Submitted:

06 December 2023

Posted:

08 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

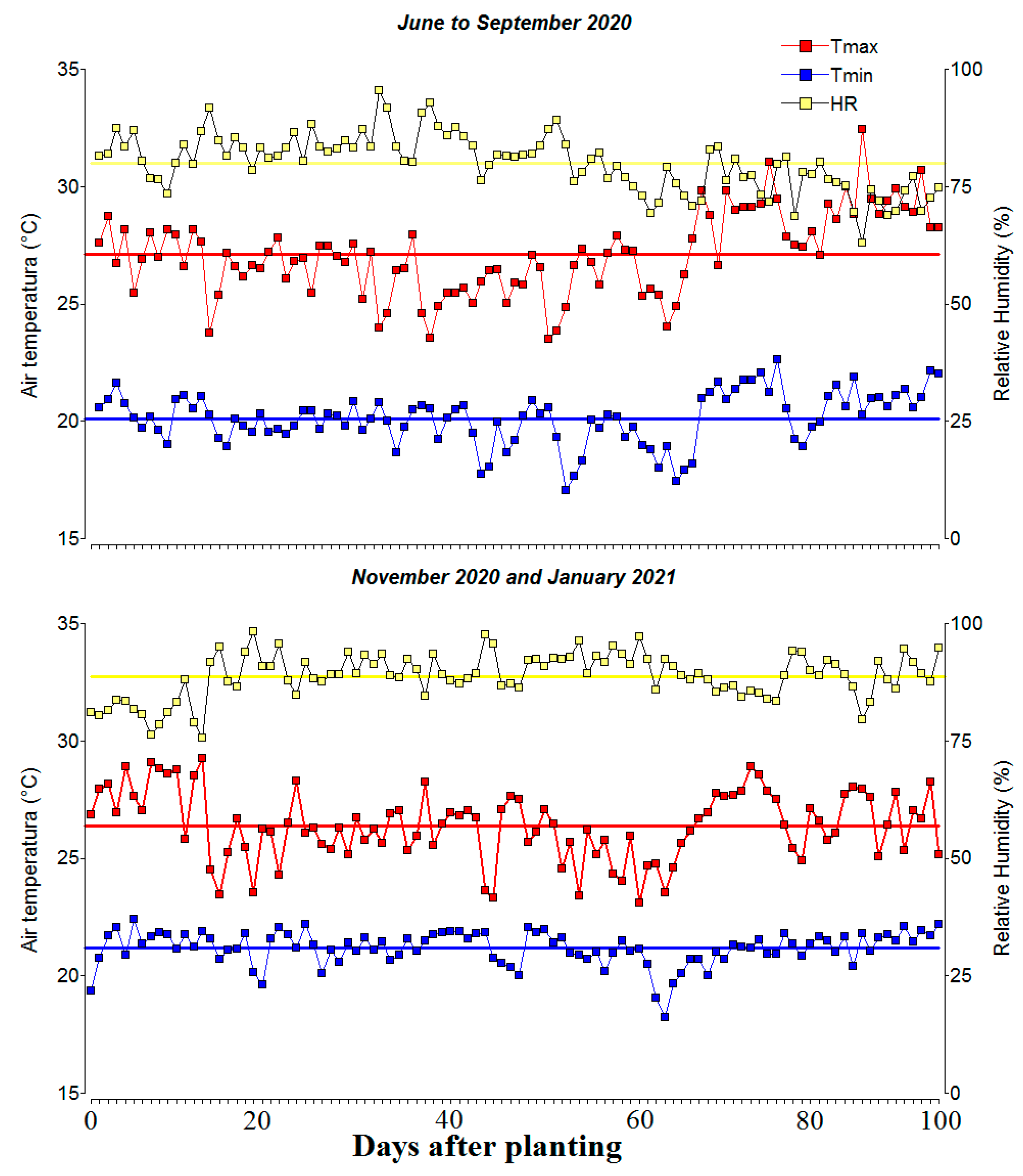

2.1 Experimental site and meteorological conditions

2.2. Plant material and experimental design

2.3. Canopy biomass, dry matter partitioning indices, grain yield and yield components

2.4. Phenological behavior and viability of pollen

2.5. Energy use efficiency and leaf cooling capacity under high temperature conditions

2.6 Determination of Fe and Zn in seeds

2.7. Data analysis

3. Results

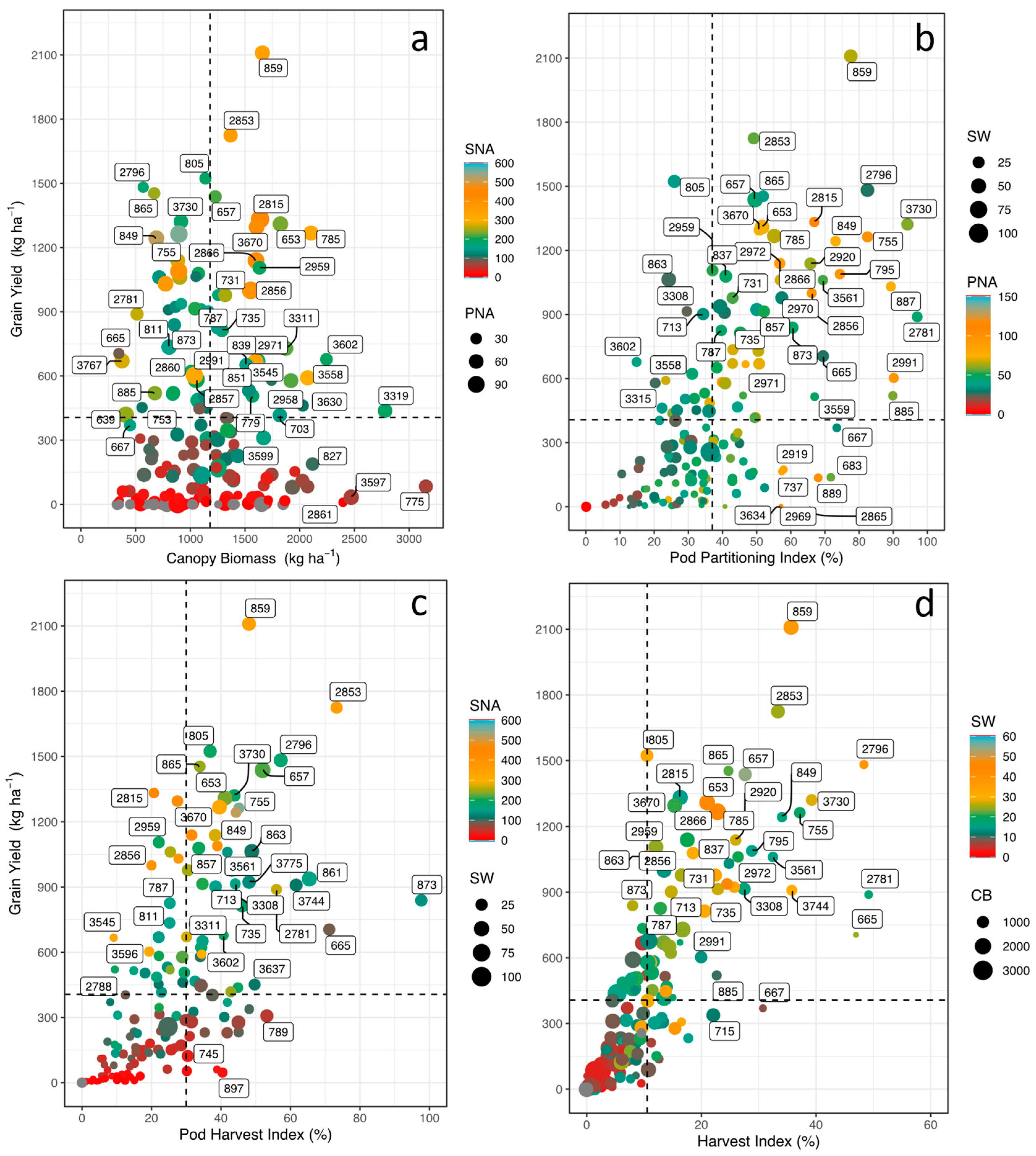

3.1. Phenotypic differences in agronomic performance

3.2. Phenotypic differences in phenology and pollen viability

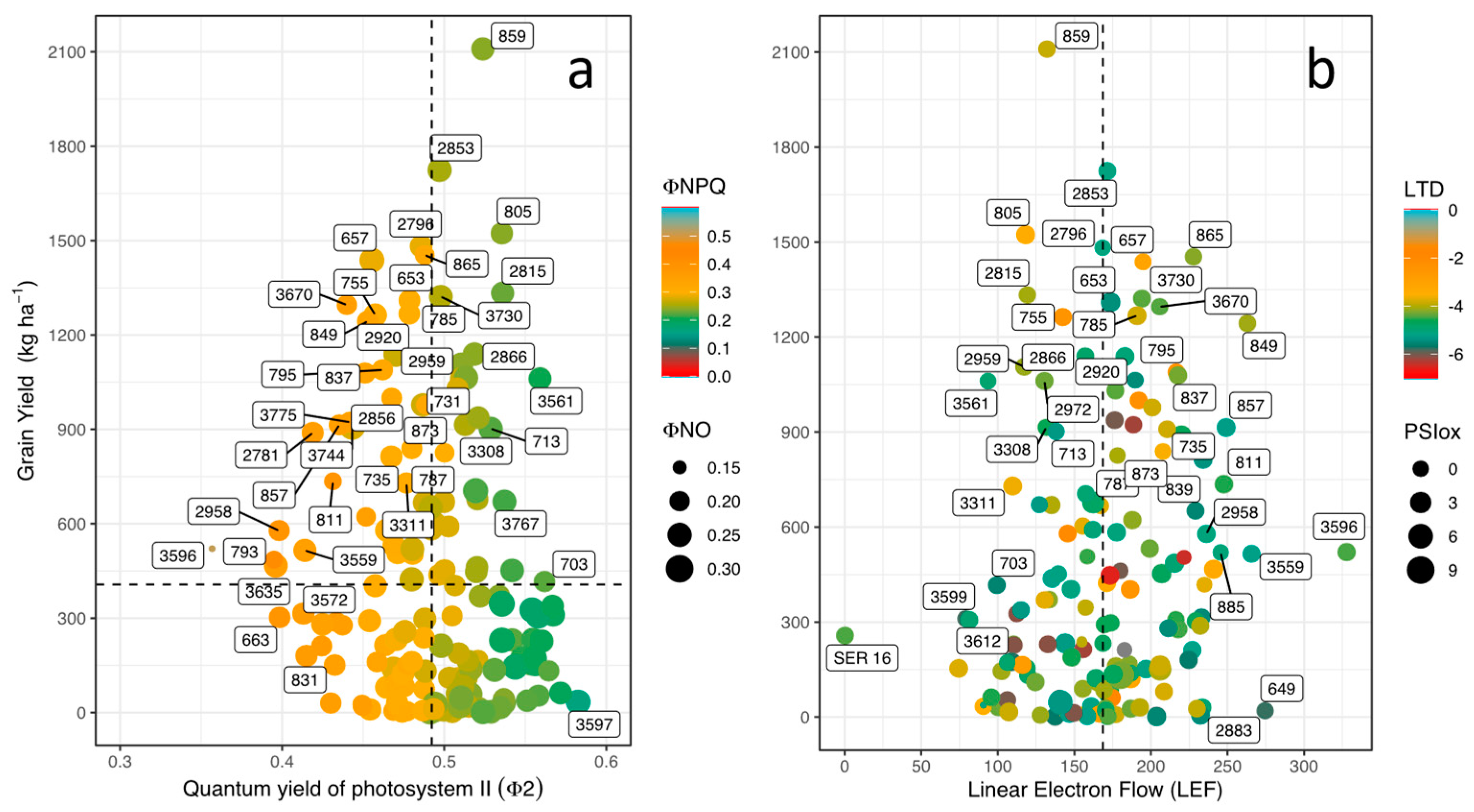

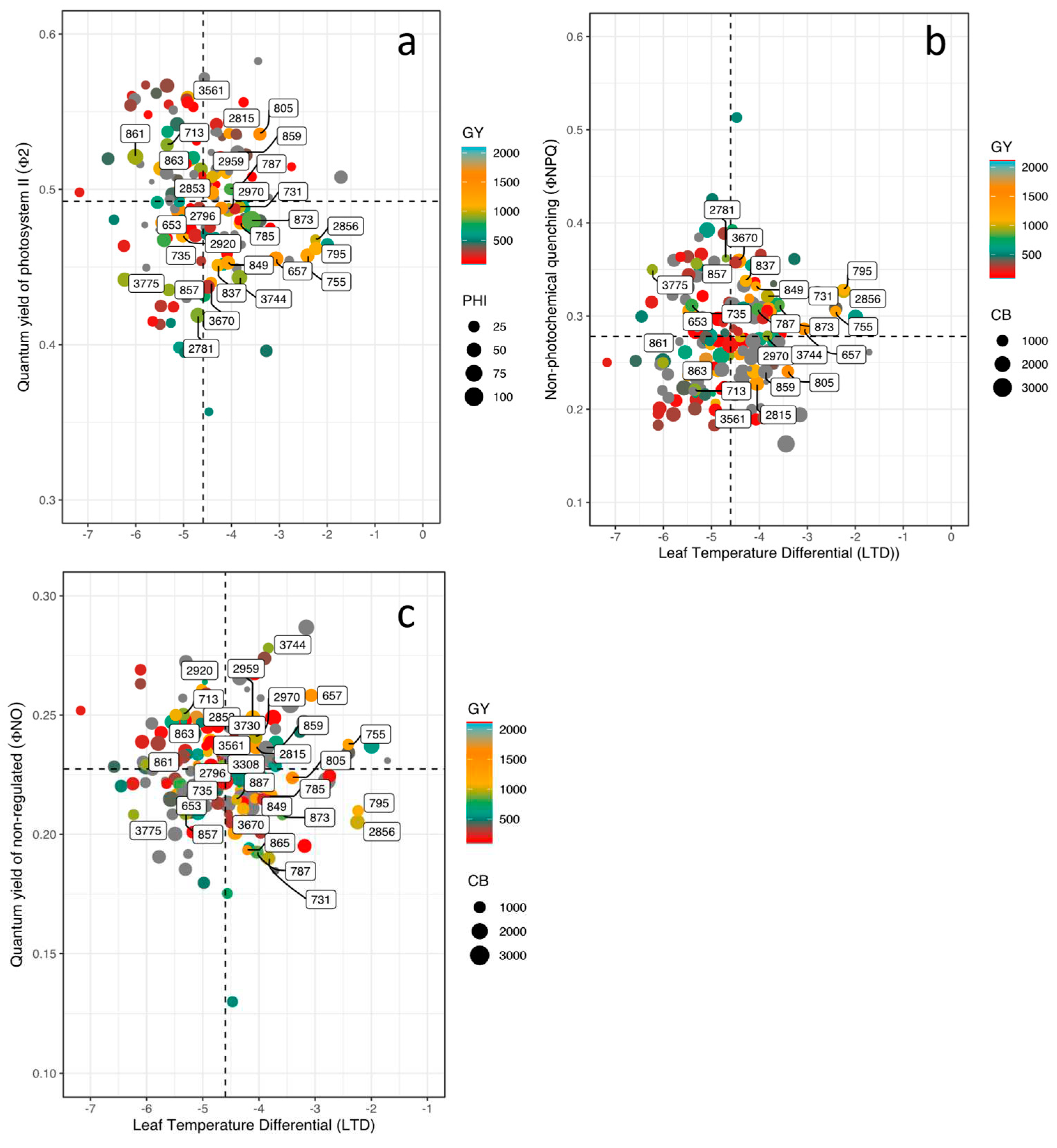

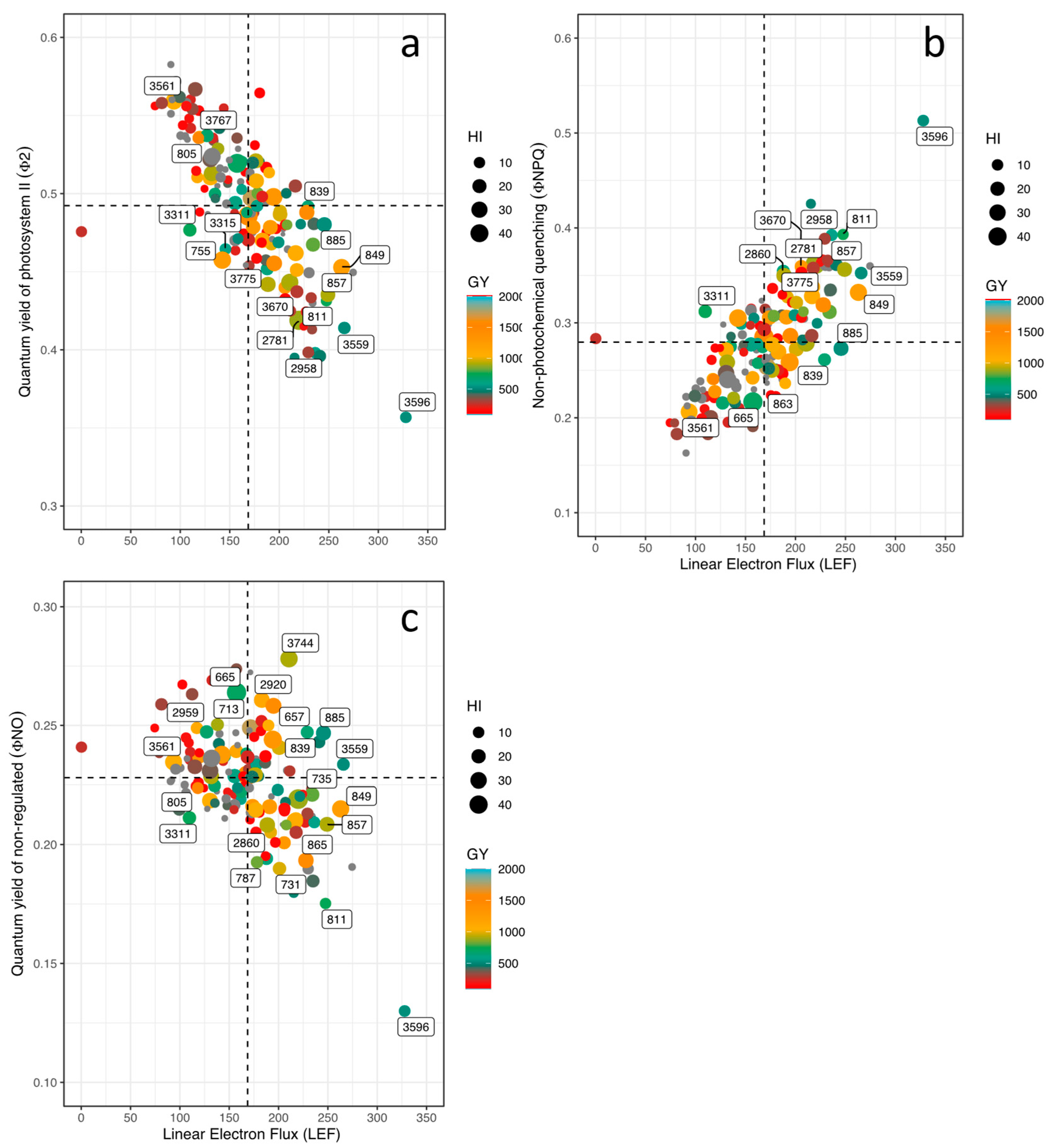

3.3. Phenotypic differences in energy use, leaf cooling and linear electron flow

3.4. Correlations between physiological and agronomic traits

4. Discussion

4.1 Differences in crop development and photosynthate remobilization affect agronomic performance

4.2. Combined stress affects phenology and pollen viability

4.3. Capacity of photosynthetic apparatus for coping with soil acidity and high temperature

4.4. Differences in physiological response between common bean lines reflect possible mechanisms in the translocation of assimilates that favor better yields

