each separated by an air gap of approximately 1 mm. The estimated opacity to far infrared radiation of each film was in the range of 60% (Tong et al., 2022), and therefore the overall estimated cumulative longwave opacity of the three layer was in the range of 6%. The films were sealed at the edges with transparent tape to prevent air infiltration between them and between the cavity and the chamber. The concrete ceiling slabs were left bare, and the floors were lime-washed, so as to reach a reflectance of about 0.8.

In the solar-ventilated-wall version, the cavity created by the transparent enclosure was opened toward the outside through the bricks for an amount of 10 cm2 distributed along the top and the bottom of the enclosures.

The monitoring of the prototypes was performed in the period of mid-August 2025.

Air temperature inside each chamber was recorded hourly using Elytec digital thermometers model RC51 positioned near the back wall.

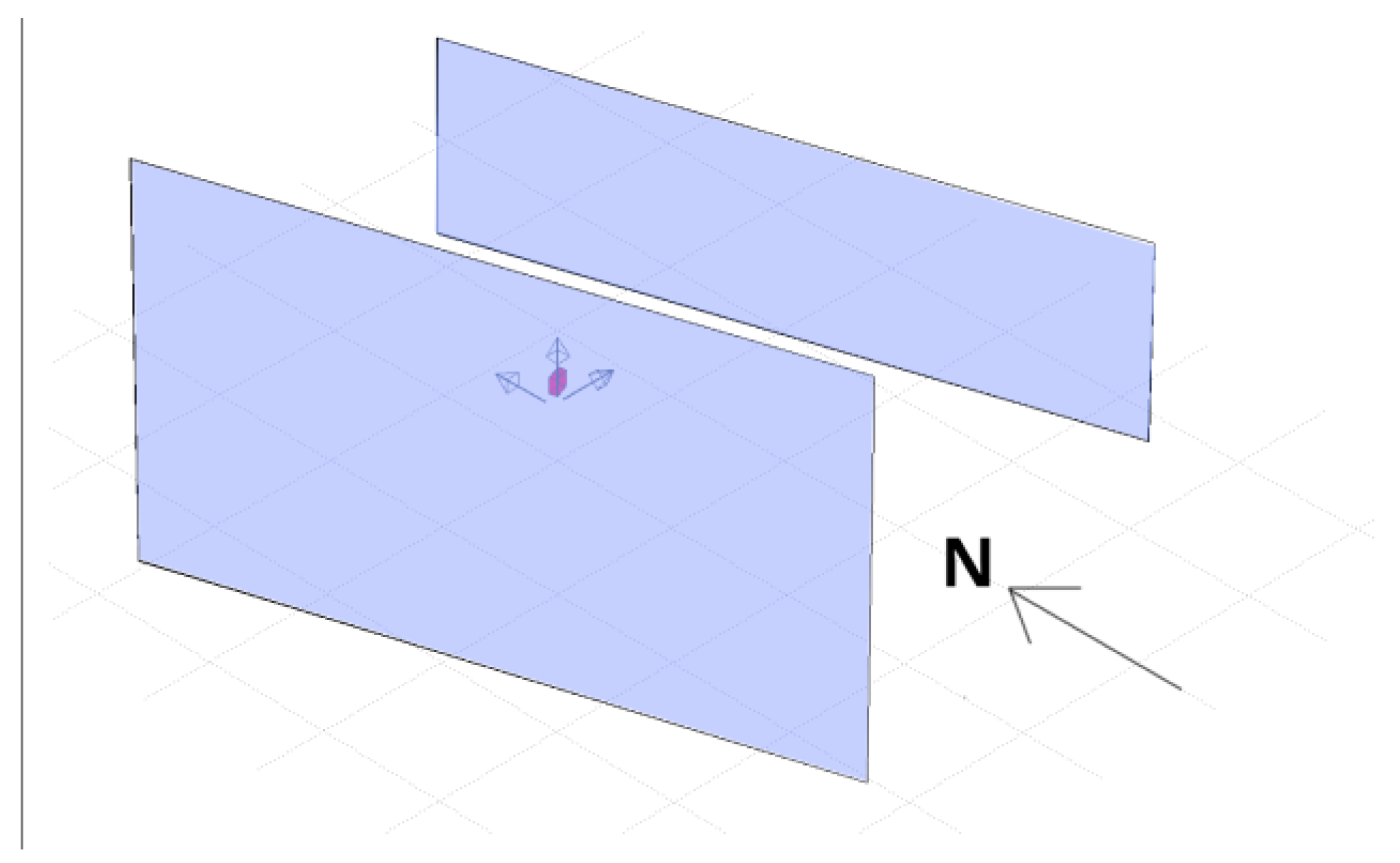

Thermal simulations were conducted in parallel to the monitoring utilizing the ESP-r energy simulation software (Clarke, 2001). The material properties were set as follows: brick conductivity = 0.7 W/m·K; concrete = 1.7 W/m·K; transparent insulation cavity = 0.1 m²·K/W. Ground reflection was modelled diffusely, and indoor surface reflections were likewise treated as diffuse.

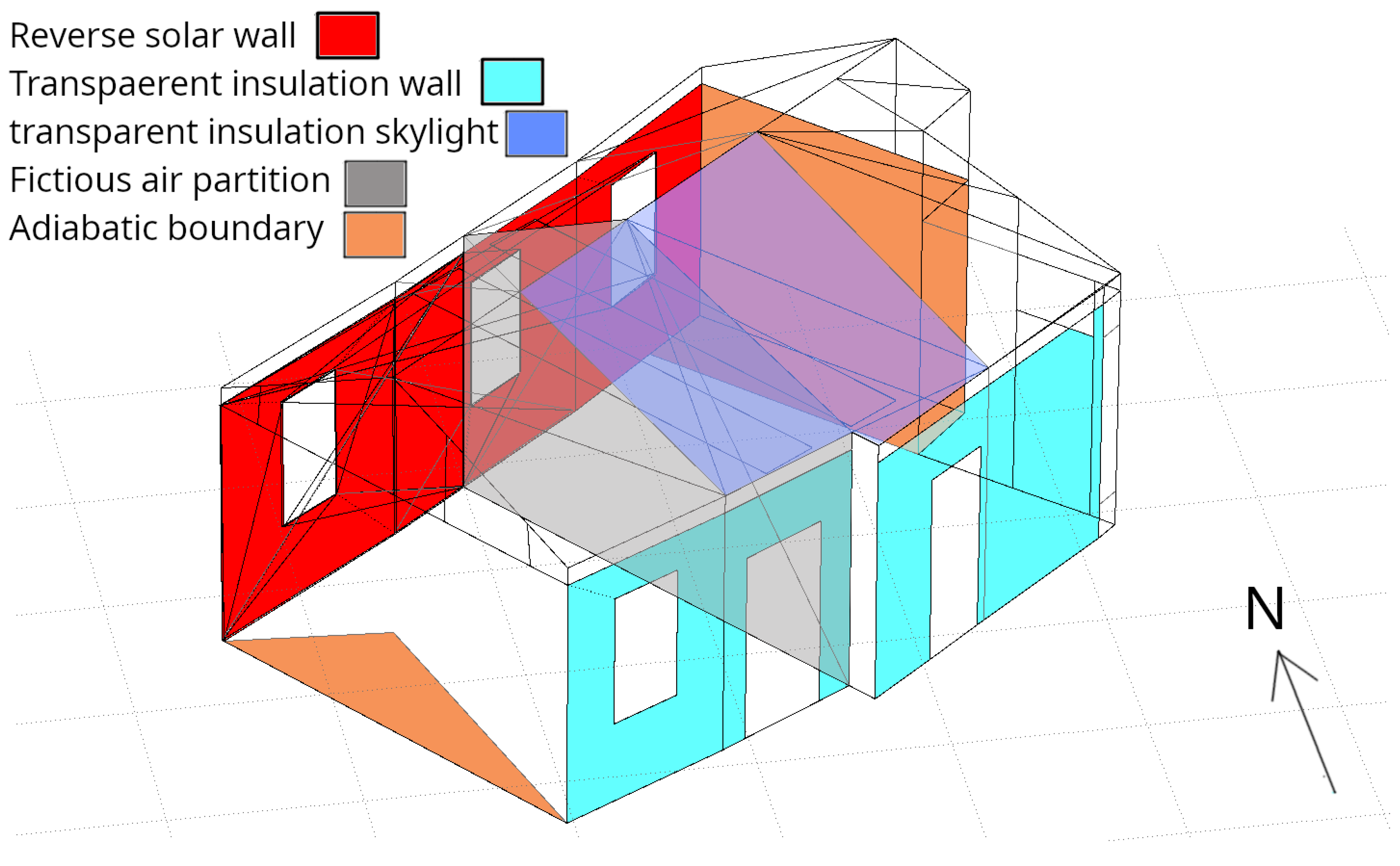

The prototype without the reverse solar wall (“bare” model) was modelled as a single thermal zone, while the version with the reverse solar wall was modelled as two thermal zones: one for the main chamber, one for the solar gain cavity. The solar obstructions were taken into account in both models (

Figure 5).

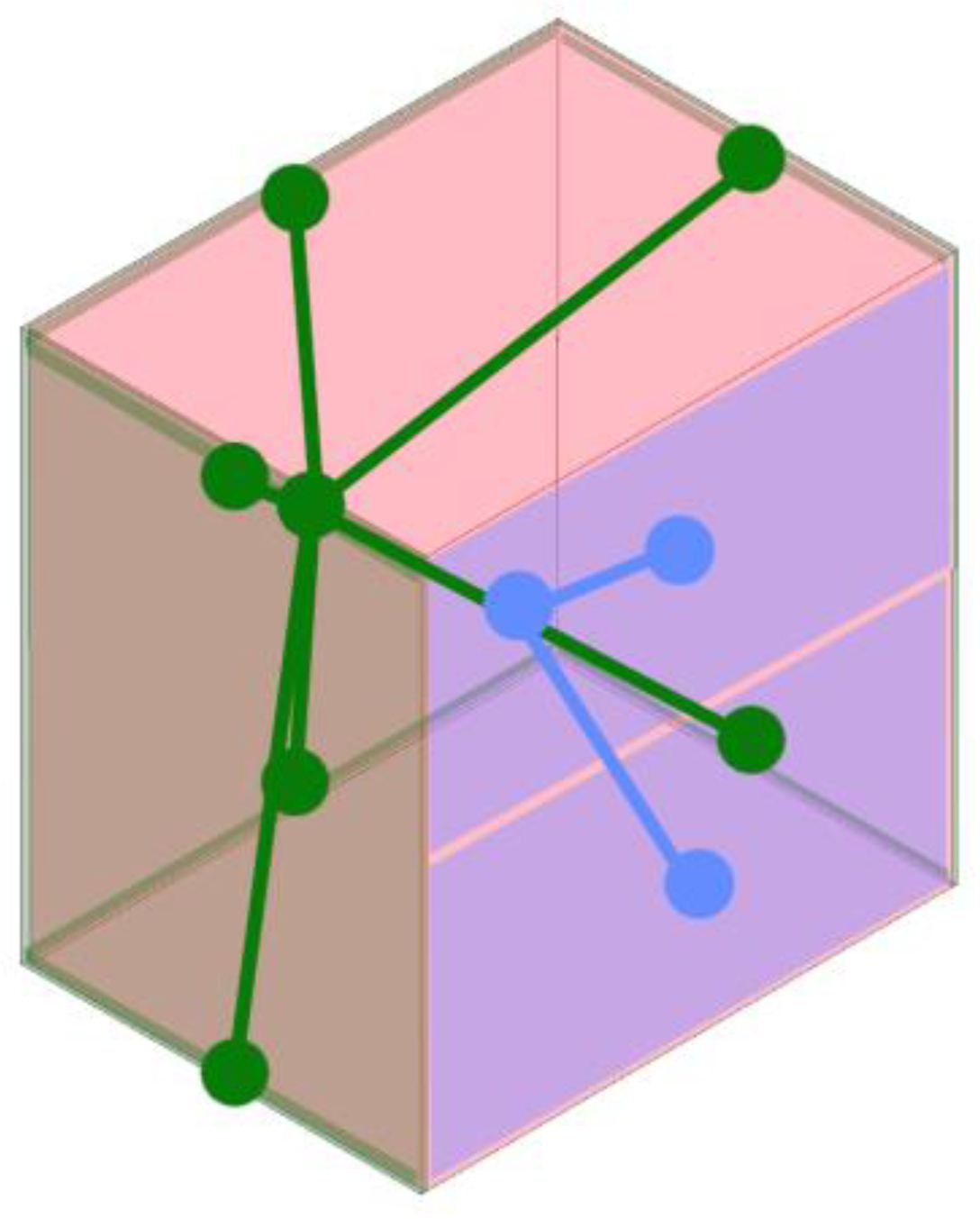

For each model, a ventilation net was created. The main zone had two boundary nodes on the facade, one at the top half and the other at the bottom half of it. And the ventilated cavity had six boundary nodes modelled as openings, one at the bottom and one at the top of each wall, each one of dimension of 1 x 10 cm (

Figure 6). The two indoor volume nodes were not communicating, and the “bare” model did not have the nodes related to the ventilated cavity.

