Introduction

Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) is a highly nutritious and drought-tolerant pseudocereal known for its rich protein, mineral, and vitamin content (Malik et al., 2023). It has garnered attention as a sustainable food source, especially in regions facing food insecurity and climatic challenges. The leaves of amaranth, along with its seeds, are valued for their nutritional density, making them an excellent dietary supplement (Singh et al., 2024). Recent studies have highlighted the essential nutrients present in amaranth leaves, such as protein, calcium, iron, zinc, and potassium, which are vital for overall health and well-being, particularly in regions with high malnutrition rates (Jan et al., 2023; Kumar et al., 2024; Skwaryło-Bednarz et al., 2020).

Research on amaranth's nutritional profile has primarily focused on its seeds, emphasizing the high levels of essential amino acids, lipids, and minerals they contain (Baraniak & Kania-Dobrowolska, 2022; Procopet & Oroian, 2022). However, there is a need for more comprehensive studies on the nutritional potential of amaranth leaves, which significantly contribute to the plant's overall nutritional value. Variations in nutrient levels across different genotypes and environments have not been extensively studied. Some accessions have shown higher concentrations of protein and minerals under stress conditions, suggesting the potential for breeding stress-resistant, nutrient-dense varieties(HRICOVÁ et al., 2016; Kachiguma et al., 2015).

Genotype and environmental factors play crucial roles in determining the bioavailable nutrient content of amaranth (Sarker et al., 2020; Jahan et al., 2023). Soil type, water availability, and climate can impact the nutritional profile of amaranth leaves, leading to variations in essential minerals and vitamins. Soil amendments, temperature, and water stress have been identified as factors that can influence the nutrient density of amaranth under different growing conditions(Ejieji and Adeniran, 2009; Cechin et al., 2022).

Despite the nutritional promise of amaranth, challenges persist in optimizing the production of nutrient-dense varieties. Understanding the interactions between genotype and environment is essential for enhancing nutrient accumulation. Identifying accessions with superior nutritional profiles across diverse environments is key to developing resilient and nutrient-rich varieties suited to different agro-ecological zones. This study aims to investigate the chemical composition of amaranth leaves across various accessions and locations, identify key nutritional traits, and assess the impact of environmental factors on nutrient accumulation. The results will offer valuable insights into the potential of amaranth as a biofortified crop and inform breeding strategies to enhance its nutritional content.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material Selection

In this study, we built upon our previous research by incorporating a new amaranth accession, CK-BH-01, which exhibited promising traits in initial assessments (Nyasulu et al., 2024). Alongside the five previously chosen accessions, we conducted a nutrition analysis on these six accessions: MN-BH-01, LL-BH-04, NU-BH-01, PE-UP-BH-01, PE-LO-BH-01, and CK-BH-01. These accessions represent a diverse range of genetic backgrounds and phenotypic characteristics, forming a robust basis for evaluating the nutritional potential of amaranth cultivars in different environments.

Study Sites and Experimental Design

The study was conducted in four strategically selected locations in Malawi: Thyolo Research, Mzimba-Champhira, Kasungu-Chulu, and Salima-Chipoka, representing distinct agro-ecological zones. Thyolo Research (16.0691S, 35.1420E) and Mzimba-Champhira (12.3320S, 33.5964E) fall within the high-altitude agro-ecological zone, characterized by annual rainfall exceeding 1000 mm and temperatures ranging from 15°C to 20°C. Kasungu-Chulu (12.8090S, 33.3110E) represents the middle-altitude zone, with moderate rainfall (500–1000 mm) and temperatures reaching up to 26°C. Salima-Chipoka (13.9920S, 34.5096E) is situated in the low-altitude zone, which experiences lower annual rainfall (<500 mm) and higher temperatures averaging above 27°C (Sithole et al., 2023).

These locations were selected to capture diverse agro-ecological zones and varying environmental conditions, providing an ideal framework for assessing genotype-by-environment interactions. Their distinct climatic characteristics allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of amaranth accessions under different environmental influences, particularly in relation to soil and plant nutrient dynamics.

Field experiments followed a randomized complete block design (RCBD), with each block consisting of 20 plants per accession spaced 30 cm apart within rows and 60 cm between rows to promote optimal growth and minimize competition. The trials were conducted during the 2022/2023 rainfed cropping season across three agro-ecological zones in Malawi.

Soil Preparation and Fertilization

Soil samples were collected from each study site before and after fertilizer application to assess variations in soil chemical properties. Samples were analyzed for pH, electrical conductivity (EC), organic matter (OM), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) using standard soil analysis protocols. Changes in soil properties following fertilizer application were recorded, particularly increases in pH, EC, N, P, and K, with a slight decrease in OM (

Table 1).