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; et al. Resumen para responsables de políticas. Calentamiento global de 1,5 °C Informe especial del IPCC sobre los impactos del calentamiento global de 1,5 °C con respecto a los niveles preindustriales y las trayectorias correspondientes que deberían seguir las e. 2019. Available online: www.ipcc.ch (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Rao, I.M.; Beebe, S.E.; Polania, J.; Grajales, M.; Cajiao, C.; Ricaurte, J.; et al. Evidence for genotypic differences among elite lines of common bean in the ability to remobilize photosynthate to increase yield under drought. J Agric Sci 2017, 155,857–75. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-agricultural-science/article/abs/evidence-for-genotypic-differences-among-elite-lines-of-common-bean-in-the-ability-to-remobilize-photosynthate-to-increase-yield-under-drought/83C9BB85244976B650B0846AD47E (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; P Zhai, H.-O.; Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock MT y TW (eds. Resumen para responsables de políticas. En: Calentamiento global de 1,5 °C, Informe especial del IPCC sobre los impactos del calentamiento global de 1,5 oC con respecto a los niveles preindustriales y las trayectorias correspondientes que deberían seguir. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC; 2018, pp. 26. Available online: https://bibliotecasemiaridos.ufv.br/jspui/handle/123456789/338 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Lobell, D.B.; Burke, M.B.; Tebaldi, C.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L. Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science 2008, 319, 607–10. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1152339 (accessed on 27 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourkheirandish, M.; Golicz, A.A.; Bhalla, P.L.; Singh, M.B. Global role of crop genomics in the face of climate change. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porch, T.G.; Beaver, J.S.; Brick, M.A. Registration of tepary germplasm with multiple-stress tolerance, TARS-Tep 22 and TARS-Tep 32. J Plant Regist. 2013, 7, 358–64. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3198/jpr2012.10.0047crg (accessed on 13 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Raggi, L.; Caproni, L.; Carboni, A.; Negri, V. Genome-wide association study reveals candidate genes for flowering time variation in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ). Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizana, C.; Wentworth, M.; Martinez, J.P.; Villegas, D.; Meneses, R.; Murchie, E.H.; et al. Differential adaptation of two varieties of common bean to abiotic stress:, I. Effects of drought on yield and photosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 2006, 57, 685–97. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erj062 (accessed on 27 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, I.M. Digging deep into defining physiological responses to environmental stresses in the tropics: The case of common bean and Brachiaria forage grasses. In: M. Pessarakli, editor. Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology. CRC Press,. 2021. p. 1099–140.

- Buitrago-Bitar, M.A.; Cortés, A.J.; López-Hernández, F.; Londoño-Caicedo, J.M.; Muñoz-Florez, J.E.; Carmenza Muñoz, L. , et al. Allelic diversity at abiotic stress responsive genes in relationship to ecological drought indices for cultivated tepary bean, phaseolus acutifolius a. Gray, and its wild relatives. Genes 2021, 12, 556. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/12/4/556/htm (accessed on 13 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ligarreto, G. Componentes de variancia en variables de crecimiento y fotosíntesis en fríjol común (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ). Rev UDCA Actual Divulg Científica. 2013, 16, 87–96. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-42262013000100011&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Assefa, T.; Rao, I.M.; Cannon, S.B.; Wu, J.; Gutema, Z.; Blair, M. , et al. Improving adaptation to drought stress in white pea bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): Genotypic effects on grain yield, yield components and pod harvest index. Plant Breed. 2017, 136, 548–61. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/pbr.12496 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Schmutz, J.; McClean, P.E.; Mamidi, S.; Wu, G.A.; Cannon, S.B.; Grimwood, J. , et al. A reference genome for common bean and genome-wide analysis of dual domestications. Nat Genet 2014 467. 2014, 46, 707–13. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.3008 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Beebe, S.; Rao, I.M.; Blair, M.; Acosta, J. Phenotyping common beans for adaptation to drought. Front Physiol. 2013, 0, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, S. Common bean breeding in the tropics. Plant Breed Rev. 2012, 36, 357–426. [Google Scholar]