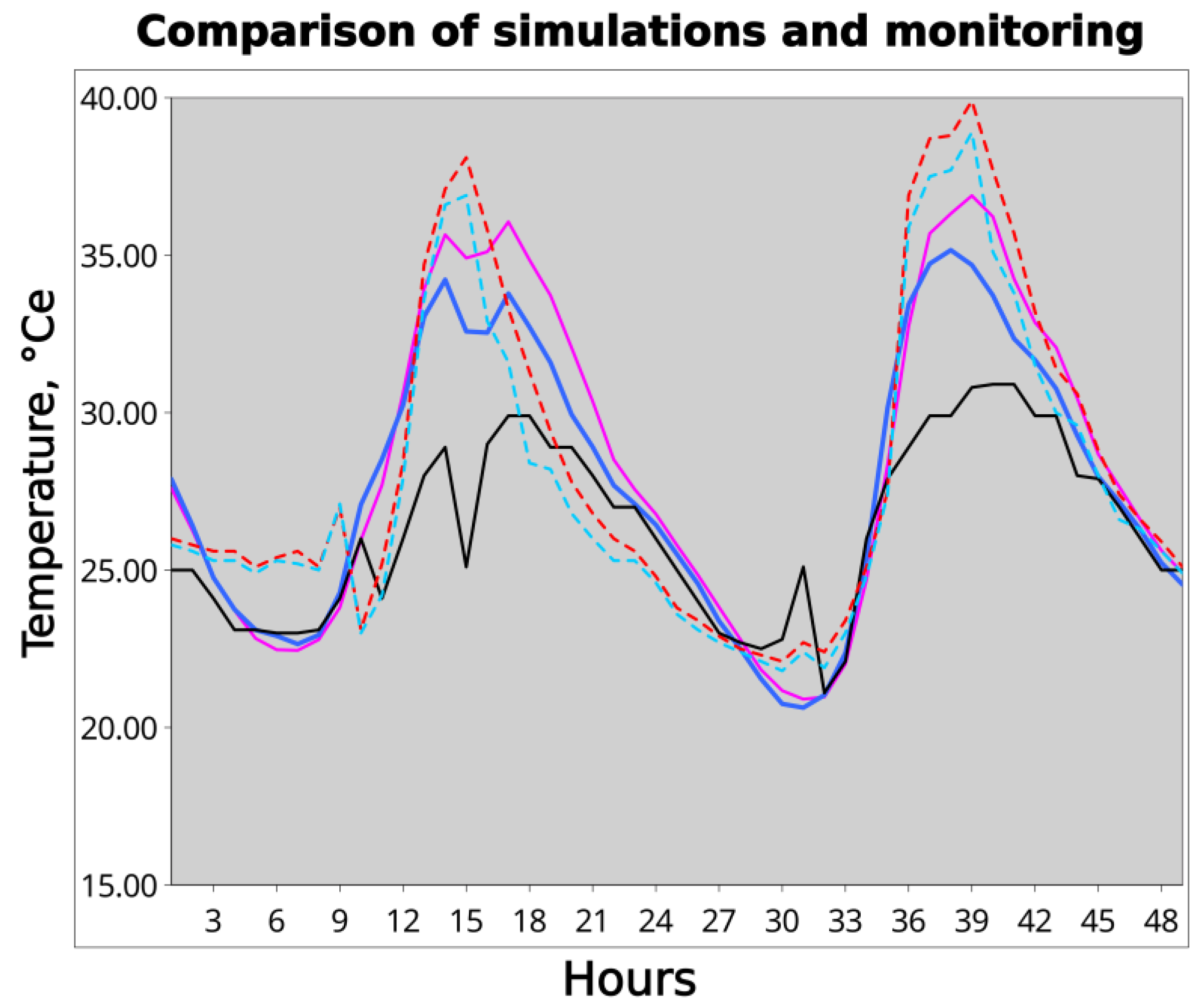

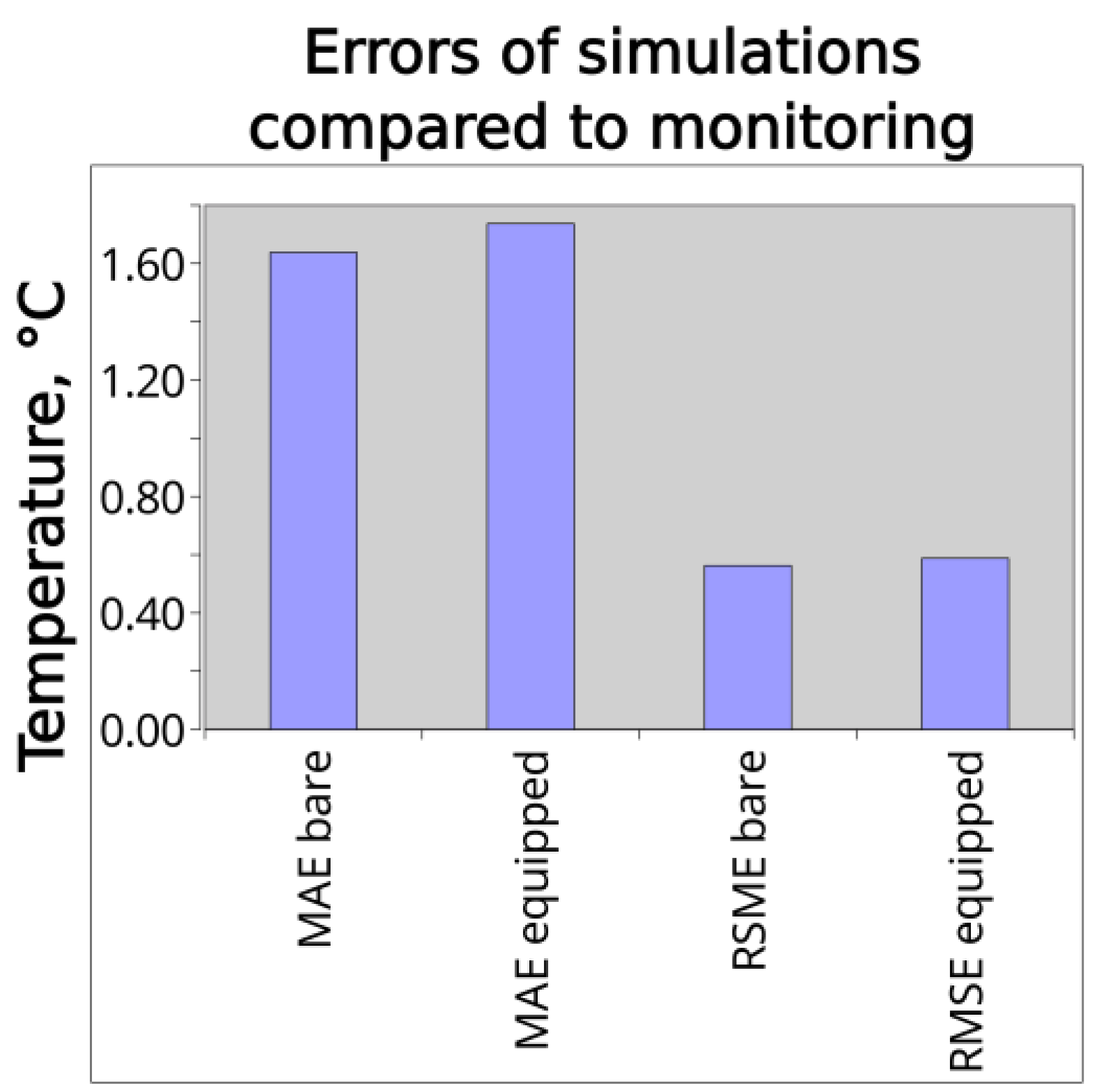

The simulation models of two prototypes were validated by comparing their air temperatures with the air temperatures monitored during August 17thth and 18 in Trapani, inclusive of the urban obstructions which were present in the scene. The concordance of the data was considered acceptable (

Figure 7), featuring a mean absolute error in the range of 1.5 and a Root Mean Squared Error of about 0.5 (

Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Temperatures in the monitored prototypes and in the simulation models during August 17th and 18th.

Figure 7.

Temperatures in the monitored prototypes and in the simulation models during August 17th and 18th.

Figure 8.

Mean Absolute Errors and Root Mean Squared Errors in the simulations with respect to the monitored air d.b. temperature data between August 17th and 18th.

Figure 8.

Mean Absolute Errors and Root Mean Squared Errors in the simulations with respect to the monitored air d.b. temperature data between August 17th and 18th.

After the confirmation of the good concordance between the simulation models and the concrete ones, the trials were developed on a version of the models made more general by removing the obstructions which were present on site and the 18 °C rotation, and by adopting the IWEC weather data of Palermo, 2001, rather than those of Trapani.

After that, to investigate scalability of the solutions at human-scale sizes, a version of all these models was geometrically upscaled by a factor of 12 (excluding cavity widths), resulting in chambers 3 × 3 m in plan, with opaque walls thickened fivefold, to 27.5 cm and slabs to 20 cm, and simulated in the same condition of the small-scale models.

For the real-scale models, a parametric inquiry was performed taking into account (a) the version non-equipped of the model no-equipped with the solar gain cavity; (b) a version equipped with it; (c) a version equipped with it and featuring a ventilation cavity with area of the openings increased four times; (d) a version of both the bare and equipped versions utilizing a 5.5 cm thick wall in place of the 27.5 thick one; (e) a version of both models featuring an enclosure in grey-painted 1 mm thick aluminium sheet in place of bricks; (f) and a version of models (a) (b) and (d) enclosed with low-e double glazing rather than with the air-permeable fictitious mesh (in that case, modifying the ventilation net by turning each of the front nodes in a crack 0.3 mm wide and 12 m long), and coupled with a zone controller featuring an all-convective ideal cooling plant with power of 3000 kWh and setpoint about 24 °C.