Sample Preparation

The leaf samples were collected in the six week when the plants were fully established. They prepared in two forms, as fresh leaves and dried leaves and get processed for chemical analyses. A total of 72 samples were thus put in plastic bags and labelled carefully then brought to the laboratory. For the fresh samples, the leaves were cleaned by tap water, chopped into smaller pieces and then oven dried at 60oC. These were then reduced into powder form for easy proximate and mineral analysis While for dry sample analysis the leaves were sun dried for two days until they crisped. Moisture content was then determined by oven drying at 105oC for three hours and reduced into powder by milling them in a blender in readiness for chemical analysis.

Proximate Analysis

Determination of moisture, ash, fibre and crude protein were done following the recommended methods of Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Moisture was determined using oven drying method of 5g samples of respective working sample, fresh sample (60oC) and dry sample (105oC ±1).

Ash content was determined using incineration method of 5g samples at 550oC for 5 hours. Crude protein content was determined using Kjeldahl method and total protein was calculated by multiplying the evaluated nitrogen by 6.25 (Moore et al., 2010).

Mineral Content

Mineral elements such as potassium, calcium, iron and zinc were analysed using dry ashing and atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS) according to AOAC recommended methods (Jimoh et al., 2020).

Statistical Analysis

Data was subjected to General Linear model (GLM) to determine the effects of accessions and sites in the nutrient composition. Proximate and mineral element means were compared and separated using Tukey test at 0.05 level of significance. Data was analysed in Genstat 21st edition and R 4.4.2 statistical packages. Cluster, correlation, and AMMI were conducted in R 4.4.2

Results

The Chemical Composition of Amaranth Leaves

The chemical composition of amaranth leaves varied significantly among accessions on a dry matter basis (

Table 2, P < 0.001). Moisture content ranged from 85.07% (MN-BH-01) to 85.89% (LL-BH-04), with MN-BH-01 having significantly lower moisture content. Ash content was highest in NU-BH-01 (15.64%) and lowest in PE-LO-BH-01 (12.93%), indicating variability in mineral content. Crude protein content ranged from 38.91% (NU-BH-01) to 43.18% (MN-BH-01), with MN-BH-01 having the highest protein concentration. Iron content varied, with PE-UP-BH-01 having the highest concentration (77.16 mg/100 g) and PE-LO-BH-01 the lowest (50.04 mg/100 g). Zinc content ranged from 13.12 mg/100 g to 15.12 mg/100 g, with MN-BH-01 having the highest value. Calcium content varied between 6.74 mg/100 g and 8.00 mg/100 g, with MN-BH-01 showing the highest concentration. Potassium content was highest in PE-UP-BH-01 and MN-BH-01, while NU-BH-01 had the lowest value. MN-BH-01 consistently exhibited superior nutritional quality, particularly in crude protein, calcium, zinc, and potassium content, while PE-UP-BH-01 had the highest iron and potassium levels. These results suggest that amaranth accessions show significant variation in nutrient composition, which can be utilized for breeding and nutritional enhancement programs.