- Polania, J.A.; Poschenrieder, C.; Beebe, S.; Rao, I.M. Effective use of water and increased dry matter partitioned to grain contribute to yield of common bean improved for drought resistance. Front Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, I.M. Advances in Improving Adaptation of Common Bean and Brachiaria Forage Grasses to Abiotic Stresses in the Tropics. In: Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology, Third Edition. CRC Press; 2014. p. 847–89. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/35000 (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Jarvis, A.; Ramirez, J.; Bonilla-Findji, O.; Zapata, E. Impacts of climate change on crop production in Latin America. Crop Adapt to Clim Chang. 2011, 44–56. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/9780470960929.ch4 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Zapata-Caldas, E.; Hyman, G.; Pachón, H.; Monserrate, F.A.; Varela, L.V. Identifying candidate sites for crop biofortification in Latin America: Case studies in Colombia, Nicaragua and Bolivia. Int J Health Geogr. 2009, 8, 1–18. Available online: https://ij-healthgeographics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1476-072X-8-29 (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICBF (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar). Encuesta nacional de la situación nutricional en Colombia (ENSIN). Bogotá, ICBF. 2023.

- Diaz, S.; Polania, J.; Ariza-Suarez, D.; Cajiao, C.; Grajales, M.; Raatz, B. Genetic correlation between Fe and Zn biofortification and yield components in a common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ). Front Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 739033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Lynch, J.; Tohme, J.M.; Beebe, S.E.; Macchiavelli, R.E. Characters related to leaf photosynthesis in wild populations and landraces of common bean. Crop Sci. 1995, 35, 1468–76. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.2135/cropsci1995.0011183X003500050034x (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Amongi, W.; Nkalubo, S.T.; Ochwo-Ssemakula, M.; Badji, A.; Dramadri, I.O.; Odongo, T.L. , et al. Phenotype based clustering, and diversity of common bean genotypes in seed iron concentration and cooking time. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0284976. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0284976 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Huertas, R.; Karpinska, B.; Ngala, S.; Mkandawire, B.; Maling’a, J.; Wajenkeche, E. , et al. Biofortification of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) with iron and zinc: Achievements and challenges. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e406. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/fes3.406 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Lamptey, M.; Adu-Dapaah, H.; Osei Amoako-Andoh, F.; Butare, L.; Bediako, K.A.; Amoah, R.A. , et al. Genetic studies on iron and zinc concentrations in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Ghana. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e17303. Available online: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ (accessed on 28 September 2023). [PubMed]

- Beebe, S. Biofortification of common bean for higher iron concentration. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2020, 4, 573449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, S.; Kapoor, P.; Kumar, A.; Chunduri, V. , et al. Biofortified crops generated by breeding, agronomy, and transgenic approaches are improving lives of millions of people around the world. Vol. 5, Frontiers in Nutrition. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2018. p. 301899.

- Diaz, S.; Ariza-Suarez, D.; Izquierdo, P.; Lobaton, J.D.; de la Hoz, J.F.; Acevedo, F. , et al. Genetic mapping for agronomic traits in a MAGIC population of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under drought conditions. BMC Genomics. 2020, 21, 1–20. Available online: https://bmcgenomics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12864-020-07213-6 (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Kimani, P.M.; Warsame, A.H.M.E.D. Breeding second-generation biofortified bean varieties for Africa. Food Energy Secur. 2019, 8, e00173. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/fes3.173 (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- CIAT Breeding micronutrient dense bean varieties in eastern Africa. Bean Improvement for the Tropics, Annual Report I-P1 Report, Cali, Colombia, pp. 15–25. 2008.

- Blair, M.W.; Izquierdo, P. Use of the advanced backcross-QTL method to transfer seed mineral accumulation nutrition traits from wild to Andean cultivated common beans. Theor Appl Genet. 2012, 125, 1015–31. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00122-012-1891-x (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, M.W.; Astudillo, C.; Rengifo, J.; Beebe, S.E.; Graham, R. QTL analyses for seed iron and zinc concentrations in an intra-genepool population of Andean common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ). Theor Appl Genet. 2011, 122, 511–21. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00122-010-1465-8 (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, M.W.; González, L.F.; Kimani, P.M.; Butare, L. Genetic diversity, inter-gene pool introgression and nutritional quality of common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ) from Central Africa. Theor Appl Genet. 2010, 121, 237–48. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00122-010-1305-x (accessed on 4 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.W.; Astudillo, C.; Grusak, M.A.; Graham, R.; Beebe, S.E. Inheritance of seed iron and zinc concentrations in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ). Mol Breed. 2009, 23, 197–207. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11032-008-9225-z (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cichy, K.A.; Caldas, G.V.; Snapp, S.S.; Blair, M.W. QTL analysis of seed iron, zinc, and phosphorus levels in an andean bean population. Crop Sci. 2009, 49, 1742–50. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.2135/cropsci2008.10.0605 (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Del Peloso, M.; Bassinello, P.; Guimarães, C.; Melo, L.; Faria, L. Genetic variability for iron and zinc content in common bean lines and interaction with water availability. Genet Mol Res. 2014, 13, 6773–85. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2014.August.28.21 (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cichy, K.; Chiu, C.; Isaacs, K.; Glahn, R. Dry Bean Biofortification with Iron and Zinc. Biofortification Staple Crop. 2022, 225–70. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-3280-8_10 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Saradadevi, R.; Mukankusi, C.; Li, L.; Amongi, W.; Mbiu, J.P.; Raatz, B. , et al. Multivariate genomic analysis and optimal contributions selection predicts high genetic gains in cooking time, iron, zinc, and grain yield in common beans in East Africa. Plant Genome. 2021, 14, e20156. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/tpg2.20156 (accessed on 28 September 2023). [PubMed]