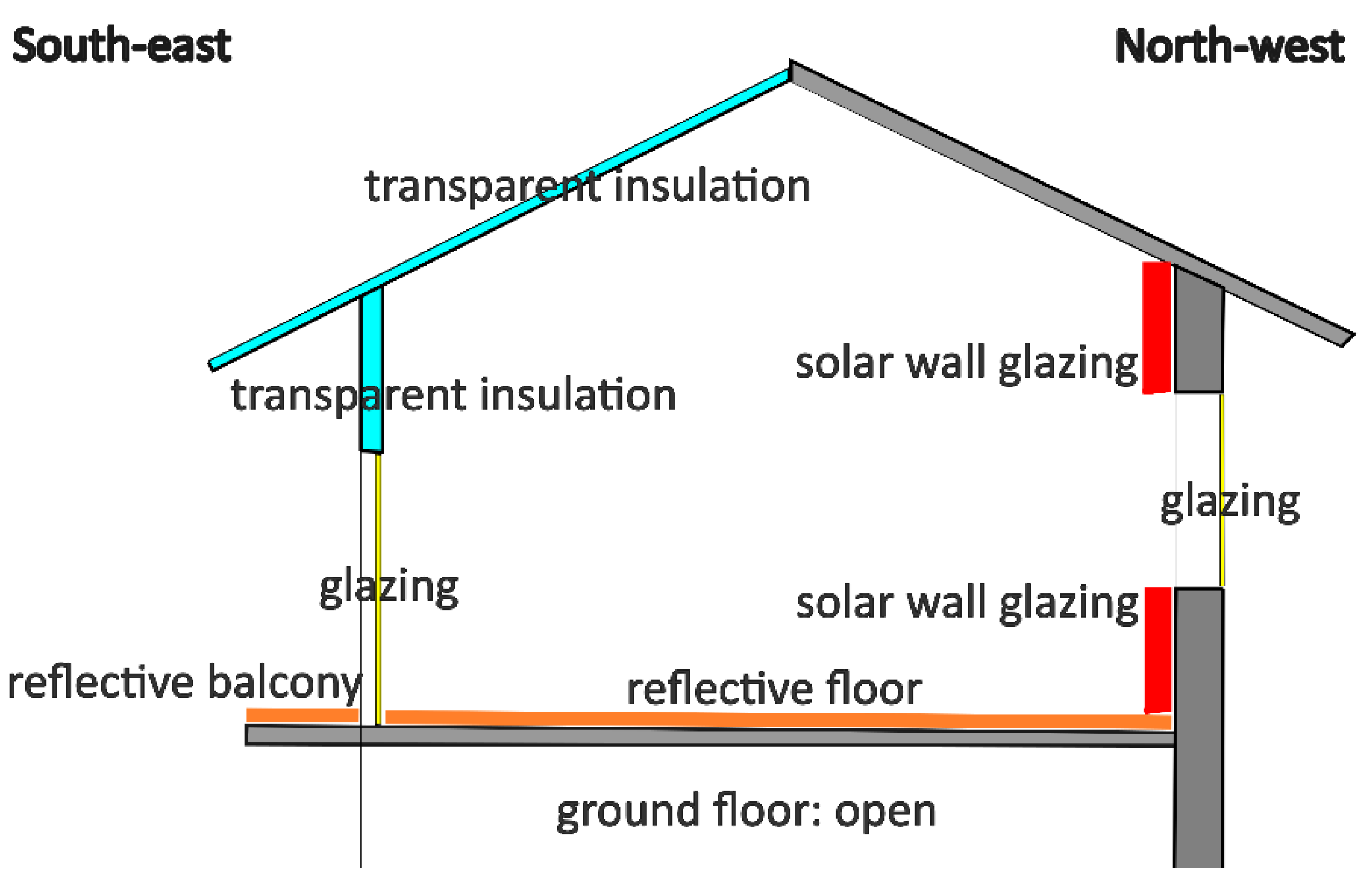

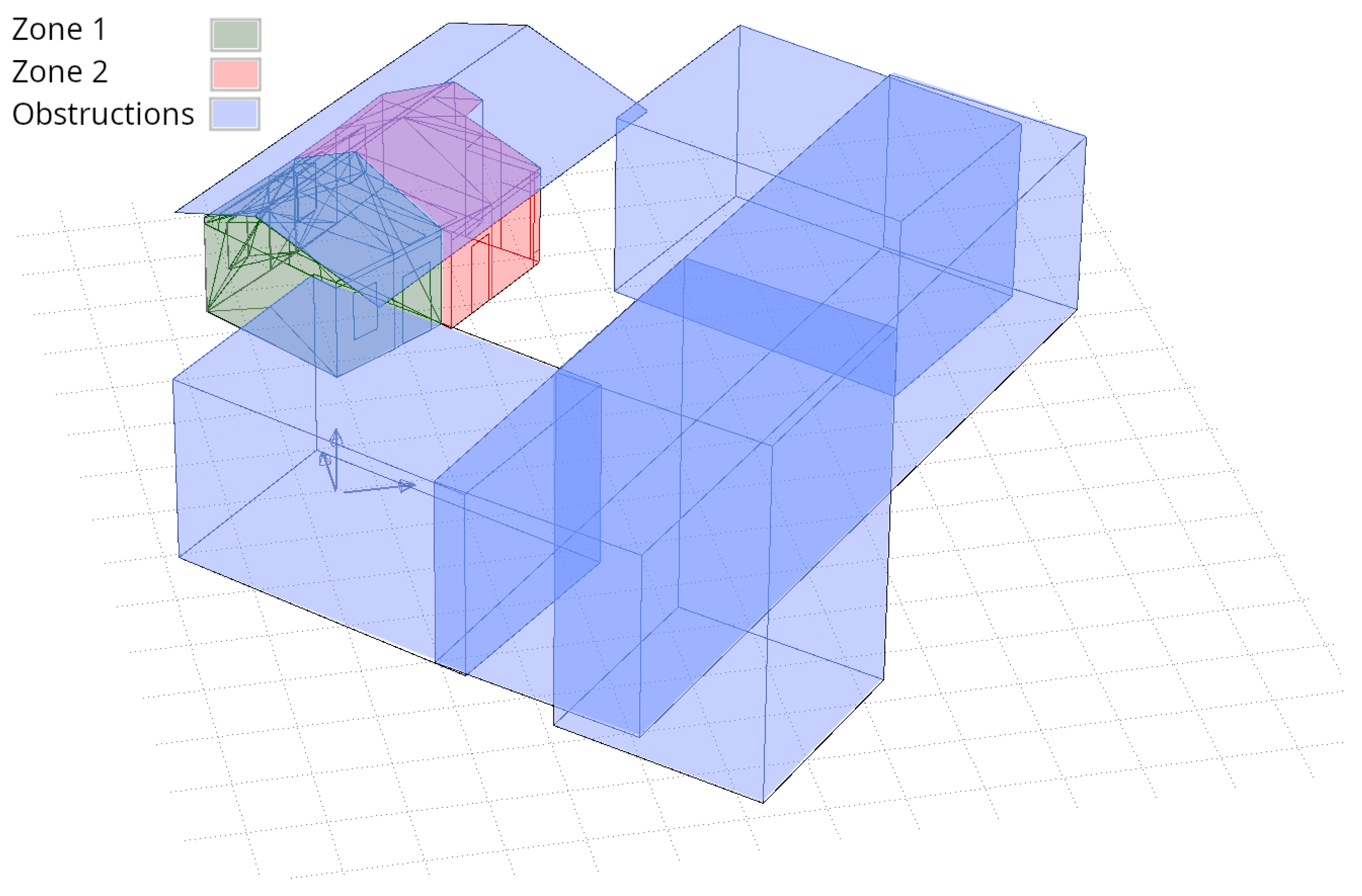

2.2. Case Study Simulations

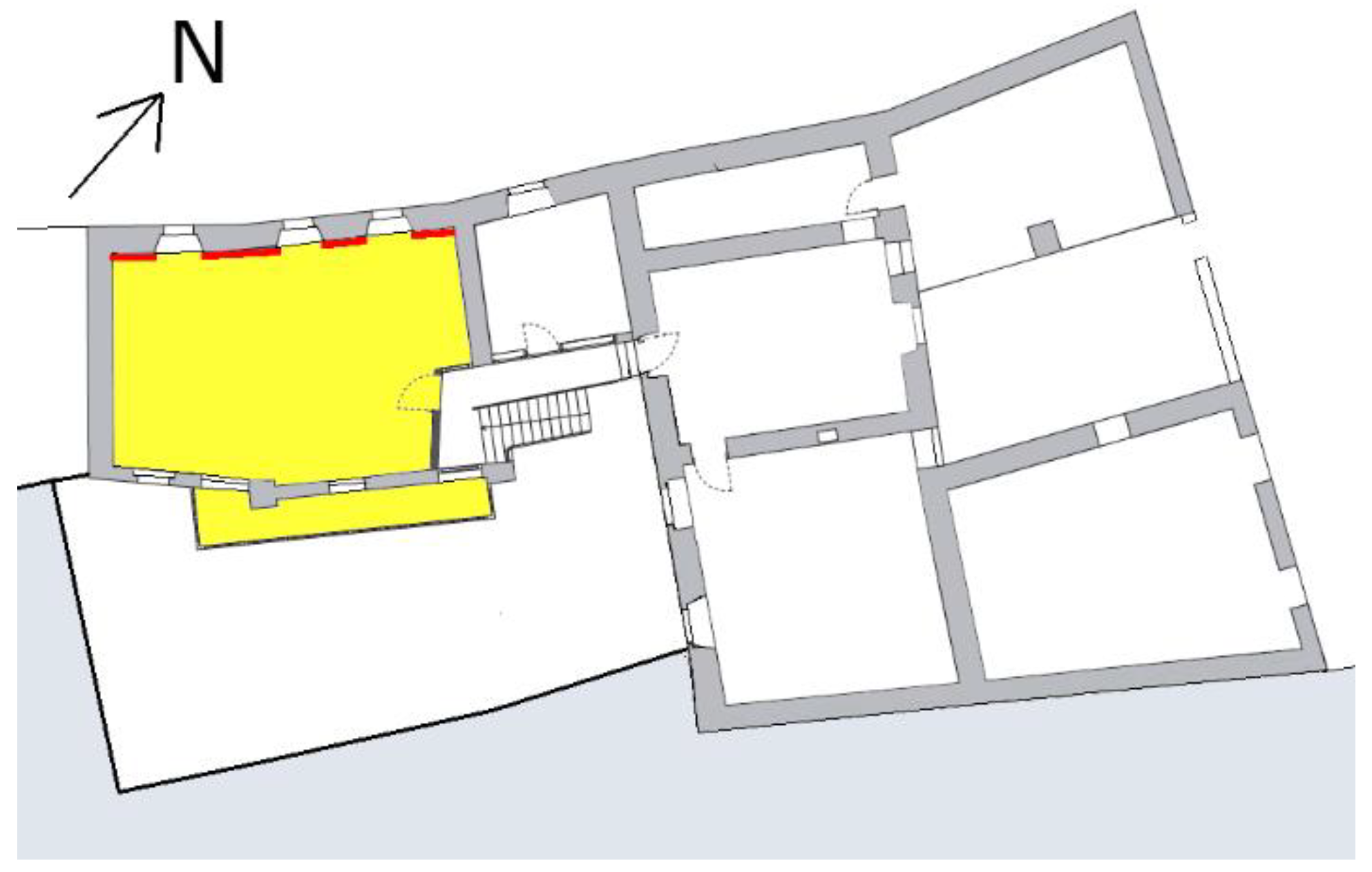

A real-world retrofit case was also modelled to verify the usefulness of the technological solution in action. The case was that of a room in a building in Malnate, near Varese, Lombardy, Italy (latitude 45.79°N), which hosted in time multiple retrofit-oriented graduate design–build workshops by the authors (Brunetti, 2023), and was subject to retrofit requests by the owning environmentalist association (Legambiente Varese). The room is at the level above ground, topping a void and having very limited adjacencies, faces a courtyard that partially obstructs solar radiation, especially during winter, and has a balcony towards the courtyard. The complex layout is rotated about 40° counterclockwise from due south, resulting in the target room facing southeast and northwest (

Figure 9).

The room's enclosure includes load-bearing mixed masonry (of stone and brick) on three sides, and a thinner, non-load-bearing single-brick wall on the southeast side. The uninsulated roof consists of timber decking and rafters covered by tiles. Existing overhangs and relatively narrow windows create low daylight levels, conflicting with the planned use of the space as a multi-purpose room for meetings and leisure.

The building geometry - highly irregular - was modelled with high fidelity based on a physical survey. The model was divided into two thermal zones (north and south halves of the room), separated by a fictitious air partition (

Figure 10). A constant ventilation rate of 10 air changes per hour was imposed in the room. And in the model featuring a reverse Trombe wall, a mass-flow network modelled for the solar wall cavity was modelled with criteria similar to those adopted for the prototypes, imposing an amount of openings at the top and and bottom of the wall corresponding to overall 1/100 of the surface area of the wall itself . Window openings were assumed 30% open from May to October and closed otherwise. Nearby courtyard buildings were included as solar obstructions.