Cluster Analysis of Nutrient Profiles and Correlation Analysis of the Variables

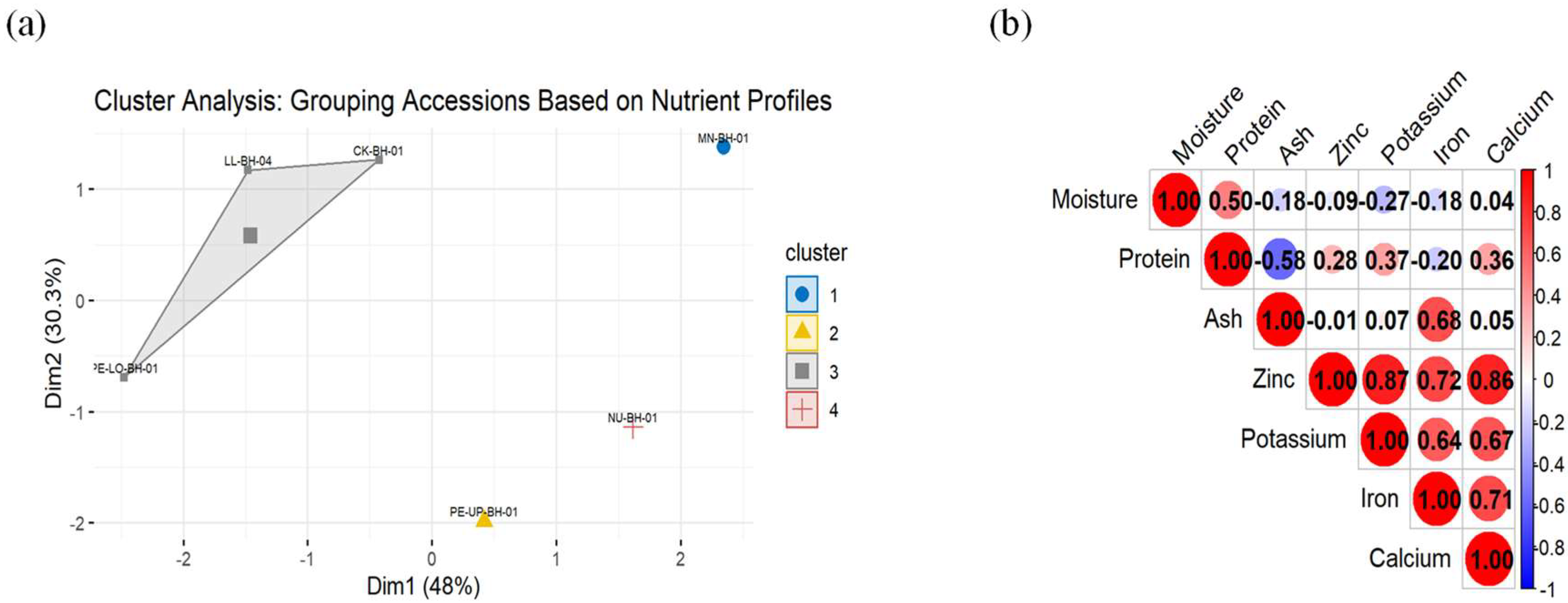

Cluster analysis of the rice accessions based on their nutrient profiles revealed four distinct groups (

Figure 1a). Cluster 1, represented by MN-BH-01, and is characterized by elevated levels of protein, iron, and potassium. Cluster 2, consisting of PE-UP-BH-01, is defined by high iron content and moderate potassium levels. Cluster 3, comprising CK-BH-01, LL-BH-04, and PE-LO-BH-01, showcases accessions with balanced nutrient profiles, featuring moderate levels of protein, zinc, and potassium. Lastly, Cluster 4, represented by NU-BH-01, stands out due to its exceptionally high iron content. These clusters underscore the unique nutrient compositions of each accession, providing valuable insights for crop breeding and biofortification strategies.

Correlation analysis revealed significant associations between different nutrient components in the amaranth accessions (

Figure 1b). Strong positive correlations were observed between iron, potassium, calcium, and zinc (r > 0.7, p < 0.05), indicating that these minerals tend to co-accumulate in the accessions. Protein showed a moderate positive correlation with ash (r = 0.28) but a negative correlation with moisture content (r = -0.50), suggesting that higher protein levels are associated with lower moisture retention. The observed correlations provide critical information for selecting nutrient-dense accessions and optimizing breeding strategies to enhance multiple nutritional traits simultaneously.

Chemical Composition of Amaranth Leaves Across Different Locations and Accessions

The chemical composition of amaranth leaves varied significantly across locations and accessions (

P < 0.001), indicating the influence of environmental factors on nutrient accumulation (

Table 3). Moisture content ranged from 80.50% (MN-BH-01 at Mzimba-Champhira) to 90.38% (CK-BH-01 at Kasungu-Chulu), with accessions grown in Kasungu-Chulu generally exhibiting higher moisture levels. Ash content was highest in PE-UP-BH-01 (18.89%) at Salima-Chipoka and lowest in PE-LO-BH-01 (11.39%) at Mzimba-Champhira, reflecting variability in mineral composition. Crude protein content varied significantly, with LL-BH-04 in Kasungu-Chulu displaying the highest value (56.50%), while CK-BH-01 at Thyolo Research recorded the lowest (31.42%).

Iron content was substantially elevated in PE-UP-BH-01 (135.85 mg/100 g) at Salima-Chipoka, followed by NU-BH-01 (105.31 mg/100 g) at the same site, whereas the lowest iron concentration (30.66 mg/100 g) was observed in PE-LO-BH-01 at Kasungu-Chulu. Zinc content ranged from 8.20 mg/100 g (LL-BH-04 at Kasungu-Chulu) to 18.95 mg/100 g (PE-LO-BH-01 at Thyolo Research), indicating differences in micronutrient uptake. Calcium levels varied widely, with CK-BH-01 at Thyolo Research showing the highest content (10.55 mg/100 g) and LL-BH-04 at Kasungu-Chulu the lowest (4.03 mg/100 g). Potassium content was highest in PE-LO-BH-01 (23.37 mg/g) at Thyolo Research and lowest in LL-BH-04 (12.02 mg/g) at Kasungu-Chulu.