- Philipo, M.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Mbega, E.R. Environmental and genotypes influence on seed iron and zinc levels of landraces and improved varieties of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ) in Tanzania. Ecol Genet Genomics. 2020, 15, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, J.C.; Polanía, J.A.; Contreras, A.T.; Rodríguez, L.; Beebe, S.; Rao, I.M. Agronomical, phenological and physiological performance of common bean lines in the Amazon region of Colombia. Theor Exp Plant Physiol. 2018, 30, 303–20. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40626-018-0125-2 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Suárez, J.C.; Rao, I.M. Photosynthetic response of common bean and tepary bean genotypes grown under the combined stress conditions of acid soil and high temperature. In: Pessarakli M, editor. Handbook of Photosynthesis. 4th Editio. 2024.

- Suárez, J.C.; Polanía, J.A.J.A.; Contreras, A.T.; Rodríguez, L.; Machado, L.; Ordoñez, C. , et al. Adaptation of common bean lines to high temperature conditions: genotypic differences in phenological and agronomic performance. Euphytica 2020, 216, 1–20. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-020-2565-4 (accessed on 23 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Suárez, J.C.; Urban, M.O.; Contreras, A.T.; Grajales, M.Á.; Cajiao, C.; Beebe, S.E. , et al. Adaptation of interspecific mesoamerican common bean lines to acid soils and high temperature in the amazon region of colombia. Plants 2021, 10, 2412. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/10/11/2412/htm (accessed on 4 June 2023). [PubMed]

- Porch, T.G.; Jahn, M. Effects of high-temperature stress on microsporogenesis in heat-sensitive and heat-tolerant genotypes of Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 723–31. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00716.x (accessed on 12 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Tsukaguchi, T.; Takeda, H.; Egawa, Y. Decrease of pollen stainability of green bean at high temperatures and relationship to heat tolerance. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2001, 126, 571–4. Available online: https://journals.ashs.org/jashs/view/journals/jashs/126/5/article-p571.xml (accessed on 13 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Kuhlgert, S.; Austic, G.; Zegarac, R.; Osei-Bonsu, I.; Hoh, D.; Chilvers, M.I.; et al. MultispeQ Beta: A tool for large-scale plant phenotyping connected to the open photosynQ network. R Soc Open Sci. 2016, 3. Available online: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/abs/10.1098/rsos.160592 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Kanazawa, A.; Ostendorf, E.; Kohzuma, K.; Hoh, D.; Strand, D.D.; Sato-Cruz, M. , et al. Chloroplast ATP synthase modulation of the thylakoid proton motive force: implications for photosystem I and photosystem II photoprotection. Front Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 264832. [Google Scholar]

- Sacksteder, C.A.; Kramer, D.M. Dark-interval relaxation kinetics (DIRK) of absorbance changes as a quantitative probe of steady-state electron transfer. Photosynth Res. 2000, 66, 145–58. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1010785912271 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Chovancek, E.; Zivcak, M.; Brestic, M.; Hussain, S.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. The different patterns of post-heat stress responses in wheat genotypes: the role of the transthylakoid proton gradient in efficient recovery of leaf photosynthetic capacity. Photosynth Res. 2021, 150(1–3):179–93. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11120-020-00812-0 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Kramer, D.M.; Johnson, G.; Kiirats, O.; Edwards, G.E. New fluorescence parameters for the determination of QA redox state and excitation energy fluxes. Photosynth Res. 2004, 79, 209–18. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:PRES.0000015391.99477.0d (accessed on 28 September 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tietz, S.; Hall, C.C.; Cruz, J.A.; Kramer, D.M. NPQ(T): a chlorophyll fluorescence parameter for rapid estimation and imaging of non-photochemical quenching of excitons in photosystem-II-associated antenna complexes. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 1243–55. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/pce.12924 (accessed on 28 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, J.C.; Contreras, A.T. BD Exp. C17d y F5.9_Sco. PROJECT ID: 11013, 4169. [Dataset). Universidad de la Amazonia. 2023. Available online: https://www.photosynq.org/projects/bd-exp-c17d-y-f5-9_sco.

- Di Rienzo, J.A.; Macchiavelli, R.; Casanoves, F. Mixed models in Infostat. Electronic version. 2012. 1994 p.

- Bankaji, I.; Kouki, R.; Dridi, N.; Ferreira, R.; Hidouri, S.; Duarte, B. , et al. Comparison of Digestion Methods Using Atomic Absorption Spectrometry for the Determination of Metal Levels in Plants. 2023, 10, 40. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2297-8739/10/1/40/htm (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Second Edition. Springer. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. R version 4.2.0 (2022-04-22) -- “Vigorous Calisthenics” Copyright (C) 2024 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing Platform: x86_64-apple-darwin17.0 (64-bit). 2023; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/.

- Nguyen, N.; Drakou, E.G. Farmers intention to adopt sustainable agriculture hinges on climate awareness: The case of Vietnamese coffee. J Clean Prod. 2021, 303, 126828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, D.F.C.; Urban, M.O.; Santaella, M.; Gereda, J.M.; Contreras, A.D.; Wenzl, P. Using phenomics to identify and integrate traits of interest for better-performing common beans: A validation study on an interspecific hybrid and its Acutifolii parents. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1008666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, J.C.; Urban, M.O.; Contreras, A.T.; Noriega, J.E.; Deva, C.; Beebe, S.E. , et al. Water use, leaf cooling and carbon assimilation efficiency of heat resistant common beans evaluated in Western Amazonia. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 644010–644010. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/med/34912351 (accessed on 7 April 2022). [PubMed]