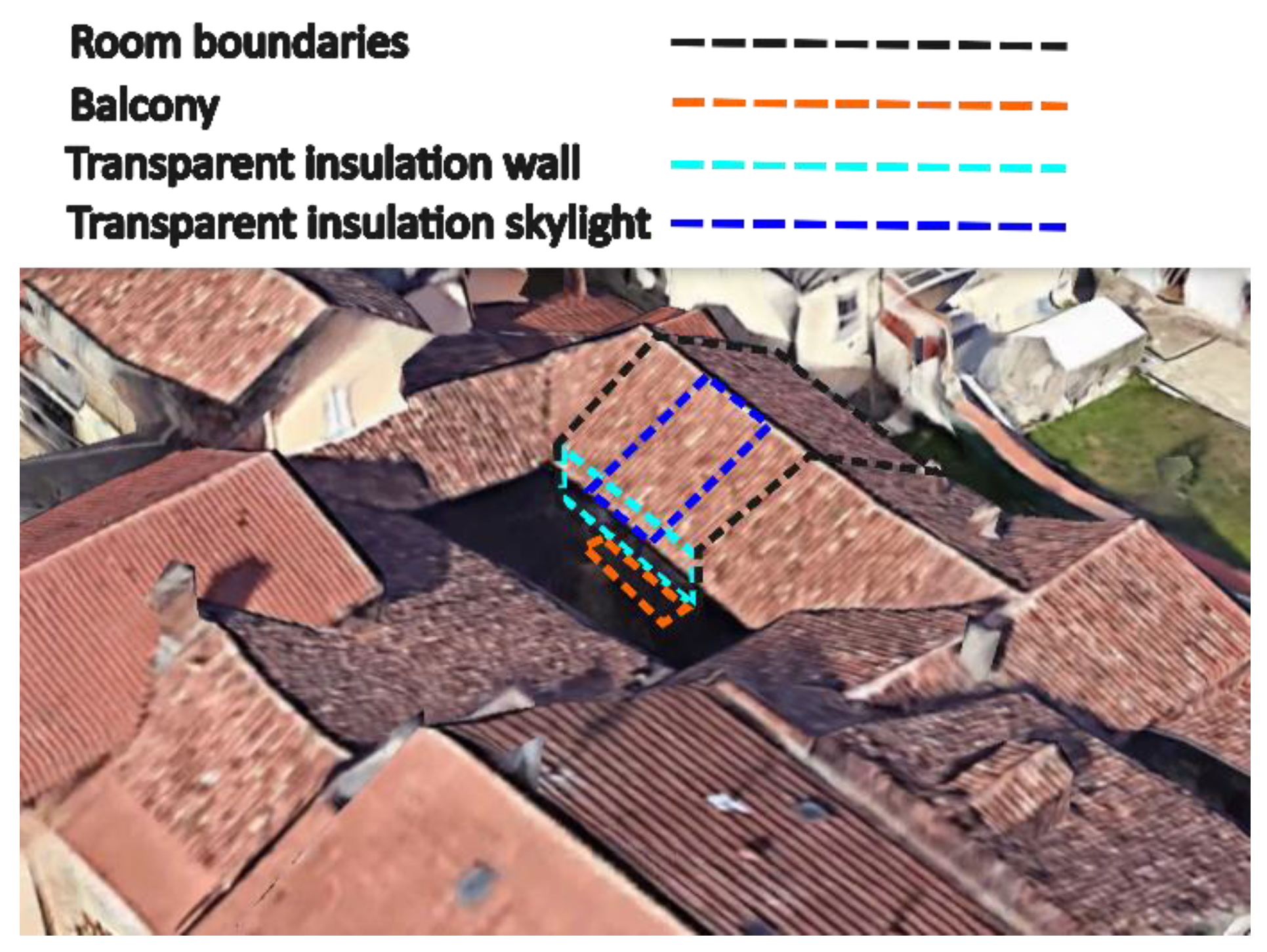

The goal was to evaluate how the proposed reverse solar wall system could enable higher daylighting levels without overheating. Three overlapping daylighting enhancement strategies were tested: (a) increasing floor reflectivity from ~0.5 (bare wood) to ~0.8 (white finish); (b) replacing the southeast masonry wall with a translucent multiwall polycarbonate panel; (c) installing translucent skylights on 50% of the southeast-facing roof slopes. Correspondingly, four retrofit cases were modelled: (a) baseline geometry with 50% floor reflectivity; (b) case a + white flooring; (c) case b + southeast wall replaced with multi-wall polycarbonate panels (U-value: 1.18 W/m²·K; solar transmittance: 0.70); (d) case c + 50% southeast-facing roof replaced by multi-wall polycarbonate panels (

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13).

Figure 11.

View from east, created with Google Earth, showing the balcony, the position of the transparent insulation wall set to replace the thin masonry layer towards south-east, and the position of the skylight set to be created on the roof.

Figure 11.

View from east, created with Google Earth, showing the balcony, the position of the transparent insulation wall set to replace the thin masonry layer towards south-east, and the position of the skylight set to be created on the roof.

Figure 12.

Plan of the first floor showing the position of the room in question (in yellow) and of the reverse solar wall in it (in red).

Figure 12.

Plan of the first floor showing the position of the room in question (in yellow) and of the reverse solar wall in it (in red).

Figure 13.

Transversal section of the room, featuring the retrofit actions.

Figure 13.

Transversal section of the room, featuring the retrofit actions.

Figure 14.

Retrofit actions and modelling decisions highlighted in the ESP-r model.

Figure 14.

Retrofit actions and modelling decisions highlighted in the ESP-r model.

Each case was combined with five internal wall configurations on the northeast-facing side: 1. uninsulated masonry; 2. interior 12 cm hempcrete insulation; 3. interior triple layer polycarbonate lass cladding (U-value 1.959 W/m²·K; 1 cm cavity).

In configuration (3), the passive solar gain cavities were modelled as separate 2 mm-thick thermal zones. No air flow of the cavity was taken into account, since the local preservation norms for historical buildings prevented the possibility of intervening by creating perforations on the north-west facade.

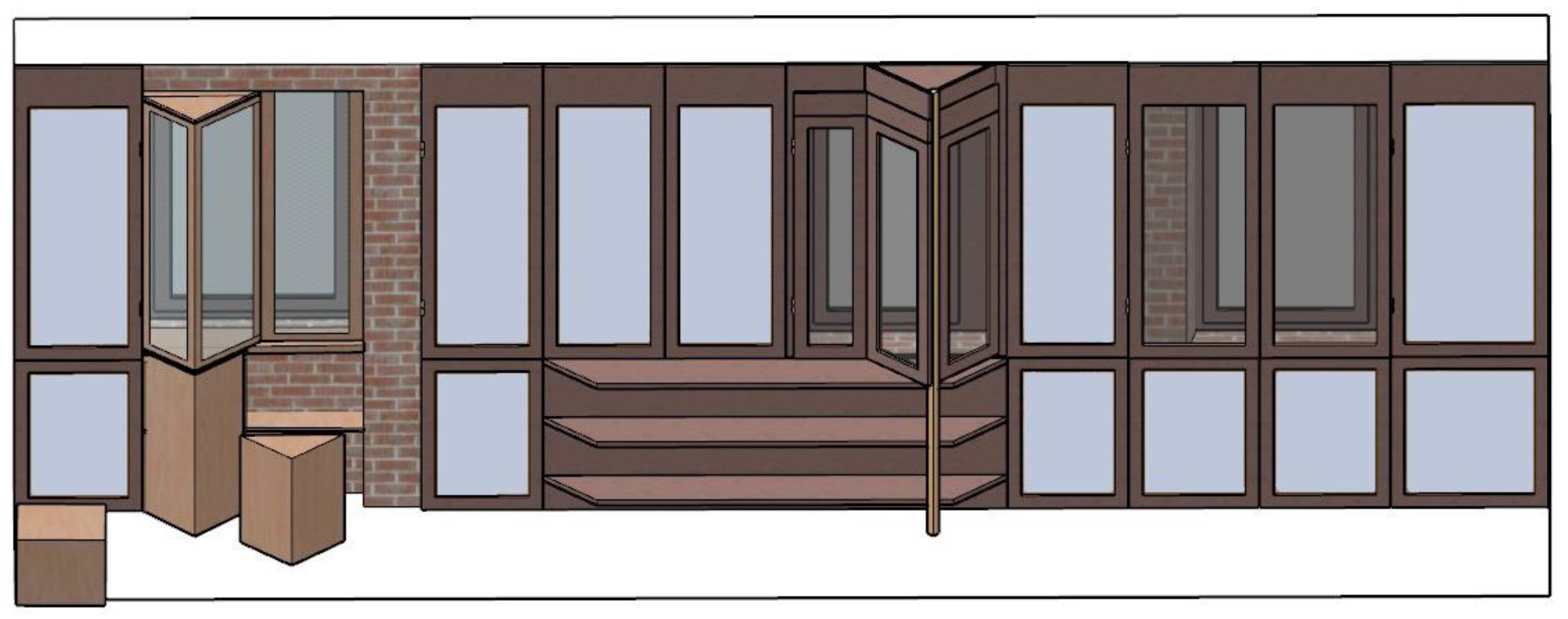

In this real-case scenario, the inverse solar wall has been planned to be realized by applying recycled double-panel windows on the wall (

Figure 15), or multi-wall polycarbonate panels.

The models and datasets of both parts of this study are freely available for consultation on the web [

30].

3. Results

In the following subsections, the results pertaining to the prototypes and those pertaining to the real-word models will be presented separately.