Overall, PE-UP-BH-01 at Salima-Chipoka exhibited superior iron content, while LL-BH-04 at Kasungu-Chulu was remarkable for its high crude protein concentration. The observed differences across locations highlight significant genotype-by-environment interactions affecting the nutritional composition of amaranth, which can be exploited for site-specific varietal recommendations and breeding programs.

Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction (AMMI) Analysis

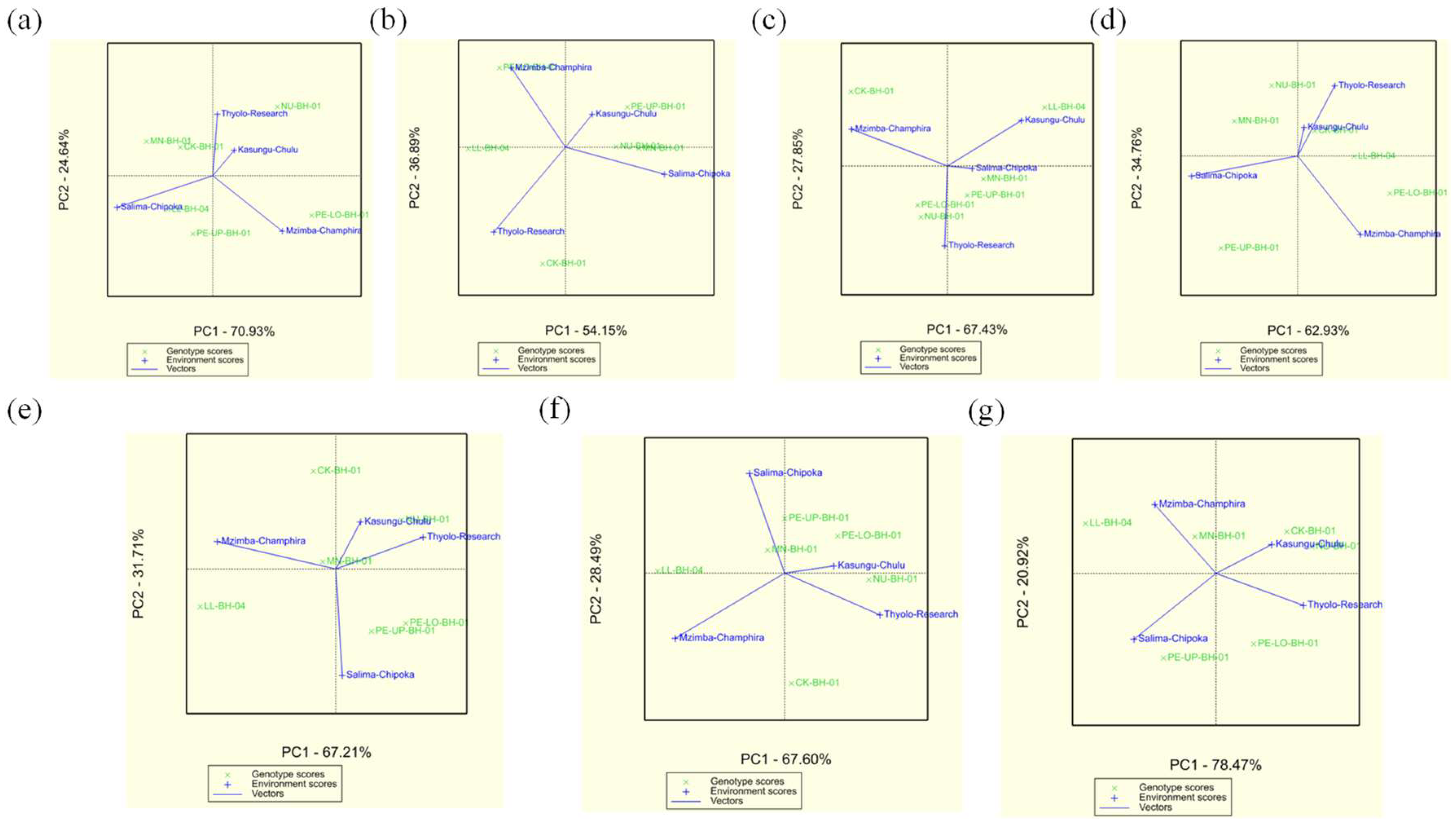

The AMMI analysis identified significant genotype-by-environment (G×E) interactions affecting the nutritional composition of amaranth accessions at the four study locations (

Figure 2). Moisture content (PC1: 70.93%) was most stable in CK-BH-01, MN-BH-01, and NU-BH-01, especially in Kasungu-Chulu, while PE-LO-BH-01 and PE-UP-BH-01 showed pronounced environmental interactions (