- Araus, J.L.; Slafer, G.A.; Reynolds, M.P.; Royo, C. Plant breeding and drought in C3 cereals: what should we breed for? Ann Bot. 2002, 85, 925–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polania, J.; Poschenrieder, C.; Rao, I.M.; Beebe, S. Estimation of phenotypic variability in symbiotic nitrogen fixation ability of common bean under drought stress using 15N natural abundance in grain. Eur J Agron. 2016, 79, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Gogoi, N.; Barthakur, S.; Baroowa, B.; Bharadwaj, N.; Alghamdi, S.S. , et al. Drought stress in grain legumes during reproduction and grain filling. J Agron Crop Sci. 2017, 203, 81–102. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jac.12169 (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Kazai, P.; Noulas, C.; Khah, E.; Vlachostergios, D. Yield and seed quality parameters of common bean cultivars grown under water and heat stress field conditions. AIMS Agric Food. 2019, 4, 285–302. Available online: http://www.aimspress.com/journal/agriculture (accessed on 29 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Rao, I.M.; Beebe, S.E.; Polanía, J.; Grajales, M.; Cajiao, C.; García, R. , et al. Physiological basis of improved drought resistance in common bean: the contribution of photosynthate mobilization to grain. In: Paper presented at Interdrought III: the 3rd International Conference on Integrated Approaches to Improve Crop Production Under Dro. 2009.

- Beebe, S.E.; Rao, I.M.; Cajiao, C.; Grajales, M. Selection for drought resistance in common bean also improves yield in phosphorus limited and favorable environments. Crop Sci. 2008, 48, 582–92. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.2135/cropsci2007.07.0404 (accessed on 11 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Assefa, T.; Beebe, S.E.; Rao, I.M.; Cuasquer, J.B.; Duque, M.C.; Rivera, M. , et al. Pod harvest index as a selection criterion to improve drought resistance in white pea bean. F Crop Res. 2013, 148, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, S.E.; Rao, I.M.; Blair, M.; Butare, L. Breeding for abiotic stress tolerance in common bean: present and future challenges. In: Proceedings of the 14th Australian Plant Breeding & 11th SABRAO Conference, 10–14 August, Brisbane, Australia. In.

- Klaedtke, S.M.; Cajiao, C.; Grajales, M.; Polanía, J.; Borrero, G.; Guerrero, A. , et al. Photosynthate remobilization capacity from drought-adapted common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) lines can improve yield potential of interspecific populations within the secondary gene pool. J Plant Breed Crop Sci. 2012, 4, 49–61. Available online: http://www.academicjournals.org/JPBCS (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Rao, I.M.; Beebe, S.; Polania, J.; Ricaurte, J.; Cajiao, C.; Garcia, R. , et al. Can tepary bean be a model for improvement of drought resistance in common bean? African Crop Sci J. 2013, 21, 265–81. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/acsj/article/view/95291 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Hall, A.E. Comparative ecophysiology of cowpea, common bean, and peanut. Physiol Biotechnol Integr Plant Breed. 2004, 243–87. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9780203022030-11/comparative-ecophysiology-cowpea-common-bean-peanut-anthony-hall (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Rosales-Serna, R.; Kohashi-Shibata, J.; Acosta-Gallegos, J.A.; Trejo-López, C.; Ortiz-Cereceres, J.; Kelly, J.D. Biomass distribution, maturity acceleration and yield in drought-stressed common bean cultivars. F Crop Res. 2004, 85, 203–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polania, J.; Rao, I.M.; Cajiao, C.; Rivera, M.; Raatz, B.; Beebe, S. Physiological traits associated with drought resistance in Andean and Mesoamerican genotypes of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ). Euphytica. 2016, 210, 17–29. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10681-016-1691-5 (accessed on 29 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Omae, H.; Kumar, A.; Shono, M. Adaptation to high temperature and water deficit in the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) during the reproductive period. J Bot. 2012, 2012.

- Yamori, W.; Hikosaka, K.; Way, D.A. Temperature response of photosynthesis in C3, C4, and CAM plants: Temperature acclimation and temperature adaptation. Photosynth Res. 2014, 119, 101–17. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11120-013-9874-6 (accessed on 29 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattari, H.V.; Tavalaei, S.; Grillon, A.; Meyer, L.; Ballabani, G.; Glauser, G. , et al. Growth temperature influence on lipids and photosynthesis in Lepidium sativum. Front Plant Sci. 2020 Jun 4;11:515048.

- Shanker, A.K.; Bhanu, D.; Sarkar, B.; Yadav, S.K.; Jyothilakshmi, N.; Maheswari, M. Infra red thermography reveals transpirational cooling in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) plants under heat stress. bioRxiv. 2020. 2020.09.04.283283. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.04.283283v2 (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Shanker, A.K.; Amirineni, S.; Bhanu, D.; Yadav, S.K.; Jyothilakshmi, N.; Vanaja, M. , et al. High-resolution dissection of photosystem II electron transport reveals differential response to water deficit and heat stress in isolation and combination in pearl millet [Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 892676. [Google Scholar]