3.1. Results Linked to the Prototypes

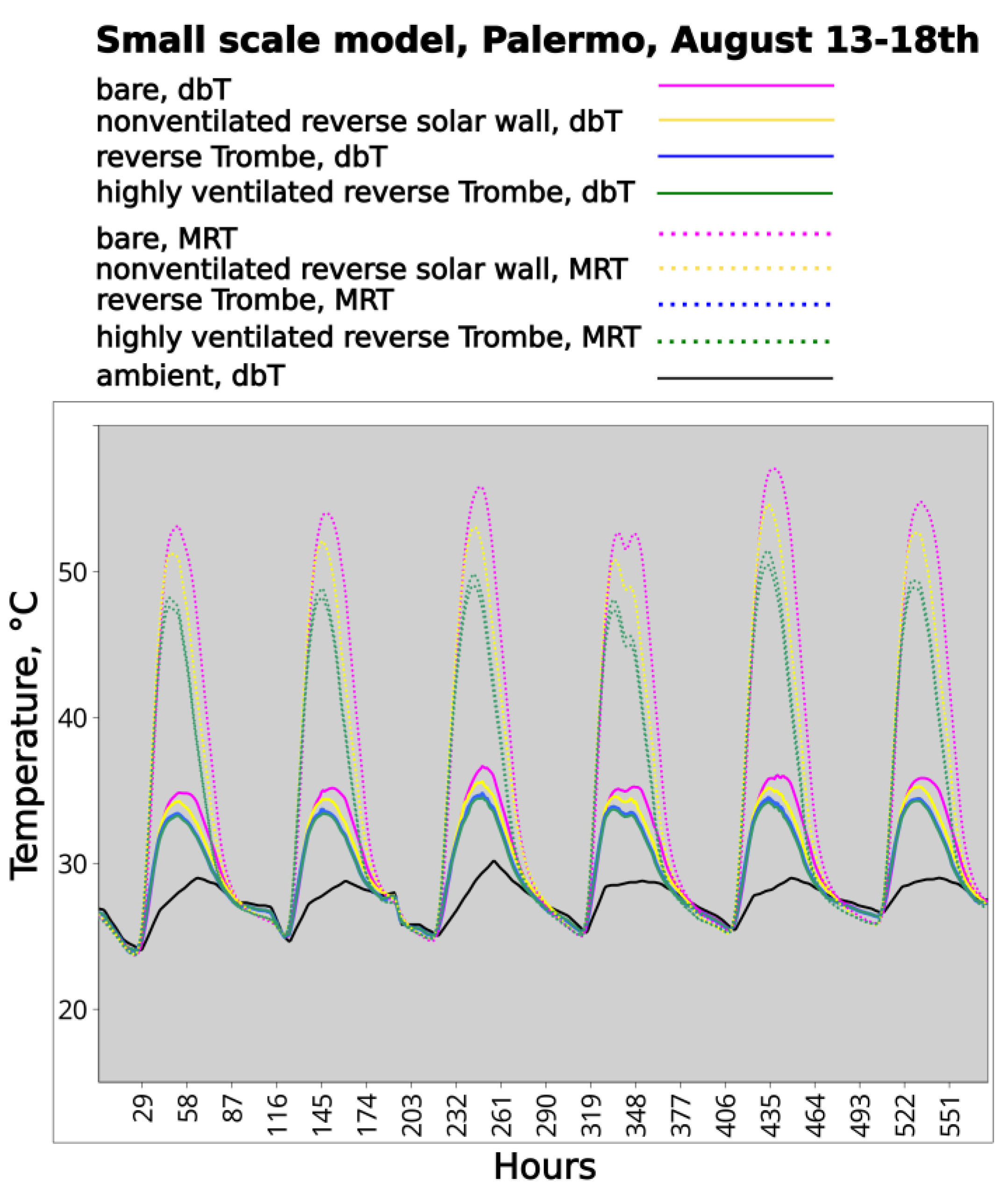

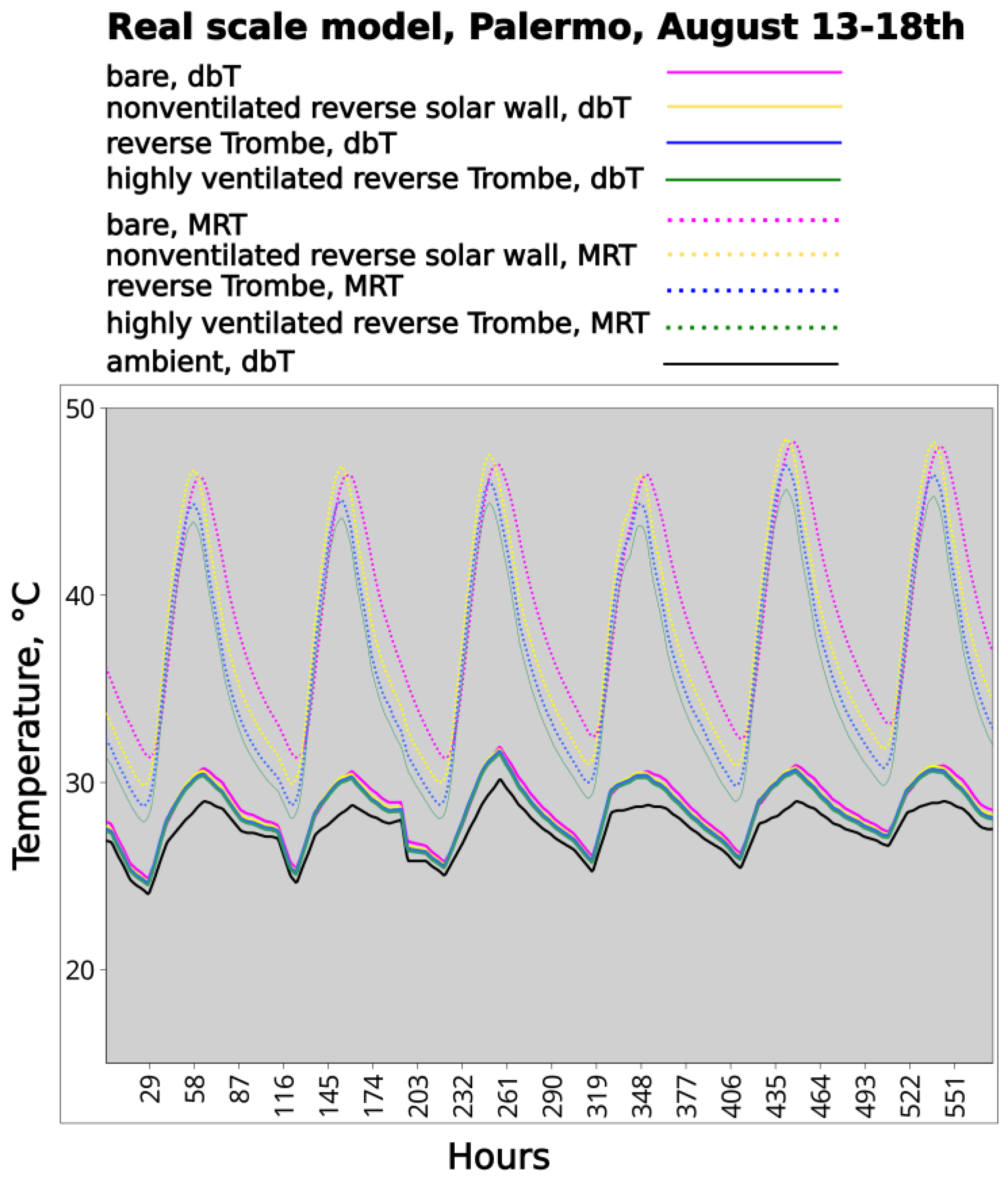

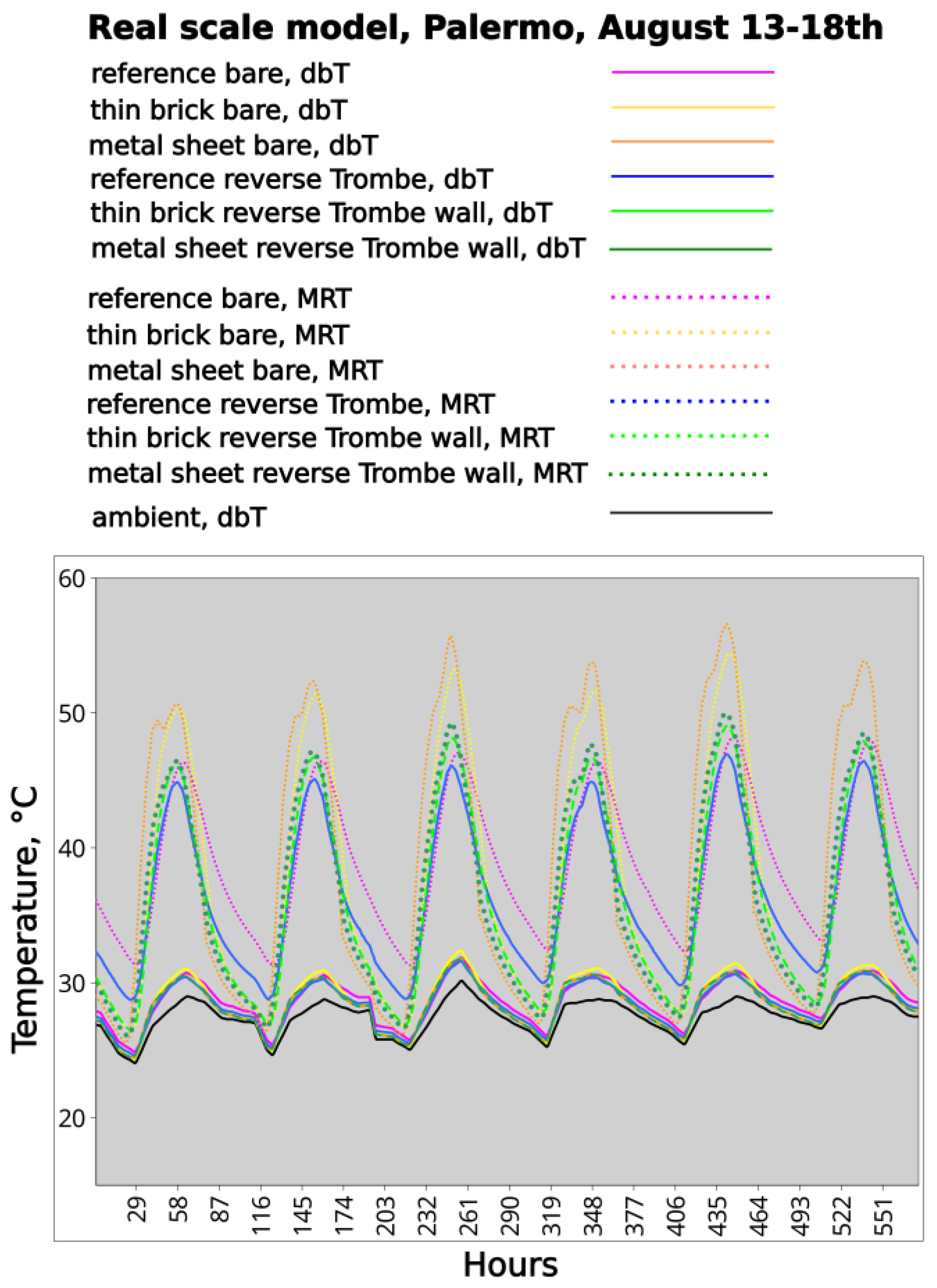

Monitoring of the simulated chambers showed that, in all tested configurations, the solutions featuring the reverse solar wall reduced indoor air temperatures relative to the reference chambers, confirming the findings monitored in the concrete prototypes, used to validate the simulation models: the temperatures obtained when the cavity was ventilated toward the exterior, in the configuration analogous to the reverse Trombe wall, were always cooler than the temperatures. This was true both for the small-scale models (

Figure 16,

Figure 17) and for the real-scale models (

Figure 18). The simulations also indicated that the relative benefit was even greater in terms of mean radiant temperatures. Also, they showed that increasing the size of the ventilation openings in the cavity increased the advantage of the reverse Trombe wall solution.

Once determined that the small-scale model and the real-scale one had grossly similar behaviours despite the fact that many thermal phenomena related to buoyancy-driven convection and radiation do not scale linearly, further investigations focussed on the real-scale models