Figure 2a). Ash content (PC1: 54.15%) remained consistent in CK-BH-01 and NU-BH-01, with notable variability in Mzimba-Champhira and PE-UP-BH-01 (

Figure 2b). Crude protein (PC1: 67.43%) exhibited stability in NU-BH-01, CK-BH-01, and MN-BH-01, with significant environmental influences in Mzimba-Champhira and Thyolo Research (

Figure 2c). Iron content (PC1: 62.93%) was stable in LL-BH-04 and NU-BH-01, particularly in Kasungu-Chulu, while Salima-Chipoka and Mzimba-Champhira showed location-dependent variations (

Figure 2d). Zinc content (PC1: 67.21%) remained stable in CK-BH-01, MN-BH-01, and NU-BH-01, with strong interactions in Salima-Chipoka and Thyolo Research (

Figure 2e). Calcium content (PC1: 67.60%) was stable in NU-BH-01, CK-BH-01, and MN-BH-01, while PE-LO-BH-01 and LL-BH-04 displayed significant location-specific variations (

Figure 2f). Potassium content (PC1: 78.47%) showed remarkable stability in CK-BH-01, MN-BH-01, and NU-BH-01, with location-dependent effects in Mzimba-Champhira and Salima-Chipoka (

Figure 2g). Overall, CK-BH-01, MN-BH-01, and NU-BH-01 emerged as the most stable accessions across multiple nutritional traits, making them promising candidates for breeding programs targeting nutritional resilience. In contrast, PE-LO-BH-01, PE-UP-BH-01, and LL-BH-04 exhibited strong environmental interactions, indicating that their nutrient accumulation is highly dependent on location. These findings offer valuable insights for optimizing amaranth cultivation and breeding strategies to enhance nutritional traits in diverse agro-ecological zones.

Farmer Preferences and Ranking of Amaranth Accessions

Farmers actively participated in selecting their preferred amaranth accessions based on a range of agronomic and culinary characteristics (

Table 4). NU-BH-01 emerged as the top choice among the accessions assessed, thanks to its excellent flavor, high yield, market appeal, and the convenience of cooking without oil. Following closely, CK-BH-01 ranked second, favored for its delicious taste and post-cooking flavor. PE-LO-BH-01 claimed the third spot, valued for its abundant yield, extended harvest window, large leaves, and strong market demand, making it a highly sought-after variety. In fourth place, PE-UP-BH-01 stood out for its numerous branches, large leaf size, and pleasant taste. On the other hand, LL-BH-04 and MN-BH-01 were the least preferred, ranking fifth and sixth, respectively, due to their unappealing flavor profiles. LL-BH-04 received criticism for its poor taste, while MN-BH-01 was noted for its bitterness, rendering it the least favored accession. These findings underscore the significance of both agronomic performance and sensory attributes in shaping farmer preferences for amaranth cultivation and market success.

Discussion

Our study reveals significant variations in amaranth accessions across the four distinct agro-ecological zones of Thyolo Research, Mzimba-Champhira, Kasungu-Chulu, and Salima-Chipoka. These accessions demonstrated differential responses to environmental conditions, consistent with previous studies that underscore the pivotal role of local climate in shaping crop performance (Frei et al., 2024). The high-altitude agro-ecological zones, such as Thyolo Research, characterized by over 1000mm of annual rainfall and temperatures ranging from 15°C to 20°C, provided an optimal environment that resulted in enhanced nutritional performance of the amaranth accessions. Modi (2007) highlighted that favorable conditions, including moderate temperatures and adequate precipitation, significantly promote both amaranth growth and its nutritional value. Conversely, the low-altitude region of Salima-Chipoka, with less than 500mm of annual rainfall and temperatures exceeding 27°C, introduced harsher conditions, which led to the expression of stress tolerance traits in certain accessions. These traits contributed to the maintenance of nutritional stability, aligning with the findings of Reyes-Rosales et al.(2023), who observed heat-resistant genotypes in amaranth. Intriguingly, some accessions demonstrated consistent nutritional quality across different locations, which underscores the importance of selecting genotypes with broad adaptability for sustainable and nutritionally robust amaranth production (Kandel et al., 2021; Nyasulu et al., 2024; Oduwaye et al., 2016; Stoilova et al., 2015).

The variations in amaranth performance were further influenced by differences in soil chemical composition across the trial sites. In Thyolo research, the slight increase in soil pH from 5.7 to 6.0, coupled with the rise in nitrogen (N) levels from 0.08% to 0.11%, likely contributed to enhanced biomass accumulation, corroborating the findings of Toungos et al.(2018), which emphasize the role of nitrogen in amaranth growth. Additionally, significant increases in phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) availability were observed across the sites, particularly in Kasungu-Chulu, where P levels increased from 22.5 to 42.5 ppm and K levels from 56.5 to 169.1 ppm. This supports the work of Ojo et al. (2011), who reported that improved soil P enhances root development in amaranth. Conversely, a decline in organic matter (OM) levels, particularly in Salima-Chipoka (from 0.6% to 0.2%), may be attributed to mineralization following fertilizer application, in line with previous soil fertility studies. The resilience of stable accessions to these soil changes further highlights their adaptability to diverse agro-ecological conditions.