- Klughammer, C.; Schreiber, U. Complementary PS II quantum yields calculated from simple fluorescence parameters measured by PAM fluorometry and the saturation pulse method. PAM Appl Notes. 2008, 1, 27–35. Available online: http://www.walz.com/http://www.walz.com/ (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Fernández-Calleja, M.; Monteagudo, A.; Casas, A.M.; Boutin, C.; Pin, P.A.; Morales, F. , et al. Rapid on-site phenotyping via field fluorimeter detects differences in photosynthetic performance in a hybrid—parent barley germplasm set. Sensors (Switzerland). 2020, 20, 1486. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/20/5/1486/htm (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Tikkanen, M.; Mekala, N.R.; Aro, E.M. Photosystem II photoinhibition-repair cycle protects Photosystem I from irreversible damage. Biochim Biophys Acta - Bioenerg. 2014, 1837, 210–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Yang, S.J.; Zhang, S.B.; Zhang, J.L.; Cao, K.F. Cyclic electron flow plays an important role in photoprotection for the resurrection plant Paraboea rufescens under drought stress. Planta. 2012, 235, 819–28. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00425-011-1544-3 (accessed on 29 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rott, M.; Martins, N.F.; Thiele, W.; Lein, W.; Bock, R.; Kramer, D.M. , et al. ATP synthase repression in tobacco restricts photosynthetic electron transport, CO2 assimilation, and plant growth by overacidification of the thylakoid lumen. Plant Cell. 2011, 23, 304–321. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.110.079111 (accessed on 29 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Ramegowda, V.; Kumar, A.; Pereira, A. Plant adaptation to drought stress. F1000Research. 2016, 5. Available online: http://pmc/articles/PMC4937719/ (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Ben-Jabeur, M.; Gracia-Romero, A.; López-Cristoffanini, C.; Vicente, R.; Kthiri, Z.; Kefauver, S.C. , et al. The promising MultispeQ device for tracing the effect of seed coating with biostimulants on growth promotion, photosynthetic state and water–nutrient stress tolerance in durum wheat. Euro-Mediterranean J Environ Integr. 2021, 6, 1–11. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41207-020-00213-8 (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Baker, N.R. Chlorophyll fluorescence: A probe of photosynthesis in vivo.Vol. 59, Annual Review of Plant Biology. Annual Reviews; 2008, 89–113. Available online: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092759 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Rao, I.M. Role of physiology in improving crop adaptation to abiotic stresses in the tropics: the case of common bean and tropical forages. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; pp. 605–636. [Google Scholar]

- Çiçek, N.; Pekcan, V.; Arslan, Ö.; Çulha Erdal, Ş.; Balkan Nalçaiyi, A.S.; Çil, A.N. , et al. Assessing drought tolerance in field-grown sunflower hybrids by chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics. Rev Bras Bot. 2019, 42, 249–60. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40415-019-00534-1 (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Che, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Effect of hypoxia on photosystem II of tropical seagrass enhalus acoroides in the dark. Photochem Photobiol. 2022, 98, 421–8. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/php.13522 (accessed on 29 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorio, P.; Sellami, M.H. Polyphasic okjip chlorophyll a fluorescence transient in a landrace and a commercial cultivar of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L. ) under long-term salt stress. Plants. 2021, 10, 887. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/10/5/887/htm (accessed on 29 September 2023). [PubMed]

- Janeeshma, E.; Kalaji, H.M.; Puthur, J.T. Differential responses in the photosynthetic efficiency of Oryza sativa and Zea mays on exposure to Cd and Zn toxicity. Acta Physiol Plant. 2021, 43, 1–16. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11738-020-03178-x (accessed on 29 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Nsiri, K.; Krouma, A. The Key Physiological and Biochemical Traits Underlying Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ) Response to Iron Deficiency, and Related Interrelationships. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 2148. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/13/8/2148/htm (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Mari, S.; Bailly, C.; Thomine, S. Handing off iron to the next generation: How does it get into seeds and what for? . Biochemical Journal. Portland Press; 2020, 477, 259–74. Available online: https://biochemj/article/477/1/259/221883/Handing-off-iron-to-the-next-generation-how-does (accessed on 3 December 2023). [CrossRef]

| Variables | GY | HI | PHI | DF | DPM | LTD | ΦII | LEF | Seed Fe | Seed Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain yield (GY) | 0.8*** | 0.68*** | 0.11* | -0.17* | ||||||

| Canopy biomass (CB) | 0.36*** | -0.23*** | 0.13* | |||||||

| Pod partitioning index (PPI) | 0.6*** | 0.73*** | 0.42*** | -0.15* | 0.15* | 0.18* | ||||

| Pod harvest index (PHI) | 0.68*** | 0.75*** | -0.25*** | -0.16 | 0.2** | -0.17* | ||||

| Harvest index (HI) | 0.8*** | 0.75*** | -0.18* | -0.16 | 0.19** | -0.14* | ||||

| Days to flowering (DF) | -0.25*** | -0.19** | 0.21* | |||||||

| Days to physiological maturity (DPM) | 0.2** | -0.13 | ||||||||

| Ambient humidity (AH) | 0.68*** | 0.21*** | -0.31*** | |||||||

| Ambient temperature (AT) | 0.15* | 0.19** | -0.27*** | -0.55*** | -0.23*** | 0.46*** | -0.39* | |||

| Amplitude of electrochromic band shift signal (ECSt mAU) | -0.16** | -0.21** | ||||||||

| Activity of ATP synthase (gH+) | -0.28*** | 0.24*** | -0.38* | -0.29* | ||||||

| Leaf angle (LA) | 0.27*** | 0.19* | 0.11* | -0.15* | ||||||

| Leaf temperature differential (LTD) | 0.2** | -0.11* | ||||||||

| Linear electron flow (LEF) | 0.11* | 0.19** | 0.2** | -0.19** | -0.78*** | -0.18* | ||||

| Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) | 0.19** | 0.19** | -0.15* | -0.9*** | 0.96*** | -0.14* | ||||

| Energy dissipated as heat total (NPQt) | -0.13* | -0.76*** | 0.67*** | |||||||

| Fractions of energy received by photosystem II (ΦII) | -0.16* | -0.16* | -0.11* | -0.78*** | ||||||

| Fractions of energy not dissipated (ΦNO) | 0.01* | 0.16* | 0.35*** | -0.41*** | ||||||

| Fractions of energy dissipated as heat (ΦNPQ) | -0.93*** | 0.78*** | ||||||||

| Total active PSI centers (PSIact) | 0.13* | 0.17* | 0.13* | 0.14* | ||||||

| Over-reduced PSI (PSIor) | 0.14* | |||||||||

| Fraction of oxidized PSI center (PSIox) | -0.03* | |||||||||

| Relative chlorophyll content (RChl) | 0.2** | 0.22*** | -0.22*** | -0.16** | 0.25*** | -0.21* | ||||

| Leaf thickness (T) | -0.1 | -0.15* | 0.17** | 0.16* | ||||||

| Proton flux (vH+) | 0.15* | 0.16 | -0.18* | -0.87*** | 0.92*** | 0.17* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).