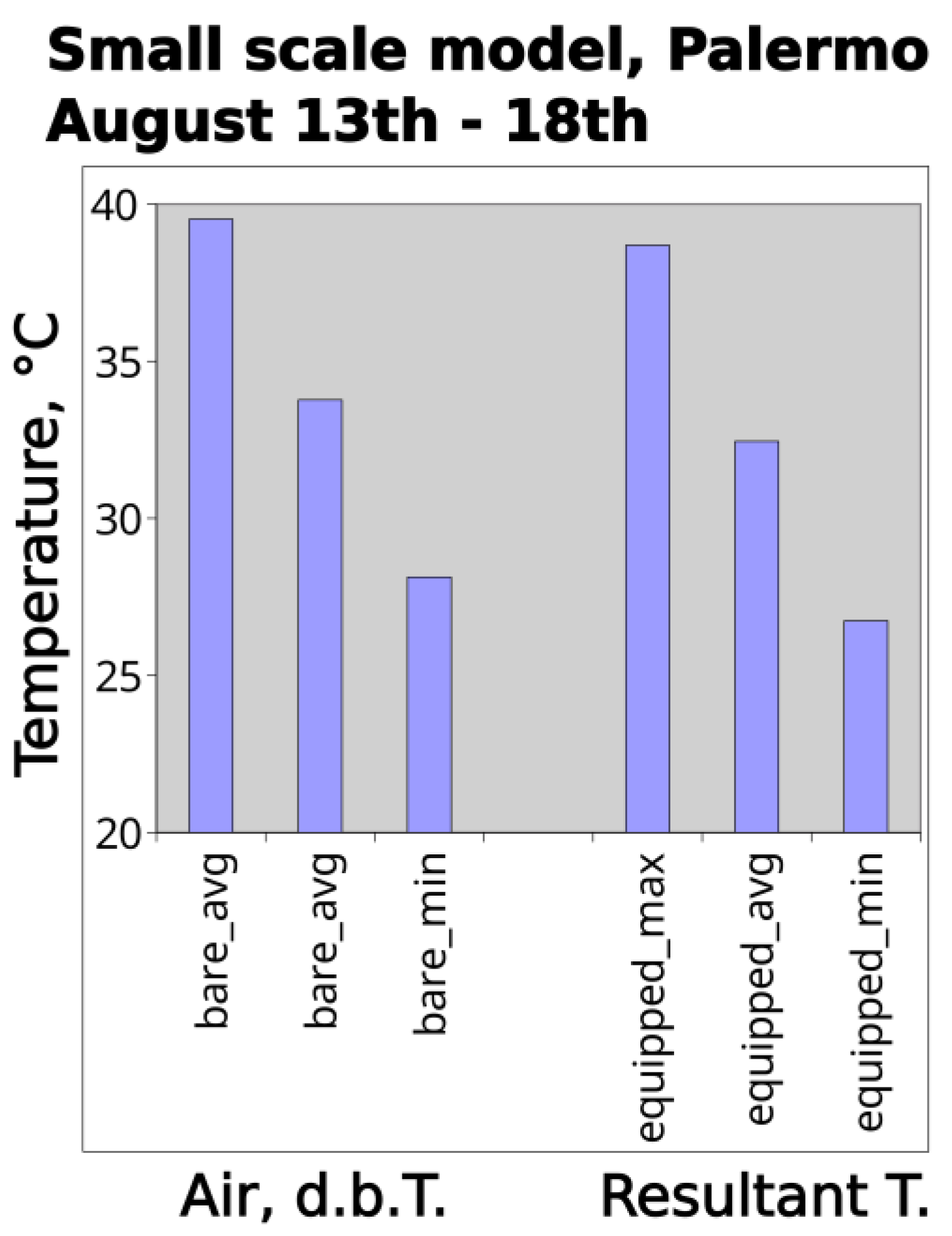

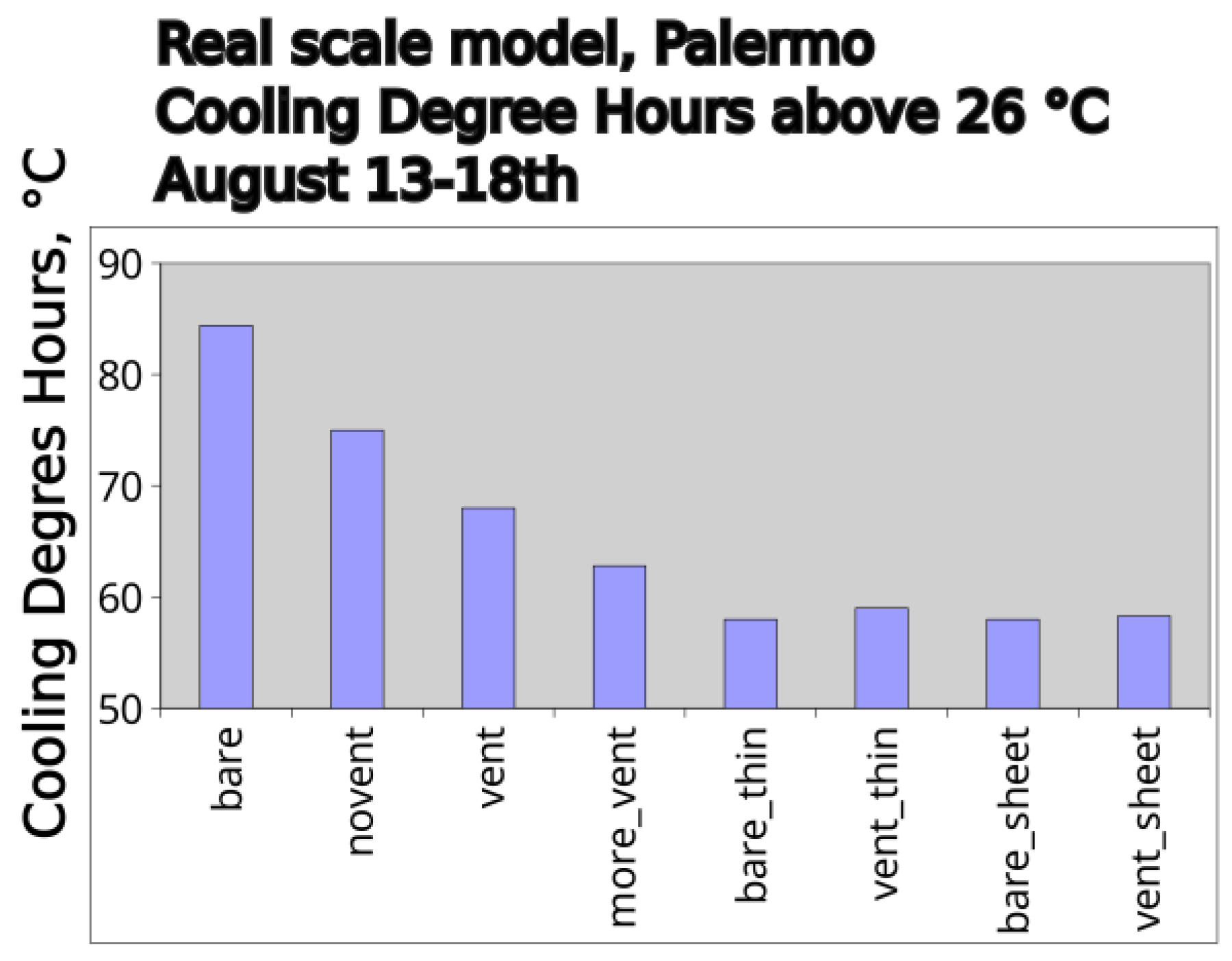

Across the monitored August period, the chambers equipped with the reverse solar wall showed peak temperatures regularly more than 1 °C lower than that in the reference chamber. This benefit was confirmed by cumulative metrics such as degree-hours above 26 °C (

Figure 19). The only exception occurred when the ventilated chamber itself was fully airtight, where the results of both configurations were virtually identical.

The results also showed that the absence of ventilation in the cavity made the thermal advantage given by the presence of the reverse solar wall null, but did not constitute a thermal disadvantage in the considered situation.

Reducing the thickness of the brick wall from 27.5 cm to 5.5 cm preserved the advantage of the reverse Trombe wall, but reduced it, and a similar outcome was produced by substituting the 27.5 brick wall with the 1-mm thick painted aluminium sheet (

Figure 20).

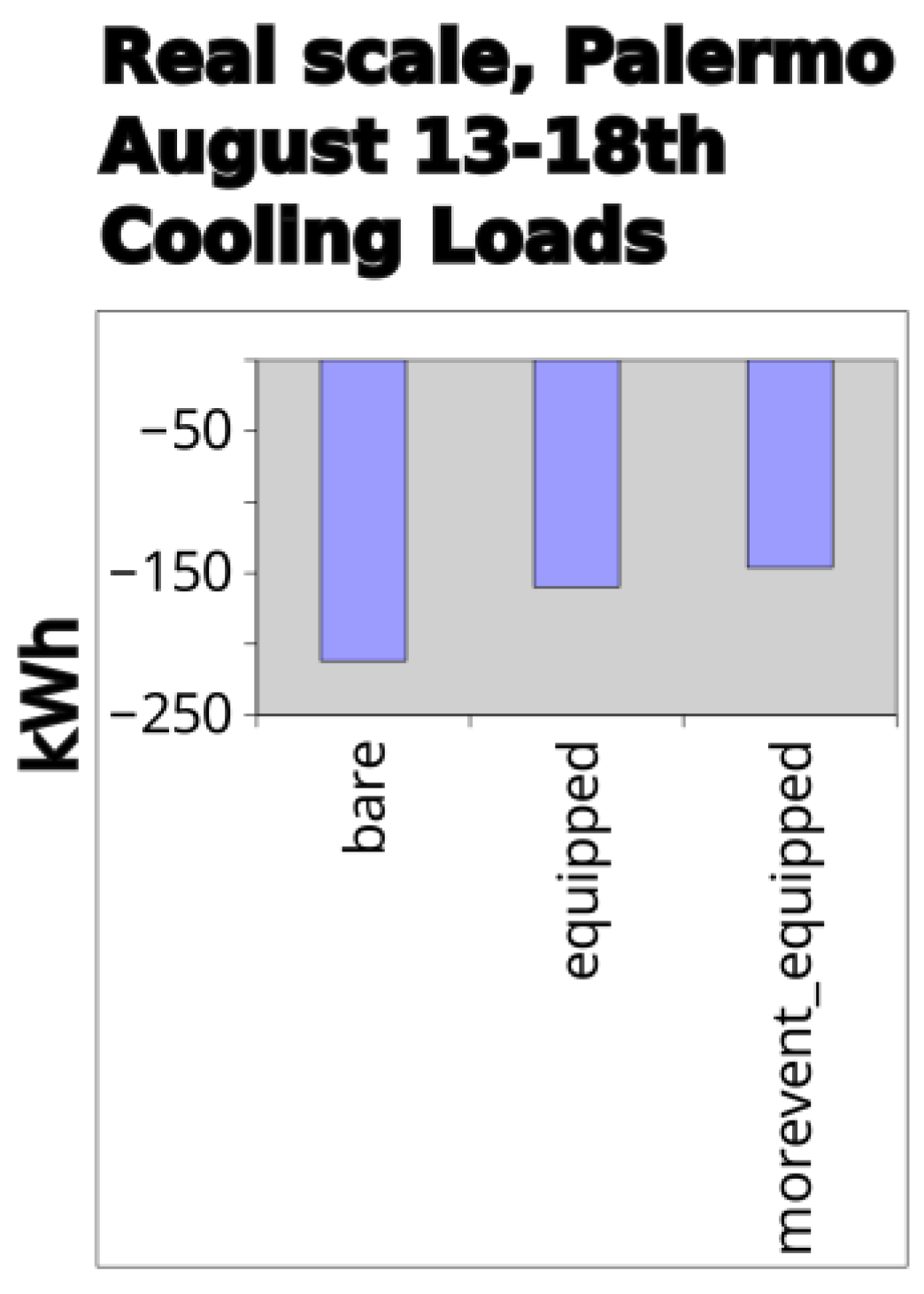

The presence of the reverse solar wall also produced advantages in the case in which the front enclosure of the room, instead of being left open for ventilation, was enclosed with a double low-emissivity glass panel, and cooler with an ideal air-only plant: the related college loads in the considered period were reduced by more than 30% in case of the reverse solar wall, and even more when the size of the cavity ventilation openings was increased (

Figure 21).

The adoption of the reverse solar wall was also advantageous for reducing the cooling loads in the model featuring a double-glass front enclosure, and its advantage increased by increasing the size of the ventilation openings of the reverse passive solar cavity (

Figure 21).