Our study affirms that soil composition and microclimatic conditions are critical determinants of amaranth’s nutritional content. While prior research has predominantly focused on the nutritional composition of amaranth grain, our study uniquely contributes to the limited body of literature that investigates the nutritional profiles of amaranth leaves in diverse agro-ecological zones (Coelho et al., 2018). Although studies on the nutritional composition of amaranth leaves across varied agro-ecological regions remain sparse, Förster et al.(2023) emphasized the substantial nutritional diversity in the leaves of different amaranth species, underscoring the importance of evaluating these leaves to address malnutrition. As amaranth is primarily consumed as a leafy vegetable in many regions, analyzing its leaf nutritional content is crucial for understanding its dietary value and optimizing cultivation strategies to improve nutritional outcomes (Sarker, Hossain, et al., 2020).

The observed nutritional variations across sites are consistent with Kachiguma's et al. (2015) findings, which suggest that temperature significantly influences amaranth's nutritional composition. Amaranth leaves are particularly rich in micronutrients and antioxidants, offering a unique nutritional profile when compared to other commonly consumed crops, such as wheat, barley, maize (Joshi et al., 2018), and rice (Nascimento et al., 2014). This makes amaranth a highly valuable dietary component, especially in regions where nutrient deficiencies are prevalent. Thus, amaranth’s potential as a crop to enhance dietary diversity and food security is further emphasized.

Furthermore, our findings extend the understanding of amaranth’s environmental adaptability, supporting earlier research that suggests the crop can thrive in a wide range of environmental conditions (Bashyal et al., 2022; Mukuwapasi et al., 2024; Yeshitila et al., 2023). The crop’s ability to maintain high nutritional quality across different agro-ecological zones highlights its potential as a climate-resilient crop. This characteristic is of particular significance in the context of increasing climate variability, as it ensures both food and nutritional security in resource-limited areas.

The identification of stable accessions is crucial for breeding programs, emphasizing the need to select genotypes that maintain consistent nutritional quality across diverse environmental conditions. Among the evaluated accessions, CK-BH-01, MN-BH-01, and NU-BH-01 showed the highest stability across multiple nutritional traits, making them strong candidates for breeding programs focused on enhancing nutritional resilience. Cluster analysis based on their nutrient profiles revealed four distinct groups, refining selection criteria for breeding. MN-BH-01, representing Cluster 1, has elevated levels of protein, iron, and potassium, highlighting its potential for nutritional enhancement. However, despite its superior and stable nutritional content, MN-BH-01 was less favored by farmers due to undesirable sensory traits like bitterness, underscoring the importance of considering both nutritional and sensory traits in breeding programs to ensure broader adoption by farmers and consumers. CK-BH-01, in Cluster 3, showed a balanced nutrient profile with moderate levels of protein, zinc, and potassium, while NU-BH-01, in Cluster 4, stood out for its exceptionally high iron content. These variations in nutrient compositions may be attributed to genetic differences among these amaranth accessions. Correlation analysis further revealed strong positive correlations between iron, potassium, calcium, and zinc, suggesting that these minerals tend to co-accumulate, presenting an opportunity for breeding strategies to enhance multiple nutrients simultaneously. A moderate positive correlation between protein and ash content indicates that protein-rich accessions may also have higher mineral levels, supporting the selection of varieties with both high protein and mineral content. However, the negative correlation between protein and moisture content suggests that higher protein levels are associated with lower moisture retention, which could impact storage and shelf life. Overall, these findings provide crucial insights into the genetic and nutritional makeup of amaranth accessions, guiding breeding efforts to optimize both mineral and protein content while balancing trade-offs like moisture retention

Beyond breeding applications, the identification of nutritionally stable accessions opens avenues for biofortification initiatives and the development of functional foods. Given amaranth’s rich nutritional profile, future research should explore its potential in fortifying staple foods or developing nutritionally enhanced food products. Furthermore, molecular studies are needed to identify the genetic mechanisms underlying nutrient stability in amaranth, which could support the development of targeted breeding strategies aimed at improving both yield and nutritional content. By linking nutritional stability, farmer preferences, and environmental adaptability, our study underscores the significant potential of amaranth as a sustainable, climate-resilient, and nutrient-rich crop. Future research and policy interventions should prioritize promoting amaranth as a vital crop for addressing malnutrition, particularly in regions where food insecurity remains a pressing concern. The integration of amaranth into sustainable agricultural systems could play a pivotal role in combating malnutrition and enhancing global food security. Future breeding efforts should also focus on reducing bitterness in MN-BH-01 while preserving its high nutritional value, leveraging advanced molecular breeding techniques to enhance both agronomic and nutritional traits.