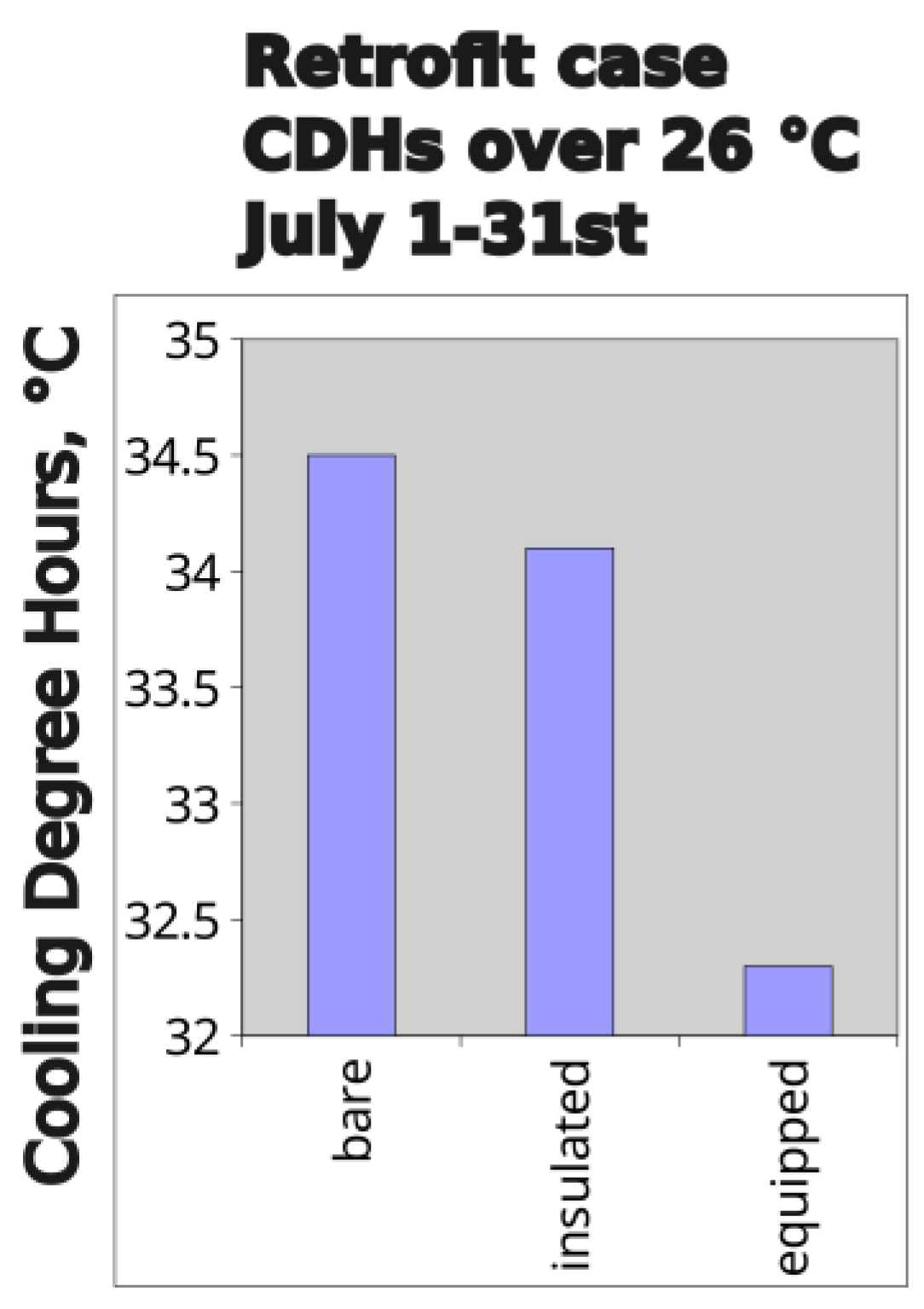

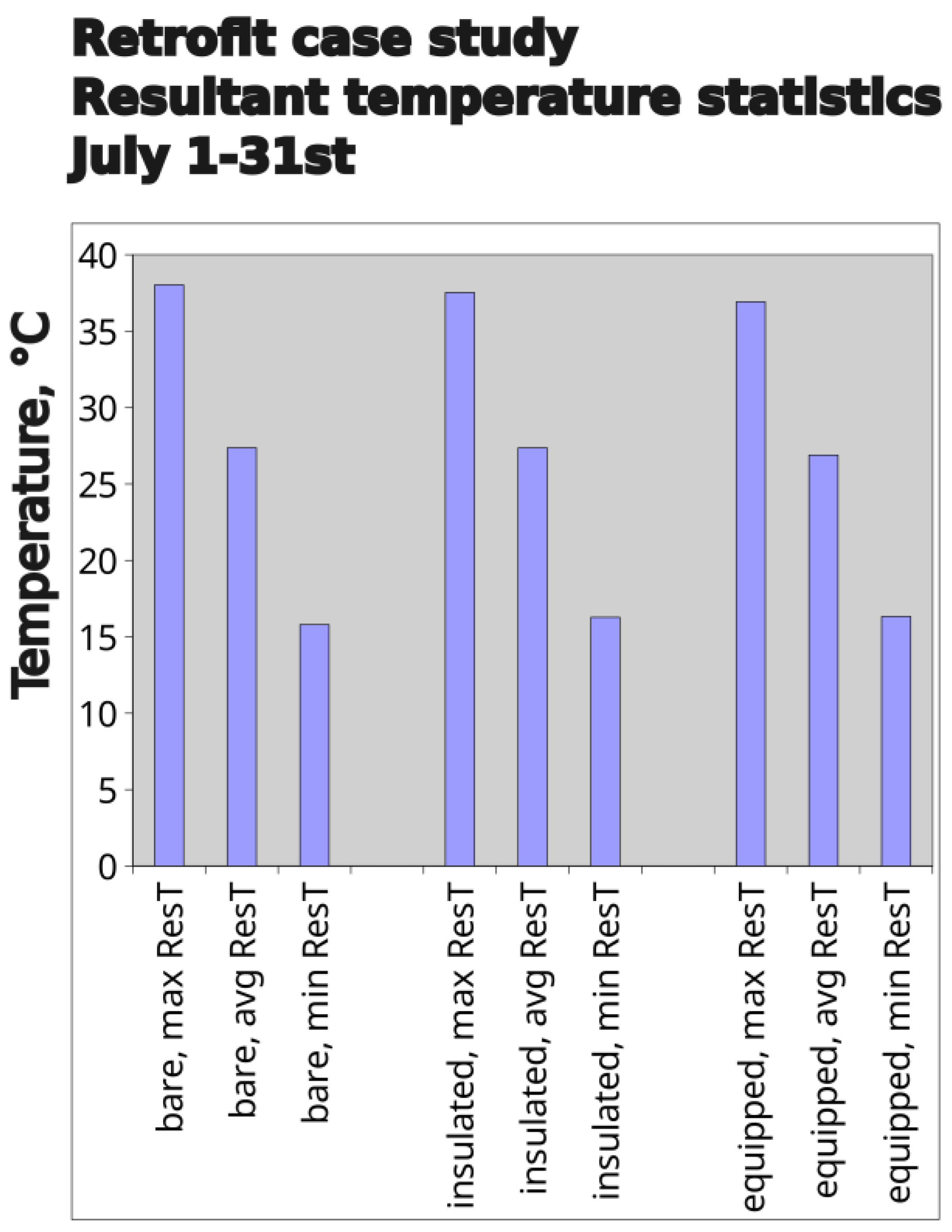

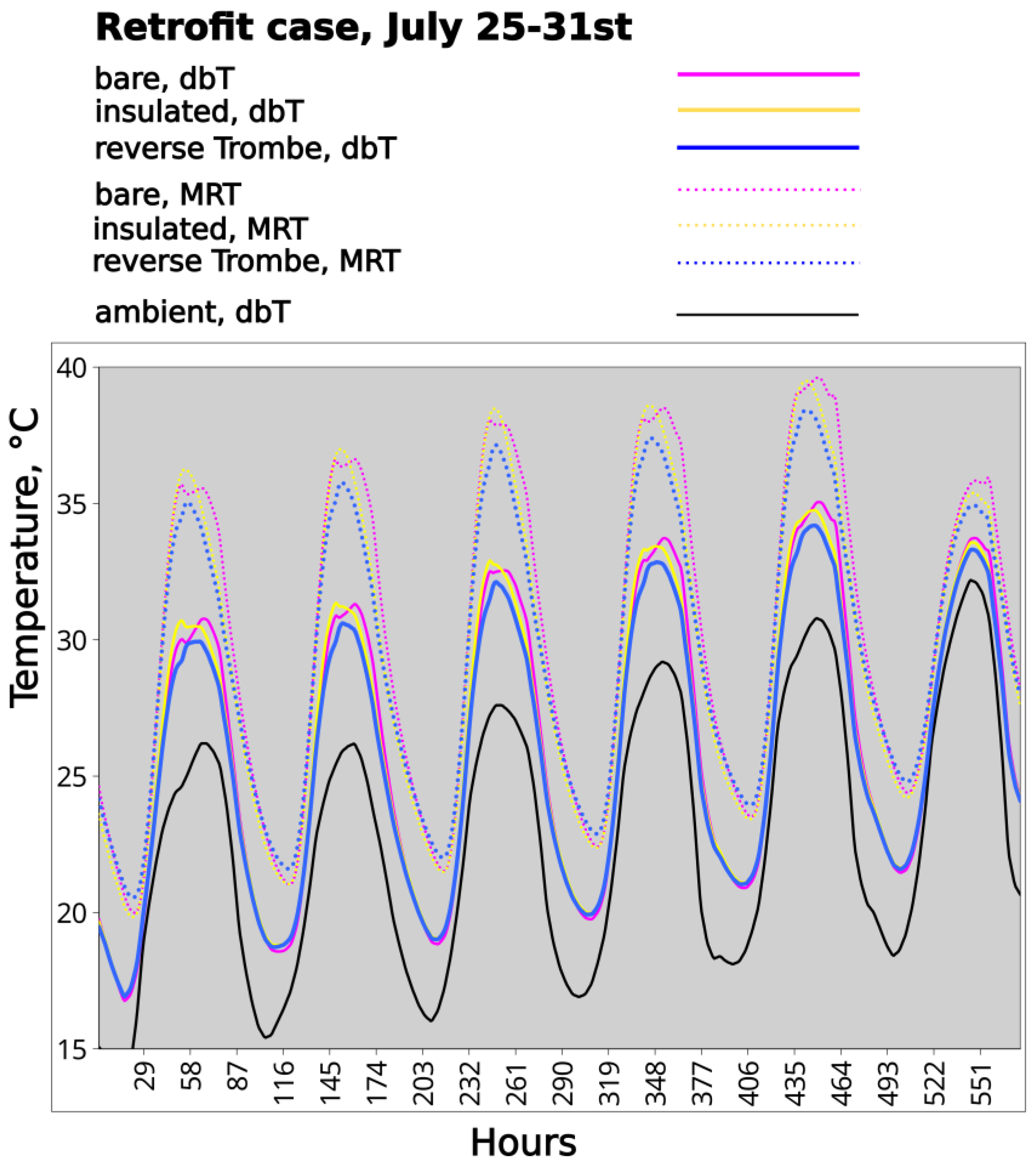

3.2. Results Regarding the Real-Life Case Study

In the real-case retrofit simulations as well, the reverse solar wall produced an appreciable reduction in indoor temperatures, both in terms of reduction of CDHs over 26 °C (

Figure 22) and in terms of average air d.b. temperature and resultant temperatures (

Figure 23), despite the fact that the reverse solar wall cavity was not ventilated. As with the case of the prototypes, the advantage was especially appreciable in terms of MRTs (

Figure 24). The reverse solar wall configuration also produced more advantageous results than the configuration in which the wall was insulated at the inside face, which exhibited a higher thermal responsiveness, and consequently larger thermal swings, even compared to the bare configuration, in which the thermal mass was left exposed indoors.

4. Discussion

The monitoring results, together with the simulations on both the scale models and the enlarged prototype, as well as the real case retrofit scenario, consistently demonstrated that the reverse solar wall configuration can lower indoor temperatures in summer conditions when solar access is desirable for any reason. This applies both to air dry-bulb temperatures and, even more distinctly, to mean radiant and resultant temperatures. They also showed that the benefit is increased when ventilation is increased. In this trials, the ventilation was increased by increasing the size of the inlet and the outlets, but it is presumable that the ventilation rate, and the heat-purging effect of the ventilation itself with it, could be also increased by increasing the height of the stack, and therefore the tallness of the ventilation cavity.

For this heat-purging effect to appear, adequate solar access to the reverse solar wall is required. Such access may be provided either by direct beam radiation or by reflected radiation, as in both the prototypes and case-study models, where beam radiation is reflected on the pavement of clear colour. In other words, the solution is only effective in spaces that receive a more than moderate level of solar radiation. This is demonstrated by the negligibility of the effect in the case of the case-study model when the solar access was not increased and the floor were not highly reflective colour (Figure …).

The addition of the reverse solar wall had beneficial effect to avoid overheating when the enclosing wall was thin and conductive, highly reducing mean radiant temperatures bringing them to levels which are in a rage typical of more highly performing arrangements, like brick walls (Figure …), and when the wall masonry but very thin a pure of mass for thermal inertia (Figure ). This suggests the usability of the solution for extreme low-cost scenarios in informal settlements whose dwellings are enclosed y thin sheet. The fact that the solution works with low-cost enclosures like thin polyethylene films, like the ones utilized in the trials, is sited to the low-cost scenario.

The fact that the advantage is confirmed when thermal loads are measured in case of air conditioning suggests the usability of the technique not only in passive solutions, but also in hybrid ones.

The real-case scenario shows a practical possibility of application of this technique (Figure .). The trials were orientated towards the summer season, but could also be adapted to the winter season, by closing the ventilation openings and protecting the solar gain wall from solar gain, by coupling it with a removable thermal curtain, which would contribute to decreasing the overall thermal transmittance of the enclosure and prevent the heat loss effect due to solar gain in the wall.

The necessity of adding the ventilation to the solar wall has showed to produced different levels of advantage depending on the problem context. The advantage of the cavity in the unventilated case, seen in the mean radiant temperatures, is present in the small-scale model, negligible in the real-case model, and present in the real case-study, and this suggests that in case of absence of ventilation in the cavity, the wall thickness required sizing taking into account the thermal delay of the wall, to be attentive checked and designed means of dynamic thermal simulations, in complete analogy with a massive solar wall.

The absence of this technique in the literature can be explained by a combination of contextual constraints. First, although the solution improves overheating avoidance, it relies on substantial solar access - a condition that is generally avoided in situations where overheating risk is high. Therefore, its relevance is limited to scenarios where high daylight levels generated by direct or reflected beam radiation are required in warm or hot situations (e.g., libraries, conference rooms, living rooms, or precision-work spaces such as drawing offices), which is something which is foreign to many traditional cultures residing in hot and warm climates [

31] (Oliver, 1987). Second, for the technique to work, the wall in question must face roughly toward the equator, ideally within ±30–45° [

32], and must also face the outside directly. Third, the thermal advantage deriving from the solution, while significant, is not dramatic. Therefore, the solution is only reasonable if the investment cost is low. Fourth, the building must include either an existing massive wall with no external insulation, or a wall where the transparent cladding itself provides adequate insulation and where solar gain in the cavity is prevented (for example, as said, by covering the glazing enclosure of the solar wall with seasonal thermal curtains) - otherwise the winter performance could be negatively affected. Fifth, the technique makes only sense in rooms which are well ventilated, suited to avoid indoor heat buildup.

Considering these considerations, the most promising application appears to be low-cost, seasonal reverse solar walls constituted by multiple layers of low-cost thin polyethylene films stretched in the massive part of an uninsulated wall, massive or non-massive, the inside face of which is reasonably sun-bathed (by direct exposure or by reflection of beam radiation), in buildings located in climates with hot summers. And this possibility is subordinated to the fact that the interior space is shallow enough (ideally less than ~5 m in depth) to permit solar access to the wall in question. In such cases, the technique can reduce both air and radiant temperatures in rooms where high solar admission is required: a situation generally left unaddressed by traditional bioclimatic strategies, which rely almost exclusively on solar exclusion to prevent overheating.

As this is, the intent is not to quantify all possible design parameter variations, but to identify a general direction. It is not by chance that, in this study, the idea of the reverse solar wall emerged from the retrofit real-world case, and only subsequently was tested through the prototypes, rather than the other way around.

Several limitations of this study should certainly be acknowledged. First, the small-scale prototypes necessarily involve thin walls, and therefore do not fully capture the transient thermal dynamics of a full-scale wall. Conduction and convection processes do not scale linearly, limiting full representativeness of the small-scale prototypes. Second, the real-scale and retrofit cases have so far only been explored through simulations, with calibration limited to small-scale case. Finally, this work, as a proof-of-concept study, has not included a systematic parametric study, which is deferred to future research. As such, its intent has not been to quantify all possible design parameter variations, but to identify a general technical design direction. It is not by chance that, in this study, the idea of the reverse solar wall emerged originally from the retrofit real-world case, and only subsequently was tested through the prototypes, rather than the other way around.

Nevertheless, the results clearly point toward further promising developments beyond the accelerated ones. The first is that it is possible that a greater advantage could be achieved by concentrating incoming solar radiation onto a reverse solar wall - for example, through reflectors collecting light from a wider area, and by incorporating such devices architecturally, as part of “super-lit” elements (light wells, reverberating surfaces, etc.), in indoors situations where it is desirable to make daylight less thermally “expensive”.

Secondly, performance advantage improvements may be obtained by incorporating performance improvements which are typical in passive solar walls. One of these is finishing the massive side of solar walls with low-emissivity linings. Another is completing the transparent enclosure of the cavity of reverse passive solar walls with transparent insulation (this may make the solution work both in the case in which the cavity is ventilated and in the case in which it isn’t). And one more possible solution is substituting the massive, solid part of the wall [

34] with a water wall, for increased thermal inertia and increased conductive responsiveness.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the simple, yet previously unexplored [

33], idea of using a passive solar device - the solar wall - to

remove heat from a room instead of supplying it, turning it into a device that could be defined a reverse solar wall. The proposed solution is not one of the overheating avoidance solutions existing for solar walls - it is not a solution for limiting the tendency of a solar wall to transmit heat indoors in summer - but a true, although moderate, cooling strategy aimed to reduce the heat gained indoors on wall that for some reasons are required to receive full beam radiation - direct or reflected - indoors.

By reversing the conventional direction of heat transfer, the proposed configuration contrasts both with the dominant focus of contemporary passive-solar experimentation and with traditional bioclimatic strategies, which typically aim to reduce overheating by limiting solar admission.

Because the solar wall is here used in a reversed way, the applicability of the solution is necessarily more limited than that of standard solar walls, because it is restricted to indoor spaces that combine: (a) significant potential exposure to solar radiation, (b) a limited thickness (to ensure solar access to the wall), and (c) a need to maintain high daylight levels in warm or hot climates - i.e., situations where reducing solar access in order to cool the space would bring more disadvantages (e.g. insufficient daylight) than benefits.

The results from monitoring the small-scale prototypes and from the simulations of both theoretical and real-case models confirm that the technique in question provides a measurable thermal benefit in the hot season. Although the reductions in indoor temperature are not dramatic, they are robust and consistent, which suggests that further performance gains may be achievable through targeted optimizations, like concentrating incident solar radiation onto the reverse solar wall using reflectors or other optical devices, and/or utilizing transparent superinsulation in the solar wall enclosure.

6. Acknowledgements

With regards to the prototype-based case, I wish to thank my dear wife Marcella who, without complaining, accepted that I spent my mornings in the beautiful summer of Trapani trafficking on a rooftop with my prototype samples, rather than on a beach.

With regards to the real-world case study, I would like to dedicate it with moved commotion to the memory of Alberto Minazzi, Architect, who has been for many years the heart of the group of volunteers who made the magic situation of self-directed, self-built, experimental, environmental-friendly reuse of the “Casamatta” building in Malnate possible. Dear Alberto, thank you for everything. You are sorely missed by many, and your example will serve generations.

References

- McCullagh, The Solar Greenhouse Book, Rodale Press, Emmaus, Pennsylvania, 1978.

- Shapiro, A.M. The Homeowner's Complete Handbook for Add-On Solar Greenhouses and Sunspaces: Planning, Design, Construction, Rodale Press, Emmaus, Pennsylvania, 1984.

- Gustavsen, A.; Griffith, B.T.; Arasteh, D. Natural Convection Effects in Three-Dimensional Window Frames with Internal Cavities, ASHRAE Transactions, 107 (2), 2001.

- Z. Hu, W. He, J. Ji, S. Zhang, A review on the application of Trombe wall system in buildings, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 70 , 2017, 976–987. [CrossRef]

- Balcomb, J.D., Editor, Passive Solar Buildings, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1992.

- Saadatian, O.; Sopian, K.; Lim, C.H.; Asim, N.; Sulaiman, M.Y. Trombe walls: A review of opportunities and challenges in research and development, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 16, 8, 2012, 6340-6351. [CrossRef]

- Mazria, E. The Passive Solar Energy Book, Rodale Press, Emmaus, Pennsylvania, 1980.

- Mokni, A.; Lashin, A.; Ammar, M. Mhiri, H. Thermal analysis of a Trombe wall in various climatic conditions: An experimental study, Solar Energy, 243, 2022, 247–263. [CrossRef]

- A. Borodinecs, G. Bebre, D. Bajare, A Review on Trombe Wall Technology Feasibility and Applications, Sustainability, 2023, 15, 3914. [CrossRef]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar engineering of thermal processes, Wiley, New York, 2013.

- Szyszka, J. From Direct Solar Gain to Trombe Wall: An Overview on Past, Present and Future Developments, Energies, 2022, 15, 8956. [CrossRef]

- Michel, J. (1973). Utilisation de l’énergie solaire, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, 167 , 88–96.

- Burek, S.A.M.; Habeb, A. Air flow and thermal efficiency characteristics in solar chimneys and Trombe Walls, Energy and Buildings, 39, 2007, 128–135. [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.S.; Chow, C.C. (2003). Performance of a solar chimney, Solar Energy, 74 (1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- G. Gan, A parametric study of Trombe walls for passive cooling of buildings Energy and Buildings, 27, 1, 1998, 37-43. [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.Y.; Riffat, S.B.; Zhu, J. Review of passive solar heating and cooling technologies, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 14, 2010, 781–789. [CrossRef]

- F. Stazi, A. Mastrucci, C. di Perna, Trombe wall management in summer conditions: An experimental study, Solar Energy, 86 (2012) 2839–2851. [CrossRef]

- Rabani, M.; Kalantar, V.; Dehghan, A.A.; Faghih, A.K. Experimental study of the heating performance of a Trombe wall with a new design, Solar Energy, 118, 2015, 359–374. [CrossRef]

- Dabeh, M.; Elbably, A. Ventilated Trombe wall as a passive solar heating and cooling retrofitting approach; a low-tech design for off-grid settlements in semi-arid climates, Solar Energy, 122, 2015, 820-833. [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Leung, M.K.H.; He, W. Effective use of venetian blind in Trombe wall for solar space conditioning control, Applied Energy, 250, 2019, 452–460. [CrossRef]

- Simões, N.; Manaia, M.; Simões, I. Energy performance of solar and Trombe walls in Mediterranean climates, Energy, 234, 2021, 121197. [CrossRef]

- Kaushika, N.D., Sumathy, S K. olar transparent insulation materials: a review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 7, 2003) 317–35. [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.L.; Eames, P.C. Perera, R.S. A review of transparent insulation systems and the evaluation of payback period for building applications, Solar Energy, 81 (2007) 1058–1071. [CrossRef]

- Świrska-Perkowska, J.; Kucharczyk, A., Wyrwał, J. Energy Efficiency of a Solar Wall with Transparent Insulation in Polish Climatic Conditions, Energies, 13, 2020, 859. [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, M.; Leccese, F.; Tuoni, G. Ventilated facades energy performance in summer cooling of buildings, Solar Energy, 75, 6, 2003, 491-502. [CrossRef]

- Prieto, A.; , Auer, A.; Klein, T. Passive cooling & climate responsive façade design: Exploring the limits of passive cooling strategies to improve the performance of commercial buildings in warm climates, Energy and Buildings, 175, 2018, 30-47. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Song, Y.; Chu, Y. An experimental study of the summer and winter thermal performance of an opaque ventilated facade in cold zone of China, Building and Environment, 218, 2022, 109108. [CrossRef]

- Ibañez-Puy, M.; Vidaurre-Arbizu, M.; Sacristán-Fernández, J.A.; Martín-Gómez, C. Opaque Ventilated Façades: Thermal and energy performance review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 79, 2017, 180-191. [CrossRef]

- Cuce, P.M.; Cuce, E. Ventilated Facades for Low-Carbon Buildings: A Review. Processes, 13, 7, 2025, 2275. [CrossRef]

- Gian Luca Brunetti, 2025 dataset with the models and data for this study, https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/reverse_greenhouse_effect_by_means_of_a_reverse_solar_wall_in_prototypes_in_a_retrofit_case_study_Casamatta_building_in_Malnate_Varese_Italy_featuring_a_reverse_solar_wall_/29975272.

- Oliver, P. Dwellings: The House Across the World, Phaidon Press, London, 1987.

- Dekay, M.; Brown, G.Z. Sun Wind and Light. Architectural Design Strategies, Wiley, New York, 2014.

- Santamouris, M.; Kolokotsa, D. Passive cooling dissipation techniques for buildings and other structures: The state of the art, Energy and Buildings, 57, 2013, 74-94. [CrossRef]

- Hassanain, A.A. Hokam, E.M. Mallick, T.K. Effect of solar storage wall on the passive solar heating constructions, Energy and Buildings, 43, 2011, 737–747. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Dimensions the small-scale prototypes.

Figure 1.

Dimensions the small-scale prototypes.

Figure 2.

Position of the samples on a roof in Trapani seen form the viewpoint of the sun at mid-August at noon. Image created with Google Earth (in which the cast shadows are unrelated from the viewpoint).

Figure 2.

Position of the samples on a roof in Trapani seen form the viewpoint of the sun at mid-August at noon. Image created with Google Earth (in which the cast shadows are unrelated from the viewpoint).

Figure 3.

View of the prototypes on the roof.

Figure 3.

View of the prototypes on the roof.

Figure 4.

Difference between the “bare” model (on the left) and the model adopting the reverse Trombe enclosure (on the right).

Figure 4.

Difference between the “bare” model (on the left) and the model adopting the reverse Trombe enclosure (on the right).

Figure 5.

The small-scale model in ESP-r completed with the solar obstructions which were present on the scene.

Figure 5.

The small-scale model in ESP-r completed with the solar obstructions which were present on the scene.

Figure 6.

The nodes and connections of the ventilation net in the case of the model featuring the inverse Trombe configuration. In blue are the nodes pertaining to the chamber, and in green the nodes pertaining to the inverse solar gain cavity.

Figure 6.

The nodes and connections of the ventilation net in the case of the model featuring the inverse Trombe configuration. In blue are the nodes pertaining to the chamber, and in green the nodes pertaining to the inverse solar gain cavity.

Figure 9.

Bounded in red is the room in its built context, seen from the position of the sun at the summer solstice at noon.

Figure 9.

Bounded in red is the room in its built context, seen from the position of the sun at the summer solstice at noon.

Figure 10.

The thermal zones and solar obstruction in the retrofit case model.

Figure 10.

The thermal zones and solar obstruction in the retrofit case model.

Figure 15.

Architectural hypothesis for retrofitting the back wall with an inner curtain wall enclosing transparent insulation (in grey). Authors: Baixue Fan and Ju Yan. Draft for a graduate thesis, Politecnico di Milano, 2025.

Figure 15.

Architectural hypothesis for retrofitting the back wall with an inner curtain wall enclosing transparent insulation (in grey). Authors: Baixue Fan and Ju Yan. Draft for a graduate thesis, Politecnico di Milano, 2025.

Figure 16.

Temperatures simulated in the small-scale models between August 13th and 18th.

Figure 16.

Temperatures simulated in the small-scale models between August 13th and 18th.

Figure 17.

Temperature statistics between June 1st and August 31st in the small-scale model.

Figure 17.

Temperature statistics between June 1st and August 31st in the small-scale model.

Figure 18.

Temperatures simulated in the real-scale models between August 13th and 18th.

Figure 18.

Temperatures simulated in the real-scale models between August 13th and 18th.

Figure 19.

Cooling Degree Hours (CDHs) above 26 °C predicted in the various cases in the real-scale models.

Figure 19.

Cooling Degree Hours (CDHs) above 26 °C predicted in the various cases in the real-scale models.

Figure 20.

Temperatures in the real-scale “bare” models and the models featuring the reverse Trombe wall in the case in which a thin (5.5 cm) brick wall is adopted in place of the massive one, and when and painted aluminium sheet is adopted.

Figure 20.

Temperatures in the real-scale “bare” models and the models featuring the reverse Trombe wall in the case in which a thin (5.5 cm) brick wall is adopted in place of the massive one, and when and painted aluminium sheet is adopted.

Figure 21.

Cooling loads between August 13-18th in different retrofit scenarios. The option “morevent_equipped” features ventilation openings of the reverse solar cavity increased fourfold.

Figure 21.

Cooling loads between August 13-18th in different retrofit scenarios. The option “morevent_equipped” features ventilation openings of the reverse solar cavity increased fourfold.

Figure 22.

Cooling Degree Hours (CDHs) over 26 °C of the three tested configurations of the retrofit case in July.

Figure 22.

Cooling Degree Hours (CDHs) over 26 °C of the three tested configurations of the retrofit case in July.

Figure 23.

Resultant temperatures statistics relative to July of the retrofit options.

Figure 23.

Resultant temperatures statistics relative to July of the retrofit options.

Figure 24.

Free-floating temperatures of the retrofit options between July 25th and 31st.

Figure 24.

Free-floating temperatures of the retrofit options between July 25th and 31st.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).