Conclusion

Our study highlights significant variations in amaranth accessions across different agro-ecological zones, influenced by environmental factors like soil composition and climate. The observed differences emphasize the importance of selecting adaptable accessions with consistent nutritional quality for breeding programs. Amaranth shows promise as a climate-resilient, nutrient-rich crop to address malnutrition and food insecurity, especially in resource-limited regions. Stable accessions like CK-BH-01, MN-BH-01, and NU-BH-01 offer opportunities for breeding and biofortification initiatives. Molecular studies are needed to understand the genetic mechanisms behind nutrient stability for more effective breeding strategies. Future research should focus on optimizing amaranth's nutritional value while considering sensory traits and environmental conditions. Integrating amaranth into sustainable agricultural systems can significantly improve global food security and nutrition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A. S., M.N., Data collection and cleaning: M. N. Data analysis: M. N and A.S Experimental layout: M. N. and A. S. Funding acquisitions: A. S and M.N. Original manuscript draft: M. N. and A.S. Writing review, editing and final approval: M. N., R. M. K., A.S., K.M., D.E.S., S.K., and C.M.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results of this study are available from the corresponding authors (Abel Sefasi) upon request.

Acknowledgments

The research was financially supported by the Sustainable Food Systems in Malawi (FoodMA) Programme at LUANAR.

References

- Baraniak, J.; Kania-Dobrowolska, M. The Dual Nature of Amaranth—Functional Food and Potential Medicine. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashyal, S.; Upadhyay, A.; Ayer, D.K.; Dhakal, P.G.C.B.; Shrestha, J. Multivariate analysis of grain amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) accessions to quantify phenotypic diversity. Heliyon 2022, 8(11), e11613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cechin, I.; da Silva, L.P.; Ferreira, E.T.; Barrochelo, S.C.; de Melo, F.P.deS.R.; Dokkedal, A.L.; Saldanha, L.L. Physiological responses of Amaranthus cruentus L. to drought stress under sufficient- and deficient-nitrogen conditions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, L.M.; Silva, P.M.; Martins, J.T.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Vicente, A.A. Emerging opportunities in exploring the nutritional/functional value of amaranth. In (Vol. 9, Issue 11). In Food and Function; 2018; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejieji, C.J.; Adeniran, K. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Stress on the Yield, Fresh and Dry Matter Production of Grain Amaranth ('Amaranthus cruentus’). Search.Informit.Org 2009, 37, 195–199. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.632981648226333.

- Förster, N.; Dilling, S.; Ulrichs, C.; Huyskens-Keil, S. Nutritional diversity in leaves of various amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) genotypes and its resilience to drought stress. Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality 2023, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, J.; Wiesenberg, G.L.B.; Hirte, J. The impact of climate and potassium nutrition on crop yields: Insights from a 30-year Swiss long-term fertilization experiment. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2024, 372, 109100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRICOVÁ, A.; FEJÉR, J.; LIBIAKOVÁ, G.; SZABOVÁ, M.; GAŽO, J.; GAJDOŠOVÁ, A. Characterization of phenotypic and nutritional properties ofvaluable Amaranthus cruentus L. mutants. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 2016, 40, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Sarker, U.; Hasan Saikat, M.M.; Hossain, M.M.; Azam, M.G.; Ali, D.; Ercisli, S.; Golokhvast, K.S. Evaluation of yield attributes and bioactive phytochemicals of twenty amaranth genotypes of Bengal floodplain. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, N.; Hussain, S.Z.; Naseer, B.; Bhat, T.A. Amaranth and quinoa as potential nutraceuticals: A review of anti-nutritional factors, health benefits and their applications in food, medicinal and cosmetic sectors. Food Chemistry: X 2023, 18, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, M.O.; Afolayan, A.J.; Lewu, F.B. Nutrients and antinutrient constituents of Amaranthus caudatus L. Cultivated on different soils. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2020, 27, 3570–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.C.; Sood, S.; Hosahatti, R.; Kant, L.; Pattanayak, A.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, D.; Stetter, M.G. From zero to hero: the past, present and future of grain amaranth breeding. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2018, 131, 1807–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachiguma, N.A.; Mwase, W.; Maliro, M.; Damaliphetsa, A. Chemical and Mineral Composition of Amaranth ( Amaranthus L.) Species Chemical and Mineral Composition of Amaranth ( Amaranthus L.) Species Collected From Central Malawi. Journal of Food Research 2015, 4(4), 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, M.; Rijal, T.R.; Kandel, B.P. Evaluation and identification of stable and high yielding genotypes for varietal development in amaranthus (Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.) under hilly region of Nepal. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2021, 5, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Guleria, S.; Kimta, N.; Dhalaria, R.; Nepovimova, E.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Alomar, S.Y.; Kuca, K. Amaranth and buckwheat grains: Nutritional profile, development of functional foods, their pre-clinical cum clinical aspects and enrichment in feed. Current Research in Food Science 2024, 9, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.; Sindhu, R.; Dhull, S.B.; Bou-Mitri, C.; Singh, Y.; Panwar, S.; Khatkar, B.S. Nutritional Composition, Functionality, and Processing Technologies for Amaranth. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2023, 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, A.T. Growth temperature and plant age influence on nutritional quality of Amaranthus leaves and seed germination capacity. Water SA 2007, 33, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.C.; DeVries, J.W.; Lipp, M.; Griffiths, J.C.; Abernethy, D.R. Total Protein Methods and Their Potential Utility to Reduce the Risk of Food Protein Adulteration. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2010, 9(4), 330–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukuwapasi, B.; Mavengahama, S.; Shegro, A. Grain amaranth : A versatile untapped climate - smart crop for enhancing food and nutritional security. Discover Agriculture 2024, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.C.; Mota, C.; Coelho, I.; Gueifão, S.; Santos, M.; Matos, A.S.; Gimenez, A.; Lobo, M.; Samman, N.; Castanheira, I. Characterisation of nutrient profile of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus), and purple corn (Zea mays L.) consumed in the North of Argentina: proximates, minerals and trace elements. Food Chemistry 2014, 148, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyasulu, M.; Chimzinga, S.Z.; Maliro, M.; Kamanga, R.M.; Gal-, R.; Sefasi, A. Stability analysis and identification of high-yielding Amaranth accessions for varietal development under various agroecolo- gies of Malawi. Plant Genetic Resource 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Oduwaye, O.A.; Porbeni, J.B.O.; Adetiloye, I.S. Genetic variability and associations between grain yield and related traits in a maranthus cruentus and A maranthus hypochondriacus grown at two locations. Journal of Horticultural Research 2016, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O.D.; Akinrinde, E.A.; Akoroda, M.O. Phosphorus use efficiency in amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus L.). International Journal of AgriScience 2011, 1(2), 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Procopet, O.; Oroian, M. Amaranth Seed Polyphenol, Fatty Acid and Amino Acid Profile. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Rosales, A.; Cabrales-Orona, G.; Martínez-Gallardo, N.A.; Sánchez-Segura, L.; Padilla-Escamilla, J.P.; Palmeros-Suárez, P.A.; Délano-Frier, J.P. Identification of genetic and biochemical mechanisms associated with heat shock and heat stress adaptation in grain amaranths. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, U.; Hossain, M.M.; Oba, S. Nutritional and antioxidant components and antioxidant capacity in green morph Amaranthus leafy vegetable. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U.; Oba, S.; Daramy, M.A. Nutrients, minerals, antioxidant pigments and phytochemicals, and antioxidant capacity of the leaves of stem amaranth. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Samarth, R.M.; Vashishth, A.; Pareek, A. Amaranthus as a potential dietary supplement in sports nutrition. CYTA - Journal of Food 2024, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithole, D.A.; Maliro, M.; Masamba, K.C.; Nalivata, P. Nutrient Composition of Chia Genotypes Cultivated in Different Environments of Central Malawi. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2023, 11(11), 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwaryło-Bednarz, B.; Stępniak, P.M.; Jamiołkowska, A.; Kopacki, M.; Krzepiłko, A.; Klikocka, H. Amaranth seeds as a source of nutrients and bioactive substances in human diet. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum, Hortorum Cultus 2020, 19(6), 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, T.; Dinssa, F.F.; Ebert, A.W.; Tenkouano, A. The diversity of African leafy vegetables: Agromorphological characterization of subsets of AVRDC’s germplasm collection. Acta Horticulturae 2015, 1102, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toungos, M.; Babayola, M.; Shehu, H.; Kwaga, Y.; Bamai, N. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer on the Growth of Vegetable Amaranths (Amaranthus cruensis. L) in Mubi, Adamawa State Nigeria. Asian Journal of Advances in Agricultural Research 2018, 6(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshitila, M.; Gedebo, A.; Tesfaye, B.; Demissie, H.; Olango, T. M. Multivariate analysis for yield and yield-related traits of amaranth genotypes from Